User login

Smokers face higher infection risk after hernia operations

Jonah Stulberg, MD, FACS, is stickler about requiring patients to stop smoking at least 3 months before hernia surgery. He even uses urine tests to confirm whether they actually quit. A study by Dr. Stulberg and his colleagues supports this approach: .

The finding held up even after the researchers controlled for various factors. “Our findings are in agreement with other findings in higher risk surgeries, and they provide evidence that low-risk surgeries are not exempt from the risks associated with smoking,” said Dr. Stulberg in an interview. “Our data would suggest that there is significant clinical benefit to encouraging smoking cessation before elective hernia repair.”

The researchers launched the study to better understand how smoking affects complication rates in light of the fact that “surgeons in the U.S. tend to offer low-risk elective surgical procedures to patients who are actively smoking despite overwhelming evidence that smoking increases surgical risks,” Dr. Stulberg said.

The researchers tracked 220,629 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) database who underwent several types of elective hernia repair from 2011 to 2014.

Just over 18% of the patients said they’d smoked over the past year; they were more likely to be younger (median age, 50 for smokers vs. 57 for nonsmokers). Smokers also were more likely to be black, to be underweight, and to consume two or more alcoholic beverages per day (P less than .05).

The researchers tracked serious complications in the 30 days after surgery such as death, sepsis, and readmission.

Complications developed in 6.34% of smokers and 4.72% of nonsmokers (P less than .001). Numerous kinds of complications were more common in the smokers prior to adjustment: death, return to the operating room, readmission, and transfusion plus wound, pulmonary, thromboembolic and cardiac complications.

The researchers adjusted their statistics to account for factors such as ethnicity, sex, body mass index, preexisting comorbidities, and type of hernia operation. They found that risk of all complications was higher in smokers, compared with nonsmokers (odds ratio, 1.30) as were several other complications: death (OR, 1.53), return to operating room (OR, 1.23), readmission (OR, 1.24), wound complication (OR, 1.36), sepsis/septic shock (OR, 1.31), pulmonary complication (OR 1.77-2.30) and cardiac complication (OR, 1.27-1.43).

Only transfusion (OR, 0.90) and thromboembolic (OR, 0.87) complications were less likely in smokers.

The researchers noted that the statistics don’t allow them to analyze whether it makes any difference if smokers quit shortly before their procedures. Still, Dr. Stulberg stands by his you-must-quit-smoking-before-surgery edict. “I believe that their active smoking habit is a bigger health threat than their asymptomatic hernia, and therefore feel the right thing to do as their physician is support them through their smoking cessation,” he said. “I offer counseling and nicotine replacement if needed. I have very good quit rates and would encourage other surgeons to do the same.”

Dr. Stulberg noted that he can’t point to evidence supporting his requirement that patients quit at least 3 months before surgery. “Most data out there says the farther away from your last cigarette, the better,” he said. “But there isn’t any magic to 3 months, other than I believe it will lead to a higher likelihood of permanent cessation.”

Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Northwestern University funded the study. Four of the nine authors, including Dr. Stulberg, report various disclosures that are not directly related to the study, including funding from government agencies, physician organizations, Health Care Services Corporation and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, Mallinckrodt, and Northwestern University. The other authors report no disclosures.

SOURCE: DeLancey JO et al. Am J Surg. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.03.004.

Jonah Stulberg, MD, FACS, is stickler about requiring patients to stop smoking at least 3 months before hernia surgery. He even uses urine tests to confirm whether they actually quit. A study by Dr. Stulberg and his colleagues supports this approach: .

The finding held up even after the researchers controlled for various factors. “Our findings are in agreement with other findings in higher risk surgeries, and they provide evidence that low-risk surgeries are not exempt from the risks associated with smoking,” said Dr. Stulberg in an interview. “Our data would suggest that there is significant clinical benefit to encouraging smoking cessation before elective hernia repair.”

The researchers launched the study to better understand how smoking affects complication rates in light of the fact that “surgeons in the U.S. tend to offer low-risk elective surgical procedures to patients who are actively smoking despite overwhelming evidence that smoking increases surgical risks,” Dr. Stulberg said.

The researchers tracked 220,629 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) database who underwent several types of elective hernia repair from 2011 to 2014.

Just over 18% of the patients said they’d smoked over the past year; they were more likely to be younger (median age, 50 for smokers vs. 57 for nonsmokers). Smokers also were more likely to be black, to be underweight, and to consume two or more alcoholic beverages per day (P less than .05).

The researchers tracked serious complications in the 30 days after surgery such as death, sepsis, and readmission.

Complications developed in 6.34% of smokers and 4.72% of nonsmokers (P less than .001). Numerous kinds of complications were more common in the smokers prior to adjustment: death, return to the operating room, readmission, and transfusion plus wound, pulmonary, thromboembolic and cardiac complications.

The researchers adjusted their statistics to account for factors such as ethnicity, sex, body mass index, preexisting comorbidities, and type of hernia operation. They found that risk of all complications was higher in smokers, compared with nonsmokers (odds ratio, 1.30) as were several other complications: death (OR, 1.53), return to operating room (OR, 1.23), readmission (OR, 1.24), wound complication (OR, 1.36), sepsis/septic shock (OR, 1.31), pulmonary complication (OR 1.77-2.30) and cardiac complication (OR, 1.27-1.43).

Only transfusion (OR, 0.90) and thromboembolic (OR, 0.87) complications were less likely in smokers.

The researchers noted that the statistics don’t allow them to analyze whether it makes any difference if smokers quit shortly before their procedures. Still, Dr. Stulberg stands by his you-must-quit-smoking-before-surgery edict. “I believe that their active smoking habit is a bigger health threat than their asymptomatic hernia, and therefore feel the right thing to do as their physician is support them through their smoking cessation,” he said. “I offer counseling and nicotine replacement if needed. I have very good quit rates and would encourage other surgeons to do the same.”

Dr. Stulberg noted that he can’t point to evidence supporting his requirement that patients quit at least 3 months before surgery. “Most data out there says the farther away from your last cigarette, the better,” he said. “But there isn’t any magic to 3 months, other than I believe it will lead to a higher likelihood of permanent cessation.”

Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Northwestern University funded the study. Four of the nine authors, including Dr. Stulberg, report various disclosures that are not directly related to the study, including funding from government agencies, physician organizations, Health Care Services Corporation and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, Mallinckrodt, and Northwestern University. The other authors report no disclosures.

SOURCE: DeLancey JO et al. Am J Surg. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.03.004.

Jonah Stulberg, MD, FACS, is stickler about requiring patients to stop smoking at least 3 months before hernia surgery. He even uses urine tests to confirm whether they actually quit. A study by Dr. Stulberg and his colleagues supports this approach: .

The finding held up even after the researchers controlled for various factors. “Our findings are in agreement with other findings in higher risk surgeries, and they provide evidence that low-risk surgeries are not exempt from the risks associated with smoking,” said Dr. Stulberg in an interview. “Our data would suggest that there is significant clinical benefit to encouraging smoking cessation before elective hernia repair.”

The researchers launched the study to better understand how smoking affects complication rates in light of the fact that “surgeons in the U.S. tend to offer low-risk elective surgical procedures to patients who are actively smoking despite overwhelming evidence that smoking increases surgical risks,” Dr. Stulberg said.

The researchers tracked 220,629 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) database who underwent several types of elective hernia repair from 2011 to 2014.

Just over 18% of the patients said they’d smoked over the past year; they were more likely to be younger (median age, 50 for smokers vs. 57 for nonsmokers). Smokers also were more likely to be black, to be underweight, and to consume two or more alcoholic beverages per day (P less than .05).

The researchers tracked serious complications in the 30 days after surgery such as death, sepsis, and readmission.

Complications developed in 6.34% of smokers and 4.72% of nonsmokers (P less than .001). Numerous kinds of complications were more common in the smokers prior to adjustment: death, return to the operating room, readmission, and transfusion plus wound, pulmonary, thromboembolic and cardiac complications.

The researchers adjusted their statistics to account for factors such as ethnicity, sex, body mass index, preexisting comorbidities, and type of hernia operation. They found that risk of all complications was higher in smokers, compared with nonsmokers (odds ratio, 1.30) as were several other complications: death (OR, 1.53), return to operating room (OR, 1.23), readmission (OR, 1.24), wound complication (OR, 1.36), sepsis/septic shock (OR, 1.31), pulmonary complication (OR 1.77-2.30) and cardiac complication (OR, 1.27-1.43).

Only transfusion (OR, 0.90) and thromboembolic (OR, 0.87) complications were less likely in smokers.

The researchers noted that the statistics don’t allow them to analyze whether it makes any difference if smokers quit shortly before their procedures. Still, Dr. Stulberg stands by his you-must-quit-smoking-before-surgery edict. “I believe that their active smoking habit is a bigger health threat than their asymptomatic hernia, and therefore feel the right thing to do as their physician is support them through their smoking cessation,” he said. “I offer counseling and nicotine replacement if needed. I have very good quit rates and would encourage other surgeons to do the same.”

Dr. Stulberg noted that he can’t point to evidence supporting his requirement that patients quit at least 3 months before surgery. “Most data out there says the farther away from your last cigarette, the better,” he said. “But there isn’t any magic to 3 months, other than I believe it will lead to a higher likelihood of permanent cessation.”

Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Northwestern University funded the study. Four of the nine authors, including Dr. Stulberg, report various disclosures that are not directly related to the study, including funding from government agencies, physician organizations, Health Care Services Corporation and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, Mallinckrodt, and Northwestern University. The other authors report no disclosures.

SOURCE: DeLancey JO et al. Am J Surg. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.03.004.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Smokers are more likely than are nonsmokers to develop serious complications after elective hernia surgery.

Major finding: The adjusted risk of serious complications after elective hernia surgery is higher (odds ratio, 1.30) in smokers than nonsmokers.

Study details: Retrospective study of ACS NSQIP data on 220,629 patients in the United States (18% smokers) who underwent elective hernia operations during 2011-2014.

Disclosures: Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Northwestern University funded the study. Four of the nine authors reported various disclosures. The other authors report no disclosures.

Source: DeLancey JO et al. Am J Surg. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.03.004.

Bile spillage during lap cholecystectomy comes with a price

Bile spillage that happens during laparoscopic gallbladder removal is a known problem, but a large study has put some numbers to quantify the risks to patients.

A research team at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, conducted a prospective study of 1,001 such operations to look at the impact of bile spillage. They found that wound infection rates in cases involving bile spillage were almost three times higher than were those without spillage and resulting hospital stays were 50% longer, according to an article in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study involved adults who had laparoscopic and laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy at the academic hospital during May 2010-March 2017. The latter category accounted for 95 patients, a 9.5% conversion rate. Overall, bile was spilled in 591 patients (59%), with empyema in 86 (8.6%), hydrops in 62 (6.2%), and clear bile spillage in the remainder. Bile spillage along with gallstone spillage occurred in 202 patients (20.2%), with recovery of all spilled gallstones in 145 (71.8%) of those cases.

Overall, the surgical site infection (SSI) rate was 2.4% (n = 8) in patients with no bile spillage vs. 7.1% (n = 30) for those with bile spillage. Median hospital length of stay was 2 days for the nonspillage patients vs. 3 days for those with spillage. The 30-day readmission rates were 5.9% for the nonspillage group vs. 9.6% for the spillage group.

The bile spillage rate in this study was considerably higher than previous studies had reported, the researchers noted. A retrospective study of 1,127 patients reported a spillage rate of 11.6% (World J Surg. 1999;23:1186-90). “One needs to notice that a retrospective review of medical records almost certainly underappreciates the rate of bile spillage,” the investigators wrote. A Mayo Clinic study reported a bile spillage rate of 29% and an increased risk of intra-abdominal abscesses (J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:85-90). The complex and acute nature of the cases at Mass General may explain their higher spillage rates, the researchers suggested.

This study identifies bile spillage, along with conversion to open surgery and patient ASA class 2 or higher as the only independent predictors of SSI. The study also found no link between empyema and hydrops with SSI, although the small number of cases may preclude an representative sample.

Nonetheless, surgeons must face the question of how to decrease SSI in laparoscopic cholecystectomy with bile spillage, study authors wrote. “First, surgeons should acknowledge that gallbladder perforations and bile spillage come at a price,” they said, “and thus should be cautious and try to avoid them.”

When bile is spilled, liberal peritoneal irrigation may be futile; this study showed similar SSI rates after bile spillage, regardless of peritoneal irrigation. “We could consider modifying perioperative antibiotic coverage,” the investigators wrote, but they acknowledged a need for more research to validate its benefit.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peponis T et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.025.

Bile spillage that happens during laparoscopic gallbladder removal is a known problem, but a large study has put some numbers to quantify the risks to patients.

A research team at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, conducted a prospective study of 1,001 such operations to look at the impact of bile spillage. They found that wound infection rates in cases involving bile spillage were almost three times higher than were those without spillage and resulting hospital stays were 50% longer, according to an article in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study involved adults who had laparoscopic and laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy at the academic hospital during May 2010-March 2017. The latter category accounted for 95 patients, a 9.5% conversion rate. Overall, bile was spilled in 591 patients (59%), with empyema in 86 (8.6%), hydrops in 62 (6.2%), and clear bile spillage in the remainder. Bile spillage along with gallstone spillage occurred in 202 patients (20.2%), with recovery of all spilled gallstones in 145 (71.8%) of those cases.

Overall, the surgical site infection (SSI) rate was 2.4% (n = 8) in patients with no bile spillage vs. 7.1% (n = 30) for those with bile spillage. Median hospital length of stay was 2 days for the nonspillage patients vs. 3 days for those with spillage. The 30-day readmission rates were 5.9% for the nonspillage group vs. 9.6% for the spillage group.

The bile spillage rate in this study was considerably higher than previous studies had reported, the researchers noted. A retrospective study of 1,127 patients reported a spillage rate of 11.6% (World J Surg. 1999;23:1186-90). “One needs to notice that a retrospective review of medical records almost certainly underappreciates the rate of bile spillage,” the investigators wrote. A Mayo Clinic study reported a bile spillage rate of 29% and an increased risk of intra-abdominal abscesses (J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:85-90). The complex and acute nature of the cases at Mass General may explain their higher spillage rates, the researchers suggested.

This study identifies bile spillage, along with conversion to open surgery and patient ASA class 2 or higher as the only independent predictors of SSI. The study also found no link between empyema and hydrops with SSI, although the small number of cases may preclude an representative sample.

Nonetheless, surgeons must face the question of how to decrease SSI in laparoscopic cholecystectomy with bile spillage, study authors wrote. “First, surgeons should acknowledge that gallbladder perforations and bile spillage come at a price,” they said, “and thus should be cautious and try to avoid them.”

When bile is spilled, liberal peritoneal irrigation may be futile; this study showed similar SSI rates after bile spillage, regardless of peritoneal irrigation. “We could consider modifying perioperative antibiotic coverage,” the investigators wrote, but they acknowledged a need for more research to validate its benefit.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peponis T et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.025.

Bile spillage that happens during laparoscopic gallbladder removal is a known problem, but a large study has put some numbers to quantify the risks to patients.

A research team at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, conducted a prospective study of 1,001 such operations to look at the impact of bile spillage. They found that wound infection rates in cases involving bile spillage were almost three times higher than were those without spillage and resulting hospital stays were 50% longer, according to an article in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study involved adults who had laparoscopic and laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy at the academic hospital during May 2010-March 2017. The latter category accounted for 95 patients, a 9.5% conversion rate. Overall, bile was spilled in 591 patients (59%), with empyema in 86 (8.6%), hydrops in 62 (6.2%), and clear bile spillage in the remainder. Bile spillage along with gallstone spillage occurred in 202 patients (20.2%), with recovery of all spilled gallstones in 145 (71.8%) of those cases.

Overall, the surgical site infection (SSI) rate was 2.4% (n = 8) in patients with no bile spillage vs. 7.1% (n = 30) for those with bile spillage. Median hospital length of stay was 2 days for the nonspillage patients vs. 3 days for those with spillage. The 30-day readmission rates were 5.9% for the nonspillage group vs. 9.6% for the spillage group.

The bile spillage rate in this study was considerably higher than previous studies had reported, the researchers noted. A retrospective study of 1,127 patients reported a spillage rate of 11.6% (World J Surg. 1999;23:1186-90). “One needs to notice that a retrospective review of medical records almost certainly underappreciates the rate of bile spillage,” the investigators wrote. A Mayo Clinic study reported a bile spillage rate of 29% and an increased risk of intra-abdominal abscesses (J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:85-90). The complex and acute nature of the cases at Mass General may explain their higher spillage rates, the researchers suggested.

This study identifies bile spillage, along with conversion to open surgery and patient ASA class 2 or higher as the only independent predictors of SSI. The study also found no link between empyema and hydrops with SSI, although the small number of cases may preclude an representative sample.

Nonetheless, surgeons must face the question of how to decrease SSI in laparoscopic cholecystectomy with bile spillage, study authors wrote. “First, surgeons should acknowledge that gallbladder perforations and bile spillage come at a price,” they said, “and thus should be cautious and try to avoid them.”

When bile is spilled, liberal peritoneal irrigation may be futile; this study showed similar SSI rates after bile spillage, regardless of peritoneal irrigation. “We could consider modifying perioperative antibiotic coverage,” the investigators wrote, but they acknowledged a need for more research to validate its benefit.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peponis T et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.025.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Bile spillage during laparoscopic cholecystectomy increases the patient’s risk for surgical site infection.

Major finding: Surgical site infection rates were 7.1% in cases in which bile spillage occurred vs. 2.4% in cases that had no bile spillage.

Data source: Prospective analysis of 1,001 laparoscopic or laparoscopic converted to open operations in adults during May 2010-March 2017.

Disclosures: Dr. Velmahos and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Peponis T et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.025.

No clear winner in Pfannenstiel vs. vertical incision for high BMI cesareans

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Wound complication rates were similar with Pfannenstiel and vertical incisions in women with obesity.

Major finding: At 6 weeks, 21.1% of vertical incision recipients and 18.6% of Pfannenstiel recipients had wound complications.

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of 91 women with obesity receiving cesarean section.

Disclosures: Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

Prehospital antibiotics improved some aspects of sepsis care

SAN ANTONIO – according to results of a randomized trial.

Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel were able to recognize sepsis more quickly, obtain blood cultures, and give antibiotics after the training, reported investigator Prabath Nanayakkara, MD, PhD, FRCP, at the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Critical Care Congress.

At 28 days, 120 patients (8%) in the prehospital antibiotics group had died, compared with 93 patients (8%) in the usual care group (relative risk, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-1.24), according to the study’s results that were simultaneously published online in Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

The intervention group received antibiotics a median of 26 minutes prior to emergency department (ED) arrival. In the usual care group, median time to antibiotics after ED arrival was 70 minutes, versus 93 minutes prior to the sepsis recognition training (P = .142), the report further says.

“We do not advise prehospital antibiotics at the moment for patients with suspected sepsis,” Dr. Nanayakkara said, during his presentation at the conference.

Other countries might see different results, he cautioned.

In the Netherlands, ambulances reach the emergency scene within 15 minutes 93% of the time, and the average time from dispatch call to ED arrival is 40 minutes, Dr. Nanayakkara noted in the report.

“In part, due to the relatively short response times in the Netherlands, we don’t know if there are other countries with longer response times that would have other results, and whether they should use antibiotics in their ambulances,” Dr. Nanayakkara said in his presentation.

The study was the first-ever prospective randomized, controlled open-label trial to compare early prehospital antibiotics with standard care.

Before the study was started, EMS personnel at 10 large regional ambulance services serving 34 secondary or tertiary hospitals were trained in recognizing sepsis, the report says.

A total of 2,672 patients with suspected sepsis were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, of whom 1,535 were randomized to receive prehospital antibiotics and 1,137 to usual EMS care, which consisted of fluid resuscitation and supplementary oxygen.

The primary end point of the study was all-cause mortality at 28 days.

The negative mortality results of this trial are “not surprising,” given that the trial’s inclusion criteria allowed individuals with suspected infection but without organ dysfunction, said Jean-Louis Vincent, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Hospital, Brussels, in a related editorial appearing in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine (2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[17]30446-0).

Recent consensus definitions of sepsis recognize that sepsis is the association of an infection with some degree of organ dysfunction, according to Dr. Vincent.

“After this initial experience, I believe that a randomized, controlled trial could be done to assess the potential benefit of early antibiotic administration in the ambulance for patients with organ dysfunction associated with infection,” Dr. Vincent wrote in his editorial.

Dr. Nanayakkara and his coauthors declared no competing interests related to their study.

SOURCE: Alam N et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6(1):40-50.

SAN ANTONIO – according to results of a randomized trial.

Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel were able to recognize sepsis more quickly, obtain blood cultures, and give antibiotics after the training, reported investigator Prabath Nanayakkara, MD, PhD, FRCP, at the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Critical Care Congress.

At 28 days, 120 patients (8%) in the prehospital antibiotics group had died, compared with 93 patients (8%) in the usual care group (relative risk, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-1.24), according to the study’s results that were simultaneously published online in Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

The intervention group received antibiotics a median of 26 minutes prior to emergency department (ED) arrival. In the usual care group, median time to antibiotics after ED arrival was 70 minutes, versus 93 minutes prior to the sepsis recognition training (P = .142), the report further says.

“We do not advise prehospital antibiotics at the moment for patients with suspected sepsis,” Dr. Nanayakkara said, during his presentation at the conference.

Other countries might see different results, he cautioned.

In the Netherlands, ambulances reach the emergency scene within 15 minutes 93% of the time, and the average time from dispatch call to ED arrival is 40 minutes, Dr. Nanayakkara noted in the report.

“In part, due to the relatively short response times in the Netherlands, we don’t know if there are other countries with longer response times that would have other results, and whether they should use antibiotics in their ambulances,” Dr. Nanayakkara said in his presentation.

The study was the first-ever prospective randomized, controlled open-label trial to compare early prehospital antibiotics with standard care.

Before the study was started, EMS personnel at 10 large regional ambulance services serving 34 secondary or tertiary hospitals were trained in recognizing sepsis, the report says.

A total of 2,672 patients with suspected sepsis were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, of whom 1,535 were randomized to receive prehospital antibiotics and 1,137 to usual EMS care, which consisted of fluid resuscitation and supplementary oxygen.

The primary end point of the study was all-cause mortality at 28 days.

The negative mortality results of this trial are “not surprising,” given that the trial’s inclusion criteria allowed individuals with suspected infection but without organ dysfunction, said Jean-Louis Vincent, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Hospital, Brussels, in a related editorial appearing in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine (2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[17]30446-0).

Recent consensus definitions of sepsis recognize that sepsis is the association of an infection with some degree of organ dysfunction, according to Dr. Vincent.

“After this initial experience, I believe that a randomized, controlled trial could be done to assess the potential benefit of early antibiotic administration in the ambulance for patients with organ dysfunction associated with infection,” Dr. Vincent wrote in his editorial.

Dr. Nanayakkara and his coauthors declared no competing interests related to their study.

SOURCE: Alam N et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6(1):40-50.

SAN ANTONIO – according to results of a randomized trial.

Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel were able to recognize sepsis more quickly, obtain blood cultures, and give antibiotics after the training, reported investigator Prabath Nanayakkara, MD, PhD, FRCP, at the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Critical Care Congress.

At 28 days, 120 patients (8%) in the prehospital antibiotics group had died, compared with 93 patients (8%) in the usual care group (relative risk, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-1.24), according to the study’s results that were simultaneously published online in Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

The intervention group received antibiotics a median of 26 minutes prior to emergency department (ED) arrival. In the usual care group, median time to antibiotics after ED arrival was 70 minutes, versus 93 minutes prior to the sepsis recognition training (P = .142), the report further says.

“We do not advise prehospital antibiotics at the moment for patients with suspected sepsis,” Dr. Nanayakkara said, during his presentation at the conference.

Other countries might see different results, he cautioned.

In the Netherlands, ambulances reach the emergency scene within 15 minutes 93% of the time, and the average time from dispatch call to ED arrival is 40 minutes, Dr. Nanayakkara noted in the report.

“In part, due to the relatively short response times in the Netherlands, we don’t know if there are other countries with longer response times that would have other results, and whether they should use antibiotics in their ambulances,” Dr. Nanayakkara said in his presentation.

The study was the first-ever prospective randomized, controlled open-label trial to compare early prehospital antibiotics with standard care.

Before the study was started, EMS personnel at 10 large regional ambulance services serving 34 secondary or tertiary hospitals were trained in recognizing sepsis, the report says.

A total of 2,672 patients with suspected sepsis were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, of whom 1,535 were randomized to receive prehospital antibiotics and 1,137 to usual EMS care, which consisted of fluid resuscitation and supplementary oxygen.

The primary end point of the study was all-cause mortality at 28 days.

The negative mortality results of this trial are “not surprising,” given that the trial’s inclusion criteria allowed individuals with suspected infection but without organ dysfunction, said Jean-Louis Vincent, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Hospital, Brussels, in a related editorial appearing in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine (2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[17]30446-0).

Recent consensus definitions of sepsis recognize that sepsis is the association of an infection with some degree of organ dysfunction, according to Dr. Vincent.

“After this initial experience, I believe that a randomized, controlled trial could be done to assess the potential benefit of early antibiotic administration in the ambulance for patients with organ dysfunction associated with infection,” Dr. Vincent wrote in his editorial.

Dr. Nanayakkara and his coauthors declared no competing interests related to their study.

SOURCE: Alam N et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6(1):40-50.

REPORTING FROM CCC47

Key clinical point: In patients with suspected sepsis, prehospital antibiotics delivered by EMS personnel improved some aspects of care, but did not reduce mortality.

Major finding: At 28 days, 120 patients (8%) in the prehospital antibiotics group had died, compared with 93 patients (8%) in the usual care group (relative risk, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.74-1.24).

Data source: Intention-to-treat analysis of 2,672 patients in a prospective randomized, controlled open-label trial comparing early prehospital antibiotics to standard care.

Disclosures: The study authors declared no competing interests related to the study.

Source: Alam N et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Jan;6(1):40-50.

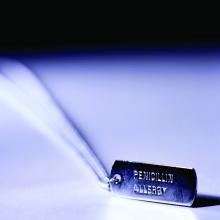

Preoperative penicillin allergy tests could decrease SSI

Patients with reported penicillin allergies are significantly more likely to develop surgical site infections, according to a study conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

With new evidence reporting 90%-99% of patients with a reported allergy are not actually allergic, conducting a preoperative allergy test could improve treatment choice and decrease the risk of SSI, as well as the notable financial burden associated with it. Thus, “systematic, preoperative penicillin allergy evaluations in surgical patients may not only improve antibiotic choice but also decrease SSI risk,” according to Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, the quality director for the department of allergy and immunology at Massachusetts General Hospital, and her fellow investigators.

Surgeries performed were hip arthroplasty, knee arthroplasty, hysterectomy, colon surgery, or coronary artery bypass grafting.

Of the patients studied, 922 (11%) reported a penicillin allergy; most had minor reactions, such as rashes (37.5%) or urticaria (18%). “Only 5 reactions to penicillin represented contraindications to receiving a beta-lactam; the vast majority of patients would have tolerated first-line recommended cephalosporin prophylaxis had allergy evaluation been pursued,“ according to Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues.

Overall, a total of 241 (2.7%) patients contracted an SSI. In a multivariate analysis, patients who had reported a penicillin allergy were 50% more likely to develop an SSI than those who had no reported allergy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.5; P = .04).

Risk may even be higher than 50% in the general health care population because this health center has a relatively low rate of SSIs, compared with many other hospitals, Dr. Blumenthal and her fellow investigators stated.

The increased risk primarily concerns the treatment used because those with a reported allergy were more likely than those without the allergy to be given clindamycin (48.8% vs. 3.1%, respectively), vancomycin (34.7% vs. 3.3%), gentamicin (24% vs. 2.8%), or fluoroquinolones (6.8% vs. 1.3%) instead of the most commonly used antibiotic, cefazolin (12.2% vs. 92.4%).

Patients given antibiotics other than cefazolin were usually given treatment outside of the perioperative window, which could severely increase the likelihood for developing an SSI, according to investigators. Of patients given vancomycin, 97.5% did not receive their treatment in the recommended time frame, compared with 1.7% of those given cefazolin.

“Increased odds of SSI among patients reporting a penicillin allergy in this cohort was entirely due to the use of beta-lactam–alternative perioperative antibiotics,” wrote to Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues. “Patients with reported penicillin allergy in this study were not only less likely to receive the most effective perioperative antibiotic, they were also less likely to receive prophylaxis in the recommended time frame for optimal tissue concentration.”

While allergy assessments before surgery are currently recommended, there are no specifically outlined methods for these evaluations, which leads many providers to take what has been deemed the safer route of giving patients beta-lactam–alternative antibiotics instead, Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues suggested.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the investigators reported having no relevant conflicts.

SOURCE: Blumenthal K et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Jan 18;66(3):329-36.

Patients with reported penicillin allergies are significantly more likely to develop surgical site infections, according to a study conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

With new evidence reporting 90%-99% of patients with a reported allergy are not actually allergic, conducting a preoperative allergy test could improve treatment choice and decrease the risk of SSI, as well as the notable financial burden associated with it. Thus, “systematic, preoperative penicillin allergy evaluations in surgical patients may not only improve antibiotic choice but also decrease SSI risk,” according to Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, the quality director for the department of allergy and immunology at Massachusetts General Hospital, and her fellow investigators.

Surgeries performed were hip arthroplasty, knee arthroplasty, hysterectomy, colon surgery, or coronary artery bypass grafting.

Of the patients studied, 922 (11%) reported a penicillin allergy; most had minor reactions, such as rashes (37.5%) or urticaria (18%). “Only 5 reactions to penicillin represented contraindications to receiving a beta-lactam; the vast majority of patients would have tolerated first-line recommended cephalosporin prophylaxis had allergy evaluation been pursued,“ according to Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues.

Overall, a total of 241 (2.7%) patients contracted an SSI. In a multivariate analysis, patients who had reported a penicillin allergy were 50% more likely to develop an SSI than those who had no reported allergy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.5; P = .04).

Risk may even be higher than 50% in the general health care population because this health center has a relatively low rate of SSIs, compared with many other hospitals, Dr. Blumenthal and her fellow investigators stated.

The increased risk primarily concerns the treatment used because those with a reported allergy were more likely than those without the allergy to be given clindamycin (48.8% vs. 3.1%, respectively), vancomycin (34.7% vs. 3.3%), gentamicin (24% vs. 2.8%), or fluoroquinolones (6.8% vs. 1.3%) instead of the most commonly used antibiotic, cefazolin (12.2% vs. 92.4%).

Patients given antibiotics other than cefazolin were usually given treatment outside of the perioperative window, which could severely increase the likelihood for developing an SSI, according to investigators. Of patients given vancomycin, 97.5% did not receive their treatment in the recommended time frame, compared with 1.7% of those given cefazolin.

“Increased odds of SSI among patients reporting a penicillin allergy in this cohort was entirely due to the use of beta-lactam–alternative perioperative antibiotics,” wrote to Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues. “Patients with reported penicillin allergy in this study were not only less likely to receive the most effective perioperative antibiotic, they were also less likely to receive prophylaxis in the recommended time frame for optimal tissue concentration.”

While allergy assessments before surgery are currently recommended, there are no specifically outlined methods for these evaluations, which leads many providers to take what has been deemed the safer route of giving patients beta-lactam–alternative antibiotics instead, Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues suggested.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the investigators reported having no relevant conflicts.

SOURCE: Blumenthal K et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Jan 18;66(3):329-36.

Patients with reported penicillin allergies are significantly more likely to develop surgical site infections, according to a study conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

With new evidence reporting 90%-99% of patients with a reported allergy are not actually allergic, conducting a preoperative allergy test could improve treatment choice and decrease the risk of SSI, as well as the notable financial burden associated with it. Thus, “systematic, preoperative penicillin allergy evaluations in surgical patients may not only improve antibiotic choice but also decrease SSI risk,” according to Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, the quality director for the department of allergy and immunology at Massachusetts General Hospital, and her fellow investigators.

Surgeries performed were hip arthroplasty, knee arthroplasty, hysterectomy, colon surgery, or coronary artery bypass grafting.

Of the patients studied, 922 (11%) reported a penicillin allergy; most had minor reactions, such as rashes (37.5%) or urticaria (18%). “Only 5 reactions to penicillin represented contraindications to receiving a beta-lactam; the vast majority of patients would have tolerated first-line recommended cephalosporin prophylaxis had allergy evaluation been pursued,“ according to Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues.

Overall, a total of 241 (2.7%) patients contracted an SSI. In a multivariate analysis, patients who had reported a penicillin allergy were 50% more likely to develop an SSI than those who had no reported allergy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.5; P = .04).

Risk may even be higher than 50% in the general health care population because this health center has a relatively low rate of SSIs, compared with many other hospitals, Dr. Blumenthal and her fellow investigators stated.

The increased risk primarily concerns the treatment used because those with a reported allergy were more likely than those without the allergy to be given clindamycin (48.8% vs. 3.1%, respectively), vancomycin (34.7% vs. 3.3%), gentamicin (24% vs. 2.8%), or fluoroquinolones (6.8% vs. 1.3%) instead of the most commonly used antibiotic, cefazolin (12.2% vs. 92.4%).

Patients given antibiotics other than cefazolin were usually given treatment outside of the perioperative window, which could severely increase the likelihood for developing an SSI, according to investigators. Of patients given vancomycin, 97.5% did not receive their treatment in the recommended time frame, compared with 1.7% of those given cefazolin.

“Increased odds of SSI among patients reporting a penicillin allergy in this cohort was entirely due to the use of beta-lactam–alternative perioperative antibiotics,” wrote to Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues. “Patients with reported penicillin allergy in this study were not only less likely to receive the most effective perioperative antibiotic, they were also less likely to receive prophylaxis in the recommended time frame for optimal tissue concentration.”

While allergy assessments before surgery are currently recommended, there are no specifically outlined methods for these evaluations, which leads many providers to take what has been deemed the safer route of giving patients beta-lactam–alternative antibiotics instead, Dr. Blumenthal and her colleagues suggested.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the investigators reported having no relevant conflicts.

SOURCE: Blumenthal K et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Jan 18;66(3):329-36.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Patients with reported penicillin allergies are at higher risk of developing a surgical site infection.

Major finding: Having a penicillin allergy was associated with a 50% increased risk of developing a surgical site infection, compared with those without the allergy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.5; P = .04).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 8,385 patients operated on at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, during 2010-2014.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the investigators reported having no relevant conflicts.

Source: Blumenthal K et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Jan 18;66(3):329-36.

Defining incisional hernia risk in IBD surgery

Open surgery for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been known to carry a high risk of incisional hernia, but the risk factors have not been well understood.

A review of 1,000 operations performed over nearly 40 years at a high-volume, nationally recognized center has identified five patient factors that can raise the risk of incisional hernia in these operations by 50% or more, according to a study published in the Annals of Surgery.

The study followed the patients for an average of 8 years after their operations, which were performed between January 1976 and December 2014 at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. The overall incidence of incisional hernia was 20%-21% for patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% for those with Crohn’s disease.

Half of these patients developed an incisional hernia less than 2 years after the index surgery and 75% in less than 4 years.

The researchers identified the following statistically significant risk factors for incisional hernia: wound infection (hazard ratio, 3.66; P less than .001); hypoalbuminemia (HR, 2.02; P = .002); previous bowel resection (HR, 1.6; P = .003); ileostomy created at time of procedure (HR, 1.53; P = .01); and a history of smoking (HR, 1.52; P less than .013). Other risk factors to lesser degrees are body mass index at time of surgery (HR, 1.036; P = .009); age at time of surgery (HR, 1.021; P less than .001), and age at disease onset (HR, 1.018; P less than .001).

Lead author Tomas Heimann, MD, and his coauthors pointed out that this study population had severe levels of disease. Almost half of the patients had severe intractable disease that had resisted medical treatment. More than a quarter of these patients had received preoperative steroid therapy within 6 weeks, and 15% had received recent immunosuppressive therapy. Almost 80% were either anemic or had hypoalbuminemia or both. The average duration of disease was 12 years. More than half had undergone previous bowel surgery – “often lengthy and difficult” – with many patients suffering from fistulae, abscesses, and dense adhesions. “These factors were more likely to predispose patients to develop wound infections and delayed healing resulting in incisional hernia in one-fifth of our patients,” Dr. Heimann and his coauthors noted.

A somewhat unexpected finding was that immunosuppressive therapy and steroids were not linked to incisional hernia in these patients.

Prophylactic mesh placement in patients with IBD is impractical because of the risk of infection it carries, Dr. Heimann and his coauthors said.

Dr. Heimann and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Heimann T et al. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar;267(3):532-6.

Open surgery for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been known to carry a high risk of incisional hernia, but the risk factors have not been well understood.

A review of 1,000 operations performed over nearly 40 years at a high-volume, nationally recognized center has identified five patient factors that can raise the risk of incisional hernia in these operations by 50% or more, according to a study published in the Annals of Surgery.

The study followed the patients for an average of 8 years after their operations, which were performed between January 1976 and December 2014 at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. The overall incidence of incisional hernia was 20%-21% for patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% for those with Crohn’s disease.

Half of these patients developed an incisional hernia less than 2 years after the index surgery and 75% in less than 4 years.

The researchers identified the following statistically significant risk factors for incisional hernia: wound infection (hazard ratio, 3.66; P less than .001); hypoalbuminemia (HR, 2.02; P = .002); previous bowel resection (HR, 1.6; P = .003); ileostomy created at time of procedure (HR, 1.53; P = .01); and a history of smoking (HR, 1.52; P less than .013). Other risk factors to lesser degrees are body mass index at time of surgery (HR, 1.036; P = .009); age at time of surgery (HR, 1.021; P less than .001), and age at disease onset (HR, 1.018; P less than .001).

Lead author Tomas Heimann, MD, and his coauthors pointed out that this study population had severe levels of disease. Almost half of the patients had severe intractable disease that had resisted medical treatment. More than a quarter of these patients had received preoperative steroid therapy within 6 weeks, and 15% had received recent immunosuppressive therapy. Almost 80% were either anemic or had hypoalbuminemia or both. The average duration of disease was 12 years. More than half had undergone previous bowel surgery – “often lengthy and difficult” – with many patients suffering from fistulae, abscesses, and dense adhesions. “These factors were more likely to predispose patients to develop wound infections and delayed healing resulting in incisional hernia in one-fifth of our patients,” Dr. Heimann and his coauthors noted.

A somewhat unexpected finding was that immunosuppressive therapy and steroids were not linked to incisional hernia in these patients.

Prophylactic mesh placement in patients with IBD is impractical because of the risk of infection it carries, Dr. Heimann and his coauthors said.

Dr. Heimann and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Heimann T et al. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar;267(3):532-6.

Open surgery for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been known to carry a high risk of incisional hernia, but the risk factors have not been well understood.

A review of 1,000 operations performed over nearly 40 years at a high-volume, nationally recognized center has identified five patient factors that can raise the risk of incisional hernia in these operations by 50% or more, according to a study published in the Annals of Surgery.

The study followed the patients for an average of 8 years after their operations, which were performed between January 1976 and December 2014 at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. The overall incidence of incisional hernia was 20%-21% for patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% for those with Crohn’s disease.

Half of these patients developed an incisional hernia less than 2 years after the index surgery and 75% in less than 4 years.

The researchers identified the following statistically significant risk factors for incisional hernia: wound infection (hazard ratio, 3.66; P less than .001); hypoalbuminemia (HR, 2.02; P = .002); previous bowel resection (HR, 1.6; P = .003); ileostomy created at time of procedure (HR, 1.53; P = .01); and a history of smoking (HR, 1.52; P less than .013). Other risk factors to lesser degrees are body mass index at time of surgery (HR, 1.036; P = .009); age at time of surgery (HR, 1.021; P less than .001), and age at disease onset (HR, 1.018; P less than .001).

Lead author Tomas Heimann, MD, and his coauthors pointed out that this study population had severe levels of disease. Almost half of the patients had severe intractable disease that had resisted medical treatment. More than a quarter of these patients had received preoperative steroid therapy within 6 weeks, and 15% had received recent immunosuppressive therapy. Almost 80% were either anemic or had hypoalbuminemia or both. The average duration of disease was 12 years. More than half had undergone previous bowel surgery – “often lengthy and difficult” – with many patients suffering from fistulae, abscesses, and dense adhesions. “These factors were more likely to predispose patients to develop wound infections and delayed healing resulting in incisional hernia in one-fifth of our patients,” Dr. Heimann and his coauthors noted.

A somewhat unexpected finding was that immunosuppressive therapy and steroids were not linked to incisional hernia in these patients.

Prophylactic mesh placement in patients with IBD is impractical because of the risk of infection it carries, Dr. Heimann and his coauthors said.

Dr. Heimann and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Heimann T et al. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar;267(3):532-6.

FROM ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Patients with IBD have a high incidence of incisional hernia after open bowel resection.

Major finding: The overall incidence of incisional hernia after open bowel resection was 20%.

Data source: One thousand patients who had undergone open bowel surgery for IBD at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, between January 1976 and December 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Heimann and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Heimann T et al. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar;267(3):532-6.

Postcesarean SSI rate declines with care bundle*

DALLAS – A surgical site infection care bundle reduced the rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) after cesarean delivery by more than half, according to a case-control study examining data from more than 2,000 patients.

At the health center where the SSI bundle was implemented, rates per 1,000 women undergoing cesarean delivery fell from 2.44 to 1.10 (P = .013).

The study showed the effectiveness of implementing evidence-based and -supported recommendations, and of having standardized protocols with little variation, said Christina Davidson, MD, presenting the pre-post findings during a plenary session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The bundle of interventions was developed over the course of 3 months in late 2013 and early 2014 by a multidisciplinary task force, drawing from colorectal surgery literature about SSI prevention. Both nurses and physicians were on the task force, and representatives came from the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, anesthesia, and infection prevention, said Dr. Davidson of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. All inpatient and outpatient clinical care sites had representation.

After the bundle elements were identified, a full month was devoted to education and team training, with full bundle implementation occurring in April 2014. “Visual aids were placed in close proximity to the operating rooms,” said Dr. Davidson. For example, antimicrobial prophylaxis cards were placed on all anesthetic carts.

“A surgical checklist was placed in the chart for each patient undergoing cesarean delivery and compliance was tracked for the first 12 months of implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. Additionally, members of the care team received feedback in the form of quarterly reports on SSI rates and statistics about bundle compliance.

Care bundle elements included a set of instructions for pre- and postoperative antiseptic skin cleaning, wound care, and glycemic control in patients. Women were given chlorhexidine cleanser and asked to use it when showering the day before and the morning of surgery for planned deliveries. Forced warm-air blankets maintained patient normothermia in the preoperative holding area.

A group of intraoperative interventions included use of antiseptic skin and vaginal preparations, double-gloving, and having all scrubbed members of the surgical team change their outer gloves for fascial closure. A new instrument tray also was used for fascial closure. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and doses were readministered based on the length of the procedure.

Postoperatively, said Dr. Davidson, “a set of insulin orders within the electronic medical record [was] used to maintain euglycemia in all diabetic patients.”

After the surgical dressing was removed on the 2nd postoperative day, patients were given a handout and education about wound control and infection prevention.

Finally, all patients received postdischarge follow-up calls from nurses within 72 hours after discharge.

Patient characteristics generally were similar before (n = 1,085) and after (n = 1,261) SSI bundle implementation. Body mass index was slightly higher in the postbundle group, and women in this group also were less likely to have had a prior cesarean delivery. There were no significant differences in age, gravidity, ethnicity, or race.

The study showed that with continued tracking, data-sharing, and reeducation efforts, “The SSI rate was sustained after bundle implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. The implementation team, working with hospital departments, was able to achieve a high compliance rate. And, she said, the effect size of the intervention was large enough to show significant reduction from an already low SSI rate.

However, Dr. Davidson also noted some limitations: All of the bundle elements were implemented simultaneously, so it wasn’t possible to tell which components had the greatest effect. Also, not all demographic data were available, and the type of SSI was sometimes unavailable from the deidentified data repository used for analysis, she said. “We weren’t able to tease out individual patient-level characteristics” about the timing and type of SSI in a patient-by-patient fashion, she said during discussion following her presentation.

All in all, she said, the bundle’s effectiveness “supports the synergistic effects of multiple strategies and the impact of a multidisciplinary team approach.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Davidson C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S46.

Correction, 3/5/18: An earlier version of this article omitted the word "rate" from the headline and Vitals section.

DALLAS – A surgical site infection care bundle reduced the rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) after cesarean delivery by more than half, according to a case-control study examining data from more than 2,000 patients.

At the health center where the SSI bundle was implemented, rates per 1,000 women undergoing cesarean delivery fell from 2.44 to 1.10 (P = .013).

The study showed the effectiveness of implementing evidence-based and -supported recommendations, and of having standardized protocols with little variation, said Christina Davidson, MD, presenting the pre-post findings during a plenary session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The bundle of interventions was developed over the course of 3 months in late 2013 and early 2014 by a multidisciplinary task force, drawing from colorectal surgery literature about SSI prevention. Both nurses and physicians were on the task force, and representatives came from the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, anesthesia, and infection prevention, said Dr. Davidson of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. All inpatient and outpatient clinical care sites had representation.

After the bundle elements were identified, a full month was devoted to education and team training, with full bundle implementation occurring in April 2014. “Visual aids were placed in close proximity to the operating rooms,” said Dr. Davidson. For example, antimicrobial prophylaxis cards were placed on all anesthetic carts.

“A surgical checklist was placed in the chart for each patient undergoing cesarean delivery and compliance was tracked for the first 12 months of implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. Additionally, members of the care team received feedback in the form of quarterly reports on SSI rates and statistics about bundle compliance.

Care bundle elements included a set of instructions for pre- and postoperative antiseptic skin cleaning, wound care, and glycemic control in patients. Women were given chlorhexidine cleanser and asked to use it when showering the day before and the morning of surgery for planned deliveries. Forced warm-air blankets maintained patient normothermia in the preoperative holding area.

A group of intraoperative interventions included use of antiseptic skin and vaginal preparations, double-gloving, and having all scrubbed members of the surgical team change their outer gloves for fascial closure. A new instrument tray also was used for fascial closure. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and doses were readministered based on the length of the procedure.