User login

De-escalation of ABVD chemotherapy fails in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma

MILAN – Neither dacarbazine nor bleomycin can be safely omitted from ABVD chemotherapy without affecting efficacy in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to the final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD13 trial.

The primary endpoint of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 5 years was 93.1% after ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) chemotherapy, compared with 81.4% after ABV and 77.1% after AV.

All patients received two cycles of ABVD, ABV, AVD, or AV chemotherapy followed by 30 Gy involved-field radiation therapy.

"Dacarbazine cannot be omitted without considerable loss of efficacy," Dr. Karolin Behringer said at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The findings confirm the inferiority of the ABV and AV arms, which were prematurely closed in 2006 and 2005 after a safety analysis detected a strong increase in events in the two arms compared with standard ABVD.

The four-armed HD13 trial, however, also sought to answer whether the AVD regimen is equivalent to ABVD chemotherapy.

The 5-year FFTF rate with AVD was 89.2%, or 3.9 percentage points lower than with ABVD (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

This was largely due to more late relapses with AVD than with ABVD (37 vs. 20), said Dr. Behringer, of the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

As a result, AVD failed to meet the noninferiority test with a margin of 1.72 for hazard ratio, corresponding to a 6% difference in 5-year FFTF between ABVD and AVD.

"Bleomycin cannot be omitted with the predefined noninferiority margin of 6%," she said.

Importantly, the reduction in FFTF did not translate into poorer overall survival.

Five-year overall survival rates were 97.6% with ABVD, 94.1% with ABV, 97.6% with AVD, and 98.1% with AV, Dr. Behringer reported.

AVD patients had similar rates as those treated with ABVD chemotherapy as salvage therapy with stem cell transplantation (49% vs. 45%) or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone) chemotherapy (31% vs. 35%).

Patients in the AVD arm, however, experienced significantly less grade 3/4 toxicity than did those in the ABVD arm (26.3% vs. 32.7%; P = .03). Grade 3/4 events were similar in the ABV and AV arms (28.3% vs. 26.5%), she said.

The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

MILAN – Neither dacarbazine nor bleomycin can be safely omitted from ABVD chemotherapy without affecting efficacy in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to the final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD13 trial.

The primary endpoint of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 5 years was 93.1% after ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) chemotherapy, compared with 81.4% after ABV and 77.1% after AV.

All patients received two cycles of ABVD, ABV, AVD, or AV chemotherapy followed by 30 Gy involved-field radiation therapy.

"Dacarbazine cannot be omitted without considerable loss of efficacy," Dr. Karolin Behringer said at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The findings confirm the inferiority of the ABV and AV arms, which were prematurely closed in 2006 and 2005 after a safety analysis detected a strong increase in events in the two arms compared with standard ABVD.

The four-armed HD13 trial, however, also sought to answer whether the AVD regimen is equivalent to ABVD chemotherapy.

The 5-year FFTF rate with AVD was 89.2%, or 3.9 percentage points lower than with ABVD (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

This was largely due to more late relapses with AVD than with ABVD (37 vs. 20), said Dr. Behringer, of the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

As a result, AVD failed to meet the noninferiority test with a margin of 1.72 for hazard ratio, corresponding to a 6% difference in 5-year FFTF between ABVD and AVD.

"Bleomycin cannot be omitted with the predefined noninferiority margin of 6%," she said.

Importantly, the reduction in FFTF did not translate into poorer overall survival.

Five-year overall survival rates were 97.6% with ABVD, 94.1% with ABV, 97.6% with AVD, and 98.1% with AV, Dr. Behringer reported.

AVD patients had similar rates as those treated with ABVD chemotherapy as salvage therapy with stem cell transplantation (49% vs. 45%) or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone) chemotherapy (31% vs. 35%).

Patients in the AVD arm, however, experienced significantly less grade 3/4 toxicity than did those in the ABVD arm (26.3% vs. 32.7%; P = .03). Grade 3/4 events were similar in the ABV and AV arms (28.3% vs. 26.5%), she said.

The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

MILAN – Neither dacarbazine nor bleomycin can be safely omitted from ABVD chemotherapy without affecting efficacy in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to the final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD13 trial.

The primary endpoint of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 5 years was 93.1% after ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) chemotherapy, compared with 81.4% after ABV and 77.1% after AV.

All patients received two cycles of ABVD, ABV, AVD, or AV chemotherapy followed by 30 Gy involved-field radiation therapy.

"Dacarbazine cannot be omitted without considerable loss of efficacy," Dr. Karolin Behringer said at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The findings confirm the inferiority of the ABV and AV arms, which were prematurely closed in 2006 and 2005 after a safety analysis detected a strong increase in events in the two arms compared with standard ABVD.

The four-armed HD13 trial, however, also sought to answer whether the AVD regimen is equivalent to ABVD chemotherapy.

The 5-year FFTF rate with AVD was 89.2%, or 3.9 percentage points lower than with ABVD (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

This was largely due to more late relapses with AVD than with ABVD (37 vs. 20), said Dr. Behringer, of the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

As a result, AVD failed to meet the noninferiority test with a margin of 1.72 for hazard ratio, corresponding to a 6% difference in 5-year FFTF between ABVD and AVD.

"Bleomycin cannot be omitted with the predefined noninferiority margin of 6%," she said.

Importantly, the reduction in FFTF did not translate into poorer overall survival.

Five-year overall survival rates were 97.6% with ABVD, 94.1% with ABV, 97.6% with AVD, and 98.1% with AV, Dr. Behringer reported.

AVD patients had similar rates as those treated with ABVD chemotherapy as salvage therapy with stem cell transplantation (49% vs. 45%) or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone) chemotherapy (31% vs. 35%).

Patients in the AVD arm, however, experienced significantly less grade 3/4 toxicity than did those in the ABVD arm (26.3% vs. 32.7%; P = .03). Grade 3/4 events were similar in the ABV and AV arms (28.3% vs. 26.5%), she said.

The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE EHA CONGRESS

Major finding: The 5-year FFTF rate was 93.1% with ABVD and 89.2% with AVD (HR, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

Data source: A prospective, randomized study in 1,710 patients with early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Key clinical point: Dacarbazine and bleomycin should not be omitted from ABVD chemotherapy in the treatment of early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Disclosures: The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

De-escalation of ABVD chemotherapy fails in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma

MILAN – Neither dacarbazine nor bleomycin can be safely omitted from ABVD chemotherapy without affecting efficacy in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to the final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD13 trial.

The primary endpoint of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 5 years was 93.1% after ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) chemotherapy, compared with 81.4% after ABV and 77.1% after AV.

All patients received two cycles of ABVD, ABV, AVD, or AV chemotherapy followed by 30 Gy involved-field radiation therapy.

"Dacarbazine cannot be omitted without considerable loss of efficacy," Dr. Karolin Behringer said at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The findings confirm the inferiority of the ABV and AV arms, which were prematurely closed in 2006 and 2005 after a safety analysis detected a strong increase in events in the two arms compared with standard ABVD.

The four-armed HD13 trial, however, also sought to answer whether the AVD regimen is equivalent to ABVD chemotherapy.

The 5-year FFTF rate with AVD was 89.2%, or 3.9 percentage points lower than with ABVD (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

This was largely due to more late relapses with AVD than with ABVD (37 vs. 20), said Dr. Behringer, of the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

As a result, AVD failed to meet the noninferiority test with a margin of 1.72 for hazard ratio, corresponding to a 6% difference in 5-year FFTF between ABVD and AVD.

"Bleomycin cannot be omitted with the predefined noninferiority margin of 6%," she said.

Importantly, the reduction in FFTF did not translate into poorer overall survival.

Five-year overall survival rates were 97.6% with ABVD, 94.1% with ABV, 97.6% with AVD, and 98.1% with AV, Dr. Behringer reported.

AVD patients had similar rates as those treated with ABVD chemotherapy as salvage therapy with stem cell transplantation (49% vs. 45%) or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone) chemotherapy (31% vs. 35%).

Patients in the AVD arm, however, experienced significantly less grade 3/4 toxicity than did those in the ABVD arm (26.3% vs. 32.7%; P = .03). Grade 3/4 events were similar in the ABV and AV arms (28.3% vs. 26.5%), she said.

The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

MILAN – Neither dacarbazine nor bleomycin can be safely omitted from ABVD chemotherapy without affecting efficacy in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to the final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD13 trial.

The primary endpoint of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 5 years was 93.1% after ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) chemotherapy, compared with 81.4% after ABV and 77.1% after AV.

All patients received two cycles of ABVD, ABV, AVD, or AV chemotherapy followed by 30 Gy involved-field radiation therapy.

"Dacarbazine cannot be omitted without considerable loss of efficacy," Dr. Karolin Behringer said at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The findings confirm the inferiority of the ABV and AV arms, which were prematurely closed in 2006 and 2005 after a safety analysis detected a strong increase in events in the two arms compared with standard ABVD.

The four-armed HD13 trial, however, also sought to answer whether the AVD regimen is equivalent to ABVD chemotherapy.

The 5-year FFTF rate with AVD was 89.2%, or 3.9 percentage points lower than with ABVD (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

This was largely due to more late relapses with AVD than with ABVD (37 vs. 20), said Dr. Behringer, of the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

As a result, AVD failed to meet the noninferiority test with a margin of 1.72 for hazard ratio, corresponding to a 6% difference in 5-year FFTF between ABVD and AVD.

"Bleomycin cannot be omitted with the predefined noninferiority margin of 6%," she said.

Importantly, the reduction in FFTF did not translate into poorer overall survival.

Five-year overall survival rates were 97.6% with ABVD, 94.1% with ABV, 97.6% with AVD, and 98.1% with AV, Dr. Behringer reported.

AVD patients had similar rates as those treated with ABVD chemotherapy as salvage therapy with stem cell transplantation (49% vs. 45%) or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone) chemotherapy (31% vs. 35%).

Patients in the AVD arm, however, experienced significantly less grade 3/4 toxicity than did those in the ABVD arm (26.3% vs. 32.7%; P = .03). Grade 3/4 events were similar in the ABV and AV arms (28.3% vs. 26.5%), she said.

The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

MILAN – Neither dacarbazine nor bleomycin can be safely omitted from ABVD chemotherapy without affecting efficacy in early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to the final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD13 trial.

The primary endpoint of freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 5 years was 93.1% after ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) chemotherapy, compared with 81.4% after ABV and 77.1% after AV.

All patients received two cycles of ABVD, ABV, AVD, or AV chemotherapy followed by 30 Gy involved-field radiation therapy.

"Dacarbazine cannot be omitted without considerable loss of efficacy," Dr. Karolin Behringer said at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The findings confirm the inferiority of the ABV and AV arms, which were prematurely closed in 2006 and 2005 after a safety analysis detected a strong increase in events in the two arms compared with standard ABVD.

The four-armed HD13 trial, however, also sought to answer whether the AVD regimen is equivalent to ABVD chemotherapy.

The 5-year FFTF rate with AVD was 89.2%, or 3.9 percentage points lower than with ABVD (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

This was largely due to more late relapses with AVD than with ABVD (37 vs. 20), said Dr. Behringer, of the University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

As a result, AVD failed to meet the noninferiority test with a margin of 1.72 for hazard ratio, corresponding to a 6% difference in 5-year FFTF between ABVD and AVD.

"Bleomycin cannot be omitted with the predefined noninferiority margin of 6%," she said.

Importantly, the reduction in FFTF did not translate into poorer overall survival.

Five-year overall survival rates were 97.6% with ABVD, 94.1% with ABV, 97.6% with AVD, and 98.1% with AV, Dr. Behringer reported.

AVD patients had similar rates as those treated with ABVD chemotherapy as salvage therapy with stem cell transplantation (49% vs. 45%) or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, procarbazine, and prednisone) chemotherapy (31% vs. 35%).

Patients in the AVD arm, however, experienced significantly less grade 3/4 toxicity than did those in the ABVD arm (26.3% vs. 32.7%; P = .03). Grade 3/4 events were similar in the ABV and AV arms (28.3% vs. 26.5%), she said.

The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE EHA CONGRESS

Major finding: The 5-year FFTF rate was 93.1% with ABVD and 89.2% with AVD (HR, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.00-2.26).

Data source: A prospective, randomized study in 1,710 patients with early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Key clinical point: Dacarbazine and bleomycin should not be omitted from ABVD chemotherapy in the treatment of early-stage, favorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Disclosures: The study was conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Dr. Behringer reported having no financial disclosures.

Inhibitor gets accelerated approval for PTCL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval for belinostat (Beleodaq) to treat relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Belinostat is a histone deacetylase inhibitor with antineoplastic activity. The drug works by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, promoting cellular differentiation, and inhibiting angiogenesis.

The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows for approval of a drug based on surrogate or intermediate endpoints reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit for patients with serious conditions with unmet medical needs.

Drugs receiving accelerated approval are subject to confirmatory trials verifying clinical benefit.

The FDA granted belinostat accelerated approval based on results of a phase 2 trial, which included 129 patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL. All patients received belinostat until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

About 26% of patients achieved a complete or partial response. The most common side effects were nausea, fatigue, pyrexia, anemia, and vomiting.

“[Belinostat] is the third drug that has been approved since 2009 for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA granted accelerated approval to pralatrexate (Folotyn) in 2009 for use in patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL and romidepsin (Istodax) in 2011 for PTCL patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

Beleodaq and Folotyn are marketed by Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., based in Henderson, Nevada. Istodax is marketed by Celgene Corporation based in Summit, New Jersey. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval for belinostat (Beleodaq) to treat relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Belinostat is a histone deacetylase inhibitor with antineoplastic activity. The drug works by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, promoting cellular differentiation, and inhibiting angiogenesis.

The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows for approval of a drug based on surrogate or intermediate endpoints reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit for patients with serious conditions with unmet medical needs.

Drugs receiving accelerated approval are subject to confirmatory trials verifying clinical benefit.

The FDA granted belinostat accelerated approval based on results of a phase 2 trial, which included 129 patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL. All patients received belinostat until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

About 26% of patients achieved a complete or partial response. The most common side effects were nausea, fatigue, pyrexia, anemia, and vomiting.

“[Belinostat] is the third drug that has been approved since 2009 for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA granted accelerated approval to pralatrexate (Folotyn) in 2009 for use in patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL and romidepsin (Istodax) in 2011 for PTCL patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

Beleodaq and Folotyn are marketed by Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., based in Henderson, Nevada. Istodax is marketed by Celgene Corporation based in Summit, New Jersey. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval for belinostat (Beleodaq) to treat relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Belinostat is a histone deacetylase inhibitor with antineoplastic activity. The drug works by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, promoting cellular differentiation, and inhibiting angiogenesis.

The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows for approval of a drug based on surrogate or intermediate endpoints reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit for patients with serious conditions with unmet medical needs.

Drugs receiving accelerated approval are subject to confirmatory trials verifying clinical benefit.

The FDA granted belinostat accelerated approval based on results of a phase 2 trial, which included 129 patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL. All patients received belinostat until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

About 26% of patients achieved a complete or partial response. The most common side effects were nausea, fatigue, pyrexia, anemia, and vomiting.

“[Belinostat] is the third drug that has been approved since 2009 for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA granted accelerated approval to pralatrexate (Folotyn) in 2009 for use in patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL and romidepsin (Istodax) in 2011 for PTCL patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

Beleodaq and Folotyn are marketed by Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., based in Henderson, Nevada. Istodax is marketed by Celgene Corporation based in Summit, New Jersey. ![]()

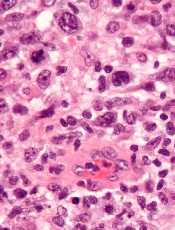

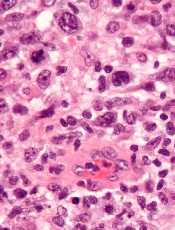

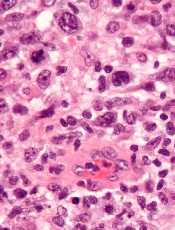

FISH may help predict survival in ALCL

Researchers have discovered 3 subgroups of ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) that have markedly different survival rates, according to a paper published in Blood.

They found that ALCL patients with TP63 rearrangements had a 17% chance of living 5 years beyond diagnosis, compared to 90% of patients who had DUSP22 rearrangements.

A third group of patients, those with neither rearrangement, had a 42% survival rate.

The researchers noted that these subgroups cannot be differentiated by routine pathology but can be identified via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

“This is the first study to demonstrate unequivocal genetic and clinical heterogeneity among systemic ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphomas,” said study author Andrew L. Feldman, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Most strikingly, patients with DUSP22-rearranged ALCL had excellent overall survival rates, while patients with TP63-rearranged ALCL had dismal outcomes and nearly always failed standard therapy.”

Currently, all ALK-negative ALCLs are treated the same, using chemotherapy and, in some institutions, stem cell transplantation. But these new findings make a case for additional testing and possible changes to the standard of care.

“This is a great example of where individualized medicine can make a difference,” Dr Feldman said. “Patients whose chance of surviving is 1 in 6 are receiving the same therapy as patients whose odds are 9 in 10. Developing tests that identify how tumors are different is a critical step toward being able to tailor therapy to each individual patient.”

Therefore, Dr Feldman and his colleagues recommend performing FISH in all patients with ALK-negative ALCL.

To learn more about testing for DUSP22 and TP63:

- 6p25.3 FISH (DUSP22/IRF4): http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/60506

- 3q28 FISH (TP63): http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/70014.

Researchers have discovered 3 subgroups of ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) that have markedly different survival rates, according to a paper published in Blood.

They found that ALCL patients with TP63 rearrangements had a 17% chance of living 5 years beyond diagnosis, compared to 90% of patients who had DUSP22 rearrangements.

A third group of patients, those with neither rearrangement, had a 42% survival rate.

The researchers noted that these subgroups cannot be differentiated by routine pathology but can be identified via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

“This is the first study to demonstrate unequivocal genetic and clinical heterogeneity among systemic ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphomas,” said study author Andrew L. Feldman, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Most strikingly, patients with DUSP22-rearranged ALCL had excellent overall survival rates, while patients with TP63-rearranged ALCL had dismal outcomes and nearly always failed standard therapy.”

Currently, all ALK-negative ALCLs are treated the same, using chemotherapy and, in some institutions, stem cell transplantation. But these new findings make a case for additional testing and possible changes to the standard of care.

“This is a great example of where individualized medicine can make a difference,” Dr Feldman said. “Patients whose chance of surviving is 1 in 6 are receiving the same therapy as patients whose odds are 9 in 10. Developing tests that identify how tumors are different is a critical step toward being able to tailor therapy to each individual patient.”

Therefore, Dr Feldman and his colleagues recommend performing FISH in all patients with ALK-negative ALCL.

To learn more about testing for DUSP22 and TP63:

- 6p25.3 FISH (DUSP22/IRF4): http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/60506

- 3q28 FISH (TP63): http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/70014.

Researchers have discovered 3 subgroups of ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) that have markedly different survival rates, according to a paper published in Blood.

They found that ALCL patients with TP63 rearrangements had a 17% chance of living 5 years beyond diagnosis, compared to 90% of patients who had DUSP22 rearrangements.

A third group of patients, those with neither rearrangement, had a 42% survival rate.

The researchers noted that these subgroups cannot be differentiated by routine pathology but can be identified via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

“This is the first study to demonstrate unequivocal genetic and clinical heterogeneity among systemic ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphomas,” said study author Andrew L. Feldman, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Most strikingly, patients with DUSP22-rearranged ALCL had excellent overall survival rates, while patients with TP63-rearranged ALCL had dismal outcomes and nearly always failed standard therapy.”

Currently, all ALK-negative ALCLs are treated the same, using chemotherapy and, in some institutions, stem cell transplantation. But these new findings make a case for additional testing and possible changes to the standard of care.

“This is a great example of where individualized medicine can make a difference,” Dr Feldman said. “Patients whose chance of surviving is 1 in 6 are receiving the same therapy as patients whose odds are 9 in 10. Developing tests that identify how tumors are different is a critical step toward being able to tailor therapy to each individual patient.”

Therefore, Dr Feldman and his colleagues recommend performing FISH in all patients with ALK-negative ALCL.

To learn more about testing for DUSP22 and TP63:

- 6p25.3 FISH (DUSP22/IRF4): http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/60506

- 3q28 FISH (TP63): http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/70014.

Study validates drug’s efficacy in CLL/SLL

MILAN—Results of the phase 3 RESONATE trial suggest ibrutinib can improve response and survival rates in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), when compared to ofatumumab.

Ibrutinib conferred these benefits irrespective of baseline clinical characteristics or molecular features, including 17p deletion.

Atrial fibrillation and bleeding-related events were more common with ibrutinib. But the rate of serious adverse events was similar between the treatment arms.

About 86% of patients remained on ibrutinib at last analysis, and roughly 29% of patients initially randomized to ofatumumab crossed over to the ibrutinib arm after disease progression.

“This study undoubtedly confirms that ibrutinib is a very effective agent—as a single-agent—in relapsed CLL patients,” said investigator Peter Hillmen, MD, PhD, of The Leeds Teaching Hospitals in the UK.

Dr Hillmen presented these results at the 19th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) as abstract S693. The RESONATE trial was sponsored by Pharmacyclics and Janssen, the companies developing ibrutinib.

The trial included 391 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL. They were randomized to receive oral ibrutinib at 420 mg once daily until progression or unacceptable toxicity (n=195) or intravenous ofatumumab at an initial dose of 300 mg, followed by 11 doses of 2000 mg (n=196). Patients in the ofatumumab arm were allowed to cross over to ibrutinib if they progressed (n=57).

The median age in both treatment arms was 67. Overall, roughly 50% of patients had received 3 or more prior therapies, including purine analogs, alkylating agents, and anti-CD20 antibodies. The proportion of patients with del17p was similar between the treatment arms—32% in the ibrutinib arm and 33% in the ofatumumab arm.

Response and survival

At the time of interim analysis, patients’ median time on study was 9.4 months. The best overall response among evaluable patients was 78% in the ibrutinib arm and 11% in the ofatumumab arm, according to an independent review committee.

In addition, ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS). The median PFS was 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm and was not reached in the ibrutinib arm (P<0.0001). The improvement in PFS represents a 78% reduction in the risk of progression or death.

Dr Hillmen noted that PFS favored ibrutinib regardless of baseline characteristics such as refractoriness to purine analogs, del17p, age, gender, Rai stage, bulky disease, number of prior treatments, del11q, B2 microglobulin, and IgVH mutation status.

Ibrutinib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) as well. The median OS was not reached in either arm, but the hazard ratio was 0.434 (P=0.0049). The improvement in OS represents a 56% reduction in the risk of death in patients treated with ibrutinib.

Adverse events

Dr Hillmen pointed out that the median treatment duration was 8.6 months for ibrutinib and 5.3 months for ofatumumab, and this difference confounds the assessment of side effects.

Nevertheless, nearly all patients in both treatment arms experienced adverse events—99% in the ibrutinib arm and 98% in the ofatumumab arm. Grade 3/4 events occurred in 51% and 39% of patients, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation of any grade was more common in the ibrutinib arm (n=10) than in the ofatumumab arm (n=1), but 5 of the ibrutinib-treated patients had a prior history of atrial fibrillation. Bleeding-related events were also more common with ibrutinib (44% vs 12%), as were diarrhea (48% vs 18%) and arthralgia (17% vs 7%).

Events more common in the ofatumumab arm included infusion-related reactions (28% vs 0%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (13% vs 4%), urticaria (6% vs 1%), night sweats (13% vs 5%), and pruritus (9% vs 4%). ![]()

MILAN—Results of the phase 3 RESONATE trial suggest ibrutinib can improve response and survival rates in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), when compared to ofatumumab.

Ibrutinib conferred these benefits irrespective of baseline clinical characteristics or molecular features, including 17p deletion.

Atrial fibrillation and bleeding-related events were more common with ibrutinib. But the rate of serious adverse events was similar between the treatment arms.

About 86% of patients remained on ibrutinib at last analysis, and roughly 29% of patients initially randomized to ofatumumab crossed over to the ibrutinib arm after disease progression.

“This study undoubtedly confirms that ibrutinib is a very effective agent—as a single-agent—in relapsed CLL patients,” said investigator Peter Hillmen, MD, PhD, of The Leeds Teaching Hospitals in the UK.

Dr Hillmen presented these results at the 19th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) as abstract S693. The RESONATE trial was sponsored by Pharmacyclics and Janssen, the companies developing ibrutinib.

The trial included 391 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL. They were randomized to receive oral ibrutinib at 420 mg once daily until progression or unacceptable toxicity (n=195) or intravenous ofatumumab at an initial dose of 300 mg, followed by 11 doses of 2000 mg (n=196). Patients in the ofatumumab arm were allowed to cross over to ibrutinib if they progressed (n=57).

The median age in both treatment arms was 67. Overall, roughly 50% of patients had received 3 or more prior therapies, including purine analogs, alkylating agents, and anti-CD20 antibodies. The proportion of patients with del17p was similar between the treatment arms—32% in the ibrutinib arm and 33% in the ofatumumab arm.

Response and survival

At the time of interim analysis, patients’ median time on study was 9.4 months. The best overall response among evaluable patients was 78% in the ibrutinib arm and 11% in the ofatumumab arm, according to an independent review committee.

In addition, ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS). The median PFS was 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm and was not reached in the ibrutinib arm (P<0.0001). The improvement in PFS represents a 78% reduction in the risk of progression or death.

Dr Hillmen noted that PFS favored ibrutinib regardless of baseline characteristics such as refractoriness to purine analogs, del17p, age, gender, Rai stage, bulky disease, number of prior treatments, del11q, B2 microglobulin, and IgVH mutation status.

Ibrutinib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) as well. The median OS was not reached in either arm, but the hazard ratio was 0.434 (P=0.0049). The improvement in OS represents a 56% reduction in the risk of death in patients treated with ibrutinib.

Adverse events

Dr Hillmen pointed out that the median treatment duration was 8.6 months for ibrutinib and 5.3 months for ofatumumab, and this difference confounds the assessment of side effects.

Nevertheless, nearly all patients in both treatment arms experienced adverse events—99% in the ibrutinib arm and 98% in the ofatumumab arm. Grade 3/4 events occurred in 51% and 39% of patients, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation of any grade was more common in the ibrutinib arm (n=10) than in the ofatumumab arm (n=1), but 5 of the ibrutinib-treated patients had a prior history of atrial fibrillation. Bleeding-related events were also more common with ibrutinib (44% vs 12%), as were diarrhea (48% vs 18%) and arthralgia (17% vs 7%).

Events more common in the ofatumumab arm included infusion-related reactions (28% vs 0%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (13% vs 4%), urticaria (6% vs 1%), night sweats (13% vs 5%), and pruritus (9% vs 4%). ![]()

MILAN—Results of the phase 3 RESONATE trial suggest ibrutinib can improve response and survival rates in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), when compared to ofatumumab.

Ibrutinib conferred these benefits irrespective of baseline clinical characteristics or molecular features, including 17p deletion.

Atrial fibrillation and bleeding-related events were more common with ibrutinib. But the rate of serious adverse events was similar between the treatment arms.

About 86% of patients remained on ibrutinib at last analysis, and roughly 29% of patients initially randomized to ofatumumab crossed over to the ibrutinib arm after disease progression.

“This study undoubtedly confirms that ibrutinib is a very effective agent—as a single-agent—in relapsed CLL patients,” said investigator Peter Hillmen, MD, PhD, of The Leeds Teaching Hospitals in the UK.

Dr Hillmen presented these results at the 19th Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) as abstract S693. The RESONATE trial was sponsored by Pharmacyclics and Janssen, the companies developing ibrutinib.

The trial included 391 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL. They were randomized to receive oral ibrutinib at 420 mg once daily until progression or unacceptable toxicity (n=195) or intravenous ofatumumab at an initial dose of 300 mg, followed by 11 doses of 2000 mg (n=196). Patients in the ofatumumab arm were allowed to cross over to ibrutinib if they progressed (n=57).

The median age in both treatment arms was 67. Overall, roughly 50% of patients had received 3 or more prior therapies, including purine analogs, alkylating agents, and anti-CD20 antibodies. The proportion of patients with del17p was similar between the treatment arms—32% in the ibrutinib arm and 33% in the ofatumumab arm.

Response and survival

At the time of interim analysis, patients’ median time on study was 9.4 months. The best overall response among evaluable patients was 78% in the ibrutinib arm and 11% in the ofatumumab arm, according to an independent review committee.

In addition, ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS). The median PFS was 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm and was not reached in the ibrutinib arm (P<0.0001). The improvement in PFS represents a 78% reduction in the risk of progression or death.

Dr Hillmen noted that PFS favored ibrutinib regardless of baseline characteristics such as refractoriness to purine analogs, del17p, age, gender, Rai stage, bulky disease, number of prior treatments, del11q, B2 microglobulin, and IgVH mutation status.

Ibrutinib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) as well. The median OS was not reached in either arm, but the hazard ratio was 0.434 (P=0.0049). The improvement in OS represents a 56% reduction in the risk of death in patients treated with ibrutinib.

Adverse events

Dr Hillmen pointed out that the median treatment duration was 8.6 months for ibrutinib and 5.3 months for ofatumumab, and this difference confounds the assessment of side effects.

Nevertheless, nearly all patients in both treatment arms experienced adverse events—99% in the ibrutinib arm and 98% in the ofatumumab arm. Grade 3/4 events occurred in 51% and 39% of patients, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation of any grade was more common in the ibrutinib arm (n=10) than in the ofatumumab arm (n=1), but 5 of the ibrutinib-treated patients had a prior history of atrial fibrillation. Bleeding-related events were also more common with ibrutinib (44% vs 12%), as were diarrhea (48% vs 18%) and arthralgia (17% vs 7%).

Events more common in the ofatumumab arm included infusion-related reactions (28% vs 0%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (13% vs 4%), urticaria (6% vs 1%), night sweats (13% vs 5%), and pruritus (9% vs 4%). ![]()

HIV+ cancer patients more likely to go untreated

lymphocyte; Credit: CDC

Cancer patients infected with HIV are less likely than their uninfected peers to receive cancer treatment, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Results showed that HIV-positive patients were roughly twice as likely to go untreated for lymphomas and other cancers.

The researchers believe a lack of clinical trial data and treatment guidelines for HIV patients with cancer may contribute to this health disparity.

To assess the role of HIV status on cancer treatment, Gita Suneja, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and her colleagues used data from the National Cancer Institute’s HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study.

This included 3045 HIV-infected patients and 1,087,648 uninfected patients. The patients had been diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, or cervical, lung, anal, prostate, colorectal, or breast cancer from 1996 through 2010.

For each cancer type, the researchers assessed the relationship between HIV status and cancer treatment, adjusted for cancer stage, sex, age at cancer diagnosis, race/ethnicity, year of cancer diagnosis, and US state.

For all but 1 cancer type, there was a significantly higher proportion of HIV-infected patients who did not receive cancer treatment when compared with uninfected patients.

The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were 1.67 for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 1.77 for Hodgkin lymphoma, 1.60 for cervical cancer, 1.79 for prostate cancer, 1.81 for breast cancer, 2.18 for lung cancer, and 2.27 for colorectal cancer.

Anal cancer was the only malignancy for which HIV status did not appear to impact treatment. The aOR was 1.01.

Among HIV-infected individuals, factors independently associated with a lack of cancer treatment included low CD4 count, male sex with injection drug use as mode of HIV exposure, age 45 to 64 years, black race, and distant or unknown cancer stage.

“In my clinical experience, I have seen uncertainty surrounding treatment of HIV-infected cancer patients,” Dr Suneja said. “Patients with HIV have typically been excluded from clinical trials, and, therefore, oncologists do not know if the best available treatments are equally safe and effective in those with HIV.”

“Many oncologists rely on guidelines based on such trials for treatment decision-making, and, in the absence of guidance, they may elect not to treat HIV-infected cancer patients due to concerns about adverse side effects or poor survival. This could help explain, in part, why many HIV-positive cancer patients are not receiving appropriate cancer care.”

Therefore, Dr Suneja and her colleagues recommend that cancer trials begin enrolling HIV-infected patients and cancer management guidelines incorporate recommendations for HIV-infected patients. ![]()

lymphocyte; Credit: CDC

Cancer patients infected with HIV are less likely than their uninfected peers to receive cancer treatment, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Results showed that HIV-positive patients were roughly twice as likely to go untreated for lymphomas and other cancers.

The researchers believe a lack of clinical trial data and treatment guidelines for HIV patients with cancer may contribute to this health disparity.

To assess the role of HIV status on cancer treatment, Gita Suneja, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and her colleagues used data from the National Cancer Institute’s HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study.

This included 3045 HIV-infected patients and 1,087,648 uninfected patients. The patients had been diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, or cervical, lung, anal, prostate, colorectal, or breast cancer from 1996 through 2010.

For each cancer type, the researchers assessed the relationship between HIV status and cancer treatment, adjusted for cancer stage, sex, age at cancer diagnosis, race/ethnicity, year of cancer diagnosis, and US state.

For all but 1 cancer type, there was a significantly higher proportion of HIV-infected patients who did not receive cancer treatment when compared with uninfected patients.

The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were 1.67 for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 1.77 for Hodgkin lymphoma, 1.60 for cervical cancer, 1.79 for prostate cancer, 1.81 for breast cancer, 2.18 for lung cancer, and 2.27 for colorectal cancer.

Anal cancer was the only malignancy for which HIV status did not appear to impact treatment. The aOR was 1.01.

Among HIV-infected individuals, factors independently associated with a lack of cancer treatment included low CD4 count, male sex with injection drug use as mode of HIV exposure, age 45 to 64 years, black race, and distant or unknown cancer stage.

“In my clinical experience, I have seen uncertainty surrounding treatment of HIV-infected cancer patients,” Dr Suneja said. “Patients with HIV have typically been excluded from clinical trials, and, therefore, oncologists do not know if the best available treatments are equally safe and effective in those with HIV.”

“Many oncologists rely on guidelines based on such trials for treatment decision-making, and, in the absence of guidance, they may elect not to treat HIV-infected cancer patients due to concerns about adverse side effects or poor survival. This could help explain, in part, why many HIV-positive cancer patients are not receiving appropriate cancer care.”

Therefore, Dr Suneja and her colleagues recommend that cancer trials begin enrolling HIV-infected patients and cancer management guidelines incorporate recommendations for HIV-infected patients. ![]()

lymphocyte; Credit: CDC

Cancer patients infected with HIV are less likely than their uninfected peers to receive cancer treatment, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Results showed that HIV-positive patients were roughly twice as likely to go untreated for lymphomas and other cancers.

The researchers believe a lack of clinical trial data and treatment guidelines for HIV patients with cancer may contribute to this health disparity.

To assess the role of HIV status on cancer treatment, Gita Suneja, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and her colleagues used data from the National Cancer Institute’s HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study.

This included 3045 HIV-infected patients and 1,087,648 uninfected patients. The patients had been diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, or cervical, lung, anal, prostate, colorectal, or breast cancer from 1996 through 2010.

For each cancer type, the researchers assessed the relationship between HIV status and cancer treatment, adjusted for cancer stage, sex, age at cancer diagnosis, race/ethnicity, year of cancer diagnosis, and US state.

For all but 1 cancer type, there was a significantly higher proportion of HIV-infected patients who did not receive cancer treatment when compared with uninfected patients.

The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were 1.67 for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 1.77 for Hodgkin lymphoma, 1.60 for cervical cancer, 1.79 for prostate cancer, 1.81 for breast cancer, 2.18 for lung cancer, and 2.27 for colorectal cancer.

Anal cancer was the only malignancy for which HIV status did not appear to impact treatment. The aOR was 1.01.

Among HIV-infected individuals, factors independently associated with a lack of cancer treatment included low CD4 count, male sex with injection drug use as mode of HIV exposure, age 45 to 64 years, black race, and distant or unknown cancer stage.

“In my clinical experience, I have seen uncertainty surrounding treatment of HIV-infected cancer patients,” Dr Suneja said. “Patients with HIV have typically been excluded from clinical trials, and, therefore, oncologists do not know if the best available treatments are equally safe and effective in those with HIV.”

“Many oncologists rely on guidelines based on such trials for treatment decision-making, and, in the absence of guidance, they may elect not to treat HIV-infected cancer patients due to concerns about adverse side effects or poor survival. This could help explain, in part, why many HIV-positive cancer patients are not receiving appropriate cancer care.”

Therefore, Dr Suneja and her colleagues recommend that cancer trials begin enrolling HIV-infected patients and cancer management guidelines incorporate recommendations for HIV-infected patients. ![]()

Enhancing gene delivery to HSCs

Credit: Chad McNeeley

Scientists say they’ve overcome a major hurdle to developing gene therapies for blood disorders.

They found the drug rapamycin could help them bypass the natural defenses of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and deliver therapeutic doses of disease-fighting genes, without compromising HSC function.

The team believes this discovery could lead to more effective and affordable long-term treatments for disorders such as leukemia and sickle cell anemia.

Bruce Torbett, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues reported their findings in Blood.

Past research showed that HIV vectors can deliver genes to HSCs. However, when scientists extract HSCs from the body for gene therapy, HIV vectors are usually able to deliver genes to about 30% to 40% of the cells.

For leukemia, leukodystrophy, or genetic diseases where treatment requires a reasonable number of healthy cells derived from stem cells, this number may be too low for therapeutic purposes.

This limitation prompted Dr Torbett and his colleagues to test whether rapamycin could improve delivery of a gene to HSCs. Rapamycin was selected based on its ability to control virus entry and slow cell growth.

The researchers began by isolating stem cells from cord blood samples. They exposed the HSCs to rapamycin and HIV vectors engineered to deliver a gene for a green florescent protein. This fluorescence provided a visual marker that helped the team track gene delivery.

They saw a big difference in both mouse and human stem cells treated with rapamycin, where therapeutic genes were inserted into up to 80% of cells. This property had never been connected to rapamycin before.

The researchers also found that rapamycin can keep HSCs from differentiating as quickly when taken out of the body for gene therapy.

“We wanted to make sure the conditions we will use preserve stem cells, so if we transplant them back into our animal models, they act just like the original stem cells,” Dr Torbett said. “We showed that, in 2 sets of animal models, stem cells remain and produce gene-modified cells.”

The scientists hope these methods could someday be useful in the clinic.

“Our methods could reduce costs and the amount of preparation that goes into modifying blood stem cells using viral vector gene therapy,” said Cathy Wang, also of The Scripps Research Institute. “It would make gene therapy accessible to a lot more patients.”

She said the team’s next steps are to carry out preclinical studies using rapamycin with stem cells in other animal models and then test the method in humans. The researchers are also working to delineate the dual pathways of rapamycin’s mechanism of action in HSCs. ![]()

Credit: Chad McNeeley

Scientists say they’ve overcome a major hurdle to developing gene therapies for blood disorders.

They found the drug rapamycin could help them bypass the natural defenses of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and deliver therapeutic doses of disease-fighting genes, without compromising HSC function.

The team believes this discovery could lead to more effective and affordable long-term treatments for disorders such as leukemia and sickle cell anemia.

Bruce Torbett, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues reported their findings in Blood.

Past research showed that HIV vectors can deliver genes to HSCs. However, when scientists extract HSCs from the body for gene therapy, HIV vectors are usually able to deliver genes to about 30% to 40% of the cells.

For leukemia, leukodystrophy, or genetic diseases where treatment requires a reasonable number of healthy cells derived from stem cells, this number may be too low for therapeutic purposes.

This limitation prompted Dr Torbett and his colleagues to test whether rapamycin could improve delivery of a gene to HSCs. Rapamycin was selected based on its ability to control virus entry and slow cell growth.

The researchers began by isolating stem cells from cord blood samples. They exposed the HSCs to rapamycin and HIV vectors engineered to deliver a gene for a green florescent protein. This fluorescence provided a visual marker that helped the team track gene delivery.

They saw a big difference in both mouse and human stem cells treated with rapamycin, where therapeutic genes were inserted into up to 80% of cells. This property had never been connected to rapamycin before.

The researchers also found that rapamycin can keep HSCs from differentiating as quickly when taken out of the body for gene therapy.

“We wanted to make sure the conditions we will use preserve stem cells, so if we transplant them back into our animal models, they act just like the original stem cells,” Dr Torbett said. “We showed that, in 2 sets of animal models, stem cells remain and produce gene-modified cells.”

The scientists hope these methods could someday be useful in the clinic.

“Our methods could reduce costs and the amount of preparation that goes into modifying blood stem cells using viral vector gene therapy,” said Cathy Wang, also of The Scripps Research Institute. “It would make gene therapy accessible to a lot more patients.”

She said the team’s next steps are to carry out preclinical studies using rapamycin with stem cells in other animal models and then test the method in humans. The researchers are also working to delineate the dual pathways of rapamycin’s mechanism of action in HSCs. ![]()

Credit: Chad McNeeley

Scientists say they’ve overcome a major hurdle to developing gene therapies for blood disorders.

They found the drug rapamycin could help them bypass the natural defenses of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and deliver therapeutic doses of disease-fighting genes, without compromising HSC function.

The team believes this discovery could lead to more effective and affordable long-term treatments for disorders such as leukemia and sickle cell anemia.

Bruce Torbett, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues reported their findings in Blood.

Past research showed that HIV vectors can deliver genes to HSCs. However, when scientists extract HSCs from the body for gene therapy, HIV vectors are usually able to deliver genes to about 30% to 40% of the cells.

For leukemia, leukodystrophy, or genetic diseases where treatment requires a reasonable number of healthy cells derived from stem cells, this number may be too low for therapeutic purposes.

This limitation prompted Dr Torbett and his colleagues to test whether rapamycin could improve delivery of a gene to HSCs. Rapamycin was selected based on its ability to control virus entry and slow cell growth.

The researchers began by isolating stem cells from cord blood samples. They exposed the HSCs to rapamycin and HIV vectors engineered to deliver a gene for a green florescent protein. This fluorescence provided a visual marker that helped the team track gene delivery.

They saw a big difference in both mouse and human stem cells treated with rapamycin, where therapeutic genes were inserted into up to 80% of cells. This property had never been connected to rapamycin before.

The researchers also found that rapamycin can keep HSCs from differentiating as quickly when taken out of the body for gene therapy.

“We wanted to make sure the conditions we will use preserve stem cells, so if we transplant them back into our animal models, they act just like the original stem cells,” Dr Torbett said. “We showed that, in 2 sets of animal models, stem cells remain and produce gene-modified cells.”

The scientists hope these methods could someday be useful in the clinic.

“Our methods could reduce costs and the amount of preparation that goes into modifying blood stem cells using viral vector gene therapy,” said Cathy Wang, also of The Scripps Research Institute. “It would make gene therapy accessible to a lot more patients.”

She said the team’s next steps are to carry out preclinical studies using rapamycin with stem cells in other animal models and then test the method in humans. The researchers are also working to delineate the dual pathways of rapamycin’s mechanism of action in HSCs. ![]()

Ofatumumab falls short in CLL, DLBCL

Credit: Linda Bartlett

The anti-CD20 antibody ofatumumab (Arzerra) has failed to meet the primary endpoint in two phase 3 trials, according to the companies developing the drug.

Ofatumumab failed to improve progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to physicians’ choice in patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Likewise, ofatumumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve PFS when compared to rituximab plus chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Genmab recently announced these headline results but said the full analyses of safety and efficacy data are underway and will be completed in the coming months.

However, based on these early results, the companies said they are unlikely to pursue regulatory filings for ofatumumab in either indication.

CLL trial

In the OMB114242 study, researchers enrolled 122 patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory CLL. Patients were randomized to receive ofatumumab or physicians’ choice (2:1).

Patients randomized to ofatumumab received an initial dose of 300 mg, followed 1 week later by 2000 mg once weekly for 7 weeks, followed 4 weeks later by 1 infusion of 2000 mg every 4 weeks, for a total treatment duration of 6 to 12 months. Patients in the physicians’ choice arm received a treatment regimen chosen by a physician for up to 6 months.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary objectives were to evaluate response, overall survival, safety, tolerability, and health-related quality of life.

The median PFS, as assessed by an independent review committee, was 5.36 months for ofatumumab and 3.61 months for physicians’ choice (hazard ratio 0.79, P=0.267).

“It was our priority to share this result with the scientific community as soon it became available,” said Rafael Amado, MD, Head of Oncology R&D at GSK. “We will now work to further analyze the data and to better understand the totality of the efficacy and safety findings.”

This study was conducted to meet the requirements from the European Commission for the conditional approval of ofatumumab for the treatment of CLL in patients who are refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab. The current indications in the European Union and the United States do not include bulky, fludarabine-refractory CLL patients.

“Although ofatumumab performed broadly in line with previous data, today’s result is disappointing,” said Jan van de Winkel, PhD, Chief Executive Officer of Genmab. “Based on this result, we do not anticipate applying for a label expansion for ofatumumab in this specific refractory CLL population.”

DLBCL trial

The ORCHARRD study included 447 patients who were refractory to, or had relapsed following, first-line treatment with rituximab in combination with a chemotherapy regimen containing anthracycline or anthracenedione. Patients were also eligible for autologous stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 3 cycles of either ofatumumab or rituximab in combination with DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin) salvage chemotherapy. After the third treatment cycle, patients who obtained a complete or partial response received high-dose chemotherapy followed by transplant.

The primary endpoint was PFS. But GSK and Genmab reported no statistically significant difference in PFS between the treatment arms.

There were no differences in adverse events (AEs) leading to treatment discontinuation, grade 3 or higher AEs, or severe AEs between the treatment arms. However, there were more dose interruptions and delays due to infusion reactions and increased serum creatinine in the ofatumumab-plus-chemotherapy arm, which require further analysis.

“We plan to submit detailed data from the ofatumumab ORCHARRD study in DLBCL for presentation at a medical conference later this year, which we hope will provide further clarity on today’s headline results,” Dr van de Winkel said. “Based on [these early] results, we are unlikely to move forward with a regulatory filing.” ![]()

Credit: Linda Bartlett

The anti-CD20 antibody ofatumumab (Arzerra) has failed to meet the primary endpoint in two phase 3 trials, according to the companies developing the drug.

Ofatumumab failed to improve progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to physicians’ choice in patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Likewise, ofatumumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve PFS when compared to rituximab plus chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Genmab recently announced these headline results but said the full analyses of safety and efficacy data are underway and will be completed in the coming months.

However, based on these early results, the companies said they are unlikely to pursue regulatory filings for ofatumumab in either indication.

CLL trial

In the OMB114242 study, researchers enrolled 122 patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory CLL. Patients were randomized to receive ofatumumab or physicians’ choice (2:1).

Patients randomized to ofatumumab received an initial dose of 300 mg, followed 1 week later by 2000 mg once weekly for 7 weeks, followed 4 weeks later by 1 infusion of 2000 mg every 4 weeks, for a total treatment duration of 6 to 12 months. Patients in the physicians’ choice arm received a treatment regimen chosen by a physician for up to 6 months.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary objectives were to evaluate response, overall survival, safety, tolerability, and health-related quality of life.

The median PFS, as assessed by an independent review committee, was 5.36 months for ofatumumab and 3.61 months for physicians’ choice (hazard ratio 0.79, P=0.267).

“It was our priority to share this result with the scientific community as soon it became available,” said Rafael Amado, MD, Head of Oncology R&D at GSK. “We will now work to further analyze the data and to better understand the totality of the efficacy and safety findings.”

This study was conducted to meet the requirements from the European Commission for the conditional approval of ofatumumab for the treatment of CLL in patients who are refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab. The current indications in the European Union and the United States do not include bulky, fludarabine-refractory CLL patients.

“Although ofatumumab performed broadly in line with previous data, today’s result is disappointing,” said Jan van de Winkel, PhD, Chief Executive Officer of Genmab. “Based on this result, we do not anticipate applying for a label expansion for ofatumumab in this specific refractory CLL population.”

DLBCL trial

The ORCHARRD study included 447 patients who were refractory to, or had relapsed following, first-line treatment with rituximab in combination with a chemotherapy regimen containing anthracycline or anthracenedione. Patients were also eligible for autologous stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 3 cycles of either ofatumumab or rituximab in combination with DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin) salvage chemotherapy. After the third treatment cycle, patients who obtained a complete or partial response received high-dose chemotherapy followed by transplant.

The primary endpoint was PFS. But GSK and Genmab reported no statistically significant difference in PFS between the treatment arms.

There were no differences in adverse events (AEs) leading to treatment discontinuation, grade 3 or higher AEs, or severe AEs between the treatment arms. However, there were more dose interruptions and delays due to infusion reactions and increased serum creatinine in the ofatumumab-plus-chemotherapy arm, which require further analysis.

“We plan to submit detailed data from the ofatumumab ORCHARRD study in DLBCL for presentation at a medical conference later this year, which we hope will provide further clarity on today’s headline results,” Dr van de Winkel said. “Based on [these early] results, we are unlikely to move forward with a regulatory filing.” ![]()

Credit: Linda Bartlett

The anti-CD20 antibody ofatumumab (Arzerra) has failed to meet the primary endpoint in two phase 3 trials, according to the companies developing the drug.

Ofatumumab failed to improve progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to physicians’ choice in patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Likewise, ofatumumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve PFS when compared to rituximab plus chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Genmab recently announced these headline results but said the full analyses of safety and efficacy data are underway and will be completed in the coming months.

However, based on these early results, the companies said they are unlikely to pursue regulatory filings for ofatumumab in either indication.

CLL trial

In the OMB114242 study, researchers enrolled 122 patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory CLL. Patients were randomized to receive ofatumumab or physicians’ choice (2:1).

Patients randomized to ofatumumab received an initial dose of 300 mg, followed 1 week later by 2000 mg once weekly for 7 weeks, followed 4 weeks later by 1 infusion of 2000 mg every 4 weeks, for a total treatment duration of 6 to 12 months. Patients in the physicians’ choice arm received a treatment regimen chosen by a physician for up to 6 months.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary objectives were to evaluate response, overall survival, safety, tolerability, and health-related quality of life.

The median PFS, as assessed by an independent review committee, was 5.36 months for ofatumumab and 3.61 months for physicians’ choice (hazard ratio 0.79, P=0.267).

“It was our priority to share this result with the scientific community as soon it became available,” said Rafael Amado, MD, Head of Oncology R&D at GSK. “We will now work to further analyze the data and to better understand the totality of the efficacy and safety findings.”

This study was conducted to meet the requirements from the European Commission for the conditional approval of ofatumumab for the treatment of CLL in patients who are refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab. The current indications in the European Union and the United States do not include bulky, fludarabine-refractory CLL patients.

“Although ofatumumab performed broadly in line with previous data, today’s result is disappointing,” said Jan van de Winkel, PhD, Chief Executive Officer of Genmab. “Based on this result, we do not anticipate applying for a label expansion for ofatumumab in this specific refractory CLL population.”

DLBCL trial

The ORCHARRD study included 447 patients who were refractory to, or had relapsed following, first-line treatment with rituximab in combination with a chemotherapy regimen containing anthracycline or anthracenedione. Patients were also eligible for autologous stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 3 cycles of either ofatumumab or rituximab in combination with DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin) salvage chemotherapy. After the third treatment cycle, patients who obtained a complete or partial response received high-dose chemotherapy followed by transplant.

The primary endpoint was PFS. But GSK and Genmab reported no statistically significant difference in PFS between the treatment arms.

There were no differences in adverse events (AEs) leading to treatment discontinuation, grade 3 or higher AEs, or severe AEs between the treatment arms. However, there were more dose interruptions and delays due to infusion reactions and increased serum creatinine in the ofatumumab-plus-chemotherapy arm, which require further analysis.

“We plan to submit detailed data from the ofatumumab ORCHARRD study in DLBCL for presentation at a medical conference later this year, which we hope will provide further clarity on today’s headline results,” Dr van de Winkel said. “Based on [these early] results, we are unlikely to move forward with a regulatory filing.” ![]()

Group finds master regulator of MYC

Credit: Juha Klefstrom

New research indicates that an unexpected partnership between the MYC oncogene and a non-coding RNA called PVT1 could be the key to understanding how MYC fuels cancers.

The researchers knew that MYC amplifications cause cancer, but MYC does not amplify alone. It often pairs with adjacent chromosomal regions.

“We wanted to know if the neighboring genes played a role,” said study author Anindya Bagchi, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“We took a chance and were surprised to find this unexpected and counter-intuitive partnership between MYC and its neighbor, PVT1. Not only do these genes amplify together, PVT1 helps boost the MYC protein’s ability to carry out its dangerous activities in the cell.”

The researchers reported this finding in Nature.

Dr Bagchi and his team focused on a region of the genome, 8q24, which contains the MYC gene and is commonly expressed in cancer. The team separated MYC from the neighboring region containing the non-coding RNA PVT1.

Using chromosome engineering, the researchers developed mouse strains in 3 separate iterations: MYC only, the rest of the region containing PVT1 but without MYC, and the pairing of MYC with the regional genes.

The expected outcome, if MYC was the sole driver of the cancer, was tumor growth on the MYC line as well as the paired line. However, the researchers found growth only on the paired line. This suggests MYC is not acting alone and needs help from adjacent genes.

“The discovery of this partnership gives us a stronger understanding of how MYC amplification is fueled,” said David Largaespada, PhD, also of the University of Minnesota.

“When cancer promotes a cell to make more MYC, it also increases the PVT1 in the cell, which, in turn, boosts the amount of MYC. It’s a cycle, and now we’ve identified it, we can look for ways to uncouple this dangerous partnership.”

Testing this theory of uncoupling, the researchers looked closely at several breast and colorectal cancers that are driven by MYC. For example, in colorectal cancer lab models, where a mutation in the beta-catenin gene drives MYC to cancerous levels, eliminating PVT1 from these cells made the tumors nearly disappear.

“Finding the cooperation between MYC and PVT1 could be a game changer,” said Yuen-Yi Tseng, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota.

“We used to think MYC amplification is the major issue but ignored that other co-amplified genes, such as PVT1, can be significant. In this study, we show that PVT1 can be a key regulator of MYC protein, which can shift the paradigm in our understanding of MYC-amplified cancers.”

MYC has been notoriously elusive as a drug target. By uncoupling MYC and PVT1, the researchers suspect they could disable the cancer growth and limit MYC to precancerous levels. This would make PVT1 an ideal drug target to potentially control a major cancer gene.

“This is a thrilling discovery, but there are more questions that follow,” Dr Bagchi said. “Two major areas present themselves now for research. Will breaking the nexus between MYC and PVT1 perform the same in any MYC-driven cancer, even those not driven by this specific genetic location?”

“And how is PVT1 stabilizing or boosting MYC within the cells? This relationship will be a key to developing any drugs to target this mechanism.” ![]()

Credit: Juha Klefstrom

New research indicates that an unexpected partnership between the MYC oncogene and a non-coding RNA called PVT1 could be the key to understanding how MYC fuels cancers.

The researchers knew that MYC amplifications cause cancer, but MYC does not amplify alone. It often pairs with adjacent chromosomal regions.

“We wanted to know if the neighboring genes played a role,” said study author Anindya Bagchi, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“We took a chance and were surprised to find this unexpected and counter-intuitive partnership between MYC and its neighbor, PVT1. Not only do these genes amplify together, PVT1 helps boost the MYC protein’s ability to carry out its dangerous activities in the cell.”

The researchers reported this finding in Nature.

Dr Bagchi and his team focused on a region of the genome, 8q24, which contains the MYC gene and is commonly expressed in cancer. The team separated MYC from the neighboring region containing the non-coding RNA PVT1.

Using chromosome engineering, the researchers developed mouse strains in 3 separate iterations: MYC only, the rest of the region containing PVT1 but without MYC, and the pairing of MYC with the regional genes.

The expected outcome, if MYC was the sole driver of the cancer, was tumor growth on the MYC line as well as the paired line. However, the researchers found growth only on the paired line. This suggests MYC is not acting alone and needs help from adjacent genes.

“The discovery of this partnership gives us a stronger understanding of how MYC amplification is fueled,” said David Largaespada, PhD, also of the University of Minnesota.

“When cancer promotes a cell to make more MYC, it also increases the PVT1 in the cell, which, in turn, boosts the amount of MYC. It’s a cycle, and now we’ve identified it, we can look for ways to uncouple this dangerous partnership.”

Testing this theory of uncoupling, the researchers looked closely at several breast and colorectal cancers that are driven by MYC. For example, in colorectal cancer lab models, where a mutation in the beta-catenin gene drives MYC to cancerous levels, eliminating PVT1 from these cells made the tumors nearly disappear.

“Finding the cooperation between MYC and PVT1 could be a game changer,” said Yuen-Yi Tseng, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota.

“We used to think MYC amplification is the major issue but ignored that other co-amplified genes, such as PVT1, can be significant. In this study, we show that PVT1 can be a key regulator of MYC protein, which can shift the paradigm in our understanding of MYC-amplified cancers.”

MYC has been notoriously elusive as a drug target. By uncoupling MYC and PVT1, the researchers suspect they could disable the cancer growth and limit MYC to precancerous levels. This would make PVT1 an ideal drug target to potentially control a major cancer gene.

“This is a thrilling discovery, but there are more questions that follow,” Dr Bagchi said. “Two major areas present themselves now for research. Will breaking the nexus between MYC and PVT1 perform the same in any MYC-driven cancer, even those not driven by this specific genetic location?”

“And how is PVT1 stabilizing or boosting MYC within the cells? This relationship will be a key to developing any drugs to target this mechanism.” ![]()

Credit: Juha Klefstrom

New research indicates that an unexpected partnership between the MYC oncogene and a non-coding RNA called PVT1 could be the key to understanding how MYC fuels cancers.

The researchers knew that MYC amplifications cause cancer, but MYC does not amplify alone. It often pairs with adjacent chromosomal regions.

“We wanted to know if the neighboring genes played a role,” said study author Anindya Bagchi, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“We took a chance and were surprised to find this unexpected and counter-intuitive partnership between MYC and its neighbor, PVT1. Not only do these genes amplify together, PVT1 helps boost the MYC protein’s ability to carry out its dangerous activities in the cell.”

The researchers reported this finding in Nature.

Dr Bagchi and his team focused on a region of the genome, 8q24, which contains the MYC gene and is commonly expressed in cancer. The team separated MYC from the neighboring region containing the non-coding RNA PVT1.

Using chromosome engineering, the researchers developed mouse strains in 3 separate iterations: MYC only, the rest of the region containing PVT1 but without MYC, and the pairing of MYC with the regional genes.

The expected outcome, if MYC was the sole driver of the cancer, was tumor growth on the MYC line as well as the paired line. However, the researchers found growth only on the paired line. This suggests MYC is not acting alone and needs help from adjacent genes.

“The discovery of this partnership gives us a stronger understanding of how MYC amplification is fueled,” said David Largaespada, PhD, also of the University of Minnesota.

“When cancer promotes a cell to make more MYC, it also increases the PVT1 in the cell, which, in turn, boosts the amount of MYC. It’s a cycle, and now we’ve identified it, we can look for ways to uncouple this dangerous partnership.”

Testing this theory of uncoupling, the researchers looked closely at several breast and colorectal cancers that are driven by MYC. For example, in colorectal cancer lab models, where a mutation in the beta-catenin gene drives MYC to cancerous levels, eliminating PVT1 from these cells made the tumors nearly disappear.

“Finding the cooperation between MYC and PVT1 could be a game changer,” said Yuen-Yi Tseng, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota.

“We used to think MYC amplification is the major issue but ignored that other co-amplified genes, such as PVT1, can be significant. In this study, we show that PVT1 can be a key regulator of MYC protein, which can shift the paradigm in our understanding of MYC-amplified cancers.”

MYC has been notoriously elusive as a drug target. By uncoupling MYC and PVT1, the researchers suspect they could disable the cancer growth and limit MYC to precancerous levels. This would make PVT1 an ideal drug target to potentially control a major cancer gene.

“This is a thrilling discovery, but there are more questions that follow,” Dr Bagchi said. “Two major areas present themselves now for research. Will breaking the nexus between MYC and PVT1 perform the same in any MYC-driven cancer, even those not driven by this specific genetic location?”

“And how is PVT1 stabilizing or boosting MYC within the cells? This relationship will be a key to developing any drugs to target this mechanism.” ![]()

PVAG-14 trims chemotherapy toxicity in unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma