User login

‘They’re out to get me!’: Evaluating rational fears and bizarre delusions in paranoia

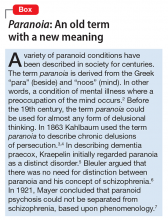

Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

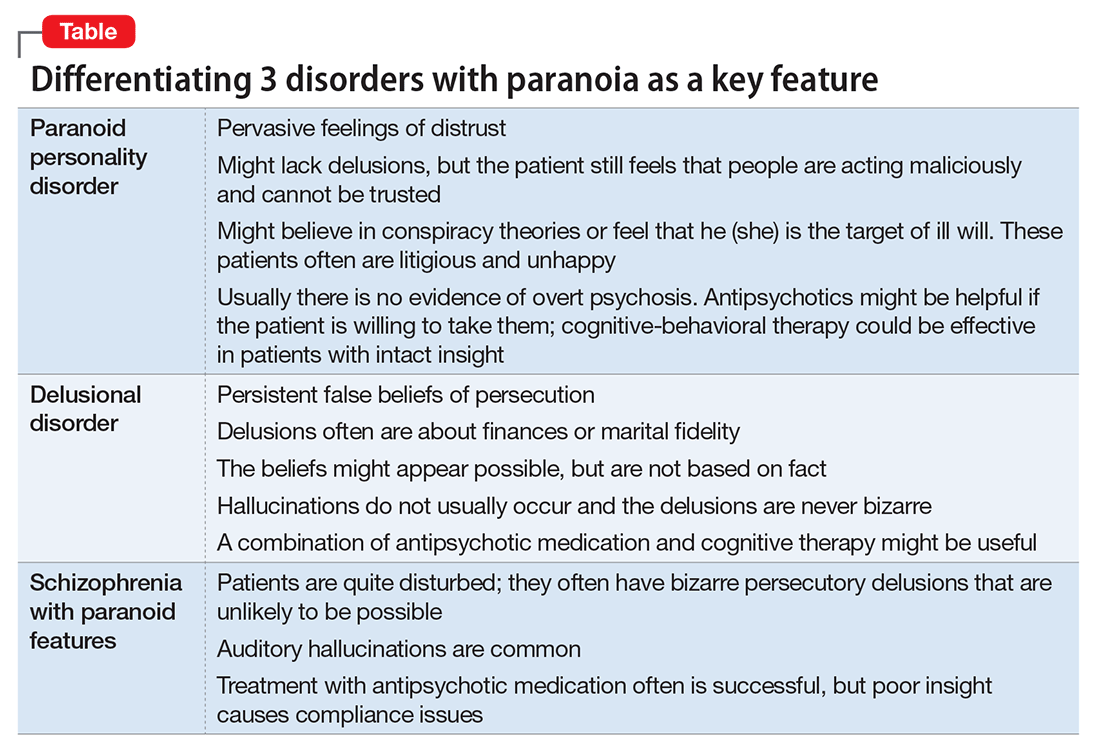

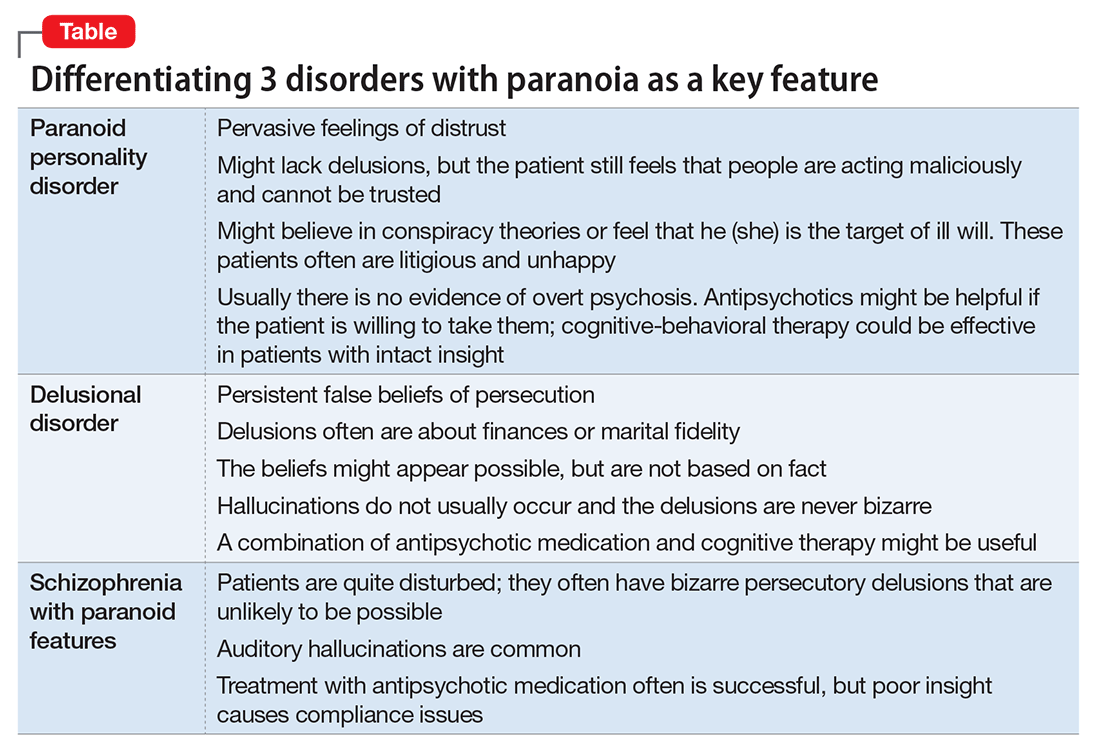

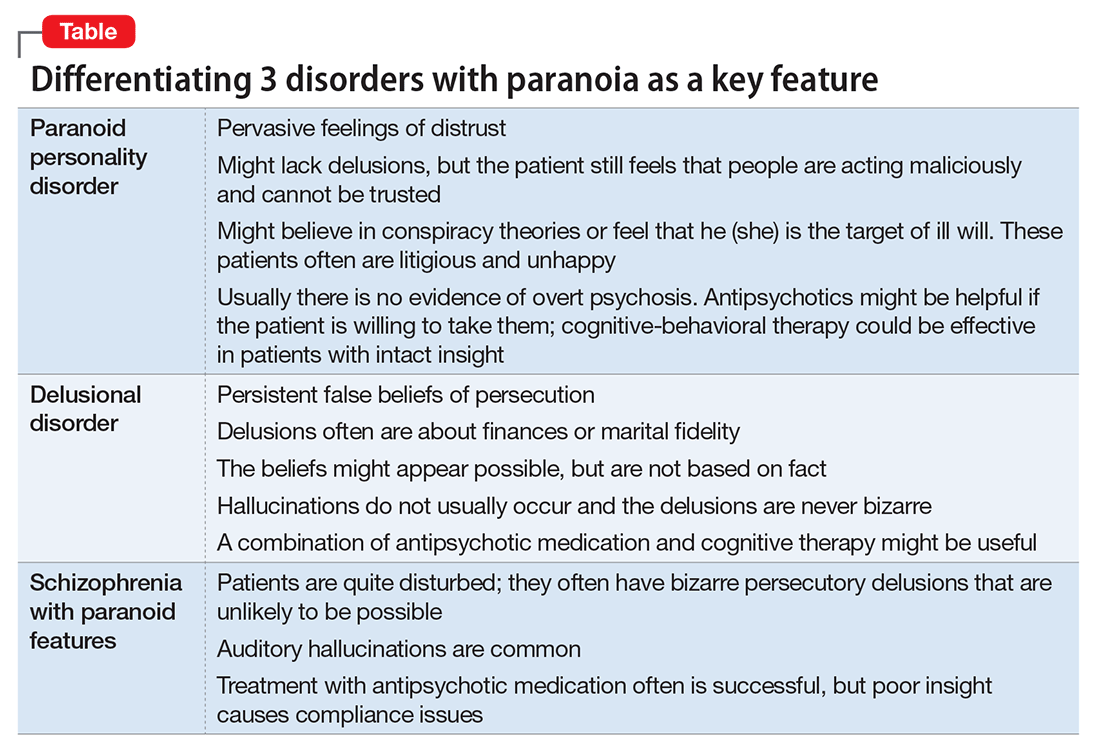

- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

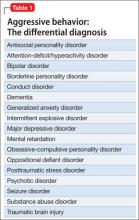

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder tend to lead maladaptive lifestyles and might present as irritable, unpleasant, and emotionally guarded. Paranoid personality disorder is not a form of delusion, but is a pattern of habitual distrust of others.

The disorder generally is expressed verbally, and is seldom accompanied by hallucinations or unpredictable behavior. Distrust of others might result in social isolation and litigious behavior.8 Alternately, a patient with this disorder might not present for treatment until later in life after the loss of significant supporting factors, such as the death of parents or loss of steady employment. Examination of these older individuals is likely to reveal long-standing suspiciousness and distrust that previously was hidden by family members. For example, a 68-year-old woman might present saying that she can’t trust her daughter, but her recently deceased spouse would not let her discuss the topic outside of the home.

The etiology of paranoid personality disorder is unknown. Family studies suggest a possible a genetic connection to paranoia in schizophrenia.12 Others hypothesize that this dysfunction of personality might originate in early feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem, learned from a controlling, cruel, or sadistic parent; the patient then expects others to reject him (her) as the parent did.13,14 Such individuals might develop deep-seated distrust of others as a defense mechanism. Under stress, such as during a medical illness, patients could develop brief psychoses. Antipsychotic treatment might be useful in some cases of paranoid personality disorder, but should be limited.

Delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a unique form of psychosis. Patients with delusional disorder might appear rational—as long as they are in independent roles—and their general functioning could go unnoticed. This could change when the delusions predominate their thoughts, or their delusional behavior is unacceptable in a structured environment. Such individuals often suffer from a highly specific delusion fixed on 1 topic. These delusions generally are the only psychotic feature. The most common theme is that of persecution. For example, a person firmly believes he is being followed by foreign agents or by a religious organization, which is blatantly untrue. Another common theme is infidelity.

Paranoia in delusional disorder is about something that is not actually occurring, but could.3 In other words, the delusion is not necessarily bizarre. The patient may have no evidence or could invent “evidence,” yet remain completely resistant to any logical argument against his belief system. In many situations, individuals with delusional disorder function normally in society, until the delusion becomes severe enough to prompt clinical attention.

Paranoia in schizophrenia

In patients with schizophrenia with paranoia, the typical symptoms of disorganization and disturbed affect are less prominent. The condition develops in young adulthood, but could start at any age. Its course typically is chronic and requires psychiatric treatment; the patient may require hospital care.

Although patients with delusional disorder and those with schizophrenia both have delusions, the delusions of the latter typically are bizarre and unlikely to be possible. For example, the patient might believe that her body has been replaced with the inner workings of an alien being or a robot. The paranoid delusions of persons with delusional disorder are much more mundane and could be plausible. Karl Jaspers, a clinician and researcher in the early 20th century, separated delusional disorder from paranoid schizophrenia by noting that the former could be “understandable, even if untrue” while the latter was “not within the realm of understandability.”5

A patient with schizophrenia with paranoid delusions usually experiences auditory hallucinations, such as voices threatening persecution or harm. When predominant, patients could be aroused by these fears and can be dangerous to others.2,4,5

Other presentations of paranoia

Paranoia can occur in affective disorders as well.13 Although the cause is only now being understood, clinicians have put forth theories for many years. A depressed person might suffer from excessive guilt and feel that he deserves to be persecuted, while a manic patient might think she is being persecuted for her greatness. In the past, response to electroconvulsive therapy was used to distinguish affective paranoia from other types.2

Paranoia in organic states

Substance use. Psychostimulants, which are known for their motor activity and arousal enhancing properties, as well as the potential for abuse and other negative consequences, could lead to acute paranoid states in susceptible individuals.15-17 In addition, tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical in Cannabis, can cause acute psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia,18,19 in a dose-dependent manner. A growing body of evidence suggests that a combination of Cannabis use with a genetic predisposition to psychosis may put some individuals at high risk of decompensation.19 Of growing concern is the evidence that synthetic cannabinoids, which are among the most commonly used new psychoactive substances, could be associated with psychosis, including paranoia.20

Dementia. Persons with dementia often are paranoid. In geriatric patients with dementia, a delusion of thievery is common. When a person has misplaced objects and can’t remember where, the “default” cognition is that someone has taken them. This confabulation may progress to a persistent paranoia and can be draining on caregivers.

Treating paranoia

A patient with paranoia usually has poor insight and cannot be reasoned with. Such individuals are quick to incorporate others into their delusional theories and easily develop notions of conspiracy. In acute psychosis, when the patient presents with fixed beliefs that are not amenable to reality orientation, and poses a threat to his well-being or that of others, alleviating underlying fear and anxiety is the first priority. Swift pharmacologic measures are required to decrease the patient’s underlying anxiety or anger, before you can try to earn his trust.

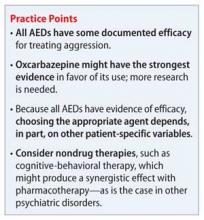

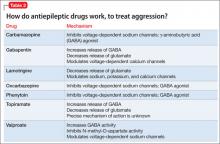

Psychopharmacologic interventions should be specific to the diagnosis. Antipsychotic medications generally will help decrease most paranoia, but affective syndromes usually require lithium or divalproex for best results.14,21

Develop a therapeutic relationship. The clinician must approach the patient in a practical and straightforward manner, and should not expect a quick therapeutic alliance. Transference and countertransference develop easily in the context of paranoia. Focus on behaviors that are problematic for the patient or the milieu, such as to ensure a safe environment. The patient needs to be aware of how he could come across to others. Clear feedback about behavior, such as “I cannot really listen to you when you’re yelling,” may be effective. It might be unwise to confront delusional paranoia in an agitated patient. Honesty and respect must continue in all communications to build trust. During assessment of a paranoid individual, evaluate the level of dangerousness. Ask your patient if he feels like acting on his beliefs or harming the people that are the targets of his paranoia.

As the patient begins to manage his anxiety and fear, you can develop a therapeutic alliance. The goals of treatment need be those of the patient—such as staying out of the hospital, or behaving in a manner that is required for employment. Over time, work toward growing the patient’s capacity for social interaction and productive activity. Insight might be elusive; however, some patients with paranoia can learn to take a detached view of their thoughts and emotions, and consider them impermanent events of the mind that make their lives difficult. Practice good judgment when aiming for recovery in a patient who does not have insight. For example, a patient can recognize that although there could be a microchip in his brain, he feels better when he takes medication.

In the case of paranoid personality disorder, treatment, as with most personality disorders, can be difficult. The patient might be unlikely to accept help and could distrust caregivers. Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be useful, if the patient can be engaged in the therapeutic process. Although it might be difficult to obtain enhanced insight, the patient could accept logical explanations for situations that provoke distrust. As long as anxiety and anger can be kept under control, the individual might learn the value of adopting the lessons of therapy. Pharmacological treatments are aimed at reducing the anxiety and anger experienced by the paranoid individual. Antipsychotics may be useful for short periods or during a crisis.14,21

The clinician must remain calm and reassuring when approaching an individual with paranoia, and not react to the projection of paranoid feelings from the patient. Respect for the patient can be conveyed without agreeing with delusions or bizarre thinking. The clinician must keep agreements and appointments with the client to prevent the erosion of trust. Paranoid conditions might respond slowly to pharmacological treatment, therefore establishing a consistent therapeutic relationship is essential.

1. Frank C. Delirium, consent to treatment, and Shakespeare. A geriatric experience. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:875-876.

2. Hamilton M. Fish’s schizophrenia. Bristol, United Kingdom: John Wright and Sons; 1962.

3. Munro A. Delusional disorder. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

4. Kahlbaum K. Die gruppierung de psychischen krankheiten. Danzig, Germany: Verlag von A. W. Kafemann; 1853.

5. Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976.

6. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Ainkia J, trans. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

7. Mayer W. Uber paraphrene psychosen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte. Neurology und Psychiatrie. 1921;71:187-206.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, et al. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):784-792.

10. Sen P, Chowdhury AN. Culture, ethnicity and paranoia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):174-178.

11. Szasz TS. The manufacture of madness: a comparative study of the inquisition and the mental health movement. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1970.

12. Schanda H, Berner P, Gabriel E, et al. The genetics of delusional psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1983;9(4):563-570.

13. Levy B, Tsoy E, Brodt T, et al. Stigma, social anxiety and illness severity in bipolar disorder: implications for treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):55-64.

14. Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Gilford Press; 1993.

15. Busardo FP, Kyriakou C, Cipilloni L, et al. From clinical application to cognitive enhancement. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):281-295.

16. McKetin R, Gardner J, Baker AL, et al. Correlates of transient versus persistent psychotic symptoms among dependent methylamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:166-171.

17. Djamshidian A. The neurobehavioral sequelae of psychostimulant abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;120:161-177.

18. Haney M, Evins AE. Does cannabis cause, exacerbate or ameliorate psychiatric disorders? An oversimplified debate discussed. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):393-401.

19. Bui QM, Simpson S, Nordstrom K. Psychiatric and medical management of marijuana intoxication in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):414-417.

20. Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, et al. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234-243.

21. Lake CR. Hypothesis: grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia; paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1151-1162.

Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder tend to lead maladaptive lifestyles and might present as irritable, unpleasant, and emotionally guarded. Paranoid personality disorder is not a form of delusion, but is a pattern of habitual distrust of others.

The disorder generally is expressed verbally, and is seldom accompanied by hallucinations or unpredictable behavior. Distrust of others might result in social isolation and litigious behavior.8 Alternately, a patient with this disorder might not present for treatment until later in life after the loss of significant supporting factors, such as the death of parents or loss of steady employment. Examination of these older individuals is likely to reveal long-standing suspiciousness and distrust that previously was hidden by family members. For example, a 68-year-old woman might present saying that she can’t trust her daughter, but her recently deceased spouse would not let her discuss the topic outside of the home.

The etiology of paranoid personality disorder is unknown. Family studies suggest a possible a genetic connection to paranoia in schizophrenia.12 Others hypothesize that this dysfunction of personality might originate in early feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem, learned from a controlling, cruel, or sadistic parent; the patient then expects others to reject him (her) as the parent did.13,14 Such individuals might develop deep-seated distrust of others as a defense mechanism. Under stress, such as during a medical illness, patients could develop brief psychoses. Antipsychotic treatment might be useful in some cases of paranoid personality disorder, but should be limited.

Delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a unique form of psychosis. Patients with delusional disorder might appear rational—as long as they are in independent roles—and their general functioning could go unnoticed. This could change when the delusions predominate their thoughts, or their delusional behavior is unacceptable in a structured environment. Such individuals often suffer from a highly specific delusion fixed on 1 topic. These delusions generally are the only psychotic feature. The most common theme is that of persecution. For example, a person firmly believes he is being followed by foreign agents or by a religious organization, which is blatantly untrue. Another common theme is infidelity.

Paranoia in delusional disorder is about something that is not actually occurring, but could.3 In other words, the delusion is not necessarily bizarre. The patient may have no evidence or could invent “evidence,” yet remain completely resistant to any logical argument against his belief system. In many situations, individuals with delusional disorder function normally in society, until the delusion becomes severe enough to prompt clinical attention.

Paranoia in schizophrenia

In patients with schizophrenia with paranoia, the typical symptoms of disorganization and disturbed affect are less prominent. The condition develops in young adulthood, but could start at any age. Its course typically is chronic and requires psychiatric treatment; the patient may require hospital care.

Although patients with delusional disorder and those with schizophrenia both have delusions, the delusions of the latter typically are bizarre and unlikely to be possible. For example, the patient might believe that her body has been replaced with the inner workings of an alien being or a robot. The paranoid delusions of persons with delusional disorder are much more mundane and could be plausible. Karl Jaspers, a clinician and researcher in the early 20th century, separated delusional disorder from paranoid schizophrenia by noting that the former could be “understandable, even if untrue” while the latter was “not within the realm of understandability.”5

A patient with schizophrenia with paranoid delusions usually experiences auditory hallucinations, such as voices threatening persecution or harm. When predominant, patients could be aroused by these fears and can be dangerous to others.2,4,5

Other presentations of paranoia

Paranoia can occur in affective disorders as well.13 Although the cause is only now being understood, clinicians have put forth theories for many years. A depressed person might suffer from excessive guilt and feel that he deserves to be persecuted, while a manic patient might think she is being persecuted for her greatness. In the past, response to electroconvulsive therapy was used to distinguish affective paranoia from other types.2

Paranoia in organic states

Substance use. Psychostimulants, which are known for their motor activity and arousal enhancing properties, as well as the potential for abuse and other negative consequences, could lead to acute paranoid states in susceptible individuals.15-17 In addition, tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical in Cannabis, can cause acute psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia,18,19 in a dose-dependent manner. A growing body of evidence suggests that a combination of Cannabis use with a genetic predisposition to psychosis may put some individuals at high risk of decompensation.19 Of growing concern is the evidence that synthetic cannabinoids, which are among the most commonly used new psychoactive substances, could be associated with psychosis, including paranoia.20

Dementia. Persons with dementia often are paranoid. In geriatric patients with dementia, a delusion of thievery is common. When a person has misplaced objects and can’t remember where, the “default” cognition is that someone has taken them. This confabulation may progress to a persistent paranoia and can be draining on caregivers.

Treating paranoia

A patient with paranoia usually has poor insight and cannot be reasoned with. Such individuals are quick to incorporate others into their delusional theories and easily develop notions of conspiracy. In acute psychosis, when the patient presents with fixed beliefs that are not amenable to reality orientation, and poses a threat to his well-being or that of others, alleviating underlying fear and anxiety is the first priority. Swift pharmacologic measures are required to decrease the patient’s underlying anxiety or anger, before you can try to earn his trust.

Psychopharmacologic interventions should be specific to the diagnosis. Antipsychotic medications generally will help decrease most paranoia, but affective syndromes usually require lithium or divalproex for best results.14,21

Develop a therapeutic relationship. The clinician must approach the patient in a practical and straightforward manner, and should not expect a quick therapeutic alliance. Transference and countertransference develop easily in the context of paranoia. Focus on behaviors that are problematic for the patient or the milieu, such as to ensure a safe environment. The patient needs to be aware of how he could come across to others. Clear feedback about behavior, such as “I cannot really listen to you when you’re yelling,” may be effective. It might be unwise to confront delusional paranoia in an agitated patient. Honesty and respect must continue in all communications to build trust. During assessment of a paranoid individual, evaluate the level of dangerousness. Ask your patient if he feels like acting on his beliefs or harming the people that are the targets of his paranoia.

As the patient begins to manage his anxiety and fear, you can develop a therapeutic alliance. The goals of treatment need be those of the patient—such as staying out of the hospital, or behaving in a manner that is required for employment. Over time, work toward growing the patient’s capacity for social interaction and productive activity. Insight might be elusive; however, some patients with paranoia can learn to take a detached view of their thoughts and emotions, and consider them impermanent events of the mind that make their lives difficult. Practice good judgment when aiming for recovery in a patient who does not have insight. For example, a patient can recognize that although there could be a microchip in his brain, he feels better when he takes medication.

In the case of paranoid personality disorder, treatment, as with most personality disorders, can be difficult. The patient might be unlikely to accept help and could distrust caregivers. Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be useful, if the patient can be engaged in the therapeutic process. Although it might be difficult to obtain enhanced insight, the patient could accept logical explanations for situations that provoke distrust. As long as anxiety and anger can be kept under control, the individual might learn the value of adopting the lessons of therapy. Pharmacological treatments are aimed at reducing the anxiety and anger experienced by the paranoid individual. Antipsychotics may be useful for short periods or during a crisis.14,21

The clinician must remain calm and reassuring when approaching an individual with paranoia, and not react to the projection of paranoid feelings from the patient. Respect for the patient can be conveyed without agreeing with delusions or bizarre thinking. The clinician must keep agreements and appointments with the client to prevent the erosion of trust. Paranoid conditions might respond slowly to pharmacological treatment, therefore establishing a consistent therapeutic relationship is essential.

Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder tend to lead maladaptive lifestyles and might present as irritable, unpleasant, and emotionally guarded. Paranoid personality disorder is not a form of delusion, but is a pattern of habitual distrust of others.

The disorder generally is expressed verbally, and is seldom accompanied by hallucinations or unpredictable behavior. Distrust of others might result in social isolation and litigious behavior.8 Alternately, a patient with this disorder might not present for treatment until later in life after the loss of significant supporting factors, such as the death of parents or loss of steady employment. Examination of these older individuals is likely to reveal long-standing suspiciousness and distrust that previously was hidden by family members. For example, a 68-year-old woman might present saying that she can’t trust her daughter, but her recently deceased spouse would not let her discuss the topic outside of the home.

The etiology of paranoid personality disorder is unknown. Family studies suggest a possible a genetic connection to paranoia in schizophrenia.12 Others hypothesize that this dysfunction of personality might originate in early feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem, learned from a controlling, cruel, or sadistic parent; the patient then expects others to reject him (her) as the parent did.13,14 Such individuals might develop deep-seated distrust of others as a defense mechanism. Under stress, such as during a medical illness, patients could develop brief psychoses. Antipsychotic treatment might be useful in some cases of paranoid personality disorder, but should be limited.

Delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a unique form of psychosis. Patients with delusional disorder might appear rational—as long as they are in independent roles—and their general functioning could go unnoticed. This could change when the delusions predominate their thoughts, or their delusional behavior is unacceptable in a structured environment. Such individuals often suffer from a highly specific delusion fixed on 1 topic. These delusions generally are the only psychotic feature. The most common theme is that of persecution. For example, a person firmly believes he is being followed by foreign agents or by a religious organization, which is blatantly untrue. Another common theme is infidelity.

Paranoia in delusional disorder is about something that is not actually occurring, but could.3 In other words, the delusion is not necessarily bizarre. The patient may have no evidence or could invent “evidence,” yet remain completely resistant to any logical argument against his belief system. In many situations, individuals with delusional disorder function normally in society, until the delusion becomes severe enough to prompt clinical attention.

Paranoia in schizophrenia

In patients with schizophrenia with paranoia, the typical symptoms of disorganization and disturbed affect are less prominent. The condition develops in young adulthood, but could start at any age. Its course typically is chronic and requires psychiatric treatment; the patient may require hospital care.

Although patients with delusional disorder and those with schizophrenia both have delusions, the delusions of the latter typically are bizarre and unlikely to be possible. For example, the patient might believe that her body has been replaced with the inner workings of an alien being or a robot. The paranoid delusions of persons with delusional disorder are much more mundane and could be plausible. Karl Jaspers, a clinician and researcher in the early 20th century, separated delusional disorder from paranoid schizophrenia by noting that the former could be “understandable, even if untrue” while the latter was “not within the realm of understandability.”5

A patient with schizophrenia with paranoid delusions usually experiences auditory hallucinations, such as voices threatening persecution or harm. When predominant, patients could be aroused by these fears and can be dangerous to others.2,4,5

Other presentations of paranoia

Paranoia can occur in affective disorders as well.13 Although the cause is only now being understood, clinicians have put forth theories for many years. A depressed person might suffer from excessive guilt and feel that he deserves to be persecuted, while a manic patient might think she is being persecuted for her greatness. In the past, response to electroconvulsive therapy was used to distinguish affective paranoia from other types.2

Paranoia in organic states

Substance use. Psychostimulants, which are known for their motor activity and arousal enhancing properties, as well as the potential for abuse and other negative consequences, could lead to acute paranoid states in susceptible individuals.15-17 In addition, tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical in Cannabis, can cause acute psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia,18,19 in a dose-dependent manner. A growing body of evidence suggests that a combination of Cannabis use with a genetic predisposition to psychosis may put some individuals at high risk of decompensation.19 Of growing concern is the evidence that synthetic cannabinoids, which are among the most commonly used new psychoactive substances, could be associated with psychosis, including paranoia.20

Dementia. Persons with dementia often are paranoid. In geriatric patients with dementia, a delusion of thievery is common. When a person has misplaced objects and can’t remember where, the “default” cognition is that someone has taken them. This confabulation may progress to a persistent paranoia and can be draining on caregivers.

Treating paranoia

A patient with paranoia usually has poor insight and cannot be reasoned with. Such individuals are quick to incorporate others into their delusional theories and easily develop notions of conspiracy. In acute psychosis, when the patient presents with fixed beliefs that are not amenable to reality orientation, and poses a threat to his well-being or that of others, alleviating underlying fear and anxiety is the first priority. Swift pharmacologic measures are required to decrease the patient’s underlying anxiety or anger, before you can try to earn his trust.

Psychopharmacologic interventions should be specific to the diagnosis. Antipsychotic medications generally will help decrease most paranoia, but affective syndromes usually require lithium or divalproex for best results.14,21

Develop a therapeutic relationship. The clinician must approach the patient in a practical and straightforward manner, and should not expect a quick therapeutic alliance. Transference and countertransference develop easily in the context of paranoia. Focus on behaviors that are problematic for the patient or the milieu, such as to ensure a safe environment. The patient needs to be aware of how he could come across to others. Clear feedback about behavior, such as “I cannot really listen to you when you’re yelling,” may be effective. It might be unwise to confront delusional paranoia in an agitated patient. Honesty and respect must continue in all communications to build trust. During assessment of a paranoid individual, evaluate the level of dangerousness. Ask your patient if he feels like acting on his beliefs or harming the people that are the targets of his paranoia.

As the patient begins to manage his anxiety and fear, you can develop a therapeutic alliance. The goals of treatment need be those of the patient—such as staying out of the hospital, or behaving in a manner that is required for employment. Over time, work toward growing the patient’s capacity for social interaction and productive activity. Insight might be elusive; however, some patients with paranoia can learn to take a detached view of their thoughts and emotions, and consider them impermanent events of the mind that make their lives difficult. Practice good judgment when aiming for recovery in a patient who does not have insight. For example, a patient can recognize that although there could be a microchip in his brain, he feels better when he takes medication.

In the case of paranoid personality disorder, treatment, as with most personality disorders, can be difficult. The patient might be unlikely to accept help and could distrust caregivers. Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be useful, if the patient can be engaged in the therapeutic process. Although it might be difficult to obtain enhanced insight, the patient could accept logical explanations for situations that provoke distrust. As long as anxiety and anger can be kept under control, the individual might learn the value of adopting the lessons of therapy. Pharmacological treatments are aimed at reducing the anxiety and anger experienced by the paranoid individual. Antipsychotics may be useful for short periods or during a crisis.14,21

The clinician must remain calm and reassuring when approaching an individual with paranoia, and not react to the projection of paranoid feelings from the patient. Respect for the patient can be conveyed without agreeing with delusions or bizarre thinking. The clinician must keep agreements and appointments with the client to prevent the erosion of trust. Paranoid conditions might respond slowly to pharmacological treatment, therefore establishing a consistent therapeutic relationship is essential.

1. Frank C. Delirium, consent to treatment, and Shakespeare. A geriatric experience. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:875-876.

2. Hamilton M. Fish’s schizophrenia. Bristol, United Kingdom: John Wright and Sons; 1962.

3. Munro A. Delusional disorder. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

4. Kahlbaum K. Die gruppierung de psychischen krankheiten. Danzig, Germany: Verlag von A. W. Kafemann; 1853.

5. Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976.

6. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Ainkia J, trans. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

7. Mayer W. Uber paraphrene psychosen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte. Neurology und Psychiatrie. 1921;71:187-206.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, et al. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):784-792.

10. Sen P, Chowdhury AN. Culture, ethnicity and paranoia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):174-178.

11. Szasz TS. The manufacture of madness: a comparative study of the inquisition and the mental health movement. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1970.

12. Schanda H, Berner P, Gabriel E, et al. The genetics of delusional psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1983;9(4):563-570.

13. Levy B, Tsoy E, Brodt T, et al. Stigma, social anxiety and illness severity in bipolar disorder: implications for treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):55-64.

14. Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Gilford Press; 1993.

15. Busardo FP, Kyriakou C, Cipilloni L, et al. From clinical application to cognitive enhancement. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):281-295.

16. McKetin R, Gardner J, Baker AL, et al. Correlates of transient versus persistent psychotic symptoms among dependent methylamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:166-171.

17. Djamshidian A. The neurobehavioral sequelae of psychostimulant abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;120:161-177.

18. Haney M, Evins AE. Does cannabis cause, exacerbate or ameliorate psychiatric disorders? An oversimplified debate discussed. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):393-401.

19. Bui QM, Simpson S, Nordstrom K. Psychiatric and medical management of marijuana intoxication in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):414-417.

20. Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, et al. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234-243.

21. Lake CR. Hypothesis: grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia; paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1151-1162.

1. Frank C. Delirium, consent to treatment, and Shakespeare. A geriatric experience. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:875-876.

2. Hamilton M. Fish’s schizophrenia. Bristol, United Kingdom: John Wright and Sons; 1962.

3. Munro A. Delusional disorder. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

4. Kahlbaum K. Die gruppierung de psychischen krankheiten. Danzig, Germany: Verlag von A. W. Kafemann; 1853.

5. Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976.

6. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Ainkia J, trans. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

7. Mayer W. Uber paraphrene psychosen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte. Neurology und Psychiatrie. 1921;71:187-206.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, et al. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):784-792.

10. Sen P, Chowdhury AN. Culture, ethnicity and paranoia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):174-178.

11. Szasz TS. The manufacture of madness: a comparative study of the inquisition and the mental health movement. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1970.

12. Schanda H, Berner P, Gabriel E, et al. The genetics of delusional psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1983;9(4):563-570.

13. Levy B, Tsoy E, Brodt T, et al. Stigma, social anxiety and illness severity in bipolar disorder: implications for treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):55-64.

14. Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Gilford Press; 1993.

15. Busardo FP, Kyriakou C, Cipilloni L, et al. From clinical application to cognitive enhancement. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):281-295.

16. McKetin R, Gardner J, Baker AL, et al. Correlates of transient versus persistent psychotic symptoms among dependent methylamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:166-171.

17. Djamshidian A. The neurobehavioral sequelae of psychostimulant abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;120:161-177.

18. Haney M, Evins AE. Does cannabis cause, exacerbate or ameliorate psychiatric disorders? An oversimplified debate discussed. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):393-401.

19. Bui QM, Simpson S, Nordstrom K. Psychiatric and medical management of marijuana intoxication in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):414-417.

20. Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, et al. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234-243.

21. Lake CR. Hypothesis: grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia; paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1151-1162.

Managing borderline personality disorder

What do >700 letters to a mass murderer tell us about the people who wrote them?

Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer

• whether a photograph was enclosed

• whether additional items were enclosed (eg, gifts, drawings)

• whether the letter was rejected by prison authorities

• the writer’s purpose.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Letters were assigned to 1 of 5 categories:

Acquaintance letters sought ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer. They focused largely on conveying information about the writer.

Show of support letters also sought an ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer, but instead focused on him, not the writer.

Romance letters used words that conveyed romantic or non-platonic affection.

Spiritual letters gave advice to the murderer with a religious tone.

Words of wisdom letters offered advice but lacked a religious tone.

Given the nonstandardized nature of categorization and the lack of a formal questionnaire, we were unable to perform an exploratory factor analysis on our categorizations. Inter-rater reliability of letter categorization was 0.79.

Results: Writer profiles, purpose for writing

In all, we reviewed 819 letters:

• Thirty-five letters were excluded because they were written by family members, children, or other prisoners

• Of the remaining 784 letters, there were 333 unique writers

• Two-hundred sixty letters were written by women, 61 by men; 2 were co-written by both sexes; sex could not be determined for 10.

Women were more likely than men to write a letter (P = .014) and to write ≥3 letters (P = .001). The age of the writer was determined for 117 (35.1%) letters; mean age was 27.8 (± 8.9) years (range, 18 to 59 years).

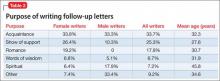

The purpose of the letters differed by sex (P < .001) but not by the writer’s age (P = .058). Women were more likely than men to write letters categorized as “Acquaintance,” “Romance,” and “Show of support”; in contrast, men were more likely than women to write a letter categorized as “Spiritual” (Table 1). Approximately 95% of letters were handwritten. Letters averaged 3 pages (range, 1 to 16 pages).

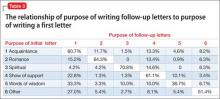

Two-hundred sixteen writers wrote a single letter; 53 wrote 2 letters; 18 wrote 3 letters; 11 wrote 4 letters; 30 wrote 5 to 10 letters; and 9 wrote 11 to 43 letters. The purpose of follow-up letters was associated with the age of the writer (P < .001) and with the writer’s sex (P < .001). Women were more likely to write “Show of support” and “Romance” follow-up letters; men were more likely to write “Spiritual” follow-up letters (Table 2).

Results suggested that the purpose of the initial letter was a reasonable predictor of the purpose of follow-up letters (P < .001) (Table 3). The murderer never responded to any letters. Letters were most often written from his state of incarceration; next, from contiguous states; then, from non-contiguous states; and, last, from international locations (P < .001).

Of the initial letters from writers who wrote ≥10, 60% were categorized as “Acquaintance” and 20% as “Romance.” The writer who wrote the most letters (43) moved during the course of her letter-writing to live in the same state as the murderer; she stated in her letters that she did so to be closer to him and to be able to attend his court hearings. Four other writers, each of whom wrote >5 letters, stated that they had traveled to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend some of his hearings in person.

Composite examples of more common categories of letters

Names and other pertinent identifying information have been changed.

Acquaintance. Hi, Steve. I’ve been following your case and just wanted to write you so that maybe we could be friends or keep in touch since you’re probably pretty bored. I’m a 27-year-old college student studying marketing and working at Applebee’s as a waitress (for now) until I can land my dream job. I’ve enclosed a picture of me and my dachshund along with a photo of my favorite beach in the world. Write me back if you want. Jenny.

Show of support. Steve: I’ve been really worried about you since first seeing you on TV. You look different lately and I hope they’re treating you OK and feeding you decent food. In case they’re not, I’ve enclosed a little something to buy yourself a treat. Just know that there are many of us that care about you and are really pulling for you to be strong in this tough situation you’re in. Yours truly, Karen.

Romance. Dearest Steven: My mind has been filled with thoughts of you and of us since I last saw you in my dreams! Be strong, because you are going to beat this once they understand that you are not responsible for what happened! Don’t you see, sweetie, the system failed you, and now you’re caught up in something that you will soon overcome. When I think of the day that you get released, and how we’ll be able to settle down somewhere together, it gets me incredibly excited. You and I are meant to be together, because I understand you and can help you get better. I love you, Steven! Please write me back so that I know we’re on the same page about our plans for the future. Love, ♥ Your sweetie, Rachel.

Spiritual. Dear Child of God: The Lord has a plan for you. I know that things right now might be confusing, and you’re in a black place, but He is there right beside you. If you need some reading materials to give you comfort, just let me know and I can get a Bible to you along with some other books to give you solace and strengthen your walk with Him. God forgives you and he loves you so much! Much love in Christ, Mary.

Discussion

Given that the mass murderer in this study was a young man, it is not surprising that 78% of writers of initial letters were women. However, it is interesting that, among women’s initial letters, 44% were “Acquaintance” letters and only 15% were categorized as “Romance.”

Given the severity of the murderer’s crime, it is remarkable that he received only 1 “Hate mail” letter.

Initial “Spiritual” letters were more likely to be followed by letters of the same category than any other category; “Romance” letters were a close second. This demonstrates the consistent efforts of writers in these 2 categories. Highly persistent writers (≥10 letters) were most likely to fall into “Acquaintance” and “Romance” categories. The persistence of these writers is remarkable, in view of the fact that none of their letters were answered. We hypothesize that the killer did not reply because he had no interest in correspondence.

Similarities to stalking. Given that 9 writers wrote >10 letters each and 2 wrote >20 each, elements of their behavior are not unlike what is seen in stalkers.3 Consistent with the stalking literature and Mullen et al4 stalker typology, many writers in this study appeared to seek intimacy with the perpetrator through “Romance” or “Show of support” letters, and might be akin to Mullen’s so-called intimacy-seeking stalker. Such stalkers’ behavior arises out of loneliness, with a strong desire for a relationship with the target; a significant percentage of such stalkers suffer a delusional disorder.

Mullen’s so-called incompetent suitor stalker is similar to the intimacy-seeking type but, instead, has an interest in a short-term relationship and is far less persistent in his (her) stalking behavior4; this type might apply to the writers in this study who wrote >1 but <10 letters.

Two additional observations also are notable when trying to characterize people who write letters: (1) A high percentage of people who stalk a celebrity suffer a psychotic disorder5,6; (2) 4 letter-writers traveled, and 1 relocated, to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend his hearings and be closer to him.

This study has limitations:

• categorization of letters is inherently subjective and the categories themselves were created by the researchers

• the nature and categorization of such letters might vary considerably with the age and sex of the violent criminal; our findings in this case are not generalizable.

Last, researchers who plan to study writers of letters to incarcerated criminals should consider sending a personality test and other questionnaires to those writers to understand this population better.

Treatment considerations

Psychiatrists treating patients who seek a romantic attachment with a violent person should consider psychotherapy as a means of treating possible character pathology. The desire for romance with a violent criminal was greater among repeat writers (20%) than in initial letters (15%), suggesting that people who have a strong inclination to associate with a violent person might benefit from exploring romantic feelings in therapy. Specifically, therapists would be wise to explore with such patients the possibility that they experienced violence or verbal abuse in childhood or adulthood.

To the extent that evidence of prior abuse exists, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might be appropriate; specialized therapy for men and women with a history of abuse might be indicated. It is important to provide validation for patients who are victims when they describe their abuse, and to stress that they did nothing to provoke the violence. Furthermore, investigation of why the patient feels drawn romantically toward a violent criminal is helpful, as well as an examination of how such behavior is self-defeating.

There might be value in having patients keep a journal in lieu of actually sending letters; there is evidence that “journaling” can reduce substance use recidivism.7 This work can be performed in conjunction with group or individual psychotherapy that addresses any history of abuse and subsequent PTSD.

Many patients are reluctant to discuss their romantic feelings toward a violent criminal until the psychiatrist has established a strong doctor−patient relationship. Last, clinicians should not hesitate to refer these patients to a therapist who specializes in domestic violence.

Related Resource

• Marazziti D, Falaschi V, Lombardi A, et al. Stalking: a neurobiological perspective. Riv Psichiatr. 2015;50(1):12-18.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mouradian VE. Women’s stay-leave decisions in relationships involving intimate partner violence. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley Centers for Women Publications; 2004:3,4.

2. Bell KM, Naugle AE. Understanding stay/leave decisions in violent relationships: a behavior analytic approach. Behav Soc Issues. 2005;14(1):21-46.

3. Westrup D, Fremouw WJ. Stalking behavior: a literature review and suggested functional analytic assessment technology. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3: 255-274.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

5. West SG, Friedman SH. These boots are made for stalking: characteristics of female stalkers. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2008;5(8):37-42.

6. Nadkarni R, Grubin D. Stalking: why do people do it? BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1486-1487.

7. Proctor SL, Hoffmann NG, Allison S. The effectiveness of interactive journaling in reducing recidivism among substance-dependent jail inmates. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2012;56(2):317-332.

Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer

• whether a photograph was enclosed

• whether additional items were enclosed (eg, gifts, drawings)

• whether the letter was rejected by prison authorities

• the writer’s purpose.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Letters were assigned to 1 of 5 categories:

Acquaintance letters sought ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer. They focused largely on conveying information about the writer.

Show of support letters also sought an ongoing correspondence relationship with the murderer, but instead focused on him, not the writer.

Romance letters used words that conveyed romantic or non-platonic affection.

Spiritual letters gave advice to the murderer with a religious tone.

Words of wisdom letters offered advice but lacked a religious tone.

Given the nonstandardized nature of categorization and the lack of a formal questionnaire, we were unable to perform an exploratory factor analysis on our categorizations. Inter-rater reliability of letter categorization was 0.79.

Results: Writer profiles, purpose for writing

In all, we reviewed 819 letters:

• Thirty-five letters were excluded because they were written by family members, children, or other prisoners

• Of the remaining 784 letters, there were 333 unique writers

• Two-hundred sixty letters were written by women, 61 by men; 2 were co-written by both sexes; sex could not be determined for 10.

Women were more likely than men to write a letter (P = .014) and to write ≥3 letters (P = .001). The age of the writer was determined for 117 (35.1%) letters; mean age was 27.8 (± 8.9) years (range, 18 to 59 years).

The purpose of the letters differed by sex (P < .001) but not by the writer’s age (P = .058). Women were more likely than men to write letters categorized as “Acquaintance,” “Romance,” and “Show of support”; in contrast, men were more likely than women to write a letter categorized as “Spiritual” (Table 1). Approximately 95% of letters were handwritten. Letters averaged 3 pages (range, 1 to 16 pages).

Two-hundred sixteen writers wrote a single letter; 53 wrote 2 letters; 18 wrote 3 letters; 11 wrote 4 letters; 30 wrote 5 to 10 letters; and 9 wrote 11 to 43 letters. The purpose of follow-up letters was associated with the age of the writer (P < .001) and with the writer’s sex (P < .001). Women were more likely to write “Show of support” and “Romance” follow-up letters; men were more likely to write “Spiritual” follow-up letters (Table 2).

Results suggested that the purpose of the initial letter was a reasonable predictor of the purpose of follow-up letters (P < .001) (Table 3). The murderer never responded to any letters. Letters were most often written from his state of incarceration; next, from contiguous states; then, from non-contiguous states; and, last, from international locations (P < .001).

Of the initial letters from writers who wrote ≥10, 60% were categorized as “Acquaintance” and 20% as “Romance.” The writer who wrote the most letters (43) moved during the course of her letter-writing to live in the same state as the murderer; she stated in her letters that she did so to be closer to him and to be able to attend his court hearings. Four other writers, each of whom wrote >5 letters, stated that they had traveled to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend some of his hearings in person.

Composite examples of more common categories of letters

Names and other pertinent identifying information have been changed.

Acquaintance. Hi, Steve. I’ve been following your case and just wanted to write you so that maybe we could be friends or keep in touch since you’re probably pretty bored. I’m a 27-year-old college student studying marketing and working at Applebee’s as a waitress (for now) until I can land my dream job. I’ve enclosed a picture of me and my dachshund along with a photo of my favorite beach in the world. Write me back if you want. Jenny.

Show of support. Steve: I’ve been really worried about you since first seeing you on TV. You look different lately and I hope they’re treating you OK and feeding you decent food. In case they’re not, I’ve enclosed a little something to buy yourself a treat. Just know that there are many of us that care about you and are really pulling for you to be strong in this tough situation you’re in. Yours truly, Karen.

Romance. Dearest Steven: My mind has been filled with thoughts of you and of us since I last saw you in my dreams! Be strong, because you are going to beat this once they understand that you are not responsible for what happened! Don’t you see, sweetie, the system failed you, and now you’re caught up in something that you will soon overcome. When I think of the day that you get released, and how we’ll be able to settle down somewhere together, it gets me incredibly excited. You and I are meant to be together, because I understand you and can help you get better. I love you, Steven! Please write me back so that I know we’re on the same page about our plans for the future. Love, ♥ Your sweetie, Rachel.

Spiritual. Dear Child of God: The Lord has a plan for you. I know that things right now might be confusing, and you’re in a black place, but He is there right beside you. If you need some reading materials to give you comfort, just let me know and I can get a Bible to you along with some other books to give you solace and strengthen your walk with Him. God forgives you and he loves you so much! Much love in Christ, Mary.

Discussion

Given that the mass murderer in this study was a young man, it is not surprising that 78% of writers of initial letters were women. However, it is interesting that, among women’s initial letters, 44% were “Acquaintance” letters and only 15% were categorized as “Romance.”

Given the severity of the murderer’s crime, it is remarkable that he received only 1 “Hate mail” letter.

Initial “Spiritual” letters were more likely to be followed by letters of the same category than any other category; “Romance” letters were a close second. This demonstrates the consistent efforts of writers in these 2 categories. Highly persistent writers (≥10 letters) were most likely to fall into “Acquaintance” and “Romance” categories. The persistence of these writers is remarkable, in view of the fact that none of their letters were answered. We hypothesize that the killer did not reply because he had no interest in correspondence.

Similarities to stalking. Given that 9 writers wrote >10 letters each and 2 wrote >20 each, elements of their behavior are not unlike what is seen in stalkers.3 Consistent with the stalking literature and Mullen et al4 stalker typology, many writers in this study appeared to seek intimacy with the perpetrator through “Romance” or “Show of support” letters, and might be akin to Mullen’s so-called intimacy-seeking stalker. Such stalkers’ behavior arises out of loneliness, with a strong desire for a relationship with the target; a significant percentage of such stalkers suffer a delusional disorder.

Mullen’s so-called incompetent suitor stalker is similar to the intimacy-seeking type but, instead, has an interest in a short-term relationship and is far less persistent in his (her) stalking behavior4; this type might apply to the writers in this study who wrote >1 but <10 letters.

Two additional observations also are notable when trying to characterize people who write letters: (1) A high percentage of people who stalk a celebrity suffer a psychotic disorder5,6; (2) 4 letter-writers traveled, and 1 relocated, to the murderer’s state of incarceration to attend his hearings and be closer to him.

This study has limitations:

• categorization of letters is inherently subjective and the categories themselves were created by the researchers

• the nature and categorization of such letters might vary considerably with the age and sex of the violent criminal; our findings in this case are not generalizable.

Last, researchers who plan to study writers of letters to incarcerated criminals should consider sending a personality test and other questionnaires to those writers to understand this population better.

Treatment considerations

Psychiatrists treating patients who seek a romantic attachment with a violent person should consider psychotherapy as a means of treating possible character pathology. The desire for romance with a violent criminal was greater among repeat writers (20%) than in initial letters (15%), suggesting that people who have a strong inclination to associate with a violent person might benefit from exploring romantic feelings in therapy. Specifically, therapists would be wise to explore with such patients the possibility that they experienced violence or verbal abuse in childhood or adulthood.

To the extent that evidence of prior abuse exists, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might be appropriate; specialized therapy for men and women with a history of abuse might be indicated. It is important to provide validation for patients who are victims when they describe their abuse, and to stress that they did nothing to provoke the violence. Furthermore, investigation of why the patient feels drawn romantically toward a violent criminal is helpful, as well as an examination of how such behavior is self-defeating.

There might be value in having patients keep a journal in lieu of actually sending letters; there is evidence that “journaling” can reduce substance use recidivism.7 This work can be performed in conjunction with group or individual psychotherapy that addresses any history of abuse and subsequent PTSD.

Many patients are reluctant to discuss their romantic feelings toward a violent criminal until the psychiatrist has established a strong doctor−patient relationship. Last, clinicians should not hesitate to refer these patients to a therapist who specializes in domestic violence.

Related Resource

• Marazziti D, Falaschi V, Lombardi A, et al. Stalking: a neurobiological perspective. Riv Psichiatr. 2015;50(1):12-18.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Little is known about people who write to criminals incarcerated for a violent crime. However, existence of Web sites such as WriteAPrisoner.com, Meet-An-Inmate.com, and PrisonPenPals.com suggests some appetite among the public for corresponding with the incarcerated. Writers of letters might be drawn to the “bad boy” image of prisoners. Furthermore, much has been written of the willingness of some battered women to remain in an abusive domestic relationship, leading them to correspond with their abusers even after those abusers are incarcerated.1,2

To our knowledge, no examination of letters written to a mass murderer has been published. Therefore, we categorized and analyzed 784 letters sent to a high-profile male mass murderer whose crime was committed during the past decade. Here is a description of the study and what we found, as well as discussion of how our findings might offer utility in a psychiatric practice.

Goals of the study

We hypothesized that a large percentage of those letters could be classified as “Romantic,” given the lay perception that it is women who write to mass murderers. We also sought to evaluate follow-up letters sent by these writers to test the assumption that their individual goals would be constant over time.

We performed this study in the hope that the research could assist psychiatric practitioners in treating patients who seek to associate with a violent person (see “Treatment considerations,”). We thought it might be helpful for practitioners to get a better understanding of the nature of people who write to a violent offender or express a desire to do so.

Methods of study

Two authors (R.S.J. and D.P.G.) evaluated 819 letters that had been written by non-incarcerated, non-family adults to 1 mass murderer. The initial letter and follow-up letters written by each unique writer (n = 333) were categorized as follows:

• state or country from which the letter was sent

• age

• sex

• number of letters sent by each writer