User login

Apply for BSN-JOBST Grant

The American Venous Forum Foundation will accept applications until Oct. 21 for the $100,000 BSN-JOBST Research Grant. The grant is for original, basic or clinical research in venous or lymphatic disease and provides $50,000 for each of two years. It is named after patient Conrad Jobst, who suffered from vascular disease and developed gradient compression garments to help relieve symptoms of venous disease.

The American Venous Forum Foundation will accept applications until Oct. 21 for the $100,000 BSN-JOBST Research Grant. The grant is for original, basic or clinical research in venous or lymphatic disease and provides $50,000 for each of two years. It is named after patient Conrad Jobst, who suffered from vascular disease and developed gradient compression garments to help relieve symptoms of venous disease.

The American Venous Forum Foundation will accept applications until Oct. 21 for the $100,000 BSN-JOBST Research Grant. The grant is for original, basic or clinical research in venous or lymphatic disease and provides $50,000 for each of two years. It is named after patient Conrad Jobst, who suffered from vascular disease and developed gradient compression garments to help relieve symptoms of venous disease.

Young Surgeons: K08, K23 Grants See Changes

The National Heart, Lung and Blood institute has extended the combined number of years of K training support from six to eight years for the K08 and K23 grants. Clinician scientists who have received either award can stay on a K12 or KL2 program for up to three years and then request a five-year individual K award. This will help support the transition from training to independent investigators for those clinicians.

The National Heart, Lung and Blood institute has extended the combined number of years of K training support from six to eight years for the K08 and K23 grants. Clinician scientists who have received either award can stay on a K12 or KL2 program for up to three years and then request a five-year individual K award. This will help support the transition from training to independent investigators for those clinicians.

The National Heart, Lung and Blood institute has extended the combined number of years of K training support from six to eight years for the K08 and K23 grants. Clinician scientists who have received either award can stay on a K12 or KL2 program for up to three years and then request a five-year individual K award. This will help support the transition from training to independent investigators for those clinicians.

New valve to treat emphysema-related hyperinflation demonstrates efficacy

PARIS – A patients with hyperinflation provides acceptable safety and clinically significant improvement in lung function at 12 months, according to results from a multicenter trial presented as a late-breaker at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Six-month results have been presented previously, but the 12-month results suggest that lung volume reduction associated with placement of the valves provides “durable effectiveness in appropriately selected hyperinflated emphysema patients,” according to Gerard Criner, MD, chair of the thoracic medicine department at Temple University, Philadelphia.

In this randomized controlled trial, called EMPROVE, 172 emphysema patients with severe dyspnea were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive a proprietary endobronchial valve or medical therapy alone. The valve, marketed under the brand name Spiration Valve System (SVS), is currently indicated for the treatment of air leaks after lung surgery.

“The valve serves to block airflow from edematous lungs with the objective of blocking hyperinflation and improving lung function,” Dr. Criner explained. The valves are retrievable, if necessary, with bronchoscopy.

High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was used to identify emphysema obstruction and target valve placement to the most diseased lobes. The average number of valves placed per patient was slightly less than four. Most of the valves (70%) were placed in an upper lobe.

When reported at 6 months, the responder rate, defined as at least 15% improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 36.8% and 10% in the SVS and control groups, respectively, a difference of 25.7% that Dr. Criner reported as statistically significant although he did not provide P values. At 12 months, the rates were 37.2% and 5.1%, respectively, demonstrating a persistent effect.

Thoracic adverse events were higher at both 6 months (31% vs. 11.9%) and 12 months (21.4% vs. 10.6%) in the treatment group relative to the control group. At 6 months, pneumothorax, which Dr. Criner characterized as “a recognized marker of target lobe volume reduction,” was the only event that occurred significantly more commonly (14.2% vs. 0%) in the SVS group.

Between 6 and 12 months, there were no pneumothorax events in either arm. The higher numerical rates of thoracic adverse events in the treatment arm were acute exacerbations (13.6% vs. 8.5%) and pneumonia in nontreated lobes (7.8% vs. 2.1%), but these rates were not statistically different.

At 6 months, there was a numerically higher rate of all-cause mortality in the treatment group (5.3% vs. 1.7%) but the rate was numerically lower between 6 and 12 months (2.9% vs. 6.4%). The differences were not significantly different at either time point or overall.

A significant reduction in hyperinflation favoring valve placement was accompanied by improvement in objective measures of lung function, such as FEV1, and dyspnea, as measured with the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale, at 6 and 12 months. These improvements translated into persistent quality of life benefits as measured with the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). At 12 months, the SGRQ changes from baseline were a 5.5-point reduction and a four-point gain in the treatment and control groups, respectively. This absolute difference of 9.5 points is slightly more modest than the 13-point difference at 6 months (–8 vs. +5 points), but demonstrates a durable effect, Dr. Criner reported.

According to Dr. Criner, EMPROVE reinforces the principle that HRCT is effective “for selecting the lobe for therapy and which patients may benefit,” but the most important message from the 12-month results is persistent clinical benefit.

The endobronchial values “provide statistically and clinically meaningful improvements in FEV1, reductions in lobe volume and dyspnea, and improvements in quality of life with an acceptable safety profile,” Dr. Criner reported.

On June 29, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first endobronchial valve for treatment of emphysema. This valve, marketed under the name Zephyr, was approved on the basis of the pivotal LIBERATE trial, also led by Dr. Criner and published earlier this year (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 May 22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0590OC.). The results of EMPROVE are consistent with previous evidence that a one-way valve, by preventing air from entering diseased lobes of patients with emphysema to exacerbate hyperinflation, improves lung function and reduces clinical symptoms.

Dr. Criner reports financial relationships with Olympus, the sponsor of this trial.

PARIS – A patients with hyperinflation provides acceptable safety and clinically significant improvement in lung function at 12 months, according to results from a multicenter trial presented as a late-breaker at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Six-month results have been presented previously, but the 12-month results suggest that lung volume reduction associated with placement of the valves provides “durable effectiveness in appropriately selected hyperinflated emphysema patients,” according to Gerard Criner, MD, chair of the thoracic medicine department at Temple University, Philadelphia.

In this randomized controlled trial, called EMPROVE, 172 emphysema patients with severe dyspnea were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive a proprietary endobronchial valve or medical therapy alone. The valve, marketed under the brand name Spiration Valve System (SVS), is currently indicated for the treatment of air leaks after lung surgery.

“The valve serves to block airflow from edematous lungs with the objective of blocking hyperinflation and improving lung function,” Dr. Criner explained. The valves are retrievable, if necessary, with bronchoscopy.

High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was used to identify emphysema obstruction and target valve placement to the most diseased lobes. The average number of valves placed per patient was slightly less than four. Most of the valves (70%) were placed in an upper lobe.

When reported at 6 months, the responder rate, defined as at least 15% improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 36.8% and 10% in the SVS and control groups, respectively, a difference of 25.7% that Dr. Criner reported as statistically significant although he did not provide P values. At 12 months, the rates were 37.2% and 5.1%, respectively, demonstrating a persistent effect.

Thoracic adverse events were higher at both 6 months (31% vs. 11.9%) and 12 months (21.4% vs. 10.6%) in the treatment group relative to the control group. At 6 months, pneumothorax, which Dr. Criner characterized as “a recognized marker of target lobe volume reduction,” was the only event that occurred significantly more commonly (14.2% vs. 0%) in the SVS group.

Between 6 and 12 months, there were no pneumothorax events in either arm. The higher numerical rates of thoracic adverse events in the treatment arm were acute exacerbations (13.6% vs. 8.5%) and pneumonia in nontreated lobes (7.8% vs. 2.1%), but these rates were not statistically different.

At 6 months, there was a numerically higher rate of all-cause mortality in the treatment group (5.3% vs. 1.7%) but the rate was numerically lower between 6 and 12 months (2.9% vs. 6.4%). The differences were not significantly different at either time point or overall.

A significant reduction in hyperinflation favoring valve placement was accompanied by improvement in objective measures of lung function, such as FEV1, and dyspnea, as measured with the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale, at 6 and 12 months. These improvements translated into persistent quality of life benefits as measured with the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). At 12 months, the SGRQ changes from baseline were a 5.5-point reduction and a four-point gain in the treatment and control groups, respectively. This absolute difference of 9.5 points is slightly more modest than the 13-point difference at 6 months (–8 vs. +5 points), but demonstrates a durable effect, Dr. Criner reported.

According to Dr. Criner, EMPROVE reinforces the principle that HRCT is effective “for selecting the lobe for therapy and which patients may benefit,” but the most important message from the 12-month results is persistent clinical benefit.

The endobronchial values “provide statistically and clinically meaningful improvements in FEV1, reductions in lobe volume and dyspnea, and improvements in quality of life with an acceptable safety profile,” Dr. Criner reported.

On June 29, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first endobronchial valve for treatment of emphysema. This valve, marketed under the name Zephyr, was approved on the basis of the pivotal LIBERATE trial, also led by Dr. Criner and published earlier this year (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 May 22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0590OC.). The results of EMPROVE are consistent with previous evidence that a one-way valve, by preventing air from entering diseased lobes of patients with emphysema to exacerbate hyperinflation, improves lung function and reduces clinical symptoms.

Dr. Criner reports financial relationships with Olympus, the sponsor of this trial.

PARIS – A patients with hyperinflation provides acceptable safety and clinically significant improvement in lung function at 12 months, according to results from a multicenter trial presented as a late-breaker at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Six-month results have been presented previously, but the 12-month results suggest that lung volume reduction associated with placement of the valves provides “durable effectiveness in appropriately selected hyperinflated emphysema patients,” according to Gerard Criner, MD, chair of the thoracic medicine department at Temple University, Philadelphia.

In this randomized controlled trial, called EMPROVE, 172 emphysema patients with severe dyspnea were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive a proprietary endobronchial valve or medical therapy alone. The valve, marketed under the brand name Spiration Valve System (SVS), is currently indicated for the treatment of air leaks after lung surgery.

“The valve serves to block airflow from edematous lungs with the objective of blocking hyperinflation and improving lung function,” Dr. Criner explained. The valves are retrievable, if necessary, with bronchoscopy.

High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was used to identify emphysema obstruction and target valve placement to the most diseased lobes. The average number of valves placed per patient was slightly less than four. Most of the valves (70%) were placed in an upper lobe.

When reported at 6 months, the responder rate, defined as at least 15% improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 36.8% and 10% in the SVS and control groups, respectively, a difference of 25.7% that Dr. Criner reported as statistically significant although he did not provide P values. At 12 months, the rates were 37.2% and 5.1%, respectively, demonstrating a persistent effect.

Thoracic adverse events were higher at both 6 months (31% vs. 11.9%) and 12 months (21.4% vs. 10.6%) in the treatment group relative to the control group. At 6 months, pneumothorax, which Dr. Criner characterized as “a recognized marker of target lobe volume reduction,” was the only event that occurred significantly more commonly (14.2% vs. 0%) in the SVS group.

Between 6 and 12 months, there were no pneumothorax events in either arm. The higher numerical rates of thoracic adverse events in the treatment arm were acute exacerbations (13.6% vs. 8.5%) and pneumonia in nontreated lobes (7.8% vs. 2.1%), but these rates were not statistically different.

At 6 months, there was a numerically higher rate of all-cause mortality in the treatment group (5.3% vs. 1.7%) but the rate was numerically lower between 6 and 12 months (2.9% vs. 6.4%). The differences were not significantly different at either time point or overall.

A significant reduction in hyperinflation favoring valve placement was accompanied by improvement in objective measures of lung function, such as FEV1, and dyspnea, as measured with the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale, at 6 and 12 months. These improvements translated into persistent quality of life benefits as measured with the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). At 12 months, the SGRQ changes from baseline were a 5.5-point reduction and a four-point gain in the treatment and control groups, respectively. This absolute difference of 9.5 points is slightly more modest than the 13-point difference at 6 months (–8 vs. +5 points), but demonstrates a durable effect, Dr. Criner reported.

According to Dr. Criner, EMPROVE reinforces the principle that HRCT is effective “for selecting the lobe for therapy and which patients may benefit,” but the most important message from the 12-month results is persistent clinical benefit.

The endobronchial values “provide statistically and clinically meaningful improvements in FEV1, reductions in lobe volume and dyspnea, and improvements in quality of life with an acceptable safety profile,” Dr. Criner reported.

On June 29, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first endobronchial valve for treatment of emphysema. This valve, marketed under the name Zephyr, was approved on the basis of the pivotal LIBERATE trial, also led by Dr. Criner and published earlier this year (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 May 22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0590OC.). The results of EMPROVE are consistent with previous evidence that a one-way valve, by preventing air from entering diseased lobes of patients with emphysema to exacerbate hyperinflation, improves lung function and reduces clinical symptoms.

Dr. Criner reports financial relationships with Olympus, the sponsor of this trial.

REPORTING FROM THE ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: A one-way valve developed for postoperative air leaks was found effective against emphysema-related hyperinflation.

Major finding: At 12 months, the FEV1 response rate (at least a 15% improvement) was observed in 37.2% of valve-treated patients and 5.1% of controls.

Study details: Randomized, multicenter trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Criner reports financial relationships with Olympus, the sponsor of this trial.

Source: European Respiratory Society 2018 International Congress.

New Updates to Afib Guidelines from CHEST

The American College of Chest Physicians® announced updates to the evidence-based guidelines on antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. The guideline panel submitted the manuscript, Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report, for publication in the journal CHEST®.

Key recommendations and shifts from previous guidelines include:

• For patients with atrial fibrillation without valvular heart disease, including those with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation who are at low risk of stroke (eg, CHA2DS2VASc score of 0 in males or 1 in females), we suggest no antithrombotic therapy.

• For patients with a single non-sex CHA2DS2VASc stroke risk factor, we suggest oral anticoagulation rather than no therapy, aspirin or combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.

• For those at high risk of stroke, we recommend oral anticoagulation rather than no therapy, aspirin or combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.

• Where we recommend or suggest in favor of oral anticoagulation, we suggest using a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) rather than adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist therapy. With the latter, it is important to aim for good quality anticoagulation control with a time in therapeutic range (TTR) >70%.

• Attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors should be made at each patient contact, and HAS-BLED score should be used to assess the risk of bleeding where high-risk patients (>=3) can be identified for earlier review and follow-up visits.

The complete guideline article is free to view in the Online First section of the journal CHEST.

The American College of Chest Physicians® announced updates to the evidence-based guidelines on antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. The guideline panel submitted the manuscript, Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report, for publication in the journal CHEST®.

Key recommendations and shifts from previous guidelines include:

• For patients with atrial fibrillation without valvular heart disease, including those with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation who are at low risk of stroke (eg, CHA2DS2VASc score of 0 in males or 1 in females), we suggest no antithrombotic therapy.

• For patients with a single non-sex CHA2DS2VASc stroke risk factor, we suggest oral anticoagulation rather than no therapy, aspirin or combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.

• For those at high risk of stroke, we recommend oral anticoagulation rather than no therapy, aspirin or combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.

• Where we recommend or suggest in favor of oral anticoagulation, we suggest using a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) rather than adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist therapy. With the latter, it is important to aim for good quality anticoagulation control with a time in therapeutic range (TTR) >70%.

• Attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors should be made at each patient contact, and HAS-BLED score should be used to assess the risk of bleeding where high-risk patients (>=3) can be identified for earlier review and follow-up visits.

The complete guideline article is free to view in the Online First section of the journal CHEST.

The American College of Chest Physicians® announced updates to the evidence-based guidelines on antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. The guideline panel submitted the manuscript, Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report, for publication in the journal CHEST®.

Key recommendations and shifts from previous guidelines include:

• For patients with atrial fibrillation without valvular heart disease, including those with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation who are at low risk of stroke (eg, CHA2DS2VASc score of 0 in males or 1 in females), we suggest no antithrombotic therapy.

• For patients with a single non-sex CHA2DS2VASc stroke risk factor, we suggest oral anticoagulation rather than no therapy, aspirin or combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.

• For those at high risk of stroke, we recommend oral anticoagulation rather than no therapy, aspirin or combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.

• Where we recommend or suggest in favor of oral anticoagulation, we suggest using a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) rather than adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist therapy. With the latter, it is important to aim for good quality anticoagulation control with a time in therapeutic range (TTR) >70%.

• Attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors should be made at each patient contact, and HAS-BLED score should be used to assess the risk of bleeding where high-risk patients (>=3) can be identified for earlier review and follow-up visits.

The complete guideline article is free to view in the Online First section of the journal CHEST.

ECMO for ARDS in the modern era

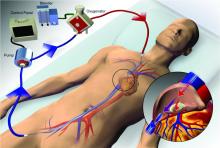

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has become increasingly accepted as a rescue therapy for severe respiratory failure from a variety of conditions, though most commonly, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Thiagarajan R, et al. ASAIO. 2017;63[1]:60). ECMO can provide respiratory or cardiorespiratory support for failing lungs, heart, or both. The most common ECMO configuration used in ARDS is venovenous ECMO, in which blood is withdrawn from a catheter placed in a central vein, pumped through a gas exchange device known as an oxygenator, and returned to the venous system via another catheter. The blood flowing through the oxygenator is separated from a continuous supply of oxygen-rich sweep gas by a semipermeable membrane, across which diffusion-mediated gas exchange occurs, so that the blood exiting it is rich in oxygen and low in carbon dioxide. As venovenous ECMO functions in series with the native circulation, the well-oxygenated blood exiting the ECMO circuit mixes with poorly oxygenated blood flowing through the lungs. Therefore, oxygenation is dependent on native cardiac output to achieve systemic oxygen delivery (Figure 1).

ECMO been used successfully in adults with ARDS since the early 1970s (Hill JD, et al. N Engl J Med. 1972;286[12]:629-34) but, until recently, was limited to small numbers of patients at select global centers and associated with a high-risk profile. In the last decade, however, driven by improvements in ECMO circuit components making the device safer and easier to use, encouraging worldwide experience during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic (Davies A, et al. JAMA. 2009;302[17]1888-95), and publication of the Efficacy and Economic Assessment of Conventional Ventilatory Support versus Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR) trial (Peek GJ, et al. Lancet. 2009;374[9698]:1351-63), ECMO use has markedly increased.

Despite its rapid growth, however, rigorous evidence supporting the use of ECMO has been lacking. The CESAR trial, while impressive in execution, had methodological issues that limited the strength of its conclusions. CESAR was a pragmatic trial that randomized 180 adults with severe respiratory failure from multiple etiologies to conventional management or transfer to an experienced, ECMO-capable center. CESAR met its primary outcome of improved survival without disability in the ECMO-referred group (63% vs 47%, relative risk [RR] 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.05 to 0.97, P=.03), but not all patients in that group ultimately received ECMO. In addition, the use of lung protective ventilation was significantly higher in the ECMO-referred group, making it difficult to separate its benefit from that of ECMO. A conservative interpretation is that CESAR showed the clinical benefit of treatment at an ECMO-capable center, experienced in the management of patients with severe respiratory failure.

Not until the release of the Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (EOLIA) trial earlier this year (Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378[21]:1965-75), did a modern, randomized controlled trial evaluating the use of ECMO itself exist. The EOLIA trial addressed the limitations of CESAR and randomized adult patients with early, severe ARDS to conventional, standard of care management that included a protocolized lung protective strategy in the control group vs immediate initiation of ECMO combined with an ultra-lung protective strategy (targeting end-inspiratory plateau pressure ≤24 cmH2O) in the intervention group. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 60 days. Of note, patients enrolled in EOLIA met entry criteria despite greater than 90% of patients receiving neuromuscular blockade and around 60% treated with prone positioning at the time of randomization (importantly, 90% of control group patients ultimately underwent prone positioning).

EOLIA was powered to detect a 20% decrease in mortality in the ECMO group. Based on trial design and the results of the fourth interim analysis, the trial was stopped for futility to reach that endpoint after enrollment of 249 of a maximum 331 patients. Although a 20% mortality reduction was not achieved, 60-day mortality was notably lower in the ECMO-treated group (35% vs 46%, RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.04, P=.09). The key secondary outcome of risk of treatment failure (defined as death in the ECMO group and death or crossover to ECMO in the control group) favored the ECMO group with a RR for mortality of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.47 to 0.82; P<.001), as did other secondary endpoints such as days free of renal and other organ failure.

A major limitation of the trial was that 35 (28%) of control group patients ultimately crossed over to ECMO, which diluted the effect of ECMO observed in the intention-to-treat analysis. Crossover occurred at clinician discretion an average of 6.5 days after randomization and after stringent criteria for crossover was met. These patients were incredibly ill, with a median oxygen saturation of 77%, rapidly worsening inotropic scores, and lactic acidosis; nine individuals had already suffered cardiac arrest, and six had received ECMO as part of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR), the initiation of venoarterial ECMO during cardiac arrest in attempt to restore spontaneous circulation. Mortality was considerably worse in the crossover group than in conventionally managed cohort overall, and, notably, 33% of patients crossed over to ECMO still survived.

In order to estimate the effect of ECMO on survival times if crossover had not occurred, the authors performed a post-hoc, rank-preserving structural failure time analysis. Though this relies on some assessment regarding the effect of the treatment itself, it showed a hazard ratio for mortality in the ECMO group of 0.51 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.02, P=.055). Although the EOLIA trial was not positive by traditional interpretation, all three major analyses and all secondary endpoints suggest some degree of benefit in patients with severe ARDS managed with ECMO.

Importantly, ECMO was well tolerated (at least when performed at expert centers, as done in this trial). There were significantly more bleeding events and cases of severe thrombocytopenia in the ECMO-treated group, but massive hemorrhage, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, arrhythmias, and other complications were similar.

Where do we go from here? Based on the totality of information, it is reasonable to consider ECMO for cases of severe ARDS not responsive to conventional measures, such as a lung protective ventilator strategy, neuromuscular blockade, and prone positioning. Initiation of ECMO may be reasonable prior to implementation of standard of care therapies, in order to permit safe transfer to an experienced center from a center not able to provide them.

Two take-away points: First, it is important to recognize that much of the clinical benefit derived from ECMO may be beyond its ability to normalize gas exchange and be due, at least in part, to the fact that ECMO allows the enhancement of proven lung protective ventilatory strategies. Initiation of ECMO and the “lung rest” it permits reduce the mechanical power applied to the injured alveoli and may attenuate ventilator-induced lung injury, cytokine release, and multiorgan failure that portend poor clinical outcomes in ARDS. Second, ECMO in EOLIA was conducted at expert centers with relatively low rates of complications.

It is too early to know how the critical care community will view ECMO for ARDS in light of EOLIA as well as a growing body of global ECMO experience, or how its wider application may impact the distribution and organization of ECMO centers. Regardless, of paramount importance in using ECMO as a treatment modality is optimizing patient management both prior to and after its initiation.

Dr. Agerstrand is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of the Medical ECMO Program, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has become increasingly accepted as a rescue therapy for severe respiratory failure from a variety of conditions, though most commonly, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Thiagarajan R, et al. ASAIO. 2017;63[1]:60). ECMO can provide respiratory or cardiorespiratory support for failing lungs, heart, or both. The most common ECMO configuration used in ARDS is venovenous ECMO, in which blood is withdrawn from a catheter placed in a central vein, pumped through a gas exchange device known as an oxygenator, and returned to the venous system via another catheter. The blood flowing through the oxygenator is separated from a continuous supply of oxygen-rich sweep gas by a semipermeable membrane, across which diffusion-mediated gas exchange occurs, so that the blood exiting it is rich in oxygen and low in carbon dioxide. As venovenous ECMO functions in series with the native circulation, the well-oxygenated blood exiting the ECMO circuit mixes with poorly oxygenated blood flowing through the lungs. Therefore, oxygenation is dependent on native cardiac output to achieve systemic oxygen delivery (Figure 1).

ECMO been used successfully in adults with ARDS since the early 1970s (Hill JD, et al. N Engl J Med. 1972;286[12]:629-34) but, until recently, was limited to small numbers of patients at select global centers and associated with a high-risk profile. In the last decade, however, driven by improvements in ECMO circuit components making the device safer and easier to use, encouraging worldwide experience during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic (Davies A, et al. JAMA. 2009;302[17]1888-95), and publication of the Efficacy and Economic Assessment of Conventional Ventilatory Support versus Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR) trial (Peek GJ, et al. Lancet. 2009;374[9698]:1351-63), ECMO use has markedly increased.

Despite its rapid growth, however, rigorous evidence supporting the use of ECMO has been lacking. The CESAR trial, while impressive in execution, had methodological issues that limited the strength of its conclusions. CESAR was a pragmatic trial that randomized 180 adults with severe respiratory failure from multiple etiologies to conventional management or transfer to an experienced, ECMO-capable center. CESAR met its primary outcome of improved survival without disability in the ECMO-referred group (63% vs 47%, relative risk [RR] 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.05 to 0.97, P=.03), but not all patients in that group ultimately received ECMO. In addition, the use of lung protective ventilation was significantly higher in the ECMO-referred group, making it difficult to separate its benefit from that of ECMO. A conservative interpretation is that CESAR showed the clinical benefit of treatment at an ECMO-capable center, experienced in the management of patients with severe respiratory failure.

Not until the release of the Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (EOLIA) trial earlier this year (Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378[21]:1965-75), did a modern, randomized controlled trial evaluating the use of ECMO itself exist. The EOLIA trial addressed the limitations of CESAR and randomized adult patients with early, severe ARDS to conventional, standard of care management that included a protocolized lung protective strategy in the control group vs immediate initiation of ECMO combined with an ultra-lung protective strategy (targeting end-inspiratory plateau pressure ≤24 cmH2O) in the intervention group. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 60 days. Of note, patients enrolled in EOLIA met entry criteria despite greater than 90% of patients receiving neuromuscular blockade and around 60% treated with prone positioning at the time of randomization (importantly, 90% of control group patients ultimately underwent prone positioning).

EOLIA was powered to detect a 20% decrease in mortality in the ECMO group. Based on trial design and the results of the fourth interim analysis, the trial was stopped for futility to reach that endpoint after enrollment of 249 of a maximum 331 patients. Although a 20% mortality reduction was not achieved, 60-day mortality was notably lower in the ECMO-treated group (35% vs 46%, RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.04, P=.09). The key secondary outcome of risk of treatment failure (defined as death in the ECMO group and death or crossover to ECMO in the control group) favored the ECMO group with a RR for mortality of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.47 to 0.82; P<.001), as did other secondary endpoints such as days free of renal and other organ failure.

A major limitation of the trial was that 35 (28%) of control group patients ultimately crossed over to ECMO, which diluted the effect of ECMO observed in the intention-to-treat analysis. Crossover occurred at clinician discretion an average of 6.5 days after randomization and after stringent criteria for crossover was met. These patients were incredibly ill, with a median oxygen saturation of 77%, rapidly worsening inotropic scores, and lactic acidosis; nine individuals had already suffered cardiac arrest, and six had received ECMO as part of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR), the initiation of venoarterial ECMO during cardiac arrest in attempt to restore spontaneous circulation. Mortality was considerably worse in the crossover group than in conventionally managed cohort overall, and, notably, 33% of patients crossed over to ECMO still survived.

In order to estimate the effect of ECMO on survival times if crossover had not occurred, the authors performed a post-hoc, rank-preserving structural failure time analysis. Though this relies on some assessment regarding the effect of the treatment itself, it showed a hazard ratio for mortality in the ECMO group of 0.51 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.02, P=.055). Although the EOLIA trial was not positive by traditional interpretation, all three major analyses and all secondary endpoints suggest some degree of benefit in patients with severe ARDS managed with ECMO.

Importantly, ECMO was well tolerated (at least when performed at expert centers, as done in this trial). There were significantly more bleeding events and cases of severe thrombocytopenia in the ECMO-treated group, but massive hemorrhage, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, arrhythmias, and other complications were similar.

Where do we go from here? Based on the totality of information, it is reasonable to consider ECMO for cases of severe ARDS not responsive to conventional measures, such as a lung protective ventilator strategy, neuromuscular blockade, and prone positioning. Initiation of ECMO may be reasonable prior to implementation of standard of care therapies, in order to permit safe transfer to an experienced center from a center not able to provide them.

Two take-away points: First, it is important to recognize that much of the clinical benefit derived from ECMO may be beyond its ability to normalize gas exchange and be due, at least in part, to the fact that ECMO allows the enhancement of proven lung protective ventilatory strategies. Initiation of ECMO and the “lung rest” it permits reduce the mechanical power applied to the injured alveoli and may attenuate ventilator-induced lung injury, cytokine release, and multiorgan failure that portend poor clinical outcomes in ARDS. Second, ECMO in EOLIA was conducted at expert centers with relatively low rates of complications.

It is too early to know how the critical care community will view ECMO for ARDS in light of EOLIA as well as a growing body of global ECMO experience, or how its wider application may impact the distribution and organization of ECMO centers. Regardless, of paramount importance in using ECMO as a treatment modality is optimizing patient management both prior to and after its initiation.

Dr. Agerstrand is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of the Medical ECMO Program, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has become increasingly accepted as a rescue therapy for severe respiratory failure from a variety of conditions, though most commonly, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Thiagarajan R, et al. ASAIO. 2017;63[1]:60). ECMO can provide respiratory or cardiorespiratory support for failing lungs, heart, or both. The most common ECMO configuration used in ARDS is venovenous ECMO, in which blood is withdrawn from a catheter placed in a central vein, pumped through a gas exchange device known as an oxygenator, and returned to the venous system via another catheter. The blood flowing through the oxygenator is separated from a continuous supply of oxygen-rich sweep gas by a semipermeable membrane, across which diffusion-mediated gas exchange occurs, so that the blood exiting it is rich in oxygen and low in carbon dioxide. As venovenous ECMO functions in series with the native circulation, the well-oxygenated blood exiting the ECMO circuit mixes with poorly oxygenated blood flowing through the lungs. Therefore, oxygenation is dependent on native cardiac output to achieve systemic oxygen delivery (Figure 1).

ECMO been used successfully in adults with ARDS since the early 1970s (Hill JD, et al. N Engl J Med. 1972;286[12]:629-34) but, until recently, was limited to small numbers of patients at select global centers and associated with a high-risk profile. In the last decade, however, driven by improvements in ECMO circuit components making the device safer and easier to use, encouraging worldwide experience during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic (Davies A, et al. JAMA. 2009;302[17]1888-95), and publication of the Efficacy and Economic Assessment of Conventional Ventilatory Support versus Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR) trial (Peek GJ, et al. Lancet. 2009;374[9698]:1351-63), ECMO use has markedly increased.

Despite its rapid growth, however, rigorous evidence supporting the use of ECMO has been lacking. The CESAR trial, while impressive in execution, had methodological issues that limited the strength of its conclusions. CESAR was a pragmatic trial that randomized 180 adults with severe respiratory failure from multiple etiologies to conventional management or transfer to an experienced, ECMO-capable center. CESAR met its primary outcome of improved survival without disability in the ECMO-referred group (63% vs 47%, relative risk [RR] 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.05 to 0.97, P=.03), but not all patients in that group ultimately received ECMO. In addition, the use of lung protective ventilation was significantly higher in the ECMO-referred group, making it difficult to separate its benefit from that of ECMO. A conservative interpretation is that CESAR showed the clinical benefit of treatment at an ECMO-capable center, experienced in the management of patients with severe respiratory failure.

Not until the release of the Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (EOLIA) trial earlier this year (Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378[21]:1965-75), did a modern, randomized controlled trial evaluating the use of ECMO itself exist. The EOLIA trial addressed the limitations of CESAR and randomized adult patients with early, severe ARDS to conventional, standard of care management that included a protocolized lung protective strategy in the control group vs immediate initiation of ECMO combined with an ultra-lung protective strategy (targeting end-inspiratory plateau pressure ≤24 cmH2O) in the intervention group. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 60 days. Of note, patients enrolled in EOLIA met entry criteria despite greater than 90% of patients receiving neuromuscular blockade and around 60% treated with prone positioning at the time of randomization (importantly, 90% of control group patients ultimately underwent prone positioning).

EOLIA was powered to detect a 20% decrease in mortality in the ECMO group. Based on trial design and the results of the fourth interim analysis, the trial was stopped for futility to reach that endpoint after enrollment of 249 of a maximum 331 patients. Although a 20% mortality reduction was not achieved, 60-day mortality was notably lower in the ECMO-treated group (35% vs 46%, RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.04, P=.09). The key secondary outcome of risk of treatment failure (defined as death in the ECMO group and death or crossover to ECMO in the control group) favored the ECMO group with a RR for mortality of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.47 to 0.82; P<.001), as did other secondary endpoints such as days free of renal and other organ failure.

A major limitation of the trial was that 35 (28%) of control group patients ultimately crossed over to ECMO, which diluted the effect of ECMO observed in the intention-to-treat analysis. Crossover occurred at clinician discretion an average of 6.5 days after randomization and after stringent criteria for crossover was met. These patients were incredibly ill, with a median oxygen saturation of 77%, rapidly worsening inotropic scores, and lactic acidosis; nine individuals had already suffered cardiac arrest, and six had received ECMO as part of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR), the initiation of venoarterial ECMO during cardiac arrest in attempt to restore spontaneous circulation. Mortality was considerably worse in the crossover group than in conventionally managed cohort overall, and, notably, 33% of patients crossed over to ECMO still survived.

In order to estimate the effect of ECMO on survival times if crossover had not occurred, the authors performed a post-hoc, rank-preserving structural failure time analysis. Though this relies on some assessment regarding the effect of the treatment itself, it showed a hazard ratio for mortality in the ECMO group of 0.51 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.02, P=.055). Although the EOLIA trial was not positive by traditional interpretation, all three major analyses and all secondary endpoints suggest some degree of benefit in patients with severe ARDS managed with ECMO.

Importantly, ECMO was well tolerated (at least when performed at expert centers, as done in this trial). There were significantly more bleeding events and cases of severe thrombocytopenia in the ECMO-treated group, but massive hemorrhage, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, arrhythmias, and other complications were similar.

Where do we go from here? Based on the totality of information, it is reasonable to consider ECMO for cases of severe ARDS not responsive to conventional measures, such as a lung protective ventilator strategy, neuromuscular blockade, and prone positioning. Initiation of ECMO may be reasonable prior to implementation of standard of care therapies, in order to permit safe transfer to an experienced center from a center not able to provide them.

Two take-away points: First, it is important to recognize that much of the clinical benefit derived from ECMO may be beyond its ability to normalize gas exchange and be due, at least in part, to the fact that ECMO allows the enhancement of proven lung protective ventilatory strategies. Initiation of ECMO and the “lung rest” it permits reduce the mechanical power applied to the injured alveoli and may attenuate ventilator-induced lung injury, cytokine release, and multiorgan failure that portend poor clinical outcomes in ARDS. Second, ECMO in EOLIA was conducted at expert centers with relatively low rates of complications.

It is too early to know how the critical care community will view ECMO for ARDS in light of EOLIA as well as a growing body of global ECMO experience, or how its wider application may impact the distribution and organization of ECMO centers. Regardless, of paramount importance in using ECMO as a treatment modality is optimizing patient management both prior to and after its initiation.

Dr. Agerstrand is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of the Medical ECMO Program, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

National Board of Echocardiography offering board exam

Due to significant interest in the pulmonary/critical care community, the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE) has opened registration for a board examination as a requirement for national level certification in advanced critical care echocardiography (ACCE). The examination has been developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners; CHEST and the other professional societies are well represented on the writing committee. The first examination is scheduled to be given on January 15, 2019.

The board of the NBE will be the final arbiter for other requirements for certification. We anticipate that these will be available in 2019.

A few essential questions about the certification:

1. Who will be eligible for certification in ACCE?

The policy of the NBE is that any licensed physician may take the examination. Passing the examination confers testamur status, which is only one of several requirements for certification. The board of the NBE will make the final decision as to how to define the clinical background of the candidate that will be required for certification.

2. What will be the requirements for demonstration of competence at image acquisition for ACCE?

Competence at ACCE requires that the intensivist be expert at image acquisition of a comprehensive image set. The board of the NBE will make the final decision as to what constitutes a full ACCE image set, how many studies must be performed by the candidate, and how the studies will be documented. Regarding the latter question, it is likely that there will be a need for identification of qualified mentors to guide the candidate through the process of demonstrating competence in image acquisition.

3. What resources exist to learn more about the examination?

For some suggestions regarding mastery of the cognitive base, Dr. Yonatan Greenstein has set up an independent website that has recommendations about study material and an example of the full ACCE image set (advancedcriticalcareecho.org). The NBE website has a list of subjects that will be covered in the examination. In addition to passing the examination, there will be other elements required for ACCE certification. The NBE has not yet made final decision on the additional requirements. As soon as they are available, they will be posted on the NBE website (echoboards.org).

There is keen interest amongst fellows and junior attendings in the NBE certification who are already competent in whole body ultrasonography. They see ACCE as a natural and necessary extension of their scope of practice, as a means of better helping their critically ill patients, and as a means of acquiring a unique skill that defines them as having a special skill compared with other intensivists. A smaller group of senior attending intensivists are primarily motivated by a well-defined practice-related need of skill at ACCE and/or a strong perception that knowledge of ACCE may directly improve their ability to care for the critically ill patient. Interest in certification extends across the various specialties that provide critical care services. The NBE has indicated that there has been a strong showing of registrations for the examination thus far.

We recommend that candidates for certification consider that passing the examination should be the priority. Collection of the image set may occur in parallel, as the two will complement each other. Preparation for the examination requires intensive study of the cognitive base of ACCE and mastery of image interpretation.

To aid in preparation for the ACCE examination, CHEST is offering a comprehensive review course, Advanced Critical Care Echocardiography Board Review Exam Course, being held at the CHEST Innovation, Simulation, and Training Center, December 7-8, 2018, in Glenview, Illinois.

Due to significant interest in the pulmonary/critical care community, the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE) has opened registration for a board examination as a requirement for national level certification in advanced critical care echocardiography (ACCE). The examination has been developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners; CHEST and the other professional societies are well represented on the writing committee. The first examination is scheduled to be given on January 15, 2019.

The board of the NBE will be the final arbiter for other requirements for certification. We anticipate that these will be available in 2019.

A few essential questions about the certification:

1. Who will be eligible for certification in ACCE?

The policy of the NBE is that any licensed physician may take the examination. Passing the examination confers testamur status, which is only one of several requirements for certification. The board of the NBE will make the final decision as to how to define the clinical background of the candidate that will be required for certification.

2. What will be the requirements for demonstration of competence at image acquisition for ACCE?

Competence at ACCE requires that the intensivist be expert at image acquisition of a comprehensive image set. The board of the NBE will make the final decision as to what constitutes a full ACCE image set, how many studies must be performed by the candidate, and how the studies will be documented. Regarding the latter question, it is likely that there will be a need for identification of qualified mentors to guide the candidate through the process of demonstrating competence in image acquisition.

3. What resources exist to learn more about the examination?

For some suggestions regarding mastery of the cognitive base, Dr. Yonatan Greenstein has set up an independent website that has recommendations about study material and an example of the full ACCE image set (advancedcriticalcareecho.org). The NBE website has a list of subjects that will be covered in the examination. In addition to passing the examination, there will be other elements required for ACCE certification. The NBE has not yet made final decision on the additional requirements. As soon as they are available, they will be posted on the NBE website (echoboards.org).

There is keen interest amongst fellows and junior attendings in the NBE certification who are already competent in whole body ultrasonography. They see ACCE as a natural and necessary extension of their scope of practice, as a means of better helping their critically ill patients, and as a means of acquiring a unique skill that defines them as having a special skill compared with other intensivists. A smaller group of senior attending intensivists are primarily motivated by a well-defined practice-related need of skill at ACCE and/or a strong perception that knowledge of ACCE may directly improve their ability to care for the critically ill patient. Interest in certification extends across the various specialties that provide critical care services. The NBE has indicated that there has been a strong showing of registrations for the examination thus far.

We recommend that candidates for certification consider that passing the examination should be the priority. Collection of the image set may occur in parallel, as the two will complement each other. Preparation for the examination requires intensive study of the cognitive base of ACCE and mastery of image interpretation.

To aid in preparation for the ACCE examination, CHEST is offering a comprehensive review course, Advanced Critical Care Echocardiography Board Review Exam Course, being held at the CHEST Innovation, Simulation, and Training Center, December 7-8, 2018, in Glenview, Illinois.

Due to significant interest in the pulmonary/critical care community, the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE) has opened registration for a board examination as a requirement for national level certification in advanced critical care echocardiography (ACCE). The examination has been developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners; CHEST and the other professional societies are well represented on the writing committee. The first examination is scheduled to be given on January 15, 2019.

The board of the NBE will be the final arbiter for other requirements for certification. We anticipate that these will be available in 2019.

A few essential questions about the certification:

1. Who will be eligible for certification in ACCE?

The policy of the NBE is that any licensed physician may take the examination. Passing the examination confers testamur status, which is only one of several requirements for certification. The board of the NBE will make the final decision as to how to define the clinical background of the candidate that will be required for certification.

2. What will be the requirements for demonstration of competence at image acquisition for ACCE?

Competence at ACCE requires that the intensivist be expert at image acquisition of a comprehensive image set. The board of the NBE will make the final decision as to what constitutes a full ACCE image set, how many studies must be performed by the candidate, and how the studies will be documented. Regarding the latter question, it is likely that there will be a need for identification of qualified mentors to guide the candidate through the process of demonstrating competence in image acquisition.

3. What resources exist to learn more about the examination?

For some suggestions regarding mastery of the cognitive base, Dr. Yonatan Greenstein has set up an independent website that has recommendations about study material and an example of the full ACCE image set (advancedcriticalcareecho.org). The NBE website has a list of subjects that will be covered in the examination. In addition to passing the examination, there will be other elements required for ACCE certification. The NBE has not yet made final decision on the additional requirements. As soon as they are available, they will be posted on the NBE website (echoboards.org).

There is keen interest amongst fellows and junior attendings in the NBE certification who are already competent in whole body ultrasonography. They see ACCE as a natural and necessary extension of their scope of practice, as a means of better helping their critically ill patients, and as a means of acquiring a unique skill that defines them as having a special skill compared with other intensivists. A smaller group of senior attending intensivists are primarily motivated by a well-defined practice-related need of skill at ACCE and/or a strong perception that knowledge of ACCE may directly improve their ability to care for the critically ill patient. Interest in certification extends across the various specialties that provide critical care services. The NBE has indicated that there has been a strong showing of registrations for the examination thus far.

We recommend that candidates for certification consider that passing the examination should be the priority. Collection of the image set may occur in parallel, as the two will complement each other. Preparation for the examination requires intensive study of the cognitive base of ACCE and mastery of image interpretation.

To aid in preparation for the ACCE examination, CHEST is offering a comprehensive review course, Advanced Critical Care Echocardiography Board Review Exam Course, being held at the CHEST Innovation, Simulation, and Training Center, December 7-8, 2018, in Glenview, Illinois.

This month in the journal CHEST®

Editor’s picks

Original Research

Pilot Feasibility Study in Establishing the Role of Ultrasound-Guided Pleural Biopsies in Pleural Infection (The AUDIO Study). By Dr. I. Psallidas, et al.

Commentary

Sleep Apnea Morbidity: A Consequence of Microbial-Immune Cross-Talk? By Dr. N. Farre, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease-Associated Cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. By Dr. S. S. Birring, et al.

Editor’s picks

Original Research

Pilot Feasibility Study in Establishing the Role of Ultrasound-Guided Pleural Biopsies in Pleural Infection (The AUDIO Study). By Dr. I. Psallidas, et al.

Commentary

Sleep Apnea Morbidity: A Consequence of Microbial-Immune Cross-Talk? By Dr. N. Farre, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease-Associated Cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. By Dr. S. S. Birring, et al.

Editor’s picks

Original Research

Pilot Feasibility Study in Establishing the Role of Ultrasound-Guided Pleural Biopsies in Pleural Infection (The AUDIO Study). By Dr. I. Psallidas, et al.

Commentary

Sleep Apnea Morbidity: A Consequence of Microbial-Immune Cross-Talk? By Dr. N. Farre, et al.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease-Associated Cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. By Dr. S. S. Birring, et al.

Upcoming CPT® Changes

Pulmonary, critical care, and sleep physicians often provide services to patients, as well as consultative services to other health-care professionals, without a patient being present. This can be done via telephone or electronic (internet or electronic health record) communications. Many are not aware that Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes were published to describe and define the work involved in these services. In 2019, there will be additional CPT codes available for health-care workers to use for these non-face-to-face services.

Telephone services are reported using CPT codes 99441-99443 and may be used for evaluation and management (E/M) services provided by telephone for an established patient that do not result in a patient visit within the next 24 hours or are associated with an E/M visit from the last 7 days.

99441 Telephone evaluation and management service by a physician or other qualified health-care professional who may report evaluation and management services provided to an established patient, parent, or guardian not originating from a related E/M serv ice provided within the previous 7 days nor leading to an E/M service or procedure within the next 24 hours or soonest available appointment; 5-10 minutes of medical discussion

99442 11-20 minutes of medical discussion

99443 21-30 minutes of medical discussion

These codes may not be reported by a provider more frequently than every 7 days. The details of the service should be documented in the medical record.

If the E/M service is prompted by an online patient request, then CPT code 99444 can be used.

99444 Online evaluation and management service provided by a physician or other qualified health care professional who may report evaluation and management services provided to an established patient or guardian, not originating from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days, using the internet or similar electronic communications network.

This code may be reported only every 7 days and can not be related to a previous E/M evaluation in the last 7 days or to a previous surgical procedure. The service includes all of the communication (eg, related telephone calls, prescription provision, laboratory orders) pertaining to the online patient encounter.

There are also CPT codes for Interprofessional Telephone/Internet/Electronic Health Record Consultations. These codes are used when one health-care provider requests the opinion and/or treatment advice of another provider (consultant) for either a new or established patient without face-to-face contact between the patient and the consultant.

99446 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician, including a verbal and written report to the patient’s treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional; 5-10 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review.

99447 11-20 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review

99448 21-30 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review

99449 31 minutes or more of medical consultative discussion and review

These codes are not used if the consultant has seen the patient in a face-to-face encounter within the last 14 days or the consultation results in a transfer of care or other face-to-face service with the consultant within the next 14 days. In addition, greater than 50% of the service time reported must be devoted to the medical consultative verbal or internet discussion. The request and reason for telephone/internet/electronic health record consultation by the requesting health-care professional should be documented in the patient’s medical record. After an oral report from the consultant is provided to the treating/requesting physician, a written report should be documented in the medical record. Consultations of less than 5 minutes should not be reported.

As noted, CPT codes 99446-49 require an oral and written report. A new code is added for 2019.

99451 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician, including a written report to the patient’s treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional, 5 minutes or more of medical consultative time.

CPT code 99451 describes a consultative service lasting more than 5 minutes and requires only a written report to the requesting physician. This was added recognizing that oral communications do not always occur between healthcare professionals and may facilitate consultative services in geographic areas with no specialists available.

99452 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record referral service(s) provided by a treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional, 30 minutes.

CPT code 99452 is reported for 16-30 minutes preparing for the referral and/or communicating with a consultant. If more than 30 minutes is spent by the treating/requesting healthcare provider, then one would use a prolonged services code (99358-59).

As with all coding and billing issues, review the CPT manual for parentheticals that describe coding rules not included in the code description. In addition, not all CPT codes are paid by all providers. Knowledge of payer policies is, therefore, important for appropriate reimbursement.

Pulmonary, critical care, and sleep physicians often provide services to patients, as well as consultative services to other health-care professionals, without a patient being present. This can be done via telephone or electronic (internet or electronic health record) communications. Many are not aware that Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes were published to describe and define the work involved in these services. In 2019, there will be additional CPT codes available for health-care workers to use for these non-face-to-face services.

Telephone services are reported using CPT codes 99441-99443 and may be used for evaluation and management (E/M) services provided by telephone for an established patient that do not result in a patient visit within the next 24 hours or are associated with an E/M visit from the last 7 days.

99441 Telephone evaluation and management service by a physician or other qualified health-care professional who may report evaluation and management services provided to an established patient, parent, or guardian not originating from a related E/M serv ice provided within the previous 7 days nor leading to an E/M service or procedure within the next 24 hours or soonest available appointment; 5-10 minutes of medical discussion

99442 11-20 minutes of medical discussion

99443 21-30 minutes of medical discussion

These codes may not be reported by a provider more frequently than every 7 days. The details of the service should be documented in the medical record.

If the E/M service is prompted by an online patient request, then CPT code 99444 can be used.

99444 Online evaluation and management service provided by a physician or other qualified health care professional who may report evaluation and management services provided to an established patient or guardian, not originating from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days, using the internet or similar electronic communications network.

This code may be reported only every 7 days and can not be related to a previous E/M evaluation in the last 7 days or to a previous surgical procedure. The service includes all of the communication (eg, related telephone calls, prescription provision, laboratory orders) pertaining to the online patient encounter.

There are also CPT codes for Interprofessional Telephone/Internet/Electronic Health Record Consultations. These codes are used when one health-care provider requests the opinion and/or treatment advice of another provider (consultant) for either a new or established patient without face-to-face contact between the patient and the consultant.

99446 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician, including a verbal and written report to the patient’s treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional; 5-10 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review.

99447 11-20 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review

99448 21-30 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review

99449 31 minutes or more of medical consultative discussion and review

These codes are not used if the consultant has seen the patient in a face-to-face encounter within the last 14 days or the consultation results in a transfer of care or other face-to-face service with the consultant within the next 14 days. In addition, greater than 50% of the service time reported must be devoted to the medical consultative verbal or internet discussion. The request and reason for telephone/internet/electronic health record consultation by the requesting health-care professional should be documented in the patient’s medical record. After an oral report from the consultant is provided to the treating/requesting physician, a written report should be documented in the medical record. Consultations of less than 5 minutes should not be reported.

As noted, CPT codes 99446-49 require an oral and written report. A new code is added for 2019.

99451 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician, including a written report to the patient’s treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional, 5 minutes or more of medical consultative time.

CPT code 99451 describes a consultative service lasting more than 5 minutes and requires only a written report to the requesting physician. This was added recognizing that oral communications do not always occur between healthcare professionals and may facilitate consultative services in geographic areas with no specialists available.

99452 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record referral service(s) provided by a treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional, 30 minutes.

CPT code 99452 is reported for 16-30 minutes preparing for the referral and/or communicating with a consultant. If more than 30 minutes is spent by the treating/requesting healthcare provider, then one would use a prolonged services code (99358-59).

As with all coding and billing issues, review the CPT manual for parentheticals that describe coding rules not included in the code description. In addition, not all CPT codes are paid by all providers. Knowledge of payer policies is, therefore, important for appropriate reimbursement.

Pulmonary, critical care, and sleep physicians often provide services to patients, as well as consultative services to other health-care professionals, without a patient being present. This can be done via telephone or electronic (internet or electronic health record) communications. Many are not aware that Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes were published to describe and define the work involved in these services. In 2019, there will be additional CPT codes available for health-care workers to use for these non-face-to-face services.

Telephone services are reported using CPT codes 99441-99443 and may be used for evaluation and management (E/M) services provided by telephone for an established patient that do not result in a patient visit within the next 24 hours or are associated with an E/M visit from the last 7 days.

99441 Telephone evaluation and management service by a physician or other qualified health-care professional who may report evaluation and management services provided to an established patient, parent, or guardian not originating from a related E/M serv ice provided within the previous 7 days nor leading to an E/M service or procedure within the next 24 hours or soonest available appointment; 5-10 minutes of medical discussion

99442 11-20 minutes of medical discussion

99443 21-30 minutes of medical discussion

These codes may not be reported by a provider more frequently than every 7 days. The details of the service should be documented in the medical record.

If the E/M service is prompted by an online patient request, then CPT code 99444 can be used.

99444 Online evaluation and management service provided by a physician or other qualified health care professional who may report evaluation and management services provided to an established patient or guardian, not originating from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days, using the internet or similar electronic communications network.

This code may be reported only every 7 days and can not be related to a previous E/M evaluation in the last 7 days or to a previous surgical procedure. The service includes all of the communication (eg, related telephone calls, prescription provision, laboratory orders) pertaining to the online patient encounter.

There are also CPT codes for Interprofessional Telephone/Internet/Electronic Health Record Consultations. These codes are used when one health-care provider requests the opinion and/or treatment advice of another provider (consultant) for either a new or established patient without face-to-face contact between the patient and the consultant.

99446 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician, including a verbal and written report to the patient’s treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional; 5-10 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review.

99447 11-20 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review

99448 21-30 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review

99449 31 minutes or more of medical consultative discussion and review

These codes are not used if the consultant has seen the patient in a face-to-face encounter within the last 14 days or the consultation results in a transfer of care or other face-to-face service with the consultant within the next 14 days. In addition, greater than 50% of the service time reported must be devoted to the medical consultative verbal or internet discussion. The request and reason for telephone/internet/electronic health record consultation by the requesting health-care professional should be documented in the patient’s medical record. After an oral report from the consultant is provided to the treating/requesting physician, a written report should be documented in the medical record. Consultations of less than 5 minutes should not be reported.

As noted, CPT codes 99446-49 require an oral and written report. A new code is added for 2019.

99451 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician, including a written report to the patient’s treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional, 5 minutes or more of medical consultative time.

CPT code 99451 describes a consultative service lasting more than 5 minutes and requires only a written report to the requesting physician. This was added recognizing that oral communications do not always occur between healthcare professionals and may facilitate consultative services in geographic areas with no specialists available.

99452 Interprofessional telephone/Internet/electronic health record referral service(s) provided by a treating/requesting physician or other qualified health care professional, 30 minutes.

CPT code 99452 is reported for 16-30 minutes preparing for the referral and/or communicating with a consultant. If more than 30 minutes is spent by the treating/requesting healthcare provider, then one would use a prolonged services code (99358-59).

As with all coding and billing issues, review the CPT manual for parentheticals that describe coding rules not included in the code description. In addition, not all CPT codes are paid by all providers. Knowledge of payer policies is, therefore, important for appropriate reimbursement.

Welcome Dr. Cowl!

As we greet our new CHEST President, Clayton T. Cowl, MD, MS, FCCP, we asked him for a few thoughts about his upcoming presidential year. He kindly offered these responses:

What would be one of the many things you would like to accomplish as President of CHEST?

We plan to increase the engagement of our membership, and, in do so, allow for more opportunities to serve in leadership roles, educate as faculty, or to participate in more of the wide array of educational opportunities within CHEST – whether the member is a long-tenured physician, a trainee, an earlier career researcher or educator, or a colleague in the care team, such as a respiratory therapist, advanced practice provider, or a pharmacist. CHEST has been and will continue to be a leader in delivery of education, and will further advance opportunities to present breaking research. Ultimately, the reason we are in medicine is to improve the care that we deliver to our patients, so it is incumbent upon us to keep the mission aimed toward “patient-centric” goals.

What do you consider to be the greatest strength of CHEST, and how will you build upon this during your Presidency?

Our greatest strength is our members, who bring a diversity of experience, expertise, and passion for what they do at the forefront. Together, with our incredibly talented and dedicated support staff at CHEST, as well as our industry and publishing partners, our organization is poised to bring medical education in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine globally to the next level. The CHEST Foundation has stimulated important opportunities for research, increased the ability for younger members to attend meetings and actively engage in CHEST activities, and provided valuable information to patients in a language they can understand. Thanks to advances in technology, there are improved platforms for communicating with our membership and for delivering education in novel and more effective ways than ever before. We plan to double down on our strategic focus of utilizing innovation and new technologies to lead trends in education, influence health-care improvements for our patients and their families, and to deliver the latest in medical education to clinicians and investigators worldwide.

What are some challenges facing CHEST, and how will you address these challenges?