User login

Working with other disciplines

Stalked by a ‘patient’

CASE: Delusions and threats

For over 20 months, Ms. I, age 48, sends a psychiatric resident letters and postcards that total approximately 3,000 pages and come from dozens of return addresses. Ms. I expresses romantic feelings toward the resident and believes that he was her physician and prescribed medications, including “mood stabilizers.” The resident never treated Ms. I; to his knowledge, he has never interacted with her.

Ms. I describes the resident’s refusal to continue treating her as “abandonment” and states that she is contemplating self-harm because of this rejection. In her letters, Ms. I admits that she was a long-term patient in a state psychiatric hospital in her home state and suffers from persistent auditory hallucinations. She also wants a romantic relationship with the resident and repeatedly threatens the resident’s female acquaintances and former romantic partners whose relationships she had surmised from news articles available on the Internet. Ms. I also threatens to strangle the resident. The resident sends her multiple written requests that she cease contact, but they are not acknowledged.

The authors’ observations

Stalking—repeated, unwanted attention or communication that would cause a reasonable person fear—is a serious threat for many psychiatric clinicians.1 Prevalence rates among mental health care providers range from 3% to 21%.2,3 Most stalkers have engaged in previous stalking behavior.3

Being stalked is highly distressing,4 and mental health professionals often do not reveal such experiences to colleagues.5 Irrational feelings of guilt or embarrassment, such as being thought to have poorly managed interactions with the stalker, often motivate a self-imposed silence (Table 1).6 This isolation may foster anxiety, interfere with receiving problem-solving advice, and increase physical vulnerability. In the case involving Ms. I, the psychiatric resident’s primary responsibility is safeguarding his own physical and psychological welfare.

Clinicians who work in a hospital or other institutional setting who are being stalked should inform their supervisors and the facility’s security personnel. Security personnel may be able to gather data about the stalker, decrease the stalker’s ability to communicate with the victim, and reduce unwanted physical access to the victim by distributing a photo of the stalker or installing a camera or receptionist-controlled door lock in patient entryways. Security personnel also may collaborate with local law enforcement. Having a third party respond to a stalker’s aggressive behavior—rather than the victim responding directly—avoids rewarding the stalker, which may generate further unwanted contact.7 Any intervention by the victim may increase the risk of violence, creating an “intervention dilemma.” Resnick8 argues that before deciding how best to address the stalker’s behavior, a stalking victim must “first separate the risk of continued stalking from the risk that the stalker will commit a violent act.”

Mental health professionals in private practice who are being stalked should consider retaining an attorney. An attorney often can maintain privacy of communications regarding the stalker via the attorney-client and attorney-work product privileges, which may help during legal proceedings.

Table 1

Factors that can impede psychiatrists from reporting stalking

| Fear of being perceived as a failure |

| Embarrassment |

| High professional tolerance for antisocial and threatening behavior |

| Misplaced sense of duty |

| Source: Reference 6 |

RESPONSE: Involving police

Over 2 months, Ms. I phones the resident’s home 105 times (the resident screens the calls). During 1 call, she states that she is hidden in a closet in her home and will hurt herself unless the resident “resumes” her psychiatric care. The resident contacts police in his city and Ms. I’s community, but authorities are reluctant to act when he acknowledges that he is not Ms. I’s psychiatrist and does not know her. Police officers in Ms. I’s hometown tell the resident no one answered the door when they visited her home. They state that they would enter the residence forcibly only if Ms. I’s physician or a family member asked them to do so, and because the resident admits that he is not her psychiatrist, they cannot take further action. Ms. I leaves the resident a phone message several hours later to inform him she is safe.

The authors’ observations

Stalking-induced countertransference responses may lead a psychiatrist to unwittingly place himself in harm’s way. For example, intense rage at a stalker’s request for treatment may generate guilt that motivates the psychiatrist to agree to treat the stalker. Feelings of helplessness may produce a frantic desire to do something even when such activity is ill-advised. Psychiatrists may develop a tolerance for antisocial or threatening behavior—which is common in mental health settings—and could accept unnecessary risks.

A psychiatrist who is being stalked may be able to assist a mentally ill stalker in a way that does not create a duty to treat and does not expose the psychiatrist to harm, such as contacting a mobile crisis intervention team, a mental health professional who recently treated the stalker, a family member of the stalker, or law enforcement personnel. A psychiatrist who is thrust from the role of helper to victim and must protect his or her own well-being instead of attending to a patient’s welfare is prone to suffer substantial countertransference distress.

The situation with Ms. I was particularly challenging because the resident did not know her complete history and therefore had little information to gauge how likely she was to act on her aggressive threats. Factors that predict future violence include:

- a history of violence

- significant prior criminality

- young age at first arrest

- concomitant substance abuse

- male sex.9

Unfortunately, other than sex, this data regarding Ms. I could not be readily obtained.

A psychiatrist’s duty

Although sympathetic to his stalker’s distress, the resident did not want to treat this woman, nor was he ethically or legally obligated to do so. An individual’s wish to be treated by a particular psychiatrist does not create a duty for the psychiatrist to satisfy this wish.10 State-based “Good Samaritan” laws encourage physicians to assist those in acute need by shielding them from liability, as long as they reasonably act within the scope of their expertise.11 However, they do not require a physician to care for an individual in acute need. A delusional wish for treatment or a false belief of already being in treatment does not create a duty to care for a person.

OUTCOME: Seeking help

Ms. I’s phone calls and letters continue. The resident discusses the situation with his associate residency director, who refers him to the hospital’s legal and investigative staffs. Based on advice from the hospital’s private investigator, the resident sends Ms. I a formal “cease and desist” letter that threatens her with legal action and possible jail time. The staff at the front desk of the clinic where the resident works and the hospital’s security department are instructed to watch for a visitor with Ms. I’s name and description, although the hospital’s investigator is unable to obtain a photograph of her. Shortly after the resident sends the letter, Ms. I ceases communication.

The authors’ observations

This case is unusual because most stalking victims know their stalkers. Identifying a stalker’s motivation can be helpful in formulating a risk assessment. One classification system recognizes 5 categories of stalkers: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 2).1 Rejected stalkers appear to pose the greatest risk of violence and homicide.8 However, all stalkers may pose a risk of violence and therefore all stalking behavior should be treated seriously.

Table 2

Classification of stalkers

| Category | Common features |

|---|---|

| Rejected | Most have a personality disorder; often seeking reconciliation and revenge; most frequent victims are ex-romantic partners, but also target estranged relatives, former friends |

| Intimacy seeking | Erotomania; “morbid infatuation” |

| Incompetent | Lacking social skills; often have stalked others |

| Resentful | Pursuing a vendetta; generally feeling aggrieved |

| Predatory | Often comorbid with paraphilias; may have past convictions for sex offenses |

| Source: Adapted from reference 1 | |

Responding to a stalker

The approach should be tailored to the stalker’s characteristics.12 Silence—ie, lack of acknowledgement of a stalker’s intrusions—is one tactic.13 Consistent and persistent lack of engagement may bore the stalker, but also may provoke frustration or narcissistic or paranoia-fueled rage, and increased efforts to interact with the mental health professional. Other responses include:

- obtaining a protection or restraining order

- promoting the stalker’s participation in adversarial civil litigation, such as a lawsuit

- issuing verbal counterthreats.

Restraining orders are controversial and assessments of their effectiveness vary.14 How well a restraining order works may depend on the stalker’s:

- ability to appreciate reality, and how likely he or she is to experience anxiety when confronted with adverse consequences of his or her actions

- how consistently, rapidly, and harshly the criminal justice system responds to violations of restraining orders.

Restraining orders also may provide the victim a false sense of security.15 One of her letters revealed that Ms. I violated a criminal plea arrangement years earlier, which suggests she was capable of violating a restraining order.

Litigation. A stalker may initiate civil litigation against the victim to feel that he or she has an impact on the victim, which may reduce the stalker’s risk of violence if he or she is emotionally engaged in the litigation. Based on the authors’ experience, as long as the stalker is talking, he or she generally is less likely to act out violently and terminate a satisfying process. Adversarial civil litigation could give a stalker the opportunity to be “close” to the victim and a means of expressing aggressive wishes. The benefit of litigation lasts only as long as the case persists and the stalker believes he or she may prevail. In one of her letters, Ms. I bragged that she had represented herself as a pro se litigant in a complex civil matter, suggesting that she might be constructively channeled into litigation.

Promoting litigation carries significant risk.16 Being a defendant in pro se litigation may be emotionally and financially stressful. This approach may be desirable if the psychiatrist’s institution is willing to offer substantial support. For example, an institution may provide legal assistance—including helping to defray the cost of litigation—and litigation-related scheduling flexibility. An attorney may serve as a boundary between the victim and the pro se litigant’s sometimes ceaseless, time-devouring, anxiety-inducing legal maneuvers.

Counterthreats. Warning a stalker that he or she will face severe civil and criminal consequences if his or her behavior continues can make clear that his or her conduct is unacceptable.17 Such warnings may be delivered verbally or in writing by a legal representative, law enforcement personnel, a private security agent, or the victim.

Issuing a counterthreat can be risky. Stalkers with antisocial or narcissistic personality features may perceive a counterthreat as narcissistically diminishing, and to save face will escalate their stalking in retaliation. Avoid counterthreats if you believe the stalker might be psychotic because destabilizing such an individual—such as by precipitating a short psychotic episode—may increase unpredictability and diminish their responsive to interventions.

Ms. I’s contact with the resident lasted approximately 20 months, slightly less than the average 26 months reported in a survey of mental health professionals.3 Because stalkers are unpredictable, the psychiatric resident remains cautious.

Related Resources

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Stalking resource center. www.victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/stalking-resource-center.

- Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R. Stalkers and their victims. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

2. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by psychiatric patients toward clinicians. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):221-229.

3. McIvor R, Potter L, Davies L. Stalking behavior by patients towards psychiatrists in a large mental health organization. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(4):350-357.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M. Stalking. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:273-318.

5. Bird S. Strategies for managing and minimizing the impact of harassment and stalking by patients. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7-8):537-538.

6. Sinwelski SA, Vinton L. Stalking: the constant threat of violence. Affilia. 2001;16(1):46-65.

7. Meloy JR. Commentary: stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by patients—the risk-management response. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):230-231.

8. Resnick PJ. Stalking risk assessment. In: Pinals DA, ed. Stalking: psychiatric perspectives and practical approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:61–84.

9. Dietz PE. Defenses against dangerous people when arrest and commitment fail. In: Simon RI, ed. American Psychiatric Press review of clinical psychiatry and the law. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1989:205–219.

10. Hilliard J. Termination of treatment with troublesome patients. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law: a comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:216–224.

11. Paterick TJ, Paterick BB, Paterick TE. Implications of Good Samaritan laws for physicians. J Med Pract Manage. 2008;23(6):372-375.

12. MacKenzie RD, James DV. Management and treatment of stalkers: problems options, and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2011;29(2):220-239.

13. Fremouw WJ, Westrup D, Pennypacker J. Stalking on campus: the prevalence and strategies for coping with stalking. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(4):666-669.

14. Nicastro AM, Cousins AV, Spitzberg BH. The tactical face of stalking. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2000;28(1):69-82.

15. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

16. Pathé M, MacKenzie R, Mullen PE. Stalking by law: damaging victims and rewarding offenders. J Law Med. 2004;12(1):103-111.

17. Lion JR, Herschler JA. The stalking of physicians by their patients. In: Meloy JR. The psychology of stalking: clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998:163–173.

CASE: Delusions and threats

For over 20 months, Ms. I, age 48, sends a psychiatric resident letters and postcards that total approximately 3,000 pages and come from dozens of return addresses. Ms. I expresses romantic feelings toward the resident and believes that he was her physician and prescribed medications, including “mood stabilizers.” The resident never treated Ms. I; to his knowledge, he has never interacted with her.

Ms. I describes the resident’s refusal to continue treating her as “abandonment” and states that she is contemplating self-harm because of this rejection. In her letters, Ms. I admits that she was a long-term patient in a state psychiatric hospital in her home state and suffers from persistent auditory hallucinations. She also wants a romantic relationship with the resident and repeatedly threatens the resident’s female acquaintances and former romantic partners whose relationships she had surmised from news articles available on the Internet. Ms. I also threatens to strangle the resident. The resident sends her multiple written requests that she cease contact, but they are not acknowledged.

The authors’ observations

Stalking—repeated, unwanted attention or communication that would cause a reasonable person fear—is a serious threat for many psychiatric clinicians.1 Prevalence rates among mental health care providers range from 3% to 21%.2,3 Most stalkers have engaged in previous stalking behavior.3

Being stalked is highly distressing,4 and mental health professionals often do not reveal such experiences to colleagues.5 Irrational feelings of guilt or embarrassment, such as being thought to have poorly managed interactions with the stalker, often motivate a self-imposed silence (Table 1).6 This isolation may foster anxiety, interfere with receiving problem-solving advice, and increase physical vulnerability. In the case involving Ms. I, the psychiatric resident’s primary responsibility is safeguarding his own physical and psychological welfare.

Clinicians who work in a hospital or other institutional setting who are being stalked should inform their supervisors and the facility’s security personnel. Security personnel may be able to gather data about the stalker, decrease the stalker’s ability to communicate with the victim, and reduce unwanted physical access to the victim by distributing a photo of the stalker or installing a camera or receptionist-controlled door lock in patient entryways. Security personnel also may collaborate with local law enforcement. Having a third party respond to a stalker’s aggressive behavior—rather than the victim responding directly—avoids rewarding the stalker, which may generate further unwanted contact.7 Any intervention by the victim may increase the risk of violence, creating an “intervention dilemma.” Resnick8 argues that before deciding how best to address the stalker’s behavior, a stalking victim must “first separate the risk of continued stalking from the risk that the stalker will commit a violent act.”

Mental health professionals in private practice who are being stalked should consider retaining an attorney. An attorney often can maintain privacy of communications regarding the stalker via the attorney-client and attorney-work product privileges, which may help during legal proceedings.

Table 1

Factors that can impede psychiatrists from reporting stalking

| Fear of being perceived as a failure |

| Embarrassment |

| High professional tolerance for antisocial and threatening behavior |

| Misplaced sense of duty |

| Source: Reference 6 |

RESPONSE: Involving police

Over 2 months, Ms. I phones the resident’s home 105 times (the resident screens the calls). During 1 call, she states that she is hidden in a closet in her home and will hurt herself unless the resident “resumes” her psychiatric care. The resident contacts police in his city and Ms. I’s community, but authorities are reluctant to act when he acknowledges that he is not Ms. I’s psychiatrist and does not know her. Police officers in Ms. I’s hometown tell the resident no one answered the door when they visited her home. They state that they would enter the residence forcibly only if Ms. I’s physician or a family member asked them to do so, and because the resident admits that he is not her psychiatrist, they cannot take further action. Ms. I leaves the resident a phone message several hours later to inform him she is safe.

The authors’ observations

Stalking-induced countertransference responses may lead a psychiatrist to unwittingly place himself in harm’s way. For example, intense rage at a stalker’s request for treatment may generate guilt that motivates the psychiatrist to agree to treat the stalker. Feelings of helplessness may produce a frantic desire to do something even when such activity is ill-advised. Psychiatrists may develop a tolerance for antisocial or threatening behavior—which is common in mental health settings—and could accept unnecessary risks.

A psychiatrist who is being stalked may be able to assist a mentally ill stalker in a way that does not create a duty to treat and does not expose the psychiatrist to harm, such as contacting a mobile crisis intervention team, a mental health professional who recently treated the stalker, a family member of the stalker, or law enforcement personnel. A psychiatrist who is thrust from the role of helper to victim and must protect his or her own well-being instead of attending to a patient’s welfare is prone to suffer substantial countertransference distress.

The situation with Ms. I was particularly challenging because the resident did not know her complete history and therefore had little information to gauge how likely she was to act on her aggressive threats. Factors that predict future violence include:

- a history of violence

- significant prior criminality

- young age at first arrest

- concomitant substance abuse

- male sex.9

Unfortunately, other than sex, this data regarding Ms. I could not be readily obtained.

A psychiatrist’s duty

Although sympathetic to his stalker’s distress, the resident did not want to treat this woman, nor was he ethically or legally obligated to do so. An individual’s wish to be treated by a particular psychiatrist does not create a duty for the psychiatrist to satisfy this wish.10 State-based “Good Samaritan” laws encourage physicians to assist those in acute need by shielding them from liability, as long as they reasonably act within the scope of their expertise.11 However, they do not require a physician to care for an individual in acute need. A delusional wish for treatment or a false belief of already being in treatment does not create a duty to care for a person.

OUTCOME: Seeking help

Ms. I’s phone calls and letters continue. The resident discusses the situation with his associate residency director, who refers him to the hospital’s legal and investigative staffs. Based on advice from the hospital’s private investigator, the resident sends Ms. I a formal “cease and desist” letter that threatens her with legal action and possible jail time. The staff at the front desk of the clinic where the resident works and the hospital’s security department are instructed to watch for a visitor with Ms. I’s name and description, although the hospital’s investigator is unable to obtain a photograph of her. Shortly after the resident sends the letter, Ms. I ceases communication.

The authors’ observations

This case is unusual because most stalking victims know their stalkers. Identifying a stalker’s motivation can be helpful in formulating a risk assessment. One classification system recognizes 5 categories of stalkers: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 2).1 Rejected stalkers appear to pose the greatest risk of violence and homicide.8 However, all stalkers may pose a risk of violence and therefore all stalking behavior should be treated seriously.

Table 2

Classification of stalkers

| Category | Common features |

|---|---|

| Rejected | Most have a personality disorder; often seeking reconciliation and revenge; most frequent victims are ex-romantic partners, but also target estranged relatives, former friends |

| Intimacy seeking | Erotomania; “morbid infatuation” |

| Incompetent | Lacking social skills; often have stalked others |

| Resentful | Pursuing a vendetta; generally feeling aggrieved |

| Predatory | Often comorbid with paraphilias; may have past convictions for sex offenses |

| Source: Adapted from reference 1 | |

Responding to a stalker

The approach should be tailored to the stalker’s characteristics.12 Silence—ie, lack of acknowledgement of a stalker’s intrusions—is one tactic.13 Consistent and persistent lack of engagement may bore the stalker, but also may provoke frustration or narcissistic or paranoia-fueled rage, and increased efforts to interact with the mental health professional. Other responses include:

- obtaining a protection or restraining order

- promoting the stalker’s participation in adversarial civil litigation, such as a lawsuit

- issuing verbal counterthreats.

Restraining orders are controversial and assessments of their effectiveness vary.14 How well a restraining order works may depend on the stalker’s:

- ability to appreciate reality, and how likely he or she is to experience anxiety when confronted with adverse consequences of his or her actions

- how consistently, rapidly, and harshly the criminal justice system responds to violations of restraining orders.

Restraining orders also may provide the victim a false sense of security.15 One of her letters revealed that Ms. I violated a criminal plea arrangement years earlier, which suggests she was capable of violating a restraining order.

Litigation. A stalker may initiate civil litigation against the victim to feel that he or she has an impact on the victim, which may reduce the stalker’s risk of violence if he or she is emotionally engaged in the litigation. Based on the authors’ experience, as long as the stalker is talking, he or she generally is less likely to act out violently and terminate a satisfying process. Adversarial civil litigation could give a stalker the opportunity to be “close” to the victim and a means of expressing aggressive wishes. The benefit of litigation lasts only as long as the case persists and the stalker believes he or she may prevail. In one of her letters, Ms. I bragged that she had represented herself as a pro se litigant in a complex civil matter, suggesting that she might be constructively channeled into litigation.

Promoting litigation carries significant risk.16 Being a defendant in pro se litigation may be emotionally and financially stressful. This approach may be desirable if the psychiatrist’s institution is willing to offer substantial support. For example, an institution may provide legal assistance—including helping to defray the cost of litigation—and litigation-related scheduling flexibility. An attorney may serve as a boundary between the victim and the pro se litigant’s sometimes ceaseless, time-devouring, anxiety-inducing legal maneuvers.

Counterthreats. Warning a stalker that he or she will face severe civil and criminal consequences if his or her behavior continues can make clear that his or her conduct is unacceptable.17 Such warnings may be delivered verbally or in writing by a legal representative, law enforcement personnel, a private security agent, or the victim.

Issuing a counterthreat can be risky. Stalkers with antisocial or narcissistic personality features may perceive a counterthreat as narcissistically diminishing, and to save face will escalate their stalking in retaliation. Avoid counterthreats if you believe the stalker might be psychotic because destabilizing such an individual—such as by precipitating a short psychotic episode—may increase unpredictability and diminish their responsive to interventions.

Ms. I’s contact with the resident lasted approximately 20 months, slightly less than the average 26 months reported in a survey of mental health professionals.3 Because stalkers are unpredictable, the psychiatric resident remains cautious.

Related Resources

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Stalking resource center. www.victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/stalking-resource-center.

- Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R. Stalkers and their victims. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Delusions and threats

For over 20 months, Ms. I, age 48, sends a psychiatric resident letters and postcards that total approximately 3,000 pages and come from dozens of return addresses. Ms. I expresses romantic feelings toward the resident and believes that he was her physician and prescribed medications, including “mood stabilizers.” The resident never treated Ms. I; to his knowledge, he has never interacted with her.

Ms. I describes the resident’s refusal to continue treating her as “abandonment” and states that she is contemplating self-harm because of this rejection. In her letters, Ms. I admits that she was a long-term patient in a state psychiatric hospital in her home state and suffers from persistent auditory hallucinations. She also wants a romantic relationship with the resident and repeatedly threatens the resident’s female acquaintances and former romantic partners whose relationships she had surmised from news articles available on the Internet. Ms. I also threatens to strangle the resident. The resident sends her multiple written requests that she cease contact, but they are not acknowledged.

The authors’ observations

Stalking—repeated, unwanted attention or communication that would cause a reasonable person fear—is a serious threat for many psychiatric clinicians.1 Prevalence rates among mental health care providers range from 3% to 21%.2,3 Most stalkers have engaged in previous stalking behavior.3

Being stalked is highly distressing,4 and mental health professionals often do not reveal such experiences to colleagues.5 Irrational feelings of guilt or embarrassment, such as being thought to have poorly managed interactions with the stalker, often motivate a self-imposed silence (Table 1).6 This isolation may foster anxiety, interfere with receiving problem-solving advice, and increase physical vulnerability. In the case involving Ms. I, the psychiatric resident’s primary responsibility is safeguarding his own physical and psychological welfare.

Clinicians who work in a hospital or other institutional setting who are being stalked should inform their supervisors and the facility’s security personnel. Security personnel may be able to gather data about the stalker, decrease the stalker’s ability to communicate with the victim, and reduce unwanted physical access to the victim by distributing a photo of the stalker or installing a camera or receptionist-controlled door lock in patient entryways. Security personnel also may collaborate with local law enforcement. Having a third party respond to a stalker’s aggressive behavior—rather than the victim responding directly—avoids rewarding the stalker, which may generate further unwanted contact.7 Any intervention by the victim may increase the risk of violence, creating an “intervention dilemma.” Resnick8 argues that before deciding how best to address the stalker’s behavior, a stalking victim must “first separate the risk of continued stalking from the risk that the stalker will commit a violent act.”

Mental health professionals in private practice who are being stalked should consider retaining an attorney. An attorney often can maintain privacy of communications regarding the stalker via the attorney-client and attorney-work product privileges, which may help during legal proceedings.

Table 1

Factors that can impede psychiatrists from reporting stalking

| Fear of being perceived as a failure |

| Embarrassment |

| High professional tolerance for antisocial and threatening behavior |

| Misplaced sense of duty |

| Source: Reference 6 |

RESPONSE: Involving police

Over 2 months, Ms. I phones the resident’s home 105 times (the resident screens the calls). During 1 call, she states that she is hidden in a closet in her home and will hurt herself unless the resident “resumes” her psychiatric care. The resident contacts police in his city and Ms. I’s community, but authorities are reluctant to act when he acknowledges that he is not Ms. I’s psychiatrist and does not know her. Police officers in Ms. I’s hometown tell the resident no one answered the door when they visited her home. They state that they would enter the residence forcibly only if Ms. I’s physician or a family member asked them to do so, and because the resident admits that he is not her psychiatrist, they cannot take further action. Ms. I leaves the resident a phone message several hours later to inform him she is safe.

The authors’ observations

Stalking-induced countertransference responses may lead a psychiatrist to unwittingly place himself in harm’s way. For example, intense rage at a stalker’s request for treatment may generate guilt that motivates the psychiatrist to agree to treat the stalker. Feelings of helplessness may produce a frantic desire to do something even when such activity is ill-advised. Psychiatrists may develop a tolerance for antisocial or threatening behavior—which is common in mental health settings—and could accept unnecessary risks.

A psychiatrist who is being stalked may be able to assist a mentally ill stalker in a way that does not create a duty to treat and does not expose the psychiatrist to harm, such as contacting a mobile crisis intervention team, a mental health professional who recently treated the stalker, a family member of the stalker, or law enforcement personnel. A psychiatrist who is thrust from the role of helper to victim and must protect his or her own well-being instead of attending to a patient’s welfare is prone to suffer substantial countertransference distress.

The situation with Ms. I was particularly challenging because the resident did not know her complete history and therefore had little information to gauge how likely she was to act on her aggressive threats. Factors that predict future violence include:

- a history of violence

- significant prior criminality

- young age at first arrest

- concomitant substance abuse

- male sex.9

Unfortunately, other than sex, this data regarding Ms. I could not be readily obtained.

A psychiatrist’s duty

Although sympathetic to his stalker’s distress, the resident did not want to treat this woman, nor was he ethically or legally obligated to do so. An individual’s wish to be treated by a particular psychiatrist does not create a duty for the psychiatrist to satisfy this wish.10 State-based “Good Samaritan” laws encourage physicians to assist those in acute need by shielding them from liability, as long as they reasonably act within the scope of their expertise.11 However, they do not require a physician to care for an individual in acute need. A delusional wish for treatment or a false belief of already being in treatment does not create a duty to care for a person.

OUTCOME: Seeking help

Ms. I’s phone calls and letters continue. The resident discusses the situation with his associate residency director, who refers him to the hospital’s legal and investigative staffs. Based on advice from the hospital’s private investigator, the resident sends Ms. I a formal “cease and desist” letter that threatens her with legal action and possible jail time. The staff at the front desk of the clinic where the resident works and the hospital’s security department are instructed to watch for a visitor with Ms. I’s name and description, although the hospital’s investigator is unable to obtain a photograph of her. Shortly after the resident sends the letter, Ms. I ceases communication.

The authors’ observations

This case is unusual because most stalking victims know their stalkers. Identifying a stalker’s motivation can be helpful in formulating a risk assessment. One classification system recognizes 5 categories of stalkers: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 2).1 Rejected stalkers appear to pose the greatest risk of violence and homicide.8 However, all stalkers may pose a risk of violence and therefore all stalking behavior should be treated seriously.

Table 2

Classification of stalkers

| Category | Common features |

|---|---|

| Rejected | Most have a personality disorder; often seeking reconciliation and revenge; most frequent victims are ex-romantic partners, but also target estranged relatives, former friends |

| Intimacy seeking | Erotomania; “morbid infatuation” |

| Incompetent | Lacking social skills; often have stalked others |

| Resentful | Pursuing a vendetta; generally feeling aggrieved |

| Predatory | Often comorbid with paraphilias; may have past convictions for sex offenses |

| Source: Adapted from reference 1 | |

Responding to a stalker

The approach should be tailored to the stalker’s characteristics.12 Silence—ie, lack of acknowledgement of a stalker’s intrusions—is one tactic.13 Consistent and persistent lack of engagement may bore the stalker, but also may provoke frustration or narcissistic or paranoia-fueled rage, and increased efforts to interact with the mental health professional. Other responses include:

- obtaining a protection or restraining order

- promoting the stalker’s participation in adversarial civil litigation, such as a lawsuit

- issuing verbal counterthreats.

Restraining orders are controversial and assessments of their effectiveness vary.14 How well a restraining order works may depend on the stalker’s:

- ability to appreciate reality, and how likely he or she is to experience anxiety when confronted with adverse consequences of his or her actions

- how consistently, rapidly, and harshly the criminal justice system responds to violations of restraining orders.

Restraining orders also may provide the victim a false sense of security.15 One of her letters revealed that Ms. I violated a criminal plea arrangement years earlier, which suggests she was capable of violating a restraining order.

Litigation. A stalker may initiate civil litigation against the victim to feel that he or she has an impact on the victim, which may reduce the stalker’s risk of violence if he or she is emotionally engaged in the litigation. Based on the authors’ experience, as long as the stalker is talking, he or she generally is less likely to act out violently and terminate a satisfying process. Adversarial civil litigation could give a stalker the opportunity to be “close” to the victim and a means of expressing aggressive wishes. The benefit of litigation lasts only as long as the case persists and the stalker believes he or she may prevail. In one of her letters, Ms. I bragged that she had represented herself as a pro se litigant in a complex civil matter, suggesting that she might be constructively channeled into litigation.

Promoting litigation carries significant risk.16 Being a defendant in pro se litigation may be emotionally and financially stressful. This approach may be desirable if the psychiatrist’s institution is willing to offer substantial support. For example, an institution may provide legal assistance—including helping to defray the cost of litigation—and litigation-related scheduling flexibility. An attorney may serve as a boundary between the victim and the pro se litigant’s sometimes ceaseless, time-devouring, anxiety-inducing legal maneuvers.

Counterthreats. Warning a stalker that he or she will face severe civil and criminal consequences if his or her behavior continues can make clear that his or her conduct is unacceptable.17 Such warnings may be delivered verbally or in writing by a legal representative, law enforcement personnel, a private security agent, or the victim.

Issuing a counterthreat can be risky. Stalkers with antisocial or narcissistic personality features may perceive a counterthreat as narcissistically diminishing, and to save face will escalate their stalking in retaliation. Avoid counterthreats if you believe the stalker might be psychotic because destabilizing such an individual—such as by precipitating a short psychotic episode—may increase unpredictability and diminish their responsive to interventions.

Ms. I’s contact with the resident lasted approximately 20 months, slightly less than the average 26 months reported in a survey of mental health professionals.3 Because stalkers are unpredictable, the psychiatric resident remains cautious.

Related Resources

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Stalking resource center. www.victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/stalking-resource-center.

- Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R. Stalkers and their victims. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

2. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by psychiatric patients toward clinicians. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):221-229.

3. McIvor R, Potter L, Davies L. Stalking behavior by patients towards psychiatrists in a large mental health organization. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(4):350-357.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M. Stalking. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:273-318.

5. Bird S. Strategies for managing and minimizing the impact of harassment and stalking by patients. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7-8):537-538.

6. Sinwelski SA, Vinton L. Stalking: the constant threat of violence. Affilia. 2001;16(1):46-65.

7. Meloy JR. Commentary: stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by patients—the risk-management response. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):230-231.

8. Resnick PJ. Stalking risk assessment. In: Pinals DA, ed. Stalking: psychiatric perspectives and practical approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:61–84.

9. Dietz PE. Defenses against dangerous people when arrest and commitment fail. In: Simon RI, ed. American Psychiatric Press review of clinical psychiatry and the law. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1989:205–219.

10. Hilliard J. Termination of treatment with troublesome patients. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law: a comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:216–224.

11. Paterick TJ, Paterick BB, Paterick TE. Implications of Good Samaritan laws for physicians. J Med Pract Manage. 2008;23(6):372-375.

12. MacKenzie RD, James DV. Management and treatment of stalkers: problems options, and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2011;29(2):220-239.

13. Fremouw WJ, Westrup D, Pennypacker J. Stalking on campus: the prevalence and strategies for coping with stalking. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(4):666-669.

14. Nicastro AM, Cousins AV, Spitzberg BH. The tactical face of stalking. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2000;28(1):69-82.

15. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

16. Pathé M, MacKenzie R, Mullen PE. Stalking by law: damaging victims and rewarding offenders. J Law Med. 2004;12(1):103-111.

17. Lion JR, Herschler JA. The stalking of physicians by their patients. In: Meloy JR. The psychology of stalking: clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998:163–173.

1. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

2. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by psychiatric patients toward clinicians. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):221-229.

3. McIvor R, Potter L, Davies L. Stalking behavior by patients towards psychiatrists in a large mental health organization. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(4):350-357.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M. Stalking. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:273-318.

5. Bird S. Strategies for managing and minimizing the impact of harassment and stalking by patients. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7-8):537-538.

6. Sinwelski SA, Vinton L. Stalking: the constant threat of violence. Affilia. 2001;16(1):46-65.

7. Meloy JR. Commentary: stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by patients—the risk-management response. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):230-231.

8. Resnick PJ. Stalking risk assessment. In: Pinals DA, ed. Stalking: psychiatric perspectives and practical approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:61–84.

9. Dietz PE. Defenses against dangerous people when arrest and commitment fail. In: Simon RI, ed. American Psychiatric Press review of clinical psychiatry and the law. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1989:205–219.

10. Hilliard J. Termination of treatment with troublesome patients. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law: a comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:216–224.

11. Paterick TJ, Paterick BB, Paterick TE. Implications of Good Samaritan laws for physicians. J Med Pract Manage. 2008;23(6):372-375.

12. MacKenzie RD, James DV. Management and treatment of stalkers: problems options, and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2011;29(2):220-239.

13. Fremouw WJ, Westrup D, Pennypacker J. Stalking on campus: the prevalence and strategies for coping with stalking. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(4):666-669.

14. Nicastro AM, Cousins AV, Spitzberg BH. The tactical face of stalking. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2000;28(1):69-82.

15. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

16. Pathé M, MacKenzie R, Mullen PE. Stalking by law: damaging victims and rewarding offenders. J Law Med. 2004;12(1):103-111.

17. Lion JR, Herschler JA. The stalking of physicians by their patients. In: Meloy JR. The psychology of stalking: clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998:163–173.

Psychotropic-induced dry mouth: Don’t overlook this potentially serious side effect

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Xerostomia, commonly known as “dry mouth,” is a reported side effect of >1,800 drugs from >80 classes.1 This condition often goes unrecognized and untreated, but it can significantly affect patients’ quality of life and cause oral and medical health problems.2,3 Although psychotropic medications are not the only offenders, they comprise a large portion of the agents that can cause dry mouth. Antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, and alpha agonists can cause xerostomia.4 The risk of salivary hypofunction increases with polypharmacy and may be especially likely when ≥3 drugs are taken per day.5

Among all reported side effects of antidepressants and antipsychotics, dry mouth often is the most prevalent complaint. For example, in a study of 5 antidepressants 35% to 46% of patients reported dry mouth.6 Rates are similar in users of various antipsychotics. Patients with severe, persistent mental illness often cite side effects as the primary reason for psychotropic noncompliance.7-9

Few psychiatrists routinely screen patients for xerostomia, and if a patient reports this side effect, they may be unlikely to address it or understand its implications because of more pressing concerns such as psychosis or risk of suicide. Historically, education in general medical training about the effects of oral health on a patient’s overall health has been limited. It is crucial for psychiatrists to be aware of potential problems related to dry mouth and the impact it can have on their patients. In this article, we:

- describe how dry mouth can impact a patient’s oral, medical, and psychiatric health

- provide psychiatrists with an understanding of pathology related to xerostomia

- explain how psychiatrists can screen for xerostomia

- discuss the benefits patients may receive when psychiatrists collaborate with dental clinicians to manage this condition.

Implications of xerostomia

Saliva provides a protective function. It is an antimicrobial, buffering, and lubricating agent that aids cleansing and removal of food debris within the mouth. It also helps maintain oral mucosa and remineralizing of tooth structure.10

Psychotropics can affect the amount of saliva secreted and may alter the composition of saliva via their receptor affects on the dual sympathetic and parasympathetic innervations of the salivary glands.11 When the protective environment produced by saliva is altered, patients may start to develop oral problems before experiencing dryness. A 50% reduction in saliva flow may occur before they become aware of the problem.12,13

Patients may not taste food properly, experience cracked lips, or have trouble eating, oral pain, or dentures that no longer fit well.14 Additionally, oral diseases such as dental decay and periodontal disease (Photos 1 and 2), inflamed soft tissue, and candidiasis (Photo 3) also may occur.10,15 Patients may begin to notice dry mouth when they wake at night, which could disrupt sleep. Patients with xerostomia can accumulate excessive amounts of plaque on their teeth and the dorsum of the tongue. The increased bacterial count and release of volatile sulfide gases that occur with dry mouth may explain some cases of halitosis.16,17 Patients also may have difficulty swallowing or speaking and be unaware of the oral health destruction occurring as a result of reduced saliva. Some experts report oral bacteria levels can skyrocket as much as 10-fold in people who take medications that cause dry mouth.18

Infections of the mouth can create havoc elsewhere in the body. The evidence base that establishes an association between periodontal disease and other chronic inflammatory conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis is steadily growing.19-22 Periodontal disease also is a risk factor for preeclampsia and other illnesses that can negatively affect neonatal health.23,24

Failure to recognize xerostomia caused by psychotropic medications may lead to an increase in cavities, periodontal disease, and chronic systemic inflammatory conditions that can shorten a patient’s life span. Recognizing and treating causes of xerostomia is vital because doing so may halt this chain of events.

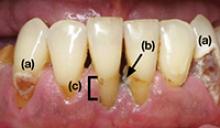

Photo 1

This patient complained of dry mouth and exhibits decay (a) and evidence of periodontal disease. Plaque and calculus is present (b), along with gingival recession from the loss of attachment and bone (c). This patient was taking venlafaxine, zolpidem, and alprazolam

Photo 2

Dental cavities were restored with tooth-colored restorations (arrows) on this patient, who has xerostomia. Every effort must be made to manage this patient’s dry mouth or the restorations may fail due to recurrent decay

Photo 3

This partial denture wearer, who complained of dry mouth, has evidence of palatal irritation and sores as a result of xerostomia and use of a partial denture. This patient was taking bupropion, esomeprazole, and tolterodine

Psychiatric patients’ oral health

Psychiatric patients’ oral health status often is poor. Several studies found that compared with the general population, patients who have severe, persistent mental illness are at higher risk to be missing teeth, schedule fewer visits to the dentist, and neglect oral hygiene.25-28 Periodontal disease also could be a problem in these patients.29 Although some evidence suggests mental illness may make patients less likely to go to the dentist, psychotropic medications also may contribute to their dental difficulties.

Screening for xerostomia

Simply advising patients of the problems related to xerostomia and asking several questions may help prevent pain and deterioration in function within the oral cavity (Table 1).14,30

You can perform a simple in-office assessment of the oral cavity by visual inspection and by placing a dry tongue blade against the inside of the cheek mucosa. If the blade sticks to the mucosa and a gentle tug is needed to lift it away, xerostomia may be present.30 Conversely, a healthy mouth will have a collection of saliva on the floor of the oral cavity, and pulling a tongue blade away from the inside of the cheek will not require any effort (Photos 4 and 5).

Table 1

Screening questions for xerostomia

| Does the amount of saliva in your mouth seem to have decreased? |

| Do you have any trouble swallowing, speaking, or eating dry foods? |

| Do you sip liquids more often to help you swallow? |

| Do you notice any dryness or cracking of your lips? |

| Do you have mouth sores or a burning feeling in the mouth? |

| When was the last time you saw your dentist? (Patients with xerostomia may need to see their dentist more frequently) |

| Are you aware of any halitosis (ie, mouth odor)? |

| Source: Reference 14 |

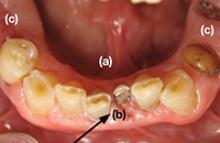

Photo 4

The arrow shows the normal appearance of saliva collecting on the floor of the mouth

Photo 5

This patient complained of dry mouth. Note the floor of the mouth is free of saliva (a). Decay is present (b), and the patient is missing posterior teeth (c). This patient was taking clonidine, metoprolol, hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, and irbesartan

Treatment options

Patients who have reduced salivary flow as a result of a medication may become so affected by dryness that their drug regimen may need to be changed. However, the greatest concern is for deteriorating oral health among patients who may be unaware xerostomia is occurring.31

Counsel patients who take medications that can affect their salivary function about the importance of seeing a dentist regularly, and provide referrals when appropriate. Depending upon the patient’s oral health, dentists recommend patients with xerostomia have their teeth cleaned/examined 3 or 4 times per year, rather than the 2 times per year allowed by third-party payers (ie, insurance companies). Also advise patients to be diligent in their oral hygiene practices, including flossing and brushing the teeth and tongue, and to avoid foods that are sticky and/or have high sucrose content (Table 2). Recommend using a toothpaste containing fluoride—preferably one free of sodium lauryl sulfate, which could contribute to mouth sores14—and drinking fluoridated water. Explain to patients that their dentist may recommend in-office high-fluoride applications, high-fluoride prescription toothpaste, and/or “mouth trays” that contain high fluoride gel. Tell patients to avoid cigarettes and caffeinated beverages, which can increase dryness. Alcohol use should be minimized and mouth rinses containing alcohol should not be used.

Many over-the-counter products are available to address xerostomia, including toothpastes, mouth rinses, and gels. Salivary substitutes—which are available as sprays, liquids, tablets, and swab sticks—imitate saliva and may provide a temporary reprieve from dryness. Although none of these products will cure dry mouth, they may help manage the condition. Advise patients to eat foods that stimulate saliva production, such as carrots, apples, and celery, and to chew sugarless gum and candies, which also will stimulate salivary flow.

The FDA has approved 2 prescription drugs for treating xerostomia: cevimeline and pilocarpine. Cevimeline is approved for treating dry mouth associated with Sjögren’s syndrome and pilocarpine is approved for treating dry mouth caused by head and neck radiation therapy; however, these medications’ role in treating dry mouth in psychiatric patients has not been investigated. Both agents are contraindicated in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma, uncontrolled asthma, or liver disease, and should be prescribed with caution for patients with cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory conditions, or kidney disease.32

Acupuncture and electrostimulation are being studied as a treatment for xerostomia. Trials have found acupuncture improves symptoms of xerostomia,33,34 and 1 study found electrostimulation improved xerostomia in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.35 Both approaches require more study to confirm their effectiveness.33-35

Table 2

Managing dry mouth: What to tell patients

| Oral hygiene. Tell patients to be diligent in their oral hygiene practices, including brushing and flossing. They should use a toothpaste containing fluoride—preferably one free of sodium lauryl sulfate—and schedule regular dental visits, where they can receive high-fluoride applications or be prescribed high-fluoride prescription toothpastes |

| Diet. Advise patients to avoid foods high in sucrose content, rinse their mouth with water soon after eating, and drink fluoridated water regularly. Tell them that they may be able to stimulate saliva flow with sugarless gum, candies, and foods such as celery and carrots |

| Drying agents. Instruct patients to avoid cigarettes, caffeinated beverages, and mouth rinses that contain alcohol. Explain that some patients may benefit from sleeping in a room with a cool air humidifier |

| Over-the-counter products. Suggest patients try salivary substitutes, which are dispensed in spray bottles, rinses, swish bottles, or oral swab sticks. In addition, products such as dry-mouth toothpaste and moisturizing gels also may help relieve their symptoms |

- Persson K, Axtelius B, Söderfeldt B, et al. Monitoring oral health and dental attendance in an outpatient psychiatric population. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16(3):263-271.

- Keene JJ Jr, Galasko GT, Land MF. Antidepressant use in psychiatry and medicine: importance for dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(1):71-79.

Drug Brand Names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amlodipine • Norvasc

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Cevimeline • Evoxac

- Clonidine • Catapres, Kapvay, others

- Esomeprazole • Nexium

- Irbesartan • Avapro

- Metoprolol • Lopressor, Toprol

- Pilocarpine • Salagen

- Tolterodine • Detrol

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Drymouth.info. Overview of drugs and dry mouth. http://drymouth.info/practitioner/overview.asp. Accessed September 2, 2011.

2. Stewart CM, Berg KM, Cha S, et al. Salivary dysfunction and quality of life in Sjögren syndrome: a critical oral-systemic connection. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(3):291-299.

3. Friedman PK. Xerostomia: The invisible oral health condition. http://www.dentistryiq.com/index/display/article-display/295922/articles/woman-dentist-journal/health/xerostomia-the-invisible-oral-health-condition.html. Accessed September 6, 2011.

4. Physician Desk Reference. Montvale NJ: PDR Network LLC.; 2011.

5. Bardow A, Lagerlof F, Nauntofte B, et al. The role of saliva. In: Fejerskov O, Kidd E, eds. Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2008:195.

6. Vanderkooy JD, Kennedy SH, Bagby RM. Antidepressant side effects in depression patients treated in a naturalistic setting: a study of bupropion moclobemide, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(2):174-180.

7. Löffler W, Kilian R, Toumi M, et al. Schizophrenic patients’ subjective reasons for compliance and noncompliance with neuroleptic treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(3):105-112.

8. Lambert M, Conus P, Eide P, et al. Impact of present and past antipsychotic side effects on attitude toward typical antipsychotic treatment and adherence. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):415-422.

9. Rettenbacher MA, Hofer A, Eder U, et al. Compliance in schizophrenia: psychopathology, side effects, and patients’ attitudes toward the illness and medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(9):1211-1218.

10. Bulkacz J, Carranza FA. Defense mechanisms of the gingiva. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, et al, eds. Carranza’s clinical periodontology. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:69–70.

11. Szabadi E, Tavernor S. Hypo-and hyper-salivation induced by psychoactive drugs. CNS Drugs. 1999;11(6):449-466.

12. Guggenheimer J, Moore PA. Xerostomia: etiology recognition and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(1):61-69.

13. Dawes C. Physiological factors affecting salivary flow rate oral sugar clearance, and the sensation of dry mouth in man. J Dent Res. 1987;66:648-653.

14. Bartels CL. Xerostomia information for dentists. http://www.homesteadschools.com/dental/courses/Xerostomia/Course.htm. Accessed August 15, 2011.

15. Sitheeque MA, Samaranayake LP. Chronic hyperplastic candidosis/candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(4):253-267.

16. Porter SR, Scully C. Oral malodour (halitosis). BMJ. 2006;333(7569):632-635.

17. Quirynen M, Van den Veide S, Vanderkerckhove B, et al. Oral malodor. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, et al, eds. Carranza’s clinical periodontology. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:333.

18. Papas A. Dry mouth from drugs: more than just an annoying side effect. Tufts University Heath and Nutrition Letter. 2000;3.-

19. American Academy of Periodontology. Gum disease information from the American Academy of Periodontology http://perio.org. Accessed August 12, 2011.

20. Geismar K, Stoltze K, Sigurd B, et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2006;77(9):1547-1554.

21. Lee HJ, Garcia RI, Janket SJ, et al. The association between cumulative periodontal disease and stroke history in older adults. J Periodontol. 2006;77(10):1744-1754.

22. Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology editors’ consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80(7):1021-1032.

23. Contreras A, Herrera JA, Soto JE, et al. Periodontitis is associated with preeclampsia in pregnant women. J Periodontol. 2006;77(2):182-188.

24. Dasanayake AP, Li Y, Wiener H, et al. Salivary Actinomyces naeslundii genospecies 2 and Lactobacillus casei levels predict pregnancy outcomes. J Periodontol. 2005;76(2):171-177.

25. McCreadie RG, Stevens H, Henderson J, et al. The dental health of people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(4):306-310.

26. Anttila S, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in relation to dental health behavior and self-perceived dental treatment need. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114(2):109-114.

27. Sjögren R, Nordström G. Oral health status of psychiatric patients. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9(4):632-638.

28. Ramon T, Grinshpoon A, Zusman SP, et al. Oral health and treatment needs of institutionalized chronic psychiatric patients in Israel. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(3):101-105.

29. Portilla MI, Mafla AC, Arteaga JJ. Periodontal status in female psychiatric patients. Colomb Med. 2009;40(2):167-176.

30. Navazesh M. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and Division of Science. How can oral health care providers determine if patients have dry mouth? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(5):613-620.

31. Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L, et al. Sjögren’s syndrome: the diagnostic potential of early oral manifestations preceding hyposalivation/xerostomia. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(1):1-6.

32. Spolarich AE. Managing the side effects of medications. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74(1):57-69.

33. Johnstone PA, Niemtzow RC, Riffenburgh RH. Acupuncture for xerostomia: clinical update. Cancer. 2002;94(4):1151-1156.

34. Garcia MK, Chiang JS, Cohen L, et al. Acupuncture for radiation-induced xerostomia in patients with cancer: a pilot study. Head Neck. 2009;31(10):1360-1368.

35. Strietzel FP, Lafaurie GI, Mendoza GR, et al. Efficacy and safety of an intraoral electrostimulation device for xerostomia relief: a multicenter, randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):180-190.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Xerostomia, commonly known as “dry mouth,” is a reported side effect of >1,800 drugs from >80 classes.1 This condition often goes unrecognized and untreated, but it can significantly affect patients’ quality of life and cause oral and medical health problems.2,3 Although psychotropic medications are not the only offenders, they comprise a large portion of the agents that can cause dry mouth. Antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, and alpha agonists can cause xerostomia.4 The risk of salivary hypofunction increases with polypharmacy and may be especially likely when ≥3 drugs are taken per day.5

Among all reported side effects of antidepressants and antipsychotics, dry mouth often is the most prevalent complaint. For example, in a study of 5 antidepressants 35% to 46% of patients reported dry mouth.6 Rates are similar in users of various antipsychotics. Patients with severe, persistent mental illness often cite side effects as the primary reason for psychotropic noncompliance.7-9

Few psychiatrists routinely screen patients for xerostomia, and if a patient reports this side effect, they may be unlikely to address it or understand its implications because of more pressing concerns such as psychosis or risk of suicide. Historically, education in general medical training about the effects of oral health on a patient’s overall health has been limited. It is crucial for psychiatrists to be aware of potential problems related to dry mouth and the impact it can have on their patients. In this article, we:

- describe how dry mouth can impact a patient’s oral, medical, and psychiatric health

- provide psychiatrists with an understanding of pathology related to xerostomia

- explain how psychiatrists can screen for xerostomia

- discuss the benefits patients may receive when psychiatrists collaborate with dental clinicians to manage this condition.

Implications of xerostomia

Saliva provides a protective function. It is an antimicrobial, buffering, and lubricating agent that aids cleansing and removal of food debris within the mouth. It also helps maintain oral mucosa and remineralizing of tooth structure.10

Psychotropics can affect the amount of saliva secreted and may alter the composition of saliva via their receptor affects on the dual sympathetic and parasympathetic innervations of the salivary glands.11 When the protective environment produced by saliva is altered, patients may start to develop oral problems before experiencing dryness. A 50% reduction in saliva flow may occur before they become aware of the problem.12,13

Patients may not taste food properly, experience cracked lips, or have trouble eating, oral pain, or dentures that no longer fit well.14 Additionally, oral diseases such as dental decay and periodontal disease (Photos 1 and 2), inflamed soft tissue, and candidiasis (Photo 3) also may occur.10,15 Patients may begin to notice dry mouth when they wake at night, which could disrupt sleep. Patients with xerostomia can accumulate excessive amounts of plaque on their teeth and the dorsum of the tongue. The increased bacterial count and release of volatile sulfide gases that occur with dry mouth may explain some cases of halitosis.16,17 Patients also may have difficulty swallowing or speaking and be unaware of the oral health destruction occurring as a result of reduced saliva. Some experts report oral bacteria levels can skyrocket as much as 10-fold in people who take medications that cause dry mouth.18

Infections of the mouth can create havoc elsewhere in the body. The evidence base that establishes an association between periodontal disease and other chronic inflammatory conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis is steadily growing.19-22 Periodontal disease also is a risk factor for preeclampsia and other illnesses that can negatively affect neonatal health.23,24

Failure to recognize xerostomia caused by psychotropic medications may lead to an increase in cavities, periodontal disease, and chronic systemic inflammatory conditions that can shorten a patient’s life span. Recognizing and treating causes of xerostomia is vital because doing so may halt this chain of events.

Photo 1

This patient complained of dry mouth and exhibits decay (a) and evidence of periodontal disease. Plaque and calculus is present (b), along with gingival recession from the loss of attachment and bone (c). This patient was taking venlafaxine, zolpidem, and alprazolam

Photo 2

Dental cavities were restored with tooth-colored restorations (arrows) on this patient, who has xerostomia. Every effort must be made to manage this patient’s dry mouth or the restorations may fail due to recurrent decay

Photo 3

This partial denture wearer, who complained of dry mouth, has evidence of palatal irritation and sores as a result of xerostomia and use of a partial denture. This patient was taking bupropion, esomeprazole, and tolterodine

Psychiatric patients’ oral health

Psychiatric patients’ oral health status often is poor. Several studies found that compared with the general population, patients who have severe, persistent mental illness are at higher risk to be missing teeth, schedule fewer visits to the dentist, and neglect oral hygiene.25-28 Periodontal disease also could be a problem in these patients.29 Although some evidence suggests mental illness may make patients less likely to go to the dentist, psychotropic medications also may contribute to their dental difficulties.

Screening for xerostomia

Simply advising patients of the problems related to xerostomia and asking several questions may help prevent pain and deterioration in function within the oral cavity (Table 1).14,30

You can perform a simple in-office assessment of the oral cavity by visual inspection and by placing a dry tongue blade against the inside of the cheek mucosa. If the blade sticks to the mucosa and a gentle tug is needed to lift it away, xerostomia may be present.30 Conversely, a healthy mouth will have a collection of saliva on the floor of the oral cavity, and pulling a tongue blade away from the inside of the cheek will not require any effort (Photos 4 and 5).

Table 1

Screening questions for xerostomia

| Does the amount of saliva in your mouth seem to have decreased? |

| Do you have any trouble swallowing, speaking, or eating dry foods? |

| Do you sip liquids more often to help you swallow? |

| Do you notice any dryness or cracking of your lips? |

| Do you have mouth sores or a burning feeling in the mouth? |

| When was the last time you saw your dentist? (Patients with xerostomia may need to see their dentist more frequently) |

| Are you aware of any halitosis (ie, mouth odor)? |

| Source: Reference 14 |

Photo 4

The arrow shows the normal appearance of saliva collecting on the floor of the mouth

Photo 5

This patient complained of dry mouth. Note the floor of the mouth is free of saliva (a). Decay is present (b), and the patient is missing posterior teeth (c). This patient was taking clonidine, metoprolol, hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, and irbesartan

Treatment options

Patients who have reduced salivary flow as a result of a medication may become so affected by dryness that their drug regimen may need to be changed. However, the greatest concern is for deteriorating oral health among patients who may be unaware xerostomia is occurring.31

Counsel patients who take medications that can affect their salivary function about the importance of seeing a dentist regularly, and provide referrals when appropriate. Depending upon the patient’s oral health, dentists recommend patients with xerostomia have their teeth cleaned/examined 3 or 4 times per year, rather than the 2 times per year allowed by third-party payers (ie, insurance companies). Also advise patients to be diligent in their oral hygiene practices, including flossing and brushing the teeth and tongue, and to avoid foods that are sticky and/or have high sucrose content (Table 2). Recommend using a toothpaste containing fluoride—preferably one free of sodium lauryl sulfate, which could contribute to mouth sores14—and drinking fluoridated water. Explain to patients that their dentist may recommend in-office high-fluoride applications, high-fluoride prescription toothpaste, and/or “mouth trays” that contain high fluoride gel. Tell patients to avoid cigarettes and caffeinated beverages, which can increase dryness. Alcohol use should be minimized and mouth rinses containing alcohol should not be used.

Many over-the-counter products are available to address xerostomia, including toothpastes, mouth rinses, and gels. Salivary substitutes—which are available as sprays, liquids, tablets, and swab sticks—imitate saliva and may provide a temporary reprieve from dryness. Although none of these products will cure dry mouth, they may help manage the condition. Advise patients to eat foods that stimulate saliva production, such as carrots, apples, and celery, and to chew sugarless gum and candies, which also will stimulate salivary flow.

The FDA has approved 2 prescription drugs for treating xerostomia: cevimeline and pilocarpine. Cevimeline is approved for treating dry mouth associated with Sjögren’s syndrome and pilocarpine is approved for treating dry mouth caused by head and neck radiation therapy; however, these medications’ role in treating dry mouth in psychiatric patients has not been investigated. Both agents are contraindicated in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma, uncontrolled asthma, or liver disease, and should be prescribed with caution for patients with cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory conditions, or kidney disease.32

Acupuncture and electrostimulation are being studied as a treatment for xerostomia. Trials have found acupuncture improves symptoms of xerostomia,33,34 and 1 study found electrostimulation improved xerostomia in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.35 Both approaches require more study to confirm their effectiveness.33-35

Table 2

Managing dry mouth: What to tell patients

| Oral hygiene. Tell patients to be diligent in their oral hygiene practices, including brushing and flossing. They should use a toothpaste containing fluoride—preferably one free of sodium lauryl sulfate—and schedule regular dental visits, where they can receive high-fluoride applications or be prescribed high-fluoride prescription toothpastes |

| Diet. Advise patients to avoid foods high in sucrose content, rinse their mouth with water soon after eating, and drink fluoridated water regularly. Tell them that they may be able to stimulate saliva flow with sugarless gum, candies, and foods such as celery and carrots |

| Drying agents. Instruct patients to avoid cigarettes, caffeinated beverages, and mouth rinses that contain alcohol. Explain that some patients may benefit from sleeping in a room with a cool air humidifier |

| Over-the-counter products. Suggest patients try salivary substitutes, which are dispensed in spray bottles, rinses, swish bottles, or oral swab sticks. In addition, products such as dry-mouth toothpaste and moisturizing gels also may help relieve their symptoms |

- Persson K, Axtelius B, Söderfeldt B, et al. Monitoring oral health and dental attendance in an outpatient psychiatric population. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16(3):263-271.

- Keene JJ Jr, Galasko GT, Land MF. Antidepressant use in psychiatry and medicine: importance for dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(1):71-79.

Drug Brand Names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amlodipine • Norvasc

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Cevimeline • Evoxac

- Clonidine • Catapres, Kapvay, others

- Esomeprazole • Nexium

- Irbesartan • Avapro

- Metoprolol • Lopressor, Toprol

- Pilocarpine • Salagen

- Tolterodine • Detrol

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Xerostomia, commonly known as “dry mouth,” is a reported side effect of >1,800 drugs from >80 classes.1 This condition often goes unrecognized and untreated, but it can significantly affect patients’ quality of life and cause oral and medical health problems.2,3 Although psychotropic medications are not the only offenders, they comprise a large portion of the agents that can cause dry mouth. Antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, and alpha agonists can cause xerostomia.4 The risk of salivary hypofunction increases with polypharmacy and may be especially likely when ≥3 drugs are taken per day.5

Among all reported side effects of antidepressants and antipsychotics, dry mouth often is the most prevalent complaint. For example, in a study of 5 antidepressants 35% to 46% of patients reported dry mouth.6 Rates are similar in users of various antipsychotics. Patients with severe, persistent mental illness often cite side effects as the primary reason for psychotropic noncompliance.7-9

Few psychiatrists routinely screen patients for xerostomia, and if a patient reports this side effect, they may be unlikely to address it or understand its implications because of more pressing concerns such as psychosis or risk of suicide. Historically, education in general medical training about the effects of oral health on a patient’s overall health has been limited. It is crucial for psychiatrists to be aware of potential problems related to dry mouth and the impact it can have on their patients. In this article, we:

- describe how dry mouth can impact a patient’s oral, medical, and psychiatric health

- provide psychiatrists with an understanding of pathology related to xerostomia

- explain how psychiatrists can screen for xerostomia

- discuss the benefits patients may receive when psychiatrists collaborate with dental clinicians to manage this condition.

Implications of xerostomia

Saliva provides a protective function. It is an antimicrobial, buffering, and lubricating agent that aids cleansing and removal of food debris within the mouth. It also helps maintain oral mucosa and remineralizing of tooth structure.10