User login

Using telemedicine to improve maternal safety

SAN DIEGO – Utah hospitals reported improved implementation of an obstetrics hemorrhage bundle following a series of teleconferencing sessions.

“There is an increasing body of evidence to support the use of protocols and bundles in obstetrics to improve outcomes for pregnant women and their babies,” Brett D. Einerson, MD, MPH, lead study author, said in an interview. “In Utah and throughout the Mountain West, we face the unique challenge of disseminating information and education on the latest evidence-based treatments to smaller rural hospitals that still need to be prepared for events like severe postpartum hemorrhage but do not have the volume, or sometime the resources, to be adequately prepared.”

“Telehealth allowed us to reach providers who otherwise could not travel the distance to attend frequent training sessions and gave the whole state access to expertise at the region’s large tertiary care hospitals,” Dr. Einerson said. “As far as we know, this is one of the first uses of telehealth as a tool for disseminating patient safety and quality improvement education for health care providers on a statewide scale.”

Dr. Einerson and his associates invited all Utah hospitals to participate in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative, an evidence-based educational program aimed at facilitating implementation of the obstetric hemorrhage bundle. The program involved two in-person training meetings and twice-monthly teleconferencing with expert mentorship over 6 months. In-person sessions consisted of hands-on training and strategy building, while telehealth sessions were led by regional and national leaders in the field of obstetric hemorrhage.

A statewide self-assessment survey of 38 bundle elements was administered before initiation of the project and after completion. The researchers used modified Likert scales to describe participant responses. Means and proportions were compared before and after the training.

Of Utah’s obstetric hospitals, representing every hospital system in the state, 27 (61%) completed the needs-assessment survey, and 15 (34%) participated in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative, which included four bundle domains:

- Recognition and Prevention: Conducting a risk assessment and active management of the Third Stage of labor.

- Response: Creating a checklist and a rapid response team.

- Readiness: Establishing a blood bank, hemorrhage cart, and conducting simulation/team drills.

- Reporting and Learning: Fostering a culture of debriefing, conducting a multidisciplinary review, and measuring outcomes and processes.

Hospitals reported implementation, or progress toward implementation, of significantly more elements of the bundle after the educational program, compared with before the collaborative (a mean of 33.3 vs. 19 bundle elements; P less than 0.001). Hospitals reported increased implementation of elements in all four bundle domains. All participants (100%) reported that teleconferencing sessions were “very helpful,” and 14 (93%) said that they were “very satisfied” with the collaborative.

“Hospitals in the state of Utah generally had the right tools to treat and prevent obstetric hemorrhage but did not have the systems in place to be sure that the tools were used correctly,” Dr. Einerson said. “For instance, 80% of hospitals had access to a cart with supplies for treating bleeding, but less than 15% were systematically measuring blood loss after delivery. What surprised me most, however, was that most hospitals did not track their rates of postpartum bleeding. In my mind, you can’t set goals for treatment until you know how good – or bad – you are doing. Knowing your baseline rate of outcomes can help set goals and measure progress toward achieving them. Before training, less than 50% of Utah hospitals knew their own rate of hemorrhage, but all participating hospitals reported tracking their rates after the intervention.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it did not measure obstetric outcomes. “We are in the process of measuring the effectiveness of our telehealth intervention by monitoring hemorrhage rates and complications over time,” Dr. Einerson said. “This survey of participants in the statewide telehealth bundle program is the first step.”

Dr. Einerson reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Utah hospitals reported improved implementation of an obstetrics hemorrhage bundle following a series of teleconferencing sessions.

“There is an increasing body of evidence to support the use of protocols and bundles in obstetrics to improve outcomes for pregnant women and their babies,” Brett D. Einerson, MD, MPH, lead study author, said in an interview. “In Utah and throughout the Mountain West, we face the unique challenge of disseminating information and education on the latest evidence-based treatments to smaller rural hospitals that still need to be prepared for events like severe postpartum hemorrhage but do not have the volume, or sometime the resources, to be adequately prepared.”

“Telehealth allowed us to reach providers who otherwise could not travel the distance to attend frequent training sessions and gave the whole state access to expertise at the region’s large tertiary care hospitals,” Dr. Einerson said. “As far as we know, this is one of the first uses of telehealth as a tool for disseminating patient safety and quality improvement education for health care providers on a statewide scale.”

Dr. Einerson and his associates invited all Utah hospitals to participate in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative, an evidence-based educational program aimed at facilitating implementation of the obstetric hemorrhage bundle. The program involved two in-person training meetings and twice-monthly teleconferencing with expert mentorship over 6 months. In-person sessions consisted of hands-on training and strategy building, while telehealth sessions were led by regional and national leaders in the field of obstetric hemorrhage.

A statewide self-assessment survey of 38 bundle elements was administered before initiation of the project and after completion. The researchers used modified Likert scales to describe participant responses. Means and proportions were compared before and after the training.

Of Utah’s obstetric hospitals, representing every hospital system in the state, 27 (61%) completed the needs-assessment survey, and 15 (34%) participated in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative, which included four bundle domains:

- Recognition and Prevention: Conducting a risk assessment and active management of the Third Stage of labor.

- Response: Creating a checklist and a rapid response team.

- Readiness: Establishing a blood bank, hemorrhage cart, and conducting simulation/team drills.

- Reporting and Learning: Fostering a culture of debriefing, conducting a multidisciplinary review, and measuring outcomes and processes.

Hospitals reported implementation, or progress toward implementation, of significantly more elements of the bundle after the educational program, compared with before the collaborative (a mean of 33.3 vs. 19 bundle elements; P less than 0.001). Hospitals reported increased implementation of elements in all four bundle domains. All participants (100%) reported that teleconferencing sessions were “very helpful,” and 14 (93%) said that they were “very satisfied” with the collaborative.

“Hospitals in the state of Utah generally had the right tools to treat and prevent obstetric hemorrhage but did not have the systems in place to be sure that the tools were used correctly,” Dr. Einerson said. “For instance, 80% of hospitals had access to a cart with supplies for treating bleeding, but less than 15% were systematically measuring blood loss after delivery. What surprised me most, however, was that most hospitals did not track their rates of postpartum bleeding. In my mind, you can’t set goals for treatment until you know how good – or bad – you are doing. Knowing your baseline rate of outcomes can help set goals and measure progress toward achieving them. Before training, less than 50% of Utah hospitals knew their own rate of hemorrhage, but all participating hospitals reported tracking their rates after the intervention.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it did not measure obstetric outcomes. “We are in the process of measuring the effectiveness of our telehealth intervention by monitoring hemorrhage rates and complications over time,” Dr. Einerson said. “This survey of participants in the statewide telehealth bundle program is the first step.”

Dr. Einerson reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Utah hospitals reported improved implementation of an obstetrics hemorrhage bundle following a series of teleconferencing sessions.

“There is an increasing body of evidence to support the use of protocols and bundles in obstetrics to improve outcomes for pregnant women and their babies,” Brett D. Einerson, MD, MPH, lead study author, said in an interview. “In Utah and throughout the Mountain West, we face the unique challenge of disseminating information and education on the latest evidence-based treatments to smaller rural hospitals that still need to be prepared for events like severe postpartum hemorrhage but do not have the volume, or sometime the resources, to be adequately prepared.”

“Telehealth allowed us to reach providers who otherwise could not travel the distance to attend frequent training sessions and gave the whole state access to expertise at the region’s large tertiary care hospitals,” Dr. Einerson said. “As far as we know, this is one of the first uses of telehealth as a tool for disseminating patient safety and quality improvement education for health care providers on a statewide scale.”

Dr. Einerson and his associates invited all Utah hospitals to participate in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative, an evidence-based educational program aimed at facilitating implementation of the obstetric hemorrhage bundle. The program involved two in-person training meetings and twice-monthly teleconferencing with expert mentorship over 6 months. In-person sessions consisted of hands-on training and strategy building, while telehealth sessions were led by regional and national leaders in the field of obstetric hemorrhage.

A statewide self-assessment survey of 38 bundle elements was administered before initiation of the project and after completion. The researchers used modified Likert scales to describe participant responses. Means and proportions were compared before and after the training.

Of Utah’s obstetric hospitals, representing every hospital system in the state, 27 (61%) completed the needs-assessment survey, and 15 (34%) participated in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative, which included four bundle domains:

- Recognition and Prevention: Conducting a risk assessment and active management of the Third Stage of labor.

- Response: Creating a checklist and a rapid response team.

- Readiness: Establishing a blood bank, hemorrhage cart, and conducting simulation/team drills.

- Reporting and Learning: Fostering a culture of debriefing, conducting a multidisciplinary review, and measuring outcomes and processes.

Hospitals reported implementation, or progress toward implementation, of significantly more elements of the bundle after the educational program, compared with before the collaborative (a mean of 33.3 vs. 19 bundle elements; P less than 0.001). Hospitals reported increased implementation of elements in all four bundle domains. All participants (100%) reported that teleconferencing sessions were “very helpful,” and 14 (93%) said that they were “very satisfied” with the collaborative.

“Hospitals in the state of Utah generally had the right tools to treat and prevent obstetric hemorrhage but did not have the systems in place to be sure that the tools were used correctly,” Dr. Einerson said. “For instance, 80% of hospitals had access to a cart with supplies for treating bleeding, but less than 15% were systematically measuring blood loss after delivery. What surprised me most, however, was that most hospitals did not track their rates of postpartum bleeding. In my mind, you can’t set goals for treatment until you know how good – or bad – you are doing. Knowing your baseline rate of outcomes can help set goals and measure progress toward achieving them. Before training, less than 50% of Utah hospitals knew their own rate of hemorrhage, but all participating hospitals reported tracking their rates after the intervention.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it did not measure obstetric outcomes. “We are in the process of measuring the effectiveness of our telehealth intervention by monitoring hemorrhage rates and complications over time,” Dr. Einerson said. “This survey of participants in the statewide telehealth bundle program is the first step.”

Dr. Einerson reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hospitals reported implementation, or progress toward implementation, of significantly more elements of the bundle after the educational program, compared with before the collaborative (a mean of 33.3 vs. 19 bundle elements; P less than 0.001).

Data source: Results from 15 Utah hospitals that participated in the Obstetric Hemorrhage Collaborative.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

More than one-third of genetic tests misordered, study finds

SAN DIEGO – A review of genetic tests ordered during a 3-month period found that more than one-third were misordered, leading to more than $20,000 in unnecessary health care costs, results from a single-center quality improvement project showed.

“We know there is an ever-expanding number of genetic tests available for clinicians to order, and there is more direct marketing to the patient,” Kathleen Ruzzo, MD, the lead study author, said in an interview prior to the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “It can be difficult to stay on top of that as we have so many different clinical responsibilities.”

Of genetic tests ordered for the 114 patients, 44 (39%) were deemed to be misordered based on published clinical practice guidelines. Of the rest, 24 tests were misordered/not indicated, 8 tests were misordered/false reassurance, and 12 tests were misordered/inadequate.

The costs of ordered genetic testing totaled approximately $75,000, while the cost of recommended testing following the chart review was approximately $54,000, a difference of more than $20,000.

When Dr. Ruzzo shared results of the study with her colleagues at Naval Medical Center San Diego, “I think it opened a lot of people’s eyes … to be more meticulous about [genetic] testing and to ask for help when you need help,” she said. “Having trained individuals, reviewing genetic tests could save money in the health care system more broadly. We could also approve the appropriate testing for the patient.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it “reviewed a very narrow scope of [genetic] tests for a short amount of time, so we think we underestimated the appropriate health care expenditures. Additionally, we didn’t focus on the clinical ramifications of the misordering for patients.”

Study coauthor Monica A. Lutgendorf, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at the medical center, characterized the study findings as “a call to action in general for ob.gyns. to get additional training and resources to handle the ever-expanding number of [genetic] tests,” she said. “I don’t think that this is unique to any specific institution. I think this is part of the new environment of practice that we’re in.”

Physicians can learn more about genetic testing from ACOG and from the Perinatal Quality Foundation, Dr. Lutgendorf said. The study won first prize among oral abstracts presented at the ACOG meeting. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A review of genetic tests ordered during a 3-month period found that more than one-third were misordered, leading to more than $20,000 in unnecessary health care costs, results from a single-center quality improvement project showed.

“We know there is an ever-expanding number of genetic tests available for clinicians to order, and there is more direct marketing to the patient,” Kathleen Ruzzo, MD, the lead study author, said in an interview prior to the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “It can be difficult to stay on top of that as we have so many different clinical responsibilities.”

Of genetic tests ordered for the 114 patients, 44 (39%) were deemed to be misordered based on published clinical practice guidelines. Of the rest, 24 tests were misordered/not indicated, 8 tests were misordered/false reassurance, and 12 tests were misordered/inadequate.

The costs of ordered genetic testing totaled approximately $75,000, while the cost of recommended testing following the chart review was approximately $54,000, a difference of more than $20,000.

When Dr. Ruzzo shared results of the study with her colleagues at Naval Medical Center San Diego, “I think it opened a lot of people’s eyes … to be more meticulous about [genetic] testing and to ask for help when you need help,” she said. “Having trained individuals, reviewing genetic tests could save money in the health care system more broadly. We could also approve the appropriate testing for the patient.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it “reviewed a very narrow scope of [genetic] tests for a short amount of time, so we think we underestimated the appropriate health care expenditures. Additionally, we didn’t focus on the clinical ramifications of the misordering for patients.”

Study coauthor Monica A. Lutgendorf, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at the medical center, characterized the study findings as “a call to action in general for ob.gyns. to get additional training and resources to handle the ever-expanding number of [genetic] tests,” she said. “I don’t think that this is unique to any specific institution. I think this is part of the new environment of practice that we’re in.”

Physicians can learn more about genetic testing from ACOG and from the Perinatal Quality Foundation, Dr. Lutgendorf said. The study won first prize among oral abstracts presented at the ACOG meeting. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A review of genetic tests ordered during a 3-month period found that more than one-third were misordered, leading to more than $20,000 in unnecessary health care costs, results from a single-center quality improvement project showed.

“We know there is an ever-expanding number of genetic tests available for clinicians to order, and there is more direct marketing to the patient,” Kathleen Ruzzo, MD, the lead study author, said in an interview prior to the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “It can be difficult to stay on top of that as we have so many different clinical responsibilities.”

Of genetic tests ordered for the 114 patients, 44 (39%) were deemed to be misordered based on published clinical practice guidelines. Of the rest, 24 tests were misordered/not indicated, 8 tests were misordered/false reassurance, and 12 tests were misordered/inadequate.

The costs of ordered genetic testing totaled approximately $75,000, while the cost of recommended testing following the chart review was approximately $54,000, a difference of more than $20,000.

When Dr. Ruzzo shared results of the study with her colleagues at Naval Medical Center San Diego, “I think it opened a lot of people’s eyes … to be more meticulous about [genetic] testing and to ask for help when you need help,” she said. “Having trained individuals, reviewing genetic tests could save money in the health care system more broadly. We could also approve the appropriate testing for the patient.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it “reviewed a very narrow scope of [genetic] tests for a short amount of time, so we think we underestimated the appropriate health care expenditures. Additionally, we didn’t focus on the clinical ramifications of the misordering for patients.”

Study coauthor Monica A. Lutgendorf, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at the medical center, characterized the study findings as “a call to action in general for ob.gyns. to get additional training and resources to handle the ever-expanding number of [genetic] tests,” she said. “I don’t think that this is unique to any specific institution. I think this is part of the new environment of practice that we’re in.”

Physicians can learn more about genetic testing from ACOG and from the Perinatal Quality Foundation, Dr. Lutgendorf said. The study won first prize among oral abstracts presented at the ACOG meeting. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of genetic tests ordered by clinicians, 39% were deemed to be misordered.

Data source: A review of 114 genetic tests ordered over a 3-month period at a single center.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Should recent evidence of improved outcomes for neonates born during the periviable period change our approach to these deliveries?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Pregnancy management when delivery appears to be imminent at 22 to 26 weeks’ gestation—a window defined as the periviable period—is among the most challenging situations that obstetricians face. Expert guidance exists both at a national level in a shared guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine and, ideally, at a local level where teams of obstetricians and neonatologists have considered in their facility what represents best care

Among the most important yet often missing data points are outcomes of neonates born in the periviable period. Surveys suggest that obstetric care providers often underestimate the chance of survival following periviable delivery.2 Understanding and weighing anticipated outcomes inform decision making regarding management and planned obstetric and neonatal interventions, including plans for neonatal resuscitation.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, survival of periviable neonates has been linked clearly to willingness to undertake resuscitation.3 Yet decisions are not and should not be all about survival. Patients and providers want to know about short- and long-term morbidity, especially neurologic health, among survivors. Available collections of morbidity and mortality data, however, often are limited by whether all cases are captured or just those from specialized centers with particular management approaches, which outcomes are included and how they are defined, and the inevitable reality that the outcome of death “competes” with the outcome of neurologic development (that is, those neonates who die are not at risk for later abnormal neurologic outcome).

Given the need for more and better information, the data from a recent study by Younge and colleagues is especially welcome. The investigators reported on survival and neurologic outcome among more than 4,000 births between 22 and 24 weeks’ gestation at 11 centers in the United States.

Details of the study

The authors compared outcomes among three 3-year epochs between 2000 and 2011 and reported that the rate of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment increased over this period while the rate of survival with such impairment did not change. This argues that the observed overall increase in survival over these 12 years was not simply a tradeoff for life with significant impairment.

Within that overall message, however, the details of the data are important. Survival without neurodevelopmental impairment did improve from epoch 1 to epoch 3, but just from 16% to 20% (95% confidence interval [CI], 18–23; P = .001). Most neonates in the 2008–2011 epoch died (64%; 95% CI, 61–66; P<.001) or were severely impaired (16%; 95% CI, 14–18; P = .29). This led the authors to conclude that “despite improvements over time, the incidence of death, neurodevelopmental impairment, and other adverse outcomes remains high.” Examined separately, outcomes for infants born at 22 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation were very limited and unchanged over the 3 epochs studied, with death rates of 97% to 98% and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment of just 1%. In my own practice I do not encourage neonatal resuscitation, cesarean delivery, or many other interventions at less than 23 weeks’ gestation.

By contrast, the study showed that at 24 0/7 to 24 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the 2008–2011 epoch, 55% of neonates survived and, overall, 32% of infants survived without evidence of neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months of age.

Related Article:

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Study strengths and weaknesses

It is important to note that the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment used in the Younge study included only what many would classify as severe impairment, and survivors in this cohort “without” neurodevelopmental impairment may still have had important neurologic and other health concerns. In addition, the study did not track outcomes of the children at school age or beyond, when other developmental issues may become evident. As well, the study data may not be generalizable, for it included births from just 11 specialized centers, albeit a consortium accounting for 4% to 5% of periviable births in the United States.

Nevertheless, in supporting findings from other US and European analyses, these new data will help inform counseling conversations in the years to come. Such conversations should consider options for resuscitation, palliative care, and, at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, pregnancy termination. In individual cases these and many other decisions will be informed by both specific clinical circumstances—estimated fetal weight, fetal sex, presence of infection, use of antenatal steroids—and, perhaps most important, individual and family values and preferences. Despite these new data, managing periviable gestations will remain a great and important challenge.

--Jeffrey L. Ecker, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 4: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):e157-e169.

- Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Comparison of perceived and actual rates of survival and freedom from handicap in premature infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):432-439.

- Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Unit. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Pregnancy management when delivery appears to be imminent at 22 to 26 weeks’ gestation—a window defined as the periviable period—is among the most challenging situations that obstetricians face. Expert guidance exists both at a national level in a shared guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine and, ideally, at a local level where teams of obstetricians and neonatologists have considered in their facility what represents best care

Among the most important yet often missing data points are outcomes of neonates born in the periviable period. Surveys suggest that obstetric care providers often underestimate the chance of survival following periviable delivery.2 Understanding and weighing anticipated outcomes inform decision making regarding management and planned obstetric and neonatal interventions, including plans for neonatal resuscitation.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, survival of periviable neonates has been linked clearly to willingness to undertake resuscitation.3 Yet decisions are not and should not be all about survival. Patients and providers want to know about short- and long-term morbidity, especially neurologic health, among survivors. Available collections of morbidity and mortality data, however, often are limited by whether all cases are captured or just those from specialized centers with particular management approaches, which outcomes are included and how they are defined, and the inevitable reality that the outcome of death “competes” with the outcome of neurologic development (that is, those neonates who die are not at risk for later abnormal neurologic outcome).

Given the need for more and better information, the data from a recent study by Younge and colleagues is especially welcome. The investigators reported on survival and neurologic outcome among more than 4,000 births between 22 and 24 weeks’ gestation at 11 centers in the United States.

Details of the study

The authors compared outcomes among three 3-year epochs between 2000 and 2011 and reported that the rate of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment increased over this period while the rate of survival with such impairment did not change. This argues that the observed overall increase in survival over these 12 years was not simply a tradeoff for life with significant impairment.

Within that overall message, however, the details of the data are important. Survival without neurodevelopmental impairment did improve from epoch 1 to epoch 3, but just from 16% to 20% (95% confidence interval [CI], 18–23; P = .001). Most neonates in the 2008–2011 epoch died (64%; 95% CI, 61–66; P<.001) or were severely impaired (16%; 95% CI, 14–18; P = .29). This led the authors to conclude that “despite improvements over time, the incidence of death, neurodevelopmental impairment, and other adverse outcomes remains high.” Examined separately, outcomes for infants born at 22 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation were very limited and unchanged over the 3 epochs studied, with death rates of 97% to 98% and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment of just 1%. In my own practice I do not encourage neonatal resuscitation, cesarean delivery, or many other interventions at less than 23 weeks’ gestation.

By contrast, the study showed that at 24 0/7 to 24 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the 2008–2011 epoch, 55% of neonates survived and, overall, 32% of infants survived without evidence of neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months of age.

Related Article:

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Study strengths and weaknesses

It is important to note that the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment used in the Younge study included only what many would classify as severe impairment, and survivors in this cohort “without” neurodevelopmental impairment may still have had important neurologic and other health concerns. In addition, the study did not track outcomes of the children at school age or beyond, when other developmental issues may become evident. As well, the study data may not be generalizable, for it included births from just 11 specialized centers, albeit a consortium accounting for 4% to 5% of periviable births in the United States.

Nevertheless, in supporting findings from other US and European analyses, these new data will help inform counseling conversations in the years to come. Such conversations should consider options for resuscitation, palliative care, and, at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, pregnancy termination. In individual cases these and many other decisions will be informed by both specific clinical circumstances—estimated fetal weight, fetal sex, presence of infection, use of antenatal steroids—and, perhaps most important, individual and family values and preferences. Despite these new data, managing periviable gestations will remain a great and important challenge.

--Jeffrey L. Ecker, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Pregnancy management when delivery appears to be imminent at 22 to 26 weeks’ gestation—a window defined as the periviable period—is among the most challenging situations that obstetricians face. Expert guidance exists both at a national level in a shared guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine and, ideally, at a local level where teams of obstetricians and neonatologists have considered in their facility what represents best care

Among the most important yet often missing data points are outcomes of neonates born in the periviable period. Surveys suggest that obstetric care providers often underestimate the chance of survival following periviable delivery.2 Understanding and weighing anticipated outcomes inform decision making regarding management and planned obstetric and neonatal interventions, including plans for neonatal resuscitation.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, survival of periviable neonates has been linked clearly to willingness to undertake resuscitation.3 Yet decisions are not and should not be all about survival. Patients and providers want to know about short- and long-term morbidity, especially neurologic health, among survivors. Available collections of morbidity and mortality data, however, often are limited by whether all cases are captured or just those from specialized centers with particular management approaches, which outcomes are included and how they are defined, and the inevitable reality that the outcome of death “competes” with the outcome of neurologic development (that is, those neonates who die are not at risk for later abnormal neurologic outcome).

Given the need for more and better information, the data from a recent study by Younge and colleagues is especially welcome. The investigators reported on survival and neurologic outcome among more than 4,000 births between 22 and 24 weeks’ gestation at 11 centers in the United States.

Details of the study

The authors compared outcomes among three 3-year epochs between 2000 and 2011 and reported that the rate of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment increased over this period while the rate of survival with such impairment did not change. This argues that the observed overall increase in survival over these 12 years was not simply a tradeoff for life with significant impairment.

Within that overall message, however, the details of the data are important. Survival without neurodevelopmental impairment did improve from epoch 1 to epoch 3, but just from 16% to 20% (95% confidence interval [CI], 18–23; P = .001). Most neonates in the 2008–2011 epoch died (64%; 95% CI, 61–66; P<.001) or were severely impaired (16%; 95% CI, 14–18; P = .29). This led the authors to conclude that “despite improvements over time, the incidence of death, neurodevelopmental impairment, and other adverse outcomes remains high.” Examined separately, outcomes for infants born at 22 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks’ gestation were very limited and unchanged over the 3 epochs studied, with death rates of 97% to 98% and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment of just 1%. In my own practice I do not encourage neonatal resuscitation, cesarean delivery, or many other interventions at less than 23 weeks’ gestation.

By contrast, the study showed that at 24 0/7 to 24 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the 2008–2011 epoch, 55% of neonates survived and, overall, 32% of infants survived without evidence of neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 22 months of age.

Related Article:

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Study strengths and weaknesses

It is important to note that the definition of neurodevelopmental impairment used in the Younge study included only what many would classify as severe impairment, and survivors in this cohort “without” neurodevelopmental impairment may still have had important neurologic and other health concerns. In addition, the study did not track outcomes of the children at school age or beyond, when other developmental issues may become evident. As well, the study data may not be generalizable, for it included births from just 11 specialized centers, albeit a consortium accounting for 4% to 5% of periviable births in the United States.

Nevertheless, in supporting findings from other US and European analyses, these new data will help inform counseling conversations in the years to come. Such conversations should consider options for resuscitation, palliative care, and, at less than 24 weeks’ gestation, pregnancy termination. In individual cases these and many other decisions will be informed by both specific clinical circumstances—estimated fetal weight, fetal sex, presence of infection, use of antenatal steroids—and, perhaps most important, individual and family values and preferences. Despite these new data, managing periviable gestations will remain a great and important challenge.

--Jeffrey L. Ecker, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 4: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):e157-e169.

- Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Comparison of perceived and actual rates of survival and freedom from handicap in premature infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):432-439.

- Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Unit. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811.

- Obstetric Care Consensus No. 4: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):e157-e169.

- Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Comparison of perceived and actual rates of survival and freedom from handicap in premature infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):432-439.

- Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Unit. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811.

Endometriosis: From Identification to Management

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

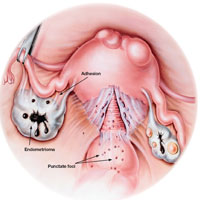

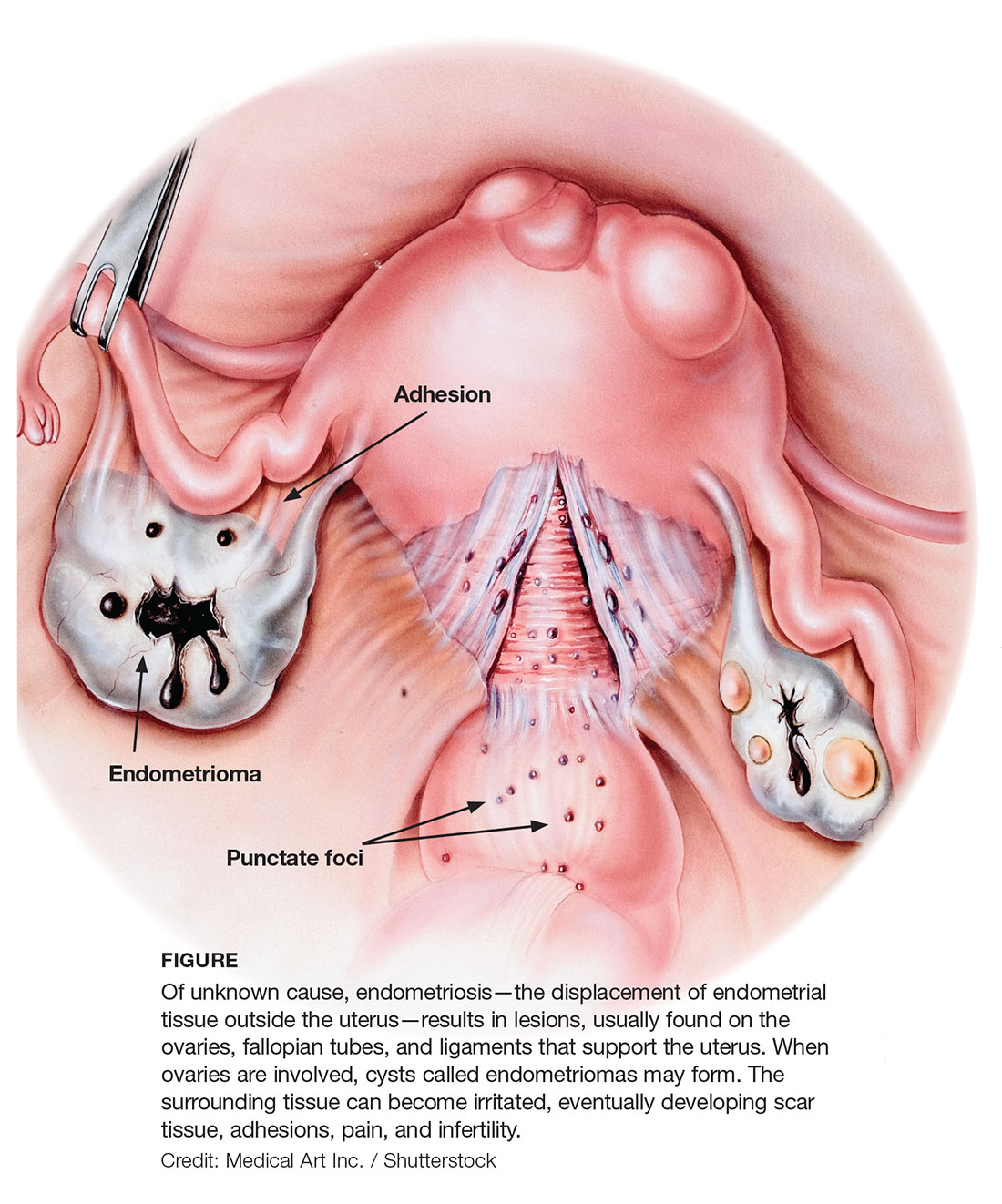

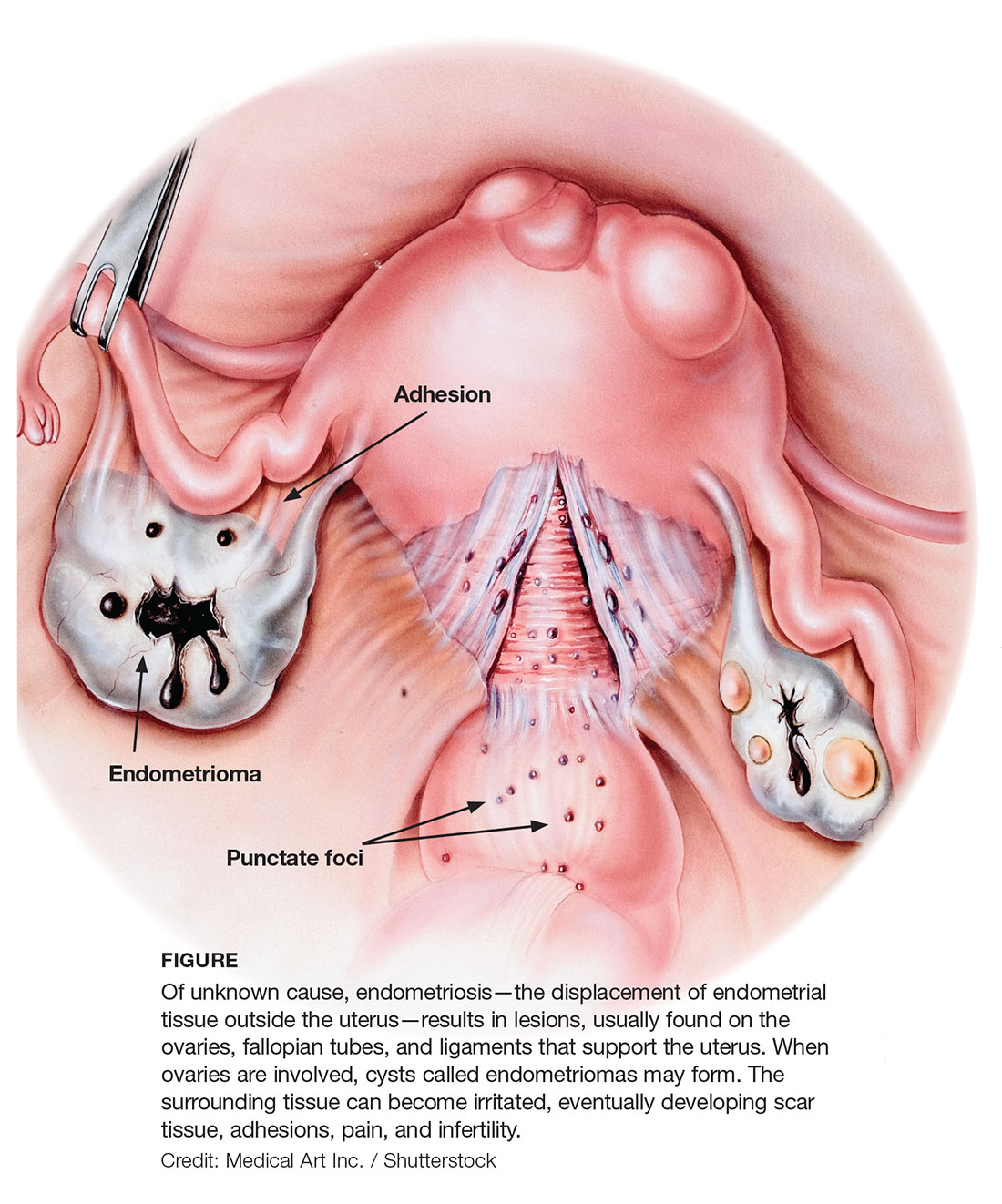

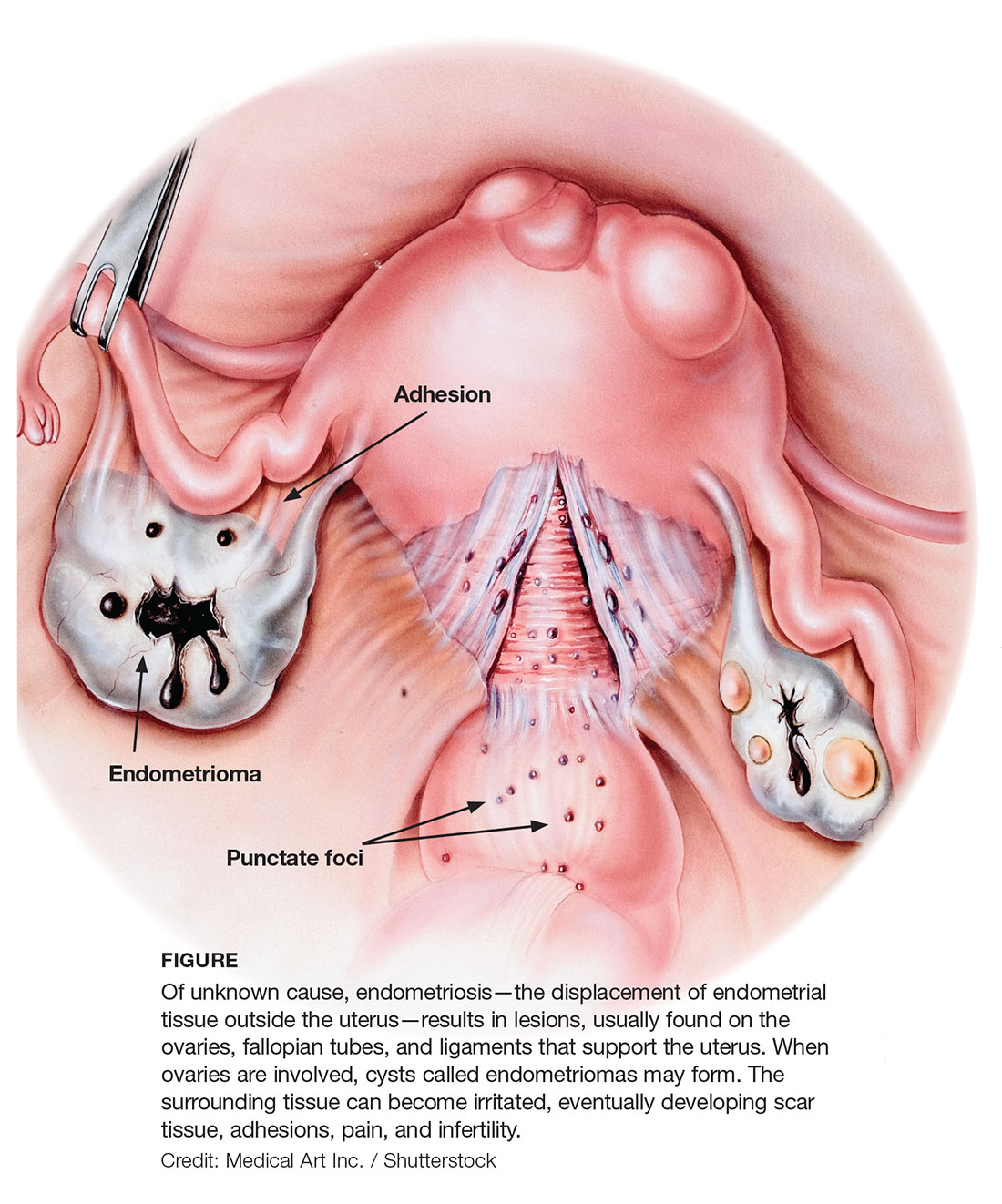

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

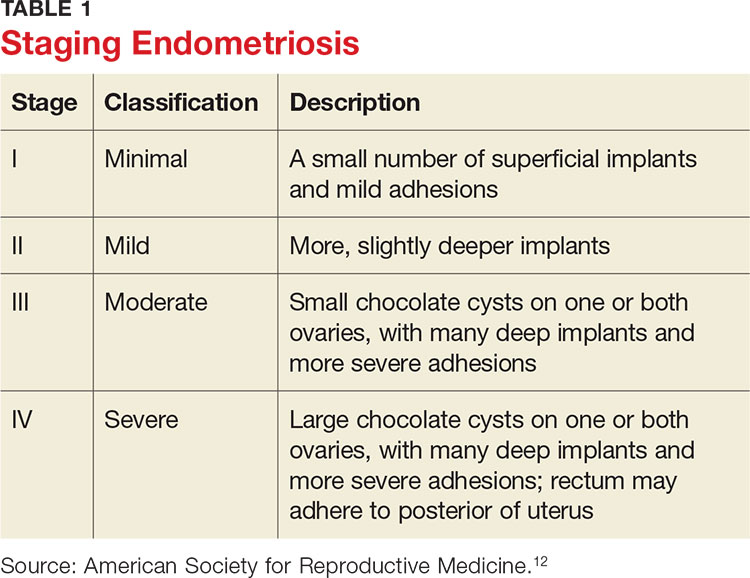

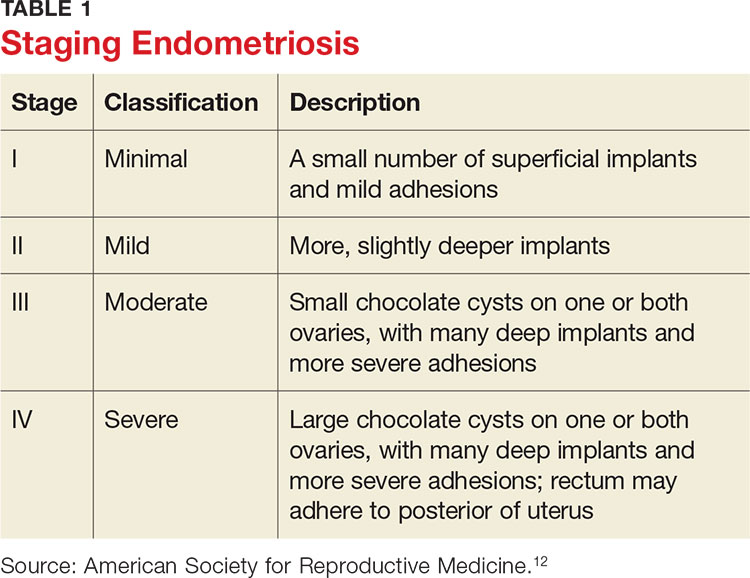

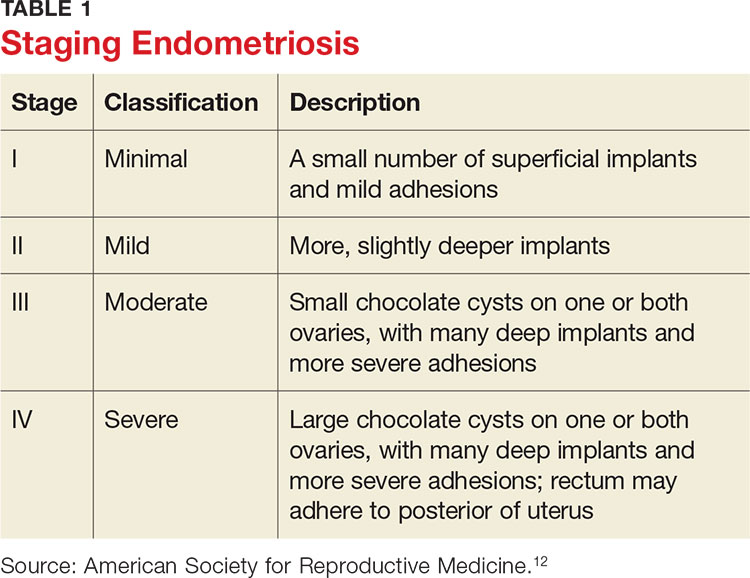

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

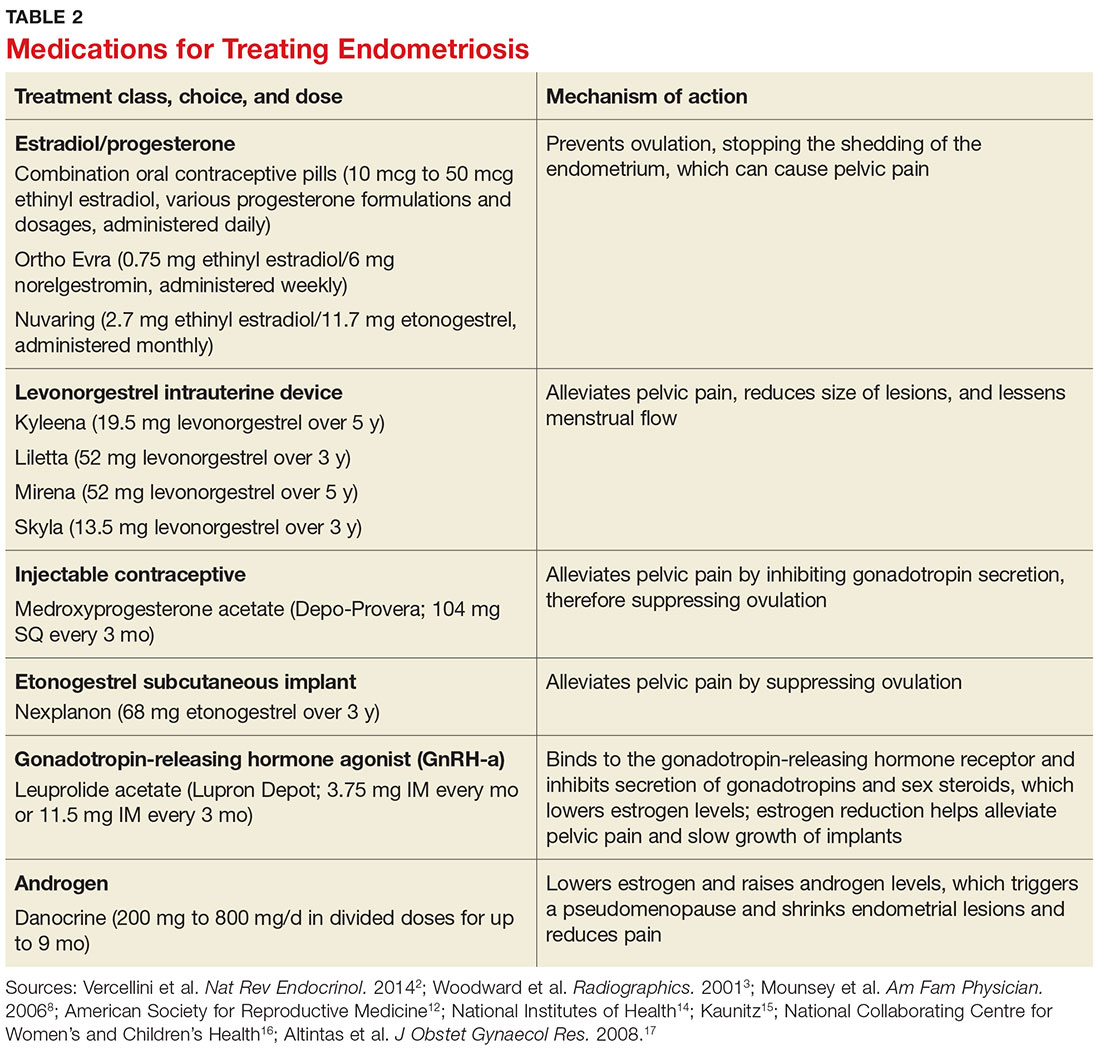

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

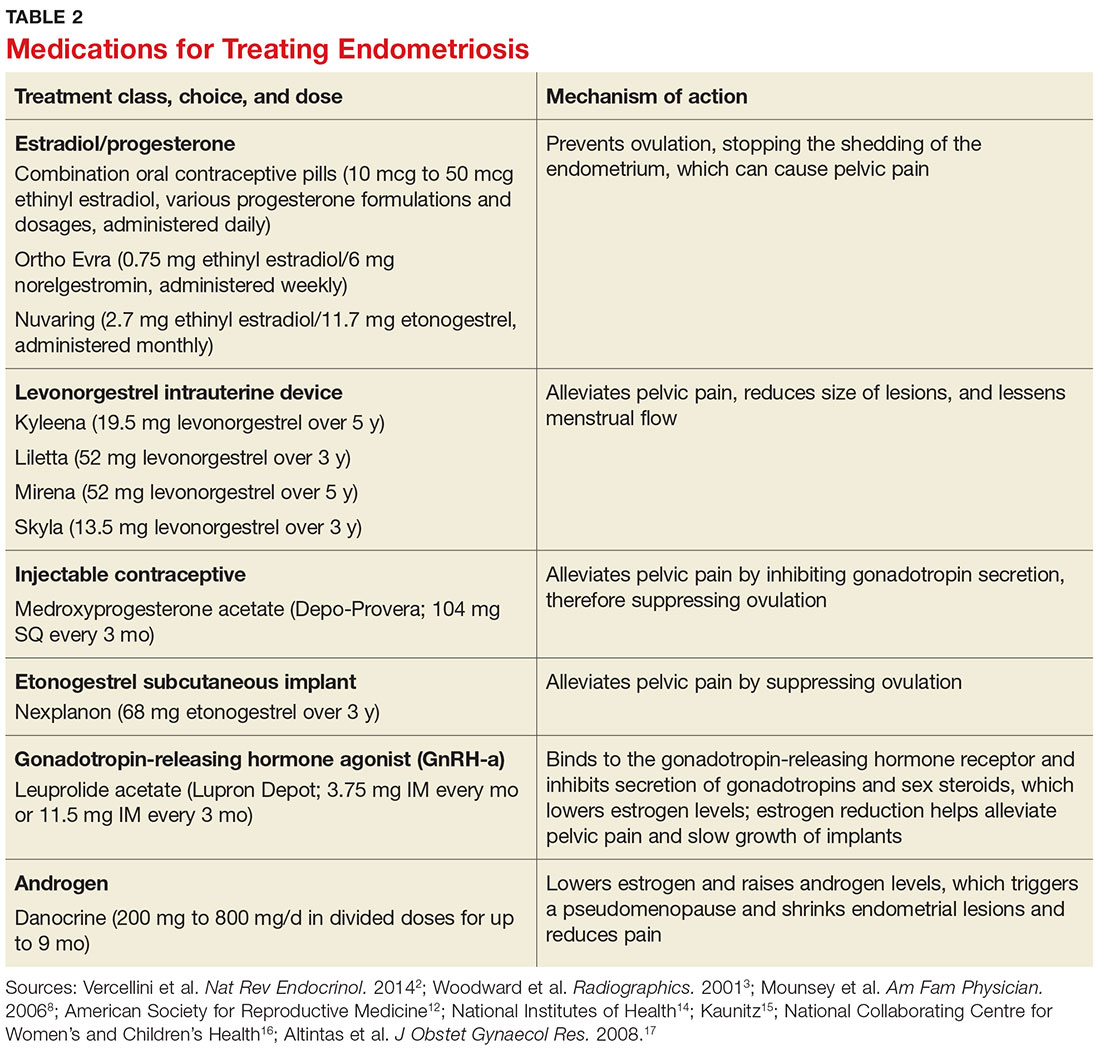

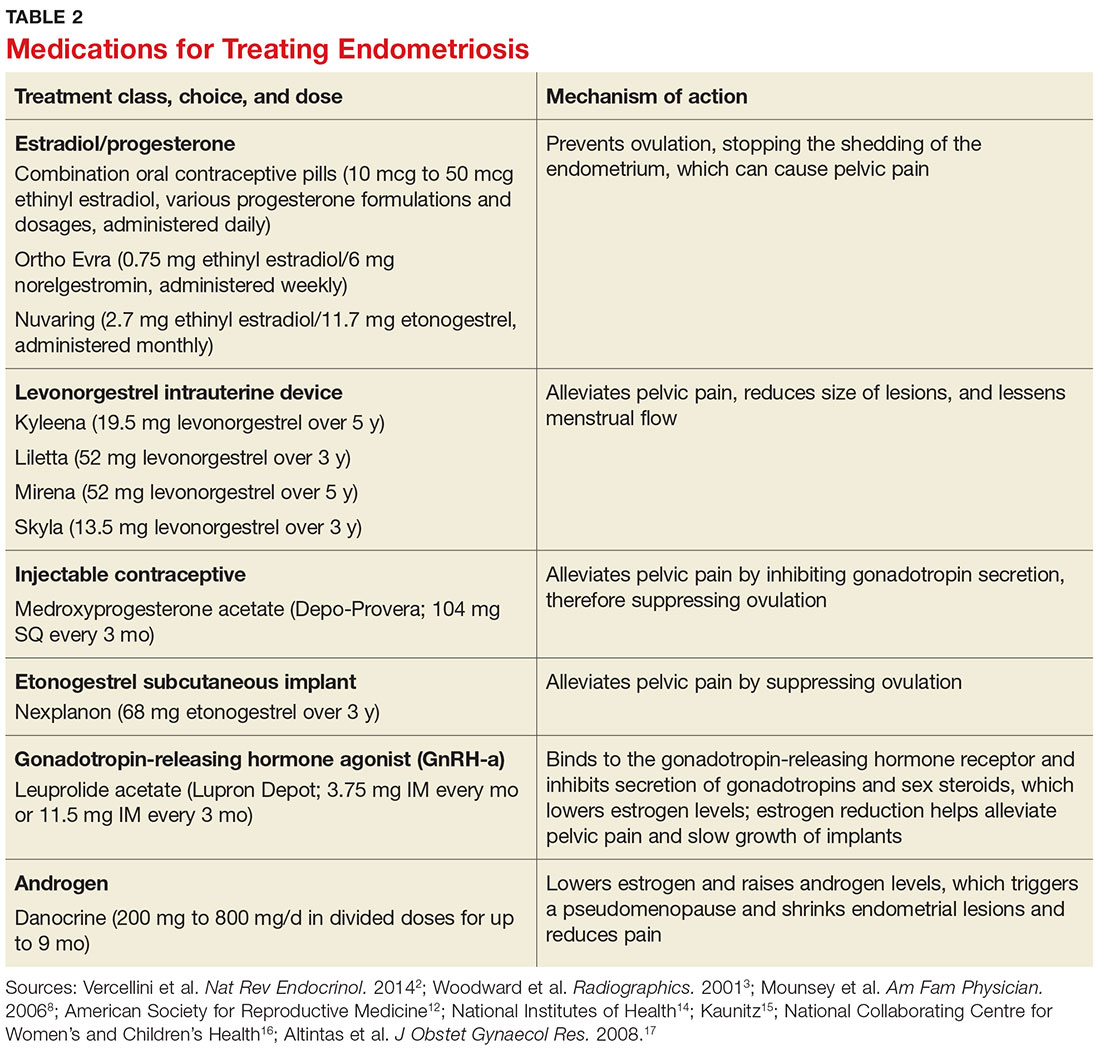

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

1. Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570-582.

2. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10(5):261-275.

3. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193-216.

4. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447.

5. Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Miller C, et al. Pathophysiology and immune dysfunction in endometriosis. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2015:1-12.

6. Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735-1750.

7. Farrell E, Garad R. Clinical update: endometriosis. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(5):37-39.

8. Mounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600.

9. Nouri K, Ott J, Krupitz B, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(85):1-7.

10. Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(39):1-12.

11. Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:1-12.

12. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: a guide for patients. www.conceive.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ASRM-endometriosis.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

13. Angioni S, Cofelice V, Pontis A, et al. New trends of progestins treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014; 30(11):769-773.

14. National Institutes of Health. What are the treatments for endometriosis? www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/Pages/treatment.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2017.

15. Kaunitz AM. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/depot-medroxyprogesterone-acetate-for-contraception. Accessed April 19, 2017.

16. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Long-acting reversible contraception: the effective and appropriate use of long-acting reversible contraception. London, England: RCOG Press; 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51051/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK51051.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

17. Altintas D, Kokcu A, Tosun M, Kandemir B. Comparison of the effects of cetrorelix, a GnRH antagonist, and leuprolide, a GnRH agonist, on experimental endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(6):1014-1019.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

1. Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570-582.

2. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10(5):261-275.

3. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193-216.

4. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447.

5. Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Miller C, et al. Pathophysiology and immune dysfunction in endometriosis. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2015:1-12.

6. Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735-1750.

7. Farrell E, Garad R. Clinical update: endometriosis. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(5):37-39.

8. Mounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600.

9. Nouri K, Ott J, Krupitz B, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(85):1-7.

10. Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(39):1-12.

11. Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:1-12.

12. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: a guide for patients. www.conceive.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ASRM-endometriosis.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

13. Angioni S, Cofelice V, Pontis A, et al. New trends of progestins treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014; 30(11):769-773.

14. National Institutes of Health. What are the treatments for endometriosis? www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/Pages/treatment.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2017.

15. Kaunitz AM. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/depot-medroxyprogesterone-acetate-for-contraception. Accessed April 19, 2017.