User login

17P Failed to Help Women With 'Longer Short Cervix'

DALLAS – The drug 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, or 17P, is not effective for reducing the risk of preterm delivery in nulliparous women with a cervix length less than the 10th percentile, findings from a randomized placebo-controlled study involving 657 women have shown.

Based on findings from prior studies, 17P is indicated in women with a cervical length of 10-20 mm, which represents only a very small proportion of patients. The objective of the current study was to determine if the benefits of 17P might extend to those with a "longer short cervix," Dr. William Grobman said at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"Using a cervical length cutoff of the 10th percentile potentially expands the benefits of progesterone to a larger proportion of the population," said Dr. Grobman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was speaking on behalf of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

Between 16 and 22 weeks’ gestation, when routine anatomic surveys are performed, the 10th percentile for cervical length is 30 mm, he explained.

Of 15,436 women screened at the 14 centers that are part of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, 1,588 had a cervical length of less than 30 mm, and 657 consented to randomization. The frequency of preterm birth, defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, was 25.1% in 327 women randomized to receive 17P, and 24.5% in the 330 who received placebo.

There also were no differences in the rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks and less than 28 weeks, and no difference in the survival curve – defined as the number of days the women remained pregnant following 17P injection, Dr. Grobman said.

Based on these findings, enrollment in the study was stopped at the third interim analysis, he noted.

As for neonatal outcomes, no difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups in regard to a composite outcome including, but not limited to, respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity, and perinatal death.

When neonatal outcomes were analyzed individually, a significant difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups with regard to sepsis; those in the 17P group had a lower risk of developing sepsis, Dr. Grobman noted.

Women in this study had a singleton pregnancy, and were screened between 16 and 223/7 weeks by a certified sonographer. They had no major fetal anomalies, no increased probability of indicated preterm birth, and no prior loop electrosurgical excision procedure or müllerian anomalies.

Those who consented to participate received an injection of 1 mL of placebo, and those who returned at least 3 days later but before 23 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive 250 mg of intramuscular 17P weekly, or identically appearing placebo. All received weekly injections until delivery or 37 weeks.

Those in the treatment group were slightly, but significantly older. All other characteristics, including body mass index, race/ethnicity, and estimated gestational age at randomization were similar in the treatment and placebo groups.

The mean cervical length was 24 mm in both groups; less than 10% had a cervical length less than 15 mm, and less than 20% of those had the cervical funnel visualized, Dr. Grobman said.

"Based on these data, we do conclude that weekly intramuscular 17P does not reduce the frequency of preterm birth in nulliparous women with a cervix less than 30 mm," he concluded.

"This is really a study more than anything of women with a longer short cervix," he added, explaining during a question and answer session that the study isn’t powered to look at outcomes for those with other cervical lengths, for example, less than 20 mm or less than 15 mm. About 85% of women in this study had a cervical length between 25 and 30 mm.

Dr. Grobman said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

DALLAS – The drug 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, or 17P, is not effective for reducing the risk of preterm delivery in nulliparous women with a cervix length less than the 10th percentile, findings from a randomized placebo-controlled study involving 657 women have shown.

Based on findings from prior studies, 17P is indicated in women with a cervical length of 10-20 mm, which represents only a very small proportion of patients. The objective of the current study was to determine if the benefits of 17P might extend to those with a "longer short cervix," Dr. William Grobman said at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"Using a cervical length cutoff of the 10th percentile potentially expands the benefits of progesterone to a larger proportion of the population," said Dr. Grobman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was speaking on behalf of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

Between 16 and 22 weeks’ gestation, when routine anatomic surveys are performed, the 10th percentile for cervical length is 30 mm, he explained.

Of 15,436 women screened at the 14 centers that are part of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, 1,588 had a cervical length of less than 30 mm, and 657 consented to randomization. The frequency of preterm birth, defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, was 25.1% in 327 women randomized to receive 17P, and 24.5% in the 330 who received placebo.

There also were no differences in the rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks and less than 28 weeks, and no difference in the survival curve – defined as the number of days the women remained pregnant following 17P injection, Dr. Grobman said.

Based on these findings, enrollment in the study was stopped at the third interim analysis, he noted.

As for neonatal outcomes, no difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups in regard to a composite outcome including, but not limited to, respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity, and perinatal death.

When neonatal outcomes were analyzed individually, a significant difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups with regard to sepsis; those in the 17P group had a lower risk of developing sepsis, Dr. Grobman noted.

Women in this study had a singleton pregnancy, and were screened between 16 and 223/7 weeks by a certified sonographer. They had no major fetal anomalies, no increased probability of indicated preterm birth, and no prior loop electrosurgical excision procedure or müllerian anomalies.

Those who consented to participate received an injection of 1 mL of placebo, and those who returned at least 3 days later but before 23 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive 250 mg of intramuscular 17P weekly, or identically appearing placebo. All received weekly injections until delivery or 37 weeks.

Those in the treatment group were slightly, but significantly older. All other characteristics, including body mass index, race/ethnicity, and estimated gestational age at randomization were similar in the treatment and placebo groups.

The mean cervical length was 24 mm in both groups; less than 10% had a cervical length less than 15 mm, and less than 20% of those had the cervical funnel visualized, Dr. Grobman said.

"Based on these data, we do conclude that weekly intramuscular 17P does not reduce the frequency of preterm birth in nulliparous women with a cervix less than 30 mm," he concluded.

"This is really a study more than anything of women with a longer short cervix," he added, explaining during a question and answer session that the study isn’t powered to look at outcomes for those with other cervical lengths, for example, less than 20 mm or less than 15 mm. About 85% of women in this study had a cervical length between 25 and 30 mm.

Dr. Grobman said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

DALLAS – The drug 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, or 17P, is not effective for reducing the risk of preterm delivery in nulliparous women with a cervix length less than the 10th percentile, findings from a randomized placebo-controlled study involving 657 women have shown.

Based on findings from prior studies, 17P is indicated in women with a cervical length of 10-20 mm, which represents only a very small proportion of patients. The objective of the current study was to determine if the benefits of 17P might extend to those with a "longer short cervix," Dr. William Grobman said at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

"Using a cervical length cutoff of the 10th percentile potentially expands the benefits of progesterone to a larger proportion of the population," said Dr. Grobman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was speaking on behalf of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

Between 16 and 22 weeks’ gestation, when routine anatomic surveys are performed, the 10th percentile for cervical length is 30 mm, he explained.

Of 15,436 women screened at the 14 centers that are part of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, 1,588 had a cervical length of less than 30 mm, and 657 consented to randomization. The frequency of preterm birth, defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, was 25.1% in 327 women randomized to receive 17P, and 24.5% in the 330 who received placebo.

There also were no differences in the rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks and less than 28 weeks, and no difference in the survival curve – defined as the number of days the women remained pregnant following 17P injection, Dr. Grobman said.

Based on these findings, enrollment in the study was stopped at the third interim analysis, he noted.

As for neonatal outcomes, no difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups in regard to a composite outcome including, but not limited to, respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity, and perinatal death.

When neonatal outcomes were analyzed individually, a significant difference was seen between the treatment and placebo groups with regard to sepsis; those in the 17P group had a lower risk of developing sepsis, Dr. Grobman noted.

Women in this study had a singleton pregnancy, and were screened between 16 and 223/7 weeks by a certified sonographer. They had no major fetal anomalies, no increased probability of indicated preterm birth, and no prior loop electrosurgical excision procedure or müllerian anomalies.

Those who consented to participate received an injection of 1 mL of placebo, and those who returned at least 3 days later but before 23 weeks’ gestation were randomized to receive 250 mg of intramuscular 17P weekly, or identically appearing placebo. All received weekly injections until delivery or 37 weeks.

Those in the treatment group were slightly, but significantly older. All other characteristics, including body mass index, race/ethnicity, and estimated gestational age at randomization were similar in the treatment and placebo groups.

The mean cervical length was 24 mm in both groups; less than 10% had a cervical length less than 15 mm, and less than 20% of those had the cervical funnel visualized, Dr. Grobman said.

"Based on these data, we do conclude that weekly intramuscular 17P does not reduce the frequency of preterm birth in nulliparous women with a cervix less than 30 mm," he concluded.

"This is really a study more than anything of women with a longer short cervix," he added, explaining during a question and answer session that the study isn’t powered to look at outcomes for those with other cervical lengths, for example, less than 20 mm or less than 15 mm. About 85% of women in this study had a cervical length between 25 and 30 mm.

Dr. Grobman said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY FOR MATERNAL-FETAL MEDICINE

Major Finding: The frequency of preterm birth, defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, was 25.1% in 327 women randomized to receive 17P, and 24.5% in the 330 who received placebo. The mean cervical length was 24 mm in both groups.

Data Source: This was a randomized placebo-controlled trial of 657 pregnant women who were part of the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

Disclosures: Dr. Grobman said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Pregnancy Does Not Preclude Safe DVT Treatment

MIAMI BEACH – Women who develop a deep vein thrombosis while pregnant can safely undergo removal of the clot without jeopardizing their pregnancy, based on a recent experience with 11 cases at one U.S. center.

"Not many vascular surgeons are willing to perform thrombectomy in pregnant women, and most physicians fear thrombolytic therapy in pregnant patients," Dr. Anthony J. Comerota said at ISET 2012, an international symposium on endovascular therapy.

But in reality, there is no evidence that thrombolysis poses any special risk during pregnancy, in part because the drugs that are usually used – urokinase, streptokinase, or tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) – do not cross the placenta, and therefore do not exert any fibrinolytic effect on a fetus, he said. In addition, the relatively recent introduction of pharmacomechanical methods for thrombolysis have "accelerated our enthusiasm and strengthened our confidence that this is an effective and safe strategy for treating extensive DVT [deep vein thrombosis] during pregnancy," said Dr. Comerota, a vascular surgeon and director of the Jobst Vascular Institute in Toledo, Ohio.

"Pregnancy need not be a major contraindication for successful management of extensive DVT. We need to minimize radiation, monitor the fetus, and control uterine contractions, but we should treat healthy, pregnant women [who have] a DVT the same way we treat healthy nonpregnant women" who have a DVT, he said in an interview. "The extraordinary concern for risk to the pregnancy [from clot removal] seems substantially overstated."

Because pregnancy produces a prothrombotic state, the risk that a healthy, pregnant woman has for DVT is about sixfold higher than her risk when not pregnant. Until now, most physicians deferred endovascular or surgical management of women who develop a DVT during pregnancy, and have relied exclusively on medical treatment with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, a strategy that is often ineffective.

"What pushed me to treat women earlier during their pregnancy was that I saw patients who did not receive therapy until after delivery, and by then the clot became more organized – a mix of collagen and scar inside the vein – -and caused severe postthrombotic disability," Dr. Comerota said.

Recently, he treated 11 pregnant women (10 with an iliofemoral thrombosis and 1 with the clot in her superior vena cava). One woman was in the first trimester, two were in the second, and eight were in the third trimester. Three patients underwent clot removal by open surgery, with the other eight treated by endovascular methods, including six who were treated with catheter-delivered TPA and one who received urokinase via catheter. Other endovascular tools that were used as needed included ultrasound clot treatment and rheolytic thrombectomy. In all cases, these treatments successfully removed the clot. One women developed hematuria and required a transfusion following her clot removal, and another patient developed a popliteal artery pseudoaneurysm. None of the patients had a recurrent DVT; two developed mild postthrombotic symptoms.

In one case, the fetus spontaneously aborted 5 days after the procedure secondary to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, which had also triggered the thrombosis. The other 10 cases resulted in successful pregnancies and live deliveries, one surgically and the other nine vaginally. Three of the women had successful subsequent pregnancies, Dr. Comerota said.

Dr. Comerota said that he has been a speaker for and a consultant to Covidien, a company that makes some of the devices used in these procedures.

MIAMI BEACH – Women who develop a deep vein thrombosis while pregnant can safely undergo removal of the clot without jeopardizing their pregnancy, based on a recent experience with 11 cases at one U.S. center.

"Not many vascular surgeons are willing to perform thrombectomy in pregnant women, and most physicians fear thrombolytic therapy in pregnant patients," Dr. Anthony J. Comerota said at ISET 2012, an international symposium on endovascular therapy.

But in reality, there is no evidence that thrombolysis poses any special risk during pregnancy, in part because the drugs that are usually used – urokinase, streptokinase, or tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) – do not cross the placenta, and therefore do not exert any fibrinolytic effect on a fetus, he said. In addition, the relatively recent introduction of pharmacomechanical methods for thrombolysis have "accelerated our enthusiasm and strengthened our confidence that this is an effective and safe strategy for treating extensive DVT [deep vein thrombosis] during pregnancy," said Dr. Comerota, a vascular surgeon and director of the Jobst Vascular Institute in Toledo, Ohio.

"Pregnancy need not be a major contraindication for successful management of extensive DVT. We need to minimize radiation, monitor the fetus, and control uterine contractions, but we should treat healthy, pregnant women [who have] a DVT the same way we treat healthy nonpregnant women" who have a DVT, he said in an interview. "The extraordinary concern for risk to the pregnancy [from clot removal] seems substantially overstated."

Because pregnancy produces a prothrombotic state, the risk that a healthy, pregnant woman has for DVT is about sixfold higher than her risk when not pregnant. Until now, most physicians deferred endovascular or surgical management of women who develop a DVT during pregnancy, and have relied exclusively on medical treatment with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, a strategy that is often ineffective.

"What pushed me to treat women earlier during their pregnancy was that I saw patients who did not receive therapy until after delivery, and by then the clot became more organized – a mix of collagen and scar inside the vein – -and caused severe postthrombotic disability," Dr. Comerota said.

Recently, he treated 11 pregnant women (10 with an iliofemoral thrombosis and 1 with the clot in her superior vena cava). One woman was in the first trimester, two were in the second, and eight were in the third trimester. Three patients underwent clot removal by open surgery, with the other eight treated by endovascular methods, including six who were treated with catheter-delivered TPA and one who received urokinase via catheter. Other endovascular tools that were used as needed included ultrasound clot treatment and rheolytic thrombectomy. In all cases, these treatments successfully removed the clot. One women developed hematuria and required a transfusion following her clot removal, and another patient developed a popliteal artery pseudoaneurysm. None of the patients had a recurrent DVT; two developed mild postthrombotic symptoms.

In one case, the fetus spontaneously aborted 5 days after the procedure secondary to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, which had also triggered the thrombosis. The other 10 cases resulted in successful pregnancies and live deliveries, one surgically and the other nine vaginally. Three of the women had successful subsequent pregnancies, Dr. Comerota said.

Dr. Comerota said that he has been a speaker for and a consultant to Covidien, a company that makes some of the devices used in these procedures.

MIAMI BEACH – Women who develop a deep vein thrombosis while pregnant can safely undergo removal of the clot without jeopardizing their pregnancy, based on a recent experience with 11 cases at one U.S. center.

"Not many vascular surgeons are willing to perform thrombectomy in pregnant women, and most physicians fear thrombolytic therapy in pregnant patients," Dr. Anthony J. Comerota said at ISET 2012, an international symposium on endovascular therapy.

But in reality, there is no evidence that thrombolysis poses any special risk during pregnancy, in part because the drugs that are usually used – urokinase, streptokinase, or tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) – do not cross the placenta, and therefore do not exert any fibrinolytic effect on a fetus, he said. In addition, the relatively recent introduction of pharmacomechanical methods for thrombolysis have "accelerated our enthusiasm and strengthened our confidence that this is an effective and safe strategy for treating extensive DVT [deep vein thrombosis] during pregnancy," said Dr. Comerota, a vascular surgeon and director of the Jobst Vascular Institute in Toledo, Ohio.

"Pregnancy need not be a major contraindication for successful management of extensive DVT. We need to minimize radiation, monitor the fetus, and control uterine contractions, but we should treat healthy, pregnant women [who have] a DVT the same way we treat healthy nonpregnant women" who have a DVT, he said in an interview. "The extraordinary concern for risk to the pregnancy [from clot removal] seems substantially overstated."

Because pregnancy produces a prothrombotic state, the risk that a healthy, pregnant woman has for DVT is about sixfold higher than her risk when not pregnant. Until now, most physicians deferred endovascular or surgical management of women who develop a DVT during pregnancy, and have relied exclusively on medical treatment with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, a strategy that is often ineffective.

"What pushed me to treat women earlier during their pregnancy was that I saw patients who did not receive therapy until after delivery, and by then the clot became more organized – a mix of collagen and scar inside the vein – -and caused severe postthrombotic disability," Dr. Comerota said.

Recently, he treated 11 pregnant women (10 with an iliofemoral thrombosis and 1 with the clot in her superior vena cava). One woman was in the first trimester, two were in the second, and eight were in the third trimester. Three patients underwent clot removal by open surgery, with the other eight treated by endovascular methods, including six who were treated with catheter-delivered TPA and one who received urokinase via catheter. Other endovascular tools that were used as needed included ultrasound clot treatment and rheolytic thrombectomy. In all cases, these treatments successfully removed the clot. One women developed hematuria and required a transfusion following her clot removal, and another patient developed a popliteal artery pseudoaneurysm. None of the patients had a recurrent DVT; two developed mild postthrombotic symptoms.

In one case, the fetus spontaneously aborted 5 days after the procedure secondary to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, which had also triggered the thrombosis. The other 10 cases resulted in successful pregnancies and live deliveries, one surgically and the other nine vaginally. Three of the women had successful subsequent pregnancies, Dr. Comerota said.

Dr. Comerota said that he has been a speaker for and a consultant to Covidien, a company that makes some of the devices used in these procedures.

FROM ISET 2012, AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON ENDOVASCULAR THERAPY

Major Finding: Treatment of 11 pregnant women with DVT resulted in 10 successful live births.

Data Source: A retrospective review of 11 cases managed at one U.S. center.

Disclosures: Dr. Comerota said that he has been a speaker for and a consultant to Covidien, a company that makes some of the devices used in these procedures.

Is the hCG discriminatory zone a reliable indicator of intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy?

Often used in the evaluation of early pregnancy, the hCG discriminatory zone is based on the assumption that a serum ß-hCG level exceeding 1,000–2,000 mIU/mL in a woman who has a normal intrauterine pregnancy should be accompanied by a gestational sac that is visible via transvaginal US. When such a sac is not visible in the uterus, many practitioners conclude that the pregnancy is ectopic and tailor management accordingly.

In this study of women who were assessed between the years 2000 and 2010, investigators reviewed the records of those who underwent US and hCG measurement on the same (index) day, had detectable hCG, had no US evidence of intrauterine pregnancy on the index day, and were subsequently found to have a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Among 202 women who met these criteria, the hCG level fell into the following ranges:

- below 1,000 mIU/mL (80.2%)

- 1,000–1,499 mIU/mL (9.4%)

- 1,500–1,999 mIU/mL (5.9%)

- 2,000 mIU/mL or higher (4.5%).

The highest hCG value observed was 6,567 mIU/mL; the highest level of hCG observed in a woman who later delivered a term infant was 4,336 mIU/mL.

A case for abandoning the zone?

Many clinicians (and malpractice attorneys) are familiar with unfortunate cases of women who underwent uterine curettage or were given methotrexate, based on an hCG level found to be in the discriminatory zone without accompanying evidence of intrauterine pregnancy, only to lose what was, in fact, a potentially viable pregnancy.

By demonstrating the high variability in hCG levels among women who had early intrauterine pregnancy without definitive findings on US, the authors make a strong case for abandoning the concept of the discriminatory zone altogether.

Women’s health providers often encounter hemodynamically stable patients who have early pregnancy of unknown viability or implantation site and who lack ultrasonographic (US) evidence of hemoperitoneum. It is not appropriate to perform uterine curettage or administer methotrexate in this setting. Instead, counsel these patients that the earliness of the pregnancy precludes definitive assessment of gestational status. Review with the patient the signs and symptoms of ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and arrange for follow-up hCG measurement and US assessment.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Often used in the evaluation of early pregnancy, the hCG discriminatory zone is based on the assumption that a serum ß-hCG level exceeding 1,000–2,000 mIU/mL in a woman who has a normal intrauterine pregnancy should be accompanied by a gestational sac that is visible via transvaginal US. When such a sac is not visible in the uterus, many practitioners conclude that the pregnancy is ectopic and tailor management accordingly.

In this study of women who were assessed between the years 2000 and 2010, investigators reviewed the records of those who underwent US and hCG measurement on the same (index) day, had detectable hCG, had no US evidence of intrauterine pregnancy on the index day, and were subsequently found to have a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Among 202 women who met these criteria, the hCG level fell into the following ranges:

- below 1,000 mIU/mL (80.2%)

- 1,000–1,499 mIU/mL (9.4%)

- 1,500–1,999 mIU/mL (5.9%)

- 2,000 mIU/mL or higher (4.5%).

The highest hCG value observed was 6,567 mIU/mL; the highest level of hCG observed in a woman who later delivered a term infant was 4,336 mIU/mL.

A case for abandoning the zone?

Many clinicians (and malpractice attorneys) are familiar with unfortunate cases of women who underwent uterine curettage or were given methotrexate, based on an hCG level found to be in the discriminatory zone without accompanying evidence of intrauterine pregnancy, only to lose what was, in fact, a potentially viable pregnancy.

By demonstrating the high variability in hCG levels among women who had early intrauterine pregnancy without definitive findings on US, the authors make a strong case for abandoning the concept of the discriminatory zone altogether.

Women’s health providers often encounter hemodynamically stable patients who have early pregnancy of unknown viability or implantation site and who lack ultrasonographic (US) evidence of hemoperitoneum. It is not appropriate to perform uterine curettage or administer methotrexate in this setting. Instead, counsel these patients that the earliness of the pregnancy precludes definitive assessment of gestational status. Review with the patient the signs and symptoms of ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and arrange for follow-up hCG measurement and US assessment.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Often used in the evaluation of early pregnancy, the hCG discriminatory zone is based on the assumption that a serum ß-hCG level exceeding 1,000–2,000 mIU/mL in a woman who has a normal intrauterine pregnancy should be accompanied by a gestational sac that is visible via transvaginal US. When such a sac is not visible in the uterus, many practitioners conclude that the pregnancy is ectopic and tailor management accordingly.

In this study of women who were assessed between the years 2000 and 2010, investigators reviewed the records of those who underwent US and hCG measurement on the same (index) day, had detectable hCG, had no US evidence of intrauterine pregnancy on the index day, and were subsequently found to have a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Among 202 women who met these criteria, the hCG level fell into the following ranges:

- below 1,000 mIU/mL (80.2%)

- 1,000–1,499 mIU/mL (9.4%)

- 1,500–1,999 mIU/mL (5.9%)

- 2,000 mIU/mL or higher (4.5%).

The highest hCG value observed was 6,567 mIU/mL; the highest level of hCG observed in a woman who later delivered a term infant was 4,336 mIU/mL.

A case for abandoning the zone?

Many clinicians (and malpractice attorneys) are familiar with unfortunate cases of women who underwent uterine curettage or were given methotrexate, based on an hCG level found to be in the discriminatory zone without accompanying evidence of intrauterine pregnancy, only to lose what was, in fact, a potentially viable pregnancy.

By demonstrating the high variability in hCG levels among women who had early intrauterine pregnancy without definitive findings on US, the authors make a strong case for abandoning the concept of the discriminatory zone altogether.

Women’s health providers often encounter hemodynamically stable patients who have early pregnancy of unknown viability or implantation site and who lack ultrasonographic (US) evidence of hemoperitoneum. It is not appropriate to perform uterine curettage or administer methotrexate in this setting. Instead, counsel these patients that the earliness of the pregnancy precludes definitive assessment of gestational status. Review with the patient the signs and symptoms of ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and arrange for follow-up hCG measurement and US assessment.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Pregnant Women With Lymphoma Can Have Good Outcomes

SAN DIEGO – Women diagnosed with lymphoma during pregnancy stand a good chance of carrying a healthy child to term even when they opt for treatment during the second or third trimester, according to a retrospective multicenter analysis.

Among 82 women diagnosed with either Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma during pregnancy, 48 opted to start therapy during pregnancy rather than defer it until after delivery, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

All but one woman had a normal birth, the exception being a severe malformation: microcephaly in the fetus of a woman who had received four cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The timing of therapy did not appear to affect overall survival, with the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate being 76% among women who underwent treatment during pregnancy, compared with 79% for those who deferred it, said Dr. Andrew M. Evens of the University of Massachusetts in Worcester.

Respective overall survival rates were 92% and 83%, he reported. For the six women who elected to terminate their pregnancies, the 3-year PFS rate and overall survival rate were each 100%.

Among 39 women with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), the 3-year PFS rate was 90%, and overall survival was 95%. Among 33 patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), 73% were progression free at 3 years; the overall survival rate was 82%. For 10 women with NHL of T-cell histology, the respective figures were 50% and 90%.

"We conclude that standard chemotherapy – non-antimetabolite chemotherapy – and radiation in select cases, in particular localized disease likely above the diaphragm during the second and third trimester, were associated with expected maternal complications and fetal detriment," Dr. Evens said.

Women with low-risk disease, such as indolent NHL, or a diagnosis late in gestation may be able to defer therapy until after delivery, he added.

Cancers in Pregnancy Uncommon. Cancer diagnoses during pregnancy are uncommon, occurring in about 3,500 women annually in the United States. The estimated prevalence is 1 in 1,000 gestations. Hematologic malignancies, primarily lymphomas, account for about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Evens said.

He and his colleagues at nine academic medical centers conducted a descriptive retrospective analysis looking at histology, disease characteristics, therapy received, and maternal and fetal complications among pregnant women diagnosed with lymphomas from 1998 through 2011.

Of the 82 women identified for whom follow-up data were available, 43 (52%) were diagnosed with NHL (83% B-cell and 17% T-cell histologies) and 39 (48%) with HL. The median time of diagnosis was at 24 weeks gestation (range 5-40 weeks).

Six patients (4 with NHL and 2 with HL) decided to terminate the pregnancies to have immediate chemotherapy. Five of these patients were diagnosed in the first trimester and required systemic therapy.

The remaining patient was diagnosed early in the second trimester with lymphoma involving the central nervous system and requiring high-dose methotrexate, an antimetabolite in FDA pregnancy category X (positive evidence of fetal harm from animal or human studies and/or clinical experience; contraindicated). Other antimetabolites are classified in category D (positive evidence of fetal risk, but the benefits may warrant use in pregnant women).

A total of 28 patients (34%) chose to defer therapy, including 15 with HL, 5 with follicular lymphoma, 4 with DLBCL, 3 with T-cell lymphoma, and 1 with Burkitt’s lymphoma. The median gestation time at diagnosis in these patients was 34 weeks (range 6-38).

Of the 48 patients who chose to start therapy during pregnancy, 27 patients with NHL received therapy with CHOP, CHOP plus rituximab (Rituxan), modified hyperCVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone), or similar regimens.

All but 2 patients with HL received the ABVD regimen (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), and 4 of these patients also received partial-dose radiation therapy with shielding of the fetus. One patient received AVD (no bleomycin), and 1 received ChlVPP (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, and prednisone). Treatments ranged from the 13th to the 33rd week of gestation.

Among the 48 treated patients, gestation reached full term in 73% with delivery at a median of 37 weeks (range 31-40); most of the deliveries occurred at or after 35 weeks. Among the 28 patients who deferred therapy, delivery was at a median of 38 weeks (range 26-40), and 86% of these women were able to carry their pregnancies to term.

"The goal in every patient, whether they received therapy or not, was to try and deliver as close to term as possible," Dr. Evens said.

Among all patients, 72% had vaginal delivery, and 28% had cesarean sections.

Labor Induced in Nearly Half of Patients. The most common preterm complication was the need for induction of labor in 45%. Preeclampsia occurred in 8%, 5% had spontaneous rupture of membranes, and 4% had gestational diabetes. There were no reported cases of endometritis or chorioamnionitis. There were no significant differences in preterm events between patients who were treated or deferred therapy.

There was one stillbirth, occurring in a 34-year-old woman with double-hit (two-mutation) NHL at 19 weeks after one cycle of R-CHOP.

One woman died before giving birth. She had very-high-risk DLBCL with significant metastases to the liver. She had been diagnosed at week 29 and died at week 32 from encephalopathy, but delivered a healthy infant before her death.

Outcomes for the fetuses of the 76 women who opted to continue their pregnancies included the aforementioned stillbirth and 1 case of microcephaly in a woman who had received four cycles of CHOP for DLBCL.

The median birth weight of neonates was 2,427 g (range 1,005-5,262 g), and there were no differences between the children of women who underwent antepartum chemotherapy or deferred therapy.

Dr. Evens noted that the investigators looked only at acute fetal outcomes, and have not evaluated long-term developmental measures.

The study was funded by the participating centers. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Women diagnosed with lymphoma during pregnancy stand a good chance of carrying a healthy child to term even when they opt for treatment during the second or third trimester, according to a retrospective multicenter analysis.

Among 82 women diagnosed with either Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma during pregnancy, 48 opted to start therapy during pregnancy rather than defer it until after delivery, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

All but one woman had a normal birth, the exception being a severe malformation: microcephaly in the fetus of a woman who had received four cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The timing of therapy did not appear to affect overall survival, with the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate being 76% among women who underwent treatment during pregnancy, compared with 79% for those who deferred it, said Dr. Andrew M. Evens of the University of Massachusetts in Worcester.

Respective overall survival rates were 92% and 83%, he reported. For the six women who elected to terminate their pregnancies, the 3-year PFS rate and overall survival rate were each 100%.

Among 39 women with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), the 3-year PFS rate was 90%, and overall survival was 95%. Among 33 patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), 73% were progression free at 3 years; the overall survival rate was 82%. For 10 women with NHL of T-cell histology, the respective figures were 50% and 90%.

"We conclude that standard chemotherapy – non-antimetabolite chemotherapy – and radiation in select cases, in particular localized disease likely above the diaphragm during the second and third trimester, were associated with expected maternal complications and fetal detriment," Dr. Evens said.

Women with low-risk disease, such as indolent NHL, or a diagnosis late in gestation may be able to defer therapy until after delivery, he added.

Cancers in Pregnancy Uncommon. Cancer diagnoses during pregnancy are uncommon, occurring in about 3,500 women annually in the United States. The estimated prevalence is 1 in 1,000 gestations. Hematologic malignancies, primarily lymphomas, account for about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Evens said.

He and his colleagues at nine academic medical centers conducted a descriptive retrospective analysis looking at histology, disease characteristics, therapy received, and maternal and fetal complications among pregnant women diagnosed with lymphomas from 1998 through 2011.

Of the 82 women identified for whom follow-up data were available, 43 (52%) were diagnosed with NHL (83% B-cell and 17% T-cell histologies) and 39 (48%) with HL. The median time of diagnosis was at 24 weeks gestation (range 5-40 weeks).

Six patients (4 with NHL and 2 with HL) decided to terminate the pregnancies to have immediate chemotherapy. Five of these patients were diagnosed in the first trimester and required systemic therapy.

The remaining patient was diagnosed early in the second trimester with lymphoma involving the central nervous system and requiring high-dose methotrexate, an antimetabolite in FDA pregnancy category X (positive evidence of fetal harm from animal or human studies and/or clinical experience; contraindicated). Other antimetabolites are classified in category D (positive evidence of fetal risk, but the benefits may warrant use in pregnant women).

A total of 28 patients (34%) chose to defer therapy, including 15 with HL, 5 with follicular lymphoma, 4 with DLBCL, 3 with T-cell lymphoma, and 1 with Burkitt’s lymphoma. The median gestation time at diagnosis in these patients was 34 weeks (range 6-38).

Of the 48 patients who chose to start therapy during pregnancy, 27 patients with NHL received therapy with CHOP, CHOP plus rituximab (Rituxan), modified hyperCVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone), or similar regimens.

All but 2 patients with HL received the ABVD regimen (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), and 4 of these patients also received partial-dose radiation therapy with shielding of the fetus. One patient received AVD (no bleomycin), and 1 received ChlVPP (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, and prednisone). Treatments ranged from the 13th to the 33rd week of gestation.

Among the 48 treated patients, gestation reached full term in 73% with delivery at a median of 37 weeks (range 31-40); most of the deliveries occurred at or after 35 weeks. Among the 28 patients who deferred therapy, delivery was at a median of 38 weeks (range 26-40), and 86% of these women were able to carry their pregnancies to term.

"The goal in every patient, whether they received therapy or not, was to try and deliver as close to term as possible," Dr. Evens said.

Among all patients, 72% had vaginal delivery, and 28% had cesarean sections.

Labor Induced in Nearly Half of Patients. The most common preterm complication was the need for induction of labor in 45%. Preeclampsia occurred in 8%, 5% had spontaneous rupture of membranes, and 4% had gestational diabetes. There were no reported cases of endometritis or chorioamnionitis. There were no significant differences in preterm events between patients who were treated or deferred therapy.

There was one stillbirth, occurring in a 34-year-old woman with double-hit (two-mutation) NHL at 19 weeks after one cycle of R-CHOP.

One woman died before giving birth. She had very-high-risk DLBCL with significant metastases to the liver. She had been diagnosed at week 29 and died at week 32 from encephalopathy, but delivered a healthy infant before her death.

Outcomes for the fetuses of the 76 women who opted to continue their pregnancies included the aforementioned stillbirth and 1 case of microcephaly in a woman who had received four cycles of CHOP for DLBCL.

The median birth weight of neonates was 2,427 g (range 1,005-5,262 g), and there were no differences between the children of women who underwent antepartum chemotherapy or deferred therapy.

Dr. Evens noted that the investigators looked only at acute fetal outcomes, and have not evaluated long-term developmental measures.

The study was funded by the participating centers. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Women diagnosed with lymphoma during pregnancy stand a good chance of carrying a healthy child to term even when they opt for treatment during the second or third trimester, according to a retrospective multicenter analysis.

Among 82 women diagnosed with either Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma during pregnancy, 48 opted to start therapy during pregnancy rather than defer it until after delivery, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

All but one woman had a normal birth, the exception being a severe malformation: microcephaly in the fetus of a woman who had received four cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The timing of therapy did not appear to affect overall survival, with the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate being 76% among women who underwent treatment during pregnancy, compared with 79% for those who deferred it, said Dr. Andrew M. Evens of the University of Massachusetts in Worcester.

Respective overall survival rates were 92% and 83%, he reported. For the six women who elected to terminate their pregnancies, the 3-year PFS rate and overall survival rate were each 100%.

Among 39 women with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), the 3-year PFS rate was 90%, and overall survival was 95%. Among 33 patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), 73% were progression free at 3 years; the overall survival rate was 82%. For 10 women with NHL of T-cell histology, the respective figures were 50% and 90%.

"We conclude that standard chemotherapy – non-antimetabolite chemotherapy – and radiation in select cases, in particular localized disease likely above the diaphragm during the second and third trimester, were associated with expected maternal complications and fetal detriment," Dr. Evens said.

Women with low-risk disease, such as indolent NHL, or a diagnosis late in gestation may be able to defer therapy until after delivery, he added.

Cancers in Pregnancy Uncommon. Cancer diagnoses during pregnancy are uncommon, occurring in about 3,500 women annually in the United States. The estimated prevalence is 1 in 1,000 gestations. Hematologic malignancies, primarily lymphomas, account for about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Evens said.

He and his colleagues at nine academic medical centers conducted a descriptive retrospective analysis looking at histology, disease characteristics, therapy received, and maternal and fetal complications among pregnant women diagnosed with lymphomas from 1998 through 2011.

Of the 82 women identified for whom follow-up data were available, 43 (52%) were diagnosed with NHL (83% B-cell and 17% T-cell histologies) and 39 (48%) with HL. The median time of diagnosis was at 24 weeks gestation (range 5-40 weeks).

Six patients (4 with NHL and 2 with HL) decided to terminate the pregnancies to have immediate chemotherapy. Five of these patients were diagnosed in the first trimester and required systemic therapy.

The remaining patient was diagnosed early in the second trimester with lymphoma involving the central nervous system and requiring high-dose methotrexate, an antimetabolite in FDA pregnancy category X (positive evidence of fetal harm from animal or human studies and/or clinical experience; contraindicated). Other antimetabolites are classified in category D (positive evidence of fetal risk, but the benefits may warrant use in pregnant women).

A total of 28 patients (34%) chose to defer therapy, including 15 with HL, 5 with follicular lymphoma, 4 with DLBCL, 3 with T-cell lymphoma, and 1 with Burkitt’s lymphoma. The median gestation time at diagnosis in these patients was 34 weeks (range 6-38).

Of the 48 patients who chose to start therapy during pregnancy, 27 patients with NHL received therapy with CHOP, CHOP plus rituximab (Rituxan), modified hyperCVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone), or similar regimens.

All but 2 patients with HL received the ABVD regimen (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), and 4 of these patients also received partial-dose radiation therapy with shielding of the fetus. One patient received AVD (no bleomycin), and 1 received ChlVPP (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, and prednisone). Treatments ranged from the 13th to the 33rd week of gestation.

Among the 48 treated patients, gestation reached full term in 73% with delivery at a median of 37 weeks (range 31-40); most of the deliveries occurred at or after 35 weeks. Among the 28 patients who deferred therapy, delivery was at a median of 38 weeks (range 26-40), and 86% of these women were able to carry their pregnancies to term.

"The goal in every patient, whether they received therapy or not, was to try and deliver as close to term as possible," Dr. Evens said.

Among all patients, 72% had vaginal delivery, and 28% had cesarean sections.

Labor Induced in Nearly Half of Patients. The most common preterm complication was the need for induction of labor in 45%. Preeclampsia occurred in 8%, 5% had spontaneous rupture of membranes, and 4% had gestational diabetes. There were no reported cases of endometritis or chorioamnionitis. There were no significant differences in preterm events between patients who were treated or deferred therapy.

There was one stillbirth, occurring in a 34-year-old woman with double-hit (two-mutation) NHL at 19 weeks after one cycle of R-CHOP.

One woman died before giving birth. She had very-high-risk DLBCL with significant metastases to the liver. She had been diagnosed at week 29 and died at week 32 from encephalopathy, but delivered a healthy infant before her death.

Outcomes for the fetuses of the 76 women who opted to continue their pregnancies included the aforementioned stillbirth and 1 case of microcephaly in a woman who had received four cycles of CHOP for DLBCL.

The median birth weight of neonates was 2,427 g (range 1,005-5,262 g), and there were no differences between the children of women who underwent antepartum chemotherapy or deferred therapy.

Dr. Evens noted that the investigators looked only at acute fetal outcomes, and have not evaluated long-term developmental measures.

The study was funded by the participating centers. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF HEMATOLOGY

Major Finding: Among women with lymphomas diagnosed during pregnancy, the 3-year progression-free survival rates were 76% in women who underwent immediate treatment and 79% for those who deferred it until after delivery. Respective overall survival rates were 92% and 83%.

Data Source: Retrospective analysis of 82 cases from nine academic health centers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the participating centers. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Preterm Delivery a Risk in Systemic Sclerosis

Many women with systemic sclerosis can have successful pregnancies, but the rates of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction are approximately twice as high in these women compared to the general population of pregnant women, based on data from 109 pregnancies in 99 women with systemic sclerosis.

The findings were published in Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Dec. 28 [doi:10.1002/art.34350]).

Data from previous studies have suggested negative outcomes for pregnancies in women with systemic sclerosis (SSc), but these have been small case series or large database reviews that did not allow for the identification of individual patients, said Dr. Mara Taraborelli of Spedali Civili and University, Brescia, Italy, and colleagues.

In this prospective study, the researchers followed 99 women with SSc who had 109 pregnancies between 2000 and 2011. The women attended one of 25 participating research centers in Italy.

The average age at conception was 32 years, and most of the women were white. A total of 107 pregnancies were spontaneous, and 2 were achieved with assisted reproductive techniques.

Preterm deliveries were significantly more common in the SSc women, compared to the general obstetric population that served as a control group (25% vs. 12%, respectively). Severe preterm delivery (defined as delivery at less than 34 weeks) also was significantly more common in SSc women, compared to the controls (10% vs. 5%, respectively).

In addition, very low birth weight babies and cases of intrauterine growth restriction were significantly more common in the SSc women, compared to the controls (5% vs. 1%, respectively, and 6% vs. 1%, respectively).

The researchers found no increase in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or spontaneous pregnancy losses in SSc women, compared to the general pregnant population.

"We observed a low rate of disease progression shortly after the end of pregnancy; this risk might be greater in aSCL-70 positive patients with recent-onset disease," the researchers noted. All four cases of internal organ disease evolution within 12 months after delivery occurred in women who were aSCL-70 positive, and 3 of 23 (13%) of women who were aSCL-70 positive whose disease had lasted less than 3 years had some disease progression after delivery.

A total of six newborns spent a median of 15 days in the intensive care unit. Of these, one was severely premature and died of multi-organ failure.

The study findings were limited by the use of retrospective analysis and the use of controls for only one year, but the results suggest that successful pregnancies are possible for SSc women despite the increased risks for poor maternal and fetal outcomes, with multidisciplinary management, the researchers said. However, pregnancy may not be advisable for patients with severe organ damage or recent onset of SSc, especially those who are antitopoisomerase positive, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by three patients’ associations: the Gruppo Italiano Lotta alla Sclerodermia, Gruppo Lupus Eritematoso Sistemico Lombardia, and the Associazone Lombarda Malati Reumatici.

Findings from this study and other studies on pregnancy in women with systemic sclerosis are important because many affected patients are in their child-bearing years.

This is one of several studies on the topic of SSc and pregnancy, and findings from the other studies do not agree fully with these data. Findings from other studies have shown that the babies of women with SSc are more likely to have low weight for gestational age. Also, data from previous studies have shown that patients with severe SSc disease, just like all patients with any illness in the connective tissue disease realm, need to be very cautious when considering pregnancy. As always, good communication between the patient and physician and good clinical judgment are paramount.

When physicians counsel patients about pregnancy, the discussion should include specifics of cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal involvement as they relate to the patient’s condition. Other issues include family history, whether there are other children in the family, what kind of support systems the patient has, other medications needed to control disease, and the psychological status of the individual patient.

As for avenues for further research, larger prospective data sets are needed, including data on patients with concomitant illnesses, different medications, serologies, microchimerism, physiology, and genetics when possible. Of course, data are needed on both the short-term and long-term outcomes of the children as well as the mothers. In cases of poor outcomes, studies of tissue are warranted.

Dr. Daniel E. Furst is the Carl M. Pearson professor in rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles and a member of the Rheumatology News Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Furst has received research grants from multiple companies including Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, National Institutes of Health, and UCB. He has served as a consultant for multiple companies including Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Novartis, and Xoma. He has served on the speaker's bureau for Abbott and Genentech, and has received honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Encysive, and UCB.

Findings from this study and other studies on pregnancy in women with systemic sclerosis are important because many affected patients are in their child-bearing years.

This is one of several studies on the topic of SSc and pregnancy, and findings from the other studies do not agree fully with these data. Findings from other studies have shown that the babies of women with SSc are more likely to have low weight for gestational age. Also, data from previous studies have shown that patients with severe SSc disease, just like all patients with any illness in the connective tissue disease realm, need to be very cautious when considering pregnancy. As always, good communication between the patient and physician and good clinical judgment are paramount.

When physicians counsel patients about pregnancy, the discussion should include specifics of cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal involvement as they relate to the patient’s condition. Other issues include family history, whether there are other children in the family, what kind of support systems the patient has, other medications needed to control disease, and the psychological status of the individual patient.

As for avenues for further research, larger prospective data sets are needed, including data on patients with concomitant illnesses, different medications, serologies, microchimerism, physiology, and genetics when possible. Of course, data are needed on both the short-term and long-term outcomes of the children as well as the mothers. In cases of poor outcomes, studies of tissue are warranted.

Dr. Daniel E. Furst is the Carl M. Pearson professor in rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles and a member of the Rheumatology News Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Furst has received research grants from multiple companies including Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, National Institutes of Health, and UCB. He has served as a consultant for multiple companies including Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Novartis, and Xoma. He has served on the speaker's bureau for Abbott and Genentech, and has received honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Encysive, and UCB.

Findings from this study and other studies on pregnancy in women with systemic sclerosis are important because many affected patients are in their child-bearing years.

This is one of several studies on the topic of SSc and pregnancy, and findings from the other studies do not agree fully with these data. Findings from other studies have shown that the babies of women with SSc are more likely to have low weight for gestational age. Also, data from previous studies have shown that patients with severe SSc disease, just like all patients with any illness in the connective tissue disease realm, need to be very cautious when considering pregnancy. As always, good communication between the patient and physician and good clinical judgment are paramount.

When physicians counsel patients about pregnancy, the discussion should include specifics of cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal involvement as they relate to the patient’s condition. Other issues include family history, whether there are other children in the family, what kind of support systems the patient has, other medications needed to control disease, and the psychological status of the individual patient.

As for avenues for further research, larger prospective data sets are needed, including data on patients with concomitant illnesses, different medications, serologies, microchimerism, physiology, and genetics when possible. Of course, data are needed on both the short-term and long-term outcomes of the children as well as the mothers. In cases of poor outcomes, studies of tissue are warranted.

Dr. Daniel E. Furst is the Carl M. Pearson professor in rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles and a member of the Rheumatology News Editorial Advisory Board.

Dr. Furst has received research grants from multiple companies including Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, National Institutes of Health, and UCB. He has served as a consultant for multiple companies including Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Novartis, and Xoma. He has served on the speaker's bureau for Abbott and Genentech, and has received honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Encysive, and UCB.

Many women with systemic sclerosis can have successful pregnancies, but the rates of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction are approximately twice as high in these women compared to the general population of pregnant women, based on data from 109 pregnancies in 99 women with systemic sclerosis.

The findings were published in Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Dec. 28 [doi:10.1002/art.34350]).

Data from previous studies have suggested negative outcomes for pregnancies in women with systemic sclerosis (SSc), but these have been small case series or large database reviews that did not allow for the identification of individual patients, said Dr. Mara Taraborelli of Spedali Civili and University, Brescia, Italy, and colleagues.

In this prospective study, the researchers followed 99 women with SSc who had 109 pregnancies between 2000 and 2011. The women attended one of 25 participating research centers in Italy.

The average age at conception was 32 years, and most of the women were white. A total of 107 pregnancies were spontaneous, and 2 were achieved with assisted reproductive techniques.

Preterm deliveries were significantly more common in the SSc women, compared to the general obstetric population that served as a control group (25% vs. 12%, respectively). Severe preterm delivery (defined as delivery at less than 34 weeks) also was significantly more common in SSc women, compared to the controls (10% vs. 5%, respectively).

In addition, very low birth weight babies and cases of intrauterine growth restriction were significantly more common in the SSc women, compared to the controls (5% vs. 1%, respectively, and 6% vs. 1%, respectively).

The researchers found no increase in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or spontaneous pregnancy losses in SSc women, compared to the general pregnant population.

"We observed a low rate of disease progression shortly after the end of pregnancy; this risk might be greater in aSCL-70 positive patients with recent-onset disease," the researchers noted. All four cases of internal organ disease evolution within 12 months after delivery occurred in women who were aSCL-70 positive, and 3 of 23 (13%) of women who were aSCL-70 positive whose disease had lasted less than 3 years had some disease progression after delivery.

A total of six newborns spent a median of 15 days in the intensive care unit. Of these, one was severely premature and died of multi-organ failure.

The study findings were limited by the use of retrospective analysis and the use of controls for only one year, but the results suggest that successful pregnancies are possible for SSc women despite the increased risks for poor maternal and fetal outcomes, with multidisciplinary management, the researchers said. However, pregnancy may not be advisable for patients with severe organ damage or recent onset of SSc, especially those who are antitopoisomerase positive, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by three patients’ associations: the Gruppo Italiano Lotta alla Sclerodermia, Gruppo Lupus Eritematoso Sistemico Lombardia, and the Associazone Lombarda Malati Reumatici.

Many women with systemic sclerosis can have successful pregnancies, but the rates of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction are approximately twice as high in these women compared to the general population of pregnant women, based on data from 109 pregnancies in 99 women with systemic sclerosis.

The findings were published in Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Dec. 28 [doi:10.1002/art.34350]).

Data from previous studies have suggested negative outcomes for pregnancies in women with systemic sclerosis (SSc), but these have been small case series or large database reviews that did not allow for the identification of individual patients, said Dr. Mara Taraborelli of Spedali Civili and University, Brescia, Italy, and colleagues.

In this prospective study, the researchers followed 99 women with SSc who had 109 pregnancies between 2000 and 2011. The women attended one of 25 participating research centers in Italy.

The average age at conception was 32 years, and most of the women were white. A total of 107 pregnancies were spontaneous, and 2 were achieved with assisted reproductive techniques.

Preterm deliveries were significantly more common in the SSc women, compared to the general obstetric population that served as a control group (25% vs. 12%, respectively). Severe preterm delivery (defined as delivery at less than 34 weeks) also was significantly more common in SSc women, compared to the controls (10% vs. 5%, respectively).

In addition, very low birth weight babies and cases of intrauterine growth restriction were significantly more common in the SSc women, compared to the controls (5% vs. 1%, respectively, and 6% vs. 1%, respectively).

The researchers found no increase in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or spontaneous pregnancy losses in SSc women, compared to the general pregnant population.

"We observed a low rate of disease progression shortly after the end of pregnancy; this risk might be greater in aSCL-70 positive patients with recent-onset disease," the researchers noted. All four cases of internal organ disease evolution within 12 months after delivery occurred in women who were aSCL-70 positive, and 3 of 23 (13%) of women who were aSCL-70 positive whose disease had lasted less than 3 years had some disease progression after delivery.

A total of six newborns spent a median of 15 days in the intensive care unit. Of these, one was severely premature and died of multi-organ failure.

The study findings were limited by the use of retrospective analysis and the use of controls for only one year, but the results suggest that successful pregnancies are possible for SSc women despite the increased risks for poor maternal and fetal outcomes, with multidisciplinary management, the researchers said. However, pregnancy may not be advisable for patients with severe organ damage or recent onset of SSc, especially those who are antitopoisomerase positive, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by three patients’ associations: the Gruppo Italiano Lotta alla Sclerodermia, Gruppo Lupus Eritematoso Sistemico Lombardia, and the Associazone Lombarda Malati Reumatici.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Major Finding: Preterm deliveries were twice as common in pregnant women with systemic sclerosis, compared with pregnant women in the general population (25% vs. 12%, respectively).

Data Source: A prospective study of 99 women with systemic sclerosis.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by three patients’ associations: the Gruppo Italiano Lotta alla Sclerodermia, Gruppo Lupus Eritematoso Sistemico Lombardia, and the Associazone Lombarda Malati Reumatici.

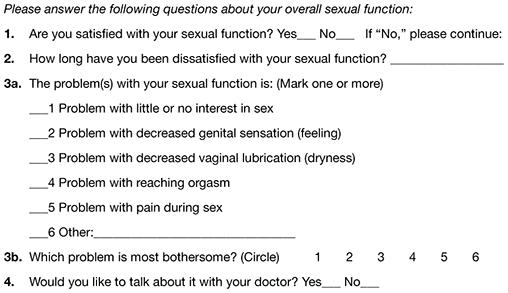

5 tips for talking to patients about postpartum sexuality

Related article How to prepare your patient for the many nuances of postpartum sexuality (January 2012)

Related article How to prepare your patient for the many nuances of postpartum sexuality (January 2012)

Related article How to prepare your patient for the many nuances of postpartum sexuality (January 2012)

Data on liability claims offer bright spots for ObGyns— and sobering statistics

Good news on the medical liability front, Doctor!

Yes, that’s right, good news.

According to data from the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA), the number of claims that were paid in the ObGyn category between 2006 and 2011 was 44% lower than the number of claims paid between 1986 and 1991.

The percentage of claims that were paid also decreased over the same quarter century. During 1986–1990, 37.25% of all claims were paid in the ObGyn category, compared with 31.73% during 2006–2010.1

And when claims for both periods are calculated in 2010 dollars, the amount paid also declined—by more than $138 million!

These are three of the findings that reflect “significant improvement” in obstetrics and gynecology in medical liability, says John B. Stanchfield, MD, an endocrinologist who, for 25 years, was medical director of the Utah Medical Insurance Association (UMIA)—a member company of PIAA. PIAA is the insurance industry trade association.

PIAA member companies in the United States “include large national insurance companies, mid-size regional writers, single-state insurers, and specialty companies that serve specific health care–provider niche markets. Collectively, these companies provide insurance protection to more than 60% of America’s private practice physicians and write approximately 46%, or $5.2 billion, of the total industry premium.”2

The improvement in ObGyn comes as no surprise to Dr. Stanchfield because the specialty was “the first group that got ‘risk-managed’ almost universally across the country,” he says. “In our little company out here in Utah, in 1985, we were told that if we didn’t do something [about lawsuits in obstetrics and gynecology], we weren’t going to be able to insure that class anymore because we wouldn’t be able to collect enough money. That’s what the actuaries told us, but it wasn’t unique to us—it was a nationwide problem.”

Why was the ObGyn specialty, in particular, in need of aggressive risk management? What made ObGyn claims unique?

“It’s infant injury,” says Dr. Stanchfield. “It’s injury to the baby. Those claims, you start talking at a million dollars.”

Another reason may be that some claims in this specialty category involve doctors other than ObGyns who provide obstetric care—for example, family practice physicians.

A risk manager’s perspective

After receiving the warning about ObGyn claims, UMIA got busy. First, it formed a committee comprising perinatologists, ObGyns, family practice physicians, claims specialists, and attorneys. “We analyzed all claims that were paid, looking for common denominators,” says Dr. Stanchfield. Improvement was clearly needed in about 10 areas, so “we basically created a risk-management program and then mandated it.” In the process, the organization published a booklet entitled Insurance Recommendations for Obstetrical Practice, of which Dr. Stanchfield was the editor.3

The booklet offers guidance on 10 potential “problem” areas:

- antepartum testing

- hypertension and pregnancy

- operative vaginal delivery

- breech delivery

- oxytocin administration

- vaginal birth after cesarean

- use of misoprostol

- shoulder dystocia

- preterm labor

- hospital standards.

Fewer claims and more physicians

The declining number and percentage of paid claims in obstetrics and gynecology over 25 years may be even more impressive than the figures suggest, says Dr. Stanchfield.

“Gestalt tells me that through the years there are more practicing physicians rather than fewer,” so the denominator is increasing even as these claims are declining—making the decrease “even more powerful.”

The numbers haven’t improved to the same degree in other specialties, Dr. Stanchfield says. “If you look at global data, the decrease in paid claims might have been 10% to 15%. In ObGyn, if you compare the last 5-year block of data with the first 5-year block, the number of paid claims is almost cut in half.”

What brought about this improvement?

“There weren’t any groundbreaking medical or surgical technological advances during this period. It was just doing it better. And the main push to doing it better in this country, in my opinion, is risk management.”

Slicing the data

Now for the not-so-great news: In 2010 alone, more than $55 million was paid out in the ObGyn category for 10 patient conditions. Topping the list were “pregnancy” and “brain-damaged infant.” The $55 million figure represents the money paid for the top 10 most commonly cited conditions in cases closed during 2010 (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1

Claims categorized under the rather broad category of pregnancy usually were placed there because a more appropriate category was lacking, says Dr. Stanchfield. These claims typically involve “things that happen—usually to the baby—that result in a lawsuit other than brain damage per se.” For example, a claim that involved skull fracture without brain damage might fall into this zone, he says.

Problematic procedures

Slicing the data a different way, problems related to the 10 most commonly cited ObGyn procedures cost PIAA companies more than $120 million dollars in 2010—and that figure is only for the top 10.1 The top three procedures, in terms of number of claims closed in 2010, were operative procedures on the uterus, manually assisted delivery, and cesarean delivery (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Manually assisted delivery does not include vacuum extraction or forceps delivery, notes Dr. Stanchfield. “Manually assisted delivery is basically standing there like a quarterback and catching the baby.”

Top 10 “medical misadventures”

And another slice of data reveals the 10 most prevalent medical misadventures in the ObGyn specialty in 2010 (TABLE 3):

- improper performance of a procedure

- no medical misadventure (i.e., no misadventure was identifiable)

- errors in diagnosis

- failure to supervise or monitor a case

- delay in performance of a procedure

- failure to recognize a complication

- surgical foreign body left in a patient after a procedure

- necessary treatment or management was “not performed”

- failure to instruct or communicate with a patient

- medication errors.

The total indemnity paid for these so-called misadventures was more than $136 million.1

TABLE 3

Putting the dollars in perspective

PIAA also collects data on the number of claims reported, and indemnity dollars paid, for other specialties.

“Of the 28 specialty groups included in the database, ObGyn ranks second”—behind internal medicine—“in the number of claims closed between 1985 and 2010,” a PIAA report notes. The ObGyn specialty also ranks second—behind dentists—in the percentage (35%) of those claims that were paid (for dentists, the figure was 46%). Obstetrics and gynecology was also responsible for the single largest indemnity payment—$13,000,000.1

Medical liability: A national disaster?

According to figures from the PIAA Data Sharing Project, an ongoing claim study that includes 22 PIAA member companies, $19.7 billion in losses (total indemnity plus expenses) were reported during the period from 1985 through 2008. Those losses represented approximately 25% of the physicians who were practicing during that time.

“So if you multiply that $19.7 billion figure by four”—to extrapolate it to the full spectrum of physicians practicing between 1985 and 2008—“you’ve got almost $80 billion coming out of the pockets of the doctors in this country,” says Dr. Stanchfield. If you compare that $80 billion figure to the World Trade Center disaster, which involved approximately $42 billion in losses, the need for federal tort reform is highlighted, he says. In 24 years, the physicians “in this country have paid for almost two World Trade Center disasters. That’s an incredible dollar cost.”

From Dr. Stanchfield’s perspective as a risk manager, the best thing physicians can do to protect themselves is to practice medicine wisely.

“One of our speakers used to say, ‘Look, just practice good, middle-of-the-road medicine. Don’t get yourself out on the fringes where you’re doing something questionable. Just practice rock-solid, conservative, safe medicine.’”

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Physician Insurers Association of America. 2011 Risk Management Review. Rockville, Md: PIAA; 2011.

2. Physician Insurers Association of America. PIAA Backgrounder. Rockville, Md: PIAA; 2011.

3. Stanchfied JB, ed. Insurance Recommendations for Obstetrical Practice. Revised ed. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Medical Insurance Association; 2009.

Good news on the medical liability front, Doctor!

Yes, that’s right, good news.

According to data from the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA), the number of claims that were paid in the ObGyn category between 2006 and 2011 was 44% lower than the number of claims paid between 1986 and 1991.

The percentage of claims that were paid also decreased over the same quarter century. During 1986–1990, 37.25% of all claims were paid in the ObGyn category, compared with 31.73% during 2006–2010.1

And when claims for both periods are calculated in 2010 dollars, the amount paid also declined—by more than $138 million!

These are three of the findings that reflect “significant improvement” in obstetrics and gynecology in medical liability, says John B. Stanchfield, MD, an endocrinologist who, for 25 years, was medical director of the Utah Medical Insurance Association (UMIA)—a member company of PIAA. PIAA is the insurance industry trade association.

PIAA member companies in the United States “include large national insurance companies, mid-size regional writers, single-state insurers, and specialty companies that serve specific health care–provider niche markets. Collectively, these companies provide insurance protection to more than 60% of America’s private practice physicians and write approximately 46%, or $5.2 billion, of the total industry premium.”2