User login

Retrograde Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator Technique for Autologous Bone Graft Harvesting With the Patient in the Prone Position

The Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator (RIA) system (Synthes, West Chester, Pennsylvania) has become a powerful tool for harvesting autologous bone graft from the intramedullary canal of the long bones of the lower extremity for the treatment of osseous defects, nonunions, and joint fusions.1,2 The RIA system provides satisfactory quality and quantity of bone graft (range, 40-90 mL)3-5 with osteogenic properties that rival those harvested from the iliac crest.6,7 Minimal donor-site morbidity and mortality have been reported in association with the RIA technique compared with iliac crest bone graft harvest.8

The RIA technique for the femur—with the antegrade approach and the supine position,8 with the antegrade approach and the prone position,9 and with the retrograde approach and the supine position4—has been described in the literature. To our knowledge, however, the RIA technique for the femur with the retrograde approach and the prone position has not been described. Antegrade harvesting uses the trochanteric entry point, and retrograde harvesting uses an entry at the intercondylar notch just anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament. In this article, we detail the technique for RIA harvesting of the femur with the patient in the prone position. Patient positioning is based on the diagnosis and the proposed procedure.

Advantages of a retrograde starting point include a more concentric trajectory (vs that of an antegrade starting point) and more efficient canal pressure reduction, which might decrease the risk of intraoperative fat embolization.10 This technique offers a more efficient solution to any procedure that requires the prone position, and it avoids the need to reposition, reprepare, or redrape the extremity. It is also very useful in treating obese patients.

After obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval, we retrospectively reviewed patient files. Because the study was retrospective, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent. The patients described here provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Surgical Technique

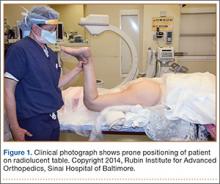

The patient is placed in a prone position on a radiolucent table with a bump under the thigh to allow access to the knee joint with full extension of the hip (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). The knee is then flexed to gain access to the intercondylar notch.

The anatomical axis of the femur is identified in the coronal and sagittal planes with the help of an image intensifier. Frequent intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging is required to prevent eccentric reaming and guide-wire movement from causing iatrogenic fractures and perforations, respectively.8 A 2-mm Steinmann pin is used to identify the point of entry into the femoral canal, which is located just above the posterior cruciate ligament insertion in the intercondylar notch, and care is taken not to ream this structure. A minimally invasive incision of about 15 mm is centered on this pin using a patellar tendon–splitting approach.

An 8-mm cannulated anterior cruciate ligament reamer is passed over the pin to enlarge the opening at the entry point, and a 2.5-mm ball-tipped guide wire is positioned in the femur. The image intensifier is used to confirm positioning of the guide in the trochanteric region and centered in the intramedullary canal. A radiolucent diving board facilitates fluoroscopic imaging.

The diameter (12.5 or 16.5 mm) of the reaming head is selected after the intramedullary guide is placed in the femoral canal. The isthmus of the femur is then identified radiographically, and a radiopaque ruler with increments in millimeters is used to measure the canal diameter (Figures 3A, 3B). Because the femoral canal is an ellipsoid, the canal diameter usually is much larger anteroposteriorly than laterally.8 We prefer to use a reaming head that overlaps the inner cortical diameter by 1 mm on each side. An alternative method includes measuring the outer diameter of the narrowest portion of the bone and using a reamer head no more than 45% of the outer diameter at the isthmus.8

The RIA system is prepared on the back table by attaching the reaming head to the irrigation and suction systems. As the reamer head enters the intramedullary canal, an approach–withdraw–pause technique is used to slowly advance the reamer through the femur. It is crucial to use the image intensifier to guide reaming in order to avoid overdrilling the anterior cortex and prevent eccentric reaming of the canal, which more commonly occurs in patients with large anterior femoral bows.11 When the collection filter becomes full, reaming is stopped. The bone graft in the filter is emptied into a specimen cup for measurement and storage until subsequent use (Figure 4). Suctioning is suspended when reaming is stopped because substantial blood loss can occur with prolonged suction and aspiration.12 When repeat reaming is required, care is taken not to overream the cortices, thereby avoiding the risk of iatrogenic fracture.10,12

The knee joint is irrigated to remove any intramedullary debris. Typically there is no debris, as it is captured by the RIA. The wound is closed in 2 layers. Dressing with Ace bandage (3M, St. Paul, Minnesota) is placed around the knee for comfort. Weight-bearing status is determined by the index procedure.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 68-year-old female smoker presented to our facility with right ankle pain after recent ankle arthrodesis for pilon fracture nonunion. Almost 3 years earlier, the patient sustained a Gustilo-Anderson type II open pilon fracture in a motorcycle accident. She underwent antibiotic therapy, irrigation and débridement of the fracture site, and external fixation before definitive treatment with repeat irrigation and débridement and open reduction and internal fixation of the tibial plafond. About 6 months after surgery, she presented to her surgeon with a draining abscess over the anteromedial surgical incision. Multiple débridement procedures were performed, the implant was removed, the ankle was stabilized with a bridging external fixator, and culture-specific antibiotic therapy was administered. Intraoperative cultures confirmed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Vancomycin was administered intravenously for 6 weeks. Once C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate returned to normal, repeat débridement with a rectus abdominis free flap and ankle fusion were performed.

When the patient presented to our clinic, we saw atrophic nonunion of the ankle fusion on radiographs. Smoking cessation was encouraged but not required before surgery. The patient returned to the operating suite for tibiotalocalcaneal fusion with a retrograde intramedullary nail. With the patient in the prone position, retrograde femoral RIA reaming was performed to harvest 30 mL of autologous bone. After resection of the nonunion site using a trans-Achilles approach and insertion of the intramedullary nail, the autologous bone graft was mixed with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), and the mixture was introduced into the fusion site. At final follow-up, 18 months after surgery, the patient was clinically asymptomatic and radiographically healed—without further intervention and despite continued smoking. She did not report any knee pain from the harvest site.

Case 2

A 59-year-old noncompliant woman with diabetes and Charcot neuropathy sustained a trimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation that was initially treated with ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis. The postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged home. Less than a week later, she presented to the emergency department with a midshaft tibial fracture just proximal to the ankle and hindfoot fusion nail. She subsequently had the device removed and a long arthrodesis rod inserted to span the fracture site up to the proximal tibial metadiaphysis. About 9 months later, she returned to our office complaining of ankle pain. No signs of infection were clinically evident. Radiographs showed nonunion of the ankle and subtalar joint. Findings of the initial bone biopsy and pathologic examination were negative for infection. The patient returned to the operating room 4 weeks later for revision ankle fusion. With the patient in the prone position, autologous bone (~30 mL) was harvested using retrograde femoral RIA reaming. The nonunion site was resected, and a mixture of autologous bone graft and BMP-2 was applied. Through a posterior approach, an anterior ankle arthrodesis locking plate was applied to the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and tibia. The patient was kept non-weight-bearing for 3 months and progressed in weight-bearing for another 4 to 6 weeks. Ambulatory status was restored about 4 months after surgery. No harvest-site knee pain was reported.

Discussion

Given its osteogenic, osteoconductive, and osteoinductive properties, autologous cancellous bone graft is the gold standard for reconstruction and fusion procedures in foot and ankle surgery.13 Bone graft can be obtained from many potential donor sites, but the most common is the iliac crest.2 However, many comorbidities, such as residual donor-site pain, neurovascular injuries, infection, and increased surgical time, have been reported in the literature.14,15 The RIA system was initially developed for simultaneous reaming and aspiration to reduce intramedullary pressure, heat generation, operating time, and the systemic effects of reaming, such as the embolic phenomenon.16-22 The single-pass reamer has provided a minimally invasive strategy for procuring voluminous amounts of autologous cancellous bone from the intramedullary canal of lower extremity long bones. Schmidmaier and colleagues3 recently quantified the measurements of several growth factors, such as insulinlike growth factor 1, transforming growth factor β 1, and BMP-2—proving that RIA-derived aspirates have amounts comparable to if not larger than those of iliac crest autologous bone graft. Pratt and colleagues23 provided insight into the possibility of induction of mesenchymal stem cells using the previously unwanted supernatant reamings after filtration. Recently, the RIA technique of autologous tibial and hindfoot bone graft harvest was described for use in ankle or tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis.2 Although this technique is a useful surgical option, tibia size remains a limiting factor. Kovar and Wozasek24 reported harvesting significantly more bone graft in the femur than in the tibia. A tibia that cannot accommodate the 12-mm (smallest) reamer head in the RIA system would be a contraindication. In addition, concerns about the association between tibial stress fractures and reaming of the entire tibial canal and concerns about the overall donor-site morbidity of the tibial shaft remain.

Conclusion

With its retrograde approach and prone positioning, this RIA technique is an effective and efficient solution for harvesting autologous femoral bone graft. Although we have described its use in ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis, this technique can be applied to any prone-position surgical procedure, including spine surgery.

1. Kobbe P, Tarkin IS, Frink M, Pape HC. Voluminous bone graft harvesting of the femoral marrow cavity for autologous transplantation. An indication for the “reamer-irrigator-aspirator-” (RIA-)technique [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111(6):469-472.

2. Herscovici D Jr, Scaduto JM. Use of the reamer-irrigator-aspirator technique to obtain autograft for ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):75-79.

3. Schmidmaier G, Herrmann S, Green J, et al. Quantitative assessment of growth factors in reaming aspirate, iliac crest, and platelet preparation. Bone. 2006;39(5):1156-1163.

4. Qvick LM, Ritter CA, Mutty CE, Rohrbacher BJ, Buyea CM, Anders MJ. Donor site morbidity with reamer-irrigator-aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury. 2013;44(10):1263-1269.

5. Lehman AA, Irgit KS, Cush GJ. Harvest of autogenous bone graft using reamer-irrigator-aspirator in tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis: surgical technique and case series. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(12):1133-1138.

6. Wildemann B, Kadow-Romacker A, Haas NP, Schmidmaier G. Quantification of various growth factors in different demineralized bone matrix preparations. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81(2):437-442.

7. Sagi HC, Young ML, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn TA, Tornetta P. Qualitative and quantitative differences between bone graft obtained from the medullary canal (with a reamer/irrigator/aspirator) and the iliac crest of the same patient. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2128-2135.

8. Belthur MV, Conway JD, Jindal G, Ranade A, Herzenberg JE. Bone graft harvest using a new intramedullary system. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(12):2973-2980.

9. Nichols TA, Sagi HC, Weber TG, Guiot BH. An alternative source of autograft bone for spinal fusion: the femur: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3 suppl 1):E179.

10. Van Gorp CC, Falk JV, Kmiec SJ Jr, Siston RA. The reamer/irrigator/aspirator reduces femoral canal pressure in simulated TKA. Clin Orthop. 2009;467(3):805-809.

11. Quintero AJ, Tarkin IS, Pape HC. Technical tricks when using the reamer irrigator aspirator technique for autologous bone graft harvesting. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):42-45.

12. Stafford PR, Norris B. Reamer-irrigator-aspirator as a bone graft harvester. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;6(2):100-107.

13. Whitehouse MR, Lankester BJ, Winson IG, Hepple S. Bone graft harvest from the proximal tibia in foot and ankle arthrodesis surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(11):913-916.

14. Scharfenberger A, Weber T. RIA for bone graft harvest: applications for grafting large segmental defects in the tibia and femur. Presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association; 2005; Ottawa, Canada.

15. Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop. 1996;(329):300-309.

16. Bedi A, Karunakar MA. Physiologic effects of intramedullary reaming. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:359-366.

17. Higgins TF, Casey V, Bachus K. Cortical heat generation using an irrigating/aspirating single-pass reaming vs conventional stepwise reaming. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(3):192-197.

18. Husebye EE, Lyberg T, Madsen JE, Eriksen M, Røise O. The influence of a one-step reamer-irrigator-aspirator technique on the intramedullary pressure in the pig femur. Injury. 2006;37(10):935-940.

19. Müller CA, Green J, Südkamp NP. Physical and technical aspects of intramedullary reaming. Injury. 2006;37(suppl 4):S39-S49.

20. Pape HC, Dwenger A, Grotz M, et al. Does the reamer type influence the degree of lung dysfunction after femoral nailing following severe trauma? An animal study. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(4):300-309.

21. Pape HC, Zelle BA, Hildebrand F, Giannoudis PV, Krettek C, van Griensven M. Reamed femoral nailing in sheep: does irrigation and aspiration of intramedullary contents alter the systemic response? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(11):2515-2522.

22. Schult M, Küchle R, Hofmann A, et al. Pathophysiological advantages of rinsing-suction-reaming (RSR) in a pig model for intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(6):1186-1192.

23. Pratt DJ, Papagiannopoulos G, Rees PH, Quinnell R. The effects of medullary reaming on the torsional strength of the femur. Injury. 1987;18(3):177-179.

24. Kovar FM, Wozasek GE. Bone graft harvesting using the RIA (reamer irrigation aspirator) system—a quantitative assessment. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011;123(9-10):285-290.

The Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator (RIA) system (Synthes, West Chester, Pennsylvania) has become a powerful tool for harvesting autologous bone graft from the intramedullary canal of the long bones of the lower extremity for the treatment of osseous defects, nonunions, and joint fusions.1,2 The RIA system provides satisfactory quality and quantity of bone graft (range, 40-90 mL)3-5 with osteogenic properties that rival those harvested from the iliac crest.6,7 Minimal donor-site morbidity and mortality have been reported in association with the RIA technique compared with iliac crest bone graft harvest.8

The RIA technique for the femur—with the antegrade approach and the supine position,8 with the antegrade approach and the prone position,9 and with the retrograde approach and the supine position4—has been described in the literature. To our knowledge, however, the RIA technique for the femur with the retrograde approach and the prone position has not been described. Antegrade harvesting uses the trochanteric entry point, and retrograde harvesting uses an entry at the intercondylar notch just anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament. In this article, we detail the technique for RIA harvesting of the femur with the patient in the prone position. Patient positioning is based on the diagnosis and the proposed procedure.

Advantages of a retrograde starting point include a more concentric trajectory (vs that of an antegrade starting point) and more efficient canal pressure reduction, which might decrease the risk of intraoperative fat embolization.10 This technique offers a more efficient solution to any procedure that requires the prone position, and it avoids the need to reposition, reprepare, or redrape the extremity. It is also very useful in treating obese patients.

After obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval, we retrospectively reviewed patient files. Because the study was retrospective, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent. The patients described here provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed in a prone position on a radiolucent table with a bump under the thigh to allow access to the knee joint with full extension of the hip (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). The knee is then flexed to gain access to the intercondylar notch.

The anatomical axis of the femur is identified in the coronal and sagittal planes with the help of an image intensifier. Frequent intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging is required to prevent eccentric reaming and guide-wire movement from causing iatrogenic fractures and perforations, respectively.8 A 2-mm Steinmann pin is used to identify the point of entry into the femoral canal, which is located just above the posterior cruciate ligament insertion in the intercondylar notch, and care is taken not to ream this structure. A minimally invasive incision of about 15 mm is centered on this pin using a patellar tendon–splitting approach.

An 8-mm cannulated anterior cruciate ligament reamer is passed over the pin to enlarge the opening at the entry point, and a 2.5-mm ball-tipped guide wire is positioned in the femur. The image intensifier is used to confirm positioning of the guide in the trochanteric region and centered in the intramedullary canal. A radiolucent diving board facilitates fluoroscopic imaging.

The diameter (12.5 or 16.5 mm) of the reaming head is selected after the intramedullary guide is placed in the femoral canal. The isthmus of the femur is then identified radiographically, and a radiopaque ruler with increments in millimeters is used to measure the canal diameter (Figures 3A, 3B). Because the femoral canal is an ellipsoid, the canal diameter usually is much larger anteroposteriorly than laterally.8 We prefer to use a reaming head that overlaps the inner cortical diameter by 1 mm on each side. An alternative method includes measuring the outer diameter of the narrowest portion of the bone and using a reamer head no more than 45% of the outer diameter at the isthmus.8

The RIA system is prepared on the back table by attaching the reaming head to the irrigation and suction systems. As the reamer head enters the intramedullary canal, an approach–withdraw–pause technique is used to slowly advance the reamer through the femur. It is crucial to use the image intensifier to guide reaming in order to avoid overdrilling the anterior cortex and prevent eccentric reaming of the canal, which more commonly occurs in patients with large anterior femoral bows.11 When the collection filter becomes full, reaming is stopped. The bone graft in the filter is emptied into a specimen cup for measurement and storage until subsequent use (Figure 4). Suctioning is suspended when reaming is stopped because substantial blood loss can occur with prolonged suction and aspiration.12 When repeat reaming is required, care is taken not to overream the cortices, thereby avoiding the risk of iatrogenic fracture.10,12

The knee joint is irrigated to remove any intramedullary debris. Typically there is no debris, as it is captured by the RIA. The wound is closed in 2 layers. Dressing with Ace bandage (3M, St. Paul, Minnesota) is placed around the knee for comfort. Weight-bearing status is determined by the index procedure.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 68-year-old female smoker presented to our facility with right ankle pain after recent ankle arthrodesis for pilon fracture nonunion. Almost 3 years earlier, the patient sustained a Gustilo-Anderson type II open pilon fracture in a motorcycle accident. She underwent antibiotic therapy, irrigation and débridement of the fracture site, and external fixation before definitive treatment with repeat irrigation and débridement and open reduction and internal fixation of the tibial plafond. About 6 months after surgery, she presented to her surgeon with a draining abscess over the anteromedial surgical incision. Multiple débridement procedures were performed, the implant was removed, the ankle was stabilized with a bridging external fixator, and culture-specific antibiotic therapy was administered. Intraoperative cultures confirmed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Vancomycin was administered intravenously for 6 weeks. Once C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate returned to normal, repeat débridement with a rectus abdominis free flap and ankle fusion were performed.

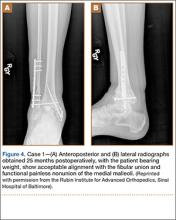

When the patient presented to our clinic, we saw atrophic nonunion of the ankle fusion on radiographs. Smoking cessation was encouraged but not required before surgery. The patient returned to the operating suite for tibiotalocalcaneal fusion with a retrograde intramedullary nail. With the patient in the prone position, retrograde femoral RIA reaming was performed to harvest 30 mL of autologous bone. After resection of the nonunion site using a trans-Achilles approach and insertion of the intramedullary nail, the autologous bone graft was mixed with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), and the mixture was introduced into the fusion site. At final follow-up, 18 months after surgery, the patient was clinically asymptomatic and radiographically healed—without further intervention and despite continued smoking. She did not report any knee pain from the harvest site.

Case 2

A 59-year-old noncompliant woman with diabetes and Charcot neuropathy sustained a trimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation that was initially treated with ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis. The postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged home. Less than a week later, she presented to the emergency department with a midshaft tibial fracture just proximal to the ankle and hindfoot fusion nail. She subsequently had the device removed and a long arthrodesis rod inserted to span the fracture site up to the proximal tibial metadiaphysis. About 9 months later, she returned to our office complaining of ankle pain. No signs of infection were clinically evident. Radiographs showed nonunion of the ankle and subtalar joint. Findings of the initial bone biopsy and pathologic examination were negative for infection. The patient returned to the operating room 4 weeks later for revision ankle fusion. With the patient in the prone position, autologous bone (~30 mL) was harvested using retrograde femoral RIA reaming. The nonunion site was resected, and a mixture of autologous bone graft and BMP-2 was applied. Through a posterior approach, an anterior ankle arthrodesis locking plate was applied to the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and tibia. The patient was kept non-weight-bearing for 3 months and progressed in weight-bearing for another 4 to 6 weeks. Ambulatory status was restored about 4 months after surgery. No harvest-site knee pain was reported.

Discussion

Given its osteogenic, osteoconductive, and osteoinductive properties, autologous cancellous bone graft is the gold standard for reconstruction and fusion procedures in foot and ankle surgery.13 Bone graft can be obtained from many potential donor sites, but the most common is the iliac crest.2 However, many comorbidities, such as residual donor-site pain, neurovascular injuries, infection, and increased surgical time, have been reported in the literature.14,15 The RIA system was initially developed for simultaneous reaming and aspiration to reduce intramedullary pressure, heat generation, operating time, and the systemic effects of reaming, such as the embolic phenomenon.16-22 The single-pass reamer has provided a minimally invasive strategy for procuring voluminous amounts of autologous cancellous bone from the intramedullary canal of lower extremity long bones. Schmidmaier and colleagues3 recently quantified the measurements of several growth factors, such as insulinlike growth factor 1, transforming growth factor β 1, and BMP-2—proving that RIA-derived aspirates have amounts comparable to if not larger than those of iliac crest autologous bone graft. Pratt and colleagues23 provided insight into the possibility of induction of mesenchymal stem cells using the previously unwanted supernatant reamings after filtration. Recently, the RIA technique of autologous tibial and hindfoot bone graft harvest was described for use in ankle or tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis.2 Although this technique is a useful surgical option, tibia size remains a limiting factor. Kovar and Wozasek24 reported harvesting significantly more bone graft in the femur than in the tibia. A tibia that cannot accommodate the 12-mm (smallest) reamer head in the RIA system would be a contraindication. In addition, concerns about the association between tibial stress fractures and reaming of the entire tibial canal and concerns about the overall donor-site morbidity of the tibial shaft remain.

Conclusion

With its retrograde approach and prone positioning, this RIA technique is an effective and efficient solution for harvesting autologous femoral bone graft. Although we have described its use in ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis, this technique can be applied to any prone-position surgical procedure, including spine surgery.

The Reamer/Irrigator/Aspirator (RIA) system (Synthes, West Chester, Pennsylvania) has become a powerful tool for harvesting autologous bone graft from the intramedullary canal of the long bones of the lower extremity for the treatment of osseous defects, nonunions, and joint fusions.1,2 The RIA system provides satisfactory quality and quantity of bone graft (range, 40-90 mL)3-5 with osteogenic properties that rival those harvested from the iliac crest.6,7 Minimal donor-site morbidity and mortality have been reported in association with the RIA technique compared with iliac crest bone graft harvest.8

The RIA technique for the femur—with the antegrade approach and the supine position,8 with the antegrade approach and the prone position,9 and with the retrograde approach and the supine position4—has been described in the literature. To our knowledge, however, the RIA technique for the femur with the retrograde approach and the prone position has not been described. Antegrade harvesting uses the trochanteric entry point, and retrograde harvesting uses an entry at the intercondylar notch just anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament. In this article, we detail the technique for RIA harvesting of the femur with the patient in the prone position. Patient positioning is based on the diagnosis and the proposed procedure.

Advantages of a retrograde starting point include a more concentric trajectory (vs that of an antegrade starting point) and more efficient canal pressure reduction, which might decrease the risk of intraoperative fat embolization.10 This technique offers a more efficient solution to any procedure that requires the prone position, and it avoids the need to reposition, reprepare, or redrape the extremity. It is also very useful in treating obese patients.

After obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval, we retrospectively reviewed patient files. Because the study was retrospective, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent. The patients described here provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed in a prone position on a radiolucent table with a bump under the thigh to allow access to the knee joint with full extension of the hip (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). The knee is then flexed to gain access to the intercondylar notch.

The anatomical axis of the femur is identified in the coronal and sagittal planes with the help of an image intensifier. Frequent intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging is required to prevent eccentric reaming and guide-wire movement from causing iatrogenic fractures and perforations, respectively.8 A 2-mm Steinmann pin is used to identify the point of entry into the femoral canal, which is located just above the posterior cruciate ligament insertion in the intercondylar notch, and care is taken not to ream this structure. A minimally invasive incision of about 15 mm is centered on this pin using a patellar tendon–splitting approach.

An 8-mm cannulated anterior cruciate ligament reamer is passed over the pin to enlarge the opening at the entry point, and a 2.5-mm ball-tipped guide wire is positioned in the femur. The image intensifier is used to confirm positioning of the guide in the trochanteric region and centered in the intramedullary canal. A radiolucent diving board facilitates fluoroscopic imaging.

The diameter (12.5 or 16.5 mm) of the reaming head is selected after the intramedullary guide is placed in the femoral canal. The isthmus of the femur is then identified radiographically, and a radiopaque ruler with increments in millimeters is used to measure the canal diameter (Figures 3A, 3B). Because the femoral canal is an ellipsoid, the canal diameter usually is much larger anteroposteriorly than laterally.8 We prefer to use a reaming head that overlaps the inner cortical diameter by 1 mm on each side. An alternative method includes measuring the outer diameter of the narrowest portion of the bone and using a reamer head no more than 45% of the outer diameter at the isthmus.8

The RIA system is prepared on the back table by attaching the reaming head to the irrigation and suction systems. As the reamer head enters the intramedullary canal, an approach–withdraw–pause technique is used to slowly advance the reamer through the femur. It is crucial to use the image intensifier to guide reaming in order to avoid overdrilling the anterior cortex and prevent eccentric reaming of the canal, which more commonly occurs in patients with large anterior femoral bows.11 When the collection filter becomes full, reaming is stopped. The bone graft in the filter is emptied into a specimen cup for measurement and storage until subsequent use (Figure 4). Suctioning is suspended when reaming is stopped because substantial blood loss can occur with prolonged suction and aspiration.12 When repeat reaming is required, care is taken not to overream the cortices, thereby avoiding the risk of iatrogenic fracture.10,12

The knee joint is irrigated to remove any intramedullary debris. Typically there is no debris, as it is captured by the RIA. The wound is closed in 2 layers. Dressing with Ace bandage (3M, St. Paul, Minnesota) is placed around the knee for comfort. Weight-bearing status is determined by the index procedure.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 68-year-old female smoker presented to our facility with right ankle pain after recent ankle arthrodesis for pilon fracture nonunion. Almost 3 years earlier, the patient sustained a Gustilo-Anderson type II open pilon fracture in a motorcycle accident. She underwent antibiotic therapy, irrigation and débridement of the fracture site, and external fixation before definitive treatment with repeat irrigation and débridement and open reduction and internal fixation of the tibial plafond. About 6 months after surgery, she presented to her surgeon with a draining abscess over the anteromedial surgical incision. Multiple débridement procedures were performed, the implant was removed, the ankle was stabilized with a bridging external fixator, and culture-specific antibiotic therapy was administered. Intraoperative cultures confirmed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Vancomycin was administered intravenously for 6 weeks. Once C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate returned to normal, repeat débridement with a rectus abdominis free flap and ankle fusion were performed.

When the patient presented to our clinic, we saw atrophic nonunion of the ankle fusion on radiographs. Smoking cessation was encouraged but not required before surgery. The patient returned to the operating suite for tibiotalocalcaneal fusion with a retrograde intramedullary nail. With the patient in the prone position, retrograde femoral RIA reaming was performed to harvest 30 mL of autologous bone. After resection of the nonunion site using a trans-Achilles approach and insertion of the intramedullary nail, the autologous bone graft was mixed with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), and the mixture was introduced into the fusion site. At final follow-up, 18 months after surgery, the patient was clinically asymptomatic and radiographically healed—without further intervention and despite continued smoking. She did not report any knee pain from the harvest site.

Case 2

A 59-year-old noncompliant woman with diabetes and Charcot neuropathy sustained a trimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation that was initially treated with ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis. The postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged home. Less than a week later, she presented to the emergency department with a midshaft tibial fracture just proximal to the ankle and hindfoot fusion nail. She subsequently had the device removed and a long arthrodesis rod inserted to span the fracture site up to the proximal tibial metadiaphysis. About 9 months later, she returned to our office complaining of ankle pain. No signs of infection were clinically evident. Radiographs showed nonunion of the ankle and subtalar joint. Findings of the initial bone biopsy and pathologic examination were negative for infection. The patient returned to the operating room 4 weeks later for revision ankle fusion. With the patient in the prone position, autologous bone (~30 mL) was harvested using retrograde femoral RIA reaming. The nonunion site was resected, and a mixture of autologous bone graft and BMP-2 was applied. Through a posterior approach, an anterior ankle arthrodesis locking plate was applied to the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and tibia. The patient was kept non-weight-bearing for 3 months and progressed in weight-bearing for another 4 to 6 weeks. Ambulatory status was restored about 4 months after surgery. No harvest-site knee pain was reported.

Discussion

Given its osteogenic, osteoconductive, and osteoinductive properties, autologous cancellous bone graft is the gold standard for reconstruction and fusion procedures in foot and ankle surgery.13 Bone graft can be obtained from many potential donor sites, but the most common is the iliac crest.2 However, many comorbidities, such as residual donor-site pain, neurovascular injuries, infection, and increased surgical time, have been reported in the literature.14,15 The RIA system was initially developed for simultaneous reaming and aspiration to reduce intramedullary pressure, heat generation, operating time, and the systemic effects of reaming, such as the embolic phenomenon.16-22 The single-pass reamer has provided a minimally invasive strategy for procuring voluminous amounts of autologous cancellous bone from the intramedullary canal of lower extremity long bones. Schmidmaier and colleagues3 recently quantified the measurements of several growth factors, such as insulinlike growth factor 1, transforming growth factor β 1, and BMP-2—proving that RIA-derived aspirates have amounts comparable to if not larger than those of iliac crest autologous bone graft. Pratt and colleagues23 provided insight into the possibility of induction of mesenchymal stem cells using the previously unwanted supernatant reamings after filtration. Recently, the RIA technique of autologous tibial and hindfoot bone graft harvest was described for use in ankle or tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis.2 Although this technique is a useful surgical option, tibia size remains a limiting factor. Kovar and Wozasek24 reported harvesting significantly more bone graft in the femur than in the tibia. A tibia that cannot accommodate the 12-mm (smallest) reamer head in the RIA system would be a contraindication. In addition, concerns about the association between tibial stress fractures and reaming of the entire tibial canal and concerns about the overall donor-site morbidity of the tibial shaft remain.

Conclusion

With its retrograde approach and prone positioning, this RIA technique is an effective and efficient solution for harvesting autologous femoral bone graft. Although we have described its use in ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis, this technique can be applied to any prone-position surgical procedure, including spine surgery.

1. Kobbe P, Tarkin IS, Frink M, Pape HC. Voluminous bone graft harvesting of the femoral marrow cavity for autologous transplantation. An indication for the “reamer-irrigator-aspirator-” (RIA-)technique [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111(6):469-472.

2. Herscovici D Jr, Scaduto JM. Use of the reamer-irrigator-aspirator technique to obtain autograft for ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):75-79.

3. Schmidmaier G, Herrmann S, Green J, et al. Quantitative assessment of growth factors in reaming aspirate, iliac crest, and platelet preparation. Bone. 2006;39(5):1156-1163.

4. Qvick LM, Ritter CA, Mutty CE, Rohrbacher BJ, Buyea CM, Anders MJ. Donor site morbidity with reamer-irrigator-aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury. 2013;44(10):1263-1269.

5. Lehman AA, Irgit KS, Cush GJ. Harvest of autogenous bone graft using reamer-irrigator-aspirator in tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis: surgical technique and case series. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(12):1133-1138.

6. Wildemann B, Kadow-Romacker A, Haas NP, Schmidmaier G. Quantification of various growth factors in different demineralized bone matrix preparations. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81(2):437-442.

7. Sagi HC, Young ML, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn TA, Tornetta P. Qualitative and quantitative differences between bone graft obtained from the medullary canal (with a reamer/irrigator/aspirator) and the iliac crest of the same patient. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2128-2135.

8. Belthur MV, Conway JD, Jindal G, Ranade A, Herzenberg JE. Bone graft harvest using a new intramedullary system. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(12):2973-2980.

9. Nichols TA, Sagi HC, Weber TG, Guiot BH. An alternative source of autograft bone for spinal fusion: the femur: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3 suppl 1):E179.

10. Van Gorp CC, Falk JV, Kmiec SJ Jr, Siston RA. The reamer/irrigator/aspirator reduces femoral canal pressure in simulated TKA. Clin Orthop. 2009;467(3):805-809.

11. Quintero AJ, Tarkin IS, Pape HC. Technical tricks when using the reamer irrigator aspirator technique for autologous bone graft harvesting. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):42-45.

12. Stafford PR, Norris B. Reamer-irrigator-aspirator as a bone graft harvester. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;6(2):100-107.

13. Whitehouse MR, Lankester BJ, Winson IG, Hepple S. Bone graft harvest from the proximal tibia in foot and ankle arthrodesis surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(11):913-916.

14. Scharfenberger A, Weber T. RIA for bone graft harvest: applications for grafting large segmental defects in the tibia and femur. Presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association; 2005; Ottawa, Canada.

15. Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop. 1996;(329):300-309.

16. Bedi A, Karunakar MA. Physiologic effects of intramedullary reaming. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:359-366.

17. Higgins TF, Casey V, Bachus K. Cortical heat generation using an irrigating/aspirating single-pass reaming vs conventional stepwise reaming. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(3):192-197.

18. Husebye EE, Lyberg T, Madsen JE, Eriksen M, Røise O. The influence of a one-step reamer-irrigator-aspirator technique on the intramedullary pressure in the pig femur. Injury. 2006;37(10):935-940.

19. Müller CA, Green J, Südkamp NP. Physical and technical aspects of intramedullary reaming. Injury. 2006;37(suppl 4):S39-S49.

20. Pape HC, Dwenger A, Grotz M, et al. Does the reamer type influence the degree of lung dysfunction after femoral nailing following severe trauma? An animal study. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(4):300-309.

21. Pape HC, Zelle BA, Hildebrand F, Giannoudis PV, Krettek C, van Griensven M. Reamed femoral nailing in sheep: does irrigation and aspiration of intramedullary contents alter the systemic response? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(11):2515-2522.

22. Schult M, Küchle R, Hofmann A, et al. Pathophysiological advantages of rinsing-suction-reaming (RSR) in a pig model for intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(6):1186-1192.

23. Pratt DJ, Papagiannopoulos G, Rees PH, Quinnell R. The effects of medullary reaming on the torsional strength of the femur. Injury. 1987;18(3):177-179.

24. Kovar FM, Wozasek GE. Bone graft harvesting using the RIA (reamer irrigation aspirator) system—a quantitative assessment. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011;123(9-10):285-290.

1. Kobbe P, Tarkin IS, Frink M, Pape HC. Voluminous bone graft harvesting of the femoral marrow cavity for autologous transplantation. An indication for the “reamer-irrigator-aspirator-” (RIA-)technique [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111(6):469-472.

2. Herscovici D Jr, Scaduto JM. Use of the reamer-irrigator-aspirator technique to obtain autograft for ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):75-79.

3. Schmidmaier G, Herrmann S, Green J, et al. Quantitative assessment of growth factors in reaming aspirate, iliac crest, and platelet preparation. Bone. 2006;39(5):1156-1163.

4. Qvick LM, Ritter CA, Mutty CE, Rohrbacher BJ, Buyea CM, Anders MJ. Donor site morbidity with reamer-irrigator-aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury. 2013;44(10):1263-1269.

5. Lehman AA, Irgit KS, Cush GJ. Harvest of autogenous bone graft using reamer-irrigator-aspirator in tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis: surgical technique and case series. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(12):1133-1138.

6. Wildemann B, Kadow-Romacker A, Haas NP, Schmidmaier G. Quantification of various growth factors in different demineralized bone matrix preparations. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81(2):437-442.

7. Sagi HC, Young ML, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn TA, Tornetta P. Qualitative and quantitative differences between bone graft obtained from the medullary canal (with a reamer/irrigator/aspirator) and the iliac crest of the same patient. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2128-2135.

8. Belthur MV, Conway JD, Jindal G, Ranade A, Herzenberg JE. Bone graft harvest using a new intramedullary system. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(12):2973-2980.

9. Nichols TA, Sagi HC, Weber TG, Guiot BH. An alternative source of autograft bone for spinal fusion: the femur: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3 suppl 1):E179.

10. Van Gorp CC, Falk JV, Kmiec SJ Jr, Siston RA. The reamer/irrigator/aspirator reduces femoral canal pressure in simulated TKA. Clin Orthop. 2009;467(3):805-809.

11. Quintero AJ, Tarkin IS, Pape HC. Technical tricks when using the reamer irrigator aspirator technique for autologous bone graft harvesting. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):42-45.

12. Stafford PR, Norris B. Reamer-irrigator-aspirator as a bone graft harvester. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;6(2):100-107.

13. Whitehouse MR, Lankester BJ, Winson IG, Hepple S. Bone graft harvest from the proximal tibia in foot and ankle arthrodesis surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(11):913-916.

14. Scharfenberger A, Weber T. RIA for bone graft harvest: applications for grafting large segmental defects in the tibia and femur. Presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association; 2005; Ottawa, Canada.

15. Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop. 1996;(329):300-309.

16. Bedi A, Karunakar MA. Physiologic effects of intramedullary reaming. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:359-366.

17. Higgins TF, Casey V, Bachus K. Cortical heat generation using an irrigating/aspirating single-pass reaming vs conventional stepwise reaming. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(3):192-197.

18. Husebye EE, Lyberg T, Madsen JE, Eriksen M, Røise O. The influence of a one-step reamer-irrigator-aspirator technique on the intramedullary pressure in the pig femur. Injury. 2006;37(10):935-940.

19. Müller CA, Green J, Südkamp NP. Physical and technical aspects of intramedullary reaming. Injury. 2006;37(suppl 4):S39-S49.

20. Pape HC, Dwenger A, Grotz M, et al. Does the reamer type influence the degree of lung dysfunction after femoral nailing following severe trauma? An animal study. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8(4):300-309.

21. Pape HC, Zelle BA, Hildebrand F, Giannoudis PV, Krettek C, van Griensven M. Reamed femoral nailing in sheep: does irrigation and aspiration of intramedullary contents alter the systemic response? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(11):2515-2522.

22. Schult M, Küchle R, Hofmann A, et al. Pathophysiological advantages of rinsing-suction-reaming (RSR) in a pig model for intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(6):1186-1192.

23. Pratt DJ, Papagiannopoulos G, Rees PH, Quinnell R. The effects of medullary reaming on the torsional strength of the femur. Injury. 1987;18(3):177-179.

24. Kovar FM, Wozasek GE. Bone graft harvesting using the RIA (reamer irrigation aspirator) system—a quantitative assessment. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011;123(9-10):285-290.

Antibiotic Cement-Coated Plates for Management of Infected Fractures

Deep infection in the presence of an implant after open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is usually treated with removal of the implant, serial débridement procedures, lavage, intravenously administered antibiotics, and, in some cases, placement of antibiotic-impregnated beads. If infection occurs during the early stages of bone healing, stabilization of the fractures might be compromised after removal of the implant. Although antibiotic-impregnated beads offer local delivery of antibiotics, they do not provide structural support of the fracture site. The beads often are difficult to remove after in-growth of granulation tissue. In areas of subcutaneous bone, an antibiotic bead pouch might be preferred to an open wound. Published research regarding the use of antibiotic-coated plates during the acute or chronic stages of infection is scarce. Plates offer the versatility of fracture stabilization, and the addition of antibiotic cement to the plates might aid in eradication of infection without necessitating a second surgery for removal. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Technique

After removal of implants, we perform débridement of the soft tissues with a hydroscalpel (Versajet; Smith & Nephew, London, United Kingdom), mechanical débridement of bone, and curettage with high speed burr. The wound is then irrigated with pulse pressure lavage and a minimum of 3 L sterile normal saline. The extremity is re-prepped and re-draped; the entire surgical team’s gowns and gloves are changed; and new instrumentation, including cautery and suction equipment, is used. The cement is prepared with tobramycin (3.6 g) and vancomycin (1 g) per 40-g bag of cement. The plate is placed in silicon tubing, and the antibiotic-prepared cement is injected into the tubing and molded until dry. Care is taken to mold the locations of the screw holes by making incisions in the tubing at the appropriate locations. Screws are placed through the screw holes to ensure locking capability, and Kirschner wires are placed through temporary fixation holes (Figure 1). Once dry, the screws and wires are removed from the plate, and the cement-coated plate is removed from the tubing. The antibiotic-coated plate is applied to the fracture or osteotomy site and is seated with screws as appropriate (Figure 2). The wound is closed primarily. Wound drains or vacuum-assisted closure devices are not routinely used unless there is high risk for hematoma formation. The authors prefer to have high local concentrations of antibiotic in the surrounding tissues and wound.

Clinical Series

Case 1

A 31-year-old man fell from a ladder and sustained a bimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation that was treated with ORIF. Three weeks after initial injury, the patient presented with an infected lateral wound with purulent discharge. He was taken to the operating room for initial débridement, irrigation, and fracture stabilization with an antibiotic-coated plate and tension-band wiring of the medial malleoli. He was discharged from the hospital on day 4 after admission. Cultures of the wound grew beta-hemolytic strep group G and coagulase-negative staphylococci in broth that was sensitive to oxacillin, vancomycin, and gentamycin. The patient was treated with a 6-week regimen of Unasyn (Roerig, New York, New York), developed bony union, and has been free of clinical signs of infection for 2 years (Figures 3, 4).

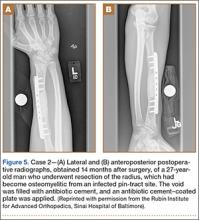

Case 2

A 27-year-old male carpenter fell from a height of 12 feet and sustained a fracture of the distal radius that was treated with external fixation. The proximal pin site became clinically infected and subsequently developed osteomyelitis. The patient had a draining wound with a fracture for 2 months. He underwent débridement with partial resection of the radius and placement of an antibiotic cement–coated plate and calcium phosphate bone-void filler impregnated with antibiotics. Pathology specimens were positive for osteomyelitis, and bone cultures showed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). He received intravenously administered antibiotic therapy for 6 weeks after surgery. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 5A, 5B).

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and venous stasis sustained a trimalleolar ankle fracture after a low-energy fall that was initially treated with ORIF. She underwent revision ORIF to treat a malunion 3 months after initial treatment. At 8 months, the patient developed a draining sinus communicating with the plate. Computed tomography revealed nonunion and indicated infection. The patient underwent resection of the osteomyelitis and repair of the fibular nonunion with an antibiotic-coated plate. Tissue cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococcus, and pathology specimens were positive for osteomyelitis. She received postoperative antibiotics intravenously and 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy after discharge from the hospital. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 6, 7).

Case 4

A 48-year-old man sustained an open olecranon fracture in another country. The fracture was initially treated with 1 dose of intravenously administered antibiotics and 5 days of orally administered antibiotics. The patient returned to the United States and was treated with intravenously administered antibiotics for cellulitis of the elbow for 11 days before referral to our institution, where he underwent ORIF with placement of an antibiotic-coated plate and tension-band wiring. Soft-tissue and bone cultures had no growth. He received intravenously administered antibiotics for 6 weeks. At 5 months postoperatively, the plate was removed because of pain. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 8A-8C).

Discussion

Acute infections of fractures have recently been treated with success by Berkes and colleagues,1 who reported a 71% union rate achieved with operative débridement, antibiotic suppression, and retention of fixation until fracture union occurs. The study by Berkes and colleagues1 had a small patient population, and larger cohorts are needed to show more reliable results; however, this treatment maintains structural support for the fracture during healing but requires multiple trips to the operating room for débridements as well as the use of systemic intravenous antibiotic therapy.

A technique that was developed by the primary author (Janet D. Conway, MD) and has not been described in the literature allows for use of antibiotic cement–coated plates to treat early postoperative infections and osteomyelitic nonunions. This approach permits fracture stabilization and local delivery of high concentrations of broad-spectrum antibiotics and can reduce the number of débridement procedures required in the operating room. We present a technique that includes the use of antibiotic cement–coated plates to treat early postoperative infections associated with fractures and nonunions in order to provide eradication of infection and bony stabilization.

Our approach parallels the current theory that treating infection at a site of union is preferable to treating infection at a site of nonunion.1 Fixation devices should remain in place until osseous union is achieved. With the addition of antibiotics to the plate, removal might not be necessary unless a device is loose, nonfunctional, or, ultimately, causing pain. Other options, such as external fixation, can be burdensome to patients and can be associated with other risks. One of our 4 patients required fixation removal because of pain at the elbow; however, even noncoated olecranon plates typically are removed because of pain after fracture healing. Antibiotic cement adds bulk to the construct and can become very prominent in areas of little soft-tissue coverage (Figure 9).

Studies, assessing variables that correlate with higher likelihood of failure for primary repairs, have shown that open fracture, use of an intramedullary nail, and smoking are the highest risk factors for infected nonunion.1−4 Among our 4 patients, 3 were smokers and 1 originally had an open fracture. Smokers have been found to have a 37% higher nonunion rate and are 2 times more likely to develop wound infection and osteomyelitis.1,5 More than 60% of the time, infections are caused by S aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci.1,5,6 In our study population, 3 of the 4 patients had coagulase-negative staphylococci grow in the cultures. Implants infected with S aureus or Candida require surgical removal. Those with less virulent coagulase-negative staphylococci might not necessitate removal; however, our population had had antibiotic therapy and continued draining sinus.5 Rightmire and colleagues7 reported that those who develop infection earlier than 16 weeks postoperatively have a 68% success rate and that smoking is a major risk factor for infection. Development of Pseudomonas in the wound has been shown to have a positive correlation with amputation.1,2 Infection with Pseudomonas, smoking, and involvement of the femur, tibia, ankle, or foot tended to result in failure.1,2 Being clinically free of signs of infection after 3 months offers a 50% cure rate, with 78% at 6 months and 95% after 1 year.2

When determining an antibiotic to use with the polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement, many factors must be considered, including spectrum, heat stability, and elution characteristics.8 A synergistic effect has been seen with combinations of antibiotics (eg, vancomycin and tobramycin used together). Vancomycin concentrations increased by 103% and tobramycin by 68% when used together compared with their elution rates when used alone, showing passive opportunism.9 This will, in essence, increase concentrations of antibiotics at the site locally, which will increase the bacteriocidal potential but also create a larger antimicrobial spectrum.9

The authors used Cobalt Bone Cement (Biomet Orthopedics, Inc, Warsaw, Indiana) which been shown to have higher elution properties than Simplex P Bone Cement (Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan).3,10 The majority of elution occurs in the first 3 to 5 days but can continue for weeks after implantation. We place the cement on the plate allowing for its retention, hoping to eliminate a second surgery for removal.8 We recommend 3.6 g of tobramycin, and 1 g of vancomycin per 40-g bag of PMMA.3 This dose has been shown to be safe in respect to renal toxicity, plus the entire dose is not administered in a single setting because only a small portion of the cement is used when coating the plate. We close all wounds primarily, and do not regularly use drains or vacuum-assisted closures to help prevent a decrease in the local concentration of the antibiotics.11

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used to coat the plate in order to cover as many microbial organisms as possible without knowing the final offending organism. In our experience, this current technique provides antibiotic delivery with bony stability, therefore eliminating the need for multiple sequential surgical procedures. This difficult patient problem does not occur with enough frequency to warrant a large randomized clinical trial. However, this technique has been effective in these cases and may be useful to orthopedic surgeons in the future.

Conclusion

Based on our experience, early aggressive débridement, coupled with broad-spectrum antibiotic cement–coated plate insertion, provides fracture stability and helps eradicate the infection with 1 surgical procedure.

1. Berkes M, Obremskey WT, Scannell B, et al. Maintenance of hardware after early postoperative infection following fracture internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):823-828.

2. Tice AD, Hoaglund PA, Shoultz, DA. Risk factors and treatment outcomes in osteomyelitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(5):1261-1268.

3. Patzakis MJ, Zalavras CG. Chronic posttraumatic osteomyelitis and infected nonunion of the tibia: current management concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(6):417-427.

4. Castillo RC, Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Patterson BM; LEAP Study Group. Impact of smoking on fracture healing and risk of complications in limb-threatening open tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(3):151-157.

5. Liporace FA, Yoon RS, Frank MA, et al. Use of an “antibiotic plate” for infected periprosthetic fracture in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(3):e18-e23.

6. Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1422-1429.

7. Rightmire E, Zurakowski D, Vrahas M. Acute infections after fracture repair: management with hardware in place. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(2):466-472.

8. Adams K, Couch L, Cierny G, Calhoun J, Mader JT. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of antibiotic diffusion from antibiotic-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate beads. Clin Orthop. 1992;(278):244-252.

9. Penner MJ, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Elution characteristics of vancomycin and tobramycin combined in acrylic bone-cement. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(8):939-944.

10. Greene N, Holtom PD, Warren CA, et al. In vitro elution of tobramycin and vancomycin polymethylmethacrylate beads and spacers from Simplex and Palacos. Am J Orthop. 1998;27(3):201-205.

11. Kalil GZ, Ernst EJ, Johnson SJ, et al. Systemic exposure to aminoglycosides following knee and hip arthroplasty with aminoglycoside-loaded bone cement implants. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(7-8):929-934.

Deep infection in the presence of an implant after open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is usually treated with removal of the implant, serial débridement procedures, lavage, intravenously administered antibiotics, and, in some cases, placement of antibiotic-impregnated beads. If infection occurs during the early stages of bone healing, stabilization of the fractures might be compromised after removal of the implant. Although antibiotic-impregnated beads offer local delivery of antibiotics, they do not provide structural support of the fracture site. The beads often are difficult to remove after in-growth of granulation tissue. In areas of subcutaneous bone, an antibiotic bead pouch might be preferred to an open wound. Published research regarding the use of antibiotic-coated plates during the acute or chronic stages of infection is scarce. Plates offer the versatility of fracture stabilization, and the addition of antibiotic cement to the plates might aid in eradication of infection without necessitating a second surgery for removal. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Technique

After removal of implants, we perform débridement of the soft tissues with a hydroscalpel (Versajet; Smith & Nephew, London, United Kingdom), mechanical débridement of bone, and curettage with high speed burr. The wound is then irrigated with pulse pressure lavage and a minimum of 3 L sterile normal saline. The extremity is re-prepped and re-draped; the entire surgical team’s gowns and gloves are changed; and new instrumentation, including cautery and suction equipment, is used. The cement is prepared with tobramycin (3.6 g) and vancomycin (1 g) per 40-g bag of cement. The plate is placed in silicon tubing, and the antibiotic-prepared cement is injected into the tubing and molded until dry. Care is taken to mold the locations of the screw holes by making incisions in the tubing at the appropriate locations. Screws are placed through the screw holes to ensure locking capability, and Kirschner wires are placed through temporary fixation holes (Figure 1). Once dry, the screws and wires are removed from the plate, and the cement-coated plate is removed from the tubing. The antibiotic-coated plate is applied to the fracture or osteotomy site and is seated with screws as appropriate (Figure 2). The wound is closed primarily. Wound drains or vacuum-assisted closure devices are not routinely used unless there is high risk for hematoma formation. The authors prefer to have high local concentrations of antibiotic in the surrounding tissues and wound.

Clinical Series

Case 1

A 31-year-old man fell from a ladder and sustained a bimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation that was treated with ORIF. Three weeks after initial injury, the patient presented with an infected lateral wound with purulent discharge. He was taken to the operating room for initial débridement, irrigation, and fracture stabilization with an antibiotic-coated plate and tension-band wiring of the medial malleoli. He was discharged from the hospital on day 4 after admission. Cultures of the wound grew beta-hemolytic strep group G and coagulase-negative staphylococci in broth that was sensitive to oxacillin, vancomycin, and gentamycin. The patient was treated with a 6-week regimen of Unasyn (Roerig, New York, New York), developed bony union, and has been free of clinical signs of infection for 2 years (Figures 3, 4).

Case 2

A 27-year-old male carpenter fell from a height of 12 feet and sustained a fracture of the distal radius that was treated with external fixation. The proximal pin site became clinically infected and subsequently developed osteomyelitis. The patient had a draining wound with a fracture for 2 months. He underwent débridement with partial resection of the radius and placement of an antibiotic cement–coated plate and calcium phosphate bone-void filler impregnated with antibiotics. Pathology specimens were positive for osteomyelitis, and bone cultures showed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). He received intravenously administered antibiotic therapy for 6 weeks after surgery. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 5A, 5B).

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and venous stasis sustained a trimalleolar ankle fracture after a low-energy fall that was initially treated with ORIF. She underwent revision ORIF to treat a malunion 3 months after initial treatment. At 8 months, the patient developed a draining sinus communicating with the plate. Computed tomography revealed nonunion and indicated infection. The patient underwent resection of the osteomyelitis and repair of the fibular nonunion with an antibiotic-coated plate. Tissue cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococcus, and pathology specimens were positive for osteomyelitis. She received postoperative antibiotics intravenously and 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy after discharge from the hospital. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 6, 7).

Case 4

A 48-year-old man sustained an open olecranon fracture in another country. The fracture was initially treated with 1 dose of intravenously administered antibiotics and 5 days of orally administered antibiotics. The patient returned to the United States and was treated with intravenously administered antibiotics for cellulitis of the elbow for 11 days before referral to our institution, where he underwent ORIF with placement of an antibiotic-coated plate and tension-band wiring. Soft-tissue and bone cultures had no growth. He received intravenously administered antibiotics for 6 weeks. At 5 months postoperatively, the plate was removed because of pain. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 8A-8C).

Discussion

Acute infections of fractures have recently been treated with success by Berkes and colleagues,1 who reported a 71% union rate achieved with operative débridement, antibiotic suppression, and retention of fixation until fracture union occurs. The study by Berkes and colleagues1 had a small patient population, and larger cohorts are needed to show more reliable results; however, this treatment maintains structural support for the fracture during healing but requires multiple trips to the operating room for débridements as well as the use of systemic intravenous antibiotic therapy.

A technique that was developed by the primary author (Janet D. Conway, MD) and has not been described in the literature allows for use of antibiotic cement–coated plates to treat early postoperative infections and osteomyelitic nonunions. This approach permits fracture stabilization and local delivery of high concentrations of broad-spectrum antibiotics and can reduce the number of débridement procedures required in the operating room. We present a technique that includes the use of antibiotic cement–coated plates to treat early postoperative infections associated with fractures and nonunions in order to provide eradication of infection and bony stabilization.

Our approach parallels the current theory that treating infection at a site of union is preferable to treating infection at a site of nonunion.1 Fixation devices should remain in place until osseous union is achieved. With the addition of antibiotics to the plate, removal might not be necessary unless a device is loose, nonfunctional, or, ultimately, causing pain. Other options, such as external fixation, can be burdensome to patients and can be associated with other risks. One of our 4 patients required fixation removal because of pain at the elbow; however, even noncoated olecranon plates typically are removed because of pain after fracture healing. Antibiotic cement adds bulk to the construct and can become very prominent in areas of little soft-tissue coverage (Figure 9).

Studies, assessing variables that correlate with higher likelihood of failure for primary repairs, have shown that open fracture, use of an intramedullary nail, and smoking are the highest risk factors for infected nonunion.1−4 Among our 4 patients, 3 were smokers and 1 originally had an open fracture. Smokers have been found to have a 37% higher nonunion rate and are 2 times more likely to develop wound infection and osteomyelitis.1,5 More than 60% of the time, infections are caused by S aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci.1,5,6 In our study population, 3 of the 4 patients had coagulase-negative staphylococci grow in the cultures. Implants infected with S aureus or Candida require surgical removal. Those with less virulent coagulase-negative staphylococci might not necessitate removal; however, our population had had antibiotic therapy and continued draining sinus.5 Rightmire and colleagues7 reported that those who develop infection earlier than 16 weeks postoperatively have a 68% success rate and that smoking is a major risk factor for infection. Development of Pseudomonas in the wound has been shown to have a positive correlation with amputation.1,2 Infection with Pseudomonas, smoking, and involvement of the femur, tibia, ankle, or foot tended to result in failure.1,2 Being clinically free of signs of infection after 3 months offers a 50% cure rate, with 78% at 6 months and 95% after 1 year.2

When determining an antibiotic to use with the polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement, many factors must be considered, including spectrum, heat stability, and elution characteristics.8 A synergistic effect has been seen with combinations of antibiotics (eg, vancomycin and tobramycin used together). Vancomycin concentrations increased by 103% and tobramycin by 68% when used together compared with their elution rates when used alone, showing passive opportunism.9 This will, in essence, increase concentrations of antibiotics at the site locally, which will increase the bacteriocidal potential but also create a larger antimicrobial spectrum.9

The authors used Cobalt Bone Cement (Biomet Orthopedics, Inc, Warsaw, Indiana) which been shown to have higher elution properties than Simplex P Bone Cement (Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan).3,10 The majority of elution occurs in the first 3 to 5 days but can continue for weeks after implantation. We place the cement on the plate allowing for its retention, hoping to eliminate a second surgery for removal.8 We recommend 3.6 g of tobramycin, and 1 g of vancomycin per 40-g bag of PMMA.3 This dose has been shown to be safe in respect to renal toxicity, plus the entire dose is not administered in a single setting because only a small portion of the cement is used when coating the plate. We close all wounds primarily, and do not regularly use drains or vacuum-assisted closures to help prevent a decrease in the local concentration of the antibiotics.11

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used to coat the plate in order to cover as many microbial organisms as possible without knowing the final offending organism. In our experience, this current technique provides antibiotic delivery with bony stability, therefore eliminating the need for multiple sequential surgical procedures. This difficult patient problem does not occur with enough frequency to warrant a large randomized clinical trial. However, this technique has been effective in these cases and may be useful to orthopedic surgeons in the future.

Conclusion

Based on our experience, early aggressive débridement, coupled with broad-spectrum antibiotic cement–coated plate insertion, provides fracture stability and helps eradicate the infection with 1 surgical procedure.

Deep infection in the presence of an implant after open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is usually treated with removal of the implant, serial débridement procedures, lavage, intravenously administered antibiotics, and, in some cases, placement of antibiotic-impregnated beads. If infection occurs during the early stages of bone healing, stabilization of the fractures might be compromised after removal of the implant. Although antibiotic-impregnated beads offer local delivery of antibiotics, they do not provide structural support of the fracture site. The beads often are difficult to remove after in-growth of granulation tissue. In areas of subcutaneous bone, an antibiotic bead pouch might be preferred to an open wound. Published research regarding the use of antibiotic-coated plates during the acute or chronic stages of infection is scarce. Plates offer the versatility of fracture stabilization, and the addition of antibiotic cement to the plates might aid in eradication of infection without necessitating a second surgery for removal. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Technique

After removal of implants, we perform débridement of the soft tissues with a hydroscalpel (Versajet; Smith & Nephew, London, United Kingdom), mechanical débridement of bone, and curettage with high speed burr. The wound is then irrigated with pulse pressure lavage and a minimum of 3 L sterile normal saline. The extremity is re-prepped and re-draped; the entire surgical team’s gowns and gloves are changed; and new instrumentation, including cautery and suction equipment, is used. The cement is prepared with tobramycin (3.6 g) and vancomycin (1 g) per 40-g bag of cement. The plate is placed in silicon tubing, and the antibiotic-prepared cement is injected into the tubing and molded until dry. Care is taken to mold the locations of the screw holes by making incisions in the tubing at the appropriate locations. Screws are placed through the screw holes to ensure locking capability, and Kirschner wires are placed through temporary fixation holes (Figure 1). Once dry, the screws and wires are removed from the plate, and the cement-coated plate is removed from the tubing. The antibiotic-coated plate is applied to the fracture or osteotomy site and is seated with screws as appropriate (Figure 2). The wound is closed primarily. Wound drains or vacuum-assisted closure devices are not routinely used unless there is high risk for hematoma formation. The authors prefer to have high local concentrations of antibiotic in the surrounding tissues and wound.

Clinical Series

Case 1

A 31-year-old man fell from a ladder and sustained a bimalleolar ankle fracture-dislocation that was treated with ORIF. Three weeks after initial injury, the patient presented with an infected lateral wound with purulent discharge. He was taken to the operating room for initial débridement, irrigation, and fracture stabilization with an antibiotic-coated plate and tension-band wiring of the medial malleoli. He was discharged from the hospital on day 4 after admission. Cultures of the wound grew beta-hemolytic strep group G and coagulase-negative staphylococci in broth that was sensitive to oxacillin, vancomycin, and gentamycin. The patient was treated with a 6-week regimen of Unasyn (Roerig, New York, New York), developed bony union, and has been free of clinical signs of infection for 2 years (Figures 3, 4).

Case 2

A 27-year-old male carpenter fell from a height of 12 feet and sustained a fracture of the distal radius that was treated with external fixation. The proximal pin site became clinically infected and subsequently developed osteomyelitis. The patient had a draining wound with a fracture for 2 months. He underwent débridement with partial resection of the radius and placement of an antibiotic cement–coated plate and calcium phosphate bone-void filler impregnated with antibiotics. Pathology specimens were positive for osteomyelitis, and bone cultures showed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). He received intravenously administered antibiotic therapy for 6 weeks after surgery. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 5A, 5B).

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and venous stasis sustained a trimalleolar ankle fracture after a low-energy fall that was initially treated with ORIF. She underwent revision ORIF to treat a malunion 3 months after initial treatment. At 8 months, the patient developed a draining sinus communicating with the plate. Computed tomography revealed nonunion and indicated infection. The patient underwent resection of the osteomyelitis and repair of the fibular nonunion with an antibiotic-coated plate. Tissue cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococcus, and pathology specimens were positive for osteomyelitis. She received postoperative antibiotics intravenously and 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy after discharge from the hospital. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 6, 7).

Case 4

A 48-year-old man sustained an open olecranon fracture in another country. The fracture was initially treated with 1 dose of intravenously administered antibiotics and 5 days of orally administered antibiotics. The patient returned to the United States and was treated with intravenously administered antibiotics for cellulitis of the elbow for 11 days before referral to our institution, where he underwent ORIF with placement of an antibiotic-coated plate and tension-band wiring. Soft-tissue and bone cultures had no growth. He received intravenously administered antibiotics for 6 weeks. At 5 months postoperatively, the plate was removed because of pain. The patient has remained free of clinical signs of infection for more than 1 year and has achieved bony union (Figures 8A-8C).

Discussion