User login

ACOG supports evidence-based decisions on planned home birth

Women who are interested in a planned home birth are entitled to make medically informed decisions about where to deliver their babies, according to an updated policy statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

But women should know the risks and benefits of home birth based on the latest evidence. Although planned home birth is associated with fewer maternal interventions than planned hospital birth, there is also a twofold increased risk of perinatal death (1-2 per 1,000 births) and a threefold increased risk of neonatal seizures or other neurologic problems (0.4-0.6 per 1,000 births), according to the statement from ACOG’s Committee on Obstetric Practice, which updates its 2011 policy (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e26-31).

ACOG maintains that hospitals and accredited birth centers are the safest settings for birth, and that unplanned home births are associated with increased rates of perinatal and neonatal mortality. “The relative risk versus benefit of a planned home birth, however, remains the subject of debate,” the committee wrote.

Women considering home birth should attend to several factors to help promote a safe delivery, including being a suitable candidate for home birth; identifying a qualified nurse-midwife, a qualified midwife, or a physician practicing obstetrics who is available for consultation; and preparing for safe, timely transport to a hospital if necessary.

An arrangement with a hospital for transfer is a requirement for women considering a planned home birth, according to the statement. However, the statement advised the hospital and health care team to refrain from judgment should their help be needed.

“When antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum transfer of a woman from home to a hospital occurs, the receiving health care provider should maintain a nonjudgmental demeanor with regard to the woman and those individuals accompanying her to the hospital,” the committee wrote.

Although the current statement supports a woman’s right to make a medically informed decision, it emphasizes that any of several factors including fetal malpresentation, multiple gestation, and prior cesarean delivery are “an absolute contraindication to planned home birth.”

Women who are interested in a planned home birth are entitled to make medically informed decisions about where to deliver their babies, according to an updated policy statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

But women should know the risks and benefits of home birth based on the latest evidence. Although planned home birth is associated with fewer maternal interventions than planned hospital birth, there is also a twofold increased risk of perinatal death (1-2 per 1,000 births) and a threefold increased risk of neonatal seizures or other neurologic problems (0.4-0.6 per 1,000 births), according to the statement from ACOG’s Committee on Obstetric Practice, which updates its 2011 policy (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e26-31).

ACOG maintains that hospitals and accredited birth centers are the safest settings for birth, and that unplanned home births are associated with increased rates of perinatal and neonatal mortality. “The relative risk versus benefit of a planned home birth, however, remains the subject of debate,” the committee wrote.

Women considering home birth should attend to several factors to help promote a safe delivery, including being a suitable candidate for home birth; identifying a qualified nurse-midwife, a qualified midwife, or a physician practicing obstetrics who is available for consultation; and preparing for safe, timely transport to a hospital if necessary.

An arrangement with a hospital for transfer is a requirement for women considering a planned home birth, according to the statement. However, the statement advised the hospital and health care team to refrain from judgment should their help be needed.

“When antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum transfer of a woman from home to a hospital occurs, the receiving health care provider should maintain a nonjudgmental demeanor with regard to the woman and those individuals accompanying her to the hospital,” the committee wrote.

Although the current statement supports a woman’s right to make a medically informed decision, it emphasizes that any of several factors including fetal malpresentation, multiple gestation, and prior cesarean delivery are “an absolute contraindication to planned home birth.”

Women who are interested in a planned home birth are entitled to make medically informed decisions about where to deliver their babies, according to an updated policy statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

But women should know the risks and benefits of home birth based on the latest evidence. Although planned home birth is associated with fewer maternal interventions than planned hospital birth, there is also a twofold increased risk of perinatal death (1-2 per 1,000 births) and a threefold increased risk of neonatal seizures or other neurologic problems (0.4-0.6 per 1,000 births), according to the statement from ACOG’s Committee on Obstetric Practice, which updates its 2011 policy (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e26-31).

ACOG maintains that hospitals and accredited birth centers are the safest settings for birth, and that unplanned home births are associated with increased rates of perinatal and neonatal mortality. “The relative risk versus benefit of a planned home birth, however, remains the subject of debate,” the committee wrote.

Women considering home birth should attend to several factors to help promote a safe delivery, including being a suitable candidate for home birth; identifying a qualified nurse-midwife, a qualified midwife, or a physician practicing obstetrics who is available for consultation; and preparing for safe, timely transport to a hospital if necessary.

An arrangement with a hospital for transfer is a requirement for women considering a planned home birth, according to the statement. However, the statement advised the hospital and health care team to refrain from judgment should their help be needed.

“When antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum transfer of a woman from home to a hospital occurs, the receiving health care provider should maintain a nonjudgmental demeanor with regard to the woman and those individuals accompanying her to the hospital,” the committee wrote.

Although the current statement supports a woman’s right to make a medically informed decision, it emphasizes that any of several factors including fetal malpresentation, multiple gestation, and prior cesarean delivery are “an absolute contraindication to planned home birth.”

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

CDC Updates Zika Guidance for Managing Pregnant Women

Updated guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline how to diagnose suspected cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women based on how quickly they present with symptoms.

The guidance was updated in light of “the emerging data indicating that Zika virus RNA can be detected for prolonged periods in some pregnant women,” the CDC wrote in the July 25 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1).

All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika virus at each of their prenatal care visits, regardless of their recent travel history or exposure to mosquitoes, by being evaluated for signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, rash, and arthralgia. From there, management can take one of two directions.

The first direction involves women who are tested within 2 weeks of either symptom onset, or their suspected exposure to the virus. Pregnant women who are asymptomatic and do not live in an area with an ongoing Zika virus outbreak, as well as women who are symptomatic, should have their serum and urine analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. If the result of this test is positive, it should be considered as confirmation that the woman has a “recent Zika virus infection.”

However, if the test results are negative, symptomatic women should undergo immunoglobin M testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus, while asymptomatic women should undergo just Zika virus IgM testing within 2-12 weeks of the possible exposure. In either case, if the tests come back negative, then the patient can be definitively cleared of any recent Zika virus infection. However, if either the Zika virus or dengue virus tests are positive or equivocal, then there is a “presumptive recent Zika virus or dengue virus or Flavivirus infection” in the woman, at which point plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) must be conducted.

The second direction for management involves pregnant women who are initially tested within 2-12 weeks of either symptom onset or suspected exposure to the virus. Asymptomatic women who do not live in an area with active Zika virus transmission, or do live in an area with ongoing Zika virus cases but are already in the first or second trimester of their pregnancy – along with any women who are symptomatic – should have their serum analyzed through IgM testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus.

If both results are negative, then there is no Zika virus infection. If the Zika virus test is negative but the dengue virus test is either positive or equivocal, the woman has a “presumptive dengue virus infection” and should undergo PRNT. If the Zika virus test is either positive or equivocal, then the woman has a “presumptive recent Zika virus or Flavivirus infection,” regardless of the dengue virus IgM result. In the latter case, the next step is to conduct a reflex Zika virus rRT-PCR test on both serum and urine. A negative result on the serum test should be followed by PRNT; a positive result should be taken as proof of a “recent Zika virus infection.”

For any diagnostic chain that ends with a PRNT, the results of that test can be interpreted in one of three ways. If the Zika virus PRNT result is at least 10 and the dengue virus result is less than 10, then there is a recent Zika virus infection. If both the Zika virus and dengue virus PRNT results are 10 or greater, than there is a Flavivirus infection, but the specific one cannot be determined. Finally, if both results are less than 10, then there is no evidence of a recent Zika virus infection.

“For symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered,” the CDC wrote. “If fetal abnormalities are present, rRT-PCR testing should also be performed on maternal serum and urine [but] a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection.”

For pregnant women with a diagnosis of a confirmed or presumptive Flavivirus infection, regardless of whether it’s specifically Zika virus or not, the CDC recommends getting serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks during pregnancy in order to monitor the fetus’s development, while “decisions regarding amniocentesis should be individualized for each clinical circumstance.” After the child’s birth, rRT-PCR should be conducted on the child’s cord blood and serum; Zika virus and dengue virus IgM are also recommended.

Pregnant women without a diagnosis of either Zika virus or dengue virus should have a prenatal ultrasound; if abnormalities are found in the fetus, CDC recommends that they have a repeat Zika virus rRT-PCR and IgM test and that clinicians base management on corresponding laboratory results. If nothing is found, however, then standard care can resume with ongoing vigilance to avoid Zika virus infections. Women with dengue virus diagnoses should follow the guidance that is currently in place.

“Pregnant women with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection who experience a fetal loss or stillbirth should be offered pathology testing for Zika virus infection,” the CDC added. “This testing might provide insight into the etiology of the fetal loss, which could inform a woman’s future pregnancy planning.”

The CDC also issued updated guidance for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and that applies to all men and women who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their sex partners (MMWR. ePub: 2016 25 Jul. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e2). The CDC advises couples in which a woman is pregnant to use barriers methods or abstain from sex for the duration of the pregnancy. For couples not planning pregnancy and in which there is a male partner with confirmed Zika virus infection or symptoms of infection, the men should use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after the onset of illness. For women with Zika virus infection, they should use barrier protection or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after the onset of illness.

Updated guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline how to diagnose suspected cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women based on how quickly they present with symptoms.

The guidance was updated in light of “the emerging data indicating that Zika virus RNA can be detected for prolonged periods in some pregnant women,” the CDC wrote in the July 25 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1).

All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika virus at each of their prenatal care visits, regardless of their recent travel history or exposure to mosquitoes, by being evaluated for signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, rash, and arthralgia. From there, management can take one of two directions.

The first direction involves women who are tested within 2 weeks of either symptom onset, or their suspected exposure to the virus. Pregnant women who are asymptomatic and do not live in an area with an ongoing Zika virus outbreak, as well as women who are symptomatic, should have their serum and urine analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. If the result of this test is positive, it should be considered as confirmation that the woman has a “recent Zika virus infection.”

However, if the test results are negative, symptomatic women should undergo immunoglobin M testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus, while asymptomatic women should undergo just Zika virus IgM testing within 2-12 weeks of the possible exposure. In either case, if the tests come back negative, then the patient can be definitively cleared of any recent Zika virus infection. However, if either the Zika virus or dengue virus tests are positive or equivocal, then there is a “presumptive recent Zika virus or dengue virus or Flavivirus infection” in the woman, at which point plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) must be conducted.

The second direction for management involves pregnant women who are initially tested within 2-12 weeks of either symptom onset or suspected exposure to the virus. Asymptomatic women who do not live in an area with active Zika virus transmission, or do live in an area with ongoing Zika virus cases but are already in the first or second trimester of their pregnancy – along with any women who are symptomatic – should have their serum analyzed through IgM testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus.

If both results are negative, then there is no Zika virus infection. If the Zika virus test is negative but the dengue virus test is either positive or equivocal, the woman has a “presumptive dengue virus infection” and should undergo PRNT. If the Zika virus test is either positive or equivocal, then the woman has a “presumptive recent Zika virus or Flavivirus infection,” regardless of the dengue virus IgM result. In the latter case, the next step is to conduct a reflex Zika virus rRT-PCR test on both serum and urine. A negative result on the serum test should be followed by PRNT; a positive result should be taken as proof of a “recent Zika virus infection.”

For any diagnostic chain that ends with a PRNT, the results of that test can be interpreted in one of three ways. If the Zika virus PRNT result is at least 10 and the dengue virus result is less than 10, then there is a recent Zika virus infection. If both the Zika virus and dengue virus PRNT results are 10 or greater, than there is a Flavivirus infection, but the specific one cannot be determined. Finally, if both results are less than 10, then there is no evidence of a recent Zika virus infection.

“For symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered,” the CDC wrote. “If fetal abnormalities are present, rRT-PCR testing should also be performed on maternal serum and urine [but] a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection.”

For pregnant women with a diagnosis of a confirmed or presumptive Flavivirus infection, regardless of whether it’s specifically Zika virus or not, the CDC recommends getting serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks during pregnancy in order to monitor the fetus’s development, while “decisions regarding amniocentesis should be individualized for each clinical circumstance.” After the child’s birth, rRT-PCR should be conducted on the child’s cord blood and serum; Zika virus and dengue virus IgM are also recommended.

Pregnant women without a diagnosis of either Zika virus or dengue virus should have a prenatal ultrasound; if abnormalities are found in the fetus, CDC recommends that they have a repeat Zika virus rRT-PCR and IgM test and that clinicians base management on corresponding laboratory results. If nothing is found, however, then standard care can resume with ongoing vigilance to avoid Zika virus infections. Women with dengue virus diagnoses should follow the guidance that is currently in place.

“Pregnant women with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection who experience a fetal loss or stillbirth should be offered pathology testing for Zika virus infection,” the CDC added. “This testing might provide insight into the etiology of the fetal loss, which could inform a woman’s future pregnancy planning.”

The CDC also issued updated guidance for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and that applies to all men and women who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their sex partners (MMWR. ePub: 2016 25 Jul. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e2). The CDC advises couples in which a woman is pregnant to use barriers methods or abstain from sex for the duration of the pregnancy. For couples not planning pregnancy and in which there is a male partner with confirmed Zika virus infection or symptoms of infection, the men should use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after the onset of illness. For women with Zika virus infection, they should use barrier protection or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after the onset of illness.

Updated guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline how to diagnose suspected cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women based on how quickly they present with symptoms.

The guidance was updated in light of “the emerging data indicating that Zika virus RNA can be detected for prolonged periods in some pregnant women,” the CDC wrote in the July 25 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1).

All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika virus at each of their prenatal care visits, regardless of their recent travel history or exposure to mosquitoes, by being evaluated for signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, rash, and arthralgia. From there, management can take one of two directions.

The first direction involves women who are tested within 2 weeks of either symptom onset, or their suspected exposure to the virus. Pregnant women who are asymptomatic and do not live in an area with an ongoing Zika virus outbreak, as well as women who are symptomatic, should have their serum and urine analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. If the result of this test is positive, it should be considered as confirmation that the woman has a “recent Zika virus infection.”

However, if the test results are negative, symptomatic women should undergo immunoglobin M testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus, while asymptomatic women should undergo just Zika virus IgM testing within 2-12 weeks of the possible exposure. In either case, if the tests come back negative, then the patient can be definitively cleared of any recent Zika virus infection. However, if either the Zika virus or dengue virus tests are positive or equivocal, then there is a “presumptive recent Zika virus or dengue virus or Flavivirus infection” in the woman, at which point plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) must be conducted.

The second direction for management involves pregnant women who are initially tested within 2-12 weeks of either symptom onset or suspected exposure to the virus. Asymptomatic women who do not live in an area with active Zika virus transmission, or do live in an area with ongoing Zika virus cases but are already in the first or second trimester of their pregnancy – along with any women who are symptomatic – should have their serum analyzed through IgM testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus.

If both results are negative, then there is no Zika virus infection. If the Zika virus test is negative but the dengue virus test is either positive or equivocal, the woman has a “presumptive dengue virus infection” and should undergo PRNT. If the Zika virus test is either positive or equivocal, then the woman has a “presumptive recent Zika virus or Flavivirus infection,” regardless of the dengue virus IgM result. In the latter case, the next step is to conduct a reflex Zika virus rRT-PCR test on both serum and urine. A negative result on the serum test should be followed by PRNT; a positive result should be taken as proof of a “recent Zika virus infection.”

For any diagnostic chain that ends with a PRNT, the results of that test can be interpreted in one of three ways. If the Zika virus PRNT result is at least 10 and the dengue virus result is less than 10, then there is a recent Zika virus infection. If both the Zika virus and dengue virus PRNT results are 10 or greater, than there is a Flavivirus infection, but the specific one cannot be determined. Finally, if both results are less than 10, then there is no evidence of a recent Zika virus infection.

“For symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered,” the CDC wrote. “If fetal abnormalities are present, rRT-PCR testing should also be performed on maternal serum and urine [but] a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection.”

For pregnant women with a diagnosis of a confirmed or presumptive Flavivirus infection, regardless of whether it’s specifically Zika virus or not, the CDC recommends getting serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks during pregnancy in order to monitor the fetus’s development, while “decisions regarding amniocentesis should be individualized for each clinical circumstance.” After the child’s birth, rRT-PCR should be conducted on the child’s cord blood and serum; Zika virus and dengue virus IgM are also recommended.

Pregnant women without a diagnosis of either Zika virus or dengue virus should have a prenatal ultrasound; if abnormalities are found in the fetus, CDC recommends that they have a repeat Zika virus rRT-PCR and IgM test and that clinicians base management on corresponding laboratory results. If nothing is found, however, then standard care can resume with ongoing vigilance to avoid Zika virus infections. Women with dengue virus diagnoses should follow the guidance that is currently in place.

“Pregnant women with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection who experience a fetal loss or stillbirth should be offered pathology testing for Zika virus infection,” the CDC added. “This testing might provide insight into the etiology of the fetal loss, which could inform a woman’s future pregnancy planning.”

The CDC also issued updated guidance for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and that applies to all men and women who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their sex partners (MMWR. ePub: 2016 25 Jul. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e2). The CDC advises couples in which a woman is pregnant to use barriers methods or abstain from sex for the duration of the pregnancy. For couples not planning pregnancy and in which there is a male partner with confirmed Zika virus infection or symptoms of infection, the men should use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after the onset of illness. For women with Zika virus infection, they should use barrier protection or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after the onset of illness.

FROM MMWR

CDC updates Zika guidance for managing pregnant women

Updated guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline how to diagnose suspected cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women based on how quickly they present with symptoms.

The guidance was updated in light of “the emerging data indicating that Zika virus RNA can be detected for prolonged periods in some pregnant women,” the CDC wrote in the July 25 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1).

All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika virus at each of their prenatal care visits, regardless of their recent travel history or exposure to mosquitoes, by being evaluated for signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, rash, and arthralgia. From there, management can take one of two directions.

The first direction involves women who are tested within 2 weeks of either symptom onset, or their suspected exposure to the virus. Pregnant women who are asymptomatic and do not live in an area with an ongoing Zika virus outbreak, as well as women who are symptomatic, should have their serum and urine analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. If the result of this test is positive, it should be considered as confirmation that the woman has a “recent Zika virus infection.”

However, if the test results are negative, symptomatic women should undergo immunoglobin M testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus, while asymptomatic women should undergo just Zika virus IgM testing within 2-12 weeks of the possible exposure. In either case, if the tests come back negative, then the patient can be definitively cleared of any recent Zika virus infection. However, if either the Zika virus or dengue virus tests are positive or equivocal, then there is a “presumptive recent Zika virus or dengue virus or Flavivirus infection” in the woman, at which point plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) must be conducted.

The second direction for management involves pregnant women who are initially tested within 2-12 weeks of either symptom onset or suspected exposure to the virus. Asymptomatic women who do not live in an area with active Zika virus transmission, or do live in an area with ongoing Zika virus cases but are already in the first or second trimester of their pregnancy – along with any women who are symptomatic – should have their serum analyzed through IgM testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus.

If both results are negative, then there is no Zika virus infection. If the Zika virus test is negative but the dengue virus test is either positive or equivocal, the woman has a “presumptive dengue virus infection” and should undergo PRNT. If the Zika virus test is either positive or equivocal, then the woman has a “presumptive recent Zika virus or Flavivirus infection,” regardless of the dengue virus IgM result. In the latter case, the next step is to conduct a reflex Zika virus rRT-PCR test on both serum and urine. A negative result on the serum test should be followed by PRNT; a positive result should be taken as proof of a “recent Zika virus infection.”

For any diagnostic chain that ends with a PRNT, the results of that test can be interpreted in one of three ways. If the Zika virus PRNT result is at least 10 and the dengue virus result is less than 10, then there is a recent Zika virus infection. If both the Zika virus and dengue virus PRNT results are 10 or greater, than there is a Flavivirus infection, but the specific one cannot be determined. Finally, if both results are less than 10, then there is no evidence of a recent Zika virus infection.

“For symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered,” the CDC wrote. “If fetal abnormalities are present, rRT-PCR testing should also be performed on maternal serum and urine [but] a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection.”

For pregnant women with a diagnosis of a confirmed or presumptive Flavivirus infection, regardless of whether it’s specifically Zika virus or not, the CDC recommends getting serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks during pregnancy in order to monitor the fetus’s development, while “decisions regarding amniocentesis should be individualized for each clinical circumstance.” After the child’s birth, rRT-PCR should be conducted on the child’s cord blood and serum; Zika virus and dengue virus IgM are also recommended.

Pregnant women without a diagnosis of either Zika virus or dengue virus should have a prenatal ultrasound; if abnormalities are found in the fetus, CDC recommends that they have a repeat Zika virus rRT-PCR and IgM test and that clinicians base management on corresponding laboratory results. If nothing is found, however, then standard care can resume with ongoing vigilance to avoid Zika virus infections. Women with dengue virus diagnoses should follow the guidance that is currently in place.

“Pregnant women with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection who experience a fetal loss or stillbirth should be offered pathology testing for Zika virus infection,” the CDC added. “This testing might provide insight into the etiology of the fetal loss, which could inform a woman’s future pregnancy planning.”

The CDC also issued updated guidance for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and that applies to all men and women who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their sex partners (MMWR. ePub: 2016 25 Jul. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e2). The CDC advises couples in which a woman is pregnant to use barriers methods or abstain from sex for the duration of the pregnancy. For couples not planning pregnancy and in which there is a male partner with confirmed Zika virus infection or symptoms of infection, the men should use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after the onset of illness. For women with Zika virus infection, they should use barrier protection or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after the onset of illness.

Updated guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline how to diagnose suspected cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women based on how quickly they present with symptoms.

The guidance was updated in light of “the emerging data indicating that Zika virus RNA can be detected for prolonged periods in some pregnant women,” the CDC wrote in the July 25 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1).

All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika virus at each of their prenatal care visits, regardless of their recent travel history or exposure to mosquitoes, by being evaluated for signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, rash, and arthralgia. From there, management can take one of two directions.

The first direction involves women who are tested within 2 weeks of either symptom onset, or their suspected exposure to the virus. Pregnant women who are asymptomatic and do not live in an area with an ongoing Zika virus outbreak, as well as women who are symptomatic, should have their serum and urine analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. If the result of this test is positive, it should be considered as confirmation that the woman has a “recent Zika virus infection.”

However, if the test results are negative, symptomatic women should undergo immunoglobin M testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus, while asymptomatic women should undergo just Zika virus IgM testing within 2-12 weeks of the possible exposure. In either case, if the tests come back negative, then the patient can be definitively cleared of any recent Zika virus infection. However, if either the Zika virus or dengue virus tests are positive or equivocal, then there is a “presumptive recent Zika virus or dengue virus or Flavivirus infection” in the woman, at which point plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) must be conducted.

The second direction for management involves pregnant women who are initially tested within 2-12 weeks of either symptom onset or suspected exposure to the virus. Asymptomatic women who do not live in an area with active Zika virus transmission, or do live in an area with ongoing Zika virus cases but are already in the first or second trimester of their pregnancy – along with any women who are symptomatic – should have their serum analyzed through IgM testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus.

If both results are negative, then there is no Zika virus infection. If the Zika virus test is negative but the dengue virus test is either positive or equivocal, the woman has a “presumptive dengue virus infection” and should undergo PRNT. If the Zika virus test is either positive or equivocal, then the woman has a “presumptive recent Zika virus or Flavivirus infection,” regardless of the dengue virus IgM result. In the latter case, the next step is to conduct a reflex Zika virus rRT-PCR test on both serum and urine. A negative result on the serum test should be followed by PRNT; a positive result should be taken as proof of a “recent Zika virus infection.”

For any diagnostic chain that ends with a PRNT, the results of that test can be interpreted in one of three ways. If the Zika virus PRNT result is at least 10 and the dengue virus result is less than 10, then there is a recent Zika virus infection. If both the Zika virus and dengue virus PRNT results are 10 or greater, than there is a Flavivirus infection, but the specific one cannot be determined. Finally, if both results are less than 10, then there is no evidence of a recent Zika virus infection.

“For symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered,” the CDC wrote. “If fetal abnormalities are present, rRT-PCR testing should also be performed on maternal serum and urine [but] a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection.”

For pregnant women with a diagnosis of a confirmed or presumptive Flavivirus infection, regardless of whether it’s specifically Zika virus or not, the CDC recommends getting serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks during pregnancy in order to monitor the fetus’s development, while “decisions regarding amniocentesis should be individualized for each clinical circumstance.” After the child’s birth, rRT-PCR should be conducted on the child’s cord blood and serum; Zika virus and dengue virus IgM are also recommended.

Pregnant women without a diagnosis of either Zika virus or dengue virus should have a prenatal ultrasound; if abnormalities are found in the fetus, CDC recommends that they have a repeat Zika virus rRT-PCR and IgM test and that clinicians base management on corresponding laboratory results. If nothing is found, however, then standard care can resume with ongoing vigilance to avoid Zika virus infections. Women with dengue virus diagnoses should follow the guidance that is currently in place.

“Pregnant women with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection who experience a fetal loss or stillbirth should be offered pathology testing for Zika virus infection,” the CDC added. “This testing might provide insight into the etiology of the fetal loss, which could inform a woman’s future pregnancy planning.”

The CDC also issued updated guidance for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and that applies to all men and women who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their sex partners (MMWR. ePub: 2016 25 Jul. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e2). The CDC advises couples in which a woman is pregnant to use barriers methods or abstain from sex for the duration of the pregnancy. For couples not planning pregnancy and in which there is a male partner with confirmed Zika virus infection or symptoms of infection, the men should use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after the onset of illness. For women with Zika virus infection, they should use barrier protection or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after the onset of illness.

Updated guidelines released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outline how to diagnose suspected cases of Zika virus infection among pregnant women based on how quickly they present with symptoms.

The guidance was updated in light of “the emerging data indicating that Zika virus RNA can be detected for prolonged periods in some pregnant women,” the CDC wrote in the July 25 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e1).

All pregnant women should be assessed for Zika virus at each of their prenatal care visits, regardless of their recent travel history or exposure to mosquitoes, by being evaluated for signs and symptoms of infection, such as fever, rash, and arthralgia. From there, management can take one of two directions.

The first direction involves women who are tested within 2 weeks of either symptom onset, or their suspected exposure to the virus. Pregnant women who are asymptomatic and do not live in an area with an ongoing Zika virus outbreak, as well as women who are symptomatic, should have their serum and urine analyzed using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test. If the result of this test is positive, it should be considered as confirmation that the woman has a “recent Zika virus infection.”

However, if the test results are negative, symptomatic women should undergo immunoglobin M testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus, while asymptomatic women should undergo just Zika virus IgM testing within 2-12 weeks of the possible exposure. In either case, if the tests come back negative, then the patient can be definitively cleared of any recent Zika virus infection. However, if either the Zika virus or dengue virus tests are positive or equivocal, then there is a “presumptive recent Zika virus or dengue virus or Flavivirus infection” in the woman, at which point plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) must be conducted.

The second direction for management involves pregnant women who are initially tested within 2-12 weeks of either symptom onset or suspected exposure to the virus. Asymptomatic women who do not live in an area with active Zika virus transmission, or do live in an area with ongoing Zika virus cases but are already in the first or second trimester of their pregnancy – along with any women who are symptomatic – should have their serum analyzed through IgM testing for both Zika virus and dengue virus.

If both results are negative, then there is no Zika virus infection. If the Zika virus test is negative but the dengue virus test is either positive or equivocal, the woman has a “presumptive dengue virus infection” and should undergo PRNT. If the Zika virus test is either positive or equivocal, then the woman has a “presumptive recent Zika virus or Flavivirus infection,” regardless of the dengue virus IgM result. In the latter case, the next step is to conduct a reflex Zika virus rRT-PCR test on both serum and urine. A negative result on the serum test should be followed by PRNT; a positive result should be taken as proof of a “recent Zika virus infection.”

For any diagnostic chain that ends with a PRNT, the results of that test can be interpreted in one of three ways. If the Zika virus PRNT result is at least 10 and the dengue virus result is less than 10, then there is a recent Zika virus infection. If both the Zika virus and dengue virus PRNT results are 10 or greater, than there is a Flavivirus infection, but the specific one cannot be determined. Finally, if both results are less than 10, then there is no evidence of a recent Zika virus infection.

“For symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered,” the CDC wrote. “If fetal abnormalities are present, rRT-PCR testing should also be performed on maternal serum and urine [but] a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result [more than] 12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection.”

For pregnant women with a diagnosis of a confirmed or presumptive Flavivirus infection, regardless of whether it’s specifically Zika virus or not, the CDC recommends getting serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks during pregnancy in order to monitor the fetus’s development, while “decisions regarding amniocentesis should be individualized for each clinical circumstance.” After the child’s birth, rRT-PCR should be conducted on the child’s cord blood and serum; Zika virus and dengue virus IgM are also recommended.

Pregnant women without a diagnosis of either Zika virus or dengue virus should have a prenatal ultrasound; if abnormalities are found in the fetus, CDC recommends that they have a repeat Zika virus rRT-PCR and IgM test and that clinicians base management on corresponding laboratory results. If nothing is found, however, then standard care can resume with ongoing vigilance to avoid Zika virus infections. Women with dengue virus diagnoses should follow the guidance that is currently in place.

“Pregnant women with laboratory evidence of confirmed or possible Zika virus infection who experience a fetal loss or stillbirth should be offered pathology testing for Zika virus infection,” the CDC added. “This testing might provide insight into the etiology of the fetal loss, which could inform a woman’s future pregnancy planning.”

The CDC also issued updated guidance for preventing sexual transmission of Zika virus and that applies to all men and women who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their sex partners (MMWR. ePub: 2016 25 Jul. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6529e2). The CDC advises couples in which a woman is pregnant to use barriers methods or abstain from sex for the duration of the pregnancy. For couples not planning pregnancy and in which there is a male partner with confirmed Zika virus infection or symptoms of infection, the men should use barrier methods or abstain from sex for at least 6 months after the onset of illness. For women with Zika virus infection, they should use barrier protection or abstain from sex for at least 8 weeks after the onset of illness.

FROM MMWR

Threatened miscarriage diagnosis increases risk for other poor outcomes

HELSINKI, FINLAND – Women with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy are at increased risk of developing complications that can contribute to term stillbirths, according to the findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis of data from 14 prospective studies – including 36,601 women with threatened miscarriage prior to 24 weeks of gestation – showed that the women were at significantly increased risk of preterm birth (odds ratio, 2.65), preterm premature rupture of membranes (OR, 2.98), placental abruption (OR, 2.95), placenta previa (OR, 4.37), low birth weight (OR, 1.57), and neonatal asphyxia (OR, 1.8), compared with women without threatened miscarriage, Rekha N. Pillai, MBBS, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology.

The risk of stillbirth/intrauterine death in the study was more than double in patients with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy, (OR, 2.02), said Dr. Pillai of University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, England.

Early threatened miscarriage also was associated with preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, neonatal death, and cesarean section, she noted.

Bleeding in early pregnancy occurs in 16%-25% of pregnant women, and women with this type of bleeding and a viable pregnancy noted on an ultrasound scan are diagnosed with threatened miscarriage, which can indicate a problem with placental development and dysfunction. This, in turn, explains the increased incidence of maternal and perinatal complications in women with early bleeding, Dr. Pillai explained.

A 2009 review and meta-analysis highlighted a need for more prospective studies, and several have been published since then. The current study represents an “updated systematic review,” she said.

Studies included in the current review were published between 1946 and 2015. Though limited by questionable quality of some of the studies included in the review, and potential confounding variables such as maternal age, ethnicity, body mass index, and obstetric history – which were not accounted for in some studies – the findings suggest a need for increased surveillance during the prenatal period in women with threatened miscarriage in early pregnancy to improve outcomes, she said.

Dr. Pillai reported having no financial disclosures.

HELSINKI, FINLAND – Women with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy are at increased risk of developing complications that can contribute to term stillbirths, according to the findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis of data from 14 prospective studies – including 36,601 women with threatened miscarriage prior to 24 weeks of gestation – showed that the women were at significantly increased risk of preterm birth (odds ratio, 2.65), preterm premature rupture of membranes (OR, 2.98), placental abruption (OR, 2.95), placenta previa (OR, 4.37), low birth weight (OR, 1.57), and neonatal asphyxia (OR, 1.8), compared with women without threatened miscarriage, Rekha N. Pillai, MBBS, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology.

The risk of stillbirth/intrauterine death in the study was more than double in patients with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy, (OR, 2.02), said Dr. Pillai of University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, England.

Early threatened miscarriage also was associated with preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, neonatal death, and cesarean section, she noted.

Bleeding in early pregnancy occurs in 16%-25% of pregnant women, and women with this type of bleeding and a viable pregnancy noted on an ultrasound scan are diagnosed with threatened miscarriage, which can indicate a problem with placental development and dysfunction. This, in turn, explains the increased incidence of maternal and perinatal complications in women with early bleeding, Dr. Pillai explained.

A 2009 review and meta-analysis highlighted a need for more prospective studies, and several have been published since then. The current study represents an “updated systematic review,” she said.

Studies included in the current review were published between 1946 and 2015. Though limited by questionable quality of some of the studies included in the review, and potential confounding variables such as maternal age, ethnicity, body mass index, and obstetric history – which were not accounted for in some studies – the findings suggest a need for increased surveillance during the prenatal period in women with threatened miscarriage in early pregnancy to improve outcomes, she said.

Dr. Pillai reported having no financial disclosures.

HELSINKI, FINLAND – Women with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy are at increased risk of developing complications that can contribute to term stillbirths, according to the findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis of data from 14 prospective studies – including 36,601 women with threatened miscarriage prior to 24 weeks of gestation – showed that the women were at significantly increased risk of preterm birth (odds ratio, 2.65), preterm premature rupture of membranes (OR, 2.98), placental abruption (OR, 2.95), placenta previa (OR, 4.37), low birth weight (OR, 1.57), and neonatal asphyxia (OR, 1.8), compared with women without threatened miscarriage, Rekha N. Pillai, MBBS, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology.

The risk of stillbirth/intrauterine death in the study was more than double in patients with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy, (OR, 2.02), said Dr. Pillai of University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, England.

Early threatened miscarriage also was associated with preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, neonatal death, and cesarean section, she noted.

Bleeding in early pregnancy occurs in 16%-25% of pregnant women, and women with this type of bleeding and a viable pregnancy noted on an ultrasound scan are diagnosed with threatened miscarriage, which can indicate a problem with placental development and dysfunction. This, in turn, explains the increased incidence of maternal and perinatal complications in women with early bleeding, Dr. Pillai explained.

A 2009 review and meta-analysis highlighted a need for more prospective studies, and several have been published since then. The current study represents an “updated systematic review,” she said.

Studies included in the current review were published between 1946 and 2015. Though limited by questionable quality of some of the studies included in the review, and potential confounding variables such as maternal age, ethnicity, body mass index, and obstetric history – which were not accounted for in some studies – the findings suggest a need for increased surveillance during the prenatal period in women with threatened miscarriage in early pregnancy to improve outcomes, she said.

Dr. Pillai reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ESHRE 2016

Key clinical point: Threatened miscarriage in early pregnancy increases the risk of developing complications that can contribute to term stillbirths.

Major finding: The risk of stillbirth/intrauterine death was more than double in patients with threatened miscarriage early in pregnancy (odds ratio, 2.02).

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 prospective studies involving 36,601 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Pillai reported having no financial disclosures.

CDC reports three new cases of Zika-related birth defects

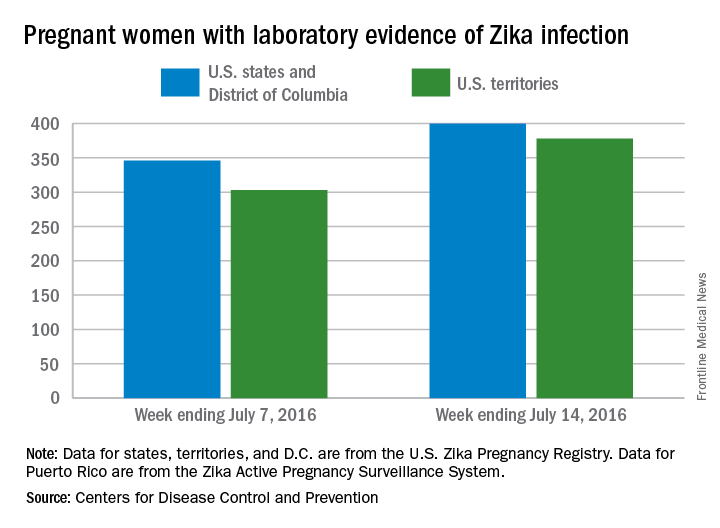

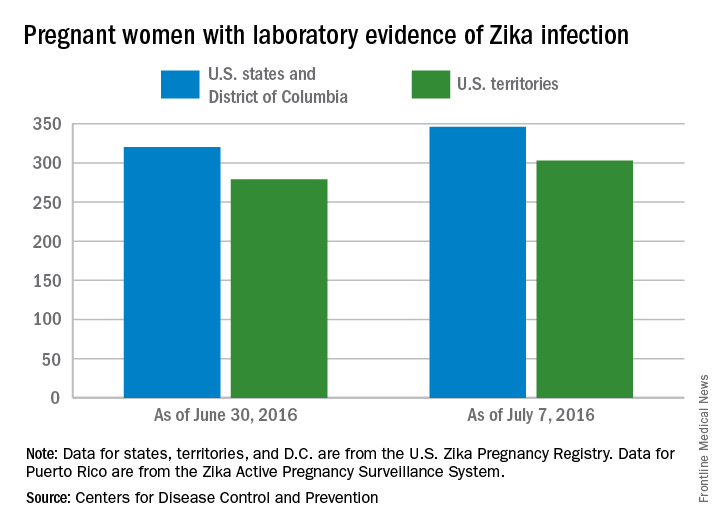

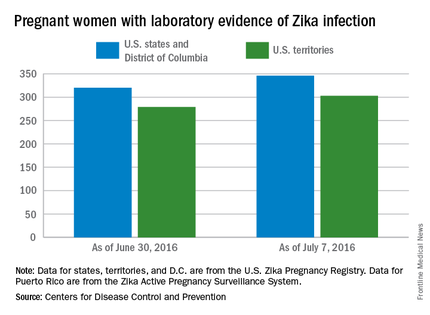

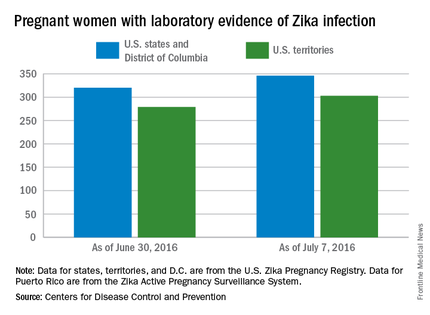

Three new cases of infants born with Zika virus–related birth defects were reported in the United States for the week ending July 14, 2016, along with 129 new infections in pregnant women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The three infants were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, with no new pregnancy losses reported in the states or U.S. territories. Totals for the year are 12 infants with birth defects, all in the states, and seven pregnancy losses, of which six occurred in the states, the CDC reported July 21. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

Of the 129 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 54 occurred in the states and 75 occurred in the U.S. territories. Those new cases bring the U.S. total to 778 for the year: 400 in the states and 378 in territories, the CDC also reported on July 21.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Three new cases of infants born with Zika virus–related birth defects were reported in the United States for the week ending July 14, 2016, along with 129 new infections in pregnant women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The three infants were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, with no new pregnancy losses reported in the states or U.S. territories. Totals for the year are 12 infants with birth defects, all in the states, and seven pregnancy losses, of which six occurred in the states, the CDC reported July 21. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

Of the 129 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 54 occurred in the states and 75 occurred in the U.S. territories. Those new cases bring the U.S. total to 778 for the year: 400 in the states and 378 in territories, the CDC also reported on July 21.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Three new cases of infants born with Zika virus–related birth defects were reported in the United States for the week ending July 14, 2016, along with 129 new infections in pregnant women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The three infants were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, with no new pregnancy losses reported in the states or U.S. territories. Totals for the year are 12 infants with birth defects, all in the states, and seven pregnancy losses, of which six occurred in the states, the CDC reported July 21. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

Of the 129 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 54 occurred in the states and 75 occurred in the U.S. territories. Those new cases bring the U.S. total to 778 for the year: 400 in the states and 378 in territories, the CDC also reported on July 21.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The role ob.gyns. can play in preventing Zika virus

In February of 2016, the World Health Organization declared Zika a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and the Centers for Disease and Prevention elevated its Zika Emergency Operation Center activation to Level 1, its highest level. The Zika epidemic is unique in many ways, particularly in that women and reproductive health care are at the center of the epidemic.

Most people who are infected with Zika are asymptomatic; those who do have symptoms generally have a mild, self-limited infection. However, a pregnant woman can pass the infection to her fetus, which can lead to severe outcomes. As ob.gyns., we are called upon to guide pregnant women who have been exposed or infected regarding testing, diagnosis, options counseling, surveillance, and management. Additionally, we can help pregnant women prevent Zika infection. Discuss avoiding travel for her and her partner(s) to areas with Zika. Encourage strategies for mosquito bite prevention if traveling to endemic areas and at home. Recommend abstaining from sex or using a condom for those who have partners who have recently traveled to areas with Zika transmission.

With that said, most of our patients are not pregnant. Many are capable of pregnancy and potentially at risk for unintended pregnancy since almost half of pregnancies in the United States are unintended (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 3;374[9]:843-52). Contraception for women who are not desiring pregnancy may help prevent unintended pregnancy, but also may help prevent the serious effects that can be seen with mother-to-fetus transmission of Zika. We can play a critical role in this important prevention message for nonpregnant women.

We do not know how long the Zika virus will continue to spread nor do we know whether we will have local transmission in the continental U.S. But we do know that travel is common and sexual transmission is possible. As such, all women need to be educated about the Zika virus. All women should be aware of the risks it poses for their reproductive health and be given an opportunity to discuss what that might mean to each of them. Whether a woman is planning a pregnancy, trying to avoid one, or is unsure of what she wants, having a conversation with her ob.gyn. may help her feel informed and supported in making the best decision for her right now. This may be particularly true of her plans for pregnancy timing and the use of contraception and condoms.

Beyond travel screening and mosquito bite prevention strategies, there are several key messages that we are uniquely poised to relay about Zika prevention. First, women who have been exposed to Zika should delay trying to conceive for 8 weeks. The recommendation for male partners to delay conception ranges from 8 weeks to 6 months depending upon local transmission and presence of symptoms. For those who are not trying to become pregnant or who want to delay pregnancy because of Zika concerns or exposures, we should offer the full range of contraceptive options and work with each patient to optimize her contraceptive selection, based on her individual preferences, goals, and needs. Finally, women should be counseled to avoid transmission from sex by choosing to not have sex or by using a condom with each act of sex with a partner who may have been exposed to Zika.

Our understanding of Zika infection is rapidly evolving. It will be particularly important for us to stay current on this issue. Providers can access up-to-date information about Zika, provider updates, patient information, posters and other information about the emergency response from the CDC’s website at www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html.

There are several tools available for guidance in these conversations. On July 1, 2016, the Office of Population Affairs released a toolkit for Providing Family Planning Care for Non-Pregnant Women and Men of Reproductive Age in the Context of Zika. It is available online at: www.hhs.gov/opa/news#toolkit.

The CDC also offers comprehensive guidance on providing contraception. Providers can access the Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, the Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, and Providing Quality Family Planning Services, all of which are available on the CDC website.

Dr. Kottke is an associate professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. She is the director of the Jane Fonda Center at Emory, which is involved in research and program development focused on adolescent sexual and reproductive health. She also serves as the medical consultant for the state of Georgia’s Family Planning Program. Dr. Kottke reported that she is a Nexplanon (Merck) trainer, is a consultant to CSL Behring, and serves on the advisory board for Evofem.

In February of 2016, the World Health Organization declared Zika a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and the Centers for Disease and Prevention elevated its Zika Emergency Operation Center activation to Level 1, its highest level. The Zika epidemic is unique in many ways, particularly in that women and reproductive health care are at the center of the epidemic.

Most people who are infected with Zika are asymptomatic; those who do have symptoms generally have a mild, self-limited infection. However, a pregnant woman can pass the infection to her fetus, which can lead to severe outcomes. As ob.gyns., we are called upon to guide pregnant women who have been exposed or infected regarding testing, diagnosis, options counseling, surveillance, and management. Additionally, we can help pregnant women prevent Zika infection. Discuss avoiding travel for her and her partner(s) to areas with Zika. Encourage strategies for mosquito bite prevention if traveling to endemic areas and at home. Recommend abstaining from sex or using a condom for those who have partners who have recently traveled to areas with Zika transmission.

With that said, most of our patients are not pregnant. Many are capable of pregnancy and potentially at risk for unintended pregnancy since almost half of pregnancies in the United States are unintended (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 3;374[9]:843-52). Contraception for women who are not desiring pregnancy may help prevent unintended pregnancy, but also may help prevent the serious effects that can be seen with mother-to-fetus transmission of Zika. We can play a critical role in this important prevention message for nonpregnant women.

We do not know how long the Zika virus will continue to spread nor do we know whether we will have local transmission in the continental U.S. But we do know that travel is common and sexual transmission is possible. As such, all women need to be educated about the Zika virus. All women should be aware of the risks it poses for their reproductive health and be given an opportunity to discuss what that might mean to each of them. Whether a woman is planning a pregnancy, trying to avoid one, or is unsure of what she wants, having a conversation with her ob.gyn. may help her feel informed and supported in making the best decision for her right now. This may be particularly true of her plans for pregnancy timing and the use of contraception and condoms.

Beyond travel screening and mosquito bite prevention strategies, there are several key messages that we are uniquely poised to relay about Zika prevention. First, women who have been exposed to Zika should delay trying to conceive for 8 weeks. The recommendation for male partners to delay conception ranges from 8 weeks to 6 months depending upon local transmission and presence of symptoms. For those who are not trying to become pregnant or who want to delay pregnancy because of Zika concerns or exposures, we should offer the full range of contraceptive options and work with each patient to optimize her contraceptive selection, based on her individual preferences, goals, and needs. Finally, women should be counseled to avoid transmission from sex by choosing to not have sex or by using a condom with each act of sex with a partner who may have been exposed to Zika.

Our understanding of Zika infection is rapidly evolving. It will be particularly important for us to stay current on this issue. Providers can access up-to-date information about Zika, provider updates, patient information, posters and other information about the emergency response from the CDC’s website at www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html.

There are several tools available for guidance in these conversations. On July 1, 2016, the Office of Population Affairs released a toolkit for Providing Family Planning Care for Non-Pregnant Women and Men of Reproductive Age in the Context of Zika. It is available online at: www.hhs.gov/opa/news#toolkit.

The CDC also offers comprehensive guidance on providing contraception. Providers can access the Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, the Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, and Providing Quality Family Planning Services, all of which are available on the CDC website.

Dr. Kottke is an associate professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. She is the director of the Jane Fonda Center at Emory, which is involved in research and program development focused on adolescent sexual and reproductive health. She also serves as the medical consultant for the state of Georgia’s Family Planning Program. Dr. Kottke reported that she is a Nexplanon (Merck) trainer, is a consultant to CSL Behring, and serves on the advisory board for Evofem.

In February of 2016, the World Health Organization declared Zika a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and the Centers for Disease and Prevention elevated its Zika Emergency Operation Center activation to Level 1, its highest level. The Zika epidemic is unique in many ways, particularly in that women and reproductive health care are at the center of the epidemic.

Most people who are infected with Zika are asymptomatic; those who do have symptoms generally have a mild, self-limited infection. However, a pregnant woman can pass the infection to her fetus, which can lead to severe outcomes. As ob.gyns., we are called upon to guide pregnant women who have been exposed or infected regarding testing, diagnosis, options counseling, surveillance, and management. Additionally, we can help pregnant women prevent Zika infection. Discuss avoiding travel for her and her partner(s) to areas with Zika. Encourage strategies for mosquito bite prevention if traveling to endemic areas and at home. Recommend abstaining from sex or using a condom for those who have partners who have recently traveled to areas with Zika transmission.

With that said, most of our patients are not pregnant. Many are capable of pregnancy and potentially at risk for unintended pregnancy since almost half of pregnancies in the United States are unintended (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 3;374[9]:843-52). Contraception for women who are not desiring pregnancy may help prevent unintended pregnancy, but also may help prevent the serious effects that can be seen with mother-to-fetus transmission of Zika. We can play a critical role in this important prevention message for nonpregnant women.

We do not know how long the Zika virus will continue to spread nor do we know whether we will have local transmission in the continental U.S. But we do know that travel is common and sexual transmission is possible. As such, all women need to be educated about the Zika virus. All women should be aware of the risks it poses for their reproductive health and be given an opportunity to discuss what that might mean to each of them. Whether a woman is planning a pregnancy, trying to avoid one, or is unsure of what she wants, having a conversation with her ob.gyn. may help her feel informed and supported in making the best decision for her right now. This may be particularly true of her plans for pregnancy timing and the use of contraception and condoms.

Beyond travel screening and mosquito bite prevention strategies, there are several key messages that we are uniquely poised to relay about Zika prevention. First, women who have been exposed to Zika should delay trying to conceive for 8 weeks. The recommendation for male partners to delay conception ranges from 8 weeks to 6 months depending upon local transmission and presence of symptoms. For those who are not trying to become pregnant or who want to delay pregnancy because of Zika concerns or exposures, we should offer the full range of contraceptive options and work with each patient to optimize her contraceptive selection, based on her individual preferences, goals, and needs. Finally, women should be counseled to avoid transmission from sex by choosing to not have sex or by using a condom with each act of sex with a partner who may have been exposed to Zika.

Our understanding of Zika infection is rapidly evolving. It will be particularly important for us to stay current on this issue. Providers can access up-to-date information about Zika, provider updates, patient information, posters and other information about the emergency response from the CDC’s website at www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html.

There are several tools available for guidance in these conversations. On July 1, 2016, the Office of Population Affairs released a toolkit for Providing Family Planning Care for Non-Pregnant Women and Men of Reproductive Age in the Context of Zika. It is available online at: www.hhs.gov/opa/news#toolkit.

The CDC also offers comprehensive guidance on providing contraception. Providers can access the Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, the Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, and Providing Quality Family Planning Services, all of which are available on the CDC website.

Dr. Kottke is an associate professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. She is the director of the Jane Fonda Center at Emory, which is involved in research and program development focused on adolescent sexual and reproductive health. She also serves as the medical consultant for the state of Georgia’s Family Planning Program. Dr. Kottke reported that she is a Nexplanon (Merck) trainer, is a consultant to CSL Behring, and serves on the advisory board for Evofem.

Was FHR properly monitored?

PARENT'S CLAIM: The pregnancy was at high risk because of the mother’s hypertension. The ObGyns misread the FHR at triage and discontinued FHR monitoring too early. If continuous FHR monitoring had occurred, fetal distress would have been detected earlier, resulting in a better outcome for the baby.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: There were no signs of fetal distress when the FHR monitoring was discontinued. Placental abruption is an acute event that cannot be predicted.

VERDICT: A Missouri defense verdict was returned.

Should the ObGyn have come to the hospital earlier?At 39 weeks’ gestation, a mother presented to the hospital for induction of labor. A FHR monitor was immediately placed. That evening, the ObGyn, who was not at the hospital, was notified that the mother had an elevated temperature and that the fetus was experiencing tachycardia. The ObGyn prescribed antibiotics, and the fever subsided. After an hour, the patient was fully dilated and started to push under the nurse’s supervision. Twenty minutes later, the ObGyn was notified that the fetus was experiencing variable decelerations. The ObGyn arrived in 30 minutes and ordered cesarean delivery. The baby was born 24 minutes later.

Ten hours after birth, the baby began to have seizures. He was transferred to another hospital and remained in the neonatal intensive care unit for 15 days. The child received a diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

PARENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in not coming to the hospital when the mother was feverish and the baby tachycardic. The baby experienced an acute hypoxic ischemic injury; an earlier cesarean delivery would have avoided brain injury.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: There was no breach in the standard of care. The infant did not meet all the criteria for an acute hypoxic ischemic injury. Based on a computed tomography scan taken after seizures began, the infant’s brain injury most likely occurred hours before birth.

VERDICT: A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from "Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts," with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

PARENT'S CLAIM: The pregnancy was at high risk because of the mother’s hypertension. The ObGyns misread the FHR at triage and discontinued FHR monitoring too early. If continuous FHR monitoring had occurred, fetal distress would have been detected earlier, resulting in a better outcome for the baby.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: There were no signs of fetal distress when the FHR monitoring was discontinued. Placental abruption is an acute event that cannot be predicted.

VERDICT: A Missouri defense verdict was returned.

Should the ObGyn have come to the hospital earlier?At 39 weeks’ gestation, a mother presented to the hospital for induction of labor. A FHR monitor was immediately placed. That evening, the ObGyn, who was not at the hospital, was notified that the mother had an elevated temperature and that the fetus was experiencing tachycardia. The ObGyn prescribed antibiotics, and the fever subsided. After an hour, the patient was fully dilated and started to push under the nurse’s supervision. Twenty minutes later, the ObGyn was notified that the fetus was experiencing variable decelerations. The ObGyn arrived in 30 minutes and ordered cesarean delivery. The baby was born 24 minutes later.

Ten hours after birth, the baby began to have seizures. He was transferred to another hospital and remained in the neonatal intensive care unit for 15 days. The child received a diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

PARENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in not coming to the hospital when the mother was feverish and the baby tachycardic. The baby experienced an acute hypoxic ischemic injury; an earlier cesarean delivery would have avoided brain injury.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: There was no breach in the standard of care. The infant did not meet all the criteria for an acute hypoxic ischemic injury. Based on a computed tomography scan taken after seizures began, the infant’s brain injury most likely occurred hours before birth.

VERDICT: A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from "Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts," with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

PARENT'S CLAIM: The pregnancy was at high risk because of the mother’s hypertension. The ObGyns misread the FHR at triage and discontinued FHR monitoring too early. If continuous FHR monitoring had occurred, fetal distress would have been detected earlier, resulting in a better outcome for the baby.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: There were no signs of fetal distress when the FHR monitoring was discontinued. Placental abruption is an acute event that cannot be predicted.

VERDICT: A Missouri defense verdict was returned.

Should the ObGyn have come to the hospital earlier?At 39 weeks’ gestation, a mother presented to the hospital for induction of labor. A FHR monitor was immediately placed. That evening, the ObGyn, who was not at the hospital, was notified that the mother had an elevated temperature and that the fetus was experiencing tachycardia. The ObGyn prescribed antibiotics, and the fever subsided. After an hour, the patient was fully dilated and started to push under the nurse’s supervision. Twenty minutes later, the ObGyn was notified that the fetus was experiencing variable decelerations. The ObGyn arrived in 30 minutes and ordered cesarean delivery. The baby was born 24 minutes later.

Ten hours after birth, the baby began to have seizures. He was transferred to another hospital and remained in the neonatal intensive care unit for 15 days. The child received a diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

PARENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in not coming to the hospital when the mother was feverish and the baby tachycardic. The baby experienced an acute hypoxic ischemic injury; an earlier cesarean delivery would have avoided brain injury.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: There was no breach in the standard of care. The infant did not meet all the criteria for an acute hypoxic ischemic injury. Based on a computed tomography scan taken after seizures began, the infant’s brain injury most likely occurred hours before birth.

VERDICT: A Virginia defense verdict was returned.