User login

Fluorescein, 10% dextrose topped other media for visualizing ureteral patency

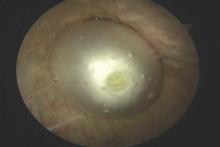

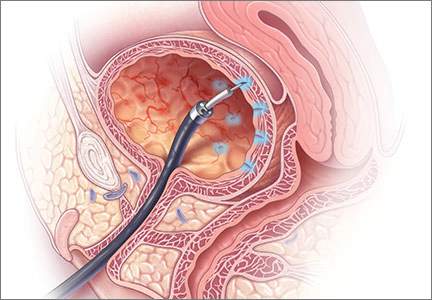

DENVER – Ureteral jets were best visualized during cystoscopy with the help of 10% dextrose or sodium fluorescein, instead of phenazopyridine or normal saline, findings from a multicenter, randomized controlled trial suggested.

User satisfaction also was significantly higher with 10% dextrose and fluorescein, compared with the other interventions, Luis Espaillat-Rijo, MD, reported at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

Average total cystoscopy time, time to first jet visualization, and rates of postoperative urinary tract infections were similar among groups, noted Dr. Espaillat-Rijo, who conducted the research at the Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston.

Historically, surgeons used intravenous indigo carmine to evaluate ureteral patency during intraoperative cystoscopy, but the Food and Drug Administration announced a shortage in June 2014 that has not resolved.

Hypothesizing that not all alternatives confer equivalent visibility, the researchers randomly assigned 174 female cystoscopy patients aged 18 years or older to one of four interventions: intravenous sodium fluorescein, preoperative oral phenazopyridine (Pyridium), 10% dextrose solution, or normal saline (control).

The researchers excluded patients with kidney disease or a history of surgery for renal or ureteral obstruction. The primary outcome was visibility of the urine jet, which surgeons described as clearly visible, somewhat visible, or not at all visible. Surgeons also were asked how satisfied or confident they were in assessing ureteral patency with the test media, Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said.

The study groups were demographically similar. Fluorescein and 10% dextrose resulted in the highest visibility, with more than 80% of surgeons describing the ureteral jets as “clearly visible” with these modalities, compared with about 60% of cases in which phenazopyridine or saline was used (P = .001, for differences among groups).

Similarly, more than 80% of surgeons reported being very or somewhat satisfied with 10% dextrose and fluorescein, while about 60% of surgeons said they were very or somewhat satisfied with phenazopyridine and saline (P less than .001).

“It was interesting that phenazopyridine was not more visible than control saline,” Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said. “Surgeons also noted that it was harder to evaluate the uroepithelium when it was tinged with Pyridium.”

Use of these interventions did not add time to the procedure, he noted. Total cystoscopy time averaged 4.5 minutes and was similar among groups. Average time to detection of the first jet also was similar among all four interventions, ranging from 1.8 to 2.5 minutes.

None of the patients had allergic reactions or adverse events considered related to an intervention. The rates of urinary tract infection ranged from approximately 22% to 30% and were similar among groups. Three ureteral obstructions were correctly identified and released intraoperatively, and none was identified postoperatively. One patient had an episode of acute urinary retention 4 days after surgery that led to bladder rupture.

“Because we had no postoperative ureteral injuries, we were unable to detect the sensitivity or specificity for each method,” Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said. “Another limitation is that we did not have the power to find a difference in our secondary outcomes, and indigo carmine was not used as a control.”

The Cleveland Clinic Florida sponsored the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – Ureteral jets were best visualized during cystoscopy with the help of 10% dextrose or sodium fluorescein, instead of phenazopyridine or normal saline, findings from a multicenter, randomized controlled trial suggested.

User satisfaction also was significantly higher with 10% dextrose and fluorescein, compared with the other interventions, Luis Espaillat-Rijo, MD, reported at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

Average total cystoscopy time, time to first jet visualization, and rates of postoperative urinary tract infections were similar among groups, noted Dr. Espaillat-Rijo, who conducted the research at the Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston.

Historically, surgeons used intravenous indigo carmine to evaluate ureteral patency during intraoperative cystoscopy, but the Food and Drug Administration announced a shortage in June 2014 that has not resolved.

Hypothesizing that not all alternatives confer equivalent visibility, the researchers randomly assigned 174 female cystoscopy patients aged 18 years or older to one of four interventions: intravenous sodium fluorescein, preoperative oral phenazopyridine (Pyridium), 10% dextrose solution, or normal saline (control).

The researchers excluded patients with kidney disease or a history of surgery for renal or ureteral obstruction. The primary outcome was visibility of the urine jet, which surgeons described as clearly visible, somewhat visible, or not at all visible. Surgeons also were asked how satisfied or confident they were in assessing ureteral patency with the test media, Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said.

The study groups were demographically similar. Fluorescein and 10% dextrose resulted in the highest visibility, with more than 80% of surgeons describing the ureteral jets as “clearly visible” with these modalities, compared with about 60% of cases in which phenazopyridine or saline was used (P = .001, for differences among groups).

Similarly, more than 80% of surgeons reported being very or somewhat satisfied with 10% dextrose and fluorescein, while about 60% of surgeons said they were very or somewhat satisfied with phenazopyridine and saline (P less than .001).

“It was interesting that phenazopyridine was not more visible than control saline,” Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said. “Surgeons also noted that it was harder to evaluate the uroepithelium when it was tinged with Pyridium.”

Use of these interventions did not add time to the procedure, he noted. Total cystoscopy time averaged 4.5 minutes and was similar among groups. Average time to detection of the first jet also was similar among all four interventions, ranging from 1.8 to 2.5 minutes.

None of the patients had allergic reactions or adverse events considered related to an intervention. The rates of urinary tract infection ranged from approximately 22% to 30% and were similar among groups. Three ureteral obstructions were correctly identified and released intraoperatively, and none was identified postoperatively. One patient had an episode of acute urinary retention 4 days after surgery that led to bladder rupture.

“Because we had no postoperative ureteral injuries, we were unable to detect the sensitivity or specificity for each method,” Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said. “Another limitation is that we did not have the power to find a difference in our secondary outcomes, and indigo carmine was not used as a control.”

The Cleveland Clinic Florida sponsored the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – Ureteral jets were best visualized during cystoscopy with the help of 10% dextrose or sodium fluorescein, instead of phenazopyridine or normal saline, findings from a multicenter, randomized controlled trial suggested.

User satisfaction also was significantly higher with 10% dextrose and fluorescein, compared with the other interventions, Luis Espaillat-Rijo, MD, reported at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week, sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

Average total cystoscopy time, time to first jet visualization, and rates of postoperative urinary tract infections were similar among groups, noted Dr. Espaillat-Rijo, who conducted the research at the Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston.

Historically, surgeons used intravenous indigo carmine to evaluate ureteral patency during intraoperative cystoscopy, but the Food and Drug Administration announced a shortage in June 2014 that has not resolved.

Hypothesizing that not all alternatives confer equivalent visibility, the researchers randomly assigned 174 female cystoscopy patients aged 18 years or older to one of four interventions: intravenous sodium fluorescein, preoperative oral phenazopyridine (Pyridium), 10% dextrose solution, or normal saline (control).

The researchers excluded patients with kidney disease or a history of surgery for renal or ureteral obstruction. The primary outcome was visibility of the urine jet, which surgeons described as clearly visible, somewhat visible, or not at all visible. Surgeons also were asked how satisfied or confident they were in assessing ureteral patency with the test media, Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said.

The study groups were demographically similar. Fluorescein and 10% dextrose resulted in the highest visibility, with more than 80% of surgeons describing the ureteral jets as “clearly visible” with these modalities, compared with about 60% of cases in which phenazopyridine or saline was used (P = .001, for differences among groups).

Similarly, more than 80% of surgeons reported being very or somewhat satisfied with 10% dextrose and fluorescein, while about 60% of surgeons said they were very or somewhat satisfied with phenazopyridine and saline (P less than .001).

“It was interesting that phenazopyridine was not more visible than control saline,” Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said. “Surgeons also noted that it was harder to evaluate the uroepithelium when it was tinged with Pyridium.”

Use of these interventions did not add time to the procedure, he noted. Total cystoscopy time averaged 4.5 minutes and was similar among groups. Average time to detection of the first jet also was similar among all four interventions, ranging from 1.8 to 2.5 minutes.

None of the patients had allergic reactions or adverse events considered related to an intervention. The rates of urinary tract infection ranged from approximately 22% to 30% and were similar among groups. Three ureteral obstructions were correctly identified and released intraoperatively, and none was identified postoperatively. One patient had an episode of acute urinary retention 4 days after surgery that led to bladder rupture.

“Because we had no postoperative ureteral injuries, we were unable to detect the sensitivity or specificity for each method,” Dr. Espaillat-Rijo said. “Another limitation is that we did not have the power to find a difference in our secondary outcomes, and indigo carmine was not used as a control.”

The Cleveland Clinic Florida sponsored the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: Major finding: Visibility of the ureteral jet was significantly greater with 10% dextrose and oral phenazopyridine than with intravenous fluorescein or saline (P = .001).

Data source: A multicenter, randomized controlled trial of 174 women undergoing intraoperative cystoscopy.

Disclosures: The Cleveland Clinic Florida sponsored the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy offers advantages over abdominal route

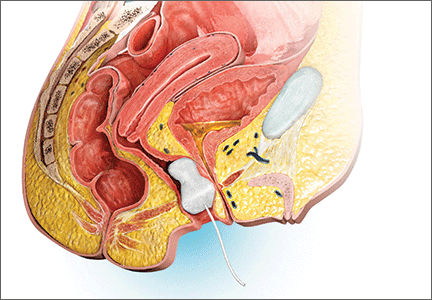

BOSTON – Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy offers some distinct advantages over the abdominal route for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse, including reduced intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital stays, according to findings from a new research review.

“We wanted to compare the efficiency and safety of abdominal sacral colpopexy and laparoscopic sacral colpopexy for the treatment of pelvic organ collapse,” Juan Liu, MD, of Guangzhou Medical University in China said at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week, held by the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons.

Analyses directly comparing the safety and effectiveness of the two surgical routes are low in number, Dr. Liu added.

The researchers looked at published articles, written in English or Chinese, that were either retrospective analyses or randomized controlled trial studies examining laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) or abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC), with follow-up times of at least 30 days.

Studies that investigated robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy were excluded, as well as studies for which there were no specific feature data or for which the full text of the study was inaccessible. Of 1,807 articles identified, 10 studies containing 3,816 cases were included for the analysis.

The studies were used to compare laparoscopic and abdominal sacrocolpopexy on the following criteria: operating time; blood loss; hospital length of stay; intraoperative complications such as urinary, bladder, and rectal injury; and postoperative complications such as infection, intestinal obstruction, mesh exposure, new urinary incontinence, and dyspareunia. Weighted mean difference was calculated to account for the different sample sizes across the studies.

The weighted mean difference in intraoperative blood loss in the laparoscopic cohort, compared with the abdominal cohort, was –100.68 mL (P less than .01). Hospital length of stay was also significantly reduced in the laparoscopic cohort, with a weighted mean difference of –1.77 days (P less than .01). The odds ratio for gastrointestinal complications was 0.30 for the laparoscopic route, compared with the abdominal route (P less than .01).

Additionally, pulmonary complications and blood transfusions were also found to be reduced with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, compared with abdominal sacrocolpopexy, with an odds ratio of 0.59 (P = .02) and 0.47 (P = .03), respectively.

But the review found little difference in other areas. The weighted mean difference for operating time in the laparoscopic cohort was 0.06 minutes, compared with the abdominal cohort, which was not statistically significant (P= .84). And there was not a statistically significant difference between the two surgical approaches in urinary complications (OR, 0.41; P = .11), cardiovascular complications (OR, 0.31; P = .49), or mesh exposure (OR, 1.60, P = .18).

No funding source for this study was disclosed. Dr. Liu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy offers some distinct advantages over the abdominal route for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse, including reduced intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital stays, according to findings from a new research review.

“We wanted to compare the efficiency and safety of abdominal sacral colpopexy and laparoscopic sacral colpopexy for the treatment of pelvic organ collapse,” Juan Liu, MD, of Guangzhou Medical University in China said at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week, held by the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons.

Analyses directly comparing the safety and effectiveness of the two surgical routes are low in number, Dr. Liu added.

The researchers looked at published articles, written in English or Chinese, that were either retrospective analyses or randomized controlled trial studies examining laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) or abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC), with follow-up times of at least 30 days.

Studies that investigated robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy were excluded, as well as studies for which there were no specific feature data or for which the full text of the study was inaccessible. Of 1,807 articles identified, 10 studies containing 3,816 cases were included for the analysis.

The studies were used to compare laparoscopic and abdominal sacrocolpopexy on the following criteria: operating time; blood loss; hospital length of stay; intraoperative complications such as urinary, bladder, and rectal injury; and postoperative complications such as infection, intestinal obstruction, mesh exposure, new urinary incontinence, and dyspareunia. Weighted mean difference was calculated to account for the different sample sizes across the studies.

The weighted mean difference in intraoperative blood loss in the laparoscopic cohort, compared with the abdominal cohort, was –100.68 mL (P less than .01). Hospital length of stay was also significantly reduced in the laparoscopic cohort, with a weighted mean difference of –1.77 days (P less than .01). The odds ratio for gastrointestinal complications was 0.30 for the laparoscopic route, compared with the abdominal route (P less than .01).

Additionally, pulmonary complications and blood transfusions were also found to be reduced with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, compared with abdominal sacrocolpopexy, with an odds ratio of 0.59 (P = .02) and 0.47 (P = .03), respectively.

But the review found little difference in other areas. The weighted mean difference for operating time in the laparoscopic cohort was 0.06 minutes, compared with the abdominal cohort, which was not statistically significant (P= .84). And there was not a statistically significant difference between the two surgical approaches in urinary complications (OR, 0.41; P = .11), cardiovascular complications (OR, 0.31; P = .49), or mesh exposure (OR, 1.60, P = .18).

No funding source for this study was disclosed. Dr. Liu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy offers some distinct advantages over the abdominal route for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse, including reduced intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital stays, according to findings from a new research review.

“We wanted to compare the efficiency and safety of abdominal sacral colpopexy and laparoscopic sacral colpopexy for the treatment of pelvic organ collapse,” Juan Liu, MD, of Guangzhou Medical University in China said at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week, held by the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons.

Analyses directly comparing the safety and effectiveness of the two surgical routes are low in number, Dr. Liu added.

The researchers looked at published articles, written in English or Chinese, that were either retrospective analyses or randomized controlled trial studies examining laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) or abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC), with follow-up times of at least 30 days.

Studies that investigated robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy were excluded, as well as studies for which there were no specific feature data or for which the full text of the study was inaccessible. Of 1,807 articles identified, 10 studies containing 3,816 cases were included for the analysis.

The studies were used to compare laparoscopic and abdominal sacrocolpopexy on the following criteria: operating time; blood loss; hospital length of stay; intraoperative complications such as urinary, bladder, and rectal injury; and postoperative complications such as infection, intestinal obstruction, mesh exposure, new urinary incontinence, and dyspareunia. Weighted mean difference was calculated to account for the different sample sizes across the studies.

The weighted mean difference in intraoperative blood loss in the laparoscopic cohort, compared with the abdominal cohort, was –100.68 mL (P less than .01). Hospital length of stay was also significantly reduced in the laparoscopic cohort, with a weighted mean difference of –1.77 days (P less than .01). The odds ratio for gastrointestinal complications was 0.30 for the laparoscopic route, compared with the abdominal route (P less than .01).

Additionally, pulmonary complications and blood transfusions were also found to be reduced with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, compared with abdominal sacrocolpopexy, with an odds ratio of 0.59 (P = .02) and 0.47 (P = .03), respectively.

But the review found little difference in other areas. The weighted mean difference for operating time in the laparoscopic cohort was 0.06 minutes, compared with the abdominal cohort, which was not statistically significant (P= .84). And there was not a statistically significant difference between the two surgical approaches in urinary complications (OR, 0.41; P = .11), cardiovascular complications (OR, 0.31; P = .49), or mesh exposure (OR, 1.60, P = .18).

No funding source for this study was disclosed. Dr. Liu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY WEEK

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The weighted mean difference in intraoperative blood loss in the laparoscopic cohort, compared with the abdominal cohort, was –100.68 mL (P less than .01).

Data source: Retrospective review of 10 studies involving 3,816 sacrocolpopexy cases.

Disclosures: Dr. Liu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Botox for overactive bladder led to low rate of catheterization

DENVER – Less than 2% of onabotulinumtoxinA injections for idiopathic detrusor overactivity resulted in clean intermittent catheterization, a substantially lower rate than previously found, Juzar Jamnagerwalla, MD, reported at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week.

These included two cases of acute urinary retention and one case in which a patient complained of problems voiding and had a postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) of 353 mL, said Dr. Jamnagerwalla of Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. Taken together, the findings suggest that postprocedural PVR can usually be managed safely by observation alone, which may reassure patients who are considering treatment options for overactive bladder, he added.

But these “strict” criteria contrast with real-world practice, in which patients with postprocedural PVR often are observed without CIC unless they have subjective complaints or other contraindications, Dr. Jamnagerwalla said. The discrepancy is especially relevant because patients with overactive bladder who decline onabotulinumtoxinA often cite the risk of CIC as the reason, he added.

To better understand CIC rates at Cedars-Sinai, Dr. Jamnagerwalla and his colleagues reviewed 27 months of records from patients with idiopathic detrusor overactivity who received injections of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA given by female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery physicians. The patients were followed up immediately and 2 weeks later, but underwent CIC only if they could not void or had PVRs above 350 mL and subjective voiding complaints.

In all, 99 patients received a total of 187 injections, of which only 3 (1.6%) led to urinary retention requiring CIC. The median postprocedure PVR was 117 mL. About three-quarters of patients had PVRs less than 200 mL, 29 (16%) had PVRs between 200 mL and 350 mL, and 13 (7%) had PVRs greater than 350 mL.

Age, body mass index, and preprocedure PVR did not predict urinary retention in the univariate analysis, Dr. Jamnagerwalla said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The results support the practice of observing patients with elevated PVRs after Botox, as long as they do not develop obstructive symptoms, he advised.

“While it remains important to counsel patients on the risk of urinary retention after Botox injection for idiopathic detrusor overactivity, patients can be reassured that the true rate of retention requiring CIC is relatively low,” he said.

Dr. Jamnagerwalla reported no funding sources and reported having no financial disclosures. Two coauthors reported ties to Boston Scientific, Astora, and Allergan.

DENVER – Less than 2% of onabotulinumtoxinA injections for idiopathic detrusor overactivity resulted in clean intermittent catheterization, a substantially lower rate than previously found, Juzar Jamnagerwalla, MD, reported at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week.

These included two cases of acute urinary retention and one case in which a patient complained of problems voiding and had a postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) of 353 mL, said Dr. Jamnagerwalla of Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. Taken together, the findings suggest that postprocedural PVR can usually be managed safely by observation alone, which may reassure patients who are considering treatment options for overactive bladder, he added.

But these “strict” criteria contrast with real-world practice, in which patients with postprocedural PVR often are observed without CIC unless they have subjective complaints or other contraindications, Dr. Jamnagerwalla said. The discrepancy is especially relevant because patients with overactive bladder who decline onabotulinumtoxinA often cite the risk of CIC as the reason, he added.

To better understand CIC rates at Cedars-Sinai, Dr. Jamnagerwalla and his colleagues reviewed 27 months of records from patients with idiopathic detrusor overactivity who received injections of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA given by female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery physicians. The patients were followed up immediately and 2 weeks later, but underwent CIC only if they could not void or had PVRs above 350 mL and subjective voiding complaints.

In all, 99 patients received a total of 187 injections, of which only 3 (1.6%) led to urinary retention requiring CIC. The median postprocedure PVR was 117 mL. About three-quarters of patients had PVRs less than 200 mL, 29 (16%) had PVRs between 200 mL and 350 mL, and 13 (7%) had PVRs greater than 350 mL.

Age, body mass index, and preprocedure PVR did not predict urinary retention in the univariate analysis, Dr. Jamnagerwalla said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The results support the practice of observing patients with elevated PVRs after Botox, as long as they do not develop obstructive symptoms, he advised.

“While it remains important to counsel patients on the risk of urinary retention after Botox injection for idiopathic detrusor overactivity, patients can be reassured that the true rate of retention requiring CIC is relatively low,” he said.

Dr. Jamnagerwalla reported no funding sources and reported having no financial disclosures. Two coauthors reported ties to Boston Scientific, Astora, and Allergan.

DENVER – Less than 2% of onabotulinumtoxinA injections for idiopathic detrusor overactivity resulted in clean intermittent catheterization, a substantially lower rate than previously found, Juzar Jamnagerwalla, MD, reported at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week.

These included two cases of acute urinary retention and one case in which a patient complained of problems voiding and had a postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) of 353 mL, said Dr. Jamnagerwalla of Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles. Taken together, the findings suggest that postprocedural PVR can usually be managed safely by observation alone, which may reassure patients who are considering treatment options for overactive bladder, he added.

But these “strict” criteria contrast with real-world practice, in which patients with postprocedural PVR often are observed without CIC unless they have subjective complaints or other contraindications, Dr. Jamnagerwalla said. The discrepancy is especially relevant because patients with overactive bladder who decline onabotulinumtoxinA often cite the risk of CIC as the reason, he added.

To better understand CIC rates at Cedars-Sinai, Dr. Jamnagerwalla and his colleagues reviewed 27 months of records from patients with idiopathic detrusor overactivity who received injections of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA given by female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery physicians. The patients were followed up immediately and 2 weeks later, but underwent CIC only if they could not void or had PVRs above 350 mL and subjective voiding complaints.

In all, 99 patients received a total of 187 injections, of which only 3 (1.6%) led to urinary retention requiring CIC. The median postprocedure PVR was 117 mL. About three-quarters of patients had PVRs less than 200 mL, 29 (16%) had PVRs between 200 mL and 350 mL, and 13 (7%) had PVRs greater than 350 mL.

Age, body mass index, and preprocedure PVR did not predict urinary retention in the univariate analysis, Dr. Jamnagerwalla said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The results support the practice of observing patients with elevated PVRs after Botox, as long as they do not develop obstructive symptoms, he advised.

“While it remains important to counsel patients on the risk of urinary retention after Botox injection for idiopathic detrusor overactivity, patients can be reassured that the true rate of retention requiring CIC is relatively low,” he said.

Dr. Jamnagerwalla reported no funding sources and reported having no financial disclosures. Two coauthors reported ties to Boston Scientific, Astora, and Allergan.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 187 injections, 1.6% of led to acute urinary retention requiring clean intermittent catheterization.

Data source: A single-center, retrospective study of 99 patients receiving 187 onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Disclosures: Dr. Jamnagerwalla and his colleagues reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

Incontinence trial finds small advantage for Botox over sacral neuromodulation

OnabotulinumtoxinA decreased daily episodes of urinary incontinence by a small amount, compared with sacral neuromodulation, but did not appear to impact several quality of life measures and raised the rates of urinary tract infection and self-catheterization, according to findings from a comparative effectiveness study.

In an open-label randomized trial directly comparing the two approaches for refractory urgency incontinence, onabotulinumtoxinA showed a statistically significant advantage over sacral neuromodulation, but whether this translates into a clinically significant difference is unclear.

“Overall, these findings make it uncertain whether onabotulinumtoxinA provides a clinically important net benefit, compared with sacral neuromodulation,” said Cindy L. Amundsen, MD, of Duke University, Durham N.C., and her associates.

Noting that a recent systematic review of the literature found insufficient evidence to recommend one of these treatments over the other, the investigators performed their study at nine medical centers participating in the National Institutes of Health’s Pelvic Floor Disorder Network. Study participants included 386 women who had a minimum of six urgency incontinence episodes per day and whose symptoms persisted despite treatment with at least one behavioral or physical therapy intervention and at least two medical therapies. They were followed up at 6 months.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the 190 women who received a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA showed a mean reduction of 3.9 daily episodes of urinary incontinence, compared with a reduction of 3.3 episodes for the 174 women who underwent sacral neuromodulation. The onabotulinumtoxinA group also showed slightly greater improvement on the Overactive Bladder Short Form score for symptom bother and on the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire, Dr. Amundsen and her associates reported (JAMA. 2016;316[13]:1366-1374).

However, there were no significant differences between the two study groups in measures of convenience, adverse effects, treatment preference, or other quality of life factors. And onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with a higher rate of urinary tract infection (35% vs. 11%) and of intermittent self-catheterization (8% vs. 0% at 1 month).

This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Dr. Amundsen reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Medtronic (maker of the InterStim sacral neuromodulation device), Allergan (maker of Botox), and Axonics.

OnabotulinumtoxinA decreased daily episodes of urinary incontinence by a small amount, compared with sacral neuromodulation, but did not appear to impact several quality of life measures and raised the rates of urinary tract infection and self-catheterization, according to findings from a comparative effectiveness study.

In an open-label randomized trial directly comparing the two approaches for refractory urgency incontinence, onabotulinumtoxinA showed a statistically significant advantage over sacral neuromodulation, but whether this translates into a clinically significant difference is unclear.

“Overall, these findings make it uncertain whether onabotulinumtoxinA provides a clinically important net benefit, compared with sacral neuromodulation,” said Cindy L. Amundsen, MD, of Duke University, Durham N.C., and her associates.

Noting that a recent systematic review of the literature found insufficient evidence to recommend one of these treatments over the other, the investigators performed their study at nine medical centers participating in the National Institutes of Health’s Pelvic Floor Disorder Network. Study participants included 386 women who had a minimum of six urgency incontinence episodes per day and whose symptoms persisted despite treatment with at least one behavioral or physical therapy intervention and at least two medical therapies. They were followed up at 6 months.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the 190 women who received a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA showed a mean reduction of 3.9 daily episodes of urinary incontinence, compared with a reduction of 3.3 episodes for the 174 women who underwent sacral neuromodulation. The onabotulinumtoxinA group also showed slightly greater improvement on the Overactive Bladder Short Form score for symptom bother and on the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire, Dr. Amundsen and her associates reported (JAMA. 2016;316[13]:1366-1374).

However, there were no significant differences between the two study groups in measures of convenience, adverse effects, treatment preference, or other quality of life factors. And onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with a higher rate of urinary tract infection (35% vs. 11%) and of intermittent self-catheterization (8% vs. 0% at 1 month).

This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Dr. Amundsen reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Medtronic (maker of the InterStim sacral neuromodulation device), Allergan (maker of Botox), and Axonics.

OnabotulinumtoxinA decreased daily episodes of urinary incontinence by a small amount, compared with sacral neuromodulation, but did not appear to impact several quality of life measures and raised the rates of urinary tract infection and self-catheterization, according to findings from a comparative effectiveness study.

In an open-label randomized trial directly comparing the two approaches for refractory urgency incontinence, onabotulinumtoxinA showed a statistically significant advantage over sacral neuromodulation, but whether this translates into a clinically significant difference is unclear.

“Overall, these findings make it uncertain whether onabotulinumtoxinA provides a clinically important net benefit, compared with sacral neuromodulation,” said Cindy L. Amundsen, MD, of Duke University, Durham N.C., and her associates.

Noting that a recent systematic review of the literature found insufficient evidence to recommend one of these treatments over the other, the investigators performed their study at nine medical centers participating in the National Institutes of Health’s Pelvic Floor Disorder Network. Study participants included 386 women who had a minimum of six urgency incontinence episodes per day and whose symptoms persisted despite treatment with at least one behavioral or physical therapy intervention and at least two medical therapies. They were followed up at 6 months.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the 190 women who received a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA showed a mean reduction of 3.9 daily episodes of urinary incontinence, compared with a reduction of 3.3 episodes for the 174 women who underwent sacral neuromodulation. The onabotulinumtoxinA group also showed slightly greater improvement on the Overactive Bladder Short Form score for symptom bother and on the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire, Dr. Amundsen and her associates reported (JAMA. 2016;316[13]:1366-1374).

However, there were no significant differences between the two study groups in measures of convenience, adverse effects, treatment preference, or other quality of life factors. And onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with a higher rate of urinary tract infection (35% vs. 11%) and of intermittent self-catheterization (8% vs. 0% at 1 month).

This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Dr. Amundsen reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Medtronic (maker of the InterStim sacral neuromodulation device), Allergan (maker of Botox), and Axonics.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 190 women who received a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA showed a mean reduction of 3.9 daily episodes of urinary incontinence, compared with a reduction of 3.3 episodes for the 174 women who underwent sacral neuromodulation.

Data source: A multicenter open-label randomized trial involving 386 women followed for 6 months.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Dr. Amundsen reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Medtronic (maker of the InterStim sacral neuromodulation device), Allergan (maker of Botox), and Axonics.

Absorbable suture performs well in sacrocolpopexy with mesh

DENVER – Using absorbable polydioxanone suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was associated with a mesh erosion rate of just 1.6%, according to a single-center, 1-year prospective study of 64 patients.

That is substantially less than typical erosion rates of about 5% when permanent suture is used, Danielle Taylor, DO, of Akron (Ohio ) General Medical Center said at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The researchers observed no anatomic failures or suture extrusions, and patients reported significant postoperative improvements on several validated measures of quality of life.

“Larger samples and longer follow-up may be needed,” said Dr. Taylor. “But our study suggests that permanent, nondissolving suture material may not be necessary for sacrocolpopexy.”

Sacrocolpopexy with mesh usually involves using nonabsorbable suture to attach its anterior and posterior arms to the vaginal mucosa. Instead, Dr. Taylor and colleagues used 90-day delayed absorbable 2.0 V-Loc (Covidien) suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for patients with baseline Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) scores of at least 2 and symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

Two permanent Gore-Tex sutures were also placed at the apex of the cervix in each of the 64 patients, said Dr. Taylor, a urogynecology fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, who worked on the study as a resident at the Cleveland Clinic Akron General, in Ohio. She and her colleagues rechecked patients at postoperative weeks 2 and 6, and at months 6 and 12. They lost two patients to follow-up, both after week 2.

At baseline, 37 patients (58%) were in stage II pelvic organ prolapse, 27% were in stage III, and 14% were in stage IV. At 6 months after surgery, 85% had no detectable prolapse, 8% had stage I, and 6% had stage II. At 1 year, 82% remained in pelvic organ prolapse stage 0 and the rest were in stage I or II. All stage II patients remained asymptomatic, Dr. Taylor said.

At baseline, the median value for POP-Q point C was -3 (range, –8 to +6). At 6 months and 1 year later, the median value had improved to –8, and patients ranged between –10 and –8.

Quality of life surveys of 54 patients reflected these outcomes, Dr. Taylor said. A year after surgery, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Index (PFDI) dropped by 67 points, from 103 to 35 (P less than .0001). Likewise, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) dropped by 29 points (P less than .0001), and scores on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) indicated a significant decrease in the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual functioning (P = .008).

In addition to a single case of mesh erosion, one patient developed postoperative ileus and one experienced small bowel obstruction, both of which resolved, Dr. Taylor reported. The researchers aim to continue the study with longer follow-up intervals and detailed analyses of postoperative pain.

Dr. Taylor reported no funding sources and had no disclosures. One coauthor disclosed ties to Coloplast Corp.

DENVER – Using absorbable polydioxanone suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was associated with a mesh erosion rate of just 1.6%, according to a single-center, 1-year prospective study of 64 patients.

That is substantially less than typical erosion rates of about 5% when permanent suture is used, Danielle Taylor, DO, of Akron (Ohio ) General Medical Center said at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The researchers observed no anatomic failures or suture extrusions, and patients reported significant postoperative improvements on several validated measures of quality of life.

“Larger samples and longer follow-up may be needed,” said Dr. Taylor. “But our study suggests that permanent, nondissolving suture material may not be necessary for sacrocolpopexy.”

Sacrocolpopexy with mesh usually involves using nonabsorbable suture to attach its anterior and posterior arms to the vaginal mucosa. Instead, Dr. Taylor and colleagues used 90-day delayed absorbable 2.0 V-Loc (Covidien) suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for patients with baseline Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) scores of at least 2 and symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

Two permanent Gore-Tex sutures were also placed at the apex of the cervix in each of the 64 patients, said Dr. Taylor, a urogynecology fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, who worked on the study as a resident at the Cleveland Clinic Akron General, in Ohio. She and her colleagues rechecked patients at postoperative weeks 2 and 6, and at months 6 and 12. They lost two patients to follow-up, both after week 2.

At baseline, 37 patients (58%) were in stage II pelvic organ prolapse, 27% were in stage III, and 14% were in stage IV. At 6 months after surgery, 85% had no detectable prolapse, 8% had stage I, and 6% had stage II. At 1 year, 82% remained in pelvic organ prolapse stage 0 and the rest were in stage I or II. All stage II patients remained asymptomatic, Dr. Taylor said.

At baseline, the median value for POP-Q point C was -3 (range, –8 to +6). At 6 months and 1 year later, the median value had improved to –8, and patients ranged between –10 and –8.

Quality of life surveys of 54 patients reflected these outcomes, Dr. Taylor said. A year after surgery, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Index (PFDI) dropped by 67 points, from 103 to 35 (P less than .0001). Likewise, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) dropped by 29 points (P less than .0001), and scores on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) indicated a significant decrease in the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual functioning (P = .008).

In addition to a single case of mesh erosion, one patient developed postoperative ileus and one experienced small bowel obstruction, both of which resolved, Dr. Taylor reported. The researchers aim to continue the study with longer follow-up intervals and detailed analyses of postoperative pain.

Dr. Taylor reported no funding sources and had no disclosures. One coauthor disclosed ties to Coloplast Corp.

DENVER – Using absorbable polydioxanone suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was associated with a mesh erosion rate of just 1.6%, according to a single-center, 1-year prospective study of 64 patients.

That is substantially less than typical erosion rates of about 5% when permanent suture is used, Danielle Taylor, DO, of Akron (Ohio ) General Medical Center said at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The researchers observed no anatomic failures or suture extrusions, and patients reported significant postoperative improvements on several validated measures of quality of life.

“Larger samples and longer follow-up may be needed,” said Dr. Taylor. “But our study suggests that permanent, nondissolving suture material may not be necessary for sacrocolpopexy.”

Sacrocolpopexy with mesh usually involves using nonabsorbable suture to attach its anterior and posterior arms to the vaginal mucosa. Instead, Dr. Taylor and colleagues used 90-day delayed absorbable 2.0 V-Loc (Covidien) suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for patients with baseline Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) scores of at least 2 and symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

Two permanent Gore-Tex sutures were also placed at the apex of the cervix in each of the 64 patients, said Dr. Taylor, a urogynecology fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, who worked on the study as a resident at the Cleveland Clinic Akron General, in Ohio. She and her colleagues rechecked patients at postoperative weeks 2 and 6, and at months 6 and 12. They lost two patients to follow-up, both after week 2.

At baseline, 37 patients (58%) were in stage II pelvic organ prolapse, 27% were in stage III, and 14% were in stage IV. At 6 months after surgery, 85% had no detectable prolapse, 8% had stage I, and 6% had stage II. At 1 year, 82% remained in pelvic organ prolapse stage 0 and the rest were in stage I or II. All stage II patients remained asymptomatic, Dr. Taylor said.

At baseline, the median value for POP-Q point C was -3 (range, –8 to +6). At 6 months and 1 year later, the median value had improved to –8, and patients ranged between –10 and –8.

Quality of life surveys of 54 patients reflected these outcomes, Dr. Taylor said. A year after surgery, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Index (PFDI) dropped by 67 points, from 103 to 35 (P less than .0001). Likewise, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) dropped by 29 points (P less than .0001), and scores on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) indicated a significant decrease in the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual functioning (P = .008).

In addition to a single case of mesh erosion, one patient developed postoperative ileus and one experienced small bowel obstruction, both of which resolved, Dr. Taylor reported. The researchers aim to continue the study with longer follow-up intervals and detailed analyses of postoperative pain.

Dr. Taylor reported no funding sources and had no disclosures. One coauthor disclosed ties to Coloplast Corp.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: When 90-day delayed absorbable polydioxanone suture was used, the mesh erosion rate was 1.6%. There were no anatomic failures or cases of suture extrusion.

Data source: A single-center prospective case series of 64 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Taylor reported having no financial disclosures. One coauthor reported ties to Coloplast Corp.

How do you break the ice with patients to ask about their sexual health?

CASE Patient may benefit from treatment for dyspareuniaA 54-year-old woman has been in your care for more than 15 years. Three years ago, at her well-woman examination, she was not yet having symptoms of menopause. Now, during her current examination, she reports hot flashes, which she says are not bothersome. In passing, she also says, “I don’t want to take hormone therapy,” but then is not overly conversational or responsive to your questions. She does mention having had 3 urinary tract infections over the past 8 months. On physical examination, you note mildly atrophied vaginal tissue.

Your patient does not bring up any sexual concerns, and so far you have not directly asked about sexual health. However, the time remaining in this visit is limited, and your patient, whose daughter is sitting in the waiting area, seems anxious to finish and leave. Still, you want to broach the subject of your patient’s sexual health. What are your best options?

We learned a lot about women’s perceptions regarding their sexual health in the 2008 Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated with Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking study (PRESIDE). Approximately 43% of 31,581 questionnaire respondents reported dysfunction in sexual desire, arousal, or orgasm.1 Results also showed that 11.5% of the respondents with any of these types of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) were distressed about it. For clinicians, knowing who these women are is key in recognizing and treating FSD.

Important to the opening case, in PRESIDE, Shifren and colleagues found that women in their midlife years (aged 45 to 64) had the highest rate of any distressing sexual problem: 14.8%. Younger women (aged 18 to 44 years) had a rate of 10.8%; older women (aged 65 years or older) had a rate of 8.9%.1

The most prevalent FSD was hypoactive sexual desire disorder,1 which in 2013 was renamed sexual interest and arousal disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.2 As with any distressing FSD, reports of being distressed about low sexual desire were highest for midlife women (12.3%) relative to younger (8.9%) and older (7.4%) women.1

Unfortunately, decreased desire can have a ripple effect that goes well beyond a patient’s sexual health. A less-than-satisfying sex life can have a significant negative impact on self-image, possibly leading to depression or overall mood instability, which in turn can put undue strain on personal relationships.1,3 A patient’s entire quality of life can be affected negatively.

With so much at stake, it is important for physicians to take a more active role in addressing the sexual health of their patients. Emphasizing wellness can help reduce the stigma of sexual dysfunction, break the silence, and open up patient–physician communication.4 There is also much to be gained by helping patients realize that having positive and respectful relationships is protective for health, including sexual health.4 Likewise, patients benefit from acknowledging that sexual health is an element of overall health and contributes to it.4

Toward these ends, more discussion with patients is needed. According to a 2008 national study, although 63% of US ObGyns surveyed indicated that they routinely asked their patients about sexual activity, only 40% asked about sexual problems, and only 29% asked patients if their sex lives were satisfying.5

Without communication, information is missed, and clinicians easily can overlook their patients’ sexual dysfunction and need for intervention. For midlife women, who are disproportionately affected by dysfunction relative to younger and older women, and for whom the rate of menopausal symptoms increases over the transition years, the results of going undiagnosed and untreated can be especially troubling. As reported in one study, for example, the rate of bothersome vulvovaginal atrophy, which can be a source of sexual dysfunction, increased from less than 5% at premenopause to almost 50% at 3 years postmenopause.6 What is standing in our way, however, and how can we overcome the hurdles to an open-door approach and meaningful conversation?

Obstacles to taking a sexual historyInitiating a sexual history can be like opening Pandora’s box. How do clinicians deal with the problems that come out? Some clinicians worry about embarrassing a patient with the first few questions about sexual health. Male gynecologists may feel awkward asking a patient about sex—particularly an older, midlife patient. The problem with not starting the conversation is that the midlife patient is often the one in the most distress, and the one most in need of treatment. Only by having the sexual health discussion can clinicians identify any issues and begin to address them.

Icebreakers to jump-start the conversation

Asking open-ended questions works best. Here are some options for starting a conversation with a midlife patient:

- say, “Many women around menopause develop sexual problems. Have you noticed any changes?”

- say, “It is part of my routine to ask about sexual health. Tell me if you have any concerns.”

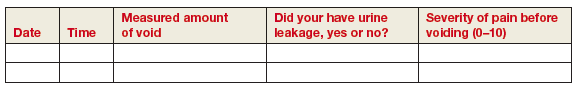

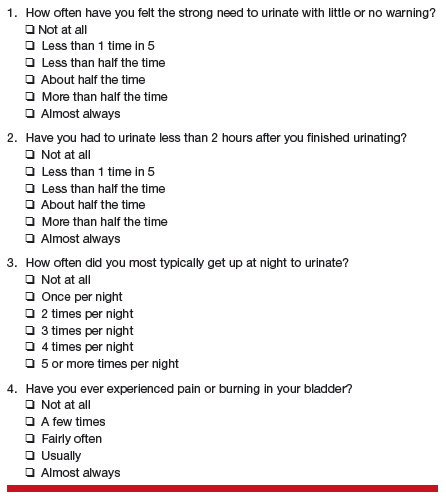

- add a brief sexual symptom checklist (FIGURE 1) to the patient history or intake form. The checklist shown here starts by asking if the patient is satisfied, yes or no, with her sexual function. If yes, the satisfied patient (and the clinician) can proceed to the next section on the form. If no, the dissatisfied patient can answer additional questions about problems related to sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and dyspareunia.

Such tools as checklists are often needed to bridge the wide communication gap between patients and physicians. Of the 255 women who reported experiencing dyspareunia in the Revealing Vaginal Effects at Midlife (REVEAL) study, almost half (44%) indicated that they had not spoken with their health care clinician about it.7 Another 44% had spoken about the problem but on their own initiative. In only 10% of cases had a physician started the conversation.

Clinicians can and should do better. Many of us have known our patients for years—given them their annual examinations, delivered their babies, performed their surgeries, become familiar with their bodies and intimate medical histories. We are uniquely qualified to start conversations on sexual health. A clinician who examines tissues and sees a decrease in vaginal caliber and pallor must say something. In some cases, the vagina is dry, but the patient has not been having lubrication problems. In other cases, a more serious condition might be involved. The important thing is to open up a conversation and talk about treatments.

CASE Continued

As today’s office visit wraps up and your patient begins moving for the door, you say, “Your hot flashes aren’t bothering you, but some women start experiencing certain sexual problems around this time in life. Have you noticed any issues?”

“Well, I have been having more burning during intercourse,” your patient responds.

On hearing this, you say, “That’s very important, Mrs. X, and I am glad you told me about it. I would like to discuss your concern a bit more, so let’s make another appointment to do just that.”

At the next visit, as part of the discussion, you give your patient a 15-minute sexual status examination.

Sexual status examination

Performing this examination helps clinicians see patterns in both sexual behavior and sexual health, which in turn can make it easier to recognize any dysfunction that might subsequently develop. The key to this process is establishing trust with the patient and having her feel comfortable with the discussion.

The patient remains fully clothed during this 15-minute session, which takes place with guarantees of nonjudgmental listening, confidentiality, privacy, and no interruptions. With the topic of sex being so personal, it should be emphasized that she is simply giving the clinician information, as she does on other health-related matters.

Establish her sexual status. Begin by asking the patient to describe her most recent or typical sexual encounter, including details such as day, time, location, type of activity, thoughts and feelings, and responses.

Potential issues can become apparent immediately. A patient may not have had a sexual encounter recently, or ever. Another may want sex, or more sex, but sees obstacles or lack of opportunity. Each of these is an issue to be explored, if the patient allows.

A patient can be sexually active in a number of ways, as the definition varies among population groups (race and age) and individuals. Sex is not only intercourse or oral sex—it is also kissing, touching, and hugging. Some people have an expansive view of what it is to be sexually active. When the patient mentions an encounter, ask what day, what time, where (at home, in a hotel room, at the office), and what type of activity (foreplay, oral sex, manual stimulation, intercourse, and position). Following up, ask what the patient was thinking or feeling about the encounter. For example, were there distracting thoughts or feelings of guilt? How did the patient and her partner respond during the encounter?

Assess for sexual dysfunction. After assessing the patient’s sexual status, turn to dysfunction. Arousal, pain, orgasm, and satisfaction are 4 areas of interest. Did the patient have difficulty becoming aroused? Was there a problem with lubrication? Did she have an orgasm? Was sex painful? How did she feel in terms of overall satisfaction?

In general, patients are comfortable speaking about sexual function and health. Having this talk can help identify a pattern, which can be discussed further during another visit. Such a follow-up would not take long—a level 3 visit should suffice.

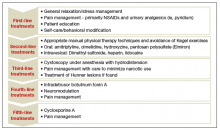

Differential diagnosis. Consider the effects of current medications.8,9 The psychiatric illnesses and general health factors that may affect sexual function should be considered as well (FIGURE 2).10–22

When is it important to refer?

There are many reasons to refer a patient to another physician, including:

- a recommended treatment is not working

- abuse is suspected

- the patient shows symptoms of depression, anxiety, or another psychiatric condition

- a chronic, generalized (vs situational) disorder may be involved

- physical pain issues must be addressed

- you simply do not feel comfortable with a particular problem or patient.

Given the range of potential issues associated with sexual function, it is important to be able to provide the patient with expert assistance from a multidisciplinary team of specialists. This team can include psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, sex educators, and, for pain issues, pelvic floor specialists and pelvic floor physical therapists. These colleagues are thoroughly familiar with the kinds of issues that can arise, and can offer alternative and adjunctive therapies.

Referrals also can be made for the latest nonpharmacologic and FDA-approved pharmacologic treatment options. Specialists tend to be familiar with these options, some of which are available only recently.

It is important to ask patients about sexual function and, if necessary, give them access to the best treatment options.

CASE Resolved

During the sexual status examination, your patient describes her most recent sexual encounter with her husband. She is frustrated with her lack of sexual response and describes a dry, tearing sensation during intercourse. You recommend first-line treatment with vaginal lubricants, preferably iso-osmolar aqueous− or silicone/dimethicone−based lubricants during intercourse. You also can discuss topical estrogen therapy via estradiol cream, conjugated equine estrogen cream, estradiol tablets in the vagina, or the estrogen ring. She is reassured that topical estrogen use will not pose significant risk for cancer, stroke, heart disease, or blood clot and that progesterone treatment is not necessary.

For patients who are particularly concerned about vaginal estrogen use, 2 or 3 times weekly use of a vaginal moisturizer could be an alternative for genitourinary symptoms and dyspareunia.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):970−978.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Leiblum SR, Koochaki PE, Rodenberg CA, Barton IP, Rosen RC. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: US results from the Women’s International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS). Menopause. 2006;13(1):46−56.

- Satcher D, Hook EW 3rd, Coleman E. Sexual health in America: improving patient care and public health. JAMA. 2015;314(8):765−766.

- Sobecki JN, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, Lindau ST. What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: results of a national survey of U.S. obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2012;9(5):1285−1294.

- Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(3):351−358.

- Shifren JL, Johannes CB, Monz BU, Russo PA, Bennett L, Rosen R. Help-seeking behavior of women with self-reported distressing sexual problems. J Womens Health. 2009;18(4):461−468.

- Basson R, Schultz WW. Sexual sequelae of general medical disorders. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):409−424.

- Kingsberg SA, Janata JW. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):497−506, v−vi.

- Casper RC, Redmond DE Jr, Katz MM, Schaffer CB, Davis JM, Koslow SH. Somatic symptoms in primary affective disorder. Presence and relationship to the classification of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(11):1098−1104.

- van Lankveld JJ, Grotjohann Y. Psychiatric comorbidity in heterosexual couples with sexual dysfunction assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29(5):479−498.

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):970−978.

- Friedman S, Harrison G. Sexual histories, attitudes, and behavior of schizophrenic and “normal” women. Arch Sex Behav. 1984;13(6):555−567.

- Okeahialam BN, Obeka NC. Sexual dysfunction in female hypertensives. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(4):638−640.

- Rees PM, Fowler CJ, Maas CP. Sexual function in men and women with neurological disorders. Lancet. 2007;369(9560):512−525.

- Bhasin S, Enzlin P, Coviello A, Basson R. Sexual dysfunction in men and women with endocrine disorders. Lancet. 2007;369(9561):597−611.

- Aslan G, KöseoTimesğlu H, Sadik O, Gimen S, Cihan A, Esen A. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(3):248−251.

- Smith EM, Ritchie JM, Galask R, Pugh EE, Jia J, Ricks-McGillan J. Case–control study of vulvar vestibulitis risk associated with genital infections. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):193−202.

- Baksu B, Davas I, Agar E, Akyol A, Varolan A. The effect of mode of delivery on postpartum sexual functioning in primiparous women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):401−406.

- Abdel-Nasser AM, Ali EI. Determinants of sexual disability and dissatisfaction in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(6):822−830.

- Sampogna F, Gisondi P, Tabolli S, Abeni D; IDI Multipurpose Psoriasis Research on Vital Experiences investigators. Impairment of sexual life in patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2007;214(2):144−150.

- Mathias C, Cardeal Mendes CM, Pondé de Sena E, et al. An open-label, fixed-dose study of bupropion effect on sexual function scores in women treated for breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(12):1792−1796.

CASE Patient may benefit from treatment for dyspareuniaA 54-year-old woman has been in your care for more than 15 years. Three years ago, at her well-woman examination, she was not yet having symptoms of menopause. Now, during her current examination, she reports hot flashes, which she says are not bothersome. In passing, she also says, “I don’t want to take hormone therapy,” but then is not overly conversational or responsive to your questions. She does mention having had 3 urinary tract infections over the past 8 months. On physical examination, you note mildly atrophied vaginal tissue.

Your patient does not bring up any sexual concerns, and so far you have not directly asked about sexual health. However, the time remaining in this visit is limited, and your patient, whose daughter is sitting in the waiting area, seems anxious to finish and leave. Still, you want to broach the subject of your patient’s sexual health. What are your best options?

We learned a lot about women’s perceptions regarding their sexual health in the 2008 Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated with Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking study (PRESIDE). Approximately 43% of 31,581 questionnaire respondents reported dysfunction in sexual desire, arousal, or orgasm.1 Results also showed that 11.5% of the respondents with any of these types of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) were distressed about it. For clinicians, knowing who these women are is key in recognizing and treating FSD.

Important to the opening case, in PRESIDE, Shifren and colleagues found that women in their midlife years (aged 45 to 64) had the highest rate of any distressing sexual problem: 14.8%. Younger women (aged 18 to 44 years) had a rate of 10.8%; older women (aged 65 years or older) had a rate of 8.9%.1

The most prevalent FSD was hypoactive sexual desire disorder,1 which in 2013 was renamed sexual interest and arousal disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.2 As with any distressing FSD, reports of being distressed about low sexual desire were highest for midlife women (12.3%) relative to younger (8.9%) and older (7.4%) women.1

Unfortunately, decreased desire can have a ripple effect that goes well beyond a patient’s sexual health. A less-than-satisfying sex life can have a significant negative impact on self-image, possibly leading to depression or overall mood instability, which in turn can put undue strain on personal relationships.1,3 A patient’s entire quality of life can be affected negatively.

With so much at stake, it is important for physicians to take a more active role in addressing the sexual health of their patients. Emphasizing wellness can help reduce the stigma of sexual dysfunction, break the silence, and open up patient–physician communication.4 There is also much to be gained by helping patients realize that having positive and respectful relationships is protective for health, including sexual health.4 Likewise, patients benefit from acknowledging that sexual health is an element of overall health and contributes to it.4

Toward these ends, more discussion with patients is needed. According to a 2008 national study, although 63% of US ObGyns surveyed indicated that they routinely asked their patients about sexual activity, only 40% asked about sexual problems, and only 29% asked patients if their sex lives were satisfying.5

Without communication, information is missed, and clinicians easily can overlook their patients’ sexual dysfunction and need for intervention. For midlife women, who are disproportionately affected by dysfunction relative to younger and older women, and for whom the rate of menopausal symptoms increases over the transition years, the results of going undiagnosed and untreated can be especially troubling. As reported in one study, for example, the rate of bothersome vulvovaginal atrophy, which can be a source of sexual dysfunction, increased from less than 5% at premenopause to almost 50% at 3 years postmenopause.6 What is standing in our way, however, and how can we overcome the hurdles to an open-door approach and meaningful conversation?

Obstacles to taking a sexual historyInitiating a sexual history can be like opening Pandora’s box. How do clinicians deal with the problems that come out? Some clinicians worry about embarrassing a patient with the first few questions about sexual health. Male gynecologists may feel awkward asking a patient about sex—particularly an older, midlife patient. The problem with not starting the conversation is that the midlife patient is often the one in the most distress, and the one most in need of treatment. Only by having the sexual health discussion can clinicians identify any issues and begin to address them.

Icebreakers to jump-start the conversation

Asking open-ended questions works best. Here are some options for starting a conversation with a midlife patient:

- say, “Many women around menopause develop sexual problems. Have you noticed any changes?”

- say, “It is part of my routine to ask about sexual health. Tell me if you have any concerns.”

- add a brief sexual symptom checklist (FIGURE 1) to the patient history or intake form. The checklist shown here starts by asking if the patient is satisfied, yes or no, with her sexual function. If yes, the satisfied patient (and the clinician) can proceed to the next section on the form. If no, the dissatisfied patient can answer additional questions about problems related to sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and dyspareunia.

Such tools as checklists are often needed to bridge the wide communication gap between patients and physicians. Of the 255 women who reported experiencing dyspareunia in the Revealing Vaginal Effects at Midlife (REVEAL) study, almost half (44%) indicated that they had not spoken with their health care clinician about it.7 Another 44% had spoken about the problem but on their own initiative. In only 10% of cases had a physician started the conversation.

Clinicians can and should do better. Many of us have known our patients for years—given them their annual examinations, delivered their babies, performed their surgeries, become familiar with their bodies and intimate medical histories. We are uniquely qualified to start conversations on sexual health. A clinician who examines tissues and sees a decrease in vaginal caliber and pallor must say something. In some cases, the vagina is dry, but the patient has not been having lubrication problems. In other cases, a more serious condition might be involved. The important thing is to open up a conversation and talk about treatments.

CASE Continued

As today’s office visit wraps up and your patient begins moving for the door, you say, “Your hot flashes aren’t bothering you, but some women start experiencing certain sexual problems around this time in life. Have you noticed any issues?”

“Well, I have been having more burning during intercourse,” your patient responds.

On hearing this, you say, “That’s very important, Mrs. X, and I am glad you told me about it. I would like to discuss your concern a bit more, so let’s make another appointment to do just that.”

At the next visit, as part of the discussion, you give your patient a 15-minute sexual status examination.

Sexual status examination

Performing this examination helps clinicians see patterns in both sexual behavior and sexual health, which in turn can make it easier to recognize any dysfunction that might subsequently develop. The key to this process is establishing trust with the patient and having her feel comfortable with the discussion.

The patient remains fully clothed during this 15-minute session, which takes place with guarantees of nonjudgmental listening, confidentiality, privacy, and no interruptions. With the topic of sex being so personal, it should be emphasized that she is simply giving the clinician information, as she does on other health-related matters.

Establish her sexual status. Begin by asking the patient to describe her most recent or typical sexual encounter, including details such as day, time, location, type of activity, thoughts and feelings, and responses.

Potential issues can become apparent immediately. A patient may not have had a sexual encounter recently, or ever. Another may want sex, or more sex, but sees obstacles or lack of opportunity. Each of these is an issue to be explored, if the patient allows.

A patient can be sexually active in a number of ways, as the definition varies among population groups (race and age) and individuals. Sex is not only intercourse or oral sex—it is also kissing, touching, and hugging. Some people have an expansive view of what it is to be sexually active. When the patient mentions an encounter, ask what day, what time, where (at home, in a hotel room, at the office), and what type of activity (foreplay, oral sex, manual stimulation, intercourse, and position). Following up, ask what the patient was thinking or feeling about the encounter. For example, were there distracting thoughts or feelings of guilt? How did the patient and her partner respond during the encounter?

Assess for sexual dysfunction. After assessing the patient’s sexual status, turn to dysfunction. Arousal, pain, orgasm, and satisfaction are 4 areas of interest. Did the patient have difficulty becoming aroused? Was there a problem with lubrication? Did she have an orgasm? Was sex painful? How did she feel in terms of overall satisfaction?

In general, patients are comfortable speaking about sexual function and health. Having this talk can help identify a pattern, which can be discussed further during another visit. Such a follow-up would not take long—a level 3 visit should suffice.

Differential diagnosis. Consider the effects of current medications.8,9 The psychiatric illnesses and general health factors that may affect sexual function should be considered as well (FIGURE 2).10–22

When is it important to refer?

There are many reasons to refer a patient to another physician, including:

- a recommended treatment is not working

- abuse is suspected

- the patient shows symptoms of depression, anxiety, or another psychiatric condition

- a chronic, generalized (vs situational) disorder may be involved

- physical pain issues must be addressed

- you simply do not feel comfortable with a particular problem or patient.

Given the range of potential issues associated with sexual function, it is important to be able to provide the patient with expert assistance from a multidisciplinary team of specialists. This team can include psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, sex educators, and, for pain issues, pelvic floor specialists and pelvic floor physical therapists. These colleagues are thoroughly familiar with the kinds of issues that can arise, and can offer alternative and adjunctive therapies.

Referrals also can be made for the latest nonpharmacologic and FDA-approved pharmacologic treatment options. Specialists tend to be familiar with these options, some of which are available only recently.

It is important to ask patients about sexual function and, if necessary, give them access to the best treatment options.

CASE Resolved

During the sexual status examination, your patient describes her most recent sexual encounter with her husband. She is frustrated with her lack of sexual response and describes a dry, tearing sensation during intercourse. You recommend first-line treatment with vaginal lubricants, preferably iso-osmolar aqueous− or silicone/dimethicone−based lubricants during intercourse. You also can discuss topical estrogen therapy via estradiol cream, conjugated equine estrogen cream, estradiol tablets in the vagina, or the estrogen ring. She is reassured that topical estrogen use will not pose significant risk for cancer, stroke, heart disease, or blood clot and that progesterone treatment is not necessary.

For patients who are particularly concerned about vaginal estrogen use, 2 or 3 times weekly use of a vaginal moisturizer could be an alternative for genitourinary symptoms and dyspareunia.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Patient may benefit from treatment for dyspareuniaA 54-year-old woman has been in your care for more than 15 years. Three years ago, at her well-woman examination, she was not yet having symptoms of menopause. Now, during her current examination, she reports hot flashes, which she says are not bothersome. In passing, she also says, “I don’t want to take hormone therapy,” but then is not overly conversational or responsive to your questions. She does mention having had 3 urinary tract infections over the past 8 months. On physical examination, you note mildly atrophied vaginal tissue.

Your patient does not bring up any sexual concerns, and so far you have not directly asked about sexual health. However, the time remaining in this visit is limited, and your patient, whose daughter is sitting in the waiting area, seems anxious to finish and leave. Still, you want to broach the subject of your patient’s sexual health. What are your best options?

We learned a lot about women’s perceptions regarding their sexual health in the 2008 Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated with Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking study (PRESIDE). Approximately 43% of 31,581 questionnaire respondents reported dysfunction in sexual desire, arousal, or orgasm.1 Results also showed that 11.5% of the respondents with any of these types of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) were distressed about it. For clinicians, knowing who these women are is key in recognizing and treating FSD.

Important to the opening case, in PRESIDE, Shifren and colleagues found that women in their midlife years (aged 45 to 64) had the highest rate of any distressing sexual problem: 14.8%. Younger women (aged 18 to 44 years) had a rate of 10.8%; older women (aged 65 years or older) had a rate of 8.9%.1

The most prevalent FSD was hypoactive sexual desire disorder,1 which in 2013 was renamed sexual interest and arousal disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.2 As with any distressing FSD, reports of being distressed about low sexual desire were highest for midlife women (12.3%) relative to younger (8.9%) and older (7.4%) women.1

Unfortunately, decreased desire can have a ripple effect that goes well beyond a patient’s sexual health. A less-than-satisfying sex life can have a significant negative impact on self-image, possibly leading to depression or overall mood instability, which in turn can put undue strain on personal relationships.1,3 A patient’s entire quality of life can be affected negatively.