User login

Evidence Suggests Pregnancies Can Survive Maternal Cancer Treatment

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

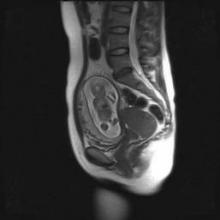

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."

The stress of a cancer diagnosis during a desired pregnancy is very hard on patients, Dr. Temkin added. "Pregnancy is a time when many women come to grips with their own mortality as well as that of giving new life. Adding a diagnosis of cancer of top of that – especially in the face of a much-desired pregnancy – can be devastating."

These women are faced with two options: terminate the pregnancy and concentrate on their own treatment, or continue the pregnancy knowing that their unborn child will be exposed to the possible risks of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Either option can "inflict terrible guilt on a pregnant woman. We can try to minimize that to some degree, but it’s important to know from the outset that what is the right solution for one patient is not right for the next."

Connecting with other women who have experienced the same situation can be of immense value, Dr. Cardonick said. She participates in an online support group called "Hope for Two."

The organization’s main goal is to link new patients with survivors who can help educate them as well as lend emotional support. Patients call in or fill out a secure online request for a personal match-up with a survivor, who is often a woman who has had the same type of cancer.

The website also contains links to news and medical articles, books, and financial assistance sources, and allows new patients to securely contact Dr. Cardonick’s pregnancy registry. "We keep in touch with the baby’s pediatrician and the mom every year, to see how things are going and [to] collect information," she said. "The best way to treat these women in the future depends on the information we continue to gather in the present."

None of the researchers interviewed for this article had any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Litton noted that she had no financial disclosures for her 2011 ASCO poster.

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."

The stress of a cancer diagnosis during a desired pregnancy is very hard on patients, Dr. Temkin added. "Pregnancy is a time when many women come to grips with their own mortality as well as that of giving new life. Adding a diagnosis of cancer of top of that – especially in the face of a much-desired pregnancy – can be devastating."

These women are faced with two options: terminate the pregnancy and concentrate on their own treatment, or continue the pregnancy knowing that their unborn child will be exposed to the possible risks of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Either option can "inflict terrible guilt on a pregnant woman. We can try to minimize that to some degree, but it’s important to know from the outset that what is the right solution for one patient is not right for the next."

Connecting with other women who have experienced the same situation can be of immense value, Dr. Cardonick said. She participates in an online support group called "Hope for Two."

The organization’s main goal is to link new patients with survivors who can help educate them as well as lend emotional support. Patients call in or fill out a secure online request for a personal match-up with a survivor, who is often a woman who has had the same type of cancer.

The website also contains links to news and medical articles, books, and financial assistance sources, and allows new patients to securely contact Dr. Cardonick’s pregnancy registry. "We keep in touch with the baby’s pediatrician and the mom every year, to see how things are going and [to] collect information," she said. "The best way to treat these women in the future depends on the information we continue to gather in the present."

None of the researchers interviewed for this article had any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Litton noted that she had no financial disclosures for her 2011 ASCO poster.

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."

The stress of a cancer diagnosis during a desired pregnancy is very hard on patients, Dr. Temkin added. "Pregnancy is a time when many women come to grips with their own mortality as well as that of giving new life. Adding a diagnosis of cancer of top of that – especially in the face of a much-desired pregnancy – can be devastating."

These women are faced with two options: terminate the pregnancy and concentrate on their own treatment, or continue the pregnancy knowing that their unborn child will be exposed to the possible risks of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Either option can "inflict terrible guilt on a pregnant woman. We can try to minimize that to some degree, but it’s important to know from the outset that what is the right solution for one patient is not right for the next."

Connecting with other women who have experienced the same situation can be of immense value, Dr. Cardonick said. She participates in an online support group called "Hope for Two."

The organization’s main goal is to link new patients with survivors who can help educate them as well as lend emotional support. Patients call in or fill out a secure online request for a personal match-up with a survivor, who is often a woman who has had the same type of cancer.

The website also contains links to news and medical articles, books, and financial assistance sources, and allows new patients to securely contact Dr. Cardonick’s pregnancy registry. "We keep in touch with the baby’s pediatrician and the mom every year, to see how things are going and [to] collect information," she said. "The best way to treat these women in the future depends on the information we continue to gather in the present."

None of the researchers interviewed for this article had any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Litton noted that she had no financial disclosures for her 2011 ASCO poster.

Stop performing median episiotomy!

Advocates of the liberal use of episiotomy have hypothesized that the procedure has many benefits, including:

Most studies do not provide strong support for these claims.

Utilization has declined. Over the past decades, the liberal use of episiotomy has given way to a pattern of practice that emphasizes restricted use.1-4 In the 1980s, in the United States, episiotomy incisions were performed in approximately 40% of vaginal deliveries5; in 2010, the rate at most obstetric facilities was <10%.

When the episiotomy rate was 40%, a median incision made sense: A very limited incision was sufficient to provide extra room for the passage of an average-sized fetus through an average-sized birth outlet. With the rate below 10% today, however, the likelihood is greater that episiotomy is being reserved for cases in which a significant clinical problem exists—most often, mismatch between the birth outlet and fetal size—and the appropriateness of median episiotomy comes into question. By restricting episiotomy incisions to the most complex clinical situations, the risk is greater that the episiotomy will be associated with a severe perineal laceration, such as a laceration of the anal sphincter (third-degree) or the rectal mucosa (fourth-degree)—or both.

A spotlight on severe lacerations. Over the past decade, practitioners of obstetrics have refocused attention on reducing the risk of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations—severe injuries that are associated with significant maternal morbidity. Clinical variables that increase the risk of a third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration include:

- nulliparity

- forceps delivery

- median episiotomy

- macrosomia

- persistent occiput posterior position.6

Many studies have reported that a median episiotomy is associated with a higher rate of third- and fourth-degree lacerations than either 1) deliveries without an episiotomy or 2) deliveries with a mediolateral episiotomy.1,7-9 With the modern practice of reserving episiotomy for the most complex vaginal deliveries and renewed attention to reducing the rate of third- and fourth-degree lacerations, the time has come for us to stop using the median episiotomy and switch to using a mediolateral episiotomy incision.

STOP: using the median episiotomy

Numerous studies have reported that the median episiotomy is associated with an increased risk of laceration of the anal sphincter (third-degree) and rectal mucosa (fourth-degree), compared with mediolateral episiotomy.

Randomized study of incisions. In a clinical trial, 407 nulliparous women were randomized to median or mediolateral episiotomy incision.10 The incisions were made at a time during the second stage of labor that was judged by the clinician to be most appropriate—typically immediately before delivery of the fetal head.

To perform mediolateral episiotomy, clinicians in this study used a pair of straight scissors to make an incision that began in the midline and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 to 4 cm, at an angle >45°. Median episiotomy was performed by incision of the perineal tissues for 2 to 3 cm, directly in the midline.

The clinical protocol resulted in more women assigned to mediolateral episiotomy (n=244) than to the midline episiotomy (n=159), but the two groups were well matched on such major clinical characteristics as age, gestational age at delivery, duration of the second stage, rate of operative delivery, and anesthesia used.

Compared to what was found with mediolateral episiotomy, the median episiotomy incision was associated with a statistically significant increase in the frequency of complete third-degree tears (median, 6.1%; mediolateral, 1.6%) and fourth-degree tears (median, 5.5%; mediolateral, 0.4%).

Further comparisons. Many clinicians avoid mediolateral episiotomy. Why? Because, compared with median episiotomy, a mediolateral incision is believed to be associated with greater postpartum pain, increased severity and incidence of dyspareunia, and more disfiguring scars.11

But subjects in the randomized trial that I just described, in which mediolateral and median episiotomy were compared,10 reported postpartum pain, postpartum use of pain medicine, and impaired bowel function at similar rates regardless of the type of incision.

Investigators determined that, in the first month after delivery, more women who had a median episiotomy resumed vaginal intercourse (18.1%, compared to 6.3% who had a mediolateral incision). In the second month after delivery, however, women in both the median and mediolateral episiotomy groups reported similar resumption of sexual intercourse (median, 82.8%; mediolateral, 80.8%).

Three months after delivery, physical examination determined that a higher percentage of subjects in the median incision group (43%) had what was judged to be a “good” appearance to the scar (compared to 27% in the mediolateral group). Last, subjects in the median group had a higher rate of perineal laxity (7%) than did women in the mediolateral group (1.6%).

START: using a mediolateral incision when episiotomy is necessary

Reducing the risk of severe perineal laceration is an important clinical goal because severe lacerations are associated with significant morbidity. In a study of 390 women who had a fourth-degree perineal laceration, 5% had significant complications that, in most cases, required additional surgery.12 Furthermore, in that study:

- 1.8% of women had a breakdown of the repair

- 2.8% had infection plus breakdown of the repair

- 0.8% had infection only.

In another study, 31% of women who sustained a fourth-degree laceration reported poor bowel control postpartum.7

Given the focus on reducing the rate of severe perineal laceration, I recommend that, in most cases, you reduce the use of median episiotomy and increase the use of mediolateral episiotomy.

Use a mediolateral incision for episiotomy

Make the incision at a 45°-angle; incisions made at >35° angle are associated with less of a risk of severe perineal laceration. Avoid using chromic sutures; rapid-absorption polyglactin 910 suture might offer better healing.

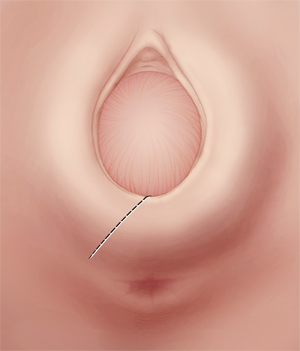

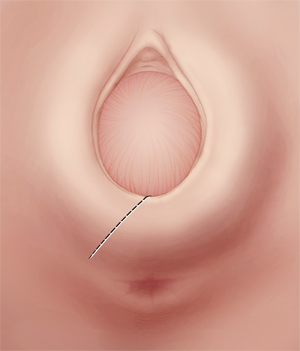

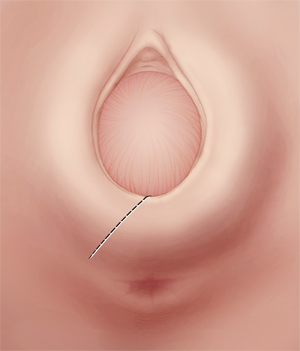

Mediolateral episiotomy: Technique

Begin the mediolateral episiotomy in the midline or slightly lateral to the midline (see the FIGURE). Insert two fingers into the vagina to distend the tissue of the birth outlet; using a pair of sharp, straight scissors, cut an incision 4 or 5 cm long at a 45° angle, directing it toward the ipsilateral ischial tuberosity. In most women, this incision cuts a portion of the bulbospongiosus muscle and, occasionally, reaches the ischioanal fossa.

Proper angle is key. The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy, in relation to the midline, is an important variable that influences the possibility that the patient will have a severe perineal laceration. Most experts recommend that the angle of the incision be at least 45° from the midline. If you use a shallow angle (<35°) from the midline to perform mediolateral episiotomy, you increase the risk of a severe perineal laceration, compared with incisions made at an angle >35° degrees from the midline (again, the FIGURE). In one report, the risk of a third-degree tear was about 10% with a 25°-angle mediolateral episiotomy, but less than 1% when the angle was >35°.13

Repairing the incision. After delivery, begin repair of a mediolateral incision by assessing the extent of vaginal, anal sphincter, rectal, and periurethral lacerations. Then, use two fingers, with or without a retractor, to spread the edges of the incision so that you can fully determine the length and depth of the episiotomy.

Place a 2-0 or 3-0 suture just above the apex of the incision. Use a running suture to close the vaginal mucosa and submucosal tissue. As you approach the introitus, suspend the running mucosal–submucosal suture and turn your attention to approximating the deeper submucosal space.

In mediolateral episiotomy, the upper-lateral edge of the incision contains more tissue than the lower-medial edge. To improve healing of the incision, use diagonal, rather than horizontal, sutures to provide better approximation of the submucosa. The fascia of the bulbocavernosus and superficial transveralis muscles might need to be reapproximated with individual sutures. Then, resume closing the skin and submucosa of the introitus and perineum.14 Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis might be warranted—before you repair a complex perineal laceration.15

Concern about suture material. Using chromic suture to repair an episiotomy incision is associated with increased postdelivery pain, compared with the use of rapid-absorption polyglactin 910 suture (Vicryl Rapide).16 In fact, most OBs have stopped using chromic suture to repair episiotomy incisions. Rapid-absorption polyglactin 910 suture (average time to absorption, 42 days) might be associated with less of a need to remove suture that migrates through the incision than what is seen with standard-absorption polyglactin 910 sutures (average time to absorption, 63 days).16,17

When an episiotomy is indicated

There is renewed emphasis on reducing the rate of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations at delivery, because these adverse outcomes are associated with:

- an increased risk of wound breakdown that requires surgical repair

- incontinence of flatus or stool, or both.

At a time when the use of episiotomy has become limited, continuing to use a median incision will get you more third- and fourth-degree lacerations than if you use a mediolateral episiotomy.

A mediolateral episiotomy might cause more perineal pain immediately postpartum but, within a few months after delivery, patients mostly have recovered from either type of episiotomy.

To recap: If an episiotomy is indicated, use a mediolateral incision. I urge you to stop performing median episiotomy incisions.

For many OBs, episiotomy is one of the most common operative procedures that they will perform during their career. Precisely because the procedure is common, and because it is considered minor surgery, coding for the creation of the incision and subsequent repair is, under Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) rules, considered integral to the services provided during delivery.

Repair of an intentional episiotomy closely compares to the repair required for a first- or second-degree laceration. For that reason, payers will not reimburse separately for this level of repair—even when made necessary by laceration of tissues and not by intentional episiotomy.

On the other hand, most payers do reimburse for repair of third- and fourth-degree lacerations and, at times, for a more complex repair of an extension to an intentional episiotomy.

Details explained

Coding options for more extensive intentional episiotomies and for third- and fourth-degree lacerations vary by payer. The simplest coding option is to add modifier -22 (increased procedural services) to the delivery or the global OB care code (for example, 59400-22 or 59409-22). To support use of this modifier, your documentation must include:

- the reason for the additional work (increased intensity, time, technical difficulty of procedure, severity of patient’s condition, physical and mental effort required)

- description of the significant additional work.

Some payers allow you to bill separately for the repair; do this by reporting the integumentary repair codes by type of repair:

- 12001-12007, for simple repair

- 12041-12047, for intermediate repair

- 13131-13132, for complex repair.

Select a code based on the total length of the repair, which must be documented as part of the description of the repair.

When repair is performed at the same time as the delivery, add modifier -51 to the separate repair code because this is considered a multiple procedure.

When repair is made after delivery with a return to the operating room, append a modifier -78 to the repair code.

Note that the CPT code 59300, Episiotomy or vaginal repair, by other than the attending physician, can never be reported by the attending OB or a physician who is covering for this physician; doing so will always result in a denial of the service.

MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Faced with a difficult vaginal delivery, would you use a median or mediolateral episiotomy incision? Why?

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists: Episiotomy. No. 71. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(4):957-962.

2. Myles TD, Santolaya J. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in patients with prolonged second stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):52-58.

3. Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Kimberger O, Wagenbichler P, Mayerhofer K. Management of the perineum during forceps delivery. Association of episiotomy with the frequency and severity of perineal trauma in women undergoing forceps delivery. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(4):239-242.

4. Hartmann K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, Gartlehner G, Thorpe J, Jr, Lohr KN. Outcomes of routine episiotomy a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2141-2148.

5. Barbieri RL. It’s time to restrict the use of episiotomy. OBG Manage. 2006;18(9):8-12.

6. De Leeuw JW, Struijik PC, Vierhout ME, Wallenburgh HC. Risk factors for third degree perineal ruptures during delivery. BJOG. 2001;108(4):383-387.

7. Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO. Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1543-1550.

8. Shiono P, Klebenoff MA, Carey JC. Midline episiotomies: more harm than good? Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(5):765-770.

9. Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Kaider A, et al. Risk factors for third-degree perineal tears in vaginal delivery, with an analysis of episiotomy types. J Reprod Med. 2001;46(8):752-756.

10. Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87(5):408-412.

11. Thacker SB, Banta HD. Benefits and risks of episiotomy: an interpretive review of the English language literature, 1860–1980. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1983;38(6):322-338.

12. Goldaber KG, Wendel PJ, McIntire DD, Wendel GD. Postpartum perineal morbidity after fourth degree perineal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(2):489-493.

13. Eogan M, Daly L, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Does the angle of episiotomy affect the incidence of anal sphincter injury? BJOG. 2006;113(2):190-194.

14. Hale RW, Ling FW. Episiotomy: Procedure and repair techniques. Washington DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2007:1-24.

15. Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, Bujor A, Caughey AB, El-Sayed YY. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1268-1273.

16. 1Greenberg JA, Lieberman E, Cohen AP, Ecker JL. Randomized comparison of chromic versus fast-absorbing polyglactin 910 for postpartum perineal repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(6):1308-1313.

17. Mackrodt C, Gordon B, Fern E, Ayers S, Truesdale A, Grant A. The Ipswich childbirth study 2. A randomised comparison of polyglactin 910 with chromic catgut for postpartum perineal repair. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;105(4):441-445.

Advocates of the liberal use of episiotomy have hypothesized that the procedure has many benefits, including:

Most studies do not provide strong support for these claims.

Utilization has declined. Over the past decades, the liberal use of episiotomy has given way to a pattern of practice that emphasizes restricted use.1-4 In the 1980s, in the United States, episiotomy incisions were performed in approximately 40% of vaginal deliveries5; in 2010, the rate at most obstetric facilities was <10%.

When the episiotomy rate was 40%, a median incision made sense: A very limited incision was sufficient to provide extra room for the passage of an average-sized fetus through an average-sized birth outlet. With the rate below 10% today, however, the likelihood is greater that episiotomy is being reserved for cases in which a significant clinical problem exists—most often, mismatch between the birth outlet and fetal size—and the appropriateness of median episiotomy comes into question. By restricting episiotomy incisions to the most complex clinical situations, the risk is greater that the episiotomy will be associated with a severe perineal laceration, such as a laceration of the anal sphincter (third-degree) or the rectal mucosa (fourth-degree)—or both.

A spotlight on severe lacerations. Over the past decade, practitioners of obstetrics have refocused attention on reducing the risk of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations—severe injuries that are associated with significant maternal morbidity. Clinical variables that increase the risk of a third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration include:

- nulliparity

- forceps delivery

- median episiotomy

- macrosomia

- persistent occiput posterior position.6

Many studies have reported that a median episiotomy is associated with a higher rate of third- and fourth-degree lacerations than either 1) deliveries without an episiotomy or 2) deliveries with a mediolateral episiotomy.1,7-9 With the modern practice of reserving episiotomy for the most complex vaginal deliveries and renewed attention to reducing the rate of third- and fourth-degree lacerations, the time has come for us to stop using the median episiotomy and switch to using a mediolateral episiotomy incision.

STOP: using the median episiotomy

Numerous studies have reported that the median episiotomy is associated with an increased risk of laceration of the anal sphincter (third-degree) and rectal mucosa (fourth-degree), compared with mediolateral episiotomy.

Randomized study of incisions. In a clinical trial, 407 nulliparous women were randomized to median or mediolateral episiotomy incision.10 The incisions were made at a time during the second stage of labor that was judged by the clinician to be most appropriate—typically immediately before delivery of the fetal head.

To perform mediolateral episiotomy, clinicians in this study used a pair of straight scissors to make an incision that began in the midline and was carried to the right side of the anal sphincter for 3 to 4 cm, at an angle >45°. Median episiotomy was performed by incision of the perineal tissues for 2 to 3 cm, directly in the midline.

The clinical protocol resulted in more women assigned to mediolateral episiotomy (n=244) than to the midline episiotomy (n=159), but the two groups were well matched on such major clinical characteristics as age, gestational age at delivery, duration of the second stage, rate of operative delivery, and anesthesia used.

Compared to what was found with mediolateral episiotomy, the median episiotomy incision was associated with a statistically significant increase in the frequency of complete third-degree tears (median, 6.1%; mediolateral, 1.6%) and fourth-degree tears (median, 5.5%; mediolateral, 0.4%).

Further comparisons. Many clinicians avoid mediolateral episiotomy. Why? Because, compared with median episiotomy, a mediolateral incision is believed to be associated with greater postpartum pain, increased severity and incidence of dyspareunia, and more disfiguring scars.11

But subjects in the randomized trial that I just described, in which mediolateral and median episiotomy were compared,10 reported postpartum pain, postpartum use of pain medicine, and impaired bowel function at similar rates regardless of the type of incision.

Investigators determined that, in the first month after delivery, more women who had a median episiotomy resumed vaginal intercourse (18.1%, compared to 6.3% who had a mediolateral incision). In the second month after delivery, however, women in both the median and mediolateral episiotomy groups reported similar resumption of sexual intercourse (median, 82.8%; mediolateral, 80.8%).

Three months after delivery, physical examination determined that a higher percentage of subjects in the median incision group (43%) had what was judged to be a “good” appearance to the scar (compared to 27% in the mediolateral group). Last, subjects in the median group had a higher rate of perineal laxity (7%) than did women in the mediolateral group (1.6%).

START: using a mediolateral incision when episiotomy is necessary

Reducing the risk of severe perineal laceration is an important clinical goal because severe lacerations are associated with significant morbidity. In a study of 390 women who had a fourth-degree perineal laceration, 5% had significant complications that, in most cases, required additional surgery.12 Furthermore, in that study:

- 1.8% of women had a breakdown of the repair

- 2.8% had infection plus breakdown of the repair

- 0.8% had infection only.

In another study, 31% of women who sustained a fourth-degree laceration reported poor bowel control postpartum.7

Given the focus on reducing the rate of severe perineal laceration, I recommend that, in most cases, you reduce the use of median episiotomy and increase the use of mediolateral episiotomy.

Use a mediolateral incision for episiotomy

Make the incision at a 45°-angle; incisions made at >35° angle are associated with less of a risk of severe perineal laceration. Avoid using chromic sutures; rapid-absorption polyglactin 910 suture might offer better healing.

Mediolateral episiotomy: Technique

Begin the mediolateral episiotomy in the midline or slightly lateral to the midline (see the FIGURE). Insert two fingers into the vagina to distend the tissue of the birth outlet; using a pair of sharp, straight scissors, cut an incision 4 or 5 cm long at a 45° angle, directing it toward the ipsilateral ischial tuberosity. In most women, this incision cuts a portion of the bulbospongiosus muscle and, occasionally, reaches the ischioanal fossa.

Proper angle is key. The angle of the mediolateral episiotomy, in relation to the midline, is an important variable that influences the possibility that the patient will have a severe perineal laceration. Most experts recommend that the angle of the incision be at least 45° from the midline. If you use a shallow angle (<35°) from the midline to perform mediolateral episiotomy, you increase the risk of a severe perineal laceration, compared with incisions made at an angle >35° degrees from the midline (again, the FIGURE). In one report, the risk of a third-degree tear was about 10% with a 25°-angle mediolateral episiotomy, but less than 1% when the angle was >35°.13