User login

Calcinosis Cutis Associated With Subcutaneous Glatiramer Acetate

To the Editor:

Calcinosis cutis is a condition characterized by the deposition of insoluble calcium salts in the skin. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is the most common type, occurring in previously traumatized skin in the absence of abnormal blood calcium levels. It commonly is seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and is thought to be precipitated by chronic inflammation and vascular hypoxia.1 Herein, we describe a case of calcinosis cutis arising after treatment with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an agent that is effective for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Diagnostic workup and treatment modalities for calcinosis cutis in this patient population should be considered in the context of minimizing interruption or discontinuation of this disease-modifying agent.

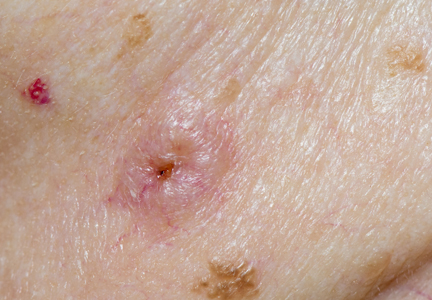

A 53-year-old woman with a history of relapsing-remitting MS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with multiple firm asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the thighs of 1 year’s duration that were increasing in number. The involved areas were the injection sites of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator for the treatment of MS, which our patient self-administered 3 times weekly. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to white, firm, and nontender nodules on the thighs (Figure). There was no epidermal change, and she had no other skin involvement. A punch biopsy of one of the nodules revealed calcium deposits in collagen bundles of the deep dermis. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels were within reference range. She declined further treatment for the calcinosis cutis and opted to continue treatment with glatiramer acetate, as her MS was well controlled on this medication.

Glatiramer acetate is an immunogenic polypeptide injectable that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.2 It is composed of synthetic polypeptides and contains 4 naturally occurring amino acids. Glatiramer acetate is administered subcutaneously as 20 mg/mL/d or 40 mg/mL 3 times weekly. Transient injection-site reactions are the most common cutaneous adverse events and include localized edema, induration, erythema, pain, and pruritus.3 There have been multiple reports of lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis as well as embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome).4,5 Our case of calcinosis cutis related to glatiramer acetate is unique. The mechanism of calcinosis cutis in our patient likely was dystrophic due to tissue damage, rather than due to the injection of a calcium-containing substance. Our patient’s history of SLE is a notable risk factor for the development of calcinosis cutis, likely incited by the trauma occurring with subcutaneous injections.6

The mainstay of treatment for localized calcinosis cutis in the setting of connective tissue disease is surgical excision as well as treatment of the underlying disorder. Potential therapies include calcium channel blockers, warfarin, bisphosphonates, intravenous immunoglobulin, minocycline, colchicine, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, intralesional corticosteroids, intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and CO2 laser.1,6 Our patient was already on intravenous immunoglobulin for MS and hydroxychloroquine for SLE. In select cases where the patient is asymptomatic and prefers not to pursue treatment, no treatment is necessary.

Although calcinosis cutis may occur in SLE alone, it is uncommon and usually is seen in chronic severe SLE, where calcification usually occurs in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous lupus.4 This case report of calcinosis cutis following treatment with glatiramer acetate highlights some of the cutaneous side effects associated with glatiramer acetate injections and should prompt practitioners to consider dystrophic calcinosis cutis in patients requiring subcutaneous medications, particularly in those with pre-existing connective tissue disease.

- Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:542-548.

- Copaxone. Prescribing information. Teva Neuroscience, Inc; 2022. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.copaxone.com/globalassets/copaxone/prescribing-information.pdf

- McKeage K. Glatiramer acetate 40 mg/mL in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:425-432.

- Balak DMW, Hengstman GJD, Çakmak A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705-1717.

- Watkins CE, Litchfield J, Youngberg G, et al. Glatiramer acetate-induced lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis. Cutis. 2015;95:E26-E30.

- Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1-12.

To the Editor:

Calcinosis cutis is a condition characterized by the deposition of insoluble calcium salts in the skin. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is the most common type, occurring in previously traumatized skin in the absence of abnormal blood calcium levels. It commonly is seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and is thought to be precipitated by chronic inflammation and vascular hypoxia.1 Herein, we describe a case of calcinosis cutis arising after treatment with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an agent that is effective for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Diagnostic workup and treatment modalities for calcinosis cutis in this patient population should be considered in the context of minimizing interruption or discontinuation of this disease-modifying agent.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of relapsing-remitting MS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with multiple firm asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the thighs of 1 year’s duration that were increasing in number. The involved areas were the injection sites of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator for the treatment of MS, which our patient self-administered 3 times weekly. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to white, firm, and nontender nodules on the thighs (Figure). There was no epidermal change, and she had no other skin involvement. A punch biopsy of one of the nodules revealed calcium deposits in collagen bundles of the deep dermis. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels were within reference range. She declined further treatment for the calcinosis cutis and opted to continue treatment with glatiramer acetate, as her MS was well controlled on this medication.

Glatiramer acetate is an immunogenic polypeptide injectable that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.2 It is composed of synthetic polypeptides and contains 4 naturally occurring amino acids. Glatiramer acetate is administered subcutaneously as 20 mg/mL/d or 40 mg/mL 3 times weekly. Transient injection-site reactions are the most common cutaneous adverse events and include localized edema, induration, erythema, pain, and pruritus.3 There have been multiple reports of lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis as well as embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome).4,5 Our case of calcinosis cutis related to glatiramer acetate is unique. The mechanism of calcinosis cutis in our patient likely was dystrophic due to tissue damage, rather than due to the injection of a calcium-containing substance. Our patient’s history of SLE is a notable risk factor for the development of calcinosis cutis, likely incited by the trauma occurring with subcutaneous injections.6

The mainstay of treatment for localized calcinosis cutis in the setting of connective tissue disease is surgical excision as well as treatment of the underlying disorder. Potential therapies include calcium channel blockers, warfarin, bisphosphonates, intravenous immunoglobulin, minocycline, colchicine, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, intralesional corticosteroids, intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and CO2 laser.1,6 Our patient was already on intravenous immunoglobulin for MS and hydroxychloroquine for SLE. In select cases where the patient is asymptomatic and prefers not to pursue treatment, no treatment is necessary.

Although calcinosis cutis may occur in SLE alone, it is uncommon and usually is seen in chronic severe SLE, where calcification usually occurs in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous lupus.4 This case report of calcinosis cutis following treatment with glatiramer acetate highlights some of the cutaneous side effects associated with glatiramer acetate injections and should prompt practitioners to consider dystrophic calcinosis cutis in patients requiring subcutaneous medications, particularly in those with pre-existing connective tissue disease.

To the Editor:

Calcinosis cutis is a condition characterized by the deposition of insoluble calcium salts in the skin. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is the most common type, occurring in previously traumatized skin in the absence of abnormal blood calcium levels. It commonly is seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and is thought to be precipitated by chronic inflammation and vascular hypoxia.1 Herein, we describe a case of calcinosis cutis arising after treatment with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an agent that is effective for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Diagnostic workup and treatment modalities for calcinosis cutis in this patient population should be considered in the context of minimizing interruption or discontinuation of this disease-modifying agent.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of relapsing-remitting MS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with multiple firm asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the thighs of 1 year’s duration that were increasing in number. The involved areas were the injection sites of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator for the treatment of MS, which our patient self-administered 3 times weekly. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to white, firm, and nontender nodules on the thighs (Figure). There was no epidermal change, and she had no other skin involvement. A punch biopsy of one of the nodules revealed calcium deposits in collagen bundles of the deep dermis. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels were within reference range. She declined further treatment for the calcinosis cutis and opted to continue treatment with glatiramer acetate, as her MS was well controlled on this medication.

Glatiramer acetate is an immunogenic polypeptide injectable that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.2 It is composed of synthetic polypeptides and contains 4 naturally occurring amino acids. Glatiramer acetate is administered subcutaneously as 20 mg/mL/d or 40 mg/mL 3 times weekly. Transient injection-site reactions are the most common cutaneous adverse events and include localized edema, induration, erythema, pain, and pruritus.3 There have been multiple reports of lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis as well as embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome).4,5 Our case of calcinosis cutis related to glatiramer acetate is unique. The mechanism of calcinosis cutis in our patient likely was dystrophic due to tissue damage, rather than due to the injection of a calcium-containing substance. Our patient’s history of SLE is a notable risk factor for the development of calcinosis cutis, likely incited by the trauma occurring with subcutaneous injections.6

The mainstay of treatment for localized calcinosis cutis in the setting of connective tissue disease is surgical excision as well as treatment of the underlying disorder. Potential therapies include calcium channel blockers, warfarin, bisphosphonates, intravenous immunoglobulin, minocycline, colchicine, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, intralesional corticosteroids, intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and CO2 laser.1,6 Our patient was already on intravenous immunoglobulin for MS and hydroxychloroquine for SLE. In select cases where the patient is asymptomatic and prefers not to pursue treatment, no treatment is necessary.

Although calcinosis cutis may occur in SLE alone, it is uncommon and usually is seen in chronic severe SLE, where calcification usually occurs in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous lupus.4 This case report of calcinosis cutis following treatment with glatiramer acetate highlights some of the cutaneous side effects associated with glatiramer acetate injections and should prompt practitioners to consider dystrophic calcinosis cutis in patients requiring subcutaneous medications, particularly in those with pre-existing connective tissue disease.

- Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:542-548.

- Copaxone. Prescribing information. Teva Neuroscience, Inc; 2022. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.copaxone.com/globalassets/copaxone/prescribing-information.pdf

- McKeage K. Glatiramer acetate 40 mg/mL in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:425-432.

- Balak DMW, Hengstman GJD, Çakmak A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705-1717.

- Watkins CE, Litchfield J, Youngberg G, et al. Glatiramer acetate-induced lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis. Cutis. 2015;95:E26-E30.

- Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1-12.

- Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:542-548.

- Copaxone. Prescribing information. Teva Neuroscience, Inc; 2022. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.copaxone.com/globalassets/copaxone/prescribing-information.pdf

- McKeage K. Glatiramer acetate 40 mg/mL in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:425-432.

- Balak DMW, Hengstman GJD, Çakmak A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705-1717.

- Watkins CE, Litchfield J, Youngberg G, et al. Glatiramer acetate-induced lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis. Cutis. 2015;95:E26-E30.

- Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1-12.

Practice Points

- Glatiramer acetate is a subcutaneous injection utilized for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, and common adverse effects include injection-site reactions such as calcinosis cutis.

- Development of calcinosis cutis in association with glatiramer acetate is not an indication for medication discontinuation.

- Dermatologists should be aware of this potential association, and treatment should be considered in cases of symptomatic calcinosis cutis.

Electronic Brachytherapy: Overused and Overpriced?

The introduction of high-density radiation electronic brachytherapy (eBX) for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers has induced great angst within the dermatology community.1 The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 0182T (high dose rate eBX) reimburses at an extraordinarily high rate, which has drawn a substantial amount of attention. Some critics see it as another case of overutilization, of sucking more money out of a bleeding Medicare system. The financial opportunity afforded by eBX has even led some entrepreneurs to purchase dermatology clinics so that skin cancer patients can be treated via this modality instead of more traditional and less costly techniques (personal communication, 2014).

Among radiation oncologists, high-density radiation eBX is considered to be an important treatment option for select patients who have skin cancers staged as T1 or T2 tumors that are 4 cm or smaller in diameter and 5 mm or less in depth.2 Additionally, ideal candidates for nonsurgical treatment options such as eBX include patients with lesions in cosmetically challenging areas (eg, ears, nose), those who may experience problematic wound healing due to tumor location (eg, lower extremities) or medical conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease), those with medical comorbidities that may preclude them from surgery, those currently taking anticoagulants, and those who are not interested in undergoing surgery.

A common criticism of eBX is that there is little data on long-term treatment outcomes, which will soon be addressed by a 5-year multicenter, prospective, randomized study of 720 patients with basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma led by the University of California, Irvine, and the University of California, San Diego (study protocol currently with institutional review board). Another criticism is that some manufacturers of eBX devices gained the less rigorous US Food and Drug Administration Premarket Notification 510(k) certification; however, this certification is quite commonplace in the United States, and an examination of the data actually shows a lower recall rate with this method when compared to the longer premarket approval application process.3 A more important criticism of eBX might be that radiation therapy is associated with a substantial increase in skin cancers that may occur decades later in irradiated areas; however, there remains a paucity of studies examining the safety data on eBX during the posttreatment period when such effects would be expected.

In practice, the forces for good and evil are not only limited to those who utilize eBX. It is widely known that CPT codes for Mohs micrographic surgery also have been abused—that is, the procedure has been used in circumstances where it was not absolutely necessary4—which led to an effort by dermatologic surgery organizations to agree on appropriate use criteria for Mohs surgery.5 These criteria are not perfect but should help curb the misuse of a valuable technique, which is one that is recognized as being optimal for the treatment of complex skin cancers. One might suggest forming similar appropriate use criteria for eBX and limiting this treatment to patients who either are older than 65 years, have serious medical issues, are currently taking anticoagulants, are immobile, or simply cannot handle further dermatologic surgeries.

The American Medical Association has developed new Category III CPT codes for treatment of the skin with eBX that will become effective January 2016.6 These codes take into consideration the need for a radiation oncologist and a physicist to be present for planning, dosimetry, simulation, and selection of parameters for the appropriate depth. Although I do not know the reimbursement rates for these new codes yet, they will likely be substantially less than the current payment for treatment with eBX. That said, the gravy train has left the station, and those who have invested in the devices for eBX will either see the benefit of continued treatment for their patients or divest themselves of eBX now that the reimbursement will be more modest.

Some of my dermatology colleagues, who also are some of my very good friends, have a visceral and absolute objection to the use of any form of radiation therapy, and I respect their opinions. However, eBX does play a role in treating cutaneous malignancies, and our radiation oncology colleagues—many who treat patients with extensive, aggressive, and recurrent skin cancers—also have a place at the table.

Speaking as a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon and a department chair, I am very aware that the teaching we provide today for our dermatology residents and fellows is likely to be their modus operandi for the future, a future in which the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will force physicians to carefully choose quality of care over personal gain and where financial rewards will be based on appropriate utilization and measurable outcomes. Electronic brachytherapy is one tool amongst many. I have a plethora of patients in their 70s and 80s who have given up on surgery for skin cancer and who would prefer painless treatment with eBX, which allows for the appropriate use of such a controversial therapy.

Acknowledgments—I would like to thank Janellen Smith, MD (Irvine, California), Joshua Spanogle, MD (Saint Augustine, Florida), and Jordan V. Wang, MBE (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for their constructive comments.

1. Linos E, VanBeek M, Resneck JS Jr. A sudden and concerning increase in the use of electronic brachytherapy for skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:699-700.

2. Bhatnagar A. Nonmelanoma skin cancer treated with electronic brachytherapy: results at 1 year [published online ahead of print January 9, 2013]. Brachytherapy. 2013;12:134-140.

3. Connor JT, Lewis RJ, Berry DA, et al. FDA recalls not as alarming as they seem. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1044-1046.

4. Goldman G. Mohs surgery comes under the microscope. Member to Member American Academy of Dermatology E-newsletter. https://www.aad.org/members/publications /member-to-member/2013-archive/november-8-2013 /mohs-surgery-comes-under-the-microscope. Published November 8, 2013. Accessed August 10, 2015.

5. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery [published online ahead of print September 5, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

6. ACR Radiology Coding Source: CPT 2016 anticipated code changes. American College of Radiology Web site. http://www.acr.org/Advocacy/Economics-Health-Policy /Billing-Coding/Coding-Source-List/2015/Mar-Apr-2015 /CPT-2016-Anticipated-Code-Changes. Published March 2015. Accessed August 21, 2015.

The introduction of high-density radiation electronic brachytherapy (eBX) for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers has induced great angst within the dermatology community.1 The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 0182T (high dose rate eBX) reimburses at an extraordinarily high rate, which has drawn a substantial amount of attention. Some critics see it as another case of overutilization, of sucking more money out of a bleeding Medicare system. The financial opportunity afforded by eBX has even led some entrepreneurs to purchase dermatology clinics so that skin cancer patients can be treated via this modality instead of more traditional and less costly techniques (personal communication, 2014).

Among radiation oncologists, high-density radiation eBX is considered to be an important treatment option for select patients who have skin cancers staged as T1 or T2 tumors that are 4 cm or smaller in diameter and 5 mm or less in depth.2 Additionally, ideal candidates for nonsurgical treatment options such as eBX include patients with lesions in cosmetically challenging areas (eg, ears, nose), those who may experience problematic wound healing due to tumor location (eg, lower extremities) or medical conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease), those with medical comorbidities that may preclude them from surgery, those currently taking anticoagulants, and those who are not interested in undergoing surgery.

A common criticism of eBX is that there is little data on long-term treatment outcomes, which will soon be addressed by a 5-year multicenter, prospective, randomized study of 720 patients with basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma led by the University of California, Irvine, and the University of California, San Diego (study protocol currently with institutional review board). Another criticism is that some manufacturers of eBX devices gained the less rigorous US Food and Drug Administration Premarket Notification 510(k) certification; however, this certification is quite commonplace in the United States, and an examination of the data actually shows a lower recall rate with this method when compared to the longer premarket approval application process.3 A more important criticism of eBX might be that radiation therapy is associated with a substantial increase in skin cancers that may occur decades later in irradiated areas; however, there remains a paucity of studies examining the safety data on eBX during the posttreatment period when such effects would be expected.

In practice, the forces for good and evil are not only limited to those who utilize eBX. It is widely known that CPT codes for Mohs micrographic surgery also have been abused—that is, the procedure has been used in circumstances where it was not absolutely necessary4—which led to an effort by dermatologic surgery organizations to agree on appropriate use criteria for Mohs surgery.5 These criteria are not perfect but should help curb the misuse of a valuable technique, which is one that is recognized as being optimal for the treatment of complex skin cancers. One might suggest forming similar appropriate use criteria for eBX and limiting this treatment to patients who either are older than 65 years, have serious medical issues, are currently taking anticoagulants, are immobile, or simply cannot handle further dermatologic surgeries.

The American Medical Association has developed new Category III CPT codes for treatment of the skin with eBX that will become effective January 2016.6 These codes take into consideration the need for a radiation oncologist and a physicist to be present for planning, dosimetry, simulation, and selection of parameters for the appropriate depth. Although I do not know the reimbursement rates for these new codes yet, they will likely be substantially less than the current payment for treatment with eBX. That said, the gravy train has left the station, and those who have invested in the devices for eBX will either see the benefit of continued treatment for their patients or divest themselves of eBX now that the reimbursement will be more modest.

Some of my dermatology colleagues, who also are some of my very good friends, have a visceral and absolute objection to the use of any form of radiation therapy, and I respect their opinions. However, eBX does play a role in treating cutaneous malignancies, and our radiation oncology colleagues—many who treat patients with extensive, aggressive, and recurrent skin cancers—also have a place at the table.

Speaking as a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon and a department chair, I am very aware that the teaching we provide today for our dermatology residents and fellows is likely to be their modus operandi for the future, a future in which the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will force physicians to carefully choose quality of care over personal gain and where financial rewards will be based on appropriate utilization and measurable outcomes. Electronic brachytherapy is one tool amongst many. I have a plethora of patients in their 70s and 80s who have given up on surgery for skin cancer and who would prefer painless treatment with eBX, which allows for the appropriate use of such a controversial therapy.

Acknowledgments—I would like to thank Janellen Smith, MD (Irvine, California), Joshua Spanogle, MD (Saint Augustine, Florida), and Jordan V. Wang, MBE (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for their constructive comments.

The introduction of high-density radiation electronic brachytherapy (eBX) for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers has induced great angst within the dermatology community.1 The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 0182T (high dose rate eBX) reimburses at an extraordinarily high rate, which has drawn a substantial amount of attention. Some critics see it as another case of overutilization, of sucking more money out of a bleeding Medicare system. The financial opportunity afforded by eBX has even led some entrepreneurs to purchase dermatology clinics so that skin cancer patients can be treated via this modality instead of more traditional and less costly techniques (personal communication, 2014).

Among radiation oncologists, high-density radiation eBX is considered to be an important treatment option for select patients who have skin cancers staged as T1 or T2 tumors that are 4 cm or smaller in diameter and 5 mm or less in depth.2 Additionally, ideal candidates for nonsurgical treatment options such as eBX include patients with lesions in cosmetically challenging areas (eg, ears, nose), those who may experience problematic wound healing due to tumor location (eg, lower extremities) or medical conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease), those with medical comorbidities that may preclude them from surgery, those currently taking anticoagulants, and those who are not interested in undergoing surgery.

A common criticism of eBX is that there is little data on long-term treatment outcomes, which will soon be addressed by a 5-year multicenter, prospective, randomized study of 720 patients with basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma led by the University of California, Irvine, and the University of California, San Diego (study protocol currently with institutional review board). Another criticism is that some manufacturers of eBX devices gained the less rigorous US Food and Drug Administration Premarket Notification 510(k) certification; however, this certification is quite commonplace in the United States, and an examination of the data actually shows a lower recall rate with this method when compared to the longer premarket approval application process.3 A more important criticism of eBX might be that radiation therapy is associated with a substantial increase in skin cancers that may occur decades later in irradiated areas; however, there remains a paucity of studies examining the safety data on eBX during the posttreatment period when such effects would be expected.

In practice, the forces for good and evil are not only limited to those who utilize eBX. It is widely known that CPT codes for Mohs micrographic surgery also have been abused—that is, the procedure has been used in circumstances where it was not absolutely necessary4—which led to an effort by dermatologic surgery organizations to agree on appropriate use criteria for Mohs surgery.5 These criteria are not perfect but should help curb the misuse of a valuable technique, which is one that is recognized as being optimal for the treatment of complex skin cancers. One might suggest forming similar appropriate use criteria for eBX and limiting this treatment to patients who either are older than 65 years, have serious medical issues, are currently taking anticoagulants, are immobile, or simply cannot handle further dermatologic surgeries.

The American Medical Association has developed new Category III CPT codes for treatment of the skin with eBX that will become effective January 2016.6 These codes take into consideration the need for a radiation oncologist and a physicist to be present for planning, dosimetry, simulation, and selection of parameters for the appropriate depth. Although I do not know the reimbursement rates for these new codes yet, they will likely be substantially less than the current payment for treatment with eBX. That said, the gravy train has left the station, and those who have invested in the devices for eBX will either see the benefit of continued treatment for their patients or divest themselves of eBX now that the reimbursement will be more modest.

Some of my dermatology colleagues, who also are some of my very good friends, have a visceral and absolute objection to the use of any form of radiation therapy, and I respect their opinions. However, eBX does play a role in treating cutaneous malignancies, and our radiation oncology colleagues—many who treat patients with extensive, aggressive, and recurrent skin cancers—also have a place at the table.

Speaking as a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon and a department chair, I am very aware that the teaching we provide today for our dermatology residents and fellows is likely to be their modus operandi for the future, a future in which the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will force physicians to carefully choose quality of care over personal gain and where financial rewards will be based on appropriate utilization and measurable outcomes. Electronic brachytherapy is one tool amongst many. I have a plethora of patients in their 70s and 80s who have given up on surgery for skin cancer and who would prefer painless treatment with eBX, which allows for the appropriate use of such a controversial therapy.

Acknowledgments—I would like to thank Janellen Smith, MD (Irvine, California), Joshua Spanogle, MD (Saint Augustine, Florida), and Jordan V. Wang, MBE (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for their constructive comments.

1. Linos E, VanBeek M, Resneck JS Jr. A sudden and concerning increase in the use of electronic brachytherapy for skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:699-700.

2. Bhatnagar A. Nonmelanoma skin cancer treated with electronic brachytherapy: results at 1 year [published online ahead of print January 9, 2013]. Brachytherapy. 2013;12:134-140.

3. Connor JT, Lewis RJ, Berry DA, et al. FDA recalls not as alarming as they seem. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1044-1046.

4. Goldman G. Mohs surgery comes under the microscope. Member to Member American Academy of Dermatology E-newsletter. https://www.aad.org/members/publications /member-to-member/2013-archive/november-8-2013 /mohs-surgery-comes-under-the-microscope. Published November 8, 2013. Accessed August 10, 2015.

5. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery [published online ahead of print September 5, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

6. ACR Radiology Coding Source: CPT 2016 anticipated code changes. American College of Radiology Web site. http://www.acr.org/Advocacy/Economics-Health-Policy /Billing-Coding/Coding-Source-List/2015/Mar-Apr-2015 /CPT-2016-Anticipated-Code-Changes. Published March 2015. Accessed August 21, 2015.

1. Linos E, VanBeek M, Resneck JS Jr. A sudden and concerning increase in the use of electronic brachytherapy for skin cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:699-700.

2. Bhatnagar A. Nonmelanoma skin cancer treated with electronic brachytherapy: results at 1 year [published online ahead of print January 9, 2013]. Brachytherapy. 2013;12:134-140.

3. Connor JT, Lewis RJ, Berry DA, et al. FDA recalls not as alarming as they seem. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1044-1046.

4. Goldman G. Mohs surgery comes under the microscope. Member to Member American Academy of Dermatology E-newsletter. https://www.aad.org/members/publications /member-to-member/2013-archive/november-8-2013 /mohs-surgery-comes-under-the-microscope. Published November 8, 2013. Accessed August 10, 2015.

5. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery [published online ahead of print September 5, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

6. ACR Radiology Coding Source: CPT 2016 anticipated code changes. American College of Radiology Web site. http://www.acr.org/Advocacy/Economics-Health-Policy /Billing-Coding/Coding-Source-List/2015/Mar-Apr-2015 /CPT-2016-Anticipated-Code-Changes. Published March 2015. Accessed August 21, 2015.