User login

Hospitalist movers and shakers – September 2021

Chi-Cheng Huang, MD, SFHM, was recently was named one of the Notable Asian/Pacific American Physicians in U.S. History by the American Board of Internal Medicine. May was Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System (Winston-Salem, N.C.) and associate professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dr. Huang is a board-certified hospitalist and pediatrician, and he is the founder of the Bolivian Children Project, a non-profit organization that focuses on sheltering street children in La Paz and other areas of Bolivia. Dr. Huang was inspired to start the project during a year sabbatical from medical school. He worked at an orphanage and cared for children who were victims of physical abuse. The Bolivian Children Project supports those children, and Dr. Huang’s book, When Invisible Children Sing, tells their story.

Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, has been elected president of the Florida Medical Association. It is the first time in its history that the FMA will have a DO as its president. Dr. Lenchus is a hospitalist and chief medical officer at the Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Mark V. Williams, MD, MHM, will join Washington University School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare, both in St. Louis, as professor and chief for the Division of Hospital Medicine in October 2021. Dr. Williams is currently professor and director of the Center for Health Services Research at the University of Kentucky and chief quality officer at UK HealthCare, both in Lexington.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, one of the first two elected members of the Board of SHM, its former president, founding editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, and principal investigator for Project BOOST. He established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial in Atlanta) in 1998, and later became the founding chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2007 at Northwestern University School of Medicine in Chicago. At the University of Kentucky, he established the Center for Health Services Research and the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2014.

At Washington University, Dr. Williams will be tasked with translating the division of hospital medicine’s scholarly work, innovation, and research into practice improvement, focusing on developing new systems of health care delivery that are patient-centered, cost effective, and provide outstanding value.

Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM, has been named the new chief medical officer at Glytec (Waltham, Mass.), where he has worked as executive director of clinical practice since 2018. Dr. Messler will be tasked with leading strategy and product development while also supporting efforts in quality care, customer relations, and delivery of products.

Glytec provides insulin management software across the care continuum and is touted as the only cloud-based software provider of its kind. Dr. Messler’s background includes expertise in glycemic management. In addition, he still works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist Group (Clearwater, Fla.).

Dr. Messler is a senior fellow with SHM and is physician editor of SHM’s official blog The Hospital Leader.

Tiffani Maycock, DO, recently was named to the Board of Directors for the American Board of Family Medicine. Dr. Maycock is director of the Selma Family Medicine Residency Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is an assistant professor in the department of family medicine.

Dr. Maycock helped create hospitalist services at Vaughan Regional Medical Center (Selma, Ala.) – Selma Family Medicine’s primary teaching site – and currently serves as its hospitalist director and on its Medical Executive Committee. She has worked at the facility since 2017.

Preetham Talari, MD, SFHM, has been named associate chief of quality safety for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington, Ky.). Dr. Talari is an associate professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the UK College of Medicine.

Over the last decade, Dr. Talari’s work in quality, safety, and health care leadership has positioned him as a leader in several UK Healthcare committees and transformation projects. In his role as associate chief, Dr. Talari collaborates with hospital medicine directors, enterprise leadership, and medical education leadership to improve the system’s quality of care.

Dr. Talari is the president of the Kentucky chapter of SHM and is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee.

Adrian Paraschiv, MD, FHM, is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Internist and Hospitalist in the field of Medicine in acknowledgment of his commitment to providing quality health care services.

Dr. Paraschiv is a board-certified Internist at Garnet Health Medical Center in Middletown, N.Y. He also serves in an administrative capacity as the Garnet Health Doctors Hospitalist Division’s Associate Program Director. He is also the Director of Clinical Informatics. Dr. Paraschiv is certified as the Epic physician builder in analytics, information technology, and improved documentation.

DCH Health System (Tuscaloosa, Ala.) recently selected Capstone Health Services Foundation (Tuscaloosa) and IN Compass Health Inc. (Alpharetta, Ga.) as its joint hospitalist service provider for facilities in Northport and Tuscaloosa. Capstone will provide the physicians, while IN Compass will handle staffing management of the hospitalists, as well as day-to-day operations and calculating quality care metrics. The agreement is slated to begin on Oct. 1, 2021, at Northport Medical Center, and on Nov. 1, 2021, at DCH Regional Medical Center.

Capstone is an affiliate of the University of Alabama and oversees University Hospitalist Group, which currently provides hospitalists at DCH Regional Medical Center. Its partnership with IN Compass includes working together in recruiting and hiring physicians for both facilities.

UPMC Kane Medical Center (Kane, Pa.) recently announced the creation of a virtual telemedicine hospitalist program. UPMC Kane is partnering with the UPMC Center for Community Hospitalist Medicine to create this new mode of care.

Telehospitalists will care for UPMC Kane patients using advanced diagnostic technique and high-definition cameras. The physicians will bring expert service to Kane 24 hours per day utilizing physicians and specialists based in Pittsburgh. Those hospitalists will work with local nurse practitioners and support staff and deliver care to Kane patients.

Wake Forest Baptist Health (Winston-Salem, N.C.) has launched a Hospitalist at Home program with hopes of keeping patients safe while also reducing time they spend in the hospital. The telehealth initiative kicked into gear at the start of 2021 and considered the first of its kind in the region.

Patients who qualify for the program establish a plan before they leave the hospital. Wake Forest Baptist Health paramedics makes home visits and conducts care with a hospitalist reviewing the visit virtually. Those appointments continue until the patient does not require monitoring.

The impetus of creating the program was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Wake Forest said it expects to care for between 75-100 patients through Hospitalist at Home at any one time.

Chi-Cheng Huang, MD, SFHM, was recently was named one of the Notable Asian/Pacific American Physicians in U.S. History by the American Board of Internal Medicine. May was Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System (Winston-Salem, N.C.) and associate professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dr. Huang is a board-certified hospitalist and pediatrician, and he is the founder of the Bolivian Children Project, a non-profit organization that focuses on sheltering street children in La Paz and other areas of Bolivia. Dr. Huang was inspired to start the project during a year sabbatical from medical school. He worked at an orphanage and cared for children who were victims of physical abuse. The Bolivian Children Project supports those children, and Dr. Huang’s book, When Invisible Children Sing, tells their story.

Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, has been elected president of the Florida Medical Association. It is the first time in its history that the FMA will have a DO as its president. Dr. Lenchus is a hospitalist and chief medical officer at the Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Mark V. Williams, MD, MHM, will join Washington University School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare, both in St. Louis, as professor and chief for the Division of Hospital Medicine in October 2021. Dr. Williams is currently professor and director of the Center for Health Services Research at the University of Kentucky and chief quality officer at UK HealthCare, both in Lexington.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, one of the first two elected members of the Board of SHM, its former president, founding editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, and principal investigator for Project BOOST. He established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial in Atlanta) in 1998, and later became the founding chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2007 at Northwestern University School of Medicine in Chicago. At the University of Kentucky, he established the Center for Health Services Research and the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2014.

At Washington University, Dr. Williams will be tasked with translating the division of hospital medicine’s scholarly work, innovation, and research into practice improvement, focusing on developing new systems of health care delivery that are patient-centered, cost effective, and provide outstanding value.

Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM, has been named the new chief medical officer at Glytec (Waltham, Mass.), where he has worked as executive director of clinical practice since 2018. Dr. Messler will be tasked with leading strategy and product development while also supporting efforts in quality care, customer relations, and delivery of products.

Glytec provides insulin management software across the care continuum and is touted as the only cloud-based software provider of its kind. Dr. Messler’s background includes expertise in glycemic management. In addition, he still works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist Group (Clearwater, Fla.).

Dr. Messler is a senior fellow with SHM and is physician editor of SHM’s official blog The Hospital Leader.

Tiffani Maycock, DO, recently was named to the Board of Directors for the American Board of Family Medicine. Dr. Maycock is director of the Selma Family Medicine Residency Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is an assistant professor in the department of family medicine.

Dr. Maycock helped create hospitalist services at Vaughan Regional Medical Center (Selma, Ala.) – Selma Family Medicine’s primary teaching site – and currently serves as its hospitalist director and on its Medical Executive Committee. She has worked at the facility since 2017.

Preetham Talari, MD, SFHM, has been named associate chief of quality safety for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington, Ky.). Dr. Talari is an associate professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the UK College of Medicine.

Over the last decade, Dr. Talari’s work in quality, safety, and health care leadership has positioned him as a leader in several UK Healthcare committees and transformation projects. In his role as associate chief, Dr. Talari collaborates with hospital medicine directors, enterprise leadership, and medical education leadership to improve the system’s quality of care.

Dr. Talari is the president of the Kentucky chapter of SHM and is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee.

Adrian Paraschiv, MD, FHM, is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Internist and Hospitalist in the field of Medicine in acknowledgment of his commitment to providing quality health care services.

Dr. Paraschiv is a board-certified Internist at Garnet Health Medical Center in Middletown, N.Y. He also serves in an administrative capacity as the Garnet Health Doctors Hospitalist Division’s Associate Program Director. He is also the Director of Clinical Informatics. Dr. Paraschiv is certified as the Epic physician builder in analytics, information technology, and improved documentation.

DCH Health System (Tuscaloosa, Ala.) recently selected Capstone Health Services Foundation (Tuscaloosa) and IN Compass Health Inc. (Alpharetta, Ga.) as its joint hospitalist service provider for facilities in Northport and Tuscaloosa. Capstone will provide the physicians, while IN Compass will handle staffing management of the hospitalists, as well as day-to-day operations and calculating quality care metrics. The agreement is slated to begin on Oct. 1, 2021, at Northport Medical Center, and on Nov. 1, 2021, at DCH Regional Medical Center.

Capstone is an affiliate of the University of Alabama and oversees University Hospitalist Group, which currently provides hospitalists at DCH Regional Medical Center. Its partnership with IN Compass includes working together in recruiting and hiring physicians for both facilities.

UPMC Kane Medical Center (Kane, Pa.) recently announced the creation of a virtual telemedicine hospitalist program. UPMC Kane is partnering with the UPMC Center for Community Hospitalist Medicine to create this new mode of care.

Telehospitalists will care for UPMC Kane patients using advanced diagnostic technique and high-definition cameras. The physicians will bring expert service to Kane 24 hours per day utilizing physicians and specialists based in Pittsburgh. Those hospitalists will work with local nurse practitioners and support staff and deliver care to Kane patients.

Wake Forest Baptist Health (Winston-Salem, N.C.) has launched a Hospitalist at Home program with hopes of keeping patients safe while also reducing time they spend in the hospital. The telehealth initiative kicked into gear at the start of 2021 and considered the first of its kind in the region.

Patients who qualify for the program establish a plan before they leave the hospital. Wake Forest Baptist Health paramedics makes home visits and conducts care with a hospitalist reviewing the visit virtually. Those appointments continue until the patient does not require monitoring.

The impetus of creating the program was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Wake Forest said it expects to care for between 75-100 patients through Hospitalist at Home at any one time.

Chi-Cheng Huang, MD, SFHM, was recently was named one of the Notable Asian/Pacific American Physicians in U.S. History by the American Board of Internal Medicine. May was Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System (Winston-Salem, N.C.) and associate professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dr. Huang is a board-certified hospitalist and pediatrician, and he is the founder of the Bolivian Children Project, a non-profit organization that focuses on sheltering street children in La Paz and other areas of Bolivia. Dr. Huang was inspired to start the project during a year sabbatical from medical school. He worked at an orphanage and cared for children who were victims of physical abuse. The Bolivian Children Project supports those children, and Dr. Huang’s book, When Invisible Children Sing, tells their story.

Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, has been elected president of the Florida Medical Association. It is the first time in its history that the FMA will have a DO as its president. Dr. Lenchus is a hospitalist and chief medical officer at the Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Mark V. Williams, MD, MHM, will join Washington University School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare, both in St. Louis, as professor and chief for the Division of Hospital Medicine in October 2021. Dr. Williams is currently professor and director of the Center for Health Services Research at the University of Kentucky and chief quality officer at UK HealthCare, both in Lexington.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, one of the first two elected members of the Board of SHM, its former president, founding editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, and principal investigator for Project BOOST. He established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial in Atlanta) in 1998, and later became the founding chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2007 at Northwestern University School of Medicine in Chicago. At the University of Kentucky, he established the Center for Health Services Research and the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2014.

At Washington University, Dr. Williams will be tasked with translating the division of hospital medicine’s scholarly work, innovation, and research into practice improvement, focusing on developing new systems of health care delivery that are patient-centered, cost effective, and provide outstanding value.

Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM, has been named the new chief medical officer at Glytec (Waltham, Mass.), where he has worked as executive director of clinical practice since 2018. Dr. Messler will be tasked with leading strategy and product development while also supporting efforts in quality care, customer relations, and delivery of products.

Glytec provides insulin management software across the care continuum and is touted as the only cloud-based software provider of its kind. Dr. Messler’s background includes expertise in glycemic management. In addition, he still works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist Group (Clearwater, Fla.).

Dr. Messler is a senior fellow with SHM and is physician editor of SHM’s official blog The Hospital Leader.

Tiffani Maycock, DO, recently was named to the Board of Directors for the American Board of Family Medicine. Dr. Maycock is director of the Selma Family Medicine Residency Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is an assistant professor in the department of family medicine.

Dr. Maycock helped create hospitalist services at Vaughan Regional Medical Center (Selma, Ala.) – Selma Family Medicine’s primary teaching site – and currently serves as its hospitalist director and on its Medical Executive Committee. She has worked at the facility since 2017.

Preetham Talari, MD, SFHM, has been named associate chief of quality safety for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington, Ky.). Dr. Talari is an associate professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the UK College of Medicine.

Over the last decade, Dr. Talari’s work in quality, safety, and health care leadership has positioned him as a leader in several UK Healthcare committees and transformation projects. In his role as associate chief, Dr. Talari collaborates with hospital medicine directors, enterprise leadership, and medical education leadership to improve the system’s quality of care.

Dr. Talari is the president of the Kentucky chapter of SHM and is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee.

Adrian Paraschiv, MD, FHM, is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Internist and Hospitalist in the field of Medicine in acknowledgment of his commitment to providing quality health care services.

Dr. Paraschiv is a board-certified Internist at Garnet Health Medical Center in Middletown, N.Y. He also serves in an administrative capacity as the Garnet Health Doctors Hospitalist Division’s Associate Program Director. He is also the Director of Clinical Informatics. Dr. Paraschiv is certified as the Epic physician builder in analytics, information technology, and improved documentation.

DCH Health System (Tuscaloosa, Ala.) recently selected Capstone Health Services Foundation (Tuscaloosa) and IN Compass Health Inc. (Alpharetta, Ga.) as its joint hospitalist service provider for facilities in Northport and Tuscaloosa. Capstone will provide the physicians, while IN Compass will handle staffing management of the hospitalists, as well as day-to-day operations and calculating quality care metrics. The agreement is slated to begin on Oct. 1, 2021, at Northport Medical Center, and on Nov. 1, 2021, at DCH Regional Medical Center.

Capstone is an affiliate of the University of Alabama and oversees University Hospitalist Group, which currently provides hospitalists at DCH Regional Medical Center. Its partnership with IN Compass includes working together in recruiting and hiring physicians for both facilities.

UPMC Kane Medical Center (Kane, Pa.) recently announced the creation of a virtual telemedicine hospitalist program. UPMC Kane is partnering with the UPMC Center for Community Hospitalist Medicine to create this new mode of care.

Telehospitalists will care for UPMC Kane patients using advanced diagnostic technique and high-definition cameras. The physicians will bring expert service to Kane 24 hours per day utilizing physicians and specialists based in Pittsburgh. Those hospitalists will work with local nurse practitioners and support staff and deliver care to Kane patients.

Wake Forest Baptist Health (Winston-Salem, N.C.) has launched a Hospitalist at Home program with hopes of keeping patients safe while also reducing time they spend in the hospital. The telehealth initiative kicked into gear at the start of 2021 and considered the first of its kind in the region.

Patients who qualify for the program establish a plan before they leave the hospital. Wake Forest Baptist Health paramedics makes home visits and conducts care with a hospitalist reviewing the visit virtually. Those appointments continue until the patient does not require monitoring.

The impetus of creating the program was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Wake Forest said it expects to care for between 75-100 patients through Hospitalist at Home at any one time.

New fellowship, no problem

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Mean leadership

The differences between the mean and median of leadership data

Let me apologize for misleading all of you; this is not an article about malignant physician leaders; instead, it goes over the numbers and trends uncovered by the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM).1 The hospital medicine leader ends up doing many tasks like planning, growth, collaboration, finance, recruiting, scheduling, onboarding, coaching, and most near and dear to our hearts, putting out the fires and conflict resolution.

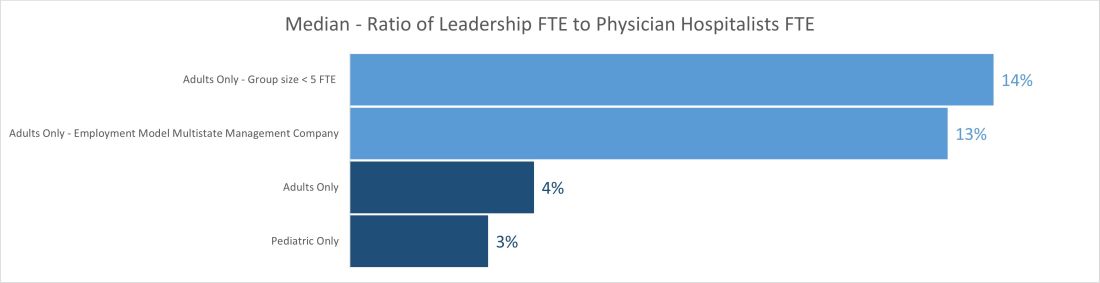

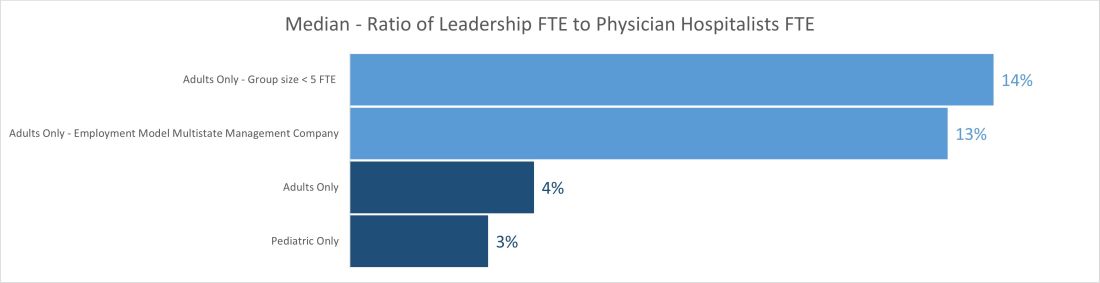

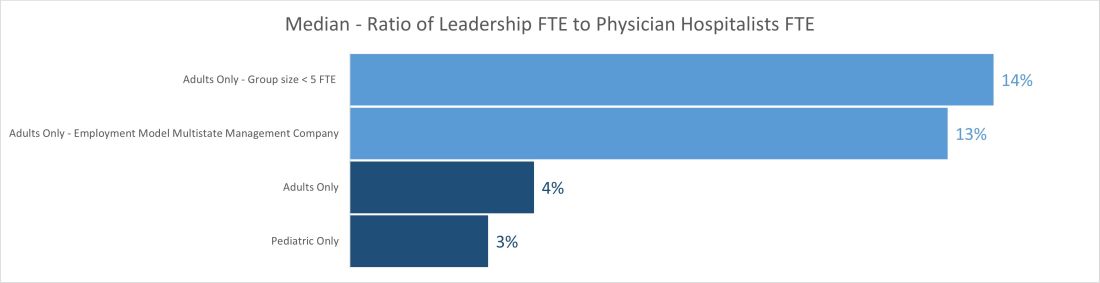

Ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE

If my pun has already put you off, you can avoid reading the rest of the piece and go to the 2020 SoHM to look at pages 52 (Table 3.7c), 121 (Table 4.7c), and 166 (Table 5.7c). It has a newly added table (3.7c), and it is phenomenal; it is the ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE. As an avid user of SoHM, I always ended up doing a makeshift calculation to “guesstimate” this number. Now that we have it calculated for us and the ultimate revelation lies in its narrow range across all groups. We might differ in the region, employment type, academics, teaching, or size, but this range is relatively narrow.

The median ratio of leadership FTE to total FTE lies between 2% and 5% in pediatric groups and between 3% and 6% for most adult groups. The only two outliers are on the adult side, with less than 5 FTE and multistate management companies. The higher median for the less than 5 FTE group size is understandable because of the small number of hospitalist FTEs that the leader’s time must be spread over. Even a small amount of dedicated leadership time will result in a high ratio of leader time to hospitalist clinical time if the group is very small. The multistate management company is probably a result of multiple layers of physician leadership (for example, regional medical directors) and travel-related time adjustments. Still, it raises the question of why the local leadership is not developed to decrease the leadership cost and better access.

Another helpful pattern is the decrease in standard deviation with the increase in group size. The hospital medicine leaders and CEOs of the hospital need to watch this number closely; any extremes on high or low side would be indicators for a deep dive in leadership structure and health.

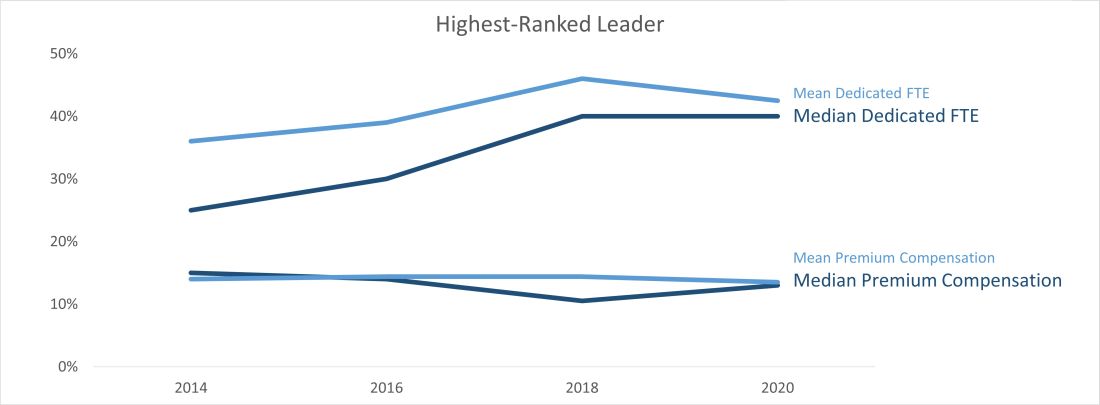

Total number and total dedicated FTE for all physician leaders

Once we start seeing the differences between the mean and median of leadership data, we can see the median is relatively static while the mean has increased year after year and took a big jump in the 2020 SoHM. The chart below shows trends for the number of individuals in leadership positions (“Total No” and total FTEs allocated to leadership (“Total FTE”) over the last several surveys. The data is heavily skewed toward the right (positive); so, it makes sense to use the median in this case rather than mean. A few factors could explain the right skew of data.

- Large groups of 30 or more hospitalists are increasing, and so is their leadership need.

- There is more recognition of the need for dedicated leadership individuals and FTE.

- The leadership is getting less concentrated among just one or a few leaders.

- Outliers on the high side.

- Lower bounds of 0 or 0.1 FTE.

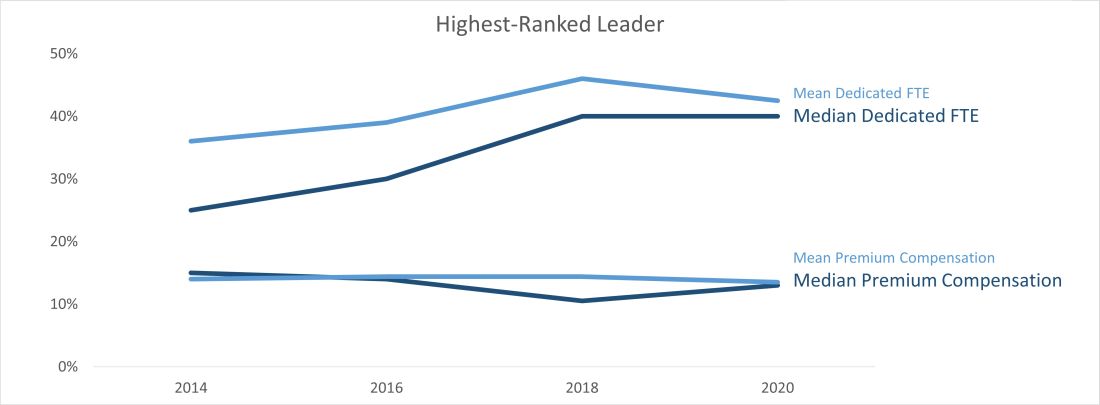

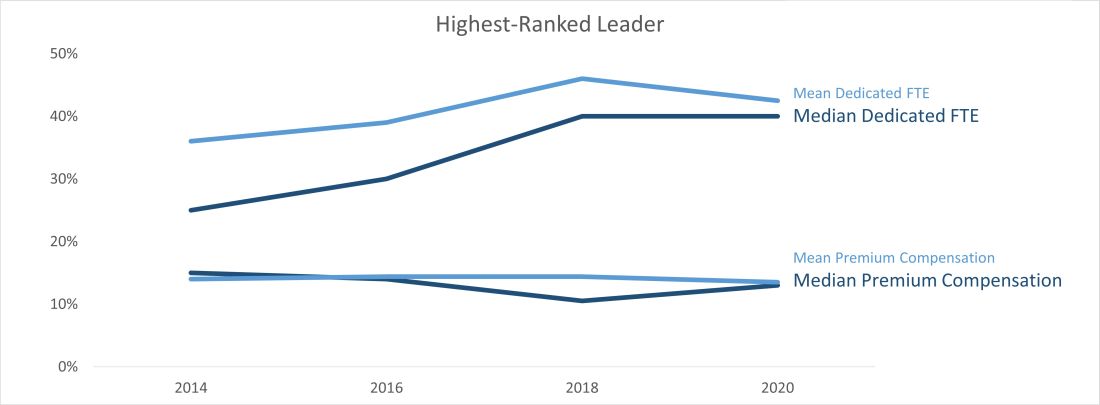

Highest-ranked leader dedicated FTE and premium compensation

Another pleasing trend is an increase in dedicated FTE for the highest-paid leader. Like any skill-set development, leadership requires the investment of deliberate practice, financial acumen, negotiation skills, and increased vulnerability. Time helps way more in developing these skill sets than money. SoHM trends show increase in dedicated FTE for the highest physician leader over the years and static premium compensation.

At last, we can say median leadership is always better than “mean” leadership in skewed data. Pun apart, every group needs leadership, and SoHM offers a nice window to the trends in leadership amongst many practice groups. It is a valuable resource for every group.

Dr. Chadha is chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is finishing his first tenure in the Practice Analysis Committee. He is often found spending a lot more than required time with spreadsheets and graphs.

Reference

1. 2020 State of Hospital Medicine. www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

The differences between the mean and median of leadership data

The differences between the mean and median of leadership data

Let me apologize for misleading all of you; this is not an article about malignant physician leaders; instead, it goes over the numbers and trends uncovered by the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM).1 The hospital medicine leader ends up doing many tasks like planning, growth, collaboration, finance, recruiting, scheduling, onboarding, coaching, and most near and dear to our hearts, putting out the fires and conflict resolution.

Ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE

If my pun has already put you off, you can avoid reading the rest of the piece and go to the 2020 SoHM to look at pages 52 (Table 3.7c), 121 (Table 4.7c), and 166 (Table 5.7c). It has a newly added table (3.7c), and it is phenomenal; it is the ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE. As an avid user of SoHM, I always ended up doing a makeshift calculation to “guesstimate” this number. Now that we have it calculated for us and the ultimate revelation lies in its narrow range across all groups. We might differ in the region, employment type, academics, teaching, or size, but this range is relatively narrow.

The median ratio of leadership FTE to total FTE lies between 2% and 5% in pediatric groups and between 3% and 6% for most adult groups. The only two outliers are on the adult side, with less than 5 FTE and multistate management companies. The higher median for the less than 5 FTE group size is understandable because of the small number of hospitalist FTEs that the leader’s time must be spread over. Even a small amount of dedicated leadership time will result in a high ratio of leader time to hospitalist clinical time if the group is very small. The multistate management company is probably a result of multiple layers of physician leadership (for example, regional medical directors) and travel-related time adjustments. Still, it raises the question of why the local leadership is not developed to decrease the leadership cost and better access.

Another helpful pattern is the decrease in standard deviation with the increase in group size. The hospital medicine leaders and CEOs of the hospital need to watch this number closely; any extremes on high or low side would be indicators for a deep dive in leadership structure and health.

Total number and total dedicated FTE for all physician leaders

Once we start seeing the differences between the mean and median of leadership data, we can see the median is relatively static while the mean has increased year after year and took a big jump in the 2020 SoHM. The chart below shows trends for the number of individuals in leadership positions (“Total No” and total FTEs allocated to leadership (“Total FTE”) over the last several surveys. The data is heavily skewed toward the right (positive); so, it makes sense to use the median in this case rather than mean. A few factors could explain the right skew of data.

- Large groups of 30 or more hospitalists are increasing, and so is their leadership need.

- There is more recognition of the need for dedicated leadership individuals and FTE.

- The leadership is getting less concentrated among just one or a few leaders.

- Outliers on the high side.

- Lower bounds of 0 or 0.1 FTE.

Highest-ranked leader dedicated FTE and premium compensation

Another pleasing trend is an increase in dedicated FTE for the highest-paid leader. Like any skill-set development, leadership requires the investment of deliberate practice, financial acumen, negotiation skills, and increased vulnerability. Time helps way more in developing these skill sets than money. SoHM trends show increase in dedicated FTE for the highest physician leader over the years and static premium compensation.

At last, we can say median leadership is always better than “mean” leadership in skewed data. Pun apart, every group needs leadership, and SoHM offers a nice window to the trends in leadership amongst many practice groups. It is a valuable resource for every group.

Dr. Chadha is chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is finishing his first tenure in the Practice Analysis Committee. He is often found spending a lot more than required time with spreadsheets and graphs.

Reference

1. 2020 State of Hospital Medicine. www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

Let me apologize for misleading all of you; this is not an article about malignant physician leaders; instead, it goes over the numbers and trends uncovered by the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM).1 The hospital medicine leader ends up doing many tasks like planning, growth, collaboration, finance, recruiting, scheduling, onboarding, coaching, and most near and dear to our hearts, putting out the fires and conflict resolution.

Ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE

If my pun has already put you off, you can avoid reading the rest of the piece and go to the 2020 SoHM to look at pages 52 (Table 3.7c), 121 (Table 4.7c), and 166 (Table 5.7c). It has a newly added table (3.7c), and it is phenomenal; it is the ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE. As an avid user of SoHM, I always ended up doing a makeshift calculation to “guesstimate” this number. Now that we have it calculated for us and the ultimate revelation lies in its narrow range across all groups. We might differ in the region, employment type, academics, teaching, or size, but this range is relatively narrow.

The median ratio of leadership FTE to total FTE lies between 2% and 5% in pediatric groups and between 3% and 6% for most adult groups. The only two outliers are on the adult side, with less than 5 FTE and multistate management companies. The higher median for the less than 5 FTE group size is understandable because of the small number of hospitalist FTEs that the leader’s time must be spread over. Even a small amount of dedicated leadership time will result in a high ratio of leader time to hospitalist clinical time if the group is very small. The multistate management company is probably a result of multiple layers of physician leadership (for example, regional medical directors) and travel-related time adjustments. Still, it raises the question of why the local leadership is not developed to decrease the leadership cost and better access.

Another helpful pattern is the decrease in standard deviation with the increase in group size. The hospital medicine leaders and CEOs of the hospital need to watch this number closely; any extremes on high or low side would be indicators for a deep dive in leadership structure and health.

Total number and total dedicated FTE for all physician leaders

Once we start seeing the differences between the mean and median of leadership data, we can see the median is relatively static while the mean has increased year after year and took a big jump in the 2020 SoHM. The chart below shows trends for the number of individuals in leadership positions (“Total No” and total FTEs allocated to leadership (“Total FTE”) over the last several surveys. The data is heavily skewed toward the right (positive); so, it makes sense to use the median in this case rather than mean. A few factors could explain the right skew of data.

- Large groups of 30 or more hospitalists are increasing, and so is their leadership need.

- There is more recognition of the need for dedicated leadership individuals and FTE.

- The leadership is getting less concentrated among just one or a few leaders.

- Outliers on the high side.

- Lower bounds of 0 or 0.1 FTE.

Highest-ranked leader dedicated FTE and premium compensation

Another pleasing trend is an increase in dedicated FTE for the highest-paid leader. Like any skill-set development, leadership requires the investment of deliberate practice, financial acumen, negotiation skills, and increased vulnerability. Time helps way more in developing these skill sets than money. SoHM trends show increase in dedicated FTE for the highest physician leader over the years and static premium compensation.

At last, we can say median leadership is always better than “mean” leadership in skewed data. Pun apart, every group needs leadership, and SoHM offers a nice window to the trends in leadership amongst many practice groups. It is a valuable resource for every group.

Dr. Chadha is chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is finishing his first tenure in the Practice Analysis Committee. He is often found spending a lot more than required time with spreadsheets and graphs.

Reference

1. 2020 State of Hospital Medicine. www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.