User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Study supports observation for select cases of porcelain gallbladder

Some adults with porcelain gallbladder may be eligible to forgo prophylactic cholecystectomy, suggest the results of a single-center retrospective study.

Over 1.7 years of median follow-up (range, 0 to 12.7 years), the observational group had no detected gallbladder malignancies and 4% developed adverse events versus 13% in the prophylactic cholecystectomy group (P = .15), wrote Haley DesJardins and her associates at Tufts University, Boston. The report was published in the Journal of the American College of Surgery.

The findings “still raise concern about an association between gallbladder wall calcifications and gallbladder malignancies, and therefore still suggest the need for cholecystectomy in the young, healthy, or symptomatic patient,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, surveillance for patients “who are poor surgical candidates is a reasonable approach, with a low risk of malignancy over a limited time frame.”

The investigators suggest that surgeons consider intervention when symptoms and workup points to gallbladder malignancy. But consider avoiding prophylactic cholecystectomy in patients with “limited life expectancy and significant comorbidities,” they emphasized. “Based on the results of this study, the act of prophylactic cholecystectomy for every single patient with gallbladder wall calcifications seems obsolete.”

The study comprised 113 patients with porcelain gallbladder diagnosed between 2004 and 2016. Radiographic reviews identified 70 definite cases and 43 “highly probable” cases. In all, 90 patients started out with observation only, of whom 26% with abdominal pain did not have cholecystectomy because of “significant comorbidities.” Four patients (4.4%) in the observational group subsequently underwent cholecystectomy for biliary colic, as part of liver transplantation, or for prophylactic reasons. None developed complications. In all, 11% developed new gallstones on follow-up imaging and 8% showed progression from focal to diffuse porcelain bladder, the researchers said. None developed gallbladder malignancy during 1.7 years of median follow-up.

Histopathologies of the operative group identified two cases of gallbladder malignancy, of which one was detected on initial imaging. “This patient had a mass at the gallbladder infundibulum extending into the hepatic duct bifurcation,” the researchers explained. “It was not entirely evident whether the resected adenocarcinoma was originating from the gallbladder or from the bile duct. For the purpose of this study, this patient was listed as [having] gallbladder cancer.” The second case consisted of metastatic squamous cell gallbladder carcinoma.

The investigators concluded that “while it is seemingly very reasonable to observe asymptomatic patients with limited life expectancy and significant comorbidities, the decision to proceed with prophylactic cholecystectomy versus observation remains in the hands of the treating physician and patient; especially since absolute criteria or cut-offs cannot be defined at this point.”

No external funding sources were reported. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DesJardins H et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.026.

Some adults with porcelain gallbladder may be eligible to forgo prophylactic cholecystectomy, suggest the results of a single-center retrospective study.

Over 1.7 years of median follow-up (range, 0 to 12.7 years), the observational group had no detected gallbladder malignancies and 4% developed adverse events versus 13% in the prophylactic cholecystectomy group (P = .15), wrote Haley DesJardins and her associates at Tufts University, Boston. The report was published in the Journal of the American College of Surgery.

The findings “still raise concern about an association between gallbladder wall calcifications and gallbladder malignancies, and therefore still suggest the need for cholecystectomy in the young, healthy, or symptomatic patient,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, surveillance for patients “who are poor surgical candidates is a reasonable approach, with a low risk of malignancy over a limited time frame.”

The investigators suggest that surgeons consider intervention when symptoms and workup points to gallbladder malignancy. But consider avoiding prophylactic cholecystectomy in patients with “limited life expectancy and significant comorbidities,” they emphasized. “Based on the results of this study, the act of prophylactic cholecystectomy for every single patient with gallbladder wall calcifications seems obsolete.”

The study comprised 113 patients with porcelain gallbladder diagnosed between 2004 and 2016. Radiographic reviews identified 70 definite cases and 43 “highly probable” cases. In all, 90 patients started out with observation only, of whom 26% with abdominal pain did not have cholecystectomy because of “significant comorbidities.” Four patients (4.4%) in the observational group subsequently underwent cholecystectomy for biliary colic, as part of liver transplantation, or for prophylactic reasons. None developed complications. In all, 11% developed new gallstones on follow-up imaging and 8% showed progression from focal to diffuse porcelain bladder, the researchers said. None developed gallbladder malignancy during 1.7 years of median follow-up.

Histopathologies of the operative group identified two cases of gallbladder malignancy, of which one was detected on initial imaging. “This patient had a mass at the gallbladder infundibulum extending into the hepatic duct bifurcation,” the researchers explained. “It was not entirely evident whether the resected adenocarcinoma was originating from the gallbladder or from the bile duct. For the purpose of this study, this patient was listed as [having] gallbladder cancer.” The second case consisted of metastatic squamous cell gallbladder carcinoma.

The investigators concluded that “while it is seemingly very reasonable to observe asymptomatic patients with limited life expectancy and significant comorbidities, the decision to proceed with prophylactic cholecystectomy versus observation remains in the hands of the treating physician and patient; especially since absolute criteria or cut-offs cannot be defined at this point.”

No external funding sources were reported. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DesJardins H et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.026.

Some adults with porcelain gallbladder may be eligible to forgo prophylactic cholecystectomy, suggest the results of a single-center retrospective study.

Over 1.7 years of median follow-up (range, 0 to 12.7 years), the observational group had no detected gallbladder malignancies and 4% developed adverse events versus 13% in the prophylactic cholecystectomy group (P = .15), wrote Haley DesJardins and her associates at Tufts University, Boston. The report was published in the Journal of the American College of Surgery.

The findings “still raise concern about an association between gallbladder wall calcifications and gallbladder malignancies, and therefore still suggest the need for cholecystectomy in the young, healthy, or symptomatic patient,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, surveillance for patients “who are poor surgical candidates is a reasonable approach, with a low risk of malignancy over a limited time frame.”

The investigators suggest that surgeons consider intervention when symptoms and workup points to gallbladder malignancy. But consider avoiding prophylactic cholecystectomy in patients with “limited life expectancy and significant comorbidities,” they emphasized. “Based on the results of this study, the act of prophylactic cholecystectomy for every single patient with gallbladder wall calcifications seems obsolete.”

The study comprised 113 patients with porcelain gallbladder diagnosed between 2004 and 2016. Radiographic reviews identified 70 definite cases and 43 “highly probable” cases. In all, 90 patients started out with observation only, of whom 26% with abdominal pain did not have cholecystectomy because of “significant comorbidities.” Four patients (4.4%) in the observational group subsequently underwent cholecystectomy for biliary colic, as part of liver transplantation, or for prophylactic reasons. None developed complications. In all, 11% developed new gallstones on follow-up imaging and 8% showed progression from focal to diffuse porcelain bladder, the researchers said. None developed gallbladder malignancy during 1.7 years of median follow-up.

Histopathologies of the operative group identified two cases of gallbladder malignancy, of which one was detected on initial imaging. “This patient had a mass at the gallbladder infundibulum extending into the hepatic duct bifurcation,” the researchers explained. “It was not entirely evident whether the resected adenocarcinoma was originating from the gallbladder or from the bile duct. For the purpose of this study, this patient was listed as [having] gallbladder cancer.” The second case consisted of metastatic squamous cell gallbladder carcinoma.

The investigators concluded that “while it is seemingly very reasonable to observe asymptomatic patients with limited life expectancy and significant comorbidities, the decision to proceed with prophylactic cholecystectomy versus observation remains in the hands of the treating physician and patient; especially since absolute criteria or cut-offs cannot be defined at this point.”

No external funding sources were reported. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DesJardins H et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.026.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Observation is an option for select patients with porcelain gallbladder .

Major finding: Rates of adverse events were 4% with observation and 13% with surgery (P = .15).

Study details: Single-center retrospective cohort study of 113 patients.

Disclosures: No external funding sources were reported. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: DesJardins H et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.026.

ESBL-B before colorectal surgery ups risk of surgical site infection

MADRID – Patients who are carriers of , despite a standard prophylactic antibiotic regimen.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) occurred in 23% of those who tested positive for the pathogens preoperatively, compared with 10.5% of ESBL-B–negative patients – a significant increased risk of 2.25, Yehuda Carmeli, MD, said at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

ESBL-B was not the infective pathogen in most infection cases, but being a carrier increased the likelihood of an ESBL-B SSI. ESBL-B was the pathogen in 7.2% of the carriers and 1.6% of the noncarriers. However, investigators are still working to determine if the species present in the wound infection are the same as the ones present at baseline, said Dr. Carmeli of Tel Aviv Medical Center.

All of these results are emerging from the WP4 study, which was carried out in three hospitals in Serbia, Switzerland, and Israel. Designed as a before-and-after trial, it tested the theory that identifying ESBL carriers and targeting presurgical antibiotic prophylaxis could improve their surgical outcomes.

WP4 was one of five studies in the multinational R-GNOSIS project. “Resistance in Gram-Negative Organisms: Studying Intervention Strategies” is a 12-million-euro, 5-year European collaborative research project designed to identify effective interventions for reducing the carriage, infection, and spread of multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. From 2012 to 2017, WP4 enrolled almost 4,000 adults scheduled to undergo colorectal surgery (excluding appendectomy or minor anorectal procedures).

Several of the studies were reported at ECCMID 2018.

This portion of R-GNOSIS was intended to investigate the relationship between ESBL-B carriage and postoperative surgical site infections among colorectal surgery patients.

The study comprised 3,626 patients who were preoperatively screened for ESBL-B within 2 weeks of colorectal surgery. The ESBL-B carriage rate was 15.3% overall, but ranged from 12% to 20% by site. Of the carriers, 222 were included in this study sample. They were randomly matched with 444 noncarriers.

Anywhere from 2 weeks to 2 days before surgery, all of the patients received a standard prophylactic antibiotic. This was most often an infusion of 1.5 g cefuroxime plus 500 mg metronidazole. Other cephalosporins were allowed at the clinician’s discretion.

Patients were a mean of 62 years old. Nearly half (48%) had cardiovascular disease and about a third had undergone a prior colorectal surgical procedure. Cancer was the surgical indication in about 70%. Other indications were inflammatory bowel disease and diverticular disease.

A multivariate analysis controlled for age, cardiovascular disease, indication for surgery, and whether the procedure included a rectal resection, retention of drain at the surgical site, or stoma. The model also controlled for National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance score, a three-point scale that estimates surgical infection risk. Among this cohort, 48% were at low risk, 43% at moderate risk, and 10% at high risk.

Dr. Carmeli made no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Carmeli et al, ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1133.

MADRID – Patients who are carriers of , despite a standard prophylactic antibiotic regimen.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) occurred in 23% of those who tested positive for the pathogens preoperatively, compared with 10.5% of ESBL-B–negative patients – a significant increased risk of 2.25, Yehuda Carmeli, MD, said at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

ESBL-B was not the infective pathogen in most infection cases, but being a carrier increased the likelihood of an ESBL-B SSI. ESBL-B was the pathogen in 7.2% of the carriers and 1.6% of the noncarriers. However, investigators are still working to determine if the species present in the wound infection are the same as the ones present at baseline, said Dr. Carmeli of Tel Aviv Medical Center.

All of these results are emerging from the WP4 study, which was carried out in three hospitals in Serbia, Switzerland, and Israel. Designed as a before-and-after trial, it tested the theory that identifying ESBL carriers and targeting presurgical antibiotic prophylaxis could improve their surgical outcomes.

WP4 was one of five studies in the multinational R-GNOSIS project. “Resistance in Gram-Negative Organisms: Studying Intervention Strategies” is a 12-million-euro, 5-year European collaborative research project designed to identify effective interventions for reducing the carriage, infection, and spread of multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. From 2012 to 2017, WP4 enrolled almost 4,000 adults scheduled to undergo colorectal surgery (excluding appendectomy or minor anorectal procedures).

Several of the studies were reported at ECCMID 2018.

This portion of R-GNOSIS was intended to investigate the relationship between ESBL-B carriage and postoperative surgical site infections among colorectal surgery patients.

The study comprised 3,626 patients who were preoperatively screened for ESBL-B within 2 weeks of colorectal surgery. The ESBL-B carriage rate was 15.3% overall, but ranged from 12% to 20% by site. Of the carriers, 222 were included in this study sample. They were randomly matched with 444 noncarriers.

Anywhere from 2 weeks to 2 days before surgery, all of the patients received a standard prophylactic antibiotic. This was most often an infusion of 1.5 g cefuroxime plus 500 mg metronidazole. Other cephalosporins were allowed at the clinician’s discretion.

Patients were a mean of 62 years old. Nearly half (48%) had cardiovascular disease and about a third had undergone a prior colorectal surgical procedure. Cancer was the surgical indication in about 70%. Other indications were inflammatory bowel disease and diverticular disease.

A multivariate analysis controlled for age, cardiovascular disease, indication for surgery, and whether the procedure included a rectal resection, retention of drain at the surgical site, or stoma. The model also controlled for National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance score, a three-point scale that estimates surgical infection risk. Among this cohort, 48% were at low risk, 43% at moderate risk, and 10% at high risk.

Dr. Carmeli made no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Carmeli et al, ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1133.

MADRID – Patients who are carriers of , despite a standard prophylactic antibiotic regimen.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) occurred in 23% of those who tested positive for the pathogens preoperatively, compared with 10.5% of ESBL-B–negative patients – a significant increased risk of 2.25, Yehuda Carmeli, MD, said at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

ESBL-B was not the infective pathogen in most infection cases, but being a carrier increased the likelihood of an ESBL-B SSI. ESBL-B was the pathogen in 7.2% of the carriers and 1.6% of the noncarriers. However, investigators are still working to determine if the species present in the wound infection are the same as the ones present at baseline, said Dr. Carmeli of Tel Aviv Medical Center.

All of these results are emerging from the WP4 study, which was carried out in three hospitals in Serbia, Switzerland, and Israel. Designed as a before-and-after trial, it tested the theory that identifying ESBL carriers and targeting presurgical antibiotic prophylaxis could improve their surgical outcomes.

WP4 was one of five studies in the multinational R-GNOSIS project. “Resistance in Gram-Negative Organisms: Studying Intervention Strategies” is a 12-million-euro, 5-year European collaborative research project designed to identify effective interventions for reducing the carriage, infection, and spread of multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. From 2012 to 2017, WP4 enrolled almost 4,000 adults scheduled to undergo colorectal surgery (excluding appendectomy or minor anorectal procedures).

Several of the studies were reported at ECCMID 2018.

This portion of R-GNOSIS was intended to investigate the relationship between ESBL-B carriage and postoperative surgical site infections among colorectal surgery patients.

The study comprised 3,626 patients who were preoperatively screened for ESBL-B within 2 weeks of colorectal surgery. The ESBL-B carriage rate was 15.3% overall, but ranged from 12% to 20% by site. Of the carriers, 222 were included in this study sample. They were randomly matched with 444 noncarriers.

Anywhere from 2 weeks to 2 days before surgery, all of the patients received a standard prophylactic antibiotic. This was most often an infusion of 1.5 g cefuroxime plus 500 mg metronidazole. Other cephalosporins were allowed at the clinician’s discretion.

Patients were a mean of 62 years old. Nearly half (48%) had cardiovascular disease and about a third had undergone a prior colorectal surgical procedure. Cancer was the surgical indication in about 70%. Other indications were inflammatory bowel disease and diverticular disease.

A multivariate analysis controlled for age, cardiovascular disease, indication for surgery, and whether the procedure included a rectal resection, retention of drain at the surgical site, or stoma. The model also controlled for National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance score, a three-point scale that estimates surgical infection risk. Among this cohort, 48% were at low risk, 43% at moderate risk, and 10% at high risk.

Dr. Carmeli made no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Carmeli et al, ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1133.

REPORTING FROM ECCMID 2018

Key clinical point: ESBL-B colonization increased the risk of surgical site infections after colorectal surgery, despite use of standard preoperative antibiotics.

Major finding: ESBL-B carriage more than doubled the risk of a colorectal surgical site infection by (OR 2.25).

Study details: The prospective study comprised 222 carriers and 444 noncarriers.

Disclosures: The study is part of the R-GNOSIS project, a 12-million-euro, 5-year European collaborative research project designed to identify effective interventions for reducing the carriage, infection, and spread of multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

Source: Carmeli Y et al. ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1130.

Two more and counting: Suicide in medical trainees

Like everyone in the arc of social media impact, I was shocked and terribly saddened by the recent suicides of two New York women in medicine – a final-year medical student on May 1 and a second-year resident on May 5. As a specialist in physician health, a former training director, a long-standing member of our institution’s medical student admissions committee, and the ombudsman for our medical students, I am finding these tragedies harder and harder to reconcile. Something isn’t working. But before I get to that, what follows is a bulleted list of some events of the past couple of weeks that may give a context for my statements and have informed my two recommendations.

- May 3, 2018: I give an invited GI grand rounds on stress, burnout, depression, and suicide in physicians. The residents are quiet and say nothing. Faculty members seem only concerned about preventing and eradicating burnout – and not that interested in anything more severe.

- May 5: A psychiatry resident from Melbourne arrives to spend 10 days with me to do an elective in physician health. As in the United States, there is a significant suicide death rate in medical students and residents Down Under. In the afternoon, I present a paper at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychodynamic Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis on the use of psychotherapy in treatment-resistant suicidal depression in physicians. There is increasing hope that this essential modality of care will return to the contemporary psychiatrist’s toolbox.

- May 6: At the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York, I’m the discussant for powerful heartfelt papers of five psychiatrists (mostly early career psychiatrists and one resident) that talked about living with a psychiatric illness. The audience is huge, and we hear narratives about internal stigma, self-disclosure, external stigma, shunning, bullying, acceptance, rejection, alienation, connection, and love by peers and family. The authenticity and valor of the speakers create an atmosphere of safety, which enables psychiatrists in attendance from all over the world to share their personal stories – some at the microphone, some privately.

- May 7: Again at the APA, I chair and facilitate a workshop on physician suicide. We hear from four speakers, all women, who have lost a loved one to suicide – a husband, a father, a brother, a son – all doctors. Two of the speakers are psychiatrists. The stories are gripping, detailed, and tender. Yes, the atmosphere is very sad, but there is not a pall. We learn how these doctors lived, not just how they died. They all loved medicine; they were creative; they cared deeply; they suffered silently; and with shame, they lost hope. Again, a big audience of psychiatrists, many of whom share their own stories, that they, too, had lost a physician son, wife, or mother to suicide. Some of their deceased family members fell through the cracks and did not receive the life-saving care they deserved; some, fearing assaults to their medical license, hospital privileges, or insurance, refused to see anyone. They died untreated.

- May 8: Still at the APA, a psychiatrist colleague and I collaborate on a clinical case conference. Each of us describes losing a physician patient to suicide. We walk the attendees through the clinical details of assessment, treatment, and the aftermath of their deaths. We talk openly and frankly about our feelings, grief, outreach to colleagues and the family, and our own personal journeys of learning, growth, and healing. The clinician audience members give constructive feedback, and some share their own stories of losing patients to suicide. Like the day before, some psychiatrists are grieving the loss of a physician son or sibling to suicide. As mental health professionals, they suffer from an additional layer of failure and guilt that a loved one died “under their watch.”

- May 8: I rush across the Javits Center to catch the discussant for a concurrent symposium on physician burnout and depression. She foregoes any prepared remarks to share her previous 48 hours with the audience. She is the training director of the program that lost the second-year resident on May 5. She did not learn of the death until 24 hours later. We are all on the edge of our seats as we listen to this grieving, courageous woman, a seasoned psychiatrist and educator, who has been blindsided by this tragedy. She has not slept. She called all of her residents and broke the news personally as best she could. Aided by “After A Suicide: A Toolkit for Residency/Fellowship Programs” (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention), she and her colleagues instituted a plan of action and worked with administration and faculty. Her strength and commitment to the well-being of her trainees is palpable and magnanimous. When the session ends, many of us stand in line to give her a hug. It is a stark reminder of how many lives are affected when someone you know or care about takes his/her own life – and how, in the house of medicine, medical students and residents really are part of an institutional family.

- May 10: I facilitate a meeting of our 12 second-year residents, many of whom knew of or had met the resident who died. Almost everyone speaks, shares their feelings, poses questions, and calls for answers and change. There is disbelief, sadness, confusion, some guilt, and lots of anger. Also a feeling of disillusionment or paradox about the field of psychiatry: “Of all branches of medicine, shouldn’t residents who are struggling with psychiatric issues feel safe, protected, cared for in psychiatry?” There is also a feeling of lip service being paid to personal treatment, as in quoted statements: “By all means, get treatment for your issues, but don’t let it encroach on your duty hours” or “It’s good you’re getting help, but do you still have to go weekly?”

In the immediate aftermath of suicide, feelings run high, as they should. But rather than wait it out – and fearing a return to “business as usual” – let me make only two suggestions:

2. In psychiatry, we need to redouble our efforts in fighting the stigma attached to psychiatric illness in trainees. It is unconscionable that medical students and residents are dying of treatable disorders (I’ve never heard of a doctor dying of cancer who didn’t go to an oncologist at least once), yet too many are not availing themselves of services we provide – even when they’re free of charge or covered by insurance. And are we certain that, when they knock on our doors, we are providing them with state-of-the-art care? Is it possible that unrecognized internal stigma and shame deep within us might make us hesitant to help our trainees in their hour of need? Or cut corners? Or not get a second opinion? Very few psychiatrists on faculty of our medical schools divulge their personal experiences of depression, posttraumatic stress disorders, substance use disorders, and more (with the exception of being in therapy during residency, which is normative and isn’t stigmatized). Coming out is leveling, humane, and respectful – and it shrinks the power differential in the teaching dyad. It might even save a life.

Dr. Myers is a professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and the author of “Why Physicians Die by Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Like everyone in the arc of social media impact, I was shocked and terribly saddened by the recent suicides of two New York women in medicine – a final-year medical student on May 1 and a second-year resident on May 5. As a specialist in physician health, a former training director, a long-standing member of our institution’s medical student admissions committee, and the ombudsman for our medical students, I am finding these tragedies harder and harder to reconcile. Something isn’t working. But before I get to that, what follows is a bulleted list of some events of the past couple of weeks that may give a context for my statements and have informed my two recommendations.

- May 3, 2018: I give an invited GI grand rounds on stress, burnout, depression, and suicide in physicians. The residents are quiet and say nothing. Faculty members seem only concerned about preventing and eradicating burnout – and not that interested in anything more severe.

- May 5: A psychiatry resident from Melbourne arrives to spend 10 days with me to do an elective in physician health. As in the United States, there is a significant suicide death rate in medical students and residents Down Under. In the afternoon, I present a paper at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychodynamic Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis on the use of psychotherapy in treatment-resistant suicidal depression in physicians. There is increasing hope that this essential modality of care will return to the contemporary psychiatrist’s toolbox.

- May 6: At the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York, I’m the discussant for powerful heartfelt papers of five psychiatrists (mostly early career psychiatrists and one resident) that talked about living with a psychiatric illness. The audience is huge, and we hear narratives about internal stigma, self-disclosure, external stigma, shunning, bullying, acceptance, rejection, alienation, connection, and love by peers and family. The authenticity and valor of the speakers create an atmosphere of safety, which enables psychiatrists in attendance from all over the world to share their personal stories – some at the microphone, some privately.

- May 7: Again at the APA, I chair and facilitate a workshop on physician suicide. We hear from four speakers, all women, who have lost a loved one to suicide – a husband, a father, a brother, a son – all doctors. Two of the speakers are psychiatrists. The stories are gripping, detailed, and tender. Yes, the atmosphere is very sad, but there is not a pall. We learn how these doctors lived, not just how they died. They all loved medicine; they were creative; they cared deeply; they suffered silently; and with shame, they lost hope. Again, a big audience of psychiatrists, many of whom share their own stories, that they, too, had lost a physician son, wife, or mother to suicide. Some of their deceased family members fell through the cracks and did not receive the life-saving care they deserved; some, fearing assaults to their medical license, hospital privileges, or insurance, refused to see anyone. They died untreated.

- May 8: Still at the APA, a psychiatrist colleague and I collaborate on a clinical case conference. Each of us describes losing a physician patient to suicide. We walk the attendees through the clinical details of assessment, treatment, and the aftermath of their deaths. We talk openly and frankly about our feelings, grief, outreach to colleagues and the family, and our own personal journeys of learning, growth, and healing. The clinician audience members give constructive feedback, and some share their own stories of losing patients to suicide. Like the day before, some psychiatrists are grieving the loss of a physician son or sibling to suicide. As mental health professionals, they suffer from an additional layer of failure and guilt that a loved one died “under their watch.”

- May 8: I rush across the Javits Center to catch the discussant for a concurrent symposium on physician burnout and depression. She foregoes any prepared remarks to share her previous 48 hours with the audience. She is the training director of the program that lost the second-year resident on May 5. She did not learn of the death until 24 hours later. We are all on the edge of our seats as we listen to this grieving, courageous woman, a seasoned psychiatrist and educator, who has been blindsided by this tragedy. She has not slept. She called all of her residents and broke the news personally as best she could. Aided by “After A Suicide: A Toolkit for Residency/Fellowship Programs” (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention), she and her colleagues instituted a plan of action and worked with administration and faculty. Her strength and commitment to the well-being of her trainees is palpable and magnanimous. When the session ends, many of us stand in line to give her a hug. It is a stark reminder of how many lives are affected when someone you know or care about takes his/her own life – and how, in the house of medicine, medical students and residents really are part of an institutional family.

- May 10: I facilitate a meeting of our 12 second-year residents, many of whom knew of or had met the resident who died. Almost everyone speaks, shares their feelings, poses questions, and calls for answers and change. There is disbelief, sadness, confusion, some guilt, and lots of anger. Also a feeling of disillusionment or paradox about the field of psychiatry: “Of all branches of medicine, shouldn’t residents who are struggling with psychiatric issues feel safe, protected, cared for in psychiatry?” There is also a feeling of lip service being paid to personal treatment, as in quoted statements: “By all means, get treatment for your issues, but don’t let it encroach on your duty hours” or “It’s good you’re getting help, but do you still have to go weekly?”

In the immediate aftermath of suicide, feelings run high, as they should. But rather than wait it out – and fearing a return to “business as usual” – let me make only two suggestions:

2. In psychiatry, we need to redouble our efforts in fighting the stigma attached to psychiatric illness in trainees. It is unconscionable that medical students and residents are dying of treatable disorders (I’ve never heard of a doctor dying of cancer who didn’t go to an oncologist at least once), yet too many are not availing themselves of services we provide – even when they’re free of charge or covered by insurance. And are we certain that, when they knock on our doors, we are providing them with state-of-the-art care? Is it possible that unrecognized internal stigma and shame deep within us might make us hesitant to help our trainees in their hour of need? Or cut corners? Or not get a second opinion? Very few psychiatrists on faculty of our medical schools divulge their personal experiences of depression, posttraumatic stress disorders, substance use disorders, and more (with the exception of being in therapy during residency, which is normative and isn’t stigmatized). Coming out is leveling, humane, and respectful – and it shrinks the power differential in the teaching dyad. It might even save a life.

Dr. Myers is a professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and the author of “Why Physicians Die by Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Like everyone in the arc of social media impact, I was shocked and terribly saddened by the recent suicides of two New York women in medicine – a final-year medical student on May 1 and a second-year resident on May 5. As a specialist in physician health, a former training director, a long-standing member of our institution’s medical student admissions committee, and the ombudsman for our medical students, I am finding these tragedies harder and harder to reconcile. Something isn’t working. But before I get to that, what follows is a bulleted list of some events of the past couple of weeks that may give a context for my statements and have informed my two recommendations.

- May 3, 2018: I give an invited GI grand rounds on stress, burnout, depression, and suicide in physicians. The residents are quiet and say nothing. Faculty members seem only concerned about preventing and eradicating burnout – and not that interested in anything more severe.

- May 5: A psychiatry resident from Melbourne arrives to spend 10 days with me to do an elective in physician health. As in the United States, there is a significant suicide death rate in medical students and residents Down Under. In the afternoon, I present a paper at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychodynamic Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis on the use of psychotherapy in treatment-resistant suicidal depression in physicians. There is increasing hope that this essential modality of care will return to the contemporary psychiatrist’s toolbox.

- May 6: At the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York, I’m the discussant for powerful heartfelt papers of five psychiatrists (mostly early career psychiatrists and one resident) that talked about living with a psychiatric illness. The audience is huge, and we hear narratives about internal stigma, self-disclosure, external stigma, shunning, bullying, acceptance, rejection, alienation, connection, and love by peers and family. The authenticity and valor of the speakers create an atmosphere of safety, which enables psychiatrists in attendance from all over the world to share their personal stories – some at the microphone, some privately.

- May 7: Again at the APA, I chair and facilitate a workshop on physician suicide. We hear from four speakers, all women, who have lost a loved one to suicide – a husband, a father, a brother, a son – all doctors. Two of the speakers are psychiatrists. The stories are gripping, detailed, and tender. Yes, the atmosphere is very sad, but there is not a pall. We learn how these doctors lived, not just how they died. They all loved medicine; they were creative; they cared deeply; they suffered silently; and with shame, they lost hope. Again, a big audience of psychiatrists, many of whom share their own stories, that they, too, had lost a physician son, wife, or mother to suicide. Some of their deceased family members fell through the cracks and did not receive the life-saving care they deserved; some, fearing assaults to their medical license, hospital privileges, or insurance, refused to see anyone. They died untreated.

- May 8: Still at the APA, a psychiatrist colleague and I collaborate on a clinical case conference. Each of us describes losing a physician patient to suicide. We walk the attendees through the clinical details of assessment, treatment, and the aftermath of their deaths. We talk openly and frankly about our feelings, grief, outreach to colleagues and the family, and our own personal journeys of learning, growth, and healing. The clinician audience members give constructive feedback, and some share their own stories of losing patients to suicide. Like the day before, some psychiatrists are grieving the loss of a physician son or sibling to suicide. As mental health professionals, they suffer from an additional layer of failure and guilt that a loved one died “under their watch.”

- May 8: I rush across the Javits Center to catch the discussant for a concurrent symposium on physician burnout and depression. She foregoes any prepared remarks to share her previous 48 hours with the audience. She is the training director of the program that lost the second-year resident on May 5. She did not learn of the death until 24 hours later. We are all on the edge of our seats as we listen to this grieving, courageous woman, a seasoned psychiatrist and educator, who has been blindsided by this tragedy. She has not slept. She called all of her residents and broke the news personally as best she could. Aided by “After A Suicide: A Toolkit for Residency/Fellowship Programs” (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention), she and her colleagues instituted a plan of action and worked with administration and faculty. Her strength and commitment to the well-being of her trainees is palpable and magnanimous. When the session ends, many of us stand in line to give her a hug. It is a stark reminder of how many lives are affected when someone you know or care about takes his/her own life – and how, in the house of medicine, medical students and residents really are part of an institutional family.

- May 10: I facilitate a meeting of our 12 second-year residents, many of whom knew of or had met the resident who died. Almost everyone speaks, shares their feelings, poses questions, and calls for answers and change. There is disbelief, sadness, confusion, some guilt, and lots of anger. Also a feeling of disillusionment or paradox about the field of psychiatry: “Of all branches of medicine, shouldn’t residents who are struggling with psychiatric issues feel safe, protected, cared for in psychiatry?” There is also a feeling of lip service being paid to personal treatment, as in quoted statements: “By all means, get treatment for your issues, but don’t let it encroach on your duty hours” or “It’s good you’re getting help, but do you still have to go weekly?”

In the immediate aftermath of suicide, feelings run high, as they should. But rather than wait it out – and fearing a return to “business as usual” – let me make only two suggestions:

2. In psychiatry, we need to redouble our efforts in fighting the stigma attached to psychiatric illness in trainees. It is unconscionable that medical students and residents are dying of treatable disorders (I’ve never heard of a doctor dying of cancer who didn’t go to an oncologist at least once), yet too many are not availing themselves of services we provide – even when they’re free of charge or covered by insurance. And are we certain that, when they knock on our doors, we are providing them with state-of-the-art care? Is it possible that unrecognized internal stigma and shame deep within us might make us hesitant to help our trainees in their hour of need? Or cut corners? Or not get a second opinion? Very few psychiatrists on faculty of our medical schools divulge their personal experiences of depression, posttraumatic stress disorders, substance use disorders, and more (with the exception of being in therapy during residency, which is normative and isn’t stigmatized). Coming out is leveling, humane, and respectful – and it shrinks the power differential in the teaching dyad. It might even save a life.

Dr. Myers is a professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and the author of “Why Physicians Die by Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

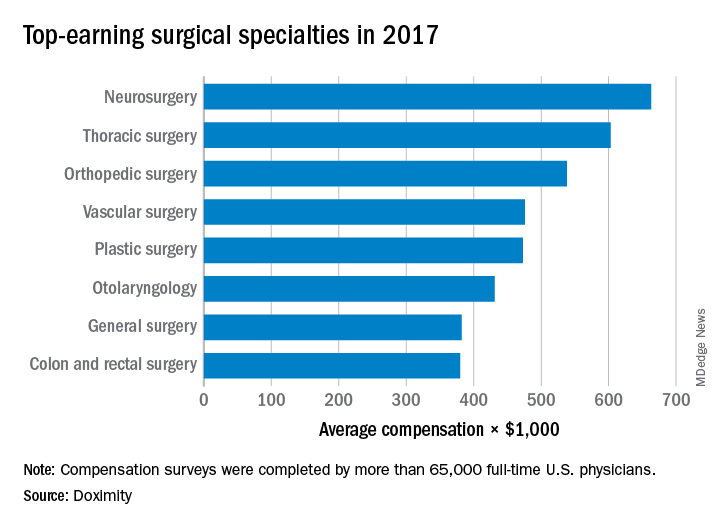

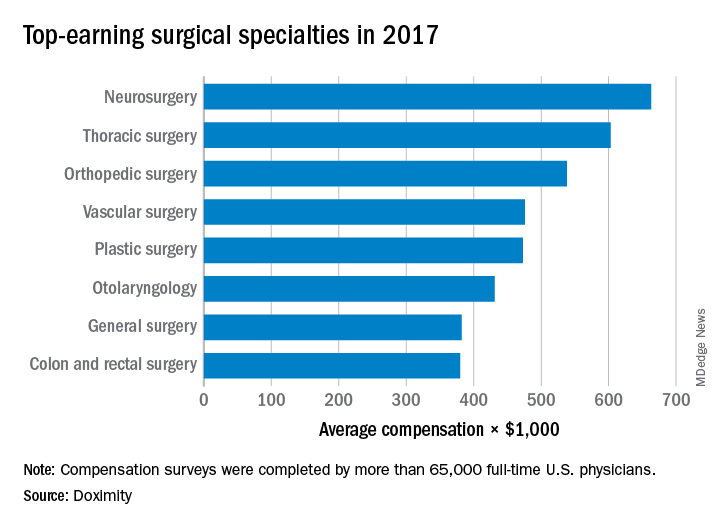

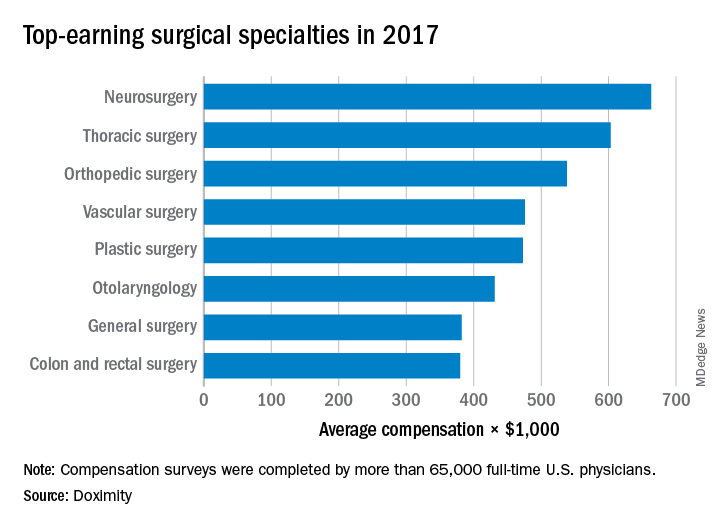

Surgical specialists are top earners

The five top-earning surgical specialties in 2017 also happened to be the five top-earning specialties, according to a survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Neurosurgery was first among all specialties with an average compensation of $663,000, followed by thoracic surgery ($603,000), orthopedic surgery ($538,000), vascular surgery ($476,000), and plastic surgery ($473,212). Cardiology was just behind plastic surgery at $473,184, which made it the highest-earning nonsurgical specialty, Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report, which was based on data from surveys completed by more than 65,000 physicians who practice at least 40 hours a week. Gastroenterologists took in $456,000 and oncologists earned an average of $404,000.

The five top-earning surgical specialties in 2017 also happened to be the five top-earning specialties, according to a survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Neurosurgery was first among all specialties with an average compensation of $663,000, followed by thoracic surgery ($603,000), orthopedic surgery ($538,000), vascular surgery ($476,000), and plastic surgery ($473,212). Cardiology was just behind plastic surgery at $473,184, which made it the highest-earning nonsurgical specialty, Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report, which was based on data from surveys completed by more than 65,000 physicians who practice at least 40 hours a week. Gastroenterologists took in $456,000 and oncologists earned an average of $404,000.

The five top-earning surgical specialties in 2017 also happened to be the five top-earning specialties, according to a survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Neurosurgery was first among all specialties with an average compensation of $663,000, followed by thoracic surgery ($603,000), orthopedic surgery ($538,000), vascular surgery ($476,000), and plastic surgery ($473,212). Cardiology was just behind plastic surgery at $473,184, which made it the highest-earning nonsurgical specialty, Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report, which was based on data from surveys completed by more than 65,000 physicians who practice at least 40 hours a week. Gastroenterologists took in $456,000 and oncologists earned an average of $404,000.

Surgery may be best option for hip impingement syndrome

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Hip arthroscopic surgery produced better long-term results than did personalized hip physiotherapy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome in a randomized trial conduced across multiple U.K. centers.

At 12 months, respective International Hip Outcome Tool-33 (iHOT-33) scores were 58.8 and 49.7, a difference of 9.1 points before and 6.8 points after adjustment for potential confounding factors (P = .0093).

“This trial shows that hip arthroscopic surgery and personalized hip therapy both improved hip-related quality of life for patients with FAI [femoroacetabular impingement] syndrome, but that the surgery did indeed produce a greater improvement at our primary time point of 12 months,” she added. Dr. Foster is professor of musculoskeletal health in primary care at Keele University, Newcastle-under-Lyme, England, one of the 23 centers involved in the FASHIoN study in England, Wales, and Scotland.

“FAI is a very common cause of hip and groin pain in young adults, and it’s associated with the development of hip osteoarthritis,” Dr. Foster noted.

There are three types of FAI – pincer, cam, and combined. The pincer type of FAI is where there is “prominence or overcoverage of the rim of the acetabulum,” and the cam type is where there is a “bony prominence of the femoral head-neck junction,” she explained at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The link to OA comes when the femur and acetabulum prematurely connect, usually during activity, causing damage to the labrum and articular cartilage in the long term. Thus, treating FAI is important, not just for relieving patient’s pain and joint stiffness.

Hip arthroscopic surgery has become an established way of treating FAI syndrome – more than 2,400 operations were performed in 2013 in the United Kingdom alone, Dr. Foster observed. The aim of surgery is to try to reshape the hip joint to prevent impingement, and resect, repair, or reconstruct any intra-articular damage that may be present.

“Physiotherapy aims to improve hip muscle control and strength, and to correct the abnormal movement patterns that we see in these patients,” Dr. Foster said. “Through that, we hope to prevent the premature contact that occurs in FAI syndrome and thereby improve symptoms, allowing patients to return to activities and prevent recurrence.”

Working with physiotherapists, physicians, and surgeons, Dr. Foster and her associates have previously developed a “best conservative care” intervention that they call personalized hip therapy (PHT), which involves the delivery and supervision of an individualized exercise program by experienced physiotherapists over a 3- to 6-month period, and which patients repeat at home (PM R. 2013 May;5[5]:418-26).

The aim of the UK FASHIoN trial was to compare the clinical and cost-effectiveness of hip arthroscopy and PHT for FAI syndrome, as there was no robust clinical trial evidence to demonstrate a benefit of one over the other.

A total of 351 adults with hip and groin pain were randomized to either arthroscopic surgery (n = 173) or PHT (n = 178). The mean age of participants was 35 years, with no significant differences between the two treatment groups in terms of baseline demographics or type or duration of hip impingement.

While surgery was better in terms of patient outcomes, the study didn’t demonstrate its cost-effectiveness within the first 12 months, Dr. Foster observed. Cost-effectiveness, together with various other quality-of-life measurements, was a secondary endpoint of the study.

“Longer-term outcomes are required to establish whether improvement is sustained, and whether surgery is cost-effective at the longer time points for our health service,” she said.

Responding to a question about whether any of the patients in the study had radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis, Dr. Foster said that such patients had been excluded from the study.

“One of the hopes of the trial’s team is that, with the long-term follow-up, we might be able to get data at 5 and 10 years on things like hip osteoarthritis in these patients,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Foster had no financial relationships or commercial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Griffin DR et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018:26(1):S24-25. Abstract 28

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Hip arthroscopic surgery produced better long-term results than did personalized hip physiotherapy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome in a randomized trial conduced across multiple U.K. centers.

At 12 months, respective International Hip Outcome Tool-33 (iHOT-33) scores were 58.8 and 49.7, a difference of 9.1 points before and 6.8 points after adjustment for potential confounding factors (P = .0093).

“This trial shows that hip arthroscopic surgery and personalized hip therapy both improved hip-related quality of life for patients with FAI [femoroacetabular impingement] syndrome, but that the surgery did indeed produce a greater improvement at our primary time point of 12 months,” she added. Dr. Foster is professor of musculoskeletal health in primary care at Keele University, Newcastle-under-Lyme, England, one of the 23 centers involved in the FASHIoN study in England, Wales, and Scotland.

“FAI is a very common cause of hip and groin pain in young adults, and it’s associated with the development of hip osteoarthritis,” Dr. Foster noted.

There are three types of FAI – pincer, cam, and combined. The pincer type of FAI is where there is “prominence or overcoverage of the rim of the acetabulum,” and the cam type is where there is a “bony prominence of the femoral head-neck junction,” she explained at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The link to OA comes when the femur and acetabulum prematurely connect, usually during activity, causing damage to the labrum and articular cartilage in the long term. Thus, treating FAI is important, not just for relieving patient’s pain and joint stiffness.

Hip arthroscopic surgery has become an established way of treating FAI syndrome – more than 2,400 operations were performed in 2013 in the United Kingdom alone, Dr. Foster observed. The aim of surgery is to try to reshape the hip joint to prevent impingement, and resect, repair, or reconstruct any intra-articular damage that may be present.

“Physiotherapy aims to improve hip muscle control and strength, and to correct the abnormal movement patterns that we see in these patients,” Dr. Foster said. “Through that, we hope to prevent the premature contact that occurs in FAI syndrome and thereby improve symptoms, allowing patients to return to activities and prevent recurrence.”

Working with physiotherapists, physicians, and surgeons, Dr. Foster and her associates have previously developed a “best conservative care” intervention that they call personalized hip therapy (PHT), which involves the delivery and supervision of an individualized exercise program by experienced physiotherapists over a 3- to 6-month period, and which patients repeat at home (PM R. 2013 May;5[5]:418-26).

The aim of the UK FASHIoN trial was to compare the clinical and cost-effectiveness of hip arthroscopy and PHT for FAI syndrome, as there was no robust clinical trial evidence to demonstrate a benefit of one over the other.

A total of 351 adults with hip and groin pain were randomized to either arthroscopic surgery (n = 173) or PHT (n = 178). The mean age of participants was 35 years, with no significant differences between the two treatment groups in terms of baseline demographics or type or duration of hip impingement.

While surgery was better in terms of patient outcomes, the study didn’t demonstrate its cost-effectiveness within the first 12 months, Dr. Foster observed. Cost-effectiveness, together with various other quality-of-life measurements, was a secondary endpoint of the study.

“Longer-term outcomes are required to establish whether improvement is sustained, and whether surgery is cost-effective at the longer time points for our health service,” she said.

Responding to a question about whether any of the patients in the study had radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis, Dr. Foster said that such patients had been excluded from the study.

“One of the hopes of the trial’s team is that, with the long-term follow-up, we might be able to get data at 5 and 10 years on things like hip osteoarthritis in these patients,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Foster had no financial relationships or commercial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Griffin DR et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018:26(1):S24-25. Abstract 28

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Hip arthroscopic surgery produced better long-term results than did personalized hip physiotherapy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome in a randomized trial conduced across multiple U.K. centers.

At 12 months, respective International Hip Outcome Tool-33 (iHOT-33) scores were 58.8 and 49.7, a difference of 9.1 points before and 6.8 points after adjustment for potential confounding factors (P = .0093).

“This trial shows that hip arthroscopic surgery and personalized hip therapy both improved hip-related quality of life for patients with FAI [femoroacetabular impingement] syndrome, but that the surgery did indeed produce a greater improvement at our primary time point of 12 months,” she added. Dr. Foster is professor of musculoskeletal health in primary care at Keele University, Newcastle-under-Lyme, England, one of the 23 centers involved in the FASHIoN study in England, Wales, and Scotland.

“FAI is a very common cause of hip and groin pain in young adults, and it’s associated with the development of hip osteoarthritis,” Dr. Foster noted.

There are three types of FAI – pincer, cam, and combined. The pincer type of FAI is where there is “prominence or overcoverage of the rim of the acetabulum,” and the cam type is where there is a “bony prominence of the femoral head-neck junction,” she explained at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The link to OA comes when the femur and acetabulum prematurely connect, usually during activity, causing damage to the labrum and articular cartilage in the long term. Thus, treating FAI is important, not just for relieving patient’s pain and joint stiffness.

Hip arthroscopic surgery has become an established way of treating FAI syndrome – more than 2,400 operations were performed in 2013 in the United Kingdom alone, Dr. Foster observed. The aim of surgery is to try to reshape the hip joint to prevent impingement, and resect, repair, or reconstruct any intra-articular damage that may be present.

“Physiotherapy aims to improve hip muscle control and strength, and to correct the abnormal movement patterns that we see in these patients,” Dr. Foster said. “Through that, we hope to prevent the premature contact that occurs in FAI syndrome and thereby improve symptoms, allowing patients to return to activities and prevent recurrence.”

Working with physiotherapists, physicians, and surgeons, Dr. Foster and her associates have previously developed a “best conservative care” intervention that they call personalized hip therapy (PHT), which involves the delivery and supervision of an individualized exercise program by experienced physiotherapists over a 3- to 6-month period, and which patients repeat at home (PM R. 2013 May;5[5]:418-26).

The aim of the UK FASHIoN trial was to compare the clinical and cost-effectiveness of hip arthroscopy and PHT for FAI syndrome, as there was no robust clinical trial evidence to demonstrate a benefit of one over the other.

A total of 351 adults with hip and groin pain were randomized to either arthroscopic surgery (n = 173) or PHT (n = 178). The mean age of participants was 35 years, with no significant differences between the two treatment groups in terms of baseline demographics or type or duration of hip impingement.

While surgery was better in terms of patient outcomes, the study didn’t demonstrate its cost-effectiveness within the first 12 months, Dr. Foster observed. Cost-effectiveness, together with various other quality-of-life measurements, was a secondary endpoint of the study.

“Longer-term outcomes are required to establish whether improvement is sustained, and whether surgery is cost-effective at the longer time points for our health service,” she said.

Responding to a question about whether any of the patients in the study had radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis, Dr. Foster said that such patients had been excluded from the study.

“One of the hopes of the trial’s team is that, with the long-term follow-up, we might be able to get data at 5 and 10 years on things like hip osteoarthritis in these patients,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Foster had no financial relationships or commercial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Griffin DR et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018:26(1):S24-25. Abstract 28

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2018

Key clinical point: Hip arthroscopy produced better results at 12 months than did the best conservative care.

Major finding: iHOT-33 scores at 12 months were 58.3 for surgery and 49.7 for personalized hip therapy (P = .0093)

Study details: Multicenter, randomized controlled UK FASHIoN trial of 351 adults with hip and groin pain.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Foster had nothing to disclose.

Source: Griffin DR et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018:26(1):S24-25. Abstract 28.

Patients who record office visits

Question: During an office visit, the patient used a smartphone to record his conversation with the doctor. Which of the following statements is best?

A. This is an intrusion into a private and confidential physician-patient encounter and violates laws against eavesdropping and wiretapping.

B. Recordings are rarely made in the doctor’s office.

C. Both parties must consent before the patient or doctor can legally make such a recording.

D. Surreptitious recording by one party is always illegal.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E.

Scholars from Dartmouth recently published their viewpoint on this topic in the Aug. 7, 2017, issue of JAMA.1 Many individuals believe that taping or recording a private conversation is per se illegal.

This is a misconception. Although it is a serious felony to violate wiretapping laws, in fact every jurisdiction permits the taping or recording of doctor-patient conversations where there is all-party consent. A majority of states actually allow the recording even if one party has not given his/her consent. This one-party consent rule is the law in 39 states, including Hawaii and New York. On the other hand, 11 states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Washington, deem such recordings illegal. A listing of the law in the various states can be found in the JAMA article, in which the authors call for “clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings.”

In a 2011 case against the Cleveland Clinic, a patient died of a cardiac arrest from hyperkalemia 3 days after elective knee surgery.2 The patient’s children had made a covert recording of a meeting with the chief medical officer when discussing the incident. The hospital attempted to bar the use of the recording, claiming that the information was nondiscoverable under the “peer review” privilege.

Both the trial court and the court of appeals disagreed, being unconvinced that such discussions fell within peer review protection. That the recording was made surreptitiously was not raised as an issue, as Ohio is a one-party consent state, i.e., the law permits a patient to legally tape his/her conversations without obtaining prior approval from the doctor.3

There are clear advantages to having a permanent record of a doctor’s professional opinion. The patient can review the information after the visit for a better understanding or for recall purposes, even sharing the information with family members, caregivers, or others, especially where there is a lack of clarity on instructions.4 In the area of informed consent, this is particularly useful for a reminder of medication side effects and potential complications of proposed surgery.

However, many doctors believe that recordings may be disruptive or prove inhibitory to free and open discussions, and they are concerned about their potential use should litigation arises.

Risk managers and malpractice carriers are divided in their views. For example, it has been stated that, “at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, clinicians who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage” (P.J. Barr, unpublished data, 2017, as cited in reference 1). Other carriers are not as supportive, discouraging their insureds from allowing recordings to be made.

In the majority of jurisdictions, recordings are legal if consented to by one of the parties. This means that recordings by the patient with/without consent from or with/without knowledge of the doctor are fully legitimate. It also means that the recordings will be admissible into evidence in a courtroom, unless the information is privileged (protected from discovery) or is otherwise irrelevant or unreliable.

On the other hand, in states requiring all-party consent, such recordings are illegal absent across-the-board consent, and they will be inadmissible into evidence. This cardinal difference in state law raises vital implications for both plaintiff and defendant in litigation, because the recordings may contain incriminating or exculpatory information.

Recordings of conversations in the doctor’s office are by no means rare. A survey in the United Kingdom revealed that 15% of the public had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 11% were aware of someone else doing the same.5 The concerned physician could proactively prohibit all office recordings by posting a “no recording” sign in the waiting room in the name of confidentiality and privacy. And should a physician discover that a patient is covertly recording, risk managers have suggested terminating the visit with a warning that a repeat attempt will result in discharge.

Like it or not, recordings are here to stay, and the omnipresence of modern communications devices such as smartphones, tablets, etc., is likely to increase the prevalence of recordings. A practical approach for practicing physicians is to familiarize themselves with the law in the individual state in which they practice and to improve their communication skills irrespective of whether or not there is a recording.

They may wish to consider the view attributed to Richard Boothman, JD, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System: “Recording should cause any caregiver to mind their professionalism and be disciplined in their remarks to their patients. … I believe it can be a very powerful tool to cement the patient/physician relationship and the patient’s understanding of the clinical messages and information. Physicians are significantly benefited by an informed patient.”6

References

1. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8;318(6):513-4.

2. Smith v. Cleveland Clinic, 197 Ohio App.3d 524, 2011.

3. Ohio Revised Code 2933.52.

4. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1615-6.

5. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 11;5(8):e008566.

6. “Your office is being recorded.” Medscape, April 3, 2018.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: During an office visit, the patient used a smartphone to record his conversation with the doctor. Which of the following statements is best?

A. This is an intrusion into a private and confidential physician-patient encounter and violates laws against eavesdropping and wiretapping.

B. Recordings are rarely made in the doctor’s office.

C. Both parties must consent before the patient or doctor can legally make such a recording.

D. Surreptitious recording by one party is always illegal.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E.

Scholars from Dartmouth recently published their viewpoint on this topic in the Aug. 7, 2017, issue of JAMA.1 Many individuals believe that taping or recording a private conversation is per se illegal.

This is a misconception. Although it is a serious felony to violate wiretapping laws, in fact every jurisdiction permits the taping or recording of doctor-patient conversations where there is all-party consent. A majority of states actually allow the recording even if one party has not given his/her consent. This one-party consent rule is the law in 39 states, including Hawaii and New York. On the other hand, 11 states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Washington, deem such recordings illegal. A listing of the law in the various states can be found in the JAMA article, in which the authors call for “clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings.”

In a 2011 case against the Cleveland Clinic, a patient died of a cardiac arrest from hyperkalemia 3 days after elective knee surgery.2 The patient’s children had made a covert recording of a meeting with the chief medical officer when discussing the incident. The hospital attempted to bar the use of the recording, claiming that the information was nondiscoverable under the “peer review” privilege.

Both the trial court and the court of appeals disagreed, being unconvinced that such discussions fell within peer review protection. That the recording was made surreptitiously was not raised as an issue, as Ohio is a one-party consent state, i.e., the law permits a patient to legally tape his/her conversations without obtaining prior approval from the doctor.3

There are clear advantages to having a permanent record of a doctor’s professional opinion. The patient can review the information after the visit for a better understanding or for recall purposes, even sharing the information with family members, caregivers, or others, especially where there is a lack of clarity on instructions.4 In the area of informed consent, this is particularly useful for a reminder of medication side effects and potential complications of proposed surgery.

However, many doctors believe that recordings may be disruptive or prove inhibitory to free and open discussions, and they are concerned about their potential use should litigation arises.

Risk managers and malpractice carriers are divided in their views. For example, it has been stated that, “at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, clinicians who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage” (P.J. Barr, unpublished data, 2017, as cited in reference 1). Other carriers are not as supportive, discouraging their insureds from allowing recordings to be made.

In the majority of jurisdictions, recordings are legal if consented to by one of the parties. This means that recordings by the patient with/without consent from or with/without knowledge of the doctor are fully legitimate. It also means that the recordings will be admissible into evidence in a courtroom, unless the information is privileged (protected from discovery) or is otherwise irrelevant or unreliable.

On the other hand, in states requiring all-party consent, such recordings are illegal absent across-the-board consent, and they will be inadmissible into evidence. This cardinal difference in state law raises vital implications for both plaintiff and defendant in litigation, because the recordings may contain incriminating or exculpatory information.

Recordings of conversations in the doctor’s office are by no means rare. A survey in the United Kingdom revealed that 15% of the public had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 11% were aware of someone else doing the same.5 The concerned physician could proactively prohibit all office recordings by posting a “no recording” sign in the waiting room in the name of confidentiality and privacy. And should a physician discover that a patient is covertly recording, risk managers have suggested terminating the visit with a warning that a repeat attempt will result in discharge.

Like it or not, recordings are here to stay, and the omnipresence of modern communications devices such as smartphones, tablets, etc., is likely to increase the prevalence of recordings. A practical approach for practicing physicians is to familiarize themselves with the law in the individual state in which they practice and to improve their communication skills irrespective of whether or not there is a recording.

They may wish to consider the view attributed to Richard Boothman, JD, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System: “Recording should cause any caregiver to mind their professionalism and be disciplined in their remarks to their patients. … I believe it can be a very powerful tool to cement the patient/physician relationship and the patient’s understanding of the clinical messages and information. Physicians are significantly benefited by an informed patient.”6

References

1. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8;318(6):513-4.

2. Smith v. Cleveland Clinic, 197 Ohio App.3d 524, 2011.

3. Ohio Revised Code 2933.52.

4. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1615-6.

5. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 11;5(8):e008566.

6. “Your office is being recorded.” Medscape, April 3, 2018.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: During an office visit, the patient used a smartphone to record his conversation with the doctor. Which of the following statements is best?

A. This is an intrusion into a private and confidential physician-patient encounter and violates laws against eavesdropping and wiretapping.

B. Recordings are rarely made in the doctor’s office.

C. Both parties must consent before the patient or doctor can legally make such a recording.

D. Surreptitious recording by one party is always illegal.

E. All are incorrect.

Answer: E.

Scholars from Dartmouth recently published their viewpoint on this topic in the Aug. 7, 2017, issue of JAMA.1 Many individuals believe that taping or recording a private conversation is per se illegal.

This is a misconception. Although it is a serious felony to violate wiretapping laws, in fact every jurisdiction permits the taping or recording of doctor-patient conversations where there is all-party consent. A majority of states actually allow the recording even if one party has not given his/her consent. This one-party consent rule is the law in 39 states, including Hawaii and New York. On the other hand, 11 states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Washington, deem such recordings illegal. A listing of the law in the various states can be found in the JAMA article, in which the authors call for “clear policies that facilitate the positive use of digital recordings.”

In a 2011 case against the Cleveland Clinic, a patient died of a cardiac arrest from hyperkalemia 3 days after elective knee surgery.2 The patient’s children had made a covert recording of a meeting with the chief medical officer when discussing the incident. The hospital attempted to bar the use of the recording, claiming that the information was nondiscoverable under the “peer review” privilege.

Both the trial court and the court of appeals disagreed, being unconvinced that such discussions fell within peer review protection. That the recording was made surreptitiously was not raised as an issue, as Ohio is a one-party consent state, i.e., the law permits a patient to legally tape his/her conversations without obtaining prior approval from the doctor.3

There are clear advantages to having a permanent record of a doctor’s professional opinion. The patient can review the information after the visit for a better understanding or for recall purposes, even sharing the information with family members, caregivers, or others, especially where there is a lack of clarity on instructions.4 In the area of informed consent, this is particularly useful for a reminder of medication side effects and potential complications of proposed surgery.

However, many doctors believe that recordings may be disruptive or prove inhibitory to free and open discussions, and they are concerned about their potential use should litigation arises.

Risk managers and malpractice carriers are divided in their views. For example, it has been stated that, “at the Barrow Neurological Institute, in Phoenix, Arizona, where patients are routinely offered video recordings of their visits, clinicians who participate in these recordings receive a 10% reduction in the cost of their medical defense and $1 million extra liability coverage” (P.J. Barr, unpublished data, 2017, as cited in reference 1). Other carriers are not as supportive, discouraging their insureds from allowing recordings to be made.

In the majority of jurisdictions, recordings are legal if consented to by one of the parties. This means that recordings by the patient with/without consent from or with/without knowledge of the doctor are fully legitimate. It also means that the recordings will be admissible into evidence in a courtroom, unless the information is privileged (protected from discovery) or is otherwise irrelevant or unreliable.

On the other hand, in states requiring all-party consent, such recordings are illegal absent across-the-board consent, and they will be inadmissible into evidence. This cardinal difference in state law raises vital implications for both plaintiff and defendant in litigation, because the recordings may contain incriminating or exculpatory information.

Recordings of conversations in the doctor’s office are by no means rare. A survey in the United Kingdom revealed that 15% of the public had secretly recorded a clinic visit, and 11% were aware of someone else doing the same.5 The concerned physician could proactively prohibit all office recordings by posting a “no recording” sign in the waiting room in the name of confidentiality and privacy. And should a physician discover that a patient is covertly recording, risk managers have suggested terminating the visit with a warning that a repeat attempt will result in discharge.

Like it or not, recordings are here to stay, and the omnipresence of modern communications devices such as smartphones, tablets, etc., is likely to increase the prevalence of recordings. A practical approach for practicing physicians is to familiarize themselves with the law in the individual state in which they practice and to improve their communication skills irrespective of whether or not there is a recording.

They may wish to consider the view attributed to Richard Boothman, JD, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System: “Recording should cause any caregiver to mind their professionalism and be disciplined in their remarks to their patients. … I believe it can be a very powerful tool to cement the patient/physician relationship and the patient’s understanding of the clinical messages and information. Physicians are significantly benefited by an informed patient.”6

References

1. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8;318(6):513-4.

2. Smith v. Cleveland Clinic, 197 Ohio App.3d 524, 2011.

3. Ohio Revised Code 2933.52.

4. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1615-6.

5. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug 11;5(8):e008566.

6. “Your office is being recorded.” Medscape, April 3, 2018.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

ESBL-resistant bacteria spread in hospital despite strict contact precautions

MADRID – even when staff employed an active surveillance screening protocol to identify every carrier at admission.

The failure of precautions may have root in two thorny issues, said Friederike Maechler, MD, who presented the data at the the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.