User login

Simulator Tops Standard Training for Laparoscopic Hernia Repair

BOCA RATON, FLA. – A novel simulation-based training curriculum in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy for general surgery residents led to shorter operating times, better trainee performance, and fewer patient complications in a randomized clinical trial.

The training program has two elements: a cognitive component featuring Web-based PowerPoint presentations and videos along with assigned readings, and psychomotor training on a totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy (TEP) simulator, Dr. Benjamin Zendejas said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

A key feature is that the skills training – with one instructor per resident – is performed until mastery is attained, however long that takes. Only then does the resident start performing TEPs in the operating room under supervision, explained Dr. Zendejas of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He presented a study in which 50 general surgery residents performed a baseline TEP in the operating room, and then were randomized to the simulation-based training program or standard training.

The simulator was the Limbs & Things Ltd.’s TEP Guildford MATTU Hernia Trainer. Mastery was defined by the average 2 minutes required for five experienced instructors to perform a TEP on the simulator. An average of roughly eight attempts was required for fifth-year residents to achieve mastery on the simulator, compared with 26 for first-year residents.

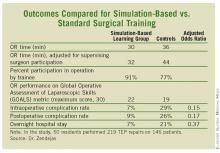

In the operating room, the 50 residents performed 219 TEP repairs on 146 patients. Each repair was evaluated immediately afterward by two independent raters. The simulation-based training group outperformed residents who were trained in the standard fashion in all outcome measures, including the key end point of operative time adjusted for the impact of supervising surgeon takeover for poorly performing trainees. (See box.)

Intraoperative complications, such as peritoneal tears and procedure conversions, occurred in 7% of procedures performed by simulation-trained residents, and in 29% of controls. Urinary retention, seroma, and other postoperative complications resulted from 9% of the simulation-trained residents’ operations, compared with 26% of those performed by residents trained in TEP in standard fashion. In all, 7% of procedures carried out by simulation-trained residents led to an overnight hospital stay, compared with 21% for controls.

"This will become a seminal paper in simulation-based training education," said discussant Dr. Gary L. Dunnington, who called the study "outstanding."

This work suggests that, on an hour-by-hour basis, training in a psychomotor skills laboratory may be more efficient for residents than time spent in the operating room. These data, "if further substantiated, will be of great value with the increasing constraints of decreasing duty hours," noted Dr. Dunnington, professor and chairman of the department of surgery at Southern Illinois University, Springfield.

He was impressed with the investigators’ documentation of improved clinically relevant patient outcomes in the operating room after simulation-based training – the first study to do so. He also liked the investigators’ use of video recordings rather than crude recall to facilitate the study of operative errors.

"This study sets a new bar for simulation researchers," he concluded.

Dr. Zendejas reported having no financial conflicts.

BOCA RATON, FLA. – A novel simulation-based training curriculum in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy for general surgery residents led to shorter operating times, better trainee performance, and fewer patient complications in a randomized clinical trial.

The training program has two elements: a cognitive component featuring Web-based PowerPoint presentations and videos along with assigned readings, and psychomotor training on a totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy (TEP) simulator, Dr. Benjamin Zendejas said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

A key feature is that the skills training – with one instructor per resident – is performed until mastery is attained, however long that takes. Only then does the resident start performing TEPs in the operating room under supervision, explained Dr. Zendejas of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He presented a study in which 50 general surgery residents performed a baseline TEP in the operating room, and then were randomized to the simulation-based training program or standard training.

The simulator was the Limbs & Things Ltd.’s TEP Guildford MATTU Hernia Trainer. Mastery was defined by the average 2 minutes required for five experienced instructors to perform a TEP on the simulator. An average of roughly eight attempts was required for fifth-year residents to achieve mastery on the simulator, compared with 26 for first-year residents.

In the operating room, the 50 residents performed 219 TEP repairs on 146 patients. Each repair was evaluated immediately afterward by two independent raters. The simulation-based training group outperformed residents who were trained in the standard fashion in all outcome measures, including the key end point of operative time adjusted for the impact of supervising surgeon takeover for poorly performing trainees. (See box.)

Intraoperative complications, such as peritoneal tears and procedure conversions, occurred in 7% of procedures performed by simulation-trained residents, and in 29% of controls. Urinary retention, seroma, and other postoperative complications resulted from 9% of the simulation-trained residents’ operations, compared with 26% of those performed by residents trained in TEP in standard fashion. In all, 7% of procedures carried out by simulation-trained residents led to an overnight hospital stay, compared with 21% for controls.

"This will become a seminal paper in simulation-based training education," said discussant Dr. Gary L. Dunnington, who called the study "outstanding."

This work suggests that, on an hour-by-hour basis, training in a psychomotor skills laboratory may be more efficient for residents than time spent in the operating room. These data, "if further substantiated, will be of great value with the increasing constraints of decreasing duty hours," noted Dr. Dunnington, professor and chairman of the department of surgery at Southern Illinois University, Springfield.

He was impressed with the investigators’ documentation of improved clinically relevant patient outcomes in the operating room after simulation-based training – the first study to do so. He also liked the investigators’ use of video recordings rather than crude recall to facilitate the study of operative errors.

"This study sets a new bar for simulation researchers," he concluded.

Dr. Zendejas reported having no financial conflicts.

BOCA RATON, FLA. – A novel simulation-based training curriculum in laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy for general surgery residents led to shorter operating times, better trainee performance, and fewer patient complications in a randomized clinical trial.

The training program has two elements: a cognitive component featuring Web-based PowerPoint presentations and videos along with assigned readings, and psychomotor training on a totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy (TEP) simulator, Dr. Benjamin Zendejas said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

A key feature is that the skills training – with one instructor per resident – is performed until mastery is attained, however long that takes. Only then does the resident start performing TEPs in the operating room under supervision, explained Dr. Zendejas of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

He presented a study in which 50 general surgery residents performed a baseline TEP in the operating room, and then were randomized to the simulation-based training program or standard training.

The simulator was the Limbs & Things Ltd.’s TEP Guildford MATTU Hernia Trainer. Mastery was defined by the average 2 minutes required for five experienced instructors to perform a TEP on the simulator. An average of roughly eight attempts was required for fifth-year residents to achieve mastery on the simulator, compared with 26 for first-year residents.

In the operating room, the 50 residents performed 219 TEP repairs on 146 patients. Each repair was evaluated immediately afterward by two independent raters. The simulation-based training group outperformed residents who were trained in the standard fashion in all outcome measures, including the key end point of operative time adjusted for the impact of supervising surgeon takeover for poorly performing trainees. (See box.)

Intraoperative complications, such as peritoneal tears and procedure conversions, occurred in 7% of procedures performed by simulation-trained residents, and in 29% of controls. Urinary retention, seroma, and other postoperative complications resulted from 9% of the simulation-trained residents’ operations, compared with 26% of those performed by residents trained in TEP in standard fashion. In all, 7% of procedures carried out by simulation-trained residents led to an overnight hospital stay, compared with 21% for controls.

"This will become a seminal paper in simulation-based training education," said discussant Dr. Gary L. Dunnington, who called the study "outstanding."

This work suggests that, on an hour-by-hour basis, training in a psychomotor skills laboratory may be more efficient for residents than time spent in the operating room. These data, "if further substantiated, will be of great value with the increasing constraints of decreasing duty hours," noted Dr. Dunnington, professor and chairman of the department of surgery at Southern Illinois University, Springfield.

He was impressed with the investigators’ documentation of improved clinically relevant patient outcomes in the operating room after simulation-based training – the first study to do so. He also liked the investigators’ use of video recordings rather than crude recall to facilitate the study of operative errors.

"This study sets a new bar for simulation researchers," he concluded.

Dr. Zendejas reported having no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: General surgery residents who learned laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal herniorrhaphy through a novel simulation-based training program significantly outperformed those trained in standard fashion.

Data Source: Randomized trial with 50 residents.

Disclosures: Dr. Zendejas reported having no financial conflicts.

2011 Kidney Donor Death Highlights Lingering Clip Ligation Problem

PHILADELPHIA – At least five live-kidney donors died worldwide since 2005 from catastrophic hemorrhages attributable to insecure ligation of their renal artery by a locking clip rather than by transfixion.

The most recent of these deaths occurred earlier this year, despite concerns raised during 2004-2006 about the safety of clip ligations and a Food and Drug Administration temporary ban in 2006 on the U.S. sale of polymer locking clips, Dr. Amy L. Friedman said at the American Transplant Congress. Following reintroduction of the polymer locking clips in late 2006, two other deaths attributable to severe renal artery hemorrhages in live kidney donors occurred in 2008, said Dr. Friedman, professor of surgery and director of transplants at Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y.

"It’s clear that this is not a frequent event, but even though it’s infrequent it is catastrophic," Dr. Friedman said in an interview. The relative infrequency "does not justify it. We ask surgeons to please respect the privilege of operating on a living kidney donor and not use" a polymer clip to close off the donor’s severed renal artery. Dr. Friedman also noted several other cases since 2003 where patients did not die but had severe hemorrhages because of unreliable artery ligations that produced near-death events.

Dr, Friedman admitted that alternative closure techniques that use transfixion are "challenging." The options are suture ligature, oversewing, or stapling. The most commonly used, safe closure is stapling, which has the drawback of using more of an artery’s length. "If the patient has early branching" of their renal artery, this closure may produce two small arteries instead of one larger one" on the removed kidney, "forcing you to sew them together and making the kidney harder to transplant." But any added inconvenience in transplanting the donated kidney does not outweigh safely closing the donor’s artery, she said. "The stapler is the best alternative to the clip," she said.

The surgeons performing nephrectomies for transplantable kidneys from living donors most commonly are transplant surgeons, urologists, and minimally-invasive surgeons. "There has been extensive pushback" arguing in favor of continued clip use in the urology literature, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting cosponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"The urology community uses clips more frequently, especially for nephrectomies done for other purposes," she said. "In those cases, the length of renal artery that they leave is much longer," experience that seems to have convinced urologists that clipping is safe even when the renal artery is shorter. "What we clearly know is that when the artery stump is left very short to allow a long length of artery to remain with the kidney, clips cannot be used." Some clip proponents also note that clips are less expensive than staples are, and many surgeons also cite personal experience performing hundreds of uneventful renal-artery closures with clips. Dr. Friedman contends that this is not surprising since the severe adverse event rate from clips is very low, but even a handful of deaths is too many.

Many transplant surgeons remain skeptical of the risk because they want to see case reports from deaths and other severe sequelae, data that the FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have generally not shared.

Dr. Friedman contended that these regulatory agencies have balked at releasing case details out of medicolegal concerns about discoverability and confidentiality.

These agencies "make it hard, but these data should be easily available. If surgeons knew that there have been at least five deaths since 2005, it’s hard to imagine that they would not be convinced. I’m doing my best to get the information out," she said.

The five deaths from unstable renal artery closures in kidney donors using locking polymer clips comprised two cases in 2005, two in 2008, and the most recent case reported by UNOS earlier this year. Dr. Friedman said that she had also reviewed a report of a possible sixth death in February 2005, but it remains unclear whether this was the same case as one of the other 2005 deaths she cited. In addition, Dr. Friedman said she was aware of five additional cases of severe hemorrhage complications in living kidney donors treated with polymer clips since 2005.

Following notification by UNOS of the most recent death in February of this year, and a reminder to transplant surgeons not to use polymer clips for artery ligations, Dr. Friedman sent out an electronic survey in March to the members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS). From the 1,095 members she received 217 replies (20%). In reply to a question whether the ASTS members had received the UNOS notification, about two-thirds said they had not. She also asked the ASTS members whether their institutions continued to use hemostatic clips to ligate the renal arteries of live kidney donors. About 20% of all 201 respondents to this question, and more than 10% of the U.S.-based surgeons who responded said that their institutions used clips at least sometimes for these ligations.

Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – At least five live-kidney donors died worldwide since 2005 from catastrophic hemorrhages attributable to insecure ligation of their renal artery by a locking clip rather than by transfixion.

The most recent of these deaths occurred earlier this year, despite concerns raised during 2004-2006 about the safety of clip ligations and a Food and Drug Administration temporary ban in 2006 on the U.S. sale of polymer locking clips, Dr. Amy L. Friedman said at the American Transplant Congress. Following reintroduction of the polymer locking clips in late 2006, two other deaths attributable to severe renal artery hemorrhages in live kidney donors occurred in 2008, said Dr. Friedman, professor of surgery and director of transplants at Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y.

"It’s clear that this is not a frequent event, but even though it’s infrequent it is catastrophic," Dr. Friedman said in an interview. The relative infrequency "does not justify it. We ask surgeons to please respect the privilege of operating on a living kidney donor and not use" a polymer clip to close off the donor’s severed renal artery. Dr. Friedman also noted several other cases since 2003 where patients did not die but had severe hemorrhages because of unreliable artery ligations that produced near-death events.

Dr, Friedman admitted that alternative closure techniques that use transfixion are "challenging." The options are suture ligature, oversewing, or stapling. The most commonly used, safe closure is stapling, which has the drawback of using more of an artery’s length. "If the patient has early branching" of their renal artery, this closure may produce two small arteries instead of one larger one" on the removed kidney, "forcing you to sew them together and making the kidney harder to transplant." But any added inconvenience in transplanting the donated kidney does not outweigh safely closing the donor’s artery, she said. "The stapler is the best alternative to the clip," she said.

The surgeons performing nephrectomies for transplantable kidneys from living donors most commonly are transplant surgeons, urologists, and minimally-invasive surgeons. "There has been extensive pushback" arguing in favor of continued clip use in the urology literature, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting cosponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"The urology community uses clips more frequently, especially for nephrectomies done for other purposes," she said. "In those cases, the length of renal artery that they leave is much longer," experience that seems to have convinced urologists that clipping is safe even when the renal artery is shorter. "What we clearly know is that when the artery stump is left very short to allow a long length of artery to remain with the kidney, clips cannot be used." Some clip proponents also note that clips are less expensive than staples are, and many surgeons also cite personal experience performing hundreds of uneventful renal-artery closures with clips. Dr. Friedman contends that this is not surprising since the severe adverse event rate from clips is very low, but even a handful of deaths is too many.

Many transplant surgeons remain skeptical of the risk because they want to see case reports from deaths and other severe sequelae, data that the FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have generally not shared.

Dr. Friedman contended that these regulatory agencies have balked at releasing case details out of medicolegal concerns about discoverability and confidentiality.

These agencies "make it hard, but these data should be easily available. If surgeons knew that there have been at least five deaths since 2005, it’s hard to imagine that they would not be convinced. I’m doing my best to get the information out," she said.

The five deaths from unstable renal artery closures in kidney donors using locking polymer clips comprised two cases in 2005, two in 2008, and the most recent case reported by UNOS earlier this year. Dr. Friedman said that she had also reviewed a report of a possible sixth death in February 2005, but it remains unclear whether this was the same case as one of the other 2005 deaths she cited. In addition, Dr. Friedman said she was aware of five additional cases of severe hemorrhage complications in living kidney donors treated with polymer clips since 2005.

Following notification by UNOS of the most recent death in February of this year, and a reminder to transplant surgeons not to use polymer clips for artery ligations, Dr. Friedman sent out an electronic survey in March to the members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS). From the 1,095 members she received 217 replies (20%). In reply to a question whether the ASTS members had received the UNOS notification, about two-thirds said they had not. She also asked the ASTS members whether their institutions continued to use hemostatic clips to ligate the renal arteries of live kidney donors. About 20% of all 201 respondents to this question, and more than 10% of the U.S.-based surgeons who responded said that their institutions used clips at least sometimes for these ligations.

Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – At least five live-kidney donors died worldwide since 2005 from catastrophic hemorrhages attributable to insecure ligation of their renal artery by a locking clip rather than by transfixion.

The most recent of these deaths occurred earlier this year, despite concerns raised during 2004-2006 about the safety of clip ligations and a Food and Drug Administration temporary ban in 2006 on the U.S. sale of polymer locking clips, Dr. Amy L. Friedman said at the American Transplant Congress. Following reintroduction of the polymer locking clips in late 2006, two other deaths attributable to severe renal artery hemorrhages in live kidney donors occurred in 2008, said Dr. Friedman, professor of surgery and director of transplants at Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y.

"It’s clear that this is not a frequent event, but even though it’s infrequent it is catastrophic," Dr. Friedman said in an interview. The relative infrequency "does not justify it. We ask surgeons to please respect the privilege of operating on a living kidney donor and not use" a polymer clip to close off the donor’s severed renal artery. Dr. Friedman also noted several other cases since 2003 where patients did not die but had severe hemorrhages because of unreliable artery ligations that produced near-death events.

Dr, Friedman admitted that alternative closure techniques that use transfixion are "challenging." The options are suture ligature, oversewing, or stapling. The most commonly used, safe closure is stapling, which has the drawback of using more of an artery’s length. "If the patient has early branching" of their renal artery, this closure may produce two small arteries instead of one larger one" on the removed kidney, "forcing you to sew them together and making the kidney harder to transplant." But any added inconvenience in transplanting the donated kidney does not outweigh safely closing the donor’s artery, she said. "The stapler is the best alternative to the clip," she said.

The surgeons performing nephrectomies for transplantable kidneys from living donors most commonly are transplant surgeons, urologists, and minimally-invasive surgeons. "There has been extensive pushback" arguing in favor of continued clip use in the urology literature, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting cosponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"The urology community uses clips more frequently, especially for nephrectomies done for other purposes," she said. "In those cases, the length of renal artery that they leave is much longer," experience that seems to have convinced urologists that clipping is safe even when the renal artery is shorter. "What we clearly know is that when the artery stump is left very short to allow a long length of artery to remain with the kidney, clips cannot be used." Some clip proponents also note that clips are less expensive than staples are, and many surgeons also cite personal experience performing hundreds of uneventful renal-artery closures with clips. Dr. Friedman contends that this is not surprising since the severe adverse event rate from clips is very low, but even a handful of deaths is too many.

Many transplant surgeons remain skeptical of the risk because they want to see case reports from deaths and other severe sequelae, data that the FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have generally not shared.

Dr. Friedman contended that these regulatory agencies have balked at releasing case details out of medicolegal concerns about discoverability and confidentiality.

These agencies "make it hard, but these data should be easily available. If surgeons knew that there have been at least five deaths since 2005, it’s hard to imagine that they would not be convinced. I’m doing my best to get the information out," she said.

The five deaths from unstable renal artery closures in kidney donors using locking polymer clips comprised two cases in 2005, two in 2008, and the most recent case reported by UNOS earlier this year. Dr. Friedman said that she had also reviewed a report of a possible sixth death in February 2005, but it remains unclear whether this was the same case as one of the other 2005 deaths she cited. In addition, Dr. Friedman said she was aware of five additional cases of severe hemorrhage complications in living kidney donors treated with polymer clips since 2005.

Following notification by UNOS of the most recent death in February of this year, and a reminder to transplant surgeons not to use polymer clips for artery ligations, Dr. Friedman sent out an electronic survey in March to the members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS). From the 1,095 members she received 217 replies (20%). In reply to a question whether the ASTS members had received the UNOS notification, about two-thirds said they had not. She also asked the ASTS members whether their institutions continued to use hemostatic clips to ligate the renal arteries of live kidney donors. About 20% of all 201 respondents to this question, and more than 10% of the U.S.-based surgeons who responded said that their institutions used clips at least sometimes for these ligations.

Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN TRANSPLANT CONGRESS

Major Finding: Since 2005, at least five living kidney donors died from severe hemorrhages secondary to the use of polymer clips for ligating their renal arteries following nephrectomy. One case occurred in early 2011.

Data Source: Review of documented cases.

Disclosures: Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

2011 Kidney Donor Death Highlights Lingering Clip Ligation Problem

PHILADELPHIA – At least five live-kidney donors died worldwide since 2005 from catastrophic hemorrhages attributable to insecure ligation of their renal artery by a locking clip rather than by transfixion.

The most recent of these deaths occurred earlier this year, despite concerns raised during 2004-2006 about the safety of clip ligations and a Food and Drug Administration temporary ban in 2006 on the U.S. sale of polymer locking clips, Dr. Amy L. Friedman said at the American Transplant Congress. Following reintroduction of the polymer locking clips in late 2006, two other deaths attributable to severe renal artery hemorrhages in live kidney donors occurred in 2008, said Dr. Friedman, professor of surgery and director of transplants at Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y.

"It’s clear that this is not a frequent event, but even though it’s infrequent it is catastrophic," Dr. Friedman said in an interview. The relative infrequency "does not justify it. We ask surgeons to please respect the privilege of operating on a living kidney donor and not use" a polymer clip to close off the donor’s severed renal artery. Dr. Friedman also noted several other cases since 2003 where patients did not die but had severe hemorrhages because of unreliable artery ligations that produced near-death events.

Dr, Friedman admitted that alternative closure techniques that use transfixion are "challenging." The options are suture ligature, oversewing, or stapling. The most commonly used, safe closure is stapling, which has the drawback of using more of an artery’s length. "If the patient has early branching" of their renal artery, this closure may produce two small arteries instead of one larger one" on the removed kidney, "forcing you to sew them together and making the kidney harder to transplant." But any added inconvenience in transplanting the donated kidney does not outweigh safely closing the donor’s artery, she said. "The stapler is the best alternative to the clip," she said.

The surgeons performing nephrectomies for transplantable kidneys from living donors most commonly are transplant surgeons, urologists, and minimally-invasive surgeons. "There has been extensive pushback" arguing in favor of continued clip use in the urology literature, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting cosponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"The urology community uses clips more frequently, especially for nephrectomies done for other purposes," she said. "In those cases, the length of renal artery that they leave is much longer," experience that seems to have convinced urologists that clipping is safe even when the renal artery is shorter. "What we clearly know is that when the artery stump is left very short to allow a long length of artery to remain with the kidney, clips cannot be used." Some clip proponents also note that clips are less expensive than staples are, and many surgeons also cite personal experience performing hundreds of uneventful renal-artery closures with clips. Dr. Friedman contends that this is not surprising since the severe adverse event rate from clips is very low, but even a handful of deaths is too many.

Many transplant surgeons remain skeptical of the risk because they want to see case reports from deaths and other severe sequelae, data that the FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have generally not shared.

Dr. Friedman contended that these regulatory agencies have balked at releasing case details out of medicolegal concerns about discoverability and confidentiality.

These agencies "make it hard, but these data should be easily available. If surgeons knew that there have been at least five deaths since 2005, it’s hard to imagine that they would not be convinced. I’m doing my best to get the information out," she said.

The five deaths from unstable renal artery closures in kidney donors using locking polymer clips comprised two cases in 2005, two in 2008, and the most recent case reported by UNOS earlier this year. Dr. Friedman said that she had also reviewed a report of a possible sixth death in February 2005, but it remains unclear whether this was the same case as one of the other 2005 deaths she cited. In addition, Dr. Friedman said she was aware of five additional cases of severe hemorrhage complications in living kidney donors treated with polymer clips since 2005.

Following notification by UNOS of the most recent death in February of this year, and a reminder to transplant surgeons not to use polymer clips for artery ligations, Dr. Friedman sent out an electronic survey in March to the members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS). From the 1,095 members she received 217 replies (20%). In reply to a question whether the ASTS members had received the UNOS notification, about two-thirds said they had not. She also asked the ASTS members whether their institutions continued to use hemostatic clips to ligate the renal arteries of live kidney donors. About 20% of all 201 respondents to this question, and more than 10% of the U.S.-based surgeons who responded said that their institutions used clips at least sometimes for these ligations.

Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – At least five live-kidney donors died worldwide since 2005 from catastrophic hemorrhages attributable to insecure ligation of their renal artery by a locking clip rather than by transfixion.

The most recent of these deaths occurred earlier this year, despite concerns raised during 2004-2006 about the safety of clip ligations and a Food and Drug Administration temporary ban in 2006 on the U.S. sale of polymer locking clips, Dr. Amy L. Friedman said at the American Transplant Congress. Following reintroduction of the polymer locking clips in late 2006, two other deaths attributable to severe renal artery hemorrhages in live kidney donors occurred in 2008, said Dr. Friedman, professor of surgery and director of transplants at Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y.

"It’s clear that this is not a frequent event, but even though it’s infrequent it is catastrophic," Dr. Friedman said in an interview. The relative infrequency "does not justify it. We ask surgeons to please respect the privilege of operating on a living kidney donor and not use" a polymer clip to close off the donor’s severed renal artery. Dr. Friedman also noted several other cases since 2003 where patients did not die but had severe hemorrhages because of unreliable artery ligations that produced near-death events.

Dr, Friedman admitted that alternative closure techniques that use transfixion are "challenging." The options are suture ligature, oversewing, or stapling. The most commonly used, safe closure is stapling, which has the drawback of using more of an artery’s length. "If the patient has early branching" of their renal artery, this closure may produce two small arteries instead of one larger one" on the removed kidney, "forcing you to sew them together and making the kidney harder to transplant." But any added inconvenience in transplanting the donated kidney does not outweigh safely closing the donor’s artery, she said. "The stapler is the best alternative to the clip," she said.

The surgeons performing nephrectomies for transplantable kidneys from living donors most commonly are transplant surgeons, urologists, and minimally-invasive surgeons. "There has been extensive pushback" arguing in favor of continued clip use in the urology literature, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting cosponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"The urology community uses clips more frequently, especially for nephrectomies done for other purposes," she said. "In those cases, the length of renal artery that they leave is much longer," experience that seems to have convinced urologists that clipping is safe even when the renal artery is shorter. "What we clearly know is that when the artery stump is left very short to allow a long length of artery to remain with the kidney, clips cannot be used." Some clip proponents also note that clips are less expensive than staples are, and many surgeons also cite personal experience performing hundreds of uneventful renal-artery closures with clips. Dr. Friedman contends that this is not surprising since the severe adverse event rate from clips is very low, but even a handful of deaths is too many.

Many transplant surgeons remain skeptical of the risk because they want to see case reports from deaths and other severe sequelae, data that the FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have generally not shared.

Dr. Friedman contended that these regulatory agencies have balked at releasing case details out of medicolegal concerns about discoverability and confidentiality.

These agencies "make it hard, but these data should be easily available. If surgeons knew that there have been at least five deaths since 2005, it’s hard to imagine that they would not be convinced. I’m doing my best to get the information out," she said.

The five deaths from unstable renal artery closures in kidney donors using locking polymer clips comprised two cases in 2005, two in 2008, and the most recent case reported by UNOS earlier this year. Dr. Friedman said that she had also reviewed a report of a possible sixth death in February 2005, but it remains unclear whether this was the same case as one of the other 2005 deaths she cited. In addition, Dr. Friedman said she was aware of five additional cases of severe hemorrhage complications in living kidney donors treated with polymer clips since 2005.

Following notification by UNOS of the most recent death in February of this year, and a reminder to transplant surgeons not to use polymer clips for artery ligations, Dr. Friedman sent out an electronic survey in March to the members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS). From the 1,095 members she received 217 replies (20%). In reply to a question whether the ASTS members had received the UNOS notification, about two-thirds said they had not. She also asked the ASTS members whether their institutions continued to use hemostatic clips to ligate the renal arteries of live kidney donors. About 20% of all 201 respondents to this question, and more than 10% of the U.S.-based surgeons who responded said that their institutions used clips at least sometimes for these ligations.

Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – At least five live-kidney donors died worldwide since 2005 from catastrophic hemorrhages attributable to insecure ligation of their renal artery by a locking clip rather than by transfixion.

The most recent of these deaths occurred earlier this year, despite concerns raised during 2004-2006 about the safety of clip ligations and a Food and Drug Administration temporary ban in 2006 on the U.S. sale of polymer locking clips, Dr. Amy L. Friedman said at the American Transplant Congress. Following reintroduction of the polymer locking clips in late 2006, two other deaths attributable to severe renal artery hemorrhages in live kidney donors occurred in 2008, said Dr. Friedman, professor of surgery and director of transplants at Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y.

"It’s clear that this is not a frequent event, but even though it’s infrequent it is catastrophic," Dr. Friedman said in an interview. The relative infrequency "does not justify it. We ask surgeons to please respect the privilege of operating on a living kidney donor and not use" a polymer clip to close off the donor’s severed renal artery. Dr. Friedman also noted several other cases since 2003 where patients did not die but had severe hemorrhages because of unreliable artery ligations that produced near-death events.

Dr, Friedman admitted that alternative closure techniques that use transfixion are "challenging." The options are suture ligature, oversewing, or stapling. The most commonly used, safe closure is stapling, which has the drawback of using more of an artery’s length. "If the patient has early branching" of their renal artery, this closure may produce two small arteries instead of one larger one" on the removed kidney, "forcing you to sew them together and making the kidney harder to transplant." But any added inconvenience in transplanting the donated kidney does not outweigh safely closing the donor’s artery, she said. "The stapler is the best alternative to the clip," she said.

The surgeons performing nephrectomies for transplantable kidneys from living donors most commonly are transplant surgeons, urologists, and minimally-invasive surgeons. "There has been extensive pushback" arguing in favor of continued clip use in the urology literature, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting cosponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"The urology community uses clips more frequently, especially for nephrectomies done for other purposes," she said. "In those cases, the length of renal artery that they leave is much longer," experience that seems to have convinced urologists that clipping is safe even when the renal artery is shorter. "What we clearly know is that when the artery stump is left very short to allow a long length of artery to remain with the kidney, clips cannot be used." Some clip proponents also note that clips are less expensive than staples are, and many surgeons also cite personal experience performing hundreds of uneventful renal-artery closures with clips. Dr. Friedman contends that this is not surprising since the severe adverse event rate from clips is very low, but even a handful of deaths is too many.

Many transplant surgeons remain skeptical of the risk because they want to see case reports from deaths and other severe sequelae, data that the FDA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have generally not shared.

Dr. Friedman contended that these regulatory agencies have balked at releasing case details out of medicolegal concerns about discoverability and confidentiality.

These agencies "make it hard, but these data should be easily available. If surgeons knew that there have been at least five deaths since 2005, it’s hard to imagine that they would not be convinced. I’m doing my best to get the information out," she said.

The five deaths from unstable renal artery closures in kidney donors using locking polymer clips comprised two cases in 2005, two in 2008, and the most recent case reported by UNOS earlier this year. Dr. Friedman said that she had also reviewed a report of a possible sixth death in February 2005, but it remains unclear whether this was the same case as one of the other 2005 deaths she cited. In addition, Dr. Friedman said she was aware of five additional cases of severe hemorrhage complications in living kidney donors treated with polymer clips since 2005.

Following notification by UNOS of the most recent death in February of this year, and a reminder to transplant surgeons not to use polymer clips for artery ligations, Dr. Friedman sent out an electronic survey in March to the members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS). From the 1,095 members she received 217 replies (20%). In reply to a question whether the ASTS members had received the UNOS notification, about two-thirds said they had not. She also asked the ASTS members whether their institutions continued to use hemostatic clips to ligate the renal arteries of live kidney donors. About 20% of all 201 respondents to this question, and more than 10% of the U.S.-based surgeons who responded said that their institutions used clips at least sometimes for these ligations.

Dr. Friedman said that she and her associates have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN TRANSPLANT CONGRESS

Using Renal Disease to Predict Cardiovascular Risk

New Methods Found Promising for Predicting CKD Progression

Separate research groups offer two new methods for predicting which patients with chronic kidney disease are likely to progress to end-stage renal disease and other complications, according to studies published in the April 20 issue of JAMA.

Ultimately, the methods could help more accurately identify individuals who are at low and high risk for CKD progression, and allow for more appropriate use of health care resources for this population.

In the first report, a "triple-marker" approach using serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, and albuminuria levels yielded more accurate risk prediction than is achieved with current staging systems that are based primarily on creatinine-estimated glomerular filtration rates, said Dr. Carmen A. Peralta of the San Francisco VA Medical Center and her associates.

They assessed the triple-marker technique using a large, population-based cohort of adults (aged 45 years and older) who were participating in a stroke study. A subgroup of 26,643 of these subjects had undergone evaluation of kidney function as part of that study.

Patients in Dr. Peralta’s analysis had a mean age of 65 years. In all, 40% were black, more than half were women, 21% had diabetes, and 59% had hypertension. During a median follow-up of approximately 5 years, 177 subjects developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and 1,940 died of all causes.

Adding either the cystatin C or the albuminuria measures to creatinine-based estimated GFR greatly improved the ability to predict the development of ESRD as well as mortality. Using all three measures together improved it even further.

The rate of ESRD was 103-fold higher in subjects who were identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those who were identified via creatinine level alone. Similarly, mortality was nearly eight times higher among those identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those identified via creatinine level alone, the investigators said (JAMA 2011;305:1545-52).

Moreover, one in six subjects who were found to have CKD by the triple-marker method were not identified at all by creatinine level alone, suggesting that people could have occult CKD that would not be diagnosed according to standard methods.

In addition, 25% of subjects who were labeled as having CKD by creatinine-based GFR estimate alone were found not to have CKD when cystatin C and albuminuria levels were added into the risk stratification. This suggests that one-fourth of people screened by standard methods alone may be treated as though they’re at increased risk of ESRD or death when they are not.

Thus, using the triple-marker method "could both reduce unwarranted referrals and unnecessary work-ups for low-risk individuals and would prioritize specialty care and interventions to individuals at highest risk," Dr. Peralta and her colleagues said.

"Several groups are currently advocating new international guidelines that more accurately reflect prognosis of CKD and have proposed adding [albumin:creatinine ratio] to staging of CKD. Our results suggest that a triple-marker approach using both [albuminuria] and cystatin C to confirm CKD more accurately discriminates prognosis for death and progression to ESRD than creatinine and [albuminuria] alone," they added.

In the second report, investigators developed seven possible models for predicting CKD progression, using various combinations of more than 20 candidate variables that are known to affect renal function. To do so, they first assessed these variables in a Canadian cohort of 3,449 adults who were treated at nephrology clinics for stage 3-5 CKD.

These study subjects, who were followed from 2001 through 2008, helped determine which variables were best associated with CKD progression, said Dr. Navdeep Tangri of Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

One of the seven models was particularly accurate at predicting CKD progression. It factored in patient age and sex, as well as the estimated GFR, albuminuria, serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum bicarbonate, and serum albumin levels. These are basic laboratory measurements "that are obtained routinely in patients with CKD," Dr. Tangri and his colleagues said (JAMA 2011;305:1553-9).

All seven models were tested in a validation cohort of 4,942 patients in a British Columbia registry who had stage 3-5 CKD. The same model was found to be the most accurate in predicting disease progression in that cohort.

"Using our models, lower-risk patients could be managed by the primary care physician without additional testing or treatment of CKD complications," whereas higher-risk patients could receive "more intensive testing, intervention, and early nephrology care," they said.

The models also could be used to triage patients with stage 4 CKD "regarding dialysis education, creation of vascular access, and preemptive transplantation"; to select stage 3 patients for public health interventions; and to select high-risk patients for enrollment in clinical trials, the researchers added.

Dr. Peralta’s study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Amgen Corp., the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Several associates also reported ties to Amgen. Dr. Tangri’s study was supported by a joint initiative of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology, as well as by the Change Foundation of Ontario. Dr. Tangri and associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

The findings from both of these studies are "novel and important," but "much additional work is needed before these approaches can be recommended for routine clinical use," said Dr. Marcello Tonelli and Dr. Braden Manns.

Both studies provide proof of concept for two different methods that might enhance prognostic power, compared with the use of creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

However, it would be premature to introduce the triple-marker approach of Dr. Peralta and colleagues into clinical practice for three reasons: First, their study population was highly selected, so the findings cannot be generalized to other settings until further research is done. Second, current practice includes confirmation of estimated GFR with a second measurement to confirm CKD, and this repeat measurement was not addressed in this study. And third, the use of more stringent estimated GFR criteria to define CKD might attenuate the advantage of the triple-marker method.

It also would be premature to implement the prediction model of Dr. Tangri and colleagues because there were missing data in both the cohort used to develop the models and the validation cohort, and values were imputed for subjects who had incomplete information. More importantly, all the study subjects were already in the care of a nephrologist, so they are not representative of the general population.

"Careful consideration and research will be required to determine whether the benefits [of an eight-variable model] would outweigh its added complexity," they concluded.

Dr. Tonelli is at the University of Alberta, Edmonton. Dr. Manns is at the University of Calgary (Alta.). They were supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, by Alberta Health and Wellness, and by the University of Alberta. Dr. Tonelli also is supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal treatment of CKD. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2011:305:1593-5).

The findings from both of these studies are "novel and important," but "much additional work is needed before these approaches can be recommended for routine clinical use," said Dr. Marcello Tonelli and Dr. Braden Manns.

Both studies provide proof of concept for two different methods that might enhance prognostic power, compared with the use of creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

However, it would be premature to introduce the triple-marker approach of Dr. Peralta and colleagues into clinical practice for three reasons: First, their study population was highly selected, so the findings cannot be generalized to other settings until further research is done. Second, current practice includes confirmation of estimated GFR with a second measurement to confirm CKD, and this repeat measurement was not addressed in this study. And third, the use of more stringent estimated GFR criteria to define CKD might attenuate the advantage of the triple-marker method.

It also would be premature to implement the prediction model of Dr. Tangri and colleagues because there were missing data in both the cohort used to develop the models and the validation cohort, and values were imputed for subjects who had incomplete information. More importantly, all the study subjects were already in the care of a nephrologist, so they are not representative of the general population.

"Careful consideration and research will be required to determine whether the benefits [of an eight-variable model] would outweigh its added complexity," they concluded.

Dr. Tonelli is at the University of Alberta, Edmonton. Dr. Manns is at the University of Calgary (Alta.). They were supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, by Alberta Health and Wellness, and by the University of Alberta. Dr. Tonelli also is supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal treatment of CKD. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2011:305:1593-5).

The findings from both of these studies are "novel and important," but "much additional work is needed before these approaches can be recommended for routine clinical use," said Dr. Marcello Tonelli and Dr. Braden Manns.

Both studies provide proof of concept for two different methods that might enhance prognostic power, compared with the use of creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

However, it would be premature to introduce the triple-marker approach of Dr. Peralta and colleagues into clinical practice for three reasons: First, their study population was highly selected, so the findings cannot be generalized to other settings until further research is done. Second, current practice includes confirmation of estimated GFR with a second measurement to confirm CKD, and this repeat measurement was not addressed in this study. And third, the use of more stringent estimated GFR criteria to define CKD might attenuate the advantage of the triple-marker method.

It also would be premature to implement the prediction model of Dr. Tangri and colleagues because there were missing data in both the cohort used to develop the models and the validation cohort, and values were imputed for subjects who had incomplete information. More importantly, all the study subjects were already in the care of a nephrologist, so they are not representative of the general population.

"Careful consideration and research will be required to determine whether the benefits [of an eight-variable model] would outweigh its added complexity," they concluded.

Dr. Tonelli is at the University of Alberta, Edmonton. Dr. Manns is at the University of Calgary (Alta.). They were supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, by Alberta Health and Wellness, and by the University of Alberta. Dr. Tonelli also is supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal treatment of CKD. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2011:305:1593-5).

Separate research groups offer two new methods for predicting which patients with chronic kidney disease are likely to progress to end-stage renal disease and other complications, according to studies published in the April 20 issue of JAMA.

Ultimately, the methods could help more accurately identify individuals who are at low and high risk for CKD progression, and allow for more appropriate use of health care resources for this population.

In the first report, a "triple-marker" approach using serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, and albuminuria levels yielded more accurate risk prediction than is achieved with current staging systems that are based primarily on creatinine-estimated glomerular filtration rates, said Dr. Carmen A. Peralta of the San Francisco VA Medical Center and her associates.

They assessed the triple-marker technique using a large, population-based cohort of adults (aged 45 years and older) who were participating in a stroke study. A subgroup of 26,643 of these subjects had undergone evaluation of kidney function as part of that study.

Patients in Dr. Peralta’s analysis had a mean age of 65 years. In all, 40% were black, more than half were women, 21% had diabetes, and 59% had hypertension. During a median follow-up of approximately 5 years, 177 subjects developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and 1,940 died of all causes.

Adding either the cystatin C or the albuminuria measures to creatinine-based estimated GFR greatly improved the ability to predict the development of ESRD as well as mortality. Using all three measures together improved it even further.

The rate of ESRD was 103-fold higher in subjects who were identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those who were identified via creatinine level alone. Similarly, mortality was nearly eight times higher among those identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those identified via creatinine level alone, the investigators said (JAMA 2011;305:1545-52).

Moreover, one in six subjects who were found to have CKD by the triple-marker method were not identified at all by creatinine level alone, suggesting that people could have occult CKD that would not be diagnosed according to standard methods.

In addition, 25% of subjects who were labeled as having CKD by creatinine-based GFR estimate alone were found not to have CKD when cystatin C and albuminuria levels were added into the risk stratification. This suggests that one-fourth of people screened by standard methods alone may be treated as though they’re at increased risk of ESRD or death when they are not.

Thus, using the triple-marker method "could both reduce unwarranted referrals and unnecessary work-ups for low-risk individuals and would prioritize specialty care and interventions to individuals at highest risk," Dr. Peralta and her colleagues said.

"Several groups are currently advocating new international guidelines that more accurately reflect prognosis of CKD and have proposed adding [albumin:creatinine ratio] to staging of CKD. Our results suggest that a triple-marker approach using both [albuminuria] and cystatin C to confirm CKD more accurately discriminates prognosis for death and progression to ESRD than creatinine and [albuminuria] alone," they added.

In the second report, investigators developed seven possible models for predicting CKD progression, using various combinations of more than 20 candidate variables that are known to affect renal function. To do so, they first assessed these variables in a Canadian cohort of 3,449 adults who were treated at nephrology clinics for stage 3-5 CKD.

These study subjects, who were followed from 2001 through 2008, helped determine which variables were best associated with CKD progression, said Dr. Navdeep Tangri of Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

One of the seven models was particularly accurate at predicting CKD progression. It factored in patient age and sex, as well as the estimated GFR, albuminuria, serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum bicarbonate, and serum albumin levels. These are basic laboratory measurements "that are obtained routinely in patients with CKD," Dr. Tangri and his colleagues said (JAMA 2011;305:1553-9).

All seven models were tested in a validation cohort of 4,942 patients in a British Columbia registry who had stage 3-5 CKD. The same model was found to be the most accurate in predicting disease progression in that cohort.

"Using our models, lower-risk patients could be managed by the primary care physician without additional testing or treatment of CKD complications," whereas higher-risk patients could receive "more intensive testing, intervention, and early nephrology care," they said.

The models also could be used to triage patients with stage 4 CKD "regarding dialysis education, creation of vascular access, and preemptive transplantation"; to select stage 3 patients for public health interventions; and to select high-risk patients for enrollment in clinical trials, the researchers added.

Dr. Peralta’s study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Amgen Corp., the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Several associates also reported ties to Amgen. Dr. Tangri’s study was supported by a joint initiative of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology, as well as by the Change Foundation of Ontario. Dr. Tangri and associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Separate research groups offer two new methods for predicting which patients with chronic kidney disease are likely to progress to end-stage renal disease and other complications, according to studies published in the April 20 issue of JAMA.

Ultimately, the methods could help more accurately identify individuals who are at low and high risk for CKD progression, and allow for more appropriate use of health care resources for this population.

In the first report, a "triple-marker" approach using serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, and albuminuria levels yielded more accurate risk prediction than is achieved with current staging systems that are based primarily on creatinine-estimated glomerular filtration rates, said Dr. Carmen A. Peralta of the San Francisco VA Medical Center and her associates.

They assessed the triple-marker technique using a large, population-based cohort of adults (aged 45 years and older) who were participating in a stroke study. A subgroup of 26,643 of these subjects had undergone evaluation of kidney function as part of that study.

Patients in Dr. Peralta’s analysis had a mean age of 65 years. In all, 40% were black, more than half were women, 21% had diabetes, and 59% had hypertension. During a median follow-up of approximately 5 years, 177 subjects developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and 1,940 died of all causes.

Adding either the cystatin C or the albuminuria measures to creatinine-based estimated GFR greatly improved the ability to predict the development of ESRD as well as mortality. Using all three measures together improved it even further.

The rate of ESRD was 103-fold higher in subjects who were identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those who were identified via creatinine level alone. Similarly, mortality was nearly eight times higher among those identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those identified via creatinine level alone, the investigators said (JAMA 2011;305:1545-52).

Moreover, one in six subjects who were found to have CKD by the triple-marker method were not identified at all by creatinine level alone, suggesting that people could have occult CKD that would not be diagnosed according to standard methods.

In addition, 25% of subjects who were labeled as having CKD by creatinine-based GFR estimate alone were found not to have CKD when cystatin C and albuminuria levels were added into the risk stratification. This suggests that one-fourth of people screened by standard methods alone may be treated as though they’re at increased risk of ESRD or death when they are not.

Thus, using the triple-marker method "could both reduce unwarranted referrals and unnecessary work-ups for low-risk individuals and would prioritize specialty care and interventions to individuals at highest risk," Dr. Peralta and her colleagues said.

"Several groups are currently advocating new international guidelines that more accurately reflect prognosis of CKD and have proposed adding [albumin:creatinine ratio] to staging of CKD. Our results suggest that a triple-marker approach using both [albuminuria] and cystatin C to confirm CKD more accurately discriminates prognosis for death and progression to ESRD than creatinine and [albuminuria] alone," they added.

In the second report, investigators developed seven possible models for predicting CKD progression, using various combinations of more than 20 candidate variables that are known to affect renal function. To do so, they first assessed these variables in a Canadian cohort of 3,449 adults who were treated at nephrology clinics for stage 3-5 CKD.

These study subjects, who were followed from 2001 through 2008, helped determine which variables were best associated with CKD progression, said Dr. Navdeep Tangri of Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

One of the seven models was particularly accurate at predicting CKD progression. It factored in patient age and sex, as well as the estimated GFR, albuminuria, serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum bicarbonate, and serum albumin levels. These are basic laboratory measurements "that are obtained routinely in patients with CKD," Dr. Tangri and his colleagues said (JAMA 2011;305:1553-9).

All seven models were tested in a validation cohort of 4,942 patients in a British Columbia registry who had stage 3-5 CKD. The same model was found to be the most accurate in predicting disease progression in that cohort.

"Using our models, lower-risk patients could be managed by the primary care physician without additional testing or treatment of CKD complications," whereas higher-risk patients could receive "more intensive testing, intervention, and early nephrology care," they said.

The models also could be used to triage patients with stage 4 CKD "regarding dialysis education, creation of vascular access, and preemptive transplantation"; to select stage 3 patients for public health interventions; and to select high-risk patients for enrollment in clinical trials, the researchers added.

Dr. Peralta’s study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Amgen Corp., the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Several associates also reported ties to Amgen. Dr. Tangri’s study was supported by a joint initiative of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology, as well as by the Change Foundation of Ontario. Dr. Tangri and associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA

Major Finding: A triple-marker method incorporating serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, and albuminuria levels predicted CKD progression more accurately than did standard creatinine-estimated GFR alone. Another model incorporating seven patient variables also was more accurate at predicting disease progression than was standard creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

Data Source: The first study was a secondary analysis of a population-based cohort involving 26,643 adults. The second study was an analysis of CKD outcomes following the development and validation of seven models for predicting disease progression in adults with stage 3-5 CKD.

Disclosures: Dr. Peralta’s study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Amgen Corp., the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Several associates also reported ties to Amgen. Dr. Tangri’s study was supported by a joint initiative of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology, as well as by the Change Foundation of Ontario. Dr. Tangri and associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

New Methods Found Promising for Predicting CKD Progression

Separate research groups offer two new methods for predicting which patients with chronic kidney disease are likely to progress to end-stage renal disease and other complications, according to studies published in the April 20 issue of JAMA.

Ultimately, the methods could help more accurately identify individuals who are at low and high risk for CKD progression, and allow for more appropriate use of health care resources for this population.

In the first report, a "triple-marker" approach using serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, and albuminuria levels yielded more accurate risk prediction than is achieved with current staging systems that are based primarily on creatinine-estimated glomerular filtration rates, said Dr. Carmen A. Peralta of the San Francisco VA Medical Center and her associates.

They assessed the triple-marker technique using a large, population-based cohort of adults (aged 45 years and older) who were participating in a stroke study. A subgroup of 26,643 of these subjects had undergone evaluation of kidney function as part of that study.

Patients in Dr. Peralta’s analysis had a mean age of 65 years. In all, 40% were black, more than half were women, 21% had diabetes, and 59% had hypertension. During a median follow-up of approximately 5 years, 177 subjects developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and 1,940 died of all causes.

Adding either the cystatin C or the albuminuria measures to creatinine-based estimated GFR greatly improved the ability to predict the development of ESRD as well as mortality. Using all three measures together improved it even further.

The rate of ESRD was 103-fold higher in subjects who were identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those who were identified via creatinine level alone. Similarly, mortality was nearly eight times higher among those identified as being at risk via the triple-marker method than in those identified via creatinine level alone, the investigators said (JAMA 2011;305:1545-52).

Moreover, one in six subjects who were found to have CKD by the triple-marker method were not identified at all by creatinine level alone, suggesting that people could have occult CKD that would not be diagnosed according to standard methods.

In addition, 25% of subjects who were labeled as having CKD by creatinine-based GFR estimate alone were found not to have CKD when cystatin C and albuminuria levels were added into the risk stratification. This suggests that one-fourth of people screened by standard methods alone may be treated as though they’re at increased risk of ESRD or death when they are not.

Thus, using the triple-marker method "could both reduce unwarranted referrals and unnecessary work-ups for low-risk individuals and would prioritize specialty care and interventions to individuals at highest risk," Dr. Peralta and her colleagues said.

"Several groups are currently advocating new international guidelines that more accurately reflect prognosis of CKD and have proposed adding [albumin:creatinine ratio] to staging of CKD. Our results suggest that a triple-marker approach using both [albuminuria] and cystatin C to confirm CKD more accurately discriminates prognosis for death and progression to ESRD than creatinine and [albuminuria] alone," they added.

In the second report, investigators developed seven possible models for predicting CKD progression, using various combinations of more than 20 candidate variables that are known to affect renal function. To do so, they first assessed these variables in a Canadian cohort of 3,449 adults who were treated at nephrology clinics for stage 3-5 CKD.

These study subjects, who were followed from 2001 through 2008, helped determine which variables were best associated with CKD progression, said Dr. Navdeep Tangri of Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

One of the seven models was particularly accurate at predicting CKD progression. It factored in patient age and sex, as well as the estimated GFR, albuminuria, serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum bicarbonate, and serum albumin levels. These are basic laboratory measurements "that are obtained routinely in patients with CKD," Dr. Tangri and his colleagues said (JAMA 2011;305:1553-9).

All seven models were tested in a validation cohort of 4,942 patients in a British Columbia registry who had stage 3-5 CKD. The same model was found to be the most accurate in predicting disease progression in that cohort.

"Using our models, lower-risk patients could be managed by the primary care physician without additional testing or treatment of CKD complications," whereas higher-risk patients could receive "more intensive testing, intervention, and early nephrology care," they said.

The models also could be used to triage patients with stage 4 CKD "regarding dialysis education, creation of vascular access, and preemptive transplantation"; to select stage 3 patients for public health interventions; and to select high-risk patients for enrollment in clinical trials, the researchers added.

Dr. Peralta’s study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Amgen Corp., the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Several associates also reported ties to Amgen. Dr. Tangri’s study was supported by a joint initiative of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology, as well as by the Change Foundation of Ontario. Dr. Tangri and associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

The findings from both of these studies are "novel and important," but "much additional work is needed before these approaches can be recommended for routine clinical use," said Dr. Marcello Tonelli and Dr. Braden Manns.

Both studies provide proof of concept for two different methods that might enhance prognostic power, compared with the use of creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

However, it would be premature to introduce the triple-marker approach of Dr. Peralta and colleagues into clinical practice for three reasons: First, their study population was highly selected, so the findings cannot be generalized to other settings until further research is done. Second, current practice includes confirmation of estimated GFR with a second measurement to confirm CKD, and this repeat measurement was not addressed in this study. And third, the use of more stringent estimated GFR criteria to define CKD might attenuate the advantage of the triple-marker method.

It also would be premature to implement the prediction model of Dr. Tangri and colleagues because there were missing data in both the cohort used to develop the models and the validation cohort, and values were imputed for subjects who had incomplete information. More importantly, all the study subjects were already in the care of a nephrologist, so they are not representative of the general population.

"Careful consideration and research will be required to determine whether the benefits [of an eight-variable model] would outweigh its added complexity," they concluded.

Dr. Tonelli is at the University of Alberta, Edmonton. Dr. Manns is at the University of Calgary (Alta.). They were supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, by Alberta Health and Wellness, and by the University of Alberta. Dr. Tonelli also is supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal treatment of CKD. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2011:305:1593-5).

The findings from both of these studies are "novel and important," but "much additional work is needed before these approaches can be recommended for routine clinical use," said Dr. Marcello Tonelli and Dr. Braden Manns.

Both studies provide proof of concept for two different methods that might enhance prognostic power, compared with the use of creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

However, it would be premature to introduce the triple-marker approach of Dr. Peralta and colleagues into clinical practice for three reasons: First, their study population was highly selected, so the findings cannot be generalized to other settings until further research is done. Second, current practice includes confirmation of estimated GFR with a second measurement to confirm CKD, and this repeat measurement was not addressed in this study. And third, the use of more stringent estimated GFR criteria to define CKD might attenuate the advantage of the triple-marker method.

It also would be premature to implement the prediction model of Dr. Tangri and colleagues because there were missing data in both the cohort used to develop the models and the validation cohort, and values were imputed for subjects who had incomplete information. More importantly, all the study subjects were already in the care of a nephrologist, so they are not representative of the general population.

"Careful consideration and research will be required to determine whether the benefits [of an eight-variable model] would outweigh its added complexity," they concluded.

Dr. Tonelli is at the University of Alberta, Edmonton. Dr. Manns is at the University of Calgary (Alta.). They were supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, by Alberta Health and Wellness, and by the University of Alberta. Dr. Tonelli also is supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair in the optimal treatment of CKD. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2011:305:1593-5).

The findings from both of these studies are "novel and important," but "much additional work is needed before these approaches can be recommended for routine clinical use," said Dr. Marcello Tonelli and Dr. Braden Manns.

Both studies provide proof of concept for two different methods that might enhance prognostic power, compared with the use of creatinine-estimated GFR alone.

However, it would be premature to introduce the triple-marker approach of Dr. Peralta and colleagues into clinical practice for three reasons: First, their study population was highly selected, so the findings cannot be generalized to other settings until further research is done. Second, current practice includes confirmation of estimated GFR with a second measurement to confirm CKD, and this repeat measurement was not addressed in this study. And third, the use of more stringent estimated GFR criteria to define CKD might attenuate the advantage of the triple-marker method.