User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Delay of NSCLC surgery can lead to worse prognosis

SAN DIEGO – Delaying

“There is significant upstaging with time from completion of clinical staging to surgical resection, with a 4% increase of upstaging per week for the overall study population,” said study coauthor Harmik J. Soukiasian, MD, FACS, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, in an interview. “Upstaging impacts lung cancer prognosis as more advanced stages portend to a poorer prognosis.”

An estimated 80%-85% of lung cancer patients have NSCLC, according to the American Cancer Society, and Dr. Soukiasian said surgery offers a chance at a cure for those diagnosed at stage I.

“National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) Guidelines recommend surgery within 8 weeks of completed clinical staging for NSCLC to limit cancer progression or upstaging,” Dr. Soukiasian said. “Although these guidelines are well established and widely adopted, our study performs a more granular analysis, studying time as a predictor of upstaging for those patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC.”

For the new study, Dr. Soukiasian and colleagues tracked 52,406 patients in a cancer database who had stage I NSCLC but had not undergone preoperative chemotherapy. The researchers tracked their clinical stages for up to 12 weeks from initial staging.

Researchers found that, while staging levels rose with each successive week, just 25% of patients underwent surgery by 1 week, and only 79% had surgery in accordance with NSCLC guidelines by week 8. At 12 weeks, 9% had still not undergone surgery.

Upstaging was common: 22% at 1 week, 32% after 8 weeks, and 33% after 12 weeks.

“We demonstrate that patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC benefit from surgery sooner than the 8-week window recommended by the NCCN guidelines,” Dr. Soukiasian said. “Exclusive of the rate of progression and in addition to time to surgery, our study also demonstrated academic centers, higher lymph node yield during surgery, and left-sided tumors to be independent predictors of upstaging.”

The study design doesn’t provide insight into why surgery is often delayed. However, “we can theorize factors associated with delays to surgery may be due to patient factors (personal scheduling, availability of support systems, etc.), delays in follow up, operating room availability or scheduling, and issues with insurance approval,” Dr. Soukiasian said.

In his presentation, Dr. Soukiasian emphasized the role of the mediastinum. “Given the clinical impact of stage III disease, we analyzed upstaging rates of stage I NSCLC to stage IIIA and revealed a 1.3% increase per week of upstaging specifically to stage IIIA. Additionally, almost 5% of patients initially diagnosed with stage I NSCLC upstaged to IIIA disease. The significant rate of upstaging to IIIA disease makes the case for more accurate and aggressive mediastinal staging prior to surgical resection.”

No disclosures and no study funding are reported.

SOURCE: Soukiasian HJ et al. AATS 2018, Abstract 67.

SAN DIEGO – Delaying

“There is significant upstaging with time from completion of clinical staging to surgical resection, with a 4% increase of upstaging per week for the overall study population,” said study coauthor Harmik J. Soukiasian, MD, FACS, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, in an interview. “Upstaging impacts lung cancer prognosis as more advanced stages portend to a poorer prognosis.”

An estimated 80%-85% of lung cancer patients have NSCLC, according to the American Cancer Society, and Dr. Soukiasian said surgery offers a chance at a cure for those diagnosed at stage I.

“National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) Guidelines recommend surgery within 8 weeks of completed clinical staging for NSCLC to limit cancer progression or upstaging,” Dr. Soukiasian said. “Although these guidelines are well established and widely adopted, our study performs a more granular analysis, studying time as a predictor of upstaging for those patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC.”

For the new study, Dr. Soukiasian and colleagues tracked 52,406 patients in a cancer database who had stage I NSCLC but had not undergone preoperative chemotherapy. The researchers tracked their clinical stages for up to 12 weeks from initial staging.

Researchers found that, while staging levels rose with each successive week, just 25% of patients underwent surgery by 1 week, and only 79% had surgery in accordance with NSCLC guidelines by week 8. At 12 weeks, 9% had still not undergone surgery.

Upstaging was common: 22% at 1 week, 32% after 8 weeks, and 33% after 12 weeks.

“We demonstrate that patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC benefit from surgery sooner than the 8-week window recommended by the NCCN guidelines,” Dr. Soukiasian said. “Exclusive of the rate of progression and in addition to time to surgery, our study also demonstrated academic centers, higher lymph node yield during surgery, and left-sided tumors to be independent predictors of upstaging.”

The study design doesn’t provide insight into why surgery is often delayed. However, “we can theorize factors associated with delays to surgery may be due to patient factors (personal scheduling, availability of support systems, etc.), delays in follow up, operating room availability or scheduling, and issues with insurance approval,” Dr. Soukiasian said.

In his presentation, Dr. Soukiasian emphasized the role of the mediastinum. “Given the clinical impact of stage III disease, we analyzed upstaging rates of stage I NSCLC to stage IIIA and revealed a 1.3% increase per week of upstaging specifically to stage IIIA. Additionally, almost 5% of patients initially diagnosed with stage I NSCLC upstaged to IIIA disease. The significant rate of upstaging to IIIA disease makes the case for more accurate and aggressive mediastinal staging prior to surgical resection.”

No disclosures and no study funding are reported.

SOURCE: Soukiasian HJ et al. AATS 2018, Abstract 67.

SAN DIEGO – Delaying

“There is significant upstaging with time from completion of clinical staging to surgical resection, with a 4% increase of upstaging per week for the overall study population,” said study coauthor Harmik J. Soukiasian, MD, FACS, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, in an interview. “Upstaging impacts lung cancer prognosis as more advanced stages portend to a poorer prognosis.”

An estimated 80%-85% of lung cancer patients have NSCLC, according to the American Cancer Society, and Dr. Soukiasian said surgery offers a chance at a cure for those diagnosed at stage I.

“National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) Guidelines recommend surgery within 8 weeks of completed clinical staging for NSCLC to limit cancer progression or upstaging,” Dr. Soukiasian said. “Although these guidelines are well established and widely adopted, our study performs a more granular analysis, studying time as a predictor of upstaging for those patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC.”

For the new study, Dr. Soukiasian and colleagues tracked 52,406 patients in a cancer database who had stage I NSCLC but had not undergone preoperative chemotherapy. The researchers tracked their clinical stages for up to 12 weeks from initial staging.

Researchers found that, while staging levels rose with each successive week, just 25% of patients underwent surgery by 1 week, and only 79% had surgery in accordance with NSCLC guidelines by week 8. At 12 weeks, 9% had still not undergone surgery.

Upstaging was common: 22% at 1 week, 32% after 8 weeks, and 33% after 12 weeks.

“We demonstrate that patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC benefit from surgery sooner than the 8-week window recommended by the NCCN guidelines,” Dr. Soukiasian said. “Exclusive of the rate of progression and in addition to time to surgery, our study also demonstrated academic centers, higher lymph node yield during surgery, and left-sided tumors to be independent predictors of upstaging.”

The study design doesn’t provide insight into why surgery is often delayed. However, “we can theorize factors associated with delays to surgery may be due to patient factors (personal scheduling, availability of support systems, etc.), delays in follow up, operating room availability or scheduling, and issues with insurance approval,” Dr. Soukiasian said.

In his presentation, Dr. Soukiasian emphasized the role of the mediastinum. “Given the clinical impact of stage III disease, we analyzed upstaging rates of stage I NSCLC to stage IIIA and revealed a 1.3% increase per week of upstaging specifically to stage IIIA. Additionally, almost 5% of patients initially diagnosed with stage I NSCLC upstaged to IIIA disease. The significant rate of upstaging to IIIA disease makes the case for more accurate and aggressive mediastinal staging prior to surgical resection.”

No disclosures and no study funding are reported.

SOURCE: Soukiasian HJ et al. AATS 2018, Abstract 67.

AT THE AATS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Clinical staging levels worsen in each successive surgery-free week after initial staging in certain NSCLC patients.

Major finding: There was a 1.3% increase per week of upstaging to stage IIIA.

Study details: Analysis of 52,406 patients with stage I NSCLC who were tracked for up to 12 weeks.

Disclosures: No disclosures and no funding were reported.

Source: Soukiasian HJ et al. AATS 2018, Abstract 67.

White House targets CHIP, CMMI for budget cuts

The package also includes an $800 million cut to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), a policy incubator that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses to test innovative payment approaches.

These funds were a one-time, additional appropriation “to reimburse states for eligible CHIP expenses.” According to the rescission request, the authority “to obligate these funds to states expired on Sept. 30, 2017, and the remaining funding is no longer needed.”

A second request would rescind nearly $1.9 billion from the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, which provides payments to states that experience shortfalls from higher-than-expected enrollment. The White House notes that there were $2.4 billion available as of March 23, 2018, and that CMS “does not expect that any state would require a contingency fund payment in fiscal year 2018; therefore, this funding is not needed.”

If enacted, these rescissions “would have no programmatic impact,” according to the White House.

A broad coalition of physicians’ organizations and other advocates protested the proposed cuts in a May 9 letter to Congress.

“While White House officials insist that the CHIP cuts would not harm access to care for children and families, that is simply not the case,” according to the letter signed by more than 500 organizations. “Our nation is facing an increasing number of natural disasters ... [and] each catastrophe leaves families more vulnerable and more likely to qualify for CHIP. In addition to natural disasters, the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund provides states needed protection and security should their CHIP enrollment suddenly spike due to an economic recession or a public health crisis.”

Regarding the CMMI cut, the $800,000 would be rescinded from funds appropriated through fiscal year 2019. The White House notes that $3.5 billion was available as of Oct. 1, 2017.

The rescission represents funds that “are in excess of amounts needed to carry out the Innovation Center’s planned activities in fiscal 2018 and fiscal 2019, and the Innovation Center will receive new mandatory appropriation in fiscal 2020. Enacting this rescission would allow the Innovation Center to continue its current activity, initiate new activity, and continue to pay for its administrative costs,” according to the rescission request.

CMMI “is our best hope to innovate & achieve better health outcomes at lower costs,” Patrick Conway, MD, former deputy administrator and chief medical officer at CMS said in a May 8 tweet. “Cutting $800M or any amount would be a bad decision. CMS spends over $1 trillion per year; over $100M/hour. CMMI is key to better system.”

American Academy of Family Physicians President Michael Munger, MD, agreed.

“We’re also concerned about the $800 million rescission in funding for the CMS Innovation Center,” he said. “This initiative has been at the forefront of innovative demonstrations that can pave the way for a health care system that improves the quality of care and cuts health care spending.”

Congress has 45 days to act on the White House’s rescission proposal. If it takes no action, the proposal expires and the funds cannot be targeted by the same mechanism in the future. If Congress addresses the rescission request, it would need just a simple majority to pass each chamber.

Despite slashing more than $15 billion from the budget, the White House notes that the rescission request would reduce spending by only $3 billion.

The package also includes an $800 million cut to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), a policy incubator that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses to test innovative payment approaches.

These funds were a one-time, additional appropriation “to reimburse states for eligible CHIP expenses.” According to the rescission request, the authority “to obligate these funds to states expired on Sept. 30, 2017, and the remaining funding is no longer needed.”

A second request would rescind nearly $1.9 billion from the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, which provides payments to states that experience shortfalls from higher-than-expected enrollment. The White House notes that there were $2.4 billion available as of March 23, 2018, and that CMS “does not expect that any state would require a contingency fund payment in fiscal year 2018; therefore, this funding is not needed.”

If enacted, these rescissions “would have no programmatic impact,” according to the White House.

A broad coalition of physicians’ organizations and other advocates protested the proposed cuts in a May 9 letter to Congress.

“While White House officials insist that the CHIP cuts would not harm access to care for children and families, that is simply not the case,” according to the letter signed by more than 500 organizations. “Our nation is facing an increasing number of natural disasters ... [and] each catastrophe leaves families more vulnerable and more likely to qualify for CHIP. In addition to natural disasters, the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund provides states needed protection and security should their CHIP enrollment suddenly spike due to an economic recession or a public health crisis.”

Regarding the CMMI cut, the $800,000 would be rescinded from funds appropriated through fiscal year 2019. The White House notes that $3.5 billion was available as of Oct. 1, 2017.

The rescission represents funds that “are in excess of amounts needed to carry out the Innovation Center’s planned activities in fiscal 2018 and fiscal 2019, and the Innovation Center will receive new mandatory appropriation in fiscal 2020. Enacting this rescission would allow the Innovation Center to continue its current activity, initiate new activity, and continue to pay for its administrative costs,” according to the rescission request.

CMMI “is our best hope to innovate & achieve better health outcomes at lower costs,” Patrick Conway, MD, former deputy administrator and chief medical officer at CMS said in a May 8 tweet. “Cutting $800M or any amount would be a bad decision. CMS spends over $1 trillion per year; over $100M/hour. CMMI is key to better system.”

American Academy of Family Physicians President Michael Munger, MD, agreed.

“We’re also concerned about the $800 million rescission in funding for the CMS Innovation Center,” he said. “This initiative has been at the forefront of innovative demonstrations that can pave the way for a health care system that improves the quality of care and cuts health care spending.”

Congress has 45 days to act on the White House’s rescission proposal. If it takes no action, the proposal expires and the funds cannot be targeted by the same mechanism in the future. If Congress addresses the rescission request, it would need just a simple majority to pass each chamber.

Despite slashing more than $15 billion from the budget, the White House notes that the rescission request would reduce spending by only $3 billion.

The package also includes an $800 million cut to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), a policy incubator that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses to test innovative payment approaches.

These funds were a one-time, additional appropriation “to reimburse states for eligible CHIP expenses.” According to the rescission request, the authority “to obligate these funds to states expired on Sept. 30, 2017, and the remaining funding is no longer needed.”

A second request would rescind nearly $1.9 billion from the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, which provides payments to states that experience shortfalls from higher-than-expected enrollment. The White House notes that there were $2.4 billion available as of March 23, 2018, and that CMS “does not expect that any state would require a contingency fund payment in fiscal year 2018; therefore, this funding is not needed.”

If enacted, these rescissions “would have no programmatic impact,” according to the White House.

A broad coalition of physicians’ organizations and other advocates protested the proposed cuts in a May 9 letter to Congress.

“While White House officials insist that the CHIP cuts would not harm access to care for children and families, that is simply not the case,” according to the letter signed by more than 500 organizations. “Our nation is facing an increasing number of natural disasters ... [and] each catastrophe leaves families more vulnerable and more likely to qualify for CHIP. In addition to natural disasters, the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund provides states needed protection and security should their CHIP enrollment suddenly spike due to an economic recession or a public health crisis.”

Regarding the CMMI cut, the $800,000 would be rescinded from funds appropriated through fiscal year 2019. The White House notes that $3.5 billion was available as of Oct. 1, 2017.

The rescission represents funds that “are in excess of amounts needed to carry out the Innovation Center’s planned activities in fiscal 2018 and fiscal 2019, and the Innovation Center will receive new mandatory appropriation in fiscal 2020. Enacting this rescission would allow the Innovation Center to continue its current activity, initiate new activity, and continue to pay for its administrative costs,” according to the rescission request.

CMMI “is our best hope to innovate & achieve better health outcomes at lower costs,” Patrick Conway, MD, former deputy administrator and chief medical officer at CMS said in a May 8 tweet. “Cutting $800M or any amount would be a bad decision. CMS spends over $1 trillion per year; over $100M/hour. CMMI is key to better system.”

American Academy of Family Physicians President Michael Munger, MD, agreed.

“We’re also concerned about the $800 million rescission in funding for the CMS Innovation Center,” he said. “This initiative has been at the forefront of innovative demonstrations that can pave the way for a health care system that improves the quality of care and cuts health care spending.”

Congress has 45 days to act on the White House’s rescission proposal. If it takes no action, the proposal expires and the funds cannot be targeted by the same mechanism in the future. If Congress addresses the rescission request, it would need just a simple majority to pass each chamber.

Despite slashing more than $15 billion from the budget, the White House notes that the rescission request would reduce spending by only $3 billion.

Figure-of-eight overstitch keeps endoscopic stents in place

SEATTLE – Endoscopic stent migration fell from 41% of stent cases to 15% after surgeons at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, started to secure stents with a single, proximal figure-of-eight overstitch.

Anastomotic leaks are a major and potentially fatal complication of bariatric surgery. Stents are one of the fix options: An expanding tube is rolled down over the wound to take the pressure off and give it time to heal. The stent is removed after the leak closes, which can take a few weeks or longer.

Stents designed specifically for the procedure will likely address the problem in the near future, but for now, the overstitch helps at Lenox Hill. Meanwhile, “it’s important to [realize] that stent migration did not adversely impact [bariatric surgery] failure rates, nor was migration associated with the incidence of revision surgery,” said surgery resident Varun Krishnan, MD.

Dr. Krishnan was the lead investigator on a review of 37 leak cases at Lenox Hill from 2005 to 2017, 17 before overstitch was begun in 2012, and 20 afterwards, with follow-up out to 71 months. The results were presented at the World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS. The senior investigator was Lenox Hill surgeon Julio Teixeira, MD, FACS, associate professor of medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. He reported the first use of stents for bariatric leaks in 2007 (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007 Jan-Feb;3[1]:68-71).

The goal of the review was to address lingering concerns about long-term effects of stents on weight loss and other issues. In the end, “our experience with stenting has been very positive. It’s a very good [option] for treating leaks after bariatric surgery,” Dr. Krishnan said,

The overall success rate was 95%. The 2 failures were both in the sleeve gastrectomy patient group, which made up 43% of the 37 leak cases. The leaks were fixed in one sleeve patient with conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and the other with a stent redo. Both were in the overstitch group.

“We had better success with gastric bypass [patients], probably due to anatomy,” Dr. Krishnan noted. Sleeves leave patients with higher intraluminal pressures, which complicate leak healing.

Stents didn’t have any impact on weight loss. Patients lost a mean of 57% of their excess body weight over an average of 21 months.

Out of 20 patients with available data, 5 were readmitted for oral intolerance, another major concern with endoscopic stents; 3 had their stents removed because of it. None required total parenteral nutrition.

Among 17 patients with available data, 7 (41.7%) had poststent reflux; all of them reported proton-pump inhibitor histories.

Of the 37 total cases, 15 patients (41%) had Roux-en-Y bypasses. The remaining six bypass patients received either duodenal switches or foregut procedures.

Two sleeve and four bypass patients (16%) had revisions. One was the conversion to bypass after stent failure, but the others were for intussusception, strictures, reflux, and other problems that didn’t seem related to stents. About six patients were restented, the one case for stent failure plus five or so for migration.

Patients were an average of about 40 years old, and 70% were women. Average preop body mass index was over 40 kg/m2. The one death in the series was from fungal sepsis a year after stent removal.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Krishnan noted that the distal tip of the stent was placed just after the gastrojejunal anastomosis in bypass cases. Also, bariatric surgeons do the endoscopy at Lenox Hill and place the stents.

The investigators did not report any relevant disclosures, and there was no outside funding.

SEATTLE – Endoscopic stent migration fell from 41% of stent cases to 15% after surgeons at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, started to secure stents with a single, proximal figure-of-eight overstitch.

Anastomotic leaks are a major and potentially fatal complication of bariatric surgery. Stents are one of the fix options: An expanding tube is rolled down over the wound to take the pressure off and give it time to heal. The stent is removed after the leak closes, which can take a few weeks or longer.

Stents designed specifically for the procedure will likely address the problem in the near future, but for now, the overstitch helps at Lenox Hill. Meanwhile, “it’s important to [realize] that stent migration did not adversely impact [bariatric surgery] failure rates, nor was migration associated with the incidence of revision surgery,” said surgery resident Varun Krishnan, MD.

Dr. Krishnan was the lead investigator on a review of 37 leak cases at Lenox Hill from 2005 to 2017, 17 before overstitch was begun in 2012, and 20 afterwards, with follow-up out to 71 months. The results were presented at the World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS. The senior investigator was Lenox Hill surgeon Julio Teixeira, MD, FACS, associate professor of medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. He reported the first use of stents for bariatric leaks in 2007 (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007 Jan-Feb;3[1]:68-71).

The goal of the review was to address lingering concerns about long-term effects of stents on weight loss and other issues. In the end, “our experience with stenting has been very positive. It’s a very good [option] for treating leaks after bariatric surgery,” Dr. Krishnan said,

The overall success rate was 95%. The 2 failures were both in the sleeve gastrectomy patient group, which made up 43% of the 37 leak cases. The leaks were fixed in one sleeve patient with conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and the other with a stent redo. Both were in the overstitch group.

“We had better success with gastric bypass [patients], probably due to anatomy,” Dr. Krishnan noted. Sleeves leave patients with higher intraluminal pressures, which complicate leak healing.

Stents didn’t have any impact on weight loss. Patients lost a mean of 57% of their excess body weight over an average of 21 months.

Out of 20 patients with available data, 5 were readmitted for oral intolerance, another major concern with endoscopic stents; 3 had their stents removed because of it. None required total parenteral nutrition.

Among 17 patients with available data, 7 (41.7%) had poststent reflux; all of them reported proton-pump inhibitor histories.

Of the 37 total cases, 15 patients (41%) had Roux-en-Y bypasses. The remaining six bypass patients received either duodenal switches or foregut procedures.

Two sleeve and four bypass patients (16%) had revisions. One was the conversion to bypass after stent failure, but the others were for intussusception, strictures, reflux, and other problems that didn’t seem related to stents. About six patients were restented, the one case for stent failure plus five or so for migration.

Patients were an average of about 40 years old, and 70% were women. Average preop body mass index was over 40 kg/m2. The one death in the series was from fungal sepsis a year after stent removal.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Krishnan noted that the distal tip of the stent was placed just after the gastrojejunal anastomosis in bypass cases. Also, bariatric surgeons do the endoscopy at Lenox Hill and place the stents.

The investigators did not report any relevant disclosures, and there was no outside funding.

SEATTLE – Endoscopic stent migration fell from 41% of stent cases to 15% after surgeons at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, started to secure stents with a single, proximal figure-of-eight overstitch.

Anastomotic leaks are a major and potentially fatal complication of bariatric surgery. Stents are one of the fix options: An expanding tube is rolled down over the wound to take the pressure off and give it time to heal. The stent is removed after the leak closes, which can take a few weeks or longer.

Stents designed specifically for the procedure will likely address the problem in the near future, but for now, the overstitch helps at Lenox Hill. Meanwhile, “it’s important to [realize] that stent migration did not adversely impact [bariatric surgery] failure rates, nor was migration associated with the incidence of revision surgery,” said surgery resident Varun Krishnan, MD.

Dr. Krishnan was the lead investigator on a review of 37 leak cases at Lenox Hill from 2005 to 2017, 17 before overstitch was begun in 2012, and 20 afterwards, with follow-up out to 71 months. The results were presented at the World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS. The senior investigator was Lenox Hill surgeon Julio Teixeira, MD, FACS, associate professor of medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. He reported the first use of stents for bariatric leaks in 2007 (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007 Jan-Feb;3[1]:68-71).

The goal of the review was to address lingering concerns about long-term effects of stents on weight loss and other issues. In the end, “our experience with stenting has been very positive. It’s a very good [option] for treating leaks after bariatric surgery,” Dr. Krishnan said,

The overall success rate was 95%. The 2 failures were both in the sleeve gastrectomy patient group, which made up 43% of the 37 leak cases. The leaks were fixed in one sleeve patient with conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and the other with a stent redo. Both were in the overstitch group.

“We had better success with gastric bypass [patients], probably due to anatomy,” Dr. Krishnan noted. Sleeves leave patients with higher intraluminal pressures, which complicate leak healing.

Stents didn’t have any impact on weight loss. Patients lost a mean of 57% of their excess body weight over an average of 21 months.

Out of 20 patients with available data, 5 were readmitted for oral intolerance, another major concern with endoscopic stents; 3 had their stents removed because of it. None required total parenteral nutrition.

Among 17 patients with available data, 7 (41.7%) had poststent reflux; all of them reported proton-pump inhibitor histories.

Of the 37 total cases, 15 patients (41%) had Roux-en-Y bypasses. The remaining six bypass patients received either duodenal switches or foregut procedures.

Two sleeve and four bypass patients (16%) had revisions. One was the conversion to bypass after stent failure, but the others were for intussusception, strictures, reflux, and other problems that didn’t seem related to stents. About six patients were restented, the one case for stent failure plus five or so for migration.

Patients were an average of about 40 years old, and 70% were women. Average preop body mass index was over 40 kg/m2. The one death in the series was from fungal sepsis a year after stent removal.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Krishnan noted that the distal tip of the stent was placed just after the gastrojejunal anastomosis in bypass cases. Also, bariatric surgeons do the endoscopy at Lenox Hill and place the stents.

The investigators did not report any relevant disclosures, and there was no outside funding.

REPORTING FROM SAGES 2018

Key clinical point: Consider fixation when endoscopic stents are used for bariatric surgery leaks.

Major finding: Endoscopic stent migration fell from 41% of stent cases to 15% after surgeons at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, started to secure stents with a single, proximal figure-of-eight overstitch.

Study details: A review of 37 leak cases

Disclosures: The investigators did not report any relevant disclosures, and there was no outside funding.

FDA approves marketing of device to control GI bleeding

The Food and Drug Administration announced May 7 that it has permitted marketing of .

Hemospray is an aerosolized spray device that delivers a mineral blend to the bleeding site in the GI tract and is applied during endoscopic procedures and can cover large ulcers or tumors.

The FDA evaluated data from clinical studies consisting of 228 patients with upper and lower GI bleeding, supplemented with evidence from medical literature, including an additional 522 patients. The studies found that Hemospray stopped GI bleeding in 95% of patients within 5 minutes of device usage. Results also found that bleeding recurred, usually within 72 hours, and up to 30 days following device usage, in 20% of patients. Bowel perforation was observed as a serious side effect in approximately 1% of patients.

“The device provides an additional, nonsurgical option for treating upper and lower GI bleeding in certain patients, and may help reduce the risk of death from a GI bleed for many patients,” said Binita Ashar, MD, director, division of surgical devices, in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health in a press release.

Hemospray is not intended for patients who have a gastrointestinal fistula or are at high risk for GI perforation. The device is not intended for use in patients with variceal bleeding. The FDA permitted the marketing of the Hemospray device to Wilson-Cook Medical.*

Read the full press release here.

Correction, 5/10/18: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the patient population that should not be treated with Hemospray.

The Food and Drug Administration announced May 7 that it has permitted marketing of .

Hemospray is an aerosolized spray device that delivers a mineral blend to the bleeding site in the GI tract and is applied during endoscopic procedures and can cover large ulcers or tumors.

The FDA evaluated data from clinical studies consisting of 228 patients with upper and lower GI bleeding, supplemented with evidence from medical literature, including an additional 522 patients. The studies found that Hemospray stopped GI bleeding in 95% of patients within 5 minutes of device usage. Results also found that bleeding recurred, usually within 72 hours, and up to 30 days following device usage, in 20% of patients. Bowel perforation was observed as a serious side effect in approximately 1% of patients.

“The device provides an additional, nonsurgical option for treating upper and lower GI bleeding in certain patients, and may help reduce the risk of death from a GI bleed for many patients,” said Binita Ashar, MD, director, division of surgical devices, in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health in a press release.

Hemospray is not intended for patients who have a gastrointestinal fistula or are at high risk for GI perforation. The device is not intended for use in patients with variceal bleeding. The FDA permitted the marketing of the Hemospray device to Wilson-Cook Medical.*

Read the full press release here.

Correction, 5/10/18: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the patient population that should not be treated with Hemospray.

The Food and Drug Administration announced May 7 that it has permitted marketing of .

Hemospray is an aerosolized spray device that delivers a mineral blend to the bleeding site in the GI tract and is applied during endoscopic procedures and can cover large ulcers or tumors.

The FDA evaluated data from clinical studies consisting of 228 patients with upper and lower GI bleeding, supplemented with evidence from medical literature, including an additional 522 patients. The studies found that Hemospray stopped GI bleeding in 95% of patients within 5 minutes of device usage. Results also found that bleeding recurred, usually within 72 hours, and up to 30 days following device usage, in 20% of patients. Bowel perforation was observed as a serious side effect in approximately 1% of patients.

“The device provides an additional, nonsurgical option for treating upper and lower GI bleeding in certain patients, and may help reduce the risk of death from a GI bleed for many patients,” said Binita Ashar, MD, director, division of surgical devices, in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health in a press release.

Hemospray is not intended for patients who have a gastrointestinal fistula or are at high risk for GI perforation. The device is not intended for use in patients with variceal bleeding. The FDA permitted the marketing of the Hemospray device to Wilson-Cook Medical.*

Read the full press release here.

Correction, 5/10/18: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the patient population that should not be treated with Hemospray.

Restrictive fluids tied to kidney injury after major abdominal surgery

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Compared with a liberal fluid regimen, restricting fluids did not improve disability-free survival and was tied to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Major finding: Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% with restrictive fluids and 5.0% with liberal fluids.

Study details: International randomized trial of 3,000 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Disclosures: Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

Source: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601

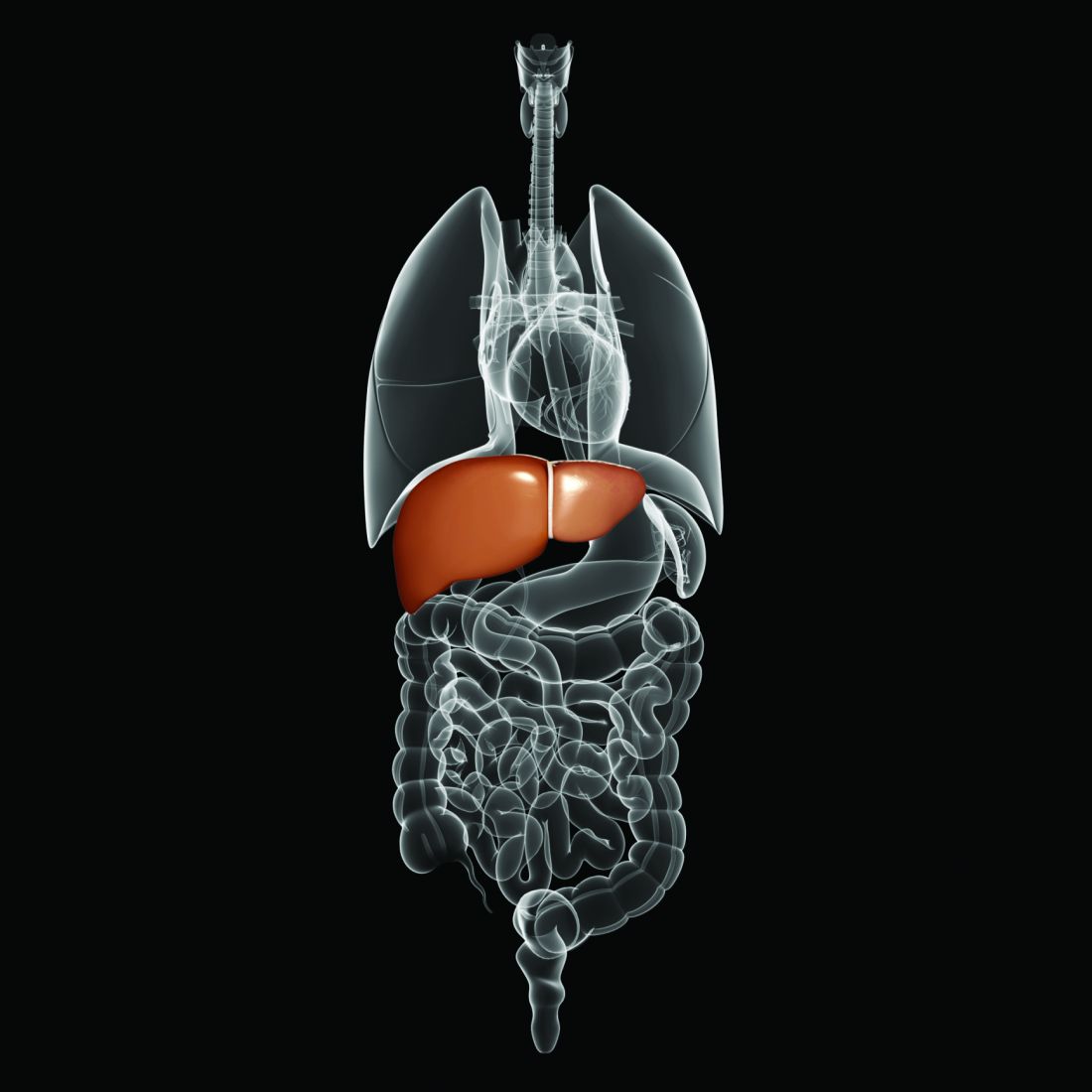

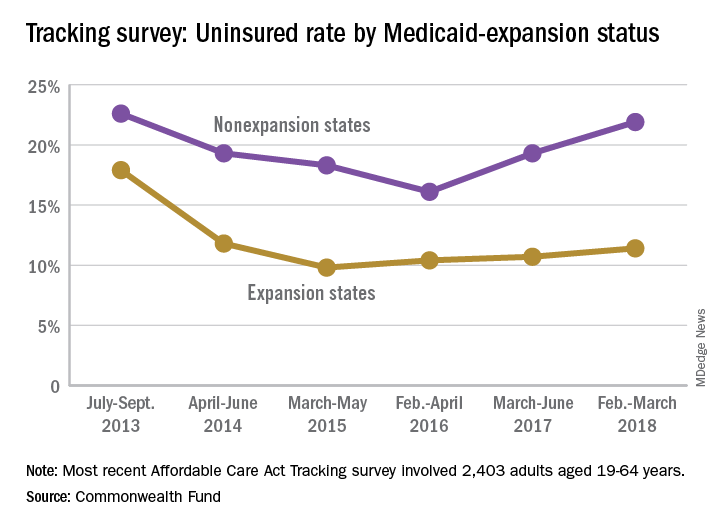

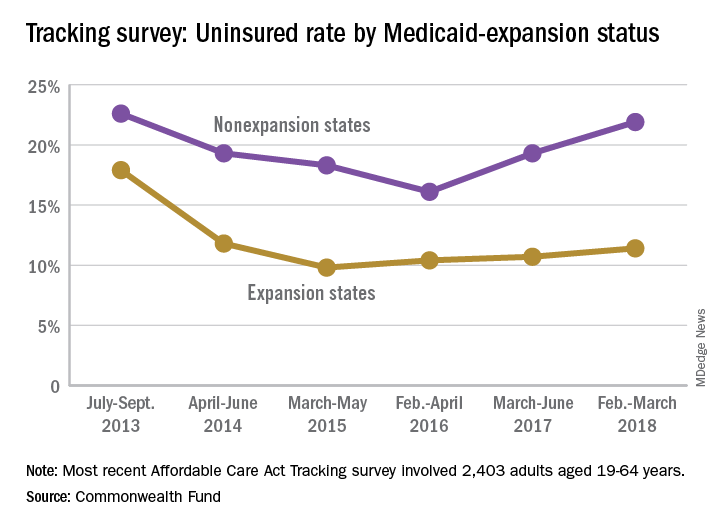

Uninsured rate on the rise

The uninsured rate among Americans aged 19-64 years, which was 12.7% in early 2016, has climbed to 15.5%, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund.

Medicaid expansion has had a significant effect on that increase. The uninsured rate among working-age adults living in states that did not expand their Medicaid programs has gone from 16.1% in 2016 to 21.9% in 2018, while the rate in states that did expand Medicaid rose from 10.4% to 11.4% over that same time, Commonwealth Fund researchers said in reporting the results of their latest (Feb. 6, 2018, to March 30, 2018) Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey.

A similar increase/decrease since 2016 was experienced by respondents who identified as Democrats: The rate for the group went from 9.9% in 2016 to 10.4% in 2017 and then dropped to 9.1% in 2018. Those identifying as Republicans started with a lower rate of 7.9% in 2016 but have since seen it rise to 9.9% in 2017 and 13.9% in 2018, results from the survey of 2,403 adults showed.

“In the absence of bipartisan support for federal action [on the ACA], legislative activity has shifted to the states. Eight states have received, or are currently applying for, federal approval to establish reinsurance programs in their states,” the investigators wrote, but “leaving policy innovation to states will ultimately lead to a patchwork quilt of coverage and access to health care across the country, a dynamic that will fuel inequity in overall health, productivity, and well-being.”

The uninsured rate among Americans aged 19-64 years, which was 12.7% in early 2016, has climbed to 15.5%, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund.

Medicaid expansion has had a significant effect on that increase. The uninsured rate among working-age adults living in states that did not expand their Medicaid programs has gone from 16.1% in 2016 to 21.9% in 2018, while the rate in states that did expand Medicaid rose from 10.4% to 11.4% over that same time, Commonwealth Fund researchers said in reporting the results of their latest (Feb. 6, 2018, to March 30, 2018) Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey.

A similar increase/decrease since 2016 was experienced by respondents who identified as Democrats: The rate for the group went from 9.9% in 2016 to 10.4% in 2017 and then dropped to 9.1% in 2018. Those identifying as Republicans started with a lower rate of 7.9% in 2016 but have since seen it rise to 9.9% in 2017 and 13.9% in 2018, results from the survey of 2,403 adults showed.

“In the absence of bipartisan support for federal action [on the ACA], legislative activity has shifted to the states. Eight states have received, or are currently applying for, federal approval to establish reinsurance programs in their states,” the investigators wrote, but “leaving policy innovation to states will ultimately lead to a patchwork quilt of coverage and access to health care across the country, a dynamic that will fuel inequity in overall health, productivity, and well-being.”

The uninsured rate among Americans aged 19-64 years, which was 12.7% in early 2016, has climbed to 15.5%, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund.

Medicaid expansion has had a significant effect on that increase. The uninsured rate among working-age adults living in states that did not expand their Medicaid programs has gone from 16.1% in 2016 to 21.9% in 2018, while the rate in states that did expand Medicaid rose from 10.4% to 11.4% over that same time, Commonwealth Fund researchers said in reporting the results of their latest (Feb. 6, 2018, to March 30, 2018) Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey.

A similar increase/decrease since 2016 was experienced by respondents who identified as Democrats: The rate for the group went from 9.9% in 2016 to 10.4% in 2017 and then dropped to 9.1% in 2018. Those identifying as Republicans started with a lower rate of 7.9% in 2016 but have since seen it rise to 9.9% in 2017 and 13.9% in 2018, results from the survey of 2,403 adults showed.

“In the absence of bipartisan support for federal action [on the ACA], legislative activity has shifted to the states. Eight states have received, or are currently applying for, federal approval to establish reinsurance programs in their states,” the investigators wrote, but “leaving policy innovation to states will ultimately lead to a patchwork quilt of coverage and access to health care across the country, a dynamic that will fuel inequity in overall health, productivity, and well-being.”

HHS says no to lifetime limits on Medicaid

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

New trial to assess HIV+/HIV+ kidney transplants

The HOPE in Action Multicenter Kidney Study, the first large-scale clinical trial to study kidney transplantations between people with HIV, has begun at clinical centers across the United States, according to an announcement by the National Institutes of Health. The study, sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and NIH, will assess the safety of HIV-positive donor to HIV-positive recipient kidney transplantation. This form of transplantation was made legal by the passage of the HOPE (HIV Organ Policy Equity) Act, which permits the transplantation of organs from donors with HIV into qualified HIV-positive recipients with end-stage organ failure.

Outcomes to be studied in the multicenter trial will include potential transplant-related and HIV-related complications following surgery, as well as organ rejection, organ failure, and failure of previously effective HIV medications. The study is currently enrolling and is expected to include 360 participants, with an estimated completion date of Aug. 1, 2022.

“The HOPE Act of 2013 opened the door for researchers to explore a potential new source of donor organs for those living with HIV – a population with a significant and growing need for transplants. This study offers a chance to improve the health of those living with HIV, and increase the overall supply of transplantable organs,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, MD, in the NIH news release. Transplantation of organs from HIV-positive donors to HIV-negative recipients remains illegal in the United States.

More information about the study can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov using the identifier NCT03500315. A similar trial to examine liver transplantation, the HOPE in Action Multicenter Liver Study, is expected to launch later in 2018.

The HOPE in Action Multicenter Kidney Study, the first large-scale clinical trial to study kidney transplantations between people with HIV, has begun at clinical centers across the United States, according to an announcement by the National Institutes of Health. The study, sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and NIH, will assess the safety of HIV-positive donor to HIV-positive recipient kidney transplantation. This form of transplantation was made legal by the passage of the HOPE (HIV Organ Policy Equity) Act, which permits the transplantation of organs from donors with HIV into qualified HIV-positive recipients with end-stage organ failure.

Outcomes to be studied in the multicenter trial will include potential transplant-related and HIV-related complications following surgery, as well as organ rejection, organ failure, and failure of previously effective HIV medications. The study is currently enrolling and is expected to include 360 participants, with an estimated completion date of Aug. 1, 2022.

“The HOPE Act of 2013 opened the door for researchers to explore a potential new source of donor organs for those living with HIV – a population with a significant and growing need for transplants. This study offers a chance to improve the health of those living with HIV, and increase the overall supply of transplantable organs,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, MD, in the NIH news release. Transplantation of organs from HIV-positive donors to HIV-negative recipients remains illegal in the United States.

More information about the study can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov using the identifier NCT03500315. A similar trial to examine liver transplantation, the HOPE in Action Multicenter Liver Study, is expected to launch later in 2018.

The HOPE in Action Multicenter Kidney Study, the first large-scale clinical trial to study kidney transplantations between people with HIV, has begun at clinical centers across the United States, according to an announcement by the National Institutes of Health. The study, sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and NIH, will assess the safety of HIV-positive donor to HIV-positive recipient kidney transplantation. This form of transplantation was made legal by the passage of the HOPE (HIV Organ Policy Equity) Act, which permits the transplantation of organs from donors with HIV into qualified HIV-positive recipients with end-stage organ failure.

Outcomes to be studied in the multicenter trial will include potential transplant-related and HIV-related complications following surgery, as well as organ rejection, organ failure, and failure of previously effective HIV medications. The study is currently enrolling and is expected to include 360 participants, with an estimated completion date of Aug. 1, 2022.

“The HOPE Act of 2013 opened the door for researchers to explore a potential new source of donor organs for those living with HIV – a population with a significant and growing need for transplants. This study offers a chance to improve the health of those living with HIV, and increase the overall supply of transplantable organs,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, MD, in the NIH news release. Transplantation of organs from HIV-positive donors to HIV-negative recipients remains illegal in the United States.

More information about the study can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov using the identifier NCT03500315. A similar trial to examine liver transplantation, the HOPE in Action Multicenter Liver Study, is expected to launch later in 2018.

Class III obesity increases risk of acute on chronic liver failure in cirrhotic patients

Class III obesity was significantly, independently associated with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and patients with both class III obesity and acute on chronic liver failure also had a significant risk of renal failure, according to a recent retrospective analysis of two databases publised in the Journal of Hepatology.

Vinay Sundaram, MD, from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and his colleagues evaluated 387,884 patients who were in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) during 2005-2016; were class I or II obese (body mass index 30-39 kg/m2), class III obese (BMI greater than or equal to 40), or not obese (BMI less than 30); and were on a wait list for liver transplantation.

They used the definition of ACLF outlined in the CANONIC (Consortium Acute on Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis) study, which defined it as having “a single hepatic decompensation, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleed, or bacterial infection, and one of the following organ failures: single renal failure, single nonrenal organ failure with renal dysfunction or hepatic encephalopathy, or two nonrenal organ failures,” and confirmed the results in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) databases by using diagnostic coding algorithms to identify factors such as hepatic decompensation, obesity, and ACLF in that study population.

Dr. Sundarem and his colleagues identified 116,704 patients (30.1%) with acute on chronic liver failure in both the UNOS and NIS databases. At the time of liver transplantation, there was a significant association between ACLF and class I and class II obesity (hazard ratio, 1.12; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.19; P less than .001) and class III obesity (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.09-1.41; P less than .001). Other predictors of ACLF in this population were increased age (HR, 1.01 per year; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; P = .037), hepatitis C virus (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.16-1.35; P less than .001) and hepatitis C combined with alcoholic liver disease (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30; P = .002). Regarding organ failure, “renal insufficiency was similar among the three groups,” with increasing obesity class associated with a greater prevalence of renal failure.

“Given the heightened risk of renal failure among obese patients with cirrhosis, we suggest particularly careful management of this fragile population regarding diuretic usage, avoidance of nephrotoxic agents, and administration of an adequate albumin challenge in the setting of acute kidney injury,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers encouraged “an even greater emphasis on weight reduction” for class III obese patients. They noted the association between class III obesity and ACLF is likely caused by an “obesity-related chronic inflammatory state” and said future prospective studies should seek to describe the inflammatory pathways for each condition to predict risk of ACLF in these patients.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sundarem V et al. J Hepatol. 2018 April 27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.016.

Class III obesity was significantly, independently associated with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and patients with both class III obesity and acute on chronic liver failure also had a significant risk of renal failure, according to a recent retrospective analysis of two databases publised in the Journal of Hepatology.

Vinay Sundaram, MD, from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and his colleagues evaluated 387,884 patients who were in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) during 2005-2016; were class I or II obese (body mass index 30-39 kg/m2), class III obese (BMI greater than or equal to 40), or not obese (BMI less than 30); and were on a wait list for liver transplantation.

They used the definition of ACLF outlined in the CANONIC (Consortium Acute on Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis) study, which defined it as having “a single hepatic decompensation, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleed, or bacterial infection, and one of the following organ failures: single renal failure, single nonrenal organ failure with renal dysfunction or hepatic encephalopathy, or two nonrenal organ failures,” and confirmed the results in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) databases by using diagnostic coding algorithms to identify factors such as hepatic decompensation, obesity, and ACLF in that study population.

Dr. Sundarem and his colleagues identified 116,704 patients (30.1%) with acute on chronic liver failure in both the UNOS and NIS databases. At the time of liver transplantation, there was a significant association between ACLF and class I and class II obesity (hazard ratio, 1.12; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.19; P less than .001) and class III obesity (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.09-1.41; P less than .001). Other predictors of ACLF in this population were increased age (HR, 1.01 per year; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; P = .037), hepatitis C virus (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.16-1.35; P less than .001) and hepatitis C combined with alcoholic liver disease (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30; P = .002). Regarding organ failure, “renal insufficiency was similar among the three groups,” with increasing obesity class associated with a greater prevalence of renal failure.

“Given the heightened risk of renal failure among obese patients with cirrhosis, we suggest particularly careful management of this fragile population regarding diuretic usage, avoidance of nephrotoxic agents, and administration of an adequate albumin challenge in the setting of acute kidney injury,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers encouraged “an even greater emphasis on weight reduction” for class III obese patients. They noted the association between class III obesity and ACLF is likely caused by an “obesity-related chronic inflammatory state” and said future prospective studies should seek to describe the inflammatory pathways for each condition to predict risk of ACLF in these patients.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sundarem V et al. J Hepatol. 2018 April 27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.016.

Class III obesity was significantly, independently associated with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, and patients with both class III obesity and acute on chronic liver failure also had a significant risk of renal failure, according to a recent retrospective analysis of two databases publised in the Journal of Hepatology.

Vinay Sundaram, MD, from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and his colleagues evaluated 387,884 patients who were in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) during 2005-2016; were class I or II obese (body mass index 30-39 kg/m2), class III obese (BMI greater than or equal to 40), or not obese (BMI less than 30); and were on a wait list for liver transplantation.

They used the definition of ACLF outlined in the CANONIC (Consortium Acute on Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis) study, which defined it as having “a single hepatic decompensation, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleed, or bacterial infection, and one of the following organ failures: single renal failure, single nonrenal organ failure with renal dysfunction or hepatic encephalopathy, or two nonrenal organ failures,” and confirmed the results in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) databases by using diagnostic coding algorithms to identify factors such as hepatic decompensation, obesity, and ACLF in that study population.

Dr. Sundarem and his colleagues identified 116,704 patients (30.1%) with acute on chronic liver failure in both the UNOS and NIS databases. At the time of liver transplantation, there was a significant association between ACLF and class I and class II obesity (hazard ratio, 1.12; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.19; P less than .001) and class III obesity (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.09-1.41; P less than .001). Other predictors of ACLF in this population were increased age (HR, 1.01 per year; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; P = .037), hepatitis C virus (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.16-1.35; P less than .001) and hepatitis C combined with alcoholic liver disease (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30; P = .002). Regarding organ failure, “renal insufficiency was similar among the three groups,” with increasing obesity class associated with a greater prevalence of renal failure.

“Given the heightened risk of renal failure among obese patients with cirrhosis, we suggest particularly careful management of this fragile population regarding diuretic usage, avoidance of nephrotoxic agents, and administration of an adequate albumin challenge in the setting of acute kidney injury,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers encouraged “an even greater emphasis on weight reduction” for class III obese patients. They noted the association between class III obesity and ACLF is likely caused by an “obesity-related chronic inflammatory state” and said future prospective studies should seek to describe the inflammatory pathways for each condition to predict risk of ACLF in these patients.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.