User login

Pregnancy after ventral hernia repair increased the risk for recurrence

concluded the authors of a systematic review of the literature on hernia and pregnancy.

Erling Omoa, MD, of Bispebjerg Hospital and the University of Copenhagen, and his colleagues surveyed 5,189 articles and chose four cohort studies, four case-control studies, and one case-series study that met their criteria of quality, comparability, and outcomes data. Only randomized, controlled trials, analytical observational studies, and large case series were included. The focus was primary ventral (umbilical and epigastric) and incisional hernia surgery before, during, and after pregnancy.

“The prevalence of clinically relevant primary ventral hernias is very low during pregnancy,” the investigators wrote, but there is a lack on consensus concerning the management of hernia repair in women of childbearing age. “The objective of this systematic review was to examine the risk of recurrence following prepregnancy ventral hernia repair, and secondly, to evaluate the prevalence of ventral hernia during pregnancy and the risk of surgical repair before and after childbirth,” they wrote.

The reviewers evaluated pregnancy following ventral hernia repair as a potential risk factor for hernia recurrence. One study found that subsequent pregnancy was associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of recurrence. Another found that pregnancy was independently associated with a 73% raised risk of recurrence. The risk of recurrence was no different between mesh and suture repair.

The review found the prevalence of primary ventral and inguinal repair during pregnancy to be low. A single-center cohort study of 20,714 pregnant women of which 17 (0.08%) had umbilical hernias and none of these required repair before delivery. A case series of 126 women who underwent this surgery during pregnancy indicated that this procedure was associated with minimal 30-day morbidity and no deaths. No data was available on fetal morbidity or recurrence in this case series.

Case-control studies reporting on umbilical repair concomitant with elective C-section found that, although adding hernia repair to the procedure increased operative time in some studies, there was no additional complication risk.

Overall, the investigators found several areas in which evidence remains weak, such as the long-term risks for recurrence following pregnancy and long-term outcomes of mesh versus suture repairs. They recommended that patients be counseled on the risk of recurrence linked to subsequent pregnancies and that, if possible, ventral hernia repair should be postponed until after a last planned pregnancy. Watchful waiting until after a delivery was deemed safe in many cases.

The investigators reported no conflicts.

SOURCE: Oma E et al. Am J Surg. 2019 Jan;217:163-8.

concluded the authors of a systematic review of the literature on hernia and pregnancy.

Erling Omoa, MD, of Bispebjerg Hospital and the University of Copenhagen, and his colleagues surveyed 5,189 articles and chose four cohort studies, four case-control studies, and one case-series study that met their criteria of quality, comparability, and outcomes data. Only randomized, controlled trials, analytical observational studies, and large case series were included. The focus was primary ventral (umbilical and epigastric) and incisional hernia surgery before, during, and after pregnancy.

“The prevalence of clinically relevant primary ventral hernias is very low during pregnancy,” the investigators wrote, but there is a lack on consensus concerning the management of hernia repair in women of childbearing age. “The objective of this systematic review was to examine the risk of recurrence following prepregnancy ventral hernia repair, and secondly, to evaluate the prevalence of ventral hernia during pregnancy and the risk of surgical repair before and after childbirth,” they wrote.

The reviewers evaluated pregnancy following ventral hernia repair as a potential risk factor for hernia recurrence. One study found that subsequent pregnancy was associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of recurrence. Another found that pregnancy was independently associated with a 73% raised risk of recurrence. The risk of recurrence was no different between mesh and suture repair.

The review found the prevalence of primary ventral and inguinal repair during pregnancy to be low. A single-center cohort study of 20,714 pregnant women of which 17 (0.08%) had umbilical hernias and none of these required repair before delivery. A case series of 126 women who underwent this surgery during pregnancy indicated that this procedure was associated with minimal 30-day morbidity and no deaths. No data was available on fetal morbidity or recurrence in this case series.

Case-control studies reporting on umbilical repair concomitant with elective C-section found that, although adding hernia repair to the procedure increased operative time in some studies, there was no additional complication risk.

Overall, the investigators found several areas in which evidence remains weak, such as the long-term risks for recurrence following pregnancy and long-term outcomes of mesh versus suture repairs. They recommended that patients be counseled on the risk of recurrence linked to subsequent pregnancies and that, if possible, ventral hernia repair should be postponed until after a last planned pregnancy. Watchful waiting until after a delivery was deemed safe in many cases.

The investigators reported no conflicts.

SOURCE: Oma E et al. Am J Surg. 2019 Jan;217:163-8.

concluded the authors of a systematic review of the literature on hernia and pregnancy.

Erling Omoa, MD, of Bispebjerg Hospital and the University of Copenhagen, and his colleagues surveyed 5,189 articles and chose four cohort studies, four case-control studies, and one case-series study that met their criteria of quality, comparability, and outcomes data. Only randomized, controlled trials, analytical observational studies, and large case series were included. The focus was primary ventral (umbilical and epigastric) and incisional hernia surgery before, during, and after pregnancy.

“The prevalence of clinically relevant primary ventral hernias is very low during pregnancy,” the investigators wrote, but there is a lack on consensus concerning the management of hernia repair in women of childbearing age. “The objective of this systematic review was to examine the risk of recurrence following prepregnancy ventral hernia repair, and secondly, to evaluate the prevalence of ventral hernia during pregnancy and the risk of surgical repair before and after childbirth,” they wrote.

The reviewers evaluated pregnancy following ventral hernia repair as a potential risk factor for hernia recurrence. One study found that subsequent pregnancy was associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of recurrence. Another found that pregnancy was independently associated with a 73% raised risk of recurrence. The risk of recurrence was no different between mesh and suture repair.

The review found the prevalence of primary ventral and inguinal repair during pregnancy to be low. A single-center cohort study of 20,714 pregnant women of which 17 (0.08%) had umbilical hernias and none of these required repair before delivery. A case series of 126 women who underwent this surgery during pregnancy indicated that this procedure was associated with minimal 30-day morbidity and no deaths. No data was available on fetal morbidity or recurrence in this case series.

Case-control studies reporting on umbilical repair concomitant with elective C-section found that, although adding hernia repair to the procedure increased operative time in some studies, there was no additional complication risk.

Overall, the investigators found several areas in which evidence remains weak, such as the long-term risks for recurrence following pregnancy and long-term outcomes of mesh versus suture repairs. They recommended that patients be counseled on the risk of recurrence linked to subsequent pregnancies and that, if possible, ventral hernia repair should be postponed until after a last planned pregnancy. Watchful waiting until after a delivery was deemed safe in many cases.

The investigators reported no conflicts.

SOURCE: Oma E et al. Am J Surg. 2019 Jan;217:163-8.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Is oral or IV iron therapy more beneficial for postpartum anemia?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Sultan P, Bampoe S, Shah R, et al. Oral versus intravenous iron therapy for postpartum anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online December 19, 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.016.

Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy is associated with increased risk for adverse birth outcomes, including preterm delivery, cesarean delivery, and need for blood transfusion.1,2 Although the outcomes with postpartum iron deficiency anemia are more difficult to study, this condition is associated with increased risk of maternal fatigue and depression, and it is often overlooked as a significant issue during the postpartum period.

In a recent systematic review, Sultan and colleagues sought to provide an updated assessment of IV versus oral iron treatment for postpartum anemia. The 6-week postpartum hemoglobin concentration was the primary outcome.

Details of the study

The authors screened 2,744 articles for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing oral and IV iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia. Fifteen RCTs were included in the review, with 1,001 women receiving oral iron therapy and 1,181 women receiving IV iron. The baseline postpartum hemoglobin concentration in the 15 studies ranged from less than 8 g/dL to 10.5 g/dL.

In all but 1 study, the women in the IV treatment arm experienced a significant increase in postpartum hemoglobin concentration, with the mean difference being 1.0 g/dL at postpartum week 1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5–1.5; P<.0001) and 0.9 g/dL at postpartum week 6 (95% CI, 0.4–1.3; P = .0003).

Only 4 studies were included in the meta-analysis; specifically, 6-week postpartum hemoglobin levels were measured in 251 women who received IV iron and in 134 who received oral iron. Significant differences were seen in the IV iron group compared with the oral iron group for 3 of the secondary outcomes evaluated: flushing (odds ratio [OR], 6.95), decreased constipation (OR, 0.08), and decreased dyspepsia (OR, 0.07).

None of the other secondary outcomes associated with IV iron (muscle cramps, headache, urticaria, rash, or anaphylaxis) occurred at statistically significant rates. Notably, adherence was not assessed in the majority of the studies. Although constipation was increased in the oral iron therapy group, it was reported at only 12%.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Results of this study support previous findings that IV iron is better tolerated, with fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects, than oral iron, and they re-emphasize that IV iron therapy is both safe (the authors identified only 2 cases of anaphylaxis) and effective in improving hematologic indices.

Continue to: The systematic review included...

The systematic review included studies, however, that excluded women treated for antepartum anemia, a group that may benefit from aggressive correction of iron deficiency. Another study weakness is that all the oral iron regimens used were dosed either daily or multiple times per day, which may lead to difficulty with adherence and can decrease overall iron absorption compared with an every-other-day regimen.3

Future studies are needed to determine 1) which women with what level of anemia will benefit the most from postpartum IV iron and 2) the hemoglobin level at which IV iron is a cost-effective therapy.

Given the efficacy and reduced adverse effects associated with IV iron therapy demonstrated in the systematic review by Sultan and colleagues, I recommend treatment with IV iron for women with moderate to severe postpartum anemia (defined in pregnancy as a hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL and ferritin less than 40 µg/L) who have not received blood products or for women who are unable to tolerate or absorb oral iron (such as those with a history of bariatric surgery, gastritis, or inflammatory bowel disease). In our institution, we frequently give IV iron sucrose 300 mg prior to discharge due to ease of administration. For women with mild iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin greater than 10 g/dL), I prescribe every-other-day oral iron in the form of ferrous sulfate 325 mg, which effectively raises the hemoglobin level and limits the gastrointestinal side effects associated with more frequent dosing.

Julianna Schantz-Dunn, MD, MPH

- Drukker L, Hants Y, Farkash R, et al. Iron deficiency anemia at admission for labor and delivery is associated with an increased risk for Cesarean section and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Transfusion. 2015;55:2799-2806.

- Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, et al. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:495-504.

- Stoffel NU, Cercamondi CI, Brittenham G, et al. Iron absorption from oral iron supplements given on consecutive versus alternate days and as single morning doses versus twice-daily split dosing in iron-depleted women: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e524-e533.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Sultan P, Bampoe S, Shah R, et al. Oral versus intravenous iron therapy for postpartum anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online December 19, 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.016.

Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy is associated with increased risk for adverse birth outcomes, including preterm delivery, cesarean delivery, and need for blood transfusion.1,2 Although the outcomes with postpartum iron deficiency anemia are more difficult to study, this condition is associated with increased risk of maternal fatigue and depression, and it is often overlooked as a significant issue during the postpartum period.

In a recent systematic review, Sultan and colleagues sought to provide an updated assessment of IV versus oral iron treatment for postpartum anemia. The 6-week postpartum hemoglobin concentration was the primary outcome.

Details of the study

The authors screened 2,744 articles for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing oral and IV iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia. Fifteen RCTs were included in the review, with 1,001 women receiving oral iron therapy and 1,181 women receiving IV iron. The baseline postpartum hemoglobin concentration in the 15 studies ranged from less than 8 g/dL to 10.5 g/dL.

In all but 1 study, the women in the IV treatment arm experienced a significant increase in postpartum hemoglobin concentration, with the mean difference being 1.0 g/dL at postpartum week 1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5–1.5; P<.0001) and 0.9 g/dL at postpartum week 6 (95% CI, 0.4–1.3; P = .0003).

Only 4 studies were included in the meta-analysis; specifically, 6-week postpartum hemoglobin levels were measured in 251 women who received IV iron and in 134 who received oral iron. Significant differences were seen in the IV iron group compared with the oral iron group for 3 of the secondary outcomes evaluated: flushing (odds ratio [OR], 6.95), decreased constipation (OR, 0.08), and decreased dyspepsia (OR, 0.07).

None of the other secondary outcomes associated with IV iron (muscle cramps, headache, urticaria, rash, or anaphylaxis) occurred at statistically significant rates. Notably, adherence was not assessed in the majority of the studies. Although constipation was increased in the oral iron therapy group, it was reported at only 12%.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Results of this study support previous findings that IV iron is better tolerated, with fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects, than oral iron, and they re-emphasize that IV iron therapy is both safe (the authors identified only 2 cases of anaphylaxis) and effective in improving hematologic indices.

Continue to: The systematic review included...

The systematic review included studies, however, that excluded women treated for antepartum anemia, a group that may benefit from aggressive correction of iron deficiency. Another study weakness is that all the oral iron regimens used were dosed either daily or multiple times per day, which may lead to difficulty with adherence and can decrease overall iron absorption compared with an every-other-day regimen.3

Future studies are needed to determine 1) which women with what level of anemia will benefit the most from postpartum IV iron and 2) the hemoglobin level at which IV iron is a cost-effective therapy.

Given the efficacy and reduced adverse effects associated with IV iron therapy demonstrated in the systematic review by Sultan and colleagues, I recommend treatment with IV iron for women with moderate to severe postpartum anemia (defined in pregnancy as a hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL and ferritin less than 40 µg/L) who have not received blood products or for women who are unable to tolerate or absorb oral iron (such as those with a history of bariatric surgery, gastritis, or inflammatory bowel disease). In our institution, we frequently give IV iron sucrose 300 mg prior to discharge due to ease of administration. For women with mild iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin greater than 10 g/dL), I prescribe every-other-day oral iron in the form of ferrous sulfate 325 mg, which effectively raises the hemoglobin level and limits the gastrointestinal side effects associated with more frequent dosing.

Julianna Schantz-Dunn, MD, MPH

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Sultan P, Bampoe S, Shah R, et al. Oral versus intravenous iron therapy for postpartum anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online December 19, 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.016.

Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy is associated with increased risk for adverse birth outcomes, including preterm delivery, cesarean delivery, and need for blood transfusion.1,2 Although the outcomes with postpartum iron deficiency anemia are more difficult to study, this condition is associated with increased risk of maternal fatigue and depression, and it is often overlooked as a significant issue during the postpartum period.

In a recent systematic review, Sultan and colleagues sought to provide an updated assessment of IV versus oral iron treatment for postpartum anemia. The 6-week postpartum hemoglobin concentration was the primary outcome.

Details of the study

The authors screened 2,744 articles for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing oral and IV iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia. Fifteen RCTs were included in the review, with 1,001 women receiving oral iron therapy and 1,181 women receiving IV iron. The baseline postpartum hemoglobin concentration in the 15 studies ranged from less than 8 g/dL to 10.5 g/dL.

In all but 1 study, the women in the IV treatment arm experienced a significant increase in postpartum hemoglobin concentration, with the mean difference being 1.0 g/dL at postpartum week 1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5–1.5; P<.0001) and 0.9 g/dL at postpartum week 6 (95% CI, 0.4–1.3; P = .0003).

Only 4 studies were included in the meta-analysis; specifically, 6-week postpartum hemoglobin levels were measured in 251 women who received IV iron and in 134 who received oral iron. Significant differences were seen in the IV iron group compared with the oral iron group for 3 of the secondary outcomes evaluated: flushing (odds ratio [OR], 6.95), decreased constipation (OR, 0.08), and decreased dyspepsia (OR, 0.07).

None of the other secondary outcomes associated with IV iron (muscle cramps, headache, urticaria, rash, or anaphylaxis) occurred at statistically significant rates. Notably, adherence was not assessed in the majority of the studies. Although constipation was increased in the oral iron therapy group, it was reported at only 12%.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Results of this study support previous findings that IV iron is better tolerated, with fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects, than oral iron, and they re-emphasize that IV iron therapy is both safe (the authors identified only 2 cases of anaphylaxis) and effective in improving hematologic indices.

Continue to: The systematic review included...

The systematic review included studies, however, that excluded women treated for antepartum anemia, a group that may benefit from aggressive correction of iron deficiency. Another study weakness is that all the oral iron regimens used were dosed either daily or multiple times per day, which may lead to difficulty with adherence and can decrease overall iron absorption compared with an every-other-day regimen.3

Future studies are needed to determine 1) which women with what level of anemia will benefit the most from postpartum IV iron and 2) the hemoglobin level at which IV iron is a cost-effective therapy.

Given the efficacy and reduced adverse effects associated with IV iron therapy demonstrated in the systematic review by Sultan and colleagues, I recommend treatment with IV iron for women with moderate to severe postpartum anemia (defined in pregnancy as a hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL and ferritin less than 40 µg/L) who have not received blood products or for women who are unable to tolerate or absorb oral iron (such as those with a history of bariatric surgery, gastritis, or inflammatory bowel disease). In our institution, we frequently give IV iron sucrose 300 mg prior to discharge due to ease of administration. For women with mild iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin greater than 10 g/dL), I prescribe every-other-day oral iron in the form of ferrous sulfate 325 mg, which effectively raises the hemoglobin level and limits the gastrointestinal side effects associated with more frequent dosing.

Julianna Schantz-Dunn, MD, MPH

- Drukker L, Hants Y, Farkash R, et al. Iron deficiency anemia at admission for labor and delivery is associated with an increased risk for Cesarean section and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Transfusion. 2015;55:2799-2806.

- Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, et al. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:495-504.

- Stoffel NU, Cercamondi CI, Brittenham G, et al. Iron absorption from oral iron supplements given on consecutive versus alternate days and as single morning doses versus twice-daily split dosing in iron-depleted women: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e524-e533.

- Drukker L, Hants Y, Farkash R, et al. Iron deficiency anemia at admission for labor and delivery is associated with an increased risk for Cesarean section and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Transfusion. 2015;55:2799-2806.

- Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, et al. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:495-504.

- Stoffel NU, Cercamondi CI, Brittenham G, et al. Iron absorption from oral iron supplements given on consecutive versus alternate days and as single morning doses versus twice-daily split dosing in iron-depleted women: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e524-e533.

What is your approach to the persistent occiput posterior malposition?

CASE 7- to 8-lb baby suspected to be in occiput posterior (OP) position

A certified nurse midwife (CNM) asks you to consult on a 37-year-old woman (G1P0) at 41 weeks’ gestation who was admitted to labor and delivery for a late-term induction. The patient had a normal first stage of labor with placement of a combined spinal-epidural anesthetic at a cervical dilation of 4 cm. She has been fully dilated for 3.5 hours and pushing for 2.5 hours with a Category 1 fetal heart rate tracing. The CNM reports that the estimated fetal weight is 7 to 8 lb and the station is +3/5. She suspects that the fetus is in the left OP position. She asks for your advice on how to best deliver the fetus. The patient strongly prefers not to have a cesarean delivery (CD).

What is your recommended approach?

The cardinal movements of labor include cephalic engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension and rotation of the head at delivery, internal rotation of the shoulders, and expulsion of the body. In the first stage of labor many fetuses are in the OP position. Flexion and internal rotation of the fetal head in a mother with a gynecoid pelvis results in most fetuses assuming an occiput anterior (OA) position with the presenting diameter of the head (occipitobregmatic) being optimal for spontaneous vaginal delivery. Late in the second stage of labor only about 5% of fetuses are in the OP position with the presenting diameter of the head being large (occipitofrontal) with an extended head attitude, thereby reducing the probability of a rapid spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Risk factors for OP position late in the second stage of labor include1,2:

- nulliparity

- body mass index > 29 kg/m2

- gestation age ≥ 41 weeks

- birth weight > 4 kg

- regional anesthesia.

Maternal outcomes associated with persistent OP position include protracted first and second stage of labor, arrest of second stage of labor, and increased rates of operative vaginal delivery, anal sphincter injury, CD, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and endomyometritis.1,3,4 The neonatal complications of persistent OP position include increased rates of shoulder dystocia, low Apgar score, umbilical artery acidemia, meconium, and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit.1,5

Diagnosis

Many obstetricians report that they can reliably detect a fetus in the OP position based upon abdominal palpation of the fetal spine and digital vaginal examination of the fetal sutures, fontanels, and ears. Such self-confidence may not be wholly warranted, however. Most contemporary data indicate that digital vaginal examination has an error rate of approximately 20% for identifying the position of the cephalic fetus, especially in the presence of fetal caput succedaneum and asynclitism.6-10

The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) recommends that cephalic position be determined by transabdominal imaging.11 By placing the ultrasound probe on the maternal abdomen, a view of the fetal body at the level of the chest helps determine the position of the fetal spine. When the probe is placed in a suprapubic position, the observation of the fetal orbits facing the probe indicates an OP position.

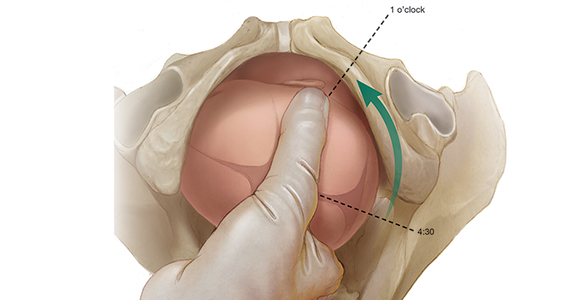

When the presenting part is at a very low station, a transperineal ultrasound may be helpful to determine the position of the occiput. The ISUOG recommends that position be defined using a clock face, with positions from 330 h to 830 h being indicative of OP and positions from 930 h to 230 h being indicative of OA.11 The small remaining slivers on the clock face indicate an occiput transverse position (FIGURE).11

Continue to: Approaches to managing the OP position

Approaches to managing the OP position

First stage of labor

Identification of a cephalic-presenting fetus in the OP position in the first stage of labor might warrant increased attention to fetal position in the second stage of labor, but does not usually alter management of the first stage.

Second stage of labor

If an OP position is identified in the second stage of labor, many obstetricians will consider manual rotation of the fetal occiput to an anterior pelvic quadrant to facilitate labor progress. Because a fetus in the OP position may spontaneously rotate to the OA position at any point during the second stage, a judicious interval of waiting is reasonable before attempting a manual rotation in the second stage. For example, allowing the second stage to progress for 60 to 90 min in a nulliparous woman or 30 to 60 min in a multiparous woman will permit some fetuses to rotate to the OA position without intervention.

If the OP position persists beyond these time points, a manual rotation could be considered. There are no high-quality clinical trials to support this maneuver,12 but observational reports suggest that this low-risk maneuver may help reduce the rate of CD and anal sphincter trauma.13-15

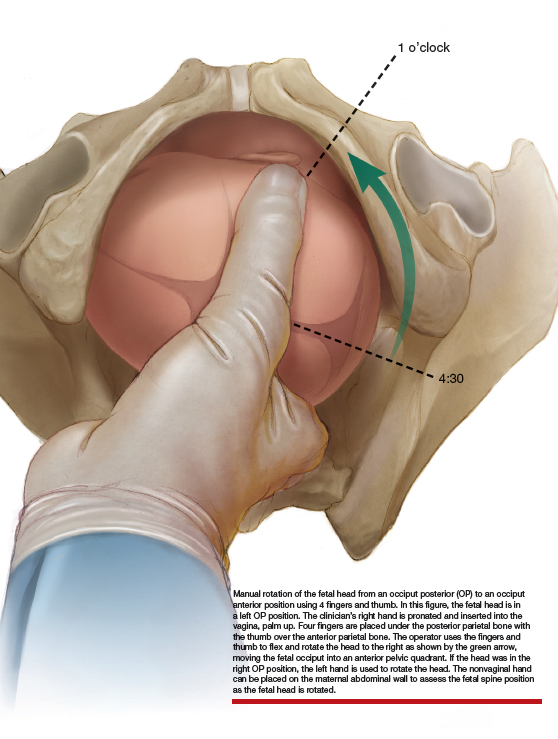

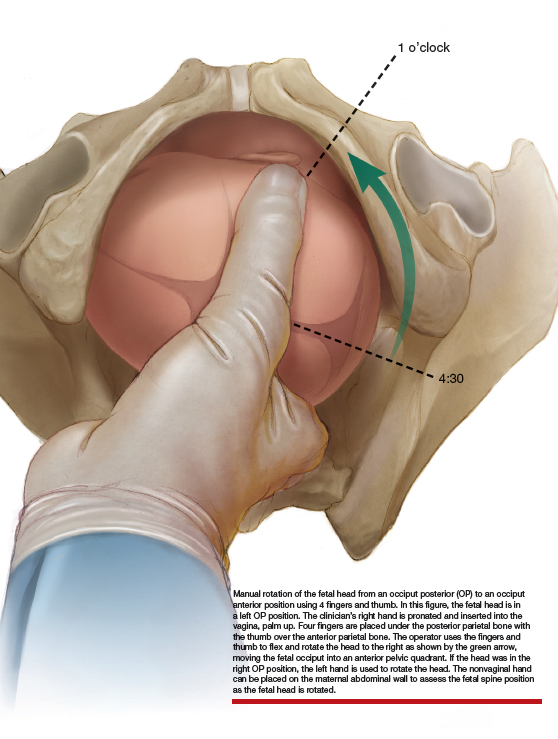

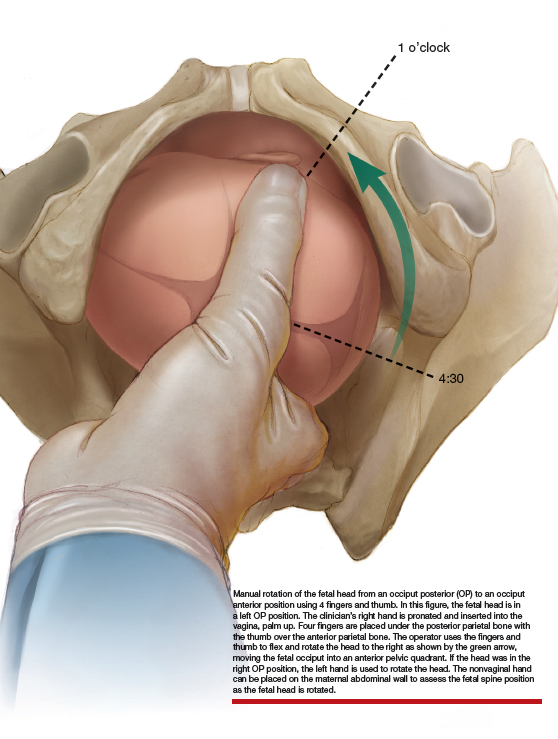

Manual rotation from OP to OA. Prior to performing the rotation, the maternal bladder should be emptied and an adequate anesthetic provided. One technique is to use the 4 fingers of the hand as a “spatula” to turn the head. If the fetus is in a left OP position, the operator’s right hand is pronated and inserted into the vagina, palm up. Four fingers are placed under the posterior parietal bone with the thumb over the anterior parietal bone (ILLUSTRATION).4 The operator uses the fingers and thumb to flex and rotate the head to the right, moving the fetal occiput into an anterior pelvic quadrant.4 If the head is in the right OP position, the left hand is used to rotate the head. The nonvaginal hand can be placed on the maternal abdominal wall to assess the fetal spine position as the fetal head is rotated. The fetal head may need to be held in the anterior pelvic quadrant during a few maternal pushes to prevent the head from rotating back into the OP position.

Approaching delivery late in the second stage

If the second stage has progressed for 3 or 4 hours, as in the case described above, and the fetus remains in the OP position, delivery may be indicated to avoid the maternal and fetal complications of an even more prolonged second stage. At some point in a prolonged second stage, expectant management carries more maternal and fetal risks than intervention.

Late in the second stage, options for delivery of the fetus in the OP include: CD, rotational forceps delivery, direct forceps delivery from the OP position, and vacuum delivery.

Cesarean delivery. CD of the fetus in the OP position may be indicated when the fetus is estimated to be macrosomic, the station is high (biparietal diameter palpable on abdominal examination), or when the parturient has an android pelvis (narrow fore-pelvis and anterior convergence of the pelvic bone structures in a wedge shape). During CD, if difficulty is encountered in delivering the fetal head, a hand from below, extension of the uterine incision, or reverse breech extraction may be necessary to complete the delivery. If the clinical situation is conducive to operative vaginal delivery, forceps or vacuum can be used.

Continue to: Rotational forceps delivery...

Rotational forceps delivery. During residency I was told to always use rotational forceps to deliver a fetus in the persistently OP position if the parturient had a gynecoid pelvis (wide oval shape of pelvic bones, wide subpubic arch). Dr. Frederick Irving wrote16:

“Although textbooks almost universally advocate the extraction of the occiput directly posterior without rotation we do not advise it.... Such an extraction maneuver is inartistic and show[s] a lack of regard for the mechanical factors involved in the mechanism of labor. The method used at the Boston Lying-In Hospital presupposes an accurate diagnosis of the primary position. If the fetal back is on the right the head should be rotated to the right; if on the left, toward the left. The head is always rotated in the direction in which the back lies. The forceps are applied as if the occiput was directly anterior. Carrying the forceps handles in a wide sweep the occiput is now rotated to the anterior quadrant of the pelvis or 135 degrees. It will be found that the head turns easily in the way it should go but that it is difficult or impossible to rotate it in the improper direction. The instrument is then reapplied as in the second part of the Scanzoni maneuver.”

Rotation of the fetus from the OP to the OA position may reduce the risk of sphincter injury with vaginal birth. With the waning of rotational forceps skills, many obstetricians prefer a nonrotational approach with direct forceps or vacuum delivery from the OP position.

Direct forceps delivery from the OP position. A fetus in the OP position for 3 to 4 hours of the second stage of labor will often have a significant degree of head molding. The Simpson forceps, with its shallow and longer cephalic curve, accommodates significant fetal head molding and is a good forceps choice in this situation.

Vacuum delivery. In the United States, approximately 5% of vaginal deliveries are performed with a vacuum device, and 1% with forceps.17 Consequently, many obstetricians frequently perform operative vaginal delivery with a vacuum device and infrequently or never perform operative vaginal delivery with forceps. Vacuum vaginal delivery may be the instrument of choice for many obstetricians performing an operative delivery of a fetus in the OP position. However, the vacuum has a higher rate of failure, especially if the OP fetus is at a higher station.18

In some centers, direct forceps delivery from the OP position is preferred over an attempt at vacuum delivery, because in contemporary obstetric practice most centers do not permit the sequential use of vacuum followed by forceps (due to the higher rate of fetal trauma of combination operative delivery). Since vacuum delivery of the fetus in the OP position has a greater rate of failure than forceps, it may be best to initiate operative vaginal delivery of the fetus in the OP position with forceps. If vacuum is used to attempt a vaginal delivery and fails due to too many pop-offs, a CD would be the next step.

Take action when needed to optimize outcomes

The persistent OP position is associated with a longer second stage of labor. It is common during a change of shift for an obstetrician to sign out to the on-coming clinician a case of a prolonged second stage with the fetus in the OP position. In this situation, the on-coming clinician cannot wait hour after hour after hour hoping for a spontaneous delivery. If the on-coming clinician has a clear plan of how to deal with the persistent OP position—including ultrasound confirmation of position and physical examination to determine station, fetal size and adequacy of the pelvis, and timely selection of a delivery technique—the adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes sometimes caused by the persistent OP position will be minimized.

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

The consulting obstetrician performed a transabdominal ultrasound and observed the fetal orbits were facing the transducer, confirming an OP position. On physical examination, the station was +3/5, and the fetal weight was confirmed to be approximately 8 lb. The obstetrician recommended a direct forceps delivery from the OP position. The patient and CNM agreed with the plan.

The obstetrician applied Simpson forceps and performed a mediolateral episiotomy just prior to delivery of the head. Following delivery, the rectal sphincter and anal mucosa were intact and the episiotomy was repaired. The newborn, safely delivered, and the mother, having avoided a CD, were transferred to the postpartum floor later in the day.

- Cheng YW, Hubbard A, Caughey AB, et al. The association between persistent fetal occiput posterior position and perinatal outcomes: An example of propensity score and covariate distance matching. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:656-663.

- Cheng YW, Shaffer BL, Caughey AB. Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: a retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:563-568.

- Ponkey SE, Cohen AP, Heffner LJ, et al. Persistent fetal occiput posterior position: obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:915-920.

- Barth WH Jr. Persistent occiput posterior. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:695-709.

- Cheng YW, Shaffer BL, Caughey AB. The association between persistent occiput posterior position and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:837-844.

- Ghi T, Dall’Asta A, Masturzo B, et al. Randomised Italian sonography for occiput position trial ante vacuum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:699-705.

- Bellussi F, Ghi T, Youssef A, et al. The use of intrapartum ultrasound to diagnose malpositions and cephalic malpresentations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:633-641.

- Ramphul M, Ooi PV, Burke G, et al. Instrumental delivery and ultrasound: a multicenter randomised controlled trial of ultrasound assessment of the fetal head position versus standard of care as an approach to prevent morbidity at instrumental delivery. BJOG. 2014;121:1029-1038.

- Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Barbera A, et al. Occiput posterior position diagnosis: vaginal examination or intrapartum sonography? A clinical review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:520-526.

- Akmal S, Tsoi E, Kaemtas N, et al. Intrapartum sonography to determine fetal head position. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;12:172-177.

- Ghi T, Eggebo T, Lees C, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: intrapartum ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:128-139.

- Phipps H, de Vries B, Hyett J, et al. Prophylactic manual rotation for fetal malposition to reduce operative delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD009298.

- Le Ray C, Serres P, Schmitz T, et al. Manual rotation in occiput posterior or transverse positions. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:873-879.

- Shaffer BL, Cheng YW, Vargas JE, et al. Manual rotation to reduce caesarean delivery in persistent occiput posterior or transverse position. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:65-72.

- Bertholdt C, Gauchotte E, Dap M, et al. Predictors of successful manual rotation for occiput posterior positions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;144:210–215.

- Irving FC. A Textbook of Obstetrics. New York, NY: Macmillan, NY; 1936:426-428.

- Merriam AA, Ananth CV, Wright JD, et al. Trends in operative vaginal delivery, 2005–2013: a population-based study. BJOG. 2017;124:1365-1372.

- Verhoeven CJ, Nuij C, Janssen-Rolf CR, et al. Predictors of failure of vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:29-34.

CASE 7- to 8-lb baby suspected to be in occiput posterior (OP) position

A certified nurse midwife (CNM) asks you to consult on a 37-year-old woman (G1P0) at 41 weeks’ gestation who was admitted to labor and delivery for a late-term induction. The patient had a normal first stage of labor with placement of a combined spinal-epidural anesthetic at a cervical dilation of 4 cm. She has been fully dilated for 3.5 hours and pushing for 2.5 hours with a Category 1 fetal heart rate tracing. The CNM reports that the estimated fetal weight is 7 to 8 lb and the station is +3/5. She suspects that the fetus is in the left OP position. She asks for your advice on how to best deliver the fetus. The patient strongly prefers not to have a cesarean delivery (CD).

What is your recommended approach?

The cardinal movements of labor include cephalic engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension and rotation of the head at delivery, internal rotation of the shoulders, and expulsion of the body. In the first stage of labor many fetuses are in the OP position. Flexion and internal rotation of the fetal head in a mother with a gynecoid pelvis results in most fetuses assuming an occiput anterior (OA) position with the presenting diameter of the head (occipitobregmatic) being optimal for spontaneous vaginal delivery. Late in the second stage of labor only about 5% of fetuses are in the OP position with the presenting diameter of the head being large (occipitofrontal) with an extended head attitude, thereby reducing the probability of a rapid spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Risk factors for OP position late in the second stage of labor include1,2:

- nulliparity

- body mass index > 29 kg/m2

- gestation age ≥ 41 weeks

- birth weight > 4 kg

- regional anesthesia.

Maternal outcomes associated with persistent OP position include protracted first and second stage of labor, arrest of second stage of labor, and increased rates of operative vaginal delivery, anal sphincter injury, CD, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and endomyometritis.1,3,4 The neonatal complications of persistent OP position include increased rates of shoulder dystocia, low Apgar score, umbilical artery acidemia, meconium, and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit.1,5

Diagnosis

Many obstetricians report that they can reliably detect a fetus in the OP position based upon abdominal palpation of the fetal spine and digital vaginal examination of the fetal sutures, fontanels, and ears. Such self-confidence may not be wholly warranted, however. Most contemporary data indicate that digital vaginal examination has an error rate of approximately 20% for identifying the position of the cephalic fetus, especially in the presence of fetal caput succedaneum and asynclitism.6-10

The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) recommends that cephalic position be determined by transabdominal imaging.11 By placing the ultrasound probe on the maternal abdomen, a view of the fetal body at the level of the chest helps determine the position of the fetal spine. When the probe is placed in a suprapubic position, the observation of the fetal orbits facing the probe indicates an OP position.

When the presenting part is at a very low station, a transperineal ultrasound may be helpful to determine the position of the occiput. The ISUOG recommends that position be defined using a clock face, with positions from 330 h to 830 h being indicative of OP and positions from 930 h to 230 h being indicative of OA.11 The small remaining slivers on the clock face indicate an occiput transverse position (FIGURE).11

Continue to: Approaches to managing the OP position

Approaches to managing the OP position

First stage of labor

Identification of a cephalic-presenting fetus in the OP position in the first stage of labor might warrant increased attention to fetal position in the second stage of labor, but does not usually alter management of the first stage.

Second stage of labor

If an OP position is identified in the second stage of labor, many obstetricians will consider manual rotation of the fetal occiput to an anterior pelvic quadrant to facilitate labor progress. Because a fetus in the OP position may spontaneously rotate to the OA position at any point during the second stage, a judicious interval of waiting is reasonable before attempting a manual rotation in the second stage. For example, allowing the second stage to progress for 60 to 90 min in a nulliparous woman or 30 to 60 min in a multiparous woman will permit some fetuses to rotate to the OA position without intervention.

If the OP position persists beyond these time points, a manual rotation could be considered. There are no high-quality clinical trials to support this maneuver,12 but observational reports suggest that this low-risk maneuver may help reduce the rate of CD and anal sphincter trauma.13-15

Manual rotation from OP to OA. Prior to performing the rotation, the maternal bladder should be emptied and an adequate anesthetic provided. One technique is to use the 4 fingers of the hand as a “spatula” to turn the head. If the fetus is in a left OP position, the operator’s right hand is pronated and inserted into the vagina, palm up. Four fingers are placed under the posterior parietal bone with the thumb over the anterior parietal bone (ILLUSTRATION).4 The operator uses the fingers and thumb to flex and rotate the head to the right, moving the fetal occiput into an anterior pelvic quadrant.4 If the head is in the right OP position, the left hand is used to rotate the head. The nonvaginal hand can be placed on the maternal abdominal wall to assess the fetal spine position as the fetal head is rotated. The fetal head may need to be held in the anterior pelvic quadrant during a few maternal pushes to prevent the head from rotating back into the OP position.

Approaching delivery late in the second stage

If the second stage has progressed for 3 or 4 hours, as in the case described above, and the fetus remains in the OP position, delivery may be indicated to avoid the maternal and fetal complications of an even more prolonged second stage. At some point in a prolonged second stage, expectant management carries more maternal and fetal risks than intervention.

Late in the second stage, options for delivery of the fetus in the OP include: CD, rotational forceps delivery, direct forceps delivery from the OP position, and vacuum delivery.

Cesarean delivery. CD of the fetus in the OP position may be indicated when the fetus is estimated to be macrosomic, the station is high (biparietal diameter palpable on abdominal examination), or when the parturient has an android pelvis (narrow fore-pelvis and anterior convergence of the pelvic bone structures in a wedge shape). During CD, if difficulty is encountered in delivering the fetal head, a hand from below, extension of the uterine incision, or reverse breech extraction may be necessary to complete the delivery. If the clinical situation is conducive to operative vaginal delivery, forceps or vacuum can be used.

Continue to: Rotational forceps delivery...

Rotational forceps delivery. During residency I was told to always use rotational forceps to deliver a fetus in the persistently OP position if the parturient had a gynecoid pelvis (wide oval shape of pelvic bones, wide subpubic arch). Dr. Frederick Irving wrote16:

“Although textbooks almost universally advocate the extraction of the occiput directly posterior without rotation we do not advise it.... Such an extraction maneuver is inartistic and show[s] a lack of regard for the mechanical factors involved in the mechanism of labor. The method used at the Boston Lying-In Hospital presupposes an accurate diagnosis of the primary position. If the fetal back is on the right the head should be rotated to the right; if on the left, toward the left. The head is always rotated in the direction in which the back lies. The forceps are applied as if the occiput was directly anterior. Carrying the forceps handles in a wide sweep the occiput is now rotated to the anterior quadrant of the pelvis or 135 degrees. It will be found that the head turns easily in the way it should go but that it is difficult or impossible to rotate it in the improper direction. The instrument is then reapplied as in the second part of the Scanzoni maneuver.”

Rotation of the fetus from the OP to the OA position may reduce the risk of sphincter injury with vaginal birth. With the waning of rotational forceps skills, many obstetricians prefer a nonrotational approach with direct forceps or vacuum delivery from the OP position.

Direct forceps delivery from the OP position. A fetus in the OP position for 3 to 4 hours of the second stage of labor will often have a significant degree of head molding. The Simpson forceps, with its shallow and longer cephalic curve, accommodates significant fetal head molding and is a good forceps choice in this situation.

Vacuum delivery. In the United States, approximately 5% of vaginal deliveries are performed with a vacuum device, and 1% with forceps.17 Consequently, many obstetricians frequently perform operative vaginal delivery with a vacuum device and infrequently or never perform operative vaginal delivery with forceps. Vacuum vaginal delivery may be the instrument of choice for many obstetricians performing an operative delivery of a fetus in the OP position. However, the vacuum has a higher rate of failure, especially if the OP fetus is at a higher station.18

In some centers, direct forceps delivery from the OP position is preferred over an attempt at vacuum delivery, because in contemporary obstetric practice most centers do not permit the sequential use of vacuum followed by forceps (due to the higher rate of fetal trauma of combination operative delivery). Since vacuum delivery of the fetus in the OP position has a greater rate of failure than forceps, it may be best to initiate operative vaginal delivery of the fetus in the OP position with forceps. If vacuum is used to attempt a vaginal delivery and fails due to too many pop-offs, a CD would be the next step.

Take action when needed to optimize outcomes

The persistent OP position is associated with a longer second stage of labor. It is common during a change of shift for an obstetrician to sign out to the on-coming clinician a case of a prolonged second stage with the fetus in the OP position. In this situation, the on-coming clinician cannot wait hour after hour after hour hoping for a spontaneous delivery. If the on-coming clinician has a clear plan of how to deal with the persistent OP position—including ultrasound confirmation of position and physical examination to determine station, fetal size and adequacy of the pelvis, and timely selection of a delivery technique—the adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes sometimes caused by the persistent OP position will be minimized.

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

The consulting obstetrician performed a transabdominal ultrasound and observed the fetal orbits were facing the transducer, confirming an OP position. On physical examination, the station was +3/5, and the fetal weight was confirmed to be approximately 8 lb. The obstetrician recommended a direct forceps delivery from the OP position. The patient and CNM agreed with the plan.

The obstetrician applied Simpson forceps and performed a mediolateral episiotomy just prior to delivery of the head. Following delivery, the rectal sphincter and anal mucosa were intact and the episiotomy was repaired. The newborn, safely delivered, and the mother, having avoided a CD, were transferred to the postpartum floor later in the day.

CASE 7- to 8-lb baby suspected to be in occiput posterior (OP) position

A certified nurse midwife (CNM) asks you to consult on a 37-year-old woman (G1P0) at 41 weeks’ gestation who was admitted to labor and delivery for a late-term induction. The patient had a normal first stage of labor with placement of a combined spinal-epidural anesthetic at a cervical dilation of 4 cm. She has been fully dilated for 3.5 hours and pushing for 2.5 hours with a Category 1 fetal heart rate tracing. The CNM reports that the estimated fetal weight is 7 to 8 lb and the station is +3/5. She suspects that the fetus is in the left OP position. She asks for your advice on how to best deliver the fetus. The patient strongly prefers not to have a cesarean delivery (CD).

What is your recommended approach?

The cardinal movements of labor include cephalic engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension and rotation of the head at delivery, internal rotation of the shoulders, and expulsion of the body. In the first stage of labor many fetuses are in the OP position. Flexion and internal rotation of the fetal head in a mother with a gynecoid pelvis results in most fetuses assuming an occiput anterior (OA) position with the presenting diameter of the head (occipitobregmatic) being optimal for spontaneous vaginal delivery. Late in the second stage of labor only about 5% of fetuses are in the OP position with the presenting diameter of the head being large (occipitofrontal) with an extended head attitude, thereby reducing the probability of a rapid spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Risk factors for OP position late in the second stage of labor include1,2:

- nulliparity

- body mass index > 29 kg/m2

- gestation age ≥ 41 weeks

- birth weight > 4 kg

- regional anesthesia.

Maternal outcomes associated with persistent OP position include protracted first and second stage of labor, arrest of second stage of labor, and increased rates of operative vaginal delivery, anal sphincter injury, CD, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and endomyometritis.1,3,4 The neonatal complications of persistent OP position include increased rates of shoulder dystocia, low Apgar score, umbilical artery acidemia, meconium, and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit.1,5

Diagnosis

Many obstetricians report that they can reliably detect a fetus in the OP position based upon abdominal palpation of the fetal spine and digital vaginal examination of the fetal sutures, fontanels, and ears. Such self-confidence may not be wholly warranted, however. Most contemporary data indicate that digital vaginal examination has an error rate of approximately 20% for identifying the position of the cephalic fetus, especially in the presence of fetal caput succedaneum and asynclitism.6-10

The International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) recommends that cephalic position be determined by transabdominal imaging.11 By placing the ultrasound probe on the maternal abdomen, a view of the fetal body at the level of the chest helps determine the position of the fetal spine. When the probe is placed in a suprapubic position, the observation of the fetal orbits facing the probe indicates an OP position.

When the presenting part is at a very low station, a transperineal ultrasound may be helpful to determine the position of the occiput. The ISUOG recommends that position be defined using a clock face, with positions from 330 h to 830 h being indicative of OP and positions from 930 h to 230 h being indicative of OA.11 The small remaining slivers on the clock face indicate an occiput transverse position (FIGURE).11

Continue to: Approaches to managing the OP position

Approaches to managing the OP position

First stage of labor

Identification of a cephalic-presenting fetus in the OP position in the first stage of labor might warrant increased attention to fetal position in the second stage of labor, but does not usually alter management of the first stage.

Second stage of labor

If an OP position is identified in the second stage of labor, many obstetricians will consider manual rotation of the fetal occiput to an anterior pelvic quadrant to facilitate labor progress. Because a fetus in the OP position may spontaneously rotate to the OA position at any point during the second stage, a judicious interval of waiting is reasonable before attempting a manual rotation in the second stage. For example, allowing the second stage to progress for 60 to 90 min in a nulliparous woman or 30 to 60 min in a multiparous woman will permit some fetuses to rotate to the OA position without intervention.

If the OP position persists beyond these time points, a manual rotation could be considered. There are no high-quality clinical trials to support this maneuver,12 but observational reports suggest that this low-risk maneuver may help reduce the rate of CD and anal sphincter trauma.13-15

Manual rotation from OP to OA. Prior to performing the rotation, the maternal bladder should be emptied and an adequate anesthetic provided. One technique is to use the 4 fingers of the hand as a “spatula” to turn the head. If the fetus is in a left OP position, the operator’s right hand is pronated and inserted into the vagina, palm up. Four fingers are placed under the posterior parietal bone with the thumb over the anterior parietal bone (ILLUSTRATION).4 The operator uses the fingers and thumb to flex and rotate the head to the right, moving the fetal occiput into an anterior pelvic quadrant.4 If the head is in the right OP position, the left hand is used to rotate the head. The nonvaginal hand can be placed on the maternal abdominal wall to assess the fetal spine position as the fetal head is rotated. The fetal head may need to be held in the anterior pelvic quadrant during a few maternal pushes to prevent the head from rotating back into the OP position.

Approaching delivery late in the second stage

If the second stage has progressed for 3 or 4 hours, as in the case described above, and the fetus remains in the OP position, delivery may be indicated to avoid the maternal and fetal complications of an even more prolonged second stage. At some point in a prolonged second stage, expectant management carries more maternal and fetal risks than intervention.

Late in the second stage, options for delivery of the fetus in the OP include: CD, rotational forceps delivery, direct forceps delivery from the OP position, and vacuum delivery.

Cesarean delivery. CD of the fetus in the OP position may be indicated when the fetus is estimated to be macrosomic, the station is high (biparietal diameter palpable on abdominal examination), or when the parturient has an android pelvis (narrow fore-pelvis and anterior convergence of the pelvic bone structures in a wedge shape). During CD, if difficulty is encountered in delivering the fetal head, a hand from below, extension of the uterine incision, or reverse breech extraction may be necessary to complete the delivery. If the clinical situation is conducive to operative vaginal delivery, forceps or vacuum can be used.

Continue to: Rotational forceps delivery...

Rotational forceps delivery. During residency I was told to always use rotational forceps to deliver a fetus in the persistently OP position if the parturient had a gynecoid pelvis (wide oval shape of pelvic bones, wide subpubic arch). Dr. Frederick Irving wrote16:

“Although textbooks almost universally advocate the extraction of the occiput directly posterior without rotation we do not advise it.... Such an extraction maneuver is inartistic and show[s] a lack of regard for the mechanical factors involved in the mechanism of labor. The method used at the Boston Lying-In Hospital presupposes an accurate diagnosis of the primary position. If the fetal back is on the right the head should be rotated to the right; if on the left, toward the left. The head is always rotated in the direction in which the back lies. The forceps are applied as if the occiput was directly anterior. Carrying the forceps handles in a wide sweep the occiput is now rotated to the anterior quadrant of the pelvis or 135 degrees. It will be found that the head turns easily in the way it should go but that it is difficult or impossible to rotate it in the improper direction. The instrument is then reapplied as in the second part of the Scanzoni maneuver.”

Rotation of the fetus from the OP to the OA position may reduce the risk of sphincter injury with vaginal birth. With the waning of rotational forceps skills, many obstetricians prefer a nonrotational approach with direct forceps or vacuum delivery from the OP position.

Direct forceps delivery from the OP position. A fetus in the OP position for 3 to 4 hours of the second stage of labor will often have a significant degree of head molding. The Simpson forceps, with its shallow and longer cephalic curve, accommodates significant fetal head molding and is a good forceps choice in this situation.

Vacuum delivery. In the United States, approximately 5% of vaginal deliveries are performed with a vacuum device, and 1% with forceps.17 Consequently, many obstetricians frequently perform operative vaginal delivery with a vacuum device and infrequently or never perform operative vaginal delivery with forceps. Vacuum vaginal delivery may be the instrument of choice for many obstetricians performing an operative delivery of a fetus in the OP position. However, the vacuum has a higher rate of failure, especially if the OP fetus is at a higher station.18

In some centers, direct forceps delivery from the OP position is preferred over an attempt at vacuum delivery, because in contemporary obstetric practice most centers do not permit the sequential use of vacuum followed by forceps (due to the higher rate of fetal trauma of combination operative delivery). Since vacuum delivery of the fetus in the OP position has a greater rate of failure than forceps, it may be best to initiate operative vaginal delivery of the fetus in the OP position with forceps. If vacuum is used to attempt a vaginal delivery and fails due to too many pop-offs, a CD would be the next step.

Take action when needed to optimize outcomes

The persistent OP position is associated with a longer second stage of labor. It is common during a change of shift for an obstetrician to sign out to the on-coming clinician a case of a prolonged second stage with the fetus in the OP position. In this situation, the on-coming clinician cannot wait hour after hour after hour hoping for a spontaneous delivery. If the on-coming clinician has a clear plan of how to deal with the persistent OP position—including ultrasound confirmation of position and physical examination to determine station, fetal size and adequacy of the pelvis, and timely selection of a delivery technique—the adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes sometimes caused by the persistent OP position will be minimized.

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

The consulting obstetrician performed a transabdominal ultrasound and observed the fetal orbits were facing the transducer, confirming an OP position. On physical examination, the station was +3/5, and the fetal weight was confirmed to be approximately 8 lb. The obstetrician recommended a direct forceps delivery from the OP position. The patient and CNM agreed with the plan.

The obstetrician applied Simpson forceps and performed a mediolateral episiotomy just prior to delivery of the head. Following delivery, the rectal sphincter and anal mucosa were intact and the episiotomy was repaired. The newborn, safely delivered, and the mother, having avoided a CD, were transferred to the postpartum floor later in the day.

- Cheng YW, Hubbard A, Caughey AB, et al. The association between persistent fetal occiput posterior position and perinatal outcomes: An example of propensity score and covariate distance matching. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:656-663.

- Cheng YW, Shaffer BL, Caughey AB. Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: a retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:563-568.

- Ponkey SE, Cohen AP, Heffner LJ, et al. Persistent fetal occiput posterior position: obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:915-920.

- Barth WH Jr. Persistent occiput posterior. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:695-709.

- Cheng YW, Shaffer BL, Caughey AB. The association between persistent occiput posterior position and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:837-844.

- Ghi T, Dall’Asta A, Masturzo B, et al. Randomised Italian sonography for occiput position trial ante vacuum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:699-705.

- Bellussi F, Ghi T, Youssef A, et al. The use of intrapartum ultrasound to diagnose malpositions and cephalic malpresentations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:633-641.

- Ramphul M, Ooi PV, Burke G, et al. Instrumental delivery and ultrasound: a multicenter randomised controlled trial of ultrasound assessment of the fetal head position versus standard of care as an approach to prevent morbidity at instrumental delivery. BJOG. 2014;121:1029-1038.

- Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Barbera A, et al. Occiput posterior position diagnosis: vaginal examination or intrapartum sonography? A clinical review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:520-526.

- Akmal S, Tsoi E, Kaemtas N, et al. Intrapartum sonography to determine fetal head position. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;12:172-177.

- Ghi T, Eggebo T, Lees C, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: intrapartum ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:128-139.

- Phipps H, de Vries B, Hyett J, et al. Prophylactic manual rotation for fetal malposition to reduce operative delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD009298.

- Le Ray C, Serres P, Schmitz T, et al. Manual rotation in occiput posterior or transverse positions. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:873-879.

- Shaffer BL, Cheng YW, Vargas JE, et al. Manual rotation to reduce caesarean delivery in persistent occiput posterior or transverse position. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:65-72.

- Bertholdt C, Gauchotte E, Dap M, et al. Predictors of successful manual rotation for occiput posterior positions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;144:210–215.

- Irving FC. A Textbook of Obstetrics. New York, NY: Macmillan, NY; 1936:426-428.

- Merriam AA, Ananth CV, Wright JD, et al. Trends in operative vaginal delivery, 2005–2013: a population-based study. BJOG. 2017;124:1365-1372.

- Verhoeven CJ, Nuij C, Janssen-Rolf CR, et al. Predictors of failure of vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:29-34.

- Cheng YW, Hubbard A, Caughey AB, et al. The association between persistent fetal occiput posterior position and perinatal outcomes: An example of propensity score and covariate distance matching. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:656-663.

- Cheng YW, Shaffer BL, Caughey AB. Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: a retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:563-568.

- Ponkey SE, Cohen AP, Heffner LJ, et al. Persistent fetal occiput posterior position: obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:915-920.

- Barth WH Jr. Persistent occiput posterior. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:695-709.

- Cheng YW, Shaffer BL, Caughey AB. The association between persistent occiput posterior position and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:837-844.

- Ghi T, Dall’Asta A, Masturzo B, et al. Randomised Italian sonography for occiput position trial ante vacuum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:699-705.

- Bellussi F, Ghi T, Youssef A, et al. The use of intrapartum ultrasound to diagnose malpositions and cephalic malpresentations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:633-641.

- Ramphul M, Ooi PV, Burke G, et al. Instrumental delivery and ultrasound: a multicenter randomised controlled trial of ultrasound assessment of the fetal head position versus standard of care as an approach to prevent morbidity at instrumental delivery. BJOG. 2014;121:1029-1038.

- Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Barbera A, et al. Occiput posterior position diagnosis: vaginal examination or intrapartum sonography? A clinical review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:520-526.

- Akmal S, Tsoi E, Kaemtas N, et al. Intrapartum sonography to determine fetal head position. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;12:172-177.

- Ghi T, Eggebo T, Lees C, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: intrapartum ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:128-139.

- Phipps H, de Vries B, Hyett J, et al. Prophylactic manual rotation for fetal malposition to reduce operative delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD009298.

- Le Ray C, Serres P, Schmitz T, et al. Manual rotation in occiput posterior or transverse positions. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:873-879.

- Shaffer BL, Cheng YW, Vargas JE, et al. Manual rotation to reduce caesarean delivery in persistent occiput posterior or transverse position. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:65-72.

- Bertholdt C, Gauchotte E, Dap M, et al. Predictors of successful manual rotation for occiput posterior positions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;144:210–215.

- Irving FC. A Textbook of Obstetrics. New York, NY: Macmillan, NY; 1936:426-428.

- Merriam AA, Ananth CV, Wright JD, et al. Trends in operative vaginal delivery, 2005–2013: a population-based study. BJOG. 2017;124:1365-1372.

- Verhoeven CJ, Nuij C, Janssen-Rolf CR, et al. Predictors of failure of vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:29-34.

No increased pregnancy loss risk for women conceiving soon after stillbirth

according to authors of a large, international observational study.

There was no significantly increased risk of stillbirth, preterm birth, or small-for-gestational-age birth in the next pregnancy for women who conceived in that 12-month time period, according to results of the study, which was based on birth records for nearly 14,500 women in Finland, Norway, and Australia.

“We hope that our findings can provide reassurance to women who wish to become pregnant or unexpectedly become pregnant shortly after a stillbirth,” study author Annette K. Regan, PhD, of Curtin University, Perth, Australia, said in a statement on the study, which appears in The Lancet.

Judette Marie Louis, MD, MPH, said that while data are conflicting on optimal interpregnancy interval following stillbirth, large population-based studies such as this one may provide an indication of the relative safety of an interval of 12 months or less. (She was not involved in this study.)

“This paper is good news for a lot of women,” Dr. Louis, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of South Florida, Tampa, said in an interview. “After a stillbirth, it’s such a traumatic experience that some do want to move on, and these findings suggest that, yes, you don’t have to wait that long to have a successful pregnancy.”

These results are for women living in relatively high-income countries, so the findings might not apply to every population, she added. Dr. Louis was the first author of a recent interpregnancy care consensus statement by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and was asked to comment on this study.

The World Health Organization recommends interpregnancy intervals of 2 years or more after live births and 6 months or more after miscarriage, but currently has no specific recommendations on the optimal interpregnancy interval after a stillbirth, according to Dr. Regan and her colleagues.

“Because length of gestation might affect nutrient concentrations and health status in women, it is plausible that the optimal interval after stillbirth is somewhere between the optimal interval after miscarriage and live birth,” they said in their report.

Researchers for two previous studies also have reported on the link between the interpregnancy interval after stillbirth and birth outcomes in the next pregnancy, but neither was specifically designed to evaluate that outcome, they added.

Dr. Regan and her coauthors used birth record data spanning several decades from three high-income countries to identify 14,452 women who had stillbirths. Of those, 63% conceived within the next 12 months, and for 37%, it was as early as 6 months.

Overall, 2% of the subsequent pregnancies ended in stillbirth, while 9% were small-for-gestational-age and 18% were preterm, according to the report.

In analyses adjusted for variables such as age, smoking, and education level, there was no association between short interpregnancy intervals and subsequent stillbirths, compared with longer intervals (24-59 months), with odds ratios of 1.09 for an interval shorter than 6 months and 0.90 for 6-11 months.

Likewise, there was no link between shorter intervals and subsequent small-for-gestational-age birth, with odds ratios of 0.66 for less than 6 months and 0.64 for 6-11 months, and no link between interval and subsequent preterm births, with odds ratios of 0.91 for both short-interval groups.

That data could be useful to health care providers who do postpartum counseling after stillbirths, and could potentially inform future recommendations on pregnancy spacing, Dr. Regan and her coauthors said.

“These results apply to a large proportion of women conceiving after a stillbirth,” they noted.

This study included countries with access to universal health care, with populations that are mostly white, so the results may not apply to low- or middle-income countries without universal health care or with significant ethnic minority populations, they added.

Dr. Regan and her colleagues declared no competing interests related to the study, which was funded the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, among other sources.

SOURCE: Regan AK et al. Lancet. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32266-9.

The interval between pregnancy loss and the next conception may be less important than previously assumed, based on the results of this and other recent studies, according to Mark A Klebanoff, MD, MPH.

“Rather than adhering to hard and fast rules, clinical recommendations should consider a woman’s current health status, her current age in conjunction with her desires regarding child spacing and ultimate family size, and particularly following a loss, her emotional readiness to become pregnant again,” he said in a commentary accompanying the article by Regan et al.

However, these results are specific to high-income countries, and might not extrapolate to women in “less favorable situations” where poor access to quality medical and obstetric care, malnutrition, and untreated chronic conditions are more common, Dr. Klebanoff added.

Another limitation of the study, acknowledged by Regan and coauthors, is the relatively small number of stillbirths in subsequent pregnancies (228) despite this being the largest study of its kind to date.

“The fairly small number of women included in this report dictates that replication, probably using other large, linked, population-level databases, is required,” Dr. Klebanoff said in his commentary.

Dr. Klebanoff is with the Center for Perinatal Research, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; and the departments of pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology at the College of Medicine, and division of epidemiology at the College of Public Health, at The Ohio State University, all in Columbus. This is a summarization of his commentary (Lancet. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32430-9 ). Dr. Klebanoff said he had a pending grant application to the National Institutes of Health to study the association between interpregnancy interval and birth outcomes, and had no other competing interests.

The interval between pregnancy loss and the next conception may be less important than previously assumed, based on the results of this and other recent studies, according to Mark A Klebanoff, MD, MPH.

“Rather than adhering to hard and fast rules, clinical recommendations should consider a woman’s current health status, her current age in conjunction with her desires regarding child spacing and ultimate family size, and particularly following a loss, her emotional readiness to become pregnant again,” he said in a commentary accompanying the article by Regan et al.

However, these results are specific to high-income countries, and might not extrapolate to women in “less favorable situations” where poor access to quality medical and obstetric care, malnutrition, and untreated chronic conditions are more common, Dr. Klebanoff added.

Another limitation of the study, acknowledged by Regan and coauthors, is the relatively small number of stillbirths in subsequent pregnancies (228) despite this being the largest study of its kind to date.

“The fairly small number of women included in this report dictates that replication, probably using other large, linked, population-level databases, is required,” Dr. Klebanoff said in his commentary.

Dr. Klebanoff is with the Center for Perinatal Research, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; and the departments of pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology at the College of Medicine, and division of epidemiology at the College of Public Health, at The Ohio State University, all in Columbus. This is a summarization of his commentary (Lancet. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32430-9 ). Dr. Klebanoff said he had a pending grant application to the National Institutes of Health to study the association between interpregnancy interval and birth outcomes, and had no other competing interests.

The interval between pregnancy loss and the next conception may be less important than previously assumed, based on the results of this and other recent studies, according to Mark A Klebanoff, MD, MPH.

“Rather than adhering to hard and fast rules, clinical recommendations should consider a woman’s current health status, her current age in conjunction with her desires regarding child spacing and ultimate family size, and particularly following a loss, her emotional readiness to become pregnant again,” he said in a commentary accompanying the article by Regan et al.

However, these results are specific to high-income countries, and might not extrapolate to women in “less favorable situations” where poor access to quality medical and obstetric care, malnutrition, and untreated chronic conditions are more common, Dr. Klebanoff added.

Another limitation of the study, acknowledged by Regan and coauthors, is the relatively small number of stillbirths in subsequent pregnancies (228) despite this being the largest study of its kind to date.

“The fairly small number of women included in this report dictates that replication, probably using other large, linked, population-level databases, is required,” Dr. Klebanoff said in his commentary.

Dr. Klebanoff is with the Center for Perinatal Research, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; and the departments of pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology at the College of Medicine, and division of epidemiology at the College of Public Health, at The Ohio State University, all in Columbus. This is a summarization of his commentary (Lancet. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32430-9 ). Dr. Klebanoff said he had a pending grant application to the National Institutes of Health to study the association between interpregnancy interval and birth outcomes, and had no other competing interests.

according to authors of a large, international observational study.

There was no significantly increased risk of stillbirth, preterm birth, or small-for-gestational-age birth in the next pregnancy for women who conceived in that 12-month time period, according to results of the study, which was based on birth records for nearly 14,500 women in Finland, Norway, and Australia.

“We hope that our findings can provide reassurance to women who wish to become pregnant or unexpectedly become pregnant shortly after a stillbirth,” study author Annette K. Regan, PhD, of Curtin University, Perth, Australia, said in a statement on the study, which appears in The Lancet.