User login

Have you tried a progestin for your patient’s pelvic pain?

The date of the changeover to the 10th revision of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) codes is incorrectly stated in the November 2011 Reimbursement Adviser, page 51. The date should be October 1, 2013.

To read the corrected version of this article, Click here

—The Editors

CASE

Your patient is a 26-year-old G0 woman who has a long history of progressively worsening dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. In the recent past, she was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive, and a continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive—in that order, and without appreciable relief of the pain.

Recently, the woman underwent laparoscopy, which demonstrated Stage-II endometriosis, which was ablated.

What would you prescribe for her postoperatively to alleviate symptoms?

Endometriosis will be diagnosed in approximately 8% of women of reproductive age.1 Pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and deep dyspareunia are common symptoms of endometriosis that interfere with quality of life.

Endometriosis is a chronic disease best managed by developing a life-long treatment plan. Following laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment, many experts strongly recommend postoperative hormone-suppressive therapy to reduce the risk that severe pelvic pain will recur, requiring re-operation.

Options for postoperative hormonal treatment of endometriosis include:

- an estrogen–progestin contraceptive

- a progestin (norethindrone acetate [NEA]; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA]; oral medroxyprogesterone acetate; the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system [LNG-IUS; Mirena]; and the progestin-releasing implant [Implanon])

- a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (depot leuprolide [Depot Lupron]; nafarelin nasal spray [Synarel]).

CASE Continued

Considering that both cyclic and continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives have already failed to provide adequate pain relief for your patient, you know that you should offer an alternative to her. Taking into account that progestins are significantly less costly than a GnRH agonist, a progestin formulation might, for her, be considered a first-line postoperative treatment of symptoms of endometriosis.

Options when considering a progestin

Norethindrone acetate

This agent is available in a single formulation: a 5-mg tablet; however, dosages ranging from 2.5 mg/d (half of a tablet) to 15 mg/d have been reported to be effective for relieving pain caused by endometriosis.

What is it? NEA is an androgenic progestin that suppresses luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, thus reducing production of ovarian estrogen. In the absence of ovarian estrogen, endometriosis lesions atrophy. In addition, NEA binds to, and stimulates, endometrial progestin and androgen receptors, resulting in decidualization and atrophy of both eutopic and ectopic endometrial tissue.

Importantly, NEA does not appear to cause bone loss, a phenomenon that is common with agents such as the GnRH agonists or DPMA.2-4

The research record. One randomized study, two pilot studies, and one large observational study have reported that NEA is effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

In the randomized trial, 90 women who had moderate or severe pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis, and who remained symptomatic after conservative surgery, were randomized to receive NEA, 2.5 mg/d, or a low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol, 10 μg, plus cyproterone acetate, 3 mg) daily for 12 months.5 Both treatment groups reported significant and similar decreases in dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, non-menstrual pain and dyschezia.

In a small pilot study, 40 women who had pelvic pain and colorectal endometriosis were treated with NEA 2.5 mg/d for 12 months. The drug produced significant improvement in dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dyschezia, and cyclic rectal bleeding.6

In another pilot study, women who had pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were treated with either an aromatase inhibitor (letrozole, 2.5 mg/d) plus NEA (2.5 mg/d) or NEA (2.5 mg/d) alone for 6 months. Both treatments resulted in a significant improvement in pelvic pain and deep dyspareunia. Improvement in pain scores was greater with letrozole plus NEA; patients were more satisfied with NEA monotherapy than with the combined letrozole-NEA treatment, however, because the former was associated with fewer side effects.7

In a large (n=194) observational study of the postoperative use of NEA in young women with pelvic pain and endometriosis, NEA at dosages as high as 15 mg/d significantly diminished pelvic pain and self-reported menstrual bleeding. All subjects were started on a dosage of 5 mg/d, which was increased in 2.5-mg increments every 2 weeks to achieve the goals of amenorrhea and a lessening of pelvic pain; the maximum dosage administered was 15 mg/d. Mean duration of NEA use was 13 months; 75% of subjects took the maximum prescribed dosage of 15 mg at some point during treatment. The most commonly reported side effects were weight gain (16% of women); acne (10%); mood lability (9%); and vasomotor symptoms (8%).8

In summary. NEA is effective for treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis at dosages from 2.5 mg/d to 15 mg/d. An important goal of treatment is a decrease in pain symptoms and amenorrhea; a dosage of 2.5 mg is often insufficient to reliably achieve both of those objectives.

In my practice I begin therapy at a dosage of 5 mg/d; the drug is effective for most patients at that dosage. If 5 mg/d does not reduce pain, I increase the dosage by 2.5 mg (half of a tablet) daily every 4 weeks, to a maximum dosage of 10 mg/d (two tablets). If that dosage is ineffective, I usually discontinue NEA and switch to a GnRH agonist.

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; oral medroxy-progesterone acetate

DMPA is available in two FDA-approved formulations:

- a 150-mg dose given by intramuscular injection every 3 months

- a 104-mg dose given by subcutaneous injection every 3 months.

Research. The results of two large clinical trials, comprising a total of more than 550 subjects, showed that DMPA (104 mg, SC, every 3 months) and depot leuprolide (11.25 mg, IM, every 3 months or 3.75 mg, monthly) were each equally effective in relieving dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, pelvic tenderness, and pelvic induration in women who had endometriosis.9,10

DMPA was associated with a greater rate of episodes of irregular bleeding than depot leuprolide; conversely, depot leuprolide was associated with greater loss of bone density and a higher incidence of vasomotor symptoms. Weight gain was in the range of 0.6 kg in both groups.

Of note, DPMA is much less expensive than depot leuprolide.

Another study showed that increasing the dosage of DMPA did not improve efficacy over the standard dosage11: DMPA, 150 mg IM, monthly, and DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months produced similar relief of pelvic pain.

Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate, prescribed at high dosages, is also effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In a pilot study (n=21), oral MPA, 50 mg/d for 4 months, alleviated dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, dyschezia, and pelvic tenderness and decreased pelvic nodularity. Sixty percent of subjects reported weight gain— 1.5 kg, on average.12

Progestin-releasing devices: Mirena and Implanon

Many pilot studies have reported that the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.13-17 For example:

Research. In a small clinical trial, 30 women who had pelvic pain and endometriosis were randomized to receive an LNG-IUS (Mirena) or DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months for 3 years.13 Both therapies were effective at reducing pelvic pain.

At the conclusion of the study, more women opted to retain the LNG-IUS (87%) than to continue DMPA injection (47%). Bone density was maintained in women who had the LNG-IUS placed but slightly diminished in women receiving DMPA.

In a pilot study of an etonogestrel releasing implant (Implanon), 41 women who had pelvic pain and endometriosis were randomized to receive the implant or DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months for 1 year.18 Both therapies were similarly effective at reducing pelvic pain.

Notably, irregular uterine bleeding is a common problem when the etonogestrel-releasing implant is used to treat endometriosis. Achieving amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is an important goal for women who suffer from pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

My recommendation

Most ObGyns see patients who are suffering from difficult-to-treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Many of these patients have not had a trial of a progestin, such as NEA, DMPA, or the LNG-IUS that I use in my practice.

Progestins are, as I’ve described, effective for pelvic pain. They are also relatively inexpensive and have a side-effect profile that most patients find acceptable. I recommend that you try a progestin for your patients who have refractory pelvic pain.

What is your preferred hormone treatment for women with unrelieved pelvic pain from endometriosis?

1. Missmer SA, Hankinson S, Spiegelman D, et al. The incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropomorphic and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784-796.

2. Abdalla HI, Hart DM, Lindsay R, Leggate I, Hooke A. Prevention of bone mineral loss in postmenopausal women by norethisterone. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(6):789-792.

3. Riss BJ, Lehmann HJ, Christiansen C. Norethisterone acetate in combination with estrogen: effects on the skeleton and other organs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):1101-1116.

4. Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(1):16-24.

5. Vercellini P, Pietropauolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

6. Ferrero S, Camerini G, Ragni N, Venturini PL, Biscaldi E, Remorgida V. Norethisterone acetate in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):94-100.

7. Ferrero S, Camerini G, Seracchioli R, Ragni N, Venturini PL, Remorgida V. Letrozole combined with norethisterone acetate compared with norethisterone acetate alone in the treatment of pain symptoms caused by endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3033-3341.

8. Kaser DJ, Missmer SA, Berry KF, Laufer MR. Use of norethindrone acetate alone for postoperative suppression of endometriosis symptoms [published online ahead of print December 9 2011]. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.013.

9. Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314-325.

10. Crosignani PG, Luciano A, Ray A, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):248-256.

11. Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Choksuchat C, Dhanaworavibul K, Choobun T, Bunyapipat S. Interval of injections of intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in the long-term treatment of endometriosis-associated pain: a randomized clinical trial. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68(2):116-121.

12. Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 Pt 1):323-327.

13. Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273-279.

14. Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy side-effects and continuation rates in women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intrauterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel): a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(3):789-793.

15. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993-1998.

16. Vercellini P, Aimi G, Panazza S, De Giorgi O, Pesole A, Crosignani PG. A levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(3):505-508.

17. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(2):305-309.

18. Walch K, Unfried G, Huber J, Kurz C, van Trotsenburg M, Pernicka E, Wenzl R. Implanon versus medroxyprogesterone acetate: effects on pain scores in patients with symptomatic endometriosis—a pilot study. Contraception. 2009;79(1):29-34.

The date of the changeover to the 10th revision of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) codes is incorrectly stated in the November 2011 Reimbursement Adviser, page 51. The date should be October 1, 2013.

To read the corrected version of this article, Click here

—The Editors

CASE

Your patient is a 26-year-old G0 woman who has a long history of progressively worsening dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. In the recent past, she was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive, and a continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive—in that order, and without appreciable relief of the pain.

Recently, the woman underwent laparoscopy, which demonstrated Stage-II endometriosis, which was ablated.

What would you prescribe for her postoperatively to alleviate symptoms?

Endometriosis will be diagnosed in approximately 8% of women of reproductive age.1 Pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and deep dyspareunia are common symptoms of endometriosis that interfere with quality of life.

Endometriosis is a chronic disease best managed by developing a life-long treatment plan. Following laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment, many experts strongly recommend postoperative hormone-suppressive therapy to reduce the risk that severe pelvic pain will recur, requiring re-operation.

Options for postoperative hormonal treatment of endometriosis include:

- an estrogen–progestin contraceptive

- a progestin (norethindrone acetate [NEA]; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA]; oral medroxyprogesterone acetate; the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system [LNG-IUS; Mirena]; and the progestin-releasing implant [Implanon])

- a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (depot leuprolide [Depot Lupron]; nafarelin nasal spray [Synarel]).

CASE Continued

Considering that both cyclic and continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives have already failed to provide adequate pain relief for your patient, you know that you should offer an alternative to her. Taking into account that progestins are significantly less costly than a GnRH agonist, a progestin formulation might, for her, be considered a first-line postoperative treatment of symptoms of endometriosis.

Options when considering a progestin

Norethindrone acetate

This agent is available in a single formulation: a 5-mg tablet; however, dosages ranging from 2.5 mg/d (half of a tablet) to 15 mg/d have been reported to be effective for relieving pain caused by endometriosis.

What is it? NEA is an androgenic progestin that suppresses luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, thus reducing production of ovarian estrogen. In the absence of ovarian estrogen, endometriosis lesions atrophy. In addition, NEA binds to, and stimulates, endometrial progestin and androgen receptors, resulting in decidualization and atrophy of both eutopic and ectopic endometrial tissue.

Importantly, NEA does not appear to cause bone loss, a phenomenon that is common with agents such as the GnRH agonists or DPMA.2-4

The research record. One randomized study, two pilot studies, and one large observational study have reported that NEA is effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

In the randomized trial, 90 women who had moderate or severe pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis, and who remained symptomatic after conservative surgery, were randomized to receive NEA, 2.5 mg/d, or a low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol, 10 μg, plus cyproterone acetate, 3 mg) daily for 12 months.5 Both treatment groups reported significant and similar decreases in dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, non-menstrual pain and dyschezia.

In a small pilot study, 40 women who had pelvic pain and colorectal endometriosis were treated with NEA 2.5 mg/d for 12 months. The drug produced significant improvement in dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dyschezia, and cyclic rectal bleeding.6

In another pilot study, women who had pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were treated with either an aromatase inhibitor (letrozole, 2.5 mg/d) plus NEA (2.5 mg/d) or NEA (2.5 mg/d) alone for 6 months. Both treatments resulted in a significant improvement in pelvic pain and deep dyspareunia. Improvement in pain scores was greater with letrozole plus NEA; patients were more satisfied with NEA monotherapy than with the combined letrozole-NEA treatment, however, because the former was associated with fewer side effects.7

In a large (n=194) observational study of the postoperative use of NEA in young women with pelvic pain and endometriosis, NEA at dosages as high as 15 mg/d significantly diminished pelvic pain and self-reported menstrual bleeding. All subjects were started on a dosage of 5 mg/d, which was increased in 2.5-mg increments every 2 weeks to achieve the goals of amenorrhea and a lessening of pelvic pain; the maximum dosage administered was 15 mg/d. Mean duration of NEA use was 13 months; 75% of subjects took the maximum prescribed dosage of 15 mg at some point during treatment. The most commonly reported side effects were weight gain (16% of women); acne (10%); mood lability (9%); and vasomotor symptoms (8%).8

In summary. NEA is effective for treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis at dosages from 2.5 mg/d to 15 mg/d. An important goal of treatment is a decrease in pain symptoms and amenorrhea; a dosage of 2.5 mg is often insufficient to reliably achieve both of those objectives.

In my practice I begin therapy at a dosage of 5 mg/d; the drug is effective for most patients at that dosage. If 5 mg/d does not reduce pain, I increase the dosage by 2.5 mg (half of a tablet) daily every 4 weeks, to a maximum dosage of 10 mg/d (two tablets). If that dosage is ineffective, I usually discontinue NEA and switch to a GnRH agonist.

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; oral medroxy-progesterone acetate

DMPA is available in two FDA-approved formulations:

- a 150-mg dose given by intramuscular injection every 3 months

- a 104-mg dose given by subcutaneous injection every 3 months.

Research. The results of two large clinical trials, comprising a total of more than 550 subjects, showed that DMPA (104 mg, SC, every 3 months) and depot leuprolide (11.25 mg, IM, every 3 months or 3.75 mg, monthly) were each equally effective in relieving dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, pelvic tenderness, and pelvic induration in women who had endometriosis.9,10

DMPA was associated with a greater rate of episodes of irregular bleeding than depot leuprolide; conversely, depot leuprolide was associated with greater loss of bone density and a higher incidence of vasomotor symptoms. Weight gain was in the range of 0.6 kg in both groups.

Of note, DPMA is much less expensive than depot leuprolide.

Another study showed that increasing the dosage of DMPA did not improve efficacy over the standard dosage11: DMPA, 150 mg IM, monthly, and DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months produced similar relief of pelvic pain.

Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate, prescribed at high dosages, is also effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In a pilot study (n=21), oral MPA, 50 mg/d for 4 months, alleviated dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, dyschezia, and pelvic tenderness and decreased pelvic nodularity. Sixty percent of subjects reported weight gain— 1.5 kg, on average.12

Progestin-releasing devices: Mirena and Implanon

Many pilot studies have reported that the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.13-17 For example:

Research. In a small clinical trial, 30 women who had pelvic pain and endometriosis were randomized to receive an LNG-IUS (Mirena) or DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months for 3 years.13 Both therapies were effective at reducing pelvic pain.

At the conclusion of the study, more women opted to retain the LNG-IUS (87%) than to continue DMPA injection (47%). Bone density was maintained in women who had the LNG-IUS placed but slightly diminished in women receiving DMPA.

In a pilot study of an etonogestrel releasing implant (Implanon), 41 women who had pelvic pain and endometriosis were randomized to receive the implant or DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months for 1 year.18 Both therapies were similarly effective at reducing pelvic pain.

Notably, irregular uterine bleeding is a common problem when the etonogestrel-releasing implant is used to treat endometriosis. Achieving amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is an important goal for women who suffer from pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

My recommendation

Most ObGyns see patients who are suffering from difficult-to-treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Many of these patients have not had a trial of a progestin, such as NEA, DMPA, or the LNG-IUS that I use in my practice.

Progestins are, as I’ve described, effective for pelvic pain. They are also relatively inexpensive and have a side-effect profile that most patients find acceptable. I recommend that you try a progestin for your patients who have refractory pelvic pain.

What is your preferred hormone treatment for women with unrelieved pelvic pain from endometriosis?

The date of the changeover to the 10th revision of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM) codes is incorrectly stated in the November 2011 Reimbursement Adviser, page 51. The date should be October 1, 2013.

To read the corrected version of this article, Click here

—The Editors

CASE

Your patient is a 26-year-old G0 woman who has a long history of progressively worsening dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. In the recent past, she was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, a cyclic estrogen-progestin contraceptive, and a continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive—in that order, and without appreciable relief of the pain.

Recently, the woman underwent laparoscopy, which demonstrated Stage-II endometriosis, which was ablated.

What would you prescribe for her postoperatively to alleviate symptoms?

Endometriosis will be diagnosed in approximately 8% of women of reproductive age.1 Pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and deep dyspareunia are common symptoms of endometriosis that interfere with quality of life.

Endometriosis is a chronic disease best managed by developing a life-long treatment plan. Following laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment, many experts strongly recommend postoperative hormone-suppressive therapy to reduce the risk that severe pelvic pain will recur, requiring re-operation.

Options for postoperative hormonal treatment of endometriosis include:

- an estrogen–progestin contraceptive

- a progestin (norethindrone acetate [NEA]; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA]; oral medroxyprogesterone acetate; the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system [LNG-IUS; Mirena]; and the progestin-releasing implant [Implanon])

- a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (depot leuprolide [Depot Lupron]; nafarelin nasal spray [Synarel]).

CASE Continued

Considering that both cyclic and continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives have already failed to provide adequate pain relief for your patient, you know that you should offer an alternative to her. Taking into account that progestins are significantly less costly than a GnRH agonist, a progestin formulation might, for her, be considered a first-line postoperative treatment of symptoms of endometriosis.

Options when considering a progestin

Norethindrone acetate

This agent is available in a single formulation: a 5-mg tablet; however, dosages ranging from 2.5 mg/d (half of a tablet) to 15 mg/d have been reported to be effective for relieving pain caused by endometriosis.

What is it? NEA is an androgenic progestin that suppresses luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, thus reducing production of ovarian estrogen. In the absence of ovarian estrogen, endometriosis lesions atrophy. In addition, NEA binds to, and stimulates, endometrial progestin and androgen receptors, resulting in decidualization and atrophy of both eutopic and ectopic endometrial tissue.

Importantly, NEA does not appear to cause bone loss, a phenomenon that is common with agents such as the GnRH agonists or DPMA.2-4

The research record. One randomized study, two pilot studies, and one large observational study have reported that NEA is effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

In the randomized trial, 90 women who had moderate or severe pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis, and who remained symptomatic after conservative surgery, were randomized to receive NEA, 2.5 mg/d, or a low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol, 10 μg, plus cyproterone acetate, 3 mg) daily for 12 months.5 Both treatment groups reported significant and similar decreases in dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, non-menstrual pain and dyschezia.

In a small pilot study, 40 women who had pelvic pain and colorectal endometriosis were treated with NEA 2.5 mg/d for 12 months. The drug produced significant improvement in dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dyschezia, and cyclic rectal bleeding.6

In another pilot study, women who had pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were treated with either an aromatase inhibitor (letrozole, 2.5 mg/d) plus NEA (2.5 mg/d) or NEA (2.5 mg/d) alone for 6 months. Both treatments resulted in a significant improvement in pelvic pain and deep dyspareunia. Improvement in pain scores was greater with letrozole plus NEA; patients were more satisfied with NEA monotherapy than with the combined letrozole-NEA treatment, however, because the former was associated with fewer side effects.7

In a large (n=194) observational study of the postoperative use of NEA in young women with pelvic pain and endometriosis, NEA at dosages as high as 15 mg/d significantly diminished pelvic pain and self-reported menstrual bleeding. All subjects were started on a dosage of 5 mg/d, which was increased in 2.5-mg increments every 2 weeks to achieve the goals of amenorrhea and a lessening of pelvic pain; the maximum dosage administered was 15 mg/d. Mean duration of NEA use was 13 months; 75% of subjects took the maximum prescribed dosage of 15 mg at some point during treatment. The most commonly reported side effects were weight gain (16% of women); acne (10%); mood lability (9%); and vasomotor symptoms (8%).8

In summary. NEA is effective for treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis at dosages from 2.5 mg/d to 15 mg/d. An important goal of treatment is a decrease in pain symptoms and amenorrhea; a dosage of 2.5 mg is often insufficient to reliably achieve both of those objectives.

In my practice I begin therapy at a dosage of 5 mg/d; the drug is effective for most patients at that dosage. If 5 mg/d does not reduce pain, I increase the dosage by 2.5 mg (half of a tablet) daily every 4 weeks, to a maximum dosage of 10 mg/d (two tablets). If that dosage is ineffective, I usually discontinue NEA and switch to a GnRH agonist.

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; oral medroxy-progesterone acetate

DMPA is available in two FDA-approved formulations:

- a 150-mg dose given by intramuscular injection every 3 months

- a 104-mg dose given by subcutaneous injection every 3 months.

Research. The results of two large clinical trials, comprising a total of more than 550 subjects, showed that DMPA (104 mg, SC, every 3 months) and depot leuprolide (11.25 mg, IM, every 3 months or 3.75 mg, monthly) were each equally effective in relieving dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, pelvic tenderness, and pelvic induration in women who had endometriosis.9,10

DMPA was associated with a greater rate of episodes of irregular bleeding than depot leuprolide; conversely, depot leuprolide was associated with greater loss of bone density and a higher incidence of vasomotor symptoms. Weight gain was in the range of 0.6 kg in both groups.

Of note, DPMA is much less expensive than depot leuprolide.

Another study showed that increasing the dosage of DMPA did not improve efficacy over the standard dosage11: DMPA, 150 mg IM, monthly, and DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months produced similar relief of pelvic pain.

Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate, prescribed at high dosages, is also effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In a pilot study (n=21), oral MPA, 50 mg/d for 4 months, alleviated dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, dyschezia, and pelvic tenderness and decreased pelvic nodularity. Sixty percent of subjects reported weight gain— 1.5 kg, on average.12

Progestin-releasing devices: Mirena and Implanon

Many pilot studies have reported that the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is effective for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.13-17 For example:

Research. In a small clinical trial, 30 women who had pelvic pain and endometriosis were randomized to receive an LNG-IUS (Mirena) or DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months for 3 years.13 Both therapies were effective at reducing pelvic pain.

At the conclusion of the study, more women opted to retain the LNG-IUS (87%) than to continue DMPA injection (47%). Bone density was maintained in women who had the LNG-IUS placed but slightly diminished in women receiving DMPA.

In a pilot study of an etonogestrel releasing implant (Implanon), 41 women who had pelvic pain and endometriosis were randomized to receive the implant or DMPA, 150 mg IM, every 3 months for 1 year.18 Both therapies were similarly effective at reducing pelvic pain.

Notably, irregular uterine bleeding is a common problem when the etonogestrel-releasing implant is used to treat endometriosis. Achieving amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is an important goal for women who suffer from pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

My recommendation

Most ObGyns see patients who are suffering from difficult-to-treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Many of these patients have not had a trial of a progestin, such as NEA, DMPA, or the LNG-IUS that I use in my practice.

Progestins are, as I’ve described, effective for pelvic pain. They are also relatively inexpensive and have a side-effect profile that most patients find acceptable. I recommend that you try a progestin for your patients who have refractory pelvic pain.

What is your preferred hormone treatment for women with unrelieved pelvic pain from endometriosis?

1. Missmer SA, Hankinson S, Spiegelman D, et al. The incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropomorphic and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784-796.

2. Abdalla HI, Hart DM, Lindsay R, Leggate I, Hooke A. Prevention of bone mineral loss in postmenopausal women by norethisterone. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(6):789-792.

3. Riss BJ, Lehmann HJ, Christiansen C. Norethisterone acetate in combination with estrogen: effects on the skeleton and other organs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):1101-1116.

4. Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(1):16-24.

5. Vercellini P, Pietropauolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

6. Ferrero S, Camerini G, Ragni N, Venturini PL, Biscaldi E, Remorgida V. Norethisterone acetate in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):94-100.

7. Ferrero S, Camerini G, Seracchioli R, Ragni N, Venturini PL, Remorgida V. Letrozole combined with norethisterone acetate compared with norethisterone acetate alone in the treatment of pain symptoms caused by endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3033-3341.

8. Kaser DJ, Missmer SA, Berry KF, Laufer MR. Use of norethindrone acetate alone for postoperative suppression of endometriosis symptoms [published online ahead of print December 9 2011]. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.013.

9. Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314-325.

10. Crosignani PG, Luciano A, Ray A, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):248-256.

11. Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Choksuchat C, Dhanaworavibul K, Choobun T, Bunyapipat S. Interval of injections of intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in the long-term treatment of endometriosis-associated pain: a randomized clinical trial. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68(2):116-121.

12. Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 Pt 1):323-327.

13. Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273-279.

14. Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy side-effects and continuation rates in women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intrauterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel): a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(3):789-793.

15. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993-1998.

16. Vercellini P, Aimi G, Panazza S, De Giorgi O, Pesole A, Crosignani PG. A levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(3):505-508.

17. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(2):305-309.

18. Walch K, Unfried G, Huber J, Kurz C, van Trotsenburg M, Pernicka E, Wenzl R. Implanon versus medroxyprogesterone acetate: effects on pain scores in patients with symptomatic endometriosis—a pilot study. Contraception. 2009;79(1):29-34.

1. Missmer SA, Hankinson S, Spiegelman D, et al. The incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropomorphic and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784-796.

2. Abdalla HI, Hart DM, Lindsay R, Leggate I, Hooke A. Prevention of bone mineral loss in postmenopausal women by norethisterone. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66(6):789-792.

3. Riss BJ, Lehmann HJ, Christiansen C. Norethisterone acetate in combination with estrogen: effects on the skeleton and other organs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):1101-1116.

4. Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(1):16-24.

5. Vercellini P, Pietropauolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

6. Ferrero S, Camerini G, Ragni N, Venturini PL, Biscaldi E, Remorgida V. Norethisterone acetate in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):94-100.

7. Ferrero S, Camerini G, Seracchioli R, Ragni N, Venturini PL, Remorgida V. Letrozole combined with norethisterone acetate compared with norethisterone acetate alone in the treatment of pain symptoms caused by endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3033-3341.

8. Kaser DJ, Missmer SA, Berry KF, Laufer MR. Use of norethindrone acetate alone for postoperative suppression of endometriosis symptoms [published online ahead of print December 9 2011]. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.013.

9. Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314-325.

10. Crosignani PG, Luciano A, Ray A, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):248-256.

11. Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Choksuchat C, Dhanaworavibul K, Choobun T, Bunyapipat S. Interval of injections of intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate in the long-term treatment of endometriosis-associated pain: a randomized clinical trial. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68(2):116-121.

12. Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 Pt 1):323-327.

13. Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273-279.

14. Lockhat FB, Emembolu JO, Konje JC. The efficacy side-effects and continuation rates in women with symptomatic endometriosis undergoing treatment with an intrauterine administered progestogen (levonorgestrel): a 3 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(3):789-793.

15. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993-1998.

16. Vercellini P, Aimi G, Panazza S, De Giorgi O, Pesole A, Crosignani PG. A levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(3):505-508.

17. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(2):305-309.

18. Walch K, Unfried G, Huber J, Kurz C, van Trotsenburg M, Pernicka E, Wenzl R. Implanon versus medroxyprogesterone acetate: effects on pain scores in patients with symptomatic endometriosis—a pilot study. Contraception. 2009;79(1):29-34.

UPDATE ON PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION

Vulvar Pain Syndromes 3-Part Series

- Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - A bounty of treatments-but not all of them are proven

(October 2011) - Provoked vestibulodynia

(Coming in November 2011)

Chronic pelvic pain: 11 critical questions about causes and care

Fred M. Howard, MD (August 2009)

Vague symptoms. Unexpected flares. Inconsistent manifestations. These characteristics can make diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain frustrating for both patient and physician. Most patients undergo myriad tests and studies to uncover the source of their pain—but a targeted pelvic exam may be all that is necessary to identify a prevalent but commonly overlooked cause of pelvic pain. Levator myalgia, myofascial pelvic pain syndrome, and pelvic floor spasm are all terms that describe a condition that may affect as many as 78% of women who are given a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain.1 This syndrome may be represented by an array of symptoms, including pelvic pressure, dyspareunia, rectal discomfort, and irritative urinary symptoms such as spasms, frequency, and urgency. It is characterized by the presence of tight, band-like pelvic muscles that reproduce the patient’s pain when palpated.2

Diagnosis of this syndrome often surprises the patient. Although the concept of a muscle spasm is not foreign, the location is unexpected. Patients and physicians alike may forget that there is a large complex of muscles that completely lines the pelvic girdle. To complicate matters, the patient often associates the onset of her symptoms with an acute event such as a “bad” urinary tract infection or pelvic or vaginal surgery, which may divert attention from the musculature. Although a muscle spasm may be the cause of the patient’s pain, it’s important to realize that an underlying process may have triggered the original spasm. To provide effective treatment of pain, therefore, you must identify the fundamental cause, assuming that it is reversible, rather than focus exclusively on symptoms.

Although there are many therapeutic options for levator myalgia, an appraisal of the extensive literature on these medications is beyond the scope of this article. Rather, we will review alternative treatment modalities and summarize the results of five trials that explored physical therapy, trigger-point or chemodenervation injection, and neuromodulation (TABLE).

Weighing the nonpharmaceutical options for treatment

of myofascial pelvic pain

| Treatment | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Physical therapy | Minimally invasive Moderate long-term success | Requires highly specialized therapist |

| Trigger-point injection | Minimally invasive Performed in clinic Immediate short-term success | Optimal injectable agent is unknown Botulinum toxin A lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on adverse events and long-term efficacy |

| Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation | Minimally invasive Performed in clinic | Requires numerous office visits for treatment Lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on long-term efficacy |

| Sacral neuromodulation | Moderately invasive Permanent implant | Requires implantation in operating room Lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on long-term efficacy |

Pelvic myofascial therapy offers relief—but qualified therapists may be scarce

FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al; Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J Urology. 2009;182(2):570–580.

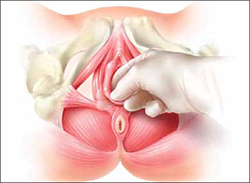

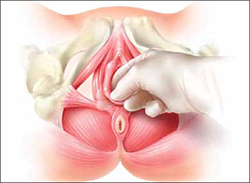

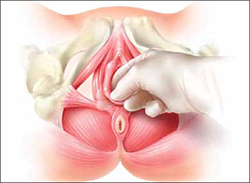

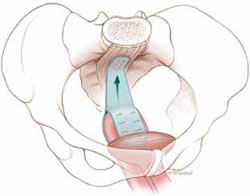

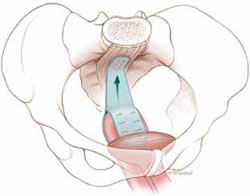

Physical therapy of the pelvic floor—otherwise known as pelvic myofascial therapy—requires a therapist who is highly trained and specialized in this technique. It is more invasive than other forms of rehabilitative therapy because of the need to perform transvaginal maneuvers (FIGURE 1).

This pilot study by the Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network evaluated the ability of patients to adhere to pelvic myofascial therapy, the response of their pain to therapy, and adverse events associated with manual therapy. It found that patients were willing to undergo the therapy, despite the invasive nature of the maneuvers, because it was significantly effective.

Details of the study

Patients (both men and women) were randomized to myofascial physical therapy or global therapeutic massage. Myofascial therapy consisted of internal or vaginal manipulation of the trigger-point muscle bundles and tissues of the pelvic floor. It also focused on muscles of the hip girdle and abdomen. The comparison group underwent traditional Western full-body massage. In both groups, treatment lasted 1 hour every week, and participants agreed to 10 full treatments.

Patients were eligible for the study if they experienced pelvic pain, urinary frequency, or bladder discomfort in the previous 6 months. In addition, an examiner must have been able to elicit tenderness upon palpation of the pelvic floor during examination. Patients were excluded if they showed signs of urinary tract infection or dysmenorrhea.

A total of 47 patients were randomized—24 to global massage and 23 to myofascial physical therapy. Overall, the myofascial group experienced a significantly higher rate of improvement in the global response at 12 weeks than did patients in the global-massage group (57% vs 21%; P=.03). Patients were willing to engage in myofascial pelvic therapy, and adverse events were minor.

FIGURE 1 Transvaginal myofascial therapy

Physical therapy of the pelvic floor is more invasive than other forms of rehabilitative therapy because of the need to perform transvaginal maneuvers.

Need for specialized training may limit number of therapists

The randomized controlled study design renders these findings fairly reliable. Therapists were unmasked and aware of the treatment arms but were trained to make the different therapy sessions appear as similar as possible.

Although investigators were enthusiastic about their initial findings, additional studies are needed to validate the results. Moreover, these findings may be difficult to generalize because women who volunteer to participate in such a study may differ from the general population.

Nevertheless, patients who suffer from chronic pelvic pain may take heart that there is a nonpharmaceutical alternative to manage their symptoms, although availability is likely limited in many areas. Given the nature of the physical therapy required for this particular location of myofascial pain, specialized training is necessary for therapists. Despite motivated patients and well-informed providers, it may be difficult to find specialized therapists within local vicinities. Referrals to centers where this type of therapy is offered may be necessary.

Pelvic myofascial therapy is an effective and acceptable intervention for the treatment of levator myalgia.

The ideal agent for trigger-point injections remains a mystery

Langford CF, Udvari Nagy S, Ghoniem G M. Levator ani trigger point injections: An underutilized treatment for chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26(1):59–62.

Abbott JA, Jarvis SK, Lyons SD, Thomson A, Vancaille TG. Botulinum toxin type A for chronic pain and pelvic floor spasm in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):915–923.

Trigger points are discrete, tender areas within a ridge of contracted muscle. These points may cause focal pain or referred pain upon irritation of the muscle.2 Trigger-point injection therapy aims to anesthetize or relax these points by infiltrating the muscle with medications.

These two studies evaluated the value of trigger-point injections in the treatment of pelvic myofascial pain; they found that the injections provide relief, although the mechanism of action and the ideal agent remain to be determined.

Langford et al: Details of the study

In this prospective study, 18 women who had pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration and confirmed trigger points on examination underwent transvaginal injection of a solution of bupivacaine, lidocaine, and triamcinolone. They were assessed by questionnaire at baseline and 3 months after injection. Assessment included a visual analog scale for pain severity. Investigators defined success as a decrease in pain of 50% or more and global-satisfaction and global-cure visual scores of 60% or higher.

Thirteen of the 18 women (72.2%) improved after their first injection, with six women reporting a complete absence of pain. Overall, women reported significant decreases in pain and increases in the rates of satisfaction and cure, meeting the definition of success at 3 months after the injection.

Among the theories proposed to explain the mechanism of action of trigger-point injections are:

- disruption of reflex arcs within skeletal muscle

- release of endorphins

- mechanical changes in abnormally contracted muscle fibers.

This last theory highlights one of the limitations of this study—lack of a placebo arm. Could it be possible that the injection of any fluid produces the same effect?

This study was not designed to investigate the causal relationship between the injection of a particular solution and pain relief, but it does highlight the need for studies to clarify the mechanism of action, including use of a placebo. It also prompts questions about the duration of effect after a single injection.

Goal of chemodenervation is blocking of muscle activity

Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) blocks the release of acetylcholine from presynaptic neurons. The release of acetylcholine stimulates muscle contractions; therefore, blockage of its release reduces muscle activity. This type of chemodenervation has found widespread use, and botulinum toxin A now has approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of chronic migraine, limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, strabismus, hyperhidrosis, and facial cosmesis.3 Although it is not approved for pelvic floor levator spasm, its success in treating other myotonic disorders suggests that its application may be relevant.

Abbott et al: Details of the study

Abbott and colleagues performed a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to compare injection of botulinum toxin A with injection of saline. They measured changes in the pain scale, quality of life, and vaginal pressure.

Women were eligible for the study if they had subjectively reported pelvic pain of more than 2 years’ duration and objective evidence of trigger points (on examination) and elevated vaginal resting pressure (by vaginal manometry). Neither the clinical research staff nor the patient knew the contents of the injections, but all women received a total of four—two at sites in the puborectalis muscle and two in the pubococcygeus muscle.

After periodic assessment by questionnaire and examination through 6 months after injection, no differences were found in the pain score or resting vaginal pressure between the group of women who received botulinum toxin A and the group who received placebo. However, each group experienced a significant reduction in pain and vaginal pressure, compared with baseline. And both groups reported improved quality of life, compared with baseline. Neither group reported voiding dysfunction.

These two studies support the use of trigger-point injection into pelvic floor muscles to reduce pelvic myofascial pain. The findings of Abbott and colleagues, in particular, suggest that the substance that is injected may not be as important as the actual needling of the muscle. Larger studies and comparisons between placebo, botulinum toxin A, and anesthetic solutions are needed to elucidate the therapeutic benefit of these particular medications.

Neuromodulation shows promise as treatment for pelvic myofascial pain

van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink, BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43(2):158–163.

Zabihi N, Mourtzinos A, Maher MG, Raz S, Rodriguez LV. Short-term results of bilateral S2-S4 sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of refractory interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome, and chronic pelvic pain. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(4):553–557.

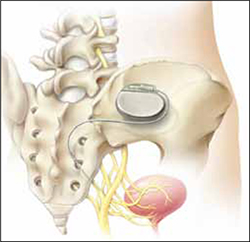

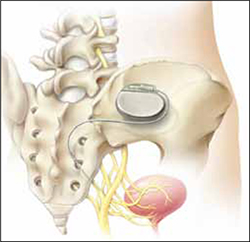

Neuromodulation is the science of using electrical impulses to alter neuronal activities. The exact mechanisms of action are unclear, but the technology has been utilized to control symptoms of overactive bladder and urinary retention caused by poor relaxation of the urethral and pelvic floor muscles. While studying the effects of sacral nerve root neuromodulation on the bladder, investigators noted improvements in other symptoms, such as pelvic pain.

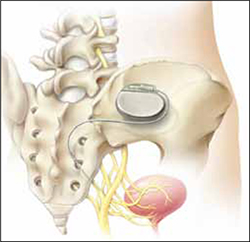

Neuromodulation of the sacral nerve roots may be achieved by direct conduction of electrical impulses from a lead implanted in the sacrum (sacral neuromodulation) or by the retrograde conduction of these impulses through the posterior tibial nerve (percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, or PTNS) (FIGURE 2). The tibial nerve arises from sacral nerves L5 to S3 and is one of the larger branches of the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 2 InterStim therapy

Stimulation of the sacral nerve has been used successfully to manage overactive bladder and urinary retention and may prove useful in the treatment of pelvic myofascial pain.

Van Balken et al: Details of the study

In this prospective observational study, 33 patients (both male and female) who had chronic pelvic pain by history and examination were treated with weekly, 30-minute outpatient sessions of PTNS for 12 weeks. Participants were asked to provide baseline pain scores and keep a diary of their pain. Quality-of-life questionnaires were also administered at baseline and at 12 weeks.

Investigators considered both subjective and objective success in their outcomes. If a patient elected to continue therapy, he or she was classified as a subjective success. Objective success required a decrease of at least 50% in the pain score. At the end of 12 weeks, although 33 patients (42%) wanted to continue therapy, only seven (21%) met the definition for objective success. Of those seven, six elected to continue therapy.

This study sheds light on a treatment modality that has not been studied adequately for the indication of pelvic pain but that may be promising in patients who have levator myalgia. Limitations of this study include the lack of a placebo arm, short-term outcome, and lack of localization of pain. Furthermore, although PTNS has FDA approval for treatment of urinary urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, it is not approved for the treatment of pelvic pain. These preliminary findings demonstrate potential but, as with any new indication, long-term comparative studies are needed.

Zabihi et al: Details of the study

Patients in this retrospective study had a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis or chronic pelvic pain. Pelvic myofascial pain and trigger points were not required for eligibility. Thirty patients (21 women and nine men) had temporary placement of a lead containing four small electrodes along the S2 to S4 sacral nerve roots on both sides of the sacrum. They were then followed for a trial period of 2 to 4 weeks. To qualify for the final stage of the study, in which the leads were connected internally to a generator implanted in the buttocks, patients had to report improvement of at least 50% in their symptoms. If their improvement did not meet that threshold, the leads were removed.

Twenty-three patients (77%) met the criteria for permanent implantation. Of these patients, 42% reported improvement of more than 50% at 6 postoperative months. Quality-of-life scores also improved significantly.

Sacral neuromodulation is not FDA-approved for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain; further studies are needed before it can be recommended for this indication.

Neither of these studies required objective evidence of myofascial pain for inclusion. Therefore, although the benefits they demonstrated may be theorized to extend to the relief of myofascial pain, this fact cannot be corroborated.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Bassaly R, Tidwell N, Bertolino S, Hoyte L, Downes K, Hart S. Myofascial pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in patients with interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(4):413-418.

2. Alvarez DJ, Rockwell PG. Trigger points: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(4):653-660.

3. Allergan, Inc. Medication Guide: BOTOX. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM176360.pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed August 30, 2011.

Vulvar Pain Syndromes 3-Part Series

- Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - A bounty of treatments-but not all of them are proven

(October 2011) - Provoked vestibulodynia

(Coming in November 2011)

Chronic pelvic pain: 11 critical questions about causes and care

Fred M. Howard, MD (August 2009)

Vague symptoms. Unexpected flares. Inconsistent manifestations. These characteristics can make diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain frustrating for both patient and physician. Most patients undergo myriad tests and studies to uncover the source of their pain—but a targeted pelvic exam may be all that is necessary to identify a prevalent but commonly overlooked cause of pelvic pain. Levator myalgia, myofascial pelvic pain syndrome, and pelvic floor spasm are all terms that describe a condition that may affect as many as 78% of women who are given a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain.1 This syndrome may be represented by an array of symptoms, including pelvic pressure, dyspareunia, rectal discomfort, and irritative urinary symptoms such as spasms, frequency, and urgency. It is characterized by the presence of tight, band-like pelvic muscles that reproduce the patient’s pain when palpated.2

Diagnosis of this syndrome often surprises the patient. Although the concept of a muscle spasm is not foreign, the location is unexpected. Patients and physicians alike may forget that there is a large complex of muscles that completely lines the pelvic girdle. To complicate matters, the patient often associates the onset of her symptoms with an acute event such as a “bad” urinary tract infection or pelvic or vaginal surgery, which may divert attention from the musculature. Although a muscle spasm may be the cause of the patient’s pain, it’s important to realize that an underlying process may have triggered the original spasm. To provide effective treatment of pain, therefore, you must identify the fundamental cause, assuming that it is reversible, rather than focus exclusively on symptoms.

Although there are many therapeutic options for levator myalgia, an appraisal of the extensive literature on these medications is beyond the scope of this article. Rather, we will review alternative treatment modalities and summarize the results of five trials that explored physical therapy, trigger-point or chemodenervation injection, and neuromodulation (TABLE).

Weighing the nonpharmaceutical options for treatment

of myofascial pelvic pain

| Treatment | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Physical therapy | Minimally invasive Moderate long-term success | Requires highly specialized therapist |

| Trigger-point injection | Minimally invasive Performed in clinic Immediate short-term success | Optimal injectable agent is unknown Botulinum toxin A lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on adverse events and long-term efficacy |

| Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation | Minimally invasive Performed in clinic | Requires numerous office visits for treatment Lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on long-term efficacy |

| Sacral neuromodulation | Moderately invasive Permanent implant | Requires implantation in operating room Lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on long-term efficacy |

Pelvic myofascial therapy offers relief—but qualified therapists may be scarce

FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al; Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J Urology. 2009;182(2):570–580.

Physical therapy of the pelvic floor—otherwise known as pelvic myofascial therapy—requires a therapist who is highly trained and specialized in this technique. It is more invasive than other forms of rehabilitative therapy because of the need to perform transvaginal maneuvers (FIGURE 1).

This pilot study by the Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network evaluated the ability of patients to adhere to pelvic myofascial therapy, the response of their pain to therapy, and adverse events associated with manual therapy. It found that patients were willing to undergo the therapy, despite the invasive nature of the maneuvers, because it was significantly effective.

Details of the study

Patients (both men and women) were randomized to myofascial physical therapy or global therapeutic massage. Myofascial therapy consisted of internal or vaginal manipulation of the trigger-point muscle bundles and tissues of the pelvic floor. It also focused on muscles of the hip girdle and abdomen. The comparison group underwent traditional Western full-body massage. In both groups, treatment lasted 1 hour every week, and participants agreed to 10 full treatments.

Patients were eligible for the study if they experienced pelvic pain, urinary frequency, or bladder discomfort in the previous 6 months. In addition, an examiner must have been able to elicit tenderness upon palpation of the pelvic floor during examination. Patients were excluded if they showed signs of urinary tract infection or dysmenorrhea.

A total of 47 patients were randomized—24 to global massage and 23 to myofascial physical therapy. Overall, the myofascial group experienced a significantly higher rate of improvement in the global response at 12 weeks than did patients in the global-massage group (57% vs 21%; P=.03). Patients were willing to engage in myofascial pelvic therapy, and adverse events were minor.

FIGURE 1 Transvaginal myofascial therapy

Physical therapy of the pelvic floor is more invasive than other forms of rehabilitative therapy because of the need to perform transvaginal maneuvers.

Need for specialized training may limit number of therapists

The randomized controlled study design renders these findings fairly reliable. Therapists were unmasked and aware of the treatment arms but were trained to make the different therapy sessions appear as similar as possible.

Although investigators were enthusiastic about their initial findings, additional studies are needed to validate the results. Moreover, these findings may be difficult to generalize because women who volunteer to participate in such a study may differ from the general population.

Nevertheless, patients who suffer from chronic pelvic pain may take heart that there is a nonpharmaceutical alternative to manage their symptoms, although availability is likely limited in many areas. Given the nature of the physical therapy required for this particular location of myofascial pain, specialized training is necessary for therapists. Despite motivated patients and well-informed providers, it may be difficult to find specialized therapists within local vicinities. Referrals to centers where this type of therapy is offered may be necessary.

Pelvic myofascial therapy is an effective and acceptable intervention for the treatment of levator myalgia.

The ideal agent for trigger-point injections remains a mystery

Langford CF, Udvari Nagy S, Ghoniem G M. Levator ani trigger point injections: An underutilized treatment for chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26(1):59–62.

Abbott JA, Jarvis SK, Lyons SD, Thomson A, Vancaille TG. Botulinum toxin type A for chronic pain and pelvic floor spasm in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):915–923.

Trigger points are discrete, tender areas within a ridge of contracted muscle. These points may cause focal pain or referred pain upon irritation of the muscle.2 Trigger-point injection therapy aims to anesthetize or relax these points by infiltrating the muscle with medications.

These two studies evaluated the value of trigger-point injections in the treatment of pelvic myofascial pain; they found that the injections provide relief, although the mechanism of action and the ideal agent remain to be determined.

Langford et al: Details of the study

In this prospective study, 18 women who had pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration and confirmed trigger points on examination underwent transvaginal injection of a solution of bupivacaine, lidocaine, and triamcinolone. They were assessed by questionnaire at baseline and 3 months after injection. Assessment included a visual analog scale for pain severity. Investigators defined success as a decrease in pain of 50% or more and global-satisfaction and global-cure visual scores of 60% or higher.

Thirteen of the 18 women (72.2%) improved after their first injection, with six women reporting a complete absence of pain. Overall, women reported significant decreases in pain and increases in the rates of satisfaction and cure, meeting the definition of success at 3 months after the injection.

Among the theories proposed to explain the mechanism of action of trigger-point injections are:

- disruption of reflex arcs within skeletal muscle

- release of endorphins

- mechanical changes in abnormally contracted muscle fibers.

This last theory highlights one of the limitations of this study—lack of a placebo arm. Could it be possible that the injection of any fluid produces the same effect?

This study was not designed to investigate the causal relationship between the injection of a particular solution and pain relief, but it does highlight the need for studies to clarify the mechanism of action, including use of a placebo. It also prompts questions about the duration of effect after a single injection.

Goal of chemodenervation is blocking of muscle activity

Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) blocks the release of acetylcholine from presynaptic neurons. The release of acetylcholine stimulates muscle contractions; therefore, blockage of its release reduces muscle activity. This type of chemodenervation has found widespread use, and botulinum toxin A now has approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of chronic migraine, limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, strabismus, hyperhidrosis, and facial cosmesis.3 Although it is not approved for pelvic floor levator spasm, its success in treating other myotonic disorders suggests that its application may be relevant.

Abbott et al: Details of the study

Abbott and colleagues performed a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to compare injection of botulinum toxin A with injection of saline. They measured changes in the pain scale, quality of life, and vaginal pressure.

Women were eligible for the study if they had subjectively reported pelvic pain of more than 2 years’ duration and objective evidence of trigger points (on examination) and elevated vaginal resting pressure (by vaginal manometry). Neither the clinical research staff nor the patient knew the contents of the injections, but all women received a total of four—two at sites in the puborectalis muscle and two in the pubococcygeus muscle.

After periodic assessment by questionnaire and examination through 6 months after injection, no differences were found in the pain score or resting vaginal pressure between the group of women who received botulinum toxin A and the group who received placebo. However, each group experienced a significant reduction in pain and vaginal pressure, compared with baseline. And both groups reported improved quality of life, compared with baseline. Neither group reported voiding dysfunction.

These two studies support the use of trigger-point injection into pelvic floor muscles to reduce pelvic myofascial pain. The findings of Abbott and colleagues, in particular, suggest that the substance that is injected may not be as important as the actual needling of the muscle. Larger studies and comparisons between placebo, botulinum toxin A, and anesthetic solutions are needed to elucidate the therapeutic benefit of these particular medications.

Neuromodulation shows promise as treatment for pelvic myofascial pain

van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink, BJ, et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2003;43(2):158–163.

Zabihi N, Mourtzinos A, Maher MG, Raz S, Rodriguez LV. Short-term results of bilateral S2-S4 sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of refractory interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome, and chronic pelvic pain. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(4):553–557.

Neuromodulation is the science of using electrical impulses to alter neuronal activities. The exact mechanisms of action are unclear, but the technology has been utilized to control symptoms of overactive bladder and urinary retention caused by poor relaxation of the urethral and pelvic floor muscles. While studying the effects of sacral nerve root neuromodulation on the bladder, investigators noted improvements in other symptoms, such as pelvic pain.

Neuromodulation of the sacral nerve roots may be achieved by direct conduction of electrical impulses from a lead implanted in the sacrum (sacral neuromodulation) or by the retrograde conduction of these impulses through the posterior tibial nerve (percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, or PTNS) (FIGURE 2). The tibial nerve arises from sacral nerves L5 to S3 and is one of the larger branches of the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 2 InterStim therapy

Stimulation of the sacral nerve has been used successfully to manage overactive bladder and urinary retention and may prove useful in the treatment of pelvic myofascial pain.

Van Balken et al: Details of the study

In this prospective observational study, 33 patients (both male and female) who had chronic pelvic pain by history and examination were treated with weekly, 30-minute outpatient sessions of PTNS for 12 weeks. Participants were asked to provide baseline pain scores and keep a diary of their pain. Quality-of-life questionnaires were also administered at baseline and at 12 weeks.

Investigators considered both subjective and objective success in their outcomes. If a patient elected to continue therapy, he or she was classified as a subjective success. Objective success required a decrease of at least 50% in the pain score. At the end of 12 weeks, although 33 patients (42%) wanted to continue therapy, only seven (21%) met the definition for objective success. Of those seven, six elected to continue therapy.

This study sheds light on a treatment modality that has not been studied adequately for the indication of pelvic pain but that may be promising in patients who have levator myalgia. Limitations of this study include the lack of a placebo arm, short-term outcome, and lack of localization of pain. Furthermore, although PTNS has FDA approval for treatment of urinary urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, it is not approved for the treatment of pelvic pain. These preliminary findings demonstrate potential but, as with any new indication, long-term comparative studies are needed.

Zabihi et al: Details of the study

Patients in this retrospective study had a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis or chronic pelvic pain. Pelvic myofascial pain and trigger points were not required for eligibility. Thirty patients (21 women and nine men) had temporary placement of a lead containing four small electrodes along the S2 to S4 sacral nerve roots on both sides of the sacrum. They were then followed for a trial period of 2 to 4 weeks. To qualify for the final stage of the study, in which the leads were connected internally to a generator implanted in the buttocks, patients had to report improvement of at least 50% in their symptoms. If their improvement did not meet that threshold, the leads were removed.

Twenty-three patients (77%) met the criteria for permanent implantation. Of these patients, 42% reported improvement of more than 50% at 6 postoperative months. Quality-of-life scores also improved significantly.

Sacral neuromodulation is not FDA-approved for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain; further studies are needed before it can be recommended for this indication.

Neither of these studies required objective evidence of myofascial pain for inclusion. Therefore, although the benefits they demonstrated may be theorized to extend to the relief of myofascial pain, this fact cannot be corroborated.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Vulvar Pain Syndromes 3-Part Series

- Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - A bounty of treatments-but not all of them are proven

(October 2011) - Provoked vestibulodynia

(Coming in November 2011)

Chronic pelvic pain: 11 critical questions about causes and care

Fred M. Howard, MD (August 2009)

Vague symptoms. Unexpected flares. Inconsistent manifestations. These characteristics can make diagnosis and treatment of chronic pelvic pain frustrating for both patient and physician. Most patients undergo myriad tests and studies to uncover the source of their pain—but a targeted pelvic exam may be all that is necessary to identify a prevalent but commonly overlooked cause of pelvic pain. Levator myalgia, myofascial pelvic pain syndrome, and pelvic floor spasm are all terms that describe a condition that may affect as many as 78% of women who are given a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain.1 This syndrome may be represented by an array of symptoms, including pelvic pressure, dyspareunia, rectal discomfort, and irritative urinary symptoms such as spasms, frequency, and urgency. It is characterized by the presence of tight, band-like pelvic muscles that reproduce the patient’s pain when palpated.2

Diagnosis of this syndrome often surprises the patient. Although the concept of a muscle spasm is not foreign, the location is unexpected. Patients and physicians alike may forget that there is a large complex of muscles that completely lines the pelvic girdle. To complicate matters, the patient often associates the onset of her symptoms with an acute event such as a “bad” urinary tract infection or pelvic or vaginal surgery, which may divert attention from the musculature. Although a muscle spasm may be the cause of the patient’s pain, it’s important to realize that an underlying process may have triggered the original spasm. To provide effective treatment of pain, therefore, you must identify the fundamental cause, assuming that it is reversible, rather than focus exclusively on symptoms.

Although there are many therapeutic options for levator myalgia, an appraisal of the extensive literature on these medications is beyond the scope of this article. Rather, we will review alternative treatment modalities and summarize the results of five trials that explored physical therapy, trigger-point or chemodenervation injection, and neuromodulation (TABLE).

Weighing the nonpharmaceutical options for treatment

of myofascial pelvic pain

| Treatment | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Physical therapy | Minimally invasive Moderate long-term success | Requires highly specialized therapist |

| Trigger-point injection | Minimally invasive Performed in clinic Immediate short-term success | Optimal injectable agent is unknown Botulinum toxin A lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on adverse events and long-term efficacy |

| Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation | Minimally invasive Performed in clinic | Requires numerous office visits for treatment Lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on long-term efficacy |

| Sacral neuromodulation | Moderately invasive Permanent implant | Requires implantation in operating room Lacks FDA approval for this indication Limited information on long-term efficacy |

Pelvic myofascial therapy offers relief—but qualified therapists may be scarce

FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al; Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J Urology. 2009;182(2):570–580.

Physical therapy of the pelvic floor—otherwise known as pelvic myofascial therapy—requires a therapist who is highly trained and specialized in this technique. It is more invasive than other forms of rehabilitative therapy because of the need to perform transvaginal maneuvers (FIGURE 1).

This pilot study by the Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network evaluated the ability of patients to adhere to pelvic myofascial therapy, the response of their pain to therapy, and adverse events associated with manual therapy. It found that patients were willing to undergo the therapy, despite the invasive nature of the maneuvers, because it was significantly effective.

Details of the study

Patients (both men and women) were randomized to myofascial physical therapy or global therapeutic massage. Myofascial therapy consisted of internal or vaginal manipulation of the trigger-point muscle bundles and tissues of the pelvic floor. It also focused on muscles of the hip girdle and abdomen. The comparison group underwent traditional Western full-body massage. In both groups, treatment lasted 1 hour every week, and participants agreed to 10 full treatments.