User login

STOP using synthetic mesh for routine repair of pelvic organ prolapse

Have you read these recent articles in OBG Management about the surgical use of mesh? Click here to access the list.

CASE: Stage 2 prolapse to the hymenal ring

A 54-year-old Para 3 woman presents with stage 2 prolapse to the hymenal ring. The prolapse predominantly involves the anterior vagina, with her cervix prolapsing to 2 cm within the hymenal ring. The patient is bothered by the bulge and stress urinary leakage. She does not want to use a pessary and prefers to have definitive surgical correction, including hysterectomy.

The first surgeon she consulted recommended a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, anterior synthetic mesh vaginal colpopexy, and synthetic midurethral sling. The patient was concerned about mesh placement for prolapse and the sling after seeing ads on the Internet about vaginal mesh. She presents for a second opinion about surgical alternatives.

Stop routinely offering synthetic vaginal mesh for prolapse

Advantages to the use of synthetic vaginal mesh include improved subjective and objective cure rates for prolapse (especially for the anterior compartment) and fewer repeat surgeries for recurrent prolapse. However, disadvantages include:

- mesh exposure and extrusion through the vaginal epithelium

- overall higher reoperation for mesh-related complications and de novo stress urinary incontinence.1

Synthetic vaginal mesh should be reserved for special situations. Currently, experts agree that synthetic vaginal mesh is appropriate in cases of recurrent prolapse, advanced-stage prolapse, collagen deficiency, or in cases with relative contraindications to longer endoscopic or abdominal surgery, such as medical comorbidities or adhesions.2,3 Other indications for synthetic vaginal mesh include vaginal hysteropexy procedures.

Mesh is likely not necessary in:

- primary repairs

- prolapse < POPQ (pelvic organ prolapse quantification system) stage 2

- posterior prolapse

- patients with chronic pelvic pain.

Start offering, learning, and mastering native tissue repairs

For the patient in the opening case, who has symptomatic stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, surgery, including a transvaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, uterosacral ligament suspension, and synthetic midurethral sling, is a reasonable alternative and has a high subjective and objective cure rate—81.2% rate for anterior prolapse and 98.3% rate for apical prolapse. Better outcomes are noted with stage 2 compared with stage 3 prolapse (92.4% vs 66.8%, respectively).4

Final note

If you are offering selective transvaginal synthetic mesh for prolapse repairs:

- Undergo training specific to each device.

- Track your outcomes—including objective, subjective, quality of life, and reoperation for complications and recurrence.

- Enroll in the national pelvic floor disorders registry, which is scheduled to debut in Fall 2013.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Schmid C, Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Glazener C. 2012 Cochrane Review: Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(suppl 2).-

2. Davila GW, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate. Consensus of the 2nd IUGA Grafts Roundtable: optimizing safety and appropriateness of graft use in transvaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(suppl 1):S7-S14.

3. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists American Urogynecologic Society. Committee Opinion No. 513: Vaginal placement of synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(6):1459-1464.

4. Margulies RU, Rogers MA, Morgan DM. Outcomes of transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):124-134.

Have you read these recent articles in OBG Management about the surgical use of mesh? Click here to access the list.

CASE: Stage 2 prolapse to the hymenal ring

A 54-year-old Para 3 woman presents with stage 2 prolapse to the hymenal ring. The prolapse predominantly involves the anterior vagina, with her cervix prolapsing to 2 cm within the hymenal ring. The patient is bothered by the bulge and stress urinary leakage. She does not want to use a pessary and prefers to have definitive surgical correction, including hysterectomy.

The first surgeon she consulted recommended a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, anterior synthetic mesh vaginal colpopexy, and synthetic midurethral sling. The patient was concerned about mesh placement for prolapse and the sling after seeing ads on the Internet about vaginal mesh. She presents for a second opinion about surgical alternatives.

Stop routinely offering synthetic vaginal mesh for prolapse

Advantages to the use of synthetic vaginal mesh include improved subjective and objective cure rates for prolapse (especially for the anterior compartment) and fewer repeat surgeries for recurrent prolapse. However, disadvantages include:

- mesh exposure and extrusion through the vaginal epithelium

- overall higher reoperation for mesh-related complications and de novo stress urinary incontinence.1

Synthetic vaginal mesh should be reserved for special situations. Currently, experts agree that synthetic vaginal mesh is appropriate in cases of recurrent prolapse, advanced-stage prolapse, collagen deficiency, or in cases with relative contraindications to longer endoscopic or abdominal surgery, such as medical comorbidities or adhesions.2,3 Other indications for synthetic vaginal mesh include vaginal hysteropexy procedures.

Mesh is likely not necessary in:

- primary repairs

- prolapse < POPQ (pelvic organ prolapse quantification system) stage 2

- posterior prolapse

- patients with chronic pelvic pain.

Start offering, learning, and mastering native tissue repairs

For the patient in the opening case, who has symptomatic stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, surgery, including a transvaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, uterosacral ligament suspension, and synthetic midurethral sling, is a reasonable alternative and has a high subjective and objective cure rate—81.2% rate for anterior prolapse and 98.3% rate for apical prolapse. Better outcomes are noted with stage 2 compared with stage 3 prolapse (92.4% vs 66.8%, respectively).4

Final note

If you are offering selective transvaginal synthetic mesh for prolapse repairs:

- Undergo training specific to each device.

- Track your outcomes—including objective, subjective, quality of life, and reoperation for complications and recurrence.

- Enroll in the national pelvic floor disorders registry, which is scheduled to debut in Fall 2013.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Have you read these recent articles in OBG Management about the surgical use of mesh? Click here to access the list.

CASE: Stage 2 prolapse to the hymenal ring

A 54-year-old Para 3 woman presents with stage 2 prolapse to the hymenal ring. The prolapse predominantly involves the anterior vagina, with her cervix prolapsing to 2 cm within the hymenal ring. The patient is bothered by the bulge and stress urinary leakage. She does not want to use a pessary and prefers to have definitive surgical correction, including hysterectomy.

The first surgeon she consulted recommended a vaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, anterior synthetic mesh vaginal colpopexy, and synthetic midurethral sling. The patient was concerned about mesh placement for prolapse and the sling after seeing ads on the Internet about vaginal mesh. She presents for a second opinion about surgical alternatives.

Stop routinely offering synthetic vaginal mesh for prolapse

Advantages to the use of synthetic vaginal mesh include improved subjective and objective cure rates for prolapse (especially for the anterior compartment) and fewer repeat surgeries for recurrent prolapse. However, disadvantages include:

- mesh exposure and extrusion through the vaginal epithelium

- overall higher reoperation for mesh-related complications and de novo stress urinary incontinence.1

Synthetic vaginal mesh should be reserved for special situations. Currently, experts agree that synthetic vaginal mesh is appropriate in cases of recurrent prolapse, advanced-stage prolapse, collagen deficiency, or in cases with relative contraindications to longer endoscopic or abdominal surgery, such as medical comorbidities or adhesions.2,3 Other indications for synthetic vaginal mesh include vaginal hysteropexy procedures.

Mesh is likely not necessary in:

- primary repairs

- prolapse < POPQ (pelvic organ prolapse quantification system) stage 2

- posterior prolapse

- patients with chronic pelvic pain.

Start offering, learning, and mastering native tissue repairs

For the patient in the opening case, who has symptomatic stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, surgery, including a transvaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy, uterosacral ligament suspension, and synthetic midurethral sling, is a reasonable alternative and has a high subjective and objective cure rate—81.2% rate for anterior prolapse and 98.3% rate for apical prolapse. Better outcomes are noted with stage 2 compared with stage 3 prolapse (92.4% vs 66.8%, respectively).4

Final note

If you are offering selective transvaginal synthetic mesh for prolapse repairs:

- Undergo training specific to each device.

- Track your outcomes—including objective, subjective, quality of life, and reoperation for complications and recurrence.

- Enroll in the national pelvic floor disorders registry, which is scheduled to debut in Fall 2013.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Schmid C, Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Glazener C. 2012 Cochrane Review: Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(suppl 2).-

2. Davila GW, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate. Consensus of the 2nd IUGA Grafts Roundtable: optimizing safety and appropriateness of graft use in transvaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(suppl 1):S7-S14.

3. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists American Urogynecologic Society. Committee Opinion No. 513: Vaginal placement of synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(6):1459-1464.

4. Margulies RU, Rogers MA, Morgan DM. Outcomes of transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):124-134.

1. Schmid C, Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Glazener C. 2012 Cochrane Review: Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(suppl 2).-

2. Davila GW, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate. Consensus of the 2nd IUGA Grafts Roundtable: optimizing safety and appropriateness of graft use in transvaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(suppl 1):S7-S14.

3. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists American Urogynecologic Society. Committee Opinion No. 513: Vaginal placement of synthetic mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(6):1459-1464.

4. Margulies RU, Rogers MA, Morgan DM. Outcomes of transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):124-134.

Native tissue is superior to vaginal mesh for prolapse repair, two studies report

Have you read recent articles in OBG Management about the surgical use of mesh?

Click here to access the list.

- Michele Jonsson Funk, PhD, and colleagues from University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill concluded that using vaginal mesh versus native tissue for anterior prolapse repair is associated with 5-year increased risk of any repeat surgery, especially surgery for mesh removal.1

- Shunaha Kim-Fine, MD, and colleagues from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, believe that traditional native tissue repair is the best procedure for most women undergoing vaginal POP repair.2

UNC study details

Investigators from the Gillings School of Global Public Health at UNC studied health-care claims from 2005 to 2010. They identified women who, after undergoing anterior wall prolapse repair, experienced repeat surgery for recurrent prolapse or mesh removal. Of the initial 27,809 anterior prolapse surgeries, 6,871 (24.7%) included the use of vaginal mesh.1

5-year risk of repeat surgery. The authors determined that1:

- the 5-year cumulative risk of any repeat surgery was significantly higher with the use of vaginal mesh than with the use of native tissue (15.2% vs 9.8%, respectively; P .0001 with a risk of mesh revision or removal>

- the 5-year risk for recurrent prolapse surgery between both groups was comparable (10.4% vs 9.3%, P = .70).

Mayo Clinic study details

Researchers from Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Division of Gynecologic Surgery at Mayo Clinic reviewed the literature and compared vaginal native tissue repair with vaginal mesh–augmented repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Their report was published online ahead of print on January 17, 2013, in Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports.

The authors discuss POP; the procedures available to treat symptomatic POP; the Public Heath Notifications issued in 2008 and 2011 from U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding the use of transvaginal mesh in POP repair; and success, failure, and complication rates from both techniques.2

“Given the lack of robust and long-term data in these relatively new procedures for [mesh-augmentation] repair, we agree with the caution and prudence communication in the recent FDA warning,” state the authors.2 However, a caveat is offered that native tissue repair must utilize best principles of surgical technique and incorporate a multicompartment repair to achieve optimal outcome. The authors strongly advise that appropriate surgical technique, obtained only through adequate surgical training, can be improved for both repair procedures.2

Risks and complications from mesh. Mesh introduces unique risks related to the mesh itself, including mesh erosion, and complications, including new onset pain and dyspareunia following mesh-augmented repair. Complications are possibly related to the intrinsic properties of the mesh, (ie, shrinkage); to the patient (ie, scarring); or to the operative technique (ie, the placement/location of the mesh and increased tension on the mesh). The authors conclude that additional studies are needed, given the lack of robust and long-term data on mesh-augmentation repair of POP.2

“The evidence thus far has not shown that the benefits of mesh outweigh the added risks in vaginal prolapse repairs,” write the authors.2 Therefore, although patient-centered success rates for both techniques of POP repair are equivalent, the authors conclude: “there does not appear to be a clear advantage of mesh augmentation repair over native tissue in terms of anatomic success.”2

To access the Jonsson Funk abstract, click here.

To access the Kim-Fine abstract, click here.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Jonsson Funk M, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Pate V, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes of vaginal mesh versus native tissue repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse [published online ahead of print February 12, 2013]. Int Urogynecol J. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2043-9.

2. Kim-Fine S, Occhino JA, Gebhart JB. Vaginal prolapse repair—Native tissue repair versus mesh augmentation: Newer isn’t always better [published online ahead of print January 17, 2013]. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2013;8(1):25-31doi:10.1007/s11884-012-0170-7.

More NEWS FOR YOUR PRACTICE…

appropriate for?

Have you read recent articles in OBG Management about the surgical use of mesh?

Click here to access the list.

- Michele Jonsson Funk, PhD, and colleagues from University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill concluded that using vaginal mesh versus native tissue for anterior prolapse repair is associated with 5-year increased risk of any repeat surgery, especially surgery for mesh removal.1

- Shunaha Kim-Fine, MD, and colleagues from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, believe that traditional native tissue repair is the best procedure for most women undergoing vaginal POP repair.2

UNC study details

Investigators from the Gillings School of Global Public Health at UNC studied health-care claims from 2005 to 2010. They identified women who, after undergoing anterior wall prolapse repair, experienced repeat surgery for recurrent prolapse or mesh removal. Of the initial 27,809 anterior prolapse surgeries, 6,871 (24.7%) included the use of vaginal mesh.1

5-year risk of repeat surgery. The authors determined that1:

- the 5-year cumulative risk of any repeat surgery was significantly higher with the use of vaginal mesh than with the use of native tissue (15.2% vs 9.8%, respectively; P .0001 with a risk of mesh revision or removal>

- the 5-year risk for recurrent prolapse surgery between both groups was comparable (10.4% vs 9.3%, P = .70).

Mayo Clinic study details

Researchers from Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Division of Gynecologic Surgery at Mayo Clinic reviewed the literature and compared vaginal native tissue repair with vaginal mesh–augmented repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Their report was published online ahead of print on January 17, 2013, in Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports.

The authors discuss POP; the procedures available to treat symptomatic POP; the Public Heath Notifications issued in 2008 and 2011 from U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding the use of transvaginal mesh in POP repair; and success, failure, and complication rates from both techniques.2

“Given the lack of robust and long-term data in these relatively new procedures for [mesh-augmentation] repair, we agree with the caution and prudence communication in the recent FDA warning,” state the authors.2 However, a caveat is offered that native tissue repair must utilize best principles of surgical technique and incorporate a multicompartment repair to achieve optimal outcome. The authors strongly advise that appropriate surgical technique, obtained only through adequate surgical training, can be improved for both repair procedures.2

Risks and complications from mesh. Mesh introduces unique risks related to the mesh itself, including mesh erosion, and complications, including new onset pain and dyspareunia following mesh-augmented repair. Complications are possibly related to the intrinsic properties of the mesh, (ie, shrinkage); to the patient (ie, scarring); or to the operative technique (ie, the placement/location of the mesh and increased tension on the mesh). The authors conclude that additional studies are needed, given the lack of robust and long-term data on mesh-augmentation repair of POP.2

“The evidence thus far has not shown that the benefits of mesh outweigh the added risks in vaginal prolapse repairs,” write the authors.2 Therefore, although patient-centered success rates for both techniques of POP repair are equivalent, the authors conclude: “there does not appear to be a clear advantage of mesh augmentation repair over native tissue in terms of anatomic success.”2

To access the Jonsson Funk abstract, click here.

To access the Kim-Fine abstract, click here.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Have you read recent articles in OBG Management about the surgical use of mesh?

Click here to access the list.

- Michele Jonsson Funk, PhD, and colleagues from University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill concluded that using vaginal mesh versus native tissue for anterior prolapse repair is associated with 5-year increased risk of any repeat surgery, especially surgery for mesh removal.1

- Shunaha Kim-Fine, MD, and colleagues from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, believe that traditional native tissue repair is the best procedure for most women undergoing vaginal POP repair.2

UNC study details

Investigators from the Gillings School of Global Public Health at UNC studied health-care claims from 2005 to 2010. They identified women who, after undergoing anterior wall prolapse repair, experienced repeat surgery for recurrent prolapse or mesh removal. Of the initial 27,809 anterior prolapse surgeries, 6,871 (24.7%) included the use of vaginal mesh.1

5-year risk of repeat surgery. The authors determined that1:

- the 5-year cumulative risk of any repeat surgery was significantly higher with the use of vaginal mesh than with the use of native tissue (15.2% vs 9.8%, respectively; P .0001 with a risk of mesh revision or removal>

- the 5-year risk for recurrent prolapse surgery between both groups was comparable (10.4% vs 9.3%, P = .70).

Mayo Clinic study details

Researchers from Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Division of Gynecologic Surgery at Mayo Clinic reviewed the literature and compared vaginal native tissue repair with vaginal mesh–augmented repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Their report was published online ahead of print on January 17, 2013, in Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports.

The authors discuss POP; the procedures available to treat symptomatic POP; the Public Heath Notifications issued in 2008 and 2011 from U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding the use of transvaginal mesh in POP repair; and success, failure, and complication rates from both techniques.2

“Given the lack of robust and long-term data in these relatively new procedures for [mesh-augmentation] repair, we agree with the caution and prudence communication in the recent FDA warning,” state the authors.2 However, a caveat is offered that native tissue repair must utilize best principles of surgical technique and incorporate a multicompartment repair to achieve optimal outcome. The authors strongly advise that appropriate surgical technique, obtained only through adequate surgical training, can be improved for both repair procedures.2

Risks and complications from mesh. Mesh introduces unique risks related to the mesh itself, including mesh erosion, and complications, including new onset pain and dyspareunia following mesh-augmented repair. Complications are possibly related to the intrinsic properties of the mesh, (ie, shrinkage); to the patient (ie, scarring); or to the operative technique (ie, the placement/location of the mesh and increased tension on the mesh). The authors conclude that additional studies are needed, given the lack of robust and long-term data on mesh-augmentation repair of POP.2

“The evidence thus far has not shown that the benefits of mesh outweigh the added risks in vaginal prolapse repairs,” write the authors.2 Therefore, although patient-centered success rates for both techniques of POP repair are equivalent, the authors conclude: “there does not appear to be a clear advantage of mesh augmentation repair over native tissue in terms of anatomic success.”2

To access the Jonsson Funk abstract, click here.

To access the Kim-Fine abstract, click here.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Jonsson Funk M, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Pate V, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes of vaginal mesh versus native tissue repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse [published online ahead of print February 12, 2013]. Int Urogynecol J. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2043-9.

2. Kim-Fine S, Occhino JA, Gebhart JB. Vaginal prolapse repair—Native tissue repair versus mesh augmentation: Newer isn’t always better [published online ahead of print January 17, 2013]. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2013;8(1):25-31doi:10.1007/s11884-012-0170-7.

More NEWS FOR YOUR PRACTICE…

appropriate for?

1. Jonsson Funk M, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Pate V, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes of vaginal mesh versus native tissue repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse [published online ahead of print February 12, 2013]. Int Urogynecol J. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2043-9.

2. Kim-Fine S, Occhino JA, Gebhart JB. Vaginal prolapse repair—Native tissue repair versus mesh augmentation: Newer isn’t always better [published online ahead of print January 17, 2013]. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2013;8(1):25-31doi:10.1007/s11884-012-0170-7.

More NEWS FOR YOUR PRACTICE…

appropriate for?

When is her pelvic pressure and bulge due to Pouch of Douglas hernia?

CASE: Pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

A 42-year-old G3P2 woman is referred to you by her primary care provider for pelvic organ prolapse. Her medical history reveals that she has been bothered by a sense of pelvic pressure and bulge progressing over several years, and she has noticed that her symptoms are particularly worse during and after bowel movements. She reports some improved bowel evacuation with external splinting of her perineum. Upon closer questioning, the patient reports a history of chronic constipation since childhood associated with straining and a sense of incomplete emptying. She reports spending up to 30 minutes three to four times per day on the commode to completely empty her bowels.

Physical examination reveals an overweight woman with a soft, nontender abdomen remarkable for laparoscopic incision scars from a previous tubal ligation. Inspection of the external genitalia at rest is normal. Cough stress test is negative. At maximum Valsalva, however, there is significant perineal ballooning present.

Speculum examination demonstrates grade 1 uterine prolapse, grade 1 cystocele, and grade 2 rectocele. There is no evidence of pelvic floor tension myalgia. She has weak pelvic muscle strength. Visualization of the anus at maximum Valsalva reveals there is some asymmetric rectal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall. Digital rectal exam is unremarkable.

Are these patient’s symptoms due to pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

Pelvic organ prolapse: A common problem

Pelvic organ prolapse has an estimated prevalence of 55% in women aged 50 to 59 years.1 More than 200,000 pelvic organ prolapse surgeries are performed annually in the United States.2 Typically, patients report:

- vaginal bulge causing discomfort

- pelvic pressure or heaviness, or

- rubbing of the vaginal bulge on undergarments.

In more advanced pelvic organ prolapse, patients may report voiding dysfunction or stool trapping that requires manual splinting of the prolapse to assist in bladder and bowel evacuation.

Pouch of Douglas hernia: A lesser-known

(recognized) phenomenon

Similar to pelvic organ prolapse, Pouch of Douglas hernia also can present with symptoms of:

- pelvic pressure

- vague perineal aching

- defecatory dysfunction.

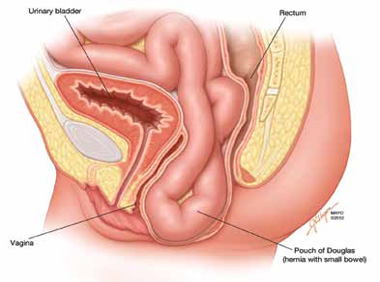

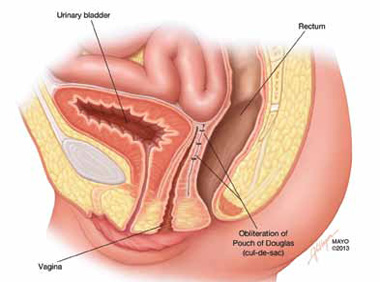

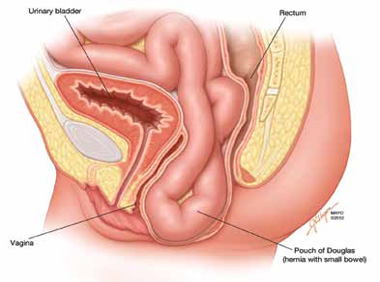

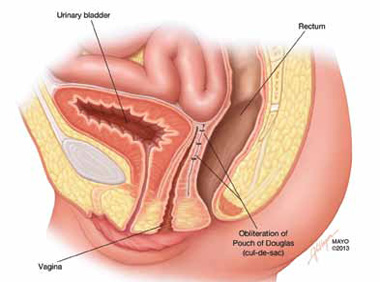

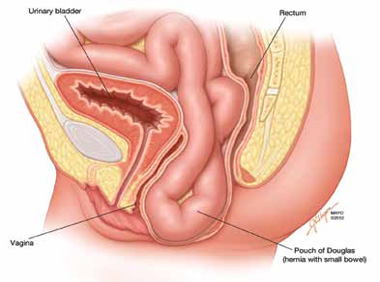

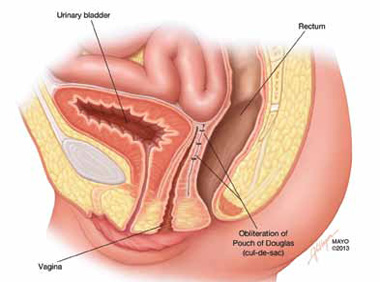

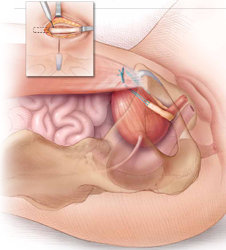

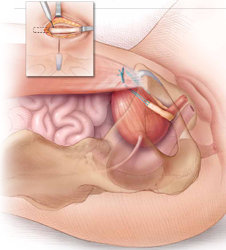

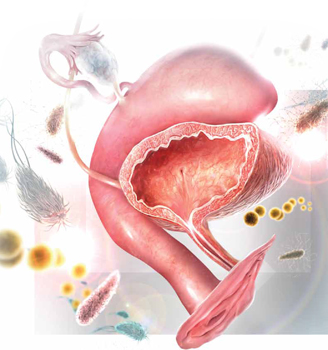

The phenomenon has been variably referred to in the literature as enterocele, descending perineum syndrome, peritoneocele, or Pouch of Douglas hernia. The concept was first introduced in 19663 and describes descent of the entire pelvic floor and small bowel through a hernia in the Pouch of Douglas (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1: Pouch of Douglas hernia. The pelvic floor and small bowel descend into the Pouch of Douglas.

How does it occur? The pathophysiology is thought to be related to excessive abdominal straining in individuals with chronic constipation. This results in diminished pelvic floor muscle tone. Eventually, the whole pelvic floor descends, becoming funnel shaped due to stretching of the puborectalis muscle. Thus, stool is expelled by force, mostly through forces on the anterior rectal wall (which tends to prolapse after stool evacuation, with accompanied mucus secretion, soreness, and irritation).

Clinical pearl: Given the rectal wall prolapse that occurs after stool evacuation in Pouch of Douglas hernia, some patients will describe a rectal lump that bleeds after a bowel movement. The sensation of the rectal lump from the anterior rectal wall prolapse causes further straining.

Your patient reports pelvic pressure and bulge.

How do you proceed?

Physical examination

Look for perineal ballooning. Physical examination should start with inspection of the external genitalia. This inspection will identify any pelvic organ prolapse at or beyond the introitus. However, a Pouch of Douglas hernia will be missed if the patient is not examined during Valsalva or maximal strain. This maneuver will demonstrate the classic finding of perineal ballooning and is crucial to a final diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia. Normally, the perineum will descend 1 cm to 2 cm during maximal strain; in Pouch of Douglas hernias, the perineum can descend up to 4 cm to 8 cm.4

Clinical pearl: It should be noted that, often, patients will not have a great deal of vaginal prolapse accompanying the perineal ballooning. In our opinion, this finding distinguishes Pouch of Douglas hernia from a vaginal vault prolapse caused by an enterocele.

Is rectal prolapse present? Beyond perineal ballooning, the presence of rectal prolapse should be evaluated. A rectocele of some degree is usually present. Asymmetric rectal prolapse affecting the anterior aspect of the rectal wall is consistent with a Pouch of Douglas hernia. This anatomic finding should be distinguished from true circumferential rectal prolapse, which remains in the differential diagnosis.

Basing the diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia on physical examination alone can be difficult. Therefore, imaging studies are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Imaging investigations

Several imaging modalities can be used to diagnose such disorders of the pelvic floor as Pouch of Douglas hernia. These include:

- dynamic colpocystoproctography5

- defecography with oral barium6

- dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7

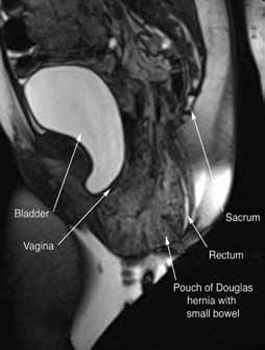

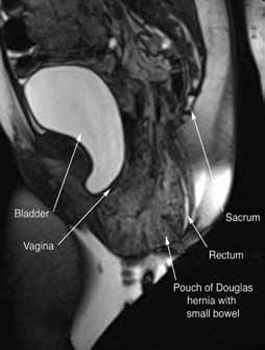

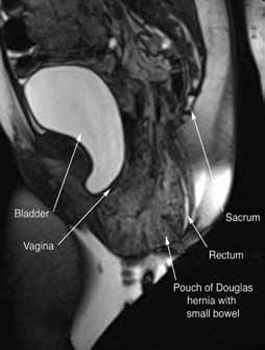

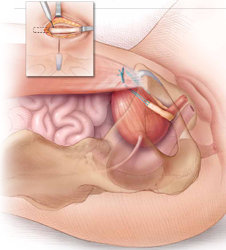

In our experience, dynamic pelvic MRI has a high accuracy rate for diagnosing Pouch of Douglas hernia. FIGURE 2 illustrates the large Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with loops of small bowel. Perineal descent of the anorectal junction more than 3 cm below the pubococcygeal line during maximal straining is a diagnostic finding on imaging.7

FIGURE 2: MRI

Sagittal MRI during maximal Valsalva straining, demonstrating Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with small bowel.

What are your patient’s treatment options?

Reduce straining during bowel movements. The primary goal of treatment for Pouch of Douglas hernia should be relief of bothersome symptoms. Therefore, further damage can be prevented by eliminating straining during defecation. This can be accomplished with a bowel regimen that combines an irritant suppository (glycerin or bisacodyl) with a fiber supplement (the latter to increase bulk of the stool). Oral laxatives have limited use as many patients have lax anal sphincters and liquid stool could cause fecal incontinence.

Pelvic floor strengthening. The importance of pelvic floor physical therapy should be stressed. Patients can benefit from the use of modalities such as biofeedback to learn appropriate pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques during defecation.8 While there is limited published evidence supporting the use of pelvic floor physical therapy, our anecdotal experience suggests that patients can gain considerable benefit with such conservative therapy.

Surgical therapy

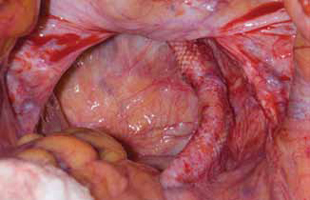

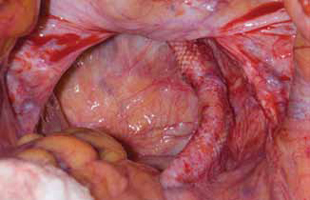

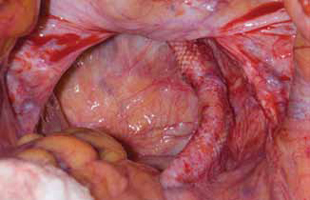

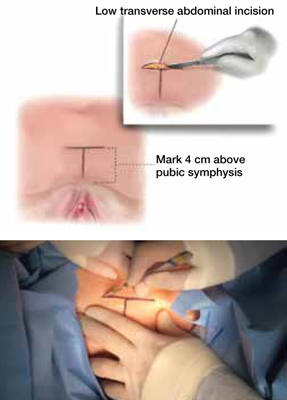

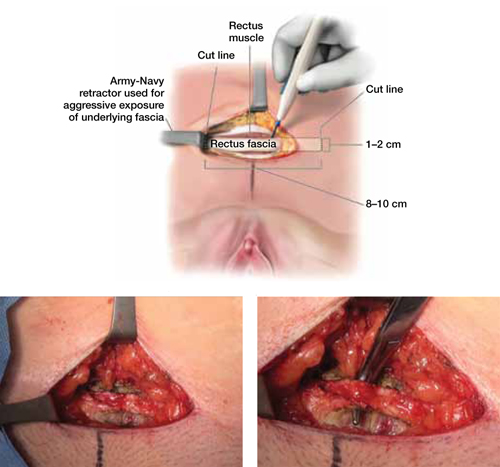

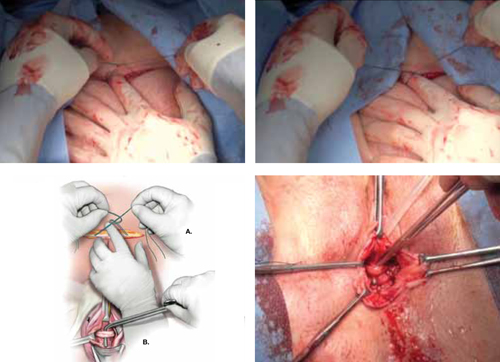

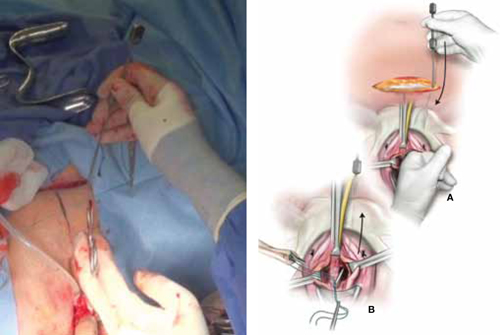

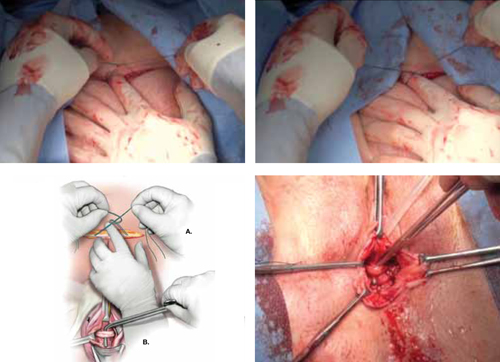

Surgical repair of Pouch of Douglas hernia requires obliteration of the deep cul-de-sac (to prevent the small bowel from filling this space) and simultaneous pelvic floor reconstruction of the vaginal apex and any other compartments that are prolapsing (if pelvic organ prolapse is present). In our experience, these patients typically have derived greatest benefit from an abdominal approach. This usually can be accomplished with a sacrocolpopexy (if vaginal vault prolapse exists) with a Moschowitz or Halban procedure,9 uterosacral ligament plication, or a modified sacrocolpopexy with mesh augmentation to the sidewalls of the pelvis.10 There are currently no studies supporting one particular approach over another, but the most important feature of a surgical intervention is obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5).

FIGURE 3: Open cul-de-sac. Open cul-de-sac after a prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy in a patient with a Pouch of Douglas hernia.

FIGURE 4: Obliterated cul-de-sac. Obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication. Care is taken to prevent obstruction of the rectum at this level.

FIGURE 5: Cul-de-sac obliteration. Schematic diagram of obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication sutures.

Final takeaways

Pouch of Douglas hernia is an important but often unrecognized cause of pelvic pressure and defecatory dysfunction. Perineal ballooning during maximal straining is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, with final diagnosis confirmed with various functional imaging studies of the pelvic floor. Management should include both conservative and surgical interventions to alleviate and prevent recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The authors would like to thank Mr. John Hagen, Medical Illustrator, Mayo Clinic, for producing the illustrations in Figures 1 and 5.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

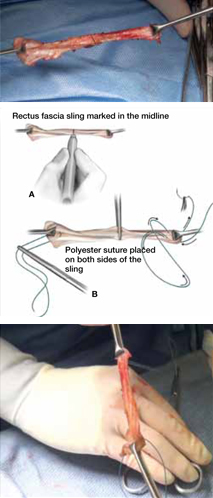

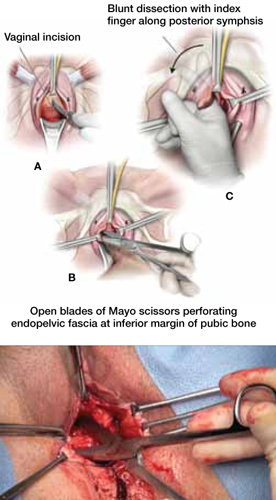

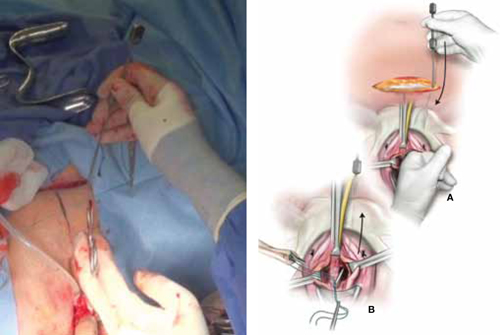

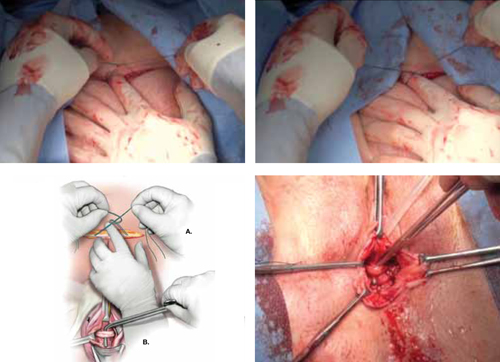

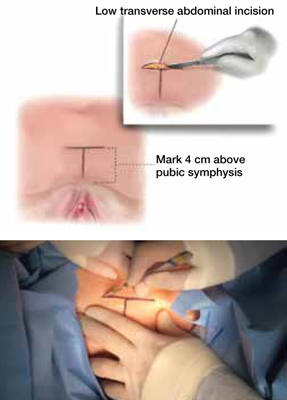

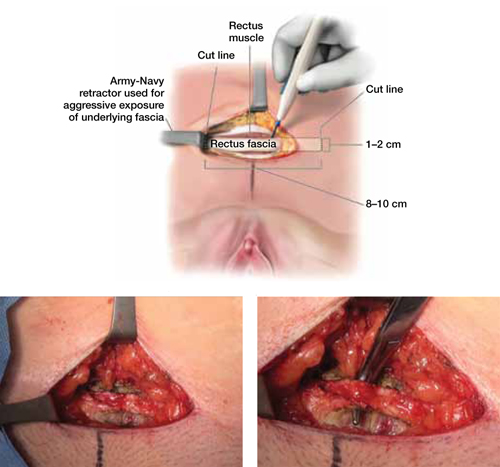

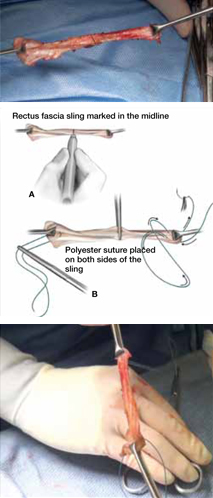

When and how to place an autologous rectus fascia

pubovaginal sling

Mickey Karram, MD, and Dani Zoorob, MD (Surgical Techniques, November 2012)

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (Update, October 2012)

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

Mickey Karram, MD, and Janelle Evans, MD (Surgical Techniques, February 2012)

1. Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299-305.

2. Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108-115.

3. Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482.

4. Hardcastle JD. The descending perineum syndrome. Practitioner. 1969;203(217):612-619.

5. Maglinte DD, Bartram CI, Hale DA, et al. Functional imaging of the pelvic floor. Radiology. 2011;258(1):23-39.

6. Roos JE, Weishaupt D, Wildermuth S, Willmann JK, Marincek B, Hilfiker PR. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):817-832.

7. Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399-411.

8. Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130.

9. Moschcowitz AV. The pathogenesis anatomy and cure of prolapse of the rectum. Surg Gyncol Obstetrics. 1912;15:7-21.

10. Gosselink MJ, van Dam JH, Huisman WM, Ginai AZ, Schouten WR. Treatment of enterocele by obliteration of the pelvic inlet. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(7):940-944.

CASE: Pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

A 42-year-old G3P2 woman is referred to you by her primary care provider for pelvic organ prolapse. Her medical history reveals that she has been bothered by a sense of pelvic pressure and bulge progressing over several years, and she has noticed that her symptoms are particularly worse during and after bowel movements. She reports some improved bowel evacuation with external splinting of her perineum. Upon closer questioning, the patient reports a history of chronic constipation since childhood associated with straining and a sense of incomplete emptying. She reports spending up to 30 minutes three to four times per day on the commode to completely empty her bowels.

Physical examination reveals an overweight woman with a soft, nontender abdomen remarkable for laparoscopic incision scars from a previous tubal ligation. Inspection of the external genitalia at rest is normal. Cough stress test is negative. At maximum Valsalva, however, there is significant perineal ballooning present.

Speculum examination demonstrates grade 1 uterine prolapse, grade 1 cystocele, and grade 2 rectocele. There is no evidence of pelvic floor tension myalgia. She has weak pelvic muscle strength. Visualization of the anus at maximum Valsalva reveals there is some asymmetric rectal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall. Digital rectal exam is unremarkable.

Are these patient’s symptoms due to pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

Pelvic organ prolapse: A common problem

Pelvic organ prolapse has an estimated prevalence of 55% in women aged 50 to 59 years.1 More than 200,000 pelvic organ prolapse surgeries are performed annually in the United States.2 Typically, patients report:

- vaginal bulge causing discomfort

- pelvic pressure or heaviness, or

- rubbing of the vaginal bulge on undergarments.

In more advanced pelvic organ prolapse, patients may report voiding dysfunction or stool trapping that requires manual splinting of the prolapse to assist in bladder and bowel evacuation.

Pouch of Douglas hernia: A lesser-known

(recognized) phenomenon

Similar to pelvic organ prolapse, Pouch of Douglas hernia also can present with symptoms of:

- pelvic pressure

- vague perineal aching

- defecatory dysfunction.

The phenomenon has been variably referred to in the literature as enterocele, descending perineum syndrome, peritoneocele, or Pouch of Douglas hernia. The concept was first introduced in 19663 and describes descent of the entire pelvic floor and small bowel through a hernia in the Pouch of Douglas (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1: Pouch of Douglas hernia. The pelvic floor and small bowel descend into the Pouch of Douglas.

How does it occur? The pathophysiology is thought to be related to excessive abdominal straining in individuals with chronic constipation. This results in diminished pelvic floor muscle tone. Eventually, the whole pelvic floor descends, becoming funnel shaped due to stretching of the puborectalis muscle. Thus, stool is expelled by force, mostly through forces on the anterior rectal wall (which tends to prolapse after stool evacuation, with accompanied mucus secretion, soreness, and irritation).

Clinical pearl: Given the rectal wall prolapse that occurs after stool evacuation in Pouch of Douglas hernia, some patients will describe a rectal lump that bleeds after a bowel movement. The sensation of the rectal lump from the anterior rectal wall prolapse causes further straining.

Your patient reports pelvic pressure and bulge.

How do you proceed?

Physical examination

Look for perineal ballooning. Physical examination should start with inspection of the external genitalia. This inspection will identify any pelvic organ prolapse at or beyond the introitus. However, a Pouch of Douglas hernia will be missed if the patient is not examined during Valsalva or maximal strain. This maneuver will demonstrate the classic finding of perineal ballooning and is crucial to a final diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia. Normally, the perineum will descend 1 cm to 2 cm during maximal strain; in Pouch of Douglas hernias, the perineum can descend up to 4 cm to 8 cm.4

Clinical pearl: It should be noted that, often, patients will not have a great deal of vaginal prolapse accompanying the perineal ballooning. In our opinion, this finding distinguishes Pouch of Douglas hernia from a vaginal vault prolapse caused by an enterocele.

Is rectal prolapse present? Beyond perineal ballooning, the presence of rectal prolapse should be evaluated. A rectocele of some degree is usually present. Asymmetric rectal prolapse affecting the anterior aspect of the rectal wall is consistent with a Pouch of Douglas hernia. This anatomic finding should be distinguished from true circumferential rectal prolapse, which remains in the differential diagnosis.

Basing the diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia on physical examination alone can be difficult. Therefore, imaging studies are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Imaging investigations

Several imaging modalities can be used to diagnose such disorders of the pelvic floor as Pouch of Douglas hernia. These include:

- dynamic colpocystoproctography5

- defecography with oral barium6

- dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7

In our experience, dynamic pelvic MRI has a high accuracy rate for diagnosing Pouch of Douglas hernia. FIGURE 2 illustrates the large Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with loops of small bowel. Perineal descent of the anorectal junction more than 3 cm below the pubococcygeal line during maximal straining is a diagnostic finding on imaging.7

FIGURE 2: MRI

Sagittal MRI during maximal Valsalva straining, demonstrating Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with small bowel.

What are your patient’s treatment options?

Reduce straining during bowel movements. The primary goal of treatment for Pouch of Douglas hernia should be relief of bothersome symptoms. Therefore, further damage can be prevented by eliminating straining during defecation. This can be accomplished with a bowel regimen that combines an irritant suppository (glycerin or bisacodyl) with a fiber supplement (the latter to increase bulk of the stool). Oral laxatives have limited use as many patients have lax anal sphincters and liquid stool could cause fecal incontinence.

Pelvic floor strengthening. The importance of pelvic floor physical therapy should be stressed. Patients can benefit from the use of modalities such as biofeedback to learn appropriate pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques during defecation.8 While there is limited published evidence supporting the use of pelvic floor physical therapy, our anecdotal experience suggests that patients can gain considerable benefit with such conservative therapy.

Surgical therapy

Surgical repair of Pouch of Douglas hernia requires obliteration of the deep cul-de-sac (to prevent the small bowel from filling this space) and simultaneous pelvic floor reconstruction of the vaginal apex and any other compartments that are prolapsing (if pelvic organ prolapse is present). In our experience, these patients typically have derived greatest benefit from an abdominal approach. This usually can be accomplished with a sacrocolpopexy (if vaginal vault prolapse exists) with a Moschowitz or Halban procedure,9 uterosacral ligament plication, or a modified sacrocolpopexy with mesh augmentation to the sidewalls of the pelvis.10 There are currently no studies supporting one particular approach over another, but the most important feature of a surgical intervention is obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5).

FIGURE 3: Open cul-de-sac. Open cul-de-sac after a prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy in a patient with a Pouch of Douglas hernia.

FIGURE 4: Obliterated cul-de-sac. Obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication. Care is taken to prevent obstruction of the rectum at this level.

FIGURE 5: Cul-de-sac obliteration. Schematic diagram of obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication sutures.

Final takeaways

Pouch of Douglas hernia is an important but often unrecognized cause of pelvic pressure and defecatory dysfunction. Perineal ballooning during maximal straining is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, with final diagnosis confirmed with various functional imaging studies of the pelvic floor. Management should include both conservative and surgical interventions to alleviate and prevent recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The authors would like to thank Mr. John Hagen, Medical Illustrator, Mayo Clinic, for producing the illustrations in Figures 1 and 5.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

When and how to place an autologous rectus fascia

pubovaginal sling

Mickey Karram, MD, and Dani Zoorob, MD (Surgical Techniques, November 2012)

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (Update, October 2012)

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

Mickey Karram, MD, and Janelle Evans, MD (Surgical Techniques, February 2012)

CASE: Pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

A 42-year-old G3P2 woman is referred to you by her primary care provider for pelvic organ prolapse. Her medical history reveals that she has been bothered by a sense of pelvic pressure and bulge progressing over several years, and she has noticed that her symptoms are particularly worse during and after bowel movements. She reports some improved bowel evacuation with external splinting of her perineum. Upon closer questioning, the patient reports a history of chronic constipation since childhood associated with straining and a sense of incomplete emptying. She reports spending up to 30 minutes three to four times per day on the commode to completely empty her bowels.

Physical examination reveals an overweight woman with a soft, nontender abdomen remarkable for laparoscopic incision scars from a previous tubal ligation. Inspection of the external genitalia at rest is normal. Cough stress test is negative. At maximum Valsalva, however, there is significant perineal ballooning present.

Speculum examination demonstrates grade 1 uterine prolapse, grade 1 cystocele, and grade 2 rectocele. There is no evidence of pelvic floor tension myalgia. She has weak pelvic muscle strength. Visualization of the anus at maximum Valsalva reveals there is some asymmetric rectal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall. Digital rectal exam is unremarkable.

Are these patient’s symptoms due to pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

Pelvic organ prolapse: A common problem

Pelvic organ prolapse has an estimated prevalence of 55% in women aged 50 to 59 years.1 More than 200,000 pelvic organ prolapse surgeries are performed annually in the United States.2 Typically, patients report:

- vaginal bulge causing discomfort

- pelvic pressure or heaviness, or

- rubbing of the vaginal bulge on undergarments.

In more advanced pelvic organ prolapse, patients may report voiding dysfunction or stool trapping that requires manual splinting of the prolapse to assist in bladder and bowel evacuation.

Pouch of Douglas hernia: A lesser-known

(recognized) phenomenon

Similar to pelvic organ prolapse, Pouch of Douglas hernia also can present with symptoms of:

- pelvic pressure

- vague perineal aching

- defecatory dysfunction.

The phenomenon has been variably referred to in the literature as enterocele, descending perineum syndrome, peritoneocele, or Pouch of Douglas hernia. The concept was first introduced in 19663 and describes descent of the entire pelvic floor and small bowel through a hernia in the Pouch of Douglas (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1: Pouch of Douglas hernia. The pelvic floor and small bowel descend into the Pouch of Douglas.

How does it occur? The pathophysiology is thought to be related to excessive abdominal straining in individuals with chronic constipation. This results in diminished pelvic floor muscle tone. Eventually, the whole pelvic floor descends, becoming funnel shaped due to stretching of the puborectalis muscle. Thus, stool is expelled by force, mostly through forces on the anterior rectal wall (which tends to prolapse after stool evacuation, with accompanied mucus secretion, soreness, and irritation).

Clinical pearl: Given the rectal wall prolapse that occurs after stool evacuation in Pouch of Douglas hernia, some patients will describe a rectal lump that bleeds after a bowel movement. The sensation of the rectal lump from the anterior rectal wall prolapse causes further straining.

Your patient reports pelvic pressure and bulge.

How do you proceed?

Physical examination

Look for perineal ballooning. Physical examination should start with inspection of the external genitalia. This inspection will identify any pelvic organ prolapse at or beyond the introitus. However, a Pouch of Douglas hernia will be missed if the patient is not examined during Valsalva or maximal strain. This maneuver will demonstrate the classic finding of perineal ballooning and is crucial to a final diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia. Normally, the perineum will descend 1 cm to 2 cm during maximal strain; in Pouch of Douglas hernias, the perineum can descend up to 4 cm to 8 cm.4

Clinical pearl: It should be noted that, often, patients will not have a great deal of vaginal prolapse accompanying the perineal ballooning. In our opinion, this finding distinguishes Pouch of Douglas hernia from a vaginal vault prolapse caused by an enterocele.

Is rectal prolapse present? Beyond perineal ballooning, the presence of rectal prolapse should be evaluated. A rectocele of some degree is usually present. Asymmetric rectal prolapse affecting the anterior aspect of the rectal wall is consistent with a Pouch of Douglas hernia. This anatomic finding should be distinguished from true circumferential rectal prolapse, which remains in the differential diagnosis.

Basing the diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia on physical examination alone can be difficult. Therefore, imaging studies are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Imaging investigations

Several imaging modalities can be used to diagnose such disorders of the pelvic floor as Pouch of Douglas hernia. These include:

- dynamic colpocystoproctography5

- defecography with oral barium6

- dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7

In our experience, dynamic pelvic MRI has a high accuracy rate for diagnosing Pouch of Douglas hernia. FIGURE 2 illustrates the large Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with loops of small bowel. Perineal descent of the anorectal junction more than 3 cm below the pubococcygeal line during maximal straining is a diagnostic finding on imaging.7

FIGURE 2: MRI

Sagittal MRI during maximal Valsalva straining, demonstrating Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with small bowel.

What are your patient’s treatment options?

Reduce straining during bowel movements. The primary goal of treatment for Pouch of Douglas hernia should be relief of bothersome symptoms. Therefore, further damage can be prevented by eliminating straining during defecation. This can be accomplished with a bowel regimen that combines an irritant suppository (glycerin or bisacodyl) with a fiber supplement (the latter to increase bulk of the stool). Oral laxatives have limited use as many patients have lax anal sphincters and liquid stool could cause fecal incontinence.

Pelvic floor strengthening. The importance of pelvic floor physical therapy should be stressed. Patients can benefit from the use of modalities such as biofeedback to learn appropriate pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques during defecation.8 While there is limited published evidence supporting the use of pelvic floor physical therapy, our anecdotal experience suggests that patients can gain considerable benefit with such conservative therapy.

Surgical therapy

Surgical repair of Pouch of Douglas hernia requires obliteration of the deep cul-de-sac (to prevent the small bowel from filling this space) and simultaneous pelvic floor reconstruction of the vaginal apex and any other compartments that are prolapsing (if pelvic organ prolapse is present). In our experience, these patients typically have derived greatest benefit from an abdominal approach. This usually can be accomplished with a sacrocolpopexy (if vaginal vault prolapse exists) with a Moschowitz or Halban procedure,9 uterosacral ligament plication, or a modified sacrocolpopexy with mesh augmentation to the sidewalls of the pelvis.10 There are currently no studies supporting one particular approach over another, but the most important feature of a surgical intervention is obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5).

FIGURE 3: Open cul-de-sac. Open cul-de-sac after a prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy in a patient with a Pouch of Douglas hernia.

FIGURE 4: Obliterated cul-de-sac. Obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication. Care is taken to prevent obstruction of the rectum at this level.

FIGURE 5: Cul-de-sac obliteration. Schematic diagram of obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication sutures.

Final takeaways

Pouch of Douglas hernia is an important but often unrecognized cause of pelvic pressure and defecatory dysfunction. Perineal ballooning during maximal straining is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, with final diagnosis confirmed with various functional imaging studies of the pelvic floor. Management should include both conservative and surgical interventions to alleviate and prevent recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The authors would like to thank Mr. John Hagen, Medical Illustrator, Mayo Clinic, for producing the illustrations in Figures 1 and 5.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

When and how to place an autologous rectus fascia

pubovaginal sling

Mickey Karram, MD, and Dani Zoorob, MD (Surgical Techniques, November 2012)

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (Update, October 2012)

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

Mickey Karram, MD, and Janelle Evans, MD (Surgical Techniques, February 2012)

1. Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299-305.

2. Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108-115.

3. Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482.

4. Hardcastle JD. The descending perineum syndrome. Practitioner. 1969;203(217):612-619.

5. Maglinte DD, Bartram CI, Hale DA, et al. Functional imaging of the pelvic floor. Radiology. 2011;258(1):23-39.

6. Roos JE, Weishaupt D, Wildermuth S, Willmann JK, Marincek B, Hilfiker PR. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):817-832.

7. Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399-411.

8. Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130.

9. Moschcowitz AV. The pathogenesis anatomy and cure of prolapse of the rectum. Surg Gyncol Obstetrics. 1912;15:7-21.

10. Gosselink MJ, van Dam JH, Huisman WM, Ginai AZ, Schouten WR. Treatment of enterocele by obliteration of the pelvic inlet. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(7):940-944.

1. Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299-305.

2. Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108-115.

3. Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482.

4. Hardcastle JD. The descending perineum syndrome. Practitioner. 1969;203(217):612-619.

5. Maglinte DD, Bartram CI, Hale DA, et al. Functional imaging of the pelvic floor. Radiology. 2011;258(1):23-39.

6. Roos JE, Weishaupt D, Wildermuth S, Willmann JK, Marincek B, Hilfiker PR. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):817-832.

7. Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399-411.

8. Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130.

9. Moschcowitz AV. The pathogenesis anatomy and cure of prolapse of the rectum. Surg Gyncol Obstetrics. 1912;15:7-21.

10. Gosselink MJ, van Dam JH, Huisman WM, Ginai AZ, Schouten WR. Treatment of enterocele by obliteration of the pelvic inlet. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(7):940-944.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Clinical pearls at physical exam

Treatment options

Have you tried these innovative alternatives to antibiotics for UTI prevention?

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Recurrent UTI and antibiotic resistance

A 53-year-old postmenopausal woman with a history of culture-proven recurrent Escherichia coli urinary tract infections (UTIs) presents to the clinic with symptoms of UTI. She was previously treated with a postcoital regimen of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, based on sensitivities identified by culture. A past work-up of her upper and lower urinary tract was negative. You send a catheterized specimen for culture; again, E. coli is identified as the pathogen but proves resistant to her current antibiotic regimen.

What treatment alternatives, aside from antibiotics, are available for this patient—and how might they affect resistance?

Increased antibiotic usage has led to greater bacterial resistance, which is perpetuated by clonal spread. Resistant strains of E. coli have been found in household members, suggesting host-host transmission as a mechanism for dissemination. Alternative treatments that reduce the use of antibiotics may minimize bacterial resistance and increase the efficacy of treatment. In the TABLE , we summarize alternative approaches to the treatment of recurrent UTI. We also describe a strategy to alleviate symptoms.

Alternatives to antibiotics in the treatment and prevention of recurrent UTI

| Category | Type | Examples and doses, if recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal estrogen | Conjugated estrogen cream Estradiol

| Premarin cream, 0.5–2 g vaginally twice weekly

|

| Nutritive agents | Cranberry juice Cranberry tablets Cystopurin Lactobacilli Blueberry products | Not recommended 1 tablet (300 to 400 mg, depending on manufacturer) twice daily Not recommended Vivag, EcoVag, 1 capsule daily by vagina for 5 days, then once weekly for 10 weeks Not recommended |

| Anti-infective drugs | Methenamine hippurate Methenamine mandelate Methylene blue | Urex or Hiprex, 1 g orally twice daily Mandelamine, 1 g orally 4 times daily Future therapy |

| Urinary acidifiers | Vitamin C/ascorbic acid | 1–3 g orally 3–4 times daily |

| Herbal remedies | Uva ursi Forskolin | Not recommended for long-term use Not recommended |

| Behavioral changes | Adequate hydration Postcoital voiding |

Vaginal estrogen is the only proven alternative to antibiotics for postmenopausal women

A lack of estrogen is a risk factor for UTI and is associated with atrophic mucosa, leading to decreased colonization with lactobacilli, increased vaginal pH, and E. coli colonization.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravaginal estriol cream versus placebo in 93 postmenopausal women found a significant decrease in the rate of UTI among women who used the cream.1 After 8 months of follow-up, the incidence of UTI was 0.5 vs 5.9 episodes per patient-year (P <.001). Interestingly, all pretreatment cultures were negative for lactobacilli. One month after treatment, 61% of women in the estriol group were culture-positive for lactobacilli, compared with 0% of the placebo group.1

A 2008 Cochrane review of nine studies concluded that vaginal estrogen reduces the number of UTIs in postmenopausal women, with variation based on the type of estrogen and duration of use.2

Adverse effects are mild

Twenty-eight percent of the estriol group in the randomized trial described above withdrew from treatment, with 20% citing local side effects, including vaginal irritation, burning, or itching—all of which were mild and self-limited.1 Other possible adverse effects include breast tenderness, vaginal bleeding or spotting, and discharge.2

Clinical recommendations

Given the efficacy of this therapy, we recommend topical estrogen for postmenopausal patients with recurrent UTIs.

Cranberry juice may reduce UTI, but many patients withdraw

from treatment

Cranberries belong to the Vaccinium species, which contains all flavonoids, including anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins. It was previously thought that the acidification of urine produced an antibacterial effect, but several trials have documented no change in urine levels of hippuric acid when cranberry products are given, with no acidification of the urine.3 Current theory suggests that cranberries prevent bacteria from adhering to the uroepithelial cells of the walls of the bladder, by blocking expression of E. coli’s adhesion molecule, P. fimbriae, so that bacteria are unable to penetrate the mucosal surface.4,5 The major benefit of cranberry products over antibiotic prophylaxis is that they do not have the potential for resistance.4

A 2008 Cochrane review concluded that cranberry juice may reduce symptomatic UTIs, particularly among young, sexually active women—but there is a high rate of withdrawal from treatment.6 The optimal method of administration and dose remain unclear. In contrast, two recent randomized, controlled trials—published after the Cochrane review—found no difference in the rate of recurrent UTI in premenopausal women.7,8 Adverse effects in these two trials included constipation, heartburn, loose stools, vaginal itching and dryness, and migraines. Of note, there was no statistical difference in side effects between the cranberry and placebo groups.7

Vaccinium tablets may be protective in older women

Cranberry extracts of 500 mg to 1,000 mg daily have been compared with antimicrobial prophylaxis in two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The trials demonstrated mixed benefits. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was associated with a lower rate of UTI in younger women, compared with cranberry extracts alone (P=.02), while cranberry extracts were slightly more effective than trimethoprim alone in older women.9,10 Cranberry tablets were not associated with bacterial resistance, were cheaper, and were viewed as a more natural option. The interventions were equally well tolerated.

Overall efficacy of cranberry tablets is unclear. Side effects, albeit mild, included gastrointestinal disturbances, vaginal complaints, and rash or urticaria. There was no significant difference in the rate of adverse effects between antimicrobial treatment and cranberry tablets.9

Cystopurin has not been studied

Cystopurin is an over-the-counter (OTC) tablet containing cranberry extract and potassium citrate that is taken three times daily (3 g/dose) for 2 days. Interestingly, although a proposed mechanism for the efficacy of vitamin C and cranberry juice has been a reduction of pH, potassium citrate is an alkalizing agent that is reported to relieve burning and reduce urinary urgency and frequency. No studies have assessed this medication in the treatment of a UTI or its symptoms.

Clinical recommendations

The evidence is mixed on the use of cranberry products to reduce recurrent UTI. However, given the limited side effects associated with these products, we offer cranberry tablets to patients who have recurrent UTIs who are interested in a more natural alternative.

We generally do not recommend cranberry juice because the added fluid volume tends to exacerbate frequency and urgency symptoms.

Lactobacilli suppositories may benefit

postmenopausal women

Lactobacilli are fastidious gram-positive rods and are usually the dominant component of the vaginal flora.11 They prevent colonization and infection by more virulent bacteria by competing for adhesion receptors and nutrients as well as producing antimicrobial substances such as hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid. A decrease in lactobacilli leaves the urinary tract susceptible to infectious organisms that may colonize the vaginal mucosa and increase the risk of recurrent UTI.12-14

A 2008 review of randomized, controlled trials of oral lactobacilli and UTI was inconclusive, due to inconsistent dosing strategies and small sample sizes.15 A 2011 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of Lactin-V, a lactobacilli vaginal suppository, found that it reduced the rate of recurrent UTI. Lactin-V contains a hydrogen-peroxide–producing Lactobacillus crispatus developed as a probiotic that was determined to be safe and tolerable as a vaginal suppository in a phase 1 trial.16 The phase 2 trial enrolled 100 young premenopausal women with a history of recurrent UTI who took either Lactin-V or placebo daily for 5 days, then weekly for 10 weeks. Women in the Lactin-V group who had high levels of L. crispatus colonization experienced a significant reduction in the rate of UTI (15% vs 27% in the placebo group), but the effect did not reach statistical significance.14

Little difference in adverse effects

Adverse effects were reported among 56% of patients who received Lactin-V versus 50% of those given placebo. The most common of these were vaginal discharge, itching, and moderate abdominal discomfort.14 Although lactobacillus can potentially promote UTI, this phenomenon is rare.11

Regrettably, Lactin-V is not currently available in the United States. However, there are other lactobacilli vaginal suppositories on the market ( TABLE ). Given the low risk associated with their use, they should be considered as an alternative for patients who cannot or will not use estrogen.

Clinical recommendations

Probiotics such as lactobacilli are categorized as “dietary supplements”; as such, they are not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration. We recommend the use of lactobacilli suppositories in postmenopausal women who have a contraindication to (or prefer to avoid) vaginal estrogen.

Skip blueberry products for now

Like cranberries, blueberries belong to the Vaccinium species and are thought to interfere with bacterial adhesion to the walls of the bladder. One in vitro trial suggests that blueberries also have antiproliferation effects, although no clinical studies have been performed to date to further investigate safety or efficacy.4 Consequently, we do not recommend use of these products.

Methenamine salts may benefit some populations

These anti-infective agents, including methenamine hippurate and methenamine mandelate, often are used to prevent UTI. They are found in combination OTC medications, such as Prosed DS and Urelle. Methenamine salts are bacteriostatic to all urinary tract pathogens due to their production of formaldehyde.3,16

Although methenamine produces varying concentrations of formaldehyde, depending on the acidity of the urine, there is no evidence that acidified urine enhances methenamine’s effects.16

Advantages of methenamine include the fact that it produces no changes in gut flora, poses no risk for antimicrobial resistance, and has low toxicity. It also is low in cost.17

Methenamine is contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency or severe hepatic disease.

Adverse reactions are generally mild and include gastrointestinal disturbances, skin rashes, dysuria, and microscopic hematuria.16

Methenamine hippurate

A 2007 Cochrane review, deemed up to date in 2010, analyzed 13 randomized, controlled trials involving 2,032 participants. Subgroup analyses suggested that methenamine hippurate may be of some benefit to patients without renal tract abnormalities; these patients experienced significantly reduced symptoms after short-term treatment of 1 week or less.

Patients with spinal injury do not appear to benefit from treatment, according to a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Lee and colleagues.18

Methenamine mandelate

This agent is commonly used to prevent recurrent UTI, although there is a paucity of randomized, controlled trials to support its use. One such trial in patients with neurogenic bladder found that methenamine mandelate with acidification was superior to placebo (P <.02) for preventing UTI.19 Beyond this population, however, it’s difficult to assess methenamine’s efficacy in the prevention of recurrent UTI.

Methylene blue may be useful in the elderly

Methylene blue is a light-activated compound described as “photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy” (PACT). Once illuminated, it becomes a bactericide, causing excitation of electrons followed by one of two reactions:

- reduction oxidation

- formation of a labile singlet oxygen and then oxidation.

This makes resistance unlikely.

In an in vitro study, methylene blue was as effective as levofloxacin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia, Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus, and Staphylococcus aureus when illuminated.

Potential benefits of this mode of treatment include local exposure and no drug interactions.

We suggest that methylene blue be placed and illuminated with a special catheter that would target UTI in the elderly population, among whom 52% of UTIs are associated with use of catheters.20 In vivo effects, adverse effects, and cost are not known, which limits current applicability of this compound.

Vitamin C may reduce UTI in pregnancy

The proposed mechanism for the efficacy of vitamin C for the treatment of UTI is the acidification of urine, which is believed to reduce the proliferation of bacteria. However, several studies have shown that vitamin C, at various doses, does not reliably reduce urine pH.15,21,22 Nonetheless, ascorbic acid was tested for its effect on UTI prevention during pregnancy.

In a single-blind trial, 110 pregnant women were divided into two groups (55 in each group):

- One group received ferrous sulfate (200 mg), folic acid (5 mg), and vitamin C (100 mg) daily for 3 months

- The other received ferrous sulfate (200 mg) and folic acid (5 mg) daily for 3 months.

Urine was cultured monthly. The incidence of UTI was significantly lower in the group receiving vitamin C (12.7%), compared with the control group (29.1%) (P=.03; odds ratio [OR], 0.35).23

Uva ursi may have a prophylactic effect

Uva ursi (UVA-E) is one of the most commonly used herbal supplements for treatment of UTI. The crude extract from Bearberry or Arctostaphylos uva-ursi has been shown to act as an antimicrobial by decreasing bacterial adherence.24 In addition, investigators have found the extract to have diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties.25,26 However, few studies have explored its efficacy. One randomized, controlled trial that included 57 women (30 allocated to UVA-E and 27 to placebo) found a statistically significant reduction in the rate of recurrence at 1 year among women taking UVA-E, compared with those who did not.27

Note that the women in this trial were given UVA-E for 1 month only. Long-term use of this herb has not been studied and may cause liver damage.

In a mouse model, forskolin reduced urinary-tract E. coli

This herb is derived from Indian coleus (Coleus forskohlii), a member of the mint family. It has been used primarily for its antiasthmatic, spasmolytic, and antihypertensive effects. It is believed to activate adenylate cyclase, increasing intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) concentrations and activating a number of key enzymatic pathways.28

The findings of a recent observational study have spurred the use of forskolin in the treatment of recurrent UTI.29 In the study, conducted on mice, when forskolin was injected into the bladder, intracellular E. coli decreased.

It is theorized that the incorporation of bacteria into intracellular vesicles of the bladder prevents exposure to antibiotics. When combined with an antibiotic, forskolin may increase bacterial elimination and thus lower the risk of recurrent infection. However, no randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of this treatment.

Patients who are already taking antihypertensive medications should be cautious when using this herb, as it may lead to a drop in blood pressure.

Behavior changes are risk-free

One of the natural mechanisms that promotes bacterial elimination and prevents bacterial growth is urination. A recent review article on the subject found several contradictory studies on the effect of fluid intake on the risk of UTI.30 Although there is no definitive evidence that susceptibility to UTI is linked to fluid intake, adequate hydration may reduce the risk of recurrent infection.

Similarly, voiding shortly after sexual intercourse may prevent UTI. One case-control study found a modest protective effect in patients who voided after intercourse.31

Clinical recommendations

Given the low risk of these measures, it seems reasonable to recommend postcoital voiding and increased fluid intake to prevent recurrent UTI.

A focus on symptoms

Phenazopyridine, the chemical found in numerous OTC medications, such as Pyridium, AZO, and Uristat, was discovered by Swiss chemist Bernhard Joos in the 1950s. Its mechanism of action is still unclear, but approximately 65% of the oral dose is excreted by the kidneys, where it has a direct topical analgesic effect.32,33

Clinical recommendations

Patients should be warned that phenazopyridine will lead to orange urine discoloration.

The medication is generally well tolerated but should be used with caution in patients with acute renal failure, hemolytic anemia, or methemoglobinemia, as it may exacerbate these conditions.

Last words

Recurrent UTIs are common and impose a significant financial burden on our healthcare system. Although there are several antibiotic treatment options and dosing regimens available, increasing antibiotic resistance has made management of recurrent UTIs more difficult. Effective alternative treatments that reduce the reliance on antibiotics may minimize bacterial resistance and decrease the financial burden of this common condition.

CASE: Resolved

To reduce vaginal E. coli, the patient is started on vaginal estrogen cream. She is also advised to purchase cranberry tablets to help prevent future infections. Last, she is counseled about behavioral changes she can make and prescribed a short course of antibiotics to treat her culture-proven infection.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

URINARY PROBLEMS?

CLICK HERE to access 9 articles about treating urinary incontinence and urinary tract infections, published in OBG MANAGEMENTin 2012.

1. Raz R, Stamm W. A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(11):753-756.

2. Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, Albert X, Ng CW. Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD005131.-

3. Mayrer AR, Andriole VT. Urinary tract antiseptics. Med Clin North Am. 1982;66(1):199-208.

4. Jepson RG, Craig JC. A systematic review of the evidence for cranberries and blueberries in UTI prevention. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(6):738-745.

5. Salvatore S, Salvatore S, Cattoni E, et al. Urinary tract infections in women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156(2):131-136.

6. Jepson RG, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD001321.-

7. Stapleton AE, Dziura J, Hooton TM, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infection and urinary Escherichia coli in women ingesting cranberry juice daily: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):143-150.

8. Barbosa-Cesnik C, Brown MB, Buxton M, Zhang L, DeBusscher J, Foxman B. Cranberry juice fails to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection: results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(1):23-30.

9. Beerepoot MAJ, Reit G, Nys S, et al. Cranberries vs antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1270-1278.

10. McMurdo MET, Argo I, Phillips G, Daly F, Davey P. Cranberry or trimethoprim for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections? A randomized controlled trial in older women. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(2):389-395.

11. Barrons R, Tassone D. Use of Lactobacillus probiotics for bacterial genitourinary infections in women: a review. Clinical Therapeutics. 2008;30(3):453-468.

12. Miller JL, Krieger JN. Urinary tract infections: cranberry juice underwear, and probiotics in the 21st century. Urol Clin N Am. 2002;29(3):695-699.

13. Osset J, Bartolome R, Garcia E, et al. Assessment of the capacity of Lactobacillus to inhibit the growth of uropathogens and block their adhesion to vaginal epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(3):485-491.

14. Stapleton AE, Au-Yeung M, Hooton TM, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(10):1212-1217.