User login

Meet the Pregnancy Challenges of Women With Chronic Conditions

Preconception and prenatal care are more complicated in women with chronic health conditions but attention to disease management and promoting the adoption of a healthier lifestyle can improve outcomes for mothers and infants, according to a growing body of research.

The latest version of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Preconception Checklist, published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, highlights preexisting chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, lupus, and obesity as key factors to address in preconception care through disease management. A growing number of studies support the impact of these strategies on short- and long-term outcomes for mothers and babies, according to the authors.

Meet Glycemic Control Goals Prior to Pregnancy

“Women with diabetes can have healthy pregnancies but need to prepare for pregnancy in advance,” Ellen W. Seely, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical research in the endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension division of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“If glucose levels are running high in the first trimester, this is associated with an increased risk of birth defects, some of which are very serious,” said Dr. Seely. Getting glucose levels under control reduces the risk of birth defects in women with diabetes close to that of the general population, she said.

The American Diabetes Association has set a goal for women to attain an HbA1c of less than 6.5% before conception, Dr. Seely said. “In addition, some women with diabetes may be on medications that should be changed to another class prior to pregnancy,” she noted. Women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes often have hypertension as well, but ACE inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of fetal renal damage that can result in neonatal death; therefore, these medications should be stopped prior to pregnancy, Dr. Seely emphasized.

“If a woman with type 2 diabetes is on medications other than insulin, recommendations from the ADA are to change to insulin prior to pregnancy, since we have the most data on the safety profile of insulin use in pregnancy,” she said.

To help women with diabetes improve glycemic control prior to pregnancy, Dr. Seely recommends home glucose monitoring, with checks of glucose four times a day, fasting, and 2 hours after each meal, and adjustment of insulin accordingly.

A healthy diet and physical activity remain important components of glycemic control as well. A barrier to proper preconception and prenatal care for women with diabetes is not knowing that a pregnancy should be planned, Dr. Seely said. Discussions about pregnancy should start at puberty for women with diabetes, according to the ADA, and the topic should be raised yearly so women can optimize their health and adjust medications prior to conception.

Although studies of drugs have been done to inform preconception care for women with diabetes, research is lacking in several areas, notably the safety of GLP-1 agonists in pregnancy, said Dr. Seely. “This class of drug is commonly used in type 2 diabetes and the current recommendation is to stop these agents 2 months prior to conception,” she said.

Conceive in Times of Lupus Remission

Advance planning also is important for a healthy pregnancy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sayna Norouzi, MD, director of the glomerular disease clinic and polycystic kidney disease clinic of Loma Linda University Medical Center, California, said in an interview.

“Lupus mostly affects women of childbearing age and can create many challenges during pregnancy,” said Dr. Norouzi, the corresponding author of a recent review on managing lupus nephritis during pregnancy.

“Women with lupus face an increased risk of pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, problems with fetal growth, stillbirth, and premature birth, and these risks increase based on factors such as disease activity, certain antibodies in the body, and other baseline existing conditions such as high blood pressure,” she said.

“It can be difficult to distinguish between a lupus flare and pregnancy-related issues, so proper management is important,” she noted. The Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (PROMISSE) study findings indicated a lupus nephritis relapse rate of 7.8% of patients in complete remission and 21% of those in partial remission during pregnancy, said Dr. Norouzi. “Current evidence has shown that SLE patients without lupus nephritis flare in the preconception period have a small risk of relapse during pregnancy,” she said.

Before and during pregnancy, women with lupus should work with their treating physicians to adjust medications for safety, watch for signs of flare, and aim to conceive during a period of lupus remission.

Preconception care for women with lupus nephritis involves a careful review of the medications used to control the disease and protect the kidneys and other organs, said Dr. Norouzi.

“Adjustments,” she said, “should be personalized, taking into account the mother’s health and the safety of the baby. Managing the disease actively during pregnancy may require changes to the treatment plan while minimizing risks,” she noted. However, changing medications can cause challenges for patients, as medications that are safer for pregnancy may lead to new symptoms and side effects, and patients will need to work closely with their healthcare providers to overcome new issues that arise, she added.

Preconception lifestyle changes such as increasing exercise and adopting a healthier diet can help with blood pressure control for kidney disease patients, said Dr. Norouzi.

In the review article, Dr. Norouzi and colleagues noted that preconception counseling for patients with lupus should address common comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia, and the risk for immediate and long-term cardiovascular complications.

Benefits of Preconception Obesity Care Extend to Infants

Current guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Institute of Medicine advise lifestyle interventions to reduce excessive weight gain during pregnancy and reduce the risk of inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and lipotoxicity that can promote complications in the mother and fetus during pregnancy.

In addition, a growing number of studies suggest that women with obesity who make healthy lifestyle changes prior to conception can reduce obesity-associated risks to their infants.

Adults born to women with obesity are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and early signs of heart remodeling are identifiable in newborns, Samuel J. Burden, PhD, a research associate in the department of women and children’s health, Kings’ College, London, said in an interview. “It is therefore important to investigate whether intervening either before or during pregnancy by promoting a healthy lifestyle can reduce this adverse impact on the heart and blood vessels,” he said.

In a recent study published in the International Journal of Obesity, Dr. Burden and colleagues examined data from eight studies based on data from five randomized, controlled trials including children of mothers with obesity who engaged in healthy lifestyle interventions of improved diet and increased physical activity prior to and during pregnancy. The study population included children ranging in age from less than 2 months to 3-7 years.

Lifestyle interventions for mothers both before conception and during pregnancy were associated with significant changes in cardiac remodeling in the children, notably reduced interventricular septal wall thickness. Additionally, five studies of cardiac systolic function and three studies of diastolic function showed improvement in blood pressure in children of mothers who took part in the interventions.

Dr. Burden acknowledged that lifestyle changes in women with obesity before conception and during pregnancy can be challenging, but should be encouraged. “During pregnancy, it may also seem unnatural to increase daily physical activity or change the way you are eating.” He emphasized that patients should consult their physicians and follow an established program. More randomized, controlled trials are needed from the preconception period to examine whether the health benefits are greater if the intervention begins prior to pregnancy, said Dr. Burden. However, “the current findings indeed indicate that women with obesity who lead a healthy lifestyle before and during their pregnancy can reduce the degree of unhealthy heart remodeling in their children,” he said.

Dr. Seely, Dr. Norouzi, and Dr. Burden had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Preconception and prenatal care are more complicated in women with chronic health conditions but attention to disease management and promoting the adoption of a healthier lifestyle can improve outcomes for mothers and infants, according to a growing body of research.

The latest version of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Preconception Checklist, published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, highlights preexisting chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, lupus, and obesity as key factors to address in preconception care through disease management. A growing number of studies support the impact of these strategies on short- and long-term outcomes for mothers and babies, according to the authors.

Meet Glycemic Control Goals Prior to Pregnancy

“Women with diabetes can have healthy pregnancies but need to prepare for pregnancy in advance,” Ellen W. Seely, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical research in the endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension division of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“If glucose levels are running high in the first trimester, this is associated with an increased risk of birth defects, some of which are very serious,” said Dr. Seely. Getting glucose levels under control reduces the risk of birth defects in women with diabetes close to that of the general population, she said.

The American Diabetes Association has set a goal for women to attain an HbA1c of less than 6.5% before conception, Dr. Seely said. “In addition, some women with diabetes may be on medications that should be changed to another class prior to pregnancy,” she noted. Women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes often have hypertension as well, but ACE inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of fetal renal damage that can result in neonatal death; therefore, these medications should be stopped prior to pregnancy, Dr. Seely emphasized.

“If a woman with type 2 diabetes is on medications other than insulin, recommendations from the ADA are to change to insulin prior to pregnancy, since we have the most data on the safety profile of insulin use in pregnancy,” she said.

To help women with diabetes improve glycemic control prior to pregnancy, Dr. Seely recommends home glucose monitoring, with checks of glucose four times a day, fasting, and 2 hours after each meal, and adjustment of insulin accordingly.

A healthy diet and physical activity remain important components of glycemic control as well. A barrier to proper preconception and prenatal care for women with diabetes is not knowing that a pregnancy should be planned, Dr. Seely said. Discussions about pregnancy should start at puberty for women with diabetes, according to the ADA, and the topic should be raised yearly so women can optimize their health and adjust medications prior to conception.

Although studies of drugs have been done to inform preconception care for women with diabetes, research is lacking in several areas, notably the safety of GLP-1 agonists in pregnancy, said Dr. Seely. “This class of drug is commonly used in type 2 diabetes and the current recommendation is to stop these agents 2 months prior to conception,” she said.

Conceive in Times of Lupus Remission

Advance planning also is important for a healthy pregnancy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sayna Norouzi, MD, director of the glomerular disease clinic and polycystic kidney disease clinic of Loma Linda University Medical Center, California, said in an interview.

“Lupus mostly affects women of childbearing age and can create many challenges during pregnancy,” said Dr. Norouzi, the corresponding author of a recent review on managing lupus nephritis during pregnancy.

“Women with lupus face an increased risk of pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, problems with fetal growth, stillbirth, and premature birth, and these risks increase based on factors such as disease activity, certain antibodies in the body, and other baseline existing conditions such as high blood pressure,” she said.

“It can be difficult to distinguish between a lupus flare and pregnancy-related issues, so proper management is important,” she noted. The Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (PROMISSE) study findings indicated a lupus nephritis relapse rate of 7.8% of patients in complete remission and 21% of those in partial remission during pregnancy, said Dr. Norouzi. “Current evidence has shown that SLE patients without lupus nephritis flare in the preconception period have a small risk of relapse during pregnancy,” she said.

Before and during pregnancy, women with lupus should work with their treating physicians to adjust medications for safety, watch for signs of flare, and aim to conceive during a period of lupus remission.

Preconception care for women with lupus nephritis involves a careful review of the medications used to control the disease and protect the kidneys and other organs, said Dr. Norouzi.

“Adjustments,” she said, “should be personalized, taking into account the mother’s health and the safety of the baby. Managing the disease actively during pregnancy may require changes to the treatment plan while minimizing risks,” she noted. However, changing medications can cause challenges for patients, as medications that are safer for pregnancy may lead to new symptoms and side effects, and patients will need to work closely with their healthcare providers to overcome new issues that arise, she added.

Preconception lifestyle changes such as increasing exercise and adopting a healthier diet can help with blood pressure control for kidney disease patients, said Dr. Norouzi.

In the review article, Dr. Norouzi and colleagues noted that preconception counseling for patients with lupus should address common comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia, and the risk for immediate and long-term cardiovascular complications.

Benefits of Preconception Obesity Care Extend to Infants

Current guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Institute of Medicine advise lifestyle interventions to reduce excessive weight gain during pregnancy and reduce the risk of inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and lipotoxicity that can promote complications in the mother and fetus during pregnancy.

In addition, a growing number of studies suggest that women with obesity who make healthy lifestyle changes prior to conception can reduce obesity-associated risks to their infants.

Adults born to women with obesity are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and early signs of heart remodeling are identifiable in newborns, Samuel J. Burden, PhD, a research associate in the department of women and children’s health, Kings’ College, London, said in an interview. “It is therefore important to investigate whether intervening either before or during pregnancy by promoting a healthy lifestyle can reduce this adverse impact on the heart and blood vessels,” he said.

In a recent study published in the International Journal of Obesity, Dr. Burden and colleagues examined data from eight studies based on data from five randomized, controlled trials including children of mothers with obesity who engaged in healthy lifestyle interventions of improved diet and increased physical activity prior to and during pregnancy. The study population included children ranging in age from less than 2 months to 3-7 years.

Lifestyle interventions for mothers both before conception and during pregnancy were associated with significant changes in cardiac remodeling in the children, notably reduced interventricular septal wall thickness. Additionally, five studies of cardiac systolic function and three studies of diastolic function showed improvement in blood pressure in children of mothers who took part in the interventions.

Dr. Burden acknowledged that lifestyle changes in women with obesity before conception and during pregnancy can be challenging, but should be encouraged. “During pregnancy, it may also seem unnatural to increase daily physical activity or change the way you are eating.” He emphasized that patients should consult their physicians and follow an established program. More randomized, controlled trials are needed from the preconception period to examine whether the health benefits are greater if the intervention begins prior to pregnancy, said Dr. Burden. However, “the current findings indeed indicate that women with obesity who lead a healthy lifestyle before and during their pregnancy can reduce the degree of unhealthy heart remodeling in their children,” he said.

Dr. Seely, Dr. Norouzi, and Dr. Burden had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Preconception and prenatal care are more complicated in women with chronic health conditions but attention to disease management and promoting the adoption of a healthier lifestyle can improve outcomes for mothers and infants, according to a growing body of research.

The latest version of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Preconception Checklist, published in the International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, highlights preexisting chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, lupus, and obesity as key factors to address in preconception care through disease management. A growing number of studies support the impact of these strategies on short- and long-term outcomes for mothers and babies, according to the authors.

Meet Glycemic Control Goals Prior to Pregnancy

“Women with diabetes can have healthy pregnancies but need to prepare for pregnancy in advance,” Ellen W. Seely, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical research in the endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension division of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“If glucose levels are running high in the first trimester, this is associated with an increased risk of birth defects, some of which are very serious,” said Dr. Seely. Getting glucose levels under control reduces the risk of birth defects in women with diabetes close to that of the general population, she said.

The American Diabetes Association has set a goal for women to attain an HbA1c of less than 6.5% before conception, Dr. Seely said. “In addition, some women with diabetes may be on medications that should be changed to another class prior to pregnancy,” she noted. Women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes often have hypertension as well, but ACE inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of fetal renal damage that can result in neonatal death; therefore, these medications should be stopped prior to pregnancy, Dr. Seely emphasized.

“If a woman with type 2 diabetes is on medications other than insulin, recommendations from the ADA are to change to insulin prior to pregnancy, since we have the most data on the safety profile of insulin use in pregnancy,” she said.

To help women with diabetes improve glycemic control prior to pregnancy, Dr. Seely recommends home glucose monitoring, with checks of glucose four times a day, fasting, and 2 hours after each meal, and adjustment of insulin accordingly.

A healthy diet and physical activity remain important components of glycemic control as well. A barrier to proper preconception and prenatal care for women with diabetes is not knowing that a pregnancy should be planned, Dr. Seely said. Discussions about pregnancy should start at puberty for women with diabetes, according to the ADA, and the topic should be raised yearly so women can optimize their health and adjust medications prior to conception.

Although studies of drugs have been done to inform preconception care for women with diabetes, research is lacking in several areas, notably the safety of GLP-1 agonists in pregnancy, said Dr. Seely. “This class of drug is commonly used in type 2 diabetes and the current recommendation is to stop these agents 2 months prior to conception,” she said.

Conceive in Times of Lupus Remission

Advance planning also is important for a healthy pregnancy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sayna Norouzi, MD, director of the glomerular disease clinic and polycystic kidney disease clinic of Loma Linda University Medical Center, California, said in an interview.

“Lupus mostly affects women of childbearing age and can create many challenges during pregnancy,” said Dr. Norouzi, the corresponding author of a recent review on managing lupus nephritis during pregnancy.

“Women with lupus face an increased risk of pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, problems with fetal growth, stillbirth, and premature birth, and these risks increase based on factors such as disease activity, certain antibodies in the body, and other baseline existing conditions such as high blood pressure,” she said.

“It can be difficult to distinguish between a lupus flare and pregnancy-related issues, so proper management is important,” she noted. The Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (PROMISSE) study findings indicated a lupus nephritis relapse rate of 7.8% of patients in complete remission and 21% of those in partial remission during pregnancy, said Dr. Norouzi. “Current evidence has shown that SLE patients without lupus nephritis flare in the preconception period have a small risk of relapse during pregnancy,” she said.

Before and during pregnancy, women with lupus should work with their treating physicians to adjust medications for safety, watch for signs of flare, and aim to conceive during a period of lupus remission.

Preconception care for women with lupus nephritis involves a careful review of the medications used to control the disease and protect the kidneys and other organs, said Dr. Norouzi.

“Adjustments,” she said, “should be personalized, taking into account the mother’s health and the safety of the baby. Managing the disease actively during pregnancy may require changes to the treatment plan while minimizing risks,” she noted. However, changing medications can cause challenges for patients, as medications that are safer for pregnancy may lead to new symptoms and side effects, and patients will need to work closely with their healthcare providers to overcome new issues that arise, she added.

Preconception lifestyle changes such as increasing exercise and adopting a healthier diet can help with blood pressure control for kidney disease patients, said Dr. Norouzi.

In the review article, Dr. Norouzi and colleagues noted that preconception counseling for patients with lupus should address common comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia, and the risk for immediate and long-term cardiovascular complications.

Benefits of Preconception Obesity Care Extend to Infants

Current guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Institute of Medicine advise lifestyle interventions to reduce excessive weight gain during pregnancy and reduce the risk of inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and lipotoxicity that can promote complications in the mother and fetus during pregnancy.

In addition, a growing number of studies suggest that women with obesity who make healthy lifestyle changes prior to conception can reduce obesity-associated risks to their infants.

Adults born to women with obesity are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and early signs of heart remodeling are identifiable in newborns, Samuel J. Burden, PhD, a research associate in the department of women and children’s health, Kings’ College, London, said in an interview. “It is therefore important to investigate whether intervening either before or during pregnancy by promoting a healthy lifestyle can reduce this adverse impact on the heart and blood vessels,” he said.

In a recent study published in the International Journal of Obesity, Dr. Burden and colleagues examined data from eight studies based on data from five randomized, controlled trials including children of mothers with obesity who engaged in healthy lifestyle interventions of improved diet and increased physical activity prior to and during pregnancy. The study population included children ranging in age from less than 2 months to 3-7 years.

Lifestyle interventions for mothers both before conception and during pregnancy were associated with significant changes in cardiac remodeling in the children, notably reduced interventricular septal wall thickness. Additionally, five studies of cardiac systolic function and three studies of diastolic function showed improvement in blood pressure in children of mothers who took part in the interventions.

Dr. Burden acknowledged that lifestyle changes in women with obesity before conception and during pregnancy can be challenging, but should be encouraged. “During pregnancy, it may also seem unnatural to increase daily physical activity or change the way you are eating.” He emphasized that patients should consult their physicians and follow an established program. More randomized, controlled trials are needed from the preconception period to examine whether the health benefits are greater if the intervention begins prior to pregnancy, said Dr. Burden. However, “the current findings indeed indicate that women with obesity who lead a healthy lifestyle before and during their pregnancy can reduce the degree of unhealthy heart remodeling in their children,” he said.

Dr. Seely, Dr. Norouzi, and Dr. Burden had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Expanding Use of GLP-1 RAs for Weight Management

To discuss issues related to counseling patients about weight loss with glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), I recently posted a case from my own practice. This was a 44-year-old woman with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obesity who wanted to try to lose weight with a GLP-1 RA, having been unsuccessful in maintaining a normal weight with lifestyle change alone.

I am very happy to see a high number of favorable responses to this article, and I also recognize that it was very focused on GLP-1 RA therapy while not addressing the multivariate treatment of obesity.

A healthy lifestyle remains foundational for the management of obesity, and clinicians should guide patients to make constructive choices regarding their diet, physical activity, mental health, and sleep. However, like for our patient introduced in that article, lifestyle changes are rarely sufficient to obtain a goal of sustained weight loss that promotes better health outcomes. A meta-analysis of clinical trials testing lifestyle interventions to lose weight among adults with overweight and obesity found that the relative reduction in body weight in the intervention vs control cohorts was −3.63 kg at 1 year and −2.45 kg at 3 years. More intensive programs with at least 28 interventions per year were associated with slightly more weight loss than less intensive programs.

That is why clinicians and patients have been reaching for effective pharmacotherapy to create better outcomes among adults with obesity. In a national survey of 1479 US adults, 12% reported having used a GLP-1 RA. Diabetes was the most common indication (43%), followed by heart disease (26%) and overweight/obesity (22%).

The high cost of GLP-1 RA therapy was a major barrier to even wider use. Some 54% of participants said that it was difficult to afford GLP-1 RA therapy, and an additional 22% found it very difficult to pay for the drugs. Having health insurance did not alter these figures substantially.

While cost and access remain some of the greatest challenges with the use of GLP-1 RAs, there is hope for change there. In March 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration approved semaglutide to reduce the risk for cardiovascular events among patients with overweight and obesity and existing cardiovascular disease. It appears that Medicare will cover semaglutide for that indication, which bucks a trend of more than 20 years during which Medicare Part D would not cover pharmacotherapy for weight loss.

There is bipartisan support in the US Congress to further increase coverage of GLP-1 RAs for obesity, which makes sense. GLP-1 RAs are associated with greater average weight loss than either lifestyle interventions alone or that associated with previous anti-obesity medications. While there are no safety data for these drugs stretching back for 50 or 100 years, clinicians should bear in mind that exenatide was approved for the management of type 2 diabetes in 2005. So, we are approaching two decades of practical experience with these drugs, and it appears clear that the benefits of GLP-1 RAs outweigh any known harms. For the right patient, and with the right kind of guidance by clinicians, GLP-1 RA therapy can have a profound effect on individual and public health.

Dr. Vega, health sciences clinical professor, Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, disclosed ties with McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To discuss issues related to counseling patients about weight loss with glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), I recently posted a case from my own practice. This was a 44-year-old woman with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obesity who wanted to try to lose weight with a GLP-1 RA, having been unsuccessful in maintaining a normal weight with lifestyle change alone.

I am very happy to see a high number of favorable responses to this article, and I also recognize that it was very focused on GLP-1 RA therapy while not addressing the multivariate treatment of obesity.

A healthy lifestyle remains foundational for the management of obesity, and clinicians should guide patients to make constructive choices regarding their diet, physical activity, mental health, and sleep. However, like for our patient introduced in that article, lifestyle changes are rarely sufficient to obtain a goal of sustained weight loss that promotes better health outcomes. A meta-analysis of clinical trials testing lifestyle interventions to lose weight among adults with overweight and obesity found that the relative reduction in body weight in the intervention vs control cohorts was −3.63 kg at 1 year and −2.45 kg at 3 years. More intensive programs with at least 28 interventions per year were associated with slightly more weight loss than less intensive programs.

That is why clinicians and patients have been reaching for effective pharmacotherapy to create better outcomes among adults with obesity. In a national survey of 1479 US adults, 12% reported having used a GLP-1 RA. Diabetes was the most common indication (43%), followed by heart disease (26%) and overweight/obesity (22%).

The high cost of GLP-1 RA therapy was a major barrier to even wider use. Some 54% of participants said that it was difficult to afford GLP-1 RA therapy, and an additional 22% found it very difficult to pay for the drugs. Having health insurance did not alter these figures substantially.

While cost and access remain some of the greatest challenges with the use of GLP-1 RAs, there is hope for change there. In March 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration approved semaglutide to reduce the risk for cardiovascular events among patients with overweight and obesity and existing cardiovascular disease. It appears that Medicare will cover semaglutide for that indication, which bucks a trend of more than 20 years during which Medicare Part D would not cover pharmacotherapy for weight loss.

There is bipartisan support in the US Congress to further increase coverage of GLP-1 RAs for obesity, which makes sense. GLP-1 RAs are associated with greater average weight loss than either lifestyle interventions alone or that associated with previous anti-obesity medications. While there are no safety data for these drugs stretching back for 50 or 100 years, clinicians should bear in mind that exenatide was approved for the management of type 2 diabetes in 2005. So, we are approaching two decades of practical experience with these drugs, and it appears clear that the benefits of GLP-1 RAs outweigh any known harms. For the right patient, and with the right kind of guidance by clinicians, GLP-1 RA therapy can have a profound effect on individual and public health.

Dr. Vega, health sciences clinical professor, Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, disclosed ties with McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To discuss issues related to counseling patients about weight loss with glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), I recently posted a case from my own practice. This was a 44-year-old woman with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obesity who wanted to try to lose weight with a GLP-1 RA, having been unsuccessful in maintaining a normal weight with lifestyle change alone.

I am very happy to see a high number of favorable responses to this article, and I also recognize that it was very focused on GLP-1 RA therapy while not addressing the multivariate treatment of obesity.

A healthy lifestyle remains foundational for the management of obesity, and clinicians should guide patients to make constructive choices regarding their diet, physical activity, mental health, and sleep. However, like for our patient introduced in that article, lifestyle changes are rarely sufficient to obtain a goal of sustained weight loss that promotes better health outcomes. A meta-analysis of clinical trials testing lifestyle interventions to lose weight among adults with overweight and obesity found that the relative reduction in body weight in the intervention vs control cohorts was −3.63 kg at 1 year and −2.45 kg at 3 years. More intensive programs with at least 28 interventions per year were associated with slightly more weight loss than less intensive programs.

That is why clinicians and patients have been reaching for effective pharmacotherapy to create better outcomes among adults with obesity. In a national survey of 1479 US adults, 12% reported having used a GLP-1 RA. Diabetes was the most common indication (43%), followed by heart disease (26%) and overweight/obesity (22%).

The high cost of GLP-1 RA therapy was a major barrier to even wider use. Some 54% of participants said that it was difficult to afford GLP-1 RA therapy, and an additional 22% found it very difficult to pay for the drugs. Having health insurance did not alter these figures substantially.

While cost and access remain some of the greatest challenges with the use of GLP-1 RAs, there is hope for change there. In March 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration approved semaglutide to reduce the risk for cardiovascular events among patients with overweight and obesity and existing cardiovascular disease. It appears that Medicare will cover semaglutide for that indication, which bucks a trend of more than 20 years during which Medicare Part D would not cover pharmacotherapy for weight loss.

There is bipartisan support in the US Congress to further increase coverage of GLP-1 RAs for obesity, which makes sense. GLP-1 RAs are associated with greater average weight loss than either lifestyle interventions alone or that associated with previous anti-obesity medications. While there are no safety data for these drugs stretching back for 50 or 100 years, clinicians should bear in mind that exenatide was approved for the management of type 2 diabetes in 2005. So, we are approaching two decades of practical experience with these drugs, and it appears clear that the benefits of GLP-1 RAs outweigh any known harms. For the right patient, and with the right kind of guidance by clinicians, GLP-1 RA therapy can have a profound effect on individual and public health.

Dr. Vega, health sciences clinical professor, Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, disclosed ties with McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mounjaro Beats Ozempic, So Why Isn’t It More Popular?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s July, which means our hospital is filled with new interns, residents, and fellows all eager to embark on a new stage of their career. It’s an exciting time — a bit of a scary time — but it’s also the time when the medical strategies I’ve been taking for granted get called into question. At this point in the year, I tend to get a lot of “why” questions. Why did you order that test? Why did you suspect that diagnosis? Why did you choose that medication?

Meds are the hardest, I find. Sure, I can explain that I prescribed a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist because the patient had diabetes and was overweight, and multiple studies show that this class of drug leads to weight loss and reduced mortality risk. But then I get the follow-up: Sure, but why THAT GLP-1 drug? Why did you pick semaglutide (Ozempic) over tirzepatide (Mounjaro)?

Here’s where I run out of good answers. Sometimes I choose a drug because that’s what the patient’s insurance has on their formulary. Sometimes it’s because it’s cheaper in general. Sometimes, it’s just force of habit. I know the correct dose, I have experience with the side effects — it’s comfortable.

What I can’t say is that I have solid evidence that one drug is superior to another, say from a randomized trial of semaglutide vs tirzepatide. I don’t have that evidence because that trial has never happened and, as I’ll explain in a minute, may never happen at all.

But we might have the next best thing. And the results may surprise you.

Why don’t we see more head-to-head trials of competitor drugs? The answer is pretty simple, honestly: risk management. For drugs that are on patent, like the GLP-1s, conducting a trial without the buy-in of the pharmaceutical company is simply too expensive — we can’t run a trial unless someone provides the drug for free. That gives the companies a lot of say in what trials get done, and it seems that most pharma companies have reached the same conclusion: A head-to-head trial is too risky. Be happy with the market share you have, and try to nibble away at the edges through good old-fashioned marketing.

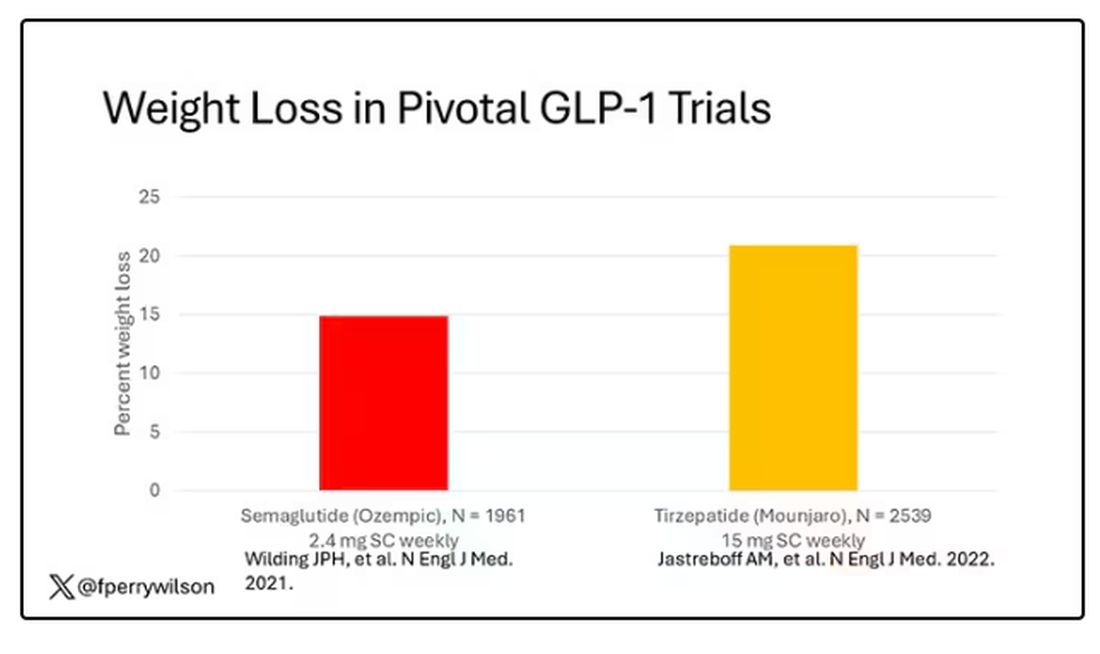

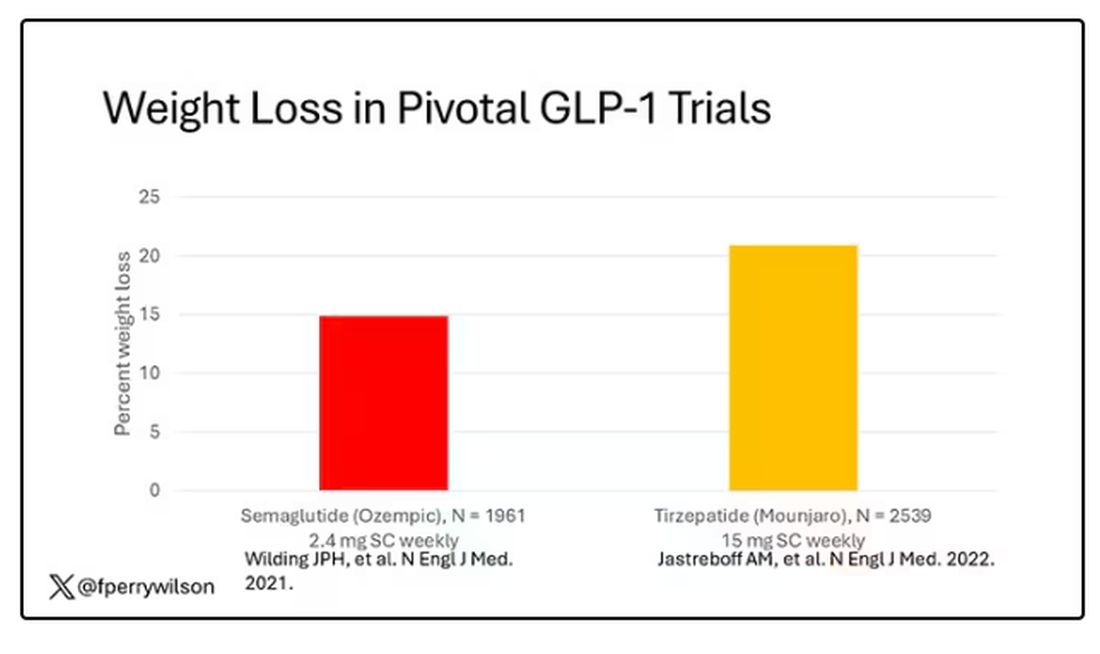

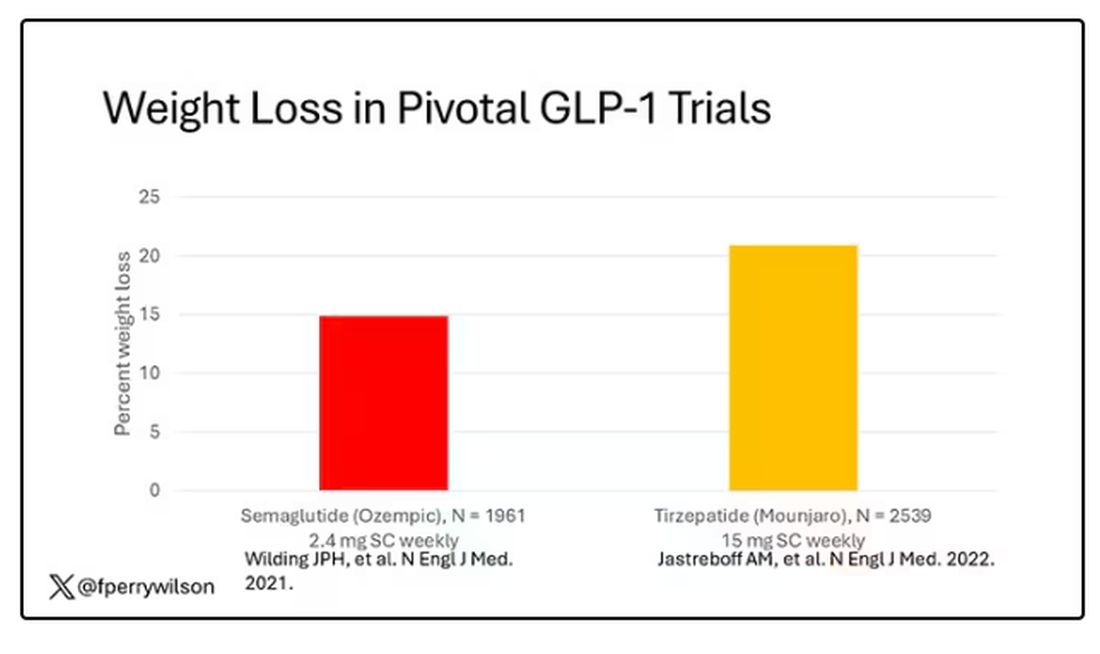

But if you look at the data that are out there, you might wonder why Ozempic is the market leader. I mean, sure, it’s a heck of a weight loss drug. But the weight loss in the trials of Mounjaro was actually a bit higher. It’s worth noting here that tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is not just a GLP-1 receptor agonist; it is also a gastric inhibitory polypeptide agonist.

But it’s very hard to compare the results of a trial pitting Ozempic against placebo with a totally different trial pitting Mounjaro against placebo. You can always argue that the patients studied were just too different at baseline — an apples and oranges situation.

Newly published, a study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine uses real-world data and propensity-score matching to turn oranges back into apples. I’ll walk you through it.

The data and analysis here come from Truveta, a collective of various US healthcare systems that share a broad swath of electronic health record data. Researchers identified 41,222 adults with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide between May 2022 and September 2023.

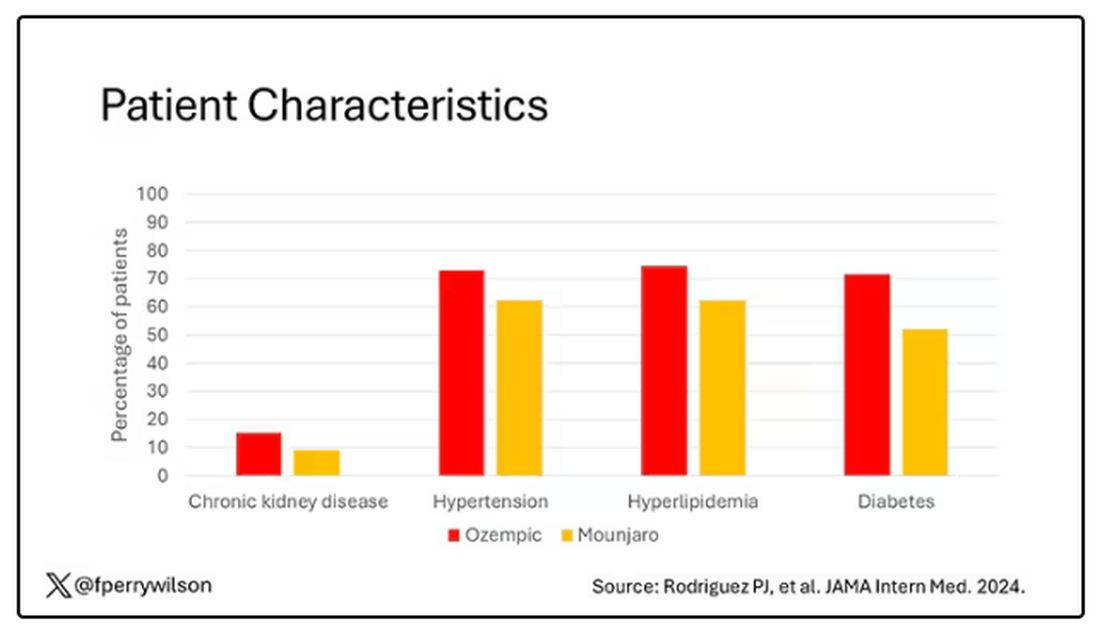

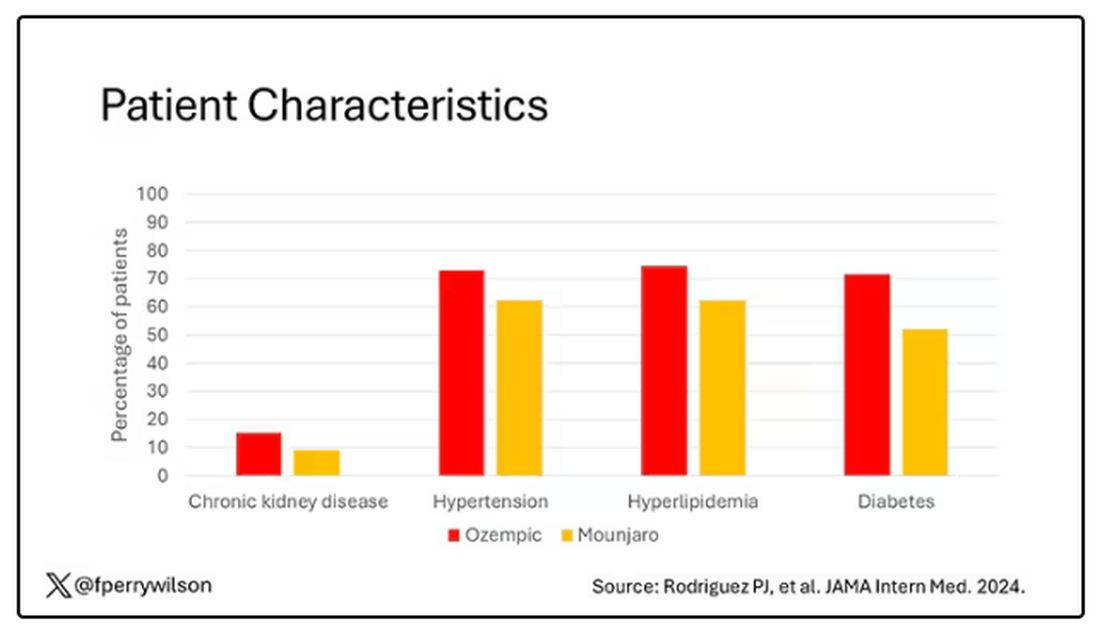

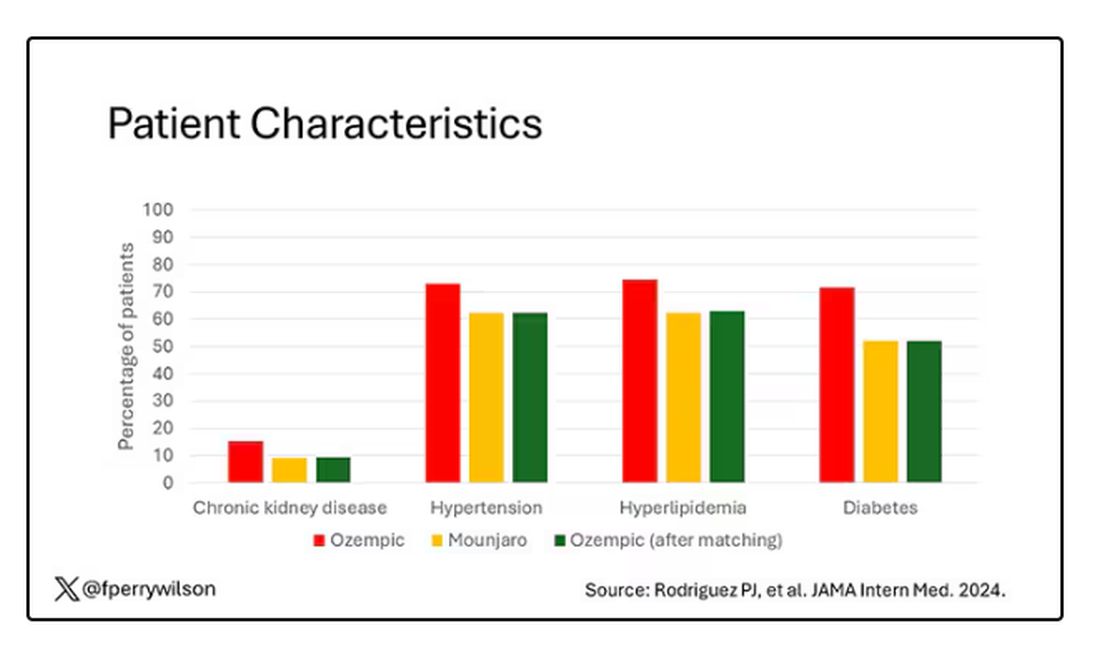

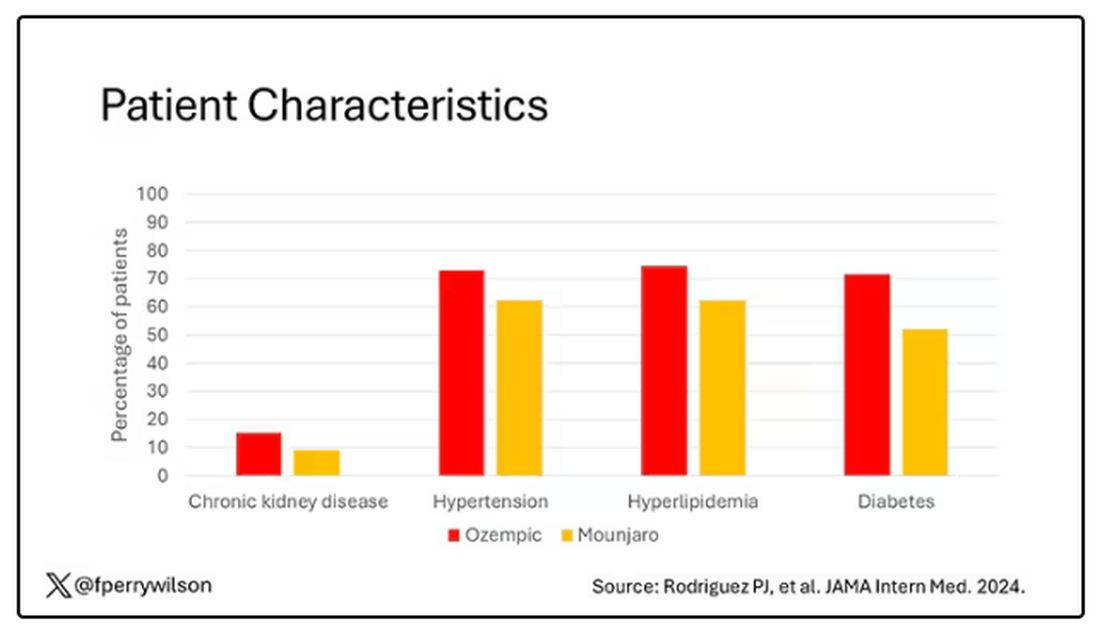

You’d be tempted to just see which group lost more weight over time, but that is the apples and oranges problem. People prescribed Mounjaro were different from people who were prescribed Ozempic. There are a variety of factors to look at here, but the vibe is that the Mounjaro group seems healthier at baseline. They were younger and had less kidney disease, less hypertension, and less hyperlipidemia. They had higher incomes and were more likely to be White. They were also dramatically less likely to have diabetes.

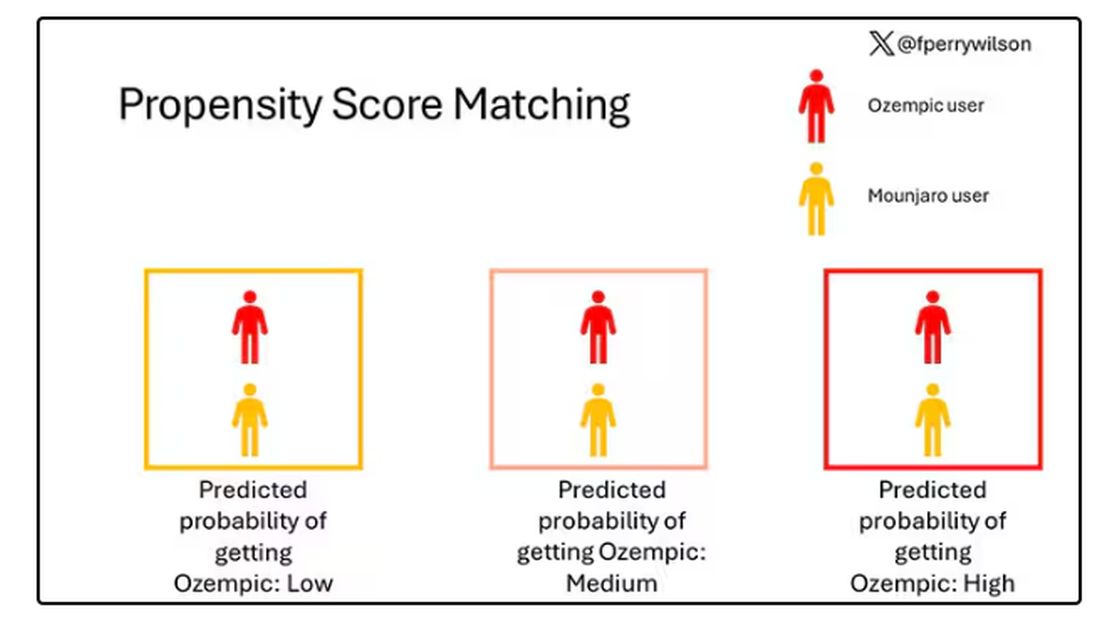

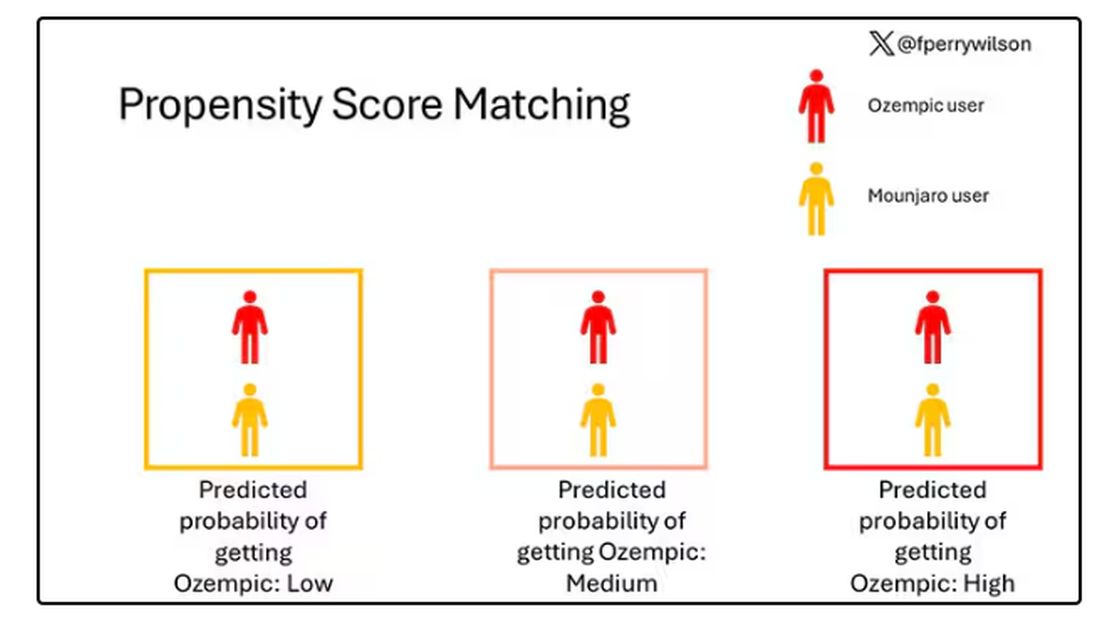

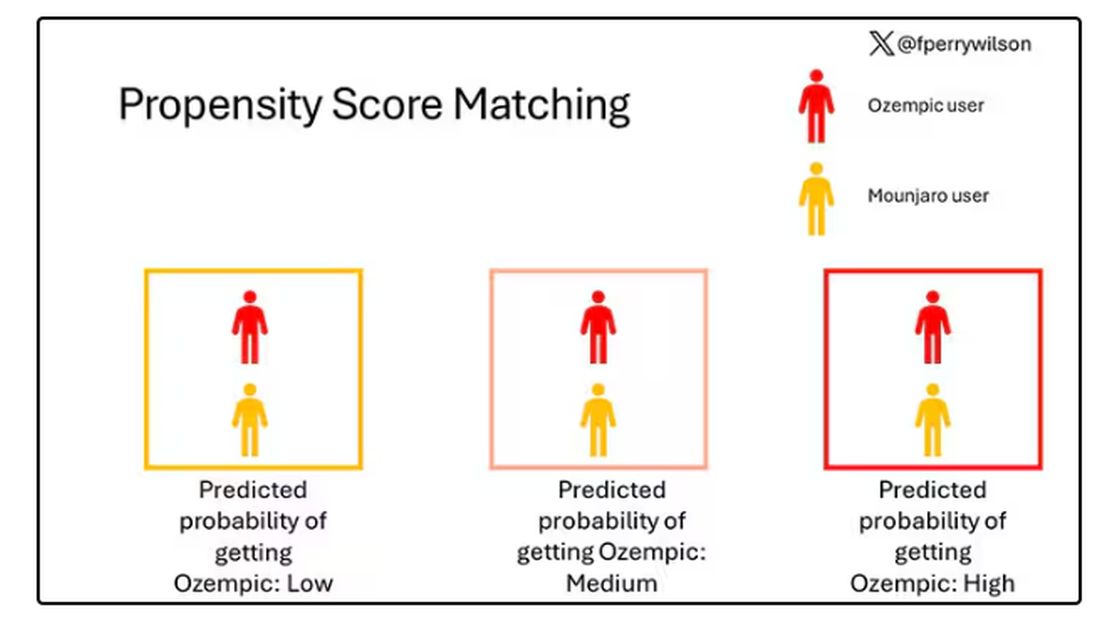

To account for this, the researchers used a statistical technique called propensity-score matching. Briefly, you create a model based on a variety of patient factors to predict who would be prescribed Ozempic and who would be prescribed Mounjaro. You then identify pairs of patients with similar probability (or propensity) of receiving, say, Ozempic, where one member of the pair got Ozempic and one got Mounjaro. Any unmatched individuals simply get dropped from the analysis.

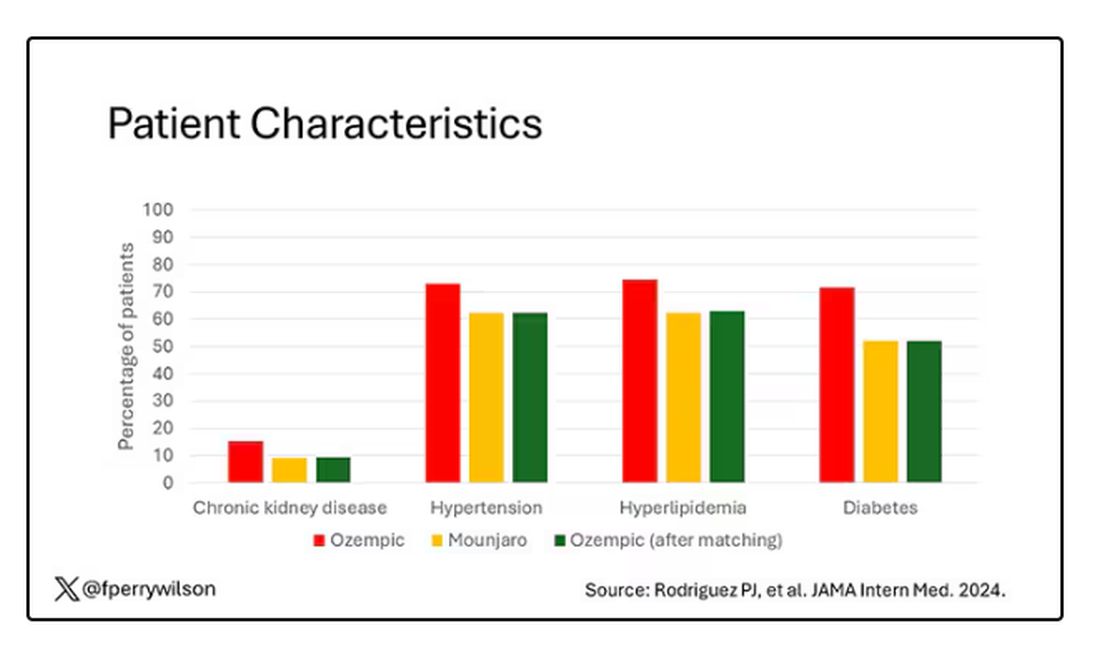

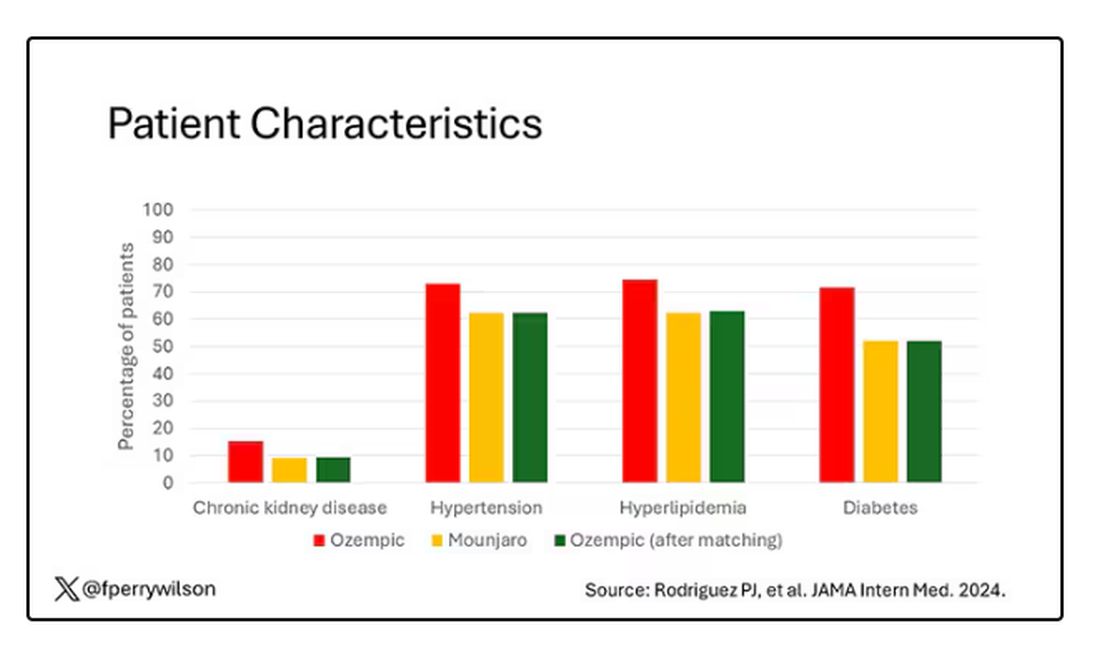

Thus, the researchers took the 41,222 individuals who started the analysis, of whom 9193 received Mounjaro, and identified the 9193 patients who got Ozempic that most closely matched the Mounjaro crowd. I know, it sounds confusing. But as an example, in the original dataset, 51.9% of those who got Mounjaro had diabetes compared with 71.5% of those who got Ozempic. Among the 9193 individuals who remained in the Ozempic group after matching, 52.1% had diabetes. By matching in this way, you balance your baseline characteristics. Turning apples into oranges. Or, maybe the better metaphor would be plucking the oranges out of a big pile of mostly apples.

Once that’s done, we can go back to do what we wanted to do in the beginning, which is to look at the weight loss between the groups.

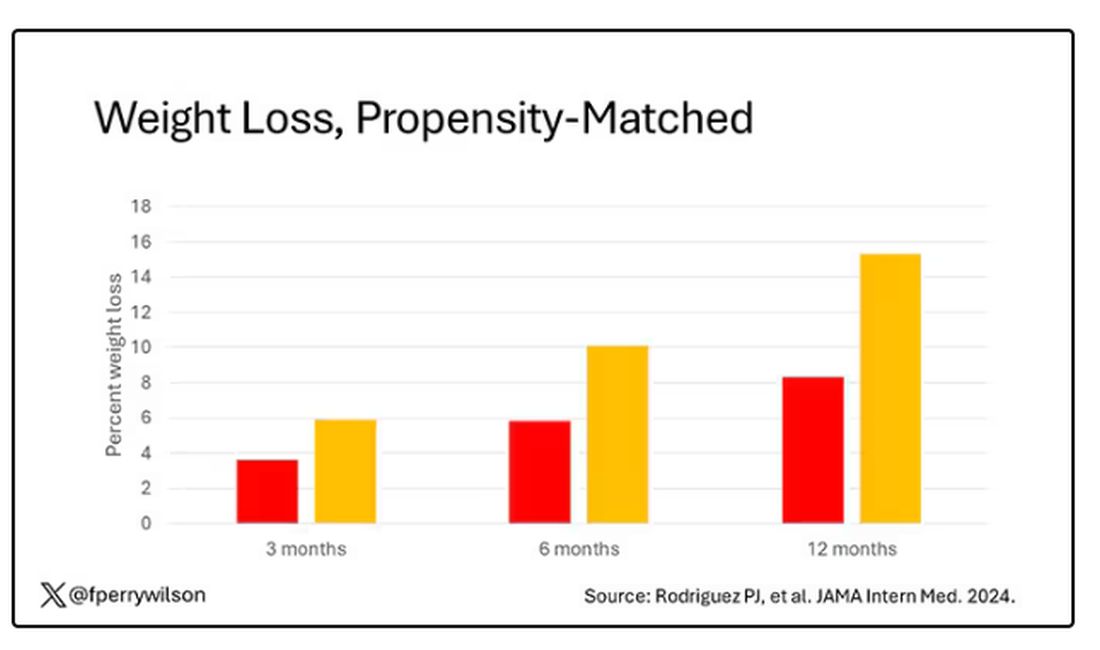

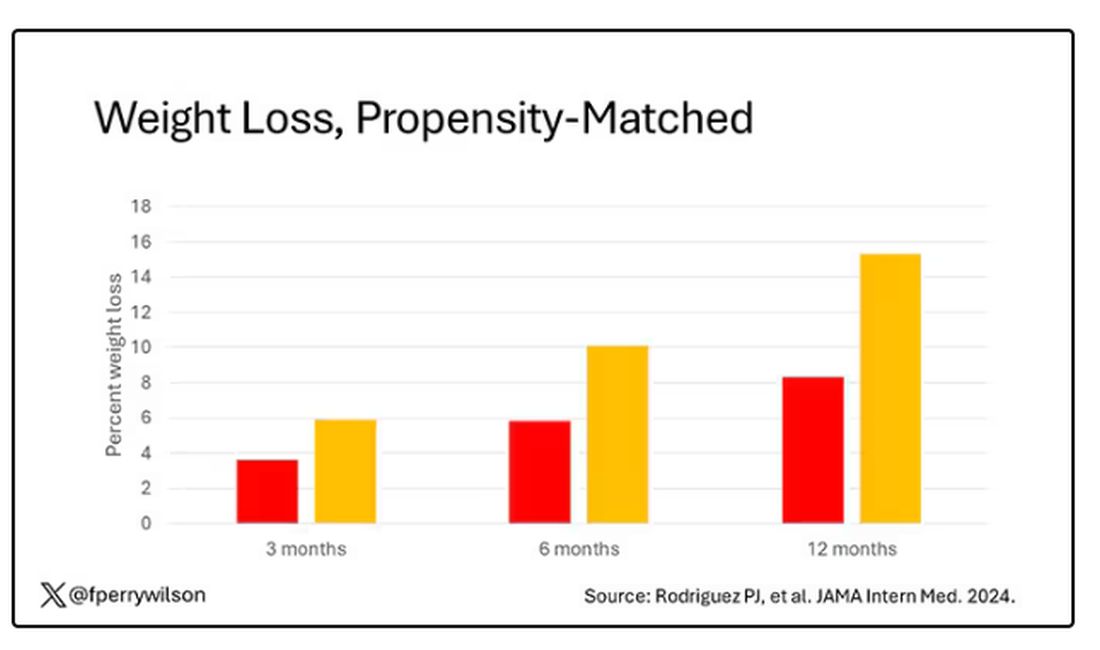

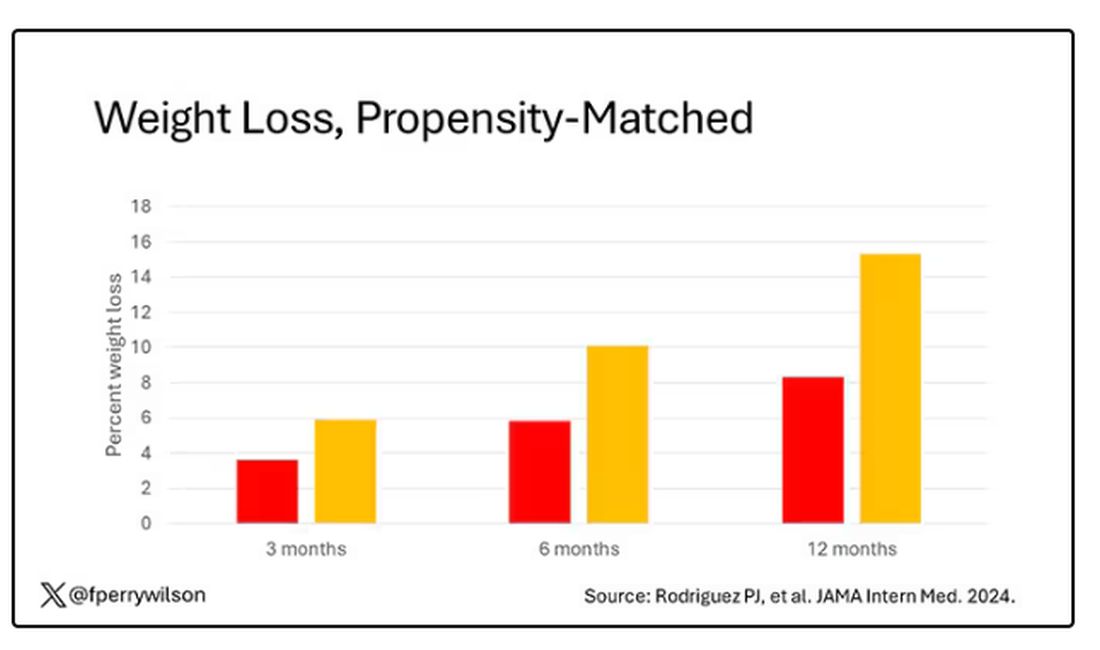

What I’m showing you here is the average percent change in body weight at 3, 6, and 12 months across the two drugs in the matched cohort. By a year out, you have basically 15% weight loss in the Mounjaro group compared with 8% or so in the Ozempic group.

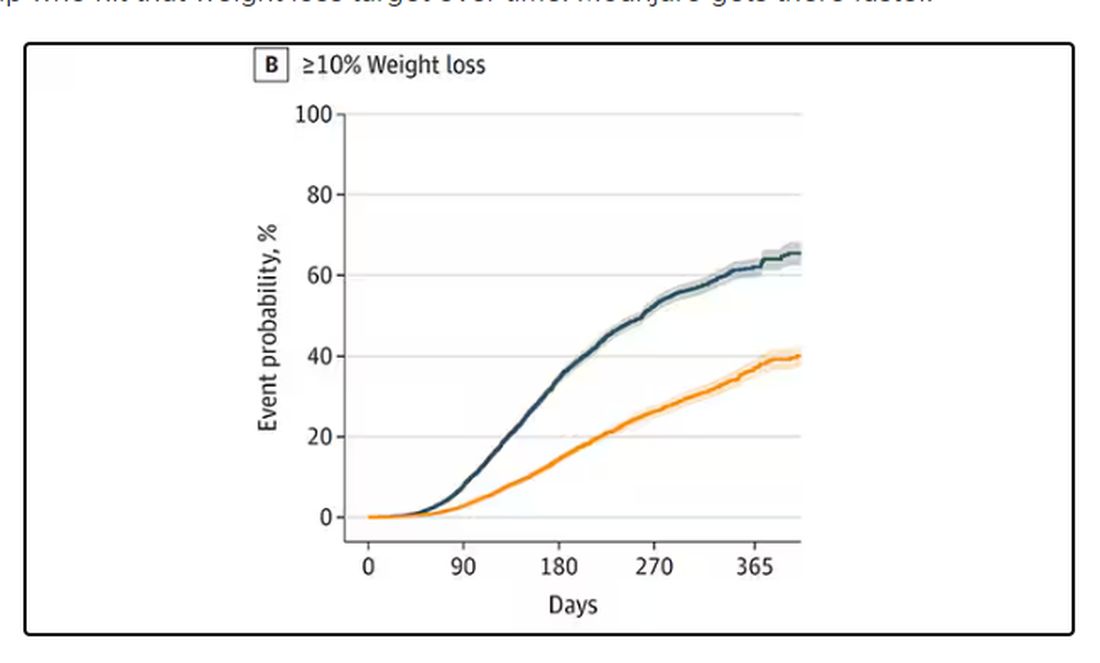

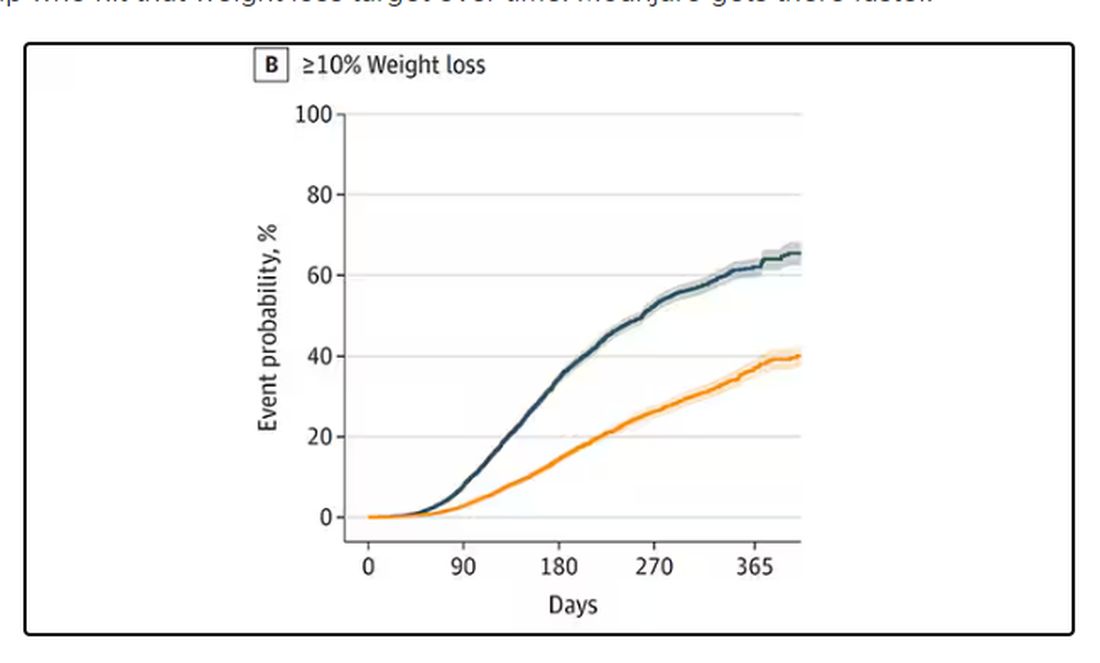

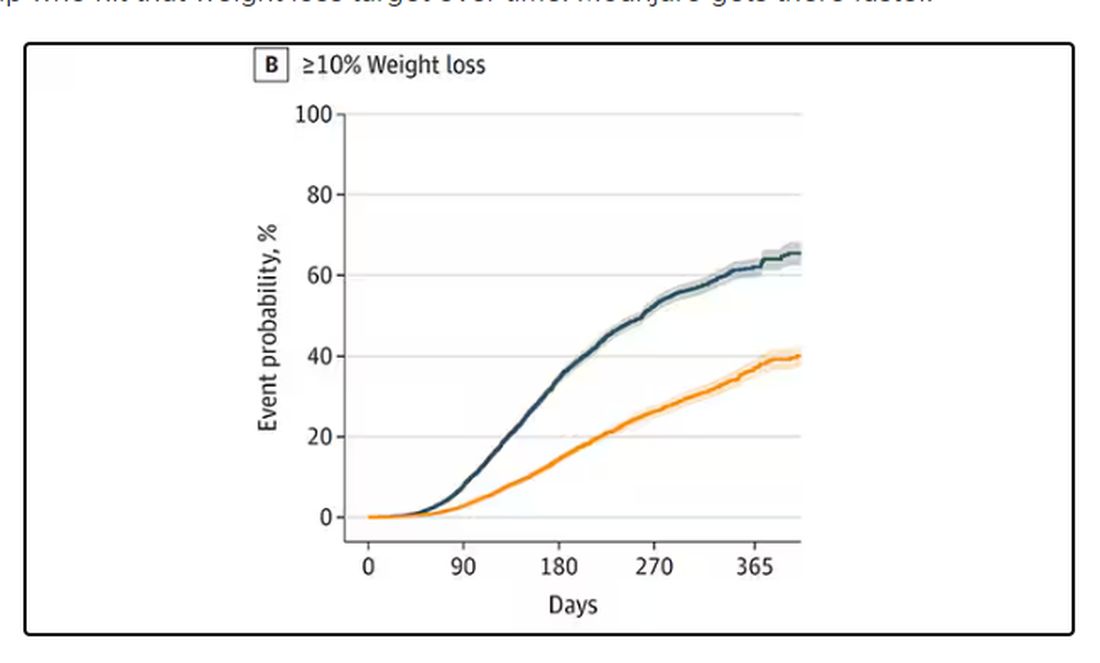

We can slice this a different way as well — asking what percent of people in each group achieve, say, 10% weight loss? This graph examines the percentage of each treatment group who hit that weight loss target over time. Mounjaro gets there faster.

I should point out that this was a so-called “on treatment” analysis: If people stopped taking either of the drugs, they were no longer included in the study. That tends to make drugs like this appear better than they are because as time goes on, you may weed out the people who stop the drug owing to lack of efficacy or to side effects. But in a sensitivity analysis, the authors see what happens if they just treat people as if they were taking the drug for the entire year once they had it prescribed, and the results, while not as dramatic, were broadly similar. Mounjaro still came out on top.

Adverse events— stuff like gastroparesis and pancreatitis — were rare, but rates were similar between the two groups.

It’s great to see studies like this that leverage real world data and a solid statistical underpinning to give us providers actionable information. Is it 100% definitive? No. But, especially considering the clinical trial data, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that Mounjaro seems to be the more effective weight loss agent. That said, we don’t actually live in a world where we can prescribe medications based on a silly little thing like which is the most effective. Especially given the cost of these agents — the patient’s insurance status is going to guide our prescription pen more than this study ever could. And of course, given the demand for this class of agents and the fact that both are actually quite effective, you may be best off prescribing whatever you can get your hands on.

But I’d like to see more of this. When I do have a choice of a medication, when costs and availability are similar, I’d like to be able to answer that question of “why did you choose that one?” with an evidence-based answer: “It’s better.”

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s July, which means our hospital is filled with new interns, residents, and fellows all eager to embark on a new stage of their career. It’s an exciting time — a bit of a scary time — but it’s also the time when the medical strategies I’ve been taking for granted get called into question. At this point in the year, I tend to get a lot of “why” questions. Why did you order that test? Why did you suspect that diagnosis? Why did you choose that medication?

Meds are the hardest, I find. Sure, I can explain that I prescribed a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist because the patient had diabetes and was overweight, and multiple studies show that this class of drug leads to weight loss and reduced mortality risk. But then I get the follow-up: Sure, but why THAT GLP-1 drug? Why did you pick semaglutide (Ozempic) over tirzepatide (Mounjaro)?

Here’s where I run out of good answers. Sometimes I choose a drug because that’s what the patient’s insurance has on their formulary. Sometimes it’s because it’s cheaper in general. Sometimes, it’s just force of habit. I know the correct dose, I have experience with the side effects — it’s comfortable.

What I can’t say is that I have solid evidence that one drug is superior to another, say from a randomized trial of semaglutide vs tirzepatide. I don’t have that evidence because that trial has never happened and, as I’ll explain in a minute, may never happen at all.

But we might have the next best thing. And the results may surprise you.

Why don’t we see more head-to-head trials of competitor drugs? The answer is pretty simple, honestly: risk management. For drugs that are on patent, like the GLP-1s, conducting a trial without the buy-in of the pharmaceutical company is simply too expensive — we can’t run a trial unless someone provides the drug for free. That gives the companies a lot of say in what trials get done, and it seems that most pharma companies have reached the same conclusion: A head-to-head trial is too risky. Be happy with the market share you have, and try to nibble away at the edges through good old-fashioned marketing.

But if you look at the data that are out there, you might wonder why Ozempic is the market leader. I mean, sure, it’s a heck of a weight loss drug. But the weight loss in the trials of Mounjaro was actually a bit higher. It’s worth noting here that tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is not just a GLP-1 receptor agonist; it is also a gastric inhibitory polypeptide agonist.

But it’s very hard to compare the results of a trial pitting Ozempic against placebo with a totally different trial pitting Mounjaro against placebo. You can always argue that the patients studied were just too different at baseline — an apples and oranges situation.

Newly published, a study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine uses real-world data and propensity-score matching to turn oranges back into apples. I’ll walk you through it.

The data and analysis here come from Truveta, a collective of various US healthcare systems that share a broad swath of electronic health record data. Researchers identified 41,222 adults with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide between May 2022 and September 2023.

You’d be tempted to just see which group lost more weight over time, but that is the apples and oranges problem. People prescribed Mounjaro were different from people who were prescribed Ozempic. There are a variety of factors to look at here, but the vibe is that the Mounjaro group seems healthier at baseline. They were younger and had less kidney disease, less hypertension, and less hyperlipidemia. They had higher incomes and were more likely to be White. They were also dramatically less likely to have diabetes.

To account for this, the researchers used a statistical technique called propensity-score matching. Briefly, you create a model based on a variety of patient factors to predict who would be prescribed Ozempic and who would be prescribed Mounjaro. You then identify pairs of patients with similar probability (or propensity) of receiving, say, Ozempic, where one member of the pair got Ozempic and one got Mounjaro. Any unmatched individuals simply get dropped from the analysis.

Thus, the researchers took the 41,222 individuals who started the analysis, of whom 9193 received Mounjaro, and identified the 9193 patients who got Ozempic that most closely matched the Mounjaro crowd. I know, it sounds confusing. But as an example, in the original dataset, 51.9% of those who got Mounjaro had diabetes compared with 71.5% of those who got Ozempic. Among the 9193 individuals who remained in the Ozempic group after matching, 52.1% had diabetes. By matching in this way, you balance your baseline characteristics. Turning apples into oranges. Or, maybe the better metaphor would be plucking the oranges out of a big pile of mostly apples.

Once that’s done, we can go back to do what we wanted to do in the beginning, which is to look at the weight loss between the groups.

What I’m showing you here is the average percent change in body weight at 3, 6, and 12 months across the two drugs in the matched cohort. By a year out, you have basically 15% weight loss in the Mounjaro group compared with 8% or so in the Ozempic group.

We can slice this a different way as well — asking what percent of people in each group achieve, say, 10% weight loss? This graph examines the percentage of each treatment group who hit that weight loss target over time. Mounjaro gets there faster.

I should point out that this was a so-called “on treatment” analysis: If people stopped taking either of the drugs, they were no longer included in the study. That tends to make drugs like this appear better than they are because as time goes on, you may weed out the people who stop the drug owing to lack of efficacy or to side effects. But in a sensitivity analysis, the authors see what happens if they just treat people as if they were taking the drug for the entire year once they had it prescribed, and the results, while not as dramatic, were broadly similar. Mounjaro still came out on top.

Adverse events— stuff like gastroparesis and pancreatitis — were rare, but rates were similar between the two groups.

It’s great to see studies like this that leverage real world data and a solid statistical underpinning to give us providers actionable information. Is it 100% definitive? No. But, especially considering the clinical trial data, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that Mounjaro seems to be the more effective weight loss agent. That said, we don’t actually live in a world where we can prescribe medications based on a silly little thing like which is the most effective. Especially given the cost of these agents — the patient’s insurance status is going to guide our prescription pen more than this study ever could. And of course, given the demand for this class of agents and the fact that both are actually quite effective, you may be best off prescribing whatever you can get your hands on.

But I’d like to see more of this. When I do have a choice of a medication, when costs and availability are similar, I’d like to be able to answer that question of “why did you choose that one?” with an evidence-based answer: “It’s better.”

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s July, which means our hospital is filled with new interns, residents, and fellows all eager to embark on a new stage of their career. It’s an exciting time — a bit of a scary time — but it’s also the time when the medical strategies I’ve been taking for granted get called into question. At this point in the year, I tend to get a lot of “why” questions. Why did you order that test? Why did you suspect that diagnosis? Why did you choose that medication?

Meds are the hardest, I find. Sure, I can explain that I prescribed a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist because the patient had diabetes and was overweight, and multiple studies show that this class of drug leads to weight loss and reduced mortality risk. But then I get the follow-up: Sure, but why THAT GLP-1 drug? Why did you pick semaglutide (Ozempic) over tirzepatide (Mounjaro)?

Here’s where I run out of good answers. Sometimes I choose a drug because that’s what the patient’s insurance has on their formulary. Sometimes it’s because it’s cheaper in general. Sometimes, it’s just force of habit. I know the correct dose, I have experience with the side effects — it’s comfortable.

What I can’t say is that I have solid evidence that one drug is superior to another, say from a randomized trial of semaglutide vs tirzepatide. I don’t have that evidence because that trial has never happened and, as I’ll explain in a minute, may never happen at all.

But we might have the next best thing. And the results may surprise you.

Why don’t we see more head-to-head trials of competitor drugs? The answer is pretty simple, honestly: risk management. For drugs that are on patent, like the GLP-1s, conducting a trial without the buy-in of the pharmaceutical company is simply too expensive — we can’t run a trial unless someone provides the drug for free. That gives the companies a lot of say in what trials get done, and it seems that most pharma companies have reached the same conclusion: A head-to-head trial is too risky. Be happy with the market share you have, and try to nibble away at the edges through good old-fashioned marketing.

But if you look at the data that are out there, you might wonder why Ozempic is the market leader. I mean, sure, it’s a heck of a weight loss drug. But the weight loss in the trials of Mounjaro was actually a bit higher. It’s worth noting here that tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is not just a GLP-1 receptor agonist; it is also a gastric inhibitory polypeptide agonist.

But it’s very hard to compare the results of a trial pitting Ozempic against placebo with a totally different trial pitting Mounjaro against placebo. You can always argue that the patients studied were just too different at baseline — an apples and oranges situation.

Newly published, a study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine uses real-world data and propensity-score matching to turn oranges back into apples. I’ll walk you through it.

The data and analysis here come from Truveta, a collective of various US healthcare systems that share a broad swath of electronic health record data. Researchers identified 41,222 adults with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or tirzepatide between May 2022 and September 2023.

You’d be tempted to just see which group lost more weight over time, but that is the apples and oranges problem. People prescribed Mounjaro were different from people who were prescribed Ozempic. There are a variety of factors to look at here, but the vibe is that the Mounjaro group seems healthier at baseline. They were younger and had less kidney disease, less hypertension, and less hyperlipidemia. They had higher incomes and were more likely to be White. They were also dramatically less likely to have diabetes.

To account for this, the researchers used a statistical technique called propensity-score matching. Briefly, you create a model based on a variety of patient factors to predict who would be prescribed Ozempic and who would be prescribed Mounjaro. You then identify pairs of patients with similar probability (or propensity) of receiving, say, Ozempic, where one member of the pair got Ozempic and one got Mounjaro. Any unmatched individuals simply get dropped from the analysis.

Thus, the researchers took the 41,222 individuals who started the analysis, of whom 9193 received Mounjaro, and identified the 9193 patients who got Ozempic that most closely matched the Mounjaro crowd. I know, it sounds confusing. But as an example, in the original dataset, 51.9% of those who got Mounjaro had diabetes compared with 71.5% of those who got Ozempic. Among the 9193 individuals who remained in the Ozempic group after matching, 52.1% had diabetes. By matching in this way, you balance your baseline characteristics. Turning apples into oranges. Or, maybe the better metaphor would be plucking the oranges out of a big pile of mostly apples.

Once that’s done, we can go back to do what we wanted to do in the beginning, which is to look at the weight loss between the groups.

What I’m showing you here is the average percent change in body weight at 3, 6, and 12 months across the two drugs in the matched cohort. By a year out, you have basically 15% weight loss in the Mounjaro group compared with 8% or so in the Ozempic group.

We can slice this a different way as well — asking what percent of people in each group achieve, say, 10% weight loss? This graph examines the percentage of each treatment group who hit that weight loss target over time. Mounjaro gets there faster.

I should point out that this was a so-called “on treatment” analysis: If people stopped taking either of the drugs, they were no longer included in the study. That tends to make drugs like this appear better than they are because as time goes on, you may weed out the people who stop the drug owing to lack of efficacy or to side effects. But in a sensitivity analysis, the authors see what happens if they just treat people as if they were taking the drug for the entire year once they had it prescribed, and the results, while not as dramatic, were broadly similar. Mounjaro still came out on top.

Adverse events— stuff like gastroparesis and pancreatitis — were rare, but rates were similar between the two groups.

It’s great to see studies like this that leverage real world data and a solid statistical underpinning to give us providers actionable information. Is it 100% definitive? No. But, especially considering the clinical trial data, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that Mounjaro seems to be the more effective weight loss agent. That said, we don’t actually live in a world where we can prescribe medications based on a silly little thing like which is the most effective. Especially given the cost of these agents — the patient’s insurance status is going to guide our prescription pen more than this study ever could. And of course, given the demand for this class of agents and the fact that both are actually quite effective, you may be best off prescribing whatever you can get your hands on.

But I’d like to see more of this. When I do have a choice of a medication, when costs and availability are similar, I’d like to be able to answer that question of “why did you choose that one?” with an evidence-based answer: “It’s better.”

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Whether GLP-1 RAs Significantly Delay Gastric Emptying Called into Question

TOPLINE:

Patients taking a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) experience only a modest delay in gastric emptying of solid foods and no significant delay for liquids, compared with those receiving placebo, indicating that patients may not need to discontinue these medications before surgery.

METHODOLOGY:

- GLP-1 RAs, while effective in managing diabetes and obesity, are linked to delayed gastric emptying, which may pose risks during procedures requiring anesthesia or sedation due to potential aspiration of gastric contents.

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the duration of delay in gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 RAs in patients with diabetes and/or excessive body weight, which could guide periprocedural management decisions in the future.

- The primary outcome was halftime, the time required for 50% of solid gastric contents to empty, measured using scintigraphy. This analysis included data from five studies involving 247 patients who received either a GLP-1 RA or placebo.

- The secondary outcome was gastric emptying of liquids measured using the acetaminophen absorption test. Ten studies including 411 patients who received either a GLP-1 RA or placebo were included in this analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The mean gastric emptying halftime for solid foods was 138.4 minutes with a GLP-1 RA and 95.0 minutes with placebo, resulting in a pooled mean difference of 36.0 minutes (P < .01).

- Furthermore, the amount of gastric emptying noted at 4 or 5 hours on the acetaminophen absorption test was comparable between these groups.

- The gastric emptying time for both solids and liquids did not differ between GLP-1 RA formulations or between short-acting or long-acting GLP-1 RAs.

IN PRACTICE:

“Based on current evidence, a conservative approach with a liquid diet on the day before procedures while continuing GLP-1 RA therapy would represent the most sensible approach until more conclusive data on a solid diet are available,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Brent Hiramoto, MD, MPH, of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small number of studies utilizing some diagnostic modalities, such as breath testing, precluded a formal meta-analysis of these subgroups. The results could not be stratified by indication for GLP-1 RA (diabetes or obesity) because of insufficient studies in each category.

DISCLOSURES:

The lead author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author declared serving on the advisory boards of three pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients taking a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) experience only a modest delay in gastric emptying of solid foods and no significant delay for liquids, compared with those receiving placebo, indicating that patients may not need to discontinue these medications before surgery.

METHODOLOGY:

- GLP-1 RAs, while effective in managing diabetes and obesity, are linked to delayed gastric emptying, which may pose risks during procedures requiring anesthesia or sedation due to potential aspiration of gastric contents.

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the duration of delay in gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 RAs in patients with diabetes and/or excessive body weight, which could guide periprocedural management decisions in the future.

- The primary outcome was halftime, the time required for 50% of solid gastric contents to empty, measured using scintigraphy. This analysis included data from five studies involving 247 patients who received either a GLP-1 RA or placebo.

- The secondary outcome was gastric emptying of liquids measured using the acetaminophen absorption test. Ten studies including 411 patients who received either a GLP-1 RA or placebo were included in this analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The mean gastric emptying halftime for solid foods was 138.4 minutes with a GLP-1 RA and 95.0 minutes with placebo, resulting in a pooled mean difference of 36.0 minutes (P < .01).

- Furthermore, the amount of gastric emptying noted at 4 or 5 hours on the acetaminophen absorption test was comparable between these groups.

- The gastric emptying time for both solids and liquids did not differ between GLP-1 RA formulations or between short-acting or long-acting GLP-1 RAs.

IN PRACTICE:

“Based on current evidence, a conservative approach with a liquid diet on the day before procedures while continuing GLP-1 RA therapy would represent the most sensible approach until more conclusive data on a solid diet are available,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Brent Hiramoto, MD, MPH, of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small number of studies utilizing some diagnostic modalities, such as breath testing, precluded a formal meta-analysis of these subgroups. The results could not be stratified by indication for GLP-1 RA (diabetes or obesity) because of insufficient studies in each category.

DISCLOSURES:

The lead author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author declared serving on the advisory boards of three pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients taking a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) experience only a modest delay in gastric emptying of solid foods and no significant delay for liquids, compared with those receiving placebo, indicating that patients may not need to discontinue these medications before surgery.

METHODOLOGY:

- GLP-1 RAs, while effective in managing diabetes and obesity, are linked to delayed gastric emptying, which may pose risks during procedures requiring anesthesia or sedation due to potential aspiration of gastric contents.

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the duration of delay in gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 RAs in patients with diabetes and/or excessive body weight, which could guide periprocedural management decisions in the future.

- The primary outcome was halftime, the time required for 50% of solid gastric contents to empty, measured using scintigraphy. This analysis included data from five studies involving 247 patients who received either a GLP-1 RA or placebo.

- The secondary outcome was gastric emptying of liquids measured using the acetaminophen absorption test. Ten studies including 411 patients who received either a GLP-1 RA or placebo were included in this analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The mean gastric emptying halftime for solid foods was 138.4 minutes with a GLP-1 RA and 95.0 minutes with placebo, resulting in a pooled mean difference of 36.0 minutes (P < .01).

- Furthermore, the amount of gastric emptying noted at 4 or 5 hours on the acetaminophen absorption test was comparable between these groups.

- The gastric emptying time for both solids and liquids did not differ between GLP-1 RA formulations or between short-acting or long-acting GLP-1 RAs.

IN PRACTICE:

“Based on current evidence, a conservative approach with a liquid diet on the day before procedures while continuing GLP-1 RA therapy would represent the most sensible approach until more conclusive data on a solid diet are available,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Brent Hiramoto, MD, MPH, of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small number of studies utilizing some diagnostic modalities, such as breath testing, precluded a formal meta-analysis of these subgroups. The results could not be stratified by indication for GLP-1 RA (diabetes or obesity) because of insufficient studies in each category.

DISCLOSURES:

The lead author was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author declared serving on the advisory boards of three pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-Term Assessment of Weight Loss Medications in a Veteran Population

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 as overweight and those with a BMI > 30 as obese (obesity classes: I, BMI 30 to 34.9; II, BMI 35 to 39.9; and III, BMI ≥ 40).1 In 2011, the CDC estimated that 27.4% of adults in the United States were obese; less than a decade later, that number increased to 31.9%.1 In that same period, the percentage of adults in Indiana classified as obese increased from 30.8% to 36.8%.1 About 1 in 14 individuals in the US have class III obesity and 86% of veterans are either overweight or obese.2

High medical expenses can likely be attributed to the long-term health consequences of obesity. Compared to those with a healthy weight, individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, mental health disorders, body pain, low quality of life, and death.3 Many of these conditions lead to increased health care needs, medication needs, hospitalizations, and overall health care system use.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of obesity have been produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society; the Endocrine Society; the American Diabetes Association; and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense. Each follows a general algorithm to manage and prevent adverse effects (AEs) related to obesity. General practice is to assess a patient for elevated BMI (> 25), implement intense lifestyle modifications including calorie restriction and exercise, reassess for a maintained 5% to 10% weight loss for cardiovascular benefits, and potentially assess for pharmacological or surgical intervention to assist in weight loss.2,4-6

While some weight loss medications (eg, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and lorcaserin) tend to have unfavorable AEs or mixed efficacy, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have provided new options.7-10 Lorcaserin, for example, was removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer risks.11 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for weight loss in 2014 and 2021, respectively.12,13 GLP-1RAs have shown the greatest efficacy and benefits in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); they are the preferred agents for patients who qualify for pharmacologic intervention for weight loss, especially those with T2DM. However, these studies have not evaluated the long-term outcomes of using these medications for weight loss and may not reflect the veteran population.14,15

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), clinicians may use several weight loss medications for patients to achieve 5% to 10% weight loss. The medications most often used include liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone. However, more research is needed to determine which weight loss medication is the most beneficial for veterans, particularly following FDA approval of GLP-1RAs. At VHI, phentermine/topiramate is the preferred first-line agent unless patients have contraindications for use, in which case naltrexone/bupropion is recommended. These are considered first-line due to their ease of use in pill form, lower cost, and comparable weight loss to the GLP-1 medication class.2 However, for patients with prediabetes, T2DM, BMI > 40, or BMI > 35 with specific comorbid conditions, liraglutide is preferred because of its beneficial effects for both weight loss and blood glucose control.2

This study aimed to expand on the 2021 Hood and colleagues study that examined total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage of baseline weight in patients with obesity at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months of pharmacologic therapy by extending the time frame to 48 months.16 This study excluded semaglutide because few patients were prescribed the medication for weight loss during the study.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed weight loss medications at VHI. A patient list was generated based on prescription fills from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021. Data were obtained from the Computerized Patient Record System; patients were not contacted. This study was approved by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and VHI Research and Development Committee.

At the time of this study, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone were available at VHI for patients who met the clinical criteria for use. All patients must have been enrolled in dietary and lifestyle management programs, including the VA MOVE! program, to be approved for these medications. After the MOVE! orientation, patients could participate in group or individual 12-week programs that included weigh-ins, goal-setting strategies, meal planning, and habit modification support. If patients could not meet in person, phone and other telehealth opportunities were available.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years, received a prescription for any of the 5 available medications for weight loss during the enrollment period, and were on the medication for ≥ 6 consecutive months. Patients were excluded if they received a prescription, were treated outside the VA system, or were pregnant. The primary indication for the included medication was not weight loss; the primary indication for the GLP-1RA was T2DM, or the weight loss was attributed to another disease. Adherence was not a measured outcome of this study; if patients were filling the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. Data were collected for each instance of medication use; as a result, a few patients were included more than once. Data collection for a failed medication ended when failure was documented. New data points began when new medication was prescribed; all data were per medication, not per patient. This allowed us to account for medication failure and provide accurate weight loss results based on medication choice within VHI.

Primary outcomes included total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage ofbaseline weight during the study period at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of therapy. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of patients who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight from baseline; the percentage of patients who maintained ≥ 5% weight loss from baseline to 12, 24, 36, and 48 months if maintained on medication for that duration; duration of medication treatment in weeks; medication discontinuation rate; reason for medication discontinuation; enrollment in the MOVE! clinic and the time enrolled; percentage of patients with a BMI of 18 to 24.9 at the end of the study; and change in HbA1c at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months.

Demographic data included race, age, sex, baseline weight, height, baseline BMI, and comorbid conditions (collected based on the most recent primary care clinical note before initiating medication). Medication data collected included medications used to manage comorbidities. Data related to weight management medication included prescribing clinic, maintenance dose of medication, duration of medication during the study period, the reason for medication discontinuation, or bariatric surgery intervention if applicable.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize study participants. For continuous data, analysis of variance tests were used; if those results were not normal, then nonparametric tests were used, followed by pairwise tests between medication groups if the overall test was significant using the Fisher significant differences test. For nominal data, χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used. For comparisons of primary and secondary outcomes, if the analyses needed to include adjustment for confounding variables, analysis of covariance was used for continuous data. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all tests.

RESULTS

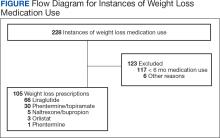

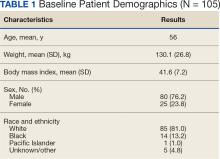

A total of 228 instances of medication use were identified based on prescription fills; 123 did not meet inclusion criteria (117 for < 6 consecutive months of medication use) (Figure). The study included 105 participants with a mean age of 56 years; 80 were male (76.2%), and 85 identified as White race (81.0%). Mean (SD) weight was 130.1 kg (26.8) and BMI was 41.6 (7.2). The most common comorbid disease states among patients included hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and T2DM (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were comparable to those of Hood and colleagues.16

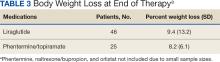

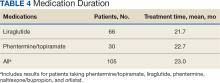

Most patients at VHI started on liraglutide (63%) or phentermine/topiramate (28%). For primary and secondary outcomes, statistics were calculated to determine whether the results were statistically significant for comparing the liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate subgroups. Sample sizes were too small for statistical analysis for bupropion/naltrexone, phentermine, and orlistat.

Primary Outcomes

The mean (SD) weight of participants dropped 8.1% from 130.1 kg to 119.5 kg over the patient-specific duration of weight management medication therapy for an absolute difference of 10.6 kg (9.7). Duration of individual medication use varied from 6 to 48 months. Weight loss was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. Patient weight was not recorded after the medication was discontinued.