User login

Long-term depression may hasten brain aging in midlife

Previous research suggests a possible link between depression and increased risk of dementia in older adults, but the association between depression and brain health in early adulthood and midlife has not been well studied, wrote Christina S. Dintica, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 649 individuals aged 23-36 at baseline who were part of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. All participants underwent brain MRI and cognitive testing. Depressive symptoms were assessed six times over a 25-year period using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES–D), and the scores were analyzed as time-weighted averages (TWA). Elevated depressive symptoms were defined as CES-D scores of 16 or higher. Brain age was assessed via high-dimensional neuroimaging. Approximately half of the participants were female, and half were Black.

Overall, each 5-point increment in TWA depression symptoms over 25 years was associated with a 1-year increase in brain age, and individuals with elevated TWA depression averaged a 3-year increase in brain age compared with those with lower levels of depression after controlling for factors including chronological age, sex, education, race, MRI scanning site, and intracranial volume, they said. The association was attenuated in a model controlling for antidepressant use, and further attenuated after adjusting for smoking, alcohol consumption, income, body mass index, diabetes, and physical exercise.

The researchers also investigated the impact of the age period of elevated depressive symptoms on brain age. Compared with low depressive symptoms, elevated TWA CES-D at ages 30-39 years, 40-49 years, and 50-59 years was associated with increased brain ages of 2.43, 3.19, and 1.82.

In addition, elevated depressive symptoms were associated with a threefold increase in the odds of poor cognitive function at midlife (odds ratio, 3.30), although these odds were reduced after adjusting for use of antidepressants (OR, 1.47).

The mechanisms of action for the link between depression and accelerated brain aging remains uncertain, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Studies over the last 20 years have demonstrated that increased inflammation and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are two of the most consistent biological findings in major depression, which have been linked to premature aging,” they noted. “Alternative explanations for the link between depression and adverse brain health could be underlying factors that explain both outcomes rather independently, such as low socioeconomic status, childhood maltreatment, or shared genetic effects,” they added.

Adjustment for antidepressant use had little effect overall on the association between depressive symptom severity and brain age, they said.

The current study findings were limited by the single assessment of brain age, which prevented evaluation of the temporality of the association between brain aging and depression, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large and diverse cohort, long-term follow-up, and use of high-dimensional neuroimaging, they said. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore mechanisms of action and the potential benefits of antidepressants, they added.

In the meantime, monitoring and treating depressive symptoms in young adults may help promote brain health in midlife and older age, they concluded.

The CARDIA study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Previous research suggests a possible link between depression and increased risk of dementia in older adults, but the association between depression and brain health in early adulthood and midlife has not been well studied, wrote Christina S. Dintica, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 649 individuals aged 23-36 at baseline who were part of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. All participants underwent brain MRI and cognitive testing. Depressive symptoms were assessed six times over a 25-year period using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES–D), and the scores were analyzed as time-weighted averages (TWA). Elevated depressive symptoms were defined as CES-D scores of 16 or higher. Brain age was assessed via high-dimensional neuroimaging. Approximately half of the participants were female, and half were Black.

Overall, each 5-point increment in TWA depression symptoms over 25 years was associated with a 1-year increase in brain age, and individuals with elevated TWA depression averaged a 3-year increase in brain age compared with those with lower levels of depression after controlling for factors including chronological age, sex, education, race, MRI scanning site, and intracranial volume, they said. The association was attenuated in a model controlling for antidepressant use, and further attenuated after adjusting for smoking, alcohol consumption, income, body mass index, diabetes, and physical exercise.

The researchers also investigated the impact of the age period of elevated depressive symptoms on brain age. Compared with low depressive symptoms, elevated TWA CES-D at ages 30-39 years, 40-49 years, and 50-59 years was associated with increased brain ages of 2.43, 3.19, and 1.82.

In addition, elevated depressive symptoms were associated with a threefold increase in the odds of poor cognitive function at midlife (odds ratio, 3.30), although these odds were reduced after adjusting for use of antidepressants (OR, 1.47).

The mechanisms of action for the link between depression and accelerated brain aging remains uncertain, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Studies over the last 20 years have demonstrated that increased inflammation and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are two of the most consistent biological findings in major depression, which have been linked to premature aging,” they noted. “Alternative explanations for the link between depression and adverse brain health could be underlying factors that explain both outcomes rather independently, such as low socioeconomic status, childhood maltreatment, or shared genetic effects,” they added.

Adjustment for antidepressant use had little effect overall on the association between depressive symptom severity and brain age, they said.

The current study findings were limited by the single assessment of brain age, which prevented evaluation of the temporality of the association between brain aging and depression, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large and diverse cohort, long-term follow-up, and use of high-dimensional neuroimaging, they said. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore mechanisms of action and the potential benefits of antidepressants, they added.

In the meantime, monitoring and treating depressive symptoms in young adults may help promote brain health in midlife and older age, they concluded.

The CARDIA study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Previous research suggests a possible link between depression and increased risk of dementia in older adults, but the association between depression and brain health in early adulthood and midlife has not been well studied, wrote Christina S. Dintica, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers identified 649 individuals aged 23-36 at baseline who were part of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. All participants underwent brain MRI and cognitive testing. Depressive symptoms were assessed six times over a 25-year period using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES–D), and the scores were analyzed as time-weighted averages (TWA). Elevated depressive symptoms were defined as CES-D scores of 16 or higher. Brain age was assessed via high-dimensional neuroimaging. Approximately half of the participants were female, and half were Black.

Overall, each 5-point increment in TWA depression symptoms over 25 years was associated with a 1-year increase in brain age, and individuals with elevated TWA depression averaged a 3-year increase in brain age compared with those with lower levels of depression after controlling for factors including chronological age, sex, education, race, MRI scanning site, and intracranial volume, they said. The association was attenuated in a model controlling for antidepressant use, and further attenuated after adjusting for smoking, alcohol consumption, income, body mass index, diabetes, and physical exercise.

The researchers also investigated the impact of the age period of elevated depressive symptoms on brain age. Compared with low depressive symptoms, elevated TWA CES-D at ages 30-39 years, 40-49 years, and 50-59 years was associated with increased brain ages of 2.43, 3.19, and 1.82.

In addition, elevated depressive symptoms were associated with a threefold increase in the odds of poor cognitive function at midlife (odds ratio, 3.30), although these odds were reduced after adjusting for use of antidepressants (OR, 1.47).

The mechanisms of action for the link between depression and accelerated brain aging remains uncertain, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Studies over the last 20 years have demonstrated that increased inflammation and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are two of the most consistent biological findings in major depression, which have been linked to premature aging,” they noted. “Alternative explanations for the link between depression and adverse brain health could be underlying factors that explain both outcomes rather independently, such as low socioeconomic status, childhood maltreatment, or shared genetic effects,” they added.

Adjustment for antidepressant use had little effect overall on the association between depressive symptom severity and brain age, they said.

The current study findings were limited by the single assessment of brain age, which prevented evaluation of the temporality of the association between brain aging and depression, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large and diverse cohort, long-term follow-up, and use of high-dimensional neuroimaging, they said. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore mechanisms of action and the potential benefits of antidepressants, they added.

In the meantime, monitoring and treating depressive symptoms in young adults may help promote brain health in midlife and older age, they concluded.

The CARDIA study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Positive top-line results for novel psychedelic in major depression

Top-line results from a phase 2a study of SPL026 (intravenous N,N-Dimethyltryptamine [DMT]) showed a 57% remission rate 3 months after participants received a single dose of the drug, the developer reports.

Small Pharma noted in a press release that this is the first placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a short-duration psychedelic for depression completed to date.

Investigators reported significant improvement in depression symptoms 2 weeks after dosing, which was the primary endpoint, and the improvement persisted at week 12.

“We now have the first evidence that SPL026 DMT, combined with supportive therapy, may be effective for people suffering from MDD,” chief investigator David Erritzoe, MD, PhD, clinical psychiatrist at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

“For patients who are unfortunate to experience little benefit from existing antidepressants, the potential for rapid and durable relief from a single treatment, as shown in this trial, is very promising,” Dr. Erritzoe added.

Randomized trial results

The blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, two-staged phase 2a study included 34 patients with moderate to severe MDD. Those who were taking pharmacological antidepressant medication at baseline stopped taking the medication prior to dosing with SPL026.

Patients received a placebo (n = 17) or active treatment (n = 17). The latter consisted of a short IV infusion of 21.5 mg of SPL026, resulting in a 20- to 30-minute psychedelic experience, and supportive therapy.

The dose was selected based on data analysis from the company’s phase 1 study in healthy volunteers.

Efficacy was assessed using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) to measure changes in MDD symptoms.

Two weeks after dosing, those receiving the novel therapy showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, demonstrating a –7.4-point difference versus the placebo group in MADRS score (P = .02).

Analysis of key secondary endpoints showed a rapid onset of antidepressant effect 1 week post-dose, with a statistically significant difference in MADRS score between the active and placebo groups of –10.8 points (P = .002).

Next steps?

All participants were subsequently enrolled into an open-label phase of the trial where they received a single dose of SPL026 with supportive therapy. They were then followed for a further 12 weeks.

In the open-label phase, patients who received at least one active dose of SPL026 with supportive therapy reported a durable improvement in depression symptoms.

No apparent difference in antidepressant effect was observed between a one- or two-dose regimen of SPL026.

“SPL026 with supportive therapy was shown to have a significant antidepressant effect that was rapid and durable,” Carol Routledge, PhD, chief medical and scientific officer at Small Pharma, said in the statement.

“The results are clinically meaningful and enable us to progress into an international multisite phase 2b study where we seek to further explore the efficacy and safety profile of SPL026 in a larger MDD patient population,” Dr. Routledge added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Top-line results from a phase 2a study of SPL026 (intravenous N,N-Dimethyltryptamine [DMT]) showed a 57% remission rate 3 months after participants received a single dose of the drug, the developer reports.

Small Pharma noted in a press release that this is the first placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a short-duration psychedelic for depression completed to date.

Investigators reported significant improvement in depression symptoms 2 weeks after dosing, which was the primary endpoint, and the improvement persisted at week 12.

“We now have the first evidence that SPL026 DMT, combined with supportive therapy, may be effective for people suffering from MDD,” chief investigator David Erritzoe, MD, PhD, clinical psychiatrist at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

“For patients who are unfortunate to experience little benefit from existing antidepressants, the potential for rapid and durable relief from a single treatment, as shown in this trial, is very promising,” Dr. Erritzoe added.

Randomized trial results

The blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, two-staged phase 2a study included 34 patients with moderate to severe MDD. Those who were taking pharmacological antidepressant medication at baseline stopped taking the medication prior to dosing with SPL026.

Patients received a placebo (n = 17) or active treatment (n = 17). The latter consisted of a short IV infusion of 21.5 mg of SPL026, resulting in a 20- to 30-minute psychedelic experience, and supportive therapy.

The dose was selected based on data analysis from the company’s phase 1 study in healthy volunteers.

Efficacy was assessed using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) to measure changes in MDD symptoms.

Two weeks after dosing, those receiving the novel therapy showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, demonstrating a –7.4-point difference versus the placebo group in MADRS score (P = .02).

Analysis of key secondary endpoints showed a rapid onset of antidepressant effect 1 week post-dose, with a statistically significant difference in MADRS score between the active and placebo groups of –10.8 points (P = .002).

Next steps?

All participants were subsequently enrolled into an open-label phase of the trial where they received a single dose of SPL026 with supportive therapy. They were then followed for a further 12 weeks.

In the open-label phase, patients who received at least one active dose of SPL026 with supportive therapy reported a durable improvement in depression symptoms.

No apparent difference in antidepressant effect was observed between a one- or two-dose regimen of SPL026.

“SPL026 with supportive therapy was shown to have a significant antidepressant effect that was rapid and durable,” Carol Routledge, PhD, chief medical and scientific officer at Small Pharma, said in the statement.

“The results are clinically meaningful and enable us to progress into an international multisite phase 2b study where we seek to further explore the efficacy and safety profile of SPL026 in a larger MDD patient population,” Dr. Routledge added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Top-line results from a phase 2a study of SPL026 (intravenous N,N-Dimethyltryptamine [DMT]) showed a 57% remission rate 3 months after participants received a single dose of the drug, the developer reports.

Small Pharma noted in a press release that this is the first placebo-controlled efficacy trial of a short-duration psychedelic for depression completed to date.

Investigators reported significant improvement in depression symptoms 2 weeks after dosing, which was the primary endpoint, and the improvement persisted at week 12.

“We now have the first evidence that SPL026 DMT, combined with supportive therapy, may be effective for people suffering from MDD,” chief investigator David Erritzoe, MD, PhD, clinical psychiatrist at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

“For patients who are unfortunate to experience little benefit from existing antidepressants, the potential for rapid and durable relief from a single treatment, as shown in this trial, is very promising,” Dr. Erritzoe added.

Randomized trial results

The blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, two-staged phase 2a study included 34 patients with moderate to severe MDD. Those who were taking pharmacological antidepressant medication at baseline stopped taking the medication prior to dosing with SPL026.

Patients received a placebo (n = 17) or active treatment (n = 17). The latter consisted of a short IV infusion of 21.5 mg of SPL026, resulting in a 20- to 30-minute psychedelic experience, and supportive therapy.

The dose was selected based on data analysis from the company’s phase 1 study in healthy volunteers.

Efficacy was assessed using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) to measure changes in MDD symptoms.

Two weeks after dosing, those receiving the novel therapy showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, demonstrating a –7.4-point difference versus the placebo group in MADRS score (P = .02).

Analysis of key secondary endpoints showed a rapid onset of antidepressant effect 1 week post-dose, with a statistically significant difference in MADRS score between the active and placebo groups of –10.8 points (P = .002).

Next steps?

All participants were subsequently enrolled into an open-label phase of the trial where they received a single dose of SPL026 with supportive therapy. They were then followed for a further 12 weeks.

In the open-label phase, patients who received at least one active dose of SPL026 with supportive therapy reported a durable improvement in depression symptoms.

No apparent difference in antidepressant effect was observed between a one- or two-dose regimen of SPL026.

“SPL026 with supportive therapy was shown to have a significant antidepressant effect that was rapid and durable,” Carol Routledge, PhD, chief medical and scientific officer at Small Pharma, said in the statement.

“The results are clinically meaningful and enable us to progress into an international multisite phase 2b study where we seek to further explore the efficacy and safety profile of SPL026 in a larger MDD patient population,” Dr. Routledge added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lipid signature may flag schizophrenia

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.

“Do we need a marker to tell us if someone’s got a major mental illness compared to a healthy person?” asked Dr. Strakowski, who was not part of the study. “The answer to that is no. We already know how to do that.”

A truly useful marker would help clinicians differentiate between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or another serious mental illness, he said.

“That’s the marker that would be most helpful,” he added. “This can’t address that, but perhaps it could be a step to start designing a test for that.”

Dr. Strakowksi noted that the findings do not clarify whether the lipid profile found in patients with schizophrenia predates diagnosis or whether it is a result of the mental illness, an unrelated illness, or another factor that could be critical in treating patients.

However, he was quick to point out the limitations don’t diminish the importance of the study.

“It’s a large dataset that’s cross-national, cross-diagnostic that says there appears to be a signal here that there’s something about lipid profiles that may be independent of treatment that could be worth understanding,” Dr. Strakowksi said.

“It allows us to think about developing different models based on lipid profiles, and that’s important,” he added.

The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National One Thousand Foreign Experts Plan, Moscow Center for Innovative Technologies in Healthcare, European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, German Research Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research, the Dr. Lisa Oehler Foundation, and the Munich Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. Schulze and Dr. Schulte reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.

“Do we need a marker to tell us if someone’s got a major mental illness compared to a healthy person?” asked Dr. Strakowski, who was not part of the study. “The answer to that is no. We already know how to do that.”

A truly useful marker would help clinicians differentiate between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or another serious mental illness, he said.

“That’s the marker that would be most helpful,” he added. “This can’t address that, but perhaps it could be a step to start designing a test for that.”

Dr. Strakowksi noted that the findings do not clarify whether the lipid profile found in patients with schizophrenia predates diagnosis or whether it is a result of the mental illness, an unrelated illness, or another factor that could be critical in treating patients.

However, he was quick to point out the limitations don’t diminish the importance of the study.

“It’s a large dataset that’s cross-national, cross-diagnostic that says there appears to be a signal here that there’s something about lipid profiles that may be independent of treatment that could be worth understanding,” Dr. Strakowksi said.

“It allows us to think about developing different models based on lipid profiles, and that’s important,” he added.

The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National One Thousand Foreign Experts Plan, Moscow Center for Innovative Technologies in Healthcare, European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, German Research Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research, the Dr. Lisa Oehler Foundation, and the Munich Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. Schulze and Dr. Schulte reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.

“Do we need a marker to tell us if someone’s got a major mental illness compared to a healthy person?” asked Dr. Strakowski, who was not part of the study. “The answer to that is no. We already know how to do that.”

A truly useful marker would help clinicians differentiate between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, or another serious mental illness, he said.

“That’s the marker that would be most helpful,” he added. “This can’t address that, but perhaps it could be a step to start designing a test for that.”

Dr. Strakowksi noted that the findings do not clarify whether the lipid profile found in patients with schizophrenia predates diagnosis or whether it is a result of the mental illness, an unrelated illness, or another factor that could be critical in treating patients.

However, he was quick to point out the limitations don’t diminish the importance of the study.

“It’s a large dataset that’s cross-national, cross-diagnostic that says there appears to be a signal here that there’s something about lipid profiles that may be independent of treatment that could be worth understanding,” Dr. Strakowksi said.

“It allows us to think about developing different models based on lipid profiles, and that’s important,” he added.

The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National One Thousand Foreign Experts Plan, Moscow Center for Innovative Technologies in Healthcare, European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, German Research Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research, the Dr. Lisa Oehler Foundation, and the Munich Clinician Scientist Program. Dr. Schulze and Dr. Schulte reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Psychiatric illnesses share common brain network

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

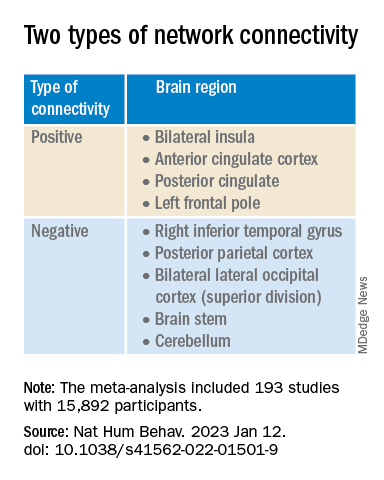

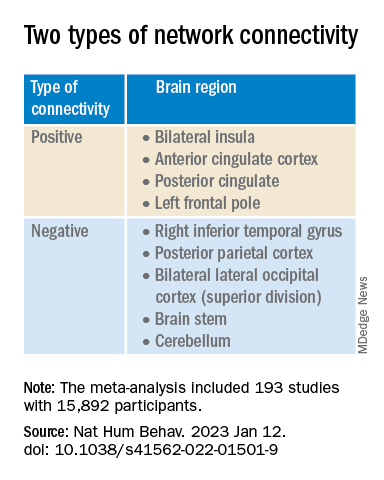

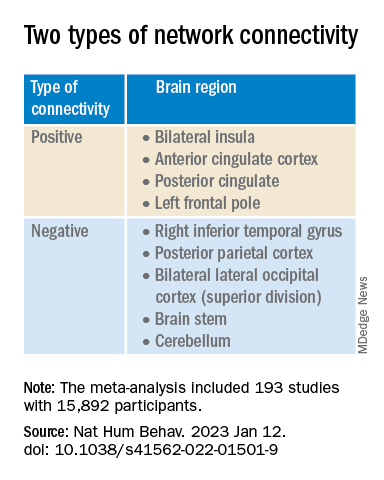

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Concern grows over ‘medical assistance in dying for mental illness’ law

Canada already has the largest number of deaths by MAID of any nation, with 10,064 in 2021, a 32% increase from 2020. With the addition of serious mental illness (SMI) as an eligible category, the country is on track to have the most liberal assisted-death policy in the world.

Concerns about the additional number of patients who could become eligible for MAID, and a lack of evidence-backed standards from disability rights groups, mental health advocates, First Nations leaders, psychiatrists, and other mental health providers, seems to have led the Canadian government to give the proposed law some sober second thought.

“Listening to experts and Canadians, we believe this date needs to be temporarily delayed,” said David Lametti, Canada’s minister of Justice and attorney general of Canada; Jean-Yves Duclos, minister of Health; and Carolyn Bennett, minister of Mental Health and Addictions, in a Dec. 15, 2022, joint statement.

Canada’s Parliament – which approved the expansion – will now have to vote on whether to okay a pause on the legislation.

However, the Canadian Psychiatric Association has not been calling for a delay in the proposed legislation. In a November 2021 statement, the CPA said it “does not take a position on the legality or morality of MAID,” but added that to deny MAID to people with mental illness was discriminatory, and that, as it was the law, it must be followed.

“CPA has not taken a position about MAID,” the association’s president Gary Chaimowitz, MBChB, told this news organization. “We know this is coming and our organization is trying to get its members ready for what will be most likely the ability of people with mental conditions to be able to request MAID,” said Dr. Chaimowitz, who is also head of forensic psychiatry at St. Joseph’s Healthcare and a professor of psychiatry at McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Dr. Chaimowitz acknowledges that “a majority of psychiatrists do not want to be involved in anything to do with MAID.”

“The idea, certainly in psychiatry, is to get people well and we’ve been taught that people dying from a major mental disorder is something that we’re trained to prevent,” he added.

A ‘clinical option’

Assisted medical death is especially fraught in psychiatry, said Rebecca Brendel, MD, president of the American Psychiatric Association. She noted a 25-year life expectancy gap between people with SMI and those who do not have such conditions.

“As a profession we have very serious obligations to advance treatment so that a person with serious mental illness can live [a] full, productive, and healthy [life],” Dr. Brendel, associate director of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School in Boston, said in an interview.

Under the Canadian proposal, psychiatrists would be allowed to suggest MAID as a “clinical option.”

Harold Braswell, PhD, a fellow with The Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute, calls that problematic.

“It’s not neutral to suggest to someone that it would be theoretically reasonable to end their lives,” Dr. Braswell, associate professor at the Albert Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics at Saint Louis University, told this news organization.

It also creates a double standard in the treatment of suicidal ideation, in which suicide prevention is absolute for some, but encouraging it as a possibility for others, he added.

“To have that come from an authority figure is something that’s very harsh and, in my opinion, very potentially destructive,” especially for vulnerable groups, like First Nations people, who already have elevated rates of suicide, said Dr. Braswell.

Fierce debate

Since 2016, Canada has allowed MAID for medical conditions and diseases that will not improve and in cases where the evidence shows that medical providers can accurately predict the condition will not improve.

However, in 2019, a Quebec court ruled that the law unconstitutionally barred euthanasia in people who were not terminally ill. In March 2021, Canada’s criminal code was amended to allow MAID for people whose natural death was not “reasonably foreseeable,” but it excluded SMI for a period of 2 years, ending in March 2023.

The 2-year stay was intended to allow for study and to give mental health providers and MAID assessors time to develop standards.

The federal government charged a 12-member expert panel with determining how to safely allow MAID for SMI. In its final report released in May 2022 it recommended that standards be developed.

The panel acknowledged that for many conditions it may be impossible to make predictions about whether an individual might improve. However, it did not mention SMI.

In those cases, when MAID is requested, “establishing incurability and irreversibility on the basis of the evolution and response to past interventions is necessary,” the panel noted, adding that these are the criteria used by psychiatrists assessing euthanasia requests in the Netherlands and Belgium.

But the notion that mental illness can be irremediable has been fiercely debated.

Soon after the expert report was released, the Center for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto noted on its website that there are currently “no agreed upon standards for psychiatrists or other health care practitioners to use to determine if a person’s mental illness is ‘grievous and irremediable’ for the purposes of MAID.”

Dr. Chaimowitz acknowledged that “there’s no agreed-upon definition of incurability” in mental illness. Some psychiatrists “will argue that there’s always another treatment that can be attempted,” he said, adding that there has been a lack of consensus on irremediability among CPA members.

Protecting vulnerable populations

Matt Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP, director of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said the question of irremediability is crucial. “Most people with mental illness do get better, especially if they’re in treatment,” Dr. Wynia said.

For MAID assessors it may be difficult to know when someone has tried all possible treatments, especially given the wide array of options, including psychedelics, said Dr. Wynia.

Dr. Braswell said there is not enough evidence that mental illness is incurable. With SMI, “there’s a lot more potential for the causes of the individual’s suffering to be ameliorated. By offering MAID, you’re going to kill people who might have been able to get out of this through other nonlethal means.”

Currently, MAID is provided for an irremediable medical condition, “in other words, a condition that will not improve and that we can predict will not improve,” said Karandeep S. Gaind, MD, chief of psychiatry at Toronto’s Humber River Hospital and physician chair of the hospital’s MAID team.

“If that’s the premise, then I think we cannot provide MAID for sole mental illness,” Dr. Gaind said. “Because we can’t honestly make those predictions” with mental illness, he added.

Dr. Gaind does not support MAID for mental illness and believes that it will put the vulnerable – including those living in poverty – at particular risk.

With the proposed expansion, MAID is “now becoming something which is being sought as a way to escape a painful life rather than to avoid a painful death,” said Dr. Gaind, who is also a past president of the CPA.

One member of the federal government’s expert panel – Ellen Cohen, who had a psychiatric condition – wrote in The Globe and Mail that she quit early on when it became apparent that the panel was not seriously considering her own experiences or the possibility that poverty and lack of access to care or social supports could strongly influence a request for MAID.

Social determinants of suffering

People with mental illness often are without homes, have substance use disorders, have been stigmatized and discriminated against, and have poor social supports, said Dr. Wynia. “You worry that it’s all of those things that are making them want to end their lives,” he said.

The Daily Mail ran a story in December 2022 about a 65-year-old Canadian who said he’d applied for MAID solely because of fears that his disability benefits for various chronic health conditions were being cut off and that he didn’t want to live in poverty.

A 51-year-old Ontario woman with multiple chemical sensitivities was granted MAID after she said she could not find housing that could keep her safe, according to an August report by CTV News.

Tarek Rajji, MD, chief of the Adult Neurodevelopment and Geriatric Psychiatry Division at CAMH, said social determinants of health need to be considered in standards created to guide MAID for mental illness.

“We’re very mindful of the fact that the suffering, that is, the grievousness that the person is living with, in the context of mental illness, many times is due to the social determinants of their illness and the social determinants of their suffering,” Dr. Rajji said.

Many are also concerned that it will be difficult to separate out suicidality from sheer hopelessness.

The CPA has advised a group that’s working on developing guidelines for MAID in SMI and is also developing a curriculum for mental health providers, Dr. Chaimowitz said. As part of that, there will be a process to ensure that someone who is actively suicidal is not granted MAID.

“I do not believe that it’s contemplated that MAID is going to accelerate or facilitate suicidal ideation,” he said. Someone who is suicidal will be referred to treatment, said Dr. Chaimowitz.

“People with depression often feel hopeless,” and may refuse treatments that have worked in the past, countered Dr. Gaind. Some of his patients “are absolutely convinced that nothing will help,” he said.

Troublesome cases

The expert panel said in its final report that “it is not possible to provide fixed rules for how many attempts at interventions, how many types of interventions, and over how much time,” are necessary to establish “irreversibility” of mental illness.

Dr. Chaimowitz said MAID will not be offered to anyone “refusing treatment for their condition without any good reason.” They will be “unlikely to meet criteria for incurable,” as they will have needed to avail themselves of the array of treatments available, he said.

That would be similar to rules in Belgium and the Netherlands, which allow euthanasia for psychiatric conditions.