User login

Color Code Mohs Maps, Expert Advises

SAN DIEGO – Color coding reference marks on a specimen and a Mohs map preserves orientation, no matter what happens on the way to the microscope, according to Dr. Howard Steinman.

Reference marks, he explained, are small nicks made with a scalpel, sutures, or staples that serve as extensions of imaginary reference lines extending across the wound.

To distinguish them, he said he designates a 12 o’clock position at the top of the field, makes a double nick, and inks it blue, since that’s the color of the sky.

At the 6 o’clock position, he makes a single nick and marks it green, for the earth.

A third and fourth color can be designated for the 3 and 9 o’clock positions for further clarity, suggested Dr. Steinman, director of dermatologic and skin cancer surgery at Scott and White Healthcare in Temple, Tex.

Some surgeons mark the center yellow.

One day, when you least expect it, "your specimen will end up on the floor," he predicted. "This will happen to you ... [and you’ll say], thank God for the double nick."

With the ink as a guide, it will become clear to you, a technician, or a pathologist which way is up on the specimen, he said at the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

When using green ink, remember that it’s a vital dye and can stain counters and other surfaces, noted Dr. Steinman.

"Mark before excising the specimen, because the specimen is going to rotate and contract," he said.

Dr. Steinman said he also color codes important histologic features on the Mohs map, which functions as a pathology report, medical record, and medicolegal document.

"Mark the tumor in red and everything else in black," specifically labeling all nontumor findings such as dense inflammation, incomplete margins, scars, or unrelated tumors.

Dr. Edward Yob, a dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla., said he color codes his slides as well.

"If it’s the fourth stage, it’s going to be pink," he said. Consistency is key.

Dr. Steinman said the Mohs map, with its legend and color coding, will serve as an essential document for later reference.

"Without the human, without the slides, 15 or 16 years later I can tell you exactly what I did and why," he said.

Dr. Steinman and Dr. Yob said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Color coding reference marks on a specimen and a Mohs map preserves orientation, no matter what happens on the way to the microscope, according to Dr. Howard Steinman.

Reference marks, he explained, are small nicks made with a scalpel, sutures, or staples that serve as extensions of imaginary reference lines extending across the wound.

To distinguish them, he said he designates a 12 o’clock position at the top of the field, makes a double nick, and inks it blue, since that’s the color of the sky.

At the 6 o’clock position, he makes a single nick and marks it green, for the earth.

A third and fourth color can be designated for the 3 and 9 o’clock positions for further clarity, suggested Dr. Steinman, director of dermatologic and skin cancer surgery at Scott and White Healthcare in Temple, Tex.

Some surgeons mark the center yellow.

One day, when you least expect it, "your specimen will end up on the floor," he predicted. "This will happen to you ... [and you’ll say], thank God for the double nick."

With the ink as a guide, it will become clear to you, a technician, or a pathologist which way is up on the specimen, he said at the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

When using green ink, remember that it’s a vital dye and can stain counters and other surfaces, noted Dr. Steinman.

"Mark before excising the specimen, because the specimen is going to rotate and contract," he said.

Dr. Steinman said he also color codes important histologic features on the Mohs map, which functions as a pathology report, medical record, and medicolegal document.

"Mark the tumor in red and everything else in black," specifically labeling all nontumor findings such as dense inflammation, incomplete margins, scars, or unrelated tumors.

Dr. Edward Yob, a dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla., said he color codes his slides as well.

"If it’s the fourth stage, it’s going to be pink," he said. Consistency is key.

Dr. Steinman said the Mohs map, with its legend and color coding, will serve as an essential document for later reference.

"Without the human, without the slides, 15 or 16 years later I can tell you exactly what I did and why," he said.

Dr. Steinman and Dr. Yob said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Color coding reference marks on a specimen and a Mohs map preserves orientation, no matter what happens on the way to the microscope, according to Dr. Howard Steinman.

Reference marks, he explained, are small nicks made with a scalpel, sutures, or staples that serve as extensions of imaginary reference lines extending across the wound.

To distinguish them, he said he designates a 12 o’clock position at the top of the field, makes a double nick, and inks it blue, since that’s the color of the sky.

At the 6 o’clock position, he makes a single nick and marks it green, for the earth.

A third and fourth color can be designated for the 3 and 9 o’clock positions for further clarity, suggested Dr. Steinman, director of dermatologic and skin cancer surgery at Scott and White Healthcare in Temple, Tex.

Some surgeons mark the center yellow.

One day, when you least expect it, "your specimen will end up on the floor," he predicted. "This will happen to you ... [and you’ll say], thank God for the double nick."

With the ink as a guide, it will become clear to you, a technician, or a pathologist which way is up on the specimen, he said at the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

When using green ink, remember that it’s a vital dye and can stain counters and other surfaces, noted Dr. Steinman.

"Mark before excising the specimen, because the specimen is going to rotate and contract," he said.

Dr. Steinman said he also color codes important histologic features on the Mohs map, which functions as a pathology report, medical record, and medicolegal document.

"Mark the tumor in red and everything else in black," specifically labeling all nontumor findings such as dense inflammation, incomplete margins, scars, or unrelated tumors.

Dr. Edward Yob, a dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla., said he color codes his slides as well.

"If it’s the fourth stage, it’s going to be pink," he said. Consistency is key.

Dr. Steinman said the Mohs map, with its legend and color coding, will serve as an essential document for later reference.

"Without the human, without the slides, 15 or 16 years later I can tell you exactly what I did and why," he said.

Dr. Steinman and Dr. Yob said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Mohs Pros Offer Pearls From Their Practices

SAN DIEGO – Sewing supplies, tricks of the dental trade, and a nice firm handshake are handy, value-added elements of a smooth-running Mohs surgery practice, speakers said at the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

Many of the pearls offered during 3 days of clinical sessions are cheap, simple, and easy to employ, making life just a bit easier during complex Mohs surgical procedures or in a busy office setting.

Among the suggestions:

• Take a trip to the fabric store. A $10 sewing magnet, sterilized in your office, can grab a needle off a tray or the floor. Buttons can be used as bolsters to distribute tension on a wound, stabilize a graft, or form a scaffold for healing of the helical sulcus following repair, said Dr. Edward H. Yob, a dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla.

• Put a fine point on it. Tired of smudged labels on your slides? Order some extra fine permanent markers (offered by Pilot with the code SCA-UF), which can be used on glass, said Dr. Howard Steinman, director of dermatologic and skin cancer surgery at Scott and White HealthCare in Temple, Tex.

• Brush up on your inking technique. Dr. Steinman said he has become a recent convert to small, tissue-marking dye systems by Cancer Diagnostics. These kits come with dyes in seven colors, each with a small brush for precise distribution. The bottles "tend to wobble a little bit" in the case, so Dr. Steinman said he lines the base of the kit with double-sided tape to hold them steady. "They’re certainly more convenient than the wooden sticks," he said.

• Peruse a dental supply catalog. Dr. Yob apparently forgoes the Lands’ End catalog in favor of a veritable shopping spree through pages of products such as LolliCaine topical anesthetic gel (to numb intraoral tissue prior to a needle prick); dental rolls, 2,000 to a box (to shield sharp instruments, pack a nose, or serve as bolsters or pressure points under dressings); and dental syringes and needles.

• Invest in a thermal cautery device. If you’re in a region where you treat a fair number of elderly patients with implanted defibrillators, you’re likely to appreciate having an alternative to an electrocautery unit. "You really don’t want to set them off while you’re doing a procedure," said Dr. Yob.

• Grip and grin. Dr. Yob said he always shakes the hand of a patient following a biopsy or Mohs procedure, not only because it’s a good business practice, but also because he can check for clammy hands or a weak grip. "If that hand is clammy, I’m going to be concerned about that patient getting up quickly," he said.

• Pass the salts. If a patient feels weak, nauseous, or woozy, Dr. Yob, a nurse, or office assistant can grab ammonia salts taped to every paper towel dispenser in the office for a quick antidote.

• Put hair in its place. While Vaseline petroleum jelly is cheap and convenient, patients will appreciate it if you have on hand hair clips, bands, and Dippity-do hair gel, instead of glopping up their hair to clear a surgical field on the scalp, said Dr. Carlos Garcia, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City.

• Go one step cheaper than generic. If you love the flexibility and self-adherent qualities of 3M’s Coban wrap, you’ve probably discovered the less-expensive alternative, Co-Flex by Andover Healthcare. But perhaps you haven’t stopped by a feed store lately to discover Vetrap bandaging tape, also by 3M, which is far more affordable than the suspiciously similar human product, said Dr. Yob.

• Introduce yourself to the ENT resident’s friend. While working on a complex Mohs case on a patient’s neck, Dr. Steinman said he learned an important anatomy lesson from his third-year resident, who happens to be a board-certified otolaryngologist. The resident pointed out that Dr. Steinman was in safe territory as long as he stayed above the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, known in ENT circles as "the resident’s friend."

None of the speakers who offered clinical pearls reported having financial disclosures associated with the products they recommended.

SAN DIEGO – Sewing supplies, tricks of the dental trade, and a nice firm handshake are handy, value-added elements of a smooth-running Mohs surgery practice, speakers said at the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

Many of the pearls offered during 3 days of clinical sessions are cheap, simple, and easy to employ, making life just a bit easier during complex Mohs surgical procedures or in a busy office setting.

Among the suggestions:

• Take a trip to the fabric store. A $10 sewing magnet, sterilized in your office, can grab a needle off a tray or the floor. Buttons can be used as bolsters to distribute tension on a wound, stabilize a graft, or form a scaffold for healing of the helical sulcus following repair, said Dr. Edward H. Yob, a dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla.

• Put a fine point on it. Tired of smudged labels on your slides? Order some extra fine permanent markers (offered by Pilot with the code SCA-UF), which can be used on glass, said Dr. Howard Steinman, director of dermatologic and skin cancer surgery at Scott and White HealthCare in Temple, Tex.

• Brush up on your inking technique. Dr. Steinman said he has become a recent convert to small, tissue-marking dye systems by Cancer Diagnostics. These kits come with dyes in seven colors, each with a small brush for precise distribution. The bottles "tend to wobble a little bit" in the case, so Dr. Steinman said he lines the base of the kit with double-sided tape to hold them steady. "They’re certainly more convenient than the wooden sticks," he said.

• Peruse a dental supply catalog. Dr. Yob apparently forgoes the Lands’ End catalog in favor of a veritable shopping spree through pages of products such as LolliCaine topical anesthetic gel (to numb intraoral tissue prior to a needle prick); dental rolls, 2,000 to a box (to shield sharp instruments, pack a nose, or serve as bolsters or pressure points under dressings); and dental syringes and needles.

• Invest in a thermal cautery device. If you’re in a region where you treat a fair number of elderly patients with implanted defibrillators, you’re likely to appreciate having an alternative to an electrocautery unit. "You really don’t want to set them off while you’re doing a procedure," said Dr. Yob.

• Grip and grin. Dr. Yob said he always shakes the hand of a patient following a biopsy or Mohs procedure, not only because it’s a good business practice, but also because he can check for clammy hands or a weak grip. "If that hand is clammy, I’m going to be concerned about that patient getting up quickly," he said.

• Pass the salts. If a patient feels weak, nauseous, or woozy, Dr. Yob, a nurse, or office assistant can grab ammonia salts taped to every paper towel dispenser in the office for a quick antidote.

• Put hair in its place. While Vaseline petroleum jelly is cheap and convenient, patients will appreciate it if you have on hand hair clips, bands, and Dippity-do hair gel, instead of glopping up their hair to clear a surgical field on the scalp, said Dr. Carlos Garcia, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City.

• Go one step cheaper than generic. If you love the flexibility and self-adherent qualities of 3M’s Coban wrap, you’ve probably discovered the less-expensive alternative, Co-Flex by Andover Healthcare. But perhaps you haven’t stopped by a feed store lately to discover Vetrap bandaging tape, also by 3M, which is far more affordable than the suspiciously similar human product, said Dr. Yob.

• Introduce yourself to the ENT resident’s friend. While working on a complex Mohs case on a patient’s neck, Dr. Steinman said he learned an important anatomy lesson from his third-year resident, who happens to be a board-certified otolaryngologist. The resident pointed out that Dr. Steinman was in safe territory as long as he stayed above the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, known in ENT circles as "the resident’s friend."

None of the speakers who offered clinical pearls reported having financial disclosures associated with the products they recommended.

SAN DIEGO – Sewing supplies, tricks of the dental trade, and a nice firm handshake are handy, value-added elements of a smooth-running Mohs surgery practice, speakers said at the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

Many of the pearls offered during 3 days of clinical sessions are cheap, simple, and easy to employ, making life just a bit easier during complex Mohs surgical procedures or in a busy office setting.

Among the suggestions:

• Take a trip to the fabric store. A $10 sewing magnet, sterilized in your office, can grab a needle off a tray or the floor. Buttons can be used as bolsters to distribute tension on a wound, stabilize a graft, or form a scaffold for healing of the helical sulcus following repair, said Dr. Edward H. Yob, a dermatologic surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla.

• Put a fine point on it. Tired of smudged labels on your slides? Order some extra fine permanent markers (offered by Pilot with the code SCA-UF), which can be used on glass, said Dr. Howard Steinman, director of dermatologic and skin cancer surgery at Scott and White HealthCare in Temple, Tex.

• Brush up on your inking technique. Dr. Steinman said he has become a recent convert to small, tissue-marking dye systems by Cancer Diagnostics. These kits come with dyes in seven colors, each with a small brush for precise distribution. The bottles "tend to wobble a little bit" in the case, so Dr. Steinman said he lines the base of the kit with double-sided tape to hold them steady. "They’re certainly more convenient than the wooden sticks," he said.

• Peruse a dental supply catalog. Dr. Yob apparently forgoes the Lands’ End catalog in favor of a veritable shopping spree through pages of products such as LolliCaine topical anesthetic gel (to numb intraoral tissue prior to a needle prick); dental rolls, 2,000 to a box (to shield sharp instruments, pack a nose, or serve as bolsters or pressure points under dressings); and dental syringes and needles.

• Invest in a thermal cautery device. If you’re in a region where you treat a fair number of elderly patients with implanted defibrillators, you’re likely to appreciate having an alternative to an electrocautery unit. "You really don’t want to set them off while you’re doing a procedure," said Dr. Yob.

• Grip and grin. Dr. Yob said he always shakes the hand of a patient following a biopsy or Mohs procedure, not only because it’s a good business practice, but also because he can check for clammy hands or a weak grip. "If that hand is clammy, I’m going to be concerned about that patient getting up quickly," he said.

• Pass the salts. If a patient feels weak, nauseous, or woozy, Dr. Yob, a nurse, or office assistant can grab ammonia salts taped to every paper towel dispenser in the office for a quick antidote.

• Put hair in its place. While Vaseline petroleum jelly is cheap and convenient, patients will appreciate it if you have on hand hair clips, bands, and Dippity-do hair gel, instead of glopping up their hair to clear a surgical field on the scalp, said Dr. Carlos Garcia, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City.

• Go one step cheaper than generic. If you love the flexibility and self-adherent qualities of 3M’s Coban wrap, you’ve probably discovered the less-expensive alternative, Co-Flex by Andover Healthcare. But perhaps you haven’t stopped by a feed store lately to discover Vetrap bandaging tape, also by 3M, which is far more affordable than the suspiciously similar human product, said Dr. Yob.

• Introduce yourself to the ENT resident’s friend. While working on a complex Mohs case on a patient’s neck, Dr. Steinman said he learned an important anatomy lesson from his third-year resident, who happens to be a board-certified otolaryngologist. The resident pointed out that Dr. Steinman was in safe territory as long as he stayed above the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, known in ENT circles as "the resident’s friend."

None of the speakers who offered clinical pearls reported having financial disclosures associated with the products they recommended.

FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Hospital Setting May Pose Collegial Challenges in Mohs

SAN DIEGO – It would be somewhat of an understatement to say that Mohs surgery was not particularly welcomed at hospitals where Dr. Rainer Sachse used to practice.

As a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, he had hoped to utilize the technique to treat extensive, high-stage tumors in high-risk patients within a hospital setting, believing that the literature convincingly suggested that Mohs offered the best hope for cancer control in such patients.

Nurses, he recalled, considered Mohs a "slow, mutilating, expensive" procedure. Surgeons felt it was unnecessary. Pathologists thought their traditional methods "worked perfectly well."

Dermatologists seemed preoccupied by turf battles between the American Society for Mohs Surgery (ASMS) and the American College of Mohs Surgery. Dermatology residents had no time, and plastic surgery residents were uninterested, Dr. Sachse said at the meeting sponsored by the ASMS.

He pressed on, though, inspired by cases in which conventional excisions and standard therapy mutilated patients or led to their untimely deaths from tumors with continuous growth patterns.

He observed colleagues and sought out preceptorships, pored over the literature, and took a Mohs surgery course before beginning to try small cases with a pathologist who had received dermatopathology training. Finally, he began to change minds and take on more challenging cases.

Seeing the results, "a pathologist who was initially very skeptical eventually became a strong supporter," said Dr. Sachse, who is in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Hospital-based Mohs surgery has a role in the treatment of "psychologically problematic" patients, including those with severe anxiety and/or dementia; patients with high-risk medical conditions, including ischemic heart disease, severe arrhythmias, significant pulmonary insufficiencies, or coagulopathies; the physical handicapped; and the morbidly obese, he said.

Additionally, some hospitalized patients require urgent care, what Dr. Sachse terms "emergency Mohs surgery." He offered, as an example, a leukemia patient with skin necrosis of the scalp that was doubling in size every 24 hours. A biopsy revealed that the patient had a zygomycete fungal infection.

Mohs micrographic surgery was followed by topical and oral antifungal therapy and, after a delay, a skin graft, for a clinically and aesthetically acceptable result, he said.

With unusual and complex cases, it is important to build teamwork within the hospital since a multispecialty approach is necessary for cases that invade multiple structures of the head and neck, said Dr. Sachse.

In such cases, the concept of complete margin control must be emphasized, since many colleagues in otolaryngology, plastic surgery, and pathology will be unfamiliar with the basic tenets of the approach and the precision required to achieving those goals, he noted.

He learned to counter perceptions of Mohs surgery as tedious and slow by using careful planning and documentation of results in patients who might have been previously considered inoperable.

Education helps, as does realistic scheduling of operating rooms for the time required for extensive debridement, meticulous staging, excision, and repair.

Presenting Mohs cases to a hospital tumor board can be illuminating to the uninitiated, and the cases themselves are "very rewarding," he said.

Dr. Sachse cautioned that surgeons taking on highly complex cases should "be prepared to meet a patient you may not be able to cure." That said, "Mohs is a surgical tool which can and should be used for very extensive tumors. The complexity of the margins may increase exponentially, but you can always cut quicker than any tumor can grow."

Dr. Sachse said that he had no relevant disclosures.

plastic and reconstructive surgeon, high-stage tumors, high-risk patients, hospital setting, cancer control, Dermatologists, American Society for Mohs Surgery, ASMS, the American College of Mohs Surgery,

SAN DIEGO – It would be somewhat of an understatement to say that Mohs surgery was not particularly welcomed at hospitals where Dr. Rainer Sachse used to practice.

As a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, he had hoped to utilize the technique to treat extensive, high-stage tumors in high-risk patients within a hospital setting, believing that the literature convincingly suggested that Mohs offered the best hope for cancer control in such patients.

Nurses, he recalled, considered Mohs a "slow, mutilating, expensive" procedure. Surgeons felt it was unnecessary. Pathologists thought their traditional methods "worked perfectly well."

Dermatologists seemed preoccupied by turf battles between the American Society for Mohs Surgery (ASMS) and the American College of Mohs Surgery. Dermatology residents had no time, and plastic surgery residents were uninterested, Dr. Sachse said at the meeting sponsored by the ASMS.

He pressed on, though, inspired by cases in which conventional excisions and standard therapy mutilated patients or led to their untimely deaths from tumors with continuous growth patterns.

He observed colleagues and sought out preceptorships, pored over the literature, and took a Mohs surgery course before beginning to try small cases with a pathologist who had received dermatopathology training. Finally, he began to change minds and take on more challenging cases.

Seeing the results, "a pathologist who was initially very skeptical eventually became a strong supporter," said Dr. Sachse, who is in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Hospital-based Mohs surgery has a role in the treatment of "psychologically problematic" patients, including those with severe anxiety and/or dementia; patients with high-risk medical conditions, including ischemic heart disease, severe arrhythmias, significant pulmonary insufficiencies, or coagulopathies; the physical handicapped; and the morbidly obese, he said.

Additionally, some hospitalized patients require urgent care, what Dr. Sachse terms "emergency Mohs surgery." He offered, as an example, a leukemia patient with skin necrosis of the scalp that was doubling in size every 24 hours. A biopsy revealed that the patient had a zygomycete fungal infection.

Mohs micrographic surgery was followed by topical and oral antifungal therapy and, after a delay, a skin graft, for a clinically and aesthetically acceptable result, he said.

With unusual and complex cases, it is important to build teamwork within the hospital since a multispecialty approach is necessary for cases that invade multiple structures of the head and neck, said Dr. Sachse.

In such cases, the concept of complete margin control must be emphasized, since many colleagues in otolaryngology, plastic surgery, and pathology will be unfamiliar with the basic tenets of the approach and the precision required to achieving those goals, he noted.

He learned to counter perceptions of Mohs surgery as tedious and slow by using careful planning and documentation of results in patients who might have been previously considered inoperable.

Education helps, as does realistic scheduling of operating rooms for the time required for extensive debridement, meticulous staging, excision, and repair.

Presenting Mohs cases to a hospital tumor board can be illuminating to the uninitiated, and the cases themselves are "very rewarding," he said.

Dr. Sachse cautioned that surgeons taking on highly complex cases should "be prepared to meet a patient you may not be able to cure." That said, "Mohs is a surgical tool which can and should be used for very extensive tumors. The complexity of the margins may increase exponentially, but you can always cut quicker than any tumor can grow."

Dr. Sachse said that he had no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – It would be somewhat of an understatement to say that Mohs surgery was not particularly welcomed at hospitals where Dr. Rainer Sachse used to practice.

As a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, he had hoped to utilize the technique to treat extensive, high-stage tumors in high-risk patients within a hospital setting, believing that the literature convincingly suggested that Mohs offered the best hope for cancer control in such patients.

Nurses, he recalled, considered Mohs a "slow, mutilating, expensive" procedure. Surgeons felt it was unnecessary. Pathologists thought their traditional methods "worked perfectly well."

Dermatologists seemed preoccupied by turf battles between the American Society for Mohs Surgery (ASMS) and the American College of Mohs Surgery. Dermatology residents had no time, and plastic surgery residents were uninterested, Dr. Sachse said at the meeting sponsored by the ASMS.

He pressed on, though, inspired by cases in which conventional excisions and standard therapy mutilated patients or led to their untimely deaths from tumors with continuous growth patterns.

He observed colleagues and sought out preceptorships, pored over the literature, and took a Mohs surgery course before beginning to try small cases with a pathologist who had received dermatopathology training. Finally, he began to change minds and take on more challenging cases.

Seeing the results, "a pathologist who was initially very skeptical eventually became a strong supporter," said Dr. Sachse, who is in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Hospital-based Mohs surgery has a role in the treatment of "psychologically problematic" patients, including those with severe anxiety and/or dementia; patients with high-risk medical conditions, including ischemic heart disease, severe arrhythmias, significant pulmonary insufficiencies, or coagulopathies; the physical handicapped; and the morbidly obese, he said.

Additionally, some hospitalized patients require urgent care, what Dr. Sachse terms "emergency Mohs surgery." He offered, as an example, a leukemia patient with skin necrosis of the scalp that was doubling in size every 24 hours. A biopsy revealed that the patient had a zygomycete fungal infection.

Mohs micrographic surgery was followed by topical and oral antifungal therapy and, after a delay, a skin graft, for a clinically and aesthetically acceptable result, he said.

With unusual and complex cases, it is important to build teamwork within the hospital since a multispecialty approach is necessary for cases that invade multiple structures of the head and neck, said Dr. Sachse.

In such cases, the concept of complete margin control must be emphasized, since many colleagues in otolaryngology, plastic surgery, and pathology will be unfamiliar with the basic tenets of the approach and the precision required to achieving those goals, he noted.

He learned to counter perceptions of Mohs surgery as tedious and slow by using careful planning and documentation of results in patients who might have been previously considered inoperable.

Education helps, as does realistic scheduling of operating rooms for the time required for extensive debridement, meticulous staging, excision, and repair.

Presenting Mohs cases to a hospital tumor board can be illuminating to the uninitiated, and the cases themselves are "very rewarding," he said.

Dr. Sachse cautioned that surgeons taking on highly complex cases should "be prepared to meet a patient you may not be able to cure." That said, "Mohs is a surgical tool which can and should be used for very extensive tumors. The complexity of the margins may increase exponentially, but you can always cut quicker than any tumor can grow."

Dr. Sachse said that he had no relevant disclosures.

plastic and reconstructive surgeon, high-stage tumors, high-risk patients, hospital setting, cancer control, Dermatologists, American Society for Mohs Surgery, ASMS, the American College of Mohs Surgery,

plastic and reconstructive surgeon, high-stage tumors, high-risk patients, hospital setting, cancer control, Dermatologists, American Society for Mohs Surgery, ASMS, the American College of Mohs Surgery,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Lines Blur Between Dysplasia, Carcinoma in Situ

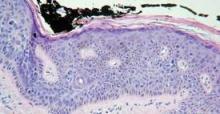

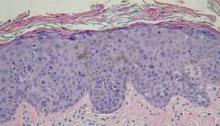

SAN DIEGO – It’s not getting any easier to make the histological distinction between carcinoma in situ and simple dysplasia in a sun-damaged epidermis, but it may be getting less critical to get it right, noted Dr. John B. Campbell.

During his presentation at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery, Dr. Campbell, a Mohs pathologist in private practice in San Diego, showed slides depicting disorderly cells that typify dysplasia extending high up into the epidermis along the edges of specimens containing in situ carcinoma. "There are a lot of things that go along with dysplastic changes," he said. "The nuclei become larger; they stain darker; they have less cytoplasm so that the N/C [nuclear to cytoplasmic] ratio increases."

"At some place along the edges of the specimen you’re going to have to draw a line between in situ carcinoma and simple dysplasia. There are gradations that are somewhat subjective."

Pathologists commonly envision a line midway through the epidermis. If the dark and disorganized cells reach that point, they call it "moderate dysplasia." If they’re clumped in the lower third of the epidermis, it merits a call of "mild dysplasia," and if they extend to near the surface, it’s "severe."

"Dysplastic changes that are wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom are carcinoma in situ," he said. "You’ll need to develop criteria on your own."

In the meantime, the pressure to make the right call may be easing.

"What I’ve seen happening in the last few years is that we’re becoming less and less sensitive about dysplasia at the edges of in situ carcinomas because we can treat them so easily topically," said Dr. Campbell. Beyond watchful waiting or freezing, such regions can now be well managed with topical therapies such as Aldara (imiquimod) or Efudex (fluorouracil).

"Once we’ve cleared the unequivocal carcinoma in situ, people are letting a significant amount of dysplasia remain and then treating it in follow-up.

"There’s really no downside to [conservative or topical management] as long as the patient is reliable," he said.

Taking a careful look at the site during follow-up visits will easily reveal any cell changes that might prompt a fresh biopsy. One finding of note in such cases is the proclivity of dysplastic cells to take a downward course along appendage structures such as eccrine ducts and follicles in the epithelium. "They can go down quite deep ... maybe 2 mm deep to the surface," he said.

In his practice, Dr. Campbell and his colleagues characterize such findings as "advanced actinic keratoses," and note the presence of dysplastic cells along appendage structures.

Dr. Campbell reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – It’s not getting any easier to make the histological distinction between carcinoma in situ and simple dysplasia in a sun-damaged epidermis, but it may be getting less critical to get it right, noted Dr. John B. Campbell.

During his presentation at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery, Dr. Campbell, a Mohs pathologist in private practice in San Diego, showed slides depicting disorderly cells that typify dysplasia extending high up into the epidermis along the edges of specimens containing in situ carcinoma. "There are a lot of things that go along with dysplastic changes," he said. "The nuclei become larger; they stain darker; they have less cytoplasm so that the N/C [nuclear to cytoplasmic] ratio increases."

"At some place along the edges of the specimen you’re going to have to draw a line between in situ carcinoma and simple dysplasia. There are gradations that are somewhat subjective."

Pathologists commonly envision a line midway through the epidermis. If the dark and disorganized cells reach that point, they call it "moderate dysplasia." If they’re clumped in the lower third of the epidermis, it merits a call of "mild dysplasia," and if they extend to near the surface, it’s "severe."

"Dysplastic changes that are wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom are carcinoma in situ," he said. "You’ll need to develop criteria on your own."

In the meantime, the pressure to make the right call may be easing.

"What I’ve seen happening in the last few years is that we’re becoming less and less sensitive about dysplasia at the edges of in situ carcinomas because we can treat them so easily topically," said Dr. Campbell. Beyond watchful waiting or freezing, such regions can now be well managed with topical therapies such as Aldara (imiquimod) or Efudex (fluorouracil).

"Once we’ve cleared the unequivocal carcinoma in situ, people are letting a significant amount of dysplasia remain and then treating it in follow-up.

"There’s really no downside to [conservative or topical management] as long as the patient is reliable," he said.

Taking a careful look at the site during follow-up visits will easily reveal any cell changes that might prompt a fresh biopsy. One finding of note in such cases is the proclivity of dysplastic cells to take a downward course along appendage structures such as eccrine ducts and follicles in the epithelium. "They can go down quite deep ... maybe 2 mm deep to the surface," he said.

In his practice, Dr. Campbell and his colleagues characterize such findings as "advanced actinic keratoses," and note the presence of dysplastic cells along appendage structures.

Dr. Campbell reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – It’s not getting any easier to make the histological distinction between carcinoma in situ and simple dysplasia in a sun-damaged epidermis, but it may be getting less critical to get it right, noted Dr. John B. Campbell.

During his presentation at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery, Dr. Campbell, a Mohs pathologist in private practice in San Diego, showed slides depicting disorderly cells that typify dysplasia extending high up into the epidermis along the edges of specimens containing in situ carcinoma. "There are a lot of things that go along with dysplastic changes," he said. "The nuclei become larger; they stain darker; they have less cytoplasm so that the N/C [nuclear to cytoplasmic] ratio increases."

"At some place along the edges of the specimen you’re going to have to draw a line between in situ carcinoma and simple dysplasia. There are gradations that are somewhat subjective."

Pathologists commonly envision a line midway through the epidermis. If the dark and disorganized cells reach that point, they call it "moderate dysplasia." If they’re clumped in the lower third of the epidermis, it merits a call of "mild dysplasia," and if they extend to near the surface, it’s "severe."

"Dysplastic changes that are wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom are carcinoma in situ," he said. "You’ll need to develop criteria on your own."

In the meantime, the pressure to make the right call may be easing.

"What I’ve seen happening in the last few years is that we’re becoming less and less sensitive about dysplasia at the edges of in situ carcinomas because we can treat them so easily topically," said Dr. Campbell. Beyond watchful waiting or freezing, such regions can now be well managed with topical therapies such as Aldara (imiquimod) or Efudex (fluorouracil).

"Once we’ve cleared the unequivocal carcinoma in situ, people are letting a significant amount of dysplasia remain and then treating it in follow-up.

"There’s really no downside to [conservative or topical management] as long as the patient is reliable," he said.

Taking a careful look at the site during follow-up visits will easily reveal any cell changes that might prompt a fresh biopsy. One finding of note in such cases is the proclivity of dysplastic cells to take a downward course along appendage structures such as eccrine ducts and follicles in the epithelium. "They can go down quite deep ... maybe 2 mm deep to the surface," he said.

In his practice, Dr. Campbell and his colleagues characterize such findings as "advanced actinic keratoses," and note the presence of dysplastic cells along appendage structures.

Dr. Campbell reported no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Mohs Microscope Shopping? Expert Describes Must Haves

SAN DIEGO – Like choosing a cell phone, stereo system, or new car, shopping for a microscope suitable for a Mohs surgery practice can be a delicate balance between what is needed, what is wanted, and how much money there is to spend.

Consumer Reports doesn’t have a special Mohs edition to help out on the microscope hunt, but Dr. Kenneth G. Gross offered his perspective on must-haves, don’t-wants, and "highly desirable features" to look for in a microscope designated for the special needs inherent in Mohs.

For starters, he emphasized that an appropriate microscope is a necessity, not a luxury.

"That little student microscope you used in medical school is really not the kind of microscope you want to use in a Mohs practice. You don’t bring a knife to a gun fight," he said at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

Dr. Gross, a dermatologic surgeon practicing in San Diego, explained that several competitive companies market technical microscopes that work well for Mohs and that all make quality products. He stated no personal preference but recommended shopping for a microscope that contains certain specifications, no matter the manufacturer.

Binocular or Trinocular?

Mohs surgeons really need a microscope with a teaching head – a binocular design – and ideally, the addition of a trinocular scope for photography.

A dual head is valuable not only for teaching or consultation with a resident, colleague, or pathologist, but it also allows for demonstrating to a technician the errors that can thwart a complete and accurate view of a specimen.

A third head for a camera is not 100% necessary, but is very nice to have, according to Dr. Gross.

"Photography is so easy nowadays, it is really stone simple. Everything is through the viewfinder and through the lens," automatically optimizing the F-stop, speed, and color balance.

"That little student microscope you used in medical school is really not the kind of microscope you want to use in a Mohs practice."

"Really, there’s no trick to it," said Dr. Gross. "You just attach a digital camera on top and shoot."

Point it Out

An adjustable, lighted pointer further assists communication and identification of focal regions on a slide.

"If there’s something I don’t see, [the pathologist] can flip on the pointer and say, "There you are, man. There it is."

Focusing on Lenses

Objective lenses, those closest to the specimen, come in three quality levels, and the middle level is acceptable for Mohs, according to Dr. Gross.

The lowest power objective lens should be no bigger than a 2.5x; a 2x is preferable. A 1x or 1.5x is fine as well, but not necessary, he said. With a 2.5x objective lens, "You can orient yourself to a pretty big specimen ... without getting lost."

He compared the view of a large specimen with a 10x objective lens to looking at ink dots and then trying to figure out how they combine to form letters on a book page.

Nose pieces hold five objective lenses, with a 2x, 4x, 10x, 20x, and 40x of middle-quality a good selection.

"You do not need an oil immersion lens on your microscope," he said.

Proper lighting with different lenses is achieved by using swing-out condensers, the best of which "clunk" into place like a solid car door.

The ones that freely slide from side to side are "kind of a piece of junk in my opinion," he said, "because they get out of focus easily."

When it comes to ocular lenses, pony up for the focusable, highest-quality, wide-angle options available, Dr. Gross said.

Each person viewing the specimen should be able to separately focus the image to accommodate individual differences in visual acuity.

Angle for Tilt Heads

Opting for a system with tilt heads isn’t imperative, but is wise if more than one doctor is sharing the microscope, according to Dr. Gross.

"Unless you’re identical twins, you’re going to [have one doctor who is] taller or shorter, sits up straight or slumped, use[s] different style chairs. If you have tilt heads, they’re really easy to adjust."

You can economize, though, by foregoing an option that allows the microscope heads to push in or out. "That’s a waste of money," he said.

Dr. Gross said he had no financial disclosures with regard to any company that manufactures or maintains microscopes used in Mohs surgery.

SAN DIEGO – Like choosing a cell phone, stereo system, or new car, shopping for a microscope suitable for a Mohs surgery practice can be a delicate balance between what is needed, what is wanted, and how much money there is to spend.

Consumer Reports doesn’t have a special Mohs edition to help out on the microscope hunt, but Dr. Kenneth G. Gross offered his perspective on must-haves, don’t-wants, and "highly desirable features" to look for in a microscope designated for the special needs inherent in Mohs.

For starters, he emphasized that an appropriate microscope is a necessity, not a luxury.

"That little student microscope you used in medical school is really not the kind of microscope you want to use in a Mohs practice. You don’t bring a knife to a gun fight," he said at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

Dr. Gross, a dermatologic surgeon practicing in San Diego, explained that several competitive companies market technical microscopes that work well for Mohs and that all make quality products. He stated no personal preference but recommended shopping for a microscope that contains certain specifications, no matter the manufacturer.

Binocular or Trinocular?

Mohs surgeons really need a microscope with a teaching head – a binocular design – and ideally, the addition of a trinocular scope for photography.

A dual head is valuable not only for teaching or consultation with a resident, colleague, or pathologist, but it also allows for demonstrating to a technician the errors that can thwart a complete and accurate view of a specimen.

A third head for a camera is not 100% necessary, but is very nice to have, according to Dr. Gross.

"Photography is so easy nowadays, it is really stone simple. Everything is through the viewfinder and through the lens," automatically optimizing the F-stop, speed, and color balance.

"That little student microscope you used in medical school is really not the kind of microscope you want to use in a Mohs practice."

"Really, there’s no trick to it," said Dr. Gross. "You just attach a digital camera on top and shoot."

Point it Out

An adjustable, lighted pointer further assists communication and identification of focal regions on a slide.

"If there’s something I don’t see, [the pathologist] can flip on the pointer and say, "There you are, man. There it is."

Focusing on Lenses

Objective lenses, those closest to the specimen, come in three quality levels, and the middle level is acceptable for Mohs, according to Dr. Gross.

The lowest power objective lens should be no bigger than a 2.5x; a 2x is preferable. A 1x or 1.5x is fine as well, but not necessary, he said. With a 2.5x objective lens, "You can orient yourself to a pretty big specimen ... without getting lost."

He compared the view of a large specimen with a 10x objective lens to looking at ink dots and then trying to figure out how they combine to form letters on a book page.

Nose pieces hold five objective lenses, with a 2x, 4x, 10x, 20x, and 40x of middle-quality a good selection.

"You do not need an oil immersion lens on your microscope," he said.

Proper lighting with different lenses is achieved by using swing-out condensers, the best of which "clunk" into place like a solid car door.

The ones that freely slide from side to side are "kind of a piece of junk in my opinion," he said, "because they get out of focus easily."

When it comes to ocular lenses, pony up for the focusable, highest-quality, wide-angle options available, Dr. Gross said.

Each person viewing the specimen should be able to separately focus the image to accommodate individual differences in visual acuity.

Angle for Tilt Heads

Opting for a system with tilt heads isn’t imperative, but is wise if more than one doctor is sharing the microscope, according to Dr. Gross.

"Unless you’re identical twins, you’re going to [have one doctor who is] taller or shorter, sits up straight or slumped, use[s] different style chairs. If you have tilt heads, they’re really easy to adjust."

You can economize, though, by foregoing an option that allows the microscope heads to push in or out. "That’s a waste of money," he said.

Dr. Gross said he had no financial disclosures with regard to any company that manufactures or maintains microscopes used in Mohs surgery.

SAN DIEGO – Like choosing a cell phone, stereo system, or new car, shopping for a microscope suitable for a Mohs surgery practice can be a delicate balance between what is needed, what is wanted, and how much money there is to spend.

Consumer Reports doesn’t have a special Mohs edition to help out on the microscope hunt, but Dr. Kenneth G. Gross offered his perspective on must-haves, don’t-wants, and "highly desirable features" to look for in a microscope designated for the special needs inherent in Mohs.

For starters, he emphasized that an appropriate microscope is a necessity, not a luxury.

"That little student microscope you used in medical school is really not the kind of microscope you want to use in a Mohs practice. You don’t bring a knife to a gun fight," he said at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery.

Dr. Gross, a dermatologic surgeon practicing in San Diego, explained that several competitive companies market technical microscopes that work well for Mohs and that all make quality products. He stated no personal preference but recommended shopping for a microscope that contains certain specifications, no matter the manufacturer.

Binocular or Trinocular?

Mohs surgeons really need a microscope with a teaching head – a binocular design – and ideally, the addition of a trinocular scope for photography.

A dual head is valuable not only for teaching or consultation with a resident, colleague, or pathologist, but it also allows for demonstrating to a technician the errors that can thwart a complete and accurate view of a specimen.

A third head for a camera is not 100% necessary, but is very nice to have, according to Dr. Gross.

"Photography is so easy nowadays, it is really stone simple. Everything is through the viewfinder and through the lens," automatically optimizing the F-stop, speed, and color balance.

"That little student microscope you used in medical school is really not the kind of microscope you want to use in a Mohs practice."

"Really, there’s no trick to it," said Dr. Gross. "You just attach a digital camera on top and shoot."

Point it Out

An adjustable, lighted pointer further assists communication and identification of focal regions on a slide.

"If there’s something I don’t see, [the pathologist] can flip on the pointer and say, "There you are, man. There it is."

Focusing on Lenses

Objective lenses, those closest to the specimen, come in three quality levels, and the middle level is acceptable for Mohs, according to Dr. Gross.

The lowest power objective lens should be no bigger than a 2.5x; a 2x is preferable. A 1x or 1.5x is fine as well, but not necessary, he said. With a 2.5x objective lens, "You can orient yourself to a pretty big specimen ... without getting lost."

He compared the view of a large specimen with a 10x objective lens to looking at ink dots and then trying to figure out how they combine to form letters on a book page.

Nose pieces hold five objective lenses, with a 2x, 4x, 10x, 20x, and 40x of middle-quality a good selection.

"You do not need an oil immersion lens on your microscope," he said.

Proper lighting with different lenses is achieved by using swing-out condensers, the best of which "clunk" into place like a solid car door.

The ones that freely slide from side to side are "kind of a piece of junk in my opinion," he said, "because they get out of focus easily."

When it comes to ocular lenses, pony up for the focusable, highest-quality, wide-angle options available, Dr. Gross said.

Each person viewing the specimen should be able to separately focus the image to accommodate individual differences in visual acuity.

Angle for Tilt Heads

Opting for a system with tilt heads isn’t imperative, but is wise if more than one doctor is sharing the microscope, according to Dr. Gross.

"Unless you’re identical twins, you’re going to [have one doctor who is] taller or shorter, sits up straight or slumped, use[s] different style chairs. If you have tilt heads, they’re really easy to adjust."

You can economize, though, by foregoing an option that allows the microscope heads to push in or out. "That’s a waste of money," he said.

Dr. Gross said he had no financial disclosures with regard to any company that manufactures or maintains microscopes used in Mohs surgery.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

‘Keep it Simple,’ for a Satisfactory ASMS Grade

SAN DIEGO – If you want to receive a coveted "satisfactory" grade from peer reviewers of the American Society for Mohs Surgery, "keep it simple," advised Dr. Sharon F. Tiefenbrunn, a member of the ASMS peer review committee..

"The goal of this is to show us that you can recognize a perfect case and can produce a perfect case," she said at a meeting sponsored by the ASMS.

Highly complex or controversial cases are frequently "unreviewable," she noted.

"We don’t want your greatest case, where you worked until almost midnight, and it took 10 stages to clear, and the patient had to have a free flap to repair the defect, and you were ready to tear out your hair and swear off Mohs forever," stressed Dr. Tiefenbrunn, a procedural dermatologist in private practice in St. Louis.

Instead, peer reviewers want to see a stage II to III Mohs case, with tumor evident on stage I and a tumor-free final stage, she said.

Dr. Tiefenbrunn explained that the peer review program was launched in 2000, reviewing cases from the previous year. Its purpose is to improve the quality of Mohs surgery, track the organization’s success in teaching Mohs techniques, and provide practitioners with one of the two episodes of peer review required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA).

Cases are submitted to the ASMS administrative office and cycled to reviewers, who classify them as satisfactory, unreviewable, or "comments only."

A typical comment might be: "not enough overlap to determine clear margin." Such cases are sent to the peer review chairman, who forwards the case, along with a critique, back to the presenter.

In essence, a "comments" case fails to meet peer review standards, while an "unreviewable" case potentially might be corrected according to reviewers’ comments and resubmitted, said Dr. Tiefenbrunn.

Satisfactory cases demonstrate use of standard Mohs technique, have a minimal number of slides, and represent noncontroversial histology.

Some common reasons that cases are judged "unreviewable" include problems with the tumor map and ink legend, failure to mark the tumor on the map, unlabeled sections, confusing slide labeling, use of a nonstandard Mohs technique, bubbles, or a failure to identify tumor on stage I.

Dr. Tiefenbrunn reminded attendees of several cardinal rules, among them the need to include a complete skin edge (at least 90%), a complete deep margin, visible structural details, an adequate stain, visible ink for orientation, and a stage II showing a 2.5-mm margin in every direction.

Reviewers appreciate a legible presenter form; an orderly, precisely drawn map; well-packaged and well-organized slides; and simple explanations for anything on histology, such as actinic keratoses or nevi that might be mistaken for a tumor, said Dr. Tiefenbrunn.

"Presentation matters," she said. "Reviewers are your colleagues who are just as busy as you. We want to whip through these cases and just circle ‘satisfactory’ and go home."

Dr. Tiefenbrunn reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – If you want to receive a coveted "satisfactory" grade from peer reviewers of the American Society for Mohs Surgery, "keep it simple," advised Dr. Sharon F. Tiefenbrunn, a member of the ASMS peer review committee..

"The goal of this is to show us that you can recognize a perfect case and can produce a perfect case," she said at a meeting sponsored by the ASMS.

Highly complex or controversial cases are frequently "unreviewable," she noted.

"We don’t want your greatest case, where you worked until almost midnight, and it took 10 stages to clear, and the patient had to have a free flap to repair the defect, and you were ready to tear out your hair and swear off Mohs forever," stressed Dr. Tiefenbrunn, a procedural dermatologist in private practice in St. Louis.

Instead, peer reviewers want to see a stage II to III Mohs case, with tumor evident on stage I and a tumor-free final stage, she said.

Dr. Tiefenbrunn explained that the peer review program was launched in 2000, reviewing cases from the previous year. Its purpose is to improve the quality of Mohs surgery, track the organization’s success in teaching Mohs techniques, and provide practitioners with one of the two episodes of peer review required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA).

Cases are submitted to the ASMS administrative office and cycled to reviewers, who classify them as satisfactory, unreviewable, or "comments only."

A typical comment might be: "not enough overlap to determine clear margin." Such cases are sent to the peer review chairman, who forwards the case, along with a critique, back to the presenter.

In essence, a "comments" case fails to meet peer review standards, while an "unreviewable" case potentially might be corrected according to reviewers’ comments and resubmitted, said Dr. Tiefenbrunn.

Satisfactory cases demonstrate use of standard Mohs technique, have a minimal number of slides, and represent noncontroversial histology.

Some common reasons that cases are judged "unreviewable" include problems with the tumor map and ink legend, failure to mark the tumor on the map, unlabeled sections, confusing slide labeling, use of a nonstandard Mohs technique, bubbles, or a failure to identify tumor on stage I.

Dr. Tiefenbrunn reminded attendees of several cardinal rules, among them the need to include a complete skin edge (at least 90%), a complete deep margin, visible structural details, an adequate stain, visible ink for orientation, and a stage II showing a 2.5-mm margin in every direction.

Reviewers appreciate a legible presenter form; an orderly, precisely drawn map; well-packaged and well-organized slides; and simple explanations for anything on histology, such as actinic keratoses or nevi that might be mistaken for a tumor, said Dr. Tiefenbrunn.

"Presentation matters," she said. "Reviewers are your colleagues who are just as busy as you. We want to whip through these cases and just circle ‘satisfactory’ and go home."

Dr. Tiefenbrunn reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – If you want to receive a coveted "satisfactory" grade from peer reviewers of the American Society for Mohs Surgery, "keep it simple," advised Dr. Sharon F. Tiefenbrunn, a member of the ASMS peer review committee..

"The goal of this is to show us that you can recognize a perfect case and can produce a perfect case," she said at a meeting sponsored by the ASMS.

Highly complex or controversial cases are frequently "unreviewable," she noted.

"We don’t want your greatest case, where you worked until almost midnight, and it took 10 stages to clear, and the patient had to have a free flap to repair the defect, and you were ready to tear out your hair and swear off Mohs forever," stressed Dr. Tiefenbrunn, a procedural dermatologist in private practice in St. Louis.

Instead, peer reviewers want to see a stage II to III Mohs case, with tumor evident on stage I and a tumor-free final stage, she said.

Dr. Tiefenbrunn explained that the peer review program was launched in 2000, reviewing cases from the previous year. Its purpose is to improve the quality of Mohs surgery, track the organization’s success in teaching Mohs techniques, and provide practitioners with one of the two episodes of peer review required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA).

Cases are submitted to the ASMS administrative office and cycled to reviewers, who classify them as satisfactory, unreviewable, or "comments only."

A typical comment might be: "not enough overlap to determine clear margin." Such cases are sent to the peer review chairman, who forwards the case, along with a critique, back to the presenter.

In essence, a "comments" case fails to meet peer review standards, while an "unreviewable" case potentially might be corrected according to reviewers’ comments and resubmitted, said Dr. Tiefenbrunn.

Satisfactory cases demonstrate use of standard Mohs technique, have a minimal number of slides, and represent noncontroversial histology.

Some common reasons that cases are judged "unreviewable" include problems with the tumor map and ink legend, failure to mark the tumor on the map, unlabeled sections, confusing slide labeling, use of a nonstandard Mohs technique, bubbles, or a failure to identify tumor on stage I.

Dr. Tiefenbrunn reminded attendees of several cardinal rules, among them the need to include a complete skin edge (at least 90%), a complete deep margin, visible structural details, an adequate stain, visible ink for orientation, and a stage II showing a 2.5-mm margin in every direction.

Reviewers appreciate a legible presenter form; an orderly, precisely drawn map; well-packaged and well-organized slides; and simple explanations for anything on histology, such as actinic keratoses or nevi that might be mistaken for a tumor, said Dr. Tiefenbrunn.

"Presentation matters," she said. "Reviewers are your colleagues who are just as busy as you. We want to whip through these cases and just circle ‘satisfactory’ and go home."

Dr. Tiefenbrunn reported no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Protein Kinase Inhibitors Spur Keratoacanthomalike Growths

SAN DIEGO – Sorafenib, an oral agent used to treat advanced kidney cancer and unresectable liver cancer, works like "fertilizer" for lesions resembling keratoacanthomas, producing a multitude of the horny epithelial tumors in oncology patients, according to Dr. Ronald P. Rapini.

Marketed as Nexavar by Onyx Pharmaceuticals and Bayer HealthCare, sorafenib is one of many new protein kinase inhibitors approved and in development for the treatment of various forms of cancer, including leukemia.

The agents have been called "smart drugs" for their ability to mediate signaling pathways that underlie many functions of malignant cells, including growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

"You will see this," Dr. Rapini said at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery. Medical oncologists "are using these [drugs] like crazy."

Other examples of protein kinase inhibitors are imatinib, a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI) marketed by Novartis as Gleevec, for chronic myeloid leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and sunitinib, marketed by Pfizer as Sutent, for GISTs, advanced kidney cancer, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, noted Dr. Rapini, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center and M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

No keratoacanthomatous lesions have been reported to date with bosutinib, a third-generation TKI under investigation by Pfizer for the treatment of various forms of cancer, including leukemia, he said.

The initiation of benign tumor growth is likely secondary to the multikinase inhibitor mechanism of action of the oncologic drugs.

Management of the keratoacanthomalike lesions is not clear; Dr. Rapini said the role of retinoids in such cases is "questionable," with "believers and nonbelievers."

The lesions may regress upon discontinuation of the protein kinase inhibitor; otherwise, they "relentlessly" continue to develop.

Other reported skin reactions seen in conjunction with protein kinase inhibitor therapy include skin rashes, pruritus, blistering, peeling skin, hand-foot skin reaction, and difficulties with wound healing.

Dr. Rapini said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Sorafenib, an oral agent used to treat advanced kidney cancer and unresectable liver cancer, works like "fertilizer" for lesions resembling keratoacanthomas, producing a multitude of the horny epithelial tumors in oncology patients, according to Dr. Ronald P. Rapini.

Marketed as Nexavar by Onyx Pharmaceuticals and Bayer HealthCare, sorafenib is one of many new protein kinase inhibitors approved and in development for the treatment of various forms of cancer, including leukemia.

The agents have been called "smart drugs" for their ability to mediate signaling pathways that underlie many functions of malignant cells, including growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

"You will see this," Dr. Rapini said at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery. Medical oncologists "are using these [drugs] like crazy."

Other examples of protein kinase inhibitors are imatinib, a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI) marketed by Novartis as Gleevec, for chronic myeloid leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and sunitinib, marketed by Pfizer as Sutent, for GISTs, advanced kidney cancer, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, noted Dr. Rapini, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center and M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

No keratoacanthomatous lesions have been reported to date with bosutinib, a third-generation TKI under investigation by Pfizer for the treatment of various forms of cancer, including leukemia, he said.

The initiation of benign tumor growth is likely secondary to the multikinase inhibitor mechanism of action of the oncologic drugs.

Management of the keratoacanthomalike lesions is not clear; Dr. Rapini said the role of retinoids in such cases is "questionable," with "believers and nonbelievers."

The lesions may regress upon discontinuation of the protein kinase inhibitor; otherwise, they "relentlessly" continue to develop.

Other reported skin reactions seen in conjunction with protein kinase inhibitor therapy include skin rashes, pruritus, blistering, peeling skin, hand-foot skin reaction, and difficulties with wound healing.

Dr. Rapini said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Sorafenib, an oral agent used to treat advanced kidney cancer and unresectable liver cancer, works like "fertilizer" for lesions resembling keratoacanthomas, producing a multitude of the horny epithelial tumors in oncology patients, according to Dr. Ronald P. Rapini.

Marketed as Nexavar by Onyx Pharmaceuticals and Bayer HealthCare, sorafenib is one of many new protein kinase inhibitors approved and in development for the treatment of various forms of cancer, including leukemia.

The agents have been called "smart drugs" for their ability to mediate signaling pathways that underlie many functions of malignant cells, including growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

"You will see this," Dr. Rapini said at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery. Medical oncologists "are using these [drugs] like crazy."

Other examples of protein kinase inhibitors are imatinib, a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI) marketed by Novartis as Gleevec, for chronic myeloid leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), and sunitinib, marketed by Pfizer as Sutent, for GISTs, advanced kidney cancer, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, noted Dr. Rapini, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center and M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

No keratoacanthomatous lesions have been reported to date with bosutinib, a third-generation TKI under investigation by Pfizer for the treatment of various forms of cancer, including leukemia, he said.

The initiation of benign tumor growth is likely secondary to the multikinase inhibitor mechanism of action of the oncologic drugs.

Management of the keratoacanthomalike lesions is not clear; Dr. Rapini said the role of retinoids in such cases is "questionable," with "believers and nonbelievers."

The lesions may regress upon discontinuation of the protein kinase inhibitor; otherwise, they "relentlessly" continue to develop.

Other reported skin reactions seen in conjunction with protein kinase inhibitor therapy include skin rashes, pruritus, blistering, peeling skin, hand-foot skin reaction, and difficulties with wound healing.

Dr. Rapini said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Mohs Emergency Preparedness Starts Before the Appointment

SAN DIEGO – A man goes into full cardiopulmonary arrest in the waiting room. A patient coughs up pink frothy sputum during a Mohs surgical procedure. Another pops two ibuprofen 20 minutes before a biopsy and goes into anaphylaxis once the procedure is underway.

These aren’t scenarios concocted for an emergency training film, but real-life events that transpired in the private practice of Dr. Alexander Miller, a Mohs surgeon in private practice in Yorba Linda, Calif.

"Stuff happens," he said during the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery. "You’ve got to be prepared."

Preparedness begins with a preoperative consultation, said Dr. Edward H. Yob, a Mohs surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla., who noted that it’s an "odd week" when he doesn’t find at least one prospective patient with a systolic blood pressure well over 200 mm Hg.

Mohs surgeons who meet their patients for the first time during the surgical appointment might never realize that the patient in his 50s with nitroglycerine on his medication list actually requires the medication 1-2 times a day. Dr. Yob sent this patient for a cardiac consultation, eventually deciding to schedule his procedure in a hospital operating room.

"You have to decide how far you’re going to take this, whether you’re going to monitor patients. In our office, we don’t monitor. We take blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and pulse. [Beyond that], we have our cutoff and say, ‘We won’t operate on this patient in the office,’ " he said.

However, an occasional medical emergency is bound to strike, regardless of how thorough the preoperative workup might be, both surgeons agreed.

For that, planning is the key.

"Designate a 911 caller," suggested Dr. Miller. "[While the staff is] sort of scared and wide-eyed and gaga, [someone needs] to actually call 911."

Likewise, he said, "Train yourself to maintain composure and calmness, and do the steps that are required."

Maintain CPR certification and proficiency, and have the right equipment on hand, he recommended.

Dr. Yob said the extent of equipment required will depend not only on the complexity level of patients accepted for Mohs surgery, but also the practice’s proximity to the hospital.

"How long does it take for an ambulance to get there?" he asked.

At a minimum, an office performing Mohs surgery should have available oxygen, Benadryl, atropine, epinephrine, intravenous supplies, and oral and intravenous dextrose.

An automated external defibrillator is an element of state-of-the-art care, said Dr. Yob.

A review of internet sites found that such units are available for about $2,400 and up, and come with simple instructions designed to be easily followed even in the pressure of an emergency.

Dr. Yob and Dr. Miller reported no disclosures pertaining to their talks.

SAN DIEGO – A man goes into full cardiopulmonary arrest in the waiting room. A patient coughs up pink frothy sputum during a Mohs surgical procedure. Another pops two ibuprofen 20 minutes before a biopsy and goes into anaphylaxis once the procedure is underway.

These aren’t scenarios concocted for an emergency training film, but real-life events that transpired in the private practice of Dr. Alexander Miller, a Mohs surgeon in private practice in Yorba Linda, Calif.

"Stuff happens," he said during the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery. "You’ve got to be prepared."

Preparedness begins with a preoperative consultation, said Dr. Edward H. Yob, a Mohs surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla., who noted that it’s an "odd week" when he doesn’t find at least one prospective patient with a systolic blood pressure well over 200 mm Hg.

Mohs surgeons who meet their patients for the first time during the surgical appointment might never realize that the patient in his 50s with nitroglycerine on his medication list actually requires the medication 1-2 times a day. Dr. Yob sent this patient for a cardiac consultation, eventually deciding to schedule his procedure in a hospital operating room.

"You have to decide how far you’re going to take this, whether you’re going to monitor patients. In our office, we don’t monitor. We take blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and pulse. [Beyond that], we have our cutoff and say, ‘We won’t operate on this patient in the office,’ " he said.

However, an occasional medical emergency is bound to strike, regardless of how thorough the preoperative workup might be, both surgeons agreed.

For that, planning is the key.

"Designate a 911 caller," suggested Dr. Miller. "[While the staff is] sort of scared and wide-eyed and gaga, [someone needs] to actually call 911."

Likewise, he said, "Train yourself to maintain composure and calmness, and do the steps that are required."

Maintain CPR certification and proficiency, and have the right equipment on hand, he recommended.

Dr. Yob said the extent of equipment required will depend not only on the complexity level of patients accepted for Mohs surgery, but also the practice’s proximity to the hospital.

"How long does it take for an ambulance to get there?" he asked.

At a minimum, an office performing Mohs surgery should have available oxygen, Benadryl, atropine, epinephrine, intravenous supplies, and oral and intravenous dextrose.

An automated external defibrillator is an element of state-of-the-art care, said Dr. Yob.

A review of internet sites found that such units are available for about $2,400 and up, and come with simple instructions designed to be easily followed even in the pressure of an emergency.

Dr. Yob and Dr. Miller reported no disclosures pertaining to their talks.

SAN DIEGO – A man goes into full cardiopulmonary arrest in the waiting room. A patient coughs up pink frothy sputum during a Mohs surgical procedure. Another pops two ibuprofen 20 minutes before a biopsy and goes into anaphylaxis once the procedure is underway.

These aren’t scenarios concocted for an emergency training film, but real-life events that transpired in the private practice of Dr. Alexander Miller, a Mohs surgeon in private practice in Yorba Linda, Calif.

"Stuff happens," he said during the meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery. "You’ve got to be prepared."

Preparedness begins with a preoperative consultation, said Dr. Edward H. Yob, a Mohs surgeon in private practice in Tulsa, Okla., who noted that it’s an "odd week" when he doesn’t find at least one prospective patient with a systolic blood pressure well over 200 mm Hg.

Mohs surgeons who meet their patients for the first time during the surgical appointment might never realize that the patient in his 50s with nitroglycerine on his medication list actually requires the medication 1-2 times a day. Dr. Yob sent this patient for a cardiac consultation, eventually deciding to schedule his procedure in a hospital operating room.

"You have to decide how far you’re going to take this, whether you’re going to monitor patients. In our office, we don’t monitor. We take blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and pulse. [Beyond that], we have our cutoff and say, ‘We won’t operate on this patient in the office,’ " he said.

However, an occasional medical emergency is bound to strike, regardless of how thorough the preoperative workup might be, both surgeons agreed.

For that, planning is the key.

"Designate a 911 caller," suggested Dr. Miller. "[While the staff is] sort of scared and wide-eyed and gaga, [someone needs] to actually call 911."

Likewise, he said, "Train yourself to maintain composure and calmness, and do the steps that are required."

Maintain CPR certification and proficiency, and have the right equipment on hand, he recommended.

Dr. Yob said the extent of equipment required will depend not only on the complexity level of patients accepted for Mohs surgery, but also the practice’s proximity to the hospital.

"How long does it take for an ambulance to get there?" he asked.

At a minimum, an office performing Mohs surgery should have available oxygen, Benadryl, atropine, epinephrine, intravenous supplies, and oral and intravenous dextrose.

An automated external defibrillator is an element of state-of-the-art care, said Dr. Yob.

A review of internet sites found that such units are available for about $2,400 and up, and come with simple instructions designed to be easily followed even in the pressure of an emergency.

Dr. Yob and Dr. Miller reported no disclosures pertaining to their talks.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY

Stroke Risk Surges After 10 Years in Diabetes Patients

Major Finding: Study participants with at least a 10-year history of diabetes had more than three times greater risk for stroke than did participants without diabetes.