User login

Incidence of late-onset GBS cases are higher than early-onset disease

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

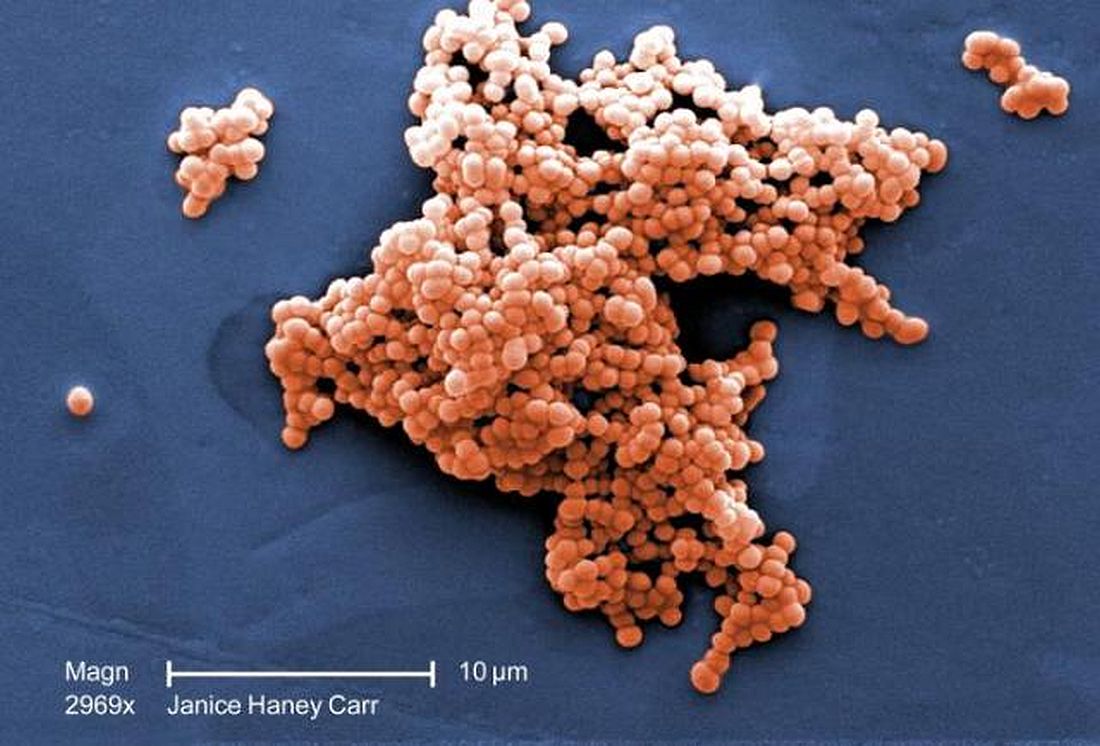

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Between 2006 and 2015, early-onset disease cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) declined, while the incidence of late-onset cases did not change.

Major finding: The rate of early-onset GBS declined from 0.37 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births and the rate of late-onset GBS cases remained at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births.

Study details: A population-based study of infants with early-onset disease and late-onset disease GBS from 10 different states in the Active Bacterial Core surveillance program between 2006 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Think outside lower body for pelvic pain

Also today, treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure decreased amyloid levels, spending on medical marketing increased by more than $12 billion over that past two decades, and one expert has advice on how you can get your work published.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure decreased amyloid levels, spending on medical marketing increased by more than $12 billion over that past two decades, and one expert has advice on how you can get your work published.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure decreased amyloid levels, spending on medical marketing increased by more than $12 billion over that past two decades, and one expert has advice on how you can get your work published.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

ACOG updates guidance on chronic hypertension in pregnancy, gestational hypertension

Ob.gyns. will need to focus more on individualized care as they use the two new practice bulletins, one on chronic hypertension in pregnancy and one on gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, released by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics.

The bulletins will replace the 2013 ACOG hypertension in pregnancy task force report and are published in the January issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The task force was a tour de force in creating a comprehensive view of hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, including research,” Christian M. Pettker, MD, who helped develop both practice bulletins, stated in a press release. “The updated guidance provides clearer recommendations for the management of gestational hypertension with severe-range blood pressure, an emphasis on and instructions for timely treatment of acutely elevated blood pressures, and more defined recommendations for the management of pain in postoperative patients with hypertension.”

“Ob.gyns. will need to focus more on individualized care and may find it’s best to err on the side of caution because the appropriate treatment of hypertensive diseases in pregnancy may be the most important focus of our attempts to improve maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States,” he said.*

Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia

For women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at 37 weeks of gestation or later without severe features, the guidelines recommend delivery rather than expectant management.

Those patients with severe features of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia or eclampsia should receive magnesium sulfate to prevent or treat seizures.

Patients should receive low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day) for preeclampsia prophylaxis between 12 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation if they have high-risk factors of preeclampsia such as multifetal gestation, a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia, renal disease, autoimmune disease, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, or a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia; or more than one moderate risk factor such as a family history of preeclampsia, maternal age greater than 35 years, first pregnancy, body mass index greater than 30, personal history factors, or sociodemographic characteristics.

NSAIDs should continue to be used in preference to opioid analgesics.

The guidance also discusses mode of delivery, antihypertensive drugs and thresholds for treatment, management of acute complications for preeclampsia with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome, the optimal treatment for eclampsia, and postpartum hypertension and headache.

Chronic hypertension

Pregnant women with chronic hypertension also should receive low-dose aspirin between 12 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation. Antihypertensive therapy should be initiated for women with persistent chronic hypertension at systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher and/or diastolic pressure of 110 mm Hg or higher. Consider treating patients at lower blood pressure (BP) thresholds depending on comorbidities or underlying impaired renal function.

ACOG has recommended treating pregnant patients as chronically hypertensive according to recently changed criteria from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, which call for classifying blood pressure into the following categories:

- Normal. Systolic BP less than 120 mm Hg; diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg.

- Elevated. Systolic BP greater than or equal to 120-129 mm Hg; diastolic BP greater than 80 mm Hg.

- Stage 1 hypertension. Systolic BP, 130-139 mm Hg; diastolic BP, 80-89 mm Hg.

- Stage 2 hypertension. Systolic BP greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg; diastolic BP greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg.

“The new blood pressure ranges for nonpregnant women have a lower threshold for hypertension diagnosis compared to ACOG’s criteria,” Dr. Pettker said. “This will likely cause a general increase in patients classified as chronic hypertensive and will require shared decision making by the ob.gyn. and the patient regarding appropriate management in pregnancy.”

The guideline also discusses chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia; tests for baseline evaluation of chronic hypertension in pregnancy; common oral antihypertensive agents to use in pregnancy and those to use for urgent blood pressure control in pregnancy; control of acute-onset severe-range hypertension; and postpartum considerations in patients with chronic hypertension.

SOURCE: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-25; Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26-50.

This article was updated 1/11/19 and 11/19/19.

Ob.gyns. will need to focus more on individualized care as they use the two new practice bulletins, one on chronic hypertension in pregnancy and one on gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, released by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics.

The bulletins will replace the 2013 ACOG hypertension in pregnancy task force report and are published in the January issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The task force was a tour de force in creating a comprehensive view of hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, including research,” Christian M. Pettker, MD, who helped develop both practice bulletins, stated in a press release. “The updated guidance provides clearer recommendations for the management of gestational hypertension with severe-range blood pressure, an emphasis on and instructions for timely treatment of acutely elevated blood pressures, and more defined recommendations for the management of pain in postoperative patients with hypertension.”

“Ob.gyns. will need to focus more on individualized care and may find it’s best to err on the side of caution because the appropriate treatment of hypertensive diseases in pregnancy may be the most important focus of our attempts to improve maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States,” he said.*

Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia

For women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at 37 weeks of gestation or later without severe features, the guidelines recommend delivery rather than expectant management.

Those patients with severe features of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia or eclampsia should receive magnesium sulfate to prevent or treat seizures.

Patients should receive low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day) for preeclampsia prophylaxis between 12 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation if they have high-risk factors of preeclampsia such as multifetal gestation, a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia, renal disease, autoimmune disease, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, or a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia; or more than one moderate risk factor such as a family history of preeclampsia, maternal age greater than 35 years, first pregnancy, body mass index greater than 30, personal history factors, or sociodemographic characteristics.

NSAIDs should continue to be used in preference to opioid analgesics.

The guidance also discusses mode of delivery, antihypertensive drugs and thresholds for treatment, management of acute complications for preeclampsia with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome, the optimal treatment for eclampsia, and postpartum hypertension and headache.

Chronic hypertension

Pregnant women with chronic hypertension also should receive low-dose aspirin between 12 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation. Antihypertensive therapy should be initiated for women with persistent chronic hypertension at systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher and/or diastolic pressure of 110 mm Hg or higher. Consider treating patients at lower blood pressure (BP) thresholds depending on comorbidities or underlying impaired renal function.

ACOG has recommended treating pregnant patients as chronically hypertensive according to recently changed criteria from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, which call for classifying blood pressure into the following categories:

- Normal. Systolic BP less than 120 mm Hg; diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg.

- Elevated. Systolic BP greater than or equal to 120-129 mm Hg; diastolic BP greater than 80 mm Hg.

- Stage 1 hypertension. Systolic BP, 130-139 mm Hg; diastolic BP, 80-89 mm Hg.

- Stage 2 hypertension. Systolic BP greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg; diastolic BP greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg.

“The new blood pressure ranges for nonpregnant women have a lower threshold for hypertension diagnosis compared to ACOG’s criteria,” Dr. Pettker said. “This will likely cause a general increase in patients classified as chronic hypertensive and will require shared decision making by the ob.gyn. and the patient regarding appropriate management in pregnancy.”

The guideline also discusses chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia; tests for baseline evaluation of chronic hypertension in pregnancy; common oral antihypertensive agents to use in pregnancy and those to use for urgent blood pressure control in pregnancy; control of acute-onset severe-range hypertension; and postpartum considerations in patients with chronic hypertension.

SOURCE: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-25; Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26-50.

This article was updated 1/11/19 and 11/19/19.

Ob.gyns. will need to focus more on individualized care as they use the two new practice bulletins, one on chronic hypertension in pregnancy and one on gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, released by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics.

The bulletins will replace the 2013 ACOG hypertension in pregnancy task force report and are published in the January issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“The task force was a tour de force in creating a comprehensive view of hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, including research,” Christian M. Pettker, MD, who helped develop both practice bulletins, stated in a press release. “The updated guidance provides clearer recommendations for the management of gestational hypertension with severe-range blood pressure, an emphasis on and instructions for timely treatment of acutely elevated blood pressures, and more defined recommendations for the management of pain in postoperative patients with hypertension.”

“Ob.gyns. will need to focus more on individualized care and may find it’s best to err on the side of caution because the appropriate treatment of hypertensive diseases in pregnancy may be the most important focus of our attempts to improve maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States,” he said.*

Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia

For women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at 37 weeks of gestation or later without severe features, the guidelines recommend delivery rather than expectant management.

Those patients with severe features of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia or eclampsia should receive magnesium sulfate to prevent or treat seizures.

Patients should receive low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day) for preeclampsia prophylaxis between 12 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation if they have high-risk factors of preeclampsia such as multifetal gestation, a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia, renal disease, autoimmune disease, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, or a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia; or more than one moderate risk factor such as a family history of preeclampsia, maternal age greater than 35 years, first pregnancy, body mass index greater than 30, personal history factors, or sociodemographic characteristics.

NSAIDs should continue to be used in preference to opioid analgesics.

The guidance also discusses mode of delivery, antihypertensive drugs and thresholds for treatment, management of acute complications for preeclampsia with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome, the optimal treatment for eclampsia, and postpartum hypertension and headache.

Chronic hypertension

Pregnant women with chronic hypertension also should receive low-dose aspirin between 12 weeks and 28 weeks of gestation. Antihypertensive therapy should be initiated for women with persistent chronic hypertension at systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher and/or diastolic pressure of 110 mm Hg or higher. Consider treating patients at lower blood pressure (BP) thresholds depending on comorbidities or underlying impaired renal function.

ACOG has recommended treating pregnant patients as chronically hypertensive according to recently changed criteria from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, which call for classifying blood pressure into the following categories:

- Normal. Systolic BP less than 120 mm Hg; diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg.

- Elevated. Systolic BP greater than or equal to 120-129 mm Hg; diastolic BP greater than 80 mm Hg.

- Stage 1 hypertension. Systolic BP, 130-139 mm Hg; diastolic BP, 80-89 mm Hg.

- Stage 2 hypertension. Systolic BP greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg; diastolic BP greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg.

“The new blood pressure ranges for nonpregnant women have a lower threshold for hypertension diagnosis compared to ACOG’s criteria,” Dr. Pettker said. “This will likely cause a general increase in patients classified as chronic hypertensive and will require shared decision making by the ob.gyn. and the patient regarding appropriate management in pregnancy.”

The guideline also discusses chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia; tests for baseline evaluation of chronic hypertension in pregnancy; common oral antihypertensive agents to use in pregnancy and those to use for urgent blood pressure control in pregnancy; control of acute-onset severe-range hypertension; and postpartum considerations in patients with chronic hypertension.

SOURCE: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-25; Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26-50.

This article was updated 1/11/19 and 11/19/19.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Proposed triple I criteria may overlook febrile women at risk post partum

A large proportion of laboring febrile women are not meeting proposed criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (triple I), but still may be at risk, according to an analysis of expert recommendations for clinical diagnosis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Our data suggest caution in universal implementation of the triple I criteria to guide clinical management of febrile women in the intrapartum period,” according to lead author Samsiya Ona, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

In early 2015, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established criteria for diagnosing triple I in an effort to “decrease overtreatment of intrapartum women and low-risk newborns.” To assess the validity of those criteria, Dr. Ona and her colleagues analyzed 339 women with a temperature taken of 100.4°F or greater (38.0°C) during labor or within 1 hour post partum from June 2015 to September 2017.

The women were split into two groups: 212 met criteria for suspected triple I (documented fever plus clinical signs of intrauterine infection such as maternal leukocytosis greater than 15,000 per mm3, fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats per minute, and purulent amniotic fluid) and 127 met criteria for isolated maternal fever. Among the suspected triple I group, incidence of adverse clinical infectious outcomes was 12%, comparable with 10% in the isolated maternal fever group (P = .50). When it came to predicting confirmed triple I, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 71% (95% confidence interval, 61.4%-80.1%) and 41% (95% CI, 33.6%-47.8%), respectively. For predicting adverse clinical infectious outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 68% (95% CI, 50.2%-82.0%) and 38% (95% CI, 32.6%-43.8%).

The authors cited among study limitations their including only women who had blood cultures sent at initial fever and excluding women who did not have repeat febrile temperature taken within 45 minutes. However, they noted the benefits of working with “a unique, large database with physiologic, laboratory, and microbiological parameters” and emphasized the need for an improved method of diagnosis, suggesting “a simple bedside minimally invasive marker of infection may be ideal.”

The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

A large proportion of laboring febrile women are not meeting proposed criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (triple I), but still may be at risk, according to an analysis of expert recommendations for clinical diagnosis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Our data suggest caution in universal implementation of the triple I criteria to guide clinical management of febrile women in the intrapartum period,” according to lead author Samsiya Ona, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

In early 2015, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established criteria for diagnosing triple I in an effort to “decrease overtreatment of intrapartum women and low-risk newborns.” To assess the validity of those criteria, Dr. Ona and her colleagues analyzed 339 women with a temperature taken of 100.4°F or greater (38.0°C) during labor or within 1 hour post partum from June 2015 to September 2017.

The women were split into two groups: 212 met criteria for suspected triple I (documented fever plus clinical signs of intrauterine infection such as maternal leukocytosis greater than 15,000 per mm3, fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats per minute, and purulent amniotic fluid) and 127 met criteria for isolated maternal fever. Among the suspected triple I group, incidence of adverse clinical infectious outcomes was 12%, comparable with 10% in the isolated maternal fever group (P = .50). When it came to predicting confirmed triple I, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 71% (95% confidence interval, 61.4%-80.1%) and 41% (95% CI, 33.6%-47.8%), respectively. For predicting adverse clinical infectious outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 68% (95% CI, 50.2%-82.0%) and 38% (95% CI, 32.6%-43.8%).

The authors cited among study limitations their including only women who had blood cultures sent at initial fever and excluding women who did not have repeat febrile temperature taken within 45 minutes. However, they noted the benefits of working with “a unique, large database with physiologic, laboratory, and microbiological parameters” and emphasized the need for an improved method of diagnosis, suggesting “a simple bedside minimally invasive marker of infection may be ideal.”

The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

A large proportion of laboring febrile women are not meeting proposed criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (triple I), but still may be at risk, according to an analysis of expert recommendations for clinical diagnosis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Our data suggest caution in universal implementation of the triple I criteria to guide clinical management of febrile women in the intrapartum period,” according to lead author Samsiya Ona, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

In early 2015, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established criteria for diagnosing triple I in an effort to “decrease overtreatment of intrapartum women and low-risk newborns.” To assess the validity of those criteria, Dr. Ona and her colleagues analyzed 339 women with a temperature taken of 100.4°F or greater (38.0°C) during labor or within 1 hour post partum from June 2015 to September 2017.

The women were split into two groups: 212 met criteria for suspected triple I (documented fever plus clinical signs of intrauterine infection such as maternal leukocytosis greater than 15,000 per mm3, fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats per minute, and purulent amniotic fluid) and 127 met criteria for isolated maternal fever. Among the suspected triple I group, incidence of adverse clinical infectious outcomes was 12%, comparable with 10% in the isolated maternal fever group (P = .50). When it came to predicting confirmed triple I, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 71% (95% confidence interval, 61.4%-80.1%) and 41% (95% CI, 33.6%-47.8%), respectively. For predicting adverse clinical infectious outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 68% (95% CI, 50.2%-82.0%) and 38% (95% CI, 32.6%-43.8%).

The authors cited among study limitations their including only women who had blood cultures sent at initial fever and excluding women who did not have repeat febrile temperature taken within 45 minutes. However, they noted the benefits of working with “a unique, large database with physiologic, laboratory, and microbiological parameters” and emphasized the need for an improved method of diagnosis, suggesting “a simple bedside minimally invasive marker of infection may be ideal.”

The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria to predict an adverse clinical infectious outcome were 68% for the suspected triple I group and 38% for the isolated maternal fever group.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 339 women with intrapartum fever from June 2015 to September 2017.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

2019 Update on Obstetrics

The past year was an exciting one in obstetrics. The landmark ARRIVE trial presented at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine’s (SMFM) annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine contradicted a long-held belief about the safety of elective labor induction. In a large randomized trial, Cahill and colleagues took a controversial but practical clinical question about second-stage labor management and answered it for the practicing obstetrician in the trenches. Finally, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) placed new emphasis on the oft overlooked but increasingly more complicated postpartum period, offering guidance to support improving care for women in this transitional period.

Ultimately, this was the year of the patient, as research, clinical guidelines, and education focused on how to achieve the best in safety and quality of care for delivery planning, the delivery itself, and the so-called fourth trimester.

ARRIVE: Labor induction at 39 weeks reduces CD rate with no difference in perinatal death or serious outcomes

Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

The term "elective induction of labor" has long had a negative connotation because of its association with increased CD rates and adverse perinatal outcomes. This view was based on results from older observational studies that compared outcomes for labor induction with those of spontaneous labor. In more recent observational studies that more appropriately compared labor induction with expectant management, however, elective induction of labor appears to be associated with similar CD rates and perinatal outcomes.

To test the hypothesis that elective induction would have a lower risk for perinatal death or severe neonatal complications than expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women, Grobman and colleagues conducted A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management (ARRIVE).1

Study population, timing of delivery, and trial outcomes

This randomized controlled trial included 6,106 women at 41 US centers in the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Study participants were low-risk nulliparous women with a singleton vertex fetus who were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 39 to 39 4/7 weeks (n = 3,062) or expectant management (n = 3,044) until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks.

"Low risk" was defined as having no maternal or fetal indication for delivery prior to 40 5/7 weeks. Reliable gestational dating was required.

While no specific protocol for induction of labor management was required, there were 2 requests: 1) Cervical ripening was requested for an unfavorable cervix (63% of participants had a modified Bishop score <5), and 2) a duration of at least 12 hours after cervical ripening, rupture of membranes, and use of uterine stimulant was requested before performing a CD for "failed induction" (if medically appropriate).

The primary outcome was a composite of perinatal death or serious neonatal complications. The main secondary outcome was CD.

Potentially game-changing findings

The investigators found that there was no statistically significant difference between the elective induction and expectant management groups for the primary composite perinatal outcome (4.3% vs 5.4%; P = .049, with P<.046 prespecified for significance). In addition, the rate of CD was significantly lower in the labor induction group than in the expectant management group (18.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001).

Other significant findings in secondary outcomes included the following:

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were significantly lower in the labor induction group compared with the expectant management group (9.1% vs 14.1%; P<.001).

- The labor induction group had a longer length of stay in the labor and delivery unit but a shorter postpartum hospital stay.

- The labor induction group reported less pain and more control during labor.

Results refute negative notion of elective labor induction

The authors concluded that in a low-risk nulliparous patient population, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks does not increase the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes and decreases the rate of CD and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Additionally, they noted that induction at 39 weeks should not be avoided with the goal of preventing CD, as even women with an unfavorable cervix had a lower rate of CD in the induction group compared with the expectant management group.

After publication of the ARRIVE trial findings, both ACOG and SMFM released statements supporting elective labor induction at or beyond 39 weeks’ gestation in low-risk nulliparous women with good gestational dating.2,3 They cited the following as important issues: adherence to the trial inclusion criteria except for research purposes, shared decision-making with the patient, consideration of the logistics and impact on the health care facility, and the yet unknown impact on cost. Finally, it should be a priority to avoid the primary CD for a failed induction by allowing a longer latent phase of labor, as long as maternal and fetal conditions allow. In my practice, I actively offer induction of labor to most of my patients at 39 weeks after a discussion of the risks and benefits.

Continue to: Immediate pushing in second stage...

Immediate pushing in second stage offers benefits and is preferable to delayed pushing

Cahill AG, Srinivas SK, Tita AT, et al. Effect of immediate vs delayed pushing on rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery among nulliparous women receiving neuraxial analgesia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:1444-1454.

In a randomized trial of 2,414 women, Cahill and colleagues sought to answer a seemingly simple question: What is the best timing for pushing during the second stage of labor--immediate or delayed?

Practical management of the second stage of labor (defined as complete cervical dilation to the delivery of the infant) varies by provider and setting, and previous data on pushing efforts are conflicting. Delayed pushing, or "laboring down," has been suggested to allow passive fetal rotation and to conserve maternal energy for pushing. Older studies have shown that delayed pushing decreases the rate of operative delivery. More recent study data have not demonstrated a difference between immediate and delayed pushing techniques on vaginal delivery rates and have noted that increased maternal and neonatal morbidities are associated with a longer second stage of labor.

The recent trial by Cahill and colleagues was designed to determine the effect of these 2 techniques on spontaneous vaginal delivery rates and on maternal and neonatal morbidities.4

Large study population

This randomized pragmatic trial was conducted at 6 centers in the United States. Study participants (2,404 women completed the study) were nulliparous women at 37 or more weeks' gestation with neuraxial anesthesia who were randomly assigned at complete cervical dilation either to immediate pushing (n = 1,200) or to delayed pushing, that is, instructed to wait 60 minutes before starting to push (n = 1,204). The obstetric provider determined the rest of the labor management.

The primary outcome was the rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery. Secondary outcomes included duration of the second stage of labor, duration of active pushing, operative vaginal delivery, CD, and several maternal assessments (postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, endometritis, and perineal lacerations).

Both groups had similar vaginal delivery rates, differences in some measures

There was no difference in the primary outcome between the 2 groups: The spontaneous vaginal delivery rate was 85.9% (n = 1,031) in the immediate pushing group and 86.5% (n = 1,041) in the delayed pushing group (P = .67).

Analysis of secondary outcomes revealed several significant differences:

- decreased total time for the second stage of labor in the immediate pushing group compared with the delayed pushing group (102.4 vs 134.2 minutes) but longer active pushing time (83.7 vs 74.5 minutes)

- a lower rate of postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis in the second stage, neonatal acidemia, and suspected neonatal sepsis in the immediate pushing group

- a higher rate of third-degree perineal lacerations in the immediate pushing group.

No difference was found between groups in rates of operative vaginal deliveries, CDs, endometritis, overall perineal lacerations, or spontaneous vaginal delivery by fetal station or occiput position.

Authors' takeaway

The authors concluded that since delayed pushing does not increase spontaneous vaginal delivery rates and increases the duration of the second stage of labor and both maternal and neonatal morbidity, immediate pushing may be preferred in this patient population.

After reviewing the available literature in light of this study’s findings, ACOG released a practice advisory in October 2018 stating that “it is reasonable to choose immediate over delayed pushing in nulliparous patients with neuraxial anesthesia.”5 Nulliparous patients with neuraxial anesthesia should be counseled that delayed pushing does not increase the rate of spontaneous vaginal birth and may increase both maternal and neonatal complications. As this may be a practice change for many obstetrics units, the obstetric nursing department should be included in this education and counseling. In my practice, I would recommend immediate pushing, but it is important to include both the patient and her nurse in the discussion.

ACOG aims to optimize postpartum care

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

In May 2018, ACOG released "Optimizing postpartum care," a committee opinion that proposes a new model of comprehensive postpartum care focused on improving both short- and long-term health outcomes for women and infants. (This replaces the June 2016 committee opinion No. 666.) Described as "the fourth trimester," the postpartum period is a critical transitional period in which both pregnancy-related and pre-existing conditions may affect maternal, neonatal, and family status; half of pregnancy-related maternal deaths occur during the postpartum period.6

The postpartum visit: Often a lost opportunity

ACOG cites that up to 40% of women in the United States do not attend their postpartum visit.6 Many aspects of the postpartum visit, including follow-up for chronic diseases, mental health screening, and contraceptive counseling, provide opportunities for acute intervention as well as establishment of healthy behaviors. Some studies have shown that postpartum depression, breastfeeding, and patient satisfaction outcomes improve as a result of postpartum engagement.

Continue to: ACOG's recommendations...

ACOG's recommendations

Ongoing process. ACOG's first proposed change concerns the structure of the postpartum visit itself, which traditionally has been a single visit with a provider at approximately 6 weeks postpartum. Postpartum care plans actually should be started before birth, during regular prenatal care, and adjusted in the hospital as needed so that the provider can educate patients about the issues they may face and resources they may need during this time. This prenatal preparation hopefully will encourage more patients to attend their postpartum visits.

Increased provider contact. Another proposed change is that after delivery, the patient should have contact with a provider within the first 3 weeks postpartum. For high-risk patients, this may involve an in-person clinic visit as soon as 3 to 10 days postpartum (for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy) or at 1 to 2 weeks (for postpartum depression screening, incision checks, and lactation issues). For lower-risk patients, a phone call may be appropriate and/or preferred. Ongoing follow-up for all patients before the final postpartum visit should be individualized.

Postpartum visit and care transition. ACOG recommends a comprehensive postpartum visit at 4 to 12 weeks to fully evaluate the woman's physical, social, and psychologic well-being and to serve as a transition from pregnancy care to well-woman care. This is a large order and includes evaluation of the following:

- mood and emotional well-being

- infant care and feeding

- sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing

- sleep and fatigue

- physical recovery from birth

- chronic disease management and transition to primary care provider

- health maintenance

- review of labor and delivery course if needed

- review of risks and recommendations for future pregnancies.

After these components are addressed, it is expected that the patient will be transitioned to a primary care provider (who may continue to be the ObGyn, as appropriate) to coordinate her future care in the primary medical home.

Useful resource for adopting new paradigm

ACOG's recommendations are somewhat daunting, and these changes will require education and resources, a significant increase in obstetric provider time and effort, and consideration of policy change regarding such issues as parental leave and postpartum care reimbursement. As a start, ACOG has developed an online aid for health care providers called "Postpartum toolkit" (https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Toolkits-for-Health-Care-Providers/Postpartum-Toolkit), which provides education and resources for all steps in the process and can be individualized for each practice and patient.7

Postpartum care should be seen as an ongoing process to address both short- and long-term health outcomes for the patient, her newborn, and their family. This process should begin with planning in the antenatal period, continue with close individualized follow-up within the first 3 weeks of birth, and conclude with a comprehensive postpartum evaluation and transition to well-woman care. Shifting the paradigm of postpartum care will take considerable commitment and resources on the part of obstetric providers and their practices. In my practice, we routinely see hypertensive patients within the first week postpartum and patients at risk for postpartum depression within the first 2 weeks in our clinics. We have a standard 6-week postpartum visit for all patients as well. Going forward, we need to further determine how and when we can implement ACOG’s extensive new recommendations for optimizing postpartum care.

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the ARRIVE trial: Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. August 2018. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-ARRIVE-Trial. Accessed November 25, 2018.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee. SMFM statement on elective induction of labor in low-risk nulliparous women at term: the ARRIVE trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.009. In press.

- Cahill AG, Srinivas SK, Tita AT, et al. Effect of immediate vs delayed pushing on rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery among nulliparous women receiving neuraxial analgesia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:1444-1454.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory: immediate versus delayed pushing in nulliparous women receiving neuraxial analgesia. October 2018. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Immediate-vs-delayed-pushing-in-nulliparous-women-receiving-neuraxial-analgesia. Accessed November 25, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Postpartum toolkit. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Toolkits-for-Health-Care-Providers/Postpartum-Toolkit. Accessed November 25, 2018.

The past year was an exciting one in obstetrics. The landmark ARRIVE trial presented at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine’s (SMFM) annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine contradicted a long-held belief about the safety of elective labor induction. In a large randomized trial, Cahill and colleagues took a controversial but practical clinical question about second-stage labor management and answered it for the practicing obstetrician in the trenches. Finally, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) placed new emphasis on the oft overlooked but increasingly more complicated postpartum period, offering guidance to support improving care for women in this transitional period.

Ultimately, this was the year of the patient, as research, clinical guidelines, and education focused on how to achieve the best in safety and quality of care for delivery planning, the delivery itself, and the so-called fourth trimester.

ARRIVE: Labor induction at 39 weeks reduces CD rate with no difference in perinatal death or serious outcomes

Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

The term "elective induction of labor" has long had a negative connotation because of its association with increased CD rates and adverse perinatal outcomes. This view was based on results from older observational studies that compared outcomes for labor induction with those of spontaneous labor. In more recent observational studies that more appropriately compared labor induction with expectant management, however, elective induction of labor appears to be associated with similar CD rates and perinatal outcomes.

To test the hypothesis that elective induction would have a lower risk for perinatal death or severe neonatal complications than expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women, Grobman and colleagues conducted A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management (ARRIVE).1

Study population, timing of delivery, and trial outcomes

This randomized controlled trial included 6,106 women at 41 US centers in the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Study participants were low-risk nulliparous women with a singleton vertex fetus who were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 39 to 39 4/7 weeks (n = 3,062) or expectant management (n = 3,044) until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks.

"Low risk" was defined as having no maternal or fetal indication for delivery prior to 40 5/7 weeks. Reliable gestational dating was required.

While no specific protocol for induction of labor management was required, there were 2 requests: 1) Cervical ripening was requested for an unfavorable cervix (63% of participants had a modified Bishop score <5), and 2) a duration of at least 12 hours after cervical ripening, rupture of membranes, and use of uterine stimulant was requested before performing a CD for "failed induction" (if medically appropriate).

The primary outcome was a composite of perinatal death or serious neonatal complications. The main secondary outcome was CD.

Potentially game-changing findings

The investigators found that there was no statistically significant difference between the elective induction and expectant management groups for the primary composite perinatal outcome (4.3% vs 5.4%; P = .049, with P<.046 prespecified for significance). In addition, the rate of CD was significantly lower in the labor induction group than in the expectant management group (18.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001).

Other significant findings in secondary outcomes included the following:

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were significantly lower in the labor induction group compared with the expectant management group (9.1% vs 14.1%; P<.001).

- The labor induction group had a longer length of stay in the labor and delivery unit but a shorter postpartum hospital stay.

- The labor induction group reported less pain and more control during labor.

Results refute negative notion of elective labor induction

The authors concluded that in a low-risk nulliparous patient population, elective induction of labor at 39 weeks does not increase the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes and decreases the rate of CD and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Additionally, they noted that induction at 39 weeks should not be avoided with the goal of preventing CD, as even women with an unfavorable cervix had a lower rate of CD in the induction group compared with the expectant management group.

After publication of the ARRIVE trial findings, both ACOG and SMFM released statements supporting elective labor induction at or beyond 39 weeks’ gestation in low-risk nulliparous women with good gestational dating.2,3 They cited the following as important issues: adherence to the trial inclusion criteria except for research purposes, shared decision-making with the patient, consideration of the logistics and impact on the health care facility, and the yet unknown impact on cost. Finally, it should be a priority to avoid the primary CD for a failed induction by allowing a longer latent phase of labor, as long as maternal and fetal conditions allow. In my practice, I actively offer induction of labor to most of my patients at 39 weeks after a discussion of the risks and benefits.

Continue to: Immediate pushing in second stage...

Immediate pushing in second stage offers benefits and is preferable to delayed pushing

Cahill AG, Srinivas SK, Tita AT, et al. Effect of immediate vs delayed pushing on rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery among nulliparous women receiving neuraxial analgesia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:1444-1454.

In a randomized trial of 2,414 women, Cahill and colleagues sought to answer a seemingly simple question: What is the best timing for pushing during the second stage of labor--immediate or delayed?

Practical management of the second stage of labor (defined as complete cervical dilation to the delivery of the infant) varies by provider and setting, and previous data on pushing efforts are conflicting. Delayed pushing, or "laboring down," has been suggested to allow passive fetal rotation and to conserve maternal energy for pushing. Older studies have shown that delayed pushing decreases the rate of operative delivery. More recent study data have not demonstrated a difference between immediate and delayed pushing techniques on vaginal delivery rates and have noted that increased maternal and neonatal morbidities are associated with a longer second stage of labor.

The recent trial by Cahill and colleagues was designed to determine the effect of these 2 techniques on spontaneous vaginal delivery rates and on maternal and neonatal morbidities.4

Large study population

This randomized pragmatic trial was conducted at 6 centers in the United States. Study participants (2,404 women completed the study) were nulliparous women at 37 or more weeks' gestation with neuraxial anesthesia who were randomly assigned at complete cervical dilation either to immediate pushing (n = 1,200) or to delayed pushing, that is, instructed to wait 60 minutes before starting to push (n = 1,204). The obstetric provider determined the rest of the labor management.

The primary outcome was the rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery. Secondary outcomes included duration of the second stage of labor, duration of active pushing, operative vaginal delivery, CD, and several maternal assessments (postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, endometritis, and perineal lacerations).

Both groups had similar vaginal delivery rates, differences in some measures

There was no difference in the primary outcome between the 2 groups: The spontaneous vaginal delivery rate was 85.9% (n = 1,031) in the immediate pushing group and 86.5% (n = 1,041) in the delayed pushing group (P = .67).

Analysis of secondary outcomes revealed several significant differences:

- decreased total time for the second stage of labor in the immediate pushing group compared with the delayed pushing group (102.4 vs 134.2 minutes) but longer active pushing time (83.7 vs 74.5 minutes)

- a lower rate of postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis in the second stage, neonatal acidemia, and suspected neonatal sepsis in the immediate pushing group

- a higher rate of third-degree perineal lacerations in the immediate pushing group.

No difference was found between groups in rates of operative vaginal deliveries, CDs, endometritis, overall perineal lacerations, or spontaneous vaginal delivery by fetal station or occiput position.

Authors' takeaway

The authors concluded that since delayed pushing does not increase spontaneous vaginal delivery rates and increases the duration of the second stage of labor and both maternal and neonatal morbidity, immediate pushing may be preferred in this patient population.

After reviewing the available literature in light of this study’s findings, ACOG released a practice advisory in October 2018 stating that “it is reasonable to choose immediate over delayed pushing in nulliparous patients with neuraxial anesthesia.”5 Nulliparous patients with neuraxial anesthesia should be counseled that delayed pushing does not increase the rate of spontaneous vaginal birth and may increase both maternal and neonatal complications. As this may be a practice change for many obstetrics units, the obstetric nursing department should be included in this education and counseling. In my practice, I would recommend immediate pushing, but it is important to include both the patient and her nurse in the discussion.

ACOG aims to optimize postpartum care

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

In May 2018, ACOG released "Optimizing postpartum care," a committee opinion that proposes a new model of comprehensive postpartum care focused on improving both short- and long-term health outcomes for women and infants. (This replaces the June 2016 committee opinion No. 666.) Described as "the fourth trimester," the postpartum period is a critical transitional period in which both pregnancy-related and pre-existing conditions may affect maternal, neonatal, and family status; half of pregnancy-related maternal deaths occur during the postpartum period.6

The postpartum visit: Often a lost opportunity

ACOG cites that up to 40% of women in the United States do not attend their postpartum visit.6 Many aspects of the postpartum visit, including follow-up for chronic diseases, mental health screening, and contraceptive counseling, provide opportunities for acute intervention as well as establishment of healthy behaviors. Some studies have shown that postpartum depression, breastfeeding, and patient satisfaction outcomes improve as a result of postpartum engagement.

Continue to: ACOG's recommendations...

ACOG's recommendations

Ongoing process. ACOG's first proposed change concerns the structure of the postpartum visit itself, which traditionally has been a single visit with a provider at approximately 6 weeks postpartum. Postpartum care plans actually should be started before birth, during regular prenatal care, and adjusted in the hospital as needed so that the provider can educate patients about the issues they may face and resources they may need during this time. This prenatal preparation hopefully will encourage more patients to attend their postpartum visits.

Increased provider contact. Another proposed change is that after delivery, the patient should have contact with a provider within the first 3 weeks postpartum. For high-risk patients, this may involve an in-person clinic visit as soon as 3 to 10 days postpartum (for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy) or at 1 to 2 weeks (for postpartum depression screening, incision checks, and lactation issues). For lower-risk patients, a phone call may be appropriate and/or preferred. Ongoing follow-up for all patients before the final postpartum visit should be individualized.

Postpartum visit and care transition. ACOG recommends a comprehensive postpartum visit at 4 to 12 weeks to fully evaluate the woman's physical, social, and psychologic well-being and to serve as a transition from pregnancy care to well-woman care. This is a large order and includes evaluation of the following:

- mood and emotional well-being

- infant care and feeding

- sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing

- sleep and fatigue

- physical recovery from birth

- chronic disease management and transition to primary care provider

- health maintenance

- review of labor and delivery course if needed

- review of risks and recommendations for future pregnancies.

After these components are addressed, it is expected that the patient will be transitioned to a primary care provider (who may continue to be the ObGyn, as appropriate) to coordinate her future care in the primary medical home.

Useful resource for adopting new paradigm

ACOG's recommendations are somewhat daunting, and these changes will require education and resources, a significant increase in obstetric provider time and effort, and consideration of policy change regarding such issues as parental leave and postpartum care reimbursement. As a start, ACOG has developed an online aid for health care providers called "Postpartum toolkit" (https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Toolkits-for-Health-Care-Providers/Postpartum-Toolkit), which provides education and resources for all steps in the process and can be individualized for each practice and patient.7

Postpartum care should be seen as an ongoing process to address both short- and long-term health outcomes for the patient, her newborn, and their family. This process should begin with planning in the antenatal period, continue with close individualized follow-up within the first 3 weeks of birth, and conclude with a comprehensive postpartum evaluation and transition to well-woman care. Shifting the paradigm of postpartum care will take considerable commitment and resources on the part of obstetric providers and their practices. In my practice, we routinely see hypertensive patients within the first week postpartum and patients at risk for postpartum depression within the first 2 weeks in our clinics. We have a standard 6-week postpartum visit for all patients as well. Going forward, we need to further determine how and when we can implement ACOG’s extensive new recommendations for optimizing postpartum care.

The past year was an exciting one in obstetrics. The landmark ARRIVE trial presented at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine’s (SMFM) annual meeting and subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine contradicted a long-held belief about the safety of elective labor induction. In a large randomized trial, Cahill and colleagues took a controversial but practical clinical question about second-stage labor management and answered it for the practicing obstetrician in the trenches. Finally, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) placed new emphasis on the oft overlooked but increasingly more complicated postpartum period, offering guidance to support improving care for women in this transitional period.

Ultimately, this was the year of the patient, as research, clinical guidelines, and education focused on how to achieve the best in safety and quality of care for delivery planning, the delivery itself, and the so-called fourth trimester.

ARRIVE: Labor induction at 39 weeks reduces CD rate with no difference in perinatal death or serious outcomes

Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, et al; for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

The term "elective induction of labor" has long had a negative connotation because of its association with increased CD rates and adverse perinatal outcomes. This view was based on results from older observational studies that compared outcomes for labor induction with those of spontaneous labor. In more recent observational studies that more appropriately compared labor induction with expectant management, however, elective induction of labor appears to be associated with similar CD rates and perinatal outcomes.

To test the hypothesis that elective induction would have a lower risk for perinatal death or severe neonatal complications than expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women, Grobman and colleagues conducted A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management (ARRIVE).1

Study population, timing of delivery, and trial outcomes

This randomized controlled trial included 6,106 women at 41 US centers in the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Study participants were low-risk nulliparous women with a singleton vertex fetus who were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 39 to 39 4/7 weeks (n = 3,062) or expectant management (n = 3,044) until 40 5/7 to 42 2/7 weeks.

"Low risk" was defined as having no maternal or fetal indication for delivery prior to 40 5/7 weeks. Reliable gestational dating was required.

While no specific protocol for induction of labor management was required, there were 2 requests: 1) Cervical ripening was requested for an unfavorable cervix (63% of participants had a modified Bishop score <5), and 2) a duration of at least 12 hours after cervical ripening, rupture of membranes, and use of uterine stimulant was requested before performing a CD for "failed induction" (if medically appropriate).

The primary outcome was a composite of perinatal death or serious neonatal complications. The main secondary outcome was CD.

Potentially game-changing findings

The investigators found that there was no statistically significant difference between the elective induction and expectant management groups for the primary composite perinatal outcome (4.3% vs 5.4%; P = .049, with P<.046 prespecified for significance). In addition, the rate of CD was significantly lower in the labor induction group than in the expectant management group (18.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001).

Other significant findings in secondary outcomes included the following:

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were significantly lower in the labor induction group compared with the expectant management group (9.1% vs 14.1%; P<.001).

- The labor induction group had a longer length of stay in the labor and delivery unit but a shorter postpartum hospital stay.

- The labor induction group reported less pain and more control during labor.

Results refute negative notion of elective labor induction