User login

VTE risk-prediction formula gains validation

AMSTERDAM – A simple formula for calculating the risk faced by acutely ill, hospitalized patients for venous thromboembolism was validated in a case-control study with more than 400 patients.

This VTE risk-calculator formula "is the first [risk-assessment model (RAM)] to be validated on a large scale in hospitalized medical patients," Charles E. Mahan, Pharm.D., said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"Applying this RAM could spare 20%-30% of these patients from getting unnecessary prophylaxis" with an anticoagulant, said Dr. Mahan, director of outcomes research at the New Mexico Heart Institute in Albuquerque.

He cautioned that the new evidence he presented still needs to be published, and a prospective test of the risk formula should also be done, but the new findings give this risk-scoring method a leg up over the several other risk-assessment methods that are out there.

"This gives us some information that we can comfortably use," Dr. Mahan said in an interview. Other formulas for estimating VTE risk in patients hospitalized for medical reasons include the Padua Prediction Score (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450-7), but the RAM tested by Dr. Mahan now "has the best evidence base for hospitalized, acutely ill patients."

The validation used the risk formula developed by the IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry in Venous Thromboembolism) study, which included more than 15,000 medical patients seen at 52 hospitals in 12 countries (Chest 2011;140:705-14).

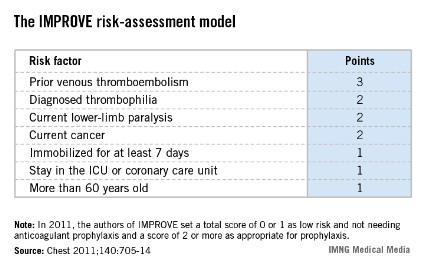

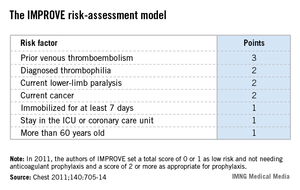

The IMPROVE RAM includes seven risk factors that each score from 1 to 3 points (see box). A history of VTE scores 3 points; immobilization for a week or more, intensive care unit stay, and age over 60 each score 1 point; and three other factors each score 2 points.

The validation cohort came from the more than 130,000 patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized for at least 3 days during 2005-2011 at a McMaster University–affiliated hospital in Hamilton, Ont. After excluding pregnancies, patients with recent surgery, and patients with VTE at the time of admission, the investigators identified 139 patients who developed VTE within 90 days of hospital admission and matched them with 278 patients who did not develop a VTE as controls. Matching was by gender, hospital, and date of admission.

The IMPROVE RAM showed "good" discrimination in the validation cohort, Dr. Mahan reported. The incidence of VTE during the 90 days following hospitalization in the validation cohort was 0.20% in patients with low scores, 0 or 1; 1.04% in patients with moderate scores, 2 or 3; and 4.15% in those with high scores, 4 or greater. By comparison, in the first IMPROVE cohort the VTE rates for 90 days were 0.45% in patients with low scores, 1.30% in those with moderate scores, and 4.74% in those with high scores.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve analysis showed that in the new cohort, the IMPROVE formula could account for about 77% of the variability in VTE incidence, performance that was also similar to that of the derivation cohort. But the formula failed to predict a VTE in several patients: 26 patients (19%) who had a VTE during follow-up had an IMPROVE score of 0 or 1 at the time of their hospitalization.

In 2011, the IMPROVE authors suggested that clinicians apply VTE prophylaxis to patients who scored 2 points or higher on the risk formula, which represented 31% of the more than 15,000 patients in the derivation cohort. In the validation cohort, 37% of the patients had a score of 2 or more. The new data suggest that a score of 3 or more may be an even better cutoff for starting VTE prophylaxis with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Mahan said, but he added that this needs more analysis.

The new data showed that a score cut-point of 2 had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 60%, whereas a cut-point of 3 had a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 78%.

"We’re still working on the cut-point. I’m sure that a score of 0 or 1 needs no prophylaxis," but deciding between 2 and 3 points will take more time, he said. "In the United States especially, we are over-prophylaxing," giving anticoagulant prophylaxis to "a large group of U.S. hospital patients who don’t need it. Some hospitals do blanket prophylaxis" for virtually all patients hospitalized for medical reasons, Dr. Mahan said.

"We want to identify patients who are not at risk so they don’t get prophylaxis."

Dr. Mahan said that he has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

[email protected] On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This research addresses quality, safety, and cost for our patients in hospital medicine. We have recognized that not all inpatients require VTE prevention, and this work offers a validated approach to assist with appropriate prophylaxis.

|

| Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig |

It will be important to see if this can be incorporated into our workflow via electronic health records. This is exactly where we need assistance to prevent one of the leading causes of death in our hospitalized patients in a cost-effective manner.

We still need to better define the risk score, but this is definitely an advance.

Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig is chair of the department of hospital medicine, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

This research addresses quality, safety, and cost for our patients in hospital medicine. We have recognized that not all inpatients require VTE prevention, and this work offers a validated approach to assist with appropriate prophylaxis.

|

| Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig |

It will be important to see if this can be incorporated into our workflow via electronic health records. This is exactly where we need assistance to prevent one of the leading causes of death in our hospitalized patients in a cost-effective manner.

We still need to better define the risk score, but this is definitely an advance.

Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig is chair of the department of hospital medicine, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

This research addresses quality, safety, and cost for our patients in hospital medicine. We have recognized that not all inpatients require VTE prevention, and this work offers a validated approach to assist with appropriate prophylaxis.

|

| Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig |

It will be important to see if this can be incorporated into our workflow via electronic health records. This is exactly where we need assistance to prevent one of the leading causes of death in our hospitalized patients in a cost-effective manner.

We still need to better define the risk score, but this is definitely an advance.

Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig is chair of the department of hospital medicine, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

AMSTERDAM – A simple formula for calculating the risk faced by acutely ill, hospitalized patients for venous thromboembolism was validated in a case-control study with more than 400 patients.

This VTE risk-calculator formula "is the first [risk-assessment model (RAM)] to be validated on a large scale in hospitalized medical patients," Charles E. Mahan, Pharm.D., said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"Applying this RAM could spare 20%-30% of these patients from getting unnecessary prophylaxis" with an anticoagulant, said Dr. Mahan, director of outcomes research at the New Mexico Heart Institute in Albuquerque.

He cautioned that the new evidence he presented still needs to be published, and a prospective test of the risk formula should also be done, but the new findings give this risk-scoring method a leg up over the several other risk-assessment methods that are out there.

"This gives us some information that we can comfortably use," Dr. Mahan said in an interview. Other formulas for estimating VTE risk in patients hospitalized for medical reasons include the Padua Prediction Score (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450-7), but the RAM tested by Dr. Mahan now "has the best evidence base for hospitalized, acutely ill patients."

The validation used the risk formula developed by the IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry in Venous Thromboembolism) study, which included more than 15,000 medical patients seen at 52 hospitals in 12 countries (Chest 2011;140:705-14).

The IMPROVE RAM includes seven risk factors that each score from 1 to 3 points (see box). A history of VTE scores 3 points; immobilization for a week or more, intensive care unit stay, and age over 60 each score 1 point; and three other factors each score 2 points.

The validation cohort came from the more than 130,000 patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized for at least 3 days during 2005-2011 at a McMaster University–affiliated hospital in Hamilton, Ont. After excluding pregnancies, patients with recent surgery, and patients with VTE at the time of admission, the investigators identified 139 patients who developed VTE within 90 days of hospital admission and matched them with 278 patients who did not develop a VTE as controls. Matching was by gender, hospital, and date of admission.

The IMPROVE RAM showed "good" discrimination in the validation cohort, Dr. Mahan reported. The incidence of VTE during the 90 days following hospitalization in the validation cohort was 0.20% in patients with low scores, 0 or 1; 1.04% in patients with moderate scores, 2 or 3; and 4.15% in those with high scores, 4 or greater. By comparison, in the first IMPROVE cohort the VTE rates for 90 days were 0.45% in patients with low scores, 1.30% in those with moderate scores, and 4.74% in those with high scores.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve analysis showed that in the new cohort, the IMPROVE formula could account for about 77% of the variability in VTE incidence, performance that was also similar to that of the derivation cohort. But the formula failed to predict a VTE in several patients: 26 patients (19%) who had a VTE during follow-up had an IMPROVE score of 0 or 1 at the time of their hospitalization.

In 2011, the IMPROVE authors suggested that clinicians apply VTE prophylaxis to patients who scored 2 points or higher on the risk formula, which represented 31% of the more than 15,000 patients in the derivation cohort. In the validation cohort, 37% of the patients had a score of 2 or more. The new data suggest that a score of 3 or more may be an even better cutoff for starting VTE prophylaxis with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Mahan said, but he added that this needs more analysis.

The new data showed that a score cut-point of 2 had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 60%, whereas a cut-point of 3 had a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 78%.

"We’re still working on the cut-point. I’m sure that a score of 0 or 1 needs no prophylaxis," but deciding between 2 and 3 points will take more time, he said. "In the United States especially, we are over-prophylaxing," giving anticoagulant prophylaxis to "a large group of U.S. hospital patients who don’t need it. Some hospitals do blanket prophylaxis" for virtually all patients hospitalized for medical reasons, Dr. Mahan said.

"We want to identify patients who are not at risk so they don’t get prophylaxis."

Dr. Mahan said that he has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

[email protected] On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – A simple formula for calculating the risk faced by acutely ill, hospitalized patients for venous thromboembolism was validated in a case-control study with more than 400 patients.

This VTE risk-calculator formula "is the first [risk-assessment model (RAM)] to be validated on a large scale in hospitalized medical patients," Charles E. Mahan, Pharm.D., said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"Applying this RAM could spare 20%-30% of these patients from getting unnecessary prophylaxis" with an anticoagulant, said Dr. Mahan, director of outcomes research at the New Mexico Heart Institute in Albuquerque.

He cautioned that the new evidence he presented still needs to be published, and a prospective test of the risk formula should also be done, but the new findings give this risk-scoring method a leg up over the several other risk-assessment methods that are out there.

"This gives us some information that we can comfortably use," Dr. Mahan said in an interview. Other formulas for estimating VTE risk in patients hospitalized for medical reasons include the Padua Prediction Score (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450-7), but the RAM tested by Dr. Mahan now "has the best evidence base for hospitalized, acutely ill patients."

The validation used the risk formula developed by the IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry in Venous Thromboembolism) study, which included more than 15,000 medical patients seen at 52 hospitals in 12 countries (Chest 2011;140:705-14).

The IMPROVE RAM includes seven risk factors that each score from 1 to 3 points (see box). A history of VTE scores 3 points; immobilization for a week or more, intensive care unit stay, and age over 60 each score 1 point; and three other factors each score 2 points.

The validation cohort came from the more than 130,000 patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized for at least 3 days during 2005-2011 at a McMaster University–affiliated hospital in Hamilton, Ont. After excluding pregnancies, patients with recent surgery, and patients with VTE at the time of admission, the investigators identified 139 patients who developed VTE within 90 days of hospital admission and matched them with 278 patients who did not develop a VTE as controls. Matching was by gender, hospital, and date of admission.

The IMPROVE RAM showed "good" discrimination in the validation cohort, Dr. Mahan reported. The incidence of VTE during the 90 days following hospitalization in the validation cohort was 0.20% in patients with low scores, 0 or 1; 1.04% in patients with moderate scores, 2 or 3; and 4.15% in those with high scores, 4 or greater. By comparison, in the first IMPROVE cohort the VTE rates for 90 days were 0.45% in patients with low scores, 1.30% in those with moderate scores, and 4.74% in those with high scores.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve analysis showed that in the new cohort, the IMPROVE formula could account for about 77% of the variability in VTE incidence, performance that was also similar to that of the derivation cohort. But the formula failed to predict a VTE in several patients: 26 patients (19%) who had a VTE during follow-up had an IMPROVE score of 0 or 1 at the time of their hospitalization.

In 2011, the IMPROVE authors suggested that clinicians apply VTE prophylaxis to patients who scored 2 points or higher on the risk formula, which represented 31% of the more than 15,000 patients in the derivation cohort. In the validation cohort, 37% of the patients had a score of 2 or more. The new data suggest that a score of 3 or more may be an even better cutoff for starting VTE prophylaxis with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Mahan said, but he added that this needs more analysis.

The new data showed that a score cut-point of 2 had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 60%, whereas a cut-point of 3 had a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 78%.

"We’re still working on the cut-point. I’m sure that a score of 0 or 1 needs no prophylaxis," but deciding between 2 and 3 points will take more time, he said. "In the United States especially, we are over-prophylaxing," giving anticoagulant prophylaxis to "a large group of U.S. hospital patients who don’t need it. Some hospitals do blanket prophylaxis" for virtually all patients hospitalized for medical reasons, Dr. Mahan said.

"We want to identify patients who are not at risk so they don’t get prophylaxis."

Dr. Mahan said that he has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

[email protected] On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE 2013 ISTH CONGRESS

Telavancin approval now includes nosocomial pneumonia indication

The lipoglycopeptide antibiotic telavancin has been approved for treating patients with hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia caused by susceptible isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, the Food and Drug Administration announced.

Telavancin, marketed as Vibativ by Theravance, "should be used for the treatment of HABP/VABP only when alternative treatments are not suitable," the FDA said in a June 21 statement announcing the approval. It is not approved to treat other bacteria that cause pneumonia, the statement pointed out. It is administered once a day.

Approval of the expanded indication was based on the safety and effectiveness of telavancin in two studies of 1,532 patients with HABP/VABP, which compared treatment with telavancin to vancomycin, according to the FDA.

In a statement, the manufacturer said that, in the two noninferiority studies, ATTAIN I and ATTAIN II, patients received either telavancin (10 mg/kg IV once a day) or vancomycin (1 g IV every 12 hours).

All-cause mortality 28 days after treatment started was comparable between the two groups, but among those patients with pre-existing kidney disease, mortality was higher for those taking telavancin – information that is now included in the boxed warning for telavancin, according to the FDA. The most common adverse effect associated with treatment in the trials was diarrhea.

Telavancin should be considered for patients with pre-existing moderate to severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or less) "only when the anticipated benefit to the patient outweighs the potential risk," according to Theravance.

Telavancin was initially approved in 2009 as a treatment for complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by susceptible isolates of Gram-positive bacteria, including both methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains of S. aureus, with a boxed warning about the fetal risks of treatment.

In a statement, the company said that telavancin would be made available to wholesalers for purchase for the pneumonia indication in the third quarter of 2013.

The lipoglycopeptide antibiotic telavancin has been approved for treating patients with hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia caused by susceptible isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, the Food and Drug Administration announced.

Telavancin, marketed as Vibativ by Theravance, "should be used for the treatment of HABP/VABP only when alternative treatments are not suitable," the FDA said in a June 21 statement announcing the approval. It is not approved to treat other bacteria that cause pneumonia, the statement pointed out. It is administered once a day.

Approval of the expanded indication was based on the safety and effectiveness of telavancin in two studies of 1,532 patients with HABP/VABP, which compared treatment with telavancin to vancomycin, according to the FDA.

In a statement, the manufacturer said that, in the two noninferiority studies, ATTAIN I and ATTAIN II, patients received either telavancin (10 mg/kg IV once a day) or vancomycin (1 g IV every 12 hours).

All-cause mortality 28 days after treatment started was comparable between the two groups, but among those patients with pre-existing kidney disease, mortality was higher for those taking telavancin – information that is now included in the boxed warning for telavancin, according to the FDA. The most common adverse effect associated with treatment in the trials was diarrhea.

Telavancin should be considered for patients with pre-existing moderate to severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or less) "only when the anticipated benefit to the patient outweighs the potential risk," according to Theravance.

Telavancin was initially approved in 2009 as a treatment for complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by susceptible isolates of Gram-positive bacteria, including both methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains of S. aureus, with a boxed warning about the fetal risks of treatment.

In a statement, the company said that telavancin would be made available to wholesalers for purchase for the pneumonia indication in the third quarter of 2013.

The lipoglycopeptide antibiotic telavancin has been approved for treating patients with hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia caused by susceptible isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, the Food and Drug Administration announced.

Telavancin, marketed as Vibativ by Theravance, "should be used for the treatment of HABP/VABP only when alternative treatments are not suitable," the FDA said in a June 21 statement announcing the approval. It is not approved to treat other bacteria that cause pneumonia, the statement pointed out. It is administered once a day.

Approval of the expanded indication was based on the safety and effectiveness of telavancin in two studies of 1,532 patients with HABP/VABP, which compared treatment with telavancin to vancomycin, according to the FDA.

In a statement, the manufacturer said that, in the two noninferiority studies, ATTAIN I and ATTAIN II, patients received either telavancin (10 mg/kg IV once a day) or vancomycin (1 g IV every 12 hours).

All-cause mortality 28 days after treatment started was comparable between the two groups, but among those patients with pre-existing kidney disease, mortality was higher for those taking telavancin – information that is now included in the boxed warning for telavancin, according to the FDA. The most common adverse effect associated with treatment in the trials was diarrhea.

Telavancin should be considered for patients with pre-existing moderate to severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or less) "only when the anticipated benefit to the patient outweighs the potential risk," according to Theravance.

Telavancin was initially approved in 2009 as a treatment for complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by susceptible isolates of Gram-positive bacteria, including both methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains of S. aureus, with a boxed warning about the fetal risks of treatment.

In a statement, the company said that telavancin would be made available to wholesalers for purchase for the pneumonia indication in the third quarter of 2013.

Current but not past smokers at extra postoperative risk

Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes following major surgery, but past smoking is not, according to a report published online June 19 in JAMA Surgery.

Current smoking correlates with these adverse outcomes even in patients who don’t have obvious smoking-related disease such cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disorders, or cancer, which suggests that smoking may exert its deleterious effects through acute or subclinical chronic vascular and respiratory pathologic mechanisms, said Dr. Khaled M. Musallam of the American University of Beirut (Lebanon) Medical Center and his associates.

Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes following major surgery, but past smoking is not, according to a recent report published in JAMA Surgery.

Since smoking cessation has clear benefits on morbidity and mortality in the surgical setting, "surgical teams should be more involved in the ongoing efforts to optimize measures for smoking control," they wrote.

"Surgery provides a teachable environment for smoking cessation. Unlike the long-term consequences of smoking, the acute consequences of smoking on patients’ postoperative outcomes can provide a strong motive for quitting," the investigators said.

Dr. Musallam and his colleagues examined the effect of smoking on surgical outcomes using data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), which includes a registry that provides feedback to participating hospitals regarding 30-day risk-adjusted surgical morbidity and mortality.

For this study, they analyzed data on 607,558 patients undergoing major surgery at more than 200 participating hospitals during a 2-year period in the United States, Canada, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates. The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 16-90 years); 43% were men and 57% were women.

A total of 125,192 patients (21%) were current smokers and 78,763 (13%) were past smokers who had quit at least 1 year before surgery. The remaining patients had never smoked.

Only current smokers showed an increased likelihood of 30-day mortality. They also were at greater risk for adverse arterial events such as MI or stroke, as well as for adverse respiratory events such as pneumonia, need for intubation, and need for a ventilator, within 30 days of surgery, the investigators said (JAMA Surg. 2013 June 19 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2360]).

The higher risk of these adverse outcomes occurred with smokers across all age groups but was particularly notable among those older than age 40 years. It was seen in both sexes, among those undergoing inpatient as well as outpatient procedures, in patients who had general as well as other types of anesthesia, across a variety of surgical subspecialties, and in both elective and emergency surgery cases.

The association between current smoking and adverse outcomes also remained robust in a sensitivity analysis, Dr. Musallam and his associates said.

There was a dose-response effect in an analysis of patients’ smoking history, with the likelihood of adverse arterial and respiratory events increasing in tandem with increasing pack-years of smoking, but even current "light" smokers who had fewer than 10 pack-years of smoking history were at increased risk for postoperative mortality and morbidity.

"These findings encourage ongoing efforts to implement smoking cessation programs," Dr. Musallam and his associates said.

"Early intervention in heavy smokers is warranted, especially because the effect of smoking on postoperative arterial and respiratory morbidity seems to be dose dependent. However, because smokers with a cigarette smoking history of less than 10 pack-years are also at risk of postoperative death, recent and light smokers should also be targeted," they suggested.

Dr. Musallam and his associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes following major surgery, but past smoking is not, according to a report published online June 19 in JAMA Surgery.

Current smoking correlates with these adverse outcomes even in patients who don’t have obvious smoking-related disease such cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disorders, or cancer, which suggests that smoking may exert its deleterious effects through acute or subclinical chronic vascular and respiratory pathologic mechanisms, said Dr. Khaled M. Musallam of the American University of Beirut (Lebanon) Medical Center and his associates.

Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes following major surgery, but past smoking is not, according to a recent report published in JAMA Surgery.

Since smoking cessation has clear benefits on morbidity and mortality in the surgical setting, "surgical teams should be more involved in the ongoing efforts to optimize measures for smoking control," they wrote.

"Surgery provides a teachable environment for smoking cessation. Unlike the long-term consequences of smoking, the acute consequences of smoking on patients’ postoperative outcomes can provide a strong motive for quitting," the investigators said.

Dr. Musallam and his colleagues examined the effect of smoking on surgical outcomes using data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), which includes a registry that provides feedback to participating hospitals regarding 30-day risk-adjusted surgical morbidity and mortality.

For this study, they analyzed data on 607,558 patients undergoing major surgery at more than 200 participating hospitals during a 2-year period in the United States, Canada, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates. The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 16-90 years); 43% were men and 57% were women.

A total of 125,192 patients (21%) were current smokers and 78,763 (13%) were past smokers who had quit at least 1 year before surgery. The remaining patients had never smoked.

Only current smokers showed an increased likelihood of 30-day mortality. They also were at greater risk for adverse arterial events such as MI or stroke, as well as for adverse respiratory events such as pneumonia, need for intubation, and need for a ventilator, within 30 days of surgery, the investigators said (JAMA Surg. 2013 June 19 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2360]).

The higher risk of these adverse outcomes occurred with smokers across all age groups but was particularly notable among those older than age 40 years. It was seen in both sexes, among those undergoing inpatient as well as outpatient procedures, in patients who had general as well as other types of anesthesia, across a variety of surgical subspecialties, and in both elective and emergency surgery cases.

The association between current smoking and adverse outcomes also remained robust in a sensitivity analysis, Dr. Musallam and his associates said.

There was a dose-response effect in an analysis of patients’ smoking history, with the likelihood of adverse arterial and respiratory events increasing in tandem with increasing pack-years of smoking, but even current "light" smokers who had fewer than 10 pack-years of smoking history were at increased risk for postoperative mortality and morbidity.

"These findings encourage ongoing efforts to implement smoking cessation programs," Dr. Musallam and his associates said.

"Early intervention in heavy smokers is warranted, especially because the effect of smoking on postoperative arterial and respiratory morbidity seems to be dose dependent. However, because smokers with a cigarette smoking history of less than 10 pack-years are also at risk of postoperative death, recent and light smokers should also be targeted," they suggested.

Dr. Musallam and his associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes following major surgery, but past smoking is not, according to a report published online June 19 in JAMA Surgery.

Current smoking correlates with these adverse outcomes even in patients who don’t have obvious smoking-related disease such cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disorders, or cancer, which suggests that smoking may exert its deleterious effects through acute or subclinical chronic vascular and respiratory pathologic mechanisms, said Dr. Khaled M. Musallam of the American University of Beirut (Lebanon) Medical Center and his associates.

Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes following major surgery, but past smoking is not, according to a recent report published in JAMA Surgery.

Since smoking cessation has clear benefits on morbidity and mortality in the surgical setting, "surgical teams should be more involved in the ongoing efforts to optimize measures for smoking control," they wrote.

"Surgery provides a teachable environment for smoking cessation. Unlike the long-term consequences of smoking, the acute consequences of smoking on patients’ postoperative outcomes can provide a strong motive for quitting," the investigators said.

Dr. Musallam and his colleagues examined the effect of smoking on surgical outcomes using data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), which includes a registry that provides feedback to participating hospitals regarding 30-day risk-adjusted surgical morbidity and mortality.

For this study, they analyzed data on 607,558 patients undergoing major surgery at more than 200 participating hospitals during a 2-year period in the United States, Canada, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates. The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 16-90 years); 43% were men and 57% were women.

A total of 125,192 patients (21%) were current smokers and 78,763 (13%) were past smokers who had quit at least 1 year before surgery. The remaining patients had never smoked.

Only current smokers showed an increased likelihood of 30-day mortality. They also were at greater risk for adverse arterial events such as MI or stroke, as well as for adverse respiratory events such as pneumonia, need for intubation, and need for a ventilator, within 30 days of surgery, the investigators said (JAMA Surg. 2013 June 19 [doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2360]).

The higher risk of these adverse outcomes occurred with smokers across all age groups but was particularly notable among those older than age 40 years. It was seen in both sexes, among those undergoing inpatient as well as outpatient procedures, in patients who had general as well as other types of anesthesia, across a variety of surgical subspecialties, and in both elective and emergency surgery cases.

The association between current smoking and adverse outcomes also remained robust in a sensitivity analysis, Dr. Musallam and his associates said.

There was a dose-response effect in an analysis of patients’ smoking history, with the likelihood of adverse arterial and respiratory events increasing in tandem with increasing pack-years of smoking, but even current "light" smokers who had fewer than 10 pack-years of smoking history were at increased risk for postoperative mortality and morbidity.

"These findings encourage ongoing efforts to implement smoking cessation programs," Dr. Musallam and his associates said.

"Early intervention in heavy smokers is warranted, especially because the effect of smoking on postoperative arterial and respiratory morbidity seems to be dose dependent. However, because smokers with a cigarette smoking history of less than 10 pack-years are also at risk of postoperative death, recent and light smokers should also be targeted," they suggested.

Dr. Musallam and his associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Major Finding: Only current smokers, not past or never smokers, showed an increased likelihood of 30-day mortality, MI, stroke, pneumonia, the need for intubation, and the need for a ventilator.

Data Source: An analysis of data on 30-day mortality and morbidity in 607,558 adults undergoing major surgery in four countries during a 2-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Musallam and his associates reported no financial conflicts of interest.

For empiric candidemia treatment, echinocandin tops fluconazole

LAS VEGAS – An echinocandin should be used for empiric therapy in critically ill candidemia patients awaiting culture results, according to investigators from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The reason is that Candida glabrata is on the rise in the critically ill, and it’s often resistant to fluconazole, the usual empiric choice, said Dr. Lisa Flynn, a vascular surgeon in the department of surgery at the university.

Dr. Flynn and her colleagues came to their conclusion after reviewing outcomes in 91 critically ill candidemia patients.

Just 40% (36) had the historic cause of candidemia, Candida albicans, which remains generally susceptible to fluconazole; 25% (23) had C. glabrata, and the rest had C. parapsilosis or other species.

Before those results were known, 53% (48) of patients were treated empirically with fluconazole and 36% (33), with the echinocandin micafungin. Most of the others received no treatment.

Seventy percent (16) of C. glabrata patients got fluconazole, the highest rate in the study of inappropriate initial antifungal therapy; probably not coincidently, 56% (13) of the C. glabrata patients died; the mortality rate in patients with other candida species was 32% (22). On univariate analysis, mortality increased from 18% to 37% if C. glabrata was cultured (P = .04).

"When we looked at glabrata versus all other candida species, we found significant increases in in-hospital mortality" that corresponded to a greater likelihood of inappropriate initial treatment, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

For that reason, "we are proposing that initial empiric antifungal therapy start with an echinocandin in the critically ill patient and then deescalate to fluconazole if [indicated by] culture data," she said.

It’s sound advice, so long as "your incidence of Candida glabrata is high," session moderator Dr. Addison May said after the presentation.

"It really depends on your hospital’s rate, and how frequently it’s [isolated]. It’s important to understand what you need to empirically treat with," but also important to use newer agents like micafungin judiciously, to prevent resistance, said Dr. May, professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

C. glabrata patients were more likely than others to be over 60 years old; they had longer hospital and ICU stays, as well.

The mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score in the study was 25, and the mean age was 57 years; 54% (49) of patients were men, and 68% (62) were black. In the previous month, almost half had surgery and a quarter had been on total parenteral nutrition.

Central lines were the source of infection in 84% (76).

On multivariate analysis, inappropriate initial antifungal treatment, vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, and end-stage renal disease were all significant risk factors for death.

Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – An echinocandin should be used for empiric therapy in critically ill candidemia patients awaiting culture results, according to investigators from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The reason is that Candida glabrata is on the rise in the critically ill, and it’s often resistant to fluconazole, the usual empiric choice, said Dr. Lisa Flynn, a vascular surgeon in the department of surgery at the university.

Dr. Flynn and her colleagues came to their conclusion after reviewing outcomes in 91 critically ill candidemia patients.

Just 40% (36) had the historic cause of candidemia, Candida albicans, which remains generally susceptible to fluconazole; 25% (23) had C. glabrata, and the rest had C. parapsilosis or other species.

Before those results were known, 53% (48) of patients were treated empirically with fluconazole and 36% (33), with the echinocandin micafungin. Most of the others received no treatment.

Seventy percent (16) of C. glabrata patients got fluconazole, the highest rate in the study of inappropriate initial antifungal therapy; probably not coincidently, 56% (13) of the C. glabrata patients died; the mortality rate in patients with other candida species was 32% (22). On univariate analysis, mortality increased from 18% to 37% if C. glabrata was cultured (P = .04).

"When we looked at glabrata versus all other candida species, we found significant increases in in-hospital mortality" that corresponded to a greater likelihood of inappropriate initial treatment, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

For that reason, "we are proposing that initial empiric antifungal therapy start with an echinocandin in the critically ill patient and then deescalate to fluconazole if [indicated by] culture data," she said.

It’s sound advice, so long as "your incidence of Candida glabrata is high," session moderator Dr. Addison May said after the presentation.

"It really depends on your hospital’s rate, and how frequently it’s [isolated]. It’s important to understand what you need to empirically treat with," but also important to use newer agents like micafungin judiciously, to prevent resistance, said Dr. May, professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

C. glabrata patients were more likely than others to be over 60 years old; they had longer hospital and ICU stays, as well.

The mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score in the study was 25, and the mean age was 57 years; 54% (49) of patients were men, and 68% (62) were black. In the previous month, almost half had surgery and a quarter had been on total parenteral nutrition.

Central lines were the source of infection in 84% (76).

On multivariate analysis, inappropriate initial antifungal treatment, vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, and end-stage renal disease were all significant risk factors for death.

Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – An echinocandin should be used for empiric therapy in critically ill candidemia patients awaiting culture results, according to investigators from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The reason is that Candida glabrata is on the rise in the critically ill, and it’s often resistant to fluconazole, the usual empiric choice, said Dr. Lisa Flynn, a vascular surgeon in the department of surgery at the university.

Dr. Flynn and her colleagues came to their conclusion after reviewing outcomes in 91 critically ill candidemia patients.

Just 40% (36) had the historic cause of candidemia, Candida albicans, which remains generally susceptible to fluconazole; 25% (23) had C. glabrata, and the rest had C. parapsilosis or other species.

Before those results were known, 53% (48) of patients were treated empirically with fluconazole and 36% (33), with the echinocandin micafungin. Most of the others received no treatment.

Seventy percent (16) of C. glabrata patients got fluconazole, the highest rate in the study of inappropriate initial antifungal therapy; probably not coincidently, 56% (13) of the C. glabrata patients died; the mortality rate in patients with other candida species was 32% (22). On univariate analysis, mortality increased from 18% to 37% if C. glabrata was cultured (P = .04).

"When we looked at glabrata versus all other candida species, we found significant increases in in-hospital mortality" that corresponded to a greater likelihood of inappropriate initial treatment, she said at the annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society.

For that reason, "we are proposing that initial empiric antifungal therapy start with an echinocandin in the critically ill patient and then deescalate to fluconazole if [indicated by] culture data," she said.

It’s sound advice, so long as "your incidence of Candida glabrata is high," session moderator Dr. Addison May said after the presentation.

"It really depends on your hospital’s rate, and how frequently it’s [isolated]. It’s important to understand what you need to empirically treat with," but also important to use newer agents like micafungin judiciously, to prevent resistance, said Dr. May, professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

C. glabrata patients were more likely than others to be over 60 years old; they had longer hospital and ICU stays, as well.

The mean APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score in the study was 25, and the mean age was 57 years; 54% (49) of patients were men, and 68% (62) were black. In the previous month, almost half had surgery and a quarter had been on total parenteral nutrition.

Central lines were the source of infection in 84% (76).

On multivariate analysis, inappropriate initial antifungal treatment, vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, and end-stage renal disease were all significant risk factors for death.

Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE SIS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Of candidemia patients, 25% had C. glabrata, which is resistant to fluconazole and is associated with in-hospital mortality.

Data Source: A retrospective study of 91 candidemia patients

Disclosures: Dr. May and Dr. Flynn said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

ACP restates call for inpatient blood glucose of 140-200 mg/dL

Blood glucose levels should be targeted to 140-200 mg/dL in surgical or medical ICU patients on insulin therapy, according to advice the American College of Physicians published online May 24 in the American Journal of Medical Quality.

Also, "clinicians should avoid targets less than ... 140 mg/dL because harms are likely to increase with lower blood glucose targets," the group said (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2013 [doi: 10.1177/1062860613489339]).

The advice isn’t new, but instead a restatement of ACP’s 2011 inpatient glycemic control guidelines reissued as part of its "Best Practice Advice" campaign, said Paul G. Shekelle, Ph.D., senior author of both the advice paper and guidelines (Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154:260-7).

"This is based on the prior guidelines, so there’s nothing new here in that sense. The Best Practice Advice series sometimes runs in parallel to the guidelines, sometimes it is something completely different than any ACP guidelines, and sometimes, like this case, it runs asynchronous to the guidelines. Ideally, these will be more synchronous in the future," Dr. Shekelle, director of the RAND Corporation’s Southern California Evidence-Based Practice Center, said in an interview.

ACP’s advice is largely in keeping with glucose control recommendations from other groups, which have tended toward liberalization in recent years amid evidence that aggressive, euglycemic control in hospitalized patients, even if they have diabetes, doesn’t improve outcomes and carries too high a risk of hypoglycemia and its attendant problems.

"Nobody is advocating tight glycemic control anymore in the hospital. It isn’t necessary and may be harmful," said Dr. Etie S. Moghissi, the lead author on a 2009 inpatient glycemic control consensus statement issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association (Diabetes Care 2009;32:1119-31).

The consensus statement recommended an upper limit of 180 mg/dL based on the pivotal NICE-SUGAR study, instead of 200 mg/dL, which Dr. Shekelle said ACP chose because it was the upper target limit in several of the additional studies upon which the group based its 2011 guidelines (N. Engl. .J Med. 2009;360:1283-97).

But Dr. Moghissi, who is with the department of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said she’s concerned that 200 mg/dL might be too high.

"We know that when we set targets, people do not achieve them. So when we set a higher target, most of the time people go above that. The concern" is that a target of 200 mg/dL "may be perceived [as meaning that] a little bit over 200 mg/dL is okay," but "above 200 mg/dL, usually there are issues with increased risk of infection, poor wound healing, volume depletion," and other problems, she said in an interview.

Dr. Shekelle and Dr. Moghissi said they have no relevant disclosures.

Although interesting that this best practice advice comes more than 2 years after the ACP guidelines, it is still relevant, especially to hospitalists working in open ICUs.

At this point, everyone agrees that intensive insulin therapy leads to increased risk of hypoglycemia, which may lead to worse outcomes. However, in the extensively quoted NICE-SUGAR study, the mean glucose level achieved in the conventional group was 144mg/dL, far below from the 200mg/dL upper limit set by the ACP. There are insufficient and inconclusive studies on the wards, and thus, target ranges and recommendations for the wards are cautionary extrapolations from ICU studies.

|

| Dr. Pejvak Salehi |

It is important to note that the ADA/ACE, SHM and ACC/AHA all agree with the lower target capillary blood glucose of 140mg/dL on the wards and ICU.

Interestingly, all other entities recommend an upper target of 180mg/dL. In addition, the Surgical Care Improvement Project CMS Core Measure for postoperative day 1 and 2:00-6:00 a.m. CBG for cardiac surgery patients is currently set at 200mg/dL. I would caution hospitals with setting upper limits at 200mg/dL in the CCU. Until this core measure has changed, hospitals may see their SCIP measures worsening.

Dr. Pejvak Salehi is with the department of medicine, Portland, Ore., Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He has worked in glycemic management for several years.

Although interesting that this best practice advice comes more than 2 years after the ACP guidelines, it is still relevant, especially to hospitalists working in open ICUs.

At this point, everyone agrees that intensive insulin therapy leads to increased risk of hypoglycemia, which may lead to worse outcomes. However, in the extensively quoted NICE-SUGAR study, the mean glucose level achieved in the conventional group was 144mg/dL, far below from the 200mg/dL upper limit set by the ACP. There are insufficient and inconclusive studies on the wards, and thus, target ranges and recommendations for the wards are cautionary extrapolations from ICU studies.

|

| Dr. Pejvak Salehi |

It is important to note that the ADA/ACE, SHM and ACC/AHA all agree with the lower target capillary blood glucose of 140mg/dL on the wards and ICU.

Interestingly, all other entities recommend an upper target of 180mg/dL. In addition, the Surgical Care Improvement Project CMS Core Measure for postoperative day 1 and 2:00-6:00 a.m. CBG for cardiac surgery patients is currently set at 200mg/dL. I would caution hospitals with setting upper limits at 200mg/dL in the CCU. Until this core measure has changed, hospitals may see their SCIP measures worsening.

Dr. Pejvak Salehi is with the department of medicine, Portland, Ore., Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He has worked in glycemic management for several years.

Although interesting that this best practice advice comes more than 2 years after the ACP guidelines, it is still relevant, especially to hospitalists working in open ICUs.

At this point, everyone agrees that intensive insulin therapy leads to increased risk of hypoglycemia, which may lead to worse outcomes. However, in the extensively quoted NICE-SUGAR study, the mean glucose level achieved in the conventional group was 144mg/dL, far below from the 200mg/dL upper limit set by the ACP. There are insufficient and inconclusive studies on the wards, and thus, target ranges and recommendations for the wards are cautionary extrapolations from ICU studies.

|

| Dr. Pejvak Salehi |

It is important to note that the ADA/ACE, SHM and ACC/AHA all agree with the lower target capillary blood glucose of 140mg/dL on the wards and ICU.

Interestingly, all other entities recommend an upper target of 180mg/dL. In addition, the Surgical Care Improvement Project CMS Core Measure for postoperative day 1 and 2:00-6:00 a.m. CBG for cardiac surgery patients is currently set at 200mg/dL. I would caution hospitals with setting upper limits at 200mg/dL in the CCU. Until this core measure has changed, hospitals may see their SCIP measures worsening.

Dr. Pejvak Salehi is with the department of medicine, Portland, Ore., Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He has worked in glycemic management for several years.

Blood glucose levels should be targeted to 140-200 mg/dL in surgical or medical ICU patients on insulin therapy, according to advice the American College of Physicians published online May 24 in the American Journal of Medical Quality.

Also, "clinicians should avoid targets less than ... 140 mg/dL because harms are likely to increase with lower blood glucose targets," the group said (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2013 [doi: 10.1177/1062860613489339]).

The advice isn’t new, but instead a restatement of ACP’s 2011 inpatient glycemic control guidelines reissued as part of its "Best Practice Advice" campaign, said Paul G. Shekelle, Ph.D., senior author of both the advice paper and guidelines (Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154:260-7).

"This is based on the prior guidelines, so there’s nothing new here in that sense. The Best Practice Advice series sometimes runs in parallel to the guidelines, sometimes it is something completely different than any ACP guidelines, and sometimes, like this case, it runs asynchronous to the guidelines. Ideally, these will be more synchronous in the future," Dr. Shekelle, director of the RAND Corporation’s Southern California Evidence-Based Practice Center, said in an interview.

ACP’s advice is largely in keeping with glucose control recommendations from other groups, which have tended toward liberalization in recent years amid evidence that aggressive, euglycemic control in hospitalized patients, even if they have diabetes, doesn’t improve outcomes and carries too high a risk of hypoglycemia and its attendant problems.

"Nobody is advocating tight glycemic control anymore in the hospital. It isn’t necessary and may be harmful," said Dr. Etie S. Moghissi, the lead author on a 2009 inpatient glycemic control consensus statement issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association (Diabetes Care 2009;32:1119-31).

The consensus statement recommended an upper limit of 180 mg/dL based on the pivotal NICE-SUGAR study, instead of 200 mg/dL, which Dr. Shekelle said ACP chose because it was the upper target limit in several of the additional studies upon which the group based its 2011 guidelines (N. Engl. .J Med. 2009;360:1283-97).

But Dr. Moghissi, who is with the department of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said she’s concerned that 200 mg/dL might be too high.

"We know that when we set targets, people do not achieve them. So when we set a higher target, most of the time people go above that. The concern" is that a target of 200 mg/dL "may be perceived [as meaning that] a little bit over 200 mg/dL is okay," but "above 200 mg/dL, usually there are issues with increased risk of infection, poor wound healing, volume depletion," and other problems, she said in an interview.

Dr. Shekelle and Dr. Moghissi said they have no relevant disclosures.

Blood glucose levels should be targeted to 140-200 mg/dL in surgical or medical ICU patients on insulin therapy, according to advice the American College of Physicians published online May 24 in the American Journal of Medical Quality.

Also, "clinicians should avoid targets less than ... 140 mg/dL because harms are likely to increase with lower blood glucose targets," the group said (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2013 [doi: 10.1177/1062860613489339]).

The advice isn’t new, but instead a restatement of ACP’s 2011 inpatient glycemic control guidelines reissued as part of its "Best Practice Advice" campaign, said Paul G. Shekelle, Ph.D., senior author of both the advice paper and guidelines (Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154:260-7).

"This is based on the prior guidelines, so there’s nothing new here in that sense. The Best Practice Advice series sometimes runs in parallel to the guidelines, sometimes it is something completely different than any ACP guidelines, and sometimes, like this case, it runs asynchronous to the guidelines. Ideally, these will be more synchronous in the future," Dr. Shekelle, director of the RAND Corporation’s Southern California Evidence-Based Practice Center, said in an interview.

ACP’s advice is largely in keeping with glucose control recommendations from other groups, which have tended toward liberalization in recent years amid evidence that aggressive, euglycemic control in hospitalized patients, even if they have diabetes, doesn’t improve outcomes and carries too high a risk of hypoglycemia and its attendant problems.

"Nobody is advocating tight glycemic control anymore in the hospital. It isn’t necessary and may be harmful," said Dr. Etie S. Moghissi, the lead author on a 2009 inpatient glycemic control consensus statement issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association (Diabetes Care 2009;32:1119-31).

The consensus statement recommended an upper limit of 180 mg/dL based on the pivotal NICE-SUGAR study, instead of 200 mg/dL, which Dr. Shekelle said ACP chose because it was the upper target limit in several of the additional studies upon which the group based its 2011 guidelines (N. Engl. .J Med. 2009;360:1283-97).

But Dr. Moghissi, who is with the department of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said she’s concerned that 200 mg/dL might be too high.

"We know that when we set targets, people do not achieve them. So when we set a higher target, most of the time people go above that. The concern" is that a target of 200 mg/dL "may be perceived [as meaning that] a little bit over 200 mg/dL is okay," but "above 200 mg/dL, usually there are issues with increased risk of infection, poor wound healing, volume depletion," and other problems, she said in an interview.

Dr. Shekelle and Dr. Moghissi said they have no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL QUALITY

Aspirin better than heparin at VTE prevention after total hip arthroplasty

Aspirin is an effective, safe, convenient, and inexpensive alternative to low-molecular-weight heparin for extended thromboprophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty, according to a report published online June 3 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In a multicenter randomized trial involving 786 patients undergoing elective total hip replacement in Canada during a 3-year period, 28 days of oral aspirin prophylaxis was noninferior to and as safe as 28 days of subcutaneous dalteparin injections for preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to Dr. David R. Anderson, who is professor of medicine, pathology, and community health and epidemiology of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and his associates in the EPCAT (Extended Prophylaxis Comparing Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin to Aspirin in Total Hip Arthroplasty) study.

During this trial, the novel oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban was approved for this indication in Canada, which prompted "a major shift" away from using dalteparin and toward using the new drug in clinical practice. In light of this development, it will be important to "evaluate the benefits and risks of aspirin as extended prophylaxis after [total hip replacement], compared with the new oral anticoagulant agents," noted the EPCAT investigators.

Their findings on the benefits of aspirin also indicate that its role for venous thromboprophylaxis in other settings should now be reconsidered as well, Dr. Anderson and his colleagues added.

In the EPCAT study, patients underwent elective unilateral total hip replacement at 12 university-affiliated tertiary medical centers and received thromboprophylaxis in the form of subcutaneous injections of dalteparin for 10 days. They were randomly assigned to continue receiving dalteparin injections and take placebo oral aspirin tablets (400 patients) or to receive placebo injections and begin taking oral aspirin (81 mg) every day for 28 days (386 patients).

The demographic, medical, and surgical characteristics of the two study groups were comparable. Patients, physicians, study coordinators, and members of the health care teams all were blinded to study assignment.

The introduction of rivaroxaban during the course of the study severely affected ongoing recruitment of subjects, because both patients and orthopedic surgeons became increasingly reluctant to participate in a study requiring daily injections for 38 days when a new oral agent was available. The EPCAT study was terminated early when completion of the intended enrollment appeared "unfeasible" and an interim analysis showed that the primary objective – establishing the noninferiority of aspirin – had been reached.

The primary efficacy outcome was the development of symptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), confirmed by objective testing, during the 90 days after randomization. This outcome occurred in only 0.3% of the aspirin group, compared with 1.3% of the dalteparin group, establishing the noninferiority of aspirin therapy.

There was a single case of proximal DVT in the aspirin group, compared with two cases of proximal DVT and three of PE in the dalteparin group. Another patient in the dalteparin group developed a symptomatic distal DVT in her calf, "but this was not considered an outcome event," the investigators said.

No major bleeding events developed in the aspirin group, but there was one such event in the dalteparin group for an overall rate of 0.3%. Similarly, there were two clinically significant nonmajor bleeding events for aspirin (0.5% rate), compared with four for dalteparin (1.0% rate). And there were eight minor bleeding events for aspirin (2.1% rate), compared with 18 for dalteparin (4.5% rate).

"In a composite analysis of net clinical benefit that combined VTE and clinically relevant major and nonmajor bleeding complications as outcomes," 0.8% of patients receiving aspirin had complications, compared with 2.5% of patients receiving dalteparin.

There were no differences between the two study groups in secondary outcomes such as wound infections, arterial vascular events, MI, stroke, or deaths.

The EPCAT trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Aspirin was provided by Bayer HealthCare and dalteparin by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, but neither Bayer nor Pfizer was involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study.

Aspirin is an effective, safe, convenient, and inexpensive alternative to low-molecular-weight heparin for extended thromboprophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty, according to a report published online June 3 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In a multicenter randomized trial involving 786 patients undergoing elective total hip replacement in Canada during a 3-year period, 28 days of oral aspirin prophylaxis was noninferior to and as safe as 28 days of subcutaneous dalteparin injections for preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to Dr. David R. Anderson, who is professor of medicine, pathology, and community health and epidemiology of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and his associates in the EPCAT (Extended Prophylaxis Comparing Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin to Aspirin in Total Hip Arthroplasty) study.

During this trial, the novel oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban was approved for this indication in Canada, which prompted "a major shift" away from using dalteparin and toward using the new drug in clinical practice. In light of this development, it will be important to "evaluate the benefits and risks of aspirin as extended prophylaxis after [total hip replacement], compared with the new oral anticoagulant agents," noted the EPCAT investigators.

Their findings on the benefits of aspirin also indicate that its role for venous thromboprophylaxis in other settings should now be reconsidered as well, Dr. Anderson and his colleagues added.

In the EPCAT study, patients underwent elective unilateral total hip replacement at 12 university-affiliated tertiary medical centers and received thromboprophylaxis in the form of subcutaneous injections of dalteparin for 10 days. They were randomly assigned to continue receiving dalteparin injections and take placebo oral aspirin tablets (400 patients) or to receive placebo injections and begin taking oral aspirin (81 mg) every day for 28 days (386 patients).

The demographic, medical, and surgical characteristics of the two study groups were comparable. Patients, physicians, study coordinators, and members of the health care teams all were blinded to study assignment.

The introduction of rivaroxaban during the course of the study severely affected ongoing recruitment of subjects, because both patients and orthopedic surgeons became increasingly reluctant to participate in a study requiring daily injections for 38 days when a new oral agent was available. The EPCAT study was terminated early when completion of the intended enrollment appeared "unfeasible" and an interim analysis showed that the primary objective – establishing the noninferiority of aspirin – had been reached.

The primary efficacy outcome was the development of symptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), confirmed by objective testing, during the 90 days after randomization. This outcome occurred in only 0.3% of the aspirin group, compared with 1.3% of the dalteparin group, establishing the noninferiority of aspirin therapy.

There was a single case of proximal DVT in the aspirin group, compared with two cases of proximal DVT and three of PE in the dalteparin group. Another patient in the dalteparin group developed a symptomatic distal DVT in her calf, "but this was not considered an outcome event," the investigators said.

No major bleeding events developed in the aspirin group, but there was one such event in the dalteparin group for an overall rate of 0.3%. Similarly, there were two clinically significant nonmajor bleeding events for aspirin (0.5% rate), compared with four for dalteparin (1.0% rate). And there were eight minor bleeding events for aspirin (2.1% rate), compared with 18 for dalteparin (4.5% rate).

"In a composite analysis of net clinical benefit that combined VTE and clinically relevant major and nonmajor bleeding complications as outcomes," 0.8% of patients receiving aspirin had complications, compared with 2.5% of patients receiving dalteparin.

There were no differences between the two study groups in secondary outcomes such as wound infections, arterial vascular events, MI, stroke, or deaths.

The EPCAT trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Aspirin was provided by Bayer HealthCare and dalteparin by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, but neither Bayer nor Pfizer was involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study.

Aspirin is an effective, safe, convenient, and inexpensive alternative to low-molecular-weight heparin for extended thromboprophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty, according to a report published online June 3 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In a multicenter randomized trial involving 786 patients undergoing elective total hip replacement in Canada during a 3-year period, 28 days of oral aspirin prophylaxis was noninferior to and as safe as 28 days of subcutaneous dalteparin injections for preventing venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to Dr. David R. Anderson, who is professor of medicine, pathology, and community health and epidemiology of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and his associates in the EPCAT (Extended Prophylaxis Comparing Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin to Aspirin in Total Hip Arthroplasty) study.

During this trial, the novel oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban was approved for this indication in Canada, which prompted "a major shift" away from using dalteparin and toward using the new drug in clinical practice. In light of this development, it will be important to "evaluate the benefits and risks of aspirin as extended prophylaxis after [total hip replacement], compared with the new oral anticoagulant agents," noted the EPCAT investigators.

Their findings on the benefits of aspirin also indicate that its role for venous thromboprophylaxis in other settings should now be reconsidered as well, Dr. Anderson and his colleagues added.

In the EPCAT study, patients underwent elective unilateral total hip replacement at 12 university-affiliated tertiary medical centers and received thromboprophylaxis in the form of subcutaneous injections of dalteparin for 10 days. They were randomly assigned to continue receiving dalteparin injections and take placebo oral aspirin tablets (400 patients) or to receive placebo injections and begin taking oral aspirin (81 mg) every day for 28 days (386 patients).

The demographic, medical, and surgical characteristics of the two study groups were comparable. Patients, physicians, study coordinators, and members of the health care teams all were blinded to study assignment.

The introduction of rivaroxaban during the course of the study severely affected ongoing recruitment of subjects, because both patients and orthopedic surgeons became increasingly reluctant to participate in a study requiring daily injections for 38 days when a new oral agent was available. The EPCAT study was terminated early when completion of the intended enrollment appeared "unfeasible" and an interim analysis showed that the primary objective – establishing the noninferiority of aspirin – had been reached.

The primary efficacy outcome was the development of symptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), confirmed by objective testing, during the 90 days after randomization. This outcome occurred in only 0.3% of the aspirin group, compared with 1.3% of the dalteparin group, establishing the noninferiority of aspirin therapy.

There was a single case of proximal DVT in the aspirin group, compared with two cases of proximal DVT and three of PE in the dalteparin group. Another patient in the dalteparin group developed a symptomatic distal DVT in her calf, "but this was not considered an outcome event," the investigators said.

No major bleeding events developed in the aspirin group, but there was one such event in the dalteparin group for an overall rate of 0.3%. Similarly, there were two clinically significant nonmajor bleeding events for aspirin (0.5% rate), compared with four for dalteparin (1.0% rate). And there were eight minor bleeding events for aspirin (2.1% rate), compared with 18 for dalteparin (4.5% rate).

"In a composite analysis of net clinical benefit that combined VTE and clinically relevant major and nonmajor bleeding complications as outcomes," 0.8% of patients receiving aspirin had complications, compared with 2.5% of patients receiving dalteparin.

There were no differences between the two study groups in secondary outcomes such as wound infections, arterial vascular events, MI, stroke, or deaths.

The EPCAT trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Aspirin was provided by Bayer HealthCare and dalteparin by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, but neither Bayer nor Pfizer was involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Major finding: The primary efficacy outcome – development of symptomatic proximal DVT or PE during the 90 days after total hip arthroplasty – occurred in only 0.3% of the aspirin group, compared with 1.3% of the dalteparin group, establishing the noninferiority of aspirin therapy.

Data source: A randomized multicenter double-blind trial comparing the effectiveness and safety of aspirin and dalteparin for thromboprophylaxis in 786 patients undergoing elective total hip replacement in Canada during a 3-year period.

Disclosures: The EPCAT trial was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Aspirin was provided by Bayer HealthCare and dalteparin by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, but neither Bayer nor Pfizer was involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study.

Mechanical bowel prep may up cancer-specific survival after CRC resection

PHOENIX – Improving cancer-specific survival after resection for colorectal cancer may be as simple as ordering preoperative mechanical bowel preparation, according to an analysis of data from a randomized trial conducted in Sweden and Germany.

Roughly half of the 841 patients studied had such preparation before their operation. The actuarial 5-year rate of cancer-specific survival was about 8% higher in this group, first author Dr. Åsa Collin of Uppsala University reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

An analysis of cancer stage at the time of surgery suggested that the two groups were well matched on this measure. Preparation did not significantly decrease the rate of recurrence or increase the rate of overall survival.

Session attendee Dr. J. Daniel Stanley of University Surgical Associates in Chattanooga, Tenn., questioned whether the patients might have differed on other factors that influenced whether they underwent mechanical bowel preparation.

"Were some of them obstructed, which might indicate a different tumor biology than was reflected in the staging?" he asked.

"These were all elective surgeries, and there was no patient who we actually decided that they shouldn’t have preparation," Dr. Collin replied.

In an interview, session comoderator Dr. David Maron, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla., said, "What was interesting was that they didn’t show a significant difference in cancer recurrence, although it was close to significance. So the question remains, is it in fact the mechanical bowel prep, or could there be differences in the postoperative follow-up and even the postoperative treatment of those patients who developed recurrence?"

Guidelines leave preparation up to the treating surgeon, and several studies have found no benefit at least in the short term, he noted. "This is one of the first studies that have shown that perhaps from a long-term standpoint in patients with cancer, that there may be some benefit to preoperative preparation of the bowel, although again, it’s preliminary and there’s a lot of unknowns out there."

Dr. Collin and her colleagues analyzed data from a trial among patients who underwent an elective resection for cancer, adenoma, or diverticular disease of the colon at 21 hospitals in Sweden and Germany between 1999 and 2005.

Earlier results for the entire trial population, previously reported, showed no significant reduction in 30-day rates of complications with mechanical bowel preparation (Br. J. Surg. 2007;94:689-95).

The new, long-term results for just the 841 patients with colorectal cancer – 53% of whom had a mechanical bowel preparation before their surgery – indicated those undergoing this preparation had a higher actuarial 5-year rate of cancer-specific survival (90% vs. 82%; P = .03).

The two groups were similar in terms of the 5-year rate of recurrence (80% vs. 89%, P = .08) and overall survival, Dr. Collin said.

"We looked at tumor stage to see if the explanation for patients having no mechanical bowel preparation having poorer cancer-specific survival was that they had more advanced tumors, and there was no difference in the stages" between groups, she said, with the majority of patients in both groups having stage II or III disease.

Dr. Collin disclosed no conflicts of interest related to the research.

PHOENIX – Improving cancer-specific survival after resection for colorectal cancer may be as simple as ordering preoperative mechanical bowel preparation, according to an analysis of data from a randomized trial conducted in Sweden and Germany.

Roughly half of the 841 patients studied had such preparation before their operation. The actuarial 5-year rate of cancer-specific survival was about 8% higher in this group, first author Dr. Åsa Collin of Uppsala University reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

An analysis of cancer stage at the time of surgery suggested that the two groups were well matched on this measure. Preparation did not significantly decrease the rate of recurrence or increase the rate of overall survival.

Session attendee Dr. J. Daniel Stanley of University Surgical Associates in Chattanooga, Tenn., questioned whether the patients might have differed on other factors that influenced whether they underwent mechanical bowel preparation.

"Were some of them obstructed, which might indicate a different tumor biology than was reflected in the staging?" he asked.

"These were all elective surgeries, and there was no patient who we actually decided that they shouldn’t have preparation," Dr. Collin replied.

In an interview, session comoderator Dr. David Maron, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla., said, "What was interesting was that they didn’t show a significant difference in cancer recurrence, although it was close to significance. So the question remains, is it in fact the mechanical bowel prep, or could there be differences in the postoperative follow-up and even the postoperative treatment of those patients who developed recurrence?"

Guidelines leave preparation up to the treating surgeon, and several studies have found no benefit at least in the short term, he noted. "This is one of the first studies that have shown that perhaps from a long-term standpoint in patients with cancer, that there may be some benefit to preoperative preparation of the bowel, although again, it’s preliminary and there’s a lot of unknowns out there."

Dr. Collin and her colleagues analyzed data from a trial among patients who underwent an elective resection for cancer, adenoma, or diverticular disease of the colon at 21 hospitals in Sweden and Germany between 1999 and 2005.

Earlier results for the entire trial population, previously reported, showed no significant reduction in 30-day rates of complications with mechanical bowel preparation (Br. J. Surg. 2007;94:689-95).

The new, long-term results for just the 841 patients with colorectal cancer – 53% of whom had a mechanical bowel preparation before their surgery – indicated those undergoing this preparation had a higher actuarial 5-year rate of cancer-specific survival (90% vs. 82%; P = .03).

The two groups were similar in terms of the 5-year rate of recurrence (80% vs. 89%, P = .08) and overall survival, Dr. Collin said.

"We looked at tumor stage to see if the explanation for patients having no mechanical bowel preparation having poorer cancer-specific survival was that they had more advanced tumors, and there was no difference in the stages" between groups, she said, with the majority of patients in both groups having stage II or III disease.

Dr. Collin disclosed no conflicts of interest related to the research.