User login

Even one vaccinated member can cut family’s COVID risk

The chances are reduced even further with each additional vaccinated or otherwise immune family member, according to new data.

Lead author Peter Nordström, MD, PhD, with the unit of geriatric medicine, Umeå (Sweden) University, said in an interview the message is important for public health: “When you vaccinate, you do not just protect yourself but also your relatives.”

The findings were published online on Oct. 11, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 1,789,728 individuals from 814,806 families from nationwide registries in Sweden. All individuals had acquired immunity either from previously being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or by being fully vaccinated (that is, having received two doses of the Moderna, Pfizer, or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines). Persons were considered for inclusion until May 26, 2021.

Each person with immunity was matched in a 1:1 ratio to a person without immunity from a cohort of individuals with families that had from two to five members. Families with more than five members were excluded because of small sample sizes.

Primarily nonimmune families in which there was one immune family member had a 45%-61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19 (hazard ratio, 0.39-0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.61; P < .001).

The risk reduction increased to 75%-86% when two family members were immune (HR, 0.14-0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.27; P < .001).

It increased to 91%-94% when three family members were immune (HR, 0.06-0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.10; P < .001) and to 97% with four immune family members (HR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.02-0.05; P < .001).

“The results were similar for the outcome of COVID-19 infection that was severe enough to warrant a hospital stay,” the authors wrote. They listed as an example that, in three-member families in which two members were immune, the remaining nonimmune family member had an 80% lower risk for hospitalization (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.43; P < .001).

Global implications

Dr. Nordström said the team used the family setting because it was more easily identifiable as a cohort with the national registries and because COVID-19 is spread among people in close contact with each other. The findings have implications for other groups that spend large amounts of time together and for herd immunity, he added.

The findings may be particularly welcome in regions of the world where vaccination rates are very low. The authors noted that most of the global population has not yet been vaccinated and that “it is anticipated that most of the population in low-income countries will be unable to receive a vaccine in 2021, with current vaccination rates suggesting that completely inoculating 70%-85% of the global population may take up to 5 years.”

Jill Foster, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said in an interview she agrees that the news could encourage countries that have very low vaccination rates.

This study may help motivate areas with few resources to start small, she said: “Even one is better than zero.”

She added that this news could also help ease the minds of families that have immunocompromised members or in which there are children who are too young to be vaccinated.

With these data, she said, people can see there’s something they can do to help protect a family member.

Dr. Foster said that although it’s intuitive to think that the more vaccinated people there are in a family, the safer people are, “it’s really nice to see the data coming out of such a large dataset.”

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study is that, at the time the study was conducted, the Delta variant was uncommon in Sweden. It is therefore unclear whether the findings regarding immunity are still relevant in Sweden and elsewhere now that the Delta strain is dominant.

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Foster has received grant support from Moderna.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The chances are reduced even further with each additional vaccinated or otherwise immune family member, according to new data.

Lead author Peter Nordström, MD, PhD, with the unit of geriatric medicine, Umeå (Sweden) University, said in an interview the message is important for public health: “When you vaccinate, you do not just protect yourself but also your relatives.”

The findings were published online on Oct. 11, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 1,789,728 individuals from 814,806 families from nationwide registries in Sweden. All individuals had acquired immunity either from previously being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or by being fully vaccinated (that is, having received two doses of the Moderna, Pfizer, or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines). Persons were considered for inclusion until May 26, 2021.

Each person with immunity was matched in a 1:1 ratio to a person without immunity from a cohort of individuals with families that had from two to five members. Families with more than five members were excluded because of small sample sizes.

Primarily nonimmune families in which there was one immune family member had a 45%-61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19 (hazard ratio, 0.39-0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.61; P < .001).

The risk reduction increased to 75%-86% when two family members were immune (HR, 0.14-0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.27; P < .001).

It increased to 91%-94% when three family members were immune (HR, 0.06-0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.10; P < .001) and to 97% with four immune family members (HR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.02-0.05; P < .001).

“The results were similar for the outcome of COVID-19 infection that was severe enough to warrant a hospital stay,” the authors wrote. They listed as an example that, in three-member families in which two members were immune, the remaining nonimmune family member had an 80% lower risk for hospitalization (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.43; P < .001).

Global implications

Dr. Nordström said the team used the family setting because it was more easily identifiable as a cohort with the national registries and because COVID-19 is spread among people in close contact with each other. The findings have implications for other groups that spend large amounts of time together and for herd immunity, he added.

The findings may be particularly welcome in regions of the world where vaccination rates are very low. The authors noted that most of the global population has not yet been vaccinated and that “it is anticipated that most of the population in low-income countries will be unable to receive a vaccine in 2021, with current vaccination rates suggesting that completely inoculating 70%-85% of the global population may take up to 5 years.”

Jill Foster, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said in an interview she agrees that the news could encourage countries that have very low vaccination rates.

This study may help motivate areas with few resources to start small, she said: “Even one is better than zero.”

She added that this news could also help ease the minds of families that have immunocompromised members or in which there are children who are too young to be vaccinated.

With these data, she said, people can see there’s something they can do to help protect a family member.

Dr. Foster said that although it’s intuitive to think that the more vaccinated people there are in a family, the safer people are, “it’s really nice to see the data coming out of such a large dataset.”

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study is that, at the time the study was conducted, the Delta variant was uncommon in Sweden. It is therefore unclear whether the findings regarding immunity are still relevant in Sweden and elsewhere now that the Delta strain is dominant.

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Foster has received grant support from Moderna.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The chances are reduced even further with each additional vaccinated or otherwise immune family member, according to new data.

Lead author Peter Nordström, MD, PhD, with the unit of geriatric medicine, Umeå (Sweden) University, said in an interview the message is important for public health: “When you vaccinate, you do not just protect yourself but also your relatives.”

The findings were published online on Oct. 11, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data from 1,789,728 individuals from 814,806 families from nationwide registries in Sweden. All individuals had acquired immunity either from previously being infected with SARS-CoV-2 or by being fully vaccinated (that is, having received two doses of the Moderna, Pfizer, or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines). Persons were considered for inclusion until May 26, 2021.

Each person with immunity was matched in a 1:1 ratio to a person without immunity from a cohort of individuals with families that had from two to five members. Families with more than five members were excluded because of small sample sizes.

Primarily nonimmune families in which there was one immune family member had a 45%-61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19 (hazard ratio, 0.39-0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.37-0.61; P < .001).

The risk reduction increased to 75%-86% when two family members were immune (HR, 0.14-0.25; 95% CI, 0.11-0.27; P < .001).

It increased to 91%-94% when three family members were immune (HR, 0.06-0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.10; P < .001) and to 97% with four immune family members (HR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.02-0.05; P < .001).

“The results were similar for the outcome of COVID-19 infection that was severe enough to warrant a hospital stay,” the authors wrote. They listed as an example that, in three-member families in which two members were immune, the remaining nonimmune family member had an 80% lower risk for hospitalization (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10-0.43; P < .001).

Global implications

Dr. Nordström said the team used the family setting because it was more easily identifiable as a cohort with the national registries and because COVID-19 is spread among people in close contact with each other. The findings have implications for other groups that spend large amounts of time together and for herd immunity, he added.

The findings may be particularly welcome in regions of the world where vaccination rates are very low. The authors noted that most of the global population has not yet been vaccinated and that “it is anticipated that most of the population in low-income countries will be unable to receive a vaccine in 2021, with current vaccination rates suggesting that completely inoculating 70%-85% of the global population may take up to 5 years.”

Jill Foster, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said in an interview she agrees that the news could encourage countries that have very low vaccination rates.

This study may help motivate areas with few resources to start small, she said: “Even one is better than zero.”

She added that this news could also help ease the minds of families that have immunocompromised members or in which there are children who are too young to be vaccinated.

With these data, she said, people can see there’s something they can do to help protect a family member.

Dr. Foster said that although it’s intuitive to think that the more vaccinated people there are in a family, the safer people are, “it’s really nice to see the data coming out of such a large dataset.”

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study is that, at the time the study was conducted, the Delta variant was uncommon in Sweden. It is therefore unclear whether the findings regarding immunity are still relevant in Sweden and elsewhere now that the Delta strain is dominant.

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Foster has received grant support from Moderna.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on respiratory infectious diseases in primary care practice

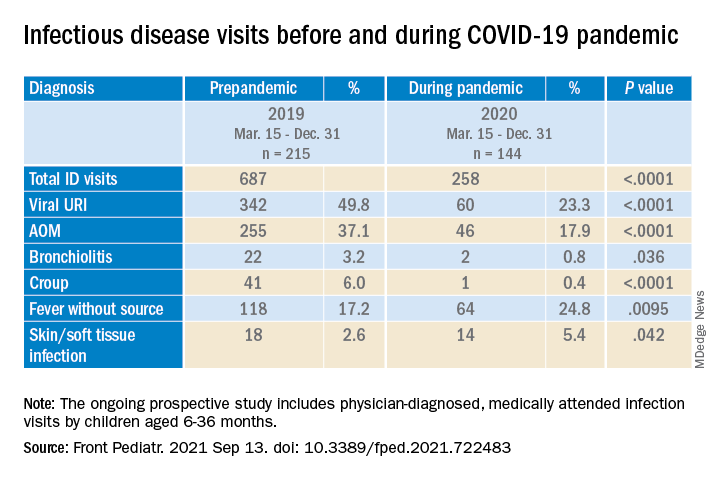

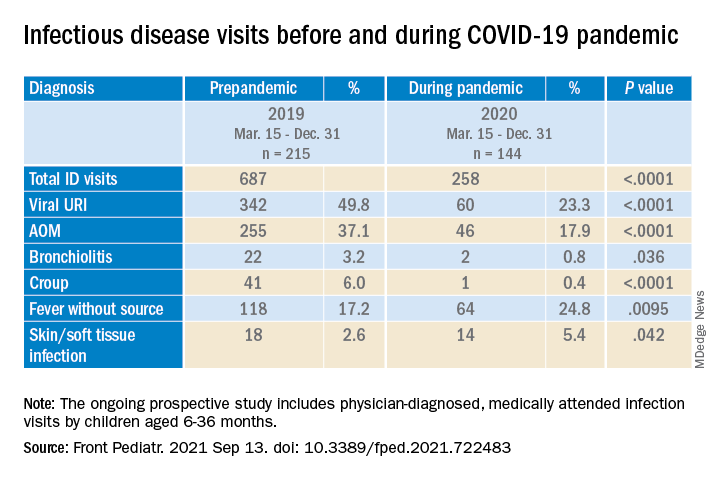

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

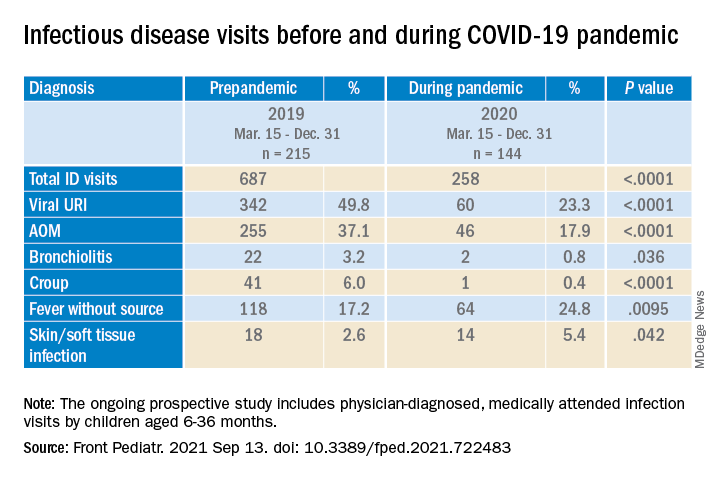

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

TB prevention in people with HIV: How short can we go?

A 3-month, 12-dose regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid (INH) was less toxic, had better compliance, and showed similar efficacy as 6 months of INH alone in preventing tuberculosis (TB) in people with HIV, according to the results of a clinical trial reported in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study, a randomized pragmatic trial in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Mozambique, was called WHIP3TB (Weekly High Dose Isoniazid and Rifapentine [P] Periodic Prophylaxis for TB).

Investigators randomized patients to three groups, comparing a 3-month course of weekly rifapentine-INH, given either once or repeated in a year, with daily isoniazid for 6 months. At 1 year, 90% of the rifapentine-INH group (3HP) were still on therapy, compared with only 50.5% in the INH group.

In the study, patients were initially assessed for TB using the World Health Organization four-symptom screen, but the sensitivity in HIV patients on antiretrovirals (ARVs) was only 53%. In addition to symptoms, screening at 12 months included a chest x-ray and sputum culture.

Of the 30 patients at month 12 with confirmed TB, 26 were asymptomatic, suggesting physicians should do further evaluation prior to initiating preventive TB treatment (which was not part of the WHO recommendation when the study was initiated).

Another unexpected finding was that 10.2% of the TB cases detected in the combined 3HP groups in South Africa, along with 18% of the cases in Mozambique, had rifampin resistance.

Investigator Gavin Churchyard, MBBCh, PhD, CEO of the Aurum Institute in Johannesburg, South Africa, said in an interview: “It appeared that taking this potent short course regimen – they’re just taking a single course – provided the same level of protection as taking repeat courses of the antibiotics. So that’s good news.” He noted, too, that TB transmission rates have been declining in sub-Saharan Africa because of ARV, and “so it may just be that a single course is now adequate because the risk of exposure and reinfection” is decreasing.

But Madhu Pai, MD, PhD, associate director, McGill International TB Centre, Montreal, who was not involved in the study, shared a more cautious interpretation. He said in an interview that the 2020 WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis state: “In settings with high TB transmission, adults and adolescents living with HIV ... should receive at least 36 months of daily isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) ... whether or not the person is on ART.” The problem is that almost no one can tolerate prolonged therapy with INH because of side effects, as has been shown in numerous studies.

For successful TB treatment, Dr. Pai said, “Even 3HP is not going to cut it; they’re going to get reinfected again. So that shortening of that 36 months is what this trial is really all about, in terms of new information ... and they were not successful.” But because this is still the most practical course, Dr. Pai suggests that follow-up monitoring for reinfection will be the most likely path forward.

Dr. Churchyard concluded: “If we wanted to end the global TB epidemic, we need to continue to find ways to further reduce the risk of TB overall at a population level, and then amongst high-risk groups such as people with HIV, including those on ARVs, and who have had a course of preventive therapy. ... We need to look for other strategies to further reduce that risk. Part of those strategies may be doing a more intensive screen. But also, it may be adding another intervention, particularly TB vaccines. ... No single intervention by itself will adequately address the risk of TB in people with HIV in these high TB transmission settings.”

Dr. Pai reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Churchyard has reported participation in a Sanofi advisory committee on the prevention of TB. Judy Stone, MD, is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 3-month, 12-dose regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid (INH) was less toxic, had better compliance, and showed similar efficacy as 6 months of INH alone in preventing tuberculosis (TB) in people with HIV, according to the results of a clinical trial reported in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study, a randomized pragmatic trial in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Mozambique, was called WHIP3TB (Weekly High Dose Isoniazid and Rifapentine [P] Periodic Prophylaxis for TB).

Investigators randomized patients to three groups, comparing a 3-month course of weekly rifapentine-INH, given either once or repeated in a year, with daily isoniazid for 6 months. At 1 year, 90% of the rifapentine-INH group (3HP) were still on therapy, compared with only 50.5% in the INH group.

In the study, patients were initially assessed for TB using the World Health Organization four-symptom screen, but the sensitivity in HIV patients on antiretrovirals (ARVs) was only 53%. In addition to symptoms, screening at 12 months included a chest x-ray and sputum culture.

Of the 30 patients at month 12 with confirmed TB, 26 were asymptomatic, suggesting physicians should do further evaluation prior to initiating preventive TB treatment (which was not part of the WHO recommendation when the study was initiated).

Another unexpected finding was that 10.2% of the TB cases detected in the combined 3HP groups in South Africa, along with 18% of the cases in Mozambique, had rifampin resistance.

Investigator Gavin Churchyard, MBBCh, PhD, CEO of the Aurum Institute in Johannesburg, South Africa, said in an interview: “It appeared that taking this potent short course regimen – they’re just taking a single course – provided the same level of protection as taking repeat courses of the antibiotics. So that’s good news.” He noted, too, that TB transmission rates have been declining in sub-Saharan Africa because of ARV, and “so it may just be that a single course is now adequate because the risk of exposure and reinfection” is decreasing.

But Madhu Pai, MD, PhD, associate director, McGill International TB Centre, Montreal, who was not involved in the study, shared a more cautious interpretation. He said in an interview that the 2020 WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis state: “In settings with high TB transmission, adults and adolescents living with HIV ... should receive at least 36 months of daily isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) ... whether or not the person is on ART.” The problem is that almost no one can tolerate prolonged therapy with INH because of side effects, as has been shown in numerous studies.

For successful TB treatment, Dr. Pai said, “Even 3HP is not going to cut it; they’re going to get reinfected again. So that shortening of that 36 months is what this trial is really all about, in terms of new information ... and they were not successful.” But because this is still the most practical course, Dr. Pai suggests that follow-up monitoring for reinfection will be the most likely path forward.

Dr. Churchyard concluded: “If we wanted to end the global TB epidemic, we need to continue to find ways to further reduce the risk of TB overall at a population level, and then amongst high-risk groups such as people with HIV, including those on ARVs, and who have had a course of preventive therapy. ... We need to look for other strategies to further reduce that risk. Part of those strategies may be doing a more intensive screen. But also, it may be adding another intervention, particularly TB vaccines. ... No single intervention by itself will adequately address the risk of TB in people with HIV in these high TB transmission settings.”

Dr. Pai reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Churchyard has reported participation in a Sanofi advisory committee on the prevention of TB. Judy Stone, MD, is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 3-month, 12-dose regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid (INH) was less toxic, had better compliance, and showed similar efficacy as 6 months of INH alone in preventing tuberculosis (TB) in people with HIV, according to the results of a clinical trial reported in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study, a randomized pragmatic trial in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Mozambique, was called WHIP3TB (Weekly High Dose Isoniazid and Rifapentine [P] Periodic Prophylaxis for TB).

Investigators randomized patients to three groups, comparing a 3-month course of weekly rifapentine-INH, given either once or repeated in a year, with daily isoniazid for 6 months. At 1 year, 90% of the rifapentine-INH group (3HP) were still on therapy, compared with only 50.5% in the INH group.

In the study, patients were initially assessed for TB using the World Health Organization four-symptom screen, but the sensitivity in HIV patients on antiretrovirals (ARVs) was only 53%. In addition to symptoms, screening at 12 months included a chest x-ray and sputum culture.

Of the 30 patients at month 12 with confirmed TB, 26 were asymptomatic, suggesting physicians should do further evaluation prior to initiating preventive TB treatment (which was not part of the WHO recommendation when the study was initiated).

Another unexpected finding was that 10.2% of the TB cases detected in the combined 3HP groups in South Africa, along with 18% of the cases in Mozambique, had rifampin resistance.

Investigator Gavin Churchyard, MBBCh, PhD, CEO of the Aurum Institute in Johannesburg, South Africa, said in an interview: “It appeared that taking this potent short course regimen – they’re just taking a single course – provided the same level of protection as taking repeat courses of the antibiotics. So that’s good news.” He noted, too, that TB transmission rates have been declining in sub-Saharan Africa because of ARV, and “so it may just be that a single course is now adequate because the risk of exposure and reinfection” is decreasing.

But Madhu Pai, MD, PhD, associate director, McGill International TB Centre, Montreal, who was not involved in the study, shared a more cautious interpretation. He said in an interview that the 2020 WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis state: “In settings with high TB transmission, adults and adolescents living with HIV ... should receive at least 36 months of daily isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) ... whether or not the person is on ART.” The problem is that almost no one can tolerate prolonged therapy with INH because of side effects, as has been shown in numerous studies.

For successful TB treatment, Dr. Pai said, “Even 3HP is not going to cut it; they’re going to get reinfected again. So that shortening of that 36 months is what this trial is really all about, in terms of new information ... and they were not successful.” But because this is still the most practical course, Dr. Pai suggests that follow-up monitoring for reinfection will be the most likely path forward.

Dr. Churchyard concluded: “If we wanted to end the global TB epidemic, we need to continue to find ways to further reduce the risk of TB overall at a population level, and then amongst high-risk groups such as people with HIV, including those on ARVs, and who have had a course of preventive therapy. ... We need to look for other strategies to further reduce that risk. Part of those strategies may be doing a more intensive screen. But also, it may be adding another intervention, particularly TB vaccines. ... No single intervention by itself will adequately address the risk of TB in people with HIV in these high TB transmission settings.”

Dr. Pai reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Churchyard has reported participation in a Sanofi advisory committee on the prevention of TB. Judy Stone, MD, is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vax campaign averted nearly 140,000 U.S. deaths through early May: Study

New York had 11.7 fewer COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 adults, and Hawaii had 1.1 fewer deaths per 10,000 than would have occurred without vaccinations, the study shows. The rest of the states fell somewhere in between, with the average state experiencing five fewer COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 adults.

At a national level, this means that instead of the 550,000 COVID-19 deaths that occurred by early May, there would have been 709,000 deaths in the absence of a vaccination campaign, according to the study.

Researchers from RAND and Indiana University created models to estimate the number of COVID-19 deaths that would have happened without vaccinations. The difference between the actual number of deaths and those estimates provides a measure of the number of COVID-19 deaths averted by the vaccination campaign.

Information about vaccine doses administered in each state came from the Bloomberg COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker, and data on COVID-19 deaths for each state came from The New York Times’ Coronavirus (COVID-19) Data in the United States database.

The study spanned the period from Dec. 21, 2020 to May 9, 2021. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its first emergency use authorization (EUA) for a COVID-19 vaccine to Pfizer/BioNTech on December 11, followed by an EUA for the Moderna vaccine on December 18 and one for Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine on Feb. 27, 2021.

Varied by state

There were wide variations in the speed and extent of the vaccination campaigns in various states, the researchers found. For example, West Virginia was the first state to reach 10 doses per 100 adults, reaching that goal on Jan. 16, 2021, and Idaho was the last state to hit that mark, on Feb. 4, 2021. Alaska was the first to reach 20 doses per 100 adults, on January 29, and Alabama was the last to do it, on February 21.

On May 6, California was the first state to administer 120 doses per 100 adults, but many states have still not reached that milestone.

The median number of days between the milestones of 10 and 20 doses per 100 adults was 19 days, and the median number of days between 20 and 40 doses per 100 adults was 24 days.

Hard to establish causality

The researchers emphasized that “establishment of causality is challenging” in comparing individual states’ vaccination levels with their COVID-19 mortality rates.

Aside from the study being observational, they pointed out, the analysis “relied on variation in the administration of COVID-19 vaccines across states … Vaccine administration patterns may be associated with declining mortality because of vaccine prevention of deaths and severe complications as state-level vaccine campaigns allocated initial doses to the highest-risk populations with the aim of immediately reducing COVID-19 deaths.”

Nevertheless, the authors note, “clinical trial evidence has shown that COVID-19 vaccines have high efficacy. Our study provides support for policies that further expand vaccine administration, which will enable larger populations to benefit.”

Study confirms vaccine benefit

Aaron Glatt, MD, chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, and a spokesman for the Infectious Disease Society of America, said in an interview that the study is important because it confirms the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination.

Regardless of whether the study’s results are statistically valid, he said, “I don’t think anyone can argue the benefit isn’t there. It’s a question of how important the benefit is.”

Dr. Glatt is not surprised that there are variations across states in the number of COVID-19 deaths averted through vaccination. “Clearly, in states where there was a lot of disease, a significant amount of vaccination is going to impact that tremendously.”

The authors note that their paper has some limitations. For one thing, they couldn’t determine what share of the estimated reduction in COVID-19 deaths was a result of the proportion of the population that was vaccinated or had antibodies and what share was a result of lower population-level risk for COVID-19 transmission.

Vaccination versus natural immunity

In addition, the researchers weren’t able to identify the roles of vaccination, natural immunity, and changes in mobility in the numbers of COVID-19 deaths.

Dr. Glatt says that’s understandable, since this was a retrospective study, and the researchers didn’t know how many people had been infected with COVID-19 at some point. Moreover, he adds, scientists don’t know how strong natural immunity from prior infection is, how long it endures, or how robust it is against new variants.

“It’s clear to me that there’s a benefit in preventing the second episode of COVID in people who had a first episode of COVID,” he said. “What we don’t know is how much that benefit is and how long it will last.”

The researchers also didn’t know how many people had gotten both doses of the Pfizer or the Moderna vaccine and how many of them had received only one. This is an important piece of information, Dr. Glatt said, but the lack of it doesn’t impair the study’s overall finding.

“Every vaccine potentially prevents death,” he stressed. “The more we vaccinate, the more deaths we’ll prevent. We’re starting to see increased vaccinations again. There were a million of them yesterday. So people are recognizing that COVID hasn’t gone away, and we need to vaccinate more people. The benefit from the vaccination hasn’t decreased. The more we vaccinate, the more the benefit will be.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York had 11.7 fewer COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 adults, and Hawaii had 1.1 fewer deaths per 10,000 than would have occurred without vaccinations, the study shows. The rest of the states fell somewhere in between, with the average state experiencing five fewer COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 adults.

At a national level, this means that instead of the 550,000 COVID-19 deaths that occurred by early May, there would have been 709,000 deaths in the absence of a vaccination campaign, according to the study.

Researchers from RAND and Indiana University created models to estimate the number of COVID-19 deaths that would have happened without vaccinations. The difference between the actual number of deaths and those estimates provides a measure of the number of COVID-19 deaths averted by the vaccination campaign.

Information about vaccine doses administered in each state came from the Bloomberg COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker, and data on COVID-19 deaths for each state came from The New York Times’ Coronavirus (COVID-19) Data in the United States database.

The study spanned the period from Dec. 21, 2020 to May 9, 2021. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its first emergency use authorization (EUA) for a COVID-19 vaccine to Pfizer/BioNTech on December 11, followed by an EUA for the Moderna vaccine on December 18 and one for Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine on Feb. 27, 2021.

Varied by state

There were wide variations in the speed and extent of the vaccination campaigns in various states, the researchers found. For example, West Virginia was the first state to reach 10 doses per 100 adults, reaching that goal on Jan. 16, 2021, and Idaho was the last state to hit that mark, on Feb. 4, 2021. Alaska was the first to reach 20 doses per 100 adults, on January 29, and Alabama was the last to do it, on February 21.

On May 6, California was the first state to administer 120 doses per 100 adults, but many states have still not reached that milestone.

The median number of days between the milestones of 10 and 20 doses per 100 adults was 19 days, and the median number of days between 20 and 40 doses per 100 adults was 24 days.

Hard to establish causality

The researchers emphasized that “establishment of causality is challenging” in comparing individual states’ vaccination levels with their COVID-19 mortality rates.

Aside from the study being observational, they pointed out, the analysis “relied on variation in the administration of COVID-19 vaccines across states … Vaccine administration patterns may be associated with declining mortality because of vaccine prevention of deaths and severe complications as state-level vaccine campaigns allocated initial doses to the highest-risk populations with the aim of immediately reducing COVID-19 deaths.”

Nevertheless, the authors note, “clinical trial evidence has shown that COVID-19 vaccines have high efficacy. Our study provides support for policies that further expand vaccine administration, which will enable larger populations to benefit.”

Study confirms vaccine benefit

Aaron Glatt, MD, chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, and a spokesman for the Infectious Disease Society of America, said in an interview that the study is important because it confirms the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination.

Regardless of whether the study’s results are statistically valid, he said, “I don’t think anyone can argue the benefit isn’t there. It’s a question of how important the benefit is.”

Dr. Glatt is not surprised that there are variations across states in the number of COVID-19 deaths averted through vaccination. “Clearly, in states where there was a lot of disease, a significant amount of vaccination is going to impact that tremendously.”

The authors note that their paper has some limitations. For one thing, they couldn’t determine what share of the estimated reduction in COVID-19 deaths was a result of the proportion of the population that was vaccinated or had antibodies and what share was a result of lower population-level risk for COVID-19 transmission.

Vaccination versus natural immunity

In addition, the researchers weren’t able to identify the roles of vaccination, natural immunity, and changes in mobility in the numbers of COVID-19 deaths.

Dr. Glatt says that’s understandable, since this was a retrospective study, and the researchers didn’t know how many people had been infected with COVID-19 at some point. Moreover, he adds, scientists don’t know how strong natural immunity from prior infection is, how long it endures, or how robust it is against new variants.

“It’s clear to me that there’s a benefit in preventing the second episode of COVID in people who had a first episode of COVID,” he said. “What we don’t know is how much that benefit is and how long it will last.”

The researchers also didn’t know how many people had gotten both doses of the Pfizer or the Moderna vaccine and how many of them had received only one. This is an important piece of information, Dr. Glatt said, but the lack of it doesn’t impair the study’s overall finding.

“Every vaccine potentially prevents death,” he stressed. “The more we vaccinate, the more deaths we’ll prevent. We’re starting to see increased vaccinations again. There were a million of them yesterday. So people are recognizing that COVID hasn’t gone away, and we need to vaccinate more people. The benefit from the vaccination hasn’t decreased. The more we vaccinate, the more the benefit will be.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York had 11.7 fewer COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 adults, and Hawaii had 1.1 fewer deaths per 10,000 than would have occurred without vaccinations, the study shows. The rest of the states fell somewhere in between, with the average state experiencing five fewer COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 adults.

At a national level, this means that instead of the 550,000 COVID-19 deaths that occurred by early May, there would have been 709,000 deaths in the absence of a vaccination campaign, according to the study.

Researchers from RAND and Indiana University created models to estimate the number of COVID-19 deaths that would have happened without vaccinations. The difference between the actual number of deaths and those estimates provides a measure of the number of COVID-19 deaths averted by the vaccination campaign.

Information about vaccine doses administered in each state came from the Bloomberg COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker, and data on COVID-19 deaths for each state came from The New York Times’ Coronavirus (COVID-19) Data in the United States database.

The study spanned the period from Dec. 21, 2020 to May 9, 2021. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its first emergency use authorization (EUA) for a COVID-19 vaccine to Pfizer/BioNTech on December 11, followed by an EUA for the Moderna vaccine on December 18 and one for Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine on Feb. 27, 2021.

Varied by state

There were wide variations in the speed and extent of the vaccination campaigns in various states, the researchers found. For example, West Virginia was the first state to reach 10 doses per 100 adults, reaching that goal on Jan. 16, 2021, and Idaho was the last state to hit that mark, on Feb. 4, 2021. Alaska was the first to reach 20 doses per 100 adults, on January 29, and Alabama was the last to do it, on February 21.

On May 6, California was the first state to administer 120 doses per 100 adults, but many states have still not reached that milestone.

The median number of days between the milestones of 10 and 20 doses per 100 adults was 19 days, and the median number of days between 20 and 40 doses per 100 adults was 24 days.

Hard to establish causality

The researchers emphasized that “establishment of causality is challenging” in comparing individual states’ vaccination levels with their COVID-19 mortality rates.

Aside from the study being observational, they pointed out, the analysis “relied on variation in the administration of COVID-19 vaccines across states … Vaccine administration patterns may be associated with declining mortality because of vaccine prevention of deaths and severe complications as state-level vaccine campaigns allocated initial doses to the highest-risk populations with the aim of immediately reducing COVID-19 deaths.”

Nevertheless, the authors note, “clinical trial evidence has shown that COVID-19 vaccines have high efficacy. Our study provides support for policies that further expand vaccine administration, which will enable larger populations to benefit.”

Study confirms vaccine benefit

Aaron Glatt, MD, chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, and a spokesman for the Infectious Disease Society of America, said in an interview that the study is important because it confirms the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination.

Regardless of whether the study’s results are statistically valid, he said, “I don’t think anyone can argue the benefit isn’t there. It’s a question of how important the benefit is.”

Dr. Glatt is not surprised that there are variations across states in the number of COVID-19 deaths averted through vaccination. “Clearly, in states where there was a lot of disease, a significant amount of vaccination is going to impact that tremendously.”

The authors note that their paper has some limitations. For one thing, they couldn’t determine what share of the estimated reduction in COVID-19 deaths was a result of the proportion of the population that was vaccinated or had antibodies and what share was a result of lower population-level risk for COVID-19 transmission.

Vaccination versus natural immunity

In addition, the researchers weren’t able to identify the roles of vaccination, natural immunity, and changes in mobility in the numbers of COVID-19 deaths.

Dr. Glatt says that’s understandable, since this was a retrospective study, and the researchers didn’t know how many people had been infected with COVID-19 at some point. Moreover, he adds, scientists don’t know how strong natural immunity from prior infection is, how long it endures, or how robust it is against new variants.

“It’s clear to me that there’s a benefit in preventing the second episode of COVID in people who had a first episode of COVID,” he said. “What we don’t know is how much that benefit is and how long it will last.”

The researchers also didn’t know how many people had gotten both doses of the Pfizer or the Moderna vaccine and how many of them had received only one. This is an important piece of information, Dr. Glatt said, but the lack of it doesn’t impair the study’s overall finding.

“Every vaccine potentially prevents death,” he stressed. “The more we vaccinate, the more deaths we’ll prevent. We’re starting to see increased vaccinations again. There were a million of them yesterday. So people are recognizing that COVID hasn’t gone away, and we need to vaccinate more people. The benefit from the vaccination hasn’t decreased. The more we vaccinate, the more the benefit will be.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 mitigation measures led to shifts in typical annual respiratory virus patterns

Nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as masking, staying home, limiting travel, and social distancing, have been doing more than reducing the risk for COVID-19. They’re also having an impact on infection rates and the timing of seasonal surges of other common respiratory diseases, according to an article published July 23 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Typically, respiratory pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), common cold coronaviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and respiratory adenoviruses increase in the fall and remain high throughout winter, following the same basic patterns as influenza. Although the historically low rates of influenza remained low into spring 2021, that’s not the case for several other common respiratory viruses.

“Clinicians should be aware of increases in some respiratory virus activity and remain vigilant for off-season increases,” wrote Sonja J. Olsen, PhD, and her colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She told this news organization that clinicians should use multipathogen testing to help guide treatment.

The authors also underscore the importance of fall influenza vaccination campaigns for anyone aged 6 months or older.

Timothy Brewer, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and of epidemiology at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, agreed that it’s important for health care professionals to consider off-season illnesses in their patients.

“Practitioners should be aware that if they see a sick child in the summer, outside of what normally might be influenza season, but they look like they have influenza, consider potentially influenza and test for it, because it might be possible that we may have disrupted that natural pattern,” Dr. Brewer told this news organization. Dr. Brewer, who was not involved in the CDC research, said it’s also “critically important” to encourage influenza vaccination as the season approaches.

The CDC researchers used the U.S. World Health Organization Collaborating Laboratories System and the CDC’s National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System to analyze virologic data from Oct. 3, 2020, to May 22, 2021, for influenza and Jan. 4, 2020, to May 22, 2021, for other respiratory viruses. The authors compared virus circulation during these periods to circulation during the same dates from four previous years.

Data to calculate influenza and RSV hospitalization rates came from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network and RSV Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

The authors report that flu activity dropped dramatically in March 2020 to its lowest levels since 1997, the earliest season for which data are available. Only 0.2% of more than 1 million specimens tested positive for influenza; the rate of hospitalizations for lab-confirmed flu was 0.8 per 100,000 people. Flu levels remained low through the summer, fall, and on to May 2021.

A potential drawback to this low activity, however, is a more prevalent and severe upcoming flu season, the authors write. The repeated exposure to flu viruses every year often “does not lead to illness, but it does serve to boost our immune response to influenza viruses,” Dr. Olsen said in an interview. “The absence of influenza viruses in the community over the last year means that we are not getting these regular boosts to our immune system. When we finally get exposed, our body may mount a weak response, and this could mean we develop a more clinically severe illness.”

Children are most susceptible to that phenomenon because they haven’t had a lifetime of exposure to flu viruses, Dr. Olsen said.

“An immunologically naive child may be more likely to develop a severe illness than someone who has lived through several influenza seasons,” she said. “This is why it is especially important for everyone 6 months and older to get vaccinated against influenza this season.”

Rhinovirus and enterovirus infections rebounded fairly quickly after their decline in March 2020 and started increasing in May 2020 until they reached “near prepandemic seasonal levels,” the authors write.

RSV infections dropped from 15.3% of weekly positive results in January 2020 to 1.4% by April and then stayed below 1% through the end of 2020. In past years, weekly positive results climbed to 3% in October and peaked at 12.5% to 16.7% in late December. Instead, RSV weekly positive results began increasing in April 2021, rising from 1.1% to 2.8% in May.

The “unusually timed” late spring increase in RSV “is probably associated with various nonpharmaceutical measures that have been in place but are now relaxing,” Dr. Olsen stated.

The RSV hospitalization rate was 0.3 per 100,000 people from October 2020 to April 2021, compared to 27.1 and 33.4 per 100,000 people in the previous 2 years. Of all RSV hospitalizations in the past year, 76.5% occurred in April-May 2021.

Rates of illness caused by the four common human coronaviruses (OC43, NL63, 229E, and HKU1) dropped from 7.5% of weekly positive results in January 2020 to 1.3% in April 2020 and stayed below 1% through February 2021. Then they climbed to 6.6% by May 2021. Infection rates of parainfluenza viruses types 1-4 similarly dropped from 2.6% in January 2020 to 1% in March 2020 and stayed below 1% until April 2021. Since then, rates of the common coronaviruses increased to 6.6% and parainfluenza viruses to 10.9% in May 2021.

Normally, parainfluenza viruses peak in October-November and May-June, so “the current increase could represent a return to prepandemic seasonality,” the authors write.

Human pneumoviruses’ weekly positive results initially increased from 4.2% in January 2020 to 7% in March and then fell to 1.9% the second week of April and remained below 1% through May 2021. In typical years, these viruses peak from 6.2% to 7.7% in March-April. Respiratory adenovirus activity similarly dropped to historically low levels in April 2021 and then began increasing to reach 3% by May 2021, the usual level for that month.

“The different circulation patterns observed across respiratory viruses probably also reflect differences in the virus transmission routes and how effective various nonpharmaceutical measures are at stopping transmission,” Dr. Olsen said in an interview. “As pandemic mitigation measures continue to be adjusted, we expect to see more changes in the circulation of these viruses, including a return to prepandemic circulation, as seen for rhinoviruses and enteroviruses.”

Rhinovirus and enterovirus rates dropped from 14.9% in March 2020 to 3.2% in May – lower than typical – and then climbed to a peak in October 2020. The peak (21.7% weekly positive results) was, however, still lower than the usual median of 32.8%. After dropping to 9.9% in January 2021, it then rose 19.1% in May, potentially reflecting “the usual spring peak that has occurred in previous years,” the authors write.

The authors note that it’s not yet clear how the COVID-19 pandemic and related mitigation measures will continue to affect respiratory virus circulation.

The authors hypothesize that the reasons for a seeming return to seasonal activity of respiratory adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, and enteroviruses could involve “different transmission mechanisms, the role of asymptomatic transmission, and prolonged survival of these nonenveloped viruses on surfaces, all of which might make these viruses less susceptible to nonpharmaceutical interventions.”

Dr. Brewer, of UCLA, agreed.

All the viruses basically “flatline except for adenoviruses and enteroviruses, and they behave a little differently in terms of how they spread,” he said. “Enteroviruses are much more likely to be fecal-oral spread than the other viruses [in the study].”

The delayed circulation of parainfluenza and human coronaviruses may have resulted from suspension of in-person classes through late winter 2020, they write, but that doesn’t explain the relative absence of pneumovirus activity, which usually affects the same young pediatric populations as RSV.

Dr. Brewer said California is seeing a surge of RSV right now, as are many states, especially throughout in the South. He’s not surprised by RSV’s deferred season, because those most affected – children younger than 2 years – are less likely to wear masks now and were “not going to daycare, not being out in public” in 2020. “As people are doing more activities, that’s probably why RSV has been starting to go up since April,” he said.

Despite the fact that, unlike many East Asian cultures, the United States has not traditionally been a mask-wearing culture, Dr. Brewer wouldn’t be surprised if more Americans begin wearing masks during flu season. “Hopefully another thing that will come out of this is better hand hygiene, with people just getting used to washing their hands more, particularly after they come home from being out,” he added.

Dr. Brewer similarly emphasized the importance of flu vaccination for the upcoming season, especially for younger children who may have poorer natural immunity to influenza, owing to its low circulation rates in 2020-2021.

The study was funded by the CDC. Dr. Brewer and Dr. Olsen have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as masking, staying home, limiting travel, and social distancing, have been doing more than reducing the risk for COVID-19. They’re also having an impact on infection rates and the timing of seasonal surges of other common respiratory diseases, according to an article published July 23 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Typically, respiratory pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), common cold coronaviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and respiratory adenoviruses increase in the fall and remain high throughout winter, following the same basic patterns as influenza. Although the historically low rates of influenza remained low into spring 2021, that’s not the case for several other common respiratory viruses.

“Clinicians should be aware of increases in some respiratory virus activity and remain vigilant for off-season increases,” wrote Sonja J. Olsen, PhD, and her colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She told this news organization that clinicians should use multipathogen testing to help guide treatment.

The authors also underscore the importance of fall influenza vaccination campaigns for anyone aged 6 months or older.

Timothy Brewer, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and of epidemiology at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, agreed that it’s important for health care professionals to consider off-season illnesses in their patients.

“Practitioners should be aware that if they see a sick child in the summer, outside of what normally might be influenza season, but they look like they have influenza, consider potentially influenza and test for it, because it might be possible that we may have disrupted that natural pattern,” Dr. Brewer told this news organization. Dr. Brewer, who was not involved in the CDC research, said it’s also “critically important” to encourage influenza vaccination as the season approaches.

The CDC researchers used the U.S. World Health Organization Collaborating Laboratories System and the CDC’s National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System to analyze virologic data from Oct. 3, 2020, to May 22, 2021, for influenza and Jan. 4, 2020, to May 22, 2021, for other respiratory viruses. The authors compared virus circulation during these periods to circulation during the same dates from four previous years.

Data to calculate influenza and RSV hospitalization rates came from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network and RSV Hospitalization Surveillance Network.

The authors report that flu activity dropped dramatically in March 2020 to its lowest levels since 1997, the earliest season for which data are available. Only 0.2% of more than 1 million specimens tested positive for influenza; the rate of hospitalizations for lab-confirmed flu was 0.8 per 100,000 people. Flu levels remained low through the summer, fall, and on to May 2021.

A potential drawback to this low activity, however, is a more prevalent and severe upcoming flu season, the authors write. The repeated exposure to flu viruses every year often “does not lead to illness, but it does serve to boost our immune response to influenza viruses,” Dr. Olsen said in an interview. “The absence of influenza viruses in the community over the last year means that we are not getting these regular boosts to our immune system. When we finally get exposed, our body may mount a weak response, and this could mean we develop a more clinically severe illness.”

Children are most susceptible to that phenomenon because they haven’t had a lifetime of exposure to flu viruses, Dr. Olsen said.

“An immunologically naive child may be more likely to develop a severe illness than someone who has lived through several influenza seasons,” she said. “This is why it is especially important for everyone 6 months and older to get vaccinated against influenza this season.”

Rhinovirus and enterovirus infections rebounded fairly quickly after their decline in March 2020 and started increasing in May 2020 until they reached “near prepandemic seasonal levels,” the authors write.

RSV infections dropped from 15.3% of weekly positive results in January 2020 to 1.4% by April and then stayed below 1% through the end of 2020. In past years, weekly positive results climbed to 3% in October and peaked at 12.5% to 16.7% in late December. Instead, RSV weekly positive results began increasing in April 2021, rising from 1.1% to 2.8% in May.

The “unusually timed” late spring increase in RSV “is probably associated with various nonpharmaceutical measures that have been in place but are now relaxing,” Dr. Olsen stated.

The RSV hospitalization rate was 0.3 per 100,000 people from October 2020 to April 2021, compared to 27.1 and 33.4 per 100,000 people in the previous 2 years. Of all RSV hospitalizations in the past year, 76.5% occurred in April-May 2021.

Rates of illness caused by the four common human coronaviruses (OC43, NL63, 229E, and HKU1) dropped from 7.5% of weekly positive results in January 2020 to 1.3% in April 2020 and stayed below 1% through February 2021. Then they climbed to 6.6% by May 2021. Infection rates of parainfluenza viruses types 1-4 similarly dropped from 2.6% in January 2020 to 1% in March 2020 and stayed below 1% until April 2021. Since then, rates of the common coronaviruses increased to 6.6% and parainfluenza viruses to 10.9% in May 2021.

Normally, parainfluenza viruses peak in October-November and May-June, so “the current increase could represent a return to prepandemic seasonality,” the authors write.

Human pneumoviruses’ weekly positive results initially increased from 4.2% in January 2020 to 7% in March and then fell to 1.9% the second week of April and remained below 1% through May 2021. In typical years, these viruses peak from 6.2% to 7.7% in March-April. Respiratory adenovirus activity similarly dropped to historically low levels in April 2021 and then began increasing to reach 3% by May 2021, the usual level for that month.

“The different circulation patterns observed across respiratory viruses probably also reflect differences in the virus transmission routes and how effective various nonpharmaceutical measures are at stopping transmission,” Dr. Olsen said in an interview. “As pandemic mitigation measures continue to be adjusted, we expect to see more changes in the circulation of these viruses, including a return to prepandemic circulation, as seen for rhinoviruses and enteroviruses.”

Rhinovirus and enterovirus rates dropped from 14.9% in March 2020 to 3.2% in May – lower than typical – and then climbed to a peak in October 2020. The peak (21.7% weekly positive results) was, however, still lower than the usual median of 32.8%. After dropping to 9.9% in January 2021, it then rose 19.1% in May, potentially reflecting “the usual spring peak that has occurred in previous years,” the authors write.

The authors note that it’s not yet clear how the COVID-19 pandemic and related mitigation measures will continue to affect respiratory virus circulation.

The authors hypothesize that the reasons for a seeming return to seasonal activity of respiratory adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, and enteroviruses could involve “different transmission mechanisms, the role of asymptomatic transmission, and prolonged survival of these nonenveloped viruses on surfaces, all of which might make these viruses less susceptible to nonpharmaceutical interventions.”

Dr. Brewer, of UCLA, agreed.