User login

Unusually Early-Onset Plantar Verrucous Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is a rare type of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by a well-differentiated low-grade tumor with a high degree of keratinization. First described by Ackerman1 in 1948, VC presents on the skin or oral and genital mucosae with minimal atypical cytologic findings.1-3 It most commonly is seen in late middle-aged men (85% of cases) and presents as a slow-growing mass, often of more than 10 years’ duration.2,3 Verrucous carcinoma frequently is observed at 3 particular anatomic sites: the oral cavity, known as oral florid papillomatosis; the anogenital area, known as Buschke-Löwenstein tumor; and on the plantar surface, known as epithelioma cuniculatum.2-13

A 19-year-old man presented with an ulcerous lesion on the right big toe of 2 years’ duration. He reported that the lesion had gradually increased in size and was painful when walking. Physical examination revealed an ulcerated lesion on the right big toe with purulent inflammation and necrosis, unclear edges, and border nodules containing a fatty, yellowish, foul-smelling material (Figure 1). Histologic examination of purulent material from deep within the primary lesion revealed gram-negative rods and gram-positive diplococci. Erlich-Ziehl-Neelsen staining and culture in Lowenstein-Jensen medium were negative for mycobacteria. Histologic examination and fungal culture were not diagnostic for fungal infection.

The differential diagnosis included tuberculosis cutis verrucosa, subcutaneous mycoses, swimming pool granuloma, leishmania cutis, chronic pyoderma vegetans, and VC. A punch biopsy of the lesion showed chronic nonspecific inflammation, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A repeat biopsy performed 15 days later also showed a nonspecific inflammation. At the initial presentation, an anti–human immunodeficiency virus test was negative. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was positive and showed a 17-mm induration, and a sputum test was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A chest radiograph was normal. We considered the positive PPD skin test to be clinically insignificant; we did not find an accompanying tuberculosis infection, and the high exposure to atypical tuberculosis in developing countries such as Turkey, which is where the patient resided, often explains a positive PPD test.

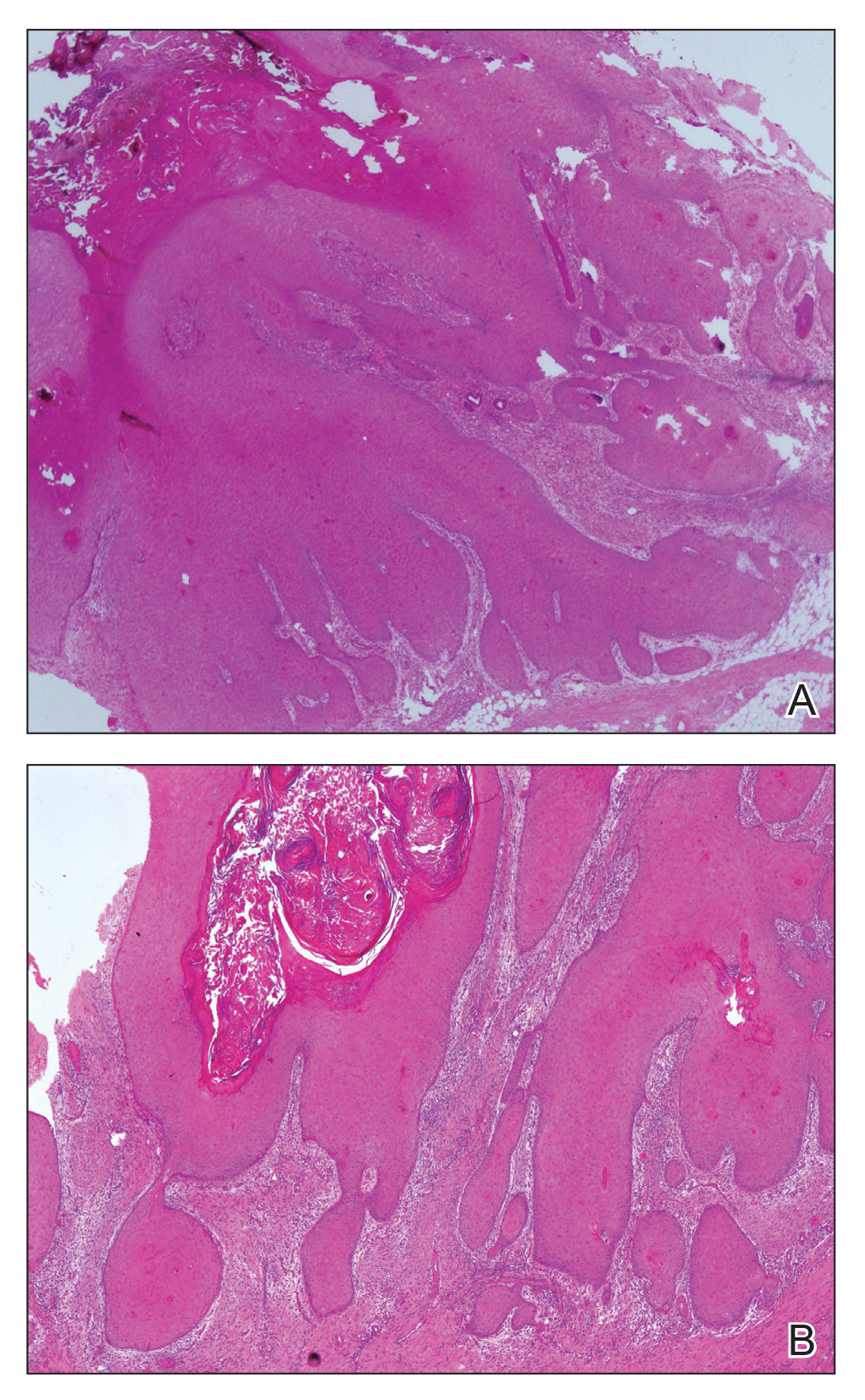

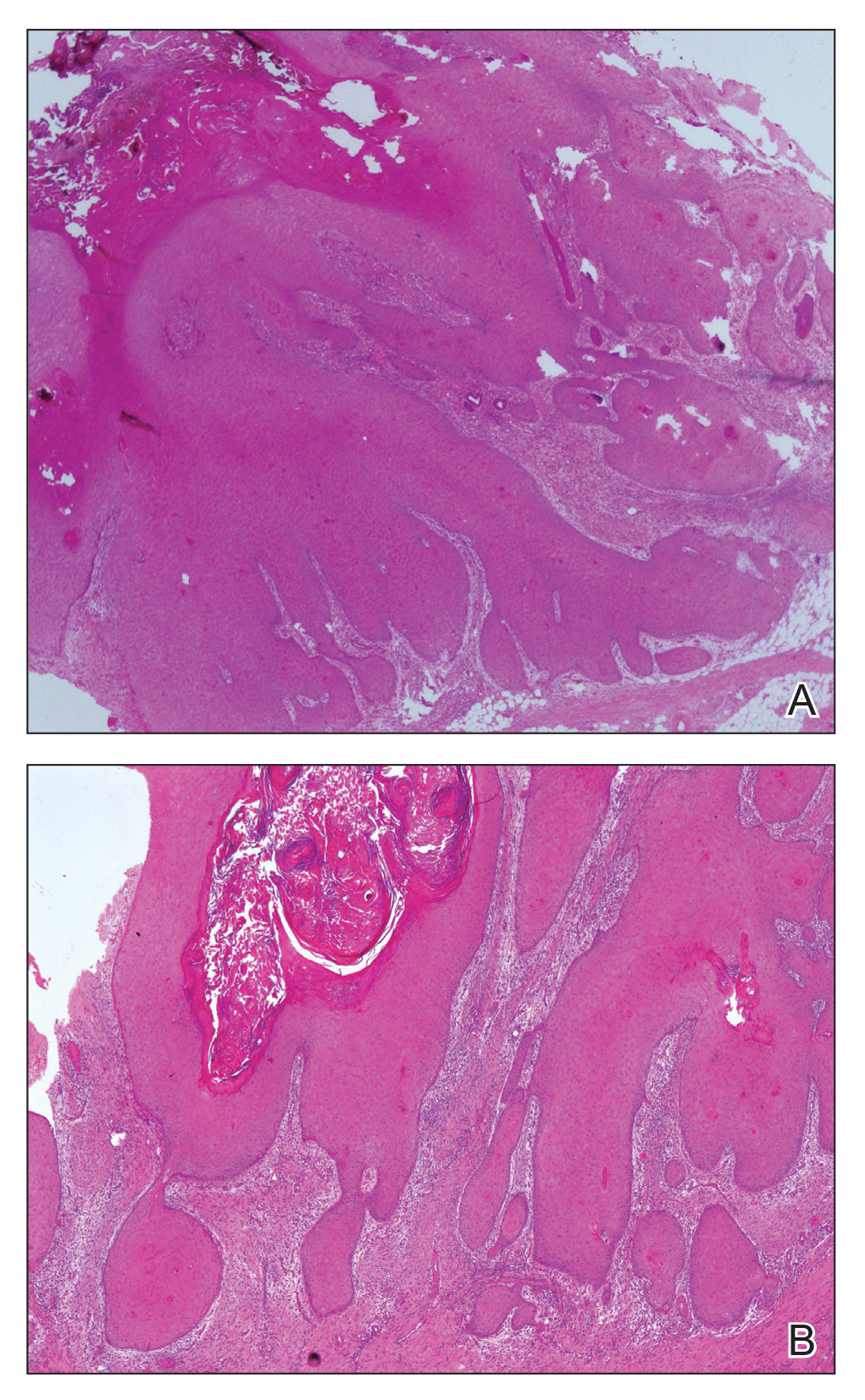

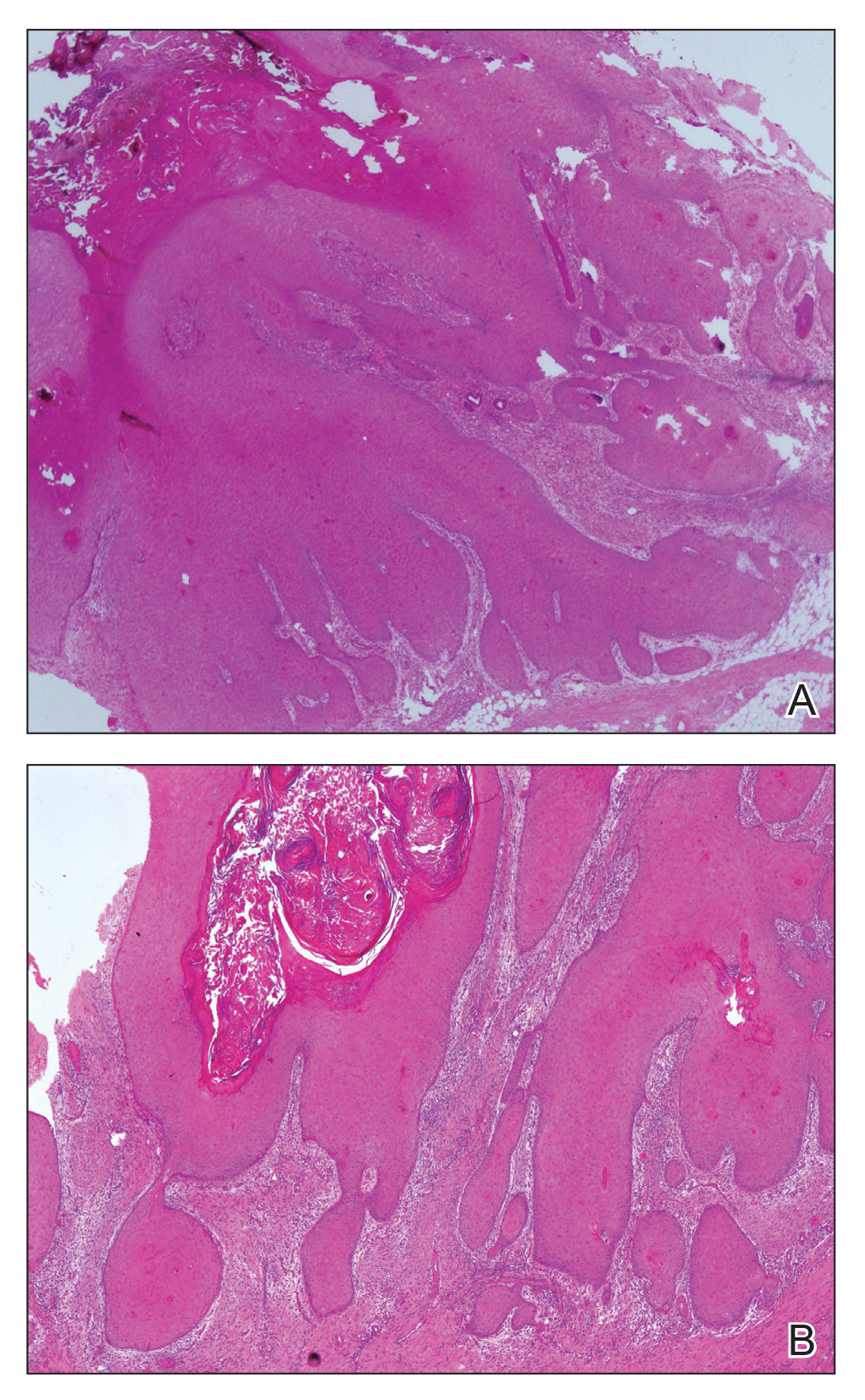

At the initial presentation, radiography of the right big toe revealed porotic signs and cortical irregularity of the distal phalanx. A deep incisional biopsy of the lesion was performed for pathologic and microbiologic analysis. Erlich-Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative, fungal elements could not be observed, and there was no growth in Lowenstein-Jensen medium or Sabouraud dextrose agar. Polymerase chain reaction for human papillomavirus, M tuberculosis, and atypical mycobacterium was negative. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements. Histopathologic examination revealed an exophytic as well as endophytic squamous cell proliferation infiltrating deeper layers of the dermis with a desmoplastic stroma (Figure 2). Slight cytologic atypia was noted. A diagnosis of VC was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings. The patient’s right big toe was amputated by plastic surgery 6 months after the initial presentation.

The term epithelioma cuniculatum was first used in 1954 to describe plantar VC. The term cuniculus is Latin for rabbit nest.3 At the distal part of the plantar surface of the foot, VC presents as an exophytic funguslike mass with abundant keratin-filled sinuses.14 When pressure is applied to the lesion, a greasy, yellowish, foul-smelling material with the consistency of toothpaste emerges from the sinuses. The lesion resembles pyoderma vegetans and may present with secondary infections (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria, fungal infection) and/or ulcerations. Its appearance resembles an inflammatory lesion more than a neoplasm.6 Sometimes the skin surrounding the lesion may be a yellowish color, giving the impression of a plantar wart.3,4 In most cases, in situ hybridization demonstrates a human papillomavirus genome.2-5,10 Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis of VC include chronic inflammation; a cicatrice associated with a condition such as chronic cutaneous tuberculosis, ulcerative leprosy, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, or chronic osteomyelitis4; recurrent trauma3; and/or lichen planus.2,4 In spite of its slow development and benign appearance, VC may cause severe destruction affecting surrounding bony structures and may ultimately require amputation.2,4 In its early stages, VC can be mistaken for a benign tumor or other benign lesion, such as giant seborrheic keratosis, giant keratoacanthoma, eccrine poroma, or verruciform xanthoma, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.5

Histopathologic examination, especially of superficial biopsies, generally reveals squamous cell proliferation demonstrating minimal pleomorphism and cytologic atypia with sparse mitotic figures.4-6 Diagnosis of VC can be challenging if the endophytic proliferation, which characteristically pushes into the dermis and even deeper tissues at the base of the lesion, is not seen. This feature is uncommon in squamous cell carcinomas.3,4,6 Histopathologic detection of koilocytes can lead to difficulty in distinguishing VC from warts.5 The growth of lesions is exophytic in plantar verrucae, whereas in VC it may be either exophytic or endophytic.4 At early stages, it is too difficult to distinguish VC from pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia caused by chronic inflammation, as well as from tuberculosis and subcutaneous mycoses.3,6 In these situations, possible responsible microorganisms must be sought out. Amelanotic malignant melanoma and eccrine poroma also should be considered in the differential diagnosis.3,5 If the biopsy specimen is obtained superficially and is fragmented, the diagnosis is more difficult, making deep biopsies essential in suspicious cases.4 Excision is the best treatment, and Mohs micrographic surgery may be required in some cases.2,3,11 It is important to consider that radiotherapy may lead to anaplastic transformation and metastasis.2 Metastasis to lymph nodes is very rare, and the prognosis is excellent when complete excision is performed.2 Recurrence may be observed.4

Our case of plantar VC is notable because of the patient’s young age, which is uncommon, as the typical age for developing VC is late middle age (ie, fifth and sixth decades of life). A long-standing lesion that is therapy resistant and without a detectable microorganism should be investigated for malignancy by repetitive deep biopsy regardless of the patient’s age, as demonstrated in our case.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- Mc Kee PH, ed. Pathology of the Skin. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby-Wolfe; 1996.

- Schwartz RA, Stoll HL. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: Mc-Graw Hill; 1999:840-856.

- MacKie RM. Epidermal skin tumours. In: Rook A, Wilkinson DS, Ebling FJG, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:1500-1556.

- Yoshtatsu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Van Geertruyden JP, Olemans C, Laporte M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the nail bed. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:327-328.

- Sanchez-Yus E, Velasco E, Robledo A. Verrucous carcinoma of the back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(5 pt 2):947-950.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, Detremmerie O, et al. Demonstration of human papillomavirus type 2 in a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. Dermatology. 1993;187:58-61.

- Mora RG. Microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs’ chemosurgery) for treatment of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:354-362.

- Kathuria S, Rieker J, Jablokow VR, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum): case report with review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1986;31:71-75.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Verrucous carcinoma of skin: epithelioma cuniculatum plantare. Cancer. 1976;38:1710-1716.

- Ho J, Diven DG, Butler PJ, et al. An ulcerating verrucous plaque on the foot. verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547-548, 550-551.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is a rare type of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by a well-differentiated low-grade tumor with a high degree of keratinization. First described by Ackerman1 in 1948, VC presents on the skin or oral and genital mucosae with minimal atypical cytologic findings.1-3 It most commonly is seen in late middle-aged men (85% of cases) and presents as a slow-growing mass, often of more than 10 years’ duration.2,3 Verrucous carcinoma frequently is observed at 3 particular anatomic sites: the oral cavity, known as oral florid papillomatosis; the anogenital area, known as Buschke-Löwenstein tumor; and on the plantar surface, known as epithelioma cuniculatum.2-13

A 19-year-old man presented with an ulcerous lesion on the right big toe of 2 years’ duration. He reported that the lesion had gradually increased in size and was painful when walking. Physical examination revealed an ulcerated lesion on the right big toe with purulent inflammation and necrosis, unclear edges, and border nodules containing a fatty, yellowish, foul-smelling material (Figure 1). Histologic examination of purulent material from deep within the primary lesion revealed gram-negative rods and gram-positive diplococci. Erlich-Ziehl-Neelsen staining and culture in Lowenstein-Jensen medium were negative for mycobacteria. Histologic examination and fungal culture were not diagnostic for fungal infection.

The differential diagnosis included tuberculosis cutis verrucosa, subcutaneous mycoses, swimming pool granuloma, leishmania cutis, chronic pyoderma vegetans, and VC. A punch biopsy of the lesion showed chronic nonspecific inflammation, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A repeat biopsy performed 15 days later also showed a nonspecific inflammation. At the initial presentation, an anti–human immunodeficiency virus test was negative. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was positive and showed a 17-mm induration, and a sputum test was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A chest radiograph was normal. We considered the positive PPD skin test to be clinically insignificant; we did not find an accompanying tuberculosis infection, and the high exposure to atypical tuberculosis in developing countries such as Turkey, which is where the patient resided, often explains a positive PPD test.

At the initial presentation, radiography of the right big toe revealed porotic signs and cortical irregularity of the distal phalanx. A deep incisional biopsy of the lesion was performed for pathologic and microbiologic analysis. Erlich-Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative, fungal elements could not be observed, and there was no growth in Lowenstein-Jensen medium or Sabouraud dextrose agar. Polymerase chain reaction for human papillomavirus, M tuberculosis, and atypical mycobacterium was negative. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements. Histopathologic examination revealed an exophytic as well as endophytic squamous cell proliferation infiltrating deeper layers of the dermis with a desmoplastic stroma (Figure 2). Slight cytologic atypia was noted. A diagnosis of VC was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings. The patient’s right big toe was amputated by plastic surgery 6 months after the initial presentation.

The term epithelioma cuniculatum was first used in 1954 to describe plantar VC. The term cuniculus is Latin for rabbit nest.3 At the distal part of the plantar surface of the foot, VC presents as an exophytic funguslike mass with abundant keratin-filled sinuses.14 When pressure is applied to the lesion, a greasy, yellowish, foul-smelling material with the consistency of toothpaste emerges from the sinuses. The lesion resembles pyoderma vegetans and may present with secondary infections (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria, fungal infection) and/or ulcerations. Its appearance resembles an inflammatory lesion more than a neoplasm.6 Sometimes the skin surrounding the lesion may be a yellowish color, giving the impression of a plantar wart.3,4 In most cases, in situ hybridization demonstrates a human papillomavirus genome.2-5,10 Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis of VC include chronic inflammation; a cicatrice associated with a condition such as chronic cutaneous tuberculosis, ulcerative leprosy, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, or chronic osteomyelitis4; recurrent trauma3; and/or lichen planus.2,4 In spite of its slow development and benign appearance, VC may cause severe destruction affecting surrounding bony structures and may ultimately require amputation.2,4 In its early stages, VC can be mistaken for a benign tumor or other benign lesion, such as giant seborrheic keratosis, giant keratoacanthoma, eccrine poroma, or verruciform xanthoma, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.5

Histopathologic examination, especially of superficial biopsies, generally reveals squamous cell proliferation demonstrating minimal pleomorphism and cytologic atypia with sparse mitotic figures.4-6 Diagnosis of VC can be challenging if the endophytic proliferation, which characteristically pushes into the dermis and even deeper tissues at the base of the lesion, is not seen. This feature is uncommon in squamous cell carcinomas.3,4,6 Histopathologic detection of koilocytes can lead to difficulty in distinguishing VC from warts.5 The growth of lesions is exophytic in plantar verrucae, whereas in VC it may be either exophytic or endophytic.4 At early stages, it is too difficult to distinguish VC from pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia caused by chronic inflammation, as well as from tuberculosis and subcutaneous mycoses.3,6 In these situations, possible responsible microorganisms must be sought out. Amelanotic malignant melanoma and eccrine poroma also should be considered in the differential diagnosis.3,5 If the biopsy specimen is obtained superficially and is fragmented, the diagnosis is more difficult, making deep biopsies essential in suspicious cases.4 Excision is the best treatment, and Mohs micrographic surgery may be required in some cases.2,3,11 It is important to consider that radiotherapy may lead to anaplastic transformation and metastasis.2 Metastasis to lymph nodes is very rare, and the prognosis is excellent when complete excision is performed.2 Recurrence may be observed.4

Our case of plantar VC is notable because of the patient’s young age, which is uncommon, as the typical age for developing VC is late middle age (ie, fifth and sixth decades of life). A long-standing lesion that is therapy resistant and without a detectable microorganism should be investigated for malignancy by repetitive deep biopsy regardless of the patient’s age, as demonstrated in our case.

To the Editor:

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is a rare type of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by a well-differentiated low-grade tumor with a high degree of keratinization. First described by Ackerman1 in 1948, VC presents on the skin or oral and genital mucosae with minimal atypical cytologic findings.1-3 It most commonly is seen in late middle-aged men (85% of cases) and presents as a slow-growing mass, often of more than 10 years’ duration.2,3 Verrucous carcinoma frequently is observed at 3 particular anatomic sites: the oral cavity, known as oral florid papillomatosis; the anogenital area, known as Buschke-Löwenstein tumor; and on the plantar surface, known as epithelioma cuniculatum.2-13

A 19-year-old man presented with an ulcerous lesion on the right big toe of 2 years’ duration. He reported that the lesion had gradually increased in size and was painful when walking. Physical examination revealed an ulcerated lesion on the right big toe with purulent inflammation and necrosis, unclear edges, and border nodules containing a fatty, yellowish, foul-smelling material (Figure 1). Histologic examination of purulent material from deep within the primary lesion revealed gram-negative rods and gram-positive diplococci. Erlich-Ziehl-Neelsen staining and culture in Lowenstein-Jensen medium were negative for mycobacteria. Histologic examination and fungal culture were not diagnostic for fungal infection.

The differential diagnosis included tuberculosis cutis verrucosa, subcutaneous mycoses, swimming pool granuloma, leishmania cutis, chronic pyoderma vegetans, and VC. A punch biopsy of the lesion showed chronic nonspecific inflammation, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. A repeat biopsy performed 15 days later also showed a nonspecific inflammation. At the initial presentation, an anti–human immunodeficiency virus test was negative. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was positive and showed a 17-mm induration, and a sputum test was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A chest radiograph was normal. We considered the positive PPD skin test to be clinically insignificant; we did not find an accompanying tuberculosis infection, and the high exposure to atypical tuberculosis in developing countries such as Turkey, which is where the patient resided, often explains a positive PPD test.

At the initial presentation, radiography of the right big toe revealed porotic signs and cortical irregularity of the distal phalanx. A deep incisional biopsy of the lesion was performed for pathologic and microbiologic analysis. Erlich-Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative, fungal elements could not be observed, and there was no growth in Lowenstein-Jensen medium or Sabouraud dextrose agar. Polymerase chain reaction for human papillomavirus, M tuberculosis, and atypical mycobacterium was negative. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements. Histopathologic examination revealed an exophytic as well as endophytic squamous cell proliferation infiltrating deeper layers of the dermis with a desmoplastic stroma (Figure 2). Slight cytologic atypia was noted. A diagnosis of VC was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings. The patient’s right big toe was amputated by plastic surgery 6 months after the initial presentation.

The term epithelioma cuniculatum was first used in 1954 to describe plantar VC. The term cuniculus is Latin for rabbit nest.3 At the distal part of the plantar surface of the foot, VC presents as an exophytic funguslike mass with abundant keratin-filled sinuses.14 When pressure is applied to the lesion, a greasy, yellowish, foul-smelling material with the consistency of toothpaste emerges from the sinuses. The lesion resembles pyoderma vegetans and may present with secondary infections (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria, fungal infection) and/or ulcerations. Its appearance resembles an inflammatory lesion more than a neoplasm.6 Sometimes the skin surrounding the lesion may be a yellowish color, giving the impression of a plantar wart.3,4 In most cases, in situ hybridization demonstrates a human papillomavirus genome.2-5,10 Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis of VC include chronic inflammation; a cicatrice associated with a condition such as chronic cutaneous tuberculosis, ulcerative leprosy, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, or chronic osteomyelitis4; recurrent trauma3; and/or lichen planus.2,4 In spite of its slow development and benign appearance, VC may cause severe destruction affecting surrounding bony structures and may ultimately require amputation.2,4 In its early stages, VC can be mistaken for a benign tumor or other benign lesion, such as giant seborrheic keratosis, giant keratoacanthoma, eccrine poroma, or verruciform xanthoma, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.5

Histopathologic examination, especially of superficial biopsies, generally reveals squamous cell proliferation demonstrating minimal pleomorphism and cytologic atypia with sparse mitotic figures.4-6 Diagnosis of VC can be challenging if the endophytic proliferation, which characteristically pushes into the dermis and even deeper tissues at the base of the lesion, is not seen. This feature is uncommon in squamous cell carcinomas.3,4,6 Histopathologic detection of koilocytes can lead to difficulty in distinguishing VC from warts.5 The growth of lesions is exophytic in plantar verrucae, whereas in VC it may be either exophytic or endophytic.4 At early stages, it is too difficult to distinguish VC from pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia caused by chronic inflammation, as well as from tuberculosis and subcutaneous mycoses.3,6 In these situations, possible responsible microorganisms must be sought out. Amelanotic malignant melanoma and eccrine poroma also should be considered in the differential diagnosis.3,5 If the biopsy specimen is obtained superficially and is fragmented, the diagnosis is more difficult, making deep biopsies essential in suspicious cases.4 Excision is the best treatment, and Mohs micrographic surgery may be required in some cases.2,3,11 It is important to consider that radiotherapy may lead to anaplastic transformation and metastasis.2 Metastasis to lymph nodes is very rare, and the prognosis is excellent when complete excision is performed.2 Recurrence may be observed.4

Our case of plantar VC is notable because of the patient’s young age, which is uncommon, as the typical age for developing VC is late middle age (ie, fifth and sixth decades of life). A long-standing lesion that is therapy resistant and without a detectable microorganism should be investigated for malignancy by repetitive deep biopsy regardless of the patient’s age, as demonstrated in our case.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- Mc Kee PH, ed. Pathology of the Skin. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby-Wolfe; 1996.

- Schwartz RA, Stoll HL. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: Mc-Graw Hill; 1999:840-856.

- MacKie RM. Epidermal skin tumours. In: Rook A, Wilkinson DS, Ebling FJG, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:1500-1556.

- Yoshtatsu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Van Geertruyden JP, Olemans C, Laporte M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the nail bed. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:327-328.

- Sanchez-Yus E, Velasco E, Robledo A. Verrucous carcinoma of the back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(5 pt 2):947-950.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, Detremmerie O, et al. Demonstration of human papillomavirus type 2 in a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. Dermatology. 1993;187:58-61.

- Mora RG. Microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs’ chemosurgery) for treatment of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:354-362.

- Kathuria S, Rieker J, Jablokow VR, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum): case report with review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1986;31:71-75.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Verrucous carcinoma of skin: epithelioma cuniculatum plantare. Cancer. 1976;38:1710-1716.

- Ho J, Diven DG, Butler PJ, et al. An ulcerating verrucous plaque on the foot. verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547-548, 550-551.

- Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- Mc Kee PH, ed. Pathology of the Skin. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby-Wolfe; 1996.

- Schwartz RA, Stoll HL. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: Mc-Graw Hill; 1999:840-856.

- MacKie RM. Epidermal skin tumours. In: Rook A, Wilkinson DS, Ebling FJG, et al, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:1500-1556.

- Yoshtatsu S, Takagi T, Ohata C, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: report of a case treated with Boyd amputation followed by reconstruction with a free forearm flap. J Dermatol. 2001;28:226-230.

- Van Geertruyden JP, Olemans C, Laporte M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the nail bed. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:327-328.

- Sanchez-Yus E, Velasco E, Robledo A. Verrucous carcinoma of the back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(5 pt 2):947-950.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, Detremmerie O, et al. Demonstration of human papillomavirus type 2 in a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. Dermatology. 1993;187:58-61.

- Mora RG. Microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs’ chemosurgery) for treatment of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:354-362.

- Kathuria S, Rieker J, Jablokow VR, et al. Plantar verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum): case report with review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1986;31:71-75.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Verrucous carcinoma of skin: epithelioma cuniculatum plantare. Cancer. 1976;38:1710-1716.

- Ho J, Diven DG, Butler PJ, et al. An ulcerating verrucous plaque on the foot. verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547-548, 550-551.

Practice Points

- Verrucous carcinoma (VC) frequently is observed at 3 particular anatomic sites: the oral cavity, the anogenital area, and on the plantar surface.

- Plantar VC is rare, with a male predominance and most patients presenting in the fifth to sixth decades of life.

- Differentiating VS from benign tumors may be difficult, especially if only superficial biopsies are taken. Multiple biopsies and a close clinical correlation are required before a definite diagnosis is possible.

Leser-Trélat Sign: A Paraneoplastic Process?

To the Editor:

Leser-Trélat sign is a rare skin condition characterized by the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratoses that rapidly increase in number and size within weeks to months. Co-occurrence has been reported with a large number of malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. We present a case of Leser-Trélat sign that was not associated with an underlying malignancy.

A 44-year-old man was admitted to our dermatology outpatient department with a serpigo on the neck that had grown rapidly in the last month. His medical history and family history were unremarkable. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous 3- to 4-mm brown and slightly verrucous papules on the neck (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the lesion showed acanthosis of predominantly basaloid cells, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, as well as the presence of characteristic horn cysts (Figure 2). He was tested for possible underlying internal malignancy. Liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte count, protein electrophoresis, and whole blood and urine tests were within reference range. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography revealed no signs of pathology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) and tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis were negative. Abdominal, cranial, and thorax computed tomography revealed no abnormalities. Otolaryngologic examinations also were negative. Additional endoscopic analyses, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities. At 1-year follow-up, the seborrheic keratoses remained unchanged. He has remained in good health without specific signs or symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with malignancy but progress without connection to a primary tumor or metastasis and form a group of clinical manifestations. The characteristic progress of paraneoplastic syndromes shows parallelism with the progression of the tumor. The mechanism underlying the development is not known, though the actions of bioactive substances that cause responses in the tumor, such as polypeptide hormones, hormonelike peptides, antibodies or immune complexes, and cytokines or growth factors, have been implicated.1

Although the term paraneoplastic syndrome commonly is used for Leser-Trélat sign, we do not believe it is accurate. As Fink et al2 and Schwengle et al3 indicated, the possibility of the co-occurrence being fortuitous is high. Showing a parallel progress of malignancy with paraneoplastic dermatosis requires that the paraneoplastic syndrome also diminish when the tumor is cured.4 It should then reappear with cancer recurrence or metastasis, which has not been exhibited in many case presentations in the literature.3 Disease regression was observed in only 1 of 3 seborrheic keratosis cases after primary cancer treatment.5

In patients with a malignancy, the sudden increase in seborrheic keratosis is based exclusively on the subjective evaluation of the patient, which may not be reliable. Schwengle et al3 stated that this sudden increase can be related to the awareness level of the patient who had a cancer diagnosis. Bräuer et al6 stated that no plausible definition distinguishes eruptive versus common seborrheic keratoses.

As a result, the results regarding the relationship between malignancy and Leser-Trélat sign are conflicting, and no strong evidence supports the presence of the sign. Only case reports have suggested that Leser-Trélat sign accompanies malignancy. Studies investigating its etiopathogenesis have not revealed a substance that has been released from or as a response to a tumor.

We believe that the presence of eruptive seborrheic keratosis does not necessitate screening for underlying internal malignancies.

- Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic dermatopathology: cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:215-252.

- Fink AM, Filz D, Krajnik G, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses in patients with internal malignancies: a case-control study with a prospective accrual of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1316-1319.

- Schwengle LE, Rampen FH, Wobbes T. Seborrhoeic keratoses and internal malignancies. a case control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:177-179.

- Curth HO. Skin lesions and internal carcinoma. In: Andrade S, Gumport S, Popkin GL, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1976:1308-1341.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trélat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):386-390.

- Bräuer J, Happle R, Gieler U. The sign of Leser-Trélat: fact or myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:77-80.

To the Editor:

Leser-Trélat sign is a rare skin condition characterized by the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratoses that rapidly increase in number and size within weeks to months. Co-occurrence has been reported with a large number of malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. We present a case of Leser-Trélat sign that was not associated with an underlying malignancy.

A 44-year-old man was admitted to our dermatology outpatient department with a serpigo on the neck that had grown rapidly in the last month. His medical history and family history were unremarkable. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous 3- to 4-mm brown and slightly verrucous papules on the neck (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the lesion showed acanthosis of predominantly basaloid cells, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, as well as the presence of characteristic horn cysts (Figure 2). He was tested for possible underlying internal malignancy. Liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte count, protein electrophoresis, and whole blood and urine tests were within reference range. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography revealed no signs of pathology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) and tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis were negative. Abdominal, cranial, and thorax computed tomography revealed no abnormalities. Otolaryngologic examinations also were negative. Additional endoscopic analyses, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities. At 1-year follow-up, the seborrheic keratoses remained unchanged. He has remained in good health without specific signs or symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with malignancy but progress without connection to a primary tumor or metastasis and form a group of clinical manifestations. The characteristic progress of paraneoplastic syndromes shows parallelism with the progression of the tumor. The mechanism underlying the development is not known, though the actions of bioactive substances that cause responses in the tumor, such as polypeptide hormones, hormonelike peptides, antibodies or immune complexes, and cytokines or growth factors, have been implicated.1

Although the term paraneoplastic syndrome commonly is used for Leser-Trélat sign, we do not believe it is accurate. As Fink et al2 and Schwengle et al3 indicated, the possibility of the co-occurrence being fortuitous is high. Showing a parallel progress of malignancy with paraneoplastic dermatosis requires that the paraneoplastic syndrome also diminish when the tumor is cured.4 It should then reappear with cancer recurrence or metastasis, which has not been exhibited in many case presentations in the literature.3 Disease regression was observed in only 1 of 3 seborrheic keratosis cases after primary cancer treatment.5

In patients with a malignancy, the sudden increase in seborrheic keratosis is based exclusively on the subjective evaluation of the patient, which may not be reliable. Schwengle et al3 stated that this sudden increase can be related to the awareness level of the patient who had a cancer diagnosis. Bräuer et al6 stated that no plausible definition distinguishes eruptive versus common seborrheic keratoses.

As a result, the results regarding the relationship between malignancy and Leser-Trélat sign are conflicting, and no strong evidence supports the presence of the sign. Only case reports have suggested that Leser-Trélat sign accompanies malignancy. Studies investigating its etiopathogenesis have not revealed a substance that has been released from or as a response to a tumor.

We believe that the presence of eruptive seborrheic keratosis does not necessitate screening for underlying internal malignancies.

To the Editor:

Leser-Trélat sign is a rare skin condition characterized by the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratoses that rapidly increase in number and size within weeks to months. Co-occurrence has been reported with a large number of malignancies, particularly adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. We present a case of Leser-Trélat sign that was not associated with an underlying malignancy.

A 44-year-old man was admitted to our dermatology outpatient department with a serpigo on the neck that had grown rapidly in the last month. His medical history and family history were unremarkable. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous 3- to 4-mm brown and slightly verrucous papules on the neck (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the lesion showed acanthosis of predominantly basaloid cells, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, as well as the presence of characteristic horn cysts (Figure 2). He was tested for possible underlying internal malignancy. Liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte count, protein electrophoresis, and whole blood and urine tests were within reference range. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography revealed no signs of pathology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 20 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) and tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis were negative. Abdominal, cranial, and thorax computed tomography revealed no abnormalities. Otolaryngologic examinations also were negative. Additional endoscopic analyses, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities. At 1-year follow-up, the seborrheic keratoses remained unchanged. He has remained in good health without specific signs or symptoms suggestive of an underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with malignancy but progress without connection to a primary tumor or metastasis and form a group of clinical manifestations. The characteristic progress of paraneoplastic syndromes shows parallelism with the progression of the tumor. The mechanism underlying the development is not known, though the actions of bioactive substances that cause responses in the tumor, such as polypeptide hormones, hormonelike peptides, antibodies or immune complexes, and cytokines or growth factors, have been implicated.1

Although the term paraneoplastic syndrome commonly is used for Leser-Trélat sign, we do not believe it is accurate. As Fink et al2 and Schwengle et al3 indicated, the possibility of the co-occurrence being fortuitous is high. Showing a parallel progress of malignancy with paraneoplastic dermatosis requires that the paraneoplastic syndrome also diminish when the tumor is cured.4 It should then reappear with cancer recurrence or metastasis, which has not been exhibited in many case presentations in the literature.3 Disease regression was observed in only 1 of 3 seborrheic keratosis cases after primary cancer treatment.5

In patients with a malignancy, the sudden increase in seborrheic keratosis is based exclusively on the subjective evaluation of the patient, which may not be reliable. Schwengle et al3 stated that this sudden increase can be related to the awareness level of the patient who had a cancer diagnosis. Bräuer et al6 stated that no plausible definition distinguishes eruptive versus common seborrheic keratoses.

As a result, the results regarding the relationship between malignancy and Leser-Trélat sign are conflicting, and no strong evidence supports the presence of the sign. Only case reports have suggested that Leser-Trélat sign accompanies malignancy. Studies investigating its etiopathogenesis have not revealed a substance that has been released from or as a response to a tumor.

We believe that the presence of eruptive seborrheic keratosis does not necessitate screening for underlying internal malignancies.

- Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic dermatopathology: cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:215-252.

- Fink AM, Filz D, Krajnik G, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses in patients with internal malignancies: a case-control study with a prospective accrual of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1316-1319.

- Schwengle LE, Rampen FH, Wobbes T. Seborrhoeic keratoses and internal malignancies. a case control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:177-179.

- Curth HO. Skin lesions and internal carcinoma. In: Andrade S, Gumport S, Popkin GL, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1976:1308-1341.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trélat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):386-390.

- Bräuer J, Happle R, Gieler U. The sign of Leser-Trélat: fact or myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:77-80.

- Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic dermatopathology: cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:215-252.

- Fink AM, Filz D, Krajnik G, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses in patients with internal malignancies: a case-control study with a prospective accrual of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1316-1319.

- Schwengle LE, Rampen FH, Wobbes T. Seborrhoeic keratoses and internal malignancies. a case control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:177-179.

- Curth HO. Skin lesions and internal carcinoma. In: Andrade S, Gumport S, Popkin GL, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin: Biology, Diagnosis, and Management. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1976:1308-1341.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trélat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):386-390.

- Bräuer J, Happle R, Gieler U. The sign of Leser-Trélat: fact or myth? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:77-80.