User login

Hyaluronidase for Skin Necrosis Induced by Amiodarone

To the Editor:

Amiodarone is an oral or intravenous (IV) drug commonly used to treat supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia as well as atrial fibrillation.1 Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of amiodarone include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, thyroid, ocular, neurologic, and cutaneous reactions.1 Long-term use of amiodarone—typically more than 4 months—can lead to slate-gray skin discoloration and photosensitivity, both of which can be reversed with drug withdrawal.2,3 Phlebitis also has been described in less than 3% of patients who receive peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.4

Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis due to extravasation is a rare complication of this antiarrhythmic medication, with only 3 reported cases in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiodarone and skin and (necrosis or ischemia or extravasation or reaction).5–7 Although hyaluronidase is a known therapy for extravasation of fluids, including parenteral nutrition and chemotherapy, its use for the treatment of extravasation from amiodarone is not well documented.6 We report a case of skin necrosis of the left dorsal forearm and the left dorsal and ventral hand following infusion of amiodarone through a peripheral IV line, which was treated with injections of hyaluronidase.

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for sepsis secondary to cholangitis in the setting of an obstructive gallbladder stone. His medical history was notable for multivessel coronary artery disease and atrial flutter treated with ablation. One day after admission, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was attempted and aborted due to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography attempt was made 4 days later, during which the patient underwent cardiac arrest. During this event, amiodarone was administered in a 200-mL solution (1.8 mg/mL) in 5% dextrose through a peripheral IV line in the left forearm. The patient was stabilized and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Twenty-four hours after amiodarone administration, erythema was noted on the left dorsal forearm. Within hours, the digits of the hand became a dark, dusky color, which spread to involve the forearm. Surgical debridement was not deemed necessary; the left arm was elevated, and warm compresses were applied regularly. Within the next week, the skin of the left hand and dorsal forearm had progressively worsened and took on a well-demarcated, dusky blue hue surrounded by an erythematous border involving the proximal forearm and upper arm (Figure 1A). The skin was fragile and had overlying bullae (Figure 1B).

Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into the surrounding areas of erythema, which resolved from the left proximal forearm to the elbow within 2 days after injection (Figure 2). The dusky violaceous patches were persistent, and the necrotic bullae were unchanged. Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into necrotic skin of the left dorsal forearm and dorsal and ventral hand. No improvement was noted on subsequent evaluations of this area. While still an inpatient, he received wound care and twice-daily Doppler ultrasounds in the areas of necrosis. The patient lost sensation in the left hand with increased soft tissue necrosis and developed an eschar on the left dorsal forearm. Due to the progressive loss of function and necrosis, a partial forearm amputation was performed that healed well, and the patient experienced improvement in range of motion of the left upper extremity.

Well-known adverse reactions of amiodarone treatment include pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, and corneal deposits.1 Cutaneous adverse reactions include photosensitivity (phototoxic and photoallergic reactions), hyperpigmentation, pseudoporphyria, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Less commonly, it also can cause urticaria, pruritus, erythema nodosum, purpura, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.3 Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis is rare, first described by Russell and Saltissi5 in 2006 in a 60-year-old man who developed dark discoloration and edema of the forearm 24 hours after initiation of an amiodarone peripheral IV. The patient was treated with hot or cold packs and steroid cream per the pharmaceutical company’s recommendations; however, patient outcomes were not discussed.5 A 77-year-old man who received subcutaneous amiodarone due to misplaced vascular access developed edema and bullae of the forearm followed by tissue necrosis, resulting in notably reduced mobility.6 Fox et al7 described a 60-year-old man who developed atrial fibrillation after emergent spinal fusion and laminectomy. He received intradermal hyaluronidase administration within 24 hours of developing severe pain from extravasation induced by amiodarone with no adverse outcomes and full recovery.7

There are numerous properties of amiodarone that may have resulted in the skin necrosis seen in these cases. The acidic pH (3.5–4.5) of amiodarone can contribute to coagulative necrosis, cellular desiccation, eschar formation, and edema.8 It also can contain additives such as polysorbate and benzyl alcohol, which may contribute to the drug’s vesicant properties.9

Current recommendations for IV administration of amiodarone include delivery through a central vein with high concentrations (>2 mg/mL) because peripheral infusion is slower and may cause phlebitis.4 In-line filters also may be a potential method of preventing phlebitis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.10 Extravasation of amiodarone can be treated nonpharmacologically with limb elevation and warm compresses, as these methods may promote vasodilation and enhance drug removal.5-7 However, when extravasation leads to progressive erythema and skin necrosis or is refractory to these therapies, intradermal injection of hyaluronidase should be considered. Hyaluronidase mediates the degradation of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix, allowing for increased permeability of injected fluids into tissues and diluting the concentration of toxins at the site of exposure.9,11 It has been used to treat extravasation of fluids such as parenteral nutrition, electrolyte infusion, antibiotics, aminophylline, mannitol, and chemotherapy.11 Although hyaluronidase has been recognized as therapeutic for extravasation, there is no established consistent dosing or proper technique. In the setting of infiltration of chemotherapy, doses of hyaluronidase ranging from 150 to 1500 U/mL can be subcutaneously or intradermally injected into the site within 1 hour of extravasation. Side effects of using hyaluronidase are rare, including local pruritus, allergic reactions, urticaria, and angioedema.12

The patient described by Fox et al7 who fully recovered from amiodarone extravasation after hyaluronidase injections likely benefited from quick intervention, as he received amiodarone within 24 hours of the care team identifying initial erythema. Although our patient did have improvement of the areas of erythema on the forearm, evidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis on the left hand and proximal forearm was already apparent and not reversible, most likely caused by late intervention of intradermal hyaluronidase almost a week after the extravasation event. It is important to identify amiodarone as the source of extravasation and administer intradermal hyaluronidase in a timely fashion for extravasation refractory to conventional measurements to prevent progression to severe tissue damage.

Our case draws attention to the risk for skin necrosis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone. Interventions include limb elevation, warm compresses, and consideration of intradermal hyaluronidase within 24 hours of extravasation, as this may reduce the severity of subsequent tissue damage with minimal side effects.

- Epstein AE, Olshansky B, Naccarelli GV, et al. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am J Med. 2016;129:468-475. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039

- Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, et al. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45-51. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45

- Jaworski K, Walecka I, Rudnicka L, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions of amiodarone. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2369-2372. doi:10.12659/MSM.890881

- Kowey Peter R, Marinchak Roger A, Rials Seth J, et al. Intravenous amiodarone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1190-1198. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00069-7

- Russell SJ, Saltissi S. Amiodarone induced skin necrosis. Heart. 2006;92:1395. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.086157

- Grove EL. Skin necrosis and consequences of accidental subcutaneous administration of amiodarone. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V66928.

- Fox AN, Villanueva R, Miller JL. Management of amiodarone extravasation with intradermal hyaluronidase. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1545-1548. doi:10.2146/ajhp160737

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1396

- Le A, Patel S. Extravasation of noncytotoxic drugs: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:870-886. doi:10.1177/1060028014527820

- Slim AM, Roth JE, Duffy B, et al. The incidence of phlebitis with intravenous amiodarone at guideline dose recommendations. Mil Med. 2007;172:1279-1283.

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921-1943. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037

- Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47:297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

To the Editor:

Amiodarone is an oral or intravenous (IV) drug commonly used to treat supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia as well as atrial fibrillation.1 Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of amiodarone include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, thyroid, ocular, neurologic, and cutaneous reactions.1 Long-term use of amiodarone—typically more than 4 months—can lead to slate-gray skin discoloration and photosensitivity, both of which can be reversed with drug withdrawal.2,3 Phlebitis also has been described in less than 3% of patients who receive peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.4

Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis due to extravasation is a rare complication of this antiarrhythmic medication, with only 3 reported cases in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiodarone and skin and (necrosis or ischemia or extravasation or reaction).5–7 Although hyaluronidase is a known therapy for extravasation of fluids, including parenteral nutrition and chemotherapy, its use for the treatment of extravasation from amiodarone is not well documented.6 We report a case of skin necrosis of the left dorsal forearm and the left dorsal and ventral hand following infusion of amiodarone through a peripheral IV line, which was treated with injections of hyaluronidase.

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for sepsis secondary to cholangitis in the setting of an obstructive gallbladder stone. His medical history was notable for multivessel coronary artery disease and atrial flutter treated with ablation. One day after admission, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was attempted and aborted due to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography attempt was made 4 days later, during which the patient underwent cardiac arrest. During this event, amiodarone was administered in a 200-mL solution (1.8 mg/mL) in 5% dextrose through a peripheral IV line in the left forearm. The patient was stabilized and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Twenty-four hours after amiodarone administration, erythema was noted on the left dorsal forearm. Within hours, the digits of the hand became a dark, dusky color, which spread to involve the forearm. Surgical debridement was not deemed necessary; the left arm was elevated, and warm compresses were applied regularly. Within the next week, the skin of the left hand and dorsal forearm had progressively worsened and took on a well-demarcated, dusky blue hue surrounded by an erythematous border involving the proximal forearm and upper arm (Figure 1A). The skin was fragile and had overlying bullae (Figure 1B).

Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into the surrounding areas of erythema, which resolved from the left proximal forearm to the elbow within 2 days after injection (Figure 2). The dusky violaceous patches were persistent, and the necrotic bullae were unchanged. Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into necrotic skin of the left dorsal forearm and dorsal and ventral hand. No improvement was noted on subsequent evaluations of this area. While still an inpatient, he received wound care and twice-daily Doppler ultrasounds in the areas of necrosis. The patient lost sensation in the left hand with increased soft tissue necrosis and developed an eschar on the left dorsal forearm. Due to the progressive loss of function and necrosis, a partial forearm amputation was performed that healed well, and the patient experienced improvement in range of motion of the left upper extremity.

Well-known adverse reactions of amiodarone treatment include pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, and corneal deposits.1 Cutaneous adverse reactions include photosensitivity (phototoxic and photoallergic reactions), hyperpigmentation, pseudoporphyria, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Less commonly, it also can cause urticaria, pruritus, erythema nodosum, purpura, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.3 Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis is rare, first described by Russell and Saltissi5 in 2006 in a 60-year-old man who developed dark discoloration and edema of the forearm 24 hours after initiation of an amiodarone peripheral IV. The patient was treated with hot or cold packs and steroid cream per the pharmaceutical company’s recommendations; however, patient outcomes were not discussed.5 A 77-year-old man who received subcutaneous amiodarone due to misplaced vascular access developed edema and bullae of the forearm followed by tissue necrosis, resulting in notably reduced mobility.6 Fox et al7 described a 60-year-old man who developed atrial fibrillation after emergent spinal fusion and laminectomy. He received intradermal hyaluronidase administration within 24 hours of developing severe pain from extravasation induced by amiodarone with no adverse outcomes and full recovery.7

There are numerous properties of amiodarone that may have resulted in the skin necrosis seen in these cases. The acidic pH (3.5–4.5) of amiodarone can contribute to coagulative necrosis, cellular desiccation, eschar formation, and edema.8 It also can contain additives such as polysorbate and benzyl alcohol, which may contribute to the drug’s vesicant properties.9

Current recommendations for IV administration of amiodarone include delivery through a central vein with high concentrations (>2 mg/mL) because peripheral infusion is slower and may cause phlebitis.4 In-line filters also may be a potential method of preventing phlebitis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.10 Extravasation of amiodarone can be treated nonpharmacologically with limb elevation and warm compresses, as these methods may promote vasodilation and enhance drug removal.5-7 However, when extravasation leads to progressive erythema and skin necrosis or is refractory to these therapies, intradermal injection of hyaluronidase should be considered. Hyaluronidase mediates the degradation of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix, allowing for increased permeability of injected fluids into tissues and diluting the concentration of toxins at the site of exposure.9,11 It has been used to treat extravasation of fluids such as parenteral nutrition, electrolyte infusion, antibiotics, aminophylline, mannitol, and chemotherapy.11 Although hyaluronidase has been recognized as therapeutic for extravasation, there is no established consistent dosing or proper technique. In the setting of infiltration of chemotherapy, doses of hyaluronidase ranging from 150 to 1500 U/mL can be subcutaneously or intradermally injected into the site within 1 hour of extravasation. Side effects of using hyaluronidase are rare, including local pruritus, allergic reactions, urticaria, and angioedema.12

The patient described by Fox et al7 who fully recovered from amiodarone extravasation after hyaluronidase injections likely benefited from quick intervention, as he received amiodarone within 24 hours of the care team identifying initial erythema. Although our patient did have improvement of the areas of erythema on the forearm, evidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis on the left hand and proximal forearm was already apparent and not reversible, most likely caused by late intervention of intradermal hyaluronidase almost a week after the extravasation event. It is important to identify amiodarone as the source of extravasation and administer intradermal hyaluronidase in a timely fashion for extravasation refractory to conventional measurements to prevent progression to severe tissue damage.

Our case draws attention to the risk for skin necrosis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone. Interventions include limb elevation, warm compresses, and consideration of intradermal hyaluronidase within 24 hours of extravasation, as this may reduce the severity of subsequent tissue damage with minimal side effects.

To the Editor:

Amiodarone is an oral or intravenous (IV) drug commonly used to treat supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia as well as atrial fibrillation.1 Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of amiodarone include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, thyroid, ocular, neurologic, and cutaneous reactions.1 Long-term use of amiodarone—typically more than 4 months—can lead to slate-gray skin discoloration and photosensitivity, both of which can be reversed with drug withdrawal.2,3 Phlebitis also has been described in less than 3% of patients who receive peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.4

Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis due to extravasation is a rare complication of this antiarrhythmic medication, with only 3 reported cases in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiodarone and skin and (necrosis or ischemia or extravasation or reaction).5–7 Although hyaluronidase is a known therapy for extravasation of fluids, including parenteral nutrition and chemotherapy, its use for the treatment of extravasation from amiodarone is not well documented.6 We report a case of skin necrosis of the left dorsal forearm and the left dorsal and ventral hand following infusion of amiodarone through a peripheral IV line, which was treated with injections of hyaluronidase.

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for sepsis secondary to cholangitis in the setting of an obstructive gallbladder stone. His medical history was notable for multivessel coronary artery disease and atrial flutter treated with ablation. One day after admission, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was attempted and aborted due to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography attempt was made 4 days later, during which the patient underwent cardiac arrest. During this event, amiodarone was administered in a 200-mL solution (1.8 mg/mL) in 5% dextrose through a peripheral IV line in the left forearm. The patient was stabilized and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Twenty-four hours after amiodarone administration, erythema was noted on the left dorsal forearm. Within hours, the digits of the hand became a dark, dusky color, which spread to involve the forearm. Surgical debridement was not deemed necessary; the left arm was elevated, and warm compresses were applied regularly. Within the next week, the skin of the left hand and dorsal forearm had progressively worsened and took on a well-demarcated, dusky blue hue surrounded by an erythematous border involving the proximal forearm and upper arm (Figure 1A). The skin was fragile and had overlying bullae (Figure 1B).

Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into the surrounding areas of erythema, which resolved from the left proximal forearm to the elbow within 2 days after injection (Figure 2). The dusky violaceous patches were persistent, and the necrotic bullae were unchanged. Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into necrotic skin of the left dorsal forearm and dorsal and ventral hand. No improvement was noted on subsequent evaluations of this area. While still an inpatient, he received wound care and twice-daily Doppler ultrasounds in the areas of necrosis. The patient lost sensation in the left hand with increased soft tissue necrosis and developed an eschar on the left dorsal forearm. Due to the progressive loss of function and necrosis, a partial forearm amputation was performed that healed well, and the patient experienced improvement in range of motion of the left upper extremity.

Well-known adverse reactions of amiodarone treatment include pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, and corneal deposits.1 Cutaneous adverse reactions include photosensitivity (phototoxic and photoallergic reactions), hyperpigmentation, pseudoporphyria, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Less commonly, it also can cause urticaria, pruritus, erythema nodosum, purpura, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.3 Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis is rare, first described by Russell and Saltissi5 in 2006 in a 60-year-old man who developed dark discoloration and edema of the forearm 24 hours after initiation of an amiodarone peripheral IV. The patient was treated with hot or cold packs and steroid cream per the pharmaceutical company’s recommendations; however, patient outcomes were not discussed.5 A 77-year-old man who received subcutaneous amiodarone due to misplaced vascular access developed edema and bullae of the forearm followed by tissue necrosis, resulting in notably reduced mobility.6 Fox et al7 described a 60-year-old man who developed atrial fibrillation after emergent spinal fusion and laminectomy. He received intradermal hyaluronidase administration within 24 hours of developing severe pain from extravasation induced by amiodarone with no adverse outcomes and full recovery.7

There are numerous properties of amiodarone that may have resulted in the skin necrosis seen in these cases. The acidic pH (3.5–4.5) of amiodarone can contribute to coagulative necrosis, cellular desiccation, eschar formation, and edema.8 It also can contain additives such as polysorbate and benzyl alcohol, which may contribute to the drug’s vesicant properties.9

Current recommendations for IV administration of amiodarone include delivery through a central vein with high concentrations (>2 mg/mL) because peripheral infusion is slower and may cause phlebitis.4 In-line filters also may be a potential method of preventing phlebitis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.10 Extravasation of amiodarone can be treated nonpharmacologically with limb elevation and warm compresses, as these methods may promote vasodilation and enhance drug removal.5-7 However, when extravasation leads to progressive erythema and skin necrosis or is refractory to these therapies, intradermal injection of hyaluronidase should be considered. Hyaluronidase mediates the degradation of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix, allowing for increased permeability of injected fluids into tissues and diluting the concentration of toxins at the site of exposure.9,11 It has been used to treat extravasation of fluids such as parenteral nutrition, electrolyte infusion, antibiotics, aminophylline, mannitol, and chemotherapy.11 Although hyaluronidase has been recognized as therapeutic for extravasation, there is no established consistent dosing or proper technique. In the setting of infiltration of chemotherapy, doses of hyaluronidase ranging from 150 to 1500 U/mL can be subcutaneously or intradermally injected into the site within 1 hour of extravasation. Side effects of using hyaluronidase are rare, including local pruritus, allergic reactions, urticaria, and angioedema.12

The patient described by Fox et al7 who fully recovered from amiodarone extravasation after hyaluronidase injections likely benefited from quick intervention, as he received amiodarone within 24 hours of the care team identifying initial erythema. Although our patient did have improvement of the areas of erythema on the forearm, evidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis on the left hand and proximal forearm was already apparent and not reversible, most likely caused by late intervention of intradermal hyaluronidase almost a week after the extravasation event. It is important to identify amiodarone as the source of extravasation and administer intradermal hyaluronidase in a timely fashion for extravasation refractory to conventional measurements to prevent progression to severe tissue damage.

Our case draws attention to the risk for skin necrosis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone. Interventions include limb elevation, warm compresses, and consideration of intradermal hyaluronidase within 24 hours of extravasation, as this may reduce the severity of subsequent tissue damage with minimal side effects.

- Epstein AE, Olshansky B, Naccarelli GV, et al. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am J Med. 2016;129:468-475. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039

- Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, et al. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45-51. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45

- Jaworski K, Walecka I, Rudnicka L, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions of amiodarone. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2369-2372. doi:10.12659/MSM.890881

- Kowey Peter R, Marinchak Roger A, Rials Seth J, et al. Intravenous amiodarone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1190-1198. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00069-7

- Russell SJ, Saltissi S. Amiodarone induced skin necrosis. Heart. 2006;92:1395. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.086157

- Grove EL. Skin necrosis and consequences of accidental subcutaneous administration of amiodarone. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V66928.

- Fox AN, Villanueva R, Miller JL. Management of amiodarone extravasation with intradermal hyaluronidase. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1545-1548. doi:10.2146/ajhp160737

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1396

- Le A, Patel S. Extravasation of noncytotoxic drugs: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:870-886. doi:10.1177/1060028014527820

- Slim AM, Roth JE, Duffy B, et al. The incidence of phlebitis with intravenous amiodarone at guideline dose recommendations. Mil Med. 2007;172:1279-1283.

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921-1943. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037

- Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47:297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

- Epstein AE, Olshansky B, Naccarelli GV, et al. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am J Med. 2016;129:468-475. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039

- Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, et al. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45-51. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45

- Jaworski K, Walecka I, Rudnicka L, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions of amiodarone. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2369-2372. doi:10.12659/MSM.890881

- Kowey Peter R, Marinchak Roger A, Rials Seth J, et al. Intravenous amiodarone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1190-1198. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00069-7

- Russell SJ, Saltissi S. Amiodarone induced skin necrosis. Heart. 2006;92:1395. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.086157

- Grove EL. Skin necrosis and consequences of accidental subcutaneous administration of amiodarone. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V66928.

- Fox AN, Villanueva R, Miller JL. Management of amiodarone extravasation with intradermal hyaluronidase. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1545-1548. doi:10.2146/ajhp160737

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1396

- Le A, Patel S. Extravasation of noncytotoxic drugs: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:870-886. doi:10.1177/1060028014527820

- Slim AM, Roth JE, Duffy B, et al. The incidence of phlebitis with intravenous amiodarone at guideline dose recommendations. Mil Med. 2007;172:1279-1283.

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921-1943. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037

- Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47:297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

Practice Points

- Intravenous amiodarone administered peripherally can induce skin extravasation, leading to necrosis.

- Dermatologists should be aware that early intervention with intradermal hyaluronidase may reduce the severity of tissue damage caused by amiodarone-induced skin necrosis.

Diffuse annular lesions

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

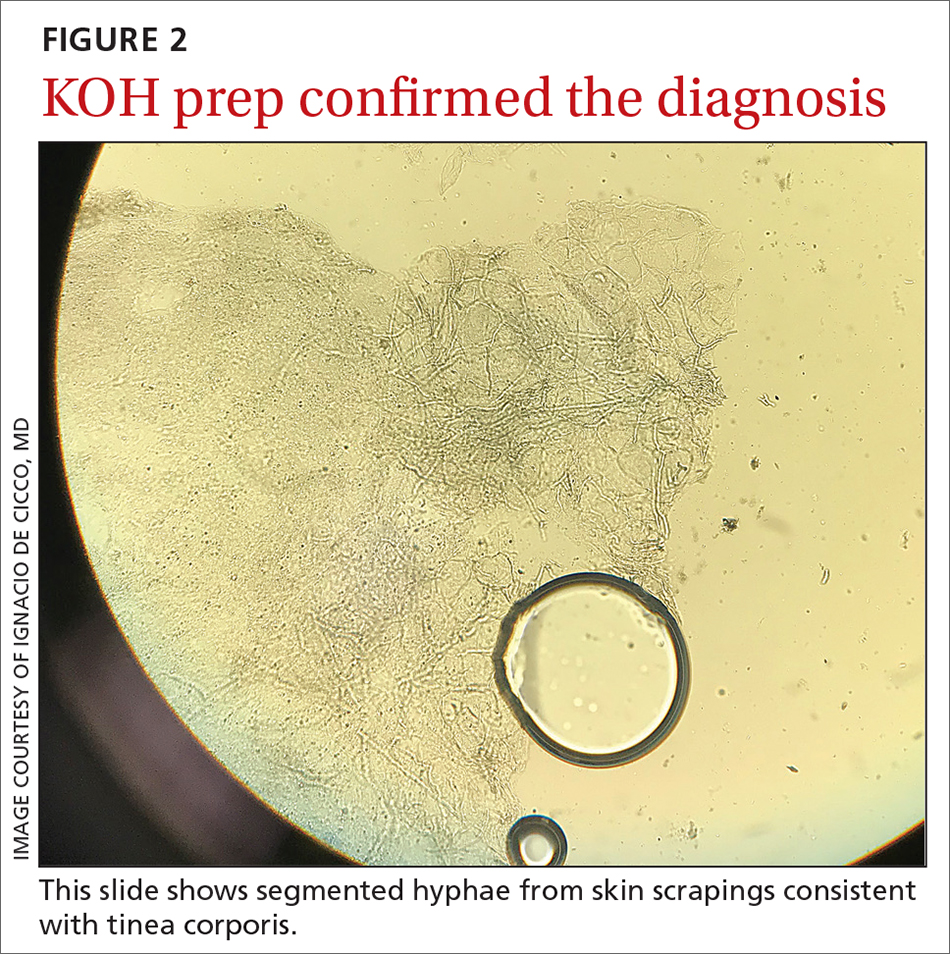

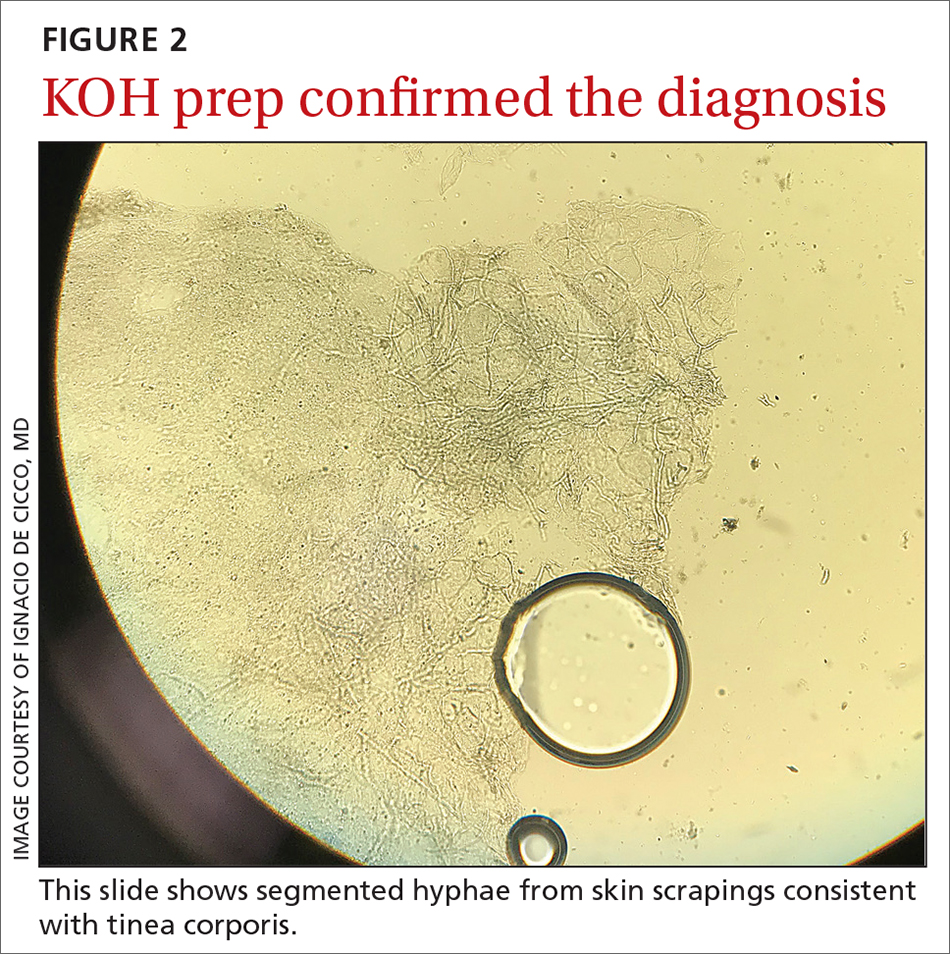

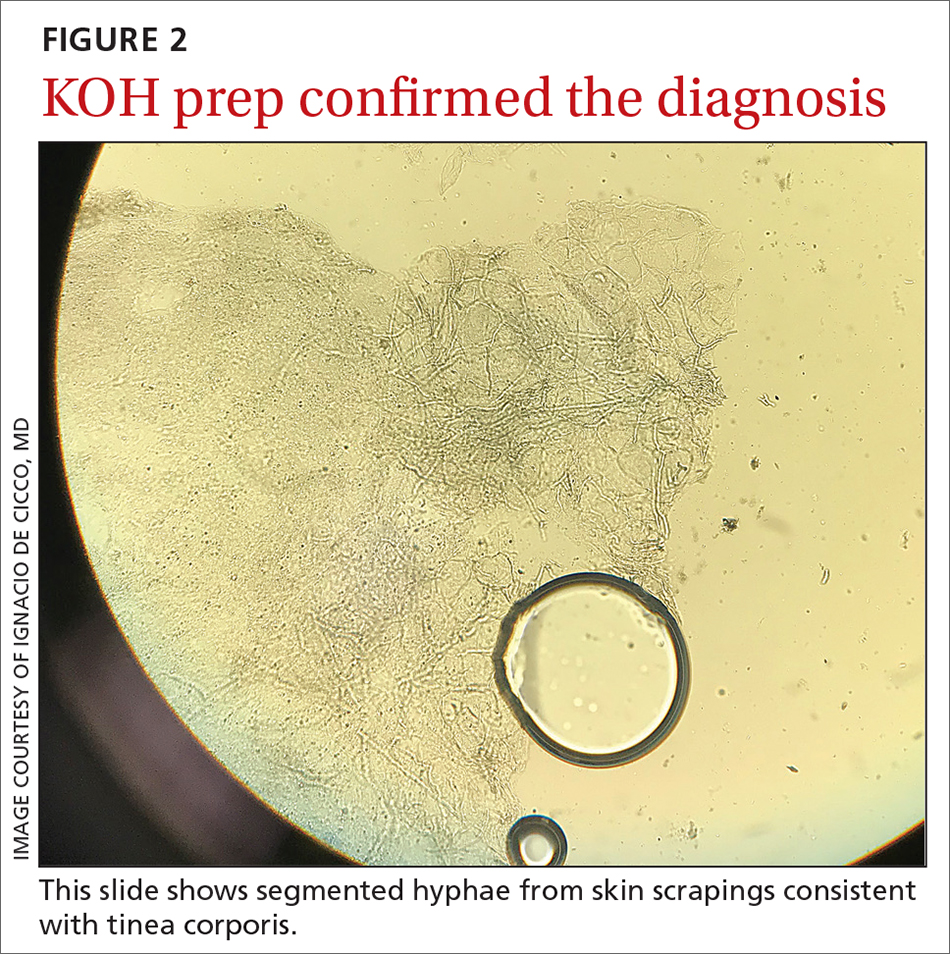

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835