User login

Optimal gestational age for cell-free DNA sampling in obese women

cfDNA screening failures occur in 1% to 12% of samples, a rate that has an inverse relationship to gestational age. Recent studies have shown an increased risk for screening failures among obese women. To determine the optimal gestational age for cfDNA testing among obese women, Mary C. Livergood, MD, and colleagues at the Mercy Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, performed a retrospective cohort study of those undergoing cfDNA testing at one center from 2011 through 2016. Study results recently were published online in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1

Details of the study

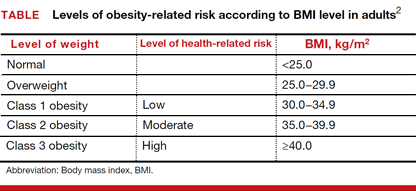

Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for a cfDNA screening failure (referred to as a “no call” in the study) were determined for each body mass index (BMI) weight class (TABLE). Each BMI weight class also was compared with the aOR of normal-weight women (BMI <25.0 kg/m2). The predicted probability of a no call was determined for each week of gestational age for normal weight and obese women and the results were compared.1

Among the 2,385 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 4.4% (n = 105) received a no call. Compared with normal weight women, the aOR of no call increased as weight increased from overweight (aOR, 2.31 [95% CI, 1.21–4.42]) to obesity class III (aOR, 8.55 [95% CI, 4.16–17.56]).1

At 21 weeks’ gestation, a cut-point was identified for obesity class II/III women (ie, there was no longer a significant difference in the probability of no call when compared with normal-weight women). From 8 to 16 weeks’ gestation, there was a 4.5% reduction in the probability of a no call for obesity class II/III women (aOR, 14.9; 95% CI, 8.95–20.78 and aOR, 10.4; 95% CI, 7.20–13.61; Ptrend<.01).1

Although the authors conclude that a cut-point of 21 weeks’ gestation allowed for optimal sampling of cfDNA in obese women, they also acknowledge that this cut-point limits a woman’s reproductive choices. However, they say that delaying cfDNA testing in obese women is a reasonable strategy to reduce the probability of screening failure.1

- Livergood MC, Lechien KA, Trudell AS. Obesity and cell-free DNA “no calls”: is there an optimal gestational age at time of sampling? [published online ahead of print January 28, 2017]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.011.

- Health risks of obesity. MedlinePlus website. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000348.htm. Updated February 7, 2017. Accessed March 10, 2017.

cfDNA screening failures occur in 1% to 12% of samples, a rate that has an inverse relationship to gestational age. Recent studies have shown an increased risk for screening failures among obese women. To determine the optimal gestational age for cfDNA testing among obese women, Mary C. Livergood, MD, and colleagues at the Mercy Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, performed a retrospective cohort study of those undergoing cfDNA testing at one center from 2011 through 2016. Study results recently were published online in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1

Details of the study

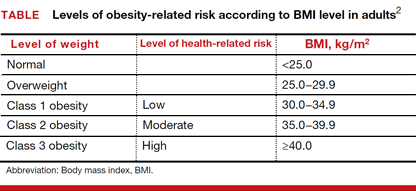

Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for a cfDNA screening failure (referred to as a “no call” in the study) were determined for each body mass index (BMI) weight class (TABLE). Each BMI weight class also was compared with the aOR of normal-weight women (BMI <25.0 kg/m2). The predicted probability of a no call was determined for each week of gestational age for normal weight and obese women and the results were compared.1

Among the 2,385 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 4.4% (n = 105) received a no call. Compared with normal weight women, the aOR of no call increased as weight increased from overweight (aOR, 2.31 [95% CI, 1.21–4.42]) to obesity class III (aOR, 8.55 [95% CI, 4.16–17.56]).1

At 21 weeks’ gestation, a cut-point was identified for obesity class II/III women (ie, there was no longer a significant difference in the probability of no call when compared with normal-weight women). From 8 to 16 weeks’ gestation, there was a 4.5% reduction in the probability of a no call for obesity class II/III women (aOR, 14.9; 95% CI, 8.95–20.78 and aOR, 10.4; 95% CI, 7.20–13.61; Ptrend<.01).1

Although the authors conclude that a cut-point of 21 weeks’ gestation allowed for optimal sampling of cfDNA in obese women, they also acknowledge that this cut-point limits a woman’s reproductive choices. However, they say that delaying cfDNA testing in obese women is a reasonable strategy to reduce the probability of screening failure.1

cfDNA screening failures occur in 1% to 12% of samples, a rate that has an inverse relationship to gestational age. Recent studies have shown an increased risk for screening failures among obese women. To determine the optimal gestational age for cfDNA testing among obese women, Mary C. Livergood, MD, and colleagues at the Mercy Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, performed a retrospective cohort study of those undergoing cfDNA testing at one center from 2011 through 2016. Study results recently were published online in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1

Details of the study

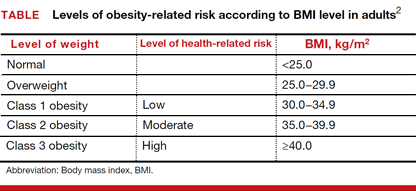

Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for a cfDNA screening failure (referred to as a “no call” in the study) were determined for each body mass index (BMI) weight class (TABLE). Each BMI weight class also was compared with the aOR of normal-weight women (BMI <25.0 kg/m2). The predicted probability of a no call was determined for each week of gestational age for normal weight and obese women and the results were compared.1

Among the 2,385 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 4.4% (n = 105) received a no call. Compared with normal weight women, the aOR of no call increased as weight increased from overweight (aOR, 2.31 [95% CI, 1.21–4.42]) to obesity class III (aOR, 8.55 [95% CI, 4.16–17.56]).1

At 21 weeks’ gestation, a cut-point was identified for obesity class II/III women (ie, there was no longer a significant difference in the probability of no call when compared with normal-weight women). From 8 to 16 weeks’ gestation, there was a 4.5% reduction in the probability of a no call for obesity class II/III women (aOR, 14.9; 95% CI, 8.95–20.78 and aOR, 10.4; 95% CI, 7.20–13.61; Ptrend<.01).1

Although the authors conclude that a cut-point of 21 weeks’ gestation allowed for optimal sampling of cfDNA in obese women, they also acknowledge that this cut-point limits a woman’s reproductive choices. However, they say that delaying cfDNA testing in obese women is a reasonable strategy to reduce the probability of screening failure.1

- Livergood MC, Lechien KA, Trudell AS. Obesity and cell-free DNA “no calls”: is there an optimal gestational age at time of sampling? [published online ahead of print January 28, 2017]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.011.

- Health risks of obesity. MedlinePlus website. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000348.htm. Updated February 7, 2017. Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Livergood MC, Lechien KA, Trudell AS. Obesity and cell-free DNA “no calls”: is there an optimal gestational age at time of sampling? [published online ahead of print January 28, 2017]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.011.

- Health risks of obesity. MedlinePlus website. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000348.htm. Updated February 7, 2017. Accessed March 10, 2017.

ObGyn salaries jumped in the last year

The mean income for ObGyns rose by 10% in 2015 over 2014 ($277,000 compared with $249,000), according to a recent report from Medscape.1 This jump follows a gradual increase over the last few years ($243,000 in 2013; $242,000 in 2012; $220,000 in 2011).1−3 The report included responses from 19,183 physicians across 26 specialties, 5% (nearly 1,000) of whom were ObGyns.1

The highest earners among all physician specialties were orthopedists ($443,000), cardiologists, and dermatologists. The lowest earners were pediatricians ($204,000), endocrinologists, and family physicians. The highest ObGyn earners lived in the Southwest ($307,000), the North Central region, and the West.1

Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a national physician search and consulting firm, recently evaluated the annual starting salaries and year-over-year increases of 3,342 of its physician and advanced practitioner recruiting assignments. They found that ObGyns had the second greatest increase in starting salaries among specialties, at 16%. They also found obstetrics and gynecology to be among the top 5 specialties most in demand.4

The gender picture

As in past years, male ObGyns reported higher earnings than their female counterparts: full-time male ObGyns earned $304,000 while full-time female ObGyns earned $256,000.1

According to a report published in the British Medical Journal in June 2016, there are drastic differences between the incomes of white and black male and female physicians in the United States.5 White male physicians had an adjusted median annual income of $253,042 (95% confidence interval [CI], $248,670−$257,413), compared with $188,230 ($170,844−$205,616) for black male physicians, $163,234 (95% CI, $159,912−$166,557) for white female physicians, and $152,784 (95% CI, $137,927−$167,641) for black female physicians.

How does employment status factor in? Of the self-employed, men earn $310,000 while women earn $285,000. Men who are employed report earning $293,000, with women reporting $244,000.5 (This includes full-time workers but does not control for the number of hours worked.) When Medscape evaluated full- versus part-time work (<40 hours per week), results indicated that, among primary care and most other specialties, more female physicians (25%) are part-timers than males (12%).6 However, among ObGyns, 13% of women report part-time employment versus 16% of men.1

Time with patients. Medscape reports that, among all physicians, 41% of men spent 17 minutes or more with their patients, compared with 49% of women. For office-based ObGyns, 31% of men and 39% of women spent 17 minutes or more with patients.1

Can disparity in leadership positions explain gender-related salary discrepancy?

In 2015, 48% of all medical students were female.7 In residency, the ratio of men to women is similar: For 2013−2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reported that 46% of all residents were female.8 For ObGyn residency, however, the AMA’s FREIDA Online specialty training search (detailing 2014 general program information) indicates that, of the 5,018 active residents and fellows in ObGyn, 81.4% are female.9

Although the ObGyn field is becoming female-dominated, leadership within the specialty remains male dominated, points out Laura E. Baecher-Lind, MD, MPH, Director of the Division of General Obstetrics & Gynecology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Baecher-Lind authored a study in 2012 in which she explored whether the proportions of ObGyn leadership positions held by women reflect the proportion of women who entered the field at the same time as current leaders.10 She found that very few academic department chair positions in ObGyn are held by women, although that number is gradually increasing.10 In addition, her study results indicated that women should hold 71 of the total of 194 ObGyn leadership positions. In actuality, 41 of the leadership positions were held by women (21.1%, P<.001) when based on the proportion of women entering residency programs. When considering only leaders who graduated during the years in which residency matching data were available, she found that women should hold 28 of 74 leadership positions, but they actually held 20 (27.0%, P = .05).10

Could the salary discrepancy disappear if more women held leadership positions? OBG <scaps>Management</scaps> posed this question to Dr. Baecher-Lind. “I suspect that the gender pay gap would persist,” she said. “Studies indicate that women hold implicit gender bias as strongly as men. This bias leads to devaluing women’s skills and accomplishments compared with men’s and is a strong contributor to the leadership and pay gaps in this country and in our specialty. We need to be mindful of this implicit bias and work against it with policies such as salary transparency and salary audits to encourage parity.”11

Do patients have a gender preference for their ObGyn?

Although multiple surveys have been published regarding patient gender preference when choosing an ObGyn, overall results have not been analyzed. To address this literature gap, Kyle J. Tobler, MD, and colleagues at the Womack Army Medical Center in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, searched multiple sources to provide a conglomerate analysis of patients' gender preference when choosing an ObGyn. An abstract describing their study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology in May 2016 and presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2016 Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, May 14−17, in Washington, DC.1

A personal impetus for studying gender preference

The impetus for this project truly was initiated for Dr. Tobler when he was a 4th-year medical student. "I was trying to decide if Obstetrics and Gynecology was the right field for me," he said. "I was discouraged by many people around me, who told me that men in ObGyn would not have a place, as female patients only wanted female ObGyns. And with the residency match at 60% to 70% women for ObGyn, it did seem that men would not have a place. Thus, I began searching the literature to verify if the question for gender preference for their ObGyn provider had been evaluated previously, and I found mixed results." After medical school Dr. Tobler pursued this current meta-analysis to address the conflict-ing results.

Details of the study

Dr. Tobler and his colleagues explored PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO (American Psychological Association's medical literature database), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCO Health's database), Scopus (Elsevier's abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature), and references of relevant articles. Included were 4,822 electronically identified citations of English-language studies, including surveys administered to patients that specifically asked for gender preference of their ObGyn provider.

The researchers found that 23 studies met their inclusion criteria, comprising 14,736 patients. Overall, 8.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.09) of ObGyn patients reported a preference for a male provider, 50.2% (95% CI, 0.49-0.51) preferred a female provider, and 41.3% (95% CI, 0.40-0.42) reported no gender preference when choosing an ObGyn.1

What about US patients?

A subanalysis of studies (n = 9,861) conducted in the United States from 1999 to 2008 (with the last search undertaken in April 2015) showed that 8.4% (95% CI, 0.08-0.09) preferred a male ObGyn, 53.2% (95% CI, 0.52-0.54) preferred a female ObGyn, and 38.5% (95% CI, 0.38-0.39) had no gender preference.1

"We were surprised by the numbers," comments Dr. Tobler. "The general trend demonstrated a mix between no preference or a preference for female providers, but not by a large margin."

"We considered analyzing for age," he said, "but most of the studies gave a mean or median age value and were widely distributed. We were able, however, to break our analysis down into regions where one would expect a very strong preference for female providers--the Middle East and Africa. But, in fact, results were not much different than for Western countries. Our results for this subanalysis of Middle Eastern countries and Nigeria (n = 1,951) demonstrated that 8.7% of women (95% CI, 4.1-13.3) preferred a male provider, 51.2% (95% CI, 17.2-85.1) preferred a female provider, and 46.9% (95% CI, 9.3-84.5) had no gender preference."1

References

- Tobler KJ, Wu J, Khafagy AM, et al. Gender preference of the obstetrician gynecologist provider: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5)(suppl):43S. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/page/results.aspx?txtkeywords=Gender+preference+of+the+obstetrician+gynecologist+provider. Accessed May 18, 2016.

What are ObGyns’ greatest practice concerns?

The Medicus Firm reported in its 2016 Physician Practice Preference and Relocation Survey that the top 3 major practice concerns for practicing physicians were compensation, work-life balance, and work-related burnout and stress.12 They found that physicians in general were slightly more satisfied with their 2015 income than their 2014 income, but less optimistic about the future. Only 29% projected that their 2016 income would increase over their 2015 earnings.

With ObGyn salaries on the up in 2015, less than half (46%) of ObGyns reported to Medscape that they feel fairly compensated; these physicians made $62,000 more than those who believed their pay was unfair.1 Fifty-four percent of employed male ObGyns and 64% of employed female ObGyns reported feeling fairly compensated, compared with 43% and 32%, respectively, who were self-employed.

ObGyns indicated in the 2016 Medscape report that the prime causes of stress were bureaucratic tasks and spending too many hours at work. More than half (52%) of ObGyns spend 30 to 45 hours per week seeing patients, and 40% spend more time than that.1 According to employment status, 56% of those who are self-employed and 58% of those who are employed spend 10 hours or more per week on administrative tasks.1

Lucia DiVenere, MA, Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Washington, DC, offers a brief look, with an in-depth focus to come in an upcoming issue, at the growing concern of burnout among physicians and how it can affect both ObGyns and their patients. She outlines ACOG’s efforts to help ObGyns maintain work-life balance in “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim.”

ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim

Lucia DiVenere, MA

The good news: More women have access to coverage for health care than ever before--better insurance coverage for pregnancy, contraceptives, and well-woman care.

The bad news: America faces a shortage of ObGyns to provide that care, a shortage not likely to go away soon.

One of the imperatives of this dynamic is that we need to help every practicing ObGyn perform at his or her very best: your highest level of quality care, your best productivity, and your best ability to survive and thrive in an always changing and often challenging work environment.

This imperative is undermined when ObGyns are so stressed, overworked, overworried, and undersupported that you experience the very real effects of physician burnout.

Studies show that:

- ObGyns experience high rates of burnout

- rates of burnout are increasing over time

- women, the majority gender in obstetrics and gynecology, experience higher rates of burnout than their male counterparts.

Between 2011 and 2014, rates of physician burnout increased from 45.5% to 54.4%.1 Fifty-one percent of ObGyns reported experiencing burnout in 2015, with women reporting 55% compared to 46% for men.2

This insert is a quick look at this important issue, which can seriously erode an ObGyn's ability to provide high-quality care and continue enjoying practice. It can take a real toll on your personal health and well-being, too. In an upcoming issue of OBG Management, I will take a deeper dive, previewing the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and American Medical Association resources to help you avoid burnout, plus highlighting ObGyns who provide insight and inspiration. I also will interview ACOG President Tom Gellhaus, MD, who is dedicating his presidency to providing you with opportunities to experience new and meaningful aspects of the ObGyn specialty. I will discuss ACOG's programs to help you combat burnout, as well as how you can:

- help underserved women around the globe through medical missions

- bring your leadership and passion for women's health to your state and national capitals

- explore your artistic side.

ObGyn burnout amounts to a public health challenge in women's health care. ACOG takes your well-being seriously, so that you can continue to ensure the well-being of women.

Lucia DiVenere, MA, is Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Washington, DC.

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article. .

References

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Effects of the ACA on ObGyns

As of February 2016, 12.7 million Americans selected plans through the Health Insurance Marketplace of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1 Physicians often have no choice in whether or not they participate in Health Insurance Exchanges; however, in 2016, 24% of ObGyns said they plan to participate in exchanges, 25% do not, and the rest are unsure.1

It is still unclear how the ACA affects physician income.1 When ObGyns who participated in Health Insurance Exchanges in 2015 were asked whether their income was affected, approximately 60% reported no change, 30% reported a decrease, and 9% said it increased.1

Medicus reported that physicians’ approval of the ACA has declined since last year. In their 2016 report, 71% of respondents gave the ACA a passing grade (A, B, C, or D), compared with 83% in 2015 and 77% in 2014. Fewer than 3% of 2016 respondents gave the ACA an “A.”12

Medscape reported that 36% of ObGyns have seen an increase in the number of patients due to the ACA.1 A 2015 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund assessing the experiences and attitudes of primary care providers after the first year of ACA coverage found no association with lower- and higher-quality care whether or not patient load had increased.13 Among those in the Medscape report who said that quality of care had worsened, 21% had a greater patient load; 18% reported no increase in patient load. Seventy-eight percent of physicians whose patient load increased said that quality had stayed the same or improved; 82% of those who experienced no increase in patient load reported that quality had stayed the same or improved.1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Peckham C. Medscape Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2016. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/womenshealth. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Reale D, Yates J. ObGyn salaries continue gradual improvement. OBG Manag. 2015;27(7):34−37.

- Peckham C. Medscape Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2014. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/womenshealth. Published April 14, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Merritt Hawkins. Survey: Starting salaries for physicians spiking. http://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins/Pdf/Merritt_Hawkins_Starting_Salaries_For_Physicians_Spiking.pdf. Published June 7, 2016. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB, Newhouse RL. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study [published online ahead of print June 7, 2016]. BMJ. 2016;353:i2923. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2923. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2016. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of medical school graduates by gender. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/medical-school-graduates-by-gender/. Published 2016. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM, Raezer CL, Sloane RA. The state of women in academic medicine, 2013-2014. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- American Medical Association. FREIDA Online specialty training search: Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2014. https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/user/specStatisticsSearch.do?method=viewDetail&pageNumber=2&spcCd=220. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- Baecher-Lind L. Women in leadership positions within obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1415−1418.

- Email correspondence with Laura E. Baecher-Lind, June 19, 2016.

- Medicus Firm. The Medicus Firm releases annual Physician Practice Preference Survey for 2016. http://www .themedicusfirm.com/the-medicus-firm-releases-annual-physician-practice-preference-survey-for-2016. Published May 4, 2016. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- Hamel L, Doty MM, Norton M, et al; Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund. Experiences and attitudes of primary care providers under the first year of ACA coverage expansion. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/jun/primary-care-providers-first-year-aca. Published June 18, 2015. Accessed June 15, 2016.

The mean income for ObGyns rose by 10% in 2015 over 2014 ($277,000 compared with $249,000), according to a recent report from Medscape.1 This jump follows a gradual increase over the last few years ($243,000 in 2013; $242,000 in 2012; $220,000 in 2011).1−3 The report included responses from 19,183 physicians across 26 specialties, 5% (nearly 1,000) of whom were ObGyns.1

The highest earners among all physician specialties were orthopedists ($443,000), cardiologists, and dermatologists. The lowest earners were pediatricians ($204,000), endocrinologists, and family physicians. The highest ObGyn earners lived in the Southwest ($307,000), the North Central region, and the West.1

Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a national physician search and consulting firm, recently evaluated the annual starting salaries and year-over-year increases of 3,342 of its physician and advanced practitioner recruiting assignments. They found that ObGyns had the second greatest increase in starting salaries among specialties, at 16%. They also found obstetrics and gynecology to be among the top 5 specialties most in demand.4

The gender picture

As in past years, male ObGyns reported higher earnings than their female counterparts: full-time male ObGyns earned $304,000 while full-time female ObGyns earned $256,000.1

According to a report published in the British Medical Journal in June 2016, there are drastic differences between the incomes of white and black male and female physicians in the United States.5 White male physicians had an adjusted median annual income of $253,042 (95% confidence interval [CI], $248,670−$257,413), compared with $188,230 ($170,844−$205,616) for black male physicians, $163,234 (95% CI, $159,912−$166,557) for white female physicians, and $152,784 (95% CI, $137,927−$167,641) for black female physicians.

How does employment status factor in? Of the self-employed, men earn $310,000 while women earn $285,000. Men who are employed report earning $293,000, with women reporting $244,000.5 (This includes full-time workers but does not control for the number of hours worked.) When Medscape evaluated full- versus part-time work (<40 hours per week), results indicated that, among primary care and most other specialties, more female physicians (25%) are part-timers than males (12%).6 However, among ObGyns, 13% of women report part-time employment versus 16% of men.1

Time with patients. Medscape reports that, among all physicians, 41% of men spent 17 minutes or more with their patients, compared with 49% of women. For office-based ObGyns, 31% of men and 39% of women spent 17 minutes or more with patients.1

Can disparity in leadership positions explain gender-related salary discrepancy?

In 2015, 48% of all medical students were female.7 In residency, the ratio of men to women is similar: For 2013−2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reported that 46% of all residents were female.8 For ObGyn residency, however, the AMA’s FREIDA Online specialty training search (detailing 2014 general program information) indicates that, of the 5,018 active residents and fellows in ObGyn, 81.4% are female.9

Although the ObGyn field is becoming female-dominated, leadership within the specialty remains male dominated, points out Laura E. Baecher-Lind, MD, MPH, Director of the Division of General Obstetrics & Gynecology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Baecher-Lind authored a study in 2012 in which she explored whether the proportions of ObGyn leadership positions held by women reflect the proportion of women who entered the field at the same time as current leaders.10 She found that very few academic department chair positions in ObGyn are held by women, although that number is gradually increasing.10 In addition, her study results indicated that women should hold 71 of the total of 194 ObGyn leadership positions. In actuality, 41 of the leadership positions were held by women (21.1%, P<.001) when based on the proportion of women entering residency programs. When considering only leaders who graduated during the years in which residency matching data were available, she found that women should hold 28 of 74 leadership positions, but they actually held 20 (27.0%, P = .05).10

Could the salary discrepancy disappear if more women held leadership positions? OBG <scaps>Management</scaps> posed this question to Dr. Baecher-Lind. “I suspect that the gender pay gap would persist,” she said. “Studies indicate that women hold implicit gender bias as strongly as men. This bias leads to devaluing women’s skills and accomplishments compared with men’s and is a strong contributor to the leadership and pay gaps in this country and in our specialty. We need to be mindful of this implicit bias and work against it with policies such as salary transparency and salary audits to encourage parity.”11

Do patients have a gender preference for their ObGyn?

Although multiple surveys have been published regarding patient gender preference when choosing an ObGyn, overall results have not been analyzed. To address this literature gap, Kyle J. Tobler, MD, and colleagues at the Womack Army Medical Center in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, searched multiple sources to provide a conglomerate analysis of patients' gender preference when choosing an ObGyn. An abstract describing their study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology in May 2016 and presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2016 Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, May 14−17, in Washington, DC.1

A personal impetus for studying gender preference

The impetus for this project truly was initiated for Dr. Tobler when he was a 4th-year medical student. "I was trying to decide if Obstetrics and Gynecology was the right field for me," he said. "I was discouraged by many people around me, who told me that men in ObGyn would not have a place, as female patients only wanted female ObGyns. And with the residency match at 60% to 70% women for ObGyn, it did seem that men would not have a place. Thus, I began searching the literature to verify if the question for gender preference for their ObGyn provider had been evaluated previously, and I found mixed results." After medical school Dr. Tobler pursued this current meta-analysis to address the conflict-ing results.

Details of the study

Dr. Tobler and his colleagues explored PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO (American Psychological Association's medical literature database), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCO Health's database), Scopus (Elsevier's abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature), and references of relevant articles. Included were 4,822 electronically identified citations of English-language studies, including surveys administered to patients that specifically asked for gender preference of their ObGyn provider.

The researchers found that 23 studies met their inclusion criteria, comprising 14,736 patients. Overall, 8.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.09) of ObGyn patients reported a preference for a male provider, 50.2% (95% CI, 0.49-0.51) preferred a female provider, and 41.3% (95% CI, 0.40-0.42) reported no gender preference when choosing an ObGyn.1

What about US patients?

A subanalysis of studies (n = 9,861) conducted in the United States from 1999 to 2008 (with the last search undertaken in April 2015) showed that 8.4% (95% CI, 0.08-0.09) preferred a male ObGyn, 53.2% (95% CI, 0.52-0.54) preferred a female ObGyn, and 38.5% (95% CI, 0.38-0.39) had no gender preference.1

"We were surprised by the numbers," comments Dr. Tobler. "The general trend demonstrated a mix between no preference or a preference for female providers, but not by a large margin."

"We considered analyzing for age," he said, "but most of the studies gave a mean or median age value and were widely distributed. We were able, however, to break our analysis down into regions where one would expect a very strong preference for female providers--the Middle East and Africa. But, in fact, results were not much different than for Western countries. Our results for this subanalysis of Middle Eastern countries and Nigeria (n = 1,951) demonstrated that 8.7% of women (95% CI, 4.1-13.3) preferred a male provider, 51.2% (95% CI, 17.2-85.1) preferred a female provider, and 46.9% (95% CI, 9.3-84.5) had no gender preference."1

References

- Tobler KJ, Wu J, Khafagy AM, et al. Gender preference of the obstetrician gynecologist provider: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5)(suppl):43S. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/page/results.aspx?txtkeywords=Gender+preference+of+the+obstetrician+gynecologist+provider. Accessed May 18, 2016.

What are ObGyns’ greatest practice concerns?

The Medicus Firm reported in its 2016 Physician Practice Preference and Relocation Survey that the top 3 major practice concerns for practicing physicians were compensation, work-life balance, and work-related burnout and stress.12 They found that physicians in general were slightly more satisfied with their 2015 income than their 2014 income, but less optimistic about the future. Only 29% projected that their 2016 income would increase over their 2015 earnings.

With ObGyn salaries on the up in 2015, less than half (46%) of ObGyns reported to Medscape that they feel fairly compensated; these physicians made $62,000 more than those who believed their pay was unfair.1 Fifty-four percent of employed male ObGyns and 64% of employed female ObGyns reported feeling fairly compensated, compared with 43% and 32%, respectively, who were self-employed.

ObGyns indicated in the 2016 Medscape report that the prime causes of stress were bureaucratic tasks and spending too many hours at work. More than half (52%) of ObGyns spend 30 to 45 hours per week seeing patients, and 40% spend more time than that.1 According to employment status, 56% of those who are self-employed and 58% of those who are employed spend 10 hours or more per week on administrative tasks.1

Lucia DiVenere, MA, Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Washington, DC, offers a brief look, with an in-depth focus to come in an upcoming issue, at the growing concern of burnout among physicians and how it can affect both ObGyns and their patients. She outlines ACOG’s efforts to help ObGyns maintain work-life balance in “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim.”

ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim

Lucia DiVenere, MA

The good news: More women have access to coverage for health care than ever before--better insurance coverage for pregnancy, contraceptives, and well-woman care.

The bad news: America faces a shortage of ObGyns to provide that care, a shortage not likely to go away soon.

One of the imperatives of this dynamic is that we need to help every practicing ObGyn perform at his or her very best: your highest level of quality care, your best productivity, and your best ability to survive and thrive in an always changing and often challenging work environment.

This imperative is undermined when ObGyns are so stressed, overworked, overworried, and undersupported that you experience the very real effects of physician burnout.

Studies show that:

- ObGyns experience high rates of burnout

- rates of burnout are increasing over time

- women, the majority gender in obstetrics and gynecology, experience higher rates of burnout than their male counterparts.

Between 2011 and 2014, rates of physician burnout increased from 45.5% to 54.4%.1 Fifty-one percent of ObGyns reported experiencing burnout in 2015, with women reporting 55% compared to 46% for men.2

This insert is a quick look at this important issue, which can seriously erode an ObGyn's ability to provide high-quality care and continue enjoying practice. It can take a real toll on your personal health and well-being, too. In an upcoming issue of OBG Management, I will take a deeper dive, previewing the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and American Medical Association resources to help you avoid burnout, plus highlighting ObGyns who provide insight and inspiration. I also will interview ACOG President Tom Gellhaus, MD, who is dedicating his presidency to providing you with opportunities to experience new and meaningful aspects of the ObGyn specialty. I will discuss ACOG's programs to help you combat burnout, as well as how you can:

- help underserved women around the globe through medical missions

- bring your leadership and passion for women's health to your state and national capitals

- explore your artistic side.

ObGyn burnout amounts to a public health challenge in women's health care. ACOG takes your well-being seriously, so that you can continue to ensure the well-being of women.

Lucia DiVenere, MA, is Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Washington, DC.

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article. .

References

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Effects of the ACA on ObGyns

As of February 2016, 12.7 million Americans selected plans through the Health Insurance Marketplace of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1 Physicians often have no choice in whether or not they participate in Health Insurance Exchanges; however, in 2016, 24% of ObGyns said they plan to participate in exchanges, 25% do not, and the rest are unsure.1

It is still unclear how the ACA affects physician income.1 When ObGyns who participated in Health Insurance Exchanges in 2015 were asked whether their income was affected, approximately 60% reported no change, 30% reported a decrease, and 9% said it increased.1

Medicus reported that physicians’ approval of the ACA has declined since last year. In their 2016 report, 71% of respondents gave the ACA a passing grade (A, B, C, or D), compared with 83% in 2015 and 77% in 2014. Fewer than 3% of 2016 respondents gave the ACA an “A.”12

Medscape reported that 36% of ObGyns have seen an increase in the number of patients due to the ACA.1 A 2015 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund assessing the experiences and attitudes of primary care providers after the first year of ACA coverage found no association with lower- and higher-quality care whether or not patient load had increased.13 Among those in the Medscape report who said that quality of care had worsened, 21% had a greater patient load; 18% reported no increase in patient load. Seventy-eight percent of physicians whose patient load increased said that quality had stayed the same or improved; 82% of those who experienced no increase in patient load reported that quality had stayed the same or improved.1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The mean income for ObGyns rose by 10% in 2015 over 2014 ($277,000 compared with $249,000), according to a recent report from Medscape.1 This jump follows a gradual increase over the last few years ($243,000 in 2013; $242,000 in 2012; $220,000 in 2011).1−3 The report included responses from 19,183 physicians across 26 specialties, 5% (nearly 1,000) of whom were ObGyns.1

The highest earners among all physician specialties were orthopedists ($443,000), cardiologists, and dermatologists. The lowest earners were pediatricians ($204,000), endocrinologists, and family physicians. The highest ObGyn earners lived in the Southwest ($307,000), the North Central region, and the West.1

Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a national physician search and consulting firm, recently evaluated the annual starting salaries and year-over-year increases of 3,342 of its physician and advanced practitioner recruiting assignments. They found that ObGyns had the second greatest increase in starting salaries among specialties, at 16%. They also found obstetrics and gynecology to be among the top 5 specialties most in demand.4

The gender picture

As in past years, male ObGyns reported higher earnings than their female counterparts: full-time male ObGyns earned $304,000 while full-time female ObGyns earned $256,000.1

According to a report published in the British Medical Journal in June 2016, there are drastic differences between the incomes of white and black male and female physicians in the United States.5 White male physicians had an adjusted median annual income of $253,042 (95% confidence interval [CI], $248,670−$257,413), compared with $188,230 ($170,844−$205,616) for black male physicians, $163,234 (95% CI, $159,912−$166,557) for white female physicians, and $152,784 (95% CI, $137,927−$167,641) for black female physicians.

How does employment status factor in? Of the self-employed, men earn $310,000 while women earn $285,000. Men who are employed report earning $293,000, with women reporting $244,000.5 (This includes full-time workers but does not control for the number of hours worked.) When Medscape evaluated full- versus part-time work (<40 hours per week), results indicated that, among primary care and most other specialties, more female physicians (25%) are part-timers than males (12%).6 However, among ObGyns, 13% of women report part-time employment versus 16% of men.1

Time with patients. Medscape reports that, among all physicians, 41% of men spent 17 minutes or more with their patients, compared with 49% of women. For office-based ObGyns, 31% of men and 39% of women spent 17 minutes or more with patients.1

Can disparity in leadership positions explain gender-related salary discrepancy?

In 2015, 48% of all medical students were female.7 In residency, the ratio of men to women is similar: For 2013−2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reported that 46% of all residents were female.8 For ObGyn residency, however, the AMA’s FREIDA Online specialty training search (detailing 2014 general program information) indicates that, of the 5,018 active residents and fellows in ObGyn, 81.4% are female.9

Although the ObGyn field is becoming female-dominated, leadership within the specialty remains male dominated, points out Laura E. Baecher-Lind, MD, MPH, Director of the Division of General Obstetrics & Gynecology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Baecher-Lind authored a study in 2012 in which she explored whether the proportions of ObGyn leadership positions held by women reflect the proportion of women who entered the field at the same time as current leaders.10 She found that very few academic department chair positions in ObGyn are held by women, although that number is gradually increasing.10 In addition, her study results indicated that women should hold 71 of the total of 194 ObGyn leadership positions. In actuality, 41 of the leadership positions were held by women (21.1%, P<.001) when based on the proportion of women entering residency programs. When considering only leaders who graduated during the years in which residency matching data were available, she found that women should hold 28 of 74 leadership positions, but they actually held 20 (27.0%, P = .05).10

Could the salary discrepancy disappear if more women held leadership positions? OBG <scaps>Management</scaps> posed this question to Dr. Baecher-Lind. “I suspect that the gender pay gap would persist,” she said. “Studies indicate that women hold implicit gender bias as strongly as men. This bias leads to devaluing women’s skills and accomplishments compared with men’s and is a strong contributor to the leadership and pay gaps in this country and in our specialty. We need to be mindful of this implicit bias and work against it with policies such as salary transparency and salary audits to encourage parity.”11

Do patients have a gender preference for their ObGyn?

Although multiple surveys have been published regarding patient gender preference when choosing an ObGyn, overall results have not been analyzed. To address this literature gap, Kyle J. Tobler, MD, and colleagues at the Womack Army Medical Center in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, searched multiple sources to provide a conglomerate analysis of patients' gender preference when choosing an ObGyn. An abstract describing their study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology in May 2016 and presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2016 Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, May 14−17, in Washington, DC.1

A personal impetus for studying gender preference

The impetus for this project truly was initiated for Dr. Tobler when he was a 4th-year medical student. "I was trying to decide if Obstetrics and Gynecology was the right field for me," he said. "I was discouraged by many people around me, who told me that men in ObGyn would not have a place, as female patients only wanted female ObGyns. And with the residency match at 60% to 70% women for ObGyn, it did seem that men would not have a place. Thus, I began searching the literature to verify if the question for gender preference for their ObGyn provider had been evaluated previously, and I found mixed results." After medical school Dr. Tobler pursued this current meta-analysis to address the conflict-ing results.

Details of the study

Dr. Tobler and his colleagues explored PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO (American Psychological Association's medical literature database), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCO Health's database), Scopus (Elsevier's abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature), and references of relevant articles. Included were 4,822 electronically identified citations of English-language studies, including surveys administered to patients that specifically asked for gender preference of their ObGyn provider.

The researchers found that 23 studies met their inclusion criteria, comprising 14,736 patients. Overall, 8.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.09) of ObGyn patients reported a preference for a male provider, 50.2% (95% CI, 0.49-0.51) preferred a female provider, and 41.3% (95% CI, 0.40-0.42) reported no gender preference when choosing an ObGyn.1

What about US patients?

A subanalysis of studies (n = 9,861) conducted in the United States from 1999 to 2008 (with the last search undertaken in April 2015) showed that 8.4% (95% CI, 0.08-0.09) preferred a male ObGyn, 53.2% (95% CI, 0.52-0.54) preferred a female ObGyn, and 38.5% (95% CI, 0.38-0.39) had no gender preference.1

"We were surprised by the numbers," comments Dr. Tobler. "The general trend demonstrated a mix between no preference or a preference for female providers, but not by a large margin."

"We considered analyzing for age," he said, "but most of the studies gave a mean or median age value and were widely distributed. We were able, however, to break our analysis down into regions where one would expect a very strong preference for female providers--the Middle East and Africa. But, in fact, results were not much different than for Western countries. Our results for this subanalysis of Middle Eastern countries and Nigeria (n = 1,951) demonstrated that 8.7% of women (95% CI, 4.1-13.3) preferred a male provider, 51.2% (95% CI, 17.2-85.1) preferred a female provider, and 46.9% (95% CI, 9.3-84.5) had no gender preference."1

References

- Tobler KJ, Wu J, Khafagy AM, et al. Gender preference of the obstetrician gynecologist provider: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5)(suppl):43S. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/page/results.aspx?txtkeywords=Gender+preference+of+the+obstetrician+gynecologist+provider. Accessed May 18, 2016.

What are ObGyns’ greatest practice concerns?

The Medicus Firm reported in its 2016 Physician Practice Preference and Relocation Survey that the top 3 major practice concerns for practicing physicians were compensation, work-life balance, and work-related burnout and stress.12 They found that physicians in general were slightly more satisfied with their 2015 income than their 2014 income, but less optimistic about the future. Only 29% projected that their 2016 income would increase over their 2015 earnings.

With ObGyn salaries on the up in 2015, less than half (46%) of ObGyns reported to Medscape that they feel fairly compensated; these physicians made $62,000 more than those who believed their pay was unfair.1 Fifty-four percent of employed male ObGyns and 64% of employed female ObGyns reported feeling fairly compensated, compared with 43% and 32%, respectively, who were self-employed.

ObGyns indicated in the 2016 Medscape report that the prime causes of stress were bureaucratic tasks and spending too many hours at work. More than half (52%) of ObGyns spend 30 to 45 hours per week seeing patients, and 40% spend more time than that.1 According to employment status, 56% of those who are self-employed and 58% of those who are employed spend 10 hours or more per week on administrative tasks.1

Lucia DiVenere, MA, Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Washington, DC, offers a brief look, with an in-depth focus to come in an upcoming issue, at the growing concern of burnout among physicians and how it can affect both ObGyns and their patients. She outlines ACOG’s efforts to help ObGyns maintain work-life balance in “ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim.”

ObGyn burnout: ACOG takes aim

Lucia DiVenere, MA

The good news: More women have access to coverage for health care than ever before--better insurance coverage for pregnancy, contraceptives, and well-woman care.

The bad news: America faces a shortage of ObGyns to provide that care, a shortage not likely to go away soon.

One of the imperatives of this dynamic is that we need to help every practicing ObGyn perform at his or her very best: your highest level of quality care, your best productivity, and your best ability to survive and thrive in an always changing and often challenging work environment.

This imperative is undermined when ObGyns are so stressed, overworked, overworried, and undersupported that you experience the very real effects of physician burnout.

Studies show that:

- ObGyns experience high rates of burnout

- rates of burnout are increasing over time

- women, the majority gender in obstetrics and gynecology, experience higher rates of burnout than their male counterparts.

Between 2011 and 2014, rates of physician burnout increased from 45.5% to 54.4%.1 Fifty-one percent of ObGyns reported experiencing burnout in 2015, with women reporting 55% compared to 46% for men.2

This insert is a quick look at this important issue, which can seriously erode an ObGyn's ability to provide high-quality care and continue enjoying practice. It can take a real toll on your personal health and well-being, too. In an upcoming issue of OBG Management, I will take a deeper dive, previewing the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and American Medical Association resources to help you avoid burnout, plus highlighting ObGyns who provide insight and inspiration. I also will interview ACOG President Tom Gellhaus, MD, who is dedicating his presidency to providing you with opportunities to experience new and meaningful aspects of the ObGyn specialty. I will discuss ACOG's programs to help you combat burnout, as well as how you can:

- help underserved women around the globe through medical missions

- bring your leadership and passion for women's health to your state and national capitals

- explore your artistic side.

ObGyn burnout amounts to a public health challenge in women's health care. ACOG takes your well-being seriously, so that you can continue to ensure the well-being of women.

Lucia DiVenere, MA, is Officer, Government and Political Affairs, at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Washington, DC.

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article. .

References

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

- Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2016: Bias and Burnout. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2016/public/overview. Published January 13, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Effects of the ACA on ObGyns

As of February 2016, 12.7 million Americans selected plans through the Health Insurance Marketplace of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1 Physicians often have no choice in whether or not they participate in Health Insurance Exchanges; however, in 2016, 24% of ObGyns said they plan to participate in exchanges, 25% do not, and the rest are unsure.1

It is still unclear how the ACA affects physician income.1 When ObGyns who participated in Health Insurance Exchanges in 2015 were asked whether their income was affected, approximately 60% reported no change, 30% reported a decrease, and 9% said it increased.1

Medicus reported that physicians’ approval of the ACA has declined since last year. In their 2016 report, 71% of respondents gave the ACA a passing grade (A, B, C, or D), compared with 83% in 2015 and 77% in 2014. Fewer than 3% of 2016 respondents gave the ACA an “A.”12

Medscape reported that 36% of ObGyns have seen an increase in the number of patients due to the ACA.1 A 2015 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund assessing the experiences and attitudes of primary care providers after the first year of ACA coverage found no association with lower- and higher-quality care whether or not patient load had increased.13 Among those in the Medscape report who said that quality of care had worsened, 21% had a greater patient load; 18% reported no increase in patient load. Seventy-eight percent of physicians whose patient load increased said that quality had stayed the same or improved; 82% of those who experienced no increase in patient load reported that quality had stayed the same or improved.1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Peckham C. Medscape Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2016. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/womenshealth. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Reale D, Yates J. ObGyn salaries continue gradual improvement. OBG Manag. 2015;27(7):34−37.

- Peckham C. Medscape Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2014. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/womenshealth. Published April 14, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Merritt Hawkins. Survey: Starting salaries for physicians spiking. http://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins/Pdf/Merritt_Hawkins_Starting_Salaries_For_Physicians_Spiking.pdf. Published June 7, 2016. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB, Newhouse RL. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study [published online ahead of print June 7, 2016]. BMJ. 2016;353:i2923. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2923. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2016. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of medical school graduates by gender. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/medical-school-graduates-by-gender/. Published 2016. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM, Raezer CL, Sloane RA. The state of women in academic medicine, 2013-2014. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- American Medical Association. FREIDA Online specialty training search: Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2014. https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/user/specStatisticsSearch.do?method=viewDetail&pageNumber=2&spcCd=220. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- Baecher-Lind L. Women in leadership positions within obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1415−1418.

- Email correspondence with Laura E. Baecher-Lind, June 19, 2016.

- Medicus Firm. The Medicus Firm releases annual Physician Practice Preference Survey for 2016. http://www .themedicusfirm.com/the-medicus-firm-releases-annual-physician-practice-preference-survey-for-2016. Published May 4, 2016. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- Hamel L, Doty MM, Norton M, et al; Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund. Experiences and attitudes of primary care providers under the first year of ACA coverage expansion. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/jun/primary-care-providers-first-year-aca. Published June 18, 2015. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Peckham C. Medscape Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2016. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/womenshealth. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Reale D, Yates J. ObGyn salaries continue gradual improvement. OBG Manag. 2015;27(7):34−37.

- Peckham C. Medscape Ob/Gyn Compensation Report 2014. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2014/womenshealth. Published April 14, 2014. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Merritt Hawkins. Survey: Starting salaries for physicians spiking. http://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins/Pdf/Merritt_Hawkins_Starting_Salaries_For_Physicians_Spiking.pdf. Published June 7, 2016. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB, Newhouse RL. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study [published online ahead of print June 7, 2016]. BMJ. 2016;353:i2923. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2923. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2016. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/public/overview#page=1. Published April 1, 2016. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of medical school graduates by gender. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/medical-school-graduates-by-gender/. Published 2016. Accessed June 22, 2016.

- Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM, Raezer CL, Sloane RA. The state of women in academic medicine, 2013-2014. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- American Medical Association. FREIDA Online specialty training search: Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2014. https://freida.ama-assn.org/Freida/user/specStatisticsSearch.do?method=viewDetail&pageNumber=2&spcCd=220. Accessed June 17, 2016.

- Baecher-Lind L. Women in leadership positions within obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1415−1418.

- Email correspondence with Laura E. Baecher-Lind, June 19, 2016.

- Medicus Firm. The Medicus Firm releases annual Physician Practice Preference Survey for 2016. http://www .themedicusfirm.com/the-medicus-firm-releases-annual-physician-practice-preference-survey-for-2016. Published May 4, 2016. Accessed June 10, 2016.

- Hamel L, Doty MM, Norton M, et al; Kaiser Family Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund. Experiences and attitudes of primary care providers under the first year of ACA coverage expansion. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/jun/primary-care-providers-first-year-aca. Published June 18, 2015. Accessed June 15, 2016.

In this Article

- ACOG takes aim at burnout

- Considering salary and leadership disparities

- ObGyns’ greatest practice concerns

Trading Kidneys: Innovative Program Could Save Thousands of Lives

While editing this month’s Renal Consult, I noted the mention of “paired kidney exchange” with particular interest. In 2005, I heard about a relatively new concept: matching two or more incompatible kidney donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. After conducting some research and interviewing experts, I wrote an article on paired kidney exchange for our sister publication, Clinician News. In the subsequent decade, the concept of paired exchange has expanded to the point that as many as 70 people have participated in a 35-kidney exchange. —AMH

Last year, almost 27,000 Americans received an organ transplant—a new national record, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services. Donations from living persons reached nearly 7,000, an increase of 2.3% from 2003. But despite these positive numbers, nearly 88,000 people are on the waiting list for an organ, and about 6,200 died last year before one became available.

But in some areas of the country, an innovative program is gaining momentum: paired kidney exchange, which puts together two or more incompatible donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. And while it will not close the gap between patients in need and those who receive, experts believe it could help thousands of people each year.

The real struggle is finding more willing donors. But Francis Delmonico, MD, Medical Director, New England Organ Bank, Newton, Massachusetts, says paired exchange is “an adjunct. When it can be of help, it’s helped a number of people already. And as with any of this, it’s a lot of work but it’s a tactic that we ought to try and apply anytime we can.”

“There are about 10,000 people who could be put into a program like this,” says Michael A. Rees, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo. “Once you put them into the program, we would hope that 2,000 to 3,000 per year could be matched up and we could do that many extra kidney transplants a year. And that would certainly help to close the gap.”

Continue for how it works >>

HOW IT WORKS

Paired kidney exchange got its start in the US at Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center, Baltimore, in 2001. The concept is simple: Recipient A needs a kidney and has a family member or friend, Donor A, who is willing to give. However, testing reveals that Donor A and Recipient A are incompatible. Meanwhile, Recipient B and Donor B find themselves with the same problem. But, it turns out, Donor B could give to Recipient A and Donor A could give to Recipient B. The patients and their donors are approached with the idea of an exchange, and if they agree, two people receive needed organs.

Twenty-two patients have received kidneys through the Johns Hopkins program, according to Robert A. Montgomery, MD, PhD, Director, Incompatible Kidney Transplant Programs (InKTP). Surgeons at Johns Hopkins have also expanded the exchange to three donor-recipient pairs; “triple swap” operations were performed at the hospital in 2003 and 2004.

“Everyone, when they come for an incompatible transplant, is offered the option of a paired exchange, because … if there’s any way to get a compatible kidney, that’s what you try for first,” says Janet Hiller, RN, MSN, Clinical Nurse Specialist, InKTP. “We’ve only had probably two out of a hundred [patients] who have thought, ‘No, I’d rather just get the kidney from my spouse or loved one.’”

“Patients are surprisingly open to this option, and almost all of them … request it when they are initially seen by me,” Montgomery told Clinician News via e-mail. “Some [recipients] have expressed apprehension about not knowing the donor and not being sure they have taken good care of their kidney. The donors have rarely expressed any concerns; they just want their loved one to receive a kidney…. It has universally been a positive experience.”

Ohio’s Rees first heard about paired exchange at a conference in 2001. He returned to his institution and consulted with the living donor coordinator to see if any pairs could be formed from people who had been willing to donate but unable due to blood type or other incompatibility problems. After identifying two pairs (out of 10 possibilities) for whom an exchange might work, Rees brought the patients and donors in for testing. But alas, the match wasn’t quite right.

“It became clear to me that if I really wanted to make this work, I needed a lot more than 10 pairs [to start with],” Rees says. “The numbers—if you try to match up people—go up logarithmically the more pairs that you have. So the chances you have of creating pairs go up exponentially.”

With this realization in mind, Rees set out to find someone willing to write a computer program that could identify potential matches from a larger bank of people pooled from several facilities. After some false starts—no computer programmer would work on the project for academic glory, the only reward Rees could offer—he convinced his father, Alan, to help. The senior Rees’ prototype was the basis for the current system, which links 10 transplant centers in Ohio.

Working with a larger pool of colleagues required numerous teleconference calls to iron out details for the statewide program. Among the questions were, “Are we going to make the donor travel, or are we going to cut the kidney out at home and ship the kidney in a box of ice to the place where it’s going to be transplanted?” he recalls. “And we decided that the donor has to travel.”

The first kidney exchange in the state of Ohio was performed in early November 2004. The third was scheduled for mid-April.

Creating one system to be shared by medical institutions that would normally be competitors took some work. “Trying to get us all to play in the same sandbox was very difficult,” Rees acknowledges. “But we did that; we stuck it out. And we all agreed to come up with something that we all think is a great idea and should help our patients.”

Delmonico, who is also a Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School and Visiting Surgeon in the Transplant Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, has also seen the gratifying cooperation between medical professionals. “Institutions are competitive in terms of medical care—that’s no mystery,” he says. “But in this instance, the physicians have been simply magnificent in trying to help patients. Innovative programs can be developed and sustained through the kind of collaboration that is going on here.”

The New England paired exchange program, dating back to 2002, is a collaboration involving a dozen hospitals. It started with a paper-and-pen effort (blood type–incompatible patients would be brought to the attention of Delmonico, who would then contact each transplant center, seeking others) but now has its own computer system.

New England also has another variation on the exchange program that is unique to the region, according to Delmonico. “Let’s say I wanted to give to you but I can’t. I’ll give to somebody on the list, and as a result of that donation, you would get a priority for the next available deceased donor kidney in New England,” he explains. “We’ve done that about 20 times now.”

Continue for going national >>

GOING NATIONAL

So where does paired exchange go from here? Johns Hopkins’ Montgomery organized a consensus meeting in March to discuss the possibility of creating a national network; Hiller, Rees, and Delmonico attended.

“I think our goal should be to one day have a national program,” Rees says. “But shipping somebody from Toledo down to Cincinnati is a lot easier to sell to a patient than shipping somebody from Toledo to Los Angeles. And the logistics of trying to do that when you have a whole different set of insurance companies … would be a lot more complicated. So, I think the way to begin is to do it on a more regional basis and prove that the concept works, that people can be satisfied with it, and then begin to expand it.”

Delmonico also thinks a national program is essential. “We need to enlarge the possibility of paired donation and exchange,” he says. “It will not happen successfully in a regional system. There aren’t enough patients that can be identified.” Questions to be answered before such a program could exist, Delmonico notes, include where the system will be based and who will administer it.

“There was a lot of agreement—though not total consensus—on the fact that UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing, would be the most likely place to ‘house’ and to manage the data,” Hiller reports. “They have all those systems in place already [and] are capable of managing this large database.”

Delmonico, as Vice President of UNOS, points out, “We have no authority to do that yet. Whether or not the country wants us to do that also remains to be determined.” But the UNOS Board of Directors is open to the idea; last year, they endorsed the concept of establishing a national paired exchange program with the understanding that details would have to be worked out over time, according to a UNOS spokesperson.

Another obstacle to widespread paired donation may be perceptions of it in the eyes of the government and critics: Could it be construed as a violation of the 1984 National Organ Transplant Act, which says that an organ should not be transplanted for a “value consideration”? Legal experts have assured Delmonico that paired exchanges can be interpreted as a gift.

“The government is also, properly, not wanting to see this as a slope toward buying and selling organs,” Delmonico says. “And I am adamantly opposed to that. In the instances that we’ve done paired exchange here, that’s not in the mix. That’s not our motivation, nor has it been the motivation of these donors. We wouldn’t do it if we felt that was the case.”

Montgomery says it will take several years to get a national system set up. But the bottom line for transplant surgeons is that a national paired kidney exchange program would do a world of good, two people at a time. “This is clearly what is best for our patients,” Montgomery says.

“The bigger we can get, if we can spread it nationally, the more people it will help,” Rees says. “And so we have to think of a way to do this so that we’re all satisfied that it’s moving forward in a way that will make everyone happy.”

Reprinted from Clinician News. 2005;9(5):cover, 3, 15.

While editing this month’s Renal Consult, I noted the mention of “paired kidney exchange” with particular interest. In 2005, I heard about a relatively new concept: matching two or more incompatible kidney donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. After conducting some research and interviewing experts, I wrote an article on paired kidney exchange for our sister publication, Clinician News. In the subsequent decade, the concept of paired exchange has expanded to the point that as many as 70 people have participated in a 35-kidney exchange. —AMH

Last year, almost 27,000 Americans received an organ transplant—a new national record, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services. Donations from living persons reached nearly 7,000, an increase of 2.3% from 2003. But despite these positive numbers, nearly 88,000 people are on the waiting list for an organ, and about 6,200 died last year before one became available.

But in some areas of the country, an innovative program is gaining momentum: paired kidney exchange, which puts together two or more incompatible donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. And while it will not close the gap between patients in need and those who receive, experts believe it could help thousands of people each year.

The real struggle is finding more willing donors. But Francis Delmonico, MD, Medical Director, New England Organ Bank, Newton, Massachusetts, says paired exchange is “an adjunct. When it can be of help, it’s helped a number of people already. And as with any of this, it’s a lot of work but it’s a tactic that we ought to try and apply anytime we can.”

“There are about 10,000 people who could be put into a program like this,” says Michael A. Rees, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo. “Once you put them into the program, we would hope that 2,000 to 3,000 per year could be matched up and we could do that many extra kidney transplants a year. And that would certainly help to close the gap.”

Continue for how it works >>

HOW IT WORKS

Paired kidney exchange got its start in the US at Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center, Baltimore, in 2001. The concept is simple: Recipient A needs a kidney and has a family member or friend, Donor A, who is willing to give. However, testing reveals that Donor A and Recipient A are incompatible. Meanwhile, Recipient B and Donor B find themselves with the same problem. But, it turns out, Donor B could give to Recipient A and Donor A could give to Recipient B. The patients and their donors are approached with the idea of an exchange, and if they agree, two people receive needed organs.

Twenty-two patients have received kidneys through the Johns Hopkins program, according to Robert A. Montgomery, MD, PhD, Director, Incompatible Kidney Transplant Programs (InKTP). Surgeons at Johns Hopkins have also expanded the exchange to three donor-recipient pairs; “triple swap” operations were performed at the hospital in 2003 and 2004.

“Everyone, when they come for an incompatible transplant, is offered the option of a paired exchange, because … if there’s any way to get a compatible kidney, that’s what you try for first,” says Janet Hiller, RN, MSN, Clinical Nurse Specialist, InKTP. “We’ve only had probably two out of a hundred [patients] who have thought, ‘No, I’d rather just get the kidney from my spouse or loved one.’”

“Patients are surprisingly open to this option, and almost all of them … request it when they are initially seen by me,” Montgomery told Clinician News via e-mail. “Some [recipients] have expressed apprehension about not knowing the donor and not being sure they have taken good care of their kidney. The donors have rarely expressed any concerns; they just want their loved one to receive a kidney…. It has universally been a positive experience.”

Ohio’s Rees first heard about paired exchange at a conference in 2001. He returned to his institution and consulted with the living donor coordinator to see if any pairs could be formed from people who had been willing to donate but unable due to blood type or other incompatibility problems. After identifying two pairs (out of 10 possibilities) for whom an exchange might work, Rees brought the patients and donors in for testing. But alas, the match wasn’t quite right.

“It became clear to me that if I really wanted to make this work, I needed a lot more than 10 pairs [to start with],” Rees says. “The numbers—if you try to match up people—go up logarithmically the more pairs that you have. So the chances you have of creating pairs go up exponentially.”

With this realization in mind, Rees set out to find someone willing to write a computer program that could identify potential matches from a larger bank of people pooled from several facilities. After some false starts—no computer programmer would work on the project for academic glory, the only reward Rees could offer—he convinced his father, Alan, to help. The senior Rees’ prototype was the basis for the current system, which links 10 transplant centers in Ohio.

Working with a larger pool of colleagues required numerous teleconference calls to iron out details for the statewide program. Among the questions were, “Are we going to make the donor travel, or are we going to cut the kidney out at home and ship the kidney in a box of ice to the place where it’s going to be transplanted?” he recalls. “And we decided that the donor has to travel.”

The first kidney exchange in the state of Ohio was performed in early November 2004. The third was scheduled for mid-April.

Creating one system to be shared by medical institutions that would normally be competitors took some work. “Trying to get us all to play in the same sandbox was very difficult,” Rees acknowledges. “But we did that; we stuck it out. And we all agreed to come up with something that we all think is a great idea and should help our patients.”