User login

High-dose folic acid during pregnancy tied to cancer risk in children

new data from a Scandinavian registry of more than 3 million pregnancies suggests.

The increased risk for cancer did not change after considering other factors that could explain the risk, such as use of antiseizure medication (ASM).

There was no increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy who used high-dose folic acid.

The results of this study “should be considered when the risks and benefits of folic acid supplements for women with epilepsy are discussed and before decisions about optimal dose recommendations are made,” the authors write.

“Although we believe that the association between prescription fills for high-dose folic acid and cancer in children born to mothers with epilepsy is robust, it is important to underline that these are the findings of one study only,” first author Håkon Magne Vegrim, MD, with University of Bergen (Norway) told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Risks and benefits

Women with epilepsy are advised to take high doses of folic acid before and during pregnancy owing to the risk for congenital malformations associated with ASM. Whether high-dose folic acid is associated with increases in the risk for childhood cancer is unknown.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed registry data from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for 3.3 million children followed to a median age of 7.3 years.

Among the 27,784 children born to mothers with epilepsy, 5,934 (21.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 4.3 mg), with a cancer incidence rate of 42.5 per 100,000 person-years in 18 exposed cancer cases compared with 18.4 per 100,000 person-years in 29 unexposed cancer cases – yielding an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.3).

The absolute risk with exposure was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%) in children of mothers with epilepsy compared with 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%) in children of mothers with epilepsy who were not exposed high-dose folic acid.

Prenatal exposure to high-dose folic acid was not associated with an increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy.

In children of mothers without epilepsy, 46,646 (1.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 2.9 mg). There were 69 exposed and 4,927 unexposed cancer cases and an aHR for cancer of 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9-1.4) and absolute risk for cancer of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.3%-0.5%).

There was no association between any specific ASM and childhood cancer.

“Removing mothers with any prescription fills for carbamazepine and valproate was not associated with the point estimate. Hence, these two ASMs were not important effect modifiers for the cancer association,” the investigators note in their study.

They also note that the most common childhood cancer types in children among mothers with epilepsy who took high-dose folic acid did not differ from the distribution in the general population.

“We need to get more knowledge about the potential mechanisms behind high-dose folic acid and childhood cancer, and it is important to identify the optimal dose to balance risks and benefits – and whether folic acid supplementation should be more individualized, based on factors like the serum level of folate and what type of antiseizure medication that is being used,” said Dr. Vegrim.

Practice changing?

Weighing in on the study, Elizabeth E. Gerard, MD, director of the Women with Epilepsy Program and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University in Chicago, said, “There are known benefits of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy including a decreased risk of neural tube defects in the general population and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born to mothers with and without epilepsy.”

“However, despite some expert guidelines recommending high-dose folic acid supplementation, there is a lack of certainty surrounding the ‘just right’ dose for patients with epilepsy who may become pregnant,” said Dr. Gerard, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Gerard, a member of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that other epidemiologic studies of folic acid supplementation and cancer have had “contradictory results, thus further research on this association will be needed. Additionally, differences in maternal/fetal folate metabolism and blood levels may be an important factor to study in the future.

“That said, this study definitely should cause us to pause and reevaluate the common practice of high-dose folic acid supplementation for patients with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy,” said Dr. Gerard.

The study was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Program on Health and Welfare. Dr. Vegrim and Dr. Gerard report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new data from a Scandinavian registry of more than 3 million pregnancies suggests.

The increased risk for cancer did not change after considering other factors that could explain the risk, such as use of antiseizure medication (ASM).

There was no increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy who used high-dose folic acid.

The results of this study “should be considered when the risks and benefits of folic acid supplements for women with epilepsy are discussed and before decisions about optimal dose recommendations are made,” the authors write.

“Although we believe that the association between prescription fills for high-dose folic acid and cancer in children born to mothers with epilepsy is robust, it is important to underline that these are the findings of one study only,” first author Håkon Magne Vegrim, MD, with University of Bergen (Norway) told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Risks and benefits

Women with epilepsy are advised to take high doses of folic acid before and during pregnancy owing to the risk for congenital malformations associated with ASM. Whether high-dose folic acid is associated with increases in the risk for childhood cancer is unknown.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed registry data from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for 3.3 million children followed to a median age of 7.3 years.

Among the 27,784 children born to mothers with epilepsy, 5,934 (21.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 4.3 mg), with a cancer incidence rate of 42.5 per 100,000 person-years in 18 exposed cancer cases compared with 18.4 per 100,000 person-years in 29 unexposed cancer cases – yielding an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.3).

The absolute risk with exposure was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%) in children of mothers with epilepsy compared with 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%) in children of mothers with epilepsy who were not exposed high-dose folic acid.

Prenatal exposure to high-dose folic acid was not associated with an increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy.

In children of mothers without epilepsy, 46,646 (1.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 2.9 mg). There were 69 exposed and 4,927 unexposed cancer cases and an aHR for cancer of 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9-1.4) and absolute risk for cancer of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.3%-0.5%).

There was no association between any specific ASM and childhood cancer.

“Removing mothers with any prescription fills for carbamazepine and valproate was not associated with the point estimate. Hence, these two ASMs were not important effect modifiers for the cancer association,” the investigators note in their study.

They also note that the most common childhood cancer types in children among mothers with epilepsy who took high-dose folic acid did not differ from the distribution in the general population.

“We need to get more knowledge about the potential mechanisms behind high-dose folic acid and childhood cancer, and it is important to identify the optimal dose to balance risks and benefits – and whether folic acid supplementation should be more individualized, based on factors like the serum level of folate and what type of antiseizure medication that is being used,” said Dr. Vegrim.

Practice changing?

Weighing in on the study, Elizabeth E. Gerard, MD, director of the Women with Epilepsy Program and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University in Chicago, said, “There are known benefits of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy including a decreased risk of neural tube defects in the general population and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born to mothers with and without epilepsy.”

“However, despite some expert guidelines recommending high-dose folic acid supplementation, there is a lack of certainty surrounding the ‘just right’ dose for patients with epilepsy who may become pregnant,” said Dr. Gerard, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Gerard, a member of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that other epidemiologic studies of folic acid supplementation and cancer have had “contradictory results, thus further research on this association will be needed. Additionally, differences in maternal/fetal folate metabolism and blood levels may be an important factor to study in the future.

“That said, this study definitely should cause us to pause and reevaluate the common practice of high-dose folic acid supplementation for patients with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy,” said Dr. Gerard.

The study was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Program on Health and Welfare. Dr. Vegrim and Dr. Gerard report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new data from a Scandinavian registry of more than 3 million pregnancies suggests.

The increased risk for cancer did not change after considering other factors that could explain the risk, such as use of antiseizure medication (ASM).

There was no increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy who used high-dose folic acid.

The results of this study “should be considered when the risks and benefits of folic acid supplements for women with epilepsy are discussed and before decisions about optimal dose recommendations are made,” the authors write.

“Although we believe that the association between prescription fills for high-dose folic acid and cancer in children born to mothers with epilepsy is robust, it is important to underline that these are the findings of one study only,” first author Håkon Magne Vegrim, MD, with University of Bergen (Norway) told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Risks and benefits

Women with epilepsy are advised to take high doses of folic acid before and during pregnancy owing to the risk for congenital malformations associated with ASM. Whether high-dose folic acid is associated with increases in the risk for childhood cancer is unknown.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed registry data from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for 3.3 million children followed to a median age of 7.3 years.

Among the 27,784 children born to mothers with epilepsy, 5,934 (21.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 4.3 mg), with a cancer incidence rate of 42.5 per 100,000 person-years in 18 exposed cancer cases compared with 18.4 per 100,000 person-years in 29 unexposed cancer cases – yielding an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.3).

The absolute risk with exposure was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%) in children of mothers with epilepsy compared with 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3%-1.1%) in children of mothers with epilepsy who were not exposed high-dose folic acid.

Prenatal exposure to high-dose folic acid was not associated with an increased risk for cancer in children of mothers without epilepsy.

In children of mothers without epilepsy, 46,646 (1.4%) were exposed to high-dose folic acid (mean dose, 2.9 mg). There were 69 exposed and 4,927 unexposed cancer cases and an aHR for cancer of 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9-1.4) and absolute risk for cancer of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.3%-0.5%).

There was no association between any specific ASM and childhood cancer.

“Removing mothers with any prescription fills for carbamazepine and valproate was not associated with the point estimate. Hence, these two ASMs were not important effect modifiers for the cancer association,” the investigators note in their study.

They also note that the most common childhood cancer types in children among mothers with epilepsy who took high-dose folic acid did not differ from the distribution in the general population.

“We need to get more knowledge about the potential mechanisms behind high-dose folic acid and childhood cancer, and it is important to identify the optimal dose to balance risks and benefits – and whether folic acid supplementation should be more individualized, based on factors like the serum level of folate and what type of antiseizure medication that is being used,” said Dr. Vegrim.

Practice changing?

Weighing in on the study, Elizabeth E. Gerard, MD, director of the Women with Epilepsy Program and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University in Chicago, said, “There are known benefits of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy including a decreased risk of neural tube defects in the general population and improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born to mothers with and without epilepsy.”

“However, despite some expert guidelines recommending high-dose folic acid supplementation, there is a lack of certainty surrounding the ‘just right’ dose for patients with epilepsy who may become pregnant,” said Dr. Gerard, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Dr. Gerard, a member of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that other epidemiologic studies of folic acid supplementation and cancer have had “contradictory results, thus further research on this association will be needed. Additionally, differences in maternal/fetal folate metabolism and blood levels may be an important factor to study in the future.

“That said, this study definitely should cause us to pause and reevaluate the common practice of high-dose folic acid supplementation for patients with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy,” said Dr. Gerard.

The study was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Program on Health and Welfare. Dr. Vegrim and Dr. Gerard report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

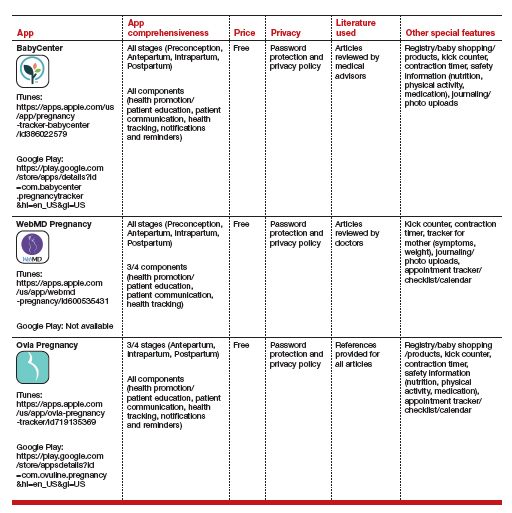

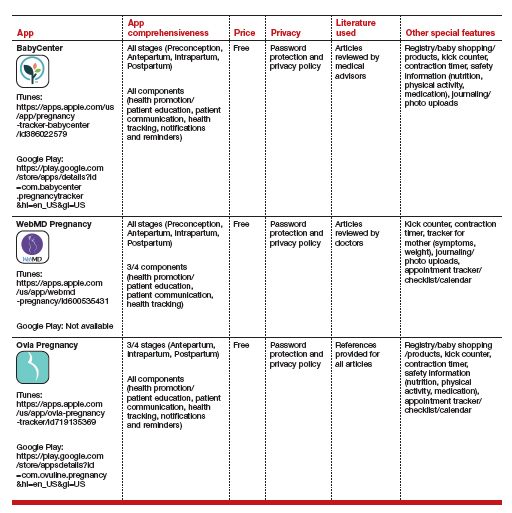

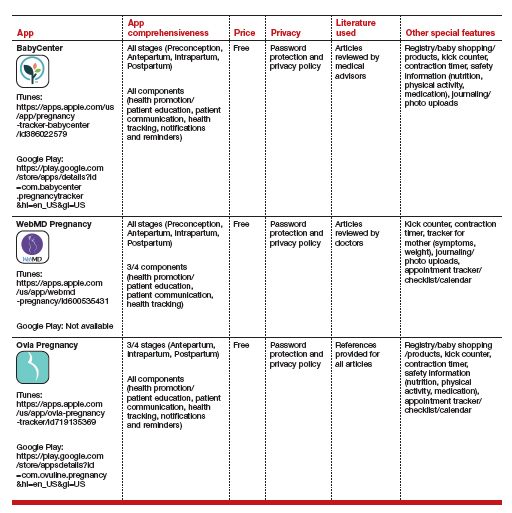

Top pregnancy apps for your patients

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

Hypertensive disorder during pregnancy increases risk for elevated blood pressure in offspring

Key clinical point: Offspring who were exposed in utero to any subtype of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (HDP) were at an increased risk for higher blood pressure (BP) than those with no exposure.

Major finding: In utero exposure vs no exposure to HDP was associated with higher systolic BP (mean difference 2.46 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.88-3.03 mm Hg) in offspring. Higher systolic BP was also observed in offspring exposed vs not exposed in utero to HDP subtypes, including pregnancy-associated hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and chronic hypertension.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 cohort studies including 3839 offspring who were exposed to HDP in utero and 57,977 offspring from normotensive mothers.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program, China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu H et al. Association between hypertensive disorders during pregnancy and elevated blood pressure in offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2022 (Sep 12). Doi: 10.1111/jch.14577

Key clinical point: Offspring who were exposed in utero to any subtype of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (HDP) were at an increased risk for higher blood pressure (BP) than those with no exposure.

Major finding: In utero exposure vs no exposure to HDP was associated with higher systolic BP (mean difference 2.46 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.88-3.03 mm Hg) in offspring. Higher systolic BP was also observed in offspring exposed vs not exposed in utero to HDP subtypes, including pregnancy-associated hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and chronic hypertension.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 cohort studies including 3839 offspring who were exposed to HDP in utero and 57,977 offspring from normotensive mothers.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program, China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu H et al. Association between hypertensive disorders during pregnancy and elevated blood pressure in offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2022 (Sep 12). Doi: 10.1111/jch.14577

Key clinical point: Offspring who were exposed in utero to any subtype of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (HDP) were at an increased risk for higher blood pressure (BP) than those with no exposure.

Major finding: In utero exposure vs no exposure to HDP was associated with higher systolic BP (mean difference 2.46 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.88-3.03 mm Hg) in offspring. Higher systolic BP was also observed in offspring exposed vs not exposed in utero to HDP subtypes, including pregnancy-associated hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and chronic hypertension.

Study details: Findings are from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 cohort studies including 3839 offspring who were exposed to HDP in utero and 57,977 offspring from normotensive mothers.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program, China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu H et al. Association between hypertensive disorders during pregnancy and elevated blood pressure in offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2022 (Sep 12). Doi: 10.1111/jch.14577

Obstetrics injuries and management during shoulder dystocia

Key clinical point: The risk for brachial plexus strain, injury, or tear can be minimized with prompt identification of shoulder dystocia (SD) accompanied by cessation of axial fetal head traction, while accurate obstetrical maneuvers can avoid permanent obstetric brachial palsy (OBP) or cerebral morbidity.

Major finding: SD was mostly unilateral anterior, with only 0.9% of cases diagnosed as the more difficult bilateral SD and 2% as recurrent SD. The majority (87.4%) of SD cases were managed by McRobert’s maneuver; the other management procedures included Barnum’s procedure (7.9%), Wood’s maneuver (3.9%), and Menticoglou procedure (0.4%). Only 7.5% of newborns were diagnosed with transient form of Duchenne Erb obstetrics brachioparesis (OBP), none with permanent OBP, and only 1 with cerebral morbidity.

Study details: This retrospective study analyzed the data of 45,687 singleton deliveries (vaginal deliveries, 78.9%; cesarean sections, 21.1%). Overall, 0.7% of vaginally delivered neonates had fetal SD.

Disclosures: No source of funding was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Habek D et al. Obstetrics injuries during shoulder dystocia in a tertiary perinatal center. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;278:33-37 (Sep 10). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.09.009

Key clinical point: The risk for brachial plexus strain, injury, or tear can be minimized with prompt identification of shoulder dystocia (SD) accompanied by cessation of axial fetal head traction, while accurate obstetrical maneuvers can avoid permanent obstetric brachial palsy (OBP) or cerebral morbidity.

Major finding: SD was mostly unilateral anterior, with only 0.9% of cases diagnosed as the more difficult bilateral SD and 2% as recurrent SD. The majority (87.4%) of SD cases were managed by McRobert’s maneuver; the other management procedures included Barnum’s procedure (7.9%), Wood’s maneuver (3.9%), and Menticoglou procedure (0.4%). Only 7.5% of newborns were diagnosed with transient form of Duchenne Erb obstetrics brachioparesis (OBP), none with permanent OBP, and only 1 with cerebral morbidity.

Study details: This retrospective study analyzed the data of 45,687 singleton deliveries (vaginal deliveries, 78.9%; cesarean sections, 21.1%). Overall, 0.7% of vaginally delivered neonates had fetal SD.

Disclosures: No source of funding was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Habek D et al. Obstetrics injuries during shoulder dystocia in a tertiary perinatal center. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;278:33-37 (Sep 10). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.09.009

Key clinical point: The risk for brachial plexus strain, injury, or tear can be minimized with prompt identification of shoulder dystocia (SD) accompanied by cessation of axial fetal head traction, while accurate obstetrical maneuvers can avoid permanent obstetric brachial palsy (OBP) or cerebral morbidity.

Major finding: SD was mostly unilateral anterior, with only 0.9% of cases diagnosed as the more difficult bilateral SD and 2% as recurrent SD. The majority (87.4%) of SD cases were managed by McRobert’s maneuver; the other management procedures included Barnum’s procedure (7.9%), Wood’s maneuver (3.9%), and Menticoglou procedure (0.4%). Only 7.5% of newborns were diagnosed with transient form of Duchenne Erb obstetrics brachioparesis (OBP), none with permanent OBP, and only 1 with cerebral morbidity.

Study details: This retrospective study analyzed the data of 45,687 singleton deliveries (vaginal deliveries, 78.9%; cesarean sections, 21.1%). Overall, 0.7% of vaginally delivered neonates had fetal SD.

Disclosures: No source of funding was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Habek D et al. Obstetrics injuries during shoulder dystocia in a tertiary perinatal center. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;278:33-37 (Sep 10). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.09.009

Preventive B-Lynch suture effective in women at high postpartum hemorrhage risk

Key clinical point: Preventive B-Lynch suture seemed safe and effective in preventing excessive maternal hemorrhage in patients at a high risk for postpartum hemorrhage.

Major finding: Overall, 92% of patients who underwent the B-Lynch suture procedure showed no apparent postoperative bleeding within 2 hours after the cesarean section (CS), with 24 patients requiring intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion, none requiring hysterectomy, and only 1 patient with a twin pregnancy requiring additional treatment because of secondary postpartum hemorrhage 5 days after the CS. Adverse events seemed unrelated to the procedure.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study including 663 patients who underwent CS, of which 38 patients underwent the preventive B-Lynch suture procedure before excessive blood loss occurred during CS.

Disclosures: No source of funding was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kuwabara M et al. Effectiveness of preventive B-Lynch sutures in patients at a high risk of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022 (Sep 11). Doi: 10.1111/jog.15415

Key clinical point: Preventive B-Lynch suture seemed safe and effective in preventing excessive maternal hemorrhage in patients at a high risk for postpartum hemorrhage.

Major finding: Overall, 92% of patients who underwent the B-Lynch suture procedure showed no apparent postoperative bleeding within 2 hours after the cesarean section (CS), with 24 patients requiring intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion, none requiring hysterectomy, and only 1 patient with a twin pregnancy requiring additional treatment because of secondary postpartum hemorrhage 5 days after the CS. Adverse events seemed unrelated to the procedure.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study including 663 patients who underwent CS, of which 38 patients underwent the preventive B-Lynch suture procedure before excessive blood loss occurred during CS.

Disclosures: No source of funding was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kuwabara M et al. Effectiveness of preventive B-Lynch sutures in patients at a high risk of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022 (Sep 11). Doi: 10.1111/jog.15415

Key clinical point: Preventive B-Lynch suture seemed safe and effective in preventing excessive maternal hemorrhage in patients at a high risk for postpartum hemorrhage.

Major finding: Overall, 92% of patients who underwent the B-Lynch suture procedure showed no apparent postoperative bleeding within 2 hours after the cesarean section (CS), with 24 patients requiring intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion, none requiring hysterectomy, and only 1 patient with a twin pregnancy requiring additional treatment because of secondary postpartum hemorrhage 5 days after the CS. Adverse events seemed unrelated to the procedure.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study including 663 patients who underwent CS, of which 38 patients underwent the preventive B-Lynch suture procedure before excessive blood loss occurred during CS.

Disclosures: No source of funding was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kuwabara M et al. Effectiveness of preventive B-Lynch sutures in patients at a high risk of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022 (Sep 11). Doi: 10.1111/jog.15415

Risk for severe birth injury higher with breech vs cephalic vaginal delivery

Key clinical point: Birth injuries are rare with breech vaginal delivery (VD); however, severe birth injury incidence is nearly 2-times higher with breech VD compared with cephalic VD, with brachial plexus palsy (BPP) being more common with breech vs cephalic VD.

Major finding: The incidence of severe birth injury with breech VD, cephalic VD, and cesarean section with breech presentation were 0.76/100, 0.31/100, and 0.059/100 live births, respectively. BPP occurred more frequently with breech VD (0.6% of live births) than with cephalic VD (0.3% of live births).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study including 650,528 neonates who were delivered by breech VD (0.7%), breech cesarean section (2.6%), or cephalic VD (96.7%).

Disclosures: This study was partly funded by competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Tampere University Hospital, Finland. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kekki M et al. Birth injury in breech delivery: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Finland. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022 (Sep 8). Doi: 10.1007/s00404-022-06772-1

Key clinical point: Birth injuries are rare with breech vaginal delivery (VD); however, severe birth injury incidence is nearly 2-times higher with breech VD compared with cephalic VD, with brachial plexus palsy (BPP) being more common with breech vs cephalic VD.

Major finding: The incidence of severe birth injury with breech VD, cephalic VD, and cesarean section with breech presentation were 0.76/100, 0.31/100, and 0.059/100 live births, respectively. BPP occurred more frequently with breech VD (0.6% of live births) than with cephalic VD (0.3% of live births).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study including 650,528 neonates who were delivered by breech VD (0.7%), breech cesarean section (2.6%), or cephalic VD (96.7%).

Disclosures: This study was partly funded by competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Tampere University Hospital, Finland. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kekki M et al. Birth injury in breech delivery: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Finland. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022 (Sep 8). Doi: 10.1007/s00404-022-06772-1

Key clinical point: Birth injuries are rare with breech vaginal delivery (VD); however, severe birth injury incidence is nearly 2-times higher with breech VD compared with cephalic VD, with brachial plexus palsy (BPP) being more common with breech vs cephalic VD.

Major finding: The incidence of severe birth injury with breech VD, cephalic VD, and cesarean section with breech presentation were 0.76/100, 0.31/100, and 0.059/100 live births, respectively. BPP occurred more frequently with breech VD (0.6% of live births) than with cephalic VD (0.3% of live births).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study including 650,528 neonates who were delivered by breech VD (0.7%), breech cesarean section (2.6%), or cephalic VD (96.7%).

Disclosures: This study was partly funded by competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Tampere University Hospital, Finland. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kekki M et al. Birth injury in breech delivery: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Finland. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022 (Sep 8). Doi: 10.1007/s00404-022-06772-1

Preterm preeclampsia associated with persistent cardiovascular morbidity

Key clinical point: A majority of women with preterm preeclampsia showed persistent cardiovascular morbidity at 6 months postpartum, which may have significant implications to long-term cardiovascular health.

Major finding: At 6 months postpartum, diastolic dysfunction, increased total vascular resistance (TVR), and persistent left ventricular remodeling were observed in 61%, 75%, and 41% of women, respectively, with 46% of women with no pre-existing hypertension having de novo hypertension and only 5% of women having a completely normal echocardiogram. A significant association was observed between prolonged preeclampsia duration and increased TVR at 6 months (P = .02).

Study details: Findings are from a sub-study of PICk-UP trial involving 44 postnatal women with preterm preeclampsia who delivered before 37 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Medical Research Council, UK. The authors declared no competing financial interests.

Source: Ormesher L et al. Postnatal cardiovascular morbidity following preterm pre-eclampsia: An observational study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;30:68-81 (Aug 17). Doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2022.08.007

Key clinical point: A majority of women with preterm preeclampsia showed persistent cardiovascular morbidity at 6 months postpartum, which may have significant implications to long-term cardiovascular health.

Major finding: At 6 months postpartum, diastolic dysfunction, increased total vascular resistance (TVR), and persistent left ventricular remodeling were observed in 61%, 75%, and 41% of women, respectively, with 46% of women with no pre-existing hypertension having de novo hypertension and only 5% of women having a completely normal echocardiogram. A significant association was observed between prolonged preeclampsia duration and increased TVR at 6 months (P = .02).

Study details: Findings are from a sub-study of PICk-UP trial involving 44 postnatal women with preterm preeclampsia who delivered before 37 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Medical Research Council, UK. The authors declared no competing financial interests.

Source: Ormesher L et al. Postnatal cardiovascular morbidity following preterm pre-eclampsia: An observational study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;30:68-81 (Aug 17). Doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2022.08.007

Key clinical point: A majority of women with preterm preeclampsia showed persistent cardiovascular morbidity at 6 months postpartum, which may have significant implications to long-term cardiovascular health.

Major finding: At 6 months postpartum, diastolic dysfunction, increased total vascular resistance (TVR), and persistent left ventricular remodeling were observed in 61%, 75%, and 41% of women, respectively, with 46% of women with no pre-existing hypertension having de novo hypertension and only 5% of women having a completely normal echocardiogram. A significant association was observed between prolonged preeclampsia duration and increased TVR at 6 months (P = .02).

Study details: Findings are from a sub-study of PICk-UP trial involving 44 postnatal women with preterm preeclampsia who delivered before 37 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Medical Research Council, UK. The authors declared no competing financial interests.

Source: Ormesher L et al. Postnatal cardiovascular morbidity following preterm pre-eclampsia: An observational study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;30:68-81 (Aug 17). Doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2022.08.007

Consistent increase in incidence of acute high-risk chest pain diseases during pregnancy and puerperium

Key clinical point: The incidence of acute high-risk chest pain (AHRCP) diseases during pregnancy and puerperium has increased consistently over a decade, with advanced maternal age being a significant risk factor.

Major finding: The incidence of AHRCP diseases during pregnancy and puerperium increased from 79.92/100,000 hospitalizations in 2008 to 114.79/100,000 hospitalizations in 2017 (Ptrend < .0001), with pulmonary embolism (86.5%) occurring 10-fold and 26-fold more frequently than acute myocardial infarction (9.6%) and aortic dissection (3.3%), respectively. Maternal age over 45 years was a significant risk factor (odds ratio 4.25; 95% CI 3.80-4.75).

Study details: Findings are from an observational analysis of 41,174,101 patients hospitalized for pregnancy and puerperium, of which 40,285 were diagnosed with AHRCP diseases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the 3-Year Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health System in Shanghai (2020–2022) and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu S et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute high-risk chest pain diseases during pregnancy and puerperium. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:968964 (Aug 11). Doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.968964

Key clinical point: The incidence of acute high-risk chest pain (AHRCP) diseases during pregnancy and puerperium has increased consistently over a decade, with advanced maternal age being a significant risk factor.

Major finding: The incidence of AHRCP diseases during pregnancy and puerperium increased from 79.92/100,000 hospitalizations in 2008 to 114.79/100,000 hospitalizations in 2017 (Ptrend < .0001), with pulmonary embolism (86.5%) occurring 10-fold and 26-fold more frequently than acute myocardial infarction (9.6%) and aortic dissection (3.3%), respectively. Maternal age over 45 years was a significant risk factor (odds ratio 4.25; 95% CI 3.80-4.75).

Study details: Findings are from an observational analysis of 41,174,101 patients hospitalized for pregnancy and puerperium, of which 40,285 were diagnosed with AHRCP diseases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the 3-Year Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health System in Shanghai (2020–2022) and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu S et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute high-risk chest pain diseases during pregnancy and puerperium. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:968964 (Aug 11). Doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.968964

Key clinical point: The incidence of acute high-risk chest pain (AHRCP) diseases during pregnancy and puerperium has increased consistently over a decade, with advanced maternal age being a significant risk factor.

Major finding: The incidence of AHRCP diseases during pregnancy and puerperium increased from 79.92/100,000 hospitalizations in 2008 to 114.79/100,000 hospitalizations in 2017 (Ptrend < .0001), with pulmonary embolism (86.5%) occurring 10-fold and 26-fold more frequently than acute myocardial infarction (9.6%) and aortic dissection (3.3%), respectively. Maternal age over 45 years was a significant risk factor (odds ratio 4.25; 95% CI 3.80-4.75).

Study details: Findings are from an observational analysis of 41,174,101 patients hospitalized for pregnancy and puerperium, of which 40,285 were diagnosed with AHRCP diseases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the 3-Year Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health System in Shanghai (2020–2022) and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu S et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute high-risk chest pain diseases during pregnancy and puerperium. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:968964 (Aug 11). Doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.968964

Evidence spanning 2 decades reveals trend changes in risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage

Key clinical point: Analysis over 2 decades demonstrated trend changes in individual contribution of risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, with perineal or vaginal tears increasing, large for gestational age neonate decreasing, and other risk factors remaining stable.

Major finding: The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage increased from 0.5% in 1988 to 0.6% in 2014. Among risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, perineal or vaginal tear demonstrated a rising trend (P = .01), delivery of large for gestational age neonate demonstrated a declining trend (P < .001), and other risk factors, such as preeclampsia, vacuum extraction delivery, and retained placenta, remained stable during the study period.

Study details: Findings are from a population-based, retrospective, nested, case-control study including 285,992 pregnancies, of which 1684 were complicated by postpartum hemorrhage.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sade S et al. Trend changes in the individual contribution of risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage over more than two decades. Matern Child Health J. 2022 (Aug 24). Doi: 10.1007/s10995-022-03461-y

Key clinical point: Analysis over 2 decades demonstrated trend changes in individual contribution of risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, with perineal or vaginal tears increasing, large for gestational age neonate decreasing, and other risk factors remaining stable.

Major finding: The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage increased from 0.5% in 1988 to 0.6% in 2014. Among risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, perineal or vaginal tear demonstrated a rising trend (P = .01), delivery of large for gestational age neonate demonstrated a declining trend (P < .001), and other risk factors, such as preeclampsia, vacuum extraction delivery, and retained placenta, remained stable during the study period.

Study details: Findings are from a population-based, retrospective, nested, case-control study including 285,992 pregnancies, of which 1684 were complicated by postpartum hemorrhage.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sade S et al. Trend changes in the individual contribution of risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage over more than two decades. Matern Child Health J. 2022 (Aug 24). Doi: 10.1007/s10995-022-03461-y

Key clinical point: Analysis over 2 decades demonstrated trend changes in individual contribution of risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, with perineal or vaginal tears increasing, large for gestational age neonate decreasing, and other risk factors remaining stable.

Major finding: The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage increased from 0.5% in 1988 to 0.6% in 2014. Among risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage, perineal or vaginal tear demonstrated a rising trend (P = .01), delivery of large for gestational age neonate demonstrated a declining trend (P < .001), and other risk factors, such as preeclampsia, vacuum extraction delivery, and retained placenta, remained stable during the study period.

Study details: Findings are from a population-based, retrospective, nested, case-control study including 285,992 pregnancies, of which 1684 were complicated by postpartum hemorrhage.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sade S et al. Trend changes in the individual contribution of risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage over more than two decades. Matern Child Health J. 2022 (Aug 24). Doi: 10.1007/s10995-022-03461-y

Risk factors for intrauterine tamponade failure in women with postpartum hemorrhage

Key clinical point: Cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, and uterine rupture were independently associated with a higher risk for intrauterine tamponade failure in women with deliveries complicated by postpartum hemorrhage.

Major finding: Intrauterine tamponade failure rate was 11.1%. The risk for intrauterine tamponade failure was higher in women with cesarean delivery (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.2; 95% CI 2.9-6.0), preeclampsia (aOR 2.3; 95% CI 1.3-3.9), and uterine rupture (aOR 14.1; 95% CI 2.4-83.0).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based retrospective cohort study including 1761 women with deliveries complicated by postpartum hemorrhage who underwent intrauterine tamponade within 24 hours of postpartum hemorrhage to manage persistent bleeding.

Disclosures: This study did not report any source of funding. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Gibier M et al. Risk factors for intrauterine tamponade failure in postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(3):439-446 (Aug 3). Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004888

Key clinical point: Cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, and uterine rupture were independently associated with a higher risk for intrauterine tamponade failure in women with deliveries complicated by postpartum hemorrhage.

Major finding: Intrauterine tamponade failure rate was 11.1%. The risk for intrauterine tamponade failure was higher in women with cesarean delivery (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.2; 95% CI 2.9-6.0), preeclampsia (aOR 2.3; 95% CI 1.3-3.9), and uterine rupture (aOR 14.1; 95% CI 2.4-83.0).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based retrospective cohort study including 1761 women with deliveries complicated by postpartum hemorrhage who underwent intrauterine tamponade within 24 hours of postpartum hemorrhage to manage persistent bleeding.

Disclosures: This study did not report any source of funding. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Gibier M et al. Risk factors for intrauterine tamponade failure in postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(3):439-446 (Aug 3). Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004888

Key clinical point: Cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, and uterine rupture were independently associated with a higher risk for intrauterine tamponade failure in women with deliveries complicated by postpartum hemorrhage.

Major finding: Intrauterine tamponade failure rate was 11.1%. The risk for intrauterine tamponade failure was higher in women with cesarean delivery (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.2; 95% CI 2.9-6.0), preeclampsia (aOR 2.3; 95% CI 1.3-3.9), and uterine rupture (aOR 14.1; 95% CI 2.4-83.0).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based retrospective cohort study including 1761 women with deliveries complicated by postpartum hemorrhage who underwent intrauterine tamponade within 24 hours of postpartum hemorrhage to manage persistent bleeding.

Disclosures: This study did not report any source of funding. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Gibier M et al. Risk factors for intrauterine tamponade failure in postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(3):439-446 (Aug 3). Doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004888