User login

Transfusion-related lung injury is on the rise in elderly patients

SAN ANTONIO – Although there has been a general decline in transfusion-related anaphylaxis and acute infections over time among hospitalized older adults in the United States, incidence rates for both transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload have risen over the last decade, according to researchers from the Food and Drug Administration.

Mikhail Menis, PharmD, an epidemiologist at the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and colleagues queried large Medicare databases to assess trends in transfusion-related adverse events among adults aged 65 years and older.

The investigators saw “substantially higher risk of all outcomes among immunocompromised beneficiaries, which could be related to higher blood use of all blood components, especially platelets, underlying conditions such as malignancies, and treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation, which need further investigation,” Dr. Menis said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

He reported data from a series of studies on four categories of transfusion-related events that may be life-threatening or fatal: transfusion-related anaphylaxis (TRA), transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), and acute infection following transfusion (AIFT).

For each type of event, the researchers looked at overall incidence and the incidence by immune status, calendar year, blood components transfused, number of units transfused, age, sex, and race.

Anaphylaxis (TRA)

TRA may be caused by preformed immunoglobin E (IgE) antibodies to proteins in the plasma in transfused blood products or by preformed IgA antibodies in patients who are likely IgA deficient, Dr. Menis said.

The overall incidence of TRA among 8,833,817 inpatient transfusions stays for elderly beneficiaries from 2012 through 2018 was 7.1 per 100,000 stays. The rate was higher for immunocompromised patients, at 9.6, than it was among nonimmunocompromised patients, at 6.5.

The rates varied by every subgroup measured except immune status. Annual rates showed a downward trend, from 8.7 per 100,000 in 2012, to 5.1 in 2017 and 6.4 in 2018. The decline in occurrence may be caused by a decline in inpatient blood utilization during the study period, particularly among immunocompromised patients.

TRA rates increased with five or more units transfused. The risk was significantly reduced in the oldest group of patients versus the youngest (P less than .001), which supports the immune-based mechanism of action of anaphylaxis, Dr. Menis said.

They also found that TRA rates were substantially higher among patients who had received platelet and/or plasma transfusions, compared with patients who received only red blood cells (RBCs).

Additionally, risk for TRA was significantly higher among men than it was among women (9.3 vs. 5.4) and among white versus nonwhite patients (7.8 vs. 3.8).

The evidence suggested TRA cases are likely to be severe in this population, with inpatient mortality of 7.1%, and hospital stays of 7 days or longer in about 58% of cases, indicating the importance of TRA prevention, Dr. Menis said.

The investigators plan to perform multivariate regression analyses to assess potential risk factors, including underlying comorbidities and health histories for TRA occurrence for both the overall population and by immune status.

Acute lung injury (TRALI)

TRALI is a rare but serious adverse event, a clinical syndrome with onset within 6 hours of transfusion that presents as acute hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Among 17,771,193 total inpatient transfusion stays, the overall incidence of TRALI was 33.2 per 100,000. The rate was 55.9 for immunocompromised patients versus 28.4 for nonimmunocompromised patients. The rate ratio was 2.0 (P less than .001).

The difference by immune status may be caused by higher blood utilizations with more units transfused per stay among immunocompromised patients, a higher incidence of prior transfusions among these patients, higher use of irradiated blood components that may lead to accumulation of proinflammatory mediators in blood products during storage, or underlying comorbidities.

The overall rate increased from 14.3 in 2007 to 56.4 in 2018. The rates increased proportionally among both immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.

As with TRA, the incidence of TRALI was higher in patients with five or more units transfused, while the incidence declined with age, likely caused by declining blood use and age-related changes in neutrophil function, Dr. Menis said.

TRALI rates were slightly higher among men than among women, as well as higher among white patients than among nonwhite patients.

Overall, TRALI rates were higher for patients who received platelets either alone or in combination with RBCs and/or plasma. The highest rates were among patients who received RBCs, plasma and platelets.

Dr. Menis called for studies to determine what effects the processing and storage of blood components may have on TRALI occurrence; he and his colleagues also are planning regression analyses to assess potential risk factors for this complication.

Circulatory overload (TACO)

TACO is one of the leading reported causes of transfusion-related fatalities in the U.S., with onset usually occurring within 6 hours of transfusion, presenting as acute respiratory distress with dyspnea, orthopnea, increased blood pressure, and cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

The overall incidence of TACO among hospitalized patients aged 65 years and older from 2011 through 2018 was 86.3 per 100,000 stays. The incidences were 128.3 in immunocompromised and 76.0 in nonimmunocompromised patients. The rate ratio for TACO in immunocompromised versus nonimmunocompromised patients was 1.70 (P less than .001).

Overall incidence rates of TACO rose from 62 per 100,000 stays in 2011 to 119.8 in 2018. As with other adverse events, incident rates rose with the number of units transfused.

Rates of TACO were significantly higher among women than they were among men (94.6 vs. 75.9 per 100,000; P less than .001), which could be caused by the higher mean age of women and/or a lower tolerance for increased blood volume from transfusion.

The study results also suggested that TACO and TRALI may coexist, based on evidence that 3.5% of all TACO stays also had diagnostic codes for TRALI. The frequency of co-occurrence of these two adverse events also increased over time, which may be caused by improved awareness, Dr. Menis said.

Infections (AIFT)

Acute infections following transfusion can lead to prolonged hospitalizations, sepsis, septic shock, and death. Those most at risk include elderly and immunocompromised patients because of high utilization of blood products, comorbidities, and decreased immune function.

Among 8,833,817 stays, the overall rate per 100,000 stays was 2.1. The rate for immunocompromised patients was 5.4, compared with 1.2 for nonimmunocompromised patients, for a rate ratio of 4.4 (P less than .001).

The incidence rate declined significantly (P = .03) over the study period, with the 3 latest years having the lowest rates.

Rates increased substantially among immunocompromised patients by the number of units transfused, but remained relatively stable among nonimmunocompromised patients.

Infection rates declined with age, from 2.7 per 100,000 stays for patients aged 65-68 years to 1.2 per 100,000 for those aged 85 years and older.

As with other adverse events, AIFT rates were likely related to the blood components transfused, with substantially higher rates for stays during which platelets were transfused either alone or with RBCs, compared with RBCs alone. This could be caused by the room-temperature storage of platelets and higher number of platelets units transfused, compared with RBCs alone, especially among immunocompromised patients.

In all, 51.9% of AIFT cases also had sepsis noted in the medical record, indicating high severity and emphasizing the importance of AIFT prevention, Dr. Menis said.

The studies were funded by the FDA, and Dr. Menis is an FDA employee. He reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Although there has been a general decline in transfusion-related anaphylaxis and acute infections over time among hospitalized older adults in the United States, incidence rates for both transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload have risen over the last decade, according to researchers from the Food and Drug Administration.

Mikhail Menis, PharmD, an epidemiologist at the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and colleagues queried large Medicare databases to assess trends in transfusion-related adverse events among adults aged 65 years and older.

The investigators saw “substantially higher risk of all outcomes among immunocompromised beneficiaries, which could be related to higher blood use of all blood components, especially platelets, underlying conditions such as malignancies, and treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation, which need further investigation,” Dr. Menis said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

He reported data from a series of studies on four categories of transfusion-related events that may be life-threatening or fatal: transfusion-related anaphylaxis (TRA), transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), and acute infection following transfusion (AIFT).

For each type of event, the researchers looked at overall incidence and the incidence by immune status, calendar year, blood components transfused, number of units transfused, age, sex, and race.

Anaphylaxis (TRA)

TRA may be caused by preformed immunoglobin E (IgE) antibodies to proteins in the plasma in transfused blood products or by preformed IgA antibodies in patients who are likely IgA deficient, Dr. Menis said.

The overall incidence of TRA among 8,833,817 inpatient transfusions stays for elderly beneficiaries from 2012 through 2018 was 7.1 per 100,000 stays. The rate was higher for immunocompromised patients, at 9.6, than it was among nonimmunocompromised patients, at 6.5.

The rates varied by every subgroup measured except immune status. Annual rates showed a downward trend, from 8.7 per 100,000 in 2012, to 5.1 in 2017 and 6.4 in 2018. The decline in occurrence may be caused by a decline in inpatient blood utilization during the study period, particularly among immunocompromised patients.

TRA rates increased with five or more units transfused. The risk was significantly reduced in the oldest group of patients versus the youngest (P less than .001), which supports the immune-based mechanism of action of anaphylaxis, Dr. Menis said.

They also found that TRA rates were substantially higher among patients who had received platelet and/or plasma transfusions, compared with patients who received only red blood cells (RBCs).

Additionally, risk for TRA was significantly higher among men than it was among women (9.3 vs. 5.4) and among white versus nonwhite patients (7.8 vs. 3.8).

The evidence suggested TRA cases are likely to be severe in this population, with inpatient mortality of 7.1%, and hospital stays of 7 days or longer in about 58% of cases, indicating the importance of TRA prevention, Dr. Menis said.

The investigators plan to perform multivariate regression analyses to assess potential risk factors, including underlying comorbidities and health histories for TRA occurrence for both the overall population and by immune status.

Acute lung injury (TRALI)

TRALI is a rare but serious adverse event, a clinical syndrome with onset within 6 hours of transfusion that presents as acute hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Among 17,771,193 total inpatient transfusion stays, the overall incidence of TRALI was 33.2 per 100,000. The rate was 55.9 for immunocompromised patients versus 28.4 for nonimmunocompromised patients. The rate ratio was 2.0 (P less than .001).

The difference by immune status may be caused by higher blood utilizations with more units transfused per stay among immunocompromised patients, a higher incidence of prior transfusions among these patients, higher use of irradiated blood components that may lead to accumulation of proinflammatory mediators in blood products during storage, or underlying comorbidities.

The overall rate increased from 14.3 in 2007 to 56.4 in 2018. The rates increased proportionally among both immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.

As with TRA, the incidence of TRALI was higher in patients with five or more units transfused, while the incidence declined with age, likely caused by declining blood use and age-related changes in neutrophil function, Dr. Menis said.

TRALI rates were slightly higher among men than among women, as well as higher among white patients than among nonwhite patients.

Overall, TRALI rates were higher for patients who received platelets either alone or in combination with RBCs and/or plasma. The highest rates were among patients who received RBCs, plasma and platelets.

Dr. Menis called for studies to determine what effects the processing and storage of blood components may have on TRALI occurrence; he and his colleagues also are planning regression analyses to assess potential risk factors for this complication.

Circulatory overload (TACO)

TACO is one of the leading reported causes of transfusion-related fatalities in the U.S., with onset usually occurring within 6 hours of transfusion, presenting as acute respiratory distress with dyspnea, orthopnea, increased blood pressure, and cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

The overall incidence of TACO among hospitalized patients aged 65 years and older from 2011 through 2018 was 86.3 per 100,000 stays. The incidences were 128.3 in immunocompromised and 76.0 in nonimmunocompromised patients. The rate ratio for TACO in immunocompromised versus nonimmunocompromised patients was 1.70 (P less than .001).

Overall incidence rates of TACO rose from 62 per 100,000 stays in 2011 to 119.8 in 2018. As with other adverse events, incident rates rose with the number of units transfused.

Rates of TACO were significantly higher among women than they were among men (94.6 vs. 75.9 per 100,000; P less than .001), which could be caused by the higher mean age of women and/or a lower tolerance for increased blood volume from transfusion.

The study results also suggested that TACO and TRALI may coexist, based on evidence that 3.5% of all TACO stays also had diagnostic codes for TRALI. The frequency of co-occurrence of these two adverse events also increased over time, which may be caused by improved awareness, Dr. Menis said.

Infections (AIFT)

Acute infections following transfusion can lead to prolonged hospitalizations, sepsis, septic shock, and death. Those most at risk include elderly and immunocompromised patients because of high utilization of blood products, comorbidities, and decreased immune function.

Among 8,833,817 stays, the overall rate per 100,000 stays was 2.1. The rate for immunocompromised patients was 5.4, compared with 1.2 for nonimmunocompromised patients, for a rate ratio of 4.4 (P less than .001).

The incidence rate declined significantly (P = .03) over the study period, with the 3 latest years having the lowest rates.

Rates increased substantially among immunocompromised patients by the number of units transfused, but remained relatively stable among nonimmunocompromised patients.

Infection rates declined with age, from 2.7 per 100,000 stays for patients aged 65-68 years to 1.2 per 100,000 for those aged 85 years and older.

As with other adverse events, AIFT rates were likely related to the blood components transfused, with substantially higher rates for stays during which platelets were transfused either alone or with RBCs, compared with RBCs alone. This could be caused by the room-temperature storage of platelets and higher number of platelets units transfused, compared with RBCs alone, especially among immunocompromised patients.

In all, 51.9% of AIFT cases also had sepsis noted in the medical record, indicating high severity and emphasizing the importance of AIFT prevention, Dr. Menis said.

The studies were funded by the FDA, and Dr. Menis is an FDA employee. He reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Although there has been a general decline in transfusion-related anaphylaxis and acute infections over time among hospitalized older adults in the United States, incidence rates for both transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload have risen over the last decade, according to researchers from the Food and Drug Administration.

Mikhail Menis, PharmD, an epidemiologist at the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and colleagues queried large Medicare databases to assess trends in transfusion-related adverse events among adults aged 65 years and older.

The investigators saw “substantially higher risk of all outcomes among immunocompromised beneficiaries, which could be related to higher blood use of all blood components, especially platelets, underlying conditions such as malignancies, and treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation, which need further investigation,” Dr. Menis said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

He reported data from a series of studies on four categories of transfusion-related events that may be life-threatening or fatal: transfusion-related anaphylaxis (TRA), transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), and acute infection following transfusion (AIFT).

For each type of event, the researchers looked at overall incidence and the incidence by immune status, calendar year, blood components transfused, number of units transfused, age, sex, and race.

Anaphylaxis (TRA)

TRA may be caused by preformed immunoglobin E (IgE) antibodies to proteins in the plasma in transfused blood products or by preformed IgA antibodies in patients who are likely IgA deficient, Dr. Menis said.

The overall incidence of TRA among 8,833,817 inpatient transfusions stays for elderly beneficiaries from 2012 through 2018 was 7.1 per 100,000 stays. The rate was higher for immunocompromised patients, at 9.6, than it was among nonimmunocompromised patients, at 6.5.

The rates varied by every subgroup measured except immune status. Annual rates showed a downward trend, from 8.7 per 100,000 in 2012, to 5.1 in 2017 and 6.4 in 2018. The decline in occurrence may be caused by a decline in inpatient blood utilization during the study period, particularly among immunocompromised patients.

TRA rates increased with five or more units transfused. The risk was significantly reduced in the oldest group of patients versus the youngest (P less than .001), which supports the immune-based mechanism of action of anaphylaxis, Dr. Menis said.

They also found that TRA rates were substantially higher among patients who had received platelet and/or plasma transfusions, compared with patients who received only red blood cells (RBCs).

Additionally, risk for TRA was significantly higher among men than it was among women (9.3 vs. 5.4) and among white versus nonwhite patients (7.8 vs. 3.8).

The evidence suggested TRA cases are likely to be severe in this population, with inpatient mortality of 7.1%, and hospital stays of 7 days or longer in about 58% of cases, indicating the importance of TRA prevention, Dr. Menis said.

The investigators plan to perform multivariate regression analyses to assess potential risk factors, including underlying comorbidities and health histories for TRA occurrence for both the overall population and by immune status.

Acute lung injury (TRALI)

TRALI is a rare but serious adverse event, a clinical syndrome with onset within 6 hours of transfusion that presents as acute hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Among 17,771,193 total inpatient transfusion stays, the overall incidence of TRALI was 33.2 per 100,000. The rate was 55.9 for immunocompromised patients versus 28.4 for nonimmunocompromised patients. The rate ratio was 2.0 (P less than .001).

The difference by immune status may be caused by higher blood utilizations with more units transfused per stay among immunocompromised patients, a higher incidence of prior transfusions among these patients, higher use of irradiated blood components that may lead to accumulation of proinflammatory mediators in blood products during storage, or underlying comorbidities.

The overall rate increased from 14.3 in 2007 to 56.4 in 2018. The rates increased proportionally among both immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.

As with TRA, the incidence of TRALI was higher in patients with five or more units transfused, while the incidence declined with age, likely caused by declining blood use and age-related changes in neutrophil function, Dr. Menis said.

TRALI rates were slightly higher among men than among women, as well as higher among white patients than among nonwhite patients.

Overall, TRALI rates were higher for patients who received platelets either alone or in combination with RBCs and/or plasma. The highest rates were among patients who received RBCs, plasma and platelets.

Dr. Menis called for studies to determine what effects the processing and storage of blood components may have on TRALI occurrence; he and his colleagues also are planning regression analyses to assess potential risk factors for this complication.

Circulatory overload (TACO)

TACO is one of the leading reported causes of transfusion-related fatalities in the U.S., with onset usually occurring within 6 hours of transfusion, presenting as acute respiratory distress with dyspnea, orthopnea, increased blood pressure, and cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

The overall incidence of TACO among hospitalized patients aged 65 years and older from 2011 through 2018 was 86.3 per 100,000 stays. The incidences were 128.3 in immunocompromised and 76.0 in nonimmunocompromised patients. The rate ratio for TACO in immunocompromised versus nonimmunocompromised patients was 1.70 (P less than .001).

Overall incidence rates of TACO rose from 62 per 100,000 stays in 2011 to 119.8 in 2018. As with other adverse events, incident rates rose with the number of units transfused.

Rates of TACO were significantly higher among women than they were among men (94.6 vs. 75.9 per 100,000; P less than .001), which could be caused by the higher mean age of women and/or a lower tolerance for increased blood volume from transfusion.

The study results also suggested that TACO and TRALI may coexist, based on evidence that 3.5% of all TACO stays also had diagnostic codes for TRALI. The frequency of co-occurrence of these two adverse events also increased over time, which may be caused by improved awareness, Dr. Menis said.

Infections (AIFT)

Acute infections following transfusion can lead to prolonged hospitalizations, sepsis, septic shock, and death. Those most at risk include elderly and immunocompromised patients because of high utilization of blood products, comorbidities, and decreased immune function.

Among 8,833,817 stays, the overall rate per 100,000 stays was 2.1. The rate for immunocompromised patients was 5.4, compared with 1.2 for nonimmunocompromised patients, for a rate ratio of 4.4 (P less than .001).

The incidence rate declined significantly (P = .03) over the study period, with the 3 latest years having the lowest rates.

Rates increased substantially among immunocompromised patients by the number of units transfused, but remained relatively stable among nonimmunocompromised patients.

Infection rates declined with age, from 2.7 per 100,000 stays for patients aged 65-68 years to 1.2 per 100,000 for those aged 85 years and older.

As with other adverse events, AIFT rates were likely related to the blood components transfused, with substantially higher rates for stays during which platelets were transfused either alone or with RBCs, compared with RBCs alone. This could be caused by the room-temperature storage of platelets and higher number of platelets units transfused, compared with RBCs alone, especially among immunocompromised patients.

In all, 51.9% of AIFT cases also had sepsis noted in the medical record, indicating high severity and emphasizing the importance of AIFT prevention, Dr. Menis said.

The studies were funded by the FDA, and Dr. Menis is an FDA employee. He reported having no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AABB 2019

FDA approves anemia treatment for transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia patients

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for anemia in adults with transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia.

Luspatercept-aamt (Reblozyl) is an erythroid maturation agent that reduced the transfusion burden for patients with beta thalassemia in the BELIEVE trial of 336 patients. In total, 21% of patients who received luspatercept-aamt achieved at least a 33% reduction in red blood cell transfusions, compared with 4.5% of patients who received placebo, according to the FDA.

Common side effects associated with luspatercept-aamt were headache, bone pain, arthralgia, fatigue, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dizziness. Patients taking the agent should be monitored for thrombosis, the FDA advised.

Celgene, which makes luspatercept-aamt, said the agent would be available about 1 week following the FDA approval.

The FDA is also evaluating luspatercept-aamt as an anemia treatment in adults with very-low– to intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have ring sideroblasts and require red blood cell transfusions. The agency is expected to take action on that application in April 2020.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for anemia in adults with transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia.

Luspatercept-aamt (Reblozyl) is an erythroid maturation agent that reduced the transfusion burden for patients with beta thalassemia in the BELIEVE trial of 336 patients. In total, 21% of patients who received luspatercept-aamt achieved at least a 33% reduction in red blood cell transfusions, compared with 4.5% of patients who received placebo, according to the FDA.

Common side effects associated with luspatercept-aamt were headache, bone pain, arthralgia, fatigue, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dizziness. Patients taking the agent should be monitored for thrombosis, the FDA advised.

Celgene, which makes luspatercept-aamt, said the agent would be available about 1 week following the FDA approval.

The FDA is also evaluating luspatercept-aamt as an anemia treatment in adults with very-low– to intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have ring sideroblasts and require red blood cell transfusions. The agency is expected to take action on that application in April 2020.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for anemia in adults with transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia.

Luspatercept-aamt (Reblozyl) is an erythroid maturation agent that reduced the transfusion burden for patients with beta thalassemia in the BELIEVE trial of 336 patients. In total, 21% of patients who received luspatercept-aamt achieved at least a 33% reduction in red blood cell transfusions, compared with 4.5% of patients who received placebo, according to the FDA.

Common side effects associated with luspatercept-aamt were headache, bone pain, arthralgia, fatigue, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dizziness. Patients taking the agent should be monitored for thrombosis, the FDA advised.

Celgene, which makes luspatercept-aamt, said the agent would be available about 1 week following the FDA approval.

The FDA is also evaluating luspatercept-aamt as an anemia treatment in adults with very-low– to intermediate-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have ring sideroblasts and require red blood cell transfusions. The agency is expected to take action on that application in April 2020.

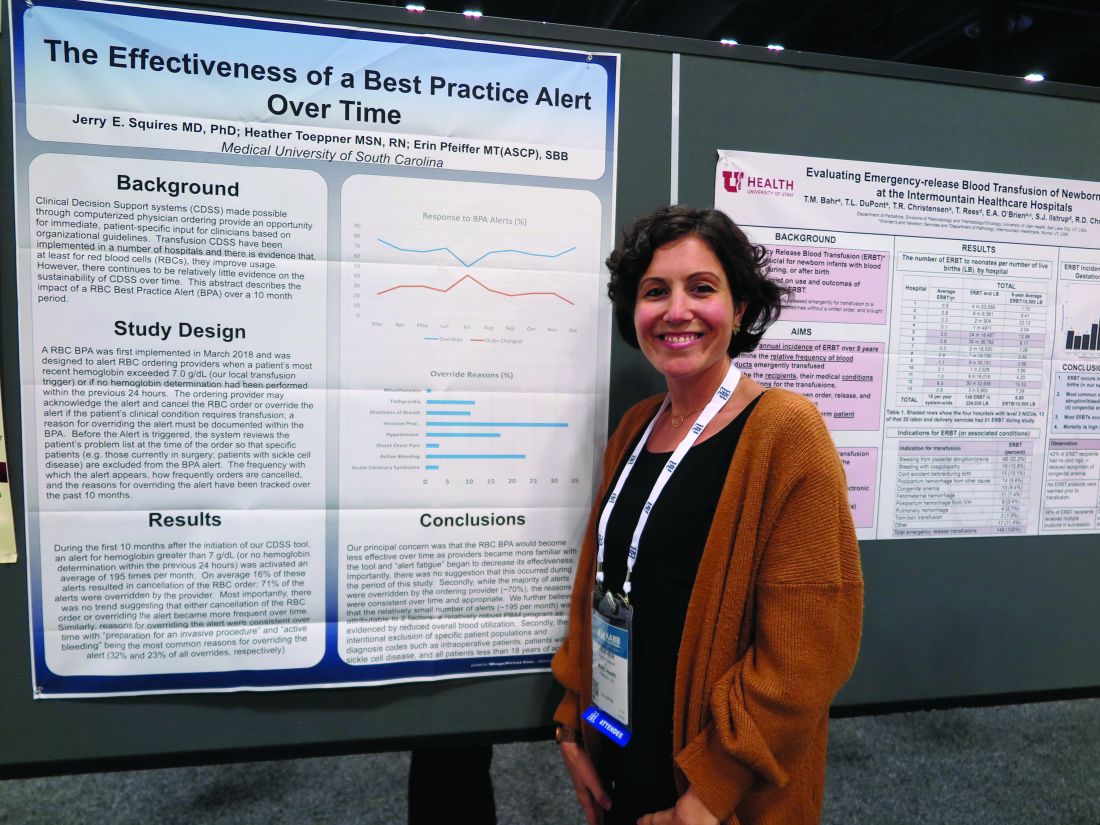

Best practice alerts really can work

SAN ANTONIO – Clinicians don’t appear to mind too much when their red blood cell orders are flagged for review by a best practice alert system, and alert fatigue doesn’t seem to hamper patient blood management efforts, investigators in a single-center study reported.

At the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston (MUSC), if clinicians order RBC transfusions for patients with hemoglobin levels over 7.0 g/dL or for patients who did not have a hemoglobin determination over the past 24 hours, they receive a best practice alert. They must acknowledge it and cancel the order, or override it and document a reason in the medical record.

Although approximately 70% of alerts were overridden, the reasons for the overrides “were consistent over time and appropriate,” reported Jerry E. Squires, MD, PhD, and colleagues from MUSC in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The goal of the study was to find out if the effectiveness of the alert was wearing out after months of active use by clinicians. “Is it true that they’re clicking too much and they’re inundated with other [best practice alerts], and are they even paying attention?” said coauthor Heather Toeppner, RN, also from MUSC, in an interview. “All in all, we found that the alert is making a lasting impression in our institution,” she said.

Transfusion clinical decision support systems that produce automated alerts for clinicians can improve usage and reduce waste of RBCs, but whether the effect is sustained over time was unknown, Ms. Toeppner said, prompting the investigators to study the effect of the RBC best practice alert over 10 months.

As noted, the alert is triggered when providers order RBCs for patients with hemoglobin levels over 7.0 g/dL or when there is no record of a hemoglobin test in the chart within the past 24 hours. Before the alert is triggered, however, the system reviews the record and excludes alerts for patients with specific conditions, such as concurrent surgery or sickle cell disease.

The authors found that the alert was triggered an average of 195 times per month over the 10 months studied. On average, 16% of the alerts resulted in a cancellation of the RBC order, and 71% of alerts were overridden.

“Most importantly, there was no trend suggesting that either cancellation of the RBC order or overriding the alert became more frequent over time,” the investigators wrote. “Similarly, reasons for overriding the alert were consistent over time, with ‘preparation for an invasive procedure’ and ‘active bleeding’ being the most common reasons for overriding the alert (32% and 23% of all overrides, respectively).”

Other common reasons for overrides included tachycardia, shortness of breath, hypotension, onset of chest pain, and acute coronary syndrome.

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, they found that overrides dropped sharply and changed orders rose by the same magnitude in July, when new residents started their rotations.

The investigators wrote that the relatively small number of alerts may be attributable to their institution’s robust patient blood management program and the intentional exclusion of orders for patients with specific diagnostic codes, including intraoperative patients, those with sickle cell disease, and all patients aged younger than 18 years.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Clinicians don’t appear to mind too much when their red blood cell orders are flagged for review by a best practice alert system, and alert fatigue doesn’t seem to hamper patient blood management efforts, investigators in a single-center study reported.

At the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston (MUSC), if clinicians order RBC transfusions for patients with hemoglobin levels over 7.0 g/dL or for patients who did not have a hemoglobin determination over the past 24 hours, they receive a best practice alert. They must acknowledge it and cancel the order, or override it and document a reason in the medical record.

Although approximately 70% of alerts were overridden, the reasons for the overrides “were consistent over time and appropriate,” reported Jerry E. Squires, MD, PhD, and colleagues from MUSC in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The goal of the study was to find out if the effectiveness of the alert was wearing out after months of active use by clinicians. “Is it true that they’re clicking too much and they’re inundated with other [best practice alerts], and are they even paying attention?” said coauthor Heather Toeppner, RN, also from MUSC, in an interview. “All in all, we found that the alert is making a lasting impression in our institution,” she said.

Transfusion clinical decision support systems that produce automated alerts for clinicians can improve usage and reduce waste of RBCs, but whether the effect is sustained over time was unknown, Ms. Toeppner said, prompting the investigators to study the effect of the RBC best practice alert over 10 months.

As noted, the alert is triggered when providers order RBCs for patients with hemoglobin levels over 7.0 g/dL or when there is no record of a hemoglobin test in the chart within the past 24 hours. Before the alert is triggered, however, the system reviews the record and excludes alerts for patients with specific conditions, such as concurrent surgery or sickle cell disease.

The authors found that the alert was triggered an average of 195 times per month over the 10 months studied. On average, 16% of the alerts resulted in a cancellation of the RBC order, and 71% of alerts were overridden.

“Most importantly, there was no trend suggesting that either cancellation of the RBC order or overriding the alert became more frequent over time,” the investigators wrote. “Similarly, reasons for overriding the alert were consistent over time, with ‘preparation for an invasive procedure’ and ‘active bleeding’ being the most common reasons for overriding the alert (32% and 23% of all overrides, respectively).”

Other common reasons for overrides included tachycardia, shortness of breath, hypotension, onset of chest pain, and acute coronary syndrome.

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, they found that overrides dropped sharply and changed orders rose by the same magnitude in July, when new residents started their rotations.

The investigators wrote that the relatively small number of alerts may be attributable to their institution’s robust patient blood management program and the intentional exclusion of orders for patients with specific diagnostic codes, including intraoperative patients, those with sickle cell disease, and all patients aged younger than 18 years.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Clinicians don’t appear to mind too much when their red blood cell orders are flagged for review by a best practice alert system, and alert fatigue doesn’t seem to hamper patient blood management efforts, investigators in a single-center study reported.

At the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston (MUSC), if clinicians order RBC transfusions for patients with hemoglobin levels over 7.0 g/dL or for patients who did not have a hemoglobin determination over the past 24 hours, they receive a best practice alert. They must acknowledge it and cancel the order, or override it and document a reason in the medical record.

Although approximately 70% of alerts were overridden, the reasons for the overrides “were consistent over time and appropriate,” reported Jerry E. Squires, MD, PhD, and colleagues from MUSC in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The goal of the study was to find out if the effectiveness of the alert was wearing out after months of active use by clinicians. “Is it true that they’re clicking too much and they’re inundated with other [best practice alerts], and are they even paying attention?” said coauthor Heather Toeppner, RN, also from MUSC, in an interview. “All in all, we found that the alert is making a lasting impression in our institution,” she said.

Transfusion clinical decision support systems that produce automated alerts for clinicians can improve usage and reduce waste of RBCs, but whether the effect is sustained over time was unknown, Ms. Toeppner said, prompting the investigators to study the effect of the RBC best practice alert over 10 months.

As noted, the alert is triggered when providers order RBCs for patients with hemoglobin levels over 7.0 g/dL or when there is no record of a hemoglobin test in the chart within the past 24 hours. Before the alert is triggered, however, the system reviews the record and excludes alerts for patients with specific conditions, such as concurrent surgery or sickle cell disease.

The authors found that the alert was triggered an average of 195 times per month over the 10 months studied. On average, 16% of the alerts resulted in a cancellation of the RBC order, and 71% of alerts were overridden.

“Most importantly, there was no trend suggesting that either cancellation of the RBC order or overriding the alert became more frequent over time,” the investigators wrote. “Similarly, reasons for overriding the alert were consistent over time, with ‘preparation for an invasive procedure’ and ‘active bleeding’ being the most common reasons for overriding the alert (32% and 23% of all overrides, respectively).”

Other common reasons for overrides included tachycardia, shortness of breath, hypotension, onset of chest pain, and acute coronary syndrome.

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, they found that overrides dropped sharply and changed orders rose by the same magnitude in July, when new residents started their rotations.

The investigators wrote that the relatively small number of alerts may be attributable to their institution’s robust patient blood management program and the intentional exclusion of orders for patients with specific diagnostic codes, including intraoperative patients, those with sickle cell disease, and all patients aged younger than 18 years.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AABB 2019

Fresh RBCs offer no benefit over older cells in pediatric ICU

SAN ANTONIO – Fresh red cells were no better than conventional stored red cells when transfused into critically ill children, and there was some evidence in the ABC PICU trial suggesting that fresh red cells could be associated with a higher incidence of posttransfusion organ dysfunction.

Among 1,461 children randomly assigned to receive RBC transfusions with either fresh cells (stored for 7 days or less) or standard-issue cells (stored anywhere from 2-42 days), there were no differences in the primary endpoint of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), reported Philip Spinella, MD from Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results do not support current blood management policies that recommend providing fresh red cell units to certain populations of children,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The study findings support those of a systematic review (Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:77-88), whose authors found that “transfusion of fresher RBCs is not associated with decreased risk of death but is associated with higher rates of transfusion reactions and possibly infection.” The authors of the review concluded that “the current evidence does not support a change from current usual transfusion practice.”

Is fresh really better?

The launch of the ABC PICU trial was motivated by laboratory and observational evidence suggesting that older RBCs may be less safe or efficacious than fresh RBCs, especially in vulnerable populations such as critically ill children.

Although physician and institutional practice has been to transfuse fresh RBCs to some pediatric patients, the standard practice among blood banks has been to deliver the oldest stored units first, in an effort to prevent product wastage.

Dr. Spinella and colleagues across 50 centers in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, and Israel enrolled patients who were admitted to a pediatric ICU who received their first RBC transfusion within 7 days of admission and had an expected length of stay after transfusion of more than 24 hours.

The median patient age was 1.8 years for those who received fresh cells, and 1.9 years for those who received usual care.

There were 1,630 transfusions of fresh RBCs stored for a median of 5 days and 1,533 transfusions of standard RBCs stored for a median of 18 days. The median volume of red cell units transfused was 17.5 mL/kg in the fresh group and 16.6 mL/kg in the standard group.

The incidence of NPMODS was 20.2% for fresh-RBC recipients and 18.2% for standard-product recipients. The absolute difference of 2.0% was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences in the timing of NPMODS occurrence between the groups, and no significant differences by patient age (28 days or younger, 29-365 days old, or older than 1 year).

Similarly, there were no differences in NPMODS incidence between the groups by country, although in Canada there was a trend toward a higher incidence of organ dysfunction in the group that received fresh RBCs, Dr. Spinella noted.

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups by admission to the ICU by medical, surgical, cardiac, or trauma services; no differences by quartile of red cell volume transfused; and no differences in mortality rates either in the ICU or the main hospital, or at 28 or 90 days after discharge.

Why no difference?

Seeking explanations for why fresh RBCs did not perform better than older stored cells, Dr. Spinella suggested that changes such as storage lesions that occur over time may not be as clinically relevant as previously supposed.

“Another possibility is that these study patients didn’t need red cells to begin with to improve oxygen delivery,” he said.

Other potential explanations include the possibility that exposure to fresh red cells may be associated with immune suppression because viable white cells may also be present in the product, and that the chronological age of a stored red cell unit may not equate to its biologic or metabolic age or performance, he added.

ABC PICU was supported by Washington University; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian and French governments; and other groups. Dr. Spinella reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Fresh red cells were no better than conventional stored red cells when transfused into critically ill children, and there was some evidence in the ABC PICU trial suggesting that fresh red cells could be associated with a higher incidence of posttransfusion organ dysfunction.

Among 1,461 children randomly assigned to receive RBC transfusions with either fresh cells (stored for 7 days or less) or standard-issue cells (stored anywhere from 2-42 days), there were no differences in the primary endpoint of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), reported Philip Spinella, MD from Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results do not support current blood management policies that recommend providing fresh red cell units to certain populations of children,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The study findings support those of a systematic review (Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:77-88), whose authors found that “transfusion of fresher RBCs is not associated with decreased risk of death but is associated with higher rates of transfusion reactions and possibly infection.” The authors of the review concluded that “the current evidence does not support a change from current usual transfusion practice.”

Is fresh really better?

The launch of the ABC PICU trial was motivated by laboratory and observational evidence suggesting that older RBCs may be less safe or efficacious than fresh RBCs, especially in vulnerable populations such as critically ill children.

Although physician and institutional practice has been to transfuse fresh RBCs to some pediatric patients, the standard practice among blood banks has been to deliver the oldest stored units first, in an effort to prevent product wastage.

Dr. Spinella and colleagues across 50 centers in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, and Israel enrolled patients who were admitted to a pediatric ICU who received their first RBC transfusion within 7 days of admission and had an expected length of stay after transfusion of more than 24 hours.

The median patient age was 1.8 years for those who received fresh cells, and 1.9 years for those who received usual care.

There were 1,630 transfusions of fresh RBCs stored for a median of 5 days and 1,533 transfusions of standard RBCs stored for a median of 18 days. The median volume of red cell units transfused was 17.5 mL/kg in the fresh group and 16.6 mL/kg in the standard group.

The incidence of NPMODS was 20.2% for fresh-RBC recipients and 18.2% for standard-product recipients. The absolute difference of 2.0% was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences in the timing of NPMODS occurrence between the groups, and no significant differences by patient age (28 days or younger, 29-365 days old, or older than 1 year).

Similarly, there were no differences in NPMODS incidence between the groups by country, although in Canada there was a trend toward a higher incidence of organ dysfunction in the group that received fresh RBCs, Dr. Spinella noted.

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups by admission to the ICU by medical, surgical, cardiac, or trauma services; no differences by quartile of red cell volume transfused; and no differences in mortality rates either in the ICU or the main hospital, or at 28 or 90 days after discharge.

Why no difference?

Seeking explanations for why fresh RBCs did not perform better than older stored cells, Dr. Spinella suggested that changes such as storage lesions that occur over time may not be as clinically relevant as previously supposed.

“Another possibility is that these study patients didn’t need red cells to begin with to improve oxygen delivery,” he said.

Other potential explanations include the possibility that exposure to fresh red cells may be associated with immune suppression because viable white cells may also be present in the product, and that the chronological age of a stored red cell unit may not equate to its biologic or metabolic age or performance, he added.

ABC PICU was supported by Washington University; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian and French governments; and other groups. Dr. Spinella reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Fresh red cells were no better than conventional stored red cells when transfused into critically ill children, and there was some evidence in the ABC PICU trial suggesting that fresh red cells could be associated with a higher incidence of posttransfusion organ dysfunction.

Among 1,461 children randomly assigned to receive RBC transfusions with either fresh cells (stored for 7 days or less) or standard-issue cells (stored anywhere from 2-42 days), there were no differences in the primary endpoint of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), reported Philip Spinella, MD from Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results do not support current blood management policies that recommend providing fresh red cell units to certain populations of children,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The study findings support those of a systematic review (Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:77-88), whose authors found that “transfusion of fresher RBCs is not associated with decreased risk of death but is associated with higher rates of transfusion reactions and possibly infection.” The authors of the review concluded that “the current evidence does not support a change from current usual transfusion practice.”

Is fresh really better?

The launch of the ABC PICU trial was motivated by laboratory and observational evidence suggesting that older RBCs may be less safe or efficacious than fresh RBCs, especially in vulnerable populations such as critically ill children.

Although physician and institutional practice has been to transfuse fresh RBCs to some pediatric patients, the standard practice among blood banks has been to deliver the oldest stored units first, in an effort to prevent product wastage.

Dr. Spinella and colleagues across 50 centers in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, and Israel enrolled patients who were admitted to a pediatric ICU who received their first RBC transfusion within 7 days of admission and had an expected length of stay after transfusion of more than 24 hours.

The median patient age was 1.8 years for those who received fresh cells, and 1.9 years for those who received usual care.

There were 1,630 transfusions of fresh RBCs stored for a median of 5 days and 1,533 transfusions of standard RBCs stored for a median of 18 days. The median volume of red cell units transfused was 17.5 mL/kg in the fresh group and 16.6 mL/kg in the standard group.

The incidence of NPMODS was 20.2% for fresh-RBC recipients and 18.2% for standard-product recipients. The absolute difference of 2.0% was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences in the timing of NPMODS occurrence between the groups, and no significant differences by patient age (28 days or younger, 29-365 days old, or older than 1 year).

Similarly, there were no differences in NPMODS incidence between the groups by country, although in Canada there was a trend toward a higher incidence of organ dysfunction in the group that received fresh RBCs, Dr. Spinella noted.

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups by admission to the ICU by medical, surgical, cardiac, or trauma services; no differences by quartile of red cell volume transfused; and no differences in mortality rates either in the ICU or the main hospital, or at 28 or 90 days after discharge.

Why no difference?

Seeking explanations for why fresh RBCs did not perform better than older stored cells, Dr. Spinella suggested that changes such as storage lesions that occur over time may not be as clinically relevant as previously supposed.

“Another possibility is that these study patients didn’t need red cells to begin with to improve oxygen delivery,” he said.

Other potential explanations include the possibility that exposure to fresh red cells may be associated with immune suppression because viable white cells may also be present in the product, and that the chronological age of a stored red cell unit may not equate to its biologic or metabolic age or performance, he added.

ABC PICU was supported by Washington University; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian and French governments; and other groups. Dr. Spinella reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AABB 2019

ART traces in donor samples show risk to blood supply

SAN ANTONIO, TEX. – Some HIV-positive individuals on antiretroviral therapy continue to attempt blood donation, for reasons that may include ignorance of the risks of transmission, test-seeking behavior, or other unknown motivations to donate despite knowing their viral status, caution investigators who monitor the nation’s blood supply.

Additionally, evidence of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral agents (ARV) in HIV-negative donors raises concerns about possible risk of transmission from HIV-breakthrough infections, reported Brian S. Custer, PhD, of Vitalant Research Institute.

Dr. Custer and colleagues in the U.S. Transfusion Transmissible Infections Monitoring System (TTIMS) evaluated plasma samples from four large blood collection organizations and found metabolites of drugs typically used in ARV regimens, at concentrations indicating that they had been taken within a week of blood donation.

“What are the motivations of these individuals who are ARV-positive and HIV-positive? Are they using the blood center as a place to monitor their infection status? We just do not know the answer to that, but it does bring back this issue of whether there a form of test seeking going on here,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The findings suggest that current donor health questionnaires and pre-donation screening are not adequate for ascertaining disclosure of HIV status or behaviors that could put the safety of the blood supply in doubt.

Does ‘U’ really equal ‘U’?

The public health message that “undetectable” equals “untransmittable” may help to prevent new infections, but may not translate into transfusion safety, Dr. Custer said.

Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend that infected individuals start on ARV immediately upon receiving a diagnosis. ARV drugs both suppress viremia and alter biomarkers of HIV progression, and may delay the time to antibody seroconversion, which could affect the ability to detect HIV through blood donation screening.

To see whether there is renewed cause for concern about safety of the blood supply, the TTIMS investigators tested for ARV metabolites in donated blood samples as a surrogate for HIV infection.

They looked at 299 HIV-positive plasma samples and 300 samples negative for all testable infections using liquid chromatography–mass spectometry for metabolites of 13 ARVs.

No ARV metabolites could be detected in the HIV-negative samples, but in 299 samples from 463 HIV-positive donors they found that 46 (15.4%) tested positive for ARVs. Of these 46 specimens, 43 were from first-time donors, and 34 were from males. Three samples were from repeat donors.

In all, 41 of the 46 ARV-positive donors would have been considered as potential “elite controllers” – HIV-infected individuals with no detectable viral loads in the absence of therapy – based on HIV-positive serology but negative nucleic acid test (NAT) results.

Samples from five first-time donors tested positive for HIV by both serology and NAT, and also contained ARV metabolites, suggesting that the donors had started ARVs recently, had suboptimal therapy, or were poorly adherent to their regimens.

PrEP use among HIV-negative donors

The investigators also looked at PrEP use in 1494 samples from first-time male donors that tested negative for all markers routinely screened: HIV 1/2, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, HTLV-I/II, West Nile virus, ZIKV, Treponema pallidum and Trypanosoma cruzi.

The donors came from Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, San Francisco, and Washington, all cities with elevated HIV prevalence and active PrEP rollout campaigns.

They tested for analytes to emtricitabine and tenofovir, the two ARV components of the PrEP drug Truvada, and found that nine samples (0.6%) tested positive for PrEP. Of these, three donors had taken PrEP approximately 1 day before donation, two took it 2 days before, and four took it about 4 days before donation.

“There is quite a bit of concern about what this might mean for blood safety.” Dr. Custer said. “There’s a possibility of a breakthrough infection if someone is not PrEP adherent, and would we be able to detect them? Could this be an additional indicator for the risk of transfusion-transmissible infections? Could we identify subgroups of PrEP use in the donor population, and would we see any evidence?”

Mitigation Efforts

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is supporting a 7-year research project to study the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy and PrEP in the United States and Brazil under the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-IV-Pediatric (REDS-IV-P) project.

In addition, an AABB task force has drafted new questions for the donor health questionnaire intended to focus the attention of potential donors on PrEP, postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), and antiretroviral therapy.

In addition to asking about the use of medications on the deferral list, the proposed additions would ask, “In the past 16 weeks, have you taken any medication to prevent an HIV infection?” and “Have you EVER taken any medication to treat an HIV infection?”

TTIMS is supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, NHLBI, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Dr. Custer and all coinvestigators reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: : wit AABB 2019. Abstract PL5-MN4-32

SAN ANTONIO, TEX. – Some HIV-positive individuals on antiretroviral therapy continue to attempt blood donation, for reasons that may include ignorance of the risks of transmission, test-seeking behavior, or other unknown motivations to donate despite knowing their viral status, caution investigators who monitor the nation’s blood supply.

Additionally, evidence of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral agents (ARV) in HIV-negative donors raises concerns about possible risk of transmission from HIV-breakthrough infections, reported Brian S. Custer, PhD, of Vitalant Research Institute.

Dr. Custer and colleagues in the U.S. Transfusion Transmissible Infections Monitoring System (TTIMS) evaluated plasma samples from four large blood collection organizations and found metabolites of drugs typically used in ARV regimens, at concentrations indicating that they had been taken within a week of blood donation.

“What are the motivations of these individuals who are ARV-positive and HIV-positive? Are they using the blood center as a place to monitor their infection status? We just do not know the answer to that, but it does bring back this issue of whether there a form of test seeking going on here,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The findings suggest that current donor health questionnaires and pre-donation screening are not adequate for ascertaining disclosure of HIV status or behaviors that could put the safety of the blood supply in doubt.

Does ‘U’ really equal ‘U’?

The public health message that “undetectable” equals “untransmittable” may help to prevent new infections, but may not translate into transfusion safety, Dr. Custer said.

Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend that infected individuals start on ARV immediately upon receiving a diagnosis. ARV drugs both suppress viremia and alter biomarkers of HIV progression, and may delay the time to antibody seroconversion, which could affect the ability to detect HIV through blood donation screening.

To see whether there is renewed cause for concern about safety of the blood supply, the TTIMS investigators tested for ARV metabolites in donated blood samples as a surrogate for HIV infection.

They looked at 299 HIV-positive plasma samples and 300 samples negative for all testable infections using liquid chromatography–mass spectometry for metabolites of 13 ARVs.

No ARV metabolites could be detected in the HIV-negative samples, but in 299 samples from 463 HIV-positive donors they found that 46 (15.4%) tested positive for ARVs. Of these 46 specimens, 43 were from first-time donors, and 34 were from males. Three samples were from repeat donors.

In all, 41 of the 46 ARV-positive donors would have been considered as potential “elite controllers” – HIV-infected individuals with no detectable viral loads in the absence of therapy – based on HIV-positive serology but negative nucleic acid test (NAT) results.

Samples from five first-time donors tested positive for HIV by both serology and NAT, and also contained ARV metabolites, suggesting that the donors had started ARVs recently, had suboptimal therapy, or were poorly adherent to their regimens.

PrEP use among HIV-negative donors

The investigators also looked at PrEP use in 1494 samples from first-time male donors that tested negative for all markers routinely screened: HIV 1/2, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, HTLV-I/II, West Nile virus, ZIKV, Treponema pallidum and Trypanosoma cruzi.

The donors came from Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, San Francisco, and Washington, all cities with elevated HIV prevalence and active PrEP rollout campaigns.

They tested for analytes to emtricitabine and tenofovir, the two ARV components of the PrEP drug Truvada, and found that nine samples (0.6%) tested positive for PrEP. Of these, three donors had taken PrEP approximately 1 day before donation, two took it 2 days before, and four took it about 4 days before donation.

“There is quite a bit of concern about what this might mean for blood safety.” Dr. Custer said. “There’s a possibility of a breakthrough infection if someone is not PrEP adherent, and would we be able to detect them? Could this be an additional indicator for the risk of transfusion-transmissible infections? Could we identify subgroups of PrEP use in the donor population, and would we see any evidence?”

Mitigation Efforts

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is supporting a 7-year research project to study the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy and PrEP in the United States and Brazil under the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-IV-Pediatric (REDS-IV-P) project.

In addition, an AABB task force has drafted new questions for the donor health questionnaire intended to focus the attention of potential donors on PrEP, postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), and antiretroviral therapy.

In addition to asking about the use of medications on the deferral list, the proposed additions would ask, “In the past 16 weeks, have you taken any medication to prevent an HIV infection?” and “Have you EVER taken any medication to treat an HIV infection?”

TTIMS is supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, NHLBI, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Dr. Custer and all coinvestigators reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: : wit AABB 2019. Abstract PL5-MN4-32

SAN ANTONIO, TEX. – Some HIV-positive individuals on antiretroviral therapy continue to attempt blood donation, for reasons that may include ignorance of the risks of transmission, test-seeking behavior, or other unknown motivations to donate despite knowing their viral status, caution investigators who monitor the nation’s blood supply.

Additionally, evidence of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral agents (ARV) in HIV-negative donors raises concerns about possible risk of transmission from HIV-breakthrough infections, reported Brian S. Custer, PhD, of Vitalant Research Institute.

Dr. Custer and colleagues in the U.S. Transfusion Transmissible Infections Monitoring System (TTIMS) evaluated plasma samples from four large blood collection organizations and found metabolites of drugs typically used in ARV regimens, at concentrations indicating that they had been taken within a week of blood donation.

“What are the motivations of these individuals who are ARV-positive and HIV-positive? Are they using the blood center as a place to monitor their infection status? We just do not know the answer to that, but it does bring back this issue of whether there a form of test seeking going on here,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The findings suggest that current donor health questionnaires and pre-donation screening are not adequate for ascertaining disclosure of HIV status or behaviors that could put the safety of the blood supply in doubt.

Does ‘U’ really equal ‘U’?

The public health message that “undetectable” equals “untransmittable” may help to prevent new infections, but may not translate into transfusion safety, Dr. Custer said.

Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend that infected individuals start on ARV immediately upon receiving a diagnosis. ARV drugs both suppress viremia and alter biomarkers of HIV progression, and may delay the time to antibody seroconversion, which could affect the ability to detect HIV through blood donation screening.

To see whether there is renewed cause for concern about safety of the blood supply, the TTIMS investigators tested for ARV metabolites in donated blood samples as a surrogate for HIV infection.

They looked at 299 HIV-positive plasma samples and 300 samples negative for all testable infections using liquid chromatography–mass spectometry for metabolites of 13 ARVs.

No ARV metabolites could be detected in the HIV-negative samples, but in 299 samples from 463 HIV-positive donors they found that 46 (15.4%) tested positive for ARVs. Of these 46 specimens, 43 were from first-time donors, and 34 were from males. Three samples were from repeat donors.

In all, 41 of the 46 ARV-positive donors would have been considered as potential “elite controllers” – HIV-infected individuals with no detectable viral loads in the absence of therapy – based on HIV-positive serology but negative nucleic acid test (NAT) results.

Samples from five first-time donors tested positive for HIV by both serology and NAT, and also contained ARV metabolites, suggesting that the donors had started ARVs recently, had suboptimal therapy, or were poorly adherent to their regimens.

PrEP use among HIV-negative donors

The investigators also looked at PrEP use in 1494 samples from first-time male donors that tested negative for all markers routinely screened: HIV 1/2, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, HTLV-I/II, West Nile virus, ZIKV, Treponema pallidum and Trypanosoma cruzi.

The donors came from Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, San Francisco, and Washington, all cities with elevated HIV prevalence and active PrEP rollout campaigns.

They tested for analytes to emtricitabine and tenofovir, the two ARV components of the PrEP drug Truvada, and found that nine samples (0.6%) tested positive for PrEP. Of these, three donors had taken PrEP approximately 1 day before donation, two took it 2 days before, and four took it about 4 days before donation.

“There is quite a bit of concern about what this might mean for blood safety.” Dr. Custer said. “There’s a possibility of a breakthrough infection if someone is not PrEP adherent, and would we be able to detect them? Could this be an additional indicator for the risk of transfusion-transmissible infections? Could we identify subgroups of PrEP use in the donor population, and would we see any evidence?”

Mitigation Efforts

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is supporting a 7-year research project to study the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy and PrEP in the United States and Brazil under the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-IV-Pediatric (REDS-IV-P) project.

In addition, an AABB task force has drafted new questions for the donor health questionnaire intended to focus the attention of potential donors on PrEP, postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), and antiretroviral therapy.

In addition to asking about the use of medications on the deferral list, the proposed additions would ask, “In the past 16 weeks, have you taken any medication to prevent an HIV infection?” and “Have you EVER taken any medication to treat an HIV infection?”

TTIMS is supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, NHLBI, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Dr. Custer and all coinvestigators reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: : wit AABB 2019. Abstract PL5-MN4-32

REPORTING FROM AABB 2019

Global blood supply runs low

Nearly two-thirds of countries worldwide have an insufficient supply of blood for transfusion, according to findings from a recent modeling study including 195 countries and territories.

Low- and middle-income countries are most often affected, reported lead author Nicholas Roberts of the University of Washington in Seattle and colleagues. Among all countries in Oceania, south Asia, and eastern, central, and western sub-Saharan Africa, not one had enough blood to meet estimated needs, they noted.

Shortages are attributable to a variety of challenges, including resource constraints, insufficient component production, and a high prevalence of infectious diseases, according to investigators. And existing guidelines, which call for 10-20 donations per 1,000 people in the population, may need to be revised, investigators suggested.

“These estimates are important, as they can be used to guide further investments in blood transfusion services, for analysis of current transfusion practices, and to highlight need for alternatives to transfusions such as antifibrinolytics, blood saving devices, and implementation of blood management systems,” the investigators wrote in Lancet Haematology.

Blood availability was calculated using the 2016 WHO Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability, in which 92% of countries participated. Blood needs were calculated using multiple databases, including the (U.S.) National Inpatient Sample datasets from 2000-2014, the State Inpatient Databases from 2003-2007, and the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study.

The global blood need was almost 305 million blood product units, while the supply totaled approximately 272 million units. These shortages, however, were not distributed equally across the globe. Out of 195 countries, 119 (61%) had an insufficient supply of blood to meet anticipated demand. Within this group, the shortage equated to about 102 million blood product units.

Denmark had the greatest supply of blood products (red blood cell products, platelets, and plasma), at 14,704 units per 100,000 population, compared with South Sudan, the least prepared to meet transfusion needs, with just 46 blood product units available per 100,000 population. This pattern was echoed across the globe; high-income countries were usually better stocked than those with low or middle income.

To meet demands, some of the most affected countries would need to raise their collection goals from single-digit figures to as high as 40 donations per 1,000 population, the investigators advised.

“Many countries face critical undersupply of transfusions, which will become more pronounced as access to care improves,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported having no other financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Roberts N et al. Lancet Haematol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3026(19)30200-5.

Nearly two-thirds of countries worldwide have an insufficient supply of blood for transfusion, according to findings from a recent modeling study including 195 countries and territories.

Low- and middle-income countries are most often affected, reported lead author Nicholas Roberts of the University of Washington in Seattle and colleagues. Among all countries in Oceania, south Asia, and eastern, central, and western sub-Saharan Africa, not one had enough blood to meet estimated needs, they noted.

Shortages are attributable to a variety of challenges, including resource constraints, insufficient component production, and a high prevalence of infectious diseases, according to investigators. And existing guidelines, which call for 10-20 donations per 1,000 people in the population, may need to be revised, investigators suggested.

“These estimates are important, as they can be used to guide further investments in blood transfusion services, for analysis of current transfusion practices, and to highlight need for alternatives to transfusions such as antifibrinolytics, blood saving devices, and implementation of blood management systems,” the investigators wrote in Lancet Haematology.

Blood availability was calculated using the 2016 WHO Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability, in which 92% of countries participated. Blood needs were calculated using multiple databases, including the (U.S.) National Inpatient Sample datasets from 2000-2014, the State Inpatient Databases from 2003-2007, and the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study.

The global blood need was almost 305 million blood product units, while the supply totaled approximately 272 million units. These shortages, however, were not distributed equally across the globe. Out of 195 countries, 119 (61%) had an insufficient supply of blood to meet anticipated demand. Within this group, the shortage equated to about 102 million blood product units.

Denmark had the greatest supply of blood products (red blood cell products, platelets, and plasma), at 14,704 units per 100,000 population, compared with South Sudan, the least prepared to meet transfusion needs, with just 46 blood product units available per 100,000 population. This pattern was echoed across the globe; high-income countries were usually better stocked than those with low or middle income.

To meet demands, some of the most affected countries would need to raise their collection goals from single-digit figures to as high as 40 donations per 1,000 population, the investigators advised.

“Many countries face critical undersupply of transfusions, which will become more pronounced as access to care improves,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported having no other financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Roberts N et al. Lancet Haematol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3026(19)30200-5.

Nearly two-thirds of countries worldwide have an insufficient supply of blood for transfusion, according to findings from a recent modeling study including 195 countries and territories.

Low- and middle-income countries are most often affected, reported lead author Nicholas Roberts of the University of Washington in Seattle and colleagues. Among all countries in Oceania, south Asia, and eastern, central, and western sub-Saharan Africa, not one had enough blood to meet estimated needs, they noted.

Shortages are attributable to a variety of challenges, including resource constraints, insufficient component production, and a high prevalence of infectious diseases, according to investigators. And existing guidelines, which call for 10-20 donations per 1,000 people in the population, may need to be revised, investigators suggested.

“These estimates are important, as they can be used to guide further investments in blood transfusion services, for analysis of current transfusion practices, and to highlight need for alternatives to transfusions such as antifibrinolytics, blood saving devices, and implementation of blood management systems,” the investigators wrote in Lancet Haematology.

Blood availability was calculated using the 2016 WHO Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability, in which 92% of countries participated. Blood needs were calculated using multiple databases, including the (U.S.) National Inpatient Sample datasets from 2000-2014, the State Inpatient Databases from 2003-2007, and the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study.

The global blood need was almost 305 million blood product units, while the supply totaled approximately 272 million units. These shortages, however, were not distributed equally across the globe. Out of 195 countries, 119 (61%) had an insufficient supply of blood to meet anticipated demand. Within this group, the shortage equated to about 102 million blood product units.

Denmark had the greatest supply of blood products (red blood cell products, platelets, and plasma), at 14,704 units per 100,000 population, compared with South Sudan, the least prepared to meet transfusion needs, with just 46 blood product units available per 100,000 population. This pattern was echoed across the globe; high-income countries were usually better stocked than those with low or middle income.

To meet demands, some of the most affected countries would need to raise their collection goals from single-digit figures to as high as 40 donations per 1,000 population, the investigators advised.

“Many countries face critical undersupply of transfusions, which will become more pronounced as access to care improves,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported having no other financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Roberts N et al. Lancet Haematol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3026(19)30200-5.

FROM LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Mitapivat elicits positive response in pyruvate kinase deficiency

Mitapivat showed positive safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency, according to results from a phase 2 trial.

After 24 weeks of treatment, the therapy was associated with a rapid rise in hemoglobin levels in 50% of study participants, while the majority of toxicities reported were transient and low grade.

“The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety and side-effect profile of mitapivat administration in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency,” wrote Rachael F. Grace, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coinvestigators. The findings were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The uncontrolled study included 52 adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency who were not undergoing regular transfusions.