User login

Sublingual film well tolerated for Parkinson ‘off’ episodes

new research shows.

“The bottom line was that the majority of patients did not have dose-limiting nausea or vomiting,” said coinvestigator William Ondo, MD, from Houston Methodist Neurological Institute. “And although it really did not compare in a prospective, placebo-controlled manner use of [trimethobenzamide antiemetic] ... versus not using [it], anecdotally and based on historic data, nausea really seemed to be about the same even without the antinausea medication.”

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

This study was the dose-titration phase to determine the effective and tolerable dose of the drug as part of a longer study looking at safety and efficacy.

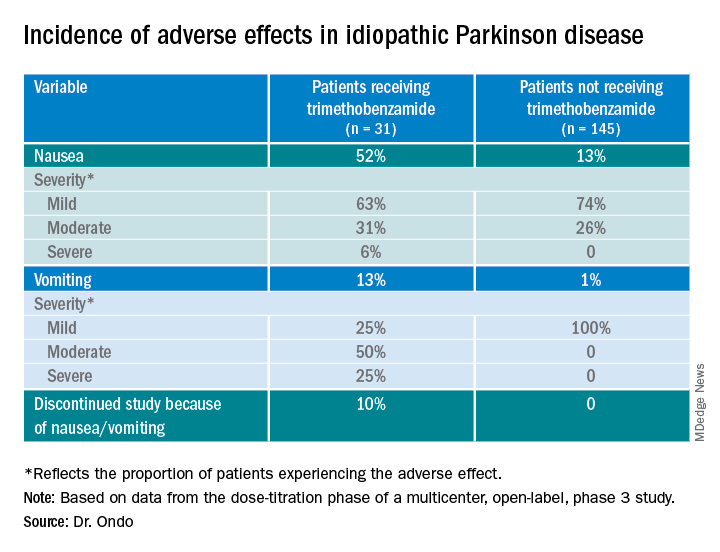

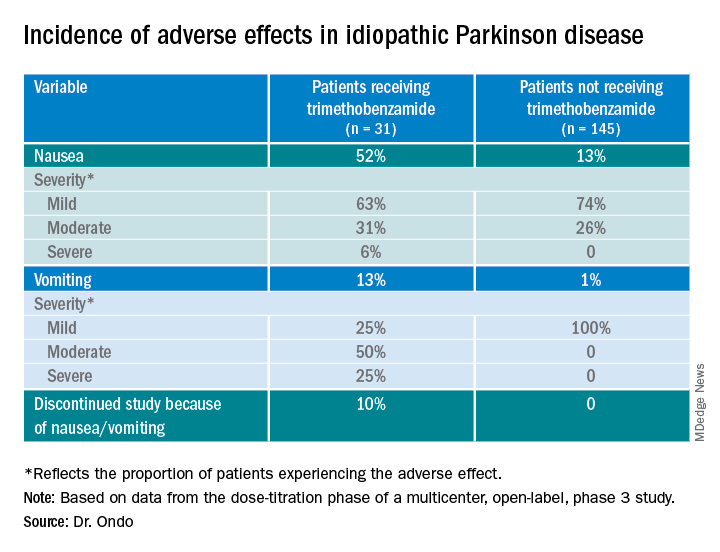

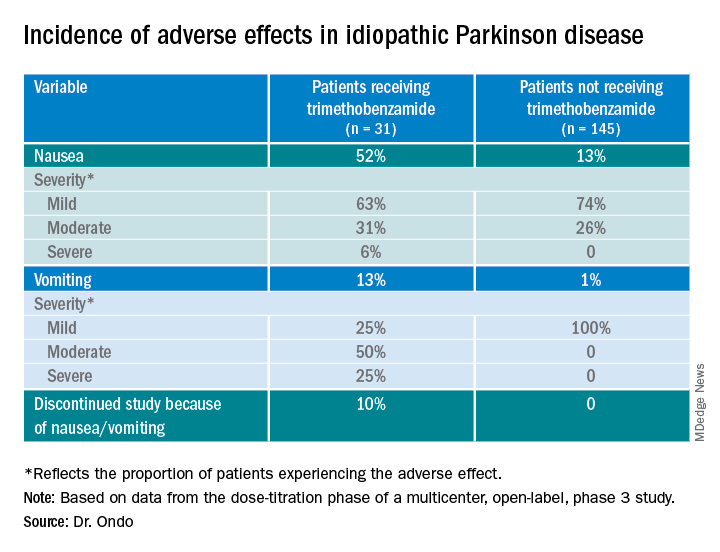

Only 13% of patients experienced nausea and/or vomiting, and of those, 74% cases were of mild severity and 26% were of moderate severity. These rates of nausea/vomiting were lower than those seen when trimethobenzamide (Tigan, Pfizer) was needed to be administered during the titration period, at the discretion of the investigator.

This multicenter, ongoing, open-label, phase 3 study enrolled 176 patients (mean age, 64.4 years) who had idiopathic Parkinson’s disease for a mean of 8.0 years and had no prior exposure to SL-apo, with modified Hoehn and Yahr stage 1-3 disease (83% stage 2 or 2.5 during “on” time).

Study participants had Mini-Mental State Examination scores greater than 25, were receiving stable doses of levodopa/carbidopa, and had 1 or more (mean, 4.2) “off” episodes per day with a total daily “off” time of 2 hours or more. Patients with mouth cankers or sores within 30 days of screening were excluded.

Open-label dose titration occurred during sequential office visits while patients were “off,” with escalating doses of 10-35 mg in 5-mg increments to determine a tolerable dose leading to a full “on” period within 45 minutes. Patients self-administered this achieved dose of SL-apo for up to five “off” episodes per day with a minimum of 2 hours between doses for the full 48-week study period.

The study protocol prohibited antiemetic use except when clinically warranted at the investigator’s discretion. Of the 176 patients, 31 (18%) received the antiemetic trimethobenzamide and 145 (82%) did not.

Of the 176 patients, 76% received their effective and tolerated dose within the first three doses. Just over half (55%) received 10 mg or 15 mg. Only 24% received the highest doses of 25 mg or 30 mg.

About 52%of patients who received trimethobenzamide experienced treatment-related nausea and 13% experienced vomiting; in comparison, 13% not receiving trimethobenzamide had nausea and 1% had vomiting. About 10%of patients in the former group and none in the latter discontinued the study because of nausea and/or vomiting.

The apomorphine sublingual film has “the advantage of ease of use compared to the injectable form,” Dr. Ondo said. “I think the injectable form, purely based on anecdotal experience, might start to work a minute or 2 faster than the sublingual form, but overall I would say efficacy as far as potency of turning ‘on’ and consistency of turning ‘on’ is comparable.”

In addition to the known adverse effects of nausea, vomiting, and hypotension with the use of any apomorphine, he said that long-term use of the sublingual form can lead to gingival irritation. Two recommendations are to place the film in a different site and to use a more basic toothpaste, such as one containing baking powder, because irritation may result from the acidity of the apomorphine.

Good news

Commenting on the study, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, from Boston University, noted that the drug label reports that “13%-15% had oropharyngeal soft tissue swelling or pain ... and 7% had oral ulcers and stomatitis.”

In addition, oral trimethobenzamide has been discontinued, although an injectable form is still available. This situation may present a problem, she said. “Most antinausea drugs block dopamine, so ... I would say they’re contraindicated for treating people with Parkinson’s disease. But trimethobenzamide in particular is one that we often reach for. ... But that appears to be constrained and may, in fact, be expensive for patients.”

Turning to the study findings, she said they suggest that “not everyone needs prophylactic use of trimethobenzamide before they take the apomorphine sublingual film, which is good news that helps doctors try to decide whether or not it’s reasonable to recommend people trying it without the trimethobenzamide.”

Although some patients did experience mild nausea, she said the fact that no needle is involved may attract some patients. Moreover, taking this medication may be easier than administering an injection during an “off” episode.

Dr. Ondo is a consultant for Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Shih had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

“The bottom line was that the majority of patients did not have dose-limiting nausea or vomiting,” said coinvestigator William Ondo, MD, from Houston Methodist Neurological Institute. “And although it really did not compare in a prospective, placebo-controlled manner use of [trimethobenzamide antiemetic] ... versus not using [it], anecdotally and based on historic data, nausea really seemed to be about the same even without the antinausea medication.”

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

This study was the dose-titration phase to determine the effective and tolerable dose of the drug as part of a longer study looking at safety and efficacy.

Only 13% of patients experienced nausea and/or vomiting, and of those, 74% cases were of mild severity and 26% were of moderate severity. These rates of nausea/vomiting were lower than those seen when trimethobenzamide (Tigan, Pfizer) was needed to be administered during the titration period, at the discretion of the investigator.

This multicenter, ongoing, open-label, phase 3 study enrolled 176 patients (mean age, 64.4 years) who had idiopathic Parkinson’s disease for a mean of 8.0 years and had no prior exposure to SL-apo, with modified Hoehn and Yahr stage 1-3 disease (83% stage 2 or 2.5 during “on” time).

Study participants had Mini-Mental State Examination scores greater than 25, were receiving stable doses of levodopa/carbidopa, and had 1 or more (mean, 4.2) “off” episodes per day with a total daily “off” time of 2 hours or more. Patients with mouth cankers or sores within 30 days of screening were excluded.

Open-label dose titration occurred during sequential office visits while patients were “off,” with escalating doses of 10-35 mg in 5-mg increments to determine a tolerable dose leading to a full “on” period within 45 minutes. Patients self-administered this achieved dose of SL-apo for up to five “off” episodes per day with a minimum of 2 hours between doses for the full 48-week study period.

The study protocol prohibited antiemetic use except when clinically warranted at the investigator’s discretion. Of the 176 patients, 31 (18%) received the antiemetic trimethobenzamide and 145 (82%) did not.

Of the 176 patients, 76% received their effective and tolerated dose within the first three doses. Just over half (55%) received 10 mg or 15 mg. Only 24% received the highest doses of 25 mg or 30 mg.

About 52%of patients who received trimethobenzamide experienced treatment-related nausea and 13% experienced vomiting; in comparison, 13% not receiving trimethobenzamide had nausea and 1% had vomiting. About 10%of patients in the former group and none in the latter discontinued the study because of nausea and/or vomiting.

The apomorphine sublingual film has “the advantage of ease of use compared to the injectable form,” Dr. Ondo said. “I think the injectable form, purely based on anecdotal experience, might start to work a minute or 2 faster than the sublingual form, but overall I would say efficacy as far as potency of turning ‘on’ and consistency of turning ‘on’ is comparable.”

In addition to the known adverse effects of nausea, vomiting, and hypotension with the use of any apomorphine, he said that long-term use of the sublingual form can lead to gingival irritation. Two recommendations are to place the film in a different site and to use a more basic toothpaste, such as one containing baking powder, because irritation may result from the acidity of the apomorphine.

Good news

Commenting on the study, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, from Boston University, noted that the drug label reports that “13%-15% had oropharyngeal soft tissue swelling or pain ... and 7% had oral ulcers and stomatitis.”

In addition, oral trimethobenzamide has been discontinued, although an injectable form is still available. This situation may present a problem, she said. “Most antinausea drugs block dopamine, so ... I would say they’re contraindicated for treating people with Parkinson’s disease. But trimethobenzamide in particular is one that we often reach for. ... But that appears to be constrained and may, in fact, be expensive for patients.”

Turning to the study findings, she said they suggest that “not everyone needs prophylactic use of trimethobenzamide before they take the apomorphine sublingual film, which is good news that helps doctors try to decide whether or not it’s reasonable to recommend people trying it without the trimethobenzamide.”

Although some patients did experience mild nausea, she said the fact that no needle is involved may attract some patients. Moreover, taking this medication may be easier than administering an injection during an “off” episode.

Dr. Ondo is a consultant for Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Shih had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

“The bottom line was that the majority of patients did not have dose-limiting nausea or vomiting,” said coinvestigator William Ondo, MD, from Houston Methodist Neurological Institute. “And although it really did not compare in a prospective, placebo-controlled manner use of [trimethobenzamide antiemetic] ... versus not using [it], anecdotally and based on historic data, nausea really seemed to be about the same even without the antinausea medication.”

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

This study was the dose-titration phase to determine the effective and tolerable dose of the drug as part of a longer study looking at safety and efficacy.

Only 13% of patients experienced nausea and/or vomiting, and of those, 74% cases were of mild severity and 26% were of moderate severity. These rates of nausea/vomiting were lower than those seen when trimethobenzamide (Tigan, Pfizer) was needed to be administered during the titration period, at the discretion of the investigator.

This multicenter, ongoing, open-label, phase 3 study enrolled 176 patients (mean age, 64.4 years) who had idiopathic Parkinson’s disease for a mean of 8.0 years and had no prior exposure to SL-apo, with modified Hoehn and Yahr stage 1-3 disease (83% stage 2 or 2.5 during “on” time).

Study participants had Mini-Mental State Examination scores greater than 25, were receiving stable doses of levodopa/carbidopa, and had 1 or more (mean, 4.2) “off” episodes per day with a total daily “off” time of 2 hours or more. Patients with mouth cankers or sores within 30 days of screening were excluded.

Open-label dose titration occurred during sequential office visits while patients were “off,” with escalating doses of 10-35 mg in 5-mg increments to determine a tolerable dose leading to a full “on” period within 45 minutes. Patients self-administered this achieved dose of SL-apo for up to five “off” episodes per day with a minimum of 2 hours between doses for the full 48-week study period.

The study protocol prohibited antiemetic use except when clinically warranted at the investigator’s discretion. Of the 176 patients, 31 (18%) received the antiemetic trimethobenzamide and 145 (82%) did not.

Of the 176 patients, 76% received their effective and tolerated dose within the first three doses. Just over half (55%) received 10 mg or 15 mg. Only 24% received the highest doses of 25 mg or 30 mg.

About 52%of patients who received trimethobenzamide experienced treatment-related nausea and 13% experienced vomiting; in comparison, 13% not receiving trimethobenzamide had nausea and 1% had vomiting. About 10%of patients in the former group and none in the latter discontinued the study because of nausea and/or vomiting.

The apomorphine sublingual film has “the advantage of ease of use compared to the injectable form,” Dr. Ondo said. “I think the injectable form, purely based on anecdotal experience, might start to work a minute or 2 faster than the sublingual form, but overall I would say efficacy as far as potency of turning ‘on’ and consistency of turning ‘on’ is comparable.”

In addition to the known adverse effects of nausea, vomiting, and hypotension with the use of any apomorphine, he said that long-term use of the sublingual form can lead to gingival irritation. Two recommendations are to place the film in a different site and to use a more basic toothpaste, such as one containing baking powder, because irritation may result from the acidity of the apomorphine.

Good news

Commenting on the study, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, from Boston University, noted that the drug label reports that “13%-15% had oropharyngeal soft tissue swelling or pain ... and 7% had oral ulcers and stomatitis.”

In addition, oral trimethobenzamide has been discontinued, although an injectable form is still available. This situation may present a problem, she said. “Most antinausea drugs block dopamine, so ... I would say they’re contraindicated for treating people with Parkinson’s disease. But trimethobenzamide in particular is one that we often reach for. ... But that appears to be constrained and may, in fact, be expensive for patients.”

Turning to the study findings, she said they suggest that “not everyone needs prophylactic use of trimethobenzamide before they take the apomorphine sublingual film, which is good news that helps doctors try to decide whether or not it’s reasonable to recommend people trying it without the trimethobenzamide.”

Although some patients did experience mild nausea, she said the fact that no needle is involved may attract some patients. Moreover, taking this medication may be easier than administering an injection during an “off” episode.

Dr. Ondo is a consultant for Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Shih had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Survey identifies clinicians’ unease with genetic testing

Before getting to work on developing guidelines for genetic testing in Parkinson’s disease, a task force of the Movement Disorders Society surveyed members worldwide to identify concerns they have about using genetic testing in practice. In results presented as a late-breaking abstract at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders,

“Some of the major outstanding issues are the clinical actionability of genetic testing – and this was highlighted by some survey participants,” senior study author Rachel Saunders-Pullman, MD, MPH, professor of neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview. The issue is “dynamic,” and will change even more radically when genetic therapies for Parkinson’s disease become available. “It is planned that, in the development of the MDS Task Force guidelines, scenarios which outline the changes in consideration of testing will depend on the availability of clinically actionable data,” she said.

Barriers to genetic testing

The MDS Task Force for Genetic Testing in Parkinson Disease conducted the survey, completed online by 568 MDS members. Respondents were from the four regions from which the MDS draws members: Africa, Europe, Asia/Oceania, and Pan-America. Half of the respondents considered themselves movement disorder specialists and 31% as general neurologists, said Maggie Markgraf, research coordinator at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York, who presented the survey findings.

Barriers to genetic testing that the clinicians cited included cost (57%), lack of availability of genetic counseling (37%), time for testing (20%) or time for counseling (17%). About 14%also cited a lack of knowledge, and only 8.5 % said they saw no barriers for genetic testing. Other concerns included a lack of therapeutic options if tests are positive and low overall positivity rates.

“Perceived barriers for general neurologists differed slightly, with limited knowledge being the most widely reported barrier, followed closely by cost and access to testing and genetic counseling,” Ms. Markgraf said.

Respondents were also asked to identify what they thought their patients perceived as barriers to genetic testing. The major one was cost (65%), followed by limited knowledge about genetics (43%), lack of access to genetic counseling (34%), and lack of access to testing separate from cost (30%). “Across all MDS regions, the perceived level of a patient’s knowledge about genetic testing is considered to be exceedingly low,” Ms. Markgraf said.

Europe had the highest availability to genetic tests, with 41.8% saying they’re accessible to general neurologists, followed by Asia/Oceania (31%) and Pan-America (30%).

“The area of most unmet need when it comes to PD genetic testing was cost for each MDS region, although the intertwined issue of access was also high, and over 50% reported that knowledge was an unmet need in their region,” Dr. Saunders-Pullman said.

Insurance coverage was another issue the survey respondents identified. In Europe, 53.6% said insurance or government programs cover genetic testing for PD, while only 14% in Pan-America and 10.3% in Asia/Oceania (and 0% in Africa) said such coverage was available.

“While there are limitations to this study, greater awareness of availability and barriers to genetic testing and counseling across different regions, as well as disparities among regions, will help inform development of the MDS Task Force guidelines,” Dr. Saunders-Pullman said.

Unmet needs

Connie Marras, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology at the University of Toronto, noted the survey suggested neurologists exhibit a “lack of comfort or lack of time” with genetic testing and counseling for Parkinson’s disease. “Even if we make genetic testing more widely available, we need health care providers that are comfortable and available to counsel patients before and after the testing, and clearly these are unmet needs,” Dr. Marras said in an interview.

“To date, pharmacologic treatment of Parkinson’s disease did not depend on genetics,” Dr. Marras said. “This may well change in the near future with treatments specifically targeting mechanisms related to two of the most common genetic risk factors for PD: LRRK2 and GBA gene variants being in clinical trials.” These developments may soon raise the urgency to reduce barriers to genetic testing.

Dr. Saunders-Pullman and Dr. Marras have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Before getting to work on developing guidelines for genetic testing in Parkinson’s disease, a task force of the Movement Disorders Society surveyed members worldwide to identify concerns they have about using genetic testing in practice. In results presented as a late-breaking abstract at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders,

“Some of the major outstanding issues are the clinical actionability of genetic testing – and this was highlighted by some survey participants,” senior study author Rachel Saunders-Pullman, MD, MPH, professor of neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview. The issue is “dynamic,” and will change even more radically when genetic therapies for Parkinson’s disease become available. “It is planned that, in the development of the MDS Task Force guidelines, scenarios which outline the changes in consideration of testing will depend on the availability of clinically actionable data,” she said.

Barriers to genetic testing

The MDS Task Force for Genetic Testing in Parkinson Disease conducted the survey, completed online by 568 MDS members. Respondents were from the four regions from which the MDS draws members: Africa, Europe, Asia/Oceania, and Pan-America. Half of the respondents considered themselves movement disorder specialists and 31% as general neurologists, said Maggie Markgraf, research coordinator at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York, who presented the survey findings.

Barriers to genetic testing that the clinicians cited included cost (57%), lack of availability of genetic counseling (37%), time for testing (20%) or time for counseling (17%). About 14%also cited a lack of knowledge, and only 8.5 % said they saw no barriers for genetic testing. Other concerns included a lack of therapeutic options if tests are positive and low overall positivity rates.

“Perceived barriers for general neurologists differed slightly, with limited knowledge being the most widely reported barrier, followed closely by cost and access to testing and genetic counseling,” Ms. Markgraf said.

Respondents were also asked to identify what they thought their patients perceived as barriers to genetic testing. The major one was cost (65%), followed by limited knowledge about genetics (43%), lack of access to genetic counseling (34%), and lack of access to testing separate from cost (30%). “Across all MDS regions, the perceived level of a patient’s knowledge about genetic testing is considered to be exceedingly low,” Ms. Markgraf said.

Europe had the highest availability to genetic tests, with 41.8% saying they’re accessible to general neurologists, followed by Asia/Oceania (31%) and Pan-America (30%).

“The area of most unmet need when it comes to PD genetic testing was cost for each MDS region, although the intertwined issue of access was also high, and over 50% reported that knowledge was an unmet need in their region,” Dr. Saunders-Pullman said.

Insurance coverage was another issue the survey respondents identified. In Europe, 53.6% said insurance or government programs cover genetic testing for PD, while only 14% in Pan-America and 10.3% in Asia/Oceania (and 0% in Africa) said such coverage was available.

“While there are limitations to this study, greater awareness of availability and barriers to genetic testing and counseling across different regions, as well as disparities among regions, will help inform development of the MDS Task Force guidelines,” Dr. Saunders-Pullman said.

Unmet needs

Connie Marras, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology at the University of Toronto, noted the survey suggested neurologists exhibit a “lack of comfort or lack of time” with genetic testing and counseling for Parkinson’s disease. “Even if we make genetic testing more widely available, we need health care providers that are comfortable and available to counsel patients before and after the testing, and clearly these are unmet needs,” Dr. Marras said in an interview.

“To date, pharmacologic treatment of Parkinson’s disease did not depend on genetics,” Dr. Marras said. “This may well change in the near future with treatments specifically targeting mechanisms related to two of the most common genetic risk factors for PD: LRRK2 and GBA gene variants being in clinical trials.” These developments may soon raise the urgency to reduce barriers to genetic testing.

Dr. Saunders-Pullman and Dr. Marras have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Before getting to work on developing guidelines for genetic testing in Parkinson’s disease, a task force of the Movement Disorders Society surveyed members worldwide to identify concerns they have about using genetic testing in practice. In results presented as a late-breaking abstract at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders,

“Some of the major outstanding issues are the clinical actionability of genetic testing – and this was highlighted by some survey participants,” senior study author Rachel Saunders-Pullman, MD, MPH, professor of neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview. The issue is “dynamic,” and will change even more radically when genetic therapies for Parkinson’s disease become available. “It is planned that, in the development of the MDS Task Force guidelines, scenarios which outline the changes in consideration of testing will depend on the availability of clinically actionable data,” she said.

Barriers to genetic testing

The MDS Task Force for Genetic Testing in Parkinson Disease conducted the survey, completed online by 568 MDS members. Respondents were from the four regions from which the MDS draws members: Africa, Europe, Asia/Oceania, and Pan-America. Half of the respondents considered themselves movement disorder specialists and 31% as general neurologists, said Maggie Markgraf, research coordinator at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York, who presented the survey findings.

Barriers to genetic testing that the clinicians cited included cost (57%), lack of availability of genetic counseling (37%), time for testing (20%) or time for counseling (17%). About 14%also cited a lack of knowledge, and only 8.5 % said they saw no barriers for genetic testing. Other concerns included a lack of therapeutic options if tests are positive and low overall positivity rates.

“Perceived barriers for general neurologists differed slightly, with limited knowledge being the most widely reported barrier, followed closely by cost and access to testing and genetic counseling,” Ms. Markgraf said.

Respondents were also asked to identify what they thought their patients perceived as barriers to genetic testing. The major one was cost (65%), followed by limited knowledge about genetics (43%), lack of access to genetic counseling (34%), and lack of access to testing separate from cost (30%). “Across all MDS regions, the perceived level of a patient’s knowledge about genetic testing is considered to be exceedingly low,” Ms. Markgraf said.

Europe had the highest availability to genetic tests, with 41.8% saying they’re accessible to general neurologists, followed by Asia/Oceania (31%) and Pan-America (30%).

“The area of most unmet need when it comes to PD genetic testing was cost for each MDS region, although the intertwined issue of access was also high, and over 50% reported that knowledge was an unmet need in their region,” Dr. Saunders-Pullman said.

Insurance coverage was another issue the survey respondents identified. In Europe, 53.6% said insurance or government programs cover genetic testing for PD, while only 14% in Pan-America and 10.3% in Asia/Oceania (and 0% in Africa) said such coverage was available.

“While there are limitations to this study, greater awareness of availability and barriers to genetic testing and counseling across different regions, as well as disparities among regions, will help inform development of the MDS Task Force guidelines,” Dr. Saunders-Pullman said.

Unmet needs

Connie Marras, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology at the University of Toronto, noted the survey suggested neurologists exhibit a “lack of comfort or lack of time” with genetic testing and counseling for Parkinson’s disease. “Even if we make genetic testing more widely available, we need health care providers that are comfortable and available to counsel patients before and after the testing, and clearly these are unmet needs,” Dr. Marras said in an interview.

“To date, pharmacologic treatment of Parkinson’s disease did not depend on genetics,” Dr. Marras said. “This may well change in the near future with treatments specifically targeting mechanisms related to two of the most common genetic risk factors for PD: LRRK2 and GBA gene variants being in clinical trials.” These developments may soon raise the urgency to reduce barriers to genetic testing.

Dr. Saunders-Pullman and Dr. Marras have no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Toward ‘superhuman cognition’: The future of brain-computer interfaces

The brain is inarguably the most complex and mysterious organ in the human body.

As the epicenter of intelligence, mastermind of movement, and song for our senses, the brain is more than a 3-lb organ encased in shell and fluid. Rather, it is the crown jewel that defines the self and, broadly, humanity.

For decades now, researchers have been exploring the potential for connecting our own astounding biological “computer” with actual physical mainframes. These so-called “brain-computer interfaces” (BCIs) are showing promise in treating an array of conditions, including paralysis, deafness, stroke, and even psychiatric disorders.

Among the big players in this area of research is billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, who in 2016 founded Neuralink. The company’s short-term mission is to develop a brain-to-machine interface to help people with neurologic conditions (for example, Parkinson’s disease). The long-term mission is to steer humanity into the era of “superhuman cognition.”

But first, some neuroscience 101.

Neurons are specialized cells that transmit and receive information. The basic structure of a neuron includes the dendrite, soma, and axon. The dendrite is the signal receiver. The soma is the cell body that is connected to the dendrites and serves as a structure to pass signals. The axon, also known as the nerve fiber, transmits the signal away from the soma.

Neurons communicate with each other at the synapse (for example, axon-dendrite connection). Neurons send information to each other through action potentials. An action potential may be defined as an electric impulse that transmits down the axon, causing the release of neurotransmitters, which may consequently either inhibit or excite the next neuron (leading to the initiation of another action potential).

So how will the company and other BCI companies tap into this evolutionarily ancient system to develop an implant that will obtain and decode information output from the brain?

The Neuralink implant is composed of three parts: The Link, neural threads, and the charger.

A robotic system, controlled by a neurosurgeon, will place an implant into the brain. The Link is the central component. It processes and transmits neural signals. The micron-scale neural threads are connected to the Link and other areas of the brain. The threads also contain electrodes, which are responsible for detecting neural signals. The charger ensures the battery is charged via wireless connection.

The invasive nature of this implant allows for precise readouts of electric outputs from the brain – unlike noninvasive devices, which are less sensitive and specific. Additionally, owing to its small size, engineers and neurosurgeons can implant the device in very specific brain regions as well as customize electrode distribution.

The Neuralink implant would be paired with an application via Bluetooth connection. The goal is to enable someone with the implant to control their device or computer by simply thinking. The application offers several exercises to help guide and train individuals on how to use the implant for its intended purpose. , as well as partake in creative activities such as photography.

Existing text and speech synthesis technology are already underway. For example, Synchron, a BCI platform company, is investigating the use of Stentrode for people with severe paralysis. This neuroprosthesis was designed to help people associate thought with movement through Bluetooth technology (for example, texting, emailing, shopping, online banking). Preliminary results from a study in which the device was used for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis showed improvements in functional independence via direct thinking.

Software intended to enable high-performance handwriting utilizing BCI technology is being developed by Francis R. Willett, PhD, at Stanford (Calif.) University. The technology has also shown promise.

“We’ve learned that the brain retains its ability to prescribe fine movements a full decade after the body has lost its ability to execute those movements,” says Dr. Willett, who recently reported on results from a BCI study of handwriting conversion in an individual with full-body paralysis. Through a recurrent neural networking decoding approach, the BrainGate study participant was able to type 90 characters per minute – with an impressive 94.1% raw accuracy – using thoughts alone.

Although not a fully implantable brain device, this percutaneous implant has also been studied of its capacity to restore arm function among individuals who suffered from chronic stroke. Preliminary results from the Cortimo trials, led by Mijail D. Serruya, MD, an assistant professor at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, have been positive. Researchers implanted microelectrode arrays to decode brain signals and power motor function in a participant who had experienced a stroke 2 years earlier. The participant was able to use a powered arm brace on their paralyzed arm.

Neuralink recently released a video demonstrating the use of the interface in a monkey named Pager as it played a game with a joystick. Company researchers inserted a 1024-Electrode neural recording and data transmission device called the N1 Link into the left and right motor cortices. Using the implant, neural activity was sent to a decoder algorithm. Throughout the process, the decoder algorithm was refined and calibrated. After a few minutes, Pager was able to control the cursor on the screen using his mind instead of the joystick.

Mr. Musk hopes to develop Neuralink further to change not only the way we treat neurological disorders but also the way we interact with ourselves and our environment. It’s a lofty goal to be sure, but one that doesn’t seem outside the realm of possibility in the near future.

Known unknowns: The ethical dilemmas

One major conundrum facing the future of BCI technology is that researchers don’t fully understand the science regarding how brain signaling, artificial intelligence (AI) software, and prostheses interact. Although offloading computations improves the predictive nature of AI algorithms, there are concerns of identity and personal agency.

How do we know that an action is truly the result of one’s own thinking or, rather, the outcome of AI software? In this context, the autocorrect function while typing can be incredibly useful when we’re in a pinch for time, when we’re using one hand to type, or because of ease. However, it’s also easy to create and send out unintended or inappropriate messages.

These algorithms are designed to learn from our behavior and anticipate our next move. However, a question arises as to whether we are the authors of our own thoughts or whether we are simply the device that delivers messages under the control of external forces.

“People may question whether new personality changes they experience are truly representative of themselves or whether they are now a product of the implant (e.g., ‘Is that really me?’; ‘Have I grown as a person, or is it the technology?’). This then raises questions about agency and who we are as people,” says Kerry Bowman, PhD, a clinical bioethicist and assistant professor at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine of the University of Toronto.

It’s important to have safeguards in place to ensure the privacy of our thoughts. In an age where data is currency, it’s crucial to establish boundaries to preserve our autonomy and prevent exploitation (for example, by private companies or hackers). Although Neuralink and BCIs generally are certainly pushing the boundaries of neural engineering in profound ways, it’s important to note the biological and ethical implications of this technology.

As Dr. Bowman points out, “throughout the entire human story, under the worst of human circumstances, such as captivity and torture, the one safe ground and place for all people has been the privacy of one’s own mind. No one could ever interfere, take away, or be aware of those thoughts. However, this technology challenges one’s own privacy – that this technology (and, by extension, a company) could be aware of those thoughts.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The brain is inarguably the most complex and mysterious organ in the human body.

As the epicenter of intelligence, mastermind of movement, and song for our senses, the brain is more than a 3-lb organ encased in shell and fluid. Rather, it is the crown jewel that defines the self and, broadly, humanity.

For decades now, researchers have been exploring the potential for connecting our own astounding biological “computer” with actual physical mainframes. These so-called “brain-computer interfaces” (BCIs) are showing promise in treating an array of conditions, including paralysis, deafness, stroke, and even psychiatric disorders.

Among the big players in this area of research is billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, who in 2016 founded Neuralink. The company’s short-term mission is to develop a brain-to-machine interface to help people with neurologic conditions (for example, Parkinson’s disease). The long-term mission is to steer humanity into the era of “superhuman cognition.”

But first, some neuroscience 101.

Neurons are specialized cells that transmit and receive information. The basic structure of a neuron includes the dendrite, soma, and axon. The dendrite is the signal receiver. The soma is the cell body that is connected to the dendrites and serves as a structure to pass signals. The axon, also known as the nerve fiber, transmits the signal away from the soma.

Neurons communicate with each other at the synapse (for example, axon-dendrite connection). Neurons send information to each other through action potentials. An action potential may be defined as an electric impulse that transmits down the axon, causing the release of neurotransmitters, which may consequently either inhibit or excite the next neuron (leading to the initiation of another action potential).

So how will the company and other BCI companies tap into this evolutionarily ancient system to develop an implant that will obtain and decode information output from the brain?

The Neuralink implant is composed of three parts: The Link, neural threads, and the charger.

A robotic system, controlled by a neurosurgeon, will place an implant into the brain. The Link is the central component. It processes and transmits neural signals. The micron-scale neural threads are connected to the Link and other areas of the brain. The threads also contain electrodes, which are responsible for detecting neural signals. The charger ensures the battery is charged via wireless connection.

The invasive nature of this implant allows for precise readouts of electric outputs from the brain – unlike noninvasive devices, which are less sensitive and specific. Additionally, owing to its small size, engineers and neurosurgeons can implant the device in very specific brain regions as well as customize electrode distribution.

The Neuralink implant would be paired with an application via Bluetooth connection. The goal is to enable someone with the implant to control their device or computer by simply thinking. The application offers several exercises to help guide and train individuals on how to use the implant for its intended purpose. , as well as partake in creative activities such as photography.

Existing text and speech synthesis technology are already underway. For example, Synchron, a BCI platform company, is investigating the use of Stentrode for people with severe paralysis. This neuroprosthesis was designed to help people associate thought with movement through Bluetooth technology (for example, texting, emailing, shopping, online banking). Preliminary results from a study in which the device was used for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis showed improvements in functional independence via direct thinking.

Software intended to enable high-performance handwriting utilizing BCI technology is being developed by Francis R. Willett, PhD, at Stanford (Calif.) University. The technology has also shown promise.

“We’ve learned that the brain retains its ability to prescribe fine movements a full decade after the body has lost its ability to execute those movements,” says Dr. Willett, who recently reported on results from a BCI study of handwriting conversion in an individual with full-body paralysis. Through a recurrent neural networking decoding approach, the BrainGate study participant was able to type 90 characters per minute – with an impressive 94.1% raw accuracy – using thoughts alone.

Although not a fully implantable brain device, this percutaneous implant has also been studied of its capacity to restore arm function among individuals who suffered from chronic stroke. Preliminary results from the Cortimo trials, led by Mijail D. Serruya, MD, an assistant professor at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, have been positive. Researchers implanted microelectrode arrays to decode brain signals and power motor function in a participant who had experienced a stroke 2 years earlier. The participant was able to use a powered arm brace on their paralyzed arm.

Neuralink recently released a video demonstrating the use of the interface in a monkey named Pager as it played a game with a joystick. Company researchers inserted a 1024-Electrode neural recording and data transmission device called the N1 Link into the left and right motor cortices. Using the implant, neural activity was sent to a decoder algorithm. Throughout the process, the decoder algorithm was refined and calibrated. After a few minutes, Pager was able to control the cursor on the screen using his mind instead of the joystick.

Mr. Musk hopes to develop Neuralink further to change not only the way we treat neurological disorders but also the way we interact with ourselves and our environment. It’s a lofty goal to be sure, but one that doesn’t seem outside the realm of possibility in the near future.

Known unknowns: The ethical dilemmas

One major conundrum facing the future of BCI technology is that researchers don’t fully understand the science regarding how brain signaling, artificial intelligence (AI) software, and prostheses interact. Although offloading computations improves the predictive nature of AI algorithms, there are concerns of identity and personal agency.

How do we know that an action is truly the result of one’s own thinking or, rather, the outcome of AI software? In this context, the autocorrect function while typing can be incredibly useful when we’re in a pinch for time, when we’re using one hand to type, or because of ease. However, it’s also easy to create and send out unintended or inappropriate messages.

These algorithms are designed to learn from our behavior and anticipate our next move. However, a question arises as to whether we are the authors of our own thoughts or whether we are simply the device that delivers messages under the control of external forces.

“People may question whether new personality changes they experience are truly representative of themselves or whether they are now a product of the implant (e.g., ‘Is that really me?’; ‘Have I grown as a person, or is it the technology?’). This then raises questions about agency and who we are as people,” says Kerry Bowman, PhD, a clinical bioethicist and assistant professor at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine of the University of Toronto.

It’s important to have safeguards in place to ensure the privacy of our thoughts. In an age where data is currency, it’s crucial to establish boundaries to preserve our autonomy and prevent exploitation (for example, by private companies or hackers). Although Neuralink and BCIs generally are certainly pushing the boundaries of neural engineering in profound ways, it’s important to note the biological and ethical implications of this technology.

As Dr. Bowman points out, “throughout the entire human story, under the worst of human circumstances, such as captivity and torture, the one safe ground and place for all people has been the privacy of one’s own mind. No one could ever interfere, take away, or be aware of those thoughts. However, this technology challenges one’s own privacy – that this technology (and, by extension, a company) could be aware of those thoughts.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The brain is inarguably the most complex and mysterious organ in the human body.

As the epicenter of intelligence, mastermind of movement, and song for our senses, the brain is more than a 3-lb organ encased in shell and fluid. Rather, it is the crown jewel that defines the self and, broadly, humanity.

For decades now, researchers have been exploring the potential for connecting our own astounding biological “computer” with actual physical mainframes. These so-called “brain-computer interfaces” (BCIs) are showing promise in treating an array of conditions, including paralysis, deafness, stroke, and even psychiatric disorders.

Among the big players in this area of research is billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, who in 2016 founded Neuralink. The company’s short-term mission is to develop a brain-to-machine interface to help people with neurologic conditions (for example, Parkinson’s disease). The long-term mission is to steer humanity into the era of “superhuman cognition.”

But first, some neuroscience 101.

Neurons are specialized cells that transmit and receive information. The basic structure of a neuron includes the dendrite, soma, and axon. The dendrite is the signal receiver. The soma is the cell body that is connected to the dendrites and serves as a structure to pass signals. The axon, also known as the nerve fiber, transmits the signal away from the soma.

Neurons communicate with each other at the synapse (for example, axon-dendrite connection). Neurons send information to each other through action potentials. An action potential may be defined as an electric impulse that transmits down the axon, causing the release of neurotransmitters, which may consequently either inhibit or excite the next neuron (leading to the initiation of another action potential).

So how will the company and other BCI companies tap into this evolutionarily ancient system to develop an implant that will obtain and decode information output from the brain?

The Neuralink implant is composed of three parts: The Link, neural threads, and the charger.

A robotic system, controlled by a neurosurgeon, will place an implant into the brain. The Link is the central component. It processes and transmits neural signals. The micron-scale neural threads are connected to the Link and other areas of the brain. The threads also contain electrodes, which are responsible for detecting neural signals. The charger ensures the battery is charged via wireless connection.

The invasive nature of this implant allows for precise readouts of electric outputs from the brain – unlike noninvasive devices, which are less sensitive and specific. Additionally, owing to its small size, engineers and neurosurgeons can implant the device in very specific brain regions as well as customize electrode distribution.

The Neuralink implant would be paired with an application via Bluetooth connection. The goal is to enable someone with the implant to control their device or computer by simply thinking. The application offers several exercises to help guide and train individuals on how to use the implant for its intended purpose. , as well as partake in creative activities such as photography.

Existing text and speech synthesis technology are already underway. For example, Synchron, a BCI platform company, is investigating the use of Stentrode for people with severe paralysis. This neuroprosthesis was designed to help people associate thought with movement through Bluetooth technology (for example, texting, emailing, shopping, online banking). Preliminary results from a study in which the device was used for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis showed improvements in functional independence via direct thinking.

Software intended to enable high-performance handwriting utilizing BCI technology is being developed by Francis R. Willett, PhD, at Stanford (Calif.) University. The technology has also shown promise.

“We’ve learned that the brain retains its ability to prescribe fine movements a full decade after the body has lost its ability to execute those movements,” says Dr. Willett, who recently reported on results from a BCI study of handwriting conversion in an individual with full-body paralysis. Through a recurrent neural networking decoding approach, the BrainGate study participant was able to type 90 characters per minute – with an impressive 94.1% raw accuracy – using thoughts alone.

Although not a fully implantable brain device, this percutaneous implant has also been studied of its capacity to restore arm function among individuals who suffered from chronic stroke. Preliminary results from the Cortimo trials, led by Mijail D. Serruya, MD, an assistant professor at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, have been positive. Researchers implanted microelectrode arrays to decode brain signals and power motor function in a participant who had experienced a stroke 2 years earlier. The participant was able to use a powered arm brace on their paralyzed arm.

Neuralink recently released a video demonstrating the use of the interface in a monkey named Pager as it played a game with a joystick. Company researchers inserted a 1024-Electrode neural recording and data transmission device called the N1 Link into the left and right motor cortices. Using the implant, neural activity was sent to a decoder algorithm. Throughout the process, the decoder algorithm was refined and calibrated. After a few minutes, Pager was able to control the cursor on the screen using his mind instead of the joystick.

Mr. Musk hopes to develop Neuralink further to change not only the way we treat neurological disorders but also the way we interact with ourselves and our environment. It’s a lofty goal to be sure, but one that doesn’t seem outside the realm of possibility in the near future.

Known unknowns: The ethical dilemmas

One major conundrum facing the future of BCI technology is that researchers don’t fully understand the science regarding how brain signaling, artificial intelligence (AI) software, and prostheses interact. Although offloading computations improves the predictive nature of AI algorithms, there are concerns of identity and personal agency.

How do we know that an action is truly the result of one’s own thinking or, rather, the outcome of AI software? In this context, the autocorrect function while typing can be incredibly useful when we’re in a pinch for time, when we’re using one hand to type, or because of ease. However, it’s also easy to create and send out unintended or inappropriate messages.

These algorithms are designed to learn from our behavior and anticipate our next move. However, a question arises as to whether we are the authors of our own thoughts or whether we are simply the device that delivers messages under the control of external forces.

“People may question whether new personality changes they experience are truly representative of themselves or whether they are now a product of the implant (e.g., ‘Is that really me?’; ‘Have I grown as a person, or is it the technology?’). This then raises questions about agency and who we are as people,” says Kerry Bowman, PhD, a clinical bioethicist and assistant professor at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine of the University of Toronto.

It’s important to have safeguards in place to ensure the privacy of our thoughts. In an age where data is currency, it’s crucial to establish boundaries to preserve our autonomy and prevent exploitation (for example, by private companies or hackers). Although Neuralink and BCIs generally are certainly pushing the boundaries of neural engineering in profound ways, it’s important to note the biological and ethical implications of this technology.

As Dr. Bowman points out, “throughout the entire human story, under the worst of human circumstances, such as captivity and torture, the one safe ground and place for all people has been the privacy of one’s own mind. No one could ever interfere, take away, or be aware of those thoughts. However, this technology challenges one’s own privacy – that this technology (and, by extension, a company) could be aware of those thoughts.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonmotor symptoms common in Parkinson’s

The hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the accompanying motor symptoms, but the condition can bring other challenges. Among those are nonmotor symptoms, including depression, dementia, and even psychosis.

The culprit is Lewy bodies, which are also responsible for Lewy body dementia. “What we call Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease are caused by the same pathological process – the formation of Lewy bodies in the brain,” Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, said in an interview. Dr. Citrome discussed some of the psychiatric comorbidities associated with Parkinson’s disease at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

In fact, the association goes both ways. “Many people with Parkinson’s disease develop a dementia. Many people with Lewy body dementia develop motor symptoms that look just like Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Citrome, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at New York Medical College, Valhalla, and president of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology.

The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are generally attributable to loss of striatal dopaminergic neurons, while nonmotor symptoms can be traced to loss of neurons in nondopaminergic regions. Nonmotor symptoms – often including sleep disorders, depression, cognitive changes, and psychosis – may occur before motor symptoms. Other problems may include autonomic dysfunction, such as constipation, sexual dysfunction, sweating, or urinary retention.

Patients might not be aware that nonmotor symptoms can occur with Parkinson’s disease and may not even consider mentioning mood changes or hallucinations to their neurologist. Family members may also be unaware.

Sleep problems are common in Parkinson’s disease, including rapid eye-movement sleep behavior disorders, vivid dreams, restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and daytime somnolence. Dopamine agonists may also cause unintended sleep.

Depression is extremely common, affecting up to 90% of Parkinson’s disease patients, and this may be related to dopaminergic losses. Antidepressant medications can worsen Parkinson’s disease symptoms: Tricyclic antidepressants increase risk of adverse events from anticholinergic drugs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can exacerbate tremor and may increase risk of serotonin syndrome when combined with MAO‐B inhibitors.

Dr. Citrome was not aware of any antidepressant drugs that have been tested specifically in Parkinson’s disease patients, though “I’d be surprised if there wasn’t,” he said during the Q&A session. “There’s no one perfect antidepressant for people with depression associated with Parkinson’s disease. I would make sure to select one that they would tolerate and be willing to take and that doesn’t interfere with their treatment of their movement disorder, and (I would make sure) that there’s no drug-drug interaction,” he said.

This can include reduced working memory, learning, and planning, and generally does not manifest until at least 1 year after motor symptoms have begun. Rivastigmine is Food and Drug Administration–approved for treatment of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease.

As many as 60% of Parkinson’s disease patients suffer from psychosis at some point, often visual hallucinations or delusions, which can include beliefs of spousal infidelity.

Many clinicians prescribe quetiapine off label, but there are not compelling data to support that it reduces intensity and frequency of hallucinations and delusions, according to Dr. Citrome. However, it is relatively easy to prescribe, requiring no preauthorizations, it is inexpensive, and it may improve sleep.

The FDA approved pimavanserin in 2016 for hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson’s disease, and it doesn’t worsen motor symptoms, Dr. Citrome said. That’s because pimavanserin is a highly selective antagonist of the 5-HT2A receptor, with no effect on dopaminergic, histaminergic, adrenergic, or muscarinic receptors.

The drug improves positive symptoms beginning at days 29 and 43, compared with placebo. An analysis by Dr. Citrome’s group found a number needed to treat (NNT) of 7 to gain a benefit over placebo if the metric is a ≥ 30% reduction in baseline symptom score. The drug had an NNT of 9 to achieve a ≥ 50% reduction, and an NNT of 5 to achieve a score of much improved or very much improved on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-I) scale. In general, an NNT less than 10 suggests that a drug is clinically useful.

In contrast, the number needed to harm (NNH) represents the number of patients who would need to receive a therapy to add one adverse event, compared with placebo. A number greater than 10 indicates that the therapy may be tolerable.

Using various measures, the NNH was well over 10 for pimavanserin. With respect to somnolence, the NNH over placebo was 138, and for a weight gain of 7% or more, the NNH was 594.

Overall, the study found that 4 patients would need to be treated to achieve a benefit over placebo with respect to a ≥ 3–point improvement in the Scale of Positive Symptoms–Parkinson’s Disease (SAPS-PD), while 21 would need to receive the drug to lead to one additional discontinuation because of an adverse event, compared to placebo.

When researchers compared pimavanserin to off-label use of quetiapine, olanzapine, and clozapine, they found a Cohen’s d value of 0.50, which was better than quetiapine and olanzapine, but lower than for clozapine. However, there is no requirement of blood monitoring, and clozapine can potentially worsen motor symptoms.

Dr. Citrome’s presentation should be a reminder to neurologists that psychiatric disorders are an important patient concern, said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati, who moderated the session.

“I think this serves as a model to recognize that many neurological disorders actually present with numerous psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Nasrallah said during the meeting, presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Citrome has consulted for AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Astellas, Avanir, Axsome, BioXcel, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Lyndra, MedAvante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Ovid, Relmada, Sage, Sunovion, and Teva. He has been a speaker for most of those companies, and he holds stock in Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, J&J, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr. Nasrallah has consulted for Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Indivior, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Teva. He has served on a speakers bureau for most of those companies, in addition to that of Noven.

The hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the accompanying motor symptoms, but the condition can bring other challenges. Among those are nonmotor symptoms, including depression, dementia, and even psychosis.

The culprit is Lewy bodies, which are also responsible for Lewy body dementia. “What we call Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease are caused by the same pathological process – the formation of Lewy bodies in the brain,” Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, said in an interview. Dr. Citrome discussed some of the psychiatric comorbidities associated with Parkinson’s disease at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

In fact, the association goes both ways. “Many people with Parkinson’s disease develop a dementia. Many people with Lewy body dementia develop motor symptoms that look just like Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Citrome, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at New York Medical College, Valhalla, and president of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology.

The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are generally attributable to loss of striatal dopaminergic neurons, while nonmotor symptoms can be traced to loss of neurons in nondopaminergic regions. Nonmotor symptoms – often including sleep disorders, depression, cognitive changes, and psychosis – may occur before motor symptoms. Other problems may include autonomic dysfunction, such as constipation, sexual dysfunction, sweating, or urinary retention.

Patients might not be aware that nonmotor symptoms can occur with Parkinson’s disease and may not even consider mentioning mood changes or hallucinations to their neurologist. Family members may also be unaware.

Sleep problems are common in Parkinson’s disease, including rapid eye-movement sleep behavior disorders, vivid dreams, restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and daytime somnolence. Dopamine agonists may also cause unintended sleep.

Depression is extremely common, affecting up to 90% of Parkinson’s disease patients, and this may be related to dopaminergic losses. Antidepressant medications can worsen Parkinson’s disease symptoms: Tricyclic antidepressants increase risk of adverse events from anticholinergic drugs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can exacerbate tremor and may increase risk of serotonin syndrome when combined with MAO‐B inhibitors.

Dr. Citrome was not aware of any antidepressant drugs that have been tested specifically in Parkinson’s disease patients, though “I’d be surprised if there wasn’t,” he said during the Q&A session. “There’s no one perfect antidepressant for people with depression associated with Parkinson’s disease. I would make sure to select one that they would tolerate and be willing to take and that doesn’t interfere with their treatment of their movement disorder, and (I would make sure) that there’s no drug-drug interaction,” he said.

This can include reduced working memory, learning, and planning, and generally does not manifest until at least 1 year after motor symptoms have begun. Rivastigmine is Food and Drug Administration–approved for treatment of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease.

As many as 60% of Parkinson’s disease patients suffer from psychosis at some point, often visual hallucinations or delusions, which can include beliefs of spousal infidelity.

Many clinicians prescribe quetiapine off label, but there are not compelling data to support that it reduces intensity and frequency of hallucinations and delusions, according to Dr. Citrome. However, it is relatively easy to prescribe, requiring no preauthorizations, it is inexpensive, and it may improve sleep.

The FDA approved pimavanserin in 2016 for hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson’s disease, and it doesn’t worsen motor symptoms, Dr. Citrome said. That’s because pimavanserin is a highly selective antagonist of the 5-HT2A receptor, with no effect on dopaminergic, histaminergic, adrenergic, or muscarinic receptors.

The drug improves positive symptoms beginning at days 29 and 43, compared with placebo. An analysis by Dr. Citrome’s group found a number needed to treat (NNT) of 7 to gain a benefit over placebo if the metric is a ≥ 30% reduction in baseline symptom score. The drug had an NNT of 9 to achieve a ≥ 50% reduction, and an NNT of 5 to achieve a score of much improved or very much improved on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-I) scale. In general, an NNT less than 10 suggests that a drug is clinically useful.

In contrast, the number needed to harm (NNH) represents the number of patients who would need to receive a therapy to add one adverse event, compared with placebo. A number greater than 10 indicates that the therapy may be tolerable.

Using various measures, the NNH was well over 10 for pimavanserin. With respect to somnolence, the NNH over placebo was 138, and for a weight gain of 7% or more, the NNH was 594.

Overall, the study found that 4 patients would need to be treated to achieve a benefit over placebo with respect to a ≥ 3–point improvement in the Scale of Positive Symptoms–Parkinson’s Disease (SAPS-PD), while 21 would need to receive the drug to lead to one additional discontinuation because of an adverse event, compared to placebo.

When researchers compared pimavanserin to off-label use of quetiapine, olanzapine, and clozapine, they found a Cohen’s d value of 0.50, which was better than quetiapine and olanzapine, but lower than for clozapine. However, there is no requirement of blood monitoring, and clozapine can potentially worsen motor symptoms.

Dr. Citrome’s presentation should be a reminder to neurologists that psychiatric disorders are an important patient concern, said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati, who moderated the session.

“I think this serves as a model to recognize that many neurological disorders actually present with numerous psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Nasrallah said during the meeting, presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Citrome has consulted for AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Astellas, Avanir, Axsome, BioXcel, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Lyndra, MedAvante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Ovid, Relmada, Sage, Sunovion, and Teva. He has been a speaker for most of those companies, and he holds stock in Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, J&J, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr. Nasrallah has consulted for Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Indivior, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Teva. He has served on a speakers bureau for most of those companies, in addition to that of Noven.

The hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the accompanying motor symptoms, but the condition can bring other challenges. Among those are nonmotor symptoms, including depression, dementia, and even psychosis.

The culprit is Lewy bodies, which are also responsible for Lewy body dementia. “What we call Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease are caused by the same pathological process – the formation of Lewy bodies in the brain,” Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, said in an interview. Dr. Citrome discussed some of the psychiatric comorbidities associated with Parkinson’s disease at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

In fact, the association goes both ways. “Many people with Parkinson’s disease develop a dementia. Many people with Lewy body dementia develop motor symptoms that look just like Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Citrome, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at New York Medical College, Valhalla, and president of the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology.

The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are generally attributable to loss of striatal dopaminergic neurons, while nonmotor symptoms can be traced to loss of neurons in nondopaminergic regions. Nonmotor symptoms – often including sleep disorders, depression, cognitive changes, and psychosis – may occur before motor symptoms. Other problems may include autonomic dysfunction, such as constipation, sexual dysfunction, sweating, or urinary retention.

Patients might not be aware that nonmotor symptoms can occur with Parkinson’s disease and may not even consider mentioning mood changes or hallucinations to their neurologist. Family members may also be unaware.

Sleep problems are common in Parkinson’s disease, including rapid eye-movement sleep behavior disorders, vivid dreams, restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and daytime somnolence. Dopamine agonists may also cause unintended sleep.

Depression is extremely common, affecting up to 90% of Parkinson’s disease patients, and this may be related to dopaminergic losses. Antidepressant medications can worsen Parkinson’s disease symptoms: Tricyclic antidepressants increase risk of adverse events from anticholinergic drugs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can exacerbate tremor and may increase risk of serotonin syndrome when combined with MAO‐B inhibitors.

Dr. Citrome was not aware of any antidepressant drugs that have been tested specifically in Parkinson’s disease patients, though “I’d be surprised if there wasn’t,” he said during the Q&A session. “There’s no one perfect antidepressant for people with depression associated with Parkinson’s disease. I would make sure to select one that they would tolerate and be willing to take and that doesn’t interfere with their treatment of their movement disorder, and (I would make sure) that there’s no drug-drug interaction,” he said.

This can include reduced working memory, learning, and planning, and generally does not manifest until at least 1 year after motor symptoms have begun. Rivastigmine is Food and Drug Administration–approved for treatment of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease.

As many as 60% of Parkinson’s disease patients suffer from psychosis at some point, often visual hallucinations or delusions, which can include beliefs of spousal infidelity.

Many clinicians prescribe quetiapine off label, but there are not compelling data to support that it reduces intensity and frequency of hallucinations and delusions, according to Dr. Citrome. However, it is relatively easy to prescribe, requiring no preauthorizations, it is inexpensive, and it may improve sleep.

The FDA approved pimavanserin in 2016 for hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson’s disease, and it doesn’t worsen motor symptoms, Dr. Citrome said. That’s because pimavanserin is a highly selective antagonist of the 5-HT2A receptor, with no effect on dopaminergic, histaminergic, adrenergic, or muscarinic receptors.

The drug improves positive symptoms beginning at days 29 and 43, compared with placebo. An analysis by Dr. Citrome’s group found a number needed to treat (NNT) of 7 to gain a benefit over placebo if the metric is a ≥ 30% reduction in baseline symptom score. The drug had an NNT of 9 to achieve a ≥ 50% reduction, and an NNT of 5 to achieve a score of much improved or very much improved on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-I) scale. In general, an NNT less than 10 suggests that a drug is clinically useful.

In contrast, the number needed to harm (NNH) represents the number of patients who would need to receive a therapy to add one adverse event, compared with placebo. A number greater than 10 indicates that the therapy may be tolerable.

Using various measures, the NNH was well over 10 for pimavanserin. With respect to somnolence, the NNH over placebo was 138, and for a weight gain of 7% or more, the NNH was 594.

Overall, the study found that 4 patients would need to be treated to achieve a benefit over placebo with respect to a ≥ 3–point improvement in the Scale of Positive Symptoms–Parkinson’s Disease (SAPS-PD), while 21 would need to receive the drug to lead to one additional discontinuation because of an adverse event, compared to placebo.

When researchers compared pimavanserin to off-label use of quetiapine, olanzapine, and clozapine, they found a Cohen’s d value of 0.50, which was better than quetiapine and olanzapine, but lower than for clozapine. However, there is no requirement of blood monitoring, and clozapine can potentially worsen motor symptoms.

Dr. Citrome’s presentation should be a reminder to neurologists that psychiatric disorders are an important patient concern, said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati, who moderated the session.

“I think this serves as a model to recognize that many neurological disorders actually present with numerous psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Nasrallah said during the meeting, presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Citrome has consulted for AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Astellas, Avanir, Axsome, BioXcel, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Lyndra, MedAvante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Ovid, Relmada, Sage, Sunovion, and Teva. He has been a speaker for most of those companies, and he holds stock in Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, J&J, Merck, and Pfizer.

Dr. Nasrallah has consulted for Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Indivior, Intra-Cellular, Janssen, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Teva. He has served on a speakers bureau for most of those companies, in addition to that of Noven.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2021

Anxiety, inactivity linked to cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s disease patients who develop anxiety early in their disease are at risk for reduced physical activity, which promotes further anxiety and cognitive decline, data from nearly 500 individuals show.

Anxiety occurs in 20%-60% of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients but often goes undiagnosed, wrote Jacob D. Jones, PhD, of California State University, San Bernardino, and colleagues.

“Anxiety can attenuate motivation to engage in physical activity leading to more anxiety and other negative cognitive outcomes,” although physical activity has been shown to improve cognitive function in PD patients, they said. However, physical activity as a mediator between anxiety and cognitive function in PD has not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in Mental Health and Physical Activity Participants were followed for up to 5 years and completed neuropsychological tests, tests of motor severity, and self-reports on anxiety and physical activity. Anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T) subscale. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). Motor severity was assessed using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Part III (UPDRS). The average age of the participants was 61 years, 65% were men, and 96% were White.

Using a direct-effect model, the researchers found that individuals whose anxiety increased during the study period also showed signs of cognitive decline. A significant between-person effect showed that individuals who were generally more anxious also scored lower on cognitive tests over the 5-year study period.

In a mediation model computed with structural equation modeling, physical activity mediated the link between anxiety and cognition, most notably household activity.

“There was a significant within-person association between anxiety and household activities, meaning that individuals who became more anxious over the 5-year study also became less active in the home,” reported Dr. Jones and colleagues.

However, no significant indirect effect was noted regarding the between-person findings of the impact of physical activity on anxiety and cognitive decline. Although more severe anxiety was associated with less activity, cognitive performance was not associated with either type of physical activity.

The presence of a within-person effect “suggests that reductions in physical activity, specifically within the first 5 years of disease onset, may be detrimental to mental health,” the researchers emphasized. Given that the study population was newly diagnosed with PD “it is likely the within-person terms are more sensitive to changes in anxiety, physical activity, and cognition that are more directly the result of the PD process, as opposed to lifestyle/preexisting traits,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of self-reports to measure physical activity, and the lack of granular information about the details of physical activity, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inclusion of only newly diagnosed PD patients, which might limit generalizability.

“Future research is warranted to understand if other modes, intensities, or complexities of physical activity impact individuals with PD in a different manner in relation to cognition,” they said.

Dr. Jones and colleagues had no disclosures. The PPMI is supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Parkinson’s disease patients who develop anxiety early in their disease are at risk for reduced physical activity, which promotes further anxiety and cognitive decline, data from nearly 500 individuals show.

Anxiety occurs in 20%-60% of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients but often goes undiagnosed, wrote Jacob D. Jones, PhD, of California State University, San Bernardino, and colleagues.

“Anxiety can attenuate motivation to engage in physical activity leading to more anxiety and other negative cognitive outcomes,” although physical activity has been shown to improve cognitive function in PD patients, they said. However, physical activity as a mediator between anxiety and cognitive function in PD has not been well studied, they noted.