User login

Solitary Exophytic Plaque on the Left Groin

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

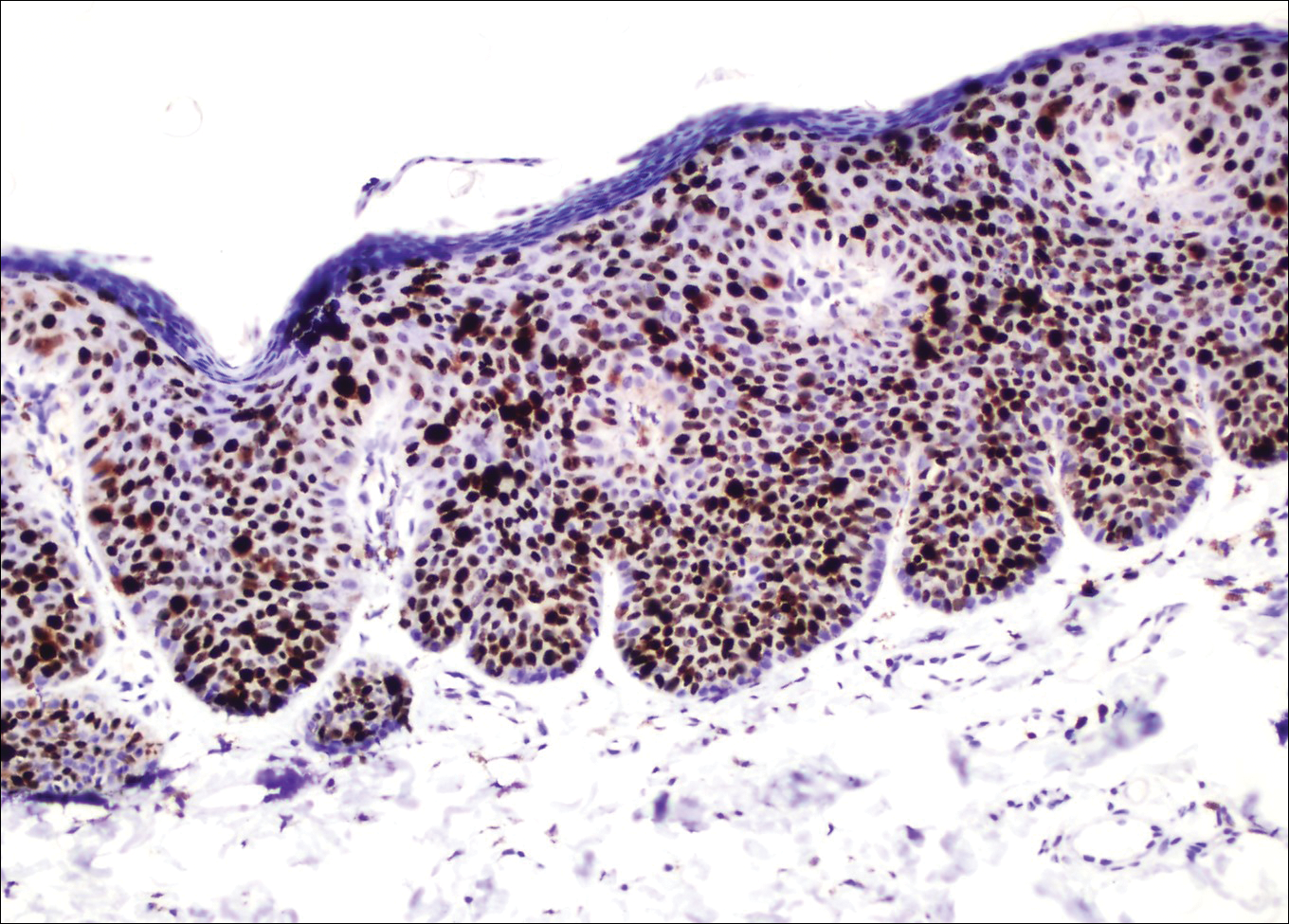

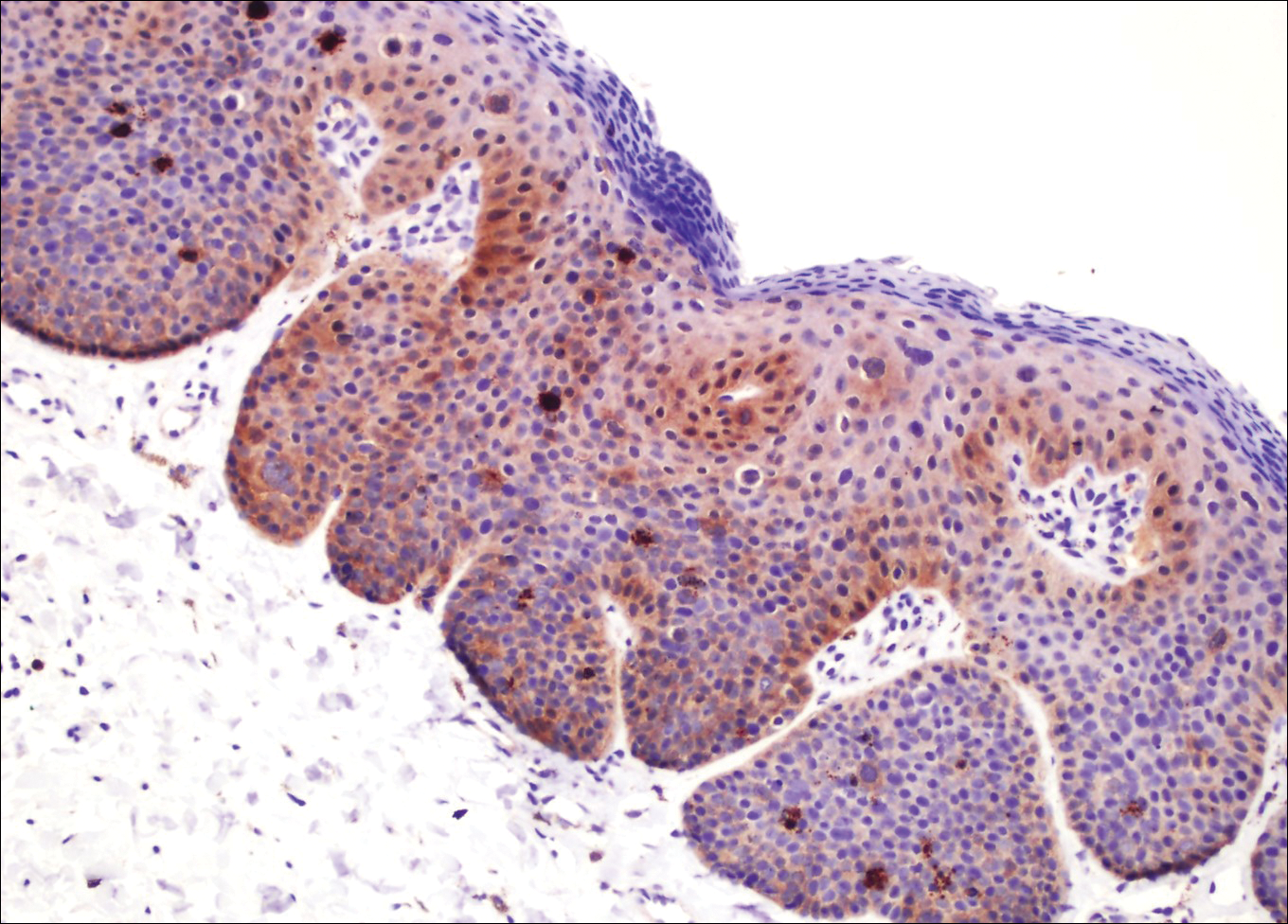

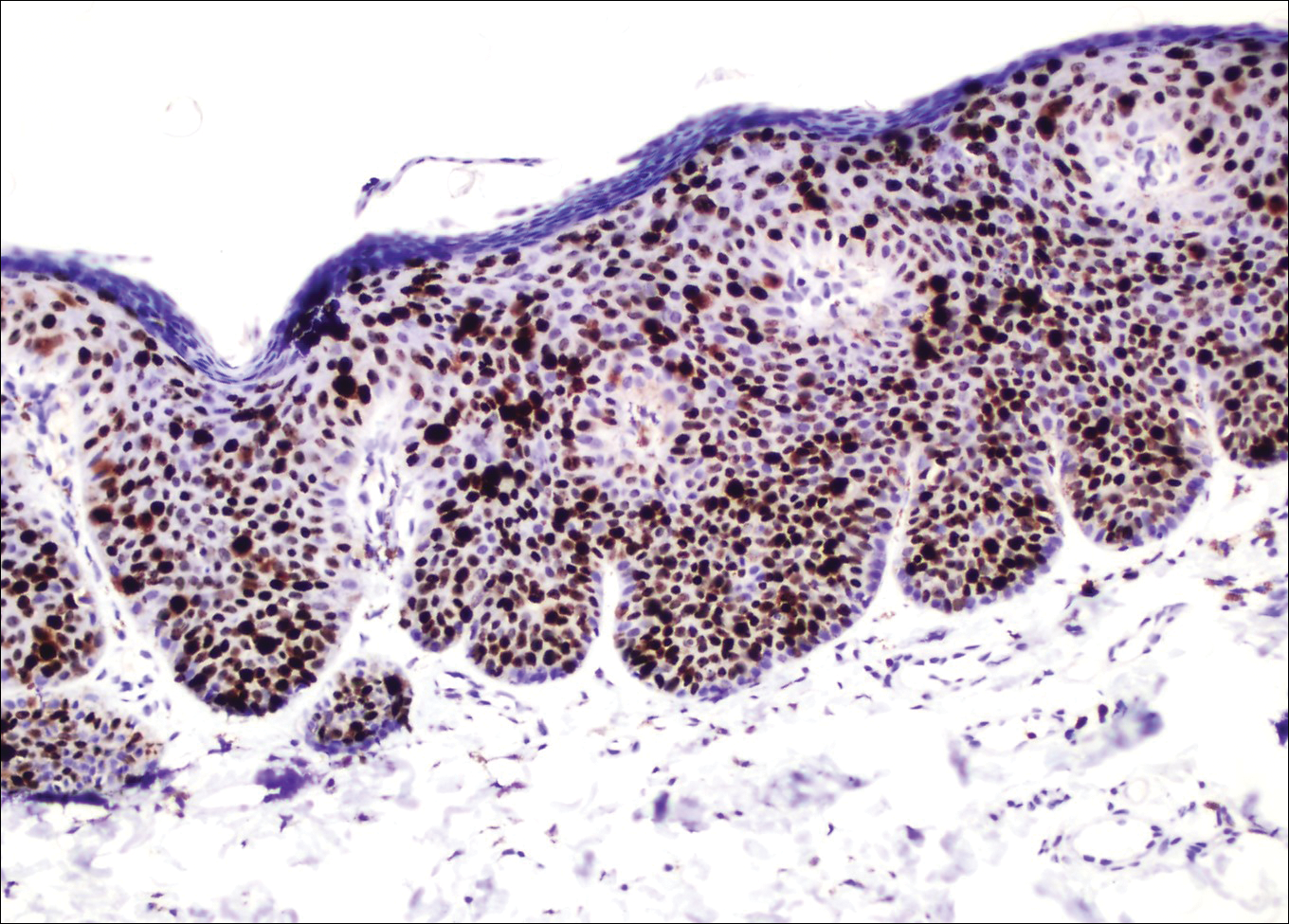

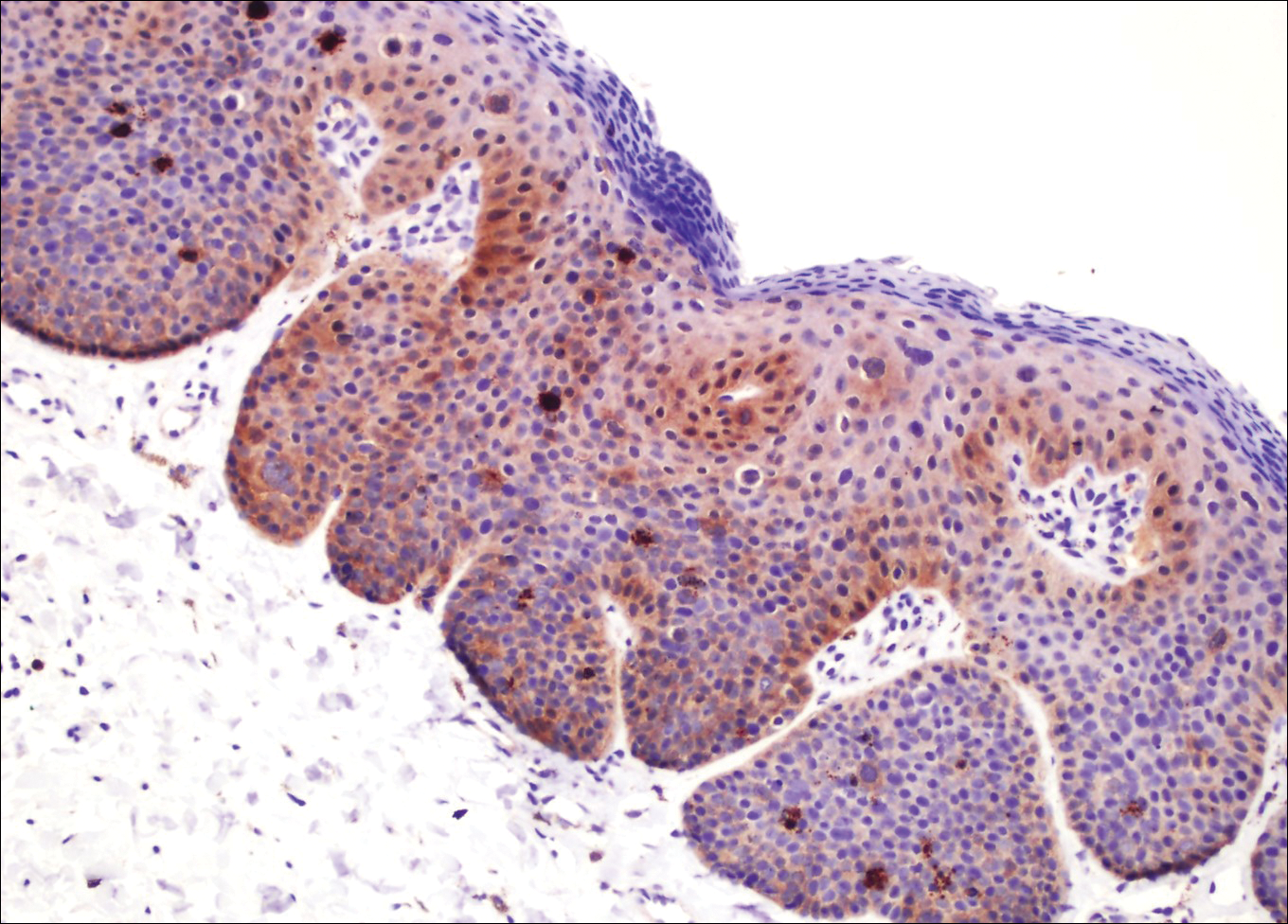

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

A 40-year-old otherwise healthy man presented with an exophytic plaque on the left groin of 1 month's duration. The lesion reportedly emerged as pustules that slowly expanded and coalesced. At an outside institution, cryotherapy was planned for a presumed diagnosis of condyloma acuminatum; however, the patient decided to get a second opinion. He denied recent intake of new drugs. Six months prior he had traveled to China and engaged in unprotected sexual intercourse. Physical examination revealed an approximately 4×2-cm exophytic plaque with a partially eroded and exudative surface on the left inguinal fold. Dermatologic examination, including the oral mucosa, was otherwise normal. Complete blood cell count and sexually transmitted disease panel were unremarkable.

Brown Papules on the Penis

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

A 32-year-old man presented to the outpatient clinic with reddish brown lesions on the penis of 5 months' duration. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple mildly infiltrated, bright reddish brown papules and plaques on the dorsal penis.

Asymptomatic Erythematous Plaques on the Scalp and Face

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Faciale

A biopsy from a scalp lesion showed an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of eosinophils, but lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells also were present. A grenz zone was observed between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis. Perivascular infiltrates were penetrating vessel walls, and hyalinization of the vessel walls also was seen (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated IgG positivity on vessel walls (Figure 2). A diagnosis of granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions was made. Twice daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was started, but after a 10-month course of treatment, there was no notable difference in the lesions.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is an uncommon benign dermatosis of unknown pathogenesis characterized by erythematous, brown, or violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules. Granuloma faciale lesions can be solitary or multiple as well as disseminated and most often occur on the face. Predilection sites include the nose, periauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears; however, lesions also have been reported to occur in extrafacial areas such as the trunk, arms, and legs.1-4 In our patient, multiple plaques were seen on the scalp. Facial lesions usually precede extrafacial lesions, which may present months to several years after the appearance of facial disease; however, according to our patient's history his scalp lesions appeared before the facial lesions.

The differential diagnoses for GF mainly include erythema elevatum diutinum, cutaneous sarcoidosis, cutaneous lymphoma, lupus, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.5 Diagnosis may be established based on a combination of clinical features and skin biopsy results. On histopathologic examination, small-vessel vasculitis usually is present with an infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils and eosinophils.6

It has been suggested that actinic damage plays a role in the etiology of GF.7 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but it is thought that immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of the dermal infiltrate in GF reveals that most lymphocytes are clonally expanded and the process is mediated by interferon gamma.7 Tacrolimus acts by binding and inactivating calcineurin and thus blocking T-cell activation and proliferation, so it is not surprising that topical tacrolimus has been shown to be useful in the management of this condition.8

- Leite I, Moreira A, Guedes R, et al. Granuloma faciale of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1284-1286.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:360-362.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Koplon BS, Wood MG. Granuloma faciale. first reported case in a Negro. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:188-192.

- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Faciale

A biopsy from a scalp lesion showed an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of eosinophils, but lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells also were present. A grenz zone was observed between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis. Perivascular infiltrates were penetrating vessel walls, and hyalinization of the vessel walls also was seen (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated IgG positivity on vessel walls (Figure 2). A diagnosis of granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions was made. Twice daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was started, but after a 10-month course of treatment, there was no notable difference in the lesions.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is an uncommon benign dermatosis of unknown pathogenesis characterized by erythematous, brown, or violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules. Granuloma faciale lesions can be solitary or multiple as well as disseminated and most often occur on the face. Predilection sites include the nose, periauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears; however, lesions also have been reported to occur in extrafacial areas such as the trunk, arms, and legs.1-4 In our patient, multiple plaques were seen on the scalp. Facial lesions usually precede extrafacial lesions, which may present months to several years after the appearance of facial disease; however, according to our patient's history his scalp lesions appeared before the facial lesions.

The differential diagnoses for GF mainly include erythema elevatum diutinum, cutaneous sarcoidosis, cutaneous lymphoma, lupus, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.5 Diagnosis may be established based on a combination of clinical features and skin biopsy results. On histopathologic examination, small-vessel vasculitis usually is present with an infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils and eosinophils.6

It has been suggested that actinic damage plays a role in the etiology of GF.7 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but it is thought that immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of the dermal infiltrate in GF reveals that most lymphocytes are clonally expanded and the process is mediated by interferon gamma.7 Tacrolimus acts by binding and inactivating calcineurin and thus blocking T-cell activation and proliferation, so it is not surprising that topical tacrolimus has been shown to be useful in the management of this condition.8

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Faciale

A biopsy from a scalp lesion showed an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of eosinophils, but lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells also were present. A grenz zone was observed between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis. Perivascular infiltrates were penetrating vessel walls, and hyalinization of the vessel walls also was seen (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated IgG positivity on vessel walls (Figure 2). A diagnosis of granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions was made. Twice daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was started, but after a 10-month course of treatment, there was no notable difference in the lesions.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is an uncommon benign dermatosis of unknown pathogenesis characterized by erythematous, brown, or violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules. Granuloma faciale lesions can be solitary or multiple as well as disseminated and most often occur on the face. Predilection sites include the nose, periauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears; however, lesions also have been reported to occur in extrafacial areas such as the trunk, arms, and legs.1-4 In our patient, multiple plaques were seen on the scalp. Facial lesions usually precede extrafacial lesions, which may present months to several years after the appearance of facial disease; however, according to our patient's history his scalp lesions appeared before the facial lesions.

The differential diagnoses for GF mainly include erythema elevatum diutinum, cutaneous sarcoidosis, cutaneous lymphoma, lupus, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.5 Diagnosis may be established based on a combination of clinical features and skin biopsy results. On histopathologic examination, small-vessel vasculitis usually is present with an infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils and eosinophils.6

It has been suggested that actinic damage plays a role in the etiology of GF.7 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but it is thought that immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of the dermal infiltrate in GF reveals that most lymphocytes are clonally expanded and the process is mediated by interferon gamma.7 Tacrolimus acts by binding and inactivating calcineurin and thus blocking T-cell activation and proliferation, so it is not surprising that topical tacrolimus has been shown to be useful in the management of this condition.8

- Leite I, Moreira A, Guedes R, et al. Granuloma faciale of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1284-1286.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:360-362.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Koplon BS, Wood MG. Granuloma faciale. first reported case in a Negro. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:188-192.

- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

- Leite I, Moreira A, Guedes R, et al. Granuloma faciale of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1284-1286.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:360-362.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Koplon BS, Wood MG. Granuloma faciale. first reported case in a Negro. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:188-192.

- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

An 84-year-old man presented with gradually enlarging, asymptomatic, erythematous to violaceous plaques on the face and scalp of 11 years' duration ranging in size from 0.5×0.5 cm to 10×8 cm. The plaques were unresponsive to treatment with topical steroids. The lesions were nontender with no associated bleeding, burning, or pruritus. The patient denied any trauma to the sites or systemic symptoms. He had a history of essential hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia and had been taking ramipril, tamsulosin, and dutasteride for 5 years. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and routine laboratory findings were within normal range.

Systemic Interferon Alfa Injections for the Treatment of a Giant Orf

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

Resident Pearl

- Human orf lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant. We observed that surgical interventions for treatment of orfs cause a delay in the natural healing process, and other treatment options such as subcutaneous interferon alfa-2a may be used.

In Vivo Confocal Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Onychomycosis

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is a common nail disease that frequently is caused by dermatophytes and is diagnosed by direct microscopy. Conventional diagnostic methods are often time consuming and can produce false-positive or false-negative results. We report a case of onychomycosis diagnosed by confocal microscopy and confirmed with routine potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination and fungal culture. Confocal microscopy is a reliable, practical, and noninvasive technique in the diagnosis of onychomycosis.

A 46-year-old woman presented with yellow-brown discoloration and dystrophy of the toenails (Figure 1) that had become worse over a 5-year period. She was otherwise healthy and had no other dermatologic problems. Examination revealed yellow-brown discoloration, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis of the toenails. Clinically, a diagnosis of onychomycosis was made. Potassium hydroxide examination of a scraping from the subungual region showed fungal elements. Trichophyton rubrum on Sabouraud dextrose agar was determined.

|

We performed both in vivo and in vitro confocal laser scanning microscopic examination of the nail of the right great toe (Figure 2). For the diagnosis of onychomycosis in our case, we used a multilaser reflectance confocal microscope (RCM) with a wavelength of 786 nm. In vivo confocal microscopy of the nail revealed branching hyphae just below the surface of the nail plate. Hyphae were seen as refractile, bright, linear structures along the laminates of the nail.

Onychomycosis is a common condition affecting 5.5% of the population worldwide and representing 20% to 40% of all onychopathies and approximately 30% of cutaneous mycotic infections.1,2 There are many methods available to confirm the clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis by detecting the causative organisms. Direct microscopic examination of the scraping with a KOH culture, histopathologic assessment with periodic acid–Schiff staining, immunofluorescence analysis with calcofluor white staining, enzyme analysis, and polymerase chain reaction can be used for diagnosis of fungal infections. The most frequently used diagnostic method for onychomycosis is KOH examination of the scraping; however, fungal culture and histopathologic examination also can be used in cases having diagnostic difficulties.1,3,4 There are many studies comparing the efficacies of these methods in the literature.5-9

The causative fungal agent should be determined with at least 1 laboratory method due to the high cost, long duration, and serious potential adverse effects of systemic antifungal treatment. Direct microscopic examination with KOH in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is simple, fast, and inexpensive. However, inadequate material, using crystallized KOH for hydrolysis, insufficient or too much hydrolysis of scrapings, inappropriate staining, and not scanning all areas in the microscopy produce false-negative results. Similarly, secondary contamination of hair, cotton, yarn, or air bubbles mimicking fungal structures can cause false-positive results.9,10

Fungal culture is another diagnostic method that is accepted as the gold standard for diagnosis of onychomycosis.9 However, fungal cultures were positive in only 43% to 50% of all cases of onychomycosis that were diagnosed with other methods,11,12 which may be due to the loss of viability and ability of the fungi to grow in culture media during the transport. A major advantage of fungal culture is that the fungal agent can be classified as dermatophyte, nondermatophyte, mold, or yeast. However, culture does determine if the growing fungi is contamination or the real pathogen. Moreover, it is necessary to wait 3 to 4 weeks for culture results. For nondermatophyte fungi this time may be much longer.12

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging method that allows optical en face sectioning of the living tissue with high resolution. Currently, RCM has a wide range of applications, such as the evaluation of both benign and malignant skin lesions in clinical dermatology.13

In vivo RCM was used first by Hongcharu et al.14 The diagnoses of onychomycosis and fungal hyphae were shown both in vivo and in vitro.14 The sensitivity and specificity of confocal examination in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is not known yet. Large clinical trials are needed to assess the sensitivity and specificity of this method in diagnosing fungal infections.

Onychomycosis is a contagious infectious disease characterized by hyphae proliferation in the nail plate. Definitive diagnosis is necessary before treatment because onychomycosis can be mistaken for many infectious or noninfectious skin diseases with nail involvement. Conventional methods are time consuming, laborious, and less reliable. Instead of high-cost procedures, in vivo confocal microscopic examination can be a rapid and reliable diagnostic method for onychomycosis in the near future.

1. Singal A, Khanna D. Onychomycosis: diagnosis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:659-672.

2. Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Onychomycosis—epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:108-116.