User login

Scarring Head Wound

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

A 60-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic with a wound on the scalp that had persisted for 11 months. The lesion started as a small erosion that eventually progressed to involve the entire parietal scalp. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Graves disease. Physical examination demonstrated a large scar over the vertex scalp with central erosion, overlying crust, peripheral scalp atrophy, hypopigmentation at the periphery, and exaggerated superficial vasculature. Some oral erosions also were observed. A review of systems was negative for any constitutional symptoms. A month prior, the patient had been started on dapsone 50 mg with a prednisone taper by an outside dermatologist and noticed some improvement.

Persistent Wounds Refractory to Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics

The Diagnosis: PASH (Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, Hidradenitis Suppurativa) Syndrome

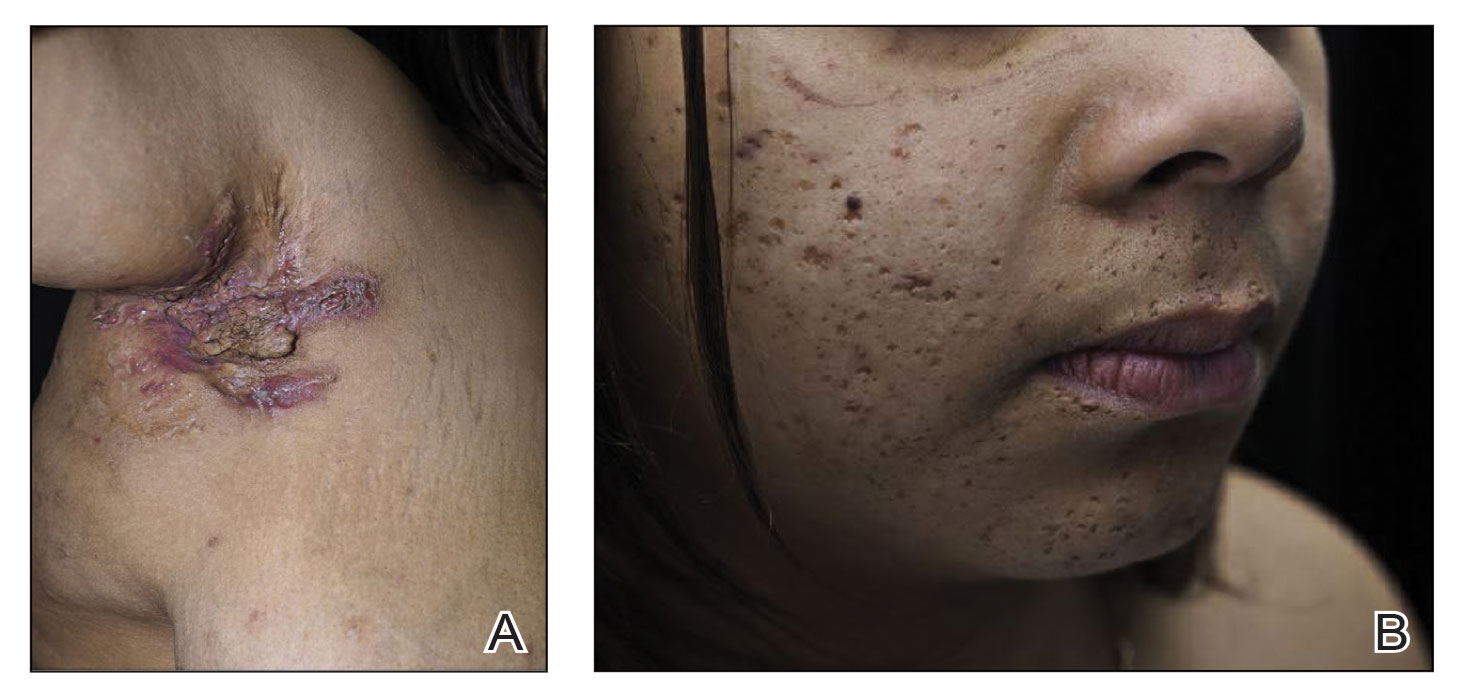

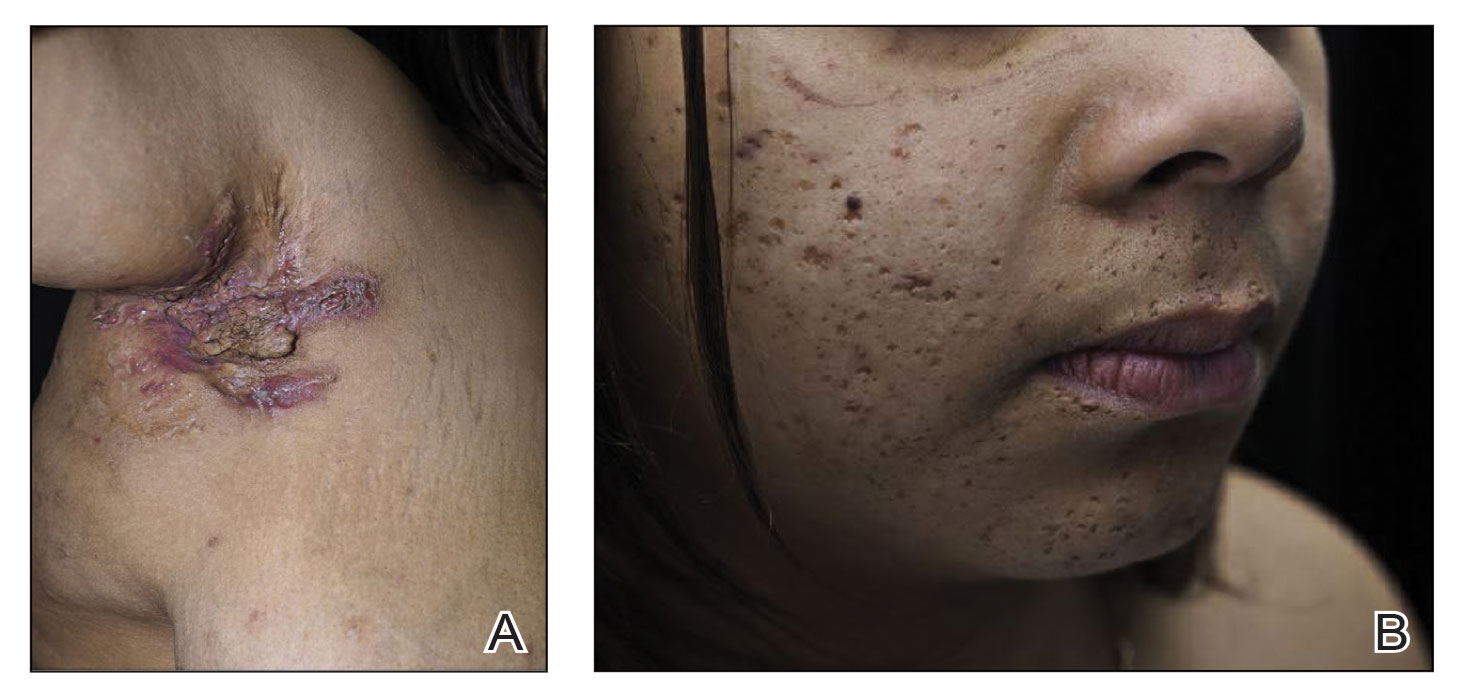

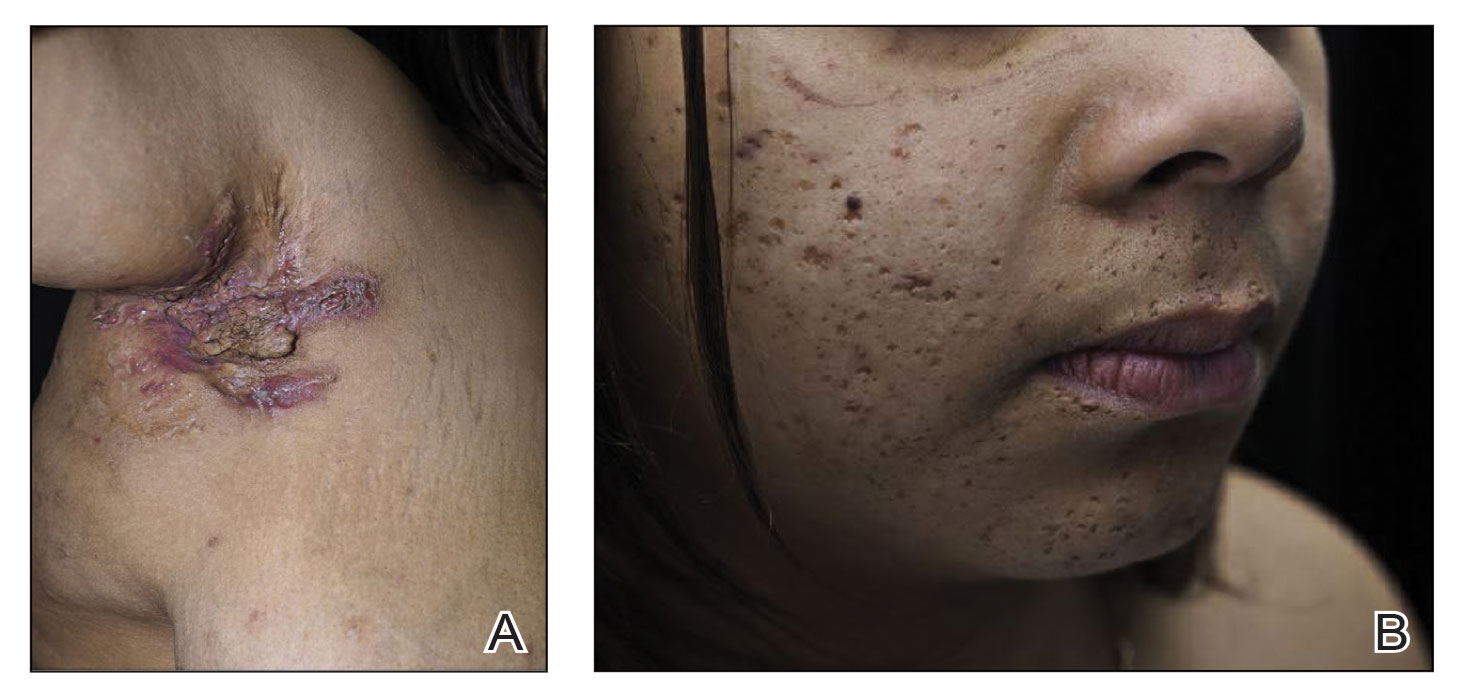

Obtaining our patient’s history of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a hallmark sterile neutrophilic dermatosis, was key to making the correct diagnosis of PASH (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, HS) syndrome. In our patient, the history of HS increased the consideration of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) due to the persistent breast and leg wounds. Additionally, it was important to consider a diagnosis of PG in lesions that were not responding to broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment. In our patient, the concurrent presentation of draining abscesses in the axillae (Figure, A) and inflammatory nodulocystic facial acne (Figure, B) were additional diagnostic clues that suggested the triad of PASH syndrome.

Although SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis) syndrome also can present with cutaneous features of acne and HS, the lack of bone and joint involvement in our patient made this diagnosis less likely. Calciphylaxis can present as ulcerations on the lower extremities, but it usually presents with a livedolike pattern with overlying black eschar and is unlikely in the absence of underlying metabolic or renal disease. PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne) syndrome is characterized by recurrent joint involvement and lacks features of HS. Lastly, our patient was immunocompetent with no risk factors for mycobacterial infection.

PASH syndrome is a rare inherited syndrome, but its constituent inflammatory conditions are ubiquitous. They share a common underlying mechanism consisting of overactivation of the innate immune systems driven by increased production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α, resulting in sterile neutrophilic dermatoses.1 The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation, as laboratory investigations are nondiagnostic. Biopsies and cultures can be performed to rule out infectious etiologies. Additionally, PASH syndrome is considered part of a larger spectrum of syndromes including PAPA and PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, acne, PG, HS) syndromes. The absence of pyogenic arthritis distinguishes PASH syndrome from PAPA and PAPASH syndromes.2 Clinically, PASH syndrome and the related sterile neutrophilic dermatoses share the characteristic of pronounced cutaneous involvement that substantially alters the patient’s quality of life. Cigarette smoking is an exacerbating factor and has a well-established association with HS.3 Therefore, smoking cessation should be encouraged in these patients to avoid exacerbation of the disease process.

Maintaining adequate immunosuppression is key to managing the underlying disease processes. Classic immunosuppressive agents such as systemic glucocorticoids and methotrexate may fail to satisfactorily control the disease.4 Treatment options currently are somewhat limited and are aimed at targeting the inflammatory cytokines that propagate the disease. The most consistent responses have been observed with anti–tumor necrosis factor α antagonists such as adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept.5 Additionally, there is varied response to anakinra, suggesting the importance of selectively targeting IL-1β.6 Unfortunately, misdiagnosis for an infectious etiology is common, and antibiotics and debridement are of limited use for the underlying pathophysiology of PASH syndrome. Importantly, biopsy and debridement often are discouraged due to the risk of pathergy.7

Our case demonstrates the importance of maintaining a high clinical suspicion for immune-mediated lesions that are refractory to antimicrobial agents. Additionally, prior history of multiple neutrophilic dermatoses should prompt consideration for the PASH/PAPA/PAPASH disease spectrum. Early and accurate identification of neutrophilic dermatoses such as PG and HS are crucial to initiating proper cytokine-targeting treatment and achieving disease remission.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Garcovich S, et al. PAPA spectrum disorders. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155:542-550.

- König A, Lehmann C, Rompel R, et al. Cigarette smoking as a triggering factor of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 1999;198:261-264.

- Ahn C, Negus D, Huang W. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:225-233.

- Saint-Georges V, Peternel S, Kaštelan M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor antagonists in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndrome. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018;26:173-178.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Patel DK, Locke M, Jarrett P. Pyoderma gangrenosum with pathergy: a potentially significant complication following breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:884-892.

The Diagnosis: PASH (Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, Hidradenitis Suppurativa) Syndrome

Obtaining our patient’s history of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a hallmark sterile neutrophilic dermatosis, was key to making the correct diagnosis of PASH (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, HS) syndrome. In our patient, the history of HS increased the consideration of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) due to the persistent breast and leg wounds. Additionally, it was important to consider a diagnosis of PG in lesions that were not responding to broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment. In our patient, the concurrent presentation of draining abscesses in the axillae (Figure, A) and inflammatory nodulocystic facial acne (Figure, B) were additional diagnostic clues that suggested the triad of PASH syndrome.

Although SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis) syndrome also can present with cutaneous features of acne and HS, the lack of bone and joint involvement in our patient made this diagnosis less likely. Calciphylaxis can present as ulcerations on the lower extremities, but it usually presents with a livedolike pattern with overlying black eschar and is unlikely in the absence of underlying metabolic or renal disease. PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne) syndrome is characterized by recurrent joint involvement and lacks features of HS. Lastly, our patient was immunocompetent with no risk factors for mycobacterial infection.

PASH syndrome is a rare inherited syndrome, but its constituent inflammatory conditions are ubiquitous. They share a common underlying mechanism consisting of overactivation of the innate immune systems driven by increased production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α, resulting in sterile neutrophilic dermatoses.1 The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation, as laboratory investigations are nondiagnostic. Biopsies and cultures can be performed to rule out infectious etiologies. Additionally, PASH syndrome is considered part of a larger spectrum of syndromes including PAPA and PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, acne, PG, HS) syndromes. The absence of pyogenic arthritis distinguishes PASH syndrome from PAPA and PAPASH syndromes.2 Clinically, PASH syndrome and the related sterile neutrophilic dermatoses share the characteristic of pronounced cutaneous involvement that substantially alters the patient’s quality of life. Cigarette smoking is an exacerbating factor and has a well-established association with HS.3 Therefore, smoking cessation should be encouraged in these patients to avoid exacerbation of the disease process.

Maintaining adequate immunosuppression is key to managing the underlying disease processes. Classic immunosuppressive agents such as systemic glucocorticoids and methotrexate may fail to satisfactorily control the disease.4 Treatment options currently are somewhat limited and are aimed at targeting the inflammatory cytokines that propagate the disease. The most consistent responses have been observed with anti–tumor necrosis factor α antagonists such as adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept.5 Additionally, there is varied response to anakinra, suggesting the importance of selectively targeting IL-1β.6 Unfortunately, misdiagnosis for an infectious etiology is common, and antibiotics and debridement are of limited use for the underlying pathophysiology of PASH syndrome. Importantly, biopsy and debridement often are discouraged due to the risk of pathergy.7

Our case demonstrates the importance of maintaining a high clinical suspicion for immune-mediated lesions that are refractory to antimicrobial agents. Additionally, prior history of multiple neutrophilic dermatoses should prompt consideration for the PASH/PAPA/PAPASH disease spectrum. Early and accurate identification of neutrophilic dermatoses such as PG and HS are crucial to initiating proper cytokine-targeting treatment and achieving disease remission.

The Diagnosis: PASH (Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, Hidradenitis Suppurativa) Syndrome

Obtaining our patient’s history of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a hallmark sterile neutrophilic dermatosis, was key to making the correct diagnosis of PASH (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, HS) syndrome. In our patient, the history of HS increased the consideration of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) due to the persistent breast and leg wounds. Additionally, it was important to consider a diagnosis of PG in lesions that were not responding to broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment. In our patient, the concurrent presentation of draining abscesses in the axillae (Figure, A) and inflammatory nodulocystic facial acne (Figure, B) were additional diagnostic clues that suggested the triad of PASH syndrome.

Although SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis) syndrome also can present with cutaneous features of acne and HS, the lack of bone and joint involvement in our patient made this diagnosis less likely. Calciphylaxis can present as ulcerations on the lower extremities, but it usually presents with a livedolike pattern with overlying black eschar and is unlikely in the absence of underlying metabolic or renal disease. PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne) syndrome is characterized by recurrent joint involvement and lacks features of HS. Lastly, our patient was immunocompetent with no risk factors for mycobacterial infection.

PASH syndrome is a rare inherited syndrome, but its constituent inflammatory conditions are ubiquitous. They share a common underlying mechanism consisting of overactivation of the innate immune systems driven by increased production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α, resulting in sterile neutrophilic dermatoses.1 The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation, as laboratory investigations are nondiagnostic. Biopsies and cultures can be performed to rule out infectious etiologies. Additionally, PASH syndrome is considered part of a larger spectrum of syndromes including PAPA and PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, acne, PG, HS) syndromes. The absence of pyogenic arthritis distinguishes PASH syndrome from PAPA and PAPASH syndromes.2 Clinically, PASH syndrome and the related sterile neutrophilic dermatoses share the characteristic of pronounced cutaneous involvement that substantially alters the patient’s quality of life. Cigarette smoking is an exacerbating factor and has a well-established association with HS.3 Therefore, smoking cessation should be encouraged in these patients to avoid exacerbation of the disease process.

Maintaining adequate immunosuppression is key to managing the underlying disease processes. Classic immunosuppressive agents such as systemic glucocorticoids and methotrexate may fail to satisfactorily control the disease.4 Treatment options currently are somewhat limited and are aimed at targeting the inflammatory cytokines that propagate the disease. The most consistent responses have been observed with anti–tumor necrosis factor α antagonists such as adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept.5 Additionally, there is varied response to anakinra, suggesting the importance of selectively targeting IL-1β.6 Unfortunately, misdiagnosis for an infectious etiology is common, and antibiotics and debridement are of limited use for the underlying pathophysiology of PASH syndrome. Importantly, biopsy and debridement often are discouraged due to the risk of pathergy.7

Our case demonstrates the importance of maintaining a high clinical suspicion for immune-mediated lesions that are refractory to antimicrobial agents. Additionally, prior history of multiple neutrophilic dermatoses should prompt consideration for the PASH/PAPA/PAPASH disease spectrum. Early and accurate identification of neutrophilic dermatoses such as PG and HS are crucial to initiating proper cytokine-targeting treatment and achieving disease remission.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Garcovich S, et al. PAPA spectrum disorders. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155:542-550.

- König A, Lehmann C, Rompel R, et al. Cigarette smoking as a triggering factor of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 1999;198:261-264.

- Ahn C, Negus D, Huang W. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:225-233.

- Saint-Georges V, Peternel S, Kaštelan M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor antagonists in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndrome. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018;26:173-178.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Patel DK, Locke M, Jarrett P. Pyoderma gangrenosum with pathergy: a potentially significant complication following breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:884-892.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Garcovich S, et al. PAPA spectrum disorders. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155:542-550.

- König A, Lehmann C, Rompel R, et al. Cigarette smoking as a triggering factor of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 1999;198:261-264.

- Ahn C, Negus D, Huang W. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:225-233.

- Saint-Georges V, Peternel S, Kaštelan M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor antagonists in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndrome. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018;26:173-178.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Patel DK, Locke M, Jarrett P. Pyoderma gangrenosum with pathergy: a potentially significant complication following breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:884-892.

A 28-year-old Black woman presented to the hospital for evaluation of worsening leg wounds as well as a similar eroding plaque on the left breast of 1 month’s duration. Broad-spectrum antibiotics prescribed during a prior emergency department visit resulted in no improvement. Her medical history was notable for hidradenitis suppurativa that previously was well controlled on adalimumab prior to discontinuation 1 year prior. A review of systems was negative for fever, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, night sweats, and arthralgia. The patient had discontinued the antibiotics and was not taking any other medications at the time of presentation. She reported a history of smoking cigarettes (5 pack years). Physical examination revealed hyperkeratotic eroded plaques with violaceous borders circumferentially around the left breast (top) and legs with notable undermining (bottom). Inflammatory nodulocystic acne of the face as well as sinus tract formation with purulent drainage in the axillae also were present. Laboratory workup revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (116 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]). Computed tomography of the leg wound was negative for soft-tissue infection. Aerobic and anaerobic tissue cultures demonstrated no growth.