User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Opioid use cut nearly 50% for urologic oncology surgery patients

PHOENIX – Opioid use in urologic oncology patients dropped by 46% after one high-volume surgical center introduced changes to order sets and adopted new patient communication strategies, a researcher has reported.

The changes, which promoted opioid-sparing pain regimens, led to a substantial drop in postoperative opioid use with no compromise in pain control, according to Kerri Stevenson, a nurse practitioner with Stanford Health Care.

“Patients can be successfully managed with minimal opioid medication,” Ms. Stevenson said at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

However, “it takes a multidisciplinary team for effective change to occur – this cannot be done in silos,” she told attendees at the meeting.

Seeking to reduce their reliance on opioids to manage postoperative pain, Ms. Stevenson and her colleagues set out to reduce opioid use by 50%, from a baseline morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) of 95.1 in June to September 2017 to a target of 47.5 by March 2018.

The actual MEDD at the end of the quality improvement project was 51.5, a 46% reduction that was just shy of that goal, she reported.

Factors fueling opioid use included patient expectations that they would be used and the belief that adjunct medications were not as effective as opioids, Dr. Stevenson found in a team survey.

“We decided to target those,” she said. “Our key drivers were really focused on appropriate prescriptions, increasing patient and provider awareness, standardizing our pathways, and setting expectations.”

To tackle the problem, they revised EMR order sets to default to selection of adjunct medications, educated providers, and introduced new patient communication strategies.

Instead of asking “Would you like me to bring you some oxycodone?” providers would instead start by asking about the patient’s current pain control medications and whether they were working well. When prescribed, opioids should be started at lower doses and escalated only if needed.

“Once we started our interventions, we noticed an immediate effect,” Ms. Stevenson.

The decreases were consistent across a range of surgery types. For example, the MEDD dropped to 55.1 with robotic prostatectomy, a procedure with a 1-day admission and very small incisions, and to 50.6 for open radical cystectomy, which involves a large incision and a stay of approximately 4 days, she said.

To address concerns that they might just be undertreating patients, investigators looked retrospectively at pain scores. They saw no differences pre- and post intervention in pain or anxiety scores within the first 24-48 hours post procedure, Ms. Stevenson reported.

Ms. Stevenson had no disclosures related to the presentation. Coauthor Jay Bakul Shah, MD of Stanford Health Care reported a consulting or advisory role with Pacira Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Stevenson K et al. Quality Care Symposium, Abstract 269.

PHOENIX – Opioid use in urologic oncology patients dropped by 46% after one high-volume surgical center introduced changes to order sets and adopted new patient communication strategies, a researcher has reported.

The changes, which promoted opioid-sparing pain regimens, led to a substantial drop in postoperative opioid use with no compromise in pain control, according to Kerri Stevenson, a nurse practitioner with Stanford Health Care.

“Patients can be successfully managed with minimal opioid medication,” Ms. Stevenson said at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

However, “it takes a multidisciplinary team for effective change to occur – this cannot be done in silos,” she told attendees at the meeting.

Seeking to reduce their reliance on opioids to manage postoperative pain, Ms. Stevenson and her colleagues set out to reduce opioid use by 50%, from a baseline morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) of 95.1 in June to September 2017 to a target of 47.5 by March 2018.

The actual MEDD at the end of the quality improvement project was 51.5, a 46% reduction that was just shy of that goal, she reported.

Factors fueling opioid use included patient expectations that they would be used and the belief that adjunct medications were not as effective as opioids, Dr. Stevenson found in a team survey.

“We decided to target those,” she said. “Our key drivers were really focused on appropriate prescriptions, increasing patient and provider awareness, standardizing our pathways, and setting expectations.”

To tackle the problem, they revised EMR order sets to default to selection of adjunct medications, educated providers, and introduced new patient communication strategies.

Instead of asking “Would you like me to bring you some oxycodone?” providers would instead start by asking about the patient’s current pain control medications and whether they were working well. When prescribed, opioids should be started at lower doses and escalated only if needed.

“Once we started our interventions, we noticed an immediate effect,” Ms. Stevenson.

The decreases were consistent across a range of surgery types. For example, the MEDD dropped to 55.1 with robotic prostatectomy, a procedure with a 1-day admission and very small incisions, and to 50.6 for open radical cystectomy, which involves a large incision and a stay of approximately 4 days, she said.

To address concerns that they might just be undertreating patients, investigators looked retrospectively at pain scores. They saw no differences pre- and post intervention in pain or anxiety scores within the first 24-48 hours post procedure, Ms. Stevenson reported.

Ms. Stevenson had no disclosures related to the presentation. Coauthor Jay Bakul Shah, MD of Stanford Health Care reported a consulting or advisory role with Pacira Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Stevenson K et al. Quality Care Symposium, Abstract 269.

PHOENIX – Opioid use in urologic oncology patients dropped by 46% after one high-volume surgical center introduced changes to order sets and adopted new patient communication strategies, a researcher has reported.

The changes, which promoted opioid-sparing pain regimens, led to a substantial drop in postoperative opioid use with no compromise in pain control, according to Kerri Stevenson, a nurse practitioner with Stanford Health Care.

“Patients can be successfully managed with minimal opioid medication,” Ms. Stevenson said at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

However, “it takes a multidisciplinary team for effective change to occur – this cannot be done in silos,” she told attendees at the meeting.

Seeking to reduce their reliance on opioids to manage postoperative pain, Ms. Stevenson and her colleagues set out to reduce opioid use by 50%, from a baseline morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) of 95.1 in June to September 2017 to a target of 47.5 by March 2018.

The actual MEDD at the end of the quality improvement project was 51.5, a 46% reduction that was just shy of that goal, she reported.

Factors fueling opioid use included patient expectations that they would be used and the belief that adjunct medications were not as effective as opioids, Dr. Stevenson found in a team survey.

“We decided to target those,” she said. “Our key drivers were really focused on appropriate prescriptions, increasing patient and provider awareness, standardizing our pathways, and setting expectations.”

To tackle the problem, they revised EMR order sets to default to selection of adjunct medications, educated providers, and introduced new patient communication strategies.

Instead of asking “Would you like me to bring you some oxycodone?” providers would instead start by asking about the patient’s current pain control medications and whether they were working well. When prescribed, opioids should be started at lower doses and escalated only if needed.

“Once we started our interventions, we noticed an immediate effect,” Ms. Stevenson.

The decreases were consistent across a range of surgery types. For example, the MEDD dropped to 55.1 with robotic prostatectomy, a procedure with a 1-day admission and very small incisions, and to 50.6 for open radical cystectomy, which involves a large incision and a stay of approximately 4 days, she said.

To address concerns that they might just be undertreating patients, investigators looked retrospectively at pain scores. They saw no differences pre- and post intervention in pain or anxiety scores within the first 24-48 hours post procedure, Ms. Stevenson reported.

Ms. Stevenson had no disclosures related to the presentation. Coauthor Jay Bakul Shah, MD of Stanford Health Care reported a consulting or advisory role with Pacira Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Stevenson K et al. Quality Care Symposium, Abstract 269.

REPORTING FROM THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Substantial reductions in postoperative opioid use might be achievable through strategies that promote opioid-sparing pain regimens.

Major finding: Postoperative opioid use dropped 46% for urologic oncology patients after changing default order sets, introducing new patient communication strategies, and educating providers.

Study details: An analysis of opioid prescribing before and after introduction of a quality improvement project at one high-volume surgical center.

Disclosures: One study coauthor reported a consulting or advisory role with Pacira Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Stevenson K et al. Quality Care Symposium, Abstract 269.

Gastric banding, metformin “equal” for slowing early T2DM progression

BERLIN – Gastric banding surgery and metformin produce similar improvements in insulin sensitivity and parameters indicative of preserved beta-cell function in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), according to the results of a study conducted by the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) Consortium.

“Both interventions resulted in about 50% improvements in insulin sensitivity at 1 year, which was attenuated at 2 years,” reported study investigator Thomas Buchanan, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“The beta-cell responses fell in a pattern that maintained relatively, but not perfectly, stable compensation for insulin resistance,” he added.

Although glucose levels improved “only slightly,” he said, “acute compensation to glucose improved significantly with gastric banding and beta-cell compensation at maximal stimulation fell significantly with metformin.”

Results of the BetaFat (Beta Cell Restoration through Fat Mitigation) study, which are now published online in Diabetes Care, also showed that greater weight loss could be achieved with surgery versus metformin, with a 8.9 kg difference between the groups at 2 years (10.6 vs. 1.7 kg, respectively, P less than .01).

HDL cholesterol levels also rose with both interventions, and gastric banding resulted in a greater effect on very low–density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as serum ALT, Dr. Buchanan said.

The BetaFat study is one of three “proof-of principle” studies currently being conducted by the RISE Consortium in patients with IGT, sometimes called prediabetes, and T2DM, explained Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB, the chair for the RISE studies.

The other two multicenter, randomized trials being conducted by the RISE Consortium are looking at the effects of medications on preserving beta-cell function in pediatric/adolescent (10-19 years) and adult (21-65 years) populations with IGT or mild, recently diagnosed T2DM. The design, and some results, of these trials can be viewed on a dedicated section of the Diabetes Care website.

Beta-cell function is being assessed using “state-of-the-art” methods; the coprimary endpoint of the surgery versus metformin study was the steady state C-peptide level and acute C-peptide response at maximal glycemia measured using a hyperglycemic “clamp.”

The goal of the RISE studies is to test different approaches to preserve beta-cell function. It is designed to answer the question of which is more effective in this setting: sustained weight loss through gastric banding such as in the BetaFat study or medication.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged 21-65 years, had a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2, and had IGT or a diagnosis of T2DM within the past year for which they had received no diabetes medication at recruitment.

A total of 88 individuals were randomized with exactly half undergoing gastric banding. This consisted of a gastric band placed laparoscopically and adjusted every 2 months for the first year, and then every 3 months for the following year depending on symptoms and weight change.

Normoglycemia was observed in none of the study subjects at baseline but in 22% and 15% of those who had gastric banding or metformin, respectively, at 2 years (P = .66).

As for tolerability, five patients who underwent gastric banding experienced serious adverse events, of which two were caused by band slippage and three were caused other reasons. In the metformin arm, there were two serious adverse events, both unrelated to the medication.

“Gastric banding and metformin offered approximately equal approaches for improving insulin sensitivity in adults with mild to moderate obesity and impaired glucose tolerance or early, mild type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Buchanan concluded. “The predominant beta-cell response was a reduction in secretion to maintain a relatively constant compensation for insulin resistance, with only a small improvement in glucose. Whether these interventions will have different effects on beta-cell function over the long-term remains to be determined.”

Commenting on the study, Roy Taylor, MD, professor of medicine and metabolism at Newcastle University (England), noted that the changes in the lipid and liver parameters were important. Fasting plasma triglyceride levels fell from 1.3 mmol/L at baseline to 1.1 mmol/L at 2 years with surgery but stayed more or less the same with metformin (1.23 mmol/L and 1.28 mmol/L; P less than .009 comparing surgery and metformin groups at 2 years). Change in ALT levels were also significant comparing baseline values with results at 2 years, decreasing in the surgical group to a greater extent than in the metformin groups.

“There’s a really important message here, the predictors of a better response to the weight loss [i.e. changes in triglycerides and liver enzymes] are all there,” Dr. Taylor observed. “RISE has looked at 2 years of this effect, but the conversion to type 2 diabetes is probably going to happen over a longer time course.”

He added that “although the primary outcome measure of change in insulin secretion was not achieved, the writing is on the wall. These people, provided they maintain their weight loss, are likely to succeed. We see all the hallmarks of a successful outcome for the weight loss group – remove the primary driver for type 2 diabetes, and that group is on track.”

The RISE Consortium conducted the BetaFat study. The RISE Consortium is supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health. Further support came from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, the American Diabetes Association, and Allergan. Additional donations of supplies were provided by Allergan, Apollo Endosurgery, Abbott, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Buchanan reported receiving research funding from Allergan and Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. Taylor had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Buchanan T et al. EASD 2018, Session S09; Xiang AH et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Oct; dc181662.

BERLIN – Gastric banding surgery and metformin produce similar improvements in insulin sensitivity and parameters indicative of preserved beta-cell function in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), according to the results of a study conducted by the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) Consortium.

“Both interventions resulted in about 50% improvements in insulin sensitivity at 1 year, which was attenuated at 2 years,” reported study investigator Thomas Buchanan, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“The beta-cell responses fell in a pattern that maintained relatively, but not perfectly, stable compensation for insulin resistance,” he added.

Although glucose levels improved “only slightly,” he said, “acute compensation to glucose improved significantly with gastric banding and beta-cell compensation at maximal stimulation fell significantly with metformin.”

Results of the BetaFat (Beta Cell Restoration through Fat Mitigation) study, which are now published online in Diabetes Care, also showed that greater weight loss could be achieved with surgery versus metformin, with a 8.9 kg difference between the groups at 2 years (10.6 vs. 1.7 kg, respectively, P less than .01).

HDL cholesterol levels also rose with both interventions, and gastric banding resulted in a greater effect on very low–density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as serum ALT, Dr. Buchanan said.

The BetaFat study is one of three “proof-of principle” studies currently being conducted by the RISE Consortium in patients with IGT, sometimes called prediabetes, and T2DM, explained Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB, the chair for the RISE studies.

The other two multicenter, randomized trials being conducted by the RISE Consortium are looking at the effects of medications on preserving beta-cell function in pediatric/adolescent (10-19 years) and adult (21-65 years) populations with IGT or mild, recently diagnosed T2DM. The design, and some results, of these trials can be viewed on a dedicated section of the Diabetes Care website.

Beta-cell function is being assessed using “state-of-the-art” methods; the coprimary endpoint of the surgery versus metformin study was the steady state C-peptide level and acute C-peptide response at maximal glycemia measured using a hyperglycemic “clamp.”

The goal of the RISE studies is to test different approaches to preserve beta-cell function. It is designed to answer the question of which is more effective in this setting: sustained weight loss through gastric banding such as in the BetaFat study or medication.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged 21-65 years, had a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2, and had IGT or a diagnosis of T2DM within the past year for which they had received no diabetes medication at recruitment.

A total of 88 individuals were randomized with exactly half undergoing gastric banding. This consisted of a gastric band placed laparoscopically and adjusted every 2 months for the first year, and then every 3 months for the following year depending on symptoms and weight change.

Normoglycemia was observed in none of the study subjects at baseline but in 22% and 15% of those who had gastric banding or metformin, respectively, at 2 years (P = .66).

As for tolerability, five patients who underwent gastric banding experienced serious adverse events, of which two were caused by band slippage and three were caused other reasons. In the metformin arm, there were two serious adverse events, both unrelated to the medication.

“Gastric banding and metformin offered approximately equal approaches for improving insulin sensitivity in adults with mild to moderate obesity and impaired glucose tolerance or early, mild type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Buchanan concluded. “The predominant beta-cell response was a reduction in secretion to maintain a relatively constant compensation for insulin resistance, with only a small improvement in glucose. Whether these interventions will have different effects on beta-cell function over the long-term remains to be determined.”

Commenting on the study, Roy Taylor, MD, professor of medicine and metabolism at Newcastle University (England), noted that the changes in the lipid and liver parameters were important. Fasting plasma triglyceride levels fell from 1.3 mmol/L at baseline to 1.1 mmol/L at 2 years with surgery but stayed more or less the same with metformin (1.23 mmol/L and 1.28 mmol/L; P less than .009 comparing surgery and metformin groups at 2 years). Change in ALT levels were also significant comparing baseline values with results at 2 years, decreasing in the surgical group to a greater extent than in the metformin groups.

“There’s a really important message here, the predictors of a better response to the weight loss [i.e. changes in triglycerides and liver enzymes] are all there,” Dr. Taylor observed. “RISE has looked at 2 years of this effect, but the conversion to type 2 diabetes is probably going to happen over a longer time course.”

He added that “although the primary outcome measure of change in insulin secretion was not achieved, the writing is on the wall. These people, provided they maintain their weight loss, are likely to succeed. We see all the hallmarks of a successful outcome for the weight loss group – remove the primary driver for type 2 diabetes, and that group is on track.”

The RISE Consortium conducted the BetaFat study. The RISE Consortium is supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health. Further support came from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, the American Diabetes Association, and Allergan. Additional donations of supplies were provided by Allergan, Apollo Endosurgery, Abbott, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Buchanan reported receiving research funding from Allergan and Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. Taylor had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Buchanan T et al. EASD 2018, Session S09; Xiang AH et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Oct; dc181662.

BERLIN – Gastric banding surgery and metformin produce similar improvements in insulin sensitivity and parameters indicative of preserved beta-cell function in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), according to the results of a study conducted by the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) Consortium.

“Both interventions resulted in about 50% improvements in insulin sensitivity at 1 year, which was attenuated at 2 years,” reported study investigator Thomas Buchanan, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“The beta-cell responses fell in a pattern that maintained relatively, but not perfectly, stable compensation for insulin resistance,” he added.

Although glucose levels improved “only slightly,” he said, “acute compensation to glucose improved significantly with gastric banding and beta-cell compensation at maximal stimulation fell significantly with metformin.”

Results of the BetaFat (Beta Cell Restoration through Fat Mitigation) study, which are now published online in Diabetes Care, also showed that greater weight loss could be achieved with surgery versus metformin, with a 8.9 kg difference between the groups at 2 years (10.6 vs. 1.7 kg, respectively, P less than .01).

HDL cholesterol levels also rose with both interventions, and gastric banding resulted in a greater effect on very low–density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as serum ALT, Dr. Buchanan said.

The BetaFat study is one of three “proof-of principle” studies currently being conducted by the RISE Consortium in patients with IGT, sometimes called prediabetes, and T2DM, explained Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB, the chair for the RISE studies.

The other two multicenter, randomized trials being conducted by the RISE Consortium are looking at the effects of medications on preserving beta-cell function in pediatric/adolescent (10-19 years) and adult (21-65 years) populations with IGT or mild, recently diagnosed T2DM. The design, and some results, of these trials can be viewed on a dedicated section of the Diabetes Care website.

Beta-cell function is being assessed using “state-of-the-art” methods; the coprimary endpoint of the surgery versus metformin study was the steady state C-peptide level and acute C-peptide response at maximal glycemia measured using a hyperglycemic “clamp.”

The goal of the RISE studies is to test different approaches to preserve beta-cell function. It is designed to answer the question of which is more effective in this setting: sustained weight loss through gastric banding such as in the BetaFat study or medication.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged 21-65 years, had a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2, and had IGT or a diagnosis of T2DM within the past year for which they had received no diabetes medication at recruitment.

A total of 88 individuals were randomized with exactly half undergoing gastric banding. This consisted of a gastric band placed laparoscopically and adjusted every 2 months for the first year, and then every 3 months for the following year depending on symptoms and weight change.

Normoglycemia was observed in none of the study subjects at baseline but in 22% and 15% of those who had gastric banding or metformin, respectively, at 2 years (P = .66).

As for tolerability, five patients who underwent gastric banding experienced serious adverse events, of which two were caused by band slippage and three were caused other reasons. In the metformin arm, there were two serious adverse events, both unrelated to the medication.

“Gastric banding and metformin offered approximately equal approaches for improving insulin sensitivity in adults with mild to moderate obesity and impaired glucose tolerance or early, mild type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Buchanan concluded. “The predominant beta-cell response was a reduction in secretion to maintain a relatively constant compensation for insulin resistance, with only a small improvement in glucose. Whether these interventions will have different effects on beta-cell function over the long-term remains to be determined.”

Commenting on the study, Roy Taylor, MD, professor of medicine and metabolism at Newcastle University (England), noted that the changes in the lipid and liver parameters were important. Fasting plasma triglyceride levels fell from 1.3 mmol/L at baseline to 1.1 mmol/L at 2 years with surgery but stayed more or less the same with metformin (1.23 mmol/L and 1.28 mmol/L; P less than .009 comparing surgery and metformin groups at 2 years). Change in ALT levels were also significant comparing baseline values with results at 2 years, decreasing in the surgical group to a greater extent than in the metformin groups.

“There’s a really important message here, the predictors of a better response to the weight loss [i.e. changes in triglycerides and liver enzymes] are all there,” Dr. Taylor observed. “RISE has looked at 2 years of this effect, but the conversion to type 2 diabetes is probably going to happen over a longer time course.”

He added that “although the primary outcome measure of change in insulin secretion was not achieved, the writing is on the wall. These people, provided they maintain their weight loss, are likely to succeed. We see all the hallmarks of a successful outcome for the weight loss group – remove the primary driver for type 2 diabetes, and that group is on track.”

The RISE Consortium conducted the BetaFat study. The RISE Consortium is supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health. Further support came from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, the American Diabetes Association, and Allergan. Additional donations of supplies were provided by Allergan, Apollo Endosurgery, Abbott, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Buchanan reported receiving research funding from Allergan and Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. Taylor had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Buchanan T et al. EASD 2018, Session S09; Xiang AH et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Oct; dc181662.

REPORTING FROM EASD 2018

Key clinical point: Over 2 years, gastric banding surgery and metformin produced similar improvements in insulin sensitivity and parameters suggestive of preserved beta-cell function in patients with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Around a 50% improvement in insulin sensitivity was seen in both study groups at 1 year with attenuation of the effect at 2 years.

Study details: The BetaFat study included 88 obese adults with impaired glucose tolerance or newly diagnosed early type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was part of the RISE studies, which are supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health. Further support comes from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, the American Diabetes Association, and Allergan. Additional donations of supplies are provided by Allergan, Apollo Endosurgery, Abbott Laboratories, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Buchanan reported research funding from Allergan and Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. Taylor had no conflicts of interest.

Sources: Buchanan T et al. EASD 2018, Session S09; Xiang AH et al. Diabetes Care. 2018 Oct; dc181662.

Employer health insurance: Deductibles rising faster than wages

Health insurance deductibles have risen much faster than average wages over the last 10 years, according to the latest Employer Health Benefit Survey released by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“The share of workers in plans with a general annual deductible has gone from 59% to 85%, and I think even more notably, the average deductible has more than doubled from $735 to $1,573 and deductibles have risen more markedly in smaller firms,” Drew Altman, president and CEO of the KFF said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“These two trends combine for an effective 212% increase in worker deductibles over the past decade, and that is 8 times the increase in workers’ wages during the same period, which for me is the most important number,” he said.

Employer health care costs generally have remained stable, according to the annual survey, now in its 20th year. Annual family premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance rose 5% to an average $19,616 in 2018, extending a 7-year run of moderate increases. The average premium paid by the employee is $5,547.

For a single individual, the average premium increased 3% to $6,896, with employees contributing an average of $1,186.

Although the year-over-year comparison has a premiums increase comparable to that of wages (2.6%) and inflation ($2.5%), over time, premiums are rising much faster.

KFF noted that 85% of employees have a deductible in their plan, up from 81% last year and 59% a decade ago. About 152 million Americans are covered by an employer-sponsored plan.

“Health care costs absolutely remain a burden for employers, but they are a bigger problem for workers as their cost sharing has been rising much faster than their wages have been rising in recent years,” Mr. Altman said.

The survey found that 70% of large employers offer some kind of complete health risk assessments and 38% offer incentives for workers to participate in these programs, with the value of incentives reaching $500 or more.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 Employer Health Benefits.

Health insurance deductibles have risen much faster than average wages over the last 10 years, according to the latest Employer Health Benefit Survey released by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“The share of workers in plans with a general annual deductible has gone from 59% to 85%, and I think even more notably, the average deductible has more than doubled from $735 to $1,573 and deductibles have risen more markedly in smaller firms,” Drew Altman, president and CEO of the KFF said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“These two trends combine for an effective 212% increase in worker deductibles over the past decade, and that is 8 times the increase in workers’ wages during the same period, which for me is the most important number,” he said.

Employer health care costs generally have remained stable, according to the annual survey, now in its 20th year. Annual family premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance rose 5% to an average $19,616 in 2018, extending a 7-year run of moderate increases. The average premium paid by the employee is $5,547.

For a single individual, the average premium increased 3% to $6,896, with employees contributing an average of $1,186.

Although the year-over-year comparison has a premiums increase comparable to that of wages (2.6%) and inflation ($2.5%), over time, premiums are rising much faster.

KFF noted that 85% of employees have a deductible in their plan, up from 81% last year and 59% a decade ago. About 152 million Americans are covered by an employer-sponsored plan.

“Health care costs absolutely remain a burden for employers, but they are a bigger problem for workers as their cost sharing has been rising much faster than their wages have been rising in recent years,” Mr. Altman said.

The survey found that 70% of large employers offer some kind of complete health risk assessments and 38% offer incentives for workers to participate in these programs, with the value of incentives reaching $500 or more.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 Employer Health Benefits.

Health insurance deductibles have risen much faster than average wages over the last 10 years, according to the latest Employer Health Benefit Survey released by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“The share of workers in plans with a general annual deductible has gone from 59% to 85%, and I think even more notably, the average deductible has more than doubled from $735 to $1,573 and deductibles have risen more markedly in smaller firms,” Drew Altman, president and CEO of the KFF said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“These two trends combine for an effective 212% increase in worker deductibles over the past decade, and that is 8 times the increase in workers’ wages during the same period, which for me is the most important number,” he said.

Employer health care costs generally have remained stable, according to the annual survey, now in its 20th year. Annual family premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance rose 5% to an average $19,616 in 2018, extending a 7-year run of moderate increases. The average premium paid by the employee is $5,547.

For a single individual, the average premium increased 3% to $6,896, with employees contributing an average of $1,186.

Although the year-over-year comparison has a premiums increase comparable to that of wages (2.6%) and inflation ($2.5%), over time, premiums are rising much faster.

KFF noted that 85% of employees have a deductible in their plan, up from 81% last year and 59% a decade ago. About 152 million Americans are covered by an employer-sponsored plan.

“Health care costs absolutely remain a burden for employers, but they are a bigger problem for workers as their cost sharing has been rising much faster than their wages have been rising in recent years,” Mr. Altman said.

The survey found that 70% of large employers offer some kind of complete health risk assessments and 38% offer incentives for workers to participate in these programs, with the value of incentives reaching $500 or more.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 Employer Health Benefits.

Key clinical point: The average employee deductible rose from $735 to $1,573 in the last decade.

Major finding: Deductibles have risen 8 times faster than wages since 2008.

Study details: Kaiser Family Foundation surveyed 4,070 randomly selected nonfederal public and private firms with three or more employees; 2,160 responded to the full survey and 1,910 responded to a single question about offering coverage.

Disclosures: No financial conflicts of interest reported.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 Employer Health Benefits.

This is a drill

She had fallen on a garden implement, lacerating her superficial femoral artery. She used her cell phone to call 911. Thanks to an alert EMS crew and the Stop the Bleed training they recently received, a tourniquet was placed without delay. She got to our trauma bay in about 15 minutes after the tourniquet was applied. Although the patient made it abundantly clear that she was in pain, she was stable with moderate tachycardia and a good blood pressure.

Our trauma team leaped into action. The leader took report from the EMS while two nurses and a second surgeon assessed the patient, got her clothes cut off, and applied monitors. A third nurse got a second IV going. Primary survey was done in less than 90 seconds. The patient then underwent a focused exam including a log roll for back injuries.

The leg wound was still oozing a bit, so a second tourniquet was called for and pressure applied until it could be acquired. The patient was given 5 mg of morphine sulfate, which calmed her down a bit. Labs and x-rays were done quickly. The nursing staff suggested a tetanus booster, and the second surgeon who had gotten a basic past medical history suggested vancomycin since the patient said she was allergic to penicillin. Fifteen minutes after she hit the trauma bay, she was on her way to the OR for exploration, debridement, and vascular repair of her injury.

This was all done by four M2 medical students and five N4 nursing students, none of whom had had previous experience with this type of trauma patient

The students were managing this trauma situation in the simulation center of their medical school with four staff watching. This was their second run through for the afternoon. At debriefing, they compared their work on the first trauma of the day (a stab wound to the right chest) to their second attempt. They were satisfied with their efforts and so were we, the faculty who ran the simulation. Comparing their response to those I’ve seen in real life, I’d say these students understood their roles and responsibilities as well as the sort of thrown-together teams I’ve seen at places where trauma is not the main focus. While these young men and women are in the early stage of training and not ready for a real-world trauma emergency, they have gained knowledge about this kind of situation that I didn’t see until I was in residency and beyond. The times they are a-changing.

A couple of days later I was in Rochester, Minn., attending an American College of Surgeons Advanced Education Institute (ACS/AEI) course on simulations. At the end of that course, we participants were challenged by a manikin in extremis. Everyone there was an expert, had an advanced degree, had some experience in simulation, or were surgeons interested in simulation. I found that, even though this was a simulation and the patient was only a pretend human being, my adrenal cortex performed almost as if I were doing a real resuscitation. Previous training I’d had on teamwork, crew resource management, and ACLS all kicked in, and we got it done. But interestingly, we weren’t perfect. We debriefed and found that, even at our level of experience and training, a simple simulation could be very instructive. Seeing/doing is believing.

High-tech skills in high-risk occupations are well served by simulation training. Much of the airline piloting training is done by simulation. It works well for aviation, nuclear reactors, high voltage line work, and medicine. Most of these disciplines have embraced simulation as an essential part of training. Simulation is part of many surgical training programs, but it has other uses.

When was the last time you practiced a trauma resuscitation, an ultrasound fine-needle biopsy, laparoscopic maneuvers, or an unusual technique that you seldom perform, but when needed, must be pulled off very well? Most of us taking this simulation course agreed that time, money, and ego may get in the way of maintaining those skills for those rare instances when they are needed. Surgeons might want to consider simulation to keep some of our rarely used skills from getting rusty.

If you’re going to make a costly error, I would very much like you to do it on a piece of plastic, not on a patient. There are no consequences for messing up a procedure on a manikin and this kind of practice might teach you something critical. Practicing reduces stress and improves the performance of those placed on the spot by real-life events. Do you think Captain “Sully” Sullenberger could have landed that airliner in the Hudson River safely if he hadn’t practiced with countless mind-numbingly complex simulations? Sure, luck plays a part, and innate ability plays a part. But skill, knowledge, and practice are your best bet when all the eyes in the room swivel to you in a moment of crisis.

You may think that simulators have to cost $100,000 and be completely realistic to do the job. That’s not true. A banana, orange, or stick of butter can be fabulous sims for a med student. Felt and cardboard can make a realistic cricothyroidotomy model.

Surgeons all over the country are using simulation training to learn how to be better without getting real blood on their shoes. If you haven’t participated in a training simulation recently, I double-dog dare you to try it and tell me you found it without merit. The ACS Surgical Simulation Summit is being held in March 2019 in Chicago. You might want to check that out.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Salina, and Coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

She had fallen on a garden implement, lacerating her superficial femoral artery. She used her cell phone to call 911. Thanks to an alert EMS crew and the Stop the Bleed training they recently received, a tourniquet was placed without delay. She got to our trauma bay in about 15 minutes after the tourniquet was applied. Although the patient made it abundantly clear that she was in pain, she was stable with moderate tachycardia and a good blood pressure.

Our trauma team leaped into action. The leader took report from the EMS while two nurses and a second surgeon assessed the patient, got her clothes cut off, and applied monitors. A third nurse got a second IV going. Primary survey was done in less than 90 seconds. The patient then underwent a focused exam including a log roll for back injuries.

The leg wound was still oozing a bit, so a second tourniquet was called for and pressure applied until it could be acquired. The patient was given 5 mg of morphine sulfate, which calmed her down a bit. Labs and x-rays were done quickly. The nursing staff suggested a tetanus booster, and the second surgeon who had gotten a basic past medical history suggested vancomycin since the patient said she was allergic to penicillin. Fifteen minutes after she hit the trauma bay, she was on her way to the OR for exploration, debridement, and vascular repair of her injury.

This was all done by four M2 medical students and five N4 nursing students, none of whom had had previous experience with this type of trauma patient

The students were managing this trauma situation in the simulation center of their medical school with four staff watching. This was their second run through for the afternoon. At debriefing, they compared their work on the first trauma of the day (a stab wound to the right chest) to their second attempt. They were satisfied with their efforts and so were we, the faculty who ran the simulation. Comparing their response to those I’ve seen in real life, I’d say these students understood their roles and responsibilities as well as the sort of thrown-together teams I’ve seen at places where trauma is not the main focus. While these young men and women are in the early stage of training and not ready for a real-world trauma emergency, they have gained knowledge about this kind of situation that I didn’t see until I was in residency and beyond. The times they are a-changing.

A couple of days later I was in Rochester, Minn., attending an American College of Surgeons Advanced Education Institute (ACS/AEI) course on simulations. At the end of that course, we participants were challenged by a manikin in extremis. Everyone there was an expert, had an advanced degree, had some experience in simulation, or were surgeons interested in simulation. I found that, even though this was a simulation and the patient was only a pretend human being, my adrenal cortex performed almost as if I were doing a real resuscitation. Previous training I’d had on teamwork, crew resource management, and ACLS all kicked in, and we got it done. But interestingly, we weren’t perfect. We debriefed and found that, even at our level of experience and training, a simple simulation could be very instructive. Seeing/doing is believing.

High-tech skills in high-risk occupations are well served by simulation training. Much of the airline piloting training is done by simulation. It works well for aviation, nuclear reactors, high voltage line work, and medicine. Most of these disciplines have embraced simulation as an essential part of training. Simulation is part of many surgical training programs, but it has other uses.

When was the last time you practiced a trauma resuscitation, an ultrasound fine-needle biopsy, laparoscopic maneuvers, or an unusual technique that you seldom perform, but when needed, must be pulled off very well? Most of us taking this simulation course agreed that time, money, and ego may get in the way of maintaining those skills for those rare instances when they are needed. Surgeons might want to consider simulation to keep some of our rarely used skills from getting rusty.

If you’re going to make a costly error, I would very much like you to do it on a piece of plastic, not on a patient. There are no consequences for messing up a procedure on a manikin and this kind of practice might teach you something critical. Practicing reduces stress and improves the performance of those placed on the spot by real-life events. Do you think Captain “Sully” Sullenberger could have landed that airliner in the Hudson River safely if he hadn’t practiced with countless mind-numbingly complex simulations? Sure, luck plays a part, and innate ability plays a part. But skill, knowledge, and practice are your best bet when all the eyes in the room swivel to you in a moment of crisis.

You may think that simulators have to cost $100,000 and be completely realistic to do the job. That’s not true. A banana, orange, or stick of butter can be fabulous sims for a med student. Felt and cardboard can make a realistic cricothyroidotomy model.

Surgeons all over the country are using simulation training to learn how to be better without getting real blood on their shoes. If you haven’t participated in a training simulation recently, I double-dog dare you to try it and tell me you found it without merit. The ACS Surgical Simulation Summit is being held in March 2019 in Chicago. You might want to check that out.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Salina, and Coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

She had fallen on a garden implement, lacerating her superficial femoral artery. She used her cell phone to call 911. Thanks to an alert EMS crew and the Stop the Bleed training they recently received, a tourniquet was placed without delay. She got to our trauma bay in about 15 minutes after the tourniquet was applied. Although the patient made it abundantly clear that she was in pain, she was stable with moderate tachycardia and a good blood pressure.

Our trauma team leaped into action. The leader took report from the EMS while two nurses and a second surgeon assessed the patient, got her clothes cut off, and applied monitors. A third nurse got a second IV going. Primary survey was done in less than 90 seconds. The patient then underwent a focused exam including a log roll for back injuries.

The leg wound was still oozing a bit, so a second tourniquet was called for and pressure applied until it could be acquired. The patient was given 5 mg of morphine sulfate, which calmed her down a bit. Labs and x-rays were done quickly. The nursing staff suggested a tetanus booster, and the second surgeon who had gotten a basic past medical history suggested vancomycin since the patient said she was allergic to penicillin. Fifteen minutes after she hit the trauma bay, she was on her way to the OR for exploration, debridement, and vascular repair of her injury.

This was all done by four M2 medical students and five N4 nursing students, none of whom had had previous experience with this type of trauma patient

The students were managing this trauma situation in the simulation center of their medical school with four staff watching. This was their second run through for the afternoon. At debriefing, they compared their work on the first trauma of the day (a stab wound to the right chest) to their second attempt. They were satisfied with their efforts and so were we, the faculty who ran the simulation. Comparing their response to those I’ve seen in real life, I’d say these students understood their roles and responsibilities as well as the sort of thrown-together teams I’ve seen at places where trauma is not the main focus. While these young men and women are in the early stage of training and not ready for a real-world trauma emergency, they have gained knowledge about this kind of situation that I didn’t see until I was in residency and beyond. The times they are a-changing.

A couple of days later I was in Rochester, Minn., attending an American College of Surgeons Advanced Education Institute (ACS/AEI) course on simulations. At the end of that course, we participants were challenged by a manikin in extremis. Everyone there was an expert, had an advanced degree, had some experience in simulation, or were surgeons interested in simulation. I found that, even though this was a simulation and the patient was only a pretend human being, my adrenal cortex performed almost as if I were doing a real resuscitation. Previous training I’d had on teamwork, crew resource management, and ACLS all kicked in, and we got it done. But interestingly, we weren’t perfect. We debriefed and found that, even at our level of experience and training, a simple simulation could be very instructive. Seeing/doing is believing.

High-tech skills in high-risk occupations are well served by simulation training. Much of the airline piloting training is done by simulation. It works well for aviation, nuclear reactors, high voltage line work, and medicine. Most of these disciplines have embraced simulation as an essential part of training. Simulation is part of many surgical training programs, but it has other uses.

When was the last time you practiced a trauma resuscitation, an ultrasound fine-needle biopsy, laparoscopic maneuvers, or an unusual technique that you seldom perform, but when needed, must be pulled off very well? Most of us taking this simulation course agreed that time, money, and ego may get in the way of maintaining those skills for those rare instances when they are needed. Surgeons might want to consider simulation to keep some of our rarely used skills from getting rusty.

If you’re going to make a costly error, I would very much like you to do it on a piece of plastic, not on a patient. There are no consequences for messing up a procedure on a manikin and this kind of practice might teach you something critical. Practicing reduces stress and improves the performance of those placed on the spot by real-life events. Do you think Captain “Sully” Sullenberger could have landed that airliner in the Hudson River safely if he hadn’t practiced with countless mind-numbingly complex simulations? Sure, luck plays a part, and innate ability plays a part. But skill, knowledge, and practice are your best bet when all the eyes in the room swivel to you in a moment of crisis.

You may think that simulators have to cost $100,000 and be completely realistic to do the job. That’s not true. A banana, orange, or stick of butter can be fabulous sims for a med student. Felt and cardboard can make a realistic cricothyroidotomy model.

Surgeons all over the country are using simulation training to learn how to be better without getting real blood on their shoes. If you haven’t participated in a training simulation recently, I double-dog dare you to try it and tell me you found it without merit. The ACS Surgical Simulation Summit is being held in March 2019 in Chicago. You might want to check that out.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Salina, and Coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Communication and consent

We knew that the case would be a difficult one. The patient was a man in his mid-40s who had several serious chronic conditions and was on high-dose steroids. He had been operated on 10 days earlier by one of my partners for a bowel obstruction and had required a resection of a small portion of the terminal ileum. Unfortunately, on the day after surgery, it became obvious that the patient needed a reexploration for bleeding. He had developed clear evidence of a significant anastomotic leak and had to be taken emergently back to the operating room.

His condition had been worsening during the day. We had booked the case in the OR but had been put off by a trauma emergency and a neurosurgical emergency. During the 3 hours of waiting to take him to the OR, the patient’s sister and mother came to the hospital and were now waiting with him in the preop area. I was on my way up to see him when my resident called. Despite the patient having signed an operative consent form a few hours earlier when we booked the case, he was now “declining” an operation. I was surprised. This man had undergone several operations in the last few years and two in the last 2 weeks. I arrived to find the patient stating that he did not want surgery. Lying in bed, he was adamant that he should not have surgery. The surgical resident who had spoken with the patient several times over the last few hours was also surprised. The patient’s family members were yelling that, of course, he wanted surgery and why would he change his mind.

This is a difficult situation since one of the central tenets of the ethical practice of surgery is to allow patients to make decisions about their own care. The right to make autonomous choices even extends to circumstances in which patients make what we might consider “bad” decisions. As long as the patient has the capacity to make an autonomous choice, he or she should have that choice respected.

This patient, who just a few hours ago had agreed to surgery, now seemed to have changed his mind. Although it can be frustrating, we do allow patients to change their minds. On the one hand, this was a straightforward case. The patient was refusing a potentially life-saving operation. Such a situation is never pleasant for a surgeon, but as long as the patient understands the risks, we respect such choices.

However, my resident made an astute observation. She pointed out that, when asked why he now did not want surgery, he replied that “this is all a movie – it’s not really happening.” The patient appeared to be oriented to person and place, but nevertheless, his reasoning seemed to have been altered. It appeared that this patient was no longer making sense because his underlying medical condition had deteriorated. We considered whether he was becoming septic and that this change in medical condition had rendered him unable to make an informed decision. My resident, who had discussed the operation with the patient several times, stated that the patient’s decision making seemed very different than even an hour ago. His family members agreed, stating that, up until a few minutes before, he was in favor of surgery. They pleaded with us to just take him into the operating room.

We considered our options. We could delay surgery and consult psychiatry to ask them to assess his competency. However, on a weekend night, this would likely take several hours. We considered the option of waiting in the preop area for the patient’s medical condition to further worsen. If he became overtly septic and lost consciousness, then we could readily turn to the family members – his surrogate decision makers – and ask them to consent to the procedure. Although this “by the book” approach might take away any worry that we were overriding an autonomous patient’s choice, we knew that it would unnecessarily expose him to greater operative risks. This option was not in his best interest and therefore not much of an option.

Ultimately, the surgical resident, the attending anesthesiologist, the family, and I decided that his decision to not have surgery at this moment was not consistent with his prior decisions, and he could provide no reason for changing his mind. We brought the patient into the operating room and explored him. He did have a large anastomotic leak with a large volume of enteric contents in the peritoneal cavity. He survived the operation and, not unexpectedly, required a long postoperative stay in the hospital. Once he was a few days out, I inquired about whether he was glad that he had surgery. He was quick to state his confidence that it had been the right choice for him. He did not even remember having ever refused the surgery.

Although this case raised many concerns for all of us involved in the patient’s care, one overriding lesson that came through to me. Informed consent should not be viewed as a solitary event, but a conversation. This patient had expressed his desire to have surgery multiple times to my surgical resident and to his family. Even though we should never take the position that patients cannot change their minds, we should carefully question those choices that are inconsistent with the prior discussions that have been undertaken. Good communication skills – including listening to the patient, understanding the patient’s reasoning, and reflecting on the entire conversation – are essential in obtaining informed consent.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

We knew that the case would be a difficult one. The patient was a man in his mid-40s who had several serious chronic conditions and was on high-dose steroids. He had been operated on 10 days earlier by one of my partners for a bowel obstruction and had required a resection of a small portion of the terminal ileum. Unfortunately, on the day after surgery, it became obvious that the patient needed a reexploration for bleeding. He had developed clear evidence of a significant anastomotic leak and had to be taken emergently back to the operating room.

His condition had been worsening during the day. We had booked the case in the OR but had been put off by a trauma emergency and a neurosurgical emergency. During the 3 hours of waiting to take him to the OR, the patient’s sister and mother came to the hospital and were now waiting with him in the preop area. I was on my way up to see him when my resident called. Despite the patient having signed an operative consent form a few hours earlier when we booked the case, he was now “declining” an operation. I was surprised. This man had undergone several operations in the last few years and two in the last 2 weeks. I arrived to find the patient stating that he did not want surgery. Lying in bed, he was adamant that he should not have surgery. The surgical resident who had spoken with the patient several times over the last few hours was also surprised. The patient’s family members were yelling that, of course, he wanted surgery and why would he change his mind.

This is a difficult situation since one of the central tenets of the ethical practice of surgery is to allow patients to make decisions about their own care. The right to make autonomous choices even extends to circumstances in which patients make what we might consider “bad” decisions. As long as the patient has the capacity to make an autonomous choice, he or she should have that choice respected.

This patient, who just a few hours ago had agreed to surgery, now seemed to have changed his mind. Although it can be frustrating, we do allow patients to change their minds. On the one hand, this was a straightforward case. The patient was refusing a potentially life-saving operation. Such a situation is never pleasant for a surgeon, but as long as the patient understands the risks, we respect such choices.

However, my resident made an astute observation. She pointed out that, when asked why he now did not want surgery, he replied that “this is all a movie – it’s not really happening.” The patient appeared to be oriented to person and place, but nevertheless, his reasoning seemed to have been altered. It appeared that this patient was no longer making sense because his underlying medical condition had deteriorated. We considered whether he was becoming septic and that this change in medical condition had rendered him unable to make an informed decision. My resident, who had discussed the operation with the patient several times, stated that the patient’s decision making seemed very different than even an hour ago. His family members agreed, stating that, up until a few minutes before, he was in favor of surgery. They pleaded with us to just take him into the operating room.

We considered our options. We could delay surgery and consult psychiatry to ask them to assess his competency. However, on a weekend night, this would likely take several hours. We considered the option of waiting in the preop area for the patient’s medical condition to further worsen. If he became overtly septic and lost consciousness, then we could readily turn to the family members – his surrogate decision makers – and ask them to consent to the procedure. Although this “by the book” approach might take away any worry that we were overriding an autonomous patient’s choice, we knew that it would unnecessarily expose him to greater operative risks. This option was not in his best interest and therefore not much of an option.

Ultimately, the surgical resident, the attending anesthesiologist, the family, and I decided that his decision to not have surgery at this moment was not consistent with his prior decisions, and he could provide no reason for changing his mind. We brought the patient into the operating room and explored him. He did have a large anastomotic leak with a large volume of enteric contents in the peritoneal cavity. He survived the operation and, not unexpectedly, required a long postoperative stay in the hospital. Once he was a few days out, I inquired about whether he was glad that he had surgery. He was quick to state his confidence that it had been the right choice for him. He did not even remember having ever refused the surgery.

Although this case raised many concerns for all of us involved in the patient’s care, one overriding lesson that came through to me. Informed consent should not be viewed as a solitary event, but a conversation. This patient had expressed his desire to have surgery multiple times to my surgical resident and to his family. Even though we should never take the position that patients cannot change their minds, we should carefully question those choices that are inconsistent with the prior discussions that have been undertaken. Good communication skills – including listening to the patient, understanding the patient’s reasoning, and reflecting on the entire conversation – are essential in obtaining informed consent.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

We knew that the case would be a difficult one. The patient was a man in his mid-40s who had several serious chronic conditions and was on high-dose steroids. He had been operated on 10 days earlier by one of my partners for a bowel obstruction and had required a resection of a small portion of the terminal ileum. Unfortunately, on the day after surgery, it became obvious that the patient needed a reexploration for bleeding. He had developed clear evidence of a significant anastomotic leak and had to be taken emergently back to the operating room.

His condition had been worsening during the day. We had booked the case in the OR but had been put off by a trauma emergency and a neurosurgical emergency. During the 3 hours of waiting to take him to the OR, the patient’s sister and mother came to the hospital and were now waiting with him in the preop area. I was on my way up to see him when my resident called. Despite the patient having signed an operative consent form a few hours earlier when we booked the case, he was now “declining” an operation. I was surprised. This man had undergone several operations in the last few years and two in the last 2 weeks. I arrived to find the patient stating that he did not want surgery. Lying in bed, he was adamant that he should not have surgery. The surgical resident who had spoken with the patient several times over the last few hours was also surprised. The patient’s family members were yelling that, of course, he wanted surgery and why would he change his mind.

This is a difficult situation since one of the central tenets of the ethical practice of surgery is to allow patients to make decisions about their own care. The right to make autonomous choices even extends to circumstances in which patients make what we might consider “bad” decisions. As long as the patient has the capacity to make an autonomous choice, he or she should have that choice respected.

This patient, who just a few hours ago had agreed to surgery, now seemed to have changed his mind. Although it can be frustrating, we do allow patients to change their minds. On the one hand, this was a straightforward case. The patient was refusing a potentially life-saving operation. Such a situation is never pleasant for a surgeon, but as long as the patient understands the risks, we respect such choices.

However, my resident made an astute observation. She pointed out that, when asked why he now did not want surgery, he replied that “this is all a movie – it’s not really happening.” The patient appeared to be oriented to person and place, but nevertheless, his reasoning seemed to have been altered. It appeared that this patient was no longer making sense because his underlying medical condition had deteriorated. We considered whether he was becoming septic and that this change in medical condition had rendered him unable to make an informed decision. My resident, who had discussed the operation with the patient several times, stated that the patient’s decision making seemed very different than even an hour ago. His family members agreed, stating that, up until a few minutes before, he was in favor of surgery. They pleaded with us to just take him into the operating room.

We considered our options. We could delay surgery and consult psychiatry to ask them to assess his competency. However, on a weekend night, this would likely take several hours. We considered the option of waiting in the preop area for the patient’s medical condition to further worsen. If he became overtly septic and lost consciousness, then we could readily turn to the family members – his surrogate decision makers – and ask them to consent to the procedure. Although this “by the book” approach might take away any worry that we were overriding an autonomous patient’s choice, we knew that it would unnecessarily expose him to greater operative risks. This option was not in his best interest and therefore not much of an option.

Ultimately, the surgical resident, the attending anesthesiologist, the family, and I decided that his decision to not have surgery at this moment was not consistent with his prior decisions, and he could provide no reason for changing his mind. We brought the patient into the operating room and explored him. He did have a large anastomotic leak with a large volume of enteric contents in the peritoneal cavity. He survived the operation and, not unexpectedly, required a long postoperative stay in the hospital. Once he was a few days out, I inquired about whether he was glad that he had surgery. He was quick to state his confidence that it had been the right choice for him. He did not even remember having ever refused the surgery.

Although this case raised many concerns for all of us involved in the patient’s care, one overriding lesson that came through to me. Informed consent should not be viewed as a solitary event, but a conversation. This patient had expressed his desire to have surgery multiple times to my surgical resident and to his family. Even though we should never take the position that patients cannot change their minds, we should carefully question those choices that are inconsistent with the prior discussions that have been undertaken. Good communication skills – including listening to the patient, understanding the patient’s reasoning, and reflecting on the entire conversation – are essential in obtaining informed consent.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

U.S. vs. Europe: Costs of cardiac implant devices compared

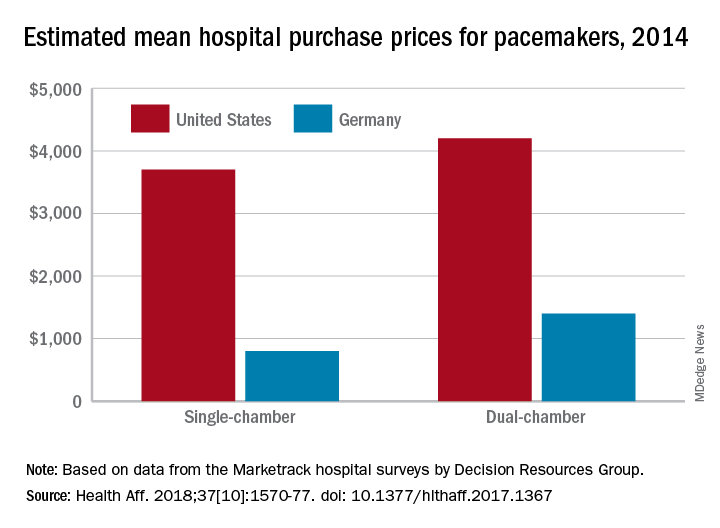

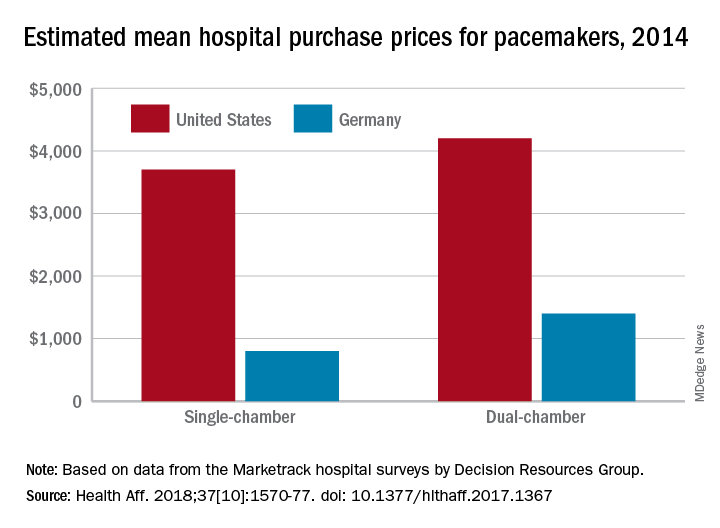

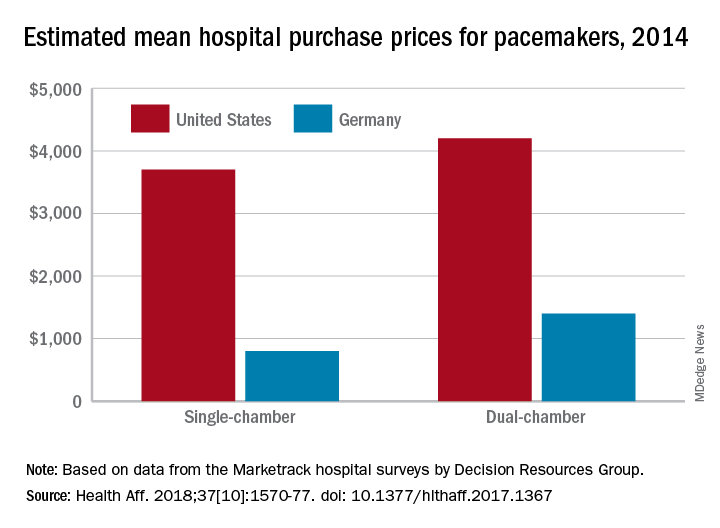

Prices that hospitals pay for cardiac implant devices are two to six times higher in the United States than in Europe, according to analysis of a large hospital panel survey.

U.S. hospitals had an estimated mean cost of $670 for a bare-metal stent in 2014, compared with $120 in Germany, and the mean costs for dual-chamber pacemakers that year were $4,200 in the United States and $1,400 in Germany, which had lower costs for cardiac devices than the other three European countries – United Kingdom, France, and Italy – included in the study, Martin Wenzl, MSc, and Elias Mossialos, MD, PhD, reported in Health Affairs.

France generally had the highest costs among the European countries, with Italy next and then the United Kingdom. The estimated cost of bare-metal stents was actually higher for French hospitals ($750) than for those in the United States, and Italy had mean prices similar to the United Sates for dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The prices of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization devices with defibrillating function were the other exceptions, with the United Kingdom similar to or higher than the United States, said Mr. Wenzl and Dr. Mossialos, both of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The analysis of data from Decision Resources Group’s Marketrack hospital surveys also showed significant variation between the hospitals in each country, with the exception of France, where payments are based on the specific device rather than the procedure and the system “creates weak incentives for hospitals to negotiate lower prices,” they said. In most of the device categories, “variation between hospitals in each country was similar to variation between countries,” they wrote, adding that prices in general “were only weakly correlated with volumes purchased by hospitals.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. The investigators did not disclose any possible conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wenzi M, Mossialos E. Health Aff. 2018;37[10]:1570-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1367.

Prices that hospitals pay for cardiac implant devices are two to six times higher in the United States than in Europe, according to analysis of a large hospital panel survey.

U.S. hospitals had an estimated mean cost of $670 for a bare-metal stent in 2014, compared with $120 in Germany, and the mean costs for dual-chamber pacemakers that year were $4,200 in the United States and $1,400 in Germany, which had lower costs for cardiac devices than the other three European countries – United Kingdom, France, and Italy – included in the study, Martin Wenzl, MSc, and Elias Mossialos, MD, PhD, reported in Health Affairs.

France generally had the highest costs among the European countries, with Italy next and then the United Kingdom. The estimated cost of bare-metal stents was actually higher for French hospitals ($750) than for those in the United States, and Italy had mean prices similar to the United Sates for dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The prices of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization devices with defibrillating function were the other exceptions, with the United Kingdom similar to or higher than the United States, said Mr. Wenzl and Dr. Mossialos, both of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The analysis of data from Decision Resources Group’s Marketrack hospital surveys also showed significant variation between the hospitals in each country, with the exception of France, where payments are based on the specific device rather than the procedure and the system “creates weak incentives for hospitals to negotiate lower prices,” they said. In most of the device categories, “variation between hospitals in each country was similar to variation between countries,” they wrote, adding that prices in general “were only weakly correlated with volumes purchased by hospitals.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. The investigators did not disclose any possible conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wenzi M, Mossialos E. Health Aff. 2018;37[10]:1570-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1367.

Prices that hospitals pay for cardiac implant devices are two to six times higher in the United States than in Europe, according to analysis of a large hospital panel survey.

U.S. hospitals had an estimated mean cost of $670 for a bare-metal stent in 2014, compared with $120 in Germany, and the mean costs for dual-chamber pacemakers that year were $4,200 in the United States and $1,400 in Germany, which had lower costs for cardiac devices than the other three European countries – United Kingdom, France, and Italy – included in the study, Martin Wenzl, MSc, and Elias Mossialos, MD, PhD, reported in Health Affairs.

France generally had the highest costs among the European countries, with Italy next and then the United Kingdom. The estimated cost of bare-metal stents was actually higher for French hospitals ($750) than for those in the United States, and Italy had mean prices similar to the United Sates for dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The prices of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization devices with defibrillating function were the other exceptions, with the United Kingdom similar to or higher than the United States, said Mr. Wenzl and Dr. Mossialos, both of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The analysis of data from Decision Resources Group’s Marketrack hospital surveys also showed significant variation between the hospitals in each country, with the exception of France, where payments are based on the specific device rather than the procedure and the system “creates weak incentives for hospitals to negotiate lower prices,” they said. In most of the device categories, “variation between hospitals in each country was similar to variation between countries,” they wrote, adding that prices in general “were only weakly correlated with volumes purchased by hospitals.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. The investigators did not disclose any possible conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wenzi M, Mossialos E. Health Aff. 2018;37[10]:1570-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1367.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Drug-coated balloons shown noninferior to DES in thin coronaries

MUNICH – for preventing the clinical consequences of restenosis during 12 months following coronary intervention, according to results from a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Drug-coated balloons are already used to treat in-stent coronary restenosis. The findings of the current study establish the tested DCB as noninferior to a DES for treating coronary stenoses in narrow arteries less than 3 mm in diameter, Raban V. Jeger, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. The DCB approach avoids placing a metal stent in a narrow coronary and thus has no long-term risk for in-stent thrombosis, said Dr. Jeger, a professor of cardiology at Basel (Switzerland) University Hospital. Dr. Jeger acknowledged that the tested DCB is more expensive than the second-generation DES used as the comparator in most of the control patients, “but I think the benefit to patients is worth” the added cost, he said when discussing his report.

The BASKET-SMALL 2 (NCT01574534) study enrolled 758 patients at 14 centers in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. The trial limited enrollment to patients who were scheduled to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention for stenosis in a coronary artery that was at least 2.0 mm and less than 3.0 mm in diameter and had first undergone successful predilatation without any flow-limiting dissections or residual stenosis, a step in the DCB procedure that adds to the procedure’s cost.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study randomized patients to treatment with either a balloon coated with paclitaxel/iopromide (SeQuent Please) or a DES. The first quarter of patients randomized into the DES arm received a first-generation, paclitaxel-eluting DES (Taxus Element); the remaining patients in the comparator arm received a second-generation everolimus-eluting DES (Xience). The DCB tested is not approved for U.S. marketing.