User login

Guidelines in works to tackle ruptured AAA transfers

CHICAGO – Adoption of an organized, systematic approach to ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm has been inconsistent.

In a recent survey of vascular physicians in the western United States, 60% who accept ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) transfers do not have a formal protocol for treatment and 70% do not use a transfer protocol or clinical guidelines (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Aug;62:326-30).

Guidelines for the management and transfer of patients with rAAA have been developed in the United Kingdom, but no such guidelines currently exist in the United States.

To address this disparity, the Western Vascular Society used the survey results, existing European guidelines, and a literature review to develop a set of 15 best practice steps for rAAA transfer. The “guidelines” were endorsed by the society members in September 2015 and are to be published early in 2016, Dr. Matthew Mell of Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University. The guidelines identify four key components to a successful transfer: an organized inter-facility system of care including rapid triage and transport, defined clinical criteria for transfer, standard resuscitation protocols for the transport, and appropriate resources at the receiving hospital.

During transport, aim for a systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg to 90 mm Hg, establish peripheral intravenous access, and avoid aggressive fluid resuscitation, the guidelines advise. Blood products may delay the transfer.

Receiving hospitals should provide a simple and reliable method of referral and have formal protocols in place for the treatment of transferred patients.

Centers that receive patients should have endovascular aortic repair capabilities for ruptured aneurysms, including the ability to perform EVAR under local anesthesia, as well as appropriate facilities and expertise, Dr. Mell said. This advice is based mainly on outcomes observed in the IMPROVE trial (Br J Surg. 2014;101;216-24).

Successful programs tend to repair more than 20-25 ruptures per year, have on-site EVAR inventory, and, for the most part, have vascular surgeons able to perform dual open and endovascular repair. Hospital resources in these successful programs have a single phone number for transfer requests, electronic image transfer, immediately available blood products, hospital policy to accept all requests regardless of bed capacity, a contingency plan to create bed capacity after repair, and real-time management between the transfer center, bed control, and clinicians.

“This is really important because a lot of tertiary centers struggle with bed capacity if bottlenecked and a significant number [about one-third] of transfer requests are declined because of lack of capacity or dedicated room,” Dr. Mell said.

In a more recent study, nearly 20% of 4,439 patients who presented with rAAA in New York, California, and Florida were transferred for definitive care. Transfer rates rose yearly during the study period from 14% in 2005 to 22% in 2010 (J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:553-7).

“Transfer is increasingly utilized as a means for definitive care,” Dr. Mell said.

However, one in six of those transferred died without receiving treatment.

In adjusted analyses, inter-facility transfer was associated with significantly lower mortality when only patients receiving treatment were analyzed (adjusted odds ratio, 0.81; P = .02), but was actually associated with higher mortality when patients who died without treatment were also included (aOR, 1.30; P = .01).

“Outcomes after transfer can be improved by better patient selection and more efficient systems of care,” Dr. Mell concluded. “Guidelines may help; it’s too soon to know, but successful transfer programs require forethought, resources, and alignment of all stakeholders.”

Dr. Mell reported having no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Adoption of an organized, systematic approach to ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm has been inconsistent.

In a recent survey of vascular physicians in the western United States, 60% who accept ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) transfers do not have a formal protocol for treatment and 70% do not use a transfer protocol or clinical guidelines (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Aug;62:326-30).

Guidelines for the management and transfer of patients with rAAA have been developed in the United Kingdom, but no such guidelines currently exist in the United States.

To address this disparity, the Western Vascular Society used the survey results, existing European guidelines, and a literature review to develop a set of 15 best practice steps for rAAA transfer. The “guidelines” were endorsed by the society members in September 2015 and are to be published early in 2016, Dr. Matthew Mell of Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University. The guidelines identify four key components to a successful transfer: an organized inter-facility system of care including rapid triage and transport, defined clinical criteria for transfer, standard resuscitation protocols for the transport, and appropriate resources at the receiving hospital.

During transport, aim for a systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg to 90 mm Hg, establish peripheral intravenous access, and avoid aggressive fluid resuscitation, the guidelines advise. Blood products may delay the transfer.

Receiving hospitals should provide a simple and reliable method of referral and have formal protocols in place for the treatment of transferred patients.

Centers that receive patients should have endovascular aortic repair capabilities for ruptured aneurysms, including the ability to perform EVAR under local anesthesia, as well as appropriate facilities and expertise, Dr. Mell said. This advice is based mainly on outcomes observed in the IMPROVE trial (Br J Surg. 2014;101;216-24).

Successful programs tend to repair more than 20-25 ruptures per year, have on-site EVAR inventory, and, for the most part, have vascular surgeons able to perform dual open and endovascular repair. Hospital resources in these successful programs have a single phone number for transfer requests, electronic image transfer, immediately available blood products, hospital policy to accept all requests regardless of bed capacity, a contingency plan to create bed capacity after repair, and real-time management between the transfer center, bed control, and clinicians.

“This is really important because a lot of tertiary centers struggle with bed capacity if bottlenecked and a significant number [about one-third] of transfer requests are declined because of lack of capacity or dedicated room,” Dr. Mell said.

In a more recent study, nearly 20% of 4,439 patients who presented with rAAA in New York, California, and Florida were transferred for definitive care. Transfer rates rose yearly during the study period from 14% in 2005 to 22% in 2010 (J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:553-7).

“Transfer is increasingly utilized as a means for definitive care,” Dr. Mell said.

However, one in six of those transferred died without receiving treatment.

In adjusted analyses, inter-facility transfer was associated with significantly lower mortality when only patients receiving treatment were analyzed (adjusted odds ratio, 0.81; P = .02), but was actually associated with higher mortality when patients who died without treatment were also included (aOR, 1.30; P = .01).

“Outcomes after transfer can be improved by better patient selection and more efficient systems of care,” Dr. Mell concluded. “Guidelines may help; it’s too soon to know, but successful transfer programs require forethought, resources, and alignment of all stakeholders.”

Dr. Mell reported having no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Adoption of an organized, systematic approach to ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm has been inconsistent.

In a recent survey of vascular physicians in the western United States, 60% who accept ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (rAAA) transfers do not have a formal protocol for treatment and 70% do not use a transfer protocol or clinical guidelines (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Aug;62:326-30).

Guidelines for the management and transfer of patients with rAAA have been developed in the United Kingdom, but no such guidelines currently exist in the United States.

To address this disparity, the Western Vascular Society used the survey results, existing European guidelines, and a literature review to develop a set of 15 best practice steps for rAAA transfer. The “guidelines” were endorsed by the society members in September 2015 and are to be published early in 2016, Dr. Matthew Mell of Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University. The guidelines identify four key components to a successful transfer: an organized inter-facility system of care including rapid triage and transport, defined clinical criteria for transfer, standard resuscitation protocols for the transport, and appropriate resources at the receiving hospital.

During transport, aim for a systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg to 90 mm Hg, establish peripheral intravenous access, and avoid aggressive fluid resuscitation, the guidelines advise. Blood products may delay the transfer.

Receiving hospitals should provide a simple and reliable method of referral and have formal protocols in place for the treatment of transferred patients.

Centers that receive patients should have endovascular aortic repair capabilities for ruptured aneurysms, including the ability to perform EVAR under local anesthesia, as well as appropriate facilities and expertise, Dr. Mell said. This advice is based mainly on outcomes observed in the IMPROVE trial (Br J Surg. 2014;101;216-24).

Successful programs tend to repair more than 20-25 ruptures per year, have on-site EVAR inventory, and, for the most part, have vascular surgeons able to perform dual open and endovascular repair. Hospital resources in these successful programs have a single phone number for transfer requests, electronic image transfer, immediately available blood products, hospital policy to accept all requests regardless of bed capacity, a contingency plan to create bed capacity after repair, and real-time management between the transfer center, bed control, and clinicians.

“This is really important because a lot of tertiary centers struggle with bed capacity if bottlenecked and a significant number [about one-third] of transfer requests are declined because of lack of capacity or dedicated room,” Dr. Mell said.

In a more recent study, nearly 20% of 4,439 patients who presented with rAAA in New York, California, and Florida were transferred for definitive care. Transfer rates rose yearly during the study period from 14% in 2005 to 22% in 2010 (J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:553-7).

“Transfer is increasingly utilized as a means for definitive care,” Dr. Mell said.

However, one in six of those transferred died without receiving treatment.

In adjusted analyses, inter-facility transfer was associated with significantly lower mortality when only patients receiving treatment were analyzed (adjusted odds ratio, 0.81; P = .02), but was actually associated with higher mortality when patients who died without treatment were also included (aOR, 1.30; P = .01).

“Outcomes after transfer can be improved by better patient selection and more efficient systems of care,” Dr. Mell concluded. “Guidelines may help; it’s too soon to know, but successful transfer programs require forethought, resources, and alignment of all stakeholders.”

Dr. Mell reported having no conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

VIDEO: Shorter gap from heart attack to CABG shown safe

PHOENIX – Patients who are stable following a myocardial infarction and need isolated coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) don’t need to wait 5 or so days for their surgery, a delay that many surgeons and cardiologists often impose.

The operation can safely occur after just a 1- or 2-day gap following either an ST-elevation MI or a non–ST-elevation MI, based on real-world outcomes seen in more than 3,000 patients treated at any of seven U.S. medical centers.

“Waiting an arbitrary 5 days is not important,” Elizabeth L. Nichols said during a video interview and during her report at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Ms. Nichols and her associates analyzed the in-hospital mortality rates among 3,060 patients who underwent isolated CABG during 2008-2014 at any of the seven medical centers that participate in the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group and offer CABG. They included patients who had their surgery within 21 days of their MI, and excluded patients who had their CABG within 6 hours of their MI, had emergency surgery, or those with shock or incomplete data. The study group included 529 patients who had a ST-elevation MI and 2,531 patients with a non-ST-elevation MI.

The analysis divided patients into four groups based on timing of their CABG: 99 patients (3%) had surgery within the first 24 hours, 369 patients (12%) had their surgery 1-2 days after their MI, 1,966 (64%) had their operation 3-7 days following their MI, and 626 (21%) had their surgery 8-21 days after the MI.

The unadjusted mortality rates for these four subgroups were 5.1%, 1.6%, 1.6%, and 2.7%, respectively, reported Ms. Nichols, a health services researcher at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, Lebanon, N.H.

After researchers adjusted for several demographic and clinical variables, the mortality rates remained identical for patients who underwent CABG 1 or 2 days following their MI, compared with patients whose surgery was deferred until 3-7 days after the MI. Patients with surgery 8-21 days following the MI had a small but not statistically significant higher rate of in-hospital death.

Patients who had their surgery 7-23 hours following an MI had a statistically significant increased hospital mortality following surgery that ran more than threefold greater than patients who underwent CABG 3-7 days after their MI.

The main message from the analysis is that for the typical, stable MI patient who requires CABG to treat multivessel coronary disease, no need exists to wait several days following an MI to do the surgery, Ms. Nichols explained. A delay of just 1 or 2 days is safe and sufficient, as long as it provides adequate time for any acutely administered antiplatelet or antithrombotic drugs to clear.

The findings “provide a degree of comfort for not waiting the 3-5 days that had previously been thought necessary,” said Dr. Jock N. McCullough, chief of cardiac surgery at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon and a collaborator on the study.

The findings are not meant to supersede clinical judgment, both Dr. McCullough and Ms. Nichols emphasized. Individual patients might have good reasons to either undergo faster surgery or to wait at least 8 days following their MI.

“The patients who waited 8-21 days had a lot of comorbidities and were sicker patients, and their delay is often warranted” to make sure the patient is stable enough for surgery, Ms. Nichols explained. Other patients might be worsening following their MI and need to undergo their surgery within 24 hours of their MI.

“Clinical judgment is always the trump card,” Ms. Nichols said.

Ms. Nichols and Dr. McCullough had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Patients who are stable following a myocardial infarction and need isolated coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) don’t need to wait 5 or so days for their surgery, a delay that many surgeons and cardiologists often impose.

The operation can safely occur after just a 1- or 2-day gap following either an ST-elevation MI or a non–ST-elevation MI, based on real-world outcomes seen in more than 3,000 patients treated at any of seven U.S. medical centers.

“Waiting an arbitrary 5 days is not important,” Elizabeth L. Nichols said during a video interview and during her report at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Ms. Nichols and her associates analyzed the in-hospital mortality rates among 3,060 patients who underwent isolated CABG during 2008-2014 at any of the seven medical centers that participate in the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group and offer CABG. They included patients who had their surgery within 21 days of their MI, and excluded patients who had their CABG within 6 hours of their MI, had emergency surgery, or those with shock or incomplete data. The study group included 529 patients who had a ST-elevation MI and 2,531 patients with a non-ST-elevation MI.

The analysis divided patients into four groups based on timing of their CABG: 99 patients (3%) had surgery within the first 24 hours, 369 patients (12%) had their surgery 1-2 days after their MI, 1,966 (64%) had their operation 3-7 days following their MI, and 626 (21%) had their surgery 8-21 days after the MI.

The unadjusted mortality rates for these four subgroups were 5.1%, 1.6%, 1.6%, and 2.7%, respectively, reported Ms. Nichols, a health services researcher at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, Lebanon, N.H.

After researchers adjusted for several demographic and clinical variables, the mortality rates remained identical for patients who underwent CABG 1 or 2 days following their MI, compared with patients whose surgery was deferred until 3-7 days after the MI. Patients with surgery 8-21 days following the MI had a small but not statistically significant higher rate of in-hospital death.

Patients who had their surgery 7-23 hours following an MI had a statistically significant increased hospital mortality following surgery that ran more than threefold greater than patients who underwent CABG 3-7 days after their MI.

The main message from the analysis is that for the typical, stable MI patient who requires CABG to treat multivessel coronary disease, no need exists to wait several days following an MI to do the surgery, Ms. Nichols explained. A delay of just 1 or 2 days is safe and sufficient, as long as it provides adequate time for any acutely administered antiplatelet or antithrombotic drugs to clear.

The findings “provide a degree of comfort for not waiting the 3-5 days that had previously been thought necessary,” said Dr. Jock N. McCullough, chief of cardiac surgery at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon and a collaborator on the study.

The findings are not meant to supersede clinical judgment, both Dr. McCullough and Ms. Nichols emphasized. Individual patients might have good reasons to either undergo faster surgery or to wait at least 8 days following their MI.

“The patients who waited 8-21 days had a lot of comorbidities and were sicker patients, and their delay is often warranted” to make sure the patient is stable enough for surgery, Ms. Nichols explained. Other patients might be worsening following their MI and need to undergo their surgery within 24 hours of their MI.

“Clinical judgment is always the trump card,” Ms. Nichols said.

Ms. Nichols and Dr. McCullough had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Patients who are stable following a myocardial infarction and need isolated coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) don’t need to wait 5 or so days for their surgery, a delay that many surgeons and cardiologists often impose.

The operation can safely occur after just a 1- or 2-day gap following either an ST-elevation MI or a non–ST-elevation MI, based on real-world outcomes seen in more than 3,000 patients treated at any of seven U.S. medical centers.

“Waiting an arbitrary 5 days is not important,” Elizabeth L. Nichols said during a video interview and during her report at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Ms. Nichols and her associates analyzed the in-hospital mortality rates among 3,060 patients who underwent isolated CABG during 2008-2014 at any of the seven medical centers that participate in the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group and offer CABG. They included patients who had their surgery within 21 days of their MI, and excluded patients who had their CABG within 6 hours of their MI, had emergency surgery, or those with shock or incomplete data. The study group included 529 patients who had a ST-elevation MI and 2,531 patients with a non-ST-elevation MI.

The analysis divided patients into four groups based on timing of their CABG: 99 patients (3%) had surgery within the first 24 hours, 369 patients (12%) had their surgery 1-2 days after their MI, 1,966 (64%) had their operation 3-7 days following their MI, and 626 (21%) had their surgery 8-21 days after the MI.

The unadjusted mortality rates for these four subgroups were 5.1%, 1.6%, 1.6%, and 2.7%, respectively, reported Ms. Nichols, a health services researcher at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, Lebanon, N.H.

After researchers adjusted for several demographic and clinical variables, the mortality rates remained identical for patients who underwent CABG 1 or 2 days following their MI, compared with patients whose surgery was deferred until 3-7 days after the MI. Patients with surgery 8-21 days following the MI had a small but not statistically significant higher rate of in-hospital death.

Patients who had their surgery 7-23 hours following an MI had a statistically significant increased hospital mortality following surgery that ran more than threefold greater than patients who underwent CABG 3-7 days after their MI.

The main message from the analysis is that for the typical, stable MI patient who requires CABG to treat multivessel coronary disease, no need exists to wait several days following an MI to do the surgery, Ms. Nichols explained. A delay of just 1 or 2 days is safe and sufficient, as long as it provides adequate time for any acutely administered antiplatelet or antithrombotic drugs to clear.

The findings “provide a degree of comfort for not waiting the 3-5 days that had previously been thought necessary,” said Dr. Jock N. McCullough, chief of cardiac surgery at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon and a collaborator on the study.

The findings are not meant to supersede clinical judgment, both Dr. McCullough and Ms. Nichols emphasized. Individual patients might have good reasons to either undergo faster surgery or to wait at least 8 days following their MI.

“The patients who waited 8-21 days had a lot of comorbidities and were sicker patients, and their delay is often warranted” to make sure the patient is stable enough for surgery, Ms. Nichols explained. Other patients might be worsening following their MI and need to undergo their surgery within 24 hours of their MI.

“Clinical judgment is always the trump card,” Ms. Nichols said.

Ms. Nichols and Dr. McCullough had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Performing coronary artery bypass grafting 1-2 days following an MI was as safe as when surgery was delayed 3-7 days.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality after CABG was identical in patients operated on 1-2 days or 3-7 days following an MI.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 3,060 patients who underwent CABG within 21 days following an MI at any of seven U.S. centers.

Disclosures: Ms. Nichols and Dr. McCullough had no disclosures.

Pain scores point to hospital quality in colorectal surgery

Post-surgical pain scores may be an overlooked quality indicator among hospitals, according to new research linking patient-reported pain scores with institutional pain management practices and also surgical outcomes.

A retrospective cohort study of patient-reported pain scores after colorectal resections at 52 Michigan hospitals, published in Annals of Surgery (2016 Jan 7; epub ahead of print; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001541), found that patients treated at the best-performing hospitals for postoperative pain scores were more likely to have received patient-controlled analgesia, compared with those in the worst-performing ones (56.5% vs. 22.8%; P less than .001).

For their research, Dr. Scott E. Regenbogen of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues looked at patient-reported pain scores on the first morning post-surgery for 7,221 colorectal operations between 2012 and 2014. The participating hospitals were part of a statewide collaborative that collects data on surgery patients with the aim of improving quality.

Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues found that patients in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores stayed fewer days (6.5 vs. 7.9, P less than .007) and had fewer post-surgical complications (20.3% vs. 26.4%; P less than .001), compared with those in the worst-performing quartile of hospitals.

In addition, Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues found postoperative emergency department visits, readmissions, and pulmonary complications to be significantly lower in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores. The fewer pulmonary complications seen linked with better pain control “could be an indicator of better pulmonary toilet or lesser respiratory depression,” they noted.

The correlation between surgical outcomes and pain scores, the investigators wrote, suggests “consistency in the overall quality performance across both clinical and patient-reported outcomes for colectomy.”

Mean self-rated pain scores, in which patients characterize the intensity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, ranged from 4 to 6 across the hospitals in the study, with 5.1 (standard deviation 2.44) reported for the cohort as a whole. The type of surgery also affected pain scores, with minimally invasive procedures associated with lower scores, compared with open or converted procedures. The type of anesthesia used (local or epidural) also significantly affected scores.

Hospitals with better pain scores tended to be somewhat larger than those with poor scores, and performed more colorectal resections per year, the investigators found.

The researchers noted that while a previous meta-analysis showed that patient-controlled analgesia post-surgery provided superior pain control, compared with intermittent treatment (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;18:CD003348), the hospitals in this study varied widely in their approaches, with 89% of the poorly performing quartile of hospitals using intermittent parenteral narcotics, compared with 66% in the best-performing quartile.

Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues noted in their analysis that it was possible that the association between pain control and clinical outcomes such as readmissions and complications was driven by case or patient complexity differences among institutions. The 52 hospitals in the study varied in size and type, with community and academic hospitals as well as rural and urban institutions represented.

However, they wrote, it is more likely that “both pain scores and clinical outcomes reflect … global features of the quality of care in hospitals’ surgical performance. Thus, hospitals with the most streamlined, high-quality perioperative care pathways experience the best pain scores, as well as improved clinical outcomes.”

The findings, they concluded, “reveal systematic clinical care variation that could be reduced to improve patients’ experience of pain after colorectal resections.”

The researchers noted as a limitation of the study its reliance on patient-reported pain measures, and that it did not include data on patients’ pain history, opioid use prior to admission, or the administration of pre-emptive analgesia before surgery. The study was funded by the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, which receives support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. None of the study authors declared conflicts of interest.

Post-surgical pain scores may be an overlooked quality indicator among hospitals, according to new research linking patient-reported pain scores with institutional pain management practices and also surgical outcomes.

A retrospective cohort study of patient-reported pain scores after colorectal resections at 52 Michigan hospitals, published in Annals of Surgery (2016 Jan 7; epub ahead of print; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001541), found that patients treated at the best-performing hospitals for postoperative pain scores were more likely to have received patient-controlled analgesia, compared with those in the worst-performing ones (56.5% vs. 22.8%; P less than .001).

For their research, Dr. Scott E. Regenbogen of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues looked at patient-reported pain scores on the first morning post-surgery for 7,221 colorectal operations between 2012 and 2014. The participating hospitals were part of a statewide collaborative that collects data on surgery patients with the aim of improving quality.

Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues found that patients in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores stayed fewer days (6.5 vs. 7.9, P less than .007) and had fewer post-surgical complications (20.3% vs. 26.4%; P less than .001), compared with those in the worst-performing quartile of hospitals.

In addition, Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues found postoperative emergency department visits, readmissions, and pulmonary complications to be significantly lower in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores. The fewer pulmonary complications seen linked with better pain control “could be an indicator of better pulmonary toilet or lesser respiratory depression,” they noted.

The correlation between surgical outcomes and pain scores, the investigators wrote, suggests “consistency in the overall quality performance across both clinical and patient-reported outcomes for colectomy.”

Mean self-rated pain scores, in which patients characterize the intensity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, ranged from 4 to 6 across the hospitals in the study, with 5.1 (standard deviation 2.44) reported for the cohort as a whole. The type of surgery also affected pain scores, with minimally invasive procedures associated with lower scores, compared with open or converted procedures. The type of anesthesia used (local or epidural) also significantly affected scores.

Hospitals with better pain scores tended to be somewhat larger than those with poor scores, and performed more colorectal resections per year, the investigators found.

The researchers noted that while a previous meta-analysis showed that patient-controlled analgesia post-surgery provided superior pain control, compared with intermittent treatment (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;18:CD003348), the hospitals in this study varied widely in their approaches, with 89% of the poorly performing quartile of hospitals using intermittent parenteral narcotics, compared with 66% in the best-performing quartile.

Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues noted in their analysis that it was possible that the association between pain control and clinical outcomes such as readmissions and complications was driven by case or patient complexity differences among institutions. The 52 hospitals in the study varied in size and type, with community and academic hospitals as well as rural and urban institutions represented.

However, they wrote, it is more likely that “both pain scores and clinical outcomes reflect … global features of the quality of care in hospitals’ surgical performance. Thus, hospitals with the most streamlined, high-quality perioperative care pathways experience the best pain scores, as well as improved clinical outcomes.”

The findings, they concluded, “reveal systematic clinical care variation that could be reduced to improve patients’ experience of pain after colorectal resections.”

The researchers noted as a limitation of the study its reliance on patient-reported pain measures, and that it did not include data on patients’ pain history, opioid use prior to admission, or the administration of pre-emptive analgesia before surgery. The study was funded by the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, which receives support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. None of the study authors declared conflicts of interest.

Post-surgical pain scores may be an overlooked quality indicator among hospitals, according to new research linking patient-reported pain scores with institutional pain management practices and also surgical outcomes.

A retrospective cohort study of patient-reported pain scores after colorectal resections at 52 Michigan hospitals, published in Annals of Surgery (2016 Jan 7; epub ahead of print; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001541), found that patients treated at the best-performing hospitals for postoperative pain scores were more likely to have received patient-controlled analgesia, compared with those in the worst-performing ones (56.5% vs. 22.8%; P less than .001).

For their research, Dr. Scott E. Regenbogen of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues looked at patient-reported pain scores on the first morning post-surgery for 7,221 colorectal operations between 2012 and 2014. The participating hospitals were part of a statewide collaborative that collects data on surgery patients with the aim of improving quality.

Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues found that patients in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores stayed fewer days (6.5 vs. 7.9, P less than .007) and had fewer post-surgical complications (20.3% vs. 26.4%; P less than .001), compared with those in the worst-performing quartile of hospitals.

In addition, Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues found postoperative emergency department visits, readmissions, and pulmonary complications to be significantly lower in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores. The fewer pulmonary complications seen linked with better pain control “could be an indicator of better pulmonary toilet or lesser respiratory depression,” they noted.

The correlation between surgical outcomes and pain scores, the investigators wrote, suggests “consistency in the overall quality performance across both clinical and patient-reported outcomes for colectomy.”

Mean self-rated pain scores, in which patients characterize the intensity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, ranged from 4 to 6 across the hospitals in the study, with 5.1 (standard deviation 2.44) reported for the cohort as a whole. The type of surgery also affected pain scores, with minimally invasive procedures associated with lower scores, compared with open or converted procedures. The type of anesthesia used (local or epidural) also significantly affected scores.

Hospitals with better pain scores tended to be somewhat larger than those with poor scores, and performed more colorectal resections per year, the investigators found.

The researchers noted that while a previous meta-analysis showed that patient-controlled analgesia post-surgery provided superior pain control, compared with intermittent treatment (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;18:CD003348), the hospitals in this study varied widely in their approaches, with 89% of the poorly performing quartile of hospitals using intermittent parenteral narcotics, compared with 66% in the best-performing quartile.

Dr. Regenbogen and his colleagues noted in their analysis that it was possible that the association between pain control and clinical outcomes such as readmissions and complications was driven by case or patient complexity differences among institutions. The 52 hospitals in the study varied in size and type, with community and academic hospitals as well as rural and urban institutions represented.

However, they wrote, it is more likely that “both pain scores and clinical outcomes reflect … global features of the quality of care in hospitals’ surgical performance. Thus, hospitals with the most streamlined, high-quality perioperative care pathways experience the best pain scores, as well as improved clinical outcomes.”

The findings, they concluded, “reveal systematic clinical care variation that could be reduced to improve patients’ experience of pain after colorectal resections.”

The researchers noted as a limitation of the study its reliance on patient-reported pain measures, and that it did not include data on patients’ pain history, opioid use prior to admission, or the administration of pre-emptive analgesia before surgery. The study was funded by the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, which receives support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. None of the study authors declared conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Hospitals delivering better patient-reported pain control after colorectal resection also saw better surgical outcomes.

Major finding: Patients in the quartile of hospitals with the best pain scores stayed fewer days (6.5 vs. 7.9, P less than .007) and had fewer post-surgical complications (20.3% vs. 26.4%; P less than .001), compared with those in the worst-performing quartile of hospitals.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study reviewing more than 7,000 colorectal resections at 52 Michigan hospitals between 2012 and 2014.

Disclosures: The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield, sponsored the study. Investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

STS: BMI impacts risk for complications after lung resection

PHOENIX – Being underweight is associated with a substantially increased risk of complications following lung resection for cancer, results from a large database study found.

“This is not generally known among surgeons or their patients,” Dr. Trevor Williams said in an interview before the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “Studies are conflicting about the relationship of BMI [body mass index] to surgical outcomes. Most of the previous studies simply categorize BMI as overweight or not. We’ve stratified based on World Health Organization categories to get a more precise look at BMI.”

Dr. Williams, a surgeon at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and his associates evaluated 41,446 patients in the STS General Thoracic Surgery Database who underwent elective anatomic lung resection for cancer between 2009 and 2014. Their mean age was 68 years, and 53% were female. The researchers performed multivariable analysis after adjusting for validated STS risk model covariates, including gender and spirometry.

According to WHO criteria for BMI, 3% were underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2); 33.5% were normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2); 35.4% were overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2); 18.1% were obese I (30-34.9 kg/m2); 6.4% were obese II (35-39.9 kg/m2), and 3.6% were obese III (40 kg/m2 or greater). Dr. Williams and his associates observed that women were more often underweight, compared with men (4.1% vs. 1.8%, respectively; P less than .001), and underweight patients more often had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (51.7% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). Pulmonary complication rates were higher among underweight and obese III patients (P less than .001), while being underweight was also associated with higher rates of infections and any surgical complications.

Multivariable analysis revealed that pulmonary and any postoperative complications were more common among underweight patients (odds ratio, 1.44 and OR, 1.41, respectively), while any major complication was more common among obese III patients (OR, 1.18). Overweight and obese I-II patients were less likely to have any postoperative and pulmonary complications, compared with patients who had a normal BMI. “The finding of underweight patients being such a high-risk patient population is suggested in the literature but not demonstrated as clearly as in this study,” Dr. Williams said. “A truly surprising finding was that obese patients actually have a lower risk of pulmonary and overall complications than ‘normal’-BMI patients.”

He concluded that according to the current analysis, “careful risk assessment is appropriate when considering operating on underweight patients. Whether there are interventions that could be instituted to improve an individual’s risk profile has not been determined. Any preconceived notions about not operating on obese patients due to elevated risk appear to be unfounded.”

Dr. Williams reported having no financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – Being underweight is associated with a substantially increased risk of complications following lung resection for cancer, results from a large database study found.

“This is not generally known among surgeons or their patients,” Dr. Trevor Williams said in an interview before the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “Studies are conflicting about the relationship of BMI [body mass index] to surgical outcomes. Most of the previous studies simply categorize BMI as overweight or not. We’ve stratified based on World Health Organization categories to get a more precise look at BMI.”

Dr. Williams, a surgeon at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and his associates evaluated 41,446 patients in the STS General Thoracic Surgery Database who underwent elective anatomic lung resection for cancer between 2009 and 2014. Their mean age was 68 years, and 53% were female. The researchers performed multivariable analysis after adjusting for validated STS risk model covariates, including gender and spirometry.

According to WHO criteria for BMI, 3% were underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2); 33.5% were normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2); 35.4% were overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2); 18.1% were obese I (30-34.9 kg/m2); 6.4% were obese II (35-39.9 kg/m2), and 3.6% were obese III (40 kg/m2 or greater). Dr. Williams and his associates observed that women were more often underweight, compared with men (4.1% vs. 1.8%, respectively; P less than .001), and underweight patients more often had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (51.7% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). Pulmonary complication rates were higher among underweight and obese III patients (P less than .001), while being underweight was also associated with higher rates of infections and any surgical complications.

Multivariable analysis revealed that pulmonary and any postoperative complications were more common among underweight patients (odds ratio, 1.44 and OR, 1.41, respectively), while any major complication was more common among obese III patients (OR, 1.18). Overweight and obese I-II patients were less likely to have any postoperative and pulmonary complications, compared with patients who had a normal BMI. “The finding of underweight patients being such a high-risk patient population is suggested in the literature but not demonstrated as clearly as in this study,” Dr. Williams said. “A truly surprising finding was that obese patients actually have a lower risk of pulmonary and overall complications than ‘normal’-BMI patients.”

He concluded that according to the current analysis, “careful risk assessment is appropriate when considering operating on underweight patients. Whether there are interventions that could be instituted to improve an individual’s risk profile has not been determined. Any preconceived notions about not operating on obese patients due to elevated risk appear to be unfounded.”

Dr. Williams reported having no financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – Being underweight is associated with a substantially increased risk of complications following lung resection for cancer, results from a large database study found.

“This is not generally known among surgeons or their patients,” Dr. Trevor Williams said in an interview before the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “Studies are conflicting about the relationship of BMI [body mass index] to surgical outcomes. Most of the previous studies simply categorize BMI as overweight or not. We’ve stratified based on World Health Organization categories to get a more precise look at BMI.”

Dr. Williams, a surgeon at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and his associates evaluated 41,446 patients in the STS General Thoracic Surgery Database who underwent elective anatomic lung resection for cancer between 2009 and 2014. Their mean age was 68 years, and 53% were female. The researchers performed multivariable analysis after adjusting for validated STS risk model covariates, including gender and spirometry.

According to WHO criteria for BMI, 3% were underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2); 33.5% were normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2); 35.4% were overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2); 18.1% were obese I (30-34.9 kg/m2); 6.4% were obese II (35-39.9 kg/m2), and 3.6% were obese III (40 kg/m2 or greater). Dr. Williams and his associates observed that women were more often underweight, compared with men (4.1% vs. 1.8%, respectively; P less than .001), and underweight patients more often had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (51.7% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). Pulmonary complication rates were higher among underweight and obese III patients (P less than .001), while being underweight was also associated with higher rates of infections and any surgical complications.

Multivariable analysis revealed that pulmonary and any postoperative complications were more common among underweight patients (odds ratio, 1.44 and OR, 1.41, respectively), while any major complication was more common among obese III patients (OR, 1.18). Overweight and obese I-II patients were less likely to have any postoperative and pulmonary complications, compared with patients who had a normal BMI. “The finding of underweight patients being such a high-risk patient population is suggested in the literature but not demonstrated as clearly as in this study,” Dr. Williams said. “A truly surprising finding was that obese patients actually have a lower risk of pulmonary and overall complications than ‘normal’-BMI patients.”

He concluded that according to the current analysis, “careful risk assessment is appropriate when considering operating on underweight patients. Whether there are interventions that could be instituted to improve an individual’s risk profile has not been determined. Any preconceived notions about not operating on obese patients due to elevated risk appear to be unfounded.”

Dr. Williams reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Careful risk assessment is appropriate when considering performing lung resection on underweight patients.

Major finding: Multivariable analysis revealed that pulmonary and any postoperative complications were more common among underweight patients (OR, 1.44 and OR, 1.41, respectively), while any major complication was more common among obese III patients (OR, 1.18).

Data source: An analysis of 41,446 patients in the STS General Thoracic Surgery Database who underwent elective lung resection for cancer between 2009 and 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Williams reported having no financial disclosures.

STS: Score stratifies risks for isolated tricuspid valve surgery patients

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

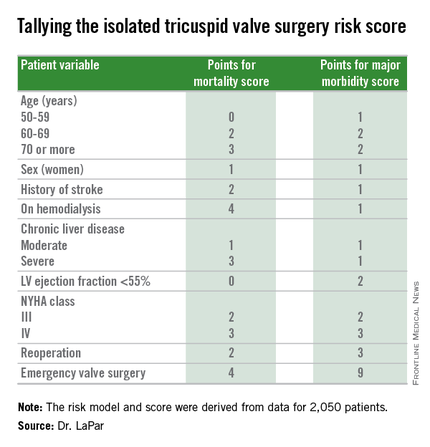

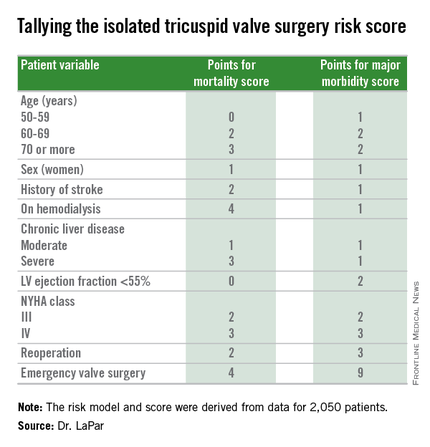

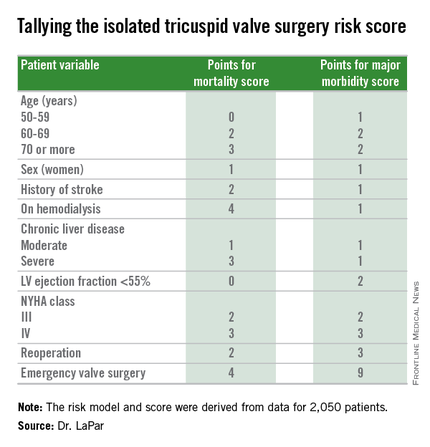

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A risk-scoring system estimates a patient’s mortality and morbidity risk when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve surgery.

Major finding: The scoring system discriminated mortality risk from 2% to 34%, and major morbidity risk from 13% to 71%.

Data source: Analysis of 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve surgery in the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

Disclosures: Dr. LaPar had no disclosures.

VIDEO: Preventing healthcare acquired infections after CT surgery

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHOENIX – More and more attention is being paid to preventing healthcare acquired infections (HAIs) in the hospital setting, and the role of HAIs in cardiothoracic surgery is a particlularly important area of focus.

“The good news is that cardiothoracic surgeons are really good at preventing infections. There’s been a lot of pressure over the past many years to report infections after cardiothoracic surgery, and so they’ve gotten a lot of things right,” Dr. Emily Landon said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“However, patients that undergo cardiothoracic surgery are still at risk of the infections that plague everyone in hospitals ... all of these are a problem based on whatever the hospital’s current situation is.”

Dr. Landon, who is the medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, discussed how cardiothroacic surgeons can maintain their own good outcomes and how they can have a postive impact outside the OR on protecting their patients after surgery.

Dr. Landon reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

STS: Hybrid thoracic suite leverages CT’s imaging sensitivity

PHOENIX – Using CT imaging to detect lung cancers in people at high risk for developing it has made it possible to find small tumors with substantially increased sensitivity than is possible with radiography, However, this approach has posed a new challenge to thoracic surgeons: How to visualize these nodules – subcentimeter and nonpalpable – for biopsy or for resection?

The answer may be the hybrid thoracic operating room developed by Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku and his associates at Toronto General Hospital, a novel surgical suite that he described at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Dr. Yasufuku and his team began using the hybrid operating room on an investigational basis in 2013 and have now done about 50 cases as part of several research protocols. The trials address the feasibility of resection, biopsy, and nodule localization, as well as whether the hybrid approach reduces the amount of radiation exposure to both patients and to the surgical team, he said. They plan to report some of their initial results later this year.

The Toronto group assembled the hybrid array of equipment into a single operating room that includes both a dual-source, dual-energy CT scanner and a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, equipment for minimally invasive procedures including video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic surgery, and advanced endoscopic technology including endobronchial ultrasound and navigational bronchoscopy. “We use innovative methods that we already know about, but bring them all together” within a single space, Dr. Yasufuku explained. “Rather than having patients go to several locations, we can do everything at the same time in one room.”

Perhaps the most novel aspect of this operating room is inclusion of a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, which uses mobile, flat CT-imaging panels that overcome the limitations of a conventional, fixed CT scanner. “They scan the patient and then we can retract them and get them out of the way” to better facilitate surgery, he said in an interview.

“We do not have a culture in thoracic surgery of using imaging during surgery,” said Dr. Yasufuku, director of the interventional thoracic surgery program at the University of Toronto. Hybrid operating rooms using noninvasive or minimally invasive equipment and procedures have become commonplace for cardiovascular surgeons and cardiac interventionalists, but this approach has generally not yet been applied to thoracic surgery for cancer, in large part because of the imaging limitations, he said. “It is difficult to perform video-assisted thorascopic surgery using fixed CT.”

Bronchoscopic technologies provide additional, important tools for minimally invasive thoracic surgery. “We use the hybrid operating room to mark small [nonpalpable] lesions.” One approach to marking is to place a microcoil within the nodule with a percutaneous needle. Another approach is to tag the nodule with a fluorescent dye using navigational bronchoscopy.

Dr. Yasufuku also emphasized that the hybrid operating room will also be valuable when new, minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic options for treatment of lung cancer become available in the near future.

Dr. Yasufuku said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Using CT imaging to detect lung cancers in people at high risk for developing it has made it possible to find small tumors with substantially increased sensitivity than is possible with radiography, However, this approach has posed a new challenge to thoracic surgeons: How to visualize these nodules – subcentimeter and nonpalpable – for biopsy or for resection?

The answer may be the hybrid thoracic operating room developed by Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku and his associates at Toronto General Hospital, a novel surgical suite that he described at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Dr. Yasufuku and his team began using the hybrid operating room on an investigational basis in 2013 and have now done about 50 cases as part of several research protocols. The trials address the feasibility of resection, biopsy, and nodule localization, as well as whether the hybrid approach reduces the amount of radiation exposure to both patients and to the surgical team, he said. They plan to report some of their initial results later this year.

The Toronto group assembled the hybrid array of equipment into a single operating room that includes both a dual-source, dual-energy CT scanner and a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, equipment for minimally invasive procedures including video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic surgery, and advanced endoscopic technology including endobronchial ultrasound and navigational bronchoscopy. “We use innovative methods that we already know about, but bring them all together” within a single space, Dr. Yasufuku explained. “Rather than having patients go to several locations, we can do everything at the same time in one room.”

Perhaps the most novel aspect of this operating room is inclusion of a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, which uses mobile, flat CT-imaging panels that overcome the limitations of a conventional, fixed CT scanner. “They scan the patient and then we can retract them and get them out of the way” to better facilitate surgery, he said in an interview.

“We do not have a culture in thoracic surgery of using imaging during surgery,” said Dr. Yasufuku, director of the interventional thoracic surgery program at the University of Toronto. Hybrid operating rooms using noninvasive or minimally invasive equipment and procedures have become commonplace for cardiovascular surgeons and cardiac interventionalists, but this approach has generally not yet been applied to thoracic surgery for cancer, in large part because of the imaging limitations, he said. “It is difficult to perform video-assisted thorascopic surgery using fixed CT.”

Bronchoscopic technologies provide additional, important tools for minimally invasive thoracic surgery. “We use the hybrid operating room to mark small [nonpalpable] lesions.” One approach to marking is to place a microcoil within the nodule with a percutaneous needle. Another approach is to tag the nodule with a fluorescent dye using navigational bronchoscopy.

Dr. Yasufuku also emphasized that the hybrid operating room will also be valuable when new, minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic options for treatment of lung cancer become available in the near future.

Dr. Yasufuku said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Using CT imaging to detect lung cancers in people at high risk for developing it has made it possible to find small tumors with substantially increased sensitivity than is possible with radiography, However, this approach has posed a new challenge to thoracic surgeons: How to visualize these nodules – subcentimeter and nonpalpable – for biopsy or for resection?

The answer may be the hybrid thoracic operating room developed by Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku and his associates at Toronto General Hospital, a novel surgical suite that he described at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Dr. Yasufuku and his team began using the hybrid operating room on an investigational basis in 2013 and have now done about 50 cases as part of several research protocols. The trials address the feasibility of resection, biopsy, and nodule localization, as well as whether the hybrid approach reduces the amount of radiation exposure to both patients and to the surgical team, he said. They plan to report some of their initial results later this year.

The Toronto group assembled the hybrid array of equipment into a single operating room that includes both a dual-source, dual-energy CT scanner and a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, equipment for minimally invasive procedures including video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic surgery, and advanced endoscopic technology including endobronchial ultrasound and navigational bronchoscopy. “We use innovative methods that we already know about, but bring them all together” within a single space, Dr. Yasufuku explained. “Rather than having patients go to several locations, we can do everything at the same time in one room.”

Perhaps the most novel aspect of this operating room is inclusion of a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, which uses mobile, flat CT-imaging panels that overcome the limitations of a conventional, fixed CT scanner. “They scan the patient and then we can retract them and get them out of the way” to better facilitate surgery, he said in an interview.

“We do not have a culture in thoracic surgery of using imaging during surgery,” said Dr. Yasufuku, director of the interventional thoracic surgery program at the University of Toronto. Hybrid operating rooms using noninvasive or minimally invasive equipment and procedures have become commonplace for cardiovascular surgeons and cardiac interventionalists, but this approach has generally not yet been applied to thoracic surgery for cancer, in large part because of the imaging limitations, he said. “It is difficult to perform video-assisted thorascopic surgery using fixed CT.”

Bronchoscopic technologies provide additional, important tools for minimally invasive thoracic surgery. “We use the hybrid operating room to mark small [nonpalpable] lesions.” One approach to marking is to place a microcoil within the nodule with a percutaneous needle. Another approach is to tag the nodule with a fluorescent dye using navigational bronchoscopy.

Dr. Yasufuku also emphasized that the hybrid operating room will also be valuable when new, minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic options for treatment of lung cancer become available in the near future.

Dr. Yasufuku said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Study: Robot-assisted hysterectomy as fast, safe as laparoscopic approach

LAS VEGAS – Robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy is just as quick and safe as standard laparoscopic hysterectomy – at least in the hands of an experienced surgeon, according to a surgical trial of 144 women.

The first prospective, randomized trial comparing the two techniques found no differences in operative time, intraoperative complications, postoperative pain, length of stay, or 12-week complications, Dr. Timothy Deimling reported at a meeting sponsored by the AAGL.

He did caution, however, that the single surgeon who performed all of the procedures was highly experienced with robotic surgery, having performed more than 600 cases in his career.

The trial included 144 women who underwent hysterectomy for benign conditions. There were 72 women in each surgical group. They were consented at the time of consult, but not randomized until the morning of surgery, said Dr. Deimling of the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, in Hershey, Pa.

There were no significant between-group differences in any of the baseline characteristics, nor in any of the indications for surgery, with one exception: More women in the laparoscopic group had undergone prior cesarean sections (44% vs. 23%).

The primary outcome was mean operative time, which was considered initial incision to closure. This was similar in the robot-assisted and laparoscopic groups (74 vs. 75 minutes).

Secondary outcomes were also similar, including pain, which was scored on a 1-10 scale. The mean score was 3.9 in the laparoscopic group and 3.8 in the robotic group. Likewise length of stay was similar (mean 19.6 vs. 22 hours).

There was one serious intraoperative complication. A patient in the laparoscopic group experienced a ureteral injury after the insertion of the first trocar, which resulted in termination of the surgery. She later had a successful laparoscopic hysterectomy. Postoperative complications were also similar in the two groups.

But it’s unclear if the results are generalizable. Dr. Deimling noted that the single surgeon who performed all the cases was highly experienced in robotic surgery. Additionally, all cases were assisted by a surgical team of nurses and technicians who were highly trained in both laparoscopic and robotic gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Deimling reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy is just as quick and safe as standard laparoscopic hysterectomy – at least in the hands of an experienced surgeon, according to a surgical trial of 144 women.

The first prospective, randomized trial comparing the two techniques found no differences in operative time, intraoperative complications, postoperative pain, length of stay, or 12-week complications, Dr. Timothy Deimling reported at a meeting sponsored by the AAGL.

He did caution, however, that the single surgeon who performed all of the procedures was highly experienced with robotic surgery, having performed more than 600 cases in his career.

The trial included 144 women who underwent hysterectomy for benign conditions. There were 72 women in each surgical group. They were consented at the time of consult, but not randomized until the morning of surgery, said Dr. Deimling of the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, in Hershey, Pa.

There were no significant between-group differences in any of the baseline characteristics, nor in any of the indications for surgery, with one exception: More women in the laparoscopic group had undergone prior cesarean sections (44% vs. 23%).

The primary outcome was mean operative time, which was considered initial incision to closure. This was similar in the robot-assisted and laparoscopic groups (74 vs. 75 minutes).

Secondary outcomes were also similar, including pain, which was scored on a 1-10 scale. The mean score was 3.9 in the laparoscopic group and 3.8 in the robotic group. Likewise length of stay was similar (mean 19.6 vs. 22 hours).