User login

Prescription opioid analgesics: Is there a risk for birth defects?

Concerns have been raised about the widespread use of opioid analgesics in the general population, and specifically among pregnant women.

In women of reproductive age, U.S. claims data for the years 2008-2012 indicate that 39.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women and 27.7% of privately insured women had at least one opioid analgesic prescription claim.1 Among pregnant women, approximately 4.4% reported use of opioid analgesics any time in the month before and throughout gestation in a sample of 11,724 control mothers who participated in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS) 1998-2011.2

Previous studies of first-trimester exposure to opioid analgesics have shown inconsistent associations with selected major congenital anomalies. A 2011 analysis of 1,693 first-trimester codeine-exposed pregnancies enrolled in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study found no evidence of an increased risk of major birth defects overall (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.5-1.1), compared with 65,316 unexposed pregnancies. However, this study had insufficient power to examine modest associations with most specific major birth defects.3

In contrast, two recent case-control studies have demonstrated significantly increased risks for early pregnancy opioid analgesic use and specific defects.

Broussard et al (2011) used data from the NBDPS 1997-2005 to test hypotheses related to specific defect associations previously reported in the literature, as well as to explore associations with additional defects. Therapeutic opioid use in early pregnancy was reported by 2.6% of 17,449 case mothers and 2.0% of 6,701 control mothers. The authors confirmed associations with some specific heart defects, (for example, conoventricular septal defects, atrioventricular septal defects, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome), and spina bifida, with ORs ranging from 2.0 to 2.7. In exploratory analysis, gastroschisis was also significantly associated with opioid analgesic exposure in early pregnancy (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1-2.9). Although additional analyses were performed stratified by specific opioid product (codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, meperidine), as might be expected, the most commonly used products (codeine and hydrocodone) were linked to a greater number of elevated ORs for specific defects.4

In the second case-control study, Yazdy et al (2013) used data collected in four cities in the United States and Canada and from two birth defect registries between 1998 and 2010 to examine periconceptional opioid use and risk for neural tube defects. The adjusted OR for spina bifida, comparing mothers of malformed infants with mothers of non-malformed infants, was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.3-5.0). To help rule out the possible contribution of recall bias, a sensitivity analysis was also conducted comparing mothers of malformed infants with mothers of infants with other malformations not implicated in the Broussard NBDPS study. The adjusted OR in this secondary analysis was somewhat attenuated but remained significantly elevated (adjusted OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1-4.1).5

The usual limitations apply to these large case-control studies, including the potential for mothers to inaccurately recall the use of, and specific gestational timing of, exposure to these medications. However, the sensitivity analysis conducted in the Yazdy et al study suggests that this bias did not account for the association between opioid analgesics and spina bifida. Although a wide range of important potential confounders were considered in both studies, unmeasured confounding could be a contributing factor. For example, it would be useful to have a comparison group of pregnant women with similar indications but no treatment with opioid analgesics during embryogenesis.

From a clinical perspective, given the proportion of unplanned pregnancies and the high prevalence of opioid analgesic dispensing in the United States, the potential for pregnancy should be considered when these medications are prescribed for women in their reproductive years. In a recognized pregnancy, to date, the risks reported for early pregnancy exposure are generally modest for specific defects. The rarity of even the most common of these specific defects means that these elevated ORs translate to very low absolute risks for any individual pregnancy.

As with other medications with a similar profile, need for the medication should be considered at the time of prescribing, and if an opioid analgesic is needed, consider the lowest effective dose of the most effective medication given for the shortest period of time necessary.

References

1. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:37-41.

2. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2015 Aug;103(8):703-12.

3. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Dec;67(12):1253-61.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Apr;204(4):314.e1-11.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Oct;122(4):838-44.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She receives no industry funding for the study of opioid analgesic medications in pregnancy. She does receive research funding for studies of other medications and vaccines in pregnancy from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi-Genzyme, Seqirus, Takeda, Teva, UCB. Email her at [email protected].

Concerns have been raised about the widespread use of opioid analgesics in the general population, and specifically among pregnant women.

In women of reproductive age, U.S. claims data for the years 2008-2012 indicate that 39.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women and 27.7% of privately insured women had at least one opioid analgesic prescription claim.1 Among pregnant women, approximately 4.4% reported use of opioid analgesics any time in the month before and throughout gestation in a sample of 11,724 control mothers who participated in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS) 1998-2011.2

Previous studies of first-trimester exposure to opioid analgesics have shown inconsistent associations with selected major congenital anomalies. A 2011 analysis of 1,693 first-trimester codeine-exposed pregnancies enrolled in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study found no evidence of an increased risk of major birth defects overall (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.5-1.1), compared with 65,316 unexposed pregnancies. However, this study had insufficient power to examine modest associations with most specific major birth defects.3

In contrast, two recent case-control studies have demonstrated significantly increased risks for early pregnancy opioid analgesic use and specific defects.

Broussard et al (2011) used data from the NBDPS 1997-2005 to test hypotheses related to specific defect associations previously reported in the literature, as well as to explore associations with additional defects. Therapeutic opioid use in early pregnancy was reported by 2.6% of 17,449 case mothers and 2.0% of 6,701 control mothers. The authors confirmed associations with some specific heart defects, (for example, conoventricular septal defects, atrioventricular septal defects, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome), and spina bifida, with ORs ranging from 2.0 to 2.7. In exploratory analysis, gastroschisis was also significantly associated with opioid analgesic exposure in early pregnancy (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1-2.9). Although additional analyses were performed stratified by specific opioid product (codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, meperidine), as might be expected, the most commonly used products (codeine and hydrocodone) were linked to a greater number of elevated ORs for specific defects.4

In the second case-control study, Yazdy et al (2013) used data collected in four cities in the United States and Canada and from two birth defect registries between 1998 and 2010 to examine periconceptional opioid use and risk for neural tube defects. The adjusted OR for spina bifida, comparing mothers of malformed infants with mothers of non-malformed infants, was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.3-5.0). To help rule out the possible contribution of recall bias, a sensitivity analysis was also conducted comparing mothers of malformed infants with mothers of infants with other malformations not implicated in the Broussard NBDPS study. The adjusted OR in this secondary analysis was somewhat attenuated but remained significantly elevated (adjusted OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1-4.1).5

The usual limitations apply to these large case-control studies, including the potential for mothers to inaccurately recall the use of, and specific gestational timing of, exposure to these medications. However, the sensitivity analysis conducted in the Yazdy et al study suggests that this bias did not account for the association between opioid analgesics and spina bifida. Although a wide range of important potential confounders were considered in both studies, unmeasured confounding could be a contributing factor. For example, it would be useful to have a comparison group of pregnant women with similar indications but no treatment with opioid analgesics during embryogenesis.

From a clinical perspective, given the proportion of unplanned pregnancies and the high prevalence of opioid analgesic dispensing in the United States, the potential for pregnancy should be considered when these medications are prescribed for women in their reproductive years. In a recognized pregnancy, to date, the risks reported for early pregnancy exposure are generally modest for specific defects. The rarity of even the most common of these specific defects means that these elevated ORs translate to very low absolute risks for any individual pregnancy.

As with other medications with a similar profile, need for the medication should be considered at the time of prescribing, and if an opioid analgesic is needed, consider the lowest effective dose of the most effective medication given for the shortest period of time necessary.

References

1. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:37-41.

2. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2015 Aug;103(8):703-12.

3. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Dec;67(12):1253-61.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Apr;204(4):314.e1-11.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Oct;122(4):838-44.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She receives no industry funding for the study of opioid analgesic medications in pregnancy. She does receive research funding for studies of other medications and vaccines in pregnancy from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi-Genzyme, Seqirus, Takeda, Teva, UCB. Email her at [email protected].

Concerns have been raised about the widespread use of opioid analgesics in the general population, and specifically among pregnant women.

In women of reproductive age, U.S. claims data for the years 2008-2012 indicate that 39.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women and 27.7% of privately insured women had at least one opioid analgesic prescription claim.1 Among pregnant women, approximately 4.4% reported use of opioid analgesics any time in the month before and throughout gestation in a sample of 11,724 control mothers who participated in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS) 1998-2011.2

Previous studies of first-trimester exposure to opioid analgesics have shown inconsistent associations with selected major congenital anomalies. A 2011 analysis of 1,693 first-trimester codeine-exposed pregnancies enrolled in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study found no evidence of an increased risk of major birth defects overall (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.5-1.1), compared with 65,316 unexposed pregnancies. However, this study had insufficient power to examine modest associations with most specific major birth defects.3

In contrast, two recent case-control studies have demonstrated significantly increased risks for early pregnancy opioid analgesic use and specific defects.

Broussard et al (2011) used data from the NBDPS 1997-2005 to test hypotheses related to specific defect associations previously reported in the literature, as well as to explore associations with additional defects. Therapeutic opioid use in early pregnancy was reported by 2.6% of 17,449 case mothers and 2.0% of 6,701 control mothers. The authors confirmed associations with some specific heart defects, (for example, conoventricular septal defects, atrioventricular septal defects, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome), and spina bifida, with ORs ranging from 2.0 to 2.7. In exploratory analysis, gastroschisis was also significantly associated with opioid analgesic exposure in early pregnancy (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1-2.9). Although additional analyses were performed stratified by specific opioid product (codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, meperidine), as might be expected, the most commonly used products (codeine and hydrocodone) were linked to a greater number of elevated ORs for specific defects.4

In the second case-control study, Yazdy et al (2013) used data collected in four cities in the United States and Canada and from two birth defect registries between 1998 and 2010 to examine periconceptional opioid use and risk for neural tube defects. The adjusted OR for spina bifida, comparing mothers of malformed infants with mothers of non-malformed infants, was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.3-5.0). To help rule out the possible contribution of recall bias, a sensitivity analysis was also conducted comparing mothers of malformed infants with mothers of infants with other malformations not implicated in the Broussard NBDPS study. The adjusted OR in this secondary analysis was somewhat attenuated but remained significantly elevated (adjusted OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1-4.1).5

The usual limitations apply to these large case-control studies, including the potential for mothers to inaccurately recall the use of, and specific gestational timing of, exposure to these medications. However, the sensitivity analysis conducted in the Yazdy et al study suggests that this bias did not account for the association between opioid analgesics and spina bifida. Although a wide range of important potential confounders were considered in both studies, unmeasured confounding could be a contributing factor. For example, it would be useful to have a comparison group of pregnant women with similar indications but no treatment with opioid analgesics during embryogenesis.

From a clinical perspective, given the proportion of unplanned pregnancies and the high prevalence of opioid analgesic dispensing in the United States, the potential for pregnancy should be considered when these medications are prescribed for women in their reproductive years. In a recognized pregnancy, to date, the risks reported for early pregnancy exposure are generally modest for specific defects. The rarity of even the most common of these specific defects means that these elevated ORs translate to very low absolute risks for any individual pregnancy.

As with other medications with a similar profile, need for the medication should be considered at the time of prescribing, and if an opioid analgesic is needed, consider the lowest effective dose of the most effective medication given for the shortest period of time necessary.

References

1. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:37-41.

2. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2015 Aug;103(8):703-12.

3. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Dec;67(12):1253-61.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Apr;204(4):314.e1-11.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Oct;122(4):838-44.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She receives no industry funding for the study of opioid analgesic medications in pregnancy. She does receive research funding for studies of other medications and vaccines in pregnancy from Amgen, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi-Genzyme, Seqirus, Takeda, Teva, UCB. Email her at [email protected].

Olympic Games create novel opportunity to study Zika virus

Behind the competition and pageantry of the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, researchers at the University of Utah will be busy monitoring a subset of athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee staff for potential Zika virus exposure.

“Of everyone I talk to who’s at risk for Zika virus, their No. 1 question is, what are the risks to my reproductive health?” said the study’s principal investigator Carrie L. Byington, MD, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist who is codirector of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “Can I have a healthy baby? How can I protect that opportunity to reproduce? We are dedicated to trying to find some answers.”

In a study funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Dr. Byington and a team of six other clinicians will recruit up to 1,000 athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) staff attending the games to complete health surveys and undergo pre- and post-travel periodic antibody testing for Zika virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has emerged in the Americas with local transmission identified in 30 countries and territories as of April 2016, including Brazil. From that group they expect to identify infected individuals. “Hopefully, it’s a very small proportion of the group but we think that we will identify some, because it is going to be impossible to prevent all mosquito exposure, even over the short term,” Dr. Byington said. Those found to harbor Zika virus by antibody testing will be followed for up to 2 years and will be asked to submit self-collected samples of blood, urine, saliva, semen, and vaginal secretions monthly. Affected individuals who wish to conceive after the games will have access to the study personnel, who include four infectious disease specialists, two obstetrician-gynecologists, and a laboratory expert. “We will have monthly testing and direct consultation with them regarding their test results and help them make the best reproductive decisions they can,” Dr. Byington said.

In April 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that fetal infection with Zika virus was the cause of microcephaly and other severe brain anomalies that result in permanent morbidity in surviving infants. According to a description of the current study published by the National Institutes of Health, many questions remain regarding infection with Zika virus, including the duration and potential for sexual or perinatal transmission from body fluids; the short and long-term reproductive outcomes of individuals infected with Zika virus; and the outcomes for infants born to men and women with either symptomatic or asymptomatic Zika virus infection. The researchers consider each study participant as equally susceptible to Zika virus exposure, regardless of his or her sport or role with the USOC. “People will be both indoors and outdoors, and these are indoor-dwelling mosquitoes, so I don’t think we can completely eliminate the risk for any type of traveler,” Dr. Byington said. “We’re very interested in the water venues, but we’re also concerned about standing water outside other venues or hotel rooms.” If a study participant falls ill in Rio de Janeiro with symptoms consistent with Zika virus, USOC medical personnel will send samples of blood, urine, and saliva to the Utah-based research team for confirmatory polymerase chain reaction testing.

The idea for the current study grew out of a pilot trial that Dr. Byington and her associates conducted in 150 individuals affiliated with the USOC who were traveling back and forth to Brazil in preparation for the games during March and April of 2016. It enabled the researchers to develop online web-based tools for consenting, tracking, and returning test results. “It allowed us to do some work with our laboratory facilities for shipping and receiving specimens and processing and running specimens and returning some results,” Dr. Byington said. “That work has been really important. We found that about one-third of our pilot was interested in becoming pregnant very shortly after the games, so that was very important information that we were able to share with the USOC and the NIH. This is a group that is very interested in their reproductive health, which makes an ideal cohort for the study.”

David Turok, MD, an ob.gyn. and member of the research team, planned long ago to attend the Olympic Games in Rio as a spectator with his wife and 14-year-old son. He intends to carry out those plans and described the current study as a unique opportunity to better understand the Zika virus. “The need for data on the topic is pressing,” said Dr. Turok, who directs the family planning fellowship at the University of Utah. “People who are Olympic athletes and coaches are probably more likely to plan their lives. We know from a wealth of epidemiologic data that people who plan their pregnancies have better outcomes. This is something that our society has done a really poor job in communicating: the challenges of parenting and the benefits of planning pregnancy and making the most effective methods of contraception available. This study is an opportunity to better our game. There’s probably no better opportunity for prospective evaluation of a group of people who we know are going to have some exposure [to Zika virus]. The known exposure and the known desired outcome make it a unique opportunity.”

The 2016 Summer Olympics will take place in Rio de Janeiro Aug. 5-21, while the Paralympic Games take place Sept. 7-18. Dr. Byington said that she hopes to be able to share preliminary study results with the public sometime in October.

Behind the competition and pageantry of the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, researchers at the University of Utah will be busy monitoring a subset of athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee staff for potential Zika virus exposure.

“Of everyone I talk to who’s at risk for Zika virus, their No. 1 question is, what are the risks to my reproductive health?” said the study’s principal investigator Carrie L. Byington, MD, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist who is codirector of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “Can I have a healthy baby? How can I protect that opportunity to reproduce? We are dedicated to trying to find some answers.”

In a study funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Dr. Byington and a team of six other clinicians will recruit up to 1,000 athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) staff attending the games to complete health surveys and undergo pre- and post-travel periodic antibody testing for Zika virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has emerged in the Americas with local transmission identified in 30 countries and territories as of April 2016, including Brazil. From that group they expect to identify infected individuals. “Hopefully, it’s a very small proportion of the group but we think that we will identify some, because it is going to be impossible to prevent all mosquito exposure, even over the short term,” Dr. Byington said. Those found to harbor Zika virus by antibody testing will be followed for up to 2 years and will be asked to submit self-collected samples of blood, urine, saliva, semen, and vaginal secretions monthly. Affected individuals who wish to conceive after the games will have access to the study personnel, who include four infectious disease specialists, two obstetrician-gynecologists, and a laboratory expert. “We will have monthly testing and direct consultation with them regarding their test results and help them make the best reproductive decisions they can,” Dr. Byington said.

In April 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that fetal infection with Zika virus was the cause of microcephaly and other severe brain anomalies that result in permanent morbidity in surviving infants. According to a description of the current study published by the National Institutes of Health, many questions remain regarding infection with Zika virus, including the duration and potential for sexual or perinatal transmission from body fluids; the short and long-term reproductive outcomes of individuals infected with Zika virus; and the outcomes for infants born to men and women with either symptomatic or asymptomatic Zika virus infection. The researchers consider each study participant as equally susceptible to Zika virus exposure, regardless of his or her sport or role with the USOC. “People will be both indoors and outdoors, and these are indoor-dwelling mosquitoes, so I don’t think we can completely eliminate the risk for any type of traveler,” Dr. Byington said. “We’re very interested in the water venues, but we’re also concerned about standing water outside other venues or hotel rooms.” If a study participant falls ill in Rio de Janeiro with symptoms consistent with Zika virus, USOC medical personnel will send samples of blood, urine, and saliva to the Utah-based research team for confirmatory polymerase chain reaction testing.

The idea for the current study grew out of a pilot trial that Dr. Byington and her associates conducted in 150 individuals affiliated with the USOC who were traveling back and forth to Brazil in preparation for the games during March and April of 2016. It enabled the researchers to develop online web-based tools for consenting, tracking, and returning test results. “It allowed us to do some work with our laboratory facilities for shipping and receiving specimens and processing and running specimens and returning some results,” Dr. Byington said. “That work has been really important. We found that about one-third of our pilot was interested in becoming pregnant very shortly after the games, so that was very important information that we were able to share with the USOC and the NIH. This is a group that is very interested in their reproductive health, which makes an ideal cohort for the study.”

David Turok, MD, an ob.gyn. and member of the research team, planned long ago to attend the Olympic Games in Rio as a spectator with his wife and 14-year-old son. He intends to carry out those plans and described the current study as a unique opportunity to better understand the Zika virus. “The need for data on the topic is pressing,” said Dr. Turok, who directs the family planning fellowship at the University of Utah. “People who are Olympic athletes and coaches are probably more likely to plan their lives. We know from a wealth of epidemiologic data that people who plan their pregnancies have better outcomes. This is something that our society has done a really poor job in communicating: the challenges of parenting and the benefits of planning pregnancy and making the most effective methods of contraception available. This study is an opportunity to better our game. There’s probably no better opportunity for prospective evaluation of a group of people who we know are going to have some exposure [to Zika virus]. The known exposure and the known desired outcome make it a unique opportunity.”

The 2016 Summer Olympics will take place in Rio de Janeiro Aug. 5-21, while the Paralympic Games take place Sept. 7-18. Dr. Byington said that she hopes to be able to share preliminary study results with the public sometime in October.

Behind the competition and pageantry of the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, researchers at the University of Utah will be busy monitoring a subset of athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee staff for potential Zika virus exposure.

“Of everyone I talk to who’s at risk for Zika virus, their No. 1 question is, what are the risks to my reproductive health?” said the study’s principal investigator Carrie L. Byington, MD, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist who is codirector of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “Can I have a healthy baby? How can I protect that opportunity to reproduce? We are dedicated to trying to find some answers.”

In a study funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Dr. Byington and a team of six other clinicians will recruit up to 1,000 athletes, coaches, and other U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) staff attending the games to complete health surveys and undergo pre- and post-travel periodic antibody testing for Zika virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has emerged in the Americas with local transmission identified in 30 countries and territories as of April 2016, including Brazil. From that group they expect to identify infected individuals. “Hopefully, it’s a very small proportion of the group but we think that we will identify some, because it is going to be impossible to prevent all mosquito exposure, even over the short term,” Dr. Byington said. Those found to harbor Zika virus by antibody testing will be followed for up to 2 years and will be asked to submit self-collected samples of blood, urine, saliva, semen, and vaginal secretions monthly. Affected individuals who wish to conceive after the games will have access to the study personnel, who include four infectious disease specialists, two obstetrician-gynecologists, and a laboratory expert. “We will have monthly testing and direct consultation with them regarding their test results and help them make the best reproductive decisions they can,” Dr. Byington said.

In April 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that fetal infection with Zika virus was the cause of microcephaly and other severe brain anomalies that result in permanent morbidity in surviving infants. According to a description of the current study published by the National Institutes of Health, many questions remain regarding infection with Zika virus, including the duration and potential for sexual or perinatal transmission from body fluids; the short and long-term reproductive outcomes of individuals infected with Zika virus; and the outcomes for infants born to men and women with either symptomatic or asymptomatic Zika virus infection. The researchers consider each study participant as equally susceptible to Zika virus exposure, regardless of his or her sport or role with the USOC. “People will be both indoors and outdoors, and these are indoor-dwelling mosquitoes, so I don’t think we can completely eliminate the risk for any type of traveler,” Dr. Byington said. “We’re very interested in the water venues, but we’re also concerned about standing water outside other venues or hotel rooms.” If a study participant falls ill in Rio de Janeiro with symptoms consistent with Zika virus, USOC medical personnel will send samples of blood, urine, and saliva to the Utah-based research team for confirmatory polymerase chain reaction testing.

The idea for the current study grew out of a pilot trial that Dr. Byington and her associates conducted in 150 individuals affiliated with the USOC who were traveling back and forth to Brazil in preparation for the games during March and April of 2016. It enabled the researchers to develop online web-based tools for consenting, tracking, and returning test results. “It allowed us to do some work with our laboratory facilities for shipping and receiving specimens and processing and running specimens and returning some results,” Dr. Byington said. “That work has been really important. We found that about one-third of our pilot was interested in becoming pregnant very shortly after the games, so that was very important information that we were able to share with the USOC and the NIH. This is a group that is very interested in their reproductive health, which makes an ideal cohort for the study.”

David Turok, MD, an ob.gyn. and member of the research team, planned long ago to attend the Olympic Games in Rio as a spectator with his wife and 14-year-old son. He intends to carry out those plans and described the current study as a unique opportunity to better understand the Zika virus. “The need for data on the topic is pressing,” said Dr. Turok, who directs the family planning fellowship at the University of Utah. “People who are Olympic athletes and coaches are probably more likely to plan their lives. We know from a wealth of epidemiologic data that people who plan their pregnancies have better outcomes. This is something that our society has done a really poor job in communicating: the challenges of parenting and the benefits of planning pregnancy and making the most effective methods of contraception available. This study is an opportunity to better our game. There’s probably no better opportunity for prospective evaluation of a group of people who we know are going to have some exposure [to Zika virus]. The known exposure and the known desired outcome make it a unique opportunity.”

The 2016 Summer Olympics will take place in Rio de Janeiro Aug. 5-21, while the Paralympic Games take place Sept. 7-18. Dr. Byington said that she hopes to be able to share preliminary study results with the public sometime in October.

Early preterm birth poses highest risk for recurrence

Women who have had a preterm or early-term birth are at greater risk for an early delivery during a subsequent pregnancy, compared with women whose previous pregnancies have been full term, according to a large cohort study.

“This study confirms that a prior preterm birth increases the risk for a subsequent preterm birth with higher odds among those with a prior early preterm birth. Risks extend to both spontaneous and indicated prior preterm birth,” Juan Yang, PhD, of the California Department of Public Health, and his colleagues wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:364-72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001506).

The researchers retrospectively examined the records of 163,889 singleton live births that occurred in California from 2005 through 2011 whose mothers had experienced two consecutive pregnancies over that time period that had gestation periods of anywhere between 20 and 44 weeks.

Women were placed into cohorts based on the gestation periods of their first and second pregnancies: fewer than 32 weeks (early preterm), 32-36 weeks (preterm), 37-38 weeks (early term), and 39 weeks or more (full term).

Women whose first pregnancy lasted for fewer than 32 weeks’ gestation – an early preterm birth – were at the highest risk of having another delivery at fewer than 32 weeks in their second pregnancy, compared with women with term pregnancies (adjusted odds ratio, 23.3; 95% confidence interval, 17.2-31.7).

Women with a prior early-term birth (37-38 weeks) had more than a twofold increased risk for a preterm birth, with an adjusted OR of 2.0 for a subsequent birth before 32 weeks and an adjusted OR of 3.0 for a subsequent birth from 32 to 36 weeks of gestation. The adjusted OR for another early-term birth in this group was 2.2.

The researchers wrote that their findings “provide a better understanding of early-term birth and the importance of continuation of gestation beyond 38 weeks of gestation,” noting that “although the association of prior early-term birth with subsequent preterm birth is less strong than prior preterm birth, many more women fall in this category, making this an important risk factor to the overall societal burden of preterm birth.”

The study was funded by the Preterm Birth Initiative-California; the University of California, San Francisco; the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Centers; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Women who have had a preterm or early-term birth are at greater risk for an early delivery during a subsequent pregnancy, compared with women whose previous pregnancies have been full term, according to a large cohort study.

“This study confirms that a prior preterm birth increases the risk for a subsequent preterm birth with higher odds among those with a prior early preterm birth. Risks extend to both spontaneous and indicated prior preterm birth,” Juan Yang, PhD, of the California Department of Public Health, and his colleagues wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:364-72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001506).

The researchers retrospectively examined the records of 163,889 singleton live births that occurred in California from 2005 through 2011 whose mothers had experienced two consecutive pregnancies over that time period that had gestation periods of anywhere between 20 and 44 weeks.

Women were placed into cohorts based on the gestation periods of their first and second pregnancies: fewer than 32 weeks (early preterm), 32-36 weeks (preterm), 37-38 weeks (early term), and 39 weeks or more (full term).

Women whose first pregnancy lasted for fewer than 32 weeks’ gestation – an early preterm birth – were at the highest risk of having another delivery at fewer than 32 weeks in their second pregnancy, compared with women with term pregnancies (adjusted odds ratio, 23.3; 95% confidence interval, 17.2-31.7).

Women with a prior early-term birth (37-38 weeks) had more than a twofold increased risk for a preterm birth, with an adjusted OR of 2.0 for a subsequent birth before 32 weeks and an adjusted OR of 3.0 for a subsequent birth from 32 to 36 weeks of gestation. The adjusted OR for another early-term birth in this group was 2.2.

The researchers wrote that their findings “provide a better understanding of early-term birth and the importance of continuation of gestation beyond 38 weeks of gestation,” noting that “although the association of prior early-term birth with subsequent preterm birth is less strong than prior preterm birth, many more women fall in this category, making this an important risk factor to the overall societal burden of preterm birth.”

The study was funded by the Preterm Birth Initiative-California; the University of California, San Francisco; the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Centers; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Women who have had a preterm or early-term birth are at greater risk for an early delivery during a subsequent pregnancy, compared with women whose previous pregnancies have been full term, according to a large cohort study.

“This study confirms that a prior preterm birth increases the risk for a subsequent preterm birth with higher odds among those with a prior early preterm birth. Risks extend to both spontaneous and indicated prior preterm birth,” Juan Yang, PhD, of the California Department of Public Health, and his colleagues wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:364-72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001506).

The researchers retrospectively examined the records of 163,889 singleton live births that occurred in California from 2005 through 2011 whose mothers had experienced two consecutive pregnancies over that time period that had gestation periods of anywhere between 20 and 44 weeks.

Women were placed into cohorts based on the gestation periods of their first and second pregnancies: fewer than 32 weeks (early preterm), 32-36 weeks (preterm), 37-38 weeks (early term), and 39 weeks or more (full term).

Women whose first pregnancy lasted for fewer than 32 weeks’ gestation – an early preterm birth – were at the highest risk of having another delivery at fewer than 32 weeks in their second pregnancy, compared with women with term pregnancies (adjusted odds ratio, 23.3; 95% confidence interval, 17.2-31.7).

Women with a prior early-term birth (37-38 weeks) had more than a twofold increased risk for a preterm birth, with an adjusted OR of 2.0 for a subsequent birth before 32 weeks and an adjusted OR of 3.0 for a subsequent birth from 32 to 36 weeks of gestation. The adjusted OR for another early-term birth in this group was 2.2.

The researchers wrote that their findings “provide a better understanding of early-term birth and the importance of continuation of gestation beyond 38 weeks of gestation,” noting that “although the association of prior early-term birth with subsequent preterm birth is less strong than prior preterm birth, many more women fall in this category, making this an important risk factor to the overall societal burden of preterm birth.”

The study was funded by the Preterm Birth Initiative-California; the University of California, San Francisco; the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Centers; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Earlier preterm or early-term birth is a reliable indicator of a woman’s likelihood to have another early birth.

Major finding: Women with a prior early-term birth had a twofold increased risk for a subsequent birth before 32 weeks’ gestation (adjusted OR, 2.0).

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 163,889 California women who gave birth to neonates between 20 and 44 weeks of gestation from 2005 to 2011.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Preterm Birth Initiative-California; the University of California, San Francisco; the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Centers; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Vasodilator, biomarkers present potential for preeclampsia care

Treatment with oral sildenafil citrate significantly extended gestation by 4 days, compared with placebo in women with preeclampsia in a randomized trial.

The findings come from one of a trio of studies looking at efforts to improve outcomes for women with preeclampsia, which were published online July 11 in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“We hypothesized that the potential increase in in utero placental and fetoplacental blood flow with the use of sildenafil citrate may be associated with pregnancy prolongation (the primary study outcome) and improved maternal and perinatal outcomes,” wrote Alberto Trapani Jr., MD, PhD, of Hospital of Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, and his colleagues (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:253-259. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001518).

The researchers randomized 93 singleton pregnancies with preeclampsia at 24 to 33 weeks’ gestation to receive 50 mg oral sildenafil citrate (47 patients) or a placebo (46 patients) every 8 hours. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups.

Overall, pregnancies lasted an average of another 14.4 days in the sildenafil group, compared with 10.4 days in the placebo group. Additionally, the percent reduction in the pulsality indices of both uterine arteries and umbilical arteries were significantly higher in the sildenafil group, compared with the placebo group (22.5% vs. 2.1% and 18.5% vs. 2.5%, respectively). Maternal blood pressure before and 24 hours after randomization was lower with sildenafil. Incidence of adverse effects, perinatal morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups.

“These results, combined with the results of other studies, are promising,” although larger studies with earlier treatment initiation are needed, the researchers wrote. Evaluation of other phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors also may be useful in treating preeclampsia, they noted. Dr. Trapani and his colleagues reported having no financial conflicts.

Two other studies published in the same issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology focused on using biomarkers to help predict delivery times in women with suspected preeclampsia.

Any one of several single angiogenesis-related biomarkers can be a useful diagnostic test for preeclampsia, wrote Suzy Duckworth, MBBS, of King’s College London and her colleagues. In a prospective, observational study of 423 women with suspected preeclampsia, the researchers found that a combination of biomarkers including placental growth factor (PlGF) was not significantly better than PlGF alone (receiver operating curve area of 0.90 and 0.87, respectively) for predicting preeclampsia requiring delivery within 14 days. Two other single markers, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and endoglin, yielded similar results; each demonstrated a receiver operating curve area of 0.83.

“It is currently difficult to distinguish preeclampsia of a severity that requires early delivery from other less serious phenotypes,” the researchers wrote. “An accurate biomarker (or panel of biomarkers) to enable prognosis of perinatal complications could have a substantial effect on management strategies, with the aim of minimizing adverse maternal and fetal outcomes,” they wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:245-252. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001508).

Dr. Duckworth had no financial conflicts to disclose, but several of her coauthors disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies and one coauthor is a minority shareholder in Metabolomic Diagnostics, a company with an interest in preeclampsia biomarkers.

In another study including 1,041 women with suspected preeclampsia, those with a sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 were nearly three times as likely to deliver on the day of the test than women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less, wrote Harald Zeisler, MD, of Medical University Vienna and his colleagues (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:261-269. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001525).

Women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 also had significantly shorter remaining times to delivery than women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less (median 17 days vs. 51 days). The study was a secondary analysis of an observational cohort study of women aged 18 years and older from 24 to 36 6/7 weeks’ gestation.

In a preterm birth analysis of 848 women, 71% of the 184 women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 had a preterm delivery, compared with 18% of the 664 women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less.

The future clinical use of the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio “may potentially assist in informing the health care team of an impending risk to the mother, fetus, or both that may require further assessment and medical intervention,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Zeisler and several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including Roche Diagnostics, which sponsored the study.

Treatment with oral sildenafil citrate significantly extended gestation by 4 days, compared with placebo in women with preeclampsia in a randomized trial.

The findings come from one of a trio of studies looking at efforts to improve outcomes for women with preeclampsia, which were published online July 11 in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“We hypothesized that the potential increase in in utero placental and fetoplacental blood flow with the use of sildenafil citrate may be associated with pregnancy prolongation (the primary study outcome) and improved maternal and perinatal outcomes,” wrote Alberto Trapani Jr., MD, PhD, of Hospital of Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, and his colleagues (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:253-259. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001518).

The researchers randomized 93 singleton pregnancies with preeclampsia at 24 to 33 weeks’ gestation to receive 50 mg oral sildenafil citrate (47 patients) or a placebo (46 patients) every 8 hours. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups.

Overall, pregnancies lasted an average of another 14.4 days in the sildenafil group, compared with 10.4 days in the placebo group. Additionally, the percent reduction in the pulsality indices of both uterine arteries and umbilical arteries were significantly higher in the sildenafil group, compared with the placebo group (22.5% vs. 2.1% and 18.5% vs. 2.5%, respectively). Maternal blood pressure before and 24 hours after randomization was lower with sildenafil. Incidence of adverse effects, perinatal morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups.

“These results, combined with the results of other studies, are promising,” although larger studies with earlier treatment initiation are needed, the researchers wrote. Evaluation of other phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors also may be useful in treating preeclampsia, they noted. Dr. Trapani and his colleagues reported having no financial conflicts.

Two other studies published in the same issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology focused on using biomarkers to help predict delivery times in women with suspected preeclampsia.

Any one of several single angiogenesis-related biomarkers can be a useful diagnostic test for preeclampsia, wrote Suzy Duckworth, MBBS, of King’s College London and her colleagues. In a prospective, observational study of 423 women with suspected preeclampsia, the researchers found that a combination of biomarkers including placental growth factor (PlGF) was not significantly better than PlGF alone (receiver operating curve area of 0.90 and 0.87, respectively) for predicting preeclampsia requiring delivery within 14 days. Two other single markers, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and endoglin, yielded similar results; each demonstrated a receiver operating curve area of 0.83.

“It is currently difficult to distinguish preeclampsia of a severity that requires early delivery from other less serious phenotypes,” the researchers wrote. “An accurate biomarker (or panel of biomarkers) to enable prognosis of perinatal complications could have a substantial effect on management strategies, with the aim of minimizing adverse maternal and fetal outcomes,” they wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:245-252. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001508).

Dr. Duckworth had no financial conflicts to disclose, but several of her coauthors disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies and one coauthor is a minority shareholder in Metabolomic Diagnostics, a company with an interest in preeclampsia biomarkers.

In another study including 1,041 women with suspected preeclampsia, those with a sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 were nearly three times as likely to deliver on the day of the test than women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less, wrote Harald Zeisler, MD, of Medical University Vienna and his colleagues (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:261-269. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001525).

Women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 also had significantly shorter remaining times to delivery than women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less (median 17 days vs. 51 days). The study was a secondary analysis of an observational cohort study of women aged 18 years and older from 24 to 36 6/7 weeks’ gestation.

In a preterm birth analysis of 848 women, 71% of the 184 women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 had a preterm delivery, compared with 18% of the 664 women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less.

The future clinical use of the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio “may potentially assist in informing the health care team of an impending risk to the mother, fetus, or both that may require further assessment and medical intervention,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Zeisler and several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including Roche Diagnostics, which sponsored the study.

Treatment with oral sildenafil citrate significantly extended gestation by 4 days, compared with placebo in women with preeclampsia in a randomized trial.

The findings come from one of a trio of studies looking at efforts to improve outcomes for women with preeclampsia, which were published online July 11 in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“We hypothesized that the potential increase in in utero placental and fetoplacental blood flow with the use of sildenafil citrate may be associated with pregnancy prolongation (the primary study outcome) and improved maternal and perinatal outcomes,” wrote Alberto Trapani Jr., MD, PhD, of Hospital of Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis, Brazil, and his colleagues (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:253-259. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001518).

The researchers randomized 93 singleton pregnancies with preeclampsia at 24 to 33 weeks’ gestation to receive 50 mg oral sildenafil citrate (47 patients) or a placebo (46 patients) every 8 hours. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups.

Overall, pregnancies lasted an average of another 14.4 days in the sildenafil group, compared with 10.4 days in the placebo group. Additionally, the percent reduction in the pulsality indices of both uterine arteries and umbilical arteries were significantly higher in the sildenafil group, compared with the placebo group (22.5% vs. 2.1% and 18.5% vs. 2.5%, respectively). Maternal blood pressure before and 24 hours after randomization was lower with sildenafil. Incidence of adverse effects, perinatal morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups.

“These results, combined with the results of other studies, are promising,” although larger studies with earlier treatment initiation are needed, the researchers wrote. Evaluation of other phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors also may be useful in treating preeclampsia, they noted. Dr. Trapani and his colleagues reported having no financial conflicts.

Two other studies published in the same issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology focused on using biomarkers to help predict delivery times in women with suspected preeclampsia.

Any one of several single angiogenesis-related biomarkers can be a useful diagnostic test for preeclampsia, wrote Suzy Duckworth, MBBS, of King’s College London and her colleagues. In a prospective, observational study of 423 women with suspected preeclampsia, the researchers found that a combination of biomarkers including placental growth factor (PlGF) was not significantly better than PlGF alone (receiver operating curve area of 0.90 and 0.87, respectively) for predicting preeclampsia requiring delivery within 14 days. Two other single markers, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and endoglin, yielded similar results; each demonstrated a receiver operating curve area of 0.83.

“It is currently difficult to distinguish preeclampsia of a severity that requires early delivery from other less serious phenotypes,” the researchers wrote. “An accurate biomarker (or panel of biomarkers) to enable prognosis of perinatal complications could have a substantial effect on management strategies, with the aim of minimizing adverse maternal and fetal outcomes,” they wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:245-252. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001508).

Dr. Duckworth had no financial conflicts to disclose, but several of her coauthors disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies and one coauthor is a minority shareholder in Metabolomic Diagnostics, a company with an interest in preeclampsia biomarkers.

In another study including 1,041 women with suspected preeclampsia, those with a sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 were nearly three times as likely to deliver on the day of the test than women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less, wrote Harald Zeisler, MD, of Medical University Vienna and his colleagues (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:261-269. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001525).

Women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 also had significantly shorter remaining times to delivery than women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less (median 17 days vs. 51 days). The study was a secondary analysis of an observational cohort study of women aged 18 years and older from 24 to 36 6/7 weeks’ gestation.

In a preterm birth analysis of 848 women, 71% of the 184 women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio greater than 38 had a preterm delivery, compared with 18% of the 664 women with an sFlt-1:PlGF ratio of 38 or less.

The future clinical use of the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio “may potentially assist in informing the health care team of an impending risk to the mother, fetus, or both that may require further assessment and medical intervention,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Zeisler and several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies, including Roche Diagnostics, which sponsored the study.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

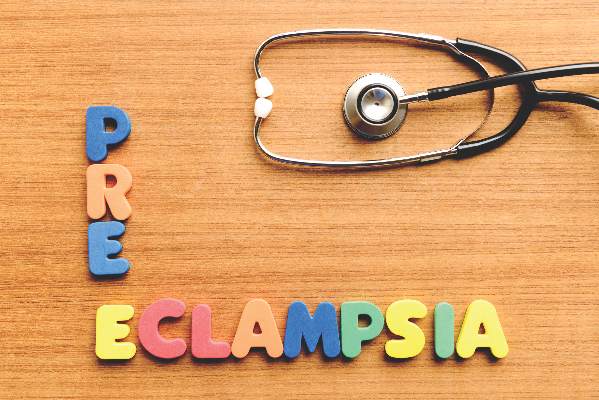

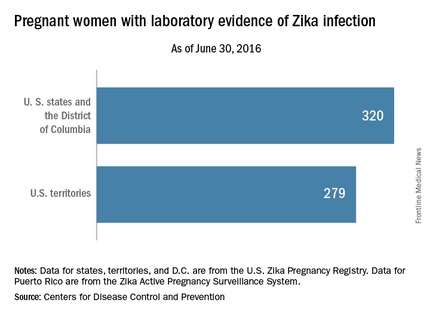

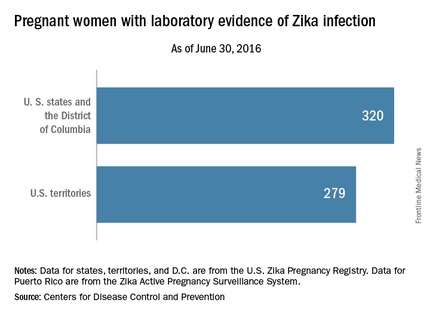

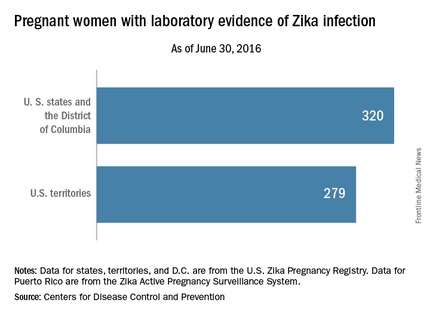

Number of U.S. Zika cases in pregnant women nears 600

There was one Zika-related pregnancy loss in the United States during the week ending June 30, 2016, bringing the total to six pregnancy losses and seven infants born with birth defects that may be related to maternal Zika virus infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The one pregnancy loss for the week occurred in 1 of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Of the 13 adverse events so far, 12 occurred in the 50 states or D.C., and 1 occurred in a U.S. territory, the CDC reported on July 7. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

For the week ending June 30, there were 33 new reports of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection in the 50 states and D.C., for a total of 320 for the year. Among U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, there were 29 new reports, bringing the total to 279 for the territories and 599 for the entire country, the CDC said.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

These are not real time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

There was one Zika-related pregnancy loss in the United States during the week ending June 30, 2016, bringing the total to six pregnancy losses and seven infants born with birth defects that may be related to maternal Zika virus infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The one pregnancy loss for the week occurred in 1 of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Of the 13 adverse events so far, 12 occurred in the 50 states or D.C., and 1 occurred in a U.S. territory, the CDC reported on July 7. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

For the week ending June 30, there were 33 new reports of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection in the 50 states and D.C., for a total of 320 for the year. Among U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, there were 29 new reports, bringing the total to 279 for the territories and 599 for the entire country, the CDC said.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

These are not real time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

There was one Zika-related pregnancy loss in the United States during the week ending June 30, 2016, bringing the total to six pregnancy losses and seven infants born with birth defects that may be related to maternal Zika virus infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The one pregnancy loss for the week occurred in 1 of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Of the 13 adverse events so far, 12 occurred in the 50 states or D.C., and 1 occurred in a U.S. territory, the CDC reported on July 7. State- or territorial-level data are not being reported to protect the privacy of affected women and children.

For the week ending June 30, there were 33 new reports of pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection in the 50 states and D.C., for a total of 320 for the year. Among U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, there were 29 new reports, bringing the total to 279 for the territories and 599 for the entire country, the CDC said.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

These are not real time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Sleep apnea in pregnancy linked to preterm birth

DENVER – Pregnant women with sleep apnea are more likely to have planned obstetric interventions, results of an Australian population-based cohort study suggest.

The study included all 636,227 in-hospital births during 2002-2012 in New South Wales, Australia’s most populous state. Maternal sleep apnea was also associated with increased rates of planned preterm birth, even though preterm birth is widely considered the greatest contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality, Yu Sun Bin, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

“Somewhere along the line, clinicians decided that the risks of preterm birth to the baby were outweighed by the risks to the mother of delivering at term,” said Dr. Bin of the University of Sydney.

She and her coinvestigators undertook this study because even though previous studies have linked maternal sleep apnea to increased risks of gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension, most of the prior studies were small, cross-sectional, and/or relied upon snoring as a proxy for sleep apnea, which many sleep specialists consider invalid.

The investigators compared maternal and infant outcomes for mothers with a documented diagnosis of sleep apnea – either central or obstructive – in the year before or during pregnancy with outcomes for mothers without that diagnosis.

There were 519 mothers with diagnosed sleep apnea, for a prevalence of 0.08%. That figure is low in light of other evidence, making it likely that the 635,708 women in the no-sleep-apnea group actually included a substantial number of mothers with undiagnosed sleep apnea. Thus, the investigators’ estimates of the adverse impacts of sleep apnea in pregnancy are “rather conservative,” according to Dr. Bin.

Australian women with sleep apnea were older and less healthy than mothers without sleep apnea were. They had higher baseline rates of obesity, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, and were more likely to be smokers.

The incidence of pregnancy hypertension was 19.7% in the sleep apnea group and 8.7% in controls. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the maternal sleep apnea group had a 40% greater risk of developing hypertension than did controls. However, contrary to previous smaller studies, they did not have a significantly increased rate of gestational diabetes.

Even after controlling for both pregnancy hypertension and gestational diabetes, the sleep apnea group still had a significant 15% increase in the relative likelihood of a planned delivery.

The rate of preterm birth at 36 weeks or earlier was 14.5% in the maternal sleep apnea group, compared with 6.9% in controls, for an adjusted 1.5-fold increased relative risk.

Perinatal death occurred in 1.9% of the sleep apnea group and 0.9% of controls; however, the resultant adjusted 1.73-fold increased risk didn’t attain statistical significance because of the small number of deaths in the study. Dr. Bin said she and her colleagues plan to further investigate this signal to learn whether it is real or an artifact of small numbers.

The incidence of 5-minute Apgar scores below 7 was 4.6% in the sleep apnea group, compared with 2.4% in controls, for an adjusted 1.6-fold increased risk. The rate of neonatal intensive care unit admission in the sleep apnea group was 27.9%, versus 16% in controls, for a 1.61-fold increased relative risk.

The NICU admission rate for preterm infants didn’t differ between the two groups. The difference occurred in term babies, whose NICU admission rate was 20.3% if they were in the sleep apnea group, but just 12.1% in the control group.

“This suggests that maternal sleep apnea is contributing to some condition in the baby that requires additional support,” Dr. Bin observed.

The nature of that condition, however, remains unclear, since all patient data available to the investigators was deidentified.

The incidence of small-for-gestational-age babies was similar in the sleep apnea and control groups. In contrast, the large-for-gestational-age rate was 15.2% in the sleep apnea group, compared with 9.1% in controls, for an adjusted 1.27-fold increased risk.

The two main limitations of the Australian study were the likely underdiagnosis of sleep apnea and the lack of any information on treatment of affected patients, according to Dr. Bin. A key unresolved question, she added, is whether interventions for maternal sleep apnea reduce the risks identified in the New South Wales study. She noted that one 16-patient randomized study of nasal continuous positive airway pressure suggests the answer is yes (Sleep Med. 2007 Dec;9:15-21).

The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council supported the study. Dr. Bin reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pregnant women with sleep apnea are more likely to have planned obstetric interventions, results of an Australian population-based cohort study suggest.

The study included all 636,227 in-hospital births during 2002-2012 in New South Wales, Australia’s most populous state. Maternal sleep apnea was also associated with increased rates of planned preterm birth, even though preterm birth is widely considered the greatest contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality, Yu Sun Bin, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

“Somewhere along the line, clinicians decided that the risks of preterm birth to the baby were outweighed by the risks to the mother of delivering at term,” said Dr. Bin of the University of Sydney.

She and her coinvestigators undertook this study because even though previous studies have linked maternal sleep apnea to increased risks of gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension, most of the prior studies were small, cross-sectional, and/or relied upon snoring as a proxy for sleep apnea, which many sleep specialists consider invalid.

The investigators compared maternal and infant outcomes for mothers with a documented diagnosis of sleep apnea – either central or obstructive – in the year before or during pregnancy with outcomes for mothers without that diagnosis.

There were 519 mothers with diagnosed sleep apnea, for a prevalence of 0.08%. That figure is low in light of other evidence, making it likely that the 635,708 women in the no-sleep-apnea group actually included a substantial number of mothers with undiagnosed sleep apnea. Thus, the investigators’ estimates of the adverse impacts of sleep apnea in pregnancy are “rather conservative,” according to Dr. Bin.

Australian women with sleep apnea were older and less healthy than mothers without sleep apnea were. They had higher baseline rates of obesity, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, and were more likely to be smokers.

The incidence of pregnancy hypertension was 19.7% in the sleep apnea group and 8.7% in controls. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the maternal sleep apnea group had a 40% greater risk of developing hypertension than did controls. However, contrary to previous smaller studies, they did not have a significantly increased rate of gestational diabetes.

Even after controlling for both pregnancy hypertension and gestational diabetes, the sleep apnea group still had a significant 15% increase in the relative likelihood of a planned delivery.

The rate of preterm birth at 36 weeks or earlier was 14.5% in the maternal sleep apnea group, compared with 6.9% in controls, for an adjusted 1.5-fold increased relative risk.

Perinatal death occurred in 1.9% of the sleep apnea group and 0.9% of controls; however, the resultant adjusted 1.73-fold increased risk didn’t attain statistical significance because of the small number of deaths in the study. Dr. Bin said she and her colleagues plan to further investigate this signal to learn whether it is real or an artifact of small numbers.

The incidence of 5-minute Apgar scores below 7 was 4.6% in the sleep apnea group, compared with 2.4% in controls, for an adjusted 1.6-fold increased risk. The rate of neonatal intensive care unit admission in the sleep apnea group was 27.9%, versus 16% in controls, for a 1.61-fold increased relative risk.

The NICU admission rate for preterm infants didn’t differ between the two groups. The difference occurred in term babies, whose NICU admission rate was 20.3% if they were in the sleep apnea group, but just 12.1% in the control group.

“This suggests that maternal sleep apnea is contributing to some condition in the baby that requires additional support,” Dr. Bin observed.

The nature of that condition, however, remains unclear, since all patient data available to the investigators was deidentified.

The incidence of small-for-gestational-age babies was similar in the sleep apnea and control groups. In contrast, the large-for-gestational-age rate was 15.2% in the sleep apnea group, compared with 9.1% in controls, for an adjusted 1.27-fold increased risk.

The two main limitations of the Australian study were the likely underdiagnosis of sleep apnea and the lack of any information on treatment of affected patients, according to Dr. Bin. A key unresolved question, she added, is whether interventions for maternal sleep apnea reduce the risks identified in the New South Wales study. She noted that one 16-patient randomized study of nasal continuous positive airway pressure suggests the answer is yes (Sleep Med. 2007 Dec;9:15-21).

The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council supported the study. Dr. Bin reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pregnant women with sleep apnea are more likely to have planned obstetric interventions, results of an Australian population-based cohort study suggest.

The study included all 636,227 in-hospital births during 2002-2012 in New South Wales, Australia’s most populous state. Maternal sleep apnea was also associated with increased rates of planned preterm birth, even though preterm birth is widely considered the greatest contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality, Yu Sun Bin, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

“Somewhere along the line, clinicians decided that the risks of preterm birth to the baby were outweighed by the risks to the mother of delivering at term,” said Dr. Bin of the University of Sydney.

She and her coinvestigators undertook this study because even though previous studies have linked maternal sleep apnea to increased risks of gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension, most of the prior studies were small, cross-sectional, and/or relied upon snoring as a proxy for sleep apnea, which many sleep specialists consider invalid.

The investigators compared maternal and infant outcomes for mothers with a documented diagnosis of sleep apnea – either central or obstructive – in the year before or during pregnancy with outcomes for mothers without that diagnosis.

There were 519 mothers with diagnosed sleep apnea, for a prevalence of 0.08%. That figure is low in light of other evidence, making it likely that the 635,708 women in the no-sleep-apnea group actually included a substantial number of mothers with undiagnosed sleep apnea. Thus, the investigators’ estimates of the adverse impacts of sleep apnea in pregnancy are “rather conservative,” according to Dr. Bin.

Australian women with sleep apnea were older and less healthy than mothers without sleep apnea were. They had higher baseline rates of obesity, preexisting diabetes, chronic hypertension, and were more likely to be smokers.

The incidence of pregnancy hypertension was 19.7% in the sleep apnea group and 8.7% in controls. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the maternal sleep apnea group had a 40% greater risk of developing hypertension than did controls. However, contrary to previous smaller studies, they did not have a significantly increased rate of gestational diabetes.

Even after controlling for both pregnancy hypertension and gestational diabetes, the sleep apnea group still had a significant 15% increase in the relative likelihood of a planned delivery.

The rate of preterm birth at 36 weeks or earlier was 14.5% in the maternal sleep apnea group, compared with 6.9% in controls, for an adjusted 1.5-fold increased relative risk.

Perinatal death occurred in 1.9% of the sleep apnea group and 0.9% of controls; however, the resultant adjusted 1.73-fold increased risk didn’t attain statistical significance because of the small number of deaths in the study. Dr. Bin said she and her colleagues plan to further investigate this signal to learn whether it is real or an artifact of small numbers.

The incidence of 5-minute Apgar scores below 7 was 4.6% in the sleep apnea group, compared with 2.4% in controls, for an adjusted 1.6-fold increased risk. The rate of neonatal intensive care unit admission in the sleep apnea group was 27.9%, versus 16% in controls, for a 1.61-fold increased relative risk.

The NICU admission rate for preterm infants didn’t differ between the two groups. The difference occurred in term babies, whose NICU admission rate was 20.3% if they were in the sleep apnea group, but just 12.1% in the control group.

“This suggests that maternal sleep apnea is contributing to some condition in the baby that requires additional support,” Dr. Bin observed.

The nature of that condition, however, remains unclear, since all patient data available to the investigators was deidentified.

The incidence of small-for-gestational-age babies was similar in the sleep apnea and control groups. In contrast, the large-for-gestational-age rate was 15.2% in the sleep apnea group, compared with 9.1% in controls, for an adjusted 1.27-fold increased risk.

The two main limitations of the Australian study were the likely underdiagnosis of sleep apnea and the lack of any information on treatment of affected patients, according to Dr. Bin. A key unresolved question, she added, is whether interventions for maternal sleep apnea reduce the risks identified in the New South Wales study. She noted that one 16-patient randomized study of nasal continuous positive airway pressure suggests the answer is yes (Sleep Med. 2007 Dec;9:15-21).

The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council supported the study. Dr. Bin reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SLEEP 2016

Key clinical point: Maternal sleep apnea is associated with increased rates of obstetric intervention and preterm birth.

Major finding: The rate of preterm birth at 36 weeks or earlier was 14.5% in the group with maternal sleep apnea, compared with 6.9% in controls.

Data source: A population-based cohort study of 636,227 women who gave birth in a New South Wales, Australia, hospital during 2002-2012.

Disclosures: The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council supported the study. Dr. Bin reported having no financial conflicts.

Zika study to focus on U.S. Olympic athletes

Zika virus exposure will be monitored by researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health during the 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in Rio De Janeiro.