User login

Residency Training During the #MeToo Movement

The #MeToo movement that took hold in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations in 2017 likely will be considered one of the major cultural touchpoints of the 2010s. Although activism within the entertainment industry initially drew attention to this movement, it is understood that virtually no workplace is immune to sexual misconduct. Many medical professionals acknowledge #MeToo as a catchy hashtag summarizing a problem that has long been recognized in the field of medicine but often has been inadequately addressed.1 As dermatology residency program directors (PDs) at the University of Southern California (USC) Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, California), we have seen the considerable impact that recent high-profile allegations of sexual assault have had at our institution, leading us to take part in institutional and departmental initiatives and reflections that we believe have strengthened the culture within our residency program and positioned us to be proactive in addressing this critical issue.

Before we discuss the efforts to combat sexual misconduct and gender inequality at USC and within our dermatology department, it is worth reflecting on where we stand as a specialty with regard to gender representation. A recent JAMA Dermatology article reported that in 1970 only 10.8% of dermatology academic faculty were women but by 2018 that number had skyrocketed to 51.2%; however, in contrast to this overall increase, only 19.4% of dermatology department chairs in 2018 were women.2 Although we have made large strides as a field, this discrepancy indicates that we still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality.

Although dermatology as a specialty is working toward gender equality, we believe it is crucial to consider this issue in the context of the entire field of medicine, particularly because academic physicians and trainees often interface with a myriad of specialties. It is well known that women in medicine are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and that subsequent issues with imposter syndrome and/or depression are more prevalent in female physicians.3,4 Gender inequality and sexism, among other factors, can make it difficult for women to obtain and maintain leadership positions and can negatively impact the culture of an academic institution in numerous downstream ways.

We also know that academic environments in medicine have a higher prevalence of gender equality issues than in private practice or in settings where medicine is practiced without trainees due to the hierarchical nature of training and the necessary differences in experience between trainees and faculty.3 Furthermore, because trainees form and solidify their professional identities during graduate medical education (GME) training, it is a prime time to emphasize the importance of gender equality and establish zero tolerance policies for workplace abuse and transgressions.5

The data and our personal experiences delineate a clear need for continued vigilance regarding gender equality issues both in dermatology as a specialty and in medicine in general. As PDs, we feel fortunate to have worked in conjunction with our GME committee and our dermatology department to solidify and create policies that work to promote a culture of gender equality. Herein, we will outline some of these efforts with the hope that other academic institutions may consider implementing these programs to protect members of their community from harassment, sexual violence, and gender discrimination.

Create a SAFE Committee

At the institutional level, our GME committee has created the SAFE (Safety, Fairness & Equity) committee under the leadership of Lawrence Opas, MD. The SAFE committee is headed by a female faculty physician and includes members of the medical community who have the influence to affect change and a commitment to protect vulnerable populations. Members include the Chief Medical Officer, the Designated Institutional Officer, the Director of Resident Wellness, and the Dean of the Keck School of Medicine at USC. The SAFE committee serves as a 24/7 reporting resource whereby trainees can report any issues relating to harassment in the workplace via a telephone hotline or online platform. Issues brought to this committee are immediately dealt with and reviewed at monthly GME meetings to keep institutional PDs up-to-date on issues pertaining to sexual harassment and assault within our workplace. The SAFE committee also has departmental resident liaisons who bring information to residents and help guide them to appropriate resources.

Emphasize Resident Wellness

Along with the development of robust reporting resources, our institution has continued to build upon a culture that places a strong emphasis on resident wellness. One of the most meaningful efforts over the last 5 years has included recruitment of a clinical psychologist, Tobi Fishel, PhD, to serve as our institution’s Director of Wellness. She is available to meet confidentially with our residents and helps to serve as a link between trainees and the GME committee.

Our dermatology department takes a tremendous amount of pride in its culture. We are fortunate to have David Peng, MD, MPH, Chair, and Stefani Takahashi, MD, Vice Chair of Education, working daily to create an environment that values teamwork, selflessness, and wellness. We have been continuously grateful for their leadership and guidance in addressing the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that arose at USC over the past several years. Our department has a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment or harassment of any kind, and we have taken important steps to ensure and promote a safe environment for our trainees, many of which are focused on communication. We try to avoid assumptions and encourage both residents and faculty to explicitly state their experiences and opinions in general but also in relation to instances of potential misconduct.

Encourage Communication

When allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace were made at our institution, we prioritized immediate in-person communication with our residents to reinforce our zero tolerance policy and to remind them that we are available should any similar issues arise in our department. It was of equal value to remind our trainees of potential resources, such as the SAFE committee, to whom they could bring their concerns if they were not comfortable communicating directly with us. Although we hoped that our trainees understood that we would not be tolerant of any form of harassment based on our past actions and communications, we felt that it was helpful to explicitly delineate this by laying out other avenues of support on a regular basis with them. By ensuring there is a space for a dialogue with others, if needed, our institution and department have provided an extra layer of security for our trainees. Multiple channels of support are crucial to ensure trainee safety.

Dr. Peng also created a workplace safety committee that includes several female faculty members. The committee regularly shares and highlights institutional and departmental resources as they pertain to gender equality and safety within the workplace and also has considerable faculty overlap with our departmental diversity committee. Together, these committees work toward the common goal of fostering an environment in which all members of our department feel comfortable voicing concerns, and we are best able to recruit and retain a diverse faculty.

As PDs, we work to reinforce departmental and institutional messages in our daily communication with residents. We have found that ensuring frequent and varied interactions—quarterly meetings, biannual evaluations, faculty-led didactics 2 half-days per week, and weekly clinical interactions—with our trainees can help to create a culture where they feel comfortable bringing up issues, be they routine clinical operations questions or issues relating to their professional identity. We hope it also has created the space for them to approach us with any issues pertaining to harassment should they ever arise, and we are grateful to know that even if this comfort does not exist, our institution and department have other resources for them.

Final Thoughts

Although some of the measures discussed here were reactionary, many predated the recent institutional concerns and allegations at USC. We hope and believe that the culture we foster within our department has helped our trainees feel safe and cared for during a time of institutional turbulence. We also believe that taking similar proactive measures may benefit the overall culture and foster the development of diverse physicians and leadership at other institutions. In conjunction with reworking legislation and implementing institutional safeguards, the long-term goals of taking these proactive measures are to promote gender equality and workplace safety and to cultivate and retain effective female leadership in medical institutions and training programs.

We feel incredibly fortunate to be part of a specialty in which gender equality has long been considered and sought after. We also are proud to be members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which has addressed issues such as diversity and gender equality in a transparent and head-on manner and continues to do so. As a specialty, we hope we can support our trainees in their professional growth and help to cultivate sensitive physicians who will care for an increasingly diverse population and better support each other in their own career development.

- Ladika S. Sexual harassment: health care, it is #youtoo. Manag Care. 2018;27:14-17.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970 to 2018 [published online January 8, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297.

- Minkina N. Can #MeToo abolish sexual harassment and discrimination in medicine? Lancet. 2019;394:383-384.

- Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589-1591.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26:230-238.

The #MeToo movement that took hold in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations in 2017 likely will be considered one of the major cultural touchpoints of the 2010s. Although activism within the entertainment industry initially drew attention to this movement, it is understood that virtually no workplace is immune to sexual misconduct. Many medical professionals acknowledge #MeToo as a catchy hashtag summarizing a problem that has long been recognized in the field of medicine but often has been inadequately addressed.1 As dermatology residency program directors (PDs) at the University of Southern California (USC) Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, California), we have seen the considerable impact that recent high-profile allegations of sexual assault have had at our institution, leading us to take part in institutional and departmental initiatives and reflections that we believe have strengthened the culture within our residency program and positioned us to be proactive in addressing this critical issue.

Before we discuss the efforts to combat sexual misconduct and gender inequality at USC and within our dermatology department, it is worth reflecting on where we stand as a specialty with regard to gender representation. A recent JAMA Dermatology article reported that in 1970 only 10.8% of dermatology academic faculty were women but by 2018 that number had skyrocketed to 51.2%; however, in contrast to this overall increase, only 19.4% of dermatology department chairs in 2018 were women.2 Although we have made large strides as a field, this discrepancy indicates that we still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality.

Although dermatology as a specialty is working toward gender equality, we believe it is crucial to consider this issue in the context of the entire field of medicine, particularly because academic physicians and trainees often interface with a myriad of specialties. It is well known that women in medicine are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and that subsequent issues with imposter syndrome and/or depression are more prevalent in female physicians.3,4 Gender inequality and sexism, among other factors, can make it difficult for women to obtain and maintain leadership positions and can negatively impact the culture of an academic institution in numerous downstream ways.

We also know that academic environments in medicine have a higher prevalence of gender equality issues than in private practice or in settings where medicine is practiced without trainees due to the hierarchical nature of training and the necessary differences in experience between trainees and faculty.3 Furthermore, because trainees form and solidify their professional identities during graduate medical education (GME) training, it is a prime time to emphasize the importance of gender equality and establish zero tolerance policies for workplace abuse and transgressions.5

The data and our personal experiences delineate a clear need for continued vigilance regarding gender equality issues both in dermatology as a specialty and in medicine in general. As PDs, we feel fortunate to have worked in conjunction with our GME committee and our dermatology department to solidify and create policies that work to promote a culture of gender equality. Herein, we will outline some of these efforts with the hope that other academic institutions may consider implementing these programs to protect members of their community from harassment, sexual violence, and gender discrimination.

Create a SAFE Committee

At the institutional level, our GME committee has created the SAFE (Safety, Fairness & Equity) committee under the leadership of Lawrence Opas, MD. The SAFE committee is headed by a female faculty physician and includes members of the medical community who have the influence to affect change and a commitment to protect vulnerable populations. Members include the Chief Medical Officer, the Designated Institutional Officer, the Director of Resident Wellness, and the Dean of the Keck School of Medicine at USC. The SAFE committee serves as a 24/7 reporting resource whereby trainees can report any issues relating to harassment in the workplace via a telephone hotline or online platform. Issues brought to this committee are immediately dealt with and reviewed at monthly GME meetings to keep institutional PDs up-to-date on issues pertaining to sexual harassment and assault within our workplace. The SAFE committee also has departmental resident liaisons who bring information to residents and help guide them to appropriate resources.

Emphasize Resident Wellness

Along with the development of robust reporting resources, our institution has continued to build upon a culture that places a strong emphasis on resident wellness. One of the most meaningful efforts over the last 5 years has included recruitment of a clinical psychologist, Tobi Fishel, PhD, to serve as our institution’s Director of Wellness. She is available to meet confidentially with our residents and helps to serve as a link between trainees and the GME committee.

Our dermatology department takes a tremendous amount of pride in its culture. We are fortunate to have David Peng, MD, MPH, Chair, and Stefani Takahashi, MD, Vice Chair of Education, working daily to create an environment that values teamwork, selflessness, and wellness. We have been continuously grateful for their leadership and guidance in addressing the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that arose at USC over the past several years. Our department has a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment or harassment of any kind, and we have taken important steps to ensure and promote a safe environment for our trainees, many of which are focused on communication. We try to avoid assumptions and encourage both residents and faculty to explicitly state their experiences and opinions in general but also in relation to instances of potential misconduct.

Encourage Communication

When allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace were made at our institution, we prioritized immediate in-person communication with our residents to reinforce our zero tolerance policy and to remind them that we are available should any similar issues arise in our department. It was of equal value to remind our trainees of potential resources, such as the SAFE committee, to whom they could bring their concerns if they were not comfortable communicating directly with us. Although we hoped that our trainees understood that we would not be tolerant of any form of harassment based on our past actions and communications, we felt that it was helpful to explicitly delineate this by laying out other avenues of support on a regular basis with them. By ensuring there is a space for a dialogue with others, if needed, our institution and department have provided an extra layer of security for our trainees. Multiple channels of support are crucial to ensure trainee safety.

Dr. Peng also created a workplace safety committee that includes several female faculty members. The committee regularly shares and highlights institutional and departmental resources as they pertain to gender equality and safety within the workplace and also has considerable faculty overlap with our departmental diversity committee. Together, these committees work toward the common goal of fostering an environment in which all members of our department feel comfortable voicing concerns, and we are best able to recruit and retain a diverse faculty.

As PDs, we work to reinforce departmental and institutional messages in our daily communication with residents. We have found that ensuring frequent and varied interactions—quarterly meetings, biannual evaluations, faculty-led didactics 2 half-days per week, and weekly clinical interactions—with our trainees can help to create a culture where they feel comfortable bringing up issues, be they routine clinical operations questions or issues relating to their professional identity. We hope it also has created the space for them to approach us with any issues pertaining to harassment should they ever arise, and we are grateful to know that even if this comfort does not exist, our institution and department have other resources for them.

Final Thoughts

Although some of the measures discussed here were reactionary, many predated the recent institutional concerns and allegations at USC. We hope and believe that the culture we foster within our department has helped our trainees feel safe and cared for during a time of institutional turbulence. We also believe that taking similar proactive measures may benefit the overall culture and foster the development of diverse physicians and leadership at other institutions. In conjunction with reworking legislation and implementing institutional safeguards, the long-term goals of taking these proactive measures are to promote gender equality and workplace safety and to cultivate and retain effective female leadership in medical institutions and training programs.

We feel incredibly fortunate to be part of a specialty in which gender equality has long been considered and sought after. We also are proud to be members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which has addressed issues such as diversity and gender equality in a transparent and head-on manner and continues to do so. As a specialty, we hope we can support our trainees in their professional growth and help to cultivate sensitive physicians who will care for an increasingly diverse population and better support each other in their own career development.

The #MeToo movement that took hold in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations in 2017 likely will be considered one of the major cultural touchpoints of the 2010s. Although activism within the entertainment industry initially drew attention to this movement, it is understood that virtually no workplace is immune to sexual misconduct. Many medical professionals acknowledge #MeToo as a catchy hashtag summarizing a problem that has long been recognized in the field of medicine but often has been inadequately addressed.1 As dermatology residency program directors (PDs) at the University of Southern California (USC) Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, California), we have seen the considerable impact that recent high-profile allegations of sexual assault have had at our institution, leading us to take part in institutional and departmental initiatives and reflections that we believe have strengthened the culture within our residency program and positioned us to be proactive in addressing this critical issue.

Before we discuss the efforts to combat sexual misconduct and gender inequality at USC and within our dermatology department, it is worth reflecting on where we stand as a specialty with regard to gender representation. A recent JAMA Dermatology article reported that in 1970 only 10.8% of dermatology academic faculty were women but by 2018 that number had skyrocketed to 51.2%; however, in contrast to this overall increase, only 19.4% of dermatology department chairs in 2018 were women.2 Although we have made large strides as a field, this discrepancy indicates that we still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality.

Although dermatology as a specialty is working toward gender equality, we believe it is crucial to consider this issue in the context of the entire field of medicine, particularly because academic physicians and trainees often interface with a myriad of specialties. It is well known that women in medicine are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and that subsequent issues with imposter syndrome and/or depression are more prevalent in female physicians.3,4 Gender inequality and sexism, among other factors, can make it difficult for women to obtain and maintain leadership positions and can negatively impact the culture of an academic institution in numerous downstream ways.

We also know that academic environments in medicine have a higher prevalence of gender equality issues than in private practice or in settings where medicine is practiced without trainees due to the hierarchical nature of training and the necessary differences in experience between trainees and faculty.3 Furthermore, because trainees form and solidify their professional identities during graduate medical education (GME) training, it is a prime time to emphasize the importance of gender equality and establish zero tolerance policies for workplace abuse and transgressions.5

The data and our personal experiences delineate a clear need for continued vigilance regarding gender equality issues both in dermatology as a specialty and in medicine in general. As PDs, we feel fortunate to have worked in conjunction with our GME committee and our dermatology department to solidify and create policies that work to promote a culture of gender equality. Herein, we will outline some of these efforts with the hope that other academic institutions may consider implementing these programs to protect members of their community from harassment, sexual violence, and gender discrimination.

Create a SAFE Committee

At the institutional level, our GME committee has created the SAFE (Safety, Fairness & Equity) committee under the leadership of Lawrence Opas, MD. The SAFE committee is headed by a female faculty physician and includes members of the medical community who have the influence to affect change and a commitment to protect vulnerable populations. Members include the Chief Medical Officer, the Designated Institutional Officer, the Director of Resident Wellness, and the Dean of the Keck School of Medicine at USC. The SAFE committee serves as a 24/7 reporting resource whereby trainees can report any issues relating to harassment in the workplace via a telephone hotline or online platform. Issues brought to this committee are immediately dealt with and reviewed at monthly GME meetings to keep institutional PDs up-to-date on issues pertaining to sexual harassment and assault within our workplace. The SAFE committee also has departmental resident liaisons who bring information to residents and help guide them to appropriate resources.

Emphasize Resident Wellness

Along with the development of robust reporting resources, our institution has continued to build upon a culture that places a strong emphasis on resident wellness. One of the most meaningful efforts over the last 5 years has included recruitment of a clinical psychologist, Tobi Fishel, PhD, to serve as our institution’s Director of Wellness. She is available to meet confidentially with our residents and helps to serve as a link between trainees and the GME committee.

Our dermatology department takes a tremendous amount of pride in its culture. We are fortunate to have David Peng, MD, MPH, Chair, and Stefani Takahashi, MD, Vice Chair of Education, working daily to create an environment that values teamwork, selflessness, and wellness. We have been continuously grateful for their leadership and guidance in addressing the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that arose at USC over the past several years. Our department has a zero tolerance policy for sexual harassment or harassment of any kind, and we have taken important steps to ensure and promote a safe environment for our trainees, many of which are focused on communication. We try to avoid assumptions and encourage both residents and faculty to explicitly state their experiences and opinions in general but also in relation to instances of potential misconduct.

Encourage Communication

When allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace were made at our institution, we prioritized immediate in-person communication with our residents to reinforce our zero tolerance policy and to remind them that we are available should any similar issues arise in our department. It was of equal value to remind our trainees of potential resources, such as the SAFE committee, to whom they could bring their concerns if they were not comfortable communicating directly with us. Although we hoped that our trainees understood that we would not be tolerant of any form of harassment based on our past actions and communications, we felt that it was helpful to explicitly delineate this by laying out other avenues of support on a regular basis with them. By ensuring there is a space for a dialogue with others, if needed, our institution and department have provided an extra layer of security for our trainees. Multiple channels of support are crucial to ensure trainee safety.

Dr. Peng also created a workplace safety committee that includes several female faculty members. The committee regularly shares and highlights institutional and departmental resources as they pertain to gender equality and safety within the workplace and also has considerable faculty overlap with our departmental diversity committee. Together, these committees work toward the common goal of fostering an environment in which all members of our department feel comfortable voicing concerns, and we are best able to recruit and retain a diverse faculty.

As PDs, we work to reinforce departmental and institutional messages in our daily communication with residents. We have found that ensuring frequent and varied interactions—quarterly meetings, biannual evaluations, faculty-led didactics 2 half-days per week, and weekly clinical interactions—with our trainees can help to create a culture where they feel comfortable bringing up issues, be they routine clinical operations questions or issues relating to their professional identity. We hope it also has created the space for them to approach us with any issues pertaining to harassment should they ever arise, and we are grateful to know that even if this comfort does not exist, our institution and department have other resources for them.

Final Thoughts

Although some of the measures discussed here were reactionary, many predated the recent institutional concerns and allegations at USC. We hope and believe that the culture we foster within our department has helped our trainees feel safe and cared for during a time of institutional turbulence. We also believe that taking similar proactive measures may benefit the overall culture and foster the development of diverse physicians and leadership at other institutions. In conjunction with reworking legislation and implementing institutional safeguards, the long-term goals of taking these proactive measures are to promote gender equality and workplace safety and to cultivate and retain effective female leadership in medical institutions and training programs.

We feel incredibly fortunate to be part of a specialty in which gender equality has long been considered and sought after. We also are proud to be members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which has addressed issues such as diversity and gender equality in a transparent and head-on manner and continues to do so. As a specialty, we hope we can support our trainees in their professional growth and help to cultivate sensitive physicians who will care for an increasingly diverse population and better support each other in their own career development.

- Ladika S. Sexual harassment: health care, it is #youtoo. Manag Care. 2018;27:14-17.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970 to 2018 [published online January 8, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297.

- Minkina N. Can #MeToo abolish sexual harassment and discrimination in medicine? Lancet. 2019;394:383-384.

- Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589-1591.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26:230-238.

- Ladika S. Sexual harassment: health care, it is #youtoo. Manag Care. 2018;27:14-17.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Pandya AG. US dermatology department faculty diversity trends by sex and underrepresented-in-medicine status, 1970 to 2018 [published online January 8, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4297.

- Minkina N. Can #MeToo abolish sexual harassment and discrimination in medicine? Lancet. 2019;394:383-384.

- Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589-1591.

- Nothnagle M, Reis S, Goldman RE, et al. Fostering professional formation in residency: development and evaluation of the “forum” seminar series. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26:230-238.

Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Care: A Prospective Study at Outpatient Dermatology Clinics

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

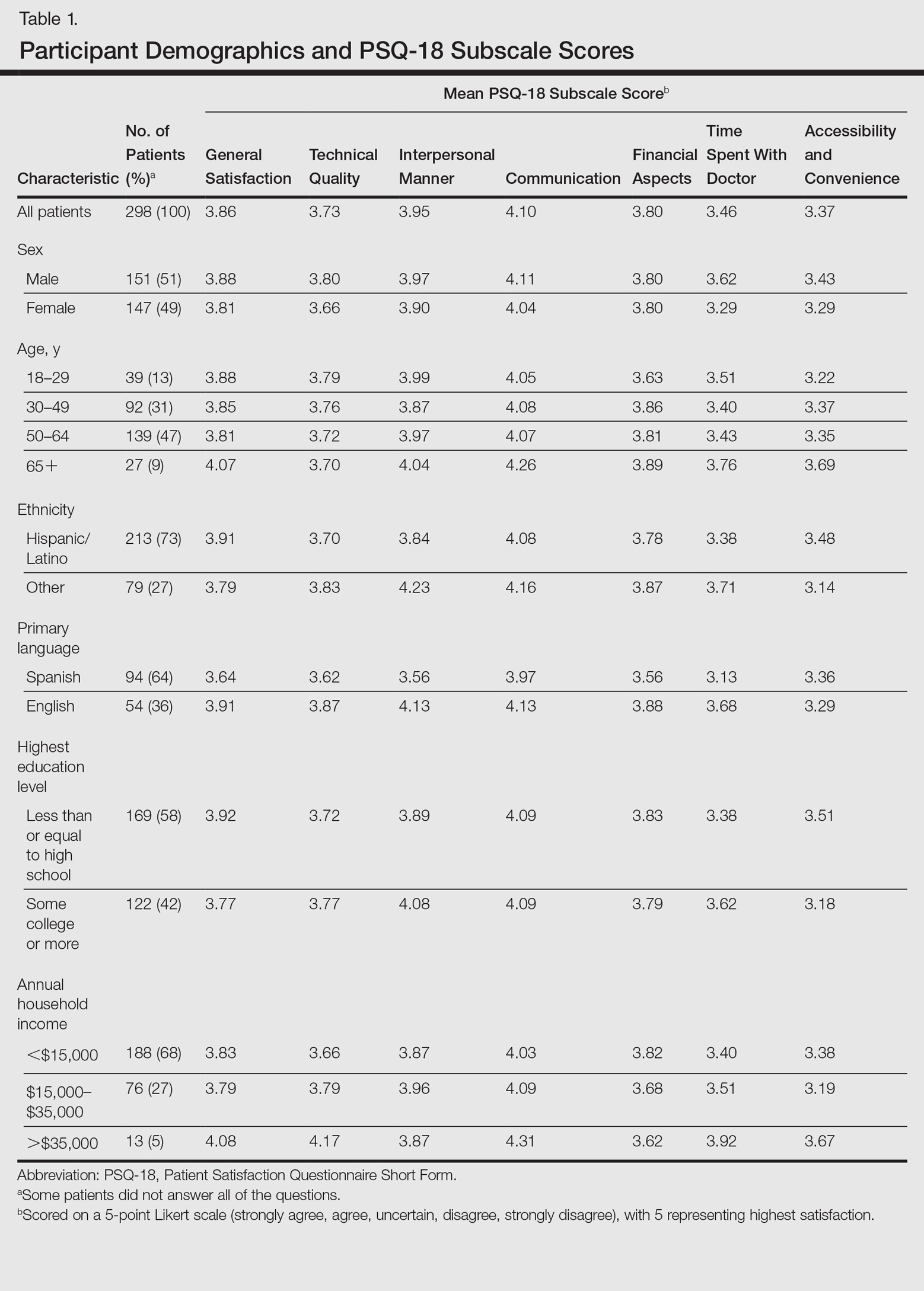

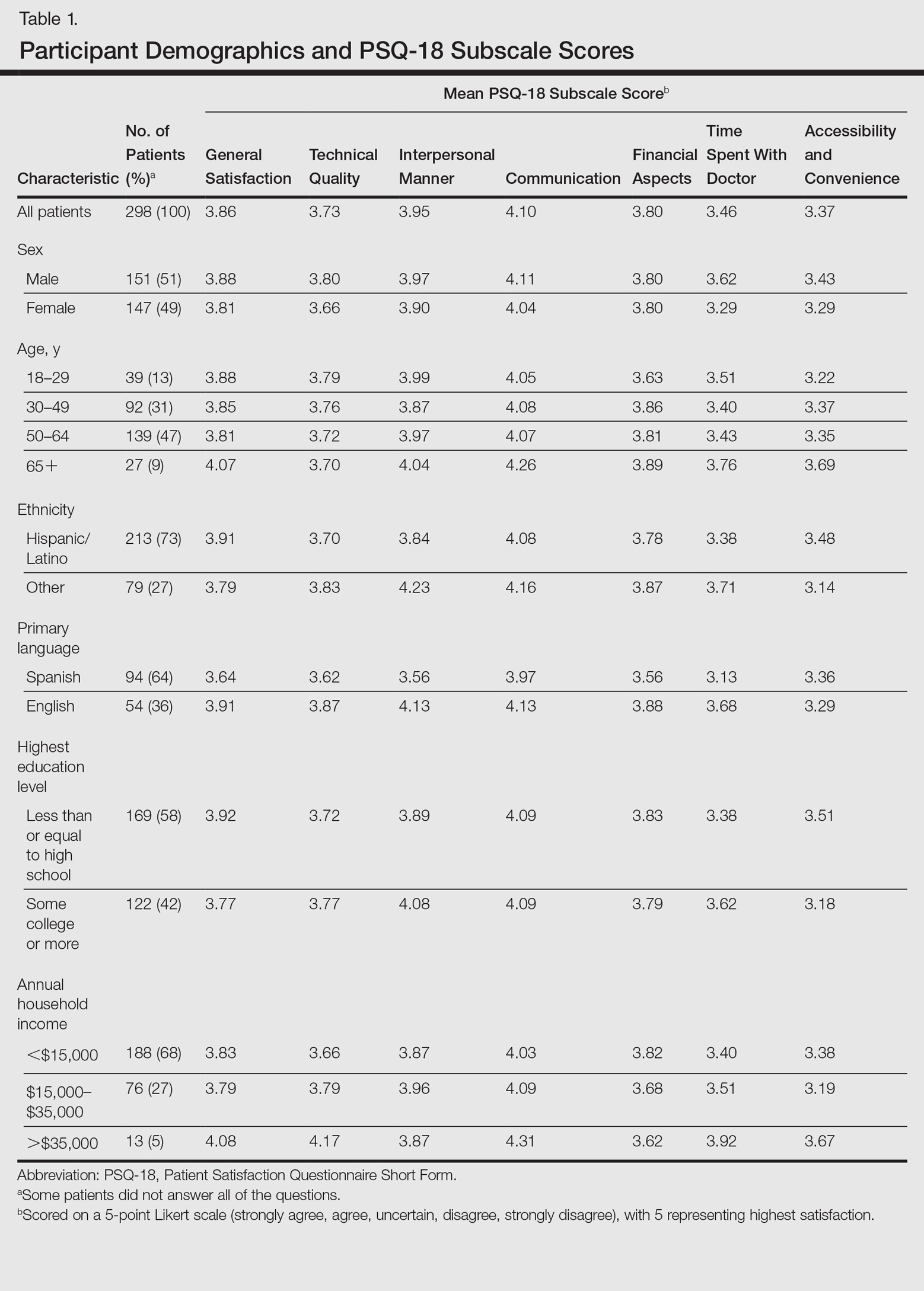

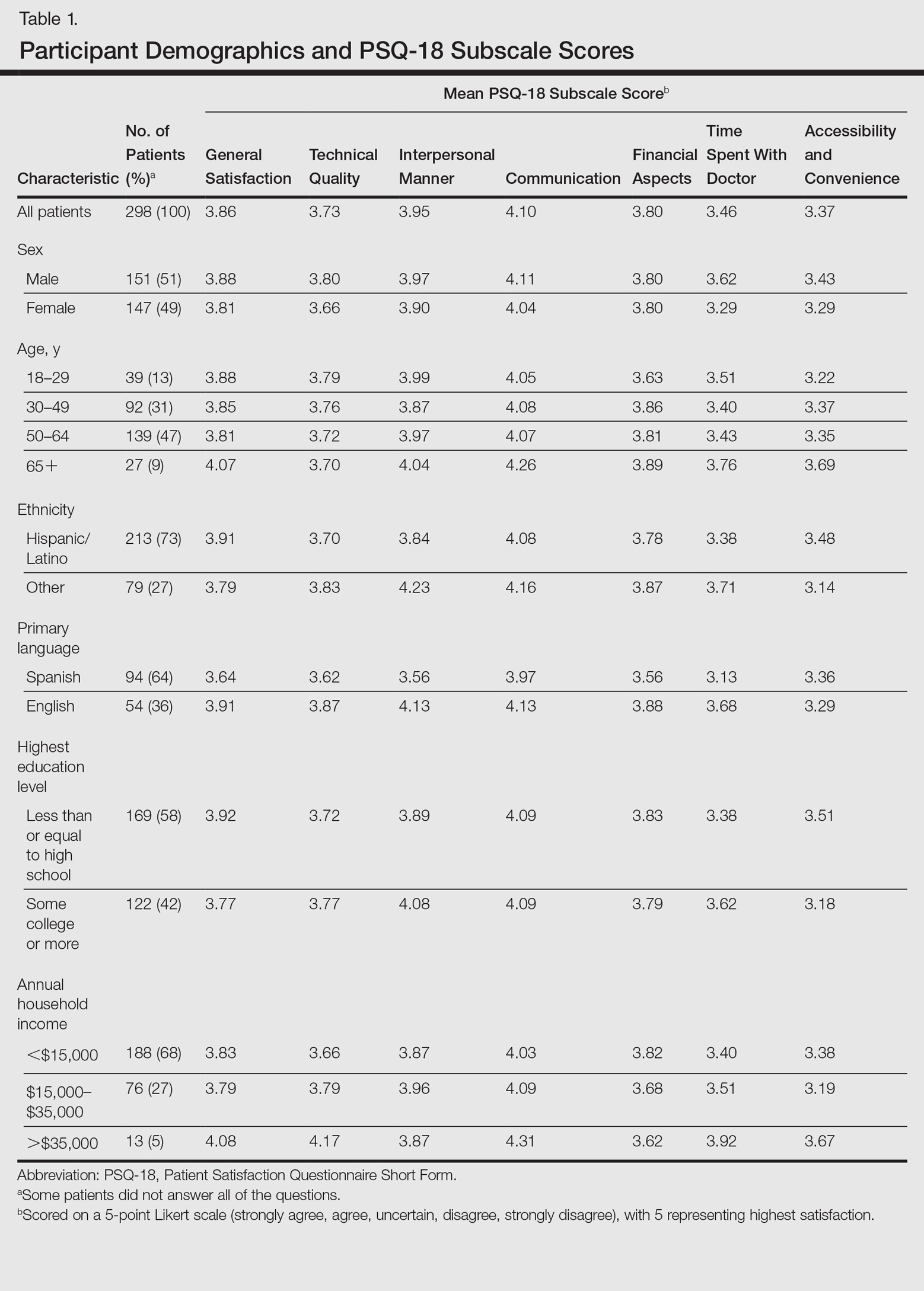

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

Practice Points

- It is becoming increasingly important, particularly in the field of dermatology, to both measure and work to improve patient satisfaction scores.

- Preliminary research has found that simple interventions, such as providing disease-specific handouts and interpreter services, can improve satisfaction scores, making patient satisfaction an achievable goal.

Improving Patient Satisfaction in Dermatology: A Prospective Study of an Urban Dermatology Clinic

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was signed into law in 2010, aiming to expand access to and improve the quality of health care in the United States. In the states that expanded Medicaid eligibility, uninsurance among adults decreased from 15.8% in September 2013 to 7.3% in March 2016, a decline of 53.8%.1 On average, these newly insured individuals were younger and more likely to report fair to poor health than those previously insured. Approximately half of the newly insured have family incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level.1

Improvement in quality in medicine is not as easily quantified. Several programs have been implemented through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to measure and reimburse hospital systems and providers based on the quality and value of care being provided. Because of the complexity in defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction has become a proxy measurement tool.2 With higher numbers of insured patients and an increased demand for services, dermatologists are being challenged to improve availability of services and respond to patients’ needs and desires as expressed through satisfaction surveys.

Few studies have assessed patient satisfaction in dermatology practices. As patient satisfaction surveys move to the forefront under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, hospitals and providers will try to demonstrate the quality of their care through positive survey responses from patients. Importantly, patient satisfaction is a strong determinate if patients will comply with treatment and continue seeing their practitioner.3 A better understanding of patients’ perceptions regarding quality will allow for targeted interventions to be implemented. This study assesses and analyzes patient satisfaction, nonattendance rates, and cycle times in an outpatient dermatology clinic to provide a snapshot of patient satisfaction in an urban dermatology clinic.

Dr. Adam Sutton discusses the results of this study with Editor-in-Chief Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, in a "Peer to Peer" audiocast, "Measuring Patient Satisfaction: How Do Patients Perceive Quality of Care Delivered by Dermatologists?"

Methods

We conducted a prospective study that was approved by the University of Southern California Health Sciences (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board. A convenience sample of patients 18 years and older who spoke English or Spanish were recruited to participate in the study and agreed to complete the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) and a demographic questionnaire, both in English or Spanish, at the conclusion of their visit.

Based on schedules and availability, medical students came to our clinic and obtained the surveys in the following manner: After patients checked in, the students approached the patients in the waiting area and asked if they would be willing to participate in the study. If patients agreed to participate, they provided written consent and the medical student handed them an envelope containing paper copies of the survey in English or Spanish, depending on the patient’s preference. Patients were asked to complete the surveys at the end of the visit and return them to the student in the envelope. The medical students did not otherwise participate in the patient’s visit.

Surveys were collected over an 8-month period at Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center dermatology clinics, which are part of a large safety-net health system. Among this population, it is common for patients to lack reliable Internet access or permanent home addresses; therefore, we elected to use point-of-care printed survey forms. Midway through the survey collection, we moved our clinic location; however, patients and physicians did not change. The comparison between clinics showed no substantive differences and did not change the conclusions of the study.

Patient Demographics

Demographic variables were age, sex, ethnicity, highest education level, annual household income, and primary language. Patients were grouped into 4 age categories: 18 to 29 years, 30 to 49 years, 50 to 64 years, and 65 years and older. Ethnicity was classified as Hispanic/Latino or other. Highest education level was classified as high school diploma or lower, and some college or higher. Annual household income was grouped into 3 categories: less than $15,000, $15,000 to $35,000, and more than $35,000.

Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire

The PSQ-18 survey was developed by the RAND Corporation (Santa Monica, California) and has been validated.4 The survey asks patients to rate aspects of their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, uncertain, disagree, strongly disagree), with 5 representing highest satisfaction. The survey contains 18 questions and is scored on 7 subscales: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with doctor, and accessibility and convenience. The survey typically takes less than 5 minutes to complete.

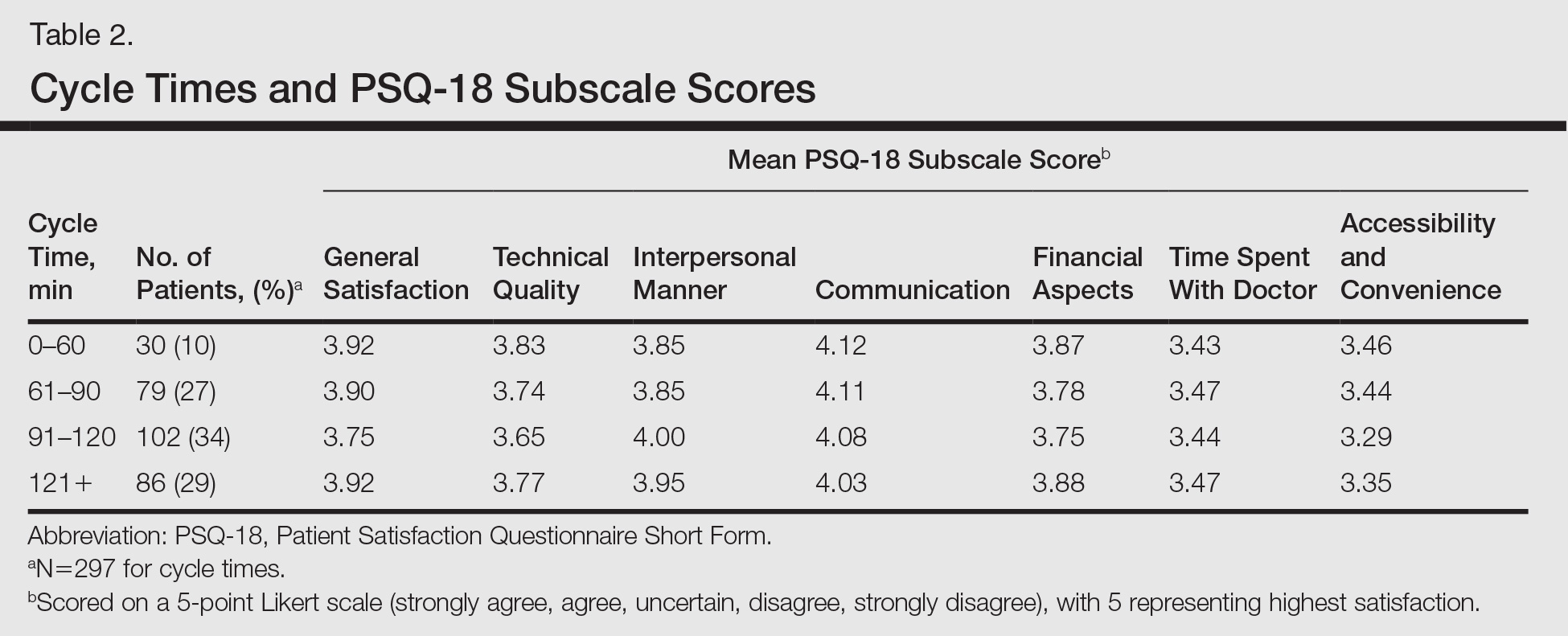

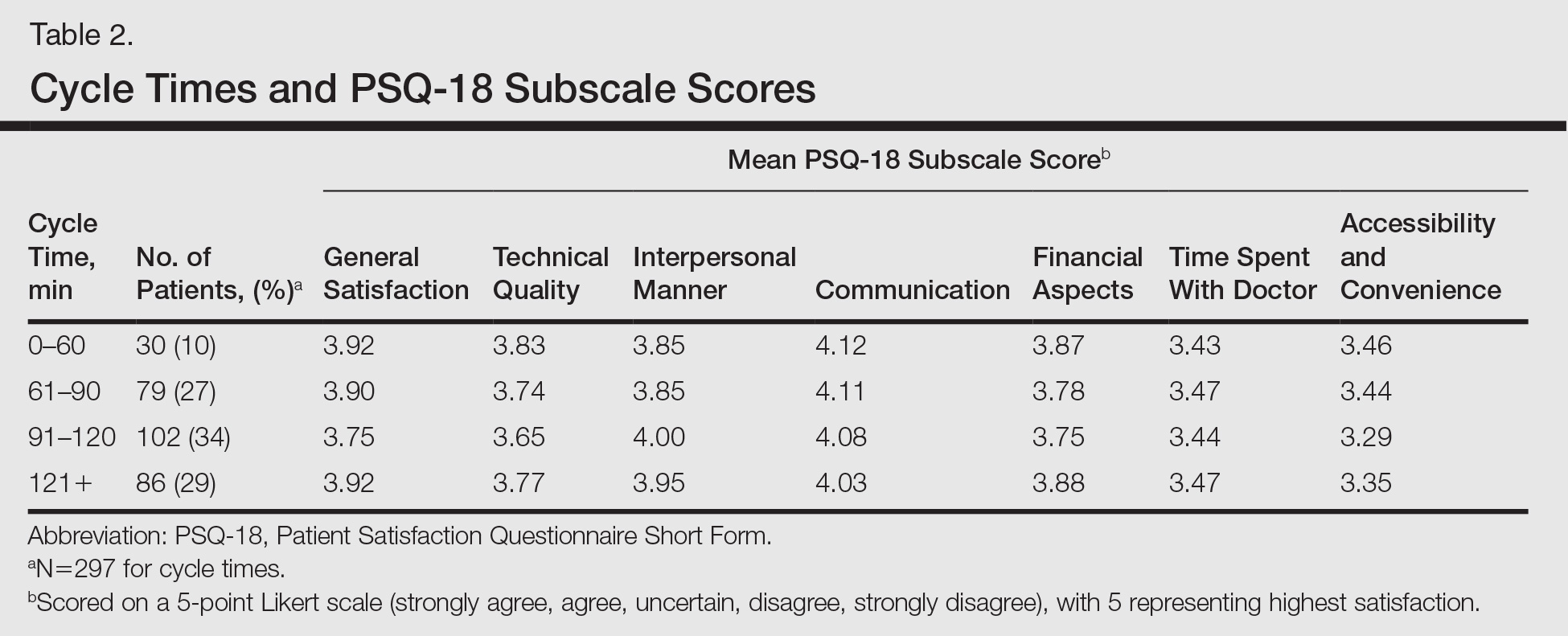

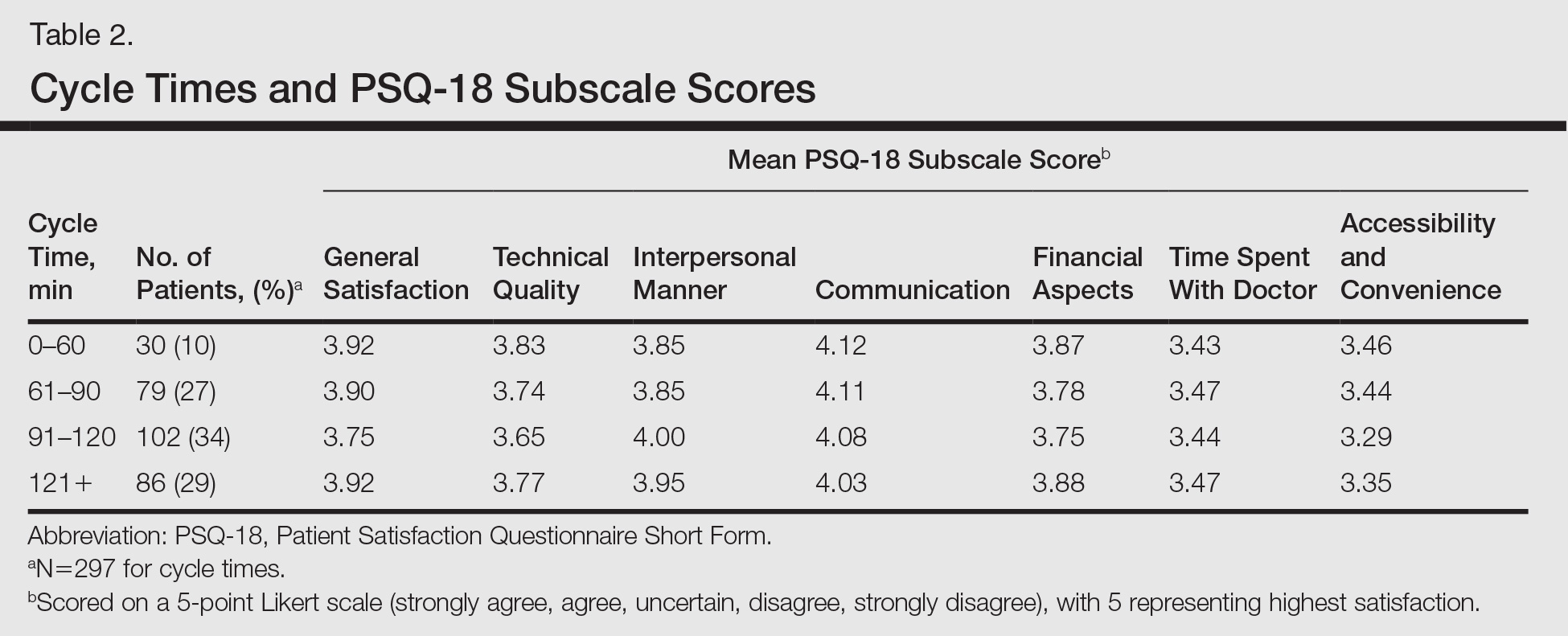

Cycle Times and Nonattendance Rates

Cycle time is defined as the total amount of time that a patient spends in a clinic from check in to checkout, which was collected from our scheduling system for each patient who agreed to participate in the study. Cycle times were grouped into 4 categories: 0 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, 91 to 120 minutes, and 121 minutes or more. During the study period, data also were collected from the electronic health record system regarding the number of patients with appointments scheduled and the number of patients who attended each clinic. From these figures, the rate of nonattendance for each clinic was calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic results were calculated using arithmetic means. The PSQ-18 subscale scores were compared among demographic subgroups using a generalized linear model. Covariates included age, sex, ethnicity, highest education level, annual household income, and primary language. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.2.

Results

Of the 298 participants surveyed, the average age was 49 years, 51% were male, 73% self-identified as Hispanic/Latino, 64% spoke Spanish, 58% had a high school diploma or lower, and 68% reported an annual household income of less than $15,000 (Table 1).