User login

Chronic Cribriform Ulcerated Plaque on the Left Calf

The Diagnosis: Nodular Basal Cell Carcinoma

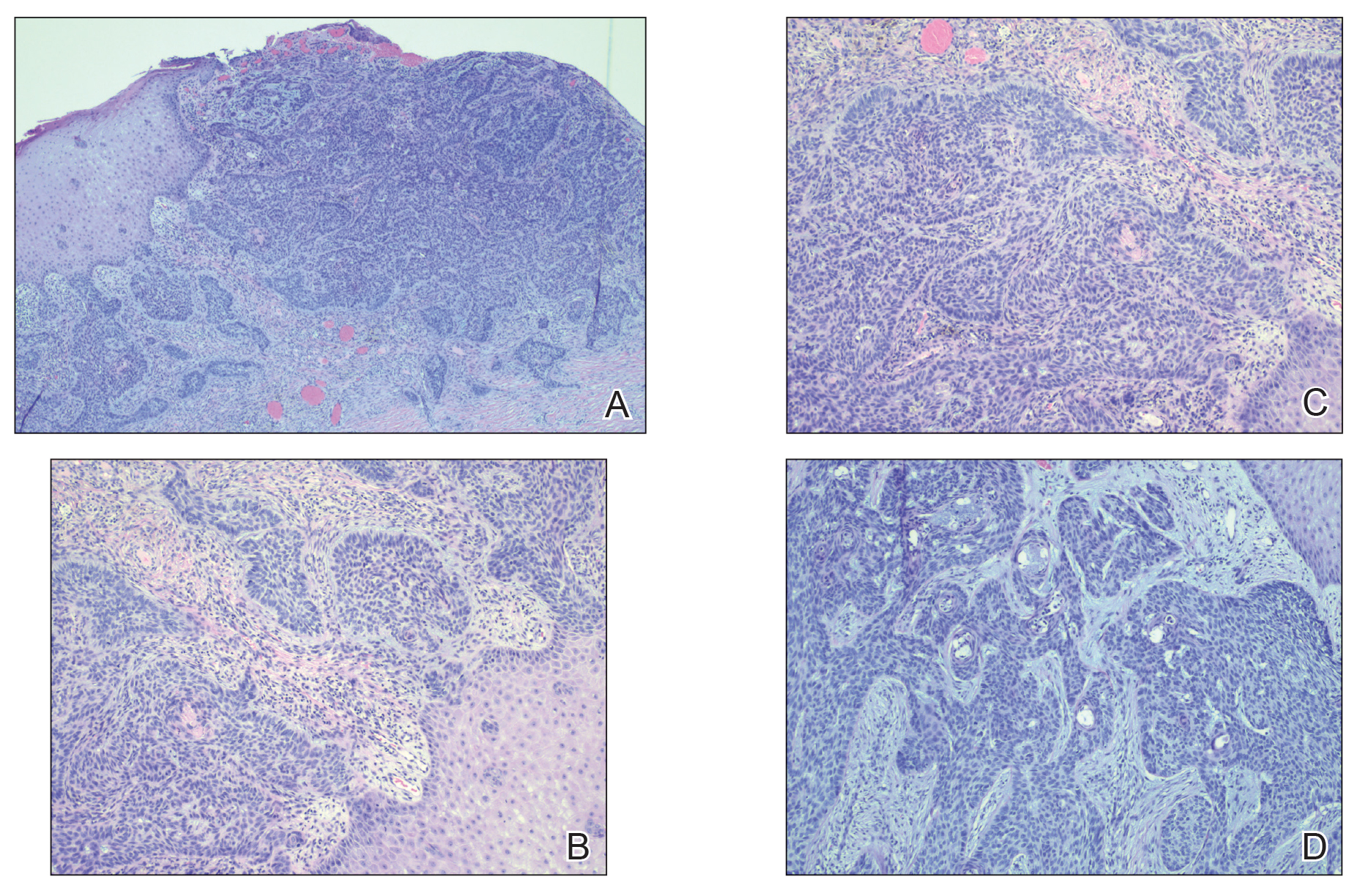

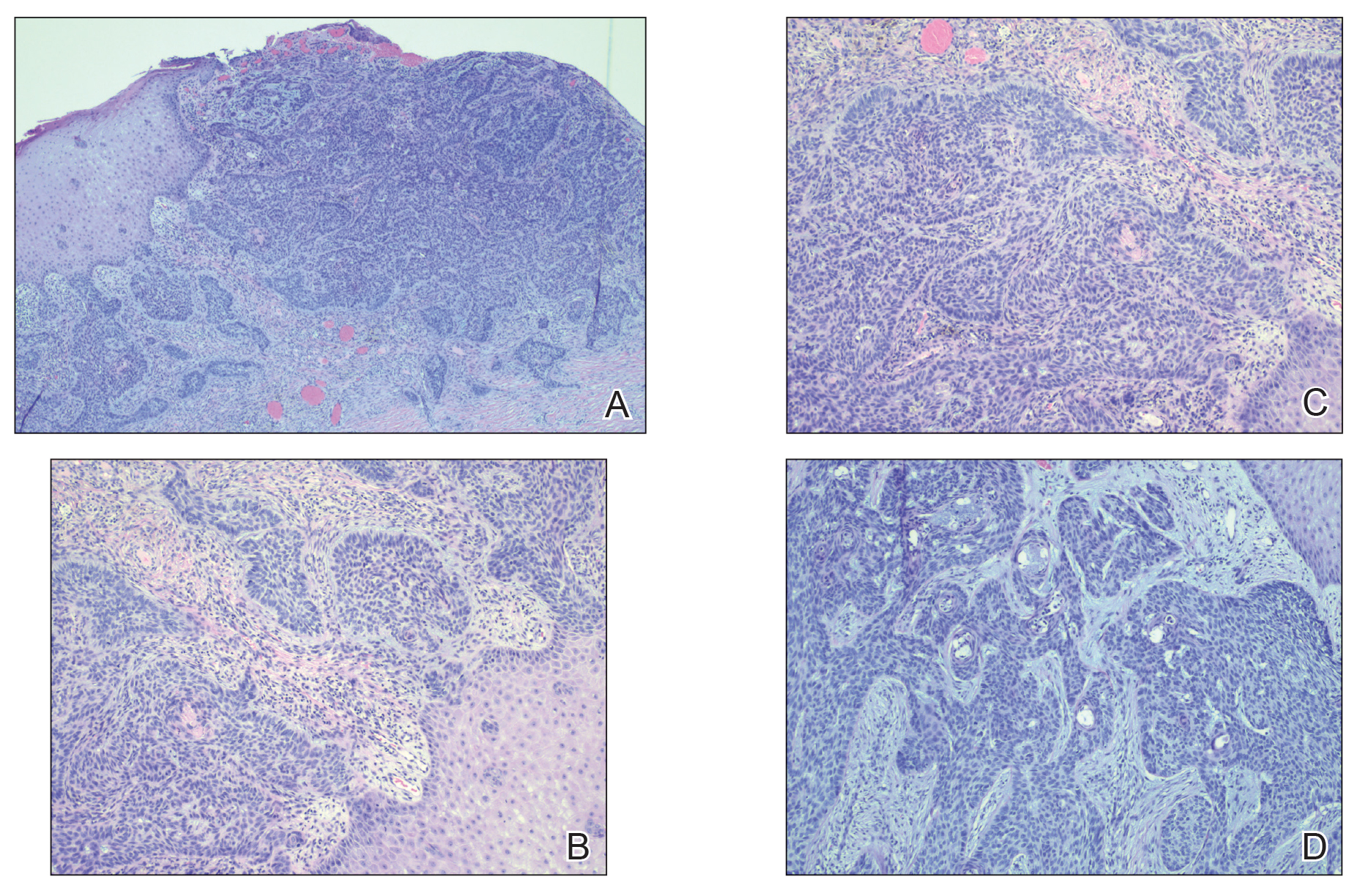

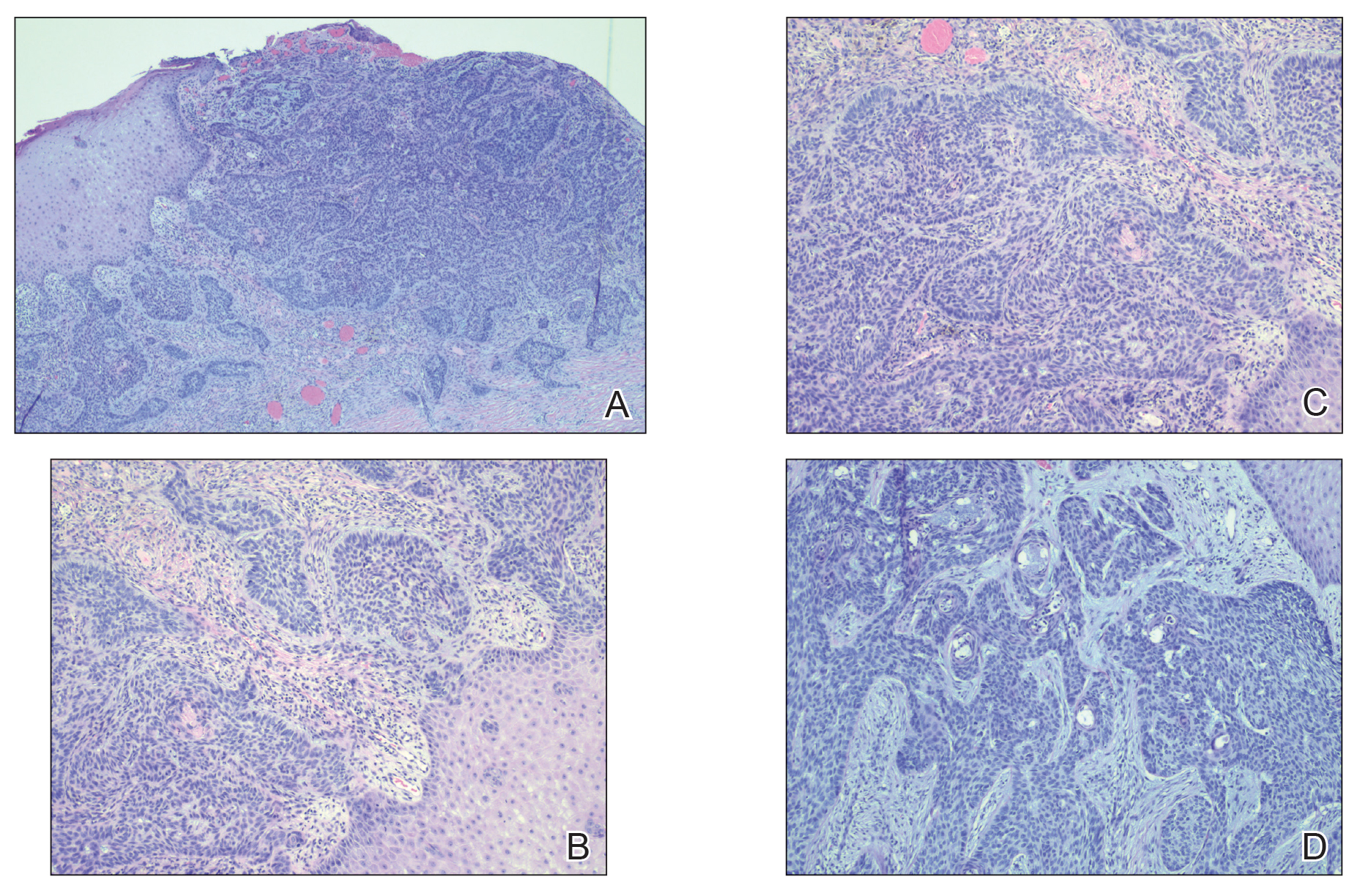

Histopathology of the lesion showed a large basaloid lobule with focal epidermal attachment, peripheral nuclear palisading with cleft formation between the tumor and surrounding stroma, fibromyxoid stroma and mild pleomorphism, and variable mitotic activity and apoptosis (Figure). Based on the clinical presentation and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). He underwent a wide local excision of the affected area that was repaired with a splitthickness skin graft.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer worldwide and typically occurs due to years of UV radiation damage on sun-exposed skin, which accounts for a higher frequency of BCC occurring in patients residing in geographic locations with greater UV exposure (eg, higher and lower latitudes). In addition to cumulative UV dose, the duration of the exposure as well as its intensity also play a role in the development of BCC, particularly in early childhood and adolescence. Nevertheless, UV exposure is not the only risk factor, as 20% of BCCs arise in skin that is not exposed to the sun. Other risk factors include exposure to ionizing radiation and arsenic, immunosuppression, and genetic predisposition.1 Although these malignancies typically do not metastasize, growth can lead to local tissue destruction and major disfigurement if not treated in a timely fashion.2

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) given the clinical appearance of the cribriform base and violaceous undermined rim of the ulcer. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare neutrophilic disorder that often results in ulcers that have been associated with various systemic autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. There are 4 main subtypes of PG: the classic ulcerative type (our patient); the pustular type, which most often is seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; the bullous type, which can be seen in patients with an associated lymphoproliferative disorder; and the vegetative type. It frequently is thought of as both a clinical and histologic diagnosis of exclusion due to the nonspecific histopathologic features; most lesions demonstrate an infiltrate of neutrophils in the dermis. A biopsy was crucial in our patient, considering that diagnosis and treatment would have been further delayed had the patient been empirically treated with oral and topical steroids for presumed PG, which is precisely why PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is imperative for clinicians to rule out other pathologies, such as infection or malignancy, as demonstrated in our patient. The progressive onset and slow evolution of the lesion over years along with a lack of pain were more suggestive of BCC rather than PG. However, there is a report in the literature of PG mimicking BCC with both clinical and dermoscopic findings.3

Venous or stasis ulcers are painless, and although they rarely occur on the calf, they typically are seen lower on the leg such as on the medial ankles. Our patient endorsed occasional swelling of the affected leg and presented with edema, but overlying stasis change and other signs of venous insufficiency were absent.

Buruli ulcer is a painless chronic debilitating cutaneous disease resulting in indolent necrotizing skin as well as subcutaneous and bone lesions. It is caused by the environmental organism Mycobacterium ulcerans and typically is reported in Africa, Central/South America, the Western Pacific Region, and Australia.4 Histopathology usually demonstrates necrosis of subcutaneous tissue and dermal collagen accompanied by inflammation and acidfast bacilli highlighted by Ziehl-Neelsen stain.5 Smears of the lesions as well as culture and polymerase chain reaction for acid-fast bacilli also can be performed. Our patient reported no recent travel to any endemic areas and had no other risk factors or exposures to the pathogen responsible for this condition.

Traumatic ulcer also was included in the differential diagnosis, but the patient denied preceding trauma to the area, and the contralateral foot prosthesis did not rub on or impact the affected leg.

Basal cell carcinoma typically is treated surgically, but choice of treatment can depend on the subtype, size, tumor site, and/or patient preference.1 Other treatment modalities include electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgical destruction, photodynamic therapy, radiation, topical therapies, and systemic medications. Radiotherapy can be considered as a primary treatment option for BCC if surgery is contraindicated or declined by the patient, but it also is useful as an adjuvant therapy when there is perineural invasion of the tumor or positive margins. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors such as vismodegib currently are indicated for patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation as well as for those with metastatic or locally advanced, recurrent BCC. There is no single treatment method ideal for every lesion or patient. Specific populations such as the elderly, the immunosuppressed, or those with poor baseline functional status may warrant a nonsurgical approach. The clinician must take into consideration all factors while at the same time thinking about how to best accomplish the goals of recurrencefree tumor removal, correction of any underlying functional impairment from the tumor, and maintenance of cosmesis.1

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls; 2022.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Rosina P, Papagrigoraki A, Colato C. A case of superficial granulomatous pyoderma mimicking a basal cell carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:48-51.

- Yotsu RR, Suzuki K, Simmonds RE, et al. Buruli ulcer: a review of the current knowledge. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:247-256.

- Guarner J, Bartlett J, Whitney EA, et al. Histopathologic features of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:651-656.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Basal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology of the lesion showed a large basaloid lobule with focal epidermal attachment, peripheral nuclear palisading with cleft formation between the tumor and surrounding stroma, fibromyxoid stroma and mild pleomorphism, and variable mitotic activity and apoptosis (Figure). Based on the clinical presentation and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). He underwent a wide local excision of the affected area that was repaired with a splitthickness skin graft.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer worldwide and typically occurs due to years of UV radiation damage on sun-exposed skin, which accounts for a higher frequency of BCC occurring in patients residing in geographic locations with greater UV exposure (eg, higher and lower latitudes). In addition to cumulative UV dose, the duration of the exposure as well as its intensity also play a role in the development of BCC, particularly in early childhood and adolescence. Nevertheless, UV exposure is not the only risk factor, as 20% of BCCs arise in skin that is not exposed to the sun. Other risk factors include exposure to ionizing radiation and arsenic, immunosuppression, and genetic predisposition.1 Although these malignancies typically do not metastasize, growth can lead to local tissue destruction and major disfigurement if not treated in a timely fashion.2

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) given the clinical appearance of the cribriform base and violaceous undermined rim of the ulcer. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare neutrophilic disorder that often results in ulcers that have been associated with various systemic autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. There are 4 main subtypes of PG: the classic ulcerative type (our patient); the pustular type, which most often is seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; the bullous type, which can be seen in patients with an associated lymphoproliferative disorder; and the vegetative type. It frequently is thought of as both a clinical and histologic diagnosis of exclusion due to the nonspecific histopathologic features; most lesions demonstrate an infiltrate of neutrophils in the dermis. A biopsy was crucial in our patient, considering that diagnosis and treatment would have been further delayed had the patient been empirically treated with oral and topical steroids for presumed PG, which is precisely why PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is imperative for clinicians to rule out other pathologies, such as infection or malignancy, as demonstrated in our patient. The progressive onset and slow evolution of the lesion over years along with a lack of pain were more suggestive of BCC rather than PG. However, there is a report in the literature of PG mimicking BCC with both clinical and dermoscopic findings.3

Venous or stasis ulcers are painless, and although they rarely occur on the calf, they typically are seen lower on the leg such as on the medial ankles. Our patient endorsed occasional swelling of the affected leg and presented with edema, but overlying stasis change and other signs of venous insufficiency were absent.

Buruli ulcer is a painless chronic debilitating cutaneous disease resulting in indolent necrotizing skin as well as subcutaneous and bone lesions. It is caused by the environmental organism Mycobacterium ulcerans and typically is reported in Africa, Central/South America, the Western Pacific Region, and Australia.4 Histopathology usually demonstrates necrosis of subcutaneous tissue and dermal collagen accompanied by inflammation and acidfast bacilli highlighted by Ziehl-Neelsen stain.5 Smears of the lesions as well as culture and polymerase chain reaction for acid-fast bacilli also can be performed. Our patient reported no recent travel to any endemic areas and had no other risk factors or exposures to the pathogen responsible for this condition.

Traumatic ulcer also was included in the differential diagnosis, but the patient denied preceding trauma to the area, and the contralateral foot prosthesis did not rub on or impact the affected leg.

Basal cell carcinoma typically is treated surgically, but choice of treatment can depend on the subtype, size, tumor site, and/or patient preference.1 Other treatment modalities include electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgical destruction, photodynamic therapy, radiation, topical therapies, and systemic medications. Radiotherapy can be considered as a primary treatment option for BCC if surgery is contraindicated or declined by the patient, but it also is useful as an adjuvant therapy when there is perineural invasion of the tumor or positive margins. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors such as vismodegib currently are indicated for patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation as well as for those with metastatic or locally advanced, recurrent BCC. There is no single treatment method ideal for every lesion or patient. Specific populations such as the elderly, the immunosuppressed, or those with poor baseline functional status may warrant a nonsurgical approach. The clinician must take into consideration all factors while at the same time thinking about how to best accomplish the goals of recurrencefree tumor removal, correction of any underlying functional impairment from the tumor, and maintenance of cosmesis.1

The Diagnosis: Nodular Basal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology of the lesion showed a large basaloid lobule with focal epidermal attachment, peripheral nuclear palisading with cleft formation between the tumor and surrounding stroma, fibromyxoid stroma and mild pleomorphism, and variable mitotic activity and apoptosis (Figure). Based on the clinical presentation and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). He underwent a wide local excision of the affected area that was repaired with a splitthickness skin graft.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer worldwide and typically occurs due to years of UV radiation damage on sun-exposed skin, which accounts for a higher frequency of BCC occurring in patients residing in geographic locations with greater UV exposure (eg, higher and lower latitudes). In addition to cumulative UV dose, the duration of the exposure as well as its intensity also play a role in the development of BCC, particularly in early childhood and adolescence. Nevertheless, UV exposure is not the only risk factor, as 20% of BCCs arise in skin that is not exposed to the sun. Other risk factors include exposure to ionizing radiation and arsenic, immunosuppression, and genetic predisposition.1 Although these malignancies typically do not metastasize, growth can lead to local tissue destruction and major disfigurement if not treated in a timely fashion.2

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) given the clinical appearance of the cribriform base and violaceous undermined rim of the ulcer. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare neutrophilic disorder that often results in ulcers that have been associated with various systemic autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. There are 4 main subtypes of PG: the classic ulcerative type (our patient); the pustular type, which most often is seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; the bullous type, which can be seen in patients with an associated lymphoproliferative disorder; and the vegetative type. It frequently is thought of as both a clinical and histologic diagnosis of exclusion due to the nonspecific histopathologic features; most lesions demonstrate an infiltrate of neutrophils in the dermis. A biopsy was crucial in our patient, considering that diagnosis and treatment would have been further delayed had the patient been empirically treated with oral and topical steroids for presumed PG, which is precisely why PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is imperative for clinicians to rule out other pathologies, such as infection or malignancy, as demonstrated in our patient. The progressive onset and slow evolution of the lesion over years along with a lack of pain were more suggestive of BCC rather than PG. However, there is a report in the literature of PG mimicking BCC with both clinical and dermoscopic findings.3

Venous or stasis ulcers are painless, and although they rarely occur on the calf, they typically are seen lower on the leg such as on the medial ankles. Our patient endorsed occasional swelling of the affected leg and presented with edema, but overlying stasis change and other signs of venous insufficiency were absent.

Buruli ulcer is a painless chronic debilitating cutaneous disease resulting in indolent necrotizing skin as well as subcutaneous and bone lesions. It is caused by the environmental organism Mycobacterium ulcerans and typically is reported in Africa, Central/South America, the Western Pacific Region, and Australia.4 Histopathology usually demonstrates necrosis of subcutaneous tissue and dermal collagen accompanied by inflammation and acidfast bacilli highlighted by Ziehl-Neelsen stain.5 Smears of the lesions as well as culture and polymerase chain reaction for acid-fast bacilli also can be performed. Our patient reported no recent travel to any endemic areas and had no other risk factors or exposures to the pathogen responsible for this condition.

Traumatic ulcer also was included in the differential diagnosis, but the patient denied preceding trauma to the area, and the contralateral foot prosthesis did not rub on or impact the affected leg.

Basal cell carcinoma typically is treated surgically, but choice of treatment can depend on the subtype, size, tumor site, and/or patient preference.1 Other treatment modalities include electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgical destruction, photodynamic therapy, radiation, topical therapies, and systemic medications. Radiotherapy can be considered as a primary treatment option for BCC if surgery is contraindicated or declined by the patient, but it also is useful as an adjuvant therapy when there is perineural invasion of the tumor or positive margins. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors such as vismodegib currently are indicated for patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation as well as for those with metastatic or locally advanced, recurrent BCC. There is no single treatment method ideal for every lesion or patient. Specific populations such as the elderly, the immunosuppressed, or those with poor baseline functional status may warrant a nonsurgical approach. The clinician must take into consideration all factors while at the same time thinking about how to best accomplish the goals of recurrencefree tumor removal, correction of any underlying functional impairment from the tumor, and maintenance of cosmesis.1

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls; 2022.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Rosina P, Papagrigoraki A, Colato C. A case of superficial granulomatous pyoderma mimicking a basal cell carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:48-51.

- Yotsu RR, Suzuki K, Simmonds RE, et al. Buruli ulcer: a review of the current knowledge. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:247-256.

- Guarner J, Bartlett J, Whitney EA, et al. Histopathologic features of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:651-656.

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls; 2022.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Rosina P, Papagrigoraki A, Colato C. A case of superficial granulomatous pyoderma mimicking a basal cell carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:48-51.

- Yotsu RR, Suzuki K, Simmonds RE, et al. Buruli ulcer: a review of the current knowledge. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:247-256.

- Guarner J, Bartlett J, Whitney EA, et al. Histopathologic features of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:651-656.

A 61-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a painless nonhealing wound on the left calf of 4 years’ duration. The patient had a history of amputation of the right foot as an infant, for which he wore an orthopedic prosthesis. He also had chronic lymphedema of the left leg, hyperlipidemia, and osteoarthritis of the right hip. There was no history of gastrointestinal tract issues. The lesion initially was small, then grew and began to ulcerate and bleed. His presentation to dermatology was delayed due to office closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, erythematous, cribriform ulcer with a violaceous undermined rim. A punch biopsy was performed on the edge of the ulcer.

Surgical Planning for Mohs Defect Reconstruction in the Digital Age

Practice Gap

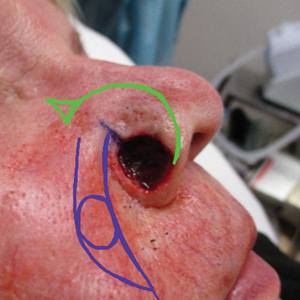

An essential part of training for a micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellowship and scope of practice involves planning and execution of reconstructive surgery for Mohs defects. Recently, a surgical pearl presented by Rickstrew and colleagues1 highlighted the use of different colored surgical marking pens and their benefit in a trainee-based environment.

Delineating multiple options for reconstruction with different colored markers on live patients allows fellows in-training to participate in surgical planning but introduces more markings or drawings that need to be wiped off during or after surgery, potentially prolonging operative time. Furthermore, the Rickstrew approach has the potential to (1) cause unnecessary emotional distress for the patient during surgical planning and (2) add to the cost of surgery with the purchase of various colors of surgical markers.

Technique

To improve patient experience and trainee education, we propose fine-tuning the colored marker approach by utilizing a digital drawing program for surgical planning prior to the procedure. We recommend Snip & Sketch—a free, readily accessible digital annotating application that runs on the Microsoft Windows 10 operating system (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/p/snip-sketch/9mz95kl8mr0l#activetab=pivot:overviewtab)—to mark up screenshot photographs of postoperative Mohs defects from the electronic medical record.

Using Snip & Sketch, the fellow in-training can then use, for example, a green “digital pen” to draw on the captured image and plan their surgical repairs (Figure 1) without input from the attending physician. Different colored pens can be used to highlight nerves, vessels, relaxed skin tension lines, and tension vectors associated with flap movement.

Subsequently, the attending physician, using a different color digital pen—say, blue—can design alternative reconstructive options (Figure 1). Suture lines also can be drawn to outline the predicted appearance of surgical scars (Figure 2).

Then, the attending physician and fellow in-training brainstorm and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each reconstructive option to determine the optimal approach to repairing the Mohs defect.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The main advantage of using a digital drawing program is that it is time-saving and cost-efficient. Digital planning also spares the patient undue anxiety from listening to the discussion on each repair option.

The primary downside of digital surgical planning is that it is 2-dimensional, thus providing an incomplete representation of a 3-dimensional cutaneous structure. In addition, skin laxity, flap mobility, and free-margin distortion cannot be fully appreciated on a 2-dimensional image.

Despite these drawbacks, digital surgical planning provides trainees with an active learning experience through a more collaborative and comprehensive discussion of reconstructive options.

Practice Implications

Active learning using an electronic device has been validated as a beneficial addition to Mohs micrographic surgery training.2 Utilizing a digitized annotating program for surgical planning increases the independence of trainees and allows immediate feedback from the attending physician. The synergy of digital technology and collaborative learning helps cultivate the next generation of confident and competent Mohs surgeons.

- Rickstrew J, Roberts E, Amarani A, et al. Different colored surgical marking pens for trainee education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021:S0190-9622(21)00226-7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.069

- Croley JA, Malone CH, Goodwin BP, et al. Mohs Surgical Reconstruction Educational Activity: a resident education tool. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:143-147. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S125454

Practice Gap

An essential part of training for a micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellowship and scope of practice involves planning and execution of reconstructive surgery for Mohs defects. Recently, a surgical pearl presented by Rickstrew and colleagues1 highlighted the use of different colored surgical marking pens and their benefit in a trainee-based environment.

Delineating multiple options for reconstruction with different colored markers on live patients allows fellows in-training to participate in surgical planning but introduces more markings or drawings that need to be wiped off during or after surgery, potentially prolonging operative time. Furthermore, the Rickstrew approach has the potential to (1) cause unnecessary emotional distress for the patient during surgical planning and (2) add to the cost of surgery with the purchase of various colors of surgical markers.

Technique

To improve patient experience and trainee education, we propose fine-tuning the colored marker approach by utilizing a digital drawing program for surgical planning prior to the procedure. We recommend Snip & Sketch—a free, readily accessible digital annotating application that runs on the Microsoft Windows 10 operating system (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/p/snip-sketch/9mz95kl8mr0l#activetab=pivot:overviewtab)—to mark up screenshot photographs of postoperative Mohs defects from the electronic medical record.

Using Snip & Sketch, the fellow in-training can then use, for example, a green “digital pen” to draw on the captured image and plan their surgical repairs (Figure 1) without input from the attending physician. Different colored pens can be used to highlight nerves, vessels, relaxed skin tension lines, and tension vectors associated with flap movement.

Subsequently, the attending physician, using a different color digital pen—say, blue—can design alternative reconstructive options (Figure 1). Suture lines also can be drawn to outline the predicted appearance of surgical scars (Figure 2).

Then, the attending physician and fellow in-training brainstorm and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each reconstructive option to determine the optimal approach to repairing the Mohs defect.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The main advantage of using a digital drawing program is that it is time-saving and cost-efficient. Digital planning also spares the patient undue anxiety from listening to the discussion on each repair option.

The primary downside of digital surgical planning is that it is 2-dimensional, thus providing an incomplete representation of a 3-dimensional cutaneous structure. In addition, skin laxity, flap mobility, and free-margin distortion cannot be fully appreciated on a 2-dimensional image.

Despite these drawbacks, digital surgical planning provides trainees with an active learning experience through a more collaborative and comprehensive discussion of reconstructive options.

Practice Implications

Active learning using an electronic device has been validated as a beneficial addition to Mohs micrographic surgery training.2 Utilizing a digitized annotating program for surgical planning increases the independence of trainees and allows immediate feedback from the attending physician. The synergy of digital technology and collaborative learning helps cultivate the next generation of confident and competent Mohs surgeons.

Practice Gap

An essential part of training for a micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology fellowship and scope of practice involves planning and execution of reconstructive surgery for Mohs defects. Recently, a surgical pearl presented by Rickstrew and colleagues1 highlighted the use of different colored surgical marking pens and their benefit in a trainee-based environment.

Delineating multiple options for reconstruction with different colored markers on live patients allows fellows in-training to participate in surgical planning but introduces more markings or drawings that need to be wiped off during or after surgery, potentially prolonging operative time. Furthermore, the Rickstrew approach has the potential to (1) cause unnecessary emotional distress for the patient during surgical planning and (2) add to the cost of surgery with the purchase of various colors of surgical markers.

Technique

To improve patient experience and trainee education, we propose fine-tuning the colored marker approach by utilizing a digital drawing program for surgical planning prior to the procedure. We recommend Snip & Sketch—a free, readily accessible digital annotating application that runs on the Microsoft Windows 10 operating system (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/p/snip-sketch/9mz95kl8mr0l#activetab=pivot:overviewtab)—to mark up screenshot photographs of postoperative Mohs defects from the electronic medical record.

Using Snip & Sketch, the fellow in-training can then use, for example, a green “digital pen” to draw on the captured image and plan their surgical repairs (Figure 1) without input from the attending physician. Different colored pens can be used to highlight nerves, vessels, relaxed skin tension lines, and tension vectors associated with flap movement.

Subsequently, the attending physician, using a different color digital pen—say, blue—can design alternative reconstructive options (Figure 1). Suture lines also can be drawn to outline the predicted appearance of surgical scars (Figure 2).

Then, the attending physician and fellow in-training brainstorm and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each reconstructive option to determine the optimal approach to repairing the Mohs defect.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The main advantage of using a digital drawing program is that it is time-saving and cost-efficient. Digital planning also spares the patient undue anxiety from listening to the discussion on each repair option.

The primary downside of digital surgical planning is that it is 2-dimensional, thus providing an incomplete representation of a 3-dimensional cutaneous structure. In addition, skin laxity, flap mobility, and free-margin distortion cannot be fully appreciated on a 2-dimensional image.

Despite these drawbacks, digital surgical planning provides trainees with an active learning experience through a more collaborative and comprehensive discussion of reconstructive options.

Practice Implications

Active learning using an electronic device has been validated as a beneficial addition to Mohs micrographic surgery training.2 Utilizing a digitized annotating program for surgical planning increases the independence of trainees and allows immediate feedback from the attending physician. The synergy of digital technology and collaborative learning helps cultivate the next generation of confident and competent Mohs surgeons.

- Rickstrew J, Roberts E, Amarani A, et al. Different colored surgical marking pens for trainee education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021:S0190-9622(21)00226-7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.069

- Croley JA, Malone CH, Goodwin BP, et al. Mohs Surgical Reconstruction Educational Activity: a resident education tool. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:143-147. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S125454

- Rickstrew J, Roberts E, Amarani A, et al. Different colored surgical marking pens for trainee education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021:S0190-9622(21)00226-7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.069

- Croley JA, Malone CH, Goodwin BP, et al. Mohs Surgical Reconstruction Educational Activity: a resident education tool. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:143-147. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S125454