User login

Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?

Psychedelics are a class of substances known to produce alterations in consciousness and perception. In the last 2 decades, psychedelic research has garnered increasing attention from scientists, therapists, entrepreneurs, and the public. While many of these compounds remain illegal in the United States and in many parts of the world (Box1), a recent resurrection of psychedelic research has motivated the FDA to designate multiple psychedelic compounds as “breakthrough therapies,” thereby expediting the investigation, development, and review of psychedelic treatments.

Box

The legal landscape of psychedelics is rapidly evolving. Psilocybin use has been decriminalized in many cities in the United States (such as Denver), and some states (such as Oregon) have legalized it for therapeutic use.

It is important to understand the difference between decriminalization and legalization. Decriminalization means the substance is still prohibited under existing laws, but the legal system will choose not to enforce the prohibition. Legalization is the rescinding of laws prohibiting the use of the substance. In the United States, these laws may be state or federal. Despite psilocybin legalization for therapeutic use in Oregon and decriminalization in various cities, psychedelics currently remain illegal under federal law.

Source: Reference 1

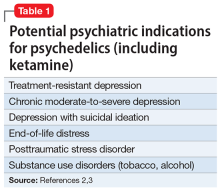

There is growing evidence that psychedelics may be efficacious for treating a range of psychiatric disorders. Potential clinical indications for psychedelics include some forms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders (Table 12,3). In most instances, the clinical use of psychedelics is being investigated and offered in the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, though ketamine is a prominent exception. Ketamine and esketamine are already being used to treat depression, and FDA approval is anticipated for other psychedelics.

This article examines the adverse effect profile of classical (psilocybin [“mushrooms”], lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]/ayahuasca) and nonclassical (the entactogen 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA, known as “ecstasy”] and the dissociative anesthetic ketamine) psychedelics.

Psilocybin

Psilocybin is typically administered as a single dose of 10 to 30 mg and used in conjunction with preintegration and postintegration psychotherapy. Administration of psilocybin typically produces perceptual distortions and mind-altering effects, which are mediated through 5-HT2A brain receptor agonistic action.4 The acute effects last approximately 6 hours.5 While psilocybin has generated promising results in early clinical trials,3 the adverse effects of these agents have received less attention.

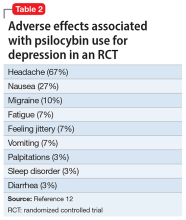

The adverse effect profile of psilocybin in adults appears promising but its powerful psychoactive effects necessitate cautious use.6 It has a very wide therapeutic index, and in a recent meta-analysis of psilocybin for depression, no serious adverse effects were reported in any of the 7 included studies.7 Common adverse effects in the context of clinical use include anxiety, dysphoria, confusion, and an increase in blood pressure and heart rate.6 Due to potential cardiac effects, psilocybin is contraindicated in individuals with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.8 In recreational/nonclinical use, reactions such as suicidality, violence, convulsions, panic attacks, paranoia, confusion, prolonged dissociation, and mania have been reported.9,10 Animal and human studies indicate the risk of abuse and physical dependence is low. Major national surveys indicate low rates of abuse, treatment-seeking, and harm.11 In a recent 6-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) of psilocybin vs escitalopram for depression,12 no serious adverse events were reported. Adverse events reported in the psilocybin group in this trial are listed in Table 2.12

A recent phase 2 double-blind trial of single-dose psilocybin (1 mg, 10 mg, and 25 mg) for treatment-resistant depression (N = 233) sheds more light on the risk of adverse effects.13 The percentage of individuals experiencing adverse effects on Day 1 of administration was high: 61% in the 25 mg psilocybin group. Headache, nausea, fatigue, and dizziness were the most common effects. The incidence of any adverse event in the 25 mg group was 56% from Day 2 to Week 3, and 29% from Week 3 to Week 12. Suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or self-injury occurred in all 3 dose groups. Overall, 14% in the 25 mg group, 17% in the 10 mg group, and 9% in the 1 mg group showed worsening of suicidality from baseline to Week 3. Suicidal behavior was reported by 3 individuals in the 25 mg group after Week 3. The new-onset or worsening of preexisting suicidality with psilocybin reported in this study requires further investigation.

Lysergic acid diethylamide

LSD is similar to psilocybin in its agonistic action at the 5-HT2A brain receptors.4 It is typically administered as a single 100 to 200 μg dose and is used in conjunction with preintegration and postintegration psychotherapy.14 Its acute effects last approximately 12 hours.15

Continue to: Like psilocybin...

Like psilocybin, LSD has a wide therapeutic index. Commonly reported adverse effects of LSD are increased anxiety, dysphoria, and confusion. LSD can also lead to physiological adverse effects, such as increased blood pressure and heart rate, and thus is contraindicated in patients with severe heart disease.6 In a systematic review of the therapeutic use of LSD that included 567 participants,16 2 cases of serious adverse events were reported: a tonic-clonic seizure in a patient with a prior history of seizures, and a case of prolonged psychosis in a 21-year-old with a history of psychotic disorder.

Though few psychedelic studies have examined the adverse effects of these agents in older adults, a recent phase 1 study that recruited 48 healthy older adults (age 55 to 75) found that, compared to placebo, low doses (5 to 20 μg) of LSD 2 times a week for 3 weeks had similar adverse effects, cognitive impairment, or balance impairment.17 The only adverse effect noted to be different between the placebo group and active treatment groups was headache (50% for LSD 10 μg, 25% for LSD 20 μg, and 8% for placebo). Because the dose range (5 to 20 μg) used in this study was substantially lower than the typical therapeutic dose range of 100 to 200 μg, these results should not be interpreted as supporting the safety of LSD at higher doses in older adults.

DMT/ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is a plant-based psychedelic that contains an admixture of substances, including DMT, which acts as a 5-HT2A receptor agonist. In addition to DMT, ayahuasca also contains the alkaloid harmaline, which acts as a monoamine inhibitor. Use of ayahuasca can therefore pose a particular risk for individuals taking other serotonergic or noradrenergic medications or substances. The acute effects of DMT last approximately 4 hours,18 and acute administration of ayahuasca leads to a transient modified state of consciousness that is characterized by introspection, visions, enhanced emotions, and recall of personal memories.19 Research shows ayahuasca has been dosed at approximately 0.36 mg/kg of DMT for 1 dosing session alongside 6 2-hour therapy sessions.20

A recent review by Orsolini et al21 consolidated 40 preclinical, observational, and experimental studies of ayahuasca, and this compound appeared to be safe and well-tolerated; the most common adverse effects were transient emesis and nausea. In an RCT by Palhano-Fontes et al,20 nausea was observed in 71% of participants in the ayahuasca group (vs 26% placebo), vomiting in 57% of participants (vs 0% placebo), and restlessness in 50% of participants (vs 20% placebo). The authors noted that for some participants the ayahuasca session “was not necessarily a pleasant experience,” and was accompanied by psychological distress.20 Vomiting is traditionally viewed as an expected part of the purging process of ayahuasca religious ceremonies. Another review found that there appears to be good long-term tolerability of ayahuasca consumption among individuals who use this compound in religious ceremonies.22

MDMA

Entactogens (or empathogens) are a class of psychoactive substances that produce experiences of emotional openness and connection. MDMA is an entactogen known to release serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine by inhibiting reuptake.23 This process leads to the stimulation of neurohormonal signaling of oxytocin, cortisol, and other signaling molecules such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor.24 Memory reconsolidation and fear extinction may also play a therapeutic role, enabled by reduced activity in the amygdala and insula, and increased connectivity between the amygdala and hippocampus.24 MDMA has been reported to enhance feelings of well-being and increase prosocial behavior.25 In the therapeutic setting, MDMA has been generally dosed at 75 to 125 mg in 2 to 3 sessions alongside 10 therapy sessions. Administration of MDMA gives the user a subjective experience of energy and distortions in time and perception.26 These acute effects last approximately 2 to 4 hours.27

Continue to: A meta-analysis...

A meta-analysis of 5 RCTs of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD in adults demonstrated that MDMA was well-tolerated, and few serious adverse events were reported.28 Two trials from 2018 that were included in this meta-analysis—Mithoefer et al29 and Ot’alora et al30—illustrate the incidence of specific adverse effects. In a randomized, double-blind trial of 26 veterans and first responders with chronic PTSD, Mithoefer et al29 found the most commonly reported reactions during experimental sessions with MDMA were anxiety (81%), headache (69%), fatigue (62%), muscle tension (62%), and jaw clenching or tight jaw (50%). The most commonly reported reactions during 7 days of contact were fatigue (88%), anxiety (73%), insomnia (69%), headache (46%), muscle tension (46%), and increased irritability (46%). One instance of suicidal ideation was severe enough to require psychiatric hospitalization (this was the only instance of suicidal ideation among the 106 patients in the meta-analysis by Bahji et al28); the patient subsequently completed the trial. Transient elevation in pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature were noted during sessions that did not require medical intervention.29 Ot’alora et al30 found similar common adverse reactions: anxiety, dizziness, fatigue, headache, jaw clenching, muscle tension, and irritability. There were no serious adverse effects.

While the use of MDMA in controlled interventional settings has resulted in relatively few adverse events, robust literature describes the risks associated with the nonclinical/recreational use of MDMA. In cases of MDMA toxicity, death has been reported.31 Acutely, MDMA may lead to sympathomimetic effects, including serotonin syndrome.31 Longer-term studies of MDMA users have found chronic recreational use to be associated with worse sleep, poor mood, anxiety disturbances, memory deficits, and attention problems.32 MDMA has also been found to have moderate potential for abuse.33

Ketamine/esketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic with some hallucinogenic effects. It is an N-methyl-

Esketamine, the S(+)-enantiomer of ketamine, is also an NDMA antagonist. It has been developed as an intranasal formulation, typically dosed between 56 and 84 mg 2 times a week for 1 month, once a week for the following month, and once every 1 to 2 weeks thereafter.35 In most ketamine and esketamine trials, these compounds have been used without psychotherapy, although some interventions have integrated psychotherapy with ketamine treatment.36

Bennett et al37 elaborated on 3 paradigms for ketamine treatment: biochemical, psychotherapeutic, and psychedelic. The biochemical model examines the neurobiological effects of the medication. The psychotherapeutic model views ketamine as a way of assisting the psychotherapy process. The psychedelic model utilizes ketamine’s dissociative and psychedelic properties to induce an altered state of consciousness for therapeutic purposes and psychospiritual exploration.

Continue to: A systematic review...

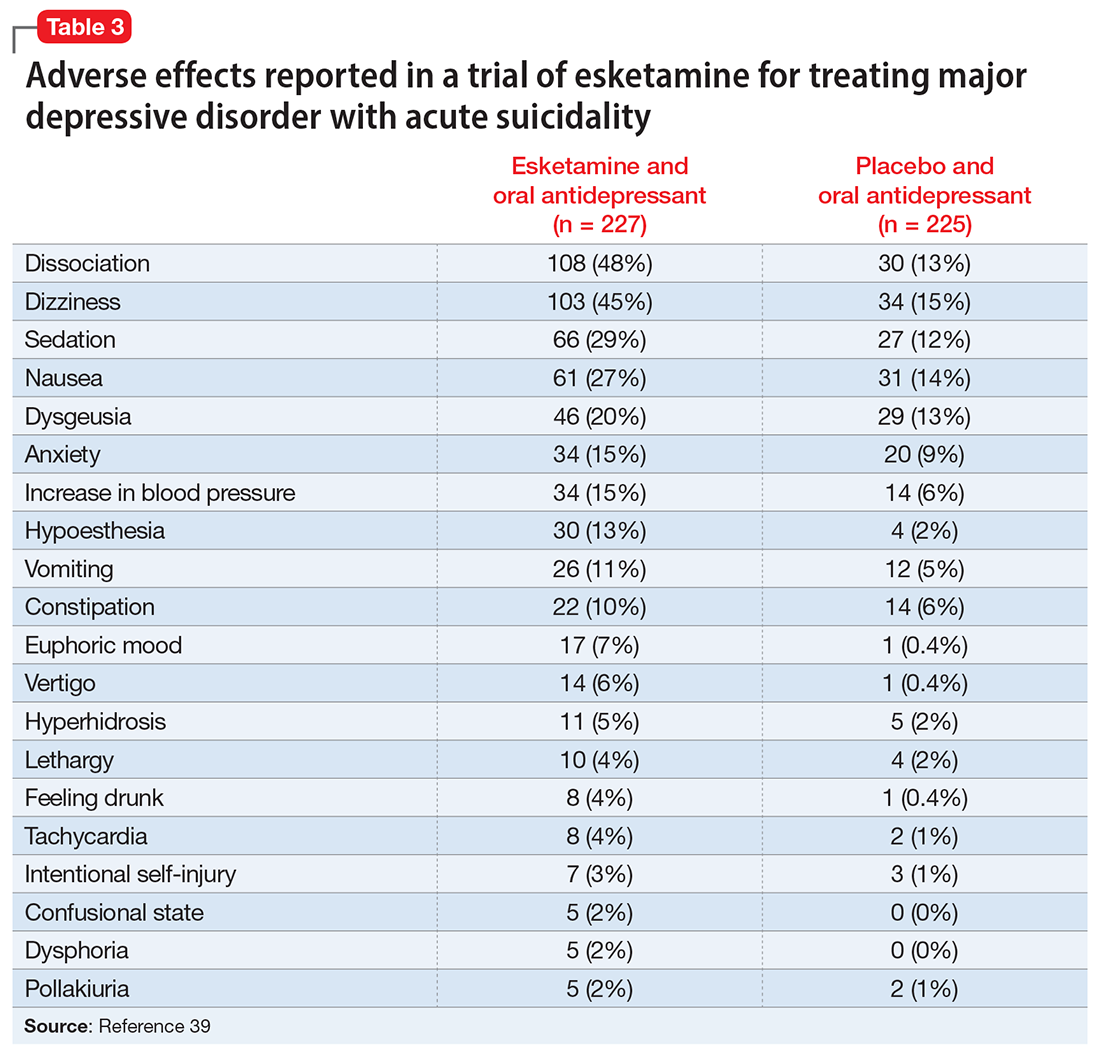

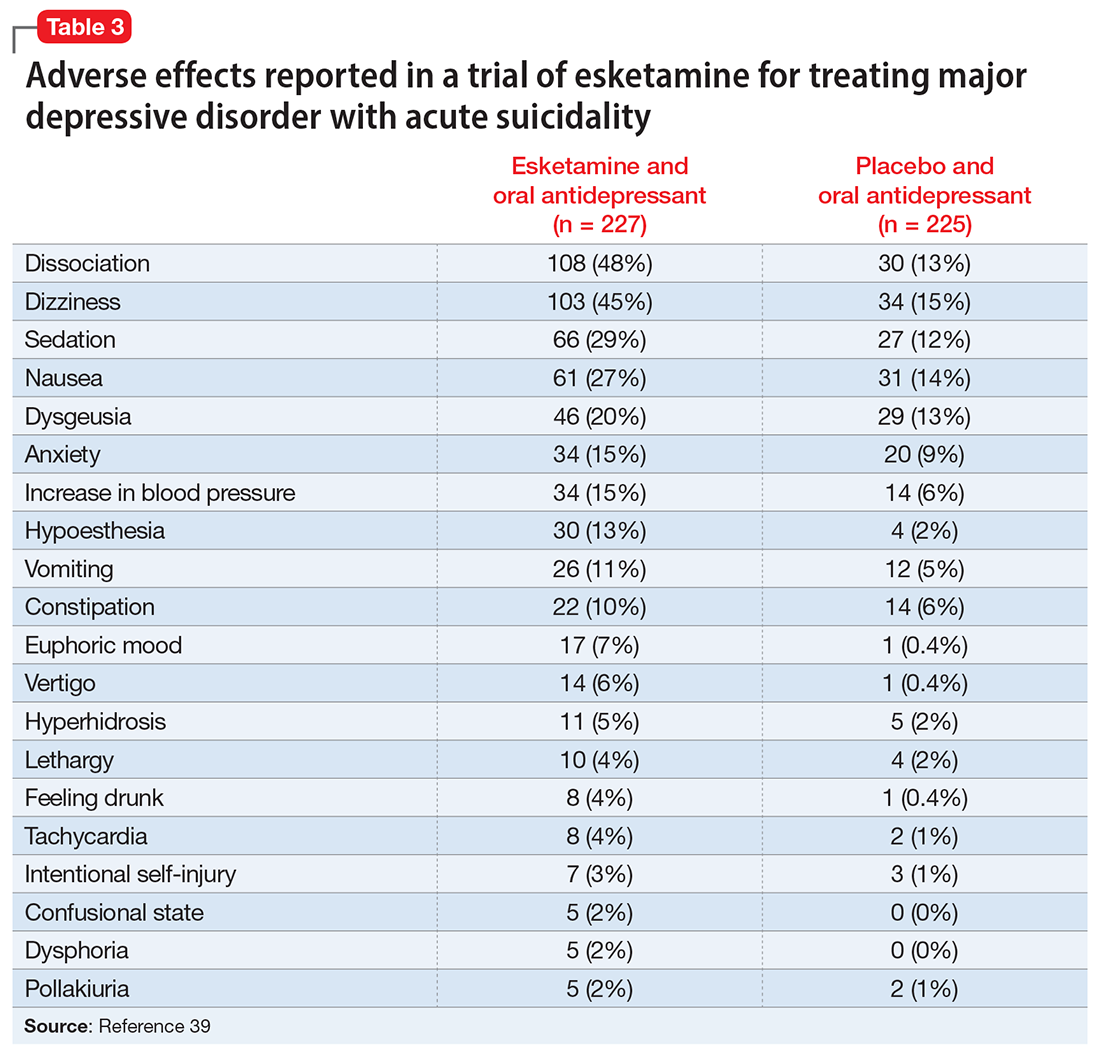

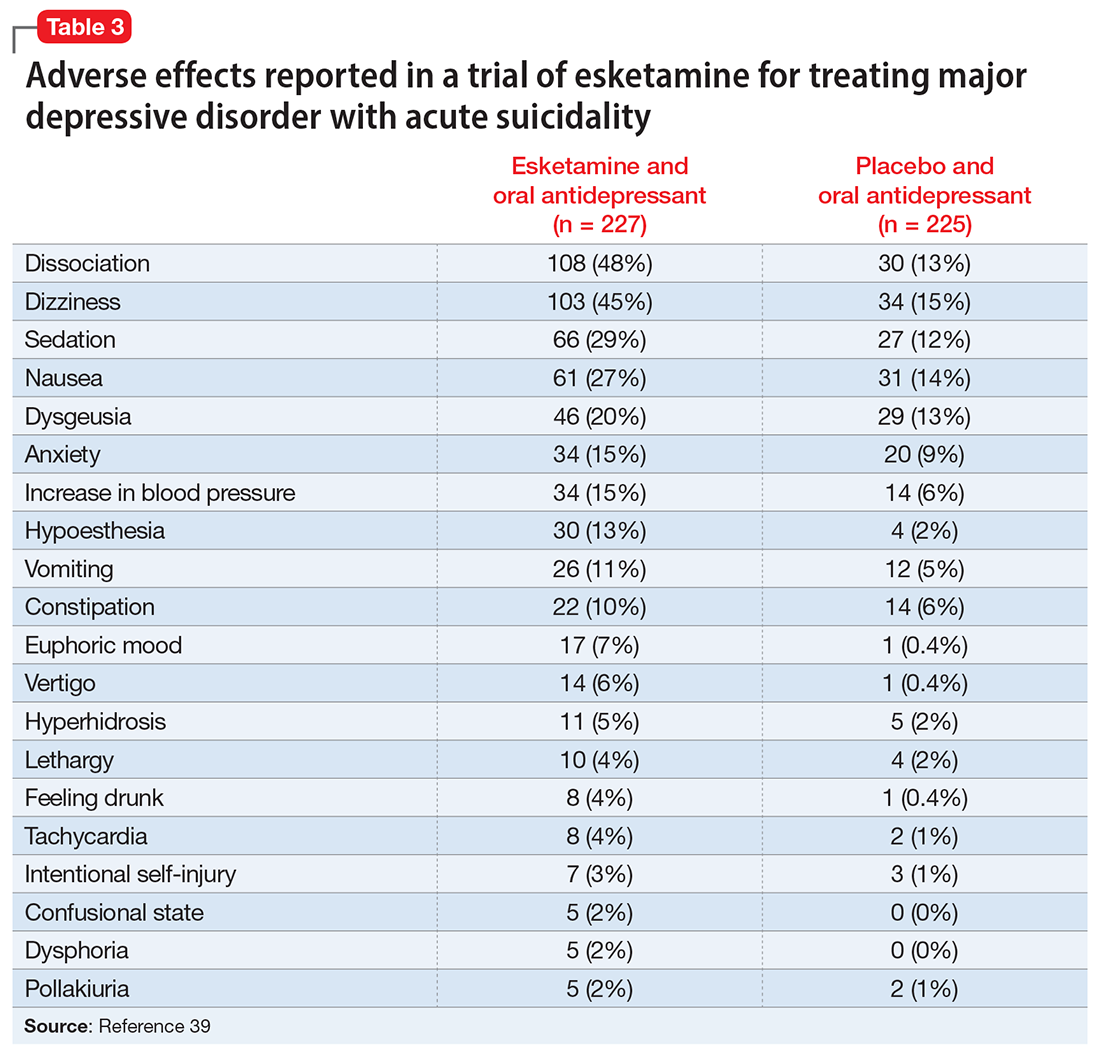

A systematic review of the common adverse effects associated with ketamine use in clinical trials for depression reported dissociation, sedation, perceptual disturbances, anxiety, agitation, euphoria, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, and dizziness.38 Adverse effects experienced with esketamine in clinical trials include dissociation, dizziness, sedation, hypertension, hypoesthesia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and euphoric mood (Table 339). A recent systemic review found both ketamine and esketamine demonstrated higher adverse events than control conditions. IV ketamine also demonstrated lower dropouts and adverse events when compared to intranasal esketamine.40

Nonclinical/recreational use of ketamine is notable for urinary toxicity; 20% to 30% of frequent users of ketamine experience urinary problems that can range from ketamine-induced cystitis to hydronephrosis and kidney failure.41 Liver toxicity has also been reported with chronic use of high-dose ketamine. Ketamine is liable to abuse, dependence, and tolerance. There is evidence that nonclinical use of ketamine may lead to morbidity; impairment of memory, cognition, and attention; and urinary, gastric, and hepatic pathology.42

The FDA prescribing information for esketamine lists aneurysmal vascular disease, arteriovenous malformation, and intracerebral hemorrhage as contraindications.39 Patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions and risk factors may be at increased risk of adverse effects due to an increase in blood pressure. Esketamine can impair attention, judgment, thinking, reaction speed, and motor skills. Other adverse effects of esketamine noted in the prescribing information include dissociation, dizziness, nausea, sedation, vertigo, hypoesthesia, anxiety, lethargy, vomiting, feeling drunk, and euphoric mood.39A study of postmarketing safety concerns with esketamine using reports submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) revealed signals for suicidal ideation (reporting odds ratio [ROR] 24.03; 95% CI, 18.72 to 30.84), and completed suicide (ROR 5.75; 95% CI, 3.18 to 10.41).43 The signals for suicidal and self-injurious ideation remained significant when compared to venlafaxine in the FAERS database, while suicide attempts and fatal suicide attempts were no longer significant.43 Concerns regarding acute ketamine withdrawal have also been described in case reports.44

Other safety considerations of psychedelics

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is a rare condition associated with hallucinogen use. It is characterized by the recurrence of perceptual disturbances that an individual experienced while using hallucinogenic substances that creates significant distress or impairment.45 Because HPPD is a rare disorder, the exact prevalence is not well characterized, but DSM-5 suggests it is approximately 4.2%.46 HPPD is associated with numerous psychoactive substances, including psilocybin, ayahuasca, MDMA, and ketamine, but is most associated with LSD.45 HPPD is more likely to arise in individuals with histories of psychiatric illness or substance use disorders.47

Serotonin toxicity and other serotonergic interactions

Serotonin toxicity is a risk of serotonergic psychedelics, particularly when such agents are used in combination with serotonergic psychotropic medications. The most severe manifestation of serotonin toxicity is serotonin syndrome, which manifests as a life-threatening condition characterized by myoclonus, rigidity, agitation, delirium, and unstable cardiovascular functioning. Many psychedelic compounds have transient serotonin-related adverse effects, but serotonin toxicity due to psychedelic use is rare.48 Due to their mechanism of action, classical psychedelics are relatively safe in combination with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. MDMA is a serotonin-releasing agent that has a higher risk of serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crisis when used in combination with MAOIs.48

Boundary violations in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy

A key task facing psychedelic research is to establish parameters for the safe and ethical use of these agents. This is particularly relevant given the hype that surrounds the psychedelic resurgence and what we know about the controversial history of these substances. Anderson et al49 argued that “psychedelics can have lingering effects that include increased suggestibility and affective instability, as well as altered ego structure, social behaviour, and philosophical worldview. Stated simply, psychedelics can induce a vulnerable state both during and after treatment sessions.”

Continue to: Psychedelic treatment...

Psychedelic treatments such as psilocybin and MDMA are typically offered within the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and some researchers have raised concerns regarding boundary violations,50 given the patients’ particularly vulnerable states. In addition to concerns about sexual harassment, the financial exploitation of older adults is also a possible risk.51

Caveats to consider

Novel psychedelics therapies have demonstrated promising preliminary results for a broad range of psychiatric indications, including depression, end-of-life distress, substance use disorders, PTSD, and improving well-being. To date, psychedelics are generally well-tolerated in adults in clinical trials.

However, when it comes to adverse effects, there are challenges in regards to interpreting the psychedelic state.52 Some consider any unpleasant or unsettling psychedelic experience as an adverse reaction, while others consider it part of the therapeutic process. This is exemplified by the case of vomiting during ayahuasca ceremonies, which is generally considered part of the ritual. In such instances, it is essential to obtain informed consent and ensure participants are aware of these aspects of the experience. Compared to substances such as alcohol, opioids, and cocaine, psychedelics are remarkably safe from a physiological perspective, especially with regards to the risks of toxicity, mortality, and dependence.53 Their psychological safety is less established, and more caution and research is needed. The high incidence of adverse effects and suicidality noted in the recent phase 2 trial of psilocybin in treatment resistant depression are a reminder of this.13

There is uncertainty regarding the magnitude of risk in real-world clinical practice, particularly regarding addiction, suicidality, and precipitation or worsening of psychotic disorders. For example, note the extensive exclusion criteria used in the psilocybin vs escitalopram RCT by Carhart-Harris et al12: currently or previously diagnosed psychotic disorder, immediate family member with a diagnosed psychotic disorder, significant medical comorbidity (eg, diabetes, epilepsy, severe cardiovascular disease, hepatic or renal failure), history of suicide attempts requiring hospitalization, history of mania, pregnancy, and abnormal QT interval prolongation, among others. It would be prudent to keep these contraindications in mind regarding the clinical use of psychedelics in the future. This is particularly important in older adults because such patients often have substantial medical comorbidities and are at greater risk for adverse effects. For ketamine, research has implicated the role of mu opioid agonism in mediating ketamine’s antidepressant effects.54 This raises concerns about abuse, dependence, and addiction, especially with long-term use. There are also concerns regarding protracted withdrawal symptoms and associated suicidality.55

The therapeutic use of psychedelics is an exciting and promising avenue, with ongoing research and a rapidly evolving literature. An attitude of cautious optimism is warranted, but efficacy and safety should be demonstrated in well-designed and rigorous trials with adequate long-term follow-up before routine clinical use is recommended.

Bottom Line

In clinical trials for psychiatric disorders, psychedelics have been associated with a range of cognitive, psychiatric, and psychoactive adverse effects but generally have been well-tolerated, with a low incidence of serious adverse effects.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. Position Statement on the Use of Psychedelic and Empathogenic Agents for Mental Health Conditions. Updated July 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/d5c13619-ca1f-491f-a7a8-b7141c800904/Position-Use-of-Psychedelic-Empathogenic-Agents.pdf

- Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research. https://hopkinspsychedelic.org/

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). https://maps.org/

Drug Brand Names

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. The current legal status of psychedelics in the United States. Investing News Network. August 23, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://investingnews.com/legal-status-of-psychedelics-in-the-united-states/

2. Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, et al. Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(5):391-410.

3. Nutt D, Carhart-Harris R. The current status of psychedelics in psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(2):121-122.

4. Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(2):264-355.

5. Hasler F, Grimberg U, Benz MA et al. Acute psychological and physiological effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-effect study. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172:145-156.

6. Johnson MW, Hendricks PS, Barrett FS, et al. Classic psychedelics: an integrative review of epidemiology, therapeutics, mystical experience, and brain network function. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;197:83-102.

7. Li NX, Hu YR, Chen WN, et al. Dose effect of psilocybin on primary and secondary depression: a preliminary systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:26-34.

8. Johnson MW, Richards WA, Griffiths RR. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):603-620.

9. Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ. User perceptions of the benefits and harms of hallucinogenic drug use: a web-based questionnaire study. J Subst Use. 2010;15(4):283-300.

10. van Amsterdam J, Opperhuizen A, van den Brink W. Harm potential of magic mushroom use: a review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;59(3):423-429.

11. Johnson MW, Griffiths RR, Hendricks PS, et al. The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:143-166.

12. Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl Med. 2021;384(15):1402-1411.

13. Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, et al. Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant Episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(18):1637-1648.

14. Galvão-Coelho NL, Marx W, Gonzalez M, et al. Classic serotonergic psychedelics for mood and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of mood disorder patients and healthy participants. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(2):341-354.

15. Schmid Y, Enzler F, Gasser P, et al. Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(8):544-553.

16. Fuentes JJ, Fonseca F, Elices M, et al. Therapeutic use of LSD in psychiatry: a systematic review of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:943.

17. Family N, Maillet EL, Williams LTJ, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of low dose lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in healthy older volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020;237(3):841-853.

18. Frecska E, Bokor P, Winkelman M. The therapeutic potentials of ayahuasca: possible effects against various diseases of civilization. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:35.

19. Domínguez-Clavé E, Solar J, Elices M, et al. Ayahuasca: pharmacology, neuroscience and therapeutic potential. Brain Res Bull. 2016;126(Pt 1):89-101.

20. Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(4):655-663.

21. Orsolini L, Chiappini S, Papanti D, et al. How does ayahuasca work from a psychiatric perspective? Pros and cons of the entheogenic therapy. Hum Psychopharmacol: Clin Exp. 2020;35(3):e2728.

22. Durante Í, Dos Santos RG, Bouso JC, et al. Risk assessment of ayahuasca use in a religious context: self-reported risk factors and adverse effects. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43(4):362-369.

23. Sessa B, Higbed L, Nutt D. A review of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:138.

24. Feduccia AA, Mithoefer MC. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: are memory reconsolidation and fear extinction underlying mechanisms? Progress Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(Pt A):221-228.

25. Hysek CM, Schmid Y, Simmler LD, et al. MDMA enhances emotional empathy and prosocial behavior. Soc Cogn Affective Neurosc. 2014;9(11):1645-1652.

26. Kalant H. The pharmacology and toxicology of “ecstasy” (MDMA) and related drugs. CMAJ. 2001;165(7):917-928.

27. Dumont GJ, Verkes RJ. A review of acute effects of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(2):176-187.

28. Bahji A, Forsyth A, Groll D, et al. Efficacy of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96:109735.

29. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

30. Ot’alora GM, Grigsby J, Poulter B, et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized phase 2 controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(12):1295-1307.

31. Steinkellner T, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH, et al. The ugly side of amphetamines: short- and long-term toxicity of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘Ecstasy’), methamphetamine and D-amphetamine. Biol Chem. 2011;392(1-2):103-115.

32. Montoya AG, Sorrentino R, Lukas SE, et al. Long-term neuropsychiatric consequences of “ecstasy” (MDMA): a review. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):212-220.

33. Yazar‐Klosinski BB, Mithoefer MC. Potential psychiatric uses for MDMA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101(2):194-196.

34. Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, et al. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):399-405.

35. Thase M, Connolly KR. Ketamine and esketamine for treating unipolar depression in adults: administration, efficacy, and adverse effects. Wolters Kluwer; 2019. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ketamine-and-esketamine-for-treating-unipolar-depression-in-adults-administration-efficacy-and-adverse-effects

36. Dore J, Turnispeed B, Dwyer S, et al. Ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP): patient demographics, clinical data and outcomes in three large practices administering ketamine with psychotherapy. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2019;51(2):189-198.

37. Bennett R, Yavorsky C, Bravo G. Ketamine for bipolar depression: biochemical, psychotherapeutic, and psychedelic approaches. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:867484.

38. Short B, Fong J, Galvez V, et al. Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):65-78.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. SPRAVATO® (esketamine). Prescribing information. Janssen; 2020. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/211243s004lbl.pdf

40. Bahji A, Vazquez GH, Zarate CA Jr. Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affective Disord. 2021;278:542-555.

41. Castellani D, Pirola GM, Gubbiotti M, et al. What urologists need to know about ketamine-induced uropathy: a systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(4):1049-1062.

42. Bokor G, Anderson PD. Ketamine: an update on its abuse. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27(6):582-586.

43. Gastaldon, C, Raschi E, Kane JM, et al. Post-marketing safety concerns with esketamine: a disproportionality analysis of spontaneous reports submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(1):41-48.

44. Roxas N, Ahuja C, Isom J, et al. A potential case of acute ketamine withdrawal: clinical implications for the treatment of refractory depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(7):588-591.

45. Orsolini L, Papanti GD, De Berardis D, et al. The “Endless Trip” among the NPS users: psychopathology and psychopharmacology in the hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder. A systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:240.

46. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatry Association; 2013.

47. Martinotti G, Santacroce R, Pettorruso M, et al. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: etiology, clinical features, and therapeutic perspectives. Brain Sci. 2018;8(3):47.

48. Malcolm B, Thomas K. Serotonin toxicity of serotonergic psychedelics. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(6):1881-1891.

49. Anderson BT, Danforth AL, Grob CS. Psychedelic medicine: safety and ethical concerns. Lancet Psychiatry, 2020;7(10):829-830.

50. Goldhill O. Psychedelic therapy has a sexual abuse problem. QUARTZ. March 3, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://qz.com/1809184/psychedelic-therapy-has-a-sexual-abuse-problem-3/

51. Goldhill O. A psychedelic therapist allegedly took millions from a Holocaust survivor, highlighting worries about elders taking hallucinogens. STAT News. April 21, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.statnews.com/2022/04/21/psychedelic-therapist-allegedly-took-millions-from-holocaust-survivor-highlighting-worries-about-elders-taking-hallucinogens/

52. Strassman RJ. Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172(10):577-595.

53. Nutt D. Drugs Without the Hot Air: Minimising the Harms of Legal and Illegal Drugs. UIT Cambridge Ltd; 2012.

54. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

55. Schatzberg AF. A word to the wise about intranasal esketamine. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):422-424.

Psychedelics are a class of substances known to produce alterations in consciousness and perception. In the last 2 decades, psychedelic research has garnered increasing attention from scientists, therapists, entrepreneurs, and the public. While many of these compounds remain illegal in the United States and in many parts of the world (Box1), a recent resurrection of psychedelic research has motivated the FDA to designate multiple psychedelic compounds as “breakthrough therapies,” thereby expediting the investigation, development, and review of psychedelic treatments.

Box

The legal landscape of psychedelics is rapidly evolving. Psilocybin use has been decriminalized in many cities in the United States (such as Denver), and some states (such as Oregon) have legalized it for therapeutic use.

It is important to understand the difference between decriminalization and legalization. Decriminalization means the substance is still prohibited under existing laws, but the legal system will choose not to enforce the prohibition. Legalization is the rescinding of laws prohibiting the use of the substance. In the United States, these laws may be state or federal. Despite psilocybin legalization for therapeutic use in Oregon and decriminalization in various cities, psychedelics currently remain illegal under federal law.

Source: Reference 1

There is growing evidence that psychedelics may be efficacious for treating a range of psychiatric disorders. Potential clinical indications for psychedelics include some forms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders (Table 12,3). In most instances, the clinical use of psychedelics is being investigated and offered in the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, though ketamine is a prominent exception. Ketamine and esketamine are already being used to treat depression, and FDA approval is anticipated for other psychedelics.

This article examines the adverse effect profile of classical (psilocybin [“mushrooms”], lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]/ayahuasca) and nonclassical (the entactogen 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA, known as “ecstasy”] and the dissociative anesthetic ketamine) psychedelics.

Psilocybin

Psilocybin is typically administered as a single dose of 10 to 30 mg and used in conjunction with preintegration and postintegration psychotherapy. Administration of psilocybin typically produces perceptual distortions and mind-altering effects, which are mediated through 5-HT2A brain receptor agonistic action.4 The acute effects last approximately 6 hours.5 While psilocybin has generated promising results in early clinical trials,3 the adverse effects of these agents have received less attention.

The adverse effect profile of psilocybin in adults appears promising but its powerful psychoactive effects necessitate cautious use.6 It has a very wide therapeutic index, and in a recent meta-analysis of psilocybin for depression, no serious adverse effects were reported in any of the 7 included studies.7 Common adverse effects in the context of clinical use include anxiety, dysphoria, confusion, and an increase in blood pressure and heart rate.6 Due to potential cardiac effects, psilocybin is contraindicated in individuals with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.8 In recreational/nonclinical use, reactions such as suicidality, violence, convulsions, panic attacks, paranoia, confusion, prolonged dissociation, and mania have been reported.9,10 Animal and human studies indicate the risk of abuse and physical dependence is low. Major national surveys indicate low rates of abuse, treatment-seeking, and harm.11 In a recent 6-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) of psilocybin vs escitalopram for depression,12 no serious adverse events were reported. Adverse events reported in the psilocybin group in this trial are listed in Table 2.12

A recent phase 2 double-blind trial of single-dose psilocybin (1 mg, 10 mg, and 25 mg) for treatment-resistant depression (N = 233) sheds more light on the risk of adverse effects.13 The percentage of individuals experiencing adverse effects on Day 1 of administration was high: 61% in the 25 mg psilocybin group. Headache, nausea, fatigue, and dizziness were the most common effects. The incidence of any adverse event in the 25 mg group was 56% from Day 2 to Week 3, and 29% from Week 3 to Week 12. Suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or self-injury occurred in all 3 dose groups. Overall, 14% in the 25 mg group, 17% in the 10 mg group, and 9% in the 1 mg group showed worsening of suicidality from baseline to Week 3. Suicidal behavior was reported by 3 individuals in the 25 mg group after Week 3. The new-onset or worsening of preexisting suicidality with psilocybin reported in this study requires further investigation.

Lysergic acid diethylamide

LSD is similar to psilocybin in its agonistic action at the 5-HT2A brain receptors.4 It is typically administered as a single 100 to 200 μg dose and is used in conjunction with preintegration and postintegration psychotherapy.14 Its acute effects last approximately 12 hours.15

Continue to: Like psilocybin...

Like psilocybin, LSD has a wide therapeutic index. Commonly reported adverse effects of LSD are increased anxiety, dysphoria, and confusion. LSD can also lead to physiological adverse effects, such as increased blood pressure and heart rate, and thus is contraindicated in patients with severe heart disease.6 In a systematic review of the therapeutic use of LSD that included 567 participants,16 2 cases of serious adverse events were reported: a tonic-clonic seizure in a patient with a prior history of seizures, and a case of prolonged psychosis in a 21-year-old with a history of psychotic disorder.

Though few psychedelic studies have examined the adverse effects of these agents in older adults, a recent phase 1 study that recruited 48 healthy older adults (age 55 to 75) found that, compared to placebo, low doses (5 to 20 μg) of LSD 2 times a week for 3 weeks had similar adverse effects, cognitive impairment, or balance impairment.17 The only adverse effect noted to be different between the placebo group and active treatment groups was headache (50% for LSD 10 μg, 25% for LSD 20 μg, and 8% for placebo). Because the dose range (5 to 20 μg) used in this study was substantially lower than the typical therapeutic dose range of 100 to 200 μg, these results should not be interpreted as supporting the safety of LSD at higher doses in older adults.

DMT/ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is a plant-based psychedelic that contains an admixture of substances, including DMT, which acts as a 5-HT2A receptor agonist. In addition to DMT, ayahuasca also contains the alkaloid harmaline, which acts as a monoamine inhibitor. Use of ayahuasca can therefore pose a particular risk for individuals taking other serotonergic or noradrenergic medications or substances. The acute effects of DMT last approximately 4 hours,18 and acute administration of ayahuasca leads to a transient modified state of consciousness that is characterized by introspection, visions, enhanced emotions, and recall of personal memories.19 Research shows ayahuasca has been dosed at approximately 0.36 mg/kg of DMT for 1 dosing session alongside 6 2-hour therapy sessions.20

A recent review by Orsolini et al21 consolidated 40 preclinical, observational, and experimental studies of ayahuasca, and this compound appeared to be safe and well-tolerated; the most common adverse effects were transient emesis and nausea. In an RCT by Palhano-Fontes et al,20 nausea was observed in 71% of participants in the ayahuasca group (vs 26% placebo), vomiting in 57% of participants (vs 0% placebo), and restlessness in 50% of participants (vs 20% placebo). The authors noted that for some participants the ayahuasca session “was not necessarily a pleasant experience,” and was accompanied by psychological distress.20 Vomiting is traditionally viewed as an expected part of the purging process of ayahuasca religious ceremonies. Another review found that there appears to be good long-term tolerability of ayahuasca consumption among individuals who use this compound in religious ceremonies.22

MDMA

Entactogens (or empathogens) are a class of psychoactive substances that produce experiences of emotional openness and connection. MDMA is an entactogen known to release serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine by inhibiting reuptake.23 This process leads to the stimulation of neurohormonal signaling of oxytocin, cortisol, and other signaling molecules such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor.24 Memory reconsolidation and fear extinction may also play a therapeutic role, enabled by reduced activity in the amygdala and insula, and increased connectivity between the amygdala and hippocampus.24 MDMA has been reported to enhance feelings of well-being and increase prosocial behavior.25 In the therapeutic setting, MDMA has been generally dosed at 75 to 125 mg in 2 to 3 sessions alongside 10 therapy sessions. Administration of MDMA gives the user a subjective experience of energy and distortions in time and perception.26 These acute effects last approximately 2 to 4 hours.27

Continue to: A meta-analysis...

A meta-analysis of 5 RCTs of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD in adults demonstrated that MDMA was well-tolerated, and few serious adverse events were reported.28 Two trials from 2018 that were included in this meta-analysis—Mithoefer et al29 and Ot’alora et al30—illustrate the incidence of specific adverse effects. In a randomized, double-blind trial of 26 veterans and first responders with chronic PTSD, Mithoefer et al29 found the most commonly reported reactions during experimental sessions with MDMA were anxiety (81%), headache (69%), fatigue (62%), muscle tension (62%), and jaw clenching or tight jaw (50%). The most commonly reported reactions during 7 days of contact were fatigue (88%), anxiety (73%), insomnia (69%), headache (46%), muscle tension (46%), and increased irritability (46%). One instance of suicidal ideation was severe enough to require psychiatric hospitalization (this was the only instance of suicidal ideation among the 106 patients in the meta-analysis by Bahji et al28); the patient subsequently completed the trial. Transient elevation in pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature were noted during sessions that did not require medical intervention.29 Ot’alora et al30 found similar common adverse reactions: anxiety, dizziness, fatigue, headache, jaw clenching, muscle tension, and irritability. There were no serious adverse effects.

While the use of MDMA in controlled interventional settings has resulted in relatively few adverse events, robust literature describes the risks associated with the nonclinical/recreational use of MDMA. In cases of MDMA toxicity, death has been reported.31 Acutely, MDMA may lead to sympathomimetic effects, including serotonin syndrome.31 Longer-term studies of MDMA users have found chronic recreational use to be associated with worse sleep, poor mood, anxiety disturbances, memory deficits, and attention problems.32 MDMA has also been found to have moderate potential for abuse.33

Ketamine/esketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic with some hallucinogenic effects. It is an N-methyl-

Esketamine, the S(+)-enantiomer of ketamine, is also an NDMA antagonist. It has been developed as an intranasal formulation, typically dosed between 56 and 84 mg 2 times a week for 1 month, once a week for the following month, and once every 1 to 2 weeks thereafter.35 In most ketamine and esketamine trials, these compounds have been used without psychotherapy, although some interventions have integrated psychotherapy with ketamine treatment.36

Bennett et al37 elaborated on 3 paradigms for ketamine treatment: biochemical, psychotherapeutic, and psychedelic. The biochemical model examines the neurobiological effects of the medication. The psychotherapeutic model views ketamine as a way of assisting the psychotherapy process. The psychedelic model utilizes ketamine’s dissociative and psychedelic properties to induce an altered state of consciousness for therapeutic purposes and psychospiritual exploration.

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of the common adverse effects associated with ketamine use in clinical trials for depression reported dissociation, sedation, perceptual disturbances, anxiety, agitation, euphoria, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, and dizziness.38 Adverse effects experienced with esketamine in clinical trials include dissociation, dizziness, sedation, hypertension, hypoesthesia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and euphoric mood (Table 339). A recent systemic review found both ketamine and esketamine demonstrated higher adverse events than control conditions. IV ketamine also demonstrated lower dropouts and adverse events when compared to intranasal esketamine.40

Nonclinical/recreational use of ketamine is notable for urinary toxicity; 20% to 30% of frequent users of ketamine experience urinary problems that can range from ketamine-induced cystitis to hydronephrosis and kidney failure.41 Liver toxicity has also been reported with chronic use of high-dose ketamine. Ketamine is liable to abuse, dependence, and tolerance. There is evidence that nonclinical use of ketamine may lead to morbidity; impairment of memory, cognition, and attention; and urinary, gastric, and hepatic pathology.42

The FDA prescribing information for esketamine lists aneurysmal vascular disease, arteriovenous malformation, and intracerebral hemorrhage as contraindications.39 Patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions and risk factors may be at increased risk of adverse effects due to an increase in blood pressure. Esketamine can impair attention, judgment, thinking, reaction speed, and motor skills. Other adverse effects of esketamine noted in the prescribing information include dissociation, dizziness, nausea, sedation, vertigo, hypoesthesia, anxiety, lethargy, vomiting, feeling drunk, and euphoric mood.39A study of postmarketing safety concerns with esketamine using reports submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) revealed signals for suicidal ideation (reporting odds ratio [ROR] 24.03; 95% CI, 18.72 to 30.84), and completed suicide (ROR 5.75; 95% CI, 3.18 to 10.41).43 The signals for suicidal and self-injurious ideation remained significant when compared to venlafaxine in the FAERS database, while suicide attempts and fatal suicide attempts were no longer significant.43 Concerns regarding acute ketamine withdrawal have also been described in case reports.44

Other safety considerations of psychedelics

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is a rare condition associated with hallucinogen use. It is characterized by the recurrence of perceptual disturbances that an individual experienced while using hallucinogenic substances that creates significant distress or impairment.45 Because HPPD is a rare disorder, the exact prevalence is not well characterized, but DSM-5 suggests it is approximately 4.2%.46 HPPD is associated with numerous psychoactive substances, including psilocybin, ayahuasca, MDMA, and ketamine, but is most associated with LSD.45 HPPD is more likely to arise in individuals with histories of psychiatric illness or substance use disorders.47

Serotonin toxicity and other serotonergic interactions

Serotonin toxicity is a risk of serotonergic psychedelics, particularly when such agents are used in combination with serotonergic psychotropic medications. The most severe manifestation of serotonin toxicity is serotonin syndrome, which manifests as a life-threatening condition characterized by myoclonus, rigidity, agitation, delirium, and unstable cardiovascular functioning. Many psychedelic compounds have transient serotonin-related adverse effects, but serotonin toxicity due to psychedelic use is rare.48 Due to their mechanism of action, classical psychedelics are relatively safe in combination with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. MDMA is a serotonin-releasing agent that has a higher risk of serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crisis when used in combination with MAOIs.48

Boundary violations in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy

A key task facing psychedelic research is to establish parameters for the safe and ethical use of these agents. This is particularly relevant given the hype that surrounds the psychedelic resurgence and what we know about the controversial history of these substances. Anderson et al49 argued that “psychedelics can have lingering effects that include increased suggestibility and affective instability, as well as altered ego structure, social behaviour, and philosophical worldview. Stated simply, psychedelics can induce a vulnerable state both during and after treatment sessions.”

Continue to: Psychedelic treatment...

Psychedelic treatments such as psilocybin and MDMA are typically offered within the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and some researchers have raised concerns regarding boundary violations,50 given the patients’ particularly vulnerable states. In addition to concerns about sexual harassment, the financial exploitation of older adults is also a possible risk.51

Caveats to consider

Novel psychedelics therapies have demonstrated promising preliminary results for a broad range of psychiatric indications, including depression, end-of-life distress, substance use disorders, PTSD, and improving well-being. To date, psychedelics are generally well-tolerated in adults in clinical trials.

However, when it comes to adverse effects, there are challenges in regards to interpreting the psychedelic state.52 Some consider any unpleasant or unsettling psychedelic experience as an adverse reaction, while others consider it part of the therapeutic process. This is exemplified by the case of vomiting during ayahuasca ceremonies, which is generally considered part of the ritual. In such instances, it is essential to obtain informed consent and ensure participants are aware of these aspects of the experience. Compared to substances such as alcohol, opioids, and cocaine, psychedelics are remarkably safe from a physiological perspective, especially with regards to the risks of toxicity, mortality, and dependence.53 Their psychological safety is less established, and more caution and research is needed. The high incidence of adverse effects and suicidality noted in the recent phase 2 trial of psilocybin in treatment resistant depression are a reminder of this.13

There is uncertainty regarding the magnitude of risk in real-world clinical practice, particularly regarding addiction, suicidality, and precipitation or worsening of psychotic disorders. For example, note the extensive exclusion criteria used in the psilocybin vs escitalopram RCT by Carhart-Harris et al12: currently or previously diagnosed psychotic disorder, immediate family member with a diagnosed psychotic disorder, significant medical comorbidity (eg, diabetes, epilepsy, severe cardiovascular disease, hepatic or renal failure), history of suicide attempts requiring hospitalization, history of mania, pregnancy, and abnormal QT interval prolongation, among others. It would be prudent to keep these contraindications in mind regarding the clinical use of psychedelics in the future. This is particularly important in older adults because such patients often have substantial medical comorbidities and are at greater risk for adverse effects. For ketamine, research has implicated the role of mu opioid agonism in mediating ketamine’s antidepressant effects.54 This raises concerns about abuse, dependence, and addiction, especially with long-term use. There are also concerns regarding protracted withdrawal symptoms and associated suicidality.55

The therapeutic use of psychedelics is an exciting and promising avenue, with ongoing research and a rapidly evolving literature. An attitude of cautious optimism is warranted, but efficacy and safety should be demonstrated in well-designed and rigorous trials with adequate long-term follow-up before routine clinical use is recommended.

Bottom Line

In clinical trials for psychiatric disorders, psychedelics have been associated with a range of cognitive, psychiatric, and psychoactive adverse effects but generally have been well-tolerated, with a low incidence of serious adverse effects.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. Position Statement on the Use of Psychedelic and Empathogenic Agents for Mental Health Conditions. Updated July 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/d5c13619-ca1f-491f-a7a8-b7141c800904/Position-Use-of-Psychedelic-Empathogenic-Agents.pdf

- Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research. https://hopkinspsychedelic.org/

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). https://maps.org/

Drug Brand Names

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Psychedelics are a class of substances known to produce alterations in consciousness and perception. In the last 2 decades, psychedelic research has garnered increasing attention from scientists, therapists, entrepreneurs, and the public. While many of these compounds remain illegal in the United States and in many parts of the world (Box1), a recent resurrection of psychedelic research has motivated the FDA to designate multiple psychedelic compounds as “breakthrough therapies,” thereby expediting the investigation, development, and review of psychedelic treatments.

Box

The legal landscape of psychedelics is rapidly evolving. Psilocybin use has been decriminalized in many cities in the United States (such as Denver), and some states (such as Oregon) have legalized it for therapeutic use.

It is important to understand the difference between decriminalization and legalization. Decriminalization means the substance is still prohibited under existing laws, but the legal system will choose not to enforce the prohibition. Legalization is the rescinding of laws prohibiting the use of the substance. In the United States, these laws may be state or federal. Despite psilocybin legalization for therapeutic use in Oregon and decriminalization in various cities, psychedelics currently remain illegal under federal law.

Source: Reference 1

There is growing evidence that psychedelics may be efficacious for treating a range of psychiatric disorders. Potential clinical indications for psychedelics include some forms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders (Table 12,3). In most instances, the clinical use of psychedelics is being investigated and offered in the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, though ketamine is a prominent exception. Ketamine and esketamine are already being used to treat depression, and FDA approval is anticipated for other psychedelics.

This article examines the adverse effect profile of classical (psilocybin [“mushrooms”], lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]/ayahuasca) and nonclassical (the entactogen 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA, known as “ecstasy”] and the dissociative anesthetic ketamine) psychedelics.

Psilocybin

Psilocybin is typically administered as a single dose of 10 to 30 mg and used in conjunction with preintegration and postintegration psychotherapy. Administration of psilocybin typically produces perceptual distortions and mind-altering effects, which are mediated through 5-HT2A brain receptor agonistic action.4 The acute effects last approximately 6 hours.5 While psilocybin has generated promising results in early clinical trials,3 the adverse effects of these agents have received less attention.

The adverse effect profile of psilocybin in adults appears promising but its powerful psychoactive effects necessitate cautious use.6 It has a very wide therapeutic index, and in a recent meta-analysis of psilocybin for depression, no serious adverse effects were reported in any of the 7 included studies.7 Common adverse effects in the context of clinical use include anxiety, dysphoria, confusion, and an increase in blood pressure and heart rate.6 Due to potential cardiac effects, psilocybin is contraindicated in individuals with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.8 In recreational/nonclinical use, reactions such as suicidality, violence, convulsions, panic attacks, paranoia, confusion, prolonged dissociation, and mania have been reported.9,10 Animal and human studies indicate the risk of abuse and physical dependence is low. Major national surveys indicate low rates of abuse, treatment-seeking, and harm.11 In a recent 6-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) of psilocybin vs escitalopram for depression,12 no serious adverse events were reported. Adverse events reported in the psilocybin group in this trial are listed in Table 2.12

A recent phase 2 double-blind trial of single-dose psilocybin (1 mg, 10 mg, and 25 mg) for treatment-resistant depression (N = 233) sheds more light on the risk of adverse effects.13 The percentage of individuals experiencing adverse effects on Day 1 of administration was high: 61% in the 25 mg psilocybin group. Headache, nausea, fatigue, and dizziness were the most common effects. The incidence of any adverse event in the 25 mg group was 56% from Day 2 to Week 3, and 29% from Week 3 to Week 12. Suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or self-injury occurred in all 3 dose groups. Overall, 14% in the 25 mg group, 17% in the 10 mg group, and 9% in the 1 mg group showed worsening of suicidality from baseline to Week 3. Suicidal behavior was reported by 3 individuals in the 25 mg group after Week 3. The new-onset or worsening of preexisting suicidality with psilocybin reported in this study requires further investigation.

Lysergic acid diethylamide

LSD is similar to psilocybin in its agonistic action at the 5-HT2A brain receptors.4 It is typically administered as a single 100 to 200 μg dose and is used in conjunction with preintegration and postintegration psychotherapy.14 Its acute effects last approximately 12 hours.15

Continue to: Like psilocybin...

Like psilocybin, LSD has a wide therapeutic index. Commonly reported adverse effects of LSD are increased anxiety, dysphoria, and confusion. LSD can also lead to physiological adverse effects, such as increased blood pressure and heart rate, and thus is contraindicated in patients with severe heart disease.6 In a systematic review of the therapeutic use of LSD that included 567 participants,16 2 cases of serious adverse events were reported: a tonic-clonic seizure in a patient with a prior history of seizures, and a case of prolonged psychosis in a 21-year-old with a history of psychotic disorder.

Though few psychedelic studies have examined the adverse effects of these agents in older adults, a recent phase 1 study that recruited 48 healthy older adults (age 55 to 75) found that, compared to placebo, low doses (5 to 20 μg) of LSD 2 times a week for 3 weeks had similar adverse effects, cognitive impairment, or balance impairment.17 The only adverse effect noted to be different between the placebo group and active treatment groups was headache (50% for LSD 10 μg, 25% for LSD 20 μg, and 8% for placebo). Because the dose range (5 to 20 μg) used in this study was substantially lower than the typical therapeutic dose range of 100 to 200 μg, these results should not be interpreted as supporting the safety of LSD at higher doses in older adults.

DMT/ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is a plant-based psychedelic that contains an admixture of substances, including DMT, which acts as a 5-HT2A receptor agonist. In addition to DMT, ayahuasca also contains the alkaloid harmaline, which acts as a monoamine inhibitor. Use of ayahuasca can therefore pose a particular risk for individuals taking other serotonergic or noradrenergic medications or substances. The acute effects of DMT last approximately 4 hours,18 and acute administration of ayahuasca leads to a transient modified state of consciousness that is characterized by introspection, visions, enhanced emotions, and recall of personal memories.19 Research shows ayahuasca has been dosed at approximately 0.36 mg/kg of DMT for 1 dosing session alongside 6 2-hour therapy sessions.20

A recent review by Orsolini et al21 consolidated 40 preclinical, observational, and experimental studies of ayahuasca, and this compound appeared to be safe and well-tolerated; the most common adverse effects were transient emesis and nausea. In an RCT by Palhano-Fontes et al,20 nausea was observed in 71% of participants in the ayahuasca group (vs 26% placebo), vomiting in 57% of participants (vs 0% placebo), and restlessness in 50% of participants (vs 20% placebo). The authors noted that for some participants the ayahuasca session “was not necessarily a pleasant experience,” and was accompanied by psychological distress.20 Vomiting is traditionally viewed as an expected part of the purging process of ayahuasca religious ceremonies. Another review found that there appears to be good long-term tolerability of ayahuasca consumption among individuals who use this compound in religious ceremonies.22

MDMA

Entactogens (or empathogens) are a class of psychoactive substances that produce experiences of emotional openness and connection. MDMA is an entactogen known to release serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine by inhibiting reuptake.23 This process leads to the stimulation of neurohormonal signaling of oxytocin, cortisol, and other signaling molecules such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor.24 Memory reconsolidation and fear extinction may also play a therapeutic role, enabled by reduced activity in the amygdala and insula, and increased connectivity between the amygdala and hippocampus.24 MDMA has been reported to enhance feelings of well-being and increase prosocial behavior.25 In the therapeutic setting, MDMA has been generally dosed at 75 to 125 mg in 2 to 3 sessions alongside 10 therapy sessions. Administration of MDMA gives the user a subjective experience of energy and distortions in time and perception.26 These acute effects last approximately 2 to 4 hours.27

Continue to: A meta-analysis...

A meta-analysis of 5 RCTs of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD in adults demonstrated that MDMA was well-tolerated, and few serious adverse events were reported.28 Two trials from 2018 that were included in this meta-analysis—Mithoefer et al29 and Ot’alora et al30—illustrate the incidence of specific adverse effects. In a randomized, double-blind trial of 26 veterans and first responders with chronic PTSD, Mithoefer et al29 found the most commonly reported reactions during experimental sessions with MDMA were anxiety (81%), headache (69%), fatigue (62%), muscle tension (62%), and jaw clenching or tight jaw (50%). The most commonly reported reactions during 7 days of contact were fatigue (88%), anxiety (73%), insomnia (69%), headache (46%), muscle tension (46%), and increased irritability (46%). One instance of suicidal ideation was severe enough to require psychiatric hospitalization (this was the only instance of suicidal ideation among the 106 patients in the meta-analysis by Bahji et al28); the patient subsequently completed the trial. Transient elevation in pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature were noted during sessions that did not require medical intervention.29 Ot’alora et al30 found similar common adverse reactions: anxiety, dizziness, fatigue, headache, jaw clenching, muscle tension, and irritability. There were no serious adverse effects.

While the use of MDMA in controlled interventional settings has resulted in relatively few adverse events, robust literature describes the risks associated with the nonclinical/recreational use of MDMA. In cases of MDMA toxicity, death has been reported.31 Acutely, MDMA may lead to sympathomimetic effects, including serotonin syndrome.31 Longer-term studies of MDMA users have found chronic recreational use to be associated with worse sleep, poor mood, anxiety disturbances, memory deficits, and attention problems.32 MDMA has also been found to have moderate potential for abuse.33

Ketamine/esketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic with some hallucinogenic effects. It is an N-methyl-

Esketamine, the S(+)-enantiomer of ketamine, is also an NDMA antagonist. It has been developed as an intranasal formulation, typically dosed between 56 and 84 mg 2 times a week for 1 month, once a week for the following month, and once every 1 to 2 weeks thereafter.35 In most ketamine and esketamine trials, these compounds have been used without psychotherapy, although some interventions have integrated psychotherapy with ketamine treatment.36

Bennett et al37 elaborated on 3 paradigms for ketamine treatment: biochemical, psychotherapeutic, and psychedelic. The biochemical model examines the neurobiological effects of the medication. The psychotherapeutic model views ketamine as a way of assisting the psychotherapy process. The psychedelic model utilizes ketamine’s dissociative and psychedelic properties to induce an altered state of consciousness for therapeutic purposes and psychospiritual exploration.

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of the common adverse effects associated with ketamine use in clinical trials for depression reported dissociation, sedation, perceptual disturbances, anxiety, agitation, euphoria, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, and dizziness.38 Adverse effects experienced with esketamine in clinical trials include dissociation, dizziness, sedation, hypertension, hypoesthesia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and euphoric mood (Table 339). A recent systemic review found both ketamine and esketamine demonstrated higher adverse events than control conditions. IV ketamine also demonstrated lower dropouts and adverse events when compared to intranasal esketamine.40

Nonclinical/recreational use of ketamine is notable for urinary toxicity; 20% to 30% of frequent users of ketamine experience urinary problems that can range from ketamine-induced cystitis to hydronephrosis and kidney failure.41 Liver toxicity has also been reported with chronic use of high-dose ketamine. Ketamine is liable to abuse, dependence, and tolerance. There is evidence that nonclinical use of ketamine may lead to morbidity; impairment of memory, cognition, and attention; and urinary, gastric, and hepatic pathology.42

The FDA prescribing information for esketamine lists aneurysmal vascular disease, arteriovenous malformation, and intracerebral hemorrhage as contraindications.39 Patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions and risk factors may be at increased risk of adverse effects due to an increase in blood pressure. Esketamine can impair attention, judgment, thinking, reaction speed, and motor skills. Other adverse effects of esketamine noted in the prescribing information include dissociation, dizziness, nausea, sedation, vertigo, hypoesthesia, anxiety, lethargy, vomiting, feeling drunk, and euphoric mood.39A study of postmarketing safety concerns with esketamine using reports submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) revealed signals for suicidal ideation (reporting odds ratio [ROR] 24.03; 95% CI, 18.72 to 30.84), and completed suicide (ROR 5.75; 95% CI, 3.18 to 10.41).43 The signals for suicidal and self-injurious ideation remained significant when compared to venlafaxine in the FAERS database, while suicide attempts and fatal suicide attempts were no longer significant.43 Concerns regarding acute ketamine withdrawal have also been described in case reports.44

Other safety considerations of psychedelics

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is a rare condition associated with hallucinogen use. It is characterized by the recurrence of perceptual disturbances that an individual experienced while using hallucinogenic substances that creates significant distress or impairment.45 Because HPPD is a rare disorder, the exact prevalence is not well characterized, but DSM-5 suggests it is approximately 4.2%.46 HPPD is associated with numerous psychoactive substances, including psilocybin, ayahuasca, MDMA, and ketamine, but is most associated with LSD.45 HPPD is more likely to arise in individuals with histories of psychiatric illness or substance use disorders.47

Serotonin toxicity and other serotonergic interactions

Serotonin toxicity is a risk of serotonergic psychedelics, particularly when such agents are used in combination with serotonergic psychotropic medications. The most severe manifestation of serotonin toxicity is serotonin syndrome, which manifests as a life-threatening condition characterized by myoclonus, rigidity, agitation, delirium, and unstable cardiovascular functioning. Many psychedelic compounds have transient serotonin-related adverse effects, but serotonin toxicity due to psychedelic use is rare.48 Due to their mechanism of action, classical psychedelics are relatively safe in combination with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. MDMA is a serotonin-releasing agent that has a higher risk of serotonin syndrome or hypertensive crisis when used in combination with MAOIs.48

Boundary violations in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy

A key task facing psychedelic research is to establish parameters for the safe and ethical use of these agents. This is particularly relevant given the hype that surrounds the psychedelic resurgence and what we know about the controversial history of these substances. Anderson et al49 argued that “psychedelics can have lingering effects that include increased suggestibility and affective instability, as well as altered ego structure, social behaviour, and philosophical worldview. Stated simply, psychedelics can induce a vulnerable state both during and after treatment sessions.”

Continue to: Psychedelic treatment...

Psychedelic treatments such as psilocybin and MDMA are typically offered within the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and some researchers have raised concerns regarding boundary violations,50 given the patients’ particularly vulnerable states. In addition to concerns about sexual harassment, the financial exploitation of older adults is also a possible risk.51

Caveats to consider

Novel psychedelics therapies have demonstrated promising preliminary results for a broad range of psychiatric indications, including depression, end-of-life distress, substance use disorders, PTSD, and improving well-being. To date, psychedelics are generally well-tolerated in adults in clinical trials.

However, when it comes to adverse effects, there are challenges in regards to interpreting the psychedelic state.52 Some consider any unpleasant or unsettling psychedelic experience as an adverse reaction, while others consider it part of the therapeutic process. This is exemplified by the case of vomiting during ayahuasca ceremonies, which is generally considered part of the ritual. In such instances, it is essential to obtain informed consent and ensure participants are aware of these aspects of the experience. Compared to substances such as alcohol, opioids, and cocaine, psychedelics are remarkably safe from a physiological perspective, especially with regards to the risks of toxicity, mortality, and dependence.53 Their psychological safety is less established, and more caution and research is needed. The high incidence of adverse effects and suicidality noted in the recent phase 2 trial of psilocybin in treatment resistant depression are a reminder of this.13

There is uncertainty regarding the magnitude of risk in real-world clinical practice, particularly regarding addiction, suicidality, and precipitation or worsening of psychotic disorders. For example, note the extensive exclusion criteria used in the psilocybin vs escitalopram RCT by Carhart-Harris et al12: currently or previously diagnosed psychotic disorder, immediate family member with a diagnosed psychotic disorder, significant medical comorbidity (eg, diabetes, epilepsy, severe cardiovascular disease, hepatic or renal failure), history of suicide attempts requiring hospitalization, history of mania, pregnancy, and abnormal QT interval prolongation, among others. It would be prudent to keep these contraindications in mind regarding the clinical use of psychedelics in the future. This is particularly important in older adults because such patients often have substantial medical comorbidities and are at greater risk for adverse effects. For ketamine, research has implicated the role of mu opioid agonism in mediating ketamine’s antidepressant effects.54 This raises concerns about abuse, dependence, and addiction, especially with long-term use. There are also concerns regarding protracted withdrawal symptoms and associated suicidality.55

The therapeutic use of psychedelics is an exciting and promising avenue, with ongoing research and a rapidly evolving literature. An attitude of cautious optimism is warranted, but efficacy and safety should be demonstrated in well-designed and rigorous trials with adequate long-term follow-up before routine clinical use is recommended.

Bottom Line

In clinical trials for psychiatric disorders, psychedelics have been associated with a range of cognitive, psychiatric, and psychoactive adverse effects but generally have been well-tolerated, with a low incidence of serious adverse effects.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. Position Statement on the Use of Psychedelic and Empathogenic Agents for Mental Health Conditions. Updated July 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/d5c13619-ca1f-491f-a7a8-b7141c800904/Position-Use-of-Psychedelic-Empathogenic-Agents.pdf

- Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research. https://hopkinspsychedelic.org/

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). https://maps.org/

Drug Brand Names

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. The current legal status of psychedelics in the United States. Investing News Network. August 23, 2022. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://investingnews.com/legal-status-of-psychedelics-in-the-united-states/

2. Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, et al. Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(5):391-410.

3. Nutt D, Carhart-Harris R. The current status of psychedelics in psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(2):121-122.

4. Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(2):264-355.

5. Hasler F, Grimberg U, Benz MA et al. Acute psychological and physiological effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-effect study. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172:145-156.

6. Johnson MW, Hendricks PS, Barrett FS, et al. Classic psychedelics: an integrative review of epidemiology, therapeutics, mystical experience, and brain network function. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;197:83-102.

7. Li NX, Hu YR, Chen WN, et al. Dose effect of psilocybin on primary and secondary depression: a preliminary systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:26-34.

8. Johnson MW, Richards WA, Griffiths RR. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):603-620.

9. Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ. User perceptions of the benefits and harms of hallucinogenic drug use: a web-based questionnaire study. J Subst Use. 2010;15(4):283-300.

10. van Amsterdam J, Opperhuizen A, van den Brink W. Harm potential of magic mushroom use: a review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;59(3):423-429.

11. Johnson MW, Griffiths RR, Hendricks PS, et al. The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:143-166.

12. Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl Med. 2021;384(15):1402-1411.

13. Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, et al. Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant Episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(18):1637-1648.

14. Galvão-Coelho NL, Marx W, Gonzalez M, et al. Classic serotonergic psychedelics for mood and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of mood disorder patients and healthy participants. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(2):341-354.

15. Schmid Y, Enzler F, Gasser P, et al. Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(8):544-553.

16. Fuentes JJ, Fonseca F, Elices M, et al. Therapeutic use of LSD in psychiatry: a systematic review of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:943.

17. Family N, Maillet EL, Williams LTJ, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of low dose lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in healthy older volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020;237(3):841-853.

18. Frecska E, Bokor P, Winkelman M. The therapeutic potentials of ayahuasca: possible effects against various diseases of civilization. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:35.

19. Domínguez-Clavé E, Solar J, Elices M, et al. Ayahuasca: pharmacology, neuroscience and therapeutic potential. Brain Res Bull. 2016;126(Pt 1):89-101.

20. Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(4):655-663.

21. Orsolini L, Chiappini S, Papanti D, et al. How does ayahuasca work from a psychiatric perspective? Pros and cons of the entheogenic therapy. Hum Psychopharmacol: Clin Exp. 2020;35(3):e2728.

22. Durante Í, Dos Santos RG, Bouso JC, et al. Risk assessment of ayahuasca use in a religious context: self-reported risk factors and adverse effects. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43(4):362-369.

23. Sessa B, Higbed L, Nutt D. A review of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:138.

24. Feduccia AA, Mithoefer MC. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD: are memory reconsolidation and fear extinction underlying mechanisms? Progress Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(Pt A):221-228.

25. Hysek CM, Schmid Y, Simmler LD, et al. MDMA enhances emotional empathy and prosocial behavior. Soc Cogn Affective Neurosc. 2014;9(11):1645-1652.

26. Kalant H. The pharmacology and toxicology of “ecstasy” (MDMA) and related drugs. CMAJ. 2001;165(7):917-928.

27. Dumont GJ, Verkes RJ. A review of acute effects of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(2):176-187.

28. Bahji A, Forsyth A, Groll D, et al. Efficacy of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96:109735.

29. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.