User login

Furuncular Myiasis in 2 American Travelers Returning From Senegal

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to the emergency department with painful, pruritic, erythematous nodules on the bilateral legs of 1 week’s duration. The lesions had developed 1 week after returning from a monthlong trip to Senegal with a volunteer youth group. He did not recall sustaining any painful insect bites or illnesses while traveling in Africa and only noticed the erythematous papules on the legs when he returned home to the United States. After consulting with his primary care physician and a local dermatologist, the patient began taking oral cephalexin for suspected bacterial furunculosis with no considerable improvement. Over the course of 1 week, the lesions became increasingly painful and pruritic, prompting a visit to the emergency department. Prior to his arrival, the patient reported squeezing a live worm from one of the lesions on the right ankle.

On presentation, the patient was afebrile (temperature, 36.7°C) and his vital signs revealed no abnormalities. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous nodules on the bilateral heels, ankles, and shins with pinpoint puncta noted at the center of many of the lesions (Figure 1). The nodules were warm and indurated and no pulsatile movement was appreciated. The legs appeared to be well perfused with intact sensation and motor function. The patient brought in the live mobile larva that he extruded from the lesion on the right ankle. Both the departments of infectious diseases and dermatology were consulted and a preliminary diagnosis of furuncular myiasis was made.

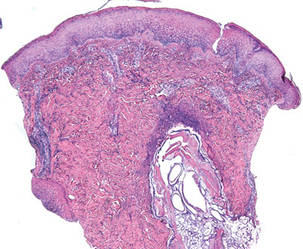

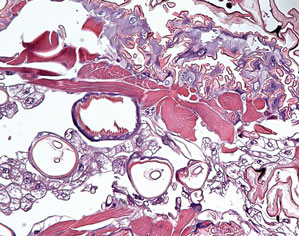

The lesions were occluded with petroleum jelly and the patient was instructed to follow-up with the dermatology department later that same day. On follow-up in the dermatology clinic, the tips of intact larvae were appreciated at the central puncta of some of the lesions (Figure 2). Lidocaine adrenaline tetracaine gel was applied to lesions on the legs for 40 minutes, then lidocaine gel 1% was injected into each lesion. On injection, immobile larvae were ejected from the central puncta of most of the lesions; the remaining lesions were treated via 3-mm punch biopsy as a means of extraction. Each nodule contained only a single larva, all of which were dead at the time of removal (Figure 3). The wounds were left open and the patient was instructed to continue treatment with cephalexin with leg elevation and rest. Pathologic examination of deep dermal skin sections revealed larval fragments encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with spines that were consistent with furuncular myiasis (Figures 4 and 5). Given the patient’s recent history of travel to Africa along with the morphology of the extracted specimens, the larvae were identified as Cordylobia anthropophaga, a common cause of furuncular myiasis in that region.

Patient 2

The next week, a 17-year-old adolescent girl who had been on the same trip to Senegal as patient 1 presented with 2 similar erythematous nodules with central crusts on the left inner thigh and buttock. On noticing the lesions approximately 3 days prior to presentation, the patient applied topical antibiotic ointment to each nodule, which incited the evacuation of white tube-shaped structures that were presented for examination. On presentation, the nodules were healing well. Given the patient’s travel history and physical examination, a presumptive diagnosis of furuncular myiasis from C anthropophaga also was made.

|

Comment

The term myiasis stems from the Greek term for fly and is used to describe the infestation of fly larvae in living vertebrates.1 Myiasis has many classifications, the 3 most common being furuncular, migratory, and wound myiasis, which are differentiated by the different fly species found in distinct regions of the world. Furuncular myiasis is the most benign form, usually affecting only a localized region of the skin; migratory myiasis is characterized by larvae traveling substantial distances from one anatomic site to another within the lower layers of the epidermis; and wound myiasis involves rapid reproduction of larvae in necrotic tissue with subsequent tissue destruction.2

The clinical presentation of the lesions noted in our patients suggested a diagnosis of furuncular myiasis, which commonly is caused by Dermatobia hominis, C anthropophaga, Cuterebra species, Wohlfahrtia vigil, and Wohlfahrtia opaca larvae.3Dermatobia hominis is the most common cause of furuncular myiasis and usually is found in Central and South America. Our patients likely developed an infestation of C anthropophaga (also known as the tumbu fly), a yellow-brown, 7- to 12-mm blowfly commonly found throughout tropical Africa.3 Although C anthropophaga is historically limited to sub-Saharan Africa, there has been a report of a case acquired in Portugal.4

In a review of the literature, C anthropophaga myiasis was documented in Italian travelers returning from Senegal5-7; our cases are unique because they represent North American travelers returning from Senegal with furuncular myiasis. Furuncular myiasis from C anthropophaga has been reported in travelers returning to North America from other African countries, including Angola,8 Tanzania,9-11 Kenya,9 Sierra Leone,12 and Ivory Coast.13 Several cases of ocular myiasis from D hominis and Oestrus ovis have been reported in European travelers returning from Tunisia.14,15

Tumbu fly infestations typically affect dogs and rodents but can arise in human hosts.3 Children may be affected by C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis more often than adults because they have thinner skin and less immunity to the larvae.2

|

There are 2 mechanisms by which infestation of human hosts by C anthropophaga can occur. Most commonly, female flies lay eggs in shady areas in soil that is contaminated by feces or urine. The hatched larvae can survive in the ground for up to 2 weeks and later attach to a host when prompted by heat or movement.3 Therefore, clothing set out to dry may be contaminated by this soil. Alternatively, female flies can lay eggs directly onto clothing that is contaminated by feces or urine and the larvae subsequently hatch outside the soil with easy access to human skin once the clothing is worn.2

Common penetration sites are the head, neck, and back, as well as areas covered by contaminated or infested clothing.2,3 Penetration of the human skin occurs instantly and is a painless process that is rarely noticed by the human host.3 The larvae burrow into the skin for 8 to 12 days, resulting in a furuncle that occasionally secretes a serous fluid.2 Within the first 2 days of infestation, the host may experience symptoms ranging from local pruritus to severe pain. Six days following initial onset, an intense inflammatory response may result in local lymphadenopathy along with fever and fatigue.2 The larvae use their posterior spiracles to create openings in the skin to create air holes that allow them to breathe.3 On physical examination, the spiracles generally appear as 1- to 3-mm dark linear streaks within furuncles, which is important in the diagnosis of C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis.1,3 If spiracles are not appreciated on initial examination, diagnosis can be made by submerging the affected areas in water or saliva to look for air bubbles arising from the central puncta of the lesions.1

All causes of furuncular myiasis are characterized by a ratio of 1 larva to 1 furuncle.16 Although most of these types of larvae that can cause furuncular myiasis result in single lesions, C anthropophaga infestation often produces several furuncles that may coalesce into plaques.1,2 The differential diagnosis for C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis includes pyoderma, impetigo, staphylococcal furunculosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, infected cyst, retained foreign body, and facticial disease.2,3 Dracunculiasis also may be considered, which occurs after ingestion of contaminated water.2 Ultrasonography may be helpful for the diagnosis of furuncular myiasis, as it can facilitate identification of foreign bodies, abscesses, and even larvae in some cases.17 Definitive diagnosis of any type of myiasis involves extraction of the larva and identification of the family, genus, and species by a parasitologist.1 Some experts suggest rearing preserved live larvae with raw meat after extraction because adult specimens are more reliable than larvae for species diagnosis.1

Treatment of furuncular myiasis involves occlusion and extraction of the larvae from the skin. Suffocation of the larvae by occlusion of air holes with petroleum jelly, paraffin oil, bacon fat, glue, and other obstructing substances forces the larvae to emerge in search of oxygen, though immature larvae may be more reluctant than mature ones.2,3 Definitive treatment involves the direct removal of the larvae by surgery or expulsion by pressure, though it is recommended that lesions are pretreated with occlusive techniques.1,3 Other reported methods of extraction include injection of lidocaine and the use of a commercial venom extractor.1 It should be noted that rupture and incomplete extraction of larvae can lead to secondary infections and allergic reactions. Lesions can be pretreated with lidocaine gel prior to extraction, and antibiotics should be used in cases of secondary bacterial infection. Ivermectin also has been reported as a treatment of furuncular myiasis and other types of myiasis.1 Prevention of infestation by C anthropophaga includes avoidance of endemic areas, maintaining good hygiene, and ironing clothing or drying it in sunny locations.1,2 Overall, furuncular myiasis has a good prognosis with rapid recovery and a low incidence of complications.1

Conclusion

We present 2 cases of travelers returning to North America from Senegal with C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis. Careful review of travel history, physical examination, and identification of fly larvae are important for diagnosis. Individuals traveling to sub-Saharan Africa should avoid drying clothes in shady places and lying on the ground. They also are urged to iron their clothing before wearing it.

1. Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

2. McGraw TA, Turiansky GW. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:907-926.

3. Robbins K, Khachemoune A. Cutaneous myiasis: a review of the common types of myiasis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1092-1098.

4. Curtis SJ, Edwards C, Athulathmuda C, et al. Case of the month: cutaneous myiasis in a returning traveller from the Algarve: first report of tumbu maggots, Cordylobia anthropophaga, acquired in Portugal. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:236-237.

5. Veraldi S, Brusasco A, Süss L. Cutaneous myiasis caused by larvae of Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard). Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:184-187.

6. Cultrera R, Dettori G, Calderaro A, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard 1872): description of 5 cases from costal regions of Senegal [in Italian]. Parassitologia. 1993;35:47-49.

7. Fusco FM, Nardiello S, Brancaccio G, et al. Cutaneous myiasis from Cordylobia anthropophaga in a traveller returning from Senegal: a case study [in Italian]. Infez Med. 2005;13:109-111.

8. Lee EJ, Robinson F. Furuncular myiasis of the face caused by larva of the tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga)[published online ahead of print July 21, 2006]. Eye (Lond). 2007;21:268-269.

9. Rice PL, Gleason N. Two cases of myiasis in the United States by the African tumbu fly, Cordylobia anthropophaga (Diptera, Calliphoridae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972;21:62-65.

10. March CH. A case of “ver du Cayor” in Manhattan. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:32-33.

11. Schorr WF. Tumbu-fly myiasis in Marshfield, Wis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:61-62.

12. Potter TS, Dorman MA, Ghaemi M, et al. Inflammatory papules on the back of a traveling businessman. tumbu

fly myiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:951, 954.

13. Ockenhouse CF, Samlaska CP, Benson PM, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:199-202.

14. Kaouech E, Kallel K, Belhadj S, et al. Dermatobia hominis furuncular myiasis in a man returning from Latin America: first imported case in Tunisia [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2010;70:135-136.

15. Zayani A, Chaabouni M, Gouiaa R, et al. Conjuctival myiasis. 23 cases in the Tunisian Sahel [in French]. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1989;66:289-292.

16. Latorre M, Ullate JV, Sanchez J, et al. A case of myiasis due to Dermatobia hominis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:968-969.

17. Mahal JJ, Sperling JD. Furuncular myiasis from Dermatobia hominis: a case of human botfly infestation [published online ahead of print February 1, 2010]. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:618-621.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to the emergency department with painful, pruritic, erythematous nodules on the bilateral legs of 1 week’s duration. The lesions had developed 1 week after returning from a monthlong trip to Senegal with a volunteer youth group. He did not recall sustaining any painful insect bites or illnesses while traveling in Africa and only noticed the erythematous papules on the legs when he returned home to the United States. After consulting with his primary care physician and a local dermatologist, the patient began taking oral cephalexin for suspected bacterial furunculosis with no considerable improvement. Over the course of 1 week, the lesions became increasingly painful and pruritic, prompting a visit to the emergency department. Prior to his arrival, the patient reported squeezing a live worm from one of the lesions on the right ankle.

On presentation, the patient was afebrile (temperature, 36.7°C) and his vital signs revealed no abnormalities. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous nodules on the bilateral heels, ankles, and shins with pinpoint puncta noted at the center of many of the lesions (Figure 1). The nodules were warm and indurated and no pulsatile movement was appreciated. The legs appeared to be well perfused with intact sensation and motor function. The patient brought in the live mobile larva that he extruded from the lesion on the right ankle. Both the departments of infectious diseases and dermatology were consulted and a preliminary diagnosis of furuncular myiasis was made.

The lesions were occluded with petroleum jelly and the patient was instructed to follow-up with the dermatology department later that same day. On follow-up in the dermatology clinic, the tips of intact larvae were appreciated at the central puncta of some of the lesions (Figure 2). Lidocaine adrenaline tetracaine gel was applied to lesions on the legs for 40 minutes, then lidocaine gel 1% was injected into each lesion. On injection, immobile larvae were ejected from the central puncta of most of the lesions; the remaining lesions were treated via 3-mm punch biopsy as a means of extraction. Each nodule contained only a single larva, all of which were dead at the time of removal (Figure 3). The wounds were left open and the patient was instructed to continue treatment with cephalexin with leg elevation and rest. Pathologic examination of deep dermal skin sections revealed larval fragments encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with spines that were consistent with furuncular myiasis (Figures 4 and 5). Given the patient’s recent history of travel to Africa along with the morphology of the extracted specimens, the larvae were identified as Cordylobia anthropophaga, a common cause of furuncular myiasis in that region.

Patient 2

The next week, a 17-year-old adolescent girl who had been on the same trip to Senegal as patient 1 presented with 2 similar erythematous nodules with central crusts on the left inner thigh and buttock. On noticing the lesions approximately 3 days prior to presentation, the patient applied topical antibiotic ointment to each nodule, which incited the evacuation of white tube-shaped structures that were presented for examination. On presentation, the nodules were healing well. Given the patient’s travel history and physical examination, a presumptive diagnosis of furuncular myiasis from C anthropophaga also was made.

|

Comment

The term myiasis stems from the Greek term for fly and is used to describe the infestation of fly larvae in living vertebrates.1 Myiasis has many classifications, the 3 most common being furuncular, migratory, and wound myiasis, which are differentiated by the different fly species found in distinct regions of the world. Furuncular myiasis is the most benign form, usually affecting only a localized region of the skin; migratory myiasis is characterized by larvae traveling substantial distances from one anatomic site to another within the lower layers of the epidermis; and wound myiasis involves rapid reproduction of larvae in necrotic tissue with subsequent tissue destruction.2

The clinical presentation of the lesions noted in our patients suggested a diagnosis of furuncular myiasis, which commonly is caused by Dermatobia hominis, C anthropophaga, Cuterebra species, Wohlfahrtia vigil, and Wohlfahrtia opaca larvae.3Dermatobia hominis is the most common cause of furuncular myiasis and usually is found in Central and South America. Our patients likely developed an infestation of C anthropophaga (also known as the tumbu fly), a yellow-brown, 7- to 12-mm blowfly commonly found throughout tropical Africa.3 Although C anthropophaga is historically limited to sub-Saharan Africa, there has been a report of a case acquired in Portugal.4

In a review of the literature, C anthropophaga myiasis was documented in Italian travelers returning from Senegal5-7; our cases are unique because they represent North American travelers returning from Senegal with furuncular myiasis. Furuncular myiasis from C anthropophaga has been reported in travelers returning to North America from other African countries, including Angola,8 Tanzania,9-11 Kenya,9 Sierra Leone,12 and Ivory Coast.13 Several cases of ocular myiasis from D hominis and Oestrus ovis have been reported in European travelers returning from Tunisia.14,15

Tumbu fly infestations typically affect dogs and rodents but can arise in human hosts.3 Children may be affected by C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis more often than adults because they have thinner skin and less immunity to the larvae.2

|

There are 2 mechanisms by which infestation of human hosts by C anthropophaga can occur. Most commonly, female flies lay eggs in shady areas in soil that is contaminated by feces or urine. The hatched larvae can survive in the ground for up to 2 weeks and later attach to a host when prompted by heat or movement.3 Therefore, clothing set out to dry may be contaminated by this soil. Alternatively, female flies can lay eggs directly onto clothing that is contaminated by feces or urine and the larvae subsequently hatch outside the soil with easy access to human skin once the clothing is worn.2

Common penetration sites are the head, neck, and back, as well as areas covered by contaminated or infested clothing.2,3 Penetration of the human skin occurs instantly and is a painless process that is rarely noticed by the human host.3 The larvae burrow into the skin for 8 to 12 days, resulting in a furuncle that occasionally secretes a serous fluid.2 Within the first 2 days of infestation, the host may experience symptoms ranging from local pruritus to severe pain. Six days following initial onset, an intense inflammatory response may result in local lymphadenopathy along with fever and fatigue.2 The larvae use their posterior spiracles to create openings in the skin to create air holes that allow them to breathe.3 On physical examination, the spiracles generally appear as 1- to 3-mm dark linear streaks within furuncles, which is important in the diagnosis of C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis.1,3 If spiracles are not appreciated on initial examination, diagnosis can be made by submerging the affected areas in water or saliva to look for air bubbles arising from the central puncta of the lesions.1

All causes of furuncular myiasis are characterized by a ratio of 1 larva to 1 furuncle.16 Although most of these types of larvae that can cause furuncular myiasis result in single lesions, C anthropophaga infestation often produces several furuncles that may coalesce into plaques.1,2 The differential diagnosis for C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis includes pyoderma, impetigo, staphylococcal furunculosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, infected cyst, retained foreign body, and facticial disease.2,3 Dracunculiasis also may be considered, which occurs after ingestion of contaminated water.2 Ultrasonography may be helpful for the diagnosis of furuncular myiasis, as it can facilitate identification of foreign bodies, abscesses, and even larvae in some cases.17 Definitive diagnosis of any type of myiasis involves extraction of the larva and identification of the family, genus, and species by a parasitologist.1 Some experts suggest rearing preserved live larvae with raw meat after extraction because adult specimens are more reliable than larvae for species diagnosis.1

Treatment of furuncular myiasis involves occlusion and extraction of the larvae from the skin. Suffocation of the larvae by occlusion of air holes with petroleum jelly, paraffin oil, bacon fat, glue, and other obstructing substances forces the larvae to emerge in search of oxygen, though immature larvae may be more reluctant than mature ones.2,3 Definitive treatment involves the direct removal of the larvae by surgery or expulsion by pressure, though it is recommended that lesions are pretreated with occlusive techniques.1,3 Other reported methods of extraction include injection of lidocaine and the use of a commercial venom extractor.1 It should be noted that rupture and incomplete extraction of larvae can lead to secondary infections and allergic reactions. Lesions can be pretreated with lidocaine gel prior to extraction, and antibiotics should be used in cases of secondary bacterial infection. Ivermectin also has been reported as a treatment of furuncular myiasis and other types of myiasis.1 Prevention of infestation by C anthropophaga includes avoidance of endemic areas, maintaining good hygiene, and ironing clothing or drying it in sunny locations.1,2 Overall, furuncular myiasis has a good prognosis with rapid recovery and a low incidence of complications.1

Conclusion

We present 2 cases of travelers returning to North America from Senegal with C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis. Careful review of travel history, physical examination, and identification of fly larvae are important for diagnosis. Individuals traveling to sub-Saharan Africa should avoid drying clothes in shady places and lying on the ground. They also are urged to iron their clothing before wearing it.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to the emergency department with painful, pruritic, erythematous nodules on the bilateral legs of 1 week’s duration. The lesions had developed 1 week after returning from a monthlong trip to Senegal with a volunteer youth group. He did not recall sustaining any painful insect bites or illnesses while traveling in Africa and only noticed the erythematous papules on the legs when he returned home to the United States. After consulting with his primary care physician and a local dermatologist, the patient began taking oral cephalexin for suspected bacterial furunculosis with no considerable improvement. Over the course of 1 week, the lesions became increasingly painful and pruritic, prompting a visit to the emergency department. Prior to his arrival, the patient reported squeezing a live worm from one of the lesions on the right ankle.

On presentation, the patient was afebrile (temperature, 36.7°C) and his vital signs revealed no abnormalities. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous nodules on the bilateral heels, ankles, and shins with pinpoint puncta noted at the center of many of the lesions (Figure 1). The nodules were warm and indurated and no pulsatile movement was appreciated. The legs appeared to be well perfused with intact sensation and motor function. The patient brought in the live mobile larva that he extruded from the lesion on the right ankle. Both the departments of infectious diseases and dermatology were consulted and a preliminary diagnosis of furuncular myiasis was made.

The lesions were occluded with petroleum jelly and the patient was instructed to follow-up with the dermatology department later that same day. On follow-up in the dermatology clinic, the tips of intact larvae were appreciated at the central puncta of some of the lesions (Figure 2). Lidocaine adrenaline tetracaine gel was applied to lesions on the legs for 40 minutes, then lidocaine gel 1% was injected into each lesion. On injection, immobile larvae were ejected from the central puncta of most of the lesions; the remaining lesions were treated via 3-mm punch biopsy as a means of extraction. Each nodule contained only a single larva, all of which were dead at the time of removal (Figure 3). The wounds were left open and the patient was instructed to continue treatment with cephalexin with leg elevation and rest. Pathologic examination of deep dermal skin sections revealed larval fragments encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with spines that were consistent with furuncular myiasis (Figures 4 and 5). Given the patient’s recent history of travel to Africa along with the morphology of the extracted specimens, the larvae were identified as Cordylobia anthropophaga, a common cause of furuncular myiasis in that region.

Patient 2

The next week, a 17-year-old adolescent girl who had been on the same trip to Senegal as patient 1 presented with 2 similar erythematous nodules with central crusts on the left inner thigh and buttock. On noticing the lesions approximately 3 days prior to presentation, the patient applied topical antibiotic ointment to each nodule, which incited the evacuation of white tube-shaped structures that were presented for examination. On presentation, the nodules were healing well. Given the patient’s travel history and physical examination, a presumptive diagnosis of furuncular myiasis from C anthropophaga also was made.

|

Comment

The term myiasis stems from the Greek term for fly and is used to describe the infestation of fly larvae in living vertebrates.1 Myiasis has many classifications, the 3 most common being furuncular, migratory, and wound myiasis, which are differentiated by the different fly species found in distinct regions of the world. Furuncular myiasis is the most benign form, usually affecting only a localized region of the skin; migratory myiasis is characterized by larvae traveling substantial distances from one anatomic site to another within the lower layers of the epidermis; and wound myiasis involves rapid reproduction of larvae in necrotic tissue with subsequent tissue destruction.2

The clinical presentation of the lesions noted in our patients suggested a diagnosis of furuncular myiasis, which commonly is caused by Dermatobia hominis, C anthropophaga, Cuterebra species, Wohlfahrtia vigil, and Wohlfahrtia opaca larvae.3Dermatobia hominis is the most common cause of furuncular myiasis and usually is found in Central and South America. Our patients likely developed an infestation of C anthropophaga (also known as the tumbu fly), a yellow-brown, 7- to 12-mm blowfly commonly found throughout tropical Africa.3 Although C anthropophaga is historically limited to sub-Saharan Africa, there has been a report of a case acquired in Portugal.4

In a review of the literature, C anthropophaga myiasis was documented in Italian travelers returning from Senegal5-7; our cases are unique because they represent North American travelers returning from Senegal with furuncular myiasis. Furuncular myiasis from C anthropophaga has been reported in travelers returning to North America from other African countries, including Angola,8 Tanzania,9-11 Kenya,9 Sierra Leone,12 and Ivory Coast.13 Several cases of ocular myiasis from D hominis and Oestrus ovis have been reported in European travelers returning from Tunisia.14,15

Tumbu fly infestations typically affect dogs and rodents but can arise in human hosts.3 Children may be affected by C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis more often than adults because they have thinner skin and less immunity to the larvae.2

|

There are 2 mechanisms by which infestation of human hosts by C anthropophaga can occur. Most commonly, female flies lay eggs in shady areas in soil that is contaminated by feces or urine. The hatched larvae can survive in the ground for up to 2 weeks and later attach to a host when prompted by heat or movement.3 Therefore, clothing set out to dry may be contaminated by this soil. Alternatively, female flies can lay eggs directly onto clothing that is contaminated by feces or urine and the larvae subsequently hatch outside the soil with easy access to human skin once the clothing is worn.2

Common penetration sites are the head, neck, and back, as well as areas covered by contaminated or infested clothing.2,3 Penetration of the human skin occurs instantly and is a painless process that is rarely noticed by the human host.3 The larvae burrow into the skin for 8 to 12 days, resulting in a furuncle that occasionally secretes a serous fluid.2 Within the first 2 days of infestation, the host may experience symptoms ranging from local pruritus to severe pain. Six days following initial onset, an intense inflammatory response may result in local lymphadenopathy along with fever and fatigue.2 The larvae use their posterior spiracles to create openings in the skin to create air holes that allow them to breathe.3 On physical examination, the spiracles generally appear as 1- to 3-mm dark linear streaks within furuncles, which is important in the diagnosis of C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis.1,3 If spiracles are not appreciated on initial examination, diagnosis can be made by submerging the affected areas in water or saliva to look for air bubbles arising from the central puncta of the lesions.1

All causes of furuncular myiasis are characterized by a ratio of 1 larva to 1 furuncle.16 Although most of these types of larvae that can cause furuncular myiasis result in single lesions, C anthropophaga infestation often produces several furuncles that may coalesce into plaques.1,2 The differential diagnosis for C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis includes pyoderma, impetigo, staphylococcal furunculosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, infected cyst, retained foreign body, and facticial disease.2,3 Dracunculiasis also may be considered, which occurs after ingestion of contaminated water.2 Ultrasonography may be helpful for the diagnosis of furuncular myiasis, as it can facilitate identification of foreign bodies, abscesses, and even larvae in some cases.17 Definitive diagnosis of any type of myiasis involves extraction of the larva and identification of the family, genus, and species by a parasitologist.1 Some experts suggest rearing preserved live larvae with raw meat after extraction because adult specimens are more reliable than larvae for species diagnosis.1

Treatment of furuncular myiasis involves occlusion and extraction of the larvae from the skin. Suffocation of the larvae by occlusion of air holes with petroleum jelly, paraffin oil, bacon fat, glue, and other obstructing substances forces the larvae to emerge in search of oxygen, though immature larvae may be more reluctant than mature ones.2,3 Definitive treatment involves the direct removal of the larvae by surgery or expulsion by pressure, though it is recommended that lesions are pretreated with occlusive techniques.1,3 Other reported methods of extraction include injection of lidocaine and the use of a commercial venom extractor.1 It should be noted that rupture and incomplete extraction of larvae can lead to secondary infections and allergic reactions. Lesions can be pretreated with lidocaine gel prior to extraction, and antibiotics should be used in cases of secondary bacterial infection. Ivermectin also has been reported as a treatment of furuncular myiasis and other types of myiasis.1 Prevention of infestation by C anthropophaga includes avoidance of endemic areas, maintaining good hygiene, and ironing clothing or drying it in sunny locations.1,2 Overall, furuncular myiasis has a good prognosis with rapid recovery and a low incidence of complications.1

Conclusion

We present 2 cases of travelers returning to North America from Senegal with C anthropophaga furuncular myiasis. Careful review of travel history, physical examination, and identification of fly larvae are important for diagnosis. Individuals traveling to sub-Saharan Africa should avoid drying clothes in shady places and lying on the ground. They also are urged to iron their clothing before wearing it.

1. Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

2. McGraw TA, Turiansky GW. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:907-926.

3. Robbins K, Khachemoune A. Cutaneous myiasis: a review of the common types of myiasis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1092-1098.

4. Curtis SJ, Edwards C, Athulathmuda C, et al. Case of the month: cutaneous myiasis in a returning traveller from the Algarve: first report of tumbu maggots, Cordylobia anthropophaga, acquired in Portugal. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:236-237.

5. Veraldi S, Brusasco A, Süss L. Cutaneous myiasis caused by larvae of Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard). Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:184-187.

6. Cultrera R, Dettori G, Calderaro A, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard 1872): description of 5 cases from costal regions of Senegal [in Italian]. Parassitologia. 1993;35:47-49.

7. Fusco FM, Nardiello S, Brancaccio G, et al. Cutaneous myiasis from Cordylobia anthropophaga in a traveller returning from Senegal: a case study [in Italian]. Infez Med. 2005;13:109-111.

8. Lee EJ, Robinson F. Furuncular myiasis of the face caused by larva of the tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga)[published online ahead of print July 21, 2006]. Eye (Lond). 2007;21:268-269.

9. Rice PL, Gleason N. Two cases of myiasis in the United States by the African tumbu fly, Cordylobia anthropophaga (Diptera, Calliphoridae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972;21:62-65.

10. March CH. A case of “ver du Cayor” in Manhattan. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:32-33.

11. Schorr WF. Tumbu-fly myiasis in Marshfield, Wis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:61-62.

12. Potter TS, Dorman MA, Ghaemi M, et al. Inflammatory papules on the back of a traveling businessman. tumbu

fly myiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:951, 954.

13. Ockenhouse CF, Samlaska CP, Benson PM, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:199-202.

14. Kaouech E, Kallel K, Belhadj S, et al. Dermatobia hominis furuncular myiasis in a man returning from Latin America: first imported case in Tunisia [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2010;70:135-136.

15. Zayani A, Chaabouni M, Gouiaa R, et al. Conjuctival myiasis. 23 cases in the Tunisian Sahel [in French]. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1989;66:289-292.

16. Latorre M, Ullate JV, Sanchez J, et al. A case of myiasis due to Dermatobia hominis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:968-969.

17. Mahal JJ, Sperling JD. Furuncular myiasis from Dermatobia hominis: a case of human botfly infestation [published online ahead of print February 1, 2010]. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:618-621.

1. Caissie R, Beaulieu F, Giroux M, et al. Cutaneous myiasis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:560-568.

2. McGraw TA, Turiansky GW. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:907-926.

3. Robbins K, Khachemoune A. Cutaneous myiasis: a review of the common types of myiasis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1092-1098.

4. Curtis SJ, Edwards C, Athulathmuda C, et al. Case of the month: cutaneous myiasis in a returning traveller from the Algarve: first report of tumbu maggots, Cordylobia anthropophaga, acquired in Portugal. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:236-237.

5. Veraldi S, Brusasco A, Süss L. Cutaneous myiasis caused by larvae of Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard). Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:184-187.

6. Cultrera R, Dettori G, Calderaro A, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard 1872): description of 5 cases from costal regions of Senegal [in Italian]. Parassitologia. 1993;35:47-49.

7. Fusco FM, Nardiello S, Brancaccio G, et al. Cutaneous myiasis from Cordylobia anthropophaga in a traveller returning from Senegal: a case study [in Italian]. Infez Med. 2005;13:109-111.

8. Lee EJ, Robinson F. Furuncular myiasis of the face caused by larva of the tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga)[published online ahead of print July 21, 2006]. Eye (Lond). 2007;21:268-269.

9. Rice PL, Gleason N. Two cases of myiasis in the United States by the African tumbu fly, Cordylobia anthropophaga (Diptera, Calliphoridae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972;21:62-65.

10. March CH. A case of “ver du Cayor” in Manhattan. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:32-33.

11. Schorr WF. Tumbu-fly myiasis in Marshfield, Wis. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:61-62.

12. Potter TS, Dorman MA, Ghaemi M, et al. Inflammatory papules on the back of a traveling businessman. tumbu

fly myiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:951, 954.

13. Ockenhouse CF, Samlaska CP, Benson PM, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:199-202.

14. Kaouech E, Kallel K, Belhadj S, et al. Dermatobia hominis furuncular myiasis in a man returning from Latin America: first imported case in Tunisia [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2010;70:135-136.

15. Zayani A, Chaabouni M, Gouiaa R, et al. Conjuctival myiasis. 23 cases in the Tunisian Sahel [in French]. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1989;66:289-292.

16. Latorre M, Ullate JV, Sanchez J, et al. A case of myiasis due to Dermatobia hominis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:968-969.

17. Mahal JJ, Sperling JD. Furuncular myiasis from Dermatobia hominis: a case of human botfly infestation [published online ahead of print February 1, 2010]. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:618-621.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous myiasis is caused by an infestation of fly larvae and can present as furuncles (furuncular myiasis), migratory inflammatory linear plaques (migratory myiasis), and worsening tissue destruction in existing wounds (wound myiasis).

- Furuncular myiasis should be included in the differential diagnosis in patients with furuncular skin lesions who have recently traveled to Central America, South America, or sub-Saharan Africa.

- Furuncular myiasis may be treated by both occlusive and extraction techniques.

Spontaneously Regressing Primary Nodular Melanoma of the Glans Penis

To the Editor:

Primary malignant melanoma (PMM) of the penis is rare, comprising 1% of melanomas overall and less than 4% of malignancies in the male genitourinary tract.1 However, regression of PMM is not rare. Melanoma is 6 times more likely to undergo regression compared to other malignancies.2 Approximately 10% to 35% of cutaneous PMMs undergo partial regression, but only 42 cases of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs have been reported,3,4 which may be due to underreporting of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs, as they often are clinically inconspicuous. Additionally, completely regressed cutaneous PMMs may be incorrectly reported as metastatic melanoma of unknown primary.5 Clinical characteristics of regression include pink coloration and a lightening or whitening of baseline lesional color. Dermatoscopic features of regression include white areas, blue areas, or vascular structures that translate microscopically to dermal fibrosis, melanophages, and telangiectases.5 We report a case of complete clinical regression of a nodular, mucosal, penile PMM with no evidence of metastatic disease.

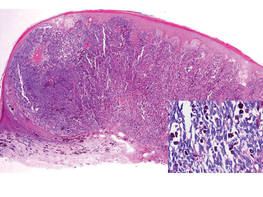

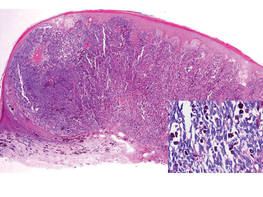

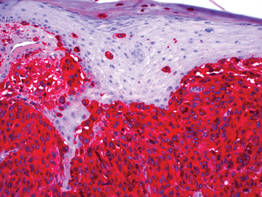

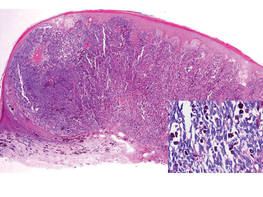

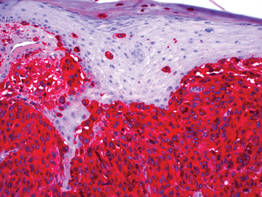

An 86-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, pigmented lesion on the glans penis of 2 years’ duration. His medical history was notable for retinal detachment, macular degeneration, lumbar stenosis, and seizures postneurosurgery for a subdural hematoma. Physical examination revealed a healthy man with a mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis (Figure 1). No other similar skin lesions or lymphadenopathy were detectable. A lesional deep shave biopsy obtained at presentation demonstrated a nodular-type malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis. |

|

| Figure 2. Histologic section showed a nodular melanocytic proliferation with a dense sheetlike collection of melanocytes, predominantly in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×20). Prominent cytologic atypia and multiple mitotic figures were consistent with melanoma (inset)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

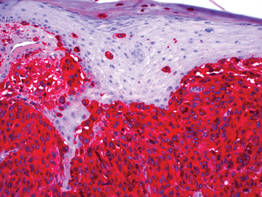

| Figure 3. High-power view of HMB-45 stain showed strong and diffuse staining, including several pagetoid intraepidermal melanocytes (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 4. Skin examination 8 years following the initial primary malignant melanoma diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent or metastatic melanoma and almost complete loss of pigmentation at the prior melanoma site. |

Histologic examination showed nodular nests of malignant melanocytes that were dispersed along the dermal-epidermal junction and coalesced into sheets within the dermis. Numerous dermal mitoses were present. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive with Melan-A and HMB-45, which also highlighted scattered pagetoid intraepidermal cells (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of PMM of the mucocutaneous glans penis. The tumor was nonulcerated and invaded to a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm, corresponding to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIA (T3aN0M0) with an expected 5-year survival rate of 79%.6

He was referred to the urology department and was offered cystoscopy, urethrography, and phallectomy, which he refused. He also refused a trial of imiquimod. Computed tomography (CT) scans of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for metastatic disease. Following the initial melanoma diagnosis, he had yearly dermatologic evaluations consisting of total-body skin and lymph node (LN) examinations. At 87 years of age (1 year following the initial diagnosis), the melanoma became dramatically smaller. At 88 years of age (2 years after diagnosis), the melanoma had near-complete clinical resolution. At 89 years of age, the patient reported asymmetric hearing loss. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging study showed no evidence of metastases.

At 92 years of age (6 years after the initial diagnosis), the patient reported bilateral leg pain. A CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no evidence of metastasis. He also reported abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ileocecal mass. Biopsy of the ileocecal mass showed moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma and no evidence of metastatic melanoma. The adenocarcinoma was resected and he continues to do well. Skin and LN examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent penile mucosal melanoma or metastatic melanoma (Figure 4). The PMM appeared to have clinically regressed spontaneously. He refused repeat skin biopsy and additional imaging studies.

The criteria for complete melanoma regression were initially described in 19657 and revised in 2005.2 Although our patient demonstrated complete clinical regression of his PMM, he did not meet the revised criteria for complete regression because there was no histopathologic confirmation of regression or of the absence of melanoma as well as no lymphatic involvement. It is extremely difficult to quantify the percentage of PMMs that completely regress. A case of a completely regressed untreated PMM with no metastatic disease 4 years after diagnosis has been reported. This case involved a nonulcerated melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA).4 The prognosis of penile mucosal PMM is comparable to that of cutaneous PMM with a similar Breslow thickness.1

The prognostic significance of melanoma regression is controversial. Regression may be mediated by host immunity, apoptosis, and/or antiangiogenesis. The lymphocytic infiltrate in regressive melanomas consists of cytotoxic T cells with selective antitumor activity, which induces HLA class I–restricted melanoma lysis.8 Lymph node migration may result in T-lymphocyte priming and induction of antitumor immunity.9 Therefore, regression may indicate risk for sentinel LN metastasis.

It is possible that complete regression of melanoma does not truly exist, and late recurrence due to cancer dormancy is inevitable. Late recurrence is defined as first metastasis 10 years after complete removal of the PMM.10 Our patient has only been followed for 8 years, so this possibility cannot be entirely excluded.

1. van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: a series of 19 Dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology. 2007;70:143-147.

2. High WA, Stewart D, Wilbers CR, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with nodal and/or visceral metastases: a report of 5 cases and assessment of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:89-100.

3. Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

4. Muniesa C, Ferreres JR, Moreno A, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with metastases [published online ahead of print June 23, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:327-328.

5. Bories N, Dalle S, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy of fully regressive cutaneous melanoma [published online ahead of print March 13, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1224-1229.

6. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

7. Smith JL Jr, Stehlin JS Jr. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanomas with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399-1415.

8. Bottger D, Dowden RV, Kay PP. Complete spontaneous regression of cutaneous primary malignant melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:548-553.

9. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1989;15:257-265.

10. Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Haroske G, et al. Late recurrence (10 years or more) of malignant melanoma in south-east Germany (Saxony). a single-centre analysis of 1881 patients with a follow-up of 10 years or more [published online ahead of print January 11, 2010]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:833-836.

To the Editor:

Primary malignant melanoma (PMM) of the penis is rare, comprising 1% of melanomas overall and less than 4% of malignancies in the male genitourinary tract.1 However, regression of PMM is not rare. Melanoma is 6 times more likely to undergo regression compared to other malignancies.2 Approximately 10% to 35% of cutaneous PMMs undergo partial regression, but only 42 cases of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs have been reported,3,4 which may be due to underreporting of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs, as they often are clinically inconspicuous. Additionally, completely regressed cutaneous PMMs may be incorrectly reported as metastatic melanoma of unknown primary.5 Clinical characteristics of regression include pink coloration and a lightening or whitening of baseline lesional color. Dermatoscopic features of regression include white areas, blue areas, or vascular structures that translate microscopically to dermal fibrosis, melanophages, and telangiectases.5 We report a case of complete clinical regression of a nodular, mucosal, penile PMM with no evidence of metastatic disease.

An 86-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, pigmented lesion on the glans penis of 2 years’ duration. His medical history was notable for retinal detachment, macular degeneration, lumbar stenosis, and seizures postneurosurgery for a subdural hematoma. Physical examination revealed a healthy man with a mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis (Figure 1). No other similar skin lesions or lymphadenopathy were detectable. A lesional deep shave biopsy obtained at presentation demonstrated a nodular-type malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis. |

|

| Figure 2. Histologic section showed a nodular melanocytic proliferation with a dense sheetlike collection of melanocytes, predominantly in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×20). Prominent cytologic atypia and multiple mitotic figures were consistent with melanoma (inset)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 3. High-power view of HMB-45 stain showed strong and diffuse staining, including several pagetoid intraepidermal melanocytes (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 4. Skin examination 8 years following the initial primary malignant melanoma diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent or metastatic melanoma and almost complete loss of pigmentation at the prior melanoma site. |

Histologic examination showed nodular nests of malignant melanocytes that were dispersed along the dermal-epidermal junction and coalesced into sheets within the dermis. Numerous dermal mitoses were present. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive with Melan-A and HMB-45, which also highlighted scattered pagetoid intraepidermal cells (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of PMM of the mucocutaneous glans penis. The tumor was nonulcerated and invaded to a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm, corresponding to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIA (T3aN0M0) with an expected 5-year survival rate of 79%.6

He was referred to the urology department and was offered cystoscopy, urethrography, and phallectomy, which he refused. He also refused a trial of imiquimod. Computed tomography (CT) scans of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for metastatic disease. Following the initial melanoma diagnosis, he had yearly dermatologic evaluations consisting of total-body skin and lymph node (LN) examinations. At 87 years of age (1 year following the initial diagnosis), the melanoma became dramatically smaller. At 88 years of age (2 years after diagnosis), the melanoma had near-complete clinical resolution. At 89 years of age, the patient reported asymmetric hearing loss. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging study showed no evidence of metastases.

At 92 years of age (6 years after the initial diagnosis), the patient reported bilateral leg pain. A CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no evidence of metastasis. He also reported abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ileocecal mass. Biopsy of the ileocecal mass showed moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma and no evidence of metastatic melanoma. The adenocarcinoma was resected and he continues to do well. Skin and LN examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent penile mucosal melanoma or metastatic melanoma (Figure 4). The PMM appeared to have clinically regressed spontaneously. He refused repeat skin biopsy and additional imaging studies.

The criteria for complete melanoma regression were initially described in 19657 and revised in 2005.2 Although our patient demonstrated complete clinical regression of his PMM, he did not meet the revised criteria for complete regression because there was no histopathologic confirmation of regression or of the absence of melanoma as well as no lymphatic involvement. It is extremely difficult to quantify the percentage of PMMs that completely regress. A case of a completely regressed untreated PMM with no metastatic disease 4 years after diagnosis has been reported. This case involved a nonulcerated melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA).4 The prognosis of penile mucosal PMM is comparable to that of cutaneous PMM with a similar Breslow thickness.1

The prognostic significance of melanoma regression is controversial. Regression may be mediated by host immunity, apoptosis, and/or antiangiogenesis. The lymphocytic infiltrate in regressive melanomas consists of cytotoxic T cells with selective antitumor activity, which induces HLA class I–restricted melanoma lysis.8 Lymph node migration may result in T-lymphocyte priming and induction of antitumor immunity.9 Therefore, regression may indicate risk for sentinel LN metastasis.

It is possible that complete regression of melanoma does not truly exist, and late recurrence due to cancer dormancy is inevitable. Late recurrence is defined as first metastasis 10 years after complete removal of the PMM.10 Our patient has only been followed for 8 years, so this possibility cannot be entirely excluded.

To the Editor:

Primary malignant melanoma (PMM) of the penis is rare, comprising 1% of melanomas overall and less than 4% of malignancies in the male genitourinary tract.1 However, regression of PMM is not rare. Melanoma is 6 times more likely to undergo regression compared to other malignancies.2 Approximately 10% to 35% of cutaneous PMMs undergo partial regression, but only 42 cases of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs have been reported,3,4 which may be due to underreporting of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs, as they often are clinically inconspicuous. Additionally, completely regressed cutaneous PMMs may be incorrectly reported as metastatic melanoma of unknown primary.5 Clinical characteristics of regression include pink coloration and a lightening or whitening of baseline lesional color. Dermatoscopic features of regression include white areas, blue areas, or vascular structures that translate microscopically to dermal fibrosis, melanophages, and telangiectases.5 We report a case of complete clinical regression of a nodular, mucosal, penile PMM with no evidence of metastatic disease.

An 86-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, pigmented lesion on the glans penis of 2 years’ duration. His medical history was notable for retinal detachment, macular degeneration, lumbar stenosis, and seizures postneurosurgery for a subdural hematoma. Physical examination revealed a healthy man with a mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis (Figure 1). No other similar skin lesions or lymphadenopathy were detectable. A lesional deep shave biopsy obtained at presentation demonstrated a nodular-type malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis. |

|

| Figure 2. Histologic section showed a nodular melanocytic proliferation with a dense sheetlike collection of melanocytes, predominantly in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×20). Prominent cytologic atypia and multiple mitotic figures were consistent with melanoma (inset)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 3. High-power view of HMB-45 stain showed strong and diffuse staining, including several pagetoid intraepidermal melanocytes (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 4. Skin examination 8 years following the initial primary malignant melanoma diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent or metastatic melanoma and almost complete loss of pigmentation at the prior melanoma site. |

Histologic examination showed nodular nests of malignant melanocytes that were dispersed along the dermal-epidermal junction and coalesced into sheets within the dermis. Numerous dermal mitoses were present. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive with Melan-A and HMB-45, which also highlighted scattered pagetoid intraepidermal cells (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of PMM of the mucocutaneous glans penis. The tumor was nonulcerated and invaded to a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm, corresponding to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIA (T3aN0M0) with an expected 5-year survival rate of 79%.6

He was referred to the urology department and was offered cystoscopy, urethrography, and phallectomy, which he refused. He also refused a trial of imiquimod. Computed tomography (CT) scans of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for metastatic disease. Following the initial melanoma diagnosis, he had yearly dermatologic evaluations consisting of total-body skin and lymph node (LN) examinations. At 87 years of age (1 year following the initial diagnosis), the melanoma became dramatically smaller. At 88 years of age (2 years after diagnosis), the melanoma had near-complete clinical resolution. At 89 years of age, the patient reported asymmetric hearing loss. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging study showed no evidence of metastases.

At 92 years of age (6 years after the initial diagnosis), the patient reported bilateral leg pain. A CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no evidence of metastasis. He also reported abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ileocecal mass. Biopsy of the ileocecal mass showed moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma and no evidence of metastatic melanoma. The adenocarcinoma was resected and he continues to do well. Skin and LN examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent penile mucosal melanoma or metastatic melanoma (Figure 4). The PMM appeared to have clinically regressed spontaneously. He refused repeat skin biopsy and additional imaging studies.

The criteria for complete melanoma regression were initially described in 19657 and revised in 2005.2 Although our patient demonstrated complete clinical regression of his PMM, he did not meet the revised criteria for complete regression because there was no histopathologic confirmation of regression or of the absence of melanoma as well as no lymphatic involvement. It is extremely difficult to quantify the percentage of PMMs that completely regress. A case of a completely regressed untreated PMM with no metastatic disease 4 years after diagnosis has been reported. This case involved a nonulcerated melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA).4 The prognosis of penile mucosal PMM is comparable to that of cutaneous PMM with a similar Breslow thickness.1

The prognostic significance of melanoma regression is controversial. Regression may be mediated by host immunity, apoptosis, and/or antiangiogenesis. The lymphocytic infiltrate in regressive melanomas consists of cytotoxic T cells with selective antitumor activity, which induces HLA class I–restricted melanoma lysis.8 Lymph node migration may result in T-lymphocyte priming and induction of antitumor immunity.9 Therefore, regression may indicate risk for sentinel LN metastasis.

It is possible that complete regression of melanoma does not truly exist, and late recurrence due to cancer dormancy is inevitable. Late recurrence is defined as first metastasis 10 years after complete removal of the PMM.10 Our patient has only been followed for 8 years, so this possibility cannot be entirely excluded.

1. van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: a series of 19 Dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology. 2007;70:143-147.

2. High WA, Stewart D, Wilbers CR, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with nodal and/or visceral metastases: a report of 5 cases and assessment of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:89-100.

3. Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

4. Muniesa C, Ferreres JR, Moreno A, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with metastases [published online ahead of print June 23, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:327-328.

5. Bories N, Dalle S, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy of fully regressive cutaneous melanoma [published online ahead of print March 13, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1224-1229.

6. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

7. Smith JL Jr, Stehlin JS Jr. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanomas with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399-1415.

8. Bottger D, Dowden RV, Kay PP. Complete spontaneous regression of cutaneous primary malignant melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:548-553.

9. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1989;15:257-265.

10. Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Haroske G, et al. Late recurrence (10 years or more) of malignant melanoma in south-east Germany (Saxony). a single-centre analysis of 1881 patients with a follow-up of 10 years or more [published online ahead of print January 11, 2010]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:833-836.

1. van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: a series of 19 Dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology. 2007;70:143-147.

2. High WA, Stewart D, Wilbers CR, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with nodal and/or visceral metastases: a report of 5 cases and assessment of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:89-100.

3. Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

4. Muniesa C, Ferreres JR, Moreno A, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with metastases [published online ahead of print June 23, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:327-328.

5. Bories N, Dalle S, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy of fully regressive cutaneous melanoma [published online ahead of print March 13, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1224-1229.

6. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

7. Smith JL Jr, Stehlin JS Jr. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanomas with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399-1415.

8. Bottger D, Dowden RV, Kay PP. Complete spontaneous regression of cutaneous primary malignant melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:548-553.

9. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1989;15:257-265.

10. Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Haroske G, et al. Late recurrence (10 years or more) of malignant melanoma in south-east Germany (Saxony). a single-centre analysis of 1881 patients with a follow-up of 10 years or more [published online ahead of print January 11, 2010]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:833-836.