User login

Accelerated Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Veterans Health Administration System

Accelerated Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Veterans Health Administration System

Evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as prolonged exposure (PE), is supported by multiple clinical practice guidelines and is expected to be available to veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1-5 However, traditional models of EBP delivery with 1 or 2 sessions weekly have high dropout rates.6,7 Few veterans who could benefit from such EBPs receive them, and those who do have low completion rates.8,9 Over a 15-year period, VHA records review of > 265,500 veterans with PTSD showed only 9.1% completed EBP treatment that included but was not limited to PE.10

One empirically supported solution that has yet to be widely implemented is delivering EBPs for PTSD in a massed or accelerated format of ≥ 3 sessions weekly.11 While these massed models of EBP delivery for PTSD are promising, their implementation is limited in federal health care settings, such as the VHA.12 PE therapy is a first-line treatment for PTSD that has been evaluated in numerous clinical trials since the early 1990s and in a wide range of trauma populations.13,14 Massed PE is effective and PE has been found to be effective both in-person and via telehealth.11,15,16

Another approach to accelerated PE is the inclusion of a massed PE course within a broader treatment context that includes augmentation of the massed PE with additional services, this is referred to as an intensive outpatient model (IOP).17 PE-IOP has also been shown to be feasible, acceptable, and effective with increased completion rates in comparison to the traditional (1 or 2 sessions weekly) model of PE.12,16,18,19 Ragsdale et al describe a 2-week IOP with multiple treatment tracks, including a PTSD track. The PTSD treatment track includes massed PE and additional standard services including case management, wellness services, family services, and a single session effective behaviors group. Additional augmentation services are available when clinically indicated (eg, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation treatment, psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, and/or relapse prevention).17

Rauch et al studied the first 80 patients completing an IOP program that consisted of PE (5 sessions weekly) and complementary interventions (eg, mindfulness and yoga) and reported a 96% retention rate, significant reductions of self-reported PTSD symptoms, significant reduction in self-reported co-occurring depression symptoms, and significant increase in self-reported satisfaction with social functioning. 18 In another study, Sherril et al explored patient reactions to participation in massed PE (5 sessions weekly) and found that patients reported significantly more positive than negative reactions. Sherrill et al noted that according to patients, the benefits of massed PE included a structured format that limits avoidance and distraction. The resulting fast pace of progress enhanced motivation; however, drawbacks included short-term discomfort and time demands.19 Yamokoski et al explored the feasibility of massed PE in a larger study of PTSD treatment in an intensive outpatient track (IOT) in a VHA PTSD clinic with minimal staffing. The 48 patients who completed IOT PTSD treatment in 2 or 4 weeks (including 35 patients who received massed PE) had high retention rates (85%), reported high satisfaction, and had significantly reduced PTSD and depression symptoms.12

The massed IOT PE model implemented by Yamokoski et al included the primary EBP intervention of massed PE with adjunctive groups. The addition of these groups increased both retention and patient-reported satisfaction. The PE-IOP model implemented by Rauch et al and Sherrill et al also included wellness and educational groups, as well as access to complementary interventions such as mindfulness and yoga.18,19 The addition of wellness education along with a primary EBP aligned with the VHA focus on whole health well-being and wellness. The whole health approach includes understanding the factors that motivate a patient toward health and well-being, provision of health education, and providing access to complementary interventions such as mindfulness.20 Dryden et al describe the whole health transformation within VHA as a proactive approach to addressing employee and patient wellness and health. Their research found that the whole health model promoted well-being in patients and staff and was sustained even during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Dryden et al also noted that use of virtual technologies facilitated and promoted continued whole health implementation. The literature illustrates that: (1) massed PE can be provided with complementary education and wellness offerings, and that such offerings may increase both retention and satisfaction by enriching the massed PE treatment (eg, delivering PE-IOP); (2) whole health including wellness education and complementary interventions (eg, mindfulness, motivational enhancement) promotes well-being in both patients and mental health professionals; and (3) whole health education and complementary interventions can be delivered virtually.

Health Care Need

Prior to the implementation of a massed EBP for PTSD program at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pacific Islands Health Care System (VAPIHCS), our setting included a traditional outpatient program for treatment of PTSD and a 12- bed residential program for treatment of PTSD for male-identified (self-identified and identified as male in the electronic medical record) veterans via a cohort model with an 8- or 9-week length of stay. Both programs were located on Oahu. Thus, veterans who received care at VAPIHCS had access to PE in both outpatient and residential settings and via in-person and telehealth modalities. However, their access to PE was limited to the traditional models of PE delivery (eg, 1 or 2 session per week) and very few veterans outside of the island of Oahu had accessed PE treatment for PTSD. Moreover, when looking at PE reach within VAPIHCS, in the fiscal year prior to the implementation of the massed EBP program, only 32 of the > 5000 eligible veterans with a PTSD diagnosis had received PE. VAPIHCS serves veterans in a catchment area across the Pacific Basin which includes 3 time zones: Hawaii Standard Time (HST), Chamorro Standard Time (ChST), and Samoa Standard Time (SST). ChST is 20 hours ahead of HST, making service delivery that is inclusive for patients in Guam and Saipan especially challenging when providing care from Hawaii or other US states or territories. Given all of this, implementation of a new program offering accelerated PE virtually to any veterans with PTSD within the VAPIHCS would increase access to and reduce barriers to receiving PE.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The Intensive Virtual EBP Team (iVET) for PTSD consists of an accelerated course of PE therapy and whole health education provided via VA Video Connect (VVC). iVET is a 3-week program and includes 3 parts: (1) massed individual PE therapy for PTSD; (2) group whole health and wellness classes; and (3) individual health coaching to address personal wellness goals. Programming is offered over 10-hour days to increase access across multiple time zones, especially to allow for participation in Guam and Saipan.

When a patient is referred to the iVET, their first contact is a video (or telephone) appointment with a registered nurse (RN) for a screening session. The screening session is designed to educate the patient about the program, including interventions, time commitment, and resources required for participation. In addition, following the educational discussion, the RN completes screening for safety with the patient including suicidal ideation and risk, as well as intimate partner violence risk. If urgent safety concerns are present, a licensed social worker or psychologist will join the screening to complete further assessment of risk and to address any safety concerns. Following screening, patients are scheduled for a VVC intake with a licensed therapist (social worker or psychologist) to complete the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition), a clinical interview for PTSD assessment. Patients are also sent a secure link to complete a measurement-based care (MBC) battery of self-report measures including measures assessing demographics, PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, substance use, quality of life (QOL), and satisfaction with mental health care. The results of the CAPS-5 and self-report measures are discussed with the patient during the intake session when planning next steps and engaging in shared decision-making. This initial VVC intake not only allows for diagnostic goodness of fit but also provides the opportunity to troubleshoot any technical difficulties the patients might have with the virtual platforms.

There are minimal exclusion criteria for participation in iVET, which include active unmanaged psychosis or manic symptoms, recent suicidal crises (attempt within 8 weeks), active nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors (within 8 weeks), and moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment. Following intake, patients are scheduled to begin their course of care with iVET. Upon completion of intake, patients are sent program materials for their individual and group classes, asked to obtain or request a recording device, and told they will receive email links for all VVC appointments. Patients are admitted to the iVET in a rolling admission fashion, thereby increasing access when compared to closed group and/or cohort models of care.

Patients receiving care in iVET attend 2 or 3 telehealth appointments daily with practice exercises daily between telehealth sessions. The primary EBP intervention in the iVET for PTSD program is a massed or accelerated course of PE, which includes 4 primary components: psychoeducation, in-vivo exposure, imaginal exposure, and breathing retraining. Specifically, PE is delivered in 4 90-minute individual sessions weekly allowing completion of the full PE protocol, to fidelity, in 3 weeks. In addition to receiving this primary intervention, patients also participate in four 50-minute group sessions per week of a whole health and wellness education class and have access to one 30- to 60-minute session weekly of individual health coaching should they wish to set wellness goals and receive coaching in support of attaining wellness goals. During iVET, patients are invited to complete MBC batteries of selfreport measures including measures assessing PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, substance use, QOL, and satisfaction with mental health care at sessions 1, 5, 9, and the final session of PE. Following discharge from the iVET, patients are offered 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month individual postdischarge check-up sessions with a therapist where they are invited to complete MBC measures and review relapse prevention and maintenance of treatment gains. Likewise, they are offered 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month postdischarge check-up sessions with an RN focused on maintaining wellness gains.

The iVET for PTSD staff includes 3 therapists (psychologists or social workers) and an RN. Additionally, the iVET for PTSD is supported by a program manager and a program support assistant. The primary cost of the program is salary for staff. Additional iVET for PTSD resources included computer equipment for staff and minimal supplies. Due to the virtual environment of care, iVET staff telework and do not require physical space within VAPIHCS.

OUTCOMES

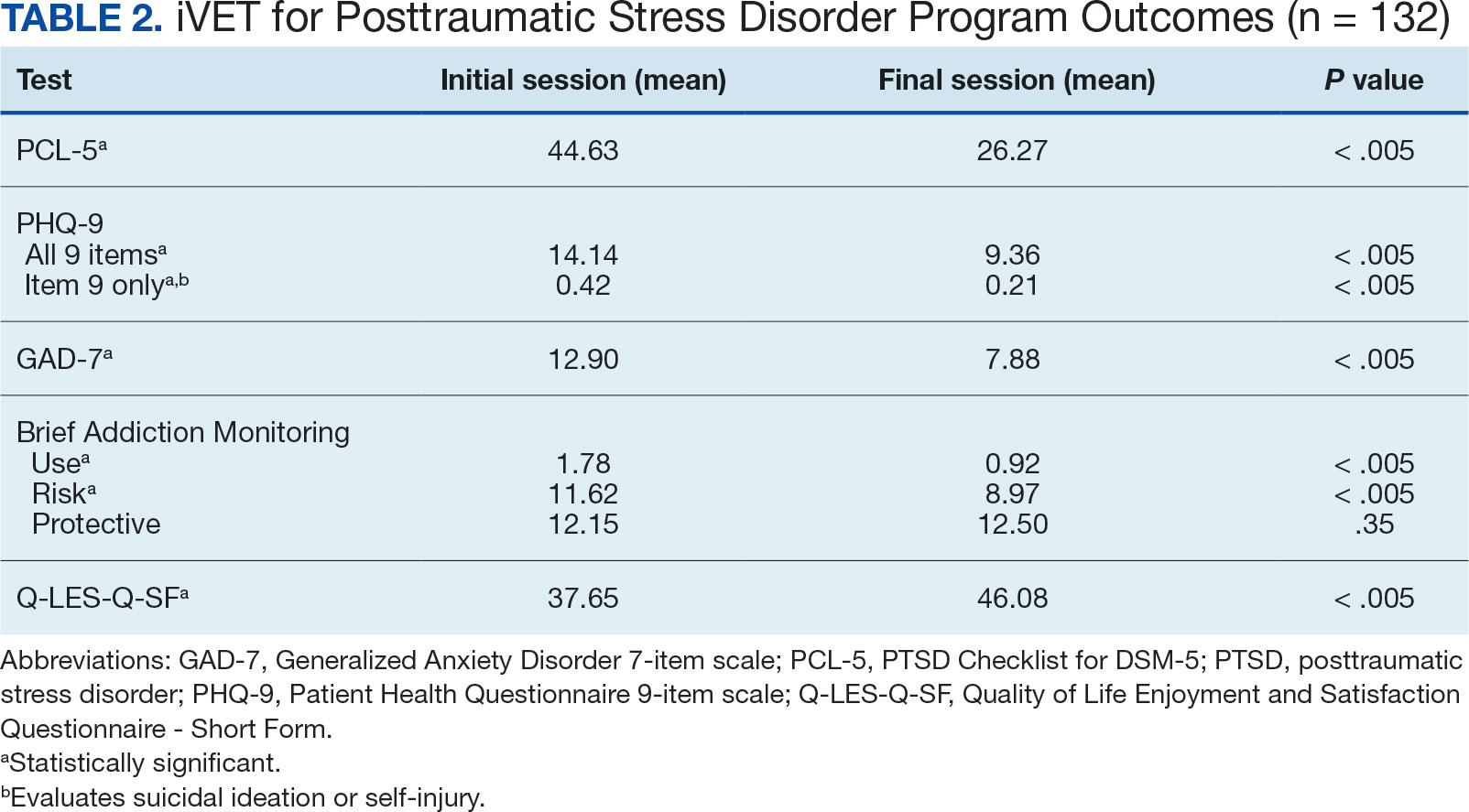

All veterans receiving care in iVET for PTSD are invited to complete a MBC at multiple timepoints including pretreatment, during PE treatment, and posttreatment. The MBC measures included self-reported demographics, a 2-item measure of satisfaction with mental health services, the Brief Addiction Monitor-Intensive Outpatient Program questionnaire,22 the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale,23, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),24 the QOL Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire- Short Form,25 and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), both weekly and monthly versions. 26,27

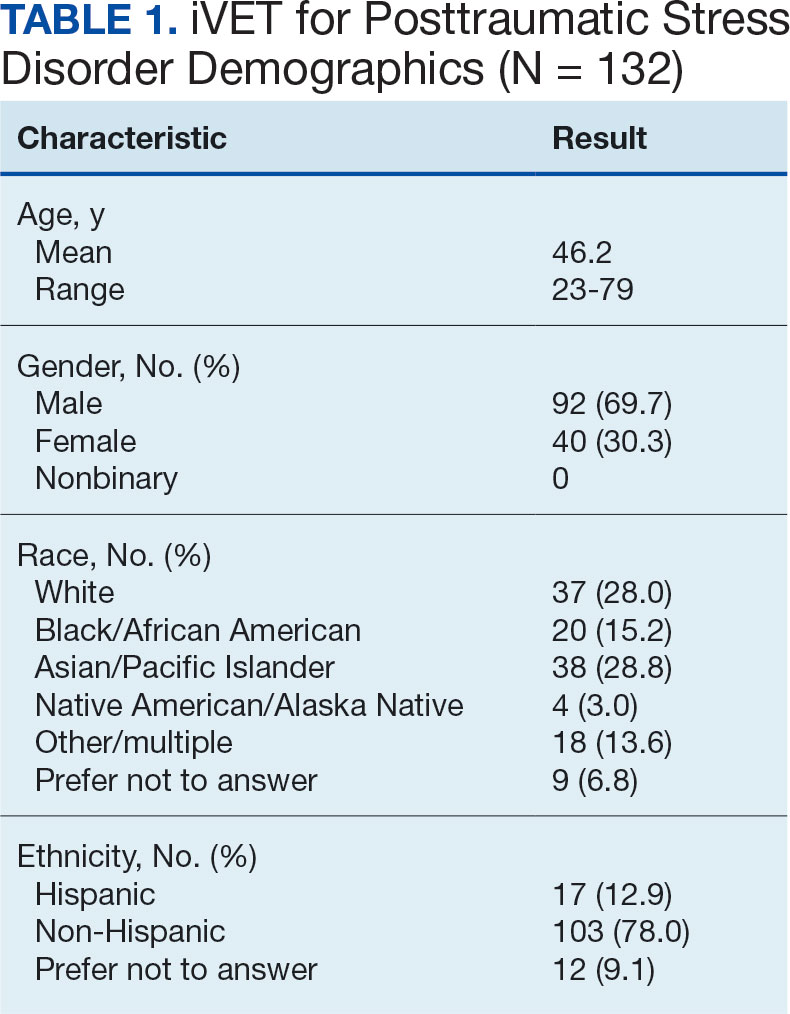

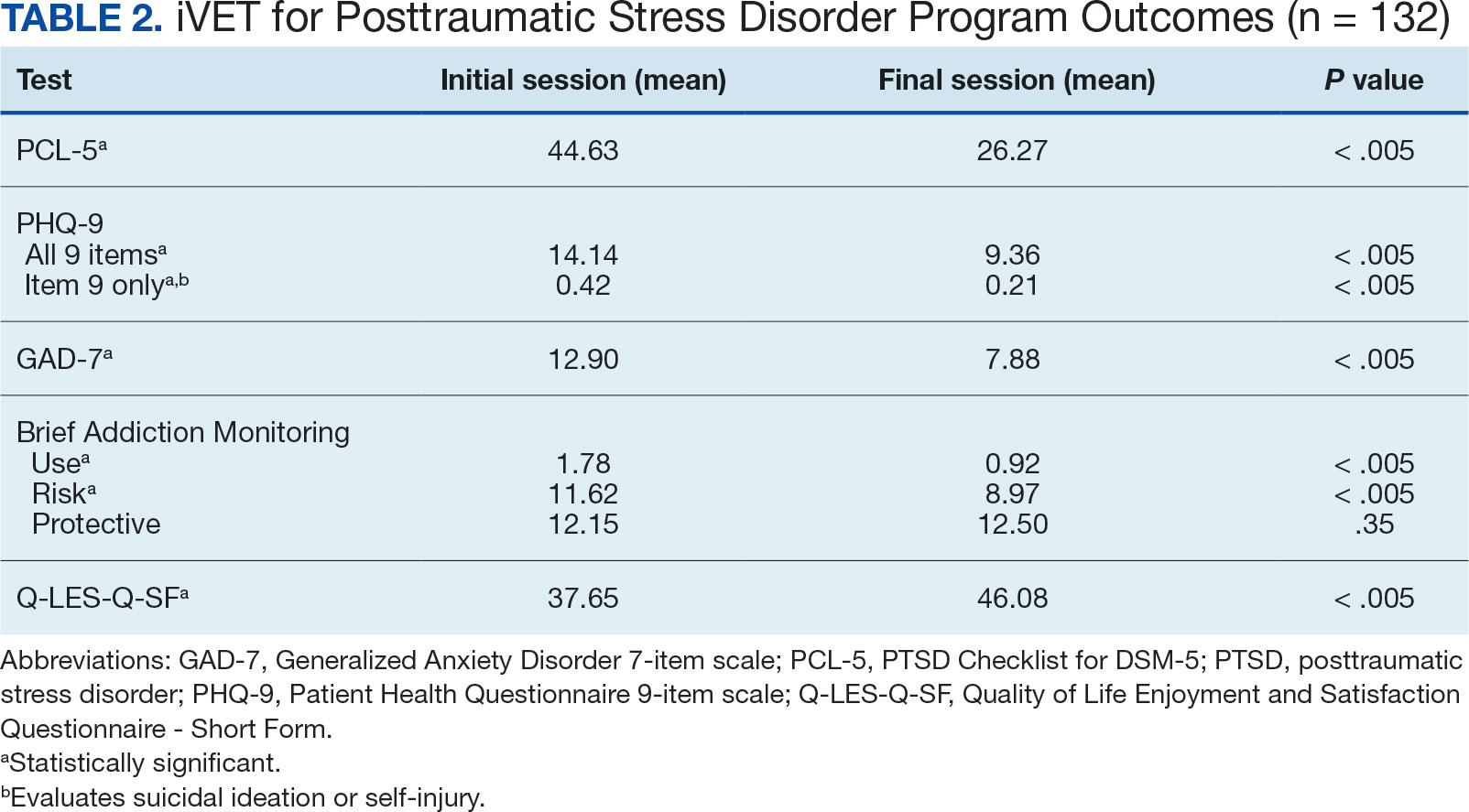

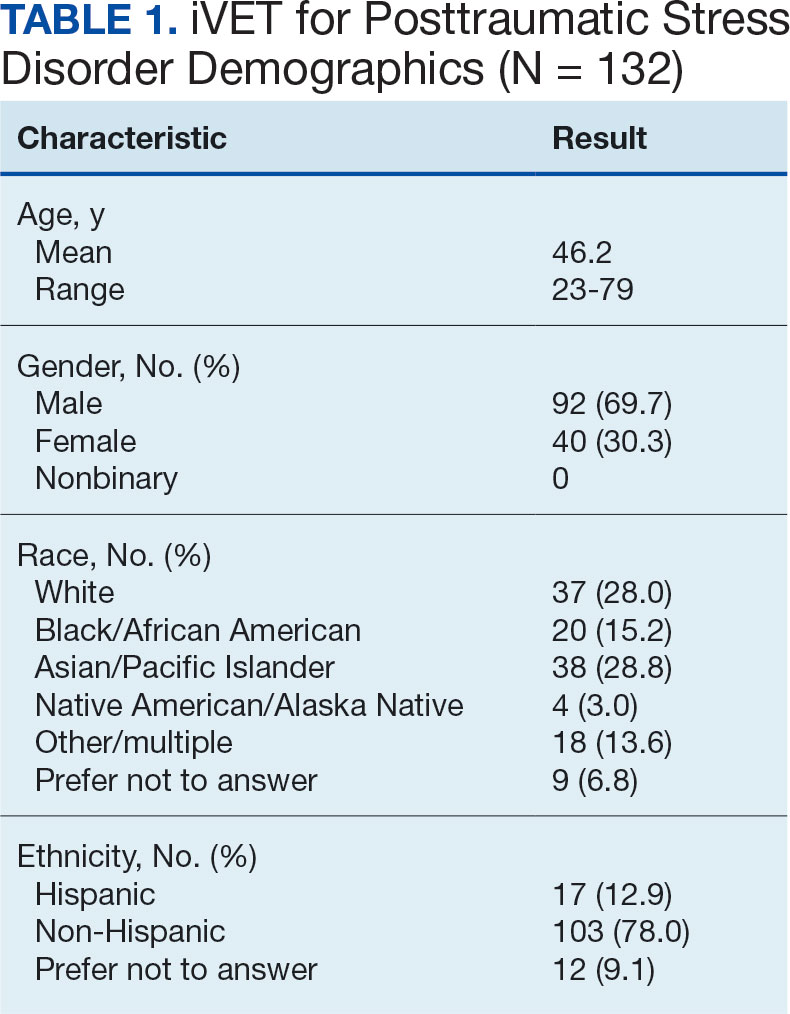

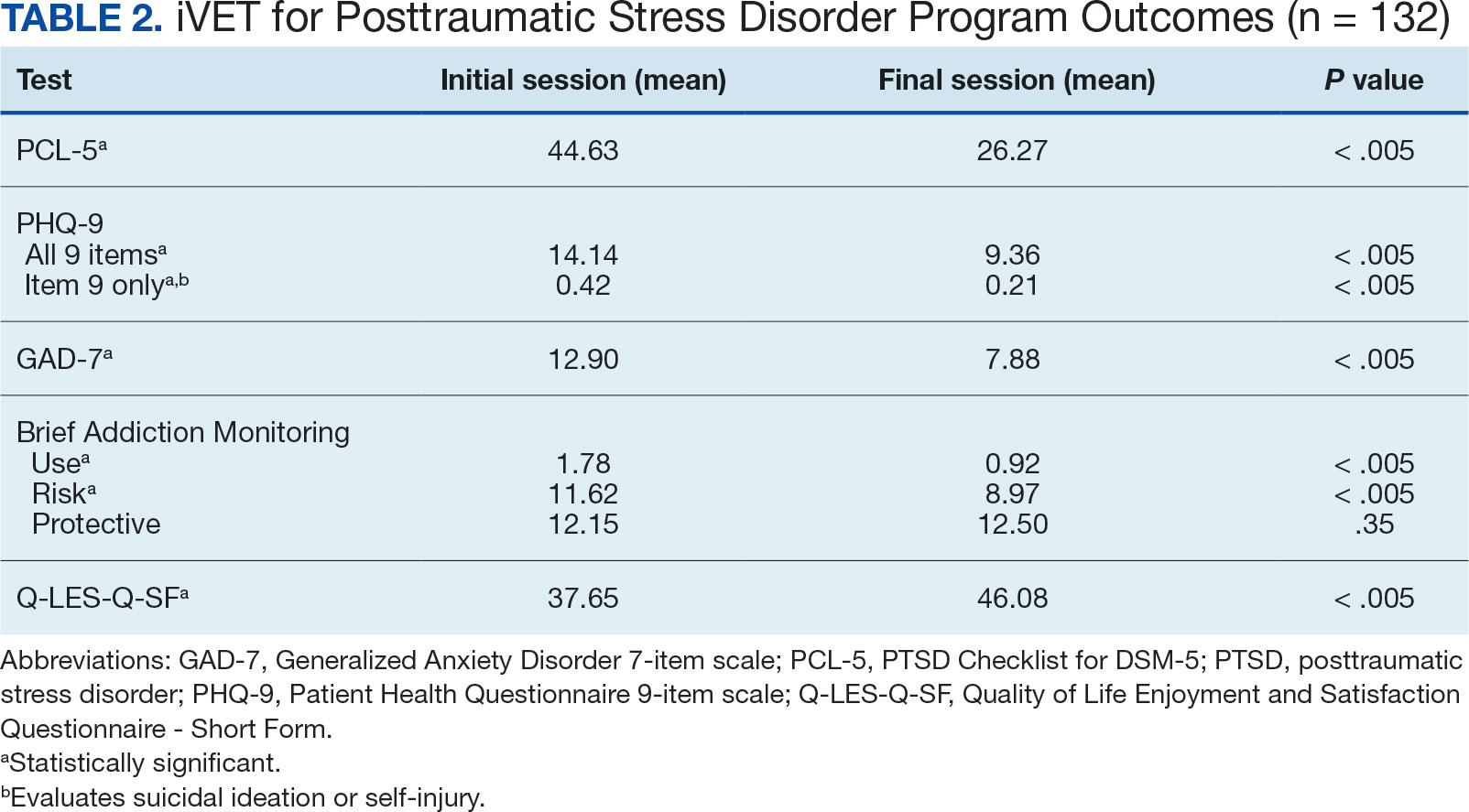

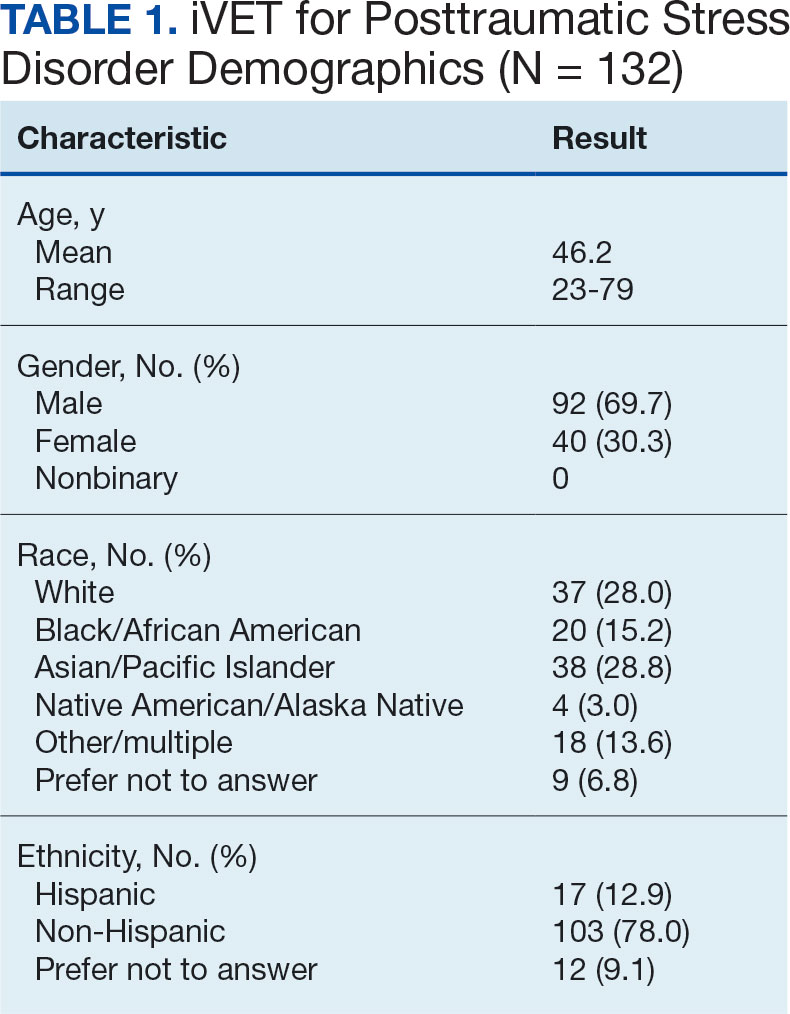

The retention rate has averaged 81% since the iVET for PTSD opened in 2022. To date, 132 veterans have completed the iVET for PTSD program, including a full course of massed PE (Table 1). Veterans experienced reduced PTSD (P < .005), depression (P < .005), anxiety (P < .005), and substance use risk (P < .005). Veterans experienced improved QOL (P < .005) and reported high satisfaction with mental health care in iVET for PTSD (Table 2). Veterans also experienced reduced thoughts of death or suicidal ideation (SI) based on PHQ-9 item 9 responses. When looking categorically at presence or absence of SI on PHQ-9 item 9, a significant relationship was found between the absence of suicidal ideation and completion of a course of massed PE: X2 (1, N = 132) = 13.75, P < .001. In addition, veterans who completed the program showed a significant decrease in severity of SI as measured continuously (range, 0-3) on PHQ-9 item 9 (P < .005).

Another important aspect to consider when implementing massed models of EBP is the impact on employee well-being and job satisfaction. The impact of EBP on staff was assessed following the initial EBP project. To explore this further, all staff members in the iVET for PTSD were invited to engage in a small program evaluation. iVET staff were guided through a visualization meditation intended to recall a typical workday 1 month prior to starting their new position with iVET. After the visualization meditation, staff completed the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale, a 30-item, self-reported questionnaire for health care workers that evaluates compassion satisfaction, perceived support, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and moral distress.28 One week later, staff were asked to complete the ProQOL again to capture their state after the first 6 months into their tenure as iVET staff. iVET employees experienced significantly increased perceived support (P < .05), reduced burnout (P < .05), reduced secondary traumatic stress (P < .05), and reduced moral distress (P < .05). Team members also remarked on the rewarding nature of the work and care model.

Future Directions

Future research should aim to sustain these outcomes as the iVET program continues to serve more veterans. Another important line of inquiry is longer-term follow-up, as exploring if outcomes are maintained over time is an important question that has not been answered in this article. In addition, we hope to see the accelerated model of care applied to treatment of other presenting concerns in mental health treatment (eg, anxiety, depression, insomnia). Expansion of accelerated mental health treatment into other federal and non-federal health care settings is another worthy direction. Finally, while short term (6 months) assessment of staff satisfaction in iVET was promising, ongoing assessment staff satisfaction over a longer timeframe (1-5 years) is also important.

CONCLUSIONS

PE for PTSD has been demonstrated to be effective and improve functioning and is supported by multiple clinical practice guidelines.1-5 However, as federal practitioners, we must consider the reality that many of the individuals who could benefit are not engaging in PE and there is a high dropout rate for those that do. It is vital that we envision a future state where access to PE for PTSD is equitable and inclusive, retention rates are dramatically improved, and clinicians providing PE do not experience high rates of burnout.

We must continue exploring how we can better care for our patients and colleagues. We posit that the development of programs, or tracks within existing programs, that provide massed or accelerated PE for PTSD with virtual delivery options is an imperative step toward improved care. Federal health care settings treating trauma-exposed patients with PTSD, such as those within the US Department of Defense, Indian Health Services, Federal Bureau of Prisons, and VA, are well positioned to implement programs like iVET. We believe this model of care has great merit and foresee a future where all patients seeking PTSD treatment have the option to complete an accelerated or massed course of PE should they so desire. The experiences outlined in this article illustrate the feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of such programs without requiring substantial staffing and financial resources.

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. February 24, 2017. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Handbook 1160.01. September 11, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/providers/sud/docs/UniformServicesHandbook1160-01.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Version 3. 2017. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VA-DoD-CPG-PTSD-Full-CPG-Edited-11162024.pdf

- Hamblen JL, Bernardy NC, Sherrieb K, et al. VA PTSD clinic director perspectives: How perceptions of readiness influence delivery of evidence-based PTSD treatment. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2015;46(2): 90-96. doi:10.1037/a0038535

- Schnurr PP, Chard KM, Ruzek JI, et al. Comparison of prolonged exposure vs cognitive processing therapy for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder among US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2136921. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen. 2021.36921

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, Polusny MA. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8(1):107-114. doi:10.1037/tra0000065

- Mott JM, Mondragon S, Hundt NE, Beason-Smith M, Grady RH, Teng EJ. Characteristics of U.S. veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27(3):265-273. doi:10.1002/jts.21927

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, et al. Measuring use of evidence based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(4):311-318. doi:10.1007/s10488-012-0421-0

- Maguen S, Holder N, Madden E, et al. Evidence-based psychotherapy trends among posttraumatic stress disorder patients in a national healthcare system, 2001-2014. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(4):356-364. doi:10.1002/da.22983

- Maguen S, Li Y, Madden E, et al. Factors associated with completing evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD among veterans in a national healthcare system. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:112-128. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.027

- Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, et al. Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(4):354-364. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21242

- Yamokoski C, Flores H, Facemire V, Maieritsch K, Perez S, Fedynich A. Feasibility of an intensive outpatient treatment program for posttraumatic stress disorder within the veterans health care administration. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(3):506-515. doi:10.1037/ser0000628

- McLean CP, Foa EB. State of the Science: Prolonged exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2024;37(4):535-550. doi:10.1002/jts.23046

- McLean CP, Levy HC, Miller ML, Tolin DF. Exposure therapy for PTSD: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;91:102115. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102115

- Wells SY, Morland LA, Wilhite ER, et al. Delivering Prolonged Exposure Therapy via Videoconferencing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Overview of the Research and Special Considerations for Providers. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(4):380-390. doi:10.1002/jts.22573

- Peterson AL, Blount TH, Foa EB, et al. Massed vs intensive outpatient prolonged exposure for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2249422. Published 2023 Jan 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49422

- Ragsdale KA, Nichols AA, Mehta M, et al. Comorbid treatment of traumatic brain injury and mental health disorders. NeuroRehabilitation. 2024;55(3):375-384. doi:10.3233/NRE-230235

- Rauch SAM, Yasinski CW, Post LM, et al. An intensive outpatient program with prolonged exposure for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: retention, predictors, and patterns of change. Psychol Serv. 2021;18(4):606-618. doi:10.1037/ser0000422

- Sherrill AM, Maples-Keller JL, Yasinski CW, Loucks LA, Rothbaum BO, Rauch SAM. Perceived benefits and drawbacks of massed prolonged exposure: qualitative thematic analysis of reactions from treatment completers. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14(5):862-870. doi:10.1037/tra0000548

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the Veterans Administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(S1):S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Dryden EM, Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, et al. Leaning Into whole health: sustaining system transformation while supporting patients and employees during COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. 2021;10:21649561211021047. doi:10.1177/21649561211021047

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Dephilippis D, et al. Development and initial evaluation of the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(3):256-263. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.013

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Kroenke K, Spi tze r RL , Wi l l i ams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Stevanovic D. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form for quality of life assessments in clinical practice: a psychometric study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(8):744-750. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01735.x

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL- 5). National Center for PTSD. Updated August 29, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.pdf

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489-498. doi:10.1002/jts.22059

- Stamm BH. The Concise ProQOL Manual. 2nd ed. Pro- QOL.org; 2010.

Evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as prolonged exposure (PE), is supported by multiple clinical practice guidelines and is expected to be available to veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1-5 However, traditional models of EBP delivery with 1 or 2 sessions weekly have high dropout rates.6,7 Few veterans who could benefit from such EBPs receive them, and those who do have low completion rates.8,9 Over a 15-year period, VHA records review of > 265,500 veterans with PTSD showed only 9.1% completed EBP treatment that included but was not limited to PE.10

One empirically supported solution that has yet to be widely implemented is delivering EBPs for PTSD in a massed or accelerated format of ≥ 3 sessions weekly.11 While these massed models of EBP delivery for PTSD are promising, their implementation is limited in federal health care settings, such as the VHA.12 PE therapy is a first-line treatment for PTSD that has been evaluated in numerous clinical trials since the early 1990s and in a wide range of trauma populations.13,14 Massed PE is effective and PE has been found to be effective both in-person and via telehealth.11,15,16

Another approach to accelerated PE is the inclusion of a massed PE course within a broader treatment context that includes augmentation of the massed PE with additional services, this is referred to as an intensive outpatient model (IOP).17 PE-IOP has also been shown to be feasible, acceptable, and effective with increased completion rates in comparison to the traditional (1 or 2 sessions weekly) model of PE.12,16,18,19 Ragsdale et al describe a 2-week IOP with multiple treatment tracks, including a PTSD track. The PTSD treatment track includes massed PE and additional standard services including case management, wellness services, family services, and a single session effective behaviors group. Additional augmentation services are available when clinically indicated (eg, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation treatment, psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, and/or relapse prevention).17

Rauch et al studied the first 80 patients completing an IOP program that consisted of PE (5 sessions weekly) and complementary interventions (eg, mindfulness and yoga) and reported a 96% retention rate, significant reductions of self-reported PTSD symptoms, significant reduction in self-reported co-occurring depression symptoms, and significant increase in self-reported satisfaction with social functioning. 18 In another study, Sherril et al explored patient reactions to participation in massed PE (5 sessions weekly) and found that patients reported significantly more positive than negative reactions. Sherrill et al noted that according to patients, the benefits of massed PE included a structured format that limits avoidance and distraction. The resulting fast pace of progress enhanced motivation; however, drawbacks included short-term discomfort and time demands.19 Yamokoski et al explored the feasibility of massed PE in a larger study of PTSD treatment in an intensive outpatient track (IOT) in a VHA PTSD clinic with minimal staffing. The 48 patients who completed IOT PTSD treatment in 2 or 4 weeks (including 35 patients who received massed PE) had high retention rates (85%), reported high satisfaction, and had significantly reduced PTSD and depression symptoms.12

The massed IOT PE model implemented by Yamokoski et al included the primary EBP intervention of massed PE with adjunctive groups. The addition of these groups increased both retention and patient-reported satisfaction. The PE-IOP model implemented by Rauch et al and Sherrill et al also included wellness and educational groups, as well as access to complementary interventions such as mindfulness and yoga.18,19 The addition of wellness education along with a primary EBP aligned with the VHA focus on whole health well-being and wellness. The whole health approach includes understanding the factors that motivate a patient toward health and well-being, provision of health education, and providing access to complementary interventions such as mindfulness.20 Dryden et al describe the whole health transformation within VHA as a proactive approach to addressing employee and patient wellness and health. Their research found that the whole health model promoted well-being in patients and staff and was sustained even during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Dryden et al also noted that use of virtual technologies facilitated and promoted continued whole health implementation. The literature illustrates that: (1) massed PE can be provided with complementary education and wellness offerings, and that such offerings may increase both retention and satisfaction by enriching the massed PE treatment (eg, delivering PE-IOP); (2) whole health including wellness education and complementary interventions (eg, mindfulness, motivational enhancement) promotes well-being in both patients and mental health professionals; and (3) whole health education and complementary interventions can be delivered virtually.

Health Care Need

Prior to the implementation of a massed EBP for PTSD program at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pacific Islands Health Care System (VAPIHCS), our setting included a traditional outpatient program for treatment of PTSD and a 12- bed residential program for treatment of PTSD for male-identified (self-identified and identified as male in the electronic medical record) veterans via a cohort model with an 8- or 9-week length of stay. Both programs were located on Oahu. Thus, veterans who received care at VAPIHCS had access to PE in both outpatient and residential settings and via in-person and telehealth modalities. However, their access to PE was limited to the traditional models of PE delivery (eg, 1 or 2 session per week) and very few veterans outside of the island of Oahu had accessed PE treatment for PTSD. Moreover, when looking at PE reach within VAPIHCS, in the fiscal year prior to the implementation of the massed EBP program, only 32 of the > 5000 eligible veterans with a PTSD diagnosis had received PE. VAPIHCS serves veterans in a catchment area across the Pacific Basin which includes 3 time zones: Hawaii Standard Time (HST), Chamorro Standard Time (ChST), and Samoa Standard Time (SST). ChST is 20 hours ahead of HST, making service delivery that is inclusive for patients in Guam and Saipan especially challenging when providing care from Hawaii or other US states or territories. Given all of this, implementation of a new program offering accelerated PE virtually to any veterans with PTSD within the VAPIHCS would increase access to and reduce barriers to receiving PE.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The Intensive Virtual EBP Team (iVET) for PTSD consists of an accelerated course of PE therapy and whole health education provided via VA Video Connect (VVC). iVET is a 3-week program and includes 3 parts: (1) massed individual PE therapy for PTSD; (2) group whole health and wellness classes; and (3) individual health coaching to address personal wellness goals. Programming is offered over 10-hour days to increase access across multiple time zones, especially to allow for participation in Guam and Saipan.

When a patient is referred to the iVET, their first contact is a video (or telephone) appointment with a registered nurse (RN) for a screening session. The screening session is designed to educate the patient about the program, including interventions, time commitment, and resources required for participation. In addition, following the educational discussion, the RN completes screening for safety with the patient including suicidal ideation and risk, as well as intimate partner violence risk. If urgent safety concerns are present, a licensed social worker or psychologist will join the screening to complete further assessment of risk and to address any safety concerns. Following screening, patients are scheduled for a VVC intake with a licensed therapist (social worker or psychologist) to complete the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition), a clinical interview for PTSD assessment. Patients are also sent a secure link to complete a measurement-based care (MBC) battery of self-report measures including measures assessing demographics, PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, substance use, quality of life (QOL), and satisfaction with mental health care. The results of the CAPS-5 and self-report measures are discussed with the patient during the intake session when planning next steps and engaging in shared decision-making. This initial VVC intake not only allows for diagnostic goodness of fit but also provides the opportunity to troubleshoot any technical difficulties the patients might have with the virtual platforms.

There are minimal exclusion criteria for participation in iVET, which include active unmanaged psychosis or manic symptoms, recent suicidal crises (attempt within 8 weeks), active nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors (within 8 weeks), and moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment. Following intake, patients are scheduled to begin their course of care with iVET. Upon completion of intake, patients are sent program materials for their individual and group classes, asked to obtain or request a recording device, and told they will receive email links for all VVC appointments. Patients are admitted to the iVET in a rolling admission fashion, thereby increasing access when compared to closed group and/or cohort models of care.

Patients receiving care in iVET attend 2 or 3 telehealth appointments daily with practice exercises daily between telehealth sessions. The primary EBP intervention in the iVET for PTSD program is a massed or accelerated course of PE, which includes 4 primary components: psychoeducation, in-vivo exposure, imaginal exposure, and breathing retraining. Specifically, PE is delivered in 4 90-minute individual sessions weekly allowing completion of the full PE protocol, to fidelity, in 3 weeks. In addition to receiving this primary intervention, patients also participate in four 50-minute group sessions per week of a whole health and wellness education class and have access to one 30- to 60-minute session weekly of individual health coaching should they wish to set wellness goals and receive coaching in support of attaining wellness goals. During iVET, patients are invited to complete MBC batteries of selfreport measures including measures assessing PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, substance use, QOL, and satisfaction with mental health care at sessions 1, 5, 9, and the final session of PE. Following discharge from the iVET, patients are offered 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month individual postdischarge check-up sessions with a therapist where they are invited to complete MBC measures and review relapse prevention and maintenance of treatment gains. Likewise, they are offered 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month postdischarge check-up sessions with an RN focused on maintaining wellness gains.

The iVET for PTSD staff includes 3 therapists (psychologists or social workers) and an RN. Additionally, the iVET for PTSD is supported by a program manager and a program support assistant. The primary cost of the program is salary for staff. Additional iVET for PTSD resources included computer equipment for staff and minimal supplies. Due to the virtual environment of care, iVET staff telework and do not require physical space within VAPIHCS.

OUTCOMES

All veterans receiving care in iVET for PTSD are invited to complete a MBC at multiple timepoints including pretreatment, during PE treatment, and posttreatment. The MBC measures included self-reported demographics, a 2-item measure of satisfaction with mental health services, the Brief Addiction Monitor-Intensive Outpatient Program questionnaire,22 the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale,23, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),24 the QOL Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire- Short Form,25 and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), both weekly and monthly versions. 26,27

The retention rate has averaged 81% since the iVET for PTSD opened in 2022. To date, 132 veterans have completed the iVET for PTSD program, including a full course of massed PE (Table 1). Veterans experienced reduced PTSD (P < .005), depression (P < .005), anxiety (P < .005), and substance use risk (P < .005). Veterans experienced improved QOL (P < .005) and reported high satisfaction with mental health care in iVET for PTSD (Table 2). Veterans also experienced reduced thoughts of death or suicidal ideation (SI) based on PHQ-9 item 9 responses. When looking categorically at presence or absence of SI on PHQ-9 item 9, a significant relationship was found between the absence of suicidal ideation and completion of a course of massed PE: X2 (1, N = 132) = 13.75, P < .001. In addition, veterans who completed the program showed a significant decrease in severity of SI as measured continuously (range, 0-3) on PHQ-9 item 9 (P < .005).

Another important aspect to consider when implementing massed models of EBP is the impact on employee well-being and job satisfaction. The impact of EBP on staff was assessed following the initial EBP project. To explore this further, all staff members in the iVET for PTSD were invited to engage in a small program evaluation. iVET staff were guided through a visualization meditation intended to recall a typical workday 1 month prior to starting their new position with iVET. After the visualization meditation, staff completed the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale, a 30-item, self-reported questionnaire for health care workers that evaluates compassion satisfaction, perceived support, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and moral distress.28 One week later, staff were asked to complete the ProQOL again to capture their state after the first 6 months into their tenure as iVET staff. iVET employees experienced significantly increased perceived support (P < .05), reduced burnout (P < .05), reduced secondary traumatic stress (P < .05), and reduced moral distress (P < .05). Team members also remarked on the rewarding nature of the work and care model.

Future Directions

Future research should aim to sustain these outcomes as the iVET program continues to serve more veterans. Another important line of inquiry is longer-term follow-up, as exploring if outcomes are maintained over time is an important question that has not been answered in this article. In addition, we hope to see the accelerated model of care applied to treatment of other presenting concerns in mental health treatment (eg, anxiety, depression, insomnia). Expansion of accelerated mental health treatment into other federal and non-federal health care settings is another worthy direction. Finally, while short term (6 months) assessment of staff satisfaction in iVET was promising, ongoing assessment staff satisfaction over a longer timeframe (1-5 years) is also important.

CONCLUSIONS

PE for PTSD has been demonstrated to be effective and improve functioning and is supported by multiple clinical practice guidelines.1-5 However, as federal practitioners, we must consider the reality that many of the individuals who could benefit are not engaging in PE and there is a high dropout rate for those that do. It is vital that we envision a future state where access to PE for PTSD is equitable and inclusive, retention rates are dramatically improved, and clinicians providing PE do not experience high rates of burnout.

We must continue exploring how we can better care for our patients and colleagues. We posit that the development of programs, or tracks within existing programs, that provide massed or accelerated PE for PTSD with virtual delivery options is an imperative step toward improved care. Federal health care settings treating trauma-exposed patients with PTSD, such as those within the US Department of Defense, Indian Health Services, Federal Bureau of Prisons, and VA, are well positioned to implement programs like iVET. We believe this model of care has great merit and foresee a future where all patients seeking PTSD treatment have the option to complete an accelerated or massed course of PE should they so desire. The experiences outlined in this article illustrate the feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of such programs without requiring substantial staffing and financial resources.

Evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as prolonged exposure (PE), is supported by multiple clinical practice guidelines and is expected to be available to veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1-5 However, traditional models of EBP delivery with 1 or 2 sessions weekly have high dropout rates.6,7 Few veterans who could benefit from such EBPs receive them, and those who do have low completion rates.8,9 Over a 15-year period, VHA records review of > 265,500 veterans with PTSD showed only 9.1% completed EBP treatment that included but was not limited to PE.10

One empirically supported solution that has yet to be widely implemented is delivering EBPs for PTSD in a massed or accelerated format of ≥ 3 sessions weekly.11 While these massed models of EBP delivery for PTSD are promising, their implementation is limited in federal health care settings, such as the VHA.12 PE therapy is a first-line treatment for PTSD that has been evaluated in numerous clinical trials since the early 1990s and in a wide range of trauma populations.13,14 Massed PE is effective and PE has been found to be effective both in-person and via telehealth.11,15,16

Another approach to accelerated PE is the inclusion of a massed PE course within a broader treatment context that includes augmentation of the massed PE with additional services, this is referred to as an intensive outpatient model (IOP).17 PE-IOP has also been shown to be feasible, acceptable, and effective with increased completion rates in comparison to the traditional (1 or 2 sessions weekly) model of PE.12,16,18,19 Ragsdale et al describe a 2-week IOP with multiple treatment tracks, including a PTSD track. The PTSD treatment track includes massed PE and additional standard services including case management, wellness services, family services, and a single session effective behaviors group. Additional augmentation services are available when clinically indicated (eg, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation treatment, psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, and/or relapse prevention).17

Rauch et al studied the first 80 patients completing an IOP program that consisted of PE (5 sessions weekly) and complementary interventions (eg, mindfulness and yoga) and reported a 96% retention rate, significant reductions of self-reported PTSD symptoms, significant reduction in self-reported co-occurring depression symptoms, and significant increase in self-reported satisfaction with social functioning. 18 In another study, Sherril et al explored patient reactions to participation in massed PE (5 sessions weekly) and found that patients reported significantly more positive than negative reactions. Sherrill et al noted that according to patients, the benefits of massed PE included a structured format that limits avoidance and distraction. The resulting fast pace of progress enhanced motivation; however, drawbacks included short-term discomfort and time demands.19 Yamokoski et al explored the feasibility of massed PE in a larger study of PTSD treatment in an intensive outpatient track (IOT) in a VHA PTSD clinic with minimal staffing. The 48 patients who completed IOT PTSD treatment in 2 or 4 weeks (including 35 patients who received massed PE) had high retention rates (85%), reported high satisfaction, and had significantly reduced PTSD and depression symptoms.12

The massed IOT PE model implemented by Yamokoski et al included the primary EBP intervention of massed PE with adjunctive groups. The addition of these groups increased both retention and patient-reported satisfaction. The PE-IOP model implemented by Rauch et al and Sherrill et al also included wellness and educational groups, as well as access to complementary interventions such as mindfulness and yoga.18,19 The addition of wellness education along with a primary EBP aligned with the VHA focus on whole health well-being and wellness. The whole health approach includes understanding the factors that motivate a patient toward health and well-being, provision of health education, and providing access to complementary interventions such as mindfulness.20 Dryden et al describe the whole health transformation within VHA as a proactive approach to addressing employee and patient wellness and health. Their research found that the whole health model promoted well-being in patients and staff and was sustained even during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Dryden et al also noted that use of virtual technologies facilitated and promoted continued whole health implementation. The literature illustrates that: (1) massed PE can be provided with complementary education and wellness offerings, and that such offerings may increase both retention and satisfaction by enriching the massed PE treatment (eg, delivering PE-IOP); (2) whole health including wellness education and complementary interventions (eg, mindfulness, motivational enhancement) promotes well-being in both patients and mental health professionals; and (3) whole health education and complementary interventions can be delivered virtually.

Health Care Need

Prior to the implementation of a massed EBP for PTSD program at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pacific Islands Health Care System (VAPIHCS), our setting included a traditional outpatient program for treatment of PTSD and a 12- bed residential program for treatment of PTSD for male-identified (self-identified and identified as male in the electronic medical record) veterans via a cohort model with an 8- or 9-week length of stay. Both programs were located on Oahu. Thus, veterans who received care at VAPIHCS had access to PE in both outpatient and residential settings and via in-person and telehealth modalities. However, their access to PE was limited to the traditional models of PE delivery (eg, 1 or 2 session per week) and very few veterans outside of the island of Oahu had accessed PE treatment for PTSD. Moreover, when looking at PE reach within VAPIHCS, in the fiscal year prior to the implementation of the massed EBP program, only 32 of the > 5000 eligible veterans with a PTSD diagnosis had received PE. VAPIHCS serves veterans in a catchment area across the Pacific Basin which includes 3 time zones: Hawaii Standard Time (HST), Chamorro Standard Time (ChST), and Samoa Standard Time (SST). ChST is 20 hours ahead of HST, making service delivery that is inclusive for patients in Guam and Saipan especially challenging when providing care from Hawaii or other US states or territories. Given all of this, implementation of a new program offering accelerated PE virtually to any veterans with PTSD within the VAPIHCS would increase access to and reduce barriers to receiving PE.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The Intensive Virtual EBP Team (iVET) for PTSD consists of an accelerated course of PE therapy and whole health education provided via VA Video Connect (VVC). iVET is a 3-week program and includes 3 parts: (1) massed individual PE therapy for PTSD; (2) group whole health and wellness classes; and (3) individual health coaching to address personal wellness goals. Programming is offered over 10-hour days to increase access across multiple time zones, especially to allow for participation in Guam and Saipan.

When a patient is referred to the iVET, their first contact is a video (or telephone) appointment with a registered nurse (RN) for a screening session. The screening session is designed to educate the patient about the program, including interventions, time commitment, and resources required for participation. In addition, following the educational discussion, the RN completes screening for safety with the patient including suicidal ideation and risk, as well as intimate partner violence risk. If urgent safety concerns are present, a licensed social worker or psychologist will join the screening to complete further assessment of risk and to address any safety concerns. Following screening, patients are scheduled for a VVC intake with a licensed therapist (social worker or psychologist) to complete the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition), a clinical interview for PTSD assessment. Patients are also sent a secure link to complete a measurement-based care (MBC) battery of self-report measures including measures assessing demographics, PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, substance use, quality of life (QOL), and satisfaction with mental health care. The results of the CAPS-5 and self-report measures are discussed with the patient during the intake session when planning next steps and engaging in shared decision-making. This initial VVC intake not only allows for diagnostic goodness of fit but also provides the opportunity to troubleshoot any technical difficulties the patients might have with the virtual platforms.

There are minimal exclusion criteria for participation in iVET, which include active unmanaged psychosis or manic symptoms, recent suicidal crises (attempt within 8 weeks), active nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors (within 8 weeks), and moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment. Following intake, patients are scheduled to begin their course of care with iVET. Upon completion of intake, patients are sent program materials for their individual and group classes, asked to obtain or request a recording device, and told they will receive email links for all VVC appointments. Patients are admitted to the iVET in a rolling admission fashion, thereby increasing access when compared to closed group and/or cohort models of care.

Patients receiving care in iVET attend 2 or 3 telehealth appointments daily with practice exercises daily between telehealth sessions. The primary EBP intervention in the iVET for PTSD program is a massed or accelerated course of PE, which includes 4 primary components: psychoeducation, in-vivo exposure, imaginal exposure, and breathing retraining. Specifically, PE is delivered in 4 90-minute individual sessions weekly allowing completion of the full PE protocol, to fidelity, in 3 weeks. In addition to receiving this primary intervention, patients also participate in four 50-minute group sessions per week of a whole health and wellness education class and have access to one 30- to 60-minute session weekly of individual health coaching should they wish to set wellness goals and receive coaching in support of attaining wellness goals. During iVET, patients are invited to complete MBC batteries of selfreport measures including measures assessing PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, substance use, QOL, and satisfaction with mental health care at sessions 1, 5, 9, and the final session of PE. Following discharge from the iVET, patients are offered 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month individual postdischarge check-up sessions with a therapist where they are invited to complete MBC measures and review relapse prevention and maintenance of treatment gains. Likewise, they are offered 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month postdischarge check-up sessions with an RN focused on maintaining wellness gains.

The iVET for PTSD staff includes 3 therapists (psychologists or social workers) and an RN. Additionally, the iVET for PTSD is supported by a program manager and a program support assistant. The primary cost of the program is salary for staff. Additional iVET for PTSD resources included computer equipment for staff and minimal supplies. Due to the virtual environment of care, iVET staff telework and do not require physical space within VAPIHCS.

OUTCOMES

All veterans receiving care in iVET for PTSD are invited to complete a MBC at multiple timepoints including pretreatment, during PE treatment, and posttreatment. The MBC measures included self-reported demographics, a 2-item measure of satisfaction with mental health services, the Brief Addiction Monitor-Intensive Outpatient Program questionnaire,22 the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale,23, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),24 the QOL Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire- Short Form,25 and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), both weekly and monthly versions. 26,27

The retention rate has averaged 81% since the iVET for PTSD opened in 2022. To date, 132 veterans have completed the iVET for PTSD program, including a full course of massed PE (Table 1). Veterans experienced reduced PTSD (P < .005), depression (P < .005), anxiety (P < .005), and substance use risk (P < .005). Veterans experienced improved QOL (P < .005) and reported high satisfaction with mental health care in iVET for PTSD (Table 2). Veterans also experienced reduced thoughts of death or suicidal ideation (SI) based on PHQ-9 item 9 responses. When looking categorically at presence or absence of SI on PHQ-9 item 9, a significant relationship was found between the absence of suicidal ideation and completion of a course of massed PE: X2 (1, N = 132) = 13.75, P < .001. In addition, veterans who completed the program showed a significant decrease in severity of SI as measured continuously (range, 0-3) on PHQ-9 item 9 (P < .005).

Another important aspect to consider when implementing massed models of EBP is the impact on employee well-being and job satisfaction. The impact of EBP on staff was assessed following the initial EBP project. To explore this further, all staff members in the iVET for PTSD were invited to engage in a small program evaluation. iVET staff were guided through a visualization meditation intended to recall a typical workday 1 month prior to starting their new position with iVET. After the visualization meditation, staff completed the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale, a 30-item, self-reported questionnaire for health care workers that evaluates compassion satisfaction, perceived support, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and moral distress.28 One week later, staff were asked to complete the ProQOL again to capture their state after the first 6 months into their tenure as iVET staff. iVET employees experienced significantly increased perceived support (P < .05), reduced burnout (P < .05), reduced secondary traumatic stress (P < .05), and reduced moral distress (P < .05). Team members also remarked on the rewarding nature of the work and care model.

Future Directions

Future research should aim to sustain these outcomes as the iVET program continues to serve more veterans. Another important line of inquiry is longer-term follow-up, as exploring if outcomes are maintained over time is an important question that has not been answered in this article. In addition, we hope to see the accelerated model of care applied to treatment of other presenting concerns in mental health treatment (eg, anxiety, depression, insomnia). Expansion of accelerated mental health treatment into other federal and non-federal health care settings is another worthy direction. Finally, while short term (6 months) assessment of staff satisfaction in iVET was promising, ongoing assessment staff satisfaction over a longer timeframe (1-5 years) is also important.

CONCLUSIONS

PE for PTSD has been demonstrated to be effective and improve functioning and is supported by multiple clinical practice guidelines.1-5 However, as federal practitioners, we must consider the reality that many of the individuals who could benefit are not engaging in PE and there is a high dropout rate for those that do. It is vital that we envision a future state where access to PE for PTSD is equitable and inclusive, retention rates are dramatically improved, and clinicians providing PE do not experience high rates of burnout.

We must continue exploring how we can better care for our patients and colleagues. We posit that the development of programs, or tracks within existing programs, that provide massed or accelerated PE for PTSD with virtual delivery options is an imperative step toward improved care. Federal health care settings treating trauma-exposed patients with PTSD, such as those within the US Department of Defense, Indian Health Services, Federal Bureau of Prisons, and VA, are well positioned to implement programs like iVET. We believe this model of care has great merit and foresee a future where all patients seeking PTSD treatment have the option to complete an accelerated or massed course of PE should they so desire. The experiences outlined in this article illustrate the feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of such programs without requiring substantial staffing and financial resources.

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. February 24, 2017. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Handbook 1160.01. September 11, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/providers/sud/docs/UniformServicesHandbook1160-01.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Version 3. 2017. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VA-DoD-CPG-PTSD-Full-CPG-Edited-11162024.pdf

- Hamblen JL, Bernardy NC, Sherrieb K, et al. VA PTSD clinic director perspectives: How perceptions of readiness influence delivery of evidence-based PTSD treatment. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2015;46(2): 90-96. doi:10.1037/a0038535

- Schnurr PP, Chard KM, Ruzek JI, et al. Comparison of prolonged exposure vs cognitive processing therapy for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder among US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2136921. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen. 2021.36921

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, Polusny MA. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8(1):107-114. doi:10.1037/tra0000065

- Mott JM, Mondragon S, Hundt NE, Beason-Smith M, Grady RH, Teng EJ. Characteristics of U.S. veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27(3):265-273. doi:10.1002/jts.21927

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, et al. Measuring use of evidence based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(4):311-318. doi:10.1007/s10488-012-0421-0

- Maguen S, Holder N, Madden E, et al. Evidence-based psychotherapy trends among posttraumatic stress disorder patients in a national healthcare system, 2001-2014. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(4):356-364. doi:10.1002/da.22983

- Maguen S, Li Y, Madden E, et al. Factors associated with completing evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD among veterans in a national healthcare system. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:112-128. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.027

- Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, et al. Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(4):354-364. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21242

- Yamokoski C, Flores H, Facemire V, Maieritsch K, Perez S, Fedynich A. Feasibility of an intensive outpatient treatment program for posttraumatic stress disorder within the veterans health care administration. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(3):506-515. doi:10.1037/ser0000628

- McLean CP, Foa EB. State of the Science: Prolonged exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2024;37(4):535-550. doi:10.1002/jts.23046

- McLean CP, Levy HC, Miller ML, Tolin DF. Exposure therapy for PTSD: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;91:102115. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102115

- Wells SY, Morland LA, Wilhite ER, et al. Delivering Prolonged Exposure Therapy via Videoconferencing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Overview of the Research and Special Considerations for Providers. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(4):380-390. doi:10.1002/jts.22573

- Peterson AL, Blount TH, Foa EB, et al. Massed vs intensive outpatient prolonged exposure for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2249422. Published 2023 Jan 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49422

- Ragsdale KA, Nichols AA, Mehta M, et al. Comorbid treatment of traumatic brain injury and mental health disorders. NeuroRehabilitation. 2024;55(3):375-384. doi:10.3233/NRE-230235

- Rauch SAM, Yasinski CW, Post LM, et al. An intensive outpatient program with prolonged exposure for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: retention, predictors, and patterns of change. Psychol Serv. 2021;18(4):606-618. doi:10.1037/ser0000422

- Sherrill AM, Maples-Keller JL, Yasinski CW, Loucks LA, Rothbaum BO, Rauch SAM. Perceived benefits and drawbacks of massed prolonged exposure: qualitative thematic analysis of reactions from treatment completers. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14(5):862-870. doi:10.1037/tra0000548

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the Veterans Administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(S1):S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Dryden EM, Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, et al. Leaning Into whole health: sustaining system transformation while supporting patients and employees during COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. 2021;10:21649561211021047. doi:10.1177/21649561211021047

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Dephilippis D, et al. Development and initial evaluation of the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(3):256-263. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.013

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Kroenke K, Spi tze r RL , Wi l l i ams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Stevanovic D. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form for quality of life assessments in clinical practice: a psychometric study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(8):744-750. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01735.x

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL- 5). National Center for PTSD. Updated August 29, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.pdf

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489-498. doi:10.1002/jts.22059

- Stamm BH. The Concise ProQOL Manual. 2nd ed. Pro- QOL.org; 2010.

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. February 24, 2017. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Handbook 1160.01. September 11, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/providers/sud/docs/UniformServicesHandbook1160-01.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Version 3. 2017. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VA-DoD-CPG-PTSD-Full-CPG-Edited-11162024.pdf

- Hamblen JL, Bernardy NC, Sherrieb K, et al. VA PTSD clinic director perspectives: How perceptions of readiness influence delivery of evidence-based PTSD treatment. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2015;46(2): 90-96. doi:10.1037/a0038535

- Schnurr PP, Chard KM, Ruzek JI, et al. Comparison of prolonged exposure vs cognitive processing therapy for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder among US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2136921. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen. 2021.36921

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, Polusny MA. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8(1):107-114. doi:10.1037/tra0000065

- Mott JM, Mondragon S, Hundt NE, Beason-Smith M, Grady RH, Teng EJ. Characteristics of U.S. veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27(3):265-273. doi:10.1002/jts.21927

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, et al. Measuring use of evidence based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(4):311-318. doi:10.1007/s10488-012-0421-0

- Maguen S, Holder N, Madden E, et al. Evidence-based psychotherapy trends among posttraumatic stress disorder patients in a national healthcare system, 2001-2014. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(4):356-364. doi:10.1002/da.22983

- Maguen S, Li Y, Madden E, et al. Factors associated with completing evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD among veterans in a national healthcare system. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:112-128. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.027

- Foa EB, McLean CP, Zang Y, et al. Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(4):354-364. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21242

- Yamokoski C, Flores H, Facemire V, Maieritsch K, Perez S, Fedynich A. Feasibility of an intensive outpatient treatment program for posttraumatic stress disorder within the veterans health care administration. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(3):506-515. doi:10.1037/ser0000628

- McLean CP, Foa EB. State of the Science: Prolonged exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2024;37(4):535-550. doi:10.1002/jts.23046

- McLean CP, Levy HC, Miller ML, Tolin DF. Exposure therapy for PTSD: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;91:102115. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102115

- Wells SY, Morland LA, Wilhite ER, et al. Delivering Prolonged Exposure Therapy via Videoconferencing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Overview of the Research and Special Considerations for Providers. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(4):380-390. doi:10.1002/jts.22573

- Peterson AL, Blount TH, Foa EB, et al. Massed vs intensive outpatient prolonged exposure for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2249422. Published 2023 Jan 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49422

- Ragsdale KA, Nichols AA, Mehta M, et al. Comorbid treatment of traumatic brain injury and mental health disorders. NeuroRehabilitation. 2024;55(3):375-384. doi:10.3233/NRE-230235

- Rauch SAM, Yasinski CW, Post LM, et al. An intensive outpatient program with prolonged exposure for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: retention, predictors, and patterns of change. Psychol Serv. 2021;18(4):606-618. doi:10.1037/ser0000422

- Sherrill AM, Maples-Keller JL, Yasinski CW, Loucks LA, Rothbaum BO, Rauch SAM. Perceived benefits and drawbacks of massed prolonged exposure: qualitative thematic analysis of reactions from treatment completers. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14(5):862-870. doi:10.1037/tra0000548

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the Veterans Administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(S1):S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Dryden EM, Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, et al. Leaning Into whole health: sustaining system transformation while supporting patients and employees during COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. 2021;10:21649561211021047. doi:10.1177/21649561211021047

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Dephilippis D, et al. Development and initial evaluation of the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(3):256-263. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.013

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Kroenke K, Spi tze r RL , Wi l l i ams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Stevanovic D. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form for quality of life assessments in clinical practice: a psychometric study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(8):744-750. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01735.x

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL- 5). National Center for PTSD. Updated August 29, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.pdf

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489-498. doi:10.1002/jts.22059

- Stamm BH. The Concise ProQOL Manual. 2nd ed. Pro- QOL.org; 2010.

Accelerated Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Veterans Health Administration System

Accelerated Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Veterans Health Administration System

VA is a Leader in Mental Health and Social Service Research and Operations

VA is a Leader in Mental Health and Social Service Research and Operations

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mission is defined by President Abraham Lincoln’s promise “to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan.” Critically, the biopsychosocial needs of veterans differ from the needs of civilians due to the nature of military service.1 Veterans commonly experience traumatic brain injury (TBI) due to combat- or training-related injuries.2 Psychologically, veterans are disproportionately likely to be diagnosed with mental health conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), often linked to military exposures.3 Spiritually, veterans frequently express moral injury after living through circumstances when they perpetrate, fail to prevent, or witness events that contradict moral beliefs/ expectations.4 Veterans also have significant social challenges, including high rates of homelessness. 5 A critical strength of the VA mission is its awareness of these complex sequelae and its ability to provide well-informed treatment and social services to meet veterans’ unique needs.

Foundational to a well-informed health care system is a robust research and operational quality improvement infrastructure. The VA Office of Research and Development (ORD) has worked tirelessly to understand and address the unique, idiographic needs of veterans. In 2024 the ORD had a budget of $2.4 billion, excluding quality improvement initiatives enhancing VA operations.6

The integrated VA health care system is a major strength for providing state-of-the-science to inform veterans’ treatment and social service needs. The VA features medical centers and clinics capable of synergistically leveraging extant infrastructure to facilitate collaborations and centralized procedures across sites. The VA also has dedicated research centers, such as the National Center for PTSD, Centers of Excellence, Centers of Innovation, and Mental Illness, Research, Education and Clinical Centers that focus on PTSD, suicide prevention, TBI, and other high-priority areas. These centers recruit, train, and invest in experts dedicated to improving veterans’ lives. The VA Corporate Data Warehouse provides a national, system-wide repository for patient-level data, allowing for advanced analysis of large datasets.7

This special issue is a showcase of the strengths of VA mental health and social service research, aligning with the current strategic priorities of VA research. Topics focus on the unique needs of veterans, including sequelae (eg, PTSD, homelessness, moral injury), with particular attention to veterans. Manuscripts highlight the strengths of collaborations, including those between specialized research centers and national VA operational partners. Analyses highlight the VA research approach, leveraging data and perspectives from inside and outside the VA, and studying new and established approaches to care. This issue highlights the distinct advantages that VA research provides: experts with the tools, experience, and dedication to addressing the unique needs of veterans. Given the passion for veteran care among VA researchers, including those featured in this issue, we strongly believe the VA will continue to be a leader in this research.

- Oster C, Morello A, Venning A, Redpath P, Lawn S. The health and wellbeing needs of veterans: a rapid review. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):414. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1547-0

- Cypel YS, Vogt D, Maguen S, et al. Physical health of Post- 9/11 U.S. military veterans in the context of Healthy People 2020 targeted topic areas: results from the Comparative Health Assessment Interview Research Study. Prev Med Rep. 2023;32:102122. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102122

- Lehavot K, Katon JG, Chen JA, Fortney JC, Simpson TL. Post-traumatic stress disorder by gender and veteran Status. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(1):e1-e9. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.008

- Griffin BJ, Purcell N, Burkman K, et al. Moral injury: an integrative review. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(3):350-362. doi:10.1002/jts.22362

- Tsai J, Pietrzak RH, Szymkowiak D. The problem of veteran homelessness: an update for the new decade. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(6):774-780. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.12.012

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. About the office of research & development. Updated January 22, 2025. Accessed March 18, 2025. https://www.research.va.gov/about/default.cfm

- Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, et al. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1203-1211. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0054

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mission is defined by President Abraham Lincoln’s promise “to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan.” Critically, the biopsychosocial needs of veterans differ from the needs of civilians due to the nature of military service.1 Veterans commonly experience traumatic brain injury (TBI) due to combat- or training-related injuries.2 Psychologically, veterans are disproportionately likely to be diagnosed with mental health conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), often linked to military exposures.3 Spiritually, veterans frequently express moral injury after living through circumstances when they perpetrate, fail to prevent, or witness events that contradict moral beliefs/ expectations.4 Veterans also have significant social challenges, including high rates of homelessness. 5 A critical strength of the VA mission is its awareness of these complex sequelae and its ability to provide well-informed treatment and social services to meet veterans’ unique needs.

Foundational to a well-informed health care system is a robust research and operational quality improvement infrastructure. The VA Office of Research and Development (ORD) has worked tirelessly to understand and address the unique, idiographic needs of veterans. In 2024 the ORD had a budget of $2.4 billion, excluding quality improvement initiatives enhancing VA operations.6

The integrated VA health care system is a major strength for providing state-of-the-science to inform veterans’ treatment and social service needs. The VA features medical centers and clinics capable of synergistically leveraging extant infrastructure to facilitate collaborations and centralized procedures across sites. The VA also has dedicated research centers, such as the National Center for PTSD, Centers of Excellence, Centers of Innovation, and Mental Illness, Research, Education and Clinical Centers that focus on PTSD, suicide prevention, TBI, and other high-priority areas. These centers recruit, train, and invest in experts dedicated to improving veterans’ lives. The VA Corporate Data Warehouse provides a national, system-wide repository for patient-level data, allowing for advanced analysis of large datasets.7

This special issue is a showcase of the strengths of VA mental health and social service research, aligning with the current strategic priorities of VA research. Topics focus on the unique needs of veterans, including sequelae (eg, PTSD, homelessness, moral injury), with particular attention to veterans. Manuscripts highlight the strengths of collaborations, including those between specialized research centers and national VA operational partners. Analyses highlight the VA research approach, leveraging data and perspectives from inside and outside the VA, and studying new and established approaches to care. This issue highlights the distinct advantages that VA research provides: experts with the tools, experience, and dedication to addressing the unique needs of veterans. Given the passion for veteran care among VA researchers, including those featured in this issue, we strongly believe the VA will continue to be a leader in this research.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mission is defined by President Abraham Lincoln’s promise “to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan.” Critically, the biopsychosocial needs of veterans differ from the needs of civilians due to the nature of military service.1 Veterans commonly experience traumatic brain injury (TBI) due to combat- or training-related injuries.2 Psychologically, veterans are disproportionately likely to be diagnosed with mental health conditions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), often linked to military exposures.3 Spiritually, veterans frequently express moral injury after living through circumstances when they perpetrate, fail to prevent, or witness events that contradict moral beliefs/ expectations.4 Veterans also have significant social challenges, including high rates of homelessness. 5 A critical strength of the VA mission is its awareness of these complex sequelae and its ability to provide well-informed treatment and social services to meet veterans’ unique needs.

Foundational to a well-informed health care system is a robust research and operational quality improvement infrastructure. The VA Office of Research and Development (ORD) has worked tirelessly to understand and address the unique, idiographic needs of veterans. In 2024 the ORD had a budget of $2.4 billion, excluding quality improvement initiatives enhancing VA operations.6