User login

Knotless, absorbable sutures best staples for postcesarean skin closure

LAS VEGAS – compared with staples, in a single-site, retrospective study.

For women whose skin incisions were closed with knotless sutures, mean surgical time was 38 minutes; for women who received a staple closure, mean surgical time was 44 minutes (P less than .001). Also, fewer women whose incisions were closed with knotless sutures experienced surgical bleeding greater than 1,000 mL, compared with those who received staples (0.3% vs. 3.0%; P less than .001).

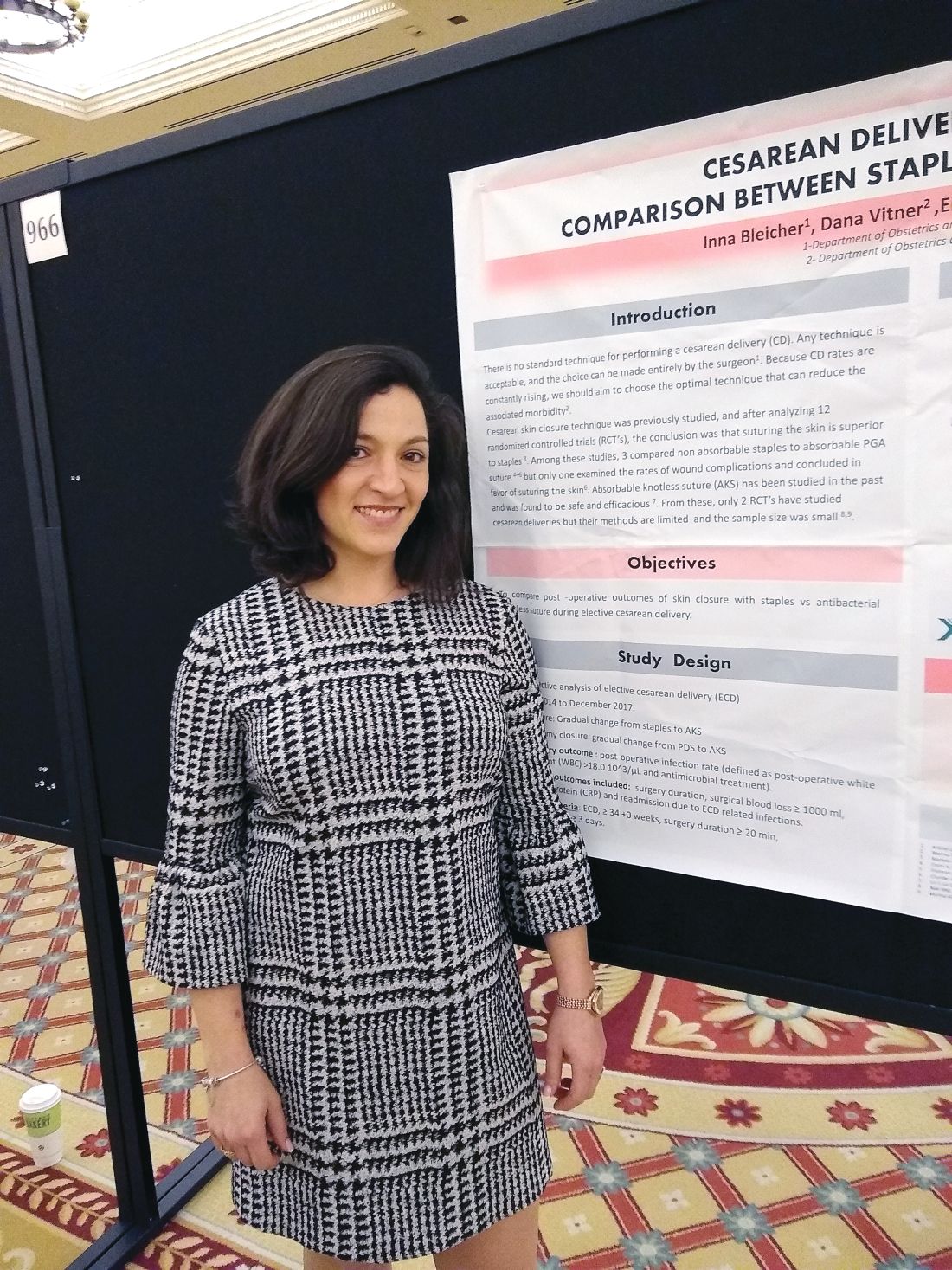

Two previous randomized, controlled trials comparing knotless sutures with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery were small and had methodological limitations, Inna Bleicher, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues reviewed records from 2,173 elective cesarean deliveries over a period of 4 years. Absorbable, antibacterial, knotless sutures were used for closure for 1,172 women, while staples were used for the remaining 1,001 women.

Over the study period, Dr. Bleicher noted that there was a gradual transition from the use of staples to absorbable, knotless sutures, which also were increasingly used for the hysterotomy closure. She added that, in conversation with peers at Bnai-Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where she practices as an ob.gyn, she’s found that physicians find the sutures easy and quick to use, because the sutures are double ended, allowing the possibility for two operators to work together in wound closure.

The study’s primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative infection, defined as postoperative white blood count greater than 18,000 per microliter and antimicrobial treatment. Secondary outcome measures included C-reactive protein levels, hospital readmission for infection related to the delivery, duration of surgery, and surgical blood loss estimated at 1,000 mL or more.

A higher proportion of women in the staple closure group than the knotless suture group required postsurgical antibiotic treatment (11% vs. 10%), but this difference didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .243).

There were no significant differences in the groups in terms of maternal age (about 32 years), or gestational age at delivery (about 39 weeks).

“Our results suggest that cesarean scar skin closure with antibacterial knotless sutures did not increase, and may even reduce, the rates of postoperative infection, morbidity, surgical blood loss, and may shorten operation time,” wrote Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues.

Dr. Bleicher reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bleicher I et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S622, Abstract 966.

LAS VEGAS – compared with staples, in a single-site, retrospective study.

For women whose skin incisions were closed with knotless sutures, mean surgical time was 38 minutes; for women who received a staple closure, mean surgical time was 44 minutes (P less than .001). Also, fewer women whose incisions were closed with knotless sutures experienced surgical bleeding greater than 1,000 mL, compared with those who received staples (0.3% vs. 3.0%; P less than .001).

Two previous randomized, controlled trials comparing knotless sutures with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery were small and had methodological limitations, Inna Bleicher, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues reviewed records from 2,173 elective cesarean deliveries over a period of 4 years. Absorbable, antibacterial, knotless sutures were used for closure for 1,172 women, while staples were used for the remaining 1,001 women.

Over the study period, Dr. Bleicher noted that there was a gradual transition from the use of staples to absorbable, knotless sutures, which also were increasingly used for the hysterotomy closure. She added that, in conversation with peers at Bnai-Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where she practices as an ob.gyn, she’s found that physicians find the sutures easy and quick to use, because the sutures are double ended, allowing the possibility for two operators to work together in wound closure.

The study’s primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative infection, defined as postoperative white blood count greater than 18,000 per microliter and antimicrobial treatment. Secondary outcome measures included C-reactive protein levels, hospital readmission for infection related to the delivery, duration of surgery, and surgical blood loss estimated at 1,000 mL or more.

A higher proportion of women in the staple closure group than the knotless suture group required postsurgical antibiotic treatment (11% vs. 10%), but this difference didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .243).

There were no significant differences in the groups in terms of maternal age (about 32 years), or gestational age at delivery (about 39 weeks).

“Our results suggest that cesarean scar skin closure with antibacterial knotless sutures did not increase, and may even reduce, the rates of postoperative infection, morbidity, surgical blood loss, and may shorten operation time,” wrote Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues.

Dr. Bleicher reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bleicher I et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S622, Abstract 966.

LAS VEGAS – compared with staples, in a single-site, retrospective study.

For women whose skin incisions were closed with knotless sutures, mean surgical time was 38 minutes; for women who received a staple closure, mean surgical time was 44 minutes (P less than .001). Also, fewer women whose incisions were closed with knotless sutures experienced surgical bleeding greater than 1,000 mL, compared with those who received staples (0.3% vs. 3.0%; P less than .001).

Two previous randomized, controlled trials comparing knotless sutures with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery were small and had methodological limitations, Inna Bleicher, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues reviewed records from 2,173 elective cesarean deliveries over a period of 4 years. Absorbable, antibacterial, knotless sutures were used for closure for 1,172 women, while staples were used for the remaining 1,001 women.

Over the study period, Dr. Bleicher noted that there was a gradual transition from the use of staples to absorbable, knotless sutures, which also were increasingly used for the hysterotomy closure. She added that, in conversation with peers at Bnai-Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where she practices as an ob.gyn, she’s found that physicians find the sutures easy and quick to use, because the sutures are double ended, allowing the possibility for two operators to work together in wound closure.

The study’s primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative infection, defined as postoperative white blood count greater than 18,000 per microliter and antimicrobial treatment. Secondary outcome measures included C-reactive protein levels, hospital readmission for infection related to the delivery, duration of surgery, and surgical blood loss estimated at 1,000 mL or more.

A higher proportion of women in the staple closure group than the knotless suture group required postsurgical antibiotic treatment (11% vs. 10%), but this difference didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .243).

There were no significant differences in the groups in terms of maternal age (about 32 years), or gestational age at delivery (about 39 weeks).

“Our results suggest that cesarean scar skin closure with antibacterial knotless sutures did not increase, and may even reduce, the rates of postoperative infection, morbidity, surgical blood loss, and may shorten operation time,” wrote Dr. Bleicher and her colleagues.

Dr. Bleicher reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bleicher I et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S622, Abstract 966.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Rapid preeclampsia urine test is simple, noninvasive

according to a research letter in EClinicalMedicine.

The research team, led by Kara M. Rood, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus, said that their pragmatic study in 346 consecutive pregnant patients demonstrated that the test is not only inexpensive, but also easy to use and well received by the nursing staff. A positive Congo Red Dot Rapid Paper Test had 80% sensitivity, 89% specificity, 92% negative predictive value and 87% accuracy to correctly diagnose preeclampsia.

The patients were recruited from the labor and delivery triage unit at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Certain misfolded proteins typically are found in the urine of women with preeclampsia, so in prior research, the researchers had hypothesized that a urine test that could detect these proteins would carry “diagnostic and prognostic potential for” preeclampsia. The researchers were able to show that this was possible with a laboratory test that used Congo Red dye because those misfolded proteins bind with it. This current study explored the accuracy of a 3-minute, point-of-care urine test that uses a dot of Congo Red dye on a piece of paper.

Other serum and urine tests, which often have been more complicated or time intensive, have failed to gain traction in real-world practice, as well as in low-resource countries where mortality and morbidity from preeclampsia are highest, the authors noted. By contrast, the researchers hope the rapid paper test they studied in the current research will fulfill that unmet need.

The study was funded by the Saving Lives at Birth grant and a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Rood KM et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.02.004.

according to a research letter in EClinicalMedicine.

The research team, led by Kara M. Rood, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus, said that their pragmatic study in 346 consecutive pregnant patients demonstrated that the test is not only inexpensive, but also easy to use and well received by the nursing staff. A positive Congo Red Dot Rapid Paper Test had 80% sensitivity, 89% specificity, 92% negative predictive value and 87% accuracy to correctly diagnose preeclampsia.

The patients were recruited from the labor and delivery triage unit at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Certain misfolded proteins typically are found in the urine of women with preeclampsia, so in prior research, the researchers had hypothesized that a urine test that could detect these proteins would carry “diagnostic and prognostic potential for” preeclampsia. The researchers were able to show that this was possible with a laboratory test that used Congo Red dye because those misfolded proteins bind with it. This current study explored the accuracy of a 3-minute, point-of-care urine test that uses a dot of Congo Red dye on a piece of paper.

Other serum and urine tests, which often have been more complicated or time intensive, have failed to gain traction in real-world practice, as well as in low-resource countries where mortality and morbidity from preeclampsia are highest, the authors noted. By contrast, the researchers hope the rapid paper test they studied in the current research will fulfill that unmet need.

The study was funded by the Saving Lives at Birth grant and a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Rood KM et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.02.004.

according to a research letter in EClinicalMedicine.

The research team, led by Kara M. Rood, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Ohio State University, Columbus, said that their pragmatic study in 346 consecutive pregnant patients demonstrated that the test is not only inexpensive, but also easy to use and well received by the nursing staff. A positive Congo Red Dot Rapid Paper Test had 80% sensitivity, 89% specificity, 92% negative predictive value and 87% accuracy to correctly diagnose preeclampsia.

The patients were recruited from the labor and delivery triage unit at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Certain misfolded proteins typically are found in the urine of women with preeclampsia, so in prior research, the researchers had hypothesized that a urine test that could detect these proteins would carry “diagnostic and prognostic potential for” preeclampsia. The researchers were able to show that this was possible with a laboratory test that used Congo Red dye because those misfolded proteins bind with it. This current study explored the accuracy of a 3-minute, point-of-care urine test that uses a dot of Congo Red dye on a piece of paper.

Other serum and urine tests, which often have been more complicated or time intensive, have failed to gain traction in real-world practice, as well as in low-resource countries where mortality and morbidity from preeclampsia are highest, the authors noted. By contrast, the researchers hope the rapid paper test they studied in the current research will fulfill that unmet need.

The study was funded by the Saving Lives at Birth grant and a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Rood KM et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.02.004.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Access to abortion care: Facts matter

In 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States recognized a constitutional right to abortion in the landmark case of Roe v Wade. The Court held that states may regulate, but not ban, abortion after the first trimester, for the purpose of protecting the woman’s health. The Court further indicated that states’ interest in “potential life” could be the basis for abortion regulations only after the point of viability, at which point states may ban abortion except when necessary to preserve the life or health of the woman.1 In 1992, the Court decided Planned Parenthood v Casey and eliminated the trimester framework while upholding women’s right to abortion.2 As with Roe v Wade, the Casey decision held that there must be an exception for the woman’s health and life.

Fast forward to 2019

New York passed a law in 2019,3 and Virginia had a proposed law that was recently tabled by the House of Delegates,4 both related to abortions performed past the first trimester.

New York. The New York law supports legal abortion by a licensed practitioner within 24 weeks of pregnancy commencement. After 24 weeks’ gestation, if there is “an absence of fetal viability, or the abortion is necessary to protect the patient’s life or health” then termination is permissible.3

Virginia. Previously, Virginia had abortion laws that required significant measures to approve a third-trimester abortion, including certification by 3 physicians that the procedure is necessary to “save mother’s life or [prevent] substantial and irremediable impairment of mental or physical health of the mother.”5 Violation included potential for jail time and a significant monetary fine.

The proposed bill, now tabled, was introduced by delegate Kathy Tran (House Bill 2491) and would have rolled back many requirements of the old law, including the 24-hour waiting period and mandate for second-trimester abortions to occur in a hospital.

The controversy centered on a provision concerning third-trimester abortions. Specifically, the proposed bill would only have required 1 doctor to deem the abortion necessary and would have removed the “substantially and irremediably” qualifier. Thus, abortions would be allowed in cases in which the woman’s mental or physical health was threatened, even in cases in which the potential damage may be reversible.5

The facts

Misconceptions about abortion care can be dangerous and work to further stigmatize our patients who may need an abortion or who have had an abortion in the past. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently published a document discussing facts regarding abortion care later in pregnancy. The document (aptly named “Facts are Important”) enforces that policy be based on medical science and facts, and not simply driven by political beliefs.6

Fact. The majority of abortions occur prior to 21 weeks, before viability:

- 91.1% of abortions occur at or before 13 weeks’ gestation7

- only 1.3% of abortions occur at or after 21 weeks’ gestation7

- abortions occurring later in the second trimester or in the third trimester are very uncommon.

Fact. The language “late-term abortion” has no medical definition, is not used in a clinical setting or to describe the delivery of abortion care later in pregnancy in any medical institution.6

Fact. Many of the abortions occurring later in pregnancy are due to fetal anomalies incompatible with life. Anomalies can include lack of a major portion of the brain (anencephaly), bilateral renal agenesis, some skeletal dysplasias, and other chromosomal abnormalities. These are cases in which death is likely before or shortly after birth, with great potential for suffering of both the fetus and the family.

Fact. The need for abortion also may be due to serious complications that will likely cause significant morbidity or mortality to the woman. These complications, in turn, reduce the likelihood of survival of the fetus.

It is thus vital for women to have the freedom to evaluate their medical circumstance with their provider and, using evidence, make informed health care decisions—which may include abortion, induction of labor, or cesarean delivery in some circumstances. Access to accurate, complete information and care is a right bestowed amongst all women and “must never be constrained by politicians.”6 We must focus on medically appropriate and compassionate care for both the family and the fetus.

Use your voice

As clinicians, we are trusted members of our communities. The New York law and the prior proposed Virginia law emphasize important access to care for women and their families. Abortions at a later gestational age are a rare event but are most often performed when the health or life of the mother is at risk or the fetus has an anomaly incompatible with life.

We urge you to use your voice to correct misconceptions, whether in your office with your patients or colleagues or in your communities, locally and nationally. Email your friends and colleagues about ACOG’s “Facts are Important” document, organize a grand rounds on the topic, and utilize social media to share facts about abortion care. These actions support our patients and can make an impact by spreading factual information.

For more facts and figures about abortion laws, visit the website of the Guttmacher Institute.

- Roe v Wade, 410 US 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 US 833 (1992).

- New York abortion laws. FindLaw website. https://statelaws.findlaw.com/new-york-law/new-york-abortion-laws.html. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- North A. The controversy around Virginia’s new abortion bill, explained. https://www.vox.com/2019/2/1/18205428/virginia-abortion-bill-kathy-tran-ralph-northam Accessed March 13, 2019.

- Virginia abortion laws. FindLaw website. https://statelaws.findlaw.com/virginia-law/virginia-abortion-laws.html. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Facts are important. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outreach/Facts-Are-Important_Abortion-Care-Later-In-Pregnancy-February-2019-College.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190214T2242210541. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Jatlaoui TC, Boutot ME, Mandel MG, et al. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(13):1-45.

In 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States recognized a constitutional right to abortion in the landmark case of Roe v Wade. The Court held that states may regulate, but not ban, abortion after the first trimester, for the purpose of protecting the woman’s health. The Court further indicated that states’ interest in “potential life” could be the basis for abortion regulations only after the point of viability, at which point states may ban abortion except when necessary to preserve the life or health of the woman.1 In 1992, the Court decided Planned Parenthood v Casey and eliminated the trimester framework while upholding women’s right to abortion.2 As with Roe v Wade, the Casey decision held that there must be an exception for the woman’s health and life.

Fast forward to 2019

New York passed a law in 2019,3 and Virginia had a proposed law that was recently tabled by the House of Delegates,4 both related to abortions performed past the first trimester.

New York. The New York law supports legal abortion by a licensed practitioner within 24 weeks of pregnancy commencement. After 24 weeks’ gestation, if there is “an absence of fetal viability, or the abortion is necessary to protect the patient’s life or health” then termination is permissible.3

Virginia. Previously, Virginia had abortion laws that required significant measures to approve a third-trimester abortion, including certification by 3 physicians that the procedure is necessary to “save mother’s life or [prevent] substantial and irremediable impairment of mental or physical health of the mother.”5 Violation included potential for jail time and a significant monetary fine.

The proposed bill, now tabled, was introduced by delegate Kathy Tran (House Bill 2491) and would have rolled back many requirements of the old law, including the 24-hour waiting period and mandate for second-trimester abortions to occur in a hospital.

The controversy centered on a provision concerning third-trimester abortions. Specifically, the proposed bill would only have required 1 doctor to deem the abortion necessary and would have removed the “substantially and irremediably” qualifier. Thus, abortions would be allowed in cases in which the woman’s mental or physical health was threatened, even in cases in which the potential damage may be reversible.5

The facts

Misconceptions about abortion care can be dangerous and work to further stigmatize our patients who may need an abortion or who have had an abortion in the past. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently published a document discussing facts regarding abortion care later in pregnancy. The document (aptly named “Facts are Important”) enforces that policy be based on medical science and facts, and not simply driven by political beliefs.6

Fact. The majority of abortions occur prior to 21 weeks, before viability:

- 91.1% of abortions occur at or before 13 weeks’ gestation7

- only 1.3% of abortions occur at or after 21 weeks’ gestation7

- abortions occurring later in the second trimester or in the third trimester are very uncommon.

Fact. The language “late-term abortion” has no medical definition, is not used in a clinical setting or to describe the delivery of abortion care later in pregnancy in any medical institution.6

Fact. Many of the abortions occurring later in pregnancy are due to fetal anomalies incompatible with life. Anomalies can include lack of a major portion of the brain (anencephaly), bilateral renal agenesis, some skeletal dysplasias, and other chromosomal abnormalities. These are cases in which death is likely before or shortly after birth, with great potential for suffering of both the fetus and the family.

Fact. The need for abortion also may be due to serious complications that will likely cause significant morbidity or mortality to the woman. These complications, in turn, reduce the likelihood of survival of the fetus.

It is thus vital for women to have the freedom to evaluate their medical circumstance with their provider and, using evidence, make informed health care decisions—which may include abortion, induction of labor, or cesarean delivery in some circumstances. Access to accurate, complete information and care is a right bestowed amongst all women and “must never be constrained by politicians.”6 We must focus on medically appropriate and compassionate care for both the family and the fetus.

Use your voice

As clinicians, we are trusted members of our communities. The New York law and the prior proposed Virginia law emphasize important access to care for women and their families. Abortions at a later gestational age are a rare event but are most often performed when the health or life of the mother is at risk or the fetus has an anomaly incompatible with life.

We urge you to use your voice to correct misconceptions, whether in your office with your patients or colleagues or in your communities, locally and nationally. Email your friends and colleagues about ACOG’s “Facts are Important” document, organize a grand rounds on the topic, and utilize social media to share facts about abortion care. These actions support our patients and can make an impact by spreading factual information.

For more facts and figures about abortion laws, visit the website of the Guttmacher Institute.

In 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States recognized a constitutional right to abortion in the landmark case of Roe v Wade. The Court held that states may regulate, but not ban, abortion after the first trimester, for the purpose of protecting the woman’s health. The Court further indicated that states’ interest in “potential life” could be the basis for abortion regulations only after the point of viability, at which point states may ban abortion except when necessary to preserve the life or health of the woman.1 In 1992, the Court decided Planned Parenthood v Casey and eliminated the trimester framework while upholding women’s right to abortion.2 As with Roe v Wade, the Casey decision held that there must be an exception for the woman’s health and life.

Fast forward to 2019

New York passed a law in 2019,3 and Virginia had a proposed law that was recently tabled by the House of Delegates,4 both related to abortions performed past the first trimester.

New York. The New York law supports legal abortion by a licensed practitioner within 24 weeks of pregnancy commencement. After 24 weeks’ gestation, if there is “an absence of fetal viability, or the abortion is necessary to protect the patient’s life or health” then termination is permissible.3

Virginia. Previously, Virginia had abortion laws that required significant measures to approve a third-trimester abortion, including certification by 3 physicians that the procedure is necessary to “save mother’s life or [prevent] substantial and irremediable impairment of mental or physical health of the mother.”5 Violation included potential for jail time and a significant monetary fine.

The proposed bill, now tabled, was introduced by delegate Kathy Tran (House Bill 2491) and would have rolled back many requirements of the old law, including the 24-hour waiting period and mandate for second-trimester abortions to occur in a hospital.

The controversy centered on a provision concerning third-trimester abortions. Specifically, the proposed bill would only have required 1 doctor to deem the abortion necessary and would have removed the “substantially and irremediably” qualifier. Thus, abortions would be allowed in cases in which the woman’s mental or physical health was threatened, even in cases in which the potential damage may be reversible.5

The facts

Misconceptions about abortion care can be dangerous and work to further stigmatize our patients who may need an abortion or who have had an abortion in the past. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently published a document discussing facts regarding abortion care later in pregnancy. The document (aptly named “Facts are Important”) enforces that policy be based on medical science and facts, and not simply driven by political beliefs.6

Fact. The majority of abortions occur prior to 21 weeks, before viability:

- 91.1% of abortions occur at or before 13 weeks’ gestation7

- only 1.3% of abortions occur at or after 21 weeks’ gestation7

- abortions occurring later in the second trimester or in the third trimester are very uncommon.

Fact. The language “late-term abortion” has no medical definition, is not used in a clinical setting or to describe the delivery of abortion care later in pregnancy in any medical institution.6

Fact. Many of the abortions occurring later in pregnancy are due to fetal anomalies incompatible with life. Anomalies can include lack of a major portion of the brain (anencephaly), bilateral renal agenesis, some skeletal dysplasias, and other chromosomal abnormalities. These are cases in which death is likely before or shortly after birth, with great potential for suffering of both the fetus and the family.

Fact. The need for abortion also may be due to serious complications that will likely cause significant morbidity or mortality to the woman. These complications, in turn, reduce the likelihood of survival of the fetus.

It is thus vital for women to have the freedom to evaluate their medical circumstance with their provider and, using evidence, make informed health care decisions—which may include abortion, induction of labor, or cesarean delivery in some circumstances. Access to accurate, complete information and care is a right bestowed amongst all women and “must never be constrained by politicians.”6 We must focus on medically appropriate and compassionate care for both the family and the fetus.

Use your voice

As clinicians, we are trusted members of our communities. The New York law and the prior proposed Virginia law emphasize important access to care for women and their families. Abortions at a later gestational age are a rare event but are most often performed when the health or life of the mother is at risk or the fetus has an anomaly incompatible with life.

We urge you to use your voice to correct misconceptions, whether in your office with your patients or colleagues or in your communities, locally and nationally. Email your friends and colleagues about ACOG’s “Facts are Important” document, organize a grand rounds on the topic, and utilize social media to share facts about abortion care. These actions support our patients and can make an impact by spreading factual information.

For more facts and figures about abortion laws, visit the website of the Guttmacher Institute.

- Roe v Wade, 410 US 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 US 833 (1992).

- New York abortion laws. FindLaw website. https://statelaws.findlaw.com/new-york-law/new-york-abortion-laws.html. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- North A. The controversy around Virginia’s new abortion bill, explained. https://www.vox.com/2019/2/1/18205428/virginia-abortion-bill-kathy-tran-ralph-northam Accessed March 13, 2019.

- Virginia abortion laws. FindLaw website. https://statelaws.findlaw.com/virginia-law/virginia-abortion-laws.html. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Facts are important. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outreach/Facts-Are-Important_Abortion-Care-Later-In-Pregnancy-February-2019-College.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190214T2242210541. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Jatlaoui TC, Boutot ME, Mandel MG, et al. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(13):1-45.

- Roe v Wade, 410 US 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 US 833 (1992).

- New York abortion laws. FindLaw website. https://statelaws.findlaw.com/new-york-law/new-york-abortion-laws.html. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- North A. The controversy around Virginia’s new abortion bill, explained. https://www.vox.com/2019/2/1/18205428/virginia-abortion-bill-kathy-tran-ralph-northam Accessed March 13, 2019.

- Virginia abortion laws. FindLaw website. https://statelaws.findlaw.com/virginia-law/virginia-abortion-laws.html. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Facts are important. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outreach/Facts-Are-Important_Abortion-Care-Later-In-Pregnancy-February-2019-College.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190214T2242210541. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Jatlaoui TC, Boutot ME, Mandel MG, et al. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(13):1-45.

Raltegravir safe, effective in late pregnancy

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen that included the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL-ART) led to faster viral load (VL) reduction and a greater proportion of women with a VL of less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared with patients treated with an efavirenz-based ART (EFV-ART). There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to percentage of stillbirths, preterm delivery, or rates of HIV infection in the newborn.

“There are lots of advantages of these [integrase inhibitor] drugs, and we’d like to have pregnant women take advantage of them. The problem is, there’s no requirement of drug manufacturers to study the drugs in pregnancy. So these studies are put off until after the drug is licensed, and we’re playing catch-up,” Mark Mirochnick, MD, professor of pediatrics at Boston University, said in an interview. Dr. Mirochnick presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Another integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir, has a better resistance profile than that of raltegravir, but concerns over neural tube defects observed during a study in Botswana led both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to issue safety warnings for that drug. The current study did not raise concern, since it began at 20 weeks’ gestation, well after the period when neural tube defects might occur. “I think it just demonstrates that [integrase inhibitors] are safe in mid- to late-pregnancy,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

It remains to be seen whether a potential link to neural tube defects, if it is a real effect, is due to a specific drug or the mechanism of action of integrase inhibitors more generally. “It’s a question we don’t have an answer to. So you have to balance the potential benefits and potential risks, and that’s probably a decision best made by an individual woman and her care provider. Some women do very well on a particular regimen and they don’t want to change, and you run the risk when you change that you’ll get a viral rebound. What do you tell women who are on dolutegravir and are thinking about becoming pregnant? That’s a controversial question. There are risks with both courses,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

The study comprised 408 patients recruited from centers in Brazil, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, and the United States. The patients were between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation and had not previously received ART. They were randomized to RAL-ART or EFV-ART. About 12% of patients were Asian, 36% were black, 52% were Hispanic, and 1% were white.

Overall, 94% of patients on RAL-ART had a VL less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared to 84% of EFV-ART patients (P = .001). The effect appeared to be driven by patients who enrolled later in pregnancy: There was no significant difference in those enrolled in weeks 20-28, but suppression occurred in 93% of the RAL-ART group versus 71% of the EFV-ART group among those enrolled in weeks 29-37 (P = .04).

Tolerability was slightly better in the RAL-ART group, with 99% versus 97% of patients staying on their assigned therapy (P = .05). In both groups, 30% of women experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or higher, as did 25% of live-born infants in both groups.

A total of 92% of women in the RAL-ART group had a sustained VL response through delivery, compared with 64% in the EFV-ART group (P less than .001). The median time to achieving a VL less than 200 copies/mL was 8 days in the RAL-ART group and 15 days in the EFV-ART group (generalized log-rank test P less than .001).

There was one stillbirth in the EFV-ART arm and three in the RAL-ART arm, with 11% in the EFV-ART group having preterm delivery compared with 12% in the RAL-ART group. In addition, the proportion of HIV-infected infants was lower in the RAL-ART arm (1% versus 3%). These differences were not significant.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Glaxo/ViiV, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supplied study drugs. Dr. Mirochnick has received research funding from those companies.

SOURCE: Mark Mirochnick et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 39 LB.

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen that included the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL-ART) led to faster viral load (VL) reduction and a greater proportion of women with a VL of less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared with patients treated with an efavirenz-based ART (EFV-ART). There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to percentage of stillbirths, preterm delivery, or rates of HIV infection in the newborn.

“There are lots of advantages of these [integrase inhibitor] drugs, and we’d like to have pregnant women take advantage of them. The problem is, there’s no requirement of drug manufacturers to study the drugs in pregnancy. So these studies are put off until after the drug is licensed, and we’re playing catch-up,” Mark Mirochnick, MD, professor of pediatrics at Boston University, said in an interview. Dr. Mirochnick presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Another integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir, has a better resistance profile than that of raltegravir, but concerns over neural tube defects observed during a study in Botswana led both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to issue safety warnings for that drug. The current study did not raise concern, since it began at 20 weeks’ gestation, well after the period when neural tube defects might occur. “I think it just demonstrates that [integrase inhibitors] are safe in mid- to late-pregnancy,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

It remains to be seen whether a potential link to neural tube defects, if it is a real effect, is due to a specific drug or the mechanism of action of integrase inhibitors more generally. “It’s a question we don’t have an answer to. So you have to balance the potential benefits and potential risks, and that’s probably a decision best made by an individual woman and her care provider. Some women do very well on a particular regimen and they don’t want to change, and you run the risk when you change that you’ll get a viral rebound. What do you tell women who are on dolutegravir and are thinking about becoming pregnant? That’s a controversial question. There are risks with both courses,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

The study comprised 408 patients recruited from centers in Brazil, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, and the United States. The patients were between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation and had not previously received ART. They were randomized to RAL-ART or EFV-ART. About 12% of patients were Asian, 36% were black, 52% were Hispanic, and 1% were white.

Overall, 94% of patients on RAL-ART had a VL less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared to 84% of EFV-ART patients (P = .001). The effect appeared to be driven by patients who enrolled later in pregnancy: There was no significant difference in those enrolled in weeks 20-28, but suppression occurred in 93% of the RAL-ART group versus 71% of the EFV-ART group among those enrolled in weeks 29-37 (P = .04).

Tolerability was slightly better in the RAL-ART group, with 99% versus 97% of patients staying on their assigned therapy (P = .05). In both groups, 30% of women experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or higher, as did 25% of live-born infants in both groups.

A total of 92% of women in the RAL-ART group had a sustained VL response through delivery, compared with 64% in the EFV-ART group (P less than .001). The median time to achieving a VL less than 200 copies/mL was 8 days in the RAL-ART group and 15 days in the EFV-ART group (generalized log-rank test P less than .001).

There was one stillbirth in the EFV-ART arm and three in the RAL-ART arm, with 11% in the EFV-ART group having preterm delivery compared with 12% in the RAL-ART group. In addition, the proportion of HIV-infected infants was lower in the RAL-ART arm (1% versus 3%). These differences were not significant.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Glaxo/ViiV, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supplied study drugs. Dr. Mirochnick has received research funding from those companies.

SOURCE: Mark Mirochnick et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 39 LB.

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen that included the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL-ART) led to faster viral load (VL) reduction and a greater proportion of women with a VL of less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared with patients treated with an efavirenz-based ART (EFV-ART). There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to percentage of stillbirths, preterm delivery, or rates of HIV infection in the newborn.

“There are lots of advantages of these [integrase inhibitor] drugs, and we’d like to have pregnant women take advantage of them. The problem is, there’s no requirement of drug manufacturers to study the drugs in pregnancy. So these studies are put off until after the drug is licensed, and we’re playing catch-up,” Mark Mirochnick, MD, professor of pediatrics at Boston University, said in an interview. Dr. Mirochnick presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Another integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir, has a better resistance profile than that of raltegravir, but concerns over neural tube defects observed during a study in Botswana led both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to issue safety warnings for that drug. The current study did not raise concern, since it began at 20 weeks’ gestation, well after the period when neural tube defects might occur. “I think it just demonstrates that [integrase inhibitors] are safe in mid- to late-pregnancy,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

It remains to be seen whether a potential link to neural tube defects, if it is a real effect, is due to a specific drug or the mechanism of action of integrase inhibitors more generally. “It’s a question we don’t have an answer to. So you have to balance the potential benefits and potential risks, and that’s probably a decision best made by an individual woman and her care provider. Some women do very well on a particular regimen and they don’t want to change, and you run the risk when you change that you’ll get a viral rebound. What do you tell women who are on dolutegravir and are thinking about becoming pregnant? That’s a controversial question. There are risks with both courses,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

The study comprised 408 patients recruited from centers in Brazil, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, and the United States. The patients were between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation and had not previously received ART. They were randomized to RAL-ART or EFV-ART. About 12% of patients were Asian, 36% were black, 52% were Hispanic, and 1% were white.

Overall, 94% of patients on RAL-ART had a VL less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared to 84% of EFV-ART patients (P = .001). The effect appeared to be driven by patients who enrolled later in pregnancy: There was no significant difference in those enrolled in weeks 20-28, but suppression occurred in 93% of the RAL-ART group versus 71% of the EFV-ART group among those enrolled in weeks 29-37 (P = .04).

Tolerability was slightly better in the RAL-ART group, with 99% versus 97% of patients staying on their assigned therapy (P = .05). In both groups, 30% of women experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or higher, as did 25% of live-born infants in both groups.

A total of 92% of women in the RAL-ART group had a sustained VL response through delivery, compared with 64% in the EFV-ART group (P less than .001). The median time to achieving a VL less than 200 copies/mL was 8 days in the RAL-ART group and 15 days in the EFV-ART group (generalized log-rank test P less than .001).

There was one stillbirth in the EFV-ART arm and three in the RAL-ART arm, with 11% in the EFV-ART group having preterm delivery compared with 12% in the RAL-ART group. In addition, the proportion of HIV-infected infants was lower in the RAL-ART arm (1% versus 3%). These differences were not significant.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Glaxo/ViiV, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supplied study drugs. Dr. Mirochnick has received research funding from those companies.

SOURCE: Mark Mirochnick et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 39 LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

Survey of MS patients reveals numerous pregnancy-related concerns

DALLAS – When it comes to family planning and pregnancy-related decisions such as breastfeeding and medication management, patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) receive a wide variety of advice, guidance, and engagement from their health care providers, results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“We want our patients to feel comfortable when they come to us in their 20s or 30s and they get diagnosed, they’re scared, and it’s all new to them,” one of the study authors, Casey E. Engel said in an interview at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “We want them to know that family planning is something to consider and that they can proceed with having a family with our help and guidance.”

In an effort to collect patient-experience data around family planning, pregnancy, and breastfeeding post-MS diagnosis, Ms. Engel and senior author Myla D. Goldman, MD, mailed a survey to 1,000 women with confirmed MS diagnosis who had received care at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville. The researchers reported findings from 173 respondents, of whom 70% were receiving specialty care for MS. Most of the survey participants (137) did not become pregnant following their diagnosis, while 36 did.

Of the 137 respondents who did not become pregnant following diagnosis, 22 (16%) indicated that their decision was driven by MS-related concerns, including MS worsening with pregnancy (64%), ability to care for child secondary to MS (46%), lack of knowledge about options for pregnancy and MS (18%), passing MS onto child (18%), and stopping disease-modifying therapy (DMT) to attempt pregnancy (9%).

Of the 36 women who had a pregnancy following diagnosis, 20% reported postpartum depression or anxiety, higher than the national average of 10%-15%. In addition, 79% reported not being on DMT at the time of conception, 9% were on either glatiramer acetate injection or interferon beta-1a at time of conception, and 3% were on fingolimod (Gilenya) at time of conception. The majority reported receiving inconsistent advice about when to discontinue DMT before attempting pregnancy (a range from 0 to 6 months).

“It’s also noteworthy that 20% took a year to achieve pregnancy,” said Dr. Goldman, a neurologist who directs the university’s MS clinic. “If these women stop [their DMT] 6 months in advance and they take a year to achieve pregnancy, that’s 18 months without therapeutic coverage. That’s a concern to bring to light.”

Breastfeeding was reported in 71% of mothers in postdiagnosis pregnancy with a range between 1 week and 10 months, driven in part by variable guidelines regarding DMT reinitiation. In the meantime, respondents who did not breastfeed made this decision due to fear of relapse, glucocorticoids, or desire to reinitiate medication.

“Though our study was limited by low survey response, we hope that our work may highlight the difficulty our patients face and foster discussions within the MS community around these issues to improve the individual patient experience,” the researchers wrote in their poster.

Ms. Engel worked on the study while an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. The study was supported by the ziMS Foundation.

SOURCE: Engel CE et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Poster 307.

DALLAS – When it comes to family planning and pregnancy-related decisions such as breastfeeding and medication management, patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) receive a wide variety of advice, guidance, and engagement from their health care providers, results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“We want our patients to feel comfortable when they come to us in their 20s or 30s and they get diagnosed, they’re scared, and it’s all new to them,” one of the study authors, Casey E. Engel said in an interview at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “We want them to know that family planning is something to consider and that they can proceed with having a family with our help and guidance.”

In an effort to collect patient-experience data around family planning, pregnancy, and breastfeeding post-MS diagnosis, Ms. Engel and senior author Myla D. Goldman, MD, mailed a survey to 1,000 women with confirmed MS diagnosis who had received care at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville. The researchers reported findings from 173 respondents, of whom 70% were receiving specialty care for MS. Most of the survey participants (137) did not become pregnant following their diagnosis, while 36 did.

Of the 137 respondents who did not become pregnant following diagnosis, 22 (16%) indicated that their decision was driven by MS-related concerns, including MS worsening with pregnancy (64%), ability to care for child secondary to MS (46%), lack of knowledge about options for pregnancy and MS (18%), passing MS onto child (18%), and stopping disease-modifying therapy (DMT) to attempt pregnancy (9%).

Of the 36 women who had a pregnancy following diagnosis, 20% reported postpartum depression or anxiety, higher than the national average of 10%-15%. In addition, 79% reported not being on DMT at the time of conception, 9% were on either glatiramer acetate injection or interferon beta-1a at time of conception, and 3% were on fingolimod (Gilenya) at time of conception. The majority reported receiving inconsistent advice about when to discontinue DMT before attempting pregnancy (a range from 0 to 6 months).

“It’s also noteworthy that 20% took a year to achieve pregnancy,” said Dr. Goldman, a neurologist who directs the university’s MS clinic. “If these women stop [their DMT] 6 months in advance and they take a year to achieve pregnancy, that’s 18 months without therapeutic coverage. That’s a concern to bring to light.”

Breastfeeding was reported in 71% of mothers in postdiagnosis pregnancy with a range between 1 week and 10 months, driven in part by variable guidelines regarding DMT reinitiation. In the meantime, respondents who did not breastfeed made this decision due to fear of relapse, glucocorticoids, or desire to reinitiate medication.

“Though our study was limited by low survey response, we hope that our work may highlight the difficulty our patients face and foster discussions within the MS community around these issues to improve the individual patient experience,” the researchers wrote in their poster.

Ms. Engel worked on the study while an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. The study was supported by the ziMS Foundation.

SOURCE: Engel CE et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Poster 307.

DALLAS – When it comes to family planning and pregnancy-related decisions such as breastfeeding and medication management, patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) receive a wide variety of advice, guidance, and engagement from their health care providers, results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“We want our patients to feel comfortable when they come to us in their 20s or 30s and they get diagnosed, they’re scared, and it’s all new to them,” one of the study authors, Casey E. Engel said in an interview at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “We want them to know that family planning is something to consider and that they can proceed with having a family with our help and guidance.”

In an effort to collect patient-experience data around family planning, pregnancy, and breastfeeding post-MS diagnosis, Ms. Engel and senior author Myla D. Goldman, MD, mailed a survey to 1,000 women with confirmed MS diagnosis who had received care at the University of Virginia Medical Center in Charlottesville. The researchers reported findings from 173 respondents, of whom 70% were receiving specialty care for MS. Most of the survey participants (137) did not become pregnant following their diagnosis, while 36 did.

Of the 137 respondents who did not become pregnant following diagnosis, 22 (16%) indicated that their decision was driven by MS-related concerns, including MS worsening with pregnancy (64%), ability to care for child secondary to MS (46%), lack of knowledge about options for pregnancy and MS (18%), passing MS onto child (18%), and stopping disease-modifying therapy (DMT) to attempt pregnancy (9%).

Of the 36 women who had a pregnancy following diagnosis, 20% reported postpartum depression or anxiety, higher than the national average of 10%-15%. In addition, 79% reported not being on DMT at the time of conception, 9% were on either glatiramer acetate injection or interferon beta-1a at time of conception, and 3% were on fingolimod (Gilenya) at time of conception. The majority reported receiving inconsistent advice about when to discontinue DMT before attempting pregnancy (a range from 0 to 6 months).

“It’s also noteworthy that 20% took a year to achieve pregnancy,” said Dr. Goldman, a neurologist who directs the university’s MS clinic. “If these women stop [their DMT] 6 months in advance and they take a year to achieve pregnancy, that’s 18 months without therapeutic coverage. That’s a concern to bring to light.”

Breastfeeding was reported in 71% of mothers in postdiagnosis pregnancy with a range between 1 week and 10 months, driven in part by variable guidelines regarding DMT reinitiation. In the meantime, respondents who did not breastfeed made this decision due to fear of relapse, glucocorticoids, or desire to reinitiate medication.

“Though our study was limited by low survey response, we hope that our work may highlight the difficulty our patients face and foster discussions within the MS community around these issues to improve the individual patient experience,” the researchers wrote in their poster.

Ms. Engel worked on the study while an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. The study was supported by the ziMS Foundation.

SOURCE: Engel CE et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Poster 307.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Antenatal steroids for preterm birth is cost effective

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Tight intrapartum glucose control doesn’t improve neonatal outcomes

LAS VEGAS – There was no difference in first neonatal glucose level or glucose levels within the first 24 hours of life when women with gestational diabetes received strict, rather than liberalized, glucose management in labor.

In a study of 76 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), the mean first blood glucose level was 53 mg/dL for neonates born to the 38 mothers who received tight glucose control during labor; for those born to the 38 women who received liberalized control, mean first glucose level was 56 mg/dL (interquartile ranges, 22-85 mg/dL and 27-126 mg/dL, respectively; P = .56).

Secondary outcomes tracked in the study included the proportion of neonates whose glucose levels were low (defined as less than 40 mg/dL) at birth. This figure was identical in both groups, at 24%.

These findings ran counter to the hypothesis that Maureen Hamel, MD, and her colleagues at Brown University, Providence, R.I., had formulated – that neonates whose mothers had tight intrapartum glucose control would have lower rates of neonatal hypoglycemia than those born to women with liberalized intrapartum control.

Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, numerically more infants in the tight-control group required any intervention for hypoglycemia (45% vs. 32%; P = .35) or intravenous intervention for hypoglycemia (11% vs 0%; P = .35). Neonatal ICU admission was required for 13% of the tight-control neonates versus 3% of the liberalized-control group (P = .20).

“A protocol aimed at tight maternal glucose management in labor, compared to liberalized management, for women with GDM, did not result in a lower rate of neonatal hypoglycemia and was associated with mean neonatal glucose closer to hypoglycemia [40 mg/dL] in the first 24 hours of life,” said Dr. Hamel, discussing the findings of her award-winning abstract at the meeting presented by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Women were included if they were at least 18 years old with a singleton pregnancy and a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Participants received care through a specialized program for pregnant women with diabetes; they were considered to have GDM if they had at least two abnormal values from a 100-g, 3-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) or had a blood glucose reading of at least 200 mg/dL from a 1-hour 50-g GTT. About two-thirds of women required medical management of GDM; about 80% received labor induction at 39 weeks’ gestation.

At 36 weeks’ gestation, participants were block-randomized 1:1 to receive tight or liberalized intrapartum blood glucose control, with allocation unknown to both providers and patients until participants were admitted for delivery. Neonatal providers were blinded as to allocation throughout the admission. “In the tight glucose control group, point-of-care glucose was assessed hourly,” said Dr. Hamel. “Goal glucose levels were 70-100 [mg/dL], and treatment was initiated for a single maternal glucose greater than 100 and less than 60 [mg/dL].”

Those in the liberalized group had blood sugar checked every 4 hours in the absence of symptoms, with a goal blood glucose range of 70-120 mg/dL and treatment initiated for blood glucose over 120 or less than 60 mg/dL.

The increase in older women giving birth partly underlies the increase in GDM, said Dr. Hamel. By 35 years of age, about 15% of women will develop GDM, compared with under 6% for women giving birth between 20 and 24 years of age.

Neonatal hypoglycemia, with associated risks for neonatal ICU admission, seizures, and neurologic injury, is more common in women with GDM, said Dr. Hamel, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow.

There’s wide institutional and geographic variation in intrapartum maternal glucose management, said Dr. Hamel. Even within her own institution, blood sugar might be checked just once in labor, every 2 hours, or every hour, and the threshold for treatment might be set at a maternal blood glucose level over 100, 120, or even 200 mg/dL.

The study benefited from the fact that there was standardized antepartum GDM management in place and that 100% of outcome data were available. Also, the a priori sample size to detect significant between-group differences was obtained, and neonatal providers were blinded as to maternal glucose control strategy. Replication of the study should be both easy and feasible, said Dr. Hamel.

However, only very short-term outcomes were tracked, and the study was not powered to detect differences in such less-frequent neonatal outcomes as neonatal ICU admission.

“There is no benefit to tight maternal glucose control in labor among women with GDM,” concluded Dr. Hamel. “Our findings support glucose assessment every 4 hours, with intervention for blood glucose levels less than 60 or higher than 120 [mg/dL].”

Dr. Hamel reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamel M et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S36, Abstract 44.

LAS VEGAS – There was no difference in first neonatal glucose level or glucose levels within the first 24 hours of life when women with gestational diabetes received strict, rather than liberalized, glucose management in labor.

In a study of 76 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), the mean first blood glucose level was 53 mg/dL for neonates born to the 38 mothers who received tight glucose control during labor; for those born to the 38 women who received liberalized control, mean first glucose level was 56 mg/dL (interquartile ranges, 22-85 mg/dL and 27-126 mg/dL, respectively; P = .56).

Secondary outcomes tracked in the study included the proportion of neonates whose glucose levels were low (defined as less than 40 mg/dL) at birth. This figure was identical in both groups, at 24%.

These findings ran counter to the hypothesis that Maureen Hamel, MD, and her colleagues at Brown University, Providence, R.I., had formulated – that neonates whose mothers had tight intrapartum glucose control would have lower rates of neonatal hypoglycemia than those born to women with liberalized intrapartum control.

Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, numerically more infants in the tight-control group required any intervention for hypoglycemia (45% vs. 32%; P = .35) or intravenous intervention for hypoglycemia (11% vs 0%; P = .35). Neonatal ICU admission was required for 13% of the tight-control neonates versus 3% of the liberalized-control group (P = .20).

“A protocol aimed at tight maternal glucose management in labor, compared to liberalized management, for women with GDM, did not result in a lower rate of neonatal hypoglycemia and was associated with mean neonatal glucose closer to hypoglycemia [40 mg/dL] in the first 24 hours of life,” said Dr. Hamel, discussing the findings of her award-winning abstract at the meeting presented by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Women were included if they were at least 18 years old with a singleton pregnancy and a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Participants received care through a specialized program for pregnant women with diabetes; they were considered to have GDM if they had at least two abnormal values from a 100-g, 3-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) or had a blood glucose reading of at least 200 mg/dL from a 1-hour 50-g GTT. About two-thirds of women required medical management of GDM; about 80% received labor induction at 39 weeks’ gestation.

At 36 weeks’ gestation, participants were block-randomized 1:1 to receive tight or liberalized intrapartum blood glucose control, with allocation unknown to both providers and patients until participants were admitted for delivery. Neonatal providers were blinded as to allocation throughout the admission. “In the tight glucose control group, point-of-care glucose was assessed hourly,” said Dr. Hamel. “Goal glucose levels were 70-100 [mg/dL], and treatment was initiated for a single maternal glucose greater than 100 and less than 60 [mg/dL].”

Those in the liberalized group had blood sugar checked every 4 hours in the absence of symptoms, with a goal blood glucose range of 70-120 mg/dL and treatment initiated for blood glucose over 120 or less than 60 mg/dL.

The increase in older women giving birth partly underlies the increase in GDM, said Dr. Hamel. By 35 years of age, about 15% of women will develop GDM, compared with under 6% for women giving birth between 20 and 24 years of age.

Neonatal hypoglycemia, with associated risks for neonatal ICU admission, seizures, and neurologic injury, is more common in women with GDM, said Dr. Hamel, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow.

There’s wide institutional and geographic variation in intrapartum maternal glucose management, said Dr. Hamel. Even within her own institution, blood sugar might be checked just once in labor, every 2 hours, or every hour, and the threshold for treatment might be set at a maternal blood glucose level over 100, 120, or even 200 mg/dL.

The study benefited from the fact that there was standardized antepartum GDM management in place and that 100% of outcome data were available. Also, the a priori sample size to detect significant between-group differences was obtained, and neonatal providers were blinded as to maternal glucose control strategy. Replication of the study should be both easy and feasible, said Dr. Hamel.

However, only very short-term outcomes were tracked, and the study was not powered to detect differences in such less-frequent neonatal outcomes as neonatal ICU admission.

“There is no benefit to tight maternal glucose control in labor among women with GDM,” concluded Dr. Hamel. “Our findings support glucose assessment every 4 hours, with intervention for blood glucose levels less than 60 or higher than 120 [mg/dL].”

Dr. Hamel reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamel M et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S36, Abstract 44.

LAS VEGAS – There was no difference in first neonatal glucose level or glucose levels within the first 24 hours of life when women with gestational diabetes received strict, rather than liberalized, glucose management in labor.

In a study of 76 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), the mean first blood glucose level was 53 mg/dL for neonates born to the 38 mothers who received tight glucose control during labor; for those born to the 38 women who received liberalized control, mean first glucose level was 56 mg/dL (interquartile ranges, 22-85 mg/dL and 27-126 mg/dL, respectively; P = .56).

Secondary outcomes tracked in the study included the proportion of neonates whose glucose levels were low (defined as less than 40 mg/dL) at birth. This figure was identical in both groups, at 24%.

These findings ran counter to the hypothesis that Maureen Hamel, MD, and her colleagues at Brown University, Providence, R.I., had formulated – that neonates whose mothers had tight intrapartum glucose control would have lower rates of neonatal hypoglycemia than those born to women with liberalized intrapartum control.

Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, numerically more infants in the tight-control group required any intervention for hypoglycemia (45% vs. 32%; P = .35) or intravenous intervention for hypoglycemia (11% vs 0%; P = .35). Neonatal ICU admission was required for 13% of the tight-control neonates versus 3% of the liberalized-control group (P = .20).

“A protocol aimed at tight maternal glucose management in labor, compared to liberalized management, for women with GDM, did not result in a lower rate of neonatal hypoglycemia and was associated with mean neonatal glucose closer to hypoglycemia [40 mg/dL] in the first 24 hours of life,” said Dr. Hamel, discussing the findings of her award-winning abstract at the meeting presented by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Women were included if they were at least 18 years old with a singleton pregnancy and a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Participants received care through a specialized program for pregnant women with diabetes; they were considered to have GDM if they had at least two abnormal values from a 100-g, 3-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) or had a blood glucose reading of at least 200 mg/dL from a 1-hour 50-g GTT. About two-thirds of women required medical management of GDM; about 80% received labor induction at 39 weeks’ gestation.