User login

Woman with Abdominal Pain Following Severe Car Crash

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a comminuted fracture at the midshaft of the tibia. In addition, there is a comminuted fracture of the proximal tibial metaphysis extending to the tibia plateau. Also noted is a comminuted fracture of the distal femur metaphysis extending to the intercondylar notch

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a comminuted fracture at the midshaft of the tibia. In addition, there is a comminuted fracture of the proximal tibial metaphysis extending to the tibia plateau. Also noted is a comminuted fracture of the distal femur metaphysis extending to the intercondylar notch

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a comminuted fracture at the midshaft of the tibia. In addition, there is a comminuted fracture of the proximal tibial metaphysis extending to the tibia plateau. Also noted is a comminuted fracture of the distal femur metaphysis extending to the intercondylar notch

A 43-year-old woman is airlifted to your facility from an outlying area following a severe motor vehicle collision. Details are unclear, but there were known fatalities at the scene. Her primary complaints are abdominal pain and noted deformities of the lower extremities, according to the transporting medical personnel. On arrival, she is noted to be semi-arousable and is moving distal portions of all four extremities. Her heart rate is 150 beats/min, with a blood pressure of 80/40 mm Hg. She responds to initial fluid and volume resuscitation. She has no pertinent medical history. Her response to the fluid resuscitation is sufficient to stabilize her for transport to the CT scanner for additional imaging. Prior to the transfer, though, a portable radiograph of her right tibia is obtained. What is your impression?

Patient's Condition is "All Thumbs"

ANSWER

The correct answer is habit-tic deformity (choice “d”), a relatively common self-inflicted condition relegated to thumbnails.

Chronic candidal paronychia (choice “a”) has certain similarities to habit-tic deformity (eg, loss of connection between cuticle and nail plate) but it also has an inflammatory aspect that manifests as chronic focal tenderness, redness, and swelling of the adjacent perionychial tissue.

The clinical picture and total lack of response to antifungal medications made a diagnosis of onychomycosis (choice “b”) quite unlikely. Canaliformis defect (choice “c”) involves a central longitudinal linear concave defect in the affected nails and is therefore incorrect.

DISCUSSION

Fungal infection in fingernails, while not unknown, is about 18 times less likely than the same condition in toenails. Nonetheless, onychomycosis continues to be vastly overdiagnosed by clinicians whose differential diagnoses are lacking.

Habit-tic deformity is a perfect example of this phenomenon. Also called onychotillomania, habit-tic is actually caused by chronic picking of the cuticles; over time, this results in the creation of transverse parallel grooves that persist for the 4 to 4.5 months it takes for the nail plate to grow out. It rarely occurs on fingernails other than the thumbnails. Habit-tic, as in this case, can also involve modest traumatically induced subungual bleeding, seen as brownish discoloration.

Many patients have good insight into their causative role, but just as many pick their cuticle unconsciously. The obvious solution is to stop the offending behavior and/or put a barrier on the nails, but neither measure has met with much success. One potential remedy (see “Suggested Reading”) is to fill the cuticular sulcus with protective acrylate glue and let it dry. This, in effect, creates a barrier while the cuticle heals and reattaches to the nail plate (although the potential for contact dermatitis may become a concern). Hypnosis and other behavior modification have also been tried.

For many patients, just knowing what they don’t have is quite helpful. For providers, it is helpful to develop a differential for conditions that involve nail dystrophy, including the incorrect answer choices offered here. If fungal infection were truly a possibility, the best way to confirm that diagnosis would be to send a nail clipping to pathology, either for sectioning and identification of fungal elements or an actual fungal culture.

SUGGESTED READING

Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(11):1222-1223.

ANSWER

The correct answer is habit-tic deformity (choice “d”), a relatively common self-inflicted condition relegated to thumbnails.

Chronic candidal paronychia (choice “a”) has certain similarities to habit-tic deformity (eg, loss of connection between cuticle and nail plate) but it also has an inflammatory aspect that manifests as chronic focal tenderness, redness, and swelling of the adjacent perionychial tissue.

The clinical picture and total lack of response to antifungal medications made a diagnosis of onychomycosis (choice “b”) quite unlikely. Canaliformis defect (choice “c”) involves a central longitudinal linear concave defect in the affected nails and is therefore incorrect.

DISCUSSION

Fungal infection in fingernails, while not unknown, is about 18 times less likely than the same condition in toenails. Nonetheless, onychomycosis continues to be vastly overdiagnosed by clinicians whose differential diagnoses are lacking.

Habit-tic deformity is a perfect example of this phenomenon. Also called onychotillomania, habit-tic is actually caused by chronic picking of the cuticles; over time, this results in the creation of transverse parallel grooves that persist for the 4 to 4.5 months it takes for the nail plate to grow out. It rarely occurs on fingernails other than the thumbnails. Habit-tic, as in this case, can also involve modest traumatically induced subungual bleeding, seen as brownish discoloration.

Many patients have good insight into their causative role, but just as many pick their cuticle unconsciously. The obvious solution is to stop the offending behavior and/or put a barrier on the nails, but neither measure has met with much success. One potential remedy (see “Suggested Reading”) is to fill the cuticular sulcus with protective acrylate glue and let it dry. This, in effect, creates a barrier while the cuticle heals and reattaches to the nail plate (although the potential for contact dermatitis may become a concern). Hypnosis and other behavior modification have also been tried.

For many patients, just knowing what they don’t have is quite helpful. For providers, it is helpful to develop a differential for conditions that involve nail dystrophy, including the incorrect answer choices offered here. If fungal infection were truly a possibility, the best way to confirm that diagnosis would be to send a nail clipping to pathology, either for sectioning and identification of fungal elements or an actual fungal culture.

SUGGESTED READING

Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(11):1222-1223.

ANSWER

The correct answer is habit-tic deformity (choice “d”), a relatively common self-inflicted condition relegated to thumbnails.

Chronic candidal paronychia (choice “a”) has certain similarities to habit-tic deformity (eg, loss of connection between cuticle and nail plate) but it also has an inflammatory aspect that manifests as chronic focal tenderness, redness, and swelling of the adjacent perionychial tissue.

The clinical picture and total lack of response to antifungal medications made a diagnosis of onychomycosis (choice “b”) quite unlikely. Canaliformis defect (choice “c”) involves a central longitudinal linear concave defect in the affected nails and is therefore incorrect.

DISCUSSION

Fungal infection in fingernails, while not unknown, is about 18 times less likely than the same condition in toenails. Nonetheless, onychomycosis continues to be vastly overdiagnosed by clinicians whose differential diagnoses are lacking.

Habit-tic deformity is a perfect example of this phenomenon. Also called onychotillomania, habit-tic is actually caused by chronic picking of the cuticles; over time, this results in the creation of transverse parallel grooves that persist for the 4 to 4.5 months it takes for the nail plate to grow out. It rarely occurs on fingernails other than the thumbnails. Habit-tic, as in this case, can also involve modest traumatically induced subungual bleeding, seen as brownish discoloration.

Many patients have good insight into their causative role, but just as many pick their cuticle unconsciously. The obvious solution is to stop the offending behavior and/or put a barrier on the nails, but neither measure has met with much success. One potential remedy (see “Suggested Reading”) is to fill the cuticular sulcus with protective acrylate glue and let it dry. This, in effect, creates a barrier while the cuticle heals and reattaches to the nail plate (although the potential for contact dermatitis may become a concern). Hypnosis and other behavior modification have also been tried.

For many patients, just knowing what they don’t have is quite helpful. For providers, it is helpful to develop a differential for conditions that involve nail dystrophy, including the incorrect answer choices offered here. If fungal infection were truly a possibility, the best way to confirm that diagnosis would be to send a nail clipping to pathology, either for sectioning and identification of fungal elements or an actual fungal culture.

SUGGESTED READING

Ring DS. Inexpensive solution for habit-tic deformity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(11):1222-1223.

A 56-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” that has affected both thumbnails for at least 20 years. While the condition produces no symptoms, it has nonetheless been a source of constant embarrassment to him. He denies having any such problems with his toenails. Furthermore, he says the problem has persisted despite the use of numerous topical and oral medications, including topical miconazole, clotrimazole, oil of eucalyptus, bleach, and the oral antifungals terbinafine and griseofulvin. None of these has had any effect. Additional history taking reveals that the patient is highly allergy-prone; he had seasonal allergies and asthma as a child. He also has a history of extremely dry and sensitive skin. On examination, the problems with the patient’s thumbnails are obvious, with traumatic absence of cuticles, widening and deepening of the cuticular sulcus, and deep parallel transverse lines involving the entire visible nail plates. Scattered subungual patches of brown discoloration are also seen beneath the lines. None of the patient’s other nails are abnormal in any way.

Atrial Flutter Follow-up

ANSWER

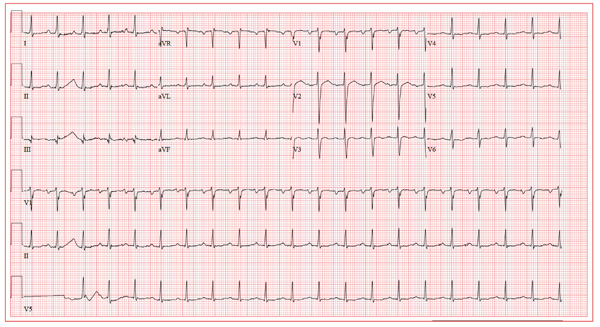

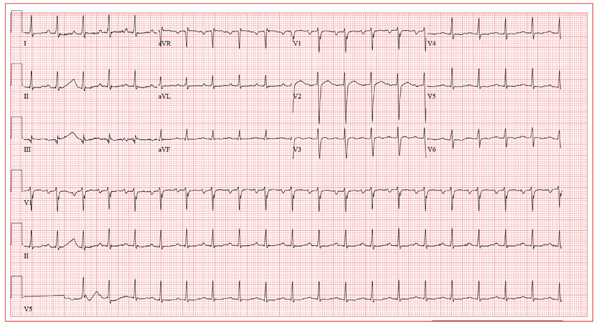

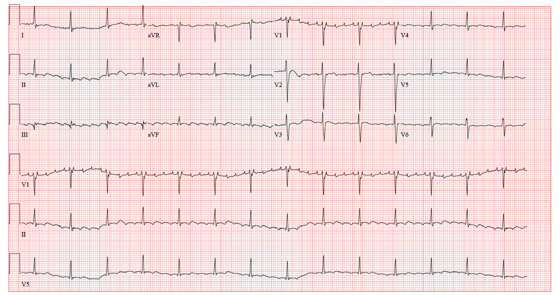

The ECG reveals sinus tachycardia with possible left atrial enlargement and a nonspecific T-wave abnormality. Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by a sinus rate > 100 beats/min, with one corresponding QRS complex for each P wave.

The criteria for left atrial enlargement include a P-wave duration ≥ 0.12 s in lead II, notched P waves in the limb leads, and a biphasic P wave in lead V1, with the terminal portion of the P wave (corresponding to the left atrium) being negative with a duration of ≥ 0.04 s and a depth ≥ 1 mm. (The echocardiogram shows a left atrial measurement at the upper limits of normal.)

Nonspecific T-wave changes are again seen in the precordial leads. Based on these findings, there is no structural disease to suggest a cause for this patient’s episode of atrial flutter.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals sinus tachycardia with possible left atrial enlargement and a nonspecific T-wave abnormality. Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by a sinus rate > 100 beats/min, with one corresponding QRS complex for each P wave.

The criteria for left atrial enlargement include a P-wave duration ≥ 0.12 s in lead II, notched P waves in the limb leads, and a biphasic P wave in lead V1, with the terminal portion of the P wave (corresponding to the left atrium) being negative with a duration of ≥ 0.04 s and a depth ≥ 1 mm. (The echocardiogram shows a left atrial measurement at the upper limits of normal.)

Nonspecific T-wave changes are again seen in the precordial leads. Based on these findings, there is no structural disease to suggest a cause for this patient’s episode of atrial flutter.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals sinus tachycardia with possible left atrial enlargement and a nonspecific T-wave abnormality. Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by a sinus rate > 100 beats/min, with one corresponding QRS complex for each P wave.

The criteria for left atrial enlargement include a P-wave duration ≥ 0.12 s in lead II, notched P waves in the limb leads, and a biphasic P wave in lead V1, with the terminal portion of the P wave (corresponding to the left atrium) being negative with a duration of ≥ 0.04 s and a depth ≥ 1 mm. (The echocardiogram shows a left atrial measurement at the upper limits of normal.)

Nonspecific T-wave changes are again seen in the precordial leads. Based on these findings, there is no structural disease to suggest a cause for this patient’s episode of atrial flutter.

A 39-year-old business professional returns to your clinic for follow-up one month after a synchronized cardioversion to treat abrupt-onset atrial flutter (see January 2012 ECG Challenge). He is slightly short of breath, he says, because he ran up six flights of stairs to see you in clinic after undergoing an echocardiogram. Briefly, he developed atrial flutter presumably as a result of consuming a large quantity of caffeinated coffee along with several energy drinks containing taurine. He has been under a significant amount of stress at work for the past six months, working on a project that he predicted would play a major role in his career. The deadline has come and gone, and his business transaction was a success. He has taken your advice to avoid energy drinks, consume coffee in moderation, stop smoking, get plenty of rest, and exercise. His affect is much improved. He is pleasant, jovial, and relieved that he has had no subsequent episodes of atrial flutter. His medical history is remarkable for that single episode of atrial flutter, as well as childhood cases of chickenpox and mumps. He is taking ibuprofen for a sore knee as a result of “too much basketball.” He has no known drug allergies. Following his cardioversion, his alcohol consumption decreased from two cocktails in the evening and a 12-pack of beer on the weekends to an occasional cocktail during the week and two to four beers on the weekends. He denies illicit drug use. The review of systems is unremarkable. The physical exam reveals a thin, well-developed man in no distress. His weight is 170 lb and his height, 74”. Vital statistics include a blood pressure of 128/72 mm Hg; pulse, 110 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; temperature, 98.4°F; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air. The chest is clear to auscultation in all lung fields. There are no murmurs, rubs, clicks, or extra heart sounds. The abdomen is soft and nontender. The pulses are equal and bounding bilaterally. The neurologic exam is benign. The echocardiogram performed earlier shows a left ventricular ejection fraction of 68%, normal left and right ventricular volumes and function, normal valvular function, and a left atrial measurement of 3.8 cm (normal, 1.6 to 4.0 cm). An ECG performed just before you entered the exam room reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 122 beats/min; PR interval, 184 ms; QRS duration, 90 ms; QT/QTc interval, 282/401 ms; P axis, 24°; R axis, 28°; and T axis, –45°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Are Energy Drinks Causing This Man's Shortness of Breath?

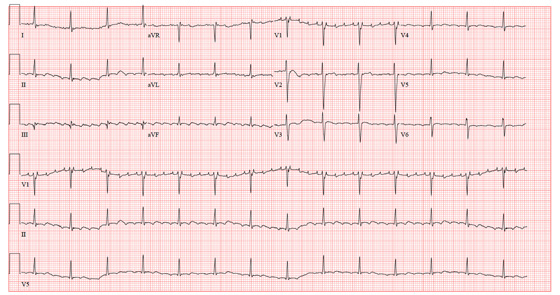

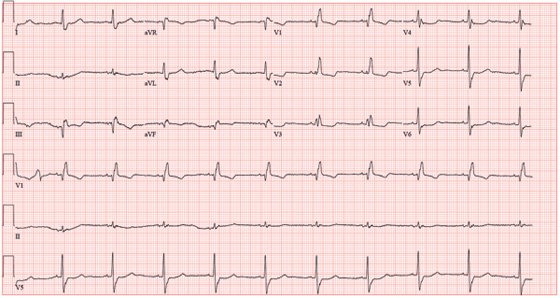

ANSWER

The ECG reveals atrial flutter with a nonspecific T-wave abnormality. The atrial rate is 300 beats/min. The ventricular rate is 84 beats/min; hence the atrial flutter occurs in a 4:1 pattern. (This is best seen in lead V1, where one of the atrial beats is “hidden” in the QRS complex.) The PR interval of 208 ms on the computerized analysis is misleading and illustrates the risk of relying on the computer for a diagnosis. The nonspecific T-wave abnormalities are best seen in leads V2 and V3 and are of no consequence.

While there are no definitive studies that prove that combining energy drinks containing taurine with beverages containing caffeine increases the risk for arrhythmias, there are several anecdotal case reports. In addition to consumption of taurine- and caffeine-containing beverages, this patient is under a significant amount of stress, producing a large catecholaminergic response.

The patient has no prior cardiac history of arrhythmias and no prior cardiac workup. He underwent synchronized cardioversion to restore normal sinus rhythm and was scheduled for an outpatient workup for structural heart disease.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals atrial flutter with a nonspecific T-wave abnormality. The atrial rate is 300 beats/min. The ventricular rate is 84 beats/min; hence the atrial flutter occurs in a 4:1 pattern. (This is best seen in lead V1, where one of the atrial beats is “hidden” in the QRS complex.) The PR interval of 208 ms on the computerized analysis is misleading and illustrates the risk of relying on the computer for a diagnosis. The nonspecific T-wave abnormalities are best seen in leads V2 and V3 and are of no consequence.

While there are no definitive studies that prove that combining energy drinks containing taurine with beverages containing caffeine increases the risk for arrhythmias, there are several anecdotal case reports. In addition to consumption of taurine- and caffeine-containing beverages, this patient is under a significant amount of stress, producing a large catecholaminergic response.

The patient has no prior cardiac history of arrhythmias and no prior cardiac workup. He underwent synchronized cardioversion to restore normal sinus rhythm and was scheduled for an outpatient workup for structural heart disease.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals atrial flutter with a nonspecific T-wave abnormality. The atrial rate is 300 beats/min. The ventricular rate is 84 beats/min; hence the atrial flutter occurs in a 4:1 pattern. (This is best seen in lead V1, where one of the atrial beats is “hidden” in the QRS complex.) The PR interval of 208 ms on the computerized analysis is misleading and illustrates the risk of relying on the computer for a diagnosis. The nonspecific T-wave abnormalities are best seen in leads V2 and V3 and are of no consequence.

While there are no definitive studies that prove that combining energy drinks containing taurine with beverages containing caffeine increases the risk for arrhythmias, there are several anecdotal case reports. In addition to consumption of taurine- and caffeine-containing beverages, this patient is under a significant amount of stress, producing a large catecholaminergic response.

The patient has no prior cardiac history of arrhythmias and no prior cardiac workup. He underwent synchronized cardioversion to restore normal sinus rhythm and was scheduled for an outpatient workup for structural heart disease.

A business professional, age 39, presents with shortness of breath that abruptly began two hours ago. He states he has been under a significant amount of stress at work during the past six months. He is approaching a deadline on a very important contract, which he says will “make or break” his career. As a result, he has been working long hours and often consumes eight to 10 cups of coffee as well as three to five energy drinks per day. After getting only three hours of sleep last night, he had two cups of coffee with a “two–energy-drink chaser.” About one hour after his last energy drink, he felt several palpitations and abruptly became short of breath. There is no history of pulmonary or cardiac illness. The patient’s medical history is unremarkable, with the exception of childhood cases of chickenpox and mumps. He has never had a surgical procedure. He takes ibuprofen on occasion after playing sports and has no known drug allergies. During college, he smoked one pack of cigarettes per day, ceasing at graduation. In response to work-related stress, he has started smoking again and is up to half a pack per day. His alcohol consumption consists of two cocktails in the evening and a 12-pack of beer on the weekends. He denies illicit drug use. The review of systems is remarkable for heartburn, bloating, and frequent indigestion. He denies nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation. The physical examination reveals a well-developed, anxious male in mild distress. His weight is 174 lb and his height is 74 in. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 90/58 mm Hg; pulse, 88 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98°F. His O2 saturation is 99% on room air. The HEENT exam is normal. There is no thyromegaly. The mucous membranes are pink and moist. The chest is clear to auscultation in all lung fields with excellent diaphragmatic excursion. The pulse is regular. There are no murmurs, rubs, clicks, or extra heart sounds. The abdomen is soft and nontender. The liver and spleen are not palpable. The pulses are equal and strong bilaterally. The neurologic exam is unremarkable. A chest x-ray, blood chemistry, complete blood count, and electrocardiogram are ordered. You are handed an ECG tracing that reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 84 beats/min; PR interval, 208 ms; QRS duration, 102 ms; QT/QTc interval, 358/423 ms; R axis, 20°; and T axis, 29°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Pruritic Rash on Both Soles

ANSWER

The correct answer is a form of psoriasis (choice “a”)—in this case, pustular psoriasis, which is seen mostly on hands and feet.

As in many such cases, biopsy was necessary; it successfully ruled out several items in the differential, in particular contact dermatitis (choice “b”). Ringworm and athlete’s foot (choice “c” and “d,” respectively) are archaic lay terms for fungal infection, which was not only ruled out by its absence in the biopsy specimen, but was unlikely given the lack of response to multiple antifungal medications.

DISCUSSION

Palmoplantar pustulosis is the term most often used to describe a fairly common form of psoriasis typified by this case. Many patients are genetically predisposed to psoriasis, but they may require a trigger to set it off, such as strep infection or occasionally, medication. Notable among the latter are the b-blockers and lithium. Stress is often involved as well.

The bilateral symmetrical involvement of both insteps is highly suggestive of this diagnosis, which often also affects either peripheral or central palms. A secondary form of neurodermatitis (itch–scratch–itch cycle) can follow, complicating the picture and perpetuating the problem.

Biopsy was deemed necessary to clarify the diagnosis and gain confidence in the therapeutic process, which can be difficult with this problem.

The patient was urged to consult her psychiatrist about finding a substitute for her lithium. At the time of this description, she is currently applying clobetasol cream under occlusion for three weeks, at the conclusion of which she will be re-evaluated. Many such patients go on to require the use of other medications, such as methotrexate or acetretin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is a form of psoriasis (choice “a”)—in this case, pustular psoriasis, which is seen mostly on hands and feet.

As in many such cases, biopsy was necessary; it successfully ruled out several items in the differential, in particular contact dermatitis (choice “b”). Ringworm and athlete’s foot (choice “c” and “d,” respectively) are archaic lay terms for fungal infection, which was not only ruled out by its absence in the biopsy specimen, but was unlikely given the lack of response to multiple antifungal medications.

DISCUSSION

Palmoplantar pustulosis is the term most often used to describe a fairly common form of psoriasis typified by this case. Many patients are genetically predisposed to psoriasis, but they may require a trigger to set it off, such as strep infection or occasionally, medication. Notable among the latter are the b-blockers and lithium. Stress is often involved as well.

The bilateral symmetrical involvement of both insteps is highly suggestive of this diagnosis, which often also affects either peripheral or central palms. A secondary form of neurodermatitis (itch–scratch–itch cycle) can follow, complicating the picture and perpetuating the problem.

Biopsy was deemed necessary to clarify the diagnosis and gain confidence in the therapeutic process, which can be difficult with this problem.

The patient was urged to consult her psychiatrist about finding a substitute for her lithium. At the time of this description, she is currently applying clobetasol cream under occlusion for three weeks, at the conclusion of which she will be re-evaluated. Many such patients go on to require the use of other medications, such as methotrexate or acetretin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is a form of psoriasis (choice “a”)—in this case, pustular psoriasis, which is seen mostly on hands and feet.

As in many such cases, biopsy was necessary; it successfully ruled out several items in the differential, in particular contact dermatitis (choice “b”). Ringworm and athlete’s foot (choice “c” and “d,” respectively) are archaic lay terms for fungal infection, which was not only ruled out by its absence in the biopsy specimen, but was unlikely given the lack of response to multiple antifungal medications.

DISCUSSION

Palmoplantar pustulosis is the term most often used to describe a fairly common form of psoriasis typified by this case. Many patients are genetically predisposed to psoriasis, but they may require a trigger to set it off, such as strep infection or occasionally, medication. Notable among the latter are the b-blockers and lithium. Stress is often involved as well.

The bilateral symmetrical involvement of both insteps is highly suggestive of this diagnosis, which often also affects either peripheral or central palms. A secondary form of neurodermatitis (itch–scratch–itch cycle) can follow, complicating the picture and perpetuating the problem.

Biopsy was deemed necessary to clarify the diagnosis and gain confidence in the therapeutic process, which can be difficult with this problem.

The patient was urged to consult her psychiatrist about finding a substitute for her lithium. At the time of this description, she is currently applying clobetasol cream under occlusion for three weeks, at the conclusion of which she will be re-evaluated. Many such patients go on to require the use of other medications, such as methotrexate or acetretin.

A 62-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a pruritic rash that has been present on both soles for more than two years. Attempts to treat it with different OTC topical creams (eg, clotrimazole, miconazole), prescription antifungal creams (oxiconazole and nystatin), and even a combination cream (clotrimazole/betamethasone) have been unsuccessful. The last eased her symptoms but yielded no lasting relief. Her primary care provider had prescribed a month-long course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d). When that did not help, a two-week course of oral antibiotic (cephalexin 500 mg qid) was tried. Neither had any salutary effect, so the patient was referred first to a podiatrist, who quickly sent her to dermatology. Complaining bitterly of itching on these areas, she explains that the condition began with tiny pustules, then tiny blisters that gradually covered both insteps. She denies having any such rash elsewhere (eg, on elbows or knees or in the scalp). There is no known family history of skin problems, and no personal history of arthritis. Just prior to the onset of this problem, she had received a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, which forced her to leave her job and start taking lithium. Although the lithium has helped, she remains unable to work. On examination, the skin of both insteps is covered with discrete and confluent papules and tiny pustules on an erythematous and hyperpigmented (brown), sharply demarcated, and highly symmetrical base. As the patient said, her skin, nails, and scalp elsewhere are free of any such lesions. Given her Hispanic ancestry, her skin is phototype IV/VI. Punch biopsy is performed and shows almost no spongiosis or edema, relatively tortuous capillary loops, and collections of neutrophils above foci of parakeratosis. Special stain for fungal elements fails to identify any sign of that family of organisms.

Man Run Over By Vehicle

ANSWER

The radiograph shows some deformity within the mid-to-distal diaphysis of both the radius and ulna; however, no acute fracture is seen. This is most likely related to remote trauma.

Of note, closer to the elbow, there are some small avulsion fractures near the area of the lateral epicondyle. The patient was treated with a posterior splint and referred to orthopedics.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows some deformity within the mid-to-distal diaphysis of both the radius and ulna; however, no acute fracture is seen. This is most likely related to remote trauma.

Of note, closer to the elbow, there are some small avulsion fractures near the area of the lateral epicondyle. The patient was treated with a posterior splint and referred to orthopedics.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows some deformity within the mid-to-distal diaphysis of both the radius and ulna; however, no acute fracture is seen. This is most likely related to remote trauma.

Of note, closer to the elbow, there are some small avulsion fractures near the area of the lateral epicondyle. The patient was treated with a posterior splint and referred to orthopedics.

After accidentally being run over by a vehicle, a 54-year-old man presents to the emergency department for evaluation of pain in his elbow and left arm. He was leaning down behind the vehicle and was not seen when the driver backed up. The patient states that one of the tires went over his left shoulder and arm. Primary complaint is pain and decreased range of motion. He denies any significant medical history, except for medication-controlled hypertension and gallbladder surgery. His vital signs are stable. Exammination of the left arm demonstrates some abrasions and contusions over the shoulder and forearm, as well as some swelling over the elbow. The patient has good color, distal pulses, and sensation. There is localized tenderness over the elbow and midforearm. Flexion of the elbow is somewhat limited secondary to pain. Radiograph of the forearm is obtained and shown. What is your impression?

Man with Debilitating Back Pain

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates generalized degenerative changes. Of note are fairly significant destructive changes in the endplate at the L3-4 level. Such changes are generally consistent with osteomyelitis and diskitis.

On further questioning, the patient reported that when he was admitted previously, he was told that he had an “infection in his back” and was treated with IV antibiotics. This patient was again admitted for additional workup and treatment.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates generalized degenerative changes. Of note are fairly significant destructive changes in the endplate at the L3-4 level. Such changes are generally consistent with osteomyelitis and diskitis.

On further questioning, the patient reported that when he was admitted previously, he was told that he had an “infection in his back” and was treated with IV antibiotics. This patient was again admitted for additional workup and treatment.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates generalized degenerative changes. Of note are fairly significant destructive changes in the endplate at the L3-4 level. Such changes are generally consistent with osteomyelitis and diskitis.

On further questioning, the patient reported that when he was admitted previously, he was told that he had an “infection in his back” and was treated with IV antibiotics. This patient was again admitted for additional workup and treatment.

A 54-year-old man presents with a complaint of a two-week history of severe low back pain. He denies any injury or trauma. The pain is so severe that it limits his ability to walk. He states he had similar episodes earlier this year, some of which required him to be admitted to the hospital. His medical history is significant for hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. He admits to recently having subjective fever and chills, as well as some nausea. Physical exam shows a deconditioned male who is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. He is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 92/57 mm Hg, a heart rate of 97 beats/min, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. He has mild tenderness to his lumbosacral area; no deformity, step-off, or crepitus is appreciated. He does have decreased range of motion in his lower extremities, although this may be a consequence of his back pain. While trying to pull up his previous medical records, you order some basic labwork and lumbar spine radiographs. Lateral lumbar spine radiograph is shown; what is your impression?

Ederly Woman Experiences Chest Pain While Knitting

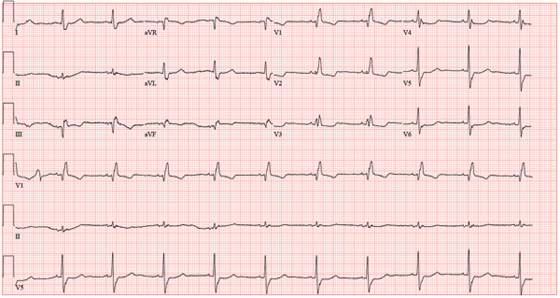

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm with a short PR interval, right bundle branch block, and an inferior myocardial infarction. The PR interval may vary based on age and heart rate, but is generally accepted as ranging between 120 and 200 ms.

Criteria for a right bundle branch include a QRS complex > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. An inferior wall myocardial infarction is evidenced by significant Q waves and T-wave inversions in the inferior leads II, III, and aVF.

This case illustrates that an ECG may be of little value in the setting of an ascending aortic dissection. This patient succumbed to rupture of her aortic dissection shortly after admission.

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm with a short PR interval, right bundle branch block, and an inferior myocardial infarction. The PR interval may vary based on age and heart rate, but is generally accepted as ranging between 120 and 200 ms.

Criteria for a right bundle branch include a QRS complex > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. An inferior wall myocardial infarction is evidenced by significant Q waves and T-wave inversions in the inferior leads II, III, and aVF.

This case illustrates that an ECG may be of little value in the setting of an ascending aortic dissection. This patient succumbed to rupture of her aortic dissection shortly after admission.

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm with a short PR interval, right bundle branch block, and an inferior myocardial infarction. The PR interval may vary based on age and heart rate, but is generally accepted as ranging between 120 and 200 ms.

Criteria for a right bundle branch include a QRS complex > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. An inferior wall myocardial infarction is evidenced by significant Q waves and T-wave inversions in the inferior leads II, III, and aVF.

This case illustrates that an ECG may be of little value in the setting of an ascending aortic dissection. This patient succumbed to rupture of her aortic dissection shortly after admission.

An 84-year-old woman presents with left-sided chest pain radiating to the back and neck. The pain began about four hours ago, while she was knitting. She describes it as a “dull ache” that quickly progressed to a “sharp, sticking” pain on a scale of 8/10. She has never experienced pain like this before. She denies nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, headache, palpitations, orthopnea, or dyspnea on exertion. Her medical history is remarkable for Crohn’s disease, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and myxomatous mitral valve disease. Surgical history is remarkable for a myocardial infarction 10 years ago, two separate catheter ablations for atrial fibrillation (successful on the second attempt), a mitral valve replacement (bioprosthetic) one year ago, and a hysterectomy/oophorectomy in the remote past. The patient has no known drug allergies. Her medications include atenolol, aspirin, furosemide, estradiol, ferrous sulfate, mesalamine, omeprazole, warfarin, and lisinopril. She is a retired teacher, married, who has never smoked and rarely drinks alcohol. Her family history is remarkable for heart disease in her father and diabetes in her mother. The review of systems is negative, with the exception of frequent episodes of nonbloody diarrhea and abdominal pain associated with her Crohn’s disease. Physical exam reveals a blood pressure of 208/120 mm Hg; pulse, 60 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min-1; temperature, 97.8°F; and O2 saturation, 96% on 2L oxygen. She appears anxious, restless, and unable to find a comfortable position. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distention to the angle of the jaw, a regular heart rate with a harsh III/VI systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border, and a soft II/VI diastolic murmur radiating to the apex. Peripheral pulses are brisk and equal bilaterally. There are no neurologic deficits. Laboratory data include a normal complete blood count, an INR of 2.2, normal blood chemistries, normal liver function studies, and negative troponin levels. CT reveals a 5.5-cm dissection of the ascending aorta. An ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 61 beats/min; PR interval, 108 ms; QRS duration, 132 ms; QT/QTc interval, 478/481 ms; P axis, 19°; R axis, 0°; and T axis, –13°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Is A Common Illness The Cause of This Man's Rash?

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC; choice “c”), one of the so-called “reactive erythemas,” which have several potential causes including streptococcal infections. The clinical picture and classic histologic pattern seen on biopsy effectively ruled out the other items in the differential diagnosis.

Dermatophytosis (choice “a”), a superficial fungal infection, would likely have demonstrated KOH positivity at its scaly leading edge.

Subacute cutaneous lupus (choice “b”) has many morphologic presentations, including annular scaly lesions with clearing centers, but definite signs (interface dermatitis, increased mucin or apoptosis) would have been seen on biopsy.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “d”) is one of a handful of malignancies that can present as a “rash,” but the biopsy effectively ruled it out.

DISCUSSION

First described by Darier in 1916, EAC exhibits a pathognomic feature called “trailing scale.” With dermatophytosis, for example, the bulk of the scaling is found at the leading edge of the lesion. By contrast, with EAC, the scaling lags behind the leading erythematous border and is thus said to “trail” the edge. Since EAC so closely resembles dermatophytosis, this feature serves to distinguish the two.

EAC lesions can be large, appear in multiples, and spare only palms and soles.

EAC is most often idiopathic. However, there are many reported triggers, including drugs (eg, gold, antimalarials, penicillin, and aspirin), infections (such as strep and dermatophytosis), and malignancies.

A brisk inflammatory tinea can set it off, complicating the clinical picture by presenting with two different types of annular lesions. Treating the fungal infection or other trigger effectively cures the EAC. In such cases, a careful history will show which rash came first.

When the cause is not immediately obvious, potential triggers that should be investigated include: occult malignancy, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and pregnancy. Examination of skin distant from the obviously affected areas is often necessary, with special attention to the feet, groin, and scalp. Laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, liver function tests, rapid plasma reagin test, urinalysis, and chest x-ray for completeness.

EAC is treated, as mentioned earlier, by finding and eliminating the underlying cause. That often proves impossible, so steroid therapy (oral or topical) is often employed with some effect (though it will not prevent recurrences of the condition). Empiric use of oral antibiotics has produced mixed results. The condition can persist for years but is seldom significantly symptomatic.

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC; choice “c”), one of the so-called “reactive erythemas,” which have several potential causes including streptococcal infections. The clinical picture and classic histologic pattern seen on biopsy effectively ruled out the other items in the differential diagnosis.

Dermatophytosis (choice “a”), a superficial fungal infection, would likely have demonstrated KOH positivity at its scaly leading edge.

Subacute cutaneous lupus (choice “b”) has many morphologic presentations, including annular scaly lesions with clearing centers, but definite signs (interface dermatitis, increased mucin or apoptosis) would have been seen on biopsy.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “d”) is one of a handful of malignancies that can present as a “rash,” but the biopsy effectively ruled it out.

DISCUSSION

First described by Darier in 1916, EAC exhibits a pathognomic feature called “trailing scale.” With dermatophytosis, for example, the bulk of the scaling is found at the leading edge of the lesion. By contrast, with EAC, the scaling lags behind the leading erythematous border and is thus said to “trail” the edge. Since EAC so closely resembles dermatophytosis, this feature serves to distinguish the two.

EAC lesions can be large, appear in multiples, and spare only palms and soles.

EAC is most often idiopathic. However, there are many reported triggers, including drugs (eg, gold, antimalarials, penicillin, and aspirin), infections (such as strep and dermatophytosis), and malignancies.

A brisk inflammatory tinea can set it off, complicating the clinical picture by presenting with two different types of annular lesions. Treating the fungal infection or other trigger effectively cures the EAC. In such cases, a careful history will show which rash came first.

When the cause is not immediately obvious, potential triggers that should be investigated include: occult malignancy, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and pregnancy. Examination of skin distant from the obviously affected areas is often necessary, with special attention to the feet, groin, and scalp. Laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, liver function tests, rapid plasma reagin test, urinalysis, and chest x-ray for completeness.

EAC is treated, as mentioned earlier, by finding and eliminating the underlying cause. That often proves impossible, so steroid therapy (oral or topical) is often employed with some effect (though it will not prevent recurrences of the condition). Empiric use of oral antibiotics has produced mixed results. The condition can persist for years but is seldom significantly symptomatic.

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC; choice “c”), one of the so-called “reactive erythemas,” which have several potential causes including streptococcal infections. The clinical picture and classic histologic pattern seen on biopsy effectively ruled out the other items in the differential diagnosis.

Dermatophytosis (choice “a”), a superficial fungal infection, would likely have demonstrated KOH positivity at its scaly leading edge.

Subacute cutaneous lupus (choice “b”) has many morphologic presentations, including annular scaly lesions with clearing centers, but definite signs (interface dermatitis, increased mucin or apoptosis) would have been seen on biopsy.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “d”) is one of a handful of malignancies that can present as a “rash,” but the biopsy effectively ruled it out.

DISCUSSION

First described by Darier in 1916, EAC exhibits a pathognomic feature called “trailing scale.” With dermatophytosis, for example, the bulk of the scaling is found at the leading edge of the lesion. By contrast, with EAC, the scaling lags behind the leading erythematous border and is thus said to “trail” the edge. Since EAC so closely resembles dermatophytosis, this feature serves to distinguish the two.

EAC lesions can be large, appear in multiples, and spare only palms and soles.

EAC is most often idiopathic. However, there are many reported triggers, including drugs (eg, gold, antimalarials, penicillin, and aspirin), infections (such as strep and dermatophytosis), and malignancies.

A brisk inflammatory tinea can set it off, complicating the clinical picture by presenting with two different types of annular lesions. Treating the fungal infection or other trigger effectively cures the EAC. In such cases, a careful history will show which rash came first.

When the cause is not immediately obvious, potential triggers that should be investigated include: occult malignancy, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and pregnancy. Examination of skin distant from the obviously affected areas is often necessary, with special attention to the feet, groin, and scalp. Laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, liver function tests, rapid plasma reagin test, urinalysis, and chest x-ray for completeness.

EAC is treated, as mentioned earlier, by finding and eliminating the underlying cause. That often proves impossible, so steroid therapy (oral or topical) is often employed with some effect (though it will not prevent recurrences of the condition). Empiric use of oral antibiotics has produced mixed results. The condition can persist for years but is seldom significantly symptomatic.

A 44-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic rash that manifested several weeks ago. His primary care provider called it “ringworm,” but it has been unresponsive to topical antifungal creams, including clotrimazole and tolnaftate. The patient also sought evaluation in an urgent care setting, where the provider diagnosed “psoriasis” and prescribed triamcinolone, which didn’t seem to help. Additional history taking reveals that, two weeks before the lesions appeared, the patient received a diagnosis of strep throat and subsequently was treated with amoxicillin. The patient is otherwise healthy, taking no medications regularly. On examination, the rash is quite striking—brightly erythematous, with annular margins on which the skin is red. But just behind the advancing margin is a parallel band of scaling. At its largest dimension, the papulosquamous patch is slightly in excess of 8 cm. Microscopic examination of scrapings from the lesion’s scale is negative for fungal elements. The rest of the patient’s skin, with particular attention to the feet and groin, is well within normal limits. Punch biopsy of the lesion shows intense lymphohistiocytic cuffing around superficial and deep dermal vessels, with no epidermal involvement. Stains for fungal elements are negative.

Woman with Foot Pain After Neurosurgery Service

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates mild soft-tissue swelling and an oblique, mildly displaced fracture of the distal fibula. In addition, there is a small bone density adjacent to the medial malleolus, which could represent either an unfused accessory ossification center or a sequela of prior trauma.

On closer questioning, the patient acknowledged that a few months prior, she had stepped in a hole and been treated for a “broken bone.” She had been in a cast for an undisclosed period of time; at a follow-up appointment, the cast had been removed and the bone had been declared “healed.”

A new orthopedic consultation was obtained prior to the patient’s discharge from the hospital, which resulted in placement of a short leg cast.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates mild soft-tissue swelling and an oblique, mildly displaced fracture of the distal fibula. In addition, there is a small bone density adjacent to the medial malleolus, which could represent either an unfused accessory ossification center or a sequela of prior trauma.

On closer questioning, the patient acknowledged that a few months prior, she had stepped in a hole and been treated for a “broken bone.” She had been in a cast for an undisclosed period of time; at a follow-up appointment, the cast had been removed and the bone had been declared “healed.”

A new orthopedic consultation was obtained prior to the patient’s discharge from the hospital, which resulted in placement of a short leg cast.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates mild soft-tissue swelling and an oblique, mildly displaced fracture of the distal fibula. In addition, there is a small bone density adjacent to the medial malleolus, which could represent either an unfused accessory ossification center or a sequela of prior trauma.

On closer questioning, the patient acknowledged that a few months prior, she had stepped in a hole and been treated for a “broken bone.” She had been in a cast for an undisclosed period of time; at a follow-up appointment, the cast had been removed and the bone had been declared “healed.”

A new orthopedic consultation was obtained prior to the patient’s discharge from the hospital, which resulted in placement of a short leg cast.

A 60-year-old woman is admitted electively to the neurosurgery service for a multilevel posterior cervical decompression and fusion. The procedure is completed uneventfully and without complication. The patient is admitted to the neurosurgical floor. In the middle of the night, you receive a call from the nurse stating that the patient is complaining of moderate pain and swelling in her left ankle and foot, which occurred after she got up to use the bathroom. The patient denies injuring herself. She complains of pain with weight-bearing. Since the pain is tolerable and pain medication has already been given, it is decided to assess the complaint later in the morning. On evaluation, the left foot and ankle are mildly swollen, with tenderness on the lateral aspect. There is minimal tenderness on the foot. Distal pulses and color are good. The calf is nontender. The patient’s medical history is significant only for mild hypertension. Radiographs of the left ankle are obtained. What is your impression?