User login

Insulin may be toxic to the placenta in early pregnancy

, according to findings from an experimental in vitro study published in Fertility and Sterility.

“Collectively these results demonstrate that insulin itself may be directly toxic to the early human placenta but that metformin can prevent these deleterious effects,” wrote Mario Vega, MD, of Columbia University Fertility Center, New York, and his colleagues. “If confirmed in animal and human studies, this would indicate that screening and treatment for insulin resistance should focus on hyperinsulinemia.”

Dr. Vega and his colleagues cultivated trophoblast cells from three healthy women scheduled for manual vacuum aspiration during the first trimester of pregnancy to study the effects of insulin exposure alone, while trophoblast cells were cultured from a different set of women for the insulin and metformin follow-up experiments. The researchers tested each experiment against a control group of cultivated lung fibroblast cells. Insulin was measured in doses of 0.2 nmol, 1 nmol, and 5 nmol, while metformin was measured at 10 micromol. The primary outcome measures examined were gamma-H2AX for DNA damage, cell proliferation assay for cell survival, and cleaved caspase-3 for apoptosis.

Within 48 hours, the cultures showed DNA damage and induction of apoptosis when exposed to 1 nmol of insulin, but researchers said pretreatment with metformin prevented these effects. Exposing cells to metformin after insulin reduced but did not eliminate the effects of insulin.

The researchers noted the study is limited because the effects of insulin and metformin have not been examined in vivo, and it is not known at what level insulin causes damage. In addition, they suggested downregulation of genes in trophoblasts caused by insulin could cause apoptosis and DNA damage to trophoblast cells.

“Although studies performed on kidney and colon cells suggest that one possible mechanism of action for insulin-mediated genotoxicity is through AKT activation of mitochondria and subsequent reactive oxygen species production, the exact mechanism is poorly understood,” Dr. Vega and colleagues said. “Future studies will be necessary to determine variability among subjects, as well as mechanisms of action through which insulin exerts its cytotoxicity and genotoxicity.”

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Human Placenta Project. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Vega M et al. Fertil Steril. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.032.

, according to findings from an experimental in vitro study published in Fertility and Sterility.

“Collectively these results demonstrate that insulin itself may be directly toxic to the early human placenta but that metformin can prevent these deleterious effects,” wrote Mario Vega, MD, of Columbia University Fertility Center, New York, and his colleagues. “If confirmed in animal and human studies, this would indicate that screening and treatment for insulin resistance should focus on hyperinsulinemia.”

Dr. Vega and his colleagues cultivated trophoblast cells from three healthy women scheduled for manual vacuum aspiration during the first trimester of pregnancy to study the effects of insulin exposure alone, while trophoblast cells were cultured from a different set of women for the insulin and metformin follow-up experiments. The researchers tested each experiment against a control group of cultivated lung fibroblast cells. Insulin was measured in doses of 0.2 nmol, 1 nmol, and 5 nmol, while metformin was measured at 10 micromol. The primary outcome measures examined were gamma-H2AX for DNA damage, cell proliferation assay for cell survival, and cleaved caspase-3 for apoptosis.

Within 48 hours, the cultures showed DNA damage and induction of apoptosis when exposed to 1 nmol of insulin, but researchers said pretreatment with metformin prevented these effects. Exposing cells to metformin after insulin reduced but did not eliminate the effects of insulin.

The researchers noted the study is limited because the effects of insulin and metformin have not been examined in vivo, and it is not known at what level insulin causes damage. In addition, they suggested downregulation of genes in trophoblasts caused by insulin could cause apoptosis and DNA damage to trophoblast cells.

“Although studies performed on kidney and colon cells suggest that one possible mechanism of action for insulin-mediated genotoxicity is through AKT activation of mitochondria and subsequent reactive oxygen species production, the exact mechanism is poorly understood,” Dr. Vega and colleagues said. “Future studies will be necessary to determine variability among subjects, as well as mechanisms of action through which insulin exerts its cytotoxicity and genotoxicity.”

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Human Placenta Project. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Vega M et al. Fertil Steril. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.032.

, according to findings from an experimental in vitro study published in Fertility and Sterility.

“Collectively these results demonstrate that insulin itself may be directly toxic to the early human placenta but that metformin can prevent these deleterious effects,” wrote Mario Vega, MD, of Columbia University Fertility Center, New York, and his colleagues. “If confirmed in animal and human studies, this would indicate that screening and treatment for insulin resistance should focus on hyperinsulinemia.”

Dr. Vega and his colleagues cultivated trophoblast cells from three healthy women scheduled for manual vacuum aspiration during the first trimester of pregnancy to study the effects of insulin exposure alone, while trophoblast cells were cultured from a different set of women for the insulin and metformin follow-up experiments. The researchers tested each experiment against a control group of cultivated lung fibroblast cells. Insulin was measured in doses of 0.2 nmol, 1 nmol, and 5 nmol, while metformin was measured at 10 micromol. The primary outcome measures examined were gamma-H2AX for DNA damage, cell proliferation assay for cell survival, and cleaved caspase-3 for apoptosis.

Within 48 hours, the cultures showed DNA damage and induction of apoptosis when exposed to 1 nmol of insulin, but researchers said pretreatment with metformin prevented these effects. Exposing cells to metformin after insulin reduced but did not eliminate the effects of insulin.

The researchers noted the study is limited because the effects of insulin and metformin have not been examined in vivo, and it is not known at what level insulin causes damage. In addition, they suggested downregulation of genes in trophoblasts caused by insulin could cause apoptosis and DNA damage to trophoblast cells.

“Although studies performed on kidney and colon cells suggest that one possible mechanism of action for insulin-mediated genotoxicity is through AKT activation of mitochondria and subsequent reactive oxygen species production, the exact mechanism is poorly understood,” Dr. Vega and colleagues said. “Future studies will be necessary to determine variability among subjects, as well as mechanisms of action through which insulin exerts its cytotoxicity and genotoxicity.”

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Human Placenta Project. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Vega M et al. Fertil Steril. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.032.

FROM FERTILITY & STERILITY

Key clinical point: Trophoblasts cultured during the first trimester of pregnancy exposed to insulin were more likely to have increased apoptosis, DNA damage, and decreased cell survival, while pretreatment with metformin prior to exposure with insulin prevented these effects.

Major finding: DNA damage and rate of apoptosis increased in trophoblast cells exposed to 1 nmol of insulin, and cell survival decreased, compared with primary lung fibroblast cells; treating the cells with metformin prior to exposure with insulin resulted in prevention of these effects.

Study details: An experimental in vitro study of first trimester trophoblast cells exposed to insulin and metformin.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Human Placenta Project. The authors reported they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Vega M et al. Fertil Steril. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.032.

Stopping TNF inhibitors before 20 weeks’ gestation not linked to worsening RA, JIA

In pregnant women with arthritis, discontinuing tumor necrosis factor inhibitors prior to gestational week 20 seems feasible without an increased risk of disease worsening, particularly in those with well-controlled disease, according to authors of a recent analysis of a prospective cohort study.

Stopping tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) treatment at that point in the second trimester was not linked to any clinically important worsening of patient-reported outcomes later in pregnancy for women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), the researchers said.

However, continuing a TNFi past gestational week 20 may also be warranted for some patients, according to the researchers, led by Frauke Förger, MD, of the University of Bern (Switzerland).

“In case of active disease, the continuation of TNF inhibitors beyond gestational week 20 seems reasonable from the standpoint of improved disease activity in the third trimester, which may in turn lead to improved pregnancy outcomes,” Dr. Förger and her coinvestigators wrote in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

These findings stand in contrast to those of another recent study, in which stopping a TNF inhibitor after a positive pregnancy test was linked to disease flares in women with RA, according to the authors.

“The timing of drug discontinuation during pregnancy may be of importance,” they said in their report.

Beyond these studies, there are very limited data on the effects of discontinuing TNF inhibitors in pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis, and “a lack of any data” in pregnant women with JIA, they said.

The current investigation by Dr. Förger and her colleagues included 490 pregnant women in the United States or Canada who were enrolled in the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project, a prospective cohort study. Of those women, 397 had RA and 93 had JIA.

About one-quarter of the women (122, or 24.9%) discontinued TNF inhibitor therapy prior to gestational week 20, while 41% continued on TNF inhibitors beyond that point, and 34.1% did not use a TNF inhibitor in pregnancy.

For those women who discontinued TNF inhibitors before gestational week 20, scores on the Patient Activity Scale (PAS) were stable over time, Dr. Förger and her colleagues reported.

Women who continued TNF inhibitor treatment past gestational week 20 had improved PAS scores in the third trimester, according to results of a univariate analysis (P = .02). However, the improvement appeared to be attenuated after adjustment for factors including race, smoking, use of prednisone or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and gestational age, the investigators said.

They were unable to analyze the effects of ongoing TNFi treatment or discontinuation on patients with JIA separately because of the limited number of such patients in each group.

Another limitation of the study is that a high proportion of women – nearly three-quarters – had low disease activity at the start of pregnancy, according to the investigators, who said that group of women might expect some degree of improvement in the third trimester with or without TNF inhibitor discontinuation.

“In this context, the ameliorating effect of pregnancy on RA and JIA, which is most pronounced in the third trimester, may play a role,” they explained.

A certain proportion of women choose to discontinue certain arthritis treatments during pregnancy because of concerns that the medication may lead to fetal harm, but that may be changing, the investigators noted in their report.

“In recent years, more patients requiring treatment have been continuing on effective TNF inhibitors beyond conception as the available data on the safety of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy has increased,” they wrote.

Dr. Förger and her coauthors reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. Financial support for the OTIS Collaborative Research Group comes from industry sources including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Hoffman La Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, and UCB, among others.

SOURCE: Förger F et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/art.40821

In pregnant women with arthritis, discontinuing tumor necrosis factor inhibitors prior to gestational week 20 seems feasible without an increased risk of disease worsening, particularly in those with well-controlled disease, according to authors of a recent analysis of a prospective cohort study.

Stopping tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) treatment at that point in the second trimester was not linked to any clinically important worsening of patient-reported outcomes later in pregnancy for women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), the researchers said.

However, continuing a TNFi past gestational week 20 may also be warranted for some patients, according to the researchers, led by Frauke Förger, MD, of the University of Bern (Switzerland).

“In case of active disease, the continuation of TNF inhibitors beyond gestational week 20 seems reasonable from the standpoint of improved disease activity in the third trimester, which may in turn lead to improved pregnancy outcomes,” Dr. Förger and her coinvestigators wrote in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

These findings stand in contrast to those of another recent study, in which stopping a TNF inhibitor after a positive pregnancy test was linked to disease flares in women with RA, according to the authors.

“The timing of drug discontinuation during pregnancy may be of importance,” they said in their report.

Beyond these studies, there are very limited data on the effects of discontinuing TNF inhibitors in pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis, and “a lack of any data” in pregnant women with JIA, they said.

The current investigation by Dr. Förger and her colleagues included 490 pregnant women in the United States or Canada who were enrolled in the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project, a prospective cohort study. Of those women, 397 had RA and 93 had JIA.

About one-quarter of the women (122, or 24.9%) discontinued TNF inhibitor therapy prior to gestational week 20, while 41% continued on TNF inhibitors beyond that point, and 34.1% did not use a TNF inhibitor in pregnancy.

For those women who discontinued TNF inhibitors before gestational week 20, scores on the Patient Activity Scale (PAS) were stable over time, Dr. Förger and her colleagues reported.

Women who continued TNF inhibitor treatment past gestational week 20 had improved PAS scores in the third trimester, according to results of a univariate analysis (P = .02). However, the improvement appeared to be attenuated after adjustment for factors including race, smoking, use of prednisone or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and gestational age, the investigators said.

They were unable to analyze the effects of ongoing TNFi treatment or discontinuation on patients with JIA separately because of the limited number of such patients in each group.

Another limitation of the study is that a high proportion of women – nearly three-quarters – had low disease activity at the start of pregnancy, according to the investigators, who said that group of women might expect some degree of improvement in the third trimester with or without TNF inhibitor discontinuation.

“In this context, the ameliorating effect of pregnancy on RA and JIA, which is most pronounced in the third trimester, may play a role,” they explained.

A certain proportion of women choose to discontinue certain arthritis treatments during pregnancy because of concerns that the medication may lead to fetal harm, but that may be changing, the investigators noted in their report.

“In recent years, more patients requiring treatment have been continuing on effective TNF inhibitors beyond conception as the available data on the safety of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy has increased,” they wrote.

Dr. Förger and her coauthors reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. Financial support for the OTIS Collaborative Research Group comes from industry sources including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Hoffman La Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, and UCB, among others.

SOURCE: Förger F et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/art.40821

In pregnant women with arthritis, discontinuing tumor necrosis factor inhibitors prior to gestational week 20 seems feasible without an increased risk of disease worsening, particularly in those with well-controlled disease, according to authors of a recent analysis of a prospective cohort study.

Stopping tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) treatment at that point in the second trimester was not linked to any clinically important worsening of patient-reported outcomes later in pregnancy for women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), the researchers said.

However, continuing a TNFi past gestational week 20 may also be warranted for some patients, according to the researchers, led by Frauke Förger, MD, of the University of Bern (Switzerland).

“In case of active disease, the continuation of TNF inhibitors beyond gestational week 20 seems reasonable from the standpoint of improved disease activity in the third trimester, which may in turn lead to improved pregnancy outcomes,” Dr. Förger and her coinvestigators wrote in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

These findings stand in contrast to those of another recent study, in which stopping a TNF inhibitor after a positive pregnancy test was linked to disease flares in women with RA, according to the authors.

“The timing of drug discontinuation during pregnancy may be of importance,” they said in their report.

Beyond these studies, there are very limited data on the effects of discontinuing TNF inhibitors in pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis, and “a lack of any data” in pregnant women with JIA, they said.

The current investigation by Dr. Förger and her colleagues included 490 pregnant women in the United States or Canada who were enrolled in the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project, a prospective cohort study. Of those women, 397 had RA and 93 had JIA.

About one-quarter of the women (122, or 24.9%) discontinued TNF inhibitor therapy prior to gestational week 20, while 41% continued on TNF inhibitors beyond that point, and 34.1% did not use a TNF inhibitor in pregnancy.

For those women who discontinued TNF inhibitors before gestational week 20, scores on the Patient Activity Scale (PAS) were stable over time, Dr. Förger and her colleagues reported.

Women who continued TNF inhibitor treatment past gestational week 20 had improved PAS scores in the third trimester, according to results of a univariate analysis (P = .02). However, the improvement appeared to be attenuated after adjustment for factors including race, smoking, use of prednisone or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and gestational age, the investigators said.

They were unable to analyze the effects of ongoing TNFi treatment or discontinuation on patients with JIA separately because of the limited number of such patients in each group.

Another limitation of the study is that a high proportion of women – nearly three-quarters – had low disease activity at the start of pregnancy, according to the investigators, who said that group of women might expect some degree of improvement in the third trimester with or without TNF inhibitor discontinuation.

“In this context, the ameliorating effect of pregnancy on RA and JIA, which is most pronounced in the third trimester, may play a role,” they explained.

A certain proportion of women choose to discontinue certain arthritis treatments during pregnancy because of concerns that the medication may lead to fetal harm, but that may be changing, the investigators noted in their report.

“In recent years, more patients requiring treatment have been continuing on effective TNF inhibitors beyond conception as the available data on the safety of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy has increased,” they wrote.

Dr. Förger and her coauthors reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. Financial support for the OTIS Collaborative Research Group comes from industry sources including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Hoffman La Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, and UCB, among others.

SOURCE: Förger F et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/art.40821

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: In contrast to a previous report,

Major finding: Patient Activity Scale (PAS) scores were stable over time in women who discontinued TNF inhibitors before gestational week 20. Those who continued past week 20 had improved PAS scores in the third trimester (univariate analysis; P = .02).

Study details: Analysis including 490 pregnant women in the United States or Canada who enrolled in the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project, a prospective cohort study.

Disclosures: Dr. Förger and her coauthors reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. Financial support for the OTIS Collaborative Research Group comes from industry sources including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Hoffman La Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, and UCB, among others.

Source: Förger F et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/art.40821.

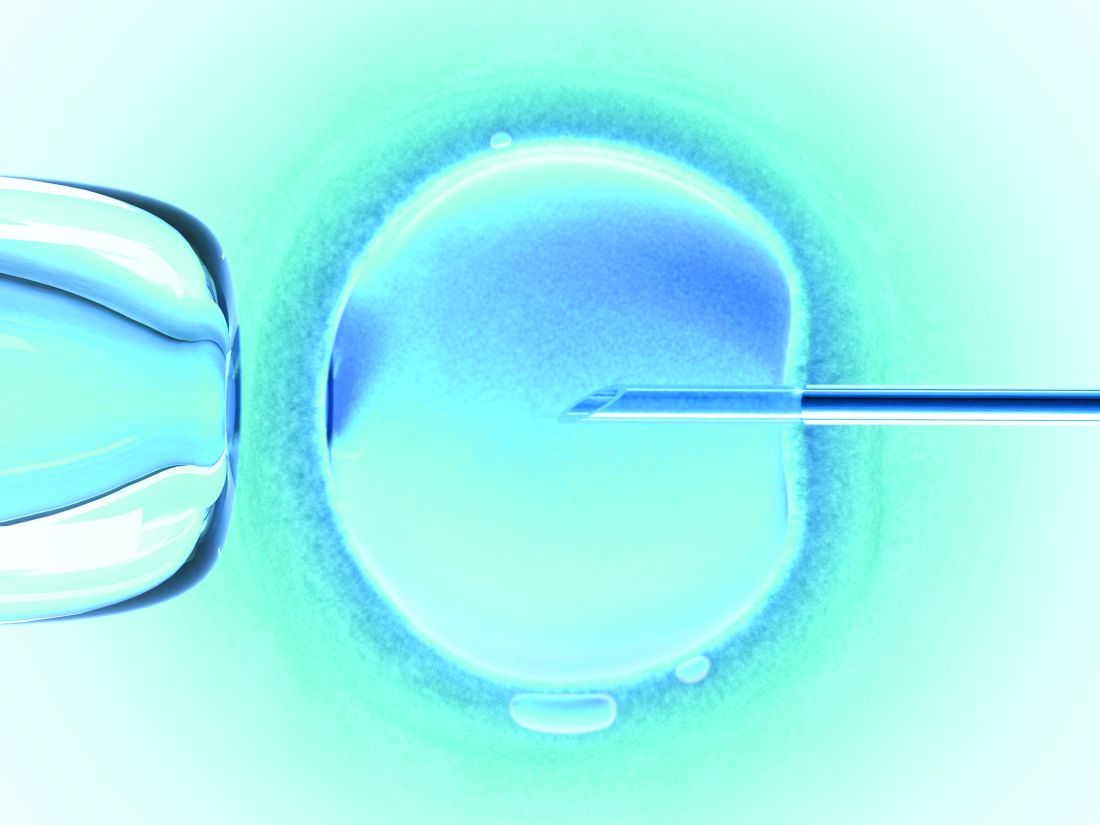

Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

Women with rheumatoid arthritis who undergo assisted reproduction treatment have a decreased likelihood of live births versus women without rheumatoid arthritis, according to authors of a recent Denmark-wide cohort study.

The problem might be caused by an impaired chance of embryo implantation, authors of the study reported in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Corticosteroids prescribed before embryo transfer might have improved the likelihood of live birth in these women with rheumatoid arthritis, according to the investigators, led by Professor Bente Mertz Nørgård of the center for clinical epidemiology at the Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

However, findings with regard to that potential effect of corticosteroids were “not unambiguous,” said Prof. Nørgård and her coauthors said in their report.

The cohort study, based on Danish registry data from 1994-2017, included 1,149 embryo transfers in women and rheumatoid arthritis with 198,941 embryo transfers in women without rheumatoid arthritis.

Live births per embryo transfer were less likely in women with rheumatoid arthritis versus those they were in women with no rheumatoid arthritis, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.92), according to investigators.

Chances of biochemical and clinical pregnancies were also lower in women with rheumatoid arthritis, with odds ratios of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.68-0.95) and 0.82 (95% CI, 0.59-1.15), respectively, the investigators found in an analysis of secondary outcomes in the study.

Corticosteroids prescribed before embryo transfer increased odds of live birth, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.32 (95% CI, 0.85-2.05), though the underlying reason why corticosteroids were prescribed could not be established in this data set, investigators cautioned.

“The impact of corticosteroid prior to embryo transfer, found in our study, could be due to a suppression of ‘abnormalities in the immune system’ in women with RA, but we have to underline that this is speculative,” Prof. Nørgård and her colleagues said in a discussion of their results.

Future investigations are needed to clarify the role of corticosteroids in women with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing assisted reproduction treatment, they added.

Support for the study came from the Research Foundation of the Region of Southern Denmark and the Free Research Foundation at Odense University Hospital. Dr. Nørgård and her coauthors said they had no competing interests related to the research.

SOURCE: Nørgård BM et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jan 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214619.

Women with rheumatoid arthritis who undergo assisted reproduction treatment have a decreased likelihood of live births versus women without rheumatoid arthritis, according to authors of a recent Denmark-wide cohort study.

The problem might be caused by an impaired chance of embryo implantation, authors of the study reported in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Corticosteroids prescribed before embryo transfer might have improved the likelihood of live birth in these women with rheumatoid arthritis, according to the investigators, led by Professor Bente Mertz Nørgård of the center for clinical epidemiology at the Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

However, findings with regard to that potential effect of corticosteroids were “not unambiguous,” said Prof. Nørgård and her coauthors said in their report.

The cohort study, based on Danish registry data from 1994-2017, included 1,149 embryo transfers in women and rheumatoid arthritis with 198,941 embryo transfers in women without rheumatoid arthritis.

Live births per embryo transfer were less likely in women with rheumatoid arthritis versus those they were in women with no rheumatoid arthritis, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.92), according to investigators.

Chances of biochemical and clinical pregnancies were also lower in women with rheumatoid arthritis, with odds ratios of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.68-0.95) and 0.82 (95% CI, 0.59-1.15), respectively, the investigators found in an analysis of secondary outcomes in the study.

Corticosteroids prescribed before embryo transfer increased odds of live birth, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.32 (95% CI, 0.85-2.05), though the underlying reason why corticosteroids were prescribed could not be established in this data set, investigators cautioned.

“The impact of corticosteroid prior to embryo transfer, found in our study, could be due to a suppression of ‘abnormalities in the immune system’ in women with RA, but we have to underline that this is speculative,” Prof. Nørgård and her colleagues said in a discussion of their results.

Future investigations are needed to clarify the role of corticosteroids in women with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing assisted reproduction treatment, they added.

Support for the study came from the Research Foundation of the Region of Southern Denmark and the Free Research Foundation at Odense University Hospital. Dr. Nørgård and her coauthors said they had no competing interests related to the research.

SOURCE: Nørgård BM et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jan 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214619.

Women with rheumatoid arthritis who undergo assisted reproduction treatment have a decreased likelihood of live births versus women without rheumatoid arthritis, according to authors of a recent Denmark-wide cohort study.

The problem might be caused by an impaired chance of embryo implantation, authors of the study reported in the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Corticosteroids prescribed before embryo transfer might have improved the likelihood of live birth in these women with rheumatoid arthritis, according to the investigators, led by Professor Bente Mertz Nørgård of the center for clinical epidemiology at the Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

However, findings with regard to that potential effect of corticosteroids were “not unambiguous,” said Prof. Nørgård and her coauthors said in their report.

The cohort study, based on Danish registry data from 1994-2017, included 1,149 embryo transfers in women and rheumatoid arthritis with 198,941 embryo transfers in women without rheumatoid arthritis.

Live births per embryo transfer were less likely in women with rheumatoid arthritis versus those they were in women with no rheumatoid arthritis, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.92), according to investigators.

Chances of biochemical and clinical pregnancies were also lower in women with rheumatoid arthritis, with odds ratios of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.68-0.95) and 0.82 (95% CI, 0.59-1.15), respectively, the investigators found in an analysis of secondary outcomes in the study.

Corticosteroids prescribed before embryo transfer increased odds of live birth, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.32 (95% CI, 0.85-2.05), though the underlying reason why corticosteroids were prescribed could not be established in this data set, investigators cautioned.

“The impact of corticosteroid prior to embryo transfer, found in our study, could be due to a suppression of ‘abnormalities in the immune system’ in women with RA, but we have to underline that this is speculative,” Prof. Nørgård and her colleagues said in a discussion of their results.

Future investigations are needed to clarify the role of corticosteroids in women with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing assisted reproduction treatment, they added.

Support for the study came from the Research Foundation of the Region of Southern Denmark and the Free Research Foundation at Odense University Hospital. Dr. Nørgård and her coauthors said they had no competing interests related to the research.

SOURCE: Nørgård BM et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jan 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214619.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Key clinical point: Women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who undergo assisted reproduction treatment have decreased chances of live births, compared with women without RA.

Major finding: The odds ratio for live births per embryo transfer in women with RA, as compared to women without RA, was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.92).

Study details: A nationwide cohort study including 1,149 embryo transfers in women with rheumatoid arthritis and 198,941 without rheumatoid arthritis

Disclosures: Study authors had no disclosures. Support for the study came from the Research Foundation of the Region of Southern Denmark and the Free Research Foundation at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

Source: Nørgård BM et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jan 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214619.

Management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

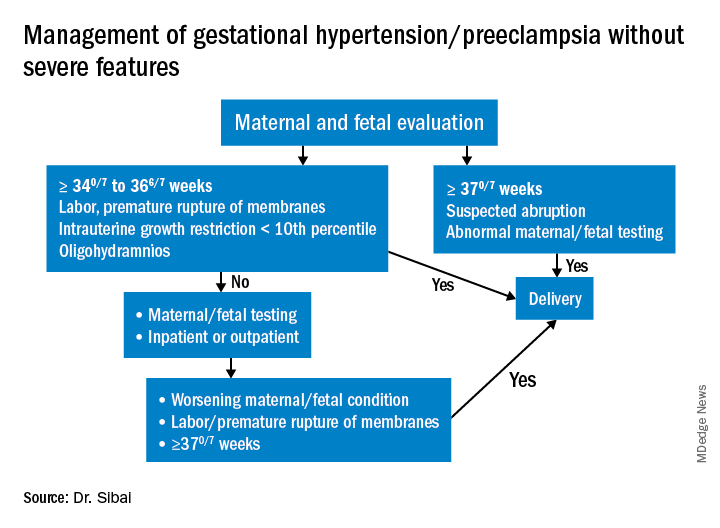

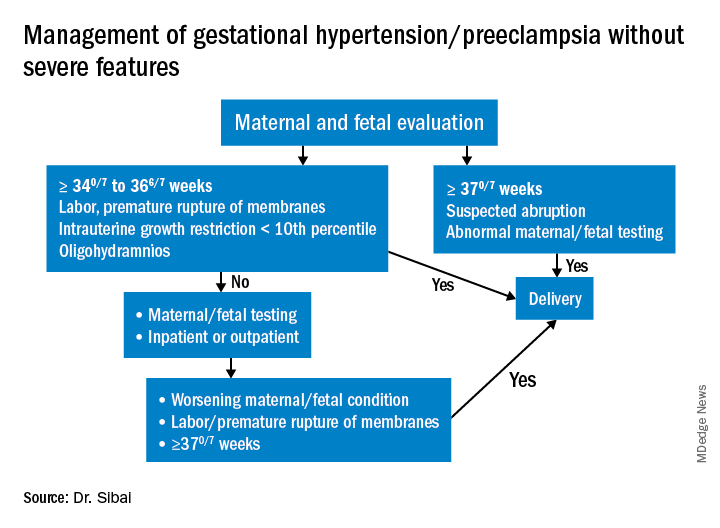

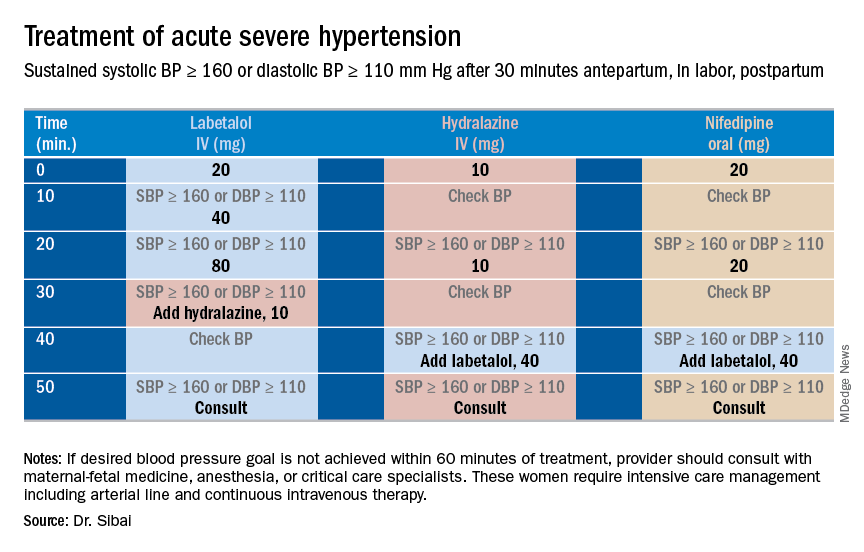

In the last installment of the Master Class, I addressed the importance of clarity in the classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and proposed several key diagnostic definitions. Here, I address the management of “mild” gestational hypertension (GHTN) and preeclampsia without severe features, which I believe should be managed similarly. I also address the management of preeclampsia with severe features, and I share an algorithm that I have developed and fine-tuned over the years to control acute severe hypertension with the use of intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, or oral nifedipine.

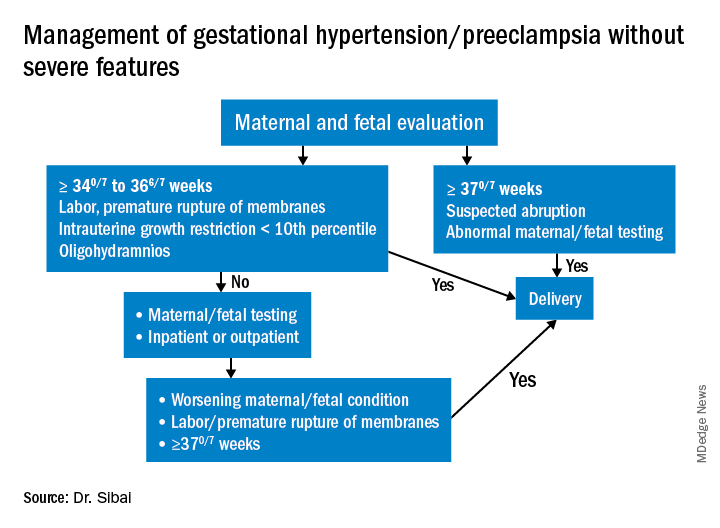

Management of “mild” gestational hypertension/Preeclampsia without severe features

Mild gestational hypertension in and of itself has little effect on maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality when it develops at or beyond 37 weeks’ gestation. However, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with preterm GHTN will subsequently develop preeclampsia or progress to severe GHTN. In addition, these pregnancies may result in fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.

Antihypertensive drugs should not be used during ambulatory management of women with GHTN. Patients who receive antihypertensive therapy, including those diagnosed with severe GHTN, should be hospitalized and initially treated as having preeclampsia with or without severe features. Subsequent management will depend on initial response to therapy, blood pressure values after treatment, gestational age, and laboratory findings.

Preeclampsia without severe features is usually managed as in those with GHTN. (See related figure.)

Close surveillance is warranted, as either type may progress to fulminant disease. Maternal surveillance should include blood pressure measurements twice per week, and CBC, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine measurements once every week. Patients also should be instructed to immediately report any of these symptoms: Persistent severe headaches; right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting; scotomata, blurred vision, photophobia, or double vision; shortness of breath or orthopnea; altered mental changes; decreased fetal movement; rupture of membranes; vaginal bleeding; or regular uterine contractions.

Fetal evaluation for patients with GHTN/preeclampsia includes ultrasound at the time of diagnosis for evaluation of fetal growth and amniotic fluid value (deepest vertical pocket, or DVP) as well as fetal movement count and non-stress testing (NST). Subsequently, NST and DVP need to be checked twice per week. A decision for delivery will depend on gestational age, fetal status, and development of severe disease.

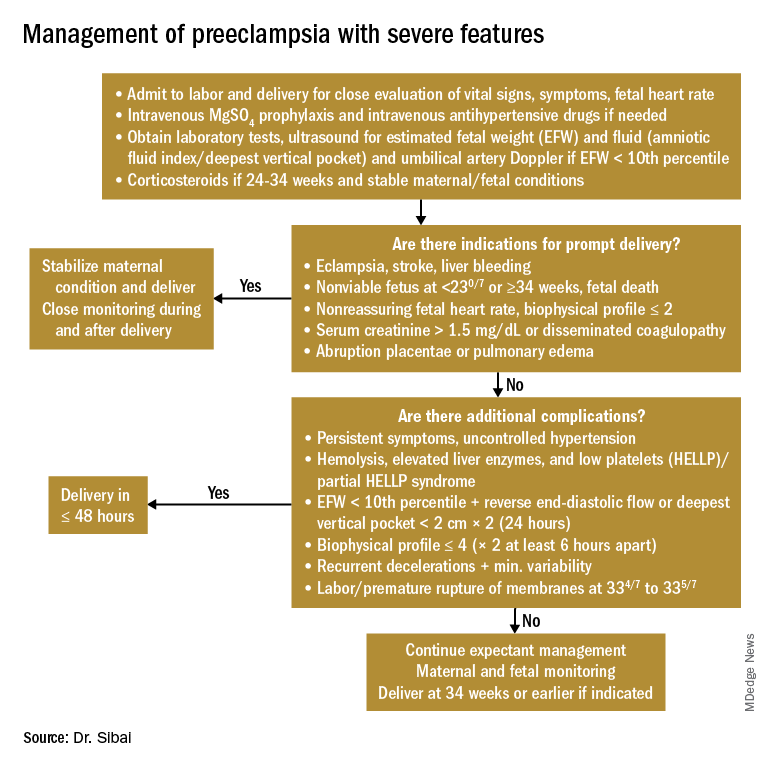

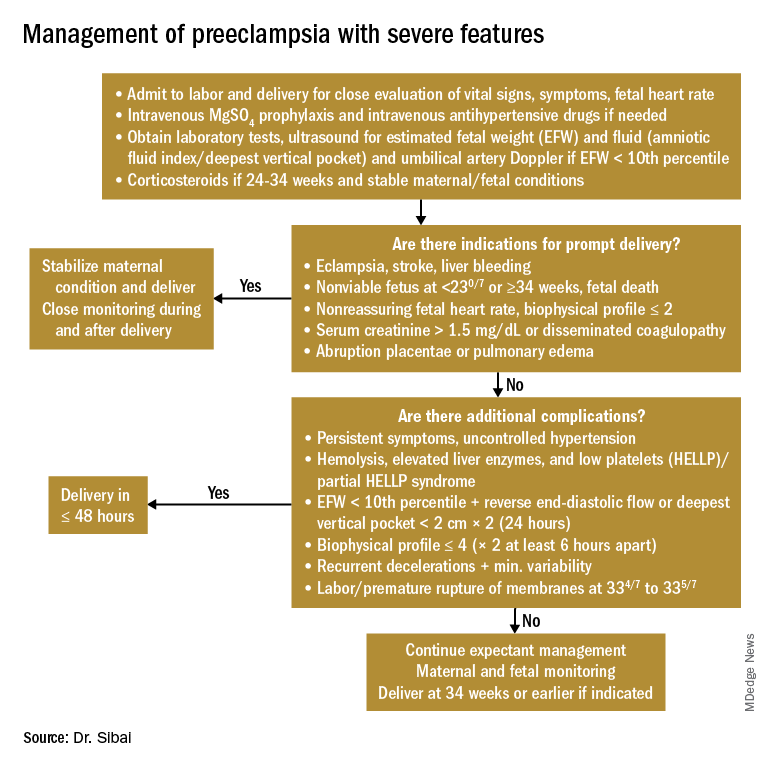

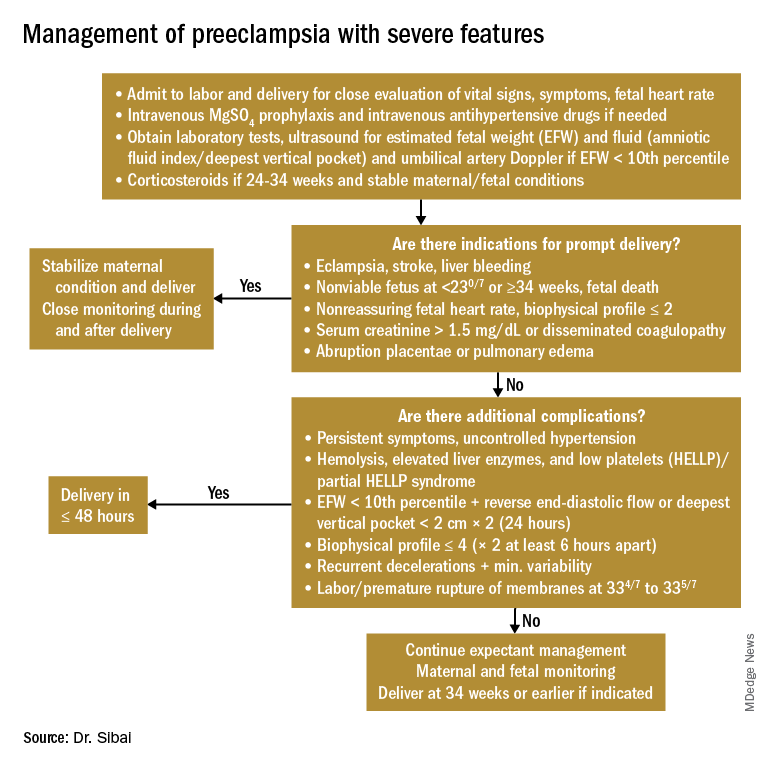

Management of preeclampsia with severe features

Any patient who has preeclampsia with severe features should be admitted and initially observed in a labor and delivery unit. (See related figure.)

Initial workup should include assessment for fetal well-being, monitoring of maternal blood pressure and symptomatology, and laboratory evaluation. Laboratory assessment should include hematocrit, platelet count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). An ultrasound for fetal growth and amniotic fluid index/DVP also should be obtained. Candidates for expectant management should be carefully selected, counseled regarding its risks and benefits, and managed only at tertiary care hospitals.

Fetal well-being should be assessed on a daily basis by NST and on a weekly basis with amniotic fluid/DVP determination. An ultrasound for fetal growth should be performed every 2-3 weeks. Maternal laboratory evaluation should be done daily or every other day. If the patient maintains a stable maternal and fetal course, she may be expectantly managed until 34 weeks. Worsening maternal or fetal status warrants delivery, regardless of gestational age.

Maternal blood pressure (BP) control is essential with expectant management or during delivery. Medications can be given orally or intravenously, as necessary, to maintain a systolic BP of 140-150 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of 90-100 mm Hg. The most commonly used intravenous medications for this purpose are labetalol and hydralazine. Other medications can include oral rapid-acting nifedipine. Subsequent management can include oral medications such as labetalol and long-acting nifedipine. Care should be taken not to drop the blood pressure too rapidly to avoid reduced renal and placental perfusion.

A trial of labor is indicated in patients with severe preeclampsia if gestational age is greater than 30 weeks and/or if cervical Bishop Score is greater than or equal to 6. However, an appropriate time frame should be established regarding achievement of active labor.

Patients should be closely monitored for at least 24 hours post partum. Post partum eclampsia occurs in 30% of patients; thus, women who are receiving magnesium sulfate should continue it for 24 hours after delivery. In addition, women with preeclampsia who are receiving magnesium sulfate are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and should be managed accordingly.

Some patients with severe preeclampsia also are at risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension 3-5 days post partum. Therefore, all patients should receive frequent monitoring of intake and output.

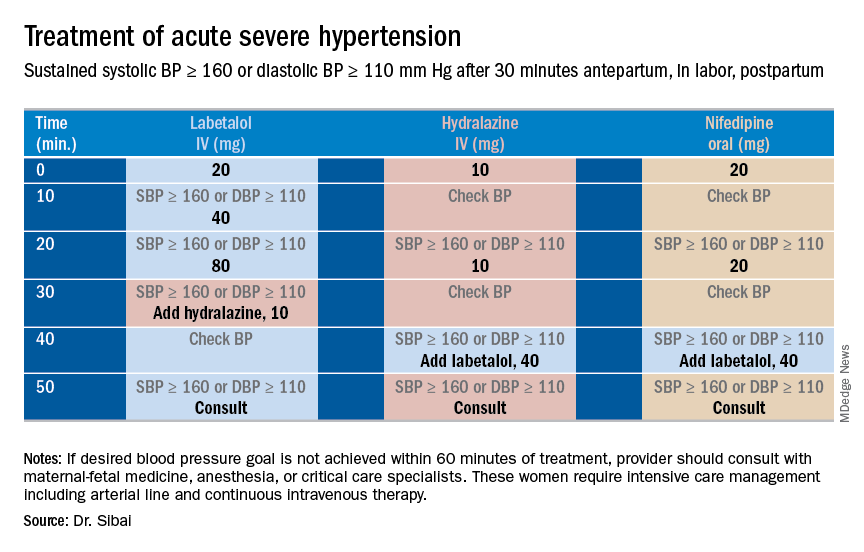

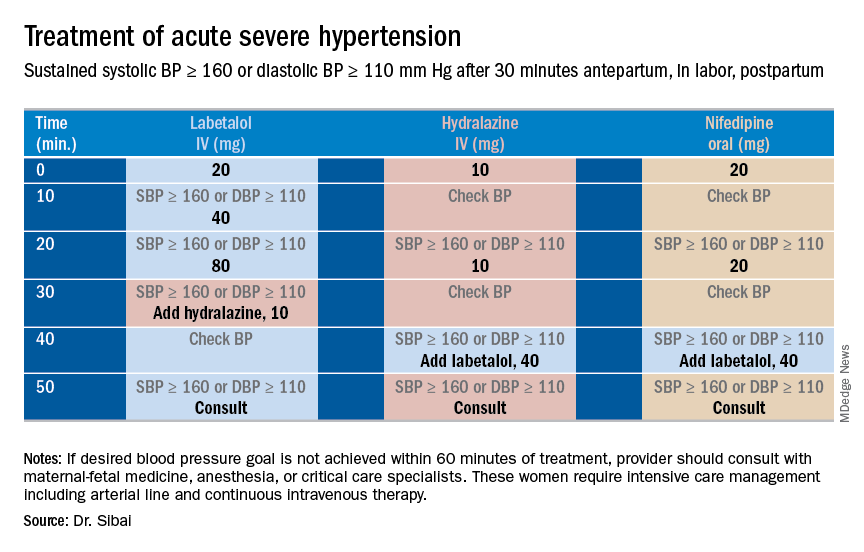

Control of acute severe hypertension antepartum, in labor, or post partum

Uncontrolled severe hypertension for several hours may be associated with stroke and pulmonary edema. Therefore, several guidelines recommend initiation of antihypertensive medications for acute lowering of maternal blood pressure within 30-60 minutes. Several antihypertensive agents are available for the control of sustained severe hypertension before, during, and after delivery. It is important to be familiar with the maternal and fetal side effects, as well as mode of action of each agent, to select the best one. Antihypertensive agents can exert an effect by decreasing cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and central blood pressure, or by inhibiting angiotensin production. Indications for therapy and commonly used drugs in pregnancy are listed in the accompanying table.

Several trials have compared the efficacy and side effects of intravenous bolus injections of hydralazine to either IV labetalol or oral rapid-acting nifedipine as well as oral nifedipine to IV labetalol. The results of these studies suggest that any of these three medications can be used to treat severe hypertension in pregnancy as long as the physician is familiar with the doses to be used, the expected onset of action, and potential side effects.

Because both hydralazine and nifedipine are associated with tachycardia, it is recommended that these agents not be used in patients with a heart rate above 105-110 beats per minute (bpm). It also is important to be attentive to patients with generalized swelling and/or hemoconcentration (hematocrit great than or equal to 40%), as these patients usually have marked reduction in plasma volume and can develop an excessive hypotensive response, with secondary reduction in tissue perfusion and uteroplacental blood flow, when treated with a combination of rapid-acting vasodilators (hydralazine or nifedipine). Such patients may require a bolus infusion of 250-500 mL of isotonic saline prior to the administration of vasodilators. In these patients, labetalol may be the appropriate drug to use.

Labetalol should be avoided in patients with bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm), in those with moderate to severe asthma, and in those with heart failure. In these patients, either hydralazine or nifedipine is the drug of choice. If an intravenous access is not available or difficult to obtain, oral nifedipine should be the drug of choice. In addition, because nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant increase in urine output, it is the drug of choice for treatment in those with decreased urine output, and for treatment of severe hypertension in the postpartum period.

In a third and final installment, I will elaborate on the postpartum management of women who have experienced hypertension with or without associated symptoms. Recently, postpartum hypertension has become a major cause of hospital readmission, as well as severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

Dr. Sibai is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston.

In the last installment of the Master Class, I addressed the importance of clarity in the classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and proposed several key diagnostic definitions. Here, I address the management of “mild” gestational hypertension (GHTN) and preeclampsia without severe features, which I believe should be managed similarly. I also address the management of preeclampsia with severe features, and I share an algorithm that I have developed and fine-tuned over the years to control acute severe hypertension with the use of intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, or oral nifedipine.

Management of “mild” gestational hypertension/Preeclampsia without severe features

Mild gestational hypertension in and of itself has little effect on maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality when it develops at or beyond 37 weeks’ gestation. However, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with preterm GHTN will subsequently develop preeclampsia or progress to severe GHTN. In addition, these pregnancies may result in fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.

Antihypertensive drugs should not be used during ambulatory management of women with GHTN. Patients who receive antihypertensive therapy, including those diagnosed with severe GHTN, should be hospitalized and initially treated as having preeclampsia with or without severe features. Subsequent management will depend on initial response to therapy, blood pressure values after treatment, gestational age, and laboratory findings.

Preeclampsia without severe features is usually managed as in those with GHTN. (See related figure.)

Close surveillance is warranted, as either type may progress to fulminant disease. Maternal surveillance should include blood pressure measurements twice per week, and CBC, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine measurements once every week. Patients also should be instructed to immediately report any of these symptoms: Persistent severe headaches; right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting; scotomata, blurred vision, photophobia, or double vision; shortness of breath or orthopnea; altered mental changes; decreased fetal movement; rupture of membranes; vaginal bleeding; or regular uterine contractions.

Fetal evaluation for patients with GHTN/preeclampsia includes ultrasound at the time of diagnosis for evaluation of fetal growth and amniotic fluid value (deepest vertical pocket, or DVP) as well as fetal movement count and non-stress testing (NST). Subsequently, NST and DVP need to be checked twice per week. A decision for delivery will depend on gestational age, fetal status, and development of severe disease.

Management of preeclampsia with severe features

Any patient who has preeclampsia with severe features should be admitted and initially observed in a labor and delivery unit. (See related figure.)

Initial workup should include assessment for fetal well-being, monitoring of maternal blood pressure and symptomatology, and laboratory evaluation. Laboratory assessment should include hematocrit, platelet count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). An ultrasound for fetal growth and amniotic fluid index/DVP also should be obtained. Candidates for expectant management should be carefully selected, counseled regarding its risks and benefits, and managed only at tertiary care hospitals.

Fetal well-being should be assessed on a daily basis by NST and on a weekly basis with amniotic fluid/DVP determination. An ultrasound for fetal growth should be performed every 2-3 weeks. Maternal laboratory evaluation should be done daily or every other day. If the patient maintains a stable maternal and fetal course, she may be expectantly managed until 34 weeks. Worsening maternal or fetal status warrants delivery, regardless of gestational age.

Maternal blood pressure (BP) control is essential with expectant management or during delivery. Medications can be given orally or intravenously, as necessary, to maintain a systolic BP of 140-150 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of 90-100 mm Hg. The most commonly used intravenous medications for this purpose are labetalol and hydralazine. Other medications can include oral rapid-acting nifedipine. Subsequent management can include oral medications such as labetalol and long-acting nifedipine. Care should be taken not to drop the blood pressure too rapidly to avoid reduced renal and placental perfusion.

A trial of labor is indicated in patients with severe preeclampsia if gestational age is greater than 30 weeks and/or if cervical Bishop Score is greater than or equal to 6. However, an appropriate time frame should be established regarding achievement of active labor.

Patients should be closely monitored for at least 24 hours post partum. Post partum eclampsia occurs in 30% of patients; thus, women who are receiving magnesium sulfate should continue it for 24 hours after delivery. In addition, women with preeclampsia who are receiving magnesium sulfate are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and should be managed accordingly.

Some patients with severe preeclampsia also are at risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension 3-5 days post partum. Therefore, all patients should receive frequent monitoring of intake and output.

Control of acute severe hypertension antepartum, in labor, or post partum

Uncontrolled severe hypertension for several hours may be associated with stroke and pulmonary edema. Therefore, several guidelines recommend initiation of antihypertensive medications for acute lowering of maternal blood pressure within 30-60 minutes. Several antihypertensive agents are available for the control of sustained severe hypertension before, during, and after delivery. It is important to be familiar with the maternal and fetal side effects, as well as mode of action of each agent, to select the best one. Antihypertensive agents can exert an effect by decreasing cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and central blood pressure, or by inhibiting angiotensin production. Indications for therapy and commonly used drugs in pregnancy are listed in the accompanying table.

Several trials have compared the efficacy and side effects of intravenous bolus injections of hydralazine to either IV labetalol or oral rapid-acting nifedipine as well as oral nifedipine to IV labetalol. The results of these studies suggest that any of these three medications can be used to treat severe hypertension in pregnancy as long as the physician is familiar with the doses to be used, the expected onset of action, and potential side effects.

Because both hydralazine and nifedipine are associated with tachycardia, it is recommended that these agents not be used in patients with a heart rate above 105-110 beats per minute (bpm). It also is important to be attentive to patients with generalized swelling and/or hemoconcentration (hematocrit great than or equal to 40%), as these patients usually have marked reduction in plasma volume and can develop an excessive hypotensive response, with secondary reduction in tissue perfusion and uteroplacental blood flow, when treated with a combination of rapid-acting vasodilators (hydralazine or nifedipine). Such patients may require a bolus infusion of 250-500 mL of isotonic saline prior to the administration of vasodilators. In these patients, labetalol may be the appropriate drug to use.

Labetalol should be avoided in patients with bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm), in those with moderate to severe asthma, and in those with heart failure. In these patients, either hydralazine or nifedipine is the drug of choice. If an intravenous access is not available or difficult to obtain, oral nifedipine should be the drug of choice. In addition, because nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant increase in urine output, it is the drug of choice for treatment in those with decreased urine output, and for treatment of severe hypertension in the postpartum period.

In a third and final installment, I will elaborate on the postpartum management of women who have experienced hypertension with or without associated symptoms. Recently, postpartum hypertension has become a major cause of hospital readmission, as well as severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

Dr. Sibai is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston.

In the last installment of the Master Class, I addressed the importance of clarity in the classification of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, and proposed several key diagnostic definitions. Here, I address the management of “mild” gestational hypertension (GHTN) and preeclampsia without severe features, which I believe should be managed similarly. I also address the management of preeclampsia with severe features, and I share an algorithm that I have developed and fine-tuned over the years to control acute severe hypertension with the use of intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, or oral nifedipine.

Management of “mild” gestational hypertension/Preeclampsia without severe features

Mild gestational hypertension in and of itself has little effect on maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality when it develops at or beyond 37 weeks’ gestation. However, approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with preterm GHTN will subsequently develop preeclampsia or progress to severe GHTN. In addition, these pregnancies may result in fetal growth restriction and placental abruption.

Antihypertensive drugs should not be used during ambulatory management of women with GHTN. Patients who receive antihypertensive therapy, including those diagnosed with severe GHTN, should be hospitalized and initially treated as having preeclampsia with or without severe features. Subsequent management will depend on initial response to therapy, blood pressure values after treatment, gestational age, and laboratory findings.

Preeclampsia without severe features is usually managed as in those with GHTN. (See related figure.)

Close surveillance is warranted, as either type may progress to fulminant disease. Maternal surveillance should include blood pressure measurements twice per week, and CBC, liver enzymes, and serum creatinine measurements once every week. Patients also should be instructed to immediately report any of these symptoms: Persistent severe headaches; right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting; scotomata, blurred vision, photophobia, or double vision; shortness of breath or orthopnea; altered mental changes; decreased fetal movement; rupture of membranes; vaginal bleeding; or regular uterine contractions.

Fetal evaluation for patients with GHTN/preeclampsia includes ultrasound at the time of diagnosis for evaluation of fetal growth and amniotic fluid value (deepest vertical pocket, or DVP) as well as fetal movement count and non-stress testing (NST). Subsequently, NST and DVP need to be checked twice per week. A decision for delivery will depend on gestational age, fetal status, and development of severe disease.

Management of preeclampsia with severe features

Any patient who has preeclampsia with severe features should be admitted and initially observed in a labor and delivery unit. (See related figure.)

Initial workup should include assessment for fetal well-being, monitoring of maternal blood pressure and symptomatology, and laboratory evaluation. Laboratory assessment should include hematocrit, platelet count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). An ultrasound for fetal growth and amniotic fluid index/DVP also should be obtained. Candidates for expectant management should be carefully selected, counseled regarding its risks and benefits, and managed only at tertiary care hospitals.

Fetal well-being should be assessed on a daily basis by NST and on a weekly basis with amniotic fluid/DVP determination. An ultrasound for fetal growth should be performed every 2-3 weeks. Maternal laboratory evaluation should be done daily or every other day. If the patient maintains a stable maternal and fetal course, she may be expectantly managed until 34 weeks. Worsening maternal or fetal status warrants delivery, regardless of gestational age.

Maternal blood pressure (BP) control is essential with expectant management or during delivery. Medications can be given orally or intravenously, as necessary, to maintain a systolic BP of 140-150 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of 90-100 mm Hg. The most commonly used intravenous medications for this purpose are labetalol and hydralazine. Other medications can include oral rapid-acting nifedipine. Subsequent management can include oral medications such as labetalol and long-acting nifedipine. Care should be taken not to drop the blood pressure too rapidly to avoid reduced renal and placental perfusion.

A trial of labor is indicated in patients with severe preeclampsia if gestational age is greater than 30 weeks and/or if cervical Bishop Score is greater than or equal to 6. However, an appropriate time frame should be established regarding achievement of active labor.

Patients should be closely monitored for at least 24 hours post partum. Post partum eclampsia occurs in 30% of patients; thus, women who are receiving magnesium sulfate should continue it for 24 hours after delivery. In addition, women with preeclampsia who are receiving magnesium sulfate are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony and should be managed accordingly.

Some patients with severe preeclampsia also are at risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension 3-5 days post partum. Therefore, all patients should receive frequent monitoring of intake and output.

Control of acute severe hypertension antepartum, in labor, or post partum

Uncontrolled severe hypertension for several hours may be associated with stroke and pulmonary edema. Therefore, several guidelines recommend initiation of antihypertensive medications for acute lowering of maternal blood pressure within 30-60 minutes. Several antihypertensive agents are available for the control of sustained severe hypertension before, during, and after delivery. It is important to be familiar with the maternal and fetal side effects, as well as mode of action of each agent, to select the best one. Antihypertensive agents can exert an effect by decreasing cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and central blood pressure, or by inhibiting angiotensin production. Indications for therapy and commonly used drugs in pregnancy are listed in the accompanying table.

Several trials have compared the efficacy and side effects of intravenous bolus injections of hydralazine to either IV labetalol or oral rapid-acting nifedipine as well as oral nifedipine to IV labetalol. The results of these studies suggest that any of these three medications can be used to treat severe hypertension in pregnancy as long as the physician is familiar with the doses to be used, the expected onset of action, and potential side effects.

Because both hydralazine and nifedipine are associated with tachycardia, it is recommended that these agents not be used in patients with a heart rate above 105-110 beats per minute (bpm). It also is important to be attentive to patients with generalized swelling and/or hemoconcentration (hematocrit great than or equal to 40%), as these patients usually have marked reduction in plasma volume and can develop an excessive hypotensive response, with secondary reduction in tissue perfusion and uteroplacental blood flow, when treated with a combination of rapid-acting vasodilators (hydralazine or nifedipine). Such patients may require a bolus infusion of 250-500 mL of isotonic saline prior to the administration of vasodilators. In these patients, labetalol may be the appropriate drug to use.

Labetalol should be avoided in patients with bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm), in those with moderate to severe asthma, and in those with heart failure. In these patients, either hydralazine or nifedipine is the drug of choice. If an intravenous access is not available or difficult to obtain, oral nifedipine should be the drug of choice. In addition, because nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant increase in urine output, it is the drug of choice for treatment in those with decreased urine output, and for treatment of severe hypertension in the postpartum period.

In a third and final installment, I will elaborate on the postpartum management of women who have experienced hypertension with or without associated symptoms. Recently, postpartum hypertension has become a major cause of hospital readmission, as well as severe maternal morbidity and mortality.

Dr. Sibai is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston.

Treating preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is such a complicated and insidious disease – and one with such serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother – that we decided to run a three-part series on its diagnosis and management. The complication can have an acute onset in many patients, and this acute onset may rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for obstetricians to be able to affect the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

I have invited Dr. Baha M. Sibai, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to deliver this series. Our first installment addressed diagnostic criteria and attempted to clarify confusion that may have been introduced with the 2013 publication of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy. It is important that the diagnostic criteria are well established and understood because the management of patients is very much based on accurate placement within these diagnostic criteria.

This second installment of our series focuses on the application of appropriate therapeutic measures for various diagnostic groups. Dr. Sibai has spent decades studying hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and developing practical clinical strategies for management. It is our hope that the guidance and algorithms presented here will be useful for improving patient care and outcomes of this serious obstetrical syndrome. A third installment on postpartum management will come later.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Preeclampsia is such a complicated and insidious disease – and one with such serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother – that we decided to run a three-part series on its diagnosis and management. The complication can have an acute onset in many patients, and this acute onset may rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for obstetricians to be able to affect the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

I have invited Dr. Baha M. Sibai, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to deliver this series. Our first installment addressed diagnostic criteria and attempted to clarify confusion that may have been introduced with the 2013 publication of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy. It is important that the diagnostic criteria are well established and understood because the management of patients is very much based on accurate placement within these diagnostic criteria.

This second installment of our series focuses on the application of appropriate therapeutic measures for various diagnostic groups. Dr. Sibai has spent decades studying hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and developing practical clinical strategies for management. It is our hope that the guidance and algorithms presented here will be useful for improving patient care and outcomes of this serious obstetrical syndrome. A third installment on postpartum management will come later.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Preeclampsia is such a complicated and insidious disease – and one with such serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother – that we decided to run a three-part series on its diagnosis and management. The complication can have an acute onset in many patients, and this acute onset may rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for obstetricians to be able to affect the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

I have invited Dr. Baha M. Sibai, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to deliver this series. Our first installment addressed diagnostic criteria and attempted to clarify confusion that may have been introduced with the 2013 publication of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy. It is important that the diagnostic criteria are well established and understood because the management of patients is very much based on accurate placement within these diagnostic criteria.

This second installment of our series focuses on the application of appropriate therapeutic measures for various diagnostic groups. Dr. Sibai has spent decades studying hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and developing practical clinical strategies for management. It is our hope that the guidance and algorithms presented here will be useful for improving patient care and outcomes of this serious obstetrical syndrome. A third installment on postpartum management will come later.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Endometrial scratching doesn’t lead to higher live birth rate for IVF patients

Endometrial scratching prior to a fresh embryo or frozen embryo transfer did not result in a higher rate of live births for women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), according to results from a recent randomized controlled trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Sarah Lensen, PhD, of the University of Auckland in New Zealand, and her colleagues recruited 1,364 women from 13 sites in 5 countries in 2014-2017 who did not have a recent history of disruptive intrauterine instrumentation such as hysteroscopy or endometrial biopsy and were planning an IVF cycle with a fresh or frozen embryo transfer. The women were randomized to receive endometrial scratching through pipelle biopsy between day 3 of the cycle prior to IVF and day 3 of the IVF cycle. Live birth was the primary outcome, while secondary outcomes measured included ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and biochemical pregnancy, as well as miscarriage, termination of pregnancy, stillbirth, and other maternal and neonatal outcomes.

For the endometrial scratch group, the rate of live birth was 26% (180 of 690 women), compared with 26% (176 of 674 women) in the control group (adjusted odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-1.27, P = .97). The rate of ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage also did not significantly differ between groups.

Among women who underwent endometrial scratching, there was a median pain score of 3.5 points from a range of 0-10 points; 37 women reported a pain scale score of 0, while 6 said their pain score was a 10. Adverse reactions to endometrial scratching included fainting, dizziness and/or nausea (7 women); excessive pain (5 women), including 1 woman who went to the emergency department after a concurrent endometrial scratch and sonohysterogram procedure; and excessive bleeding (2 women).

The researchers noted several limitations in their study, including its unblinded design; tracking of adverse outcomes in the endometrial scratch group only; and a definition of implantation failure not based on embryo or transfer quality, but on the number of previous unsuccessful transfers. There were also “imbalances favoring the endometrial scratch group” based on the number of available oocytes per participant and willingness to begin their IVF cycle.

“Women in the endometrial scratch group may have been more likely to start their cycle in order to capitalize on their exposure to the endometrial scratch. However, results were materially unchanged in a per-protocol analysis,” the researchers said.

This study was funded in part by the University of Auckland, the A+ Trust, Auckland District Health Board, the Nurture Foundation, and the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust. Dr. Priya Bhide received personal fees from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and grants from Bart’s Charity, Pharmasure Pharmaceuticals, and Finox Pharmaceuticals. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lensen S et al. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808737.

The results of a large, pragmatic trial by Lensen et al., examining the effects of endometrial scratching, which used current standards of care for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and included women undergoing treatment for the first time in addition to those who have had previously failed cycles, should be trusted despite contrary data from other studies, Ben W. Mol, MD, PhD, and Kurt T. Barnhart, MD, MSCE, wrote in a related editorial.

Although a Cochrane systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials found evidence of an increased live birth rate for women undergoing IVF after an endometrial scratch procedure (risk ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.85), many trials in the meta-analysis had “unrealistic” large effect sizes within limited sample sizes, were not optimally randomized, were stopped prematurely, or were not prospectively registered, they noted.

“Rigorous synthesis of bad data cannot overcome bias from uncontrolled or poorly conducted studies; it may result only in tighter confidence around a spurious conclusion, an answer that is precisely wrong,” they said.

However, as the results from Lensen et al. show, there were a low number of reported adverse events, and “on the basis of the current report, the IVF community can take solace in the observation that ‘scratching’ apparently caused no harm, other than some procedure-associated pain and bleeding.”

Any adjuvant to IVF should be “evaluated carefully before being offered to infertility couples” and it is still an unanswered question as to whether IVF doctors should continue to offer unevaluated adjuvants to their patients, Dr. Mol and Dr. Barnhart said.

“The population affected by infertility has been described as vulnerable. The goals of reproductive medicine are the same as those of other fields of medicine: Provide compassionate and effective care, do no harm, and do not offer false hope or sell snake oil,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mol is at Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and Dr. Barnhart is at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. This commentary summarizes their editorial on the study by Lensen et al. (N Eng J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1815042 ). Dr. Mol disclosed ties with Merck, Guerbet, and ObsEva, outside the submitted work. Dr. Barnhart had no relevant disclosures.

The results of a large, pragmatic trial by Lensen et al., examining the effects of endometrial scratching, which used current standards of care for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and included women undergoing treatment for the first time in addition to those who have had previously failed cycles, should be trusted despite contrary data from other studies, Ben W. Mol, MD, PhD, and Kurt T. Barnhart, MD, MSCE, wrote in a related editorial.

Although a Cochrane systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials found evidence of an increased live birth rate for women undergoing IVF after an endometrial scratch procedure (risk ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.85), many trials in the meta-analysis had “unrealistic” large effect sizes within limited sample sizes, were not optimally randomized, were stopped prematurely, or were not prospectively registered, they noted.

“Rigorous synthesis of bad data cannot overcome bias from uncontrolled or poorly conducted studies; it may result only in tighter confidence around a spurious conclusion, an answer that is precisely wrong,” they said.

However, as the results from Lensen et al. show, there were a low number of reported adverse events, and “on the basis of the current report, the IVF community can take solace in the observation that ‘scratching’ apparently caused no harm, other than some procedure-associated pain and bleeding.”

Any adjuvant to IVF should be “evaluated carefully before being offered to infertility couples” and it is still an unanswered question as to whether IVF doctors should continue to offer unevaluated adjuvants to their patients, Dr. Mol and Dr. Barnhart said.

“The population affected by infertility has been described as vulnerable. The goals of reproductive medicine are the same as those of other fields of medicine: Provide compassionate and effective care, do no harm, and do not offer false hope or sell snake oil,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mol is at Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and Dr. Barnhart is at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. This commentary summarizes their editorial on the study by Lensen et al. (N Eng J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1815042 ). Dr. Mol disclosed ties with Merck, Guerbet, and ObsEva, outside the submitted work. Dr. Barnhart had no relevant disclosures.

The results of a large, pragmatic trial by Lensen et al., examining the effects of endometrial scratching, which used current standards of care for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and included women undergoing treatment for the first time in addition to those who have had previously failed cycles, should be trusted despite contrary data from other studies, Ben W. Mol, MD, PhD, and Kurt T. Barnhart, MD, MSCE, wrote in a related editorial.

Although a Cochrane systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials found evidence of an increased live birth rate for women undergoing IVF after an endometrial scratch procedure (risk ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.85), many trials in the meta-analysis had “unrealistic” large effect sizes within limited sample sizes, were not optimally randomized, were stopped prematurely, or were not prospectively registered, they noted.

“Rigorous synthesis of bad data cannot overcome bias from uncontrolled or poorly conducted studies; it may result only in tighter confidence around a spurious conclusion, an answer that is precisely wrong,” they said.

However, as the results from Lensen et al. show, there were a low number of reported adverse events, and “on the basis of the current report, the IVF community can take solace in the observation that ‘scratching’ apparently caused no harm, other than some procedure-associated pain and bleeding.”

Any adjuvant to IVF should be “evaluated carefully before being offered to infertility couples” and it is still an unanswered question as to whether IVF doctors should continue to offer unevaluated adjuvants to their patients, Dr. Mol and Dr. Barnhart said.

“The population affected by infertility has been described as vulnerable. The goals of reproductive medicine are the same as those of other fields of medicine: Provide compassionate and effective care, do no harm, and do not offer false hope or sell snake oil,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Mol is at Monash University in Clayton, Australia, and Dr. Barnhart is at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. This commentary summarizes their editorial on the study by Lensen et al. (N Eng J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1815042 ). Dr. Mol disclosed ties with Merck, Guerbet, and ObsEva, outside the submitted work. Dr. Barnhart had no relevant disclosures.

Endometrial scratching prior to a fresh embryo or frozen embryo transfer did not result in a higher rate of live births for women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), according to results from a recent randomized controlled trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Sarah Lensen, PhD, of the University of Auckland in New Zealand, and her colleagues recruited 1,364 women from 13 sites in 5 countries in 2014-2017 who did not have a recent history of disruptive intrauterine instrumentation such as hysteroscopy or endometrial biopsy and were planning an IVF cycle with a fresh or frozen embryo transfer. The women were randomized to receive endometrial scratching through pipelle biopsy between day 3 of the cycle prior to IVF and day 3 of the IVF cycle. Live birth was the primary outcome, while secondary outcomes measured included ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and biochemical pregnancy, as well as miscarriage, termination of pregnancy, stillbirth, and other maternal and neonatal outcomes.

For the endometrial scratch group, the rate of live birth was 26% (180 of 690 women), compared with 26% (176 of 674 women) in the control group (adjusted odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-1.27, P = .97). The rate of ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage also did not significantly differ between groups.

Among women who underwent endometrial scratching, there was a median pain score of 3.5 points from a range of 0-10 points; 37 women reported a pain scale score of 0, while 6 said their pain score was a 10. Adverse reactions to endometrial scratching included fainting, dizziness and/or nausea (7 women); excessive pain (5 women), including 1 woman who went to the emergency department after a concurrent endometrial scratch and sonohysterogram procedure; and excessive bleeding (2 women).

The researchers noted several limitations in their study, including its unblinded design; tracking of adverse outcomes in the endometrial scratch group only; and a definition of implantation failure not based on embryo or transfer quality, but on the number of previous unsuccessful transfers. There were also “imbalances favoring the endometrial scratch group” based on the number of available oocytes per participant and willingness to begin their IVF cycle.

“Women in the endometrial scratch group may have been more likely to start their cycle in order to capitalize on their exposure to the endometrial scratch. However, results were materially unchanged in a per-protocol analysis,” the researchers said.

This study was funded in part by the University of Auckland, the A+ Trust, Auckland District Health Board, the Nurture Foundation, and the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust. Dr. Priya Bhide received personal fees from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and grants from Bart’s Charity, Pharmasure Pharmaceuticals, and Finox Pharmaceuticals. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lensen S et al. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808737.

Endometrial scratching prior to a fresh embryo or frozen embryo transfer did not result in a higher rate of live births for women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF), according to results from a recent randomized controlled trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Sarah Lensen, PhD, of the University of Auckland in New Zealand, and her colleagues recruited 1,364 women from 13 sites in 5 countries in 2014-2017 who did not have a recent history of disruptive intrauterine instrumentation such as hysteroscopy or endometrial biopsy and were planning an IVF cycle with a fresh or frozen embryo transfer. The women were randomized to receive endometrial scratching through pipelle biopsy between day 3 of the cycle prior to IVF and day 3 of the IVF cycle. Live birth was the primary outcome, while secondary outcomes measured included ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and biochemical pregnancy, as well as miscarriage, termination of pregnancy, stillbirth, and other maternal and neonatal outcomes.

For the endometrial scratch group, the rate of live birth was 26% (180 of 690 women), compared with 26% (176 of 674 women) in the control group (adjusted odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-1.27, P = .97). The rate of ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage also did not significantly differ between groups.

Among women who underwent endometrial scratching, there was a median pain score of 3.5 points from a range of 0-10 points; 37 women reported a pain scale score of 0, while 6 said their pain score was a 10. Adverse reactions to endometrial scratching included fainting, dizziness and/or nausea (7 women); excessive pain (5 women), including 1 woman who went to the emergency department after a concurrent endometrial scratch and sonohysterogram procedure; and excessive bleeding (2 women).