User login

2015 Update on cancer

As the proportion of the elderly in the US population continues to increase, with life expectancy trending upward, we can expect to see more gynecologic cancers in our patients.1,2 At present, the most effective approach to these cancers commonly includes aggressive surgical resection with chemotherapy and, in some cases, radiation. It remains unclear whether elderly patients should be managed the same as younger patients, with minimal data to guide physicians. Some evidence suggests an increased risk of surgical complications in older adults.3

To optimize surgical care in our elderly patients, we need to understand the risks of perioperative mortality and morbidity in this population. For example, the current standard of care for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is aggressive cytoreductive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy,4 although neoadjuvant chemotherapy is gaining utility and popularity in certain circumstances. During pretreatment counseling, it is imperative that we communicate patient-specific outcomes so that patients and their families can make educated decisions in line with their goals. What should we know about age-dependent outcomes when counseling our patients?

To optimize surgical care in this population, we also need to develop and use new methods of surgical decision making. Although some data suggest that age is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications, not all elderly patients are the same in terms of comorbidities and functional status. In order to truly assess risks, we need to identify additional preoperative risk factors. Are there accurate scoring tools or predictors of outcomes available to help us assess the risks of postoperative mortality and morbidity?

In this article, we highlight recent developments in surgical treatment of the elderly, focusing on:

- postoperative mortality and morbidity in patients older than 80 years

- adjuncts to preoperative assessment for oncogeriatric surgical patients.

Risks rise sharply in older patients undergoing treatment for ovarian Ca

Moore KN, Reid MS, Fong DN, et al. Ovarian cancer in the octogenarian: does the paradigm of aggressive cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy still apply? Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110(2):133–139.

Mahdi H, Wiechert A, Lockhart D, Rose PG. Impact of age on 30-day mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(7):1216–1223.

The cornerstone of optimal survival from certain gynecologic cancers, such as advanced ovarian cancer, is aggressive debulking surgery. However, older adults are classically under-represented in clinical trials that guide this standard of care.

To determine whether patients aged 80 years or older respond differently from younger patients to conventional ovarian cancer management, Moore and colleagues retrospectively reviewed their institutional experience. They found that postoperative mortality increased from 5.4% in patients aged 80 to 84 years to 9.1% in those aged 85 to 89 and 14.4% in those older than 90. The rates for younger patients were 0.6% for patients younger than 60 years, 2.8% for those aged 60 to 69 years, and 2.5% for those aged 70 to 79 years (P<.001).

Notably, 13% of patients aged 80 years or older who underwent primary surgery died during their primary hospitalization. Of those who survived, 50% were discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Of patients who underwent cytoreductive surgery, 13% were unable to undergo any intended adjuvant therapy, and only 57% completed more than 3 cycles of chemotherapy, either due to demise or toxicities. Two-month survival for patients 80 years or older was comparable between patients who underwent primary surgery and those who had primary chemotherapy (20% and 26%, respectively).

With a similar objective, Mahdi and colleagues identified 2,087 patients with ovarian cancer who underwent surgery. After adjusting for confounders with multivariable analyses, they found that octogenarians whose initial management was surgery were 9 times more likely than younger patients to die and 70% more likely to develop complications within 30 days. Among patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there were no significant differences between older and younger patients in 30-day postoperative mortality or morbidity.

When evaluating elderly patients for surgery, the use of multiple risk-assessment strategies may improve accuracy

Huisman MG, Audisio RA, Ugolini G, et al. Screening for predictors of adverse outcome in onco-geriatric surgical patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(7):844–851.

Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice L, Spencer R, Rose SL. Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):98–101.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that clinicians determine baseline life expectancy for older adults with cancer to aid in management decision making. The use of tools such as www.eprognosis.com, developed to determine anticipated life expectancy independent of cancer, can prove useful in determining a patient’s risk of dying or suffering from their cancer before dying of another cause.5

When it comes to the determination of risk related to a patient’s cancer diagnosis and selection of potential management options, many argue that the subgroup of elderly patients is not homogenous and that the use of age alone to guide management decisions may be unfair. Preoperative evaluation ideally should incorporate a global assessment of predictive risk factors.

Three assessment tools are especially useful

Huisman and colleagues set out to identify accurate preoperative assessment methods in elderly patients undergoing oncologic surgery. They prospectively recruited 328 patients aged 70 years or older and evaluated patients preoperatively using 11 well-known geriatric screening tools. They compared these evaluations with outcomes to determine which tools best predict the occurrence of major postoperative complications. They found the strongest correlation with outcomes when combining gender and type of surgery with the following 3 assessment tools:

- Timed Up and Go (TUG)—a walking test to measure functional status

- American Society of Anesthesiologists scale—a scoring system that quantifies preoperative physical status and estimates anesthetic risk

- Nutritional Risk Screening—an assessment of nutritional risk based on recent weight loss, overall condition, and reduction of food intake.

All 3 are simple and short screening tools. When used together, they can provide clinicians with accurate risk estimations.

The findings of Huisman and colleagues reinforce the importance of a global assessment of the patient’s comorbidities, functional status, and nutritional status when determining candidacy for oncologic surgery.

Functional index predicts need for postoperative ICU care and risk of death

Uppal and colleagues set out to quantify the predictive value of the modified Functional Index (mFI) in assessing the need for postoperative critical care support and/or the risk of death within 30 days after gynecologic cancer surgery. The mFI can be calculated by adding 1 point for each variable listed in the TABLE, with a score of 4 or higher representing a high-frailty cohort.

Of 6,551 patients who underwent gynecologic surgery, 188 were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or died within 30 days after surgery. The mFI was calculated, with multivariate analyses of additional variables. An mFI score of 3 or higher was predictive of the need for critical care support and the risk of 30-day mortality and was associated with a significantly higher number of complications (P<.001).

Predictors significant for postoperative critical care support or death were:

- preoperative albumin level less than 3 g/dL (odds ratio [OR] = 6.5)

- operative time (OR = 1.003 per minute of increase)

- nonlaparoscopic surgery (OR = 3.3)

- mFI score, with a score of 0 serving as the reference (OR for a score of 1 = 1.26; score of 2 = 1.9; score of 3 = 2.33; and score of 4 or higher = 12.5).

When they combined the mFI and albumin scores—both readily available in the preoperative setting—Uppal and colleagues were able to develop an algorithm to determine patients who were at “low risk” versus “high risk” for ICU admission and/or death postoperatively (FIGURE).

[[{"fid":"79834","view_mode":"medstat_image_full_text","fields":{"format":"medstat_image_full_text","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Postoperative risk stratification based on preoperative albumin level

and modified Functional Index","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"6"},"type":"media","attributes":{"height":"316","width":"665","class":"media-element file-medstat-image-full-text"}}]]

Bottom line

Older patients are more commonly affected by multiple medical comorbidities, as well as functional, cognitive, and nutritional deficiencies, which contribute to their increased risk of morbidity and mortality after surgery. The elderly experience greater morbidity with noncardiac surgery in general.

Clearly, the decision to operate on an elderly patient should be approached with caution, and a critical assessment of the patient’s risk factors should be performed to inform counseling about the patient’s management options. Future randomized prospective data will help us better understand the relationship between age and surgical outcomes.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- US Census Bureau. Population Projections: Projections of the Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published December 2014. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- US Census Bureau. Population Projections: Percent Distribution of the Projected Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published December 2014. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Polanczyk CA, Marcantonio E, Goldman L, et al. Impact of age on perioperative complications and length of stay in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):637–643.

- Aletti G, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, et al. Aggressive surgical effort and improved survival in advanced stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):77–85.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Age-Related Recommendations: Older Adult Oncology. . Published 2015. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice L, Spencer R, Rose SL. Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):98–101.

As the proportion of the elderly in the US population continues to increase, with life expectancy trending upward, we can expect to see more gynecologic cancers in our patients.1,2 At present, the most effective approach to these cancers commonly includes aggressive surgical resection with chemotherapy and, in some cases, radiation. It remains unclear whether elderly patients should be managed the same as younger patients, with minimal data to guide physicians. Some evidence suggests an increased risk of surgical complications in older adults.3

To optimize surgical care in our elderly patients, we need to understand the risks of perioperative mortality and morbidity in this population. For example, the current standard of care for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is aggressive cytoreductive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy,4 although neoadjuvant chemotherapy is gaining utility and popularity in certain circumstances. During pretreatment counseling, it is imperative that we communicate patient-specific outcomes so that patients and their families can make educated decisions in line with their goals. What should we know about age-dependent outcomes when counseling our patients?

To optimize surgical care in this population, we also need to develop and use new methods of surgical decision making. Although some data suggest that age is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications, not all elderly patients are the same in terms of comorbidities and functional status. In order to truly assess risks, we need to identify additional preoperative risk factors. Are there accurate scoring tools or predictors of outcomes available to help us assess the risks of postoperative mortality and morbidity?

In this article, we highlight recent developments in surgical treatment of the elderly, focusing on:

- postoperative mortality and morbidity in patients older than 80 years

- adjuncts to preoperative assessment for oncogeriatric surgical patients.

Risks rise sharply in older patients undergoing treatment for ovarian Ca

Moore KN, Reid MS, Fong DN, et al. Ovarian cancer in the octogenarian: does the paradigm of aggressive cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy still apply? Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110(2):133–139.

Mahdi H, Wiechert A, Lockhart D, Rose PG. Impact of age on 30-day mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(7):1216–1223.

The cornerstone of optimal survival from certain gynecologic cancers, such as advanced ovarian cancer, is aggressive debulking surgery. However, older adults are classically under-represented in clinical trials that guide this standard of care.

To determine whether patients aged 80 years or older respond differently from younger patients to conventional ovarian cancer management, Moore and colleagues retrospectively reviewed their institutional experience. They found that postoperative mortality increased from 5.4% in patients aged 80 to 84 years to 9.1% in those aged 85 to 89 and 14.4% in those older than 90. The rates for younger patients were 0.6% for patients younger than 60 years, 2.8% for those aged 60 to 69 years, and 2.5% for those aged 70 to 79 years (P<.001).

Notably, 13% of patients aged 80 years or older who underwent primary surgery died during their primary hospitalization. Of those who survived, 50% were discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Of patients who underwent cytoreductive surgery, 13% were unable to undergo any intended adjuvant therapy, and only 57% completed more than 3 cycles of chemotherapy, either due to demise or toxicities. Two-month survival for patients 80 years or older was comparable between patients who underwent primary surgery and those who had primary chemotherapy (20% and 26%, respectively).

With a similar objective, Mahdi and colleagues identified 2,087 patients with ovarian cancer who underwent surgery. After adjusting for confounders with multivariable analyses, they found that octogenarians whose initial management was surgery were 9 times more likely than younger patients to die and 70% more likely to develop complications within 30 days. Among patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there were no significant differences between older and younger patients in 30-day postoperative mortality or morbidity.

When evaluating elderly patients for surgery, the use of multiple risk-assessment strategies may improve accuracy

Huisman MG, Audisio RA, Ugolini G, et al. Screening for predictors of adverse outcome in onco-geriatric surgical patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(7):844–851.

Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice L, Spencer R, Rose SL. Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):98–101.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that clinicians determine baseline life expectancy for older adults with cancer to aid in management decision making. The use of tools such as www.eprognosis.com, developed to determine anticipated life expectancy independent of cancer, can prove useful in determining a patient’s risk of dying or suffering from their cancer before dying of another cause.5

When it comes to the determination of risk related to a patient’s cancer diagnosis and selection of potential management options, many argue that the subgroup of elderly patients is not homogenous and that the use of age alone to guide management decisions may be unfair. Preoperative evaluation ideally should incorporate a global assessment of predictive risk factors.

Three assessment tools are especially useful

Huisman and colleagues set out to identify accurate preoperative assessment methods in elderly patients undergoing oncologic surgery. They prospectively recruited 328 patients aged 70 years or older and evaluated patients preoperatively using 11 well-known geriatric screening tools. They compared these evaluations with outcomes to determine which tools best predict the occurrence of major postoperative complications. They found the strongest correlation with outcomes when combining gender and type of surgery with the following 3 assessment tools:

- Timed Up and Go (TUG)—a walking test to measure functional status

- American Society of Anesthesiologists scale—a scoring system that quantifies preoperative physical status and estimates anesthetic risk

- Nutritional Risk Screening—an assessment of nutritional risk based on recent weight loss, overall condition, and reduction of food intake.

All 3 are simple and short screening tools. When used together, they can provide clinicians with accurate risk estimations.

The findings of Huisman and colleagues reinforce the importance of a global assessment of the patient’s comorbidities, functional status, and nutritional status when determining candidacy for oncologic surgery.

Functional index predicts need for postoperative ICU care and risk of death

Uppal and colleagues set out to quantify the predictive value of the modified Functional Index (mFI) in assessing the need for postoperative critical care support and/or the risk of death within 30 days after gynecologic cancer surgery. The mFI can be calculated by adding 1 point for each variable listed in the TABLE, with a score of 4 or higher representing a high-frailty cohort.

Of 6,551 patients who underwent gynecologic surgery, 188 were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or died within 30 days after surgery. The mFI was calculated, with multivariate analyses of additional variables. An mFI score of 3 or higher was predictive of the need for critical care support and the risk of 30-day mortality and was associated with a significantly higher number of complications (P<.001).

Predictors significant for postoperative critical care support or death were:

- preoperative albumin level less than 3 g/dL (odds ratio [OR] = 6.5)

- operative time (OR = 1.003 per minute of increase)

- nonlaparoscopic surgery (OR = 3.3)

- mFI score, with a score of 0 serving as the reference (OR for a score of 1 = 1.26; score of 2 = 1.9; score of 3 = 2.33; and score of 4 or higher = 12.5).

When they combined the mFI and albumin scores—both readily available in the preoperative setting—Uppal and colleagues were able to develop an algorithm to determine patients who were at “low risk” versus “high risk” for ICU admission and/or death postoperatively (FIGURE).

[[{"fid":"79834","view_mode":"medstat_image_full_text","fields":{"format":"medstat_image_full_text","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Postoperative risk stratification based on preoperative albumin level

and modified Functional Index","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"6"},"type":"media","attributes":{"height":"316","width":"665","class":"media-element file-medstat-image-full-text"}}]]

Bottom line

Older patients are more commonly affected by multiple medical comorbidities, as well as functional, cognitive, and nutritional deficiencies, which contribute to their increased risk of morbidity and mortality after surgery. The elderly experience greater morbidity with noncardiac surgery in general.

Clearly, the decision to operate on an elderly patient should be approached with caution, and a critical assessment of the patient’s risk factors should be performed to inform counseling about the patient’s management options. Future randomized prospective data will help us better understand the relationship between age and surgical outcomes.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As the proportion of the elderly in the US population continues to increase, with life expectancy trending upward, we can expect to see more gynecologic cancers in our patients.1,2 At present, the most effective approach to these cancers commonly includes aggressive surgical resection with chemotherapy and, in some cases, radiation. It remains unclear whether elderly patients should be managed the same as younger patients, with minimal data to guide physicians. Some evidence suggests an increased risk of surgical complications in older adults.3

To optimize surgical care in our elderly patients, we need to understand the risks of perioperative mortality and morbidity in this population. For example, the current standard of care for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is aggressive cytoreductive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy,4 although neoadjuvant chemotherapy is gaining utility and popularity in certain circumstances. During pretreatment counseling, it is imperative that we communicate patient-specific outcomes so that patients and their families can make educated decisions in line with their goals. What should we know about age-dependent outcomes when counseling our patients?

To optimize surgical care in this population, we also need to develop and use new methods of surgical decision making. Although some data suggest that age is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications, not all elderly patients are the same in terms of comorbidities and functional status. In order to truly assess risks, we need to identify additional preoperative risk factors. Are there accurate scoring tools or predictors of outcomes available to help us assess the risks of postoperative mortality and morbidity?

In this article, we highlight recent developments in surgical treatment of the elderly, focusing on:

- postoperative mortality and morbidity in patients older than 80 years

- adjuncts to preoperative assessment for oncogeriatric surgical patients.

Risks rise sharply in older patients undergoing treatment for ovarian Ca

Moore KN, Reid MS, Fong DN, et al. Ovarian cancer in the octogenarian: does the paradigm of aggressive cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy still apply? Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110(2):133–139.

Mahdi H, Wiechert A, Lockhart D, Rose PG. Impact of age on 30-day mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(7):1216–1223.

The cornerstone of optimal survival from certain gynecologic cancers, such as advanced ovarian cancer, is aggressive debulking surgery. However, older adults are classically under-represented in clinical trials that guide this standard of care.

To determine whether patients aged 80 years or older respond differently from younger patients to conventional ovarian cancer management, Moore and colleagues retrospectively reviewed their institutional experience. They found that postoperative mortality increased from 5.4% in patients aged 80 to 84 years to 9.1% in those aged 85 to 89 and 14.4% in those older than 90. The rates for younger patients were 0.6% for patients younger than 60 years, 2.8% for those aged 60 to 69 years, and 2.5% for those aged 70 to 79 years (P<.001).

Notably, 13% of patients aged 80 years or older who underwent primary surgery died during their primary hospitalization. Of those who survived, 50% were discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Of patients who underwent cytoreductive surgery, 13% were unable to undergo any intended adjuvant therapy, and only 57% completed more than 3 cycles of chemotherapy, either due to demise or toxicities. Two-month survival for patients 80 years or older was comparable between patients who underwent primary surgery and those who had primary chemotherapy (20% and 26%, respectively).

With a similar objective, Mahdi and colleagues identified 2,087 patients with ovarian cancer who underwent surgery. After adjusting for confounders with multivariable analyses, they found that octogenarians whose initial management was surgery were 9 times more likely than younger patients to die and 70% more likely to develop complications within 30 days. Among patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there were no significant differences between older and younger patients in 30-day postoperative mortality or morbidity.

When evaluating elderly patients for surgery, the use of multiple risk-assessment strategies may improve accuracy

Huisman MG, Audisio RA, Ugolini G, et al. Screening for predictors of adverse outcome in onco-geriatric surgical patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(7):844–851.

Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice L, Spencer R, Rose SL. Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):98–101.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that clinicians determine baseline life expectancy for older adults with cancer to aid in management decision making. The use of tools such as www.eprognosis.com, developed to determine anticipated life expectancy independent of cancer, can prove useful in determining a patient’s risk of dying or suffering from their cancer before dying of another cause.5

When it comes to the determination of risk related to a patient’s cancer diagnosis and selection of potential management options, many argue that the subgroup of elderly patients is not homogenous and that the use of age alone to guide management decisions may be unfair. Preoperative evaluation ideally should incorporate a global assessment of predictive risk factors.

Three assessment tools are especially useful

Huisman and colleagues set out to identify accurate preoperative assessment methods in elderly patients undergoing oncologic surgery. They prospectively recruited 328 patients aged 70 years or older and evaluated patients preoperatively using 11 well-known geriatric screening tools. They compared these evaluations with outcomes to determine which tools best predict the occurrence of major postoperative complications. They found the strongest correlation with outcomes when combining gender and type of surgery with the following 3 assessment tools:

- Timed Up and Go (TUG)—a walking test to measure functional status

- American Society of Anesthesiologists scale—a scoring system that quantifies preoperative physical status and estimates anesthetic risk

- Nutritional Risk Screening—an assessment of nutritional risk based on recent weight loss, overall condition, and reduction of food intake.

All 3 are simple and short screening tools. When used together, they can provide clinicians with accurate risk estimations.

The findings of Huisman and colleagues reinforce the importance of a global assessment of the patient’s comorbidities, functional status, and nutritional status when determining candidacy for oncologic surgery.

Functional index predicts need for postoperative ICU care and risk of death

Uppal and colleagues set out to quantify the predictive value of the modified Functional Index (mFI) in assessing the need for postoperative critical care support and/or the risk of death within 30 days after gynecologic cancer surgery. The mFI can be calculated by adding 1 point for each variable listed in the TABLE, with a score of 4 or higher representing a high-frailty cohort.

Of 6,551 patients who underwent gynecologic surgery, 188 were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or died within 30 days after surgery. The mFI was calculated, with multivariate analyses of additional variables. An mFI score of 3 or higher was predictive of the need for critical care support and the risk of 30-day mortality and was associated with a significantly higher number of complications (P<.001).

Predictors significant for postoperative critical care support or death were:

- preoperative albumin level less than 3 g/dL (odds ratio [OR] = 6.5)

- operative time (OR = 1.003 per minute of increase)

- nonlaparoscopic surgery (OR = 3.3)

- mFI score, with a score of 0 serving as the reference (OR for a score of 1 = 1.26; score of 2 = 1.9; score of 3 = 2.33; and score of 4 or higher = 12.5).

When they combined the mFI and albumin scores—both readily available in the preoperative setting—Uppal and colleagues were able to develop an algorithm to determine patients who were at “low risk” versus “high risk” for ICU admission and/or death postoperatively (FIGURE).

[[{"fid":"79834","view_mode":"medstat_image_full_text","fields":{"format":"medstat_image_full_text","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Postoperative risk stratification based on preoperative albumin level

and modified Functional Index","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"6"},"type":"media","attributes":{"height":"316","width":"665","class":"media-element file-medstat-image-full-text"}}]]

Bottom line

Older patients are more commonly affected by multiple medical comorbidities, as well as functional, cognitive, and nutritional deficiencies, which contribute to their increased risk of morbidity and mortality after surgery. The elderly experience greater morbidity with noncardiac surgery in general.

Clearly, the decision to operate on an elderly patient should be approached with caution, and a critical assessment of the patient’s risk factors should be performed to inform counseling about the patient’s management options. Future randomized prospective data will help us better understand the relationship between age and surgical outcomes.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- US Census Bureau. Population Projections: Projections of the Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published December 2014. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- US Census Bureau. Population Projections: Percent Distribution of the Projected Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published December 2014. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Polanczyk CA, Marcantonio E, Goldman L, et al. Impact of age on perioperative complications and length of stay in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):637–643.

- Aletti G, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, et al. Aggressive surgical effort and improved survival in advanced stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):77–85.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Age-Related Recommendations: Older Adult Oncology. . Published 2015. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice L, Spencer R, Rose SL. Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):98–101.

- US Census Bureau. Population Projections: Projections of the Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published December 2014. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- US Census Bureau. Population Projections: Percent Distribution of the Projected Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html. Published December 2014. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Polanczyk CA, Marcantonio E, Goldman L, et al. Impact of age on perioperative complications and length of stay in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):637–643.

- Aletti G, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, et al. Aggressive surgical effort and improved survival in advanced stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):77–85.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Age-Related Recommendations: Older Adult Oncology. . Published 2015. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice L, Spencer R, Rose SL. Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):98–101.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Preoperative risk-assessment strategies

- The 11-item modified Functional Index

- Using the Functional Index in practice

2014 Update on ovarian cancer

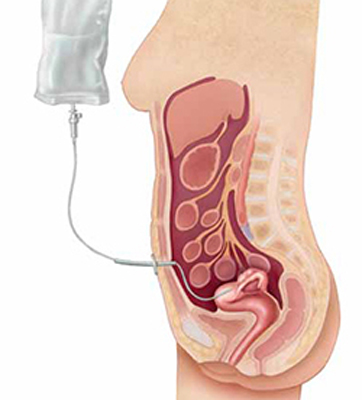

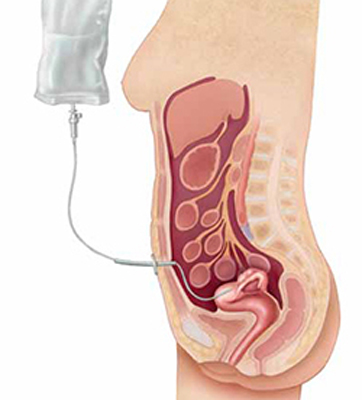

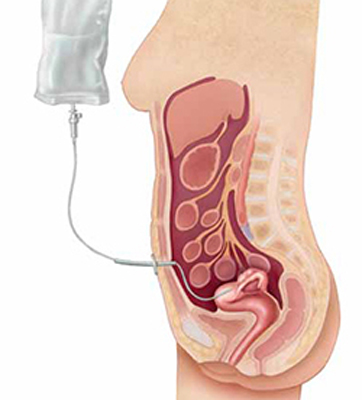

Ovarian cancer remains the deadliest gynecologic malignancy in the United States, with more than 22,000 women newly diagnosed and more than 14,000 deaths each year. We have made slow progress in terms of survival with new drugs and applications, such as intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with more aggressive cytoreductive efforts. Five-year survival rates have increased—from 36% to 44%—since the late 1970s.1 To make the leap from molecular genetics to successful screening, early diagnosis, and targeted treatment, we must first:

- Enhance our understanding of the changes that lead to ovarian cancer. Currently, malignant transformation of the fallopian tube epithelium is thought to result in high-grade papillary serous cancer.2 If this is indeed the pathologic origin of ovarian cancers, then early detection or even detection in the premalignant phase may be possible using tests of vaginal fluid. Are early detection, and even screening, possible and how would it effect treatment and survival?

- Develop new and powerful tools to detect molecular changes that might impact treatment and survival. Just a few years ago, initial sequencing of the human genome cost more than $100 million, but DNA sequencing technologies have evolved rapidly, with current estimates at less than a few thousand dollars per genome.3 Knowing the mutations responsible for an individual’s cancer would allow for targeted, individualized treatment plans. Would one patient benefit from neoadjuvant therapy while another needs primary surgical debulking?

In this article, we highlight the historical basis and recent developments in the field of ovarian cancer, focusing on:

- etiologic heterogeneity and molecular biology detection of small numbers of cancer cells in vaginal secretions and the blood stream.

- detection of small numbers of cancer cells in vaginal secretions and the blood stream.

What mutations are we looking for?

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609−615.

In last year’s Update, we discussed the role of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project in endometrial cancer.4 For ovarian cancer, TCGA analyzed messenger RNA expression, microRNA expression, promoter methylation, and DNA copy number in 489 high-grade serous ovarian adenocarcinomas and the DNA sequences of exons from coding genes in 316 of these tumors.

Almost all tumors (96%) were characterized by mutations of the gene encoding TP53 in addition to statistically recurrent mutations in nine other loci, including NF1, BRCA1, BRCA2, RB1, and CDK12, although these were of low prevalence. Analyses also brought new insight regarding the survival impact of tumors containing BRCA1 or BRCA2 and CCNE1 mutations. Findings included NOTCH and FOXM1 signaling involvement in serous ovarian cancer pathophysiology as well as defective homologous recombination in approximately half of the tumors studied.

What this evidence means for practiceWith these mutations as our targets, we can screen vaginal secretions as well as blood for markers of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian and endometrial cancer cells detected in the vagina

Kinde I, Bettegowda C, Wang Y, et al. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(167):167ra4.

Erickson BK, Kinde I, Dobbin AC, et al. Detection of somatic TP53 mutations in tampons of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer [published online ahead of print October 2014]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5).

Ruth Graham, Papanicolaou’s cytology technician in the 1940s, first described ovarian cancer cells detected in vaginal/cervical cytology obtained from vaginal secretions.5 Current studies now demonstrate that we have technology capable of more than simple cytologic detection. We can isolate and evaluate these cancer cells in very small numbers.

Ovarian and endometrial cancer DNA identified in Pap specimenKinde and colleagues assembled a catalog of common mutations previously found in ovarian cancer as well as new data on 22 endometrial tumors. They tested 24 endometrial and 22 ovarian samples from patients with endometrial or ovarian cancers and confirmed that all 46 harbored at least some component of the common genetic changes in their catalog. Hypothesizing that the cancers likely shed cells from their surfaces, they sought to determine whether they could detect these cells among the cervical cells in a Pap smear.

These investigators used massively parallel sequencing to test DNA collected in modern liquid-based cytologic specimens for the same mutations found in the cancer cells. They found that 100% of the endometrial cancers and 41% of ovarian cancers were detectable by this method.

TP53 mutations in ovarian cancer cells detected in vaginally placed tamponWith similar technology, but a different collection method, Erickson and colleagues sought to detect tumor cells in the vagina of women with serous ovarian cancer by TP53 analysis of DNA samples collected via vaginal tampon.

Thirty-three women with pelvic masses suspicious for malignancy and scheduled to undergo diagnostic or therapeutic surgery were enrolled. Of the 25 patients who placed the tampon 8 to 12 hours prior to surgery; 13 had benign disease; three had nonovarian malignancies; and nine had serous adenocarcinoma of ovarian, tubal, or primary peritoneal origin. DNA from tumor specimens of eight patients with serous carcinoma and adequate DNA samples were analyzed for TP53 mutations. The corresponding DNA extracted from the tampon was then probed for the mutation identified in the tumor.

Mutational analysis of the tampon specimen DNA revealed no mutations in the tampon DNA of the three patients who had previously undergone tubal ligation, while mutations were observed in three of the five patients with intact tubes—producing a sensitivity of 60%. The fraction of mutant alleles in the tampon DNA was extremely low at 0.01% to 0.07%, requiring ultra-deep sequencing and increasing the importance of paired primary tumor specimens.

What this evidence means for practiceWhile sensitivity in a population of high-risk patients with intact tubes was found to be 60%, it is unclear what it would be in patients with less advanced disease. The ability of the test to detect mutations at exceptionally low limits is impressive; however, it increases the risk that a variant represents a sequencing error or a sample-to-sample contamination. This study is novel in its approach to diagnosis of ovarian cancer and is a stride toward screening, providing an opportunity to further validate the technology prior to widespread use and clinical application.

Circulating tumor cells—the future of cancer management?

Obermayr E, Castillo-Tong DC, Pils D, et al. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in patients with ovarian cancer improves their prognostic significance: a study of the OVCAD consortium. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):15−21.

Similar in concept to noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy, high circulating tumor cell (CTC) numbers have been correlated with aggressive disease, increased metastasis, and decreased time to relapse. As with cancer cells in vaginal secretions, CTCs also may provide an opportunity for early detection and targeted treatment.6

While many CTC studies have used epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)−based CTC detection, results have been found to be highly variable between tumor subtypes and phase of disease.7 Therefore, Obermayer and colleagues sought to identify novel markers for CTCs in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and elucidate their impact on outcome.

Details of the studyMatched ovarian cancer tissues and peripheral blood leukocytes of 35 patients underwent microarray analysis to identify novel CTC markers. Gene expression of the novel markers as well as EpCAM were analyzed using blood samples taken from 39 healthy females and from 216 patients with ovarian cancer before primary treatment and 6 months after adjuvant chemotherapy. Overexpression of at least one gene, compared with the healthy control group, was considered CTC positivity.

CTCs were detected in 24.5% of the baseline and 20.4% of the follow-up samples, of which two-thirds showed overexpression of the cyclophilin C gene (PPIC), and just a few by EpCAM overexpression. PPIC-positive CTCs during follow-up were detected significantly more often in the platinum resistant group, and indicated poor outcome even when controlling for classical prognostic parameters.

What this evidence means for practiceThe study authors found that molecular characterization of CTC is superior to CTC enumeration. Ultimately, CTC diagnostics may lead to earlier detection and more personalized treatment of ovarian cancer.

Therefore, this technology could have great impact on screening for and the survival of a large subset of patients with ovarian cancer. In addition, the cells obtained preoperatively could help assess the risk of malignancy in an ovarian mass prior to surgery, or even help in treatment planning, as we enter an era in which we have the ability to assess cancers for prognosis and features of treatment response.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected].

1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29.

2. Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195(4):451–456.

3. Wetterstrand KA. DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP). http://www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts. Updated July 18, 2014. Accessed September 21, 2014.

4. Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, et al; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73.

5. Papanicolaou GN, Traut HF. The diagnostic value of vaginal smears in carcinoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1941;42:193–206.

6. Plaks V, Koopman CD, Werb Z. Cancer. Circulating tumor cells. Science. 2013;341(6151):1186–1188.

7. Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, et al. Anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies and the detection of circulating normal-like breast tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(1):61–66.

Ovarian cancer remains the deadliest gynecologic malignancy in the United States, with more than 22,000 women newly diagnosed and more than 14,000 deaths each year. We have made slow progress in terms of survival with new drugs and applications, such as intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with more aggressive cytoreductive efforts. Five-year survival rates have increased—from 36% to 44%—since the late 1970s.1 To make the leap from molecular genetics to successful screening, early diagnosis, and targeted treatment, we must first:

- Enhance our understanding of the changes that lead to ovarian cancer. Currently, malignant transformation of the fallopian tube epithelium is thought to result in high-grade papillary serous cancer.2 If this is indeed the pathologic origin of ovarian cancers, then early detection or even detection in the premalignant phase may be possible using tests of vaginal fluid. Are early detection, and even screening, possible and how would it effect treatment and survival?

- Develop new and powerful tools to detect molecular changes that might impact treatment and survival. Just a few years ago, initial sequencing of the human genome cost more than $100 million, but DNA sequencing technologies have evolved rapidly, with current estimates at less than a few thousand dollars per genome.3 Knowing the mutations responsible for an individual’s cancer would allow for targeted, individualized treatment plans. Would one patient benefit from neoadjuvant therapy while another needs primary surgical debulking?

In this article, we highlight the historical basis and recent developments in the field of ovarian cancer, focusing on:

- etiologic heterogeneity and molecular biology detection of small numbers of cancer cells in vaginal secretions and the blood stream.

- detection of small numbers of cancer cells in vaginal secretions and the blood stream.

What mutations are we looking for?

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609−615.

In last year’s Update, we discussed the role of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project in endometrial cancer.4 For ovarian cancer, TCGA analyzed messenger RNA expression, microRNA expression, promoter methylation, and DNA copy number in 489 high-grade serous ovarian adenocarcinomas and the DNA sequences of exons from coding genes in 316 of these tumors.

Almost all tumors (96%) were characterized by mutations of the gene encoding TP53 in addition to statistically recurrent mutations in nine other loci, including NF1, BRCA1, BRCA2, RB1, and CDK12, although these were of low prevalence. Analyses also brought new insight regarding the survival impact of tumors containing BRCA1 or BRCA2 and CCNE1 mutations. Findings included NOTCH and FOXM1 signaling involvement in serous ovarian cancer pathophysiology as well as defective homologous recombination in approximately half of the tumors studied.

What this evidence means for practiceWith these mutations as our targets, we can screen vaginal secretions as well as blood for markers of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian and endometrial cancer cells detected in the vagina

Kinde I, Bettegowda C, Wang Y, et al. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(167):167ra4.

Erickson BK, Kinde I, Dobbin AC, et al. Detection of somatic TP53 mutations in tampons of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer [published online ahead of print October 2014]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5).

Ruth Graham, Papanicolaou’s cytology technician in the 1940s, first described ovarian cancer cells detected in vaginal/cervical cytology obtained from vaginal secretions.5 Current studies now demonstrate that we have technology capable of more than simple cytologic detection. We can isolate and evaluate these cancer cells in very small numbers.

Ovarian and endometrial cancer DNA identified in Pap specimenKinde and colleagues assembled a catalog of common mutations previously found in ovarian cancer as well as new data on 22 endometrial tumors. They tested 24 endometrial and 22 ovarian samples from patients with endometrial or ovarian cancers and confirmed that all 46 harbored at least some component of the common genetic changes in their catalog. Hypothesizing that the cancers likely shed cells from their surfaces, they sought to determine whether they could detect these cells among the cervical cells in a Pap smear.

These investigators used massively parallel sequencing to test DNA collected in modern liquid-based cytologic specimens for the same mutations found in the cancer cells. They found that 100% of the endometrial cancers and 41% of ovarian cancers were detectable by this method.

TP53 mutations in ovarian cancer cells detected in vaginally placed tamponWith similar technology, but a different collection method, Erickson and colleagues sought to detect tumor cells in the vagina of women with serous ovarian cancer by TP53 analysis of DNA samples collected via vaginal tampon.

Thirty-three women with pelvic masses suspicious for malignancy and scheduled to undergo diagnostic or therapeutic surgery were enrolled. Of the 25 patients who placed the tampon 8 to 12 hours prior to surgery; 13 had benign disease; three had nonovarian malignancies; and nine had serous adenocarcinoma of ovarian, tubal, or primary peritoneal origin. DNA from tumor specimens of eight patients with serous carcinoma and adequate DNA samples were analyzed for TP53 mutations. The corresponding DNA extracted from the tampon was then probed for the mutation identified in the tumor.

Mutational analysis of the tampon specimen DNA revealed no mutations in the tampon DNA of the three patients who had previously undergone tubal ligation, while mutations were observed in three of the five patients with intact tubes—producing a sensitivity of 60%. The fraction of mutant alleles in the tampon DNA was extremely low at 0.01% to 0.07%, requiring ultra-deep sequencing and increasing the importance of paired primary tumor specimens.

What this evidence means for practiceWhile sensitivity in a population of high-risk patients with intact tubes was found to be 60%, it is unclear what it would be in patients with less advanced disease. The ability of the test to detect mutations at exceptionally low limits is impressive; however, it increases the risk that a variant represents a sequencing error or a sample-to-sample contamination. This study is novel in its approach to diagnosis of ovarian cancer and is a stride toward screening, providing an opportunity to further validate the technology prior to widespread use and clinical application.

Circulating tumor cells—the future of cancer management?

Obermayr E, Castillo-Tong DC, Pils D, et al. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in patients with ovarian cancer improves their prognostic significance: a study of the OVCAD consortium. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):15−21.

Similar in concept to noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy, high circulating tumor cell (CTC) numbers have been correlated with aggressive disease, increased metastasis, and decreased time to relapse. As with cancer cells in vaginal secretions, CTCs also may provide an opportunity for early detection and targeted treatment.6

While many CTC studies have used epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)−based CTC detection, results have been found to be highly variable between tumor subtypes and phase of disease.7 Therefore, Obermayer and colleagues sought to identify novel markers for CTCs in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and elucidate their impact on outcome.

Details of the studyMatched ovarian cancer tissues and peripheral blood leukocytes of 35 patients underwent microarray analysis to identify novel CTC markers. Gene expression of the novel markers as well as EpCAM were analyzed using blood samples taken from 39 healthy females and from 216 patients with ovarian cancer before primary treatment and 6 months after adjuvant chemotherapy. Overexpression of at least one gene, compared with the healthy control group, was considered CTC positivity.

CTCs were detected in 24.5% of the baseline and 20.4% of the follow-up samples, of which two-thirds showed overexpression of the cyclophilin C gene (PPIC), and just a few by EpCAM overexpression. PPIC-positive CTCs during follow-up were detected significantly more often in the platinum resistant group, and indicated poor outcome even when controlling for classical prognostic parameters.

What this evidence means for practiceThe study authors found that molecular characterization of CTC is superior to CTC enumeration. Ultimately, CTC diagnostics may lead to earlier detection and more personalized treatment of ovarian cancer.

Therefore, this technology could have great impact on screening for and the survival of a large subset of patients with ovarian cancer. In addition, the cells obtained preoperatively could help assess the risk of malignancy in an ovarian mass prior to surgery, or even help in treatment planning, as we enter an era in which we have the ability to assess cancers for prognosis and features of treatment response.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected].

Ovarian cancer remains the deadliest gynecologic malignancy in the United States, with more than 22,000 women newly diagnosed and more than 14,000 deaths each year. We have made slow progress in terms of survival with new drugs and applications, such as intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with more aggressive cytoreductive efforts. Five-year survival rates have increased—from 36% to 44%—since the late 1970s.1 To make the leap from molecular genetics to successful screening, early diagnosis, and targeted treatment, we must first:

- Enhance our understanding of the changes that lead to ovarian cancer. Currently, malignant transformation of the fallopian tube epithelium is thought to result in high-grade papillary serous cancer.2 If this is indeed the pathologic origin of ovarian cancers, then early detection or even detection in the premalignant phase may be possible using tests of vaginal fluid. Are early detection, and even screening, possible and how would it effect treatment and survival?

- Develop new and powerful tools to detect molecular changes that might impact treatment and survival. Just a few years ago, initial sequencing of the human genome cost more than $100 million, but DNA sequencing technologies have evolved rapidly, with current estimates at less than a few thousand dollars per genome.3 Knowing the mutations responsible for an individual’s cancer would allow for targeted, individualized treatment plans. Would one patient benefit from neoadjuvant therapy while another needs primary surgical debulking?

In this article, we highlight the historical basis and recent developments in the field of ovarian cancer, focusing on:

- etiologic heterogeneity and molecular biology detection of small numbers of cancer cells in vaginal secretions and the blood stream.

- detection of small numbers of cancer cells in vaginal secretions and the blood stream.

What mutations are we looking for?

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609−615.

In last year’s Update, we discussed the role of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project in endometrial cancer.4 For ovarian cancer, TCGA analyzed messenger RNA expression, microRNA expression, promoter methylation, and DNA copy number in 489 high-grade serous ovarian adenocarcinomas and the DNA sequences of exons from coding genes in 316 of these tumors.

Almost all tumors (96%) were characterized by mutations of the gene encoding TP53 in addition to statistically recurrent mutations in nine other loci, including NF1, BRCA1, BRCA2, RB1, and CDK12, although these were of low prevalence. Analyses also brought new insight regarding the survival impact of tumors containing BRCA1 or BRCA2 and CCNE1 mutations. Findings included NOTCH and FOXM1 signaling involvement in serous ovarian cancer pathophysiology as well as defective homologous recombination in approximately half of the tumors studied.

What this evidence means for practiceWith these mutations as our targets, we can screen vaginal secretions as well as blood for markers of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian and endometrial cancer cells detected in the vagina

Kinde I, Bettegowda C, Wang Y, et al. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(167):167ra4.

Erickson BK, Kinde I, Dobbin AC, et al. Detection of somatic TP53 mutations in tampons of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer [published online ahead of print October 2014]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5).

Ruth Graham, Papanicolaou’s cytology technician in the 1940s, first described ovarian cancer cells detected in vaginal/cervical cytology obtained from vaginal secretions.5 Current studies now demonstrate that we have technology capable of more than simple cytologic detection. We can isolate and evaluate these cancer cells in very small numbers.

Ovarian and endometrial cancer DNA identified in Pap specimenKinde and colleagues assembled a catalog of common mutations previously found in ovarian cancer as well as new data on 22 endometrial tumors. They tested 24 endometrial and 22 ovarian samples from patients with endometrial or ovarian cancers and confirmed that all 46 harbored at least some component of the common genetic changes in their catalog. Hypothesizing that the cancers likely shed cells from their surfaces, they sought to determine whether they could detect these cells among the cervical cells in a Pap smear.

These investigators used massively parallel sequencing to test DNA collected in modern liquid-based cytologic specimens for the same mutations found in the cancer cells. They found that 100% of the endometrial cancers and 41% of ovarian cancers were detectable by this method.

TP53 mutations in ovarian cancer cells detected in vaginally placed tamponWith similar technology, but a different collection method, Erickson and colleagues sought to detect tumor cells in the vagina of women with serous ovarian cancer by TP53 analysis of DNA samples collected via vaginal tampon.

Thirty-three women with pelvic masses suspicious for malignancy and scheduled to undergo diagnostic or therapeutic surgery were enrolled. Of the 25 patients who placed the tampon 8 to 12 hours prior to surgery; 13 had benign disease; three had nonovarian malignancies; and nine had serous adenocarcinoma of ovarian, tubal, or primary peritoneal origin. DNA from tumor specimens of eight patients with serous carcinoma and adequate DNA samples were analyzed for TP53 mutations. The corresponding DNA extracted from the tampon was then probed for the mutation identified in the tumor.

Mutational analysis of the tampon specimen DNA revealed no mutations in the tampon DNA of the three patients who had previously undergone tubal ligation, while mutations were observed in three of the five patients with intact tubes—producing a sensitivity of 60%. The fraction of mutant alleles in the tampon DNA was extremely low at 0.01% to 0.07%, requiring ultra-deep sequencing and increasing the importance of paired primary tumor specimens.

What this evidence means for practiceWhile sensitivity in a population of high-risk patients with intact tubes was found to be 60%, it is unclear what it would be in patients with less advanced disease. The ability of the test to detect mutations at exceptionally low limits is impressive; however, it increases the risk that a variant represents a sequencing error or a sample-to-sample contamination. This study is novel in its approach to diagnosis of ovarian cancer and is a stride toward screening, providing an opportunity to further validate the technology prior to widespread use and clinical application.

Circulating tumor cells—the future of cancer management?

Obermayr E, Castillo-Tong DC, Pils D, et al. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in patients with ovarian cancer improves their prognostic significance: a study of the OVCAD consortium. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):15−21.

Similar in concept to noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy, high circulating tumor cell (CTC) numbers have been correlated with aggressive disease, increased metastasis, and decreased time to relapse. As with cancer cells in vaginal secretions, CTCs also may provide an opportunity for early detection and targeted treatment.6

While many CTC studies have used epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)−based CTC detection, results have been found to be highly variable between tumor subtypes and phase of disease.7 Therefore, Obermayer and colleagues sought to identify novel markers for CTCs in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and elucidate their impact on outcome.

Details of the studyMatched ovarian cancer tissues and peripheral blood leukocytes of 35 patients underwent microarray analysis to identify novel CTC markers. Gene expression of the novel markers as well as EpCAM were analyzed using blood samples taken from 39 healthy females and from 216 patients with ovarian cancer before primary treatment and 6 months after adjuvant chemotherapy. Overexpression of at least one gene, compared with the healthy control group, was considered CTC positivity.

CTCs were detected in 24.5% of the baseline and 20.4% of the follow-up samples, of which two-thirds showed overexpression of the cyclophilin C gene (PPIC), and just a few by EpCAM overexpression. PPIC-positive CTCs during follow-up were detected significantly more often in the platinum resistant group, and indicated poor outcome even when controlling for classical prognostic parameters.

What this evidence means for practiceThe study authors found that molecular characterization of CTC is superior to CTC enumeration. Ultimately, CTC diagnostics may lead to earlier detection and more personalized treatment of ovarian cancer.

Therefore, this technology could have great impact on screening for and the survival of a large subset of patients with ovarian cancer. In addition, the cells obtained preoperatively could help assess the risk of malignancy in an ovarian mass prior to surgery, or even help in treatment planning, as we enter an era in which we have the ability to assess cancers for prognosis and features of treatment response.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected].

1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29.

2. Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195(4):451–456.

3. Wetterstrand KA. DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP). http://www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts. Updated July 18, 2014. Accessed September 21, 2014.

4. Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, et al; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73.

5. Papanicolaou GN, Traut HF. The diagnostic value of vaginal smears in carcinoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1941;42:193–206.

6. Plaks V, Koopman CD, Werb Z. Cancer. Circulating tumor cells. Science. 2013;341(6151):1186–1188.

7. Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, et al. Anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies and the detection of circulating normal-like breast tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(1):61–66.

1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29.

2. Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195(4):451–456.

3. Wetterstrand KA. DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP). http://www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts. Updated July 18, 2014. Accessed September 21, 2014.

4. Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, et al; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73.

5. Papanicolaou GN, Traut HF. The diagnostic value of vaginal smears in carcinoma of the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1941;42:193–206.

6. Plaks V, Koopman CD, Werb Z. Cancer. Circulating tumor cells. Science. 2013;341(6151):1186–1188.

7. Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, et al. Anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies and the detection of circulating normal-like breast tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(1):61–66.

In this article:

What mutations are we looking for?

Ovarian and endometrial cancer cells detected in the vagina

Circulating tumor cells—the future of cancer management?

Laparoscopic dual-port contained power morcellation: An offered solution

Minimally invasive surgery utilizing laparoscopy for hysterectomy and myomectomy has become more common in women with gynecologic pathology. The benefits of this approach compared with laparotomy include decreased hospital stay, shorter recovery and, in experienced hands, significantly decreased morbidity.1–3

Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the United States—30% of which are performed laparoscopically.4 The primary indication for surgical intervention is uterine leiomyoma. This pathology accounts for 40% of procedures.5 During these surgeries, electromechanical morcellation (EMM), or open “power” morcellation, is commonly used to cut large tissue specimens into small pieces for removal and thereby avoid a larger incision. Concerns have been raised regarding the use of open power morcellation because of the risk of spreading an unrecognized malignancy.

Based on case reports and retrospective studies, the FDA issued a statement in April of this year discouraging the use of EMM for hysterectomy and myomectomy in women with uterine fibroids.6 The concern for inadvertent spread of an occult malignancy was the reasoning for the communication. Since that time, the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee held a public meeting in which the panel heard comments from patients, societies, and industry regarding their positions on the safety of laparoscopic power morcellation. The panel made several recommendations to the FDA but, at the time of this writing, the FDA has yet to issue a final decision.

Reaction to FDA’s action/inaction

The FDA’s “safety” communication was in response to the concern of a few who experienced a bad outcome believed to be secondary to open power morcellation of enlarged uteri or fibroid tumors. In its statement, the FDA estimated the risk of an occult sarcoma to be about 1 in 350 and stated that the risk of disseminating a sarcoma with morcellation is substantial. The FDA discouraged the use of the power morcellator during hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids.

Many organizations, including the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, issued less stringent statements regarding this technology.7–9 These organizations stated generally that there were too few data to make a statement at that time, advocated the collection of more data, and encouraged detailed informed consent to be given to patients undergoing these procedures.

However, the FDA’s statement, and lack of a timely follow-up to clarify the role of the laparoscopic power morcellator in gynecologic surgery, has effectively stopped the use of this technology in its current form. In fact, in response to the statement, Ethicon Endosurgery has discontinued the distribution and sales of its power morcellator and many institutions have severely or completely restricted the use of this technology. The reason for these restrictions is that the medicolegal consequences of an adverse outcome would be very difficult to defend given the current, albeit premature, recommendations of the FDA. This statement makes it difficult to defend any adverse outcome that may occur in association with the use of the laparoscopic power morcellator. Furthermore, this statement by the FDA has largely prevented the medical community at large from collecting additional useful information to allow for a data-driven determination.

Power morcellation is not without risks. In fact, we outline them in this article. However, we believe that minimally invasive surgery should be allowed to continue to advance. In that vein, here we describe a technique of dual-port contained EMM. This surgical approach is performed under direct visualization—which solves the problem of poor visualization that hinders other contained EMM techniques.

Risks of power morcellation

The potential for inadvertent spread of occult malignancy is not the only risk of open EMM. Reports of disseminated leiomyomatosis, adenomyosis, and endometriosis also have been described from inadvertent tissue dispersion during open EMM with resulting ectopic reperitonealization.10–12

The procedure itself is not without risks. A recent systematic review documented 55 major and minor complications from EMM.13 Multiple organ systems were injured including bowel, urinary, vascular, and others, resulting in six deaths from these complications. The investigators concluded that “laparoscopic morcellator–related injuries continue to increase and short- and long-term complications are emerging in both the medical literature and device-related databases. Surgeon inexperience is descriptively identified as one of the most common contributing factors.”

All of the above risks must be weighed against the known benefits of laparoscopic surgery and presented to each patient to assist in deciding which route of surgery should be performed.

Tissue extraction options for large specimens

Large specimen extraction options during gynecologic surgery include:

Vaginal coring. Delivery through the vagina or colpotomy during vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy uses the technique of coring, which has long been established in our field.

Manual morcellation through a single incision. Mini-laparotomy or laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) incisions provide another option of removal with manual morcellation after laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy. One study revealed that specimens up to 22 weeks in size can be placed in a large EndoCatch bag and morcellated extracorporeally by circumferentially coring with a scalpel.14

Contained power morcellation through a single port. Finally, the technique of contained EMM was recently described.15 This technique uses a large containment bag placed through a LESS incision with EMM being performed in an artificially created pneumoperitoneum. This technique isolates the specimen so that it can be morcellated without risk of exposing the patient to any malignant cells that might be unrecognized within the specimen.

Each of these techniques allows many patients to consider a minimally invasive option for their surgery. However, the ability to safely morcellate a very large uterus or myoma may be limited by visualization, and the experience of the surgeon is often critical in the successful performance of these procedures.16

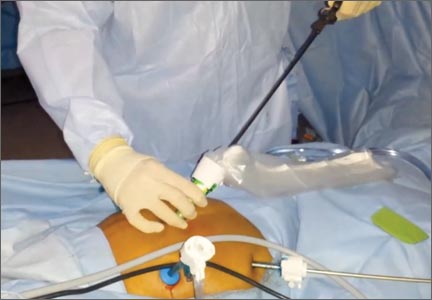

Therefore, at Washington Universitywe have developed a technique using dual ports, with isolation of the uterus or myomas to improve visualization and prevent spillage of malignant tumor or dispersion of other benign tissue.

Dual-port EMM: Technique, tips, and tricks

Our technique of dual-port contained EMM allows the removal of large fibroids or uteri much larger than 20 weeks in size safely under direct visualization through a 15-mm incision. The technique uses:

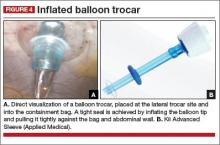

- Karl Storz Rotocut tissue morcellator with spacers (FIGURE 1)

- 15-mm trocar

- 5-mm balloon trocar

- 20320-inch containment bag (FIGURE 2).

Containment bag placement

Once the specimen is free, we place it to the right or left side of the abdomen. The 15-mm trocar is placed through the umbilicus while visualizing from a lateral trocar site. We then fan-fold the containment bag and introduce it through the 15-mm trocar, keeping the bag oriented with the opening anterior (FIGURE 3). The bag is then grasped at the opening along the drawstring with an atraumatic grasper.

Tip: Care must be taken when introducing the bag in order to avoid tearing or making a small hole in it.

The leading edge is then introduced into the deepest part of the pelvis, and the remainder of the bag (left outside of the abdomen) is then fed cephalad into the abdomen.

Once the bag is completely in the abdomen, we orient the bag with the opening as wide as possible. This allows placement of a very large specimen. Once the specimen is within the containment bag, the drawstring is pulled tight and the mouth of the bag is removed through the 15-mm trocar site at the umbilicus.

The abdominal lateral gas port is opened to allow the intra-abdominal pneumoperitoneum to escape. A 5-mm trocar is placed into the bag through the opening at the umbilicus and the containment bag is insufflated with carbon dioxide and the insufflation pressure is set to 30 mm. The laparoscope placed through this trocar allows the artificial pneumoperitoneum being created to be observed (VIDEO).

Tip: The containment bag covers the entire abdominal cavity and should be fully distended. If it does not distend fully, a hole in the bag may be present and the bag must be replaced.

At this point, we place a balloon trocar at the lateral trocar site and into the bag under direct visualization. The balloon tip is inflated and pulled up tightly against the bag and abdominal wall (FIGURE 4). This allows a tight seal so there is no gas leak or spillage of the morcellated specimen. The laparoscope is placed through this trocar and the insufflation tubing is moved to this port.

Morcellator insertion

The morcellator is introduced through the umbilicus under direct visualization using the short morcellator blade in most instances. Spacers are used to set the length of the morcellator within the containment bag. The tip of the morcellator should be approximately 3 cm to 4 cm within the bag but well away from the retroperitoneum. Remember, any bag will be cut easily by the morcellator and should be thought of as peritoneum only and not a tough barrier. Serious injuries could otherwise develop.

At this point, place the patient flat or out of Trendelenburg position. Morcellation may now proceed.

Tip: Morcellation is best performed with the morcellator perpendicular to the abdomen under direct visualization using a 30° laparoscope to optimize the view. Morcellation in this position uses gravity to facilitate “peeling” of the specimen during morcellation and allows for faster removal.

Before removing the morcellator, inspect the containment bag for any large pieces that may have been dispersed during the morcellation process and remove them. Once there are only small fragments remaining, remove the morcellator, allowing the carbon dioxide to escape. Deflate the balloon tip on the trocar.

Now the containment bag with the remaining specimen may be removed through the umbilicus, while simultaneously removing the balloon-tip trocar from the bag.

A safe minimally invasive approach

This technique has allowed us to safely remove specimens larger than 1,500 g while keeping them in a contained environment with no spill of tissue within the abdomen.

Tracking and adaptation needed

The FDA safety communication has severely limited the practice of morcellation in the minimally invasive gynecologic surgical setting. Many hospitals around the country have reacted by placing significant restrictions on the use of EMM or banned it outright. This action may reverse the national trend of increasing rates of laparoscopic hysterectomy and force many practitioners to return to open surgery.

Currently, it is unclear what the true risk of tissue extraction is whether it is performed via EMM or manually. Large national databases including the BOLD database from the Surgical Review Corporation, as well as AAGL, must be utilized to track these cases and their outcomes to guide therapy. In the meantime, in order to continue to offer a minimally invasive approach to gynecologic surgery, new techniques and instrumentation in the operating room will need to be modified to adapt to these new guidelines. This is vital to maintain or even reduce the rates of open hysterectomy and associated morbidity while diminishing the potential risks of inadvertent benign as well as malignant tissue dispersion with tissue extraction.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD003677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub4.

2. Wright KN, Jonsdottir GM, Jorgensen S, Shah N, Einarsson JI. Costs and outcomes of abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies. JSLS. 2012;16(4):519–524.

3. Wiser A, Holcroft CA, Tolandi T, Abenhaim HA. Abdominal versus laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign diseases: evaluation of morbidity and mortality among 465,798 cases. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10(2):117–122.

4. Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA. 2013;309(7):689–698.

5. Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):34.e1–e7.

6. U S Food and Drug Administration. Quantitative assessment of the prevalence of unsuspected uterine sarcoma in women undergoing treatment of uterine fibroids: Summary and key findings. Silver Spring, Maryland: FDA. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/UCM393589.pdf. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed August 19, 2014.

7. Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO). SGO Position Statement: Morcellation. https://www.sgo.org/newsroom/position-statements-2/morcellation. Published December 2013. Accessed March 1, 2014.

8. AAGL. Member Update: Disseminated leiomyosarcoma with power morcellation (Update #2). https://www.aagl.org/aaglnews/member-update-disseminated-leiomyosarcoma-with-power-morcellation-update-2/. Published July 11, 2014. Accessed August 19, 2014.