User login

Youth Exposure to Spironolactone in TikTok Videos

The short-form video hosting service TikTok has become a mainstream platform for individuals to share their ideas and educate the public regarding dermatologic diseases such as atopic dermatitis, alopecia, and acne. Users can create and post videos, leave comments, and indicate their interest in or approval of certain content by “liking” videos. In 2022, according to a Pew Research Center survey, approximately 67% of American teenagers aged 13 to 17 years reported using TikTok at least once.1 This population, along with the rest of its users, are increasing their use of TikTok to share information on dermatologic topics such as acne and isotretinoin.2,3 Spironolactone is an effective medication for acne but is not as widely known to the public as other acne medications such as retinoids, salicylic acid, and benzoyl peroxide. Being aware of youth exposure to media related to acne and spironolactone can help dermatologists understand gaps in education and refine their interactions with this patient population.

To gain insight into youth exposure to spironolactone, we conducted a search of TikTok on July 26, 2022, using the term #spironolactone to retrieve the top 50 videos identified by TikTok under the “Top” tab on spironolactone. Search results and the top 10 comments for each video were reviewed. The total number of views and likes for the top 50 videos were 6,735,992 and 851,856, respectively.

Videos were subdivided into educational information related to spironolactone and/or skin care (32% [16/50]), discussion of side effects of spironolactone (26% [13/50]), those with noticeable improvement of acne following treatment with spironolactone (20% [10/50]), recommendations to see a physician or dermatologist to treat acne (10% [5/50]), and other (12% [6/50]). Other takeaways from the top 50 videos included the following:

- Common side effects: irregular periods (10% [5/50]), frequent urination (8% [4/50]), dizziness/lightheadedness (8% [4/50]), and breast tenderness (6% [3/50])

- Longest reported use of spironolactone: 4 years, with complete acne resolution

- Average treatment length prior to noticeable results: 4 to 6 months, with the shortest being 1 month

- Reported dosages of spironolactone: ranged from 50 to 200 mg/d. The most common dosage was 100 mg/d (10% [5/50]). The lowest reported dosage was 50 mg/d (4% [2/50]), while the highest reported dosage was 200 mg/d (2% [1/50])

- Self-reported concurrent use of spironolactone with a combined oral contraceptive: drospirenoneTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol (4% [2/50]), norethindrone acetateTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol/ferrous fumarate (2% [1/50]), and norgestimateTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol (2% [1/50])

- Negative experiences with side effects and lack of acne improvement that led to treatment cessation: 8% (4/50).

Even though spironolactone is not as well-known as other treatments for acne, we found many TikTok users posting about, commenting on, and highlighting the relevance of this therapeutic option. There was no suggestion in any of the videos that spironolactone could be obtained without physician care and/or prescription. A prior report discussing youth sentiment of isotretinoin use on TikTok found that popular videos and videos with the most likes focused on the drug’s positive impact on acne improvement, while comments displayed heightened desires to learn more about isotretinoin and its side effects.3 Our analysis showed a similar response to spironolactone. In all videos showcasing the skin before and after treatment, there were noticeable improvements in the poster’s acne. Most of the video comments displayed a desire to learn more about spironolactone and its side effects. There also were many questions about time to noticeable results. In contrast to the study on isotretinoin,3 the most-liked spironolactone videos contained educational information about spironolactone and/or skin care rather than focusing solely on the impact of the drug on acne. Additionally, the study on isotretinoin found no videos mentioning the importance of seeing a dermatologist or other health care professional,3 while our search found multiple videos (10% [5/50]) on spironolactone that advised seeking physician help. In fact, several popular videos (8% [4/50]) were created by board-certified dermatologists who mainly focused on providing educational information. This difference in educational content may be attributed to spironolactone’s lesser-known function in treating acne. Furthermore, the comments suggested a growing interest in learning more about spironolactone as a treatment option for acne, specifically its mechanism of action and side effects.

With nearly 2 billion monthly active users globally and 94.1 million monthly active users in the United States (as of March 2023),4 TikTok is a popular social media platform that allows dermatologists to better understand youth sentiment on acne treatments such as spironolactone and isotretinoin and also provides an opportunity for medical education to reach a larger audience. This increased youth insight from TikTok can be utilized by dermatologists to make more informed decisions in developing patient-centered care that appeals to the adolescent population.

- Vogels EA, Gelles-Watnick R, Massarat N. Teens, social media and technology 2022. Published August 10, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

- Szeto MD, Mamo A, Afrin A, et al. Social media in dermatology and an overview of popular social media platforms. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2021;10:97-104. doi:10.1007/s13671-021-00343-4

- Galamgam J, Jia JL. “Accutane check”: insights into youth sentiment toward isotretinoin from a TikTok trend. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:980-981. doi:10.1111/pde.14660

- Aslam S. TikTok by the numbers: stats, demographics & fun facts. Omnicore website. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/tiktok-statistics/

The short-form video hosting service TikTok has become a mainstream platform for individuals to share their ideas and educate the public regarding dermatologic diseases such as atopic dermatitis, alopecia, and acne. Users can create and post videos, leave comments, and indicate their interest in or approval of certain content by “liking” videos. In 2022, according to a Pew Research Center survey, approximately 67% of American teenagers aged 13 to 17 years reported using TikTok at least once.1 This population, along with the rest of its users, are increasing their use of TikTok to share information on dermatologic topics such as acne and isotretinoin.2,3 Spironolactone is an effective medication for acne but is not as widely known to the public as other acne medications such as retinoids, salicylic acid, and benzoyl peroxide. Being aware of youth exposure to media related to acne and spironolactone can help dermatologists understand gaps in education and refine their interactions with this patient population.

To gain insight into youth exposure to spironolactone, we conducted a search of TikTok on July 26, 2022, using the term #spironolactone to retrieve the top 50 videos identified by TikTok under the “Top” tab on spironolactone. Search results and the top 10 comments for each video were reviewed. The total number of views and likes for the top 50 videos were 6,735,992 and 851,856, respectively.

Videos were subdivided into educational information related to spironolactone and/or skin care (32% [16/50]), discussion of side effects of spironolactone (26% [13/50]), those with noticeable improvement of acne following treatment with spironolactone (20% [10/50]), recommendations to see a physician or dermatologist to treat acne (10% [5/50]), and other (12% [6/50]). Other takeaways from the top 50 videos included the following:

- Common side effects: irregular periods (10% [5/50]), frequent urination (8% [4/50]), dizziness/lightheadedness (8% [4/50]), and breast tenderness (6% [3/50])

- Longest reported use of spironolactone: 4 years, with complete acne resolution

- Average treatment length prior to noticeable results: 4 to 6 months, with the shortest being 1 month

- Reported dosages of spironolactone: ranged from 50 to 200 mg/d. The most common dosage was 100 mg/d (10% [5/50]). The lowest reported dosage was 50 mg/d (4% [2/50]), while the highest reported dosage was 200 mg/d (2% [1/50])

- Self-reported concurrent use of spironolactone with a combined oral contraceptive: drospirenoneTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol (4% [2/50]), norethindrone acetateTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol/ferrous fumarate (2% [1/50]), and norgestimateTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol (2% [1/50])

- Negative experiences with side effects and lack of acne improvement that led to treatment cessation: 8% (4/50).

Even though spironolactone is not as well-known as other treatments for acne, we found many TikTok users posting about, commenting on, and highlighting the relevance of this therapeutic option. There was no suggestion in any of the videos that spironolactone could be obtained without physician care and/or prescription. A prior report discussing youth sentiment of isotretinoin use on TikTok found that popular videos and videos with the most likes focused on the drug’s positive impact on acne improvement, while comments displayed heightened desires to learn more about isotretinoin and its side effects.3 Our analysis showed a similar response to spironolactone. In all videos showcasing the skin before and after treatment, there were noticeable improvements in the poster’s acne. Most of the video comments displayed a desire to learn more about spironolactone and its side effects. There also were many questions about time to noticeable results. In contrast to the study on isotretinoin,3 the most-liked spironolactone videos contained educational information about spironolactone and/or skin care rather than focusing solely on the impact of the drug on acne. Additionally, the study on isotretinoin found no videos mentioning the importance of seeing a dermatologist or other health care professional,3 while our search found multiple videos (10% [5/50]) on spironolactone that advised seeking physician help. In fact, several popular videos (8% [4/50]) were created by board-certified dermatologists who mainly focused on providing educational information. This difference in educational content may be attributed to spironolactone’s lesser-known function in treating acne. Furthermore, the comments suggested a growing interest in learning more about spironolactone as a treatment option for acne, specifically its mechanism of action and side effects.

With nearly 2 billion monthly active users globally and 94.1 million monthly active users in the United States (as of March 2023),4 TikTok is a popular social media platform that allows dermatologists to better understand youth sentiment on acne treatments such as spironolactone and isotretinoin and also provides an opportunity for medical education to reach a larger audience. This increased youth insight from TikTok can be utilized by dermatologists to make more informed decisions in developing patient-centered care that appeals to the adolescent population.

The short-form video hosting service TikTok has become a mainstream platform for individuals to share their ideas and educate the public regarding dermatologic diseases such as atopic dermatitis, alopecia, and acne. Users can create and post videos, leave comments, and indicate their interest in or approval of certain content by “liking” videos. In 2022, according to a Pew Research Center survey, approximately 67% of American teenagers aged 13 to 17 years reported using TikTok at least once.1 This population, along with the rest of its users, are increasing their use of TikTok to share information on dermatologic topics such as acne and isotretinoin.2,3 Spironolactone is an effective medication for acne but is not as widely known to the public as other acne medications such as retinoids, salicylic acid, and benzoyl peroxide. Being aware of youth exposure to media related to acne and spironolactone can help dermatologists understand gaps in education and refine their interactions with this patient population.

To gain insight into youth exposure to spironolactone, we conducted a search of TikTok on July 26, 2022, using the term #spironolactone to retrieve the top 50 videos identified by TikTok under the “Top” tab on spironolactone. Search results and the top 10 comments for each video were reviewed. The total number of views and likes for the top 50 videos were 6,735,992 and 851,856, respectively.

Videos were subdivided into educational information related to spironolactone and/or skin care (32% [16/50]), discussion of side effects of spironolactone (26% [13/50]), those with noticeable improvement of acne following treatment with spironolactone (20% [10/50]), recommendations to see a physician or dermatologist to treat acne (10% [5/50]), and other (12% [6/50]). Other takeaways from the top 50 videos included the following:

- Common side effects: irregular periods (10% [5/50]), frequent urination (8% [4/50]), dizziness/lightheadedness (8% [4/50]), and breast tenderness (6% [3/50])

- Longest reported use of spironolactone: 4 years, with complete acne resolution

- Average treatment length prior to noticeable results: 4 to 6 months, with the shortest being 1 month

- Reported dosages of spironolactone: ranged from 50 to 200 mg/d. The most common dosage was 100 mg/d (10% [5/50]). The lowest reported dosage was 50 mg/d (4% [2/50]), while the highest reported dosage was 200 mg/d (2% [1/50])

- Self-reported concurrent use of spironolactone with a combined oral contraceptive: drospirenoneTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol (4% [2/50]), norethindrone acetateTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol/ferrous fumarate (2% [1/50]), and norgestimateTimes New Roman–ethinyl estradiol (2% [1/50])

- Negative experiences with side effects and lack of acne improvement that led to treatment cessation: 8% (4/50).

Even though spironolactone is not as well-known as other treatments for acne, we found many TikTok users posting about, commenting on, and highlighting the relevance of this therapeutic option. There was no suggestion in any of the videos that spironolactone could be obtained without physician care and/or prescription. A prior report discussing youth sentiment of isotretinoin use on TikTok found that popular videos and videos with the most likes focused on the drug’s positive impact on acne improvement, while comments displayed heightened desires to learn more about isotretinoin and its side effects.3 Our analysis showed a similar response to spironolactone. In all videos showcasing the skin before and after treatment, there were noticeable improvements in the poster’s acne. Most of the video comments displayed a desire to learn more about spironolactone and its side effects. There also were many questions about time to noticeable results. In contrast to the study on isotretinoin,3 the most-liked spironolactone videos contained educational information about spironolactone and/or skin care rather than focusing solely on the impact of the drug on acne. Additionally, the study on isotretinoin found no videos mentioning the importance of seeing a dermatologist or other health care professional,3 while our search found multiple videos (10% [5/50]) on spironolactone that advised seeking physician help. In fact, several popular videos (8% [4/50]) were created by board-certified dermatologists who mainly focused on providing educational information. This difference in educational content may be attributed to spironolactone’s lesser-known function in treating acne. Furthermore, the comments suggested a growing interest in learning more about spironolactone as a treatment option for acne, specifically its mechanism of action and side effects.

With nearly 2 billion monthly active users globally and 94.1 million monthly active users in the United States (as of March 2023),4 TikTok is a popular social media platform that allows dermatologists to better understand youth sentiment on acne treatments such as spironolactone and isotretinoin and also provides an opportunity for medical education to reach a larger audience. This increased youth insight from TikTok can be utilized by dermatologists to make more informed decisions in developing patient-centered care that appeals to the adolescent population.

- Vogels EA, Gelles-Watnick R, Massarat N. Teens, social media and technology 2022. Published August 10, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

- Szeto MD, Mamo A, Afrin A, et al. Social media in dermatology and an overview of popular social media platforms. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2021;10:97-104. doi:10.1007/s13671-021-00343-4

- Galamgam J, Jia JL. “Accutane check”: insights into youth sentiment toward isotretinoin from a TikTok trend. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:980-981. doi:10.1111/pde.14660

- Aslam S. TikTok by the numbers: stats, demographics & fun facts. Omnicore website. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/tiktok-statistics/

- Vogels EA, Gelles-Watnick R, Massarat N. Teens, social media and technology 2022. Published August 10, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

- Szeto MD, Mamo A, Afrin A, et al. Social media in dermatology and an overview of popular social media platforms. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2021;10:97-104. doi:10.1007/s13671-021-00343-4

- Galamgam J, Jia JL. “Accutane check”: insights into youth sentiment toward isotretinoin from a TikTok trend. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:980-981. doi:10.1111/pde.14660

- Aslam S. TikTok by the numbers: stats, demographics & fun facts. Omnicore website. February 27, 2023. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.omnicoreagency.com/tiktok-statistics/

Crusted Papules on the Bilateral Helices and Lobules

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

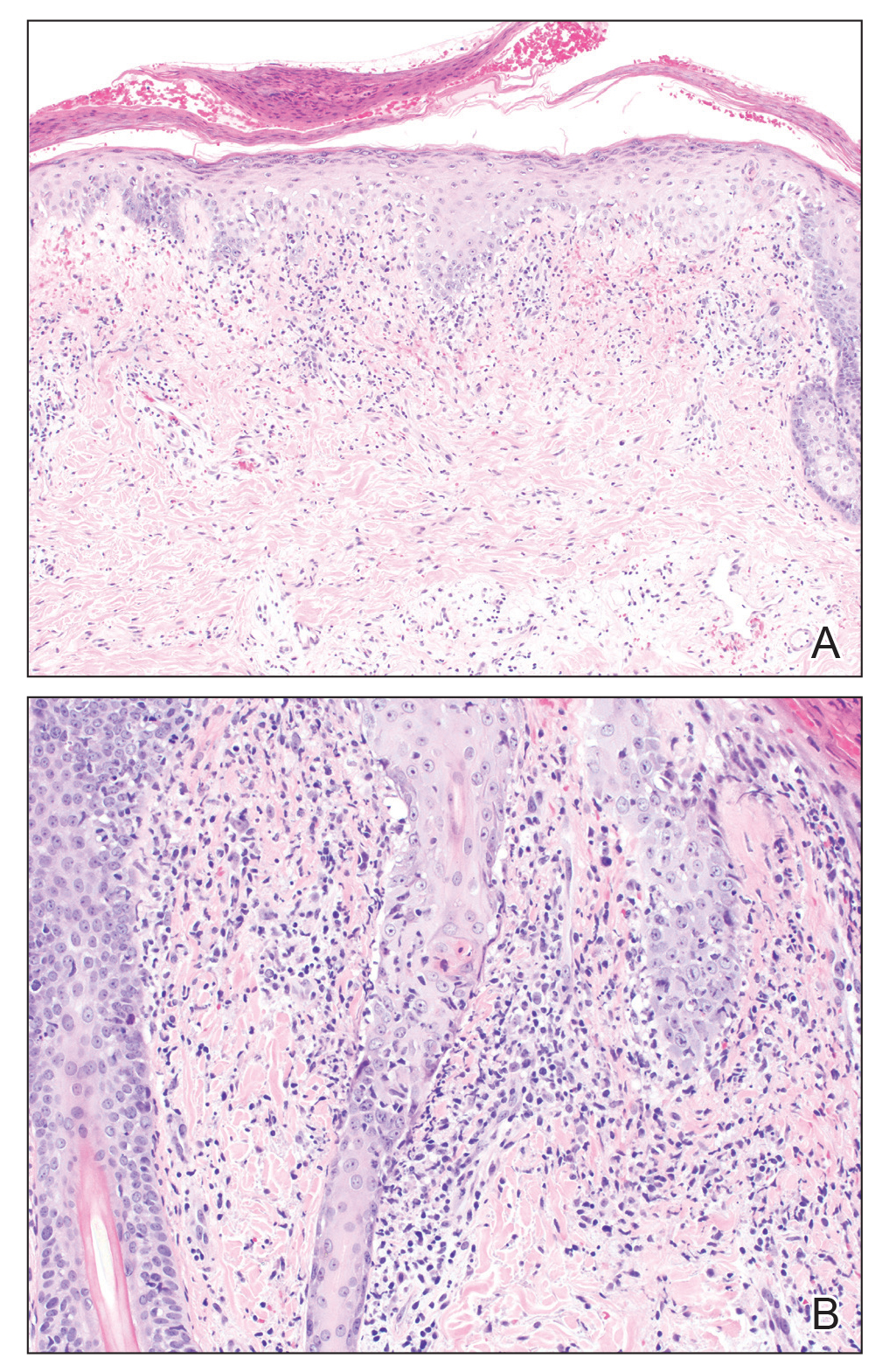

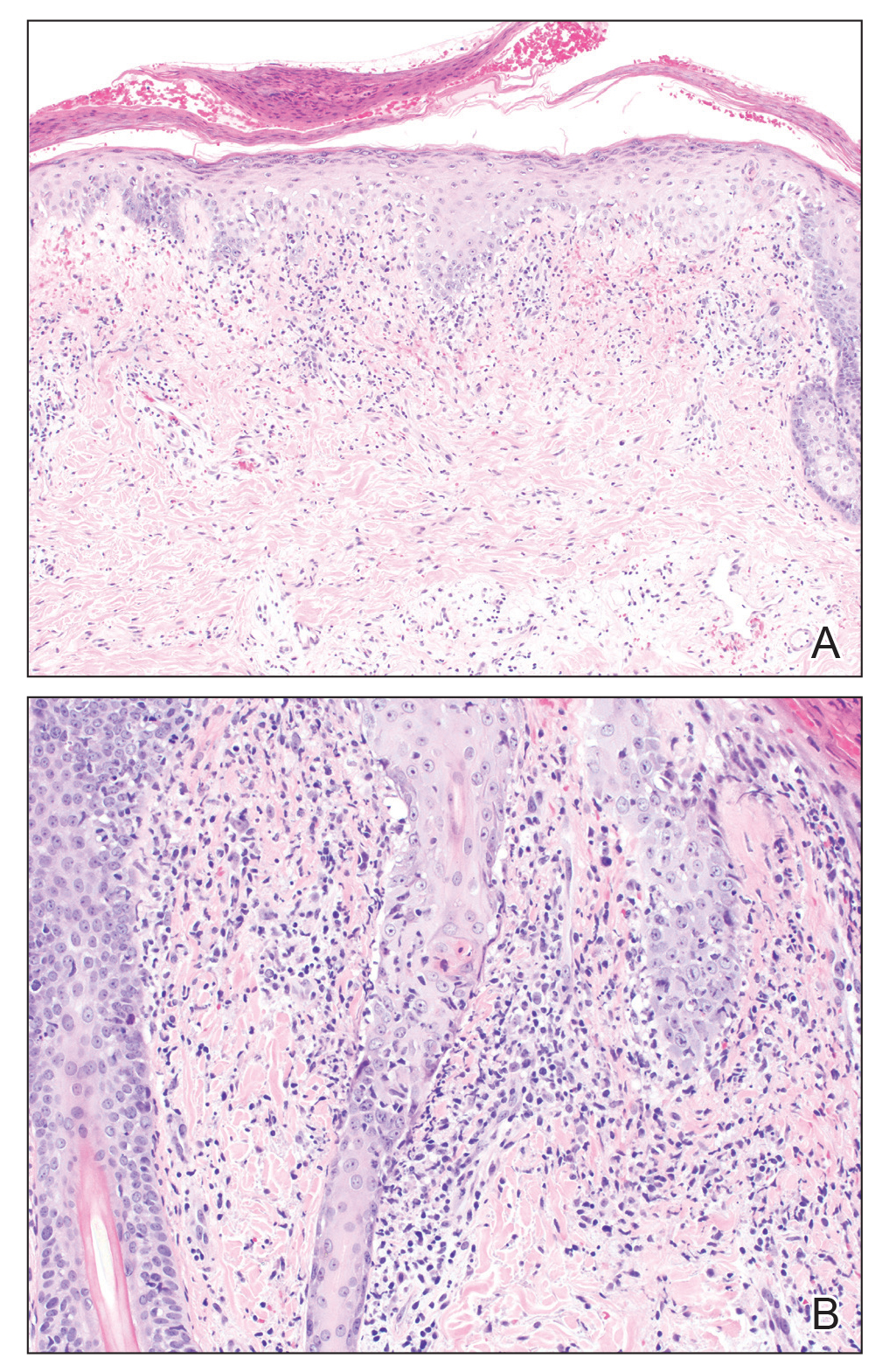

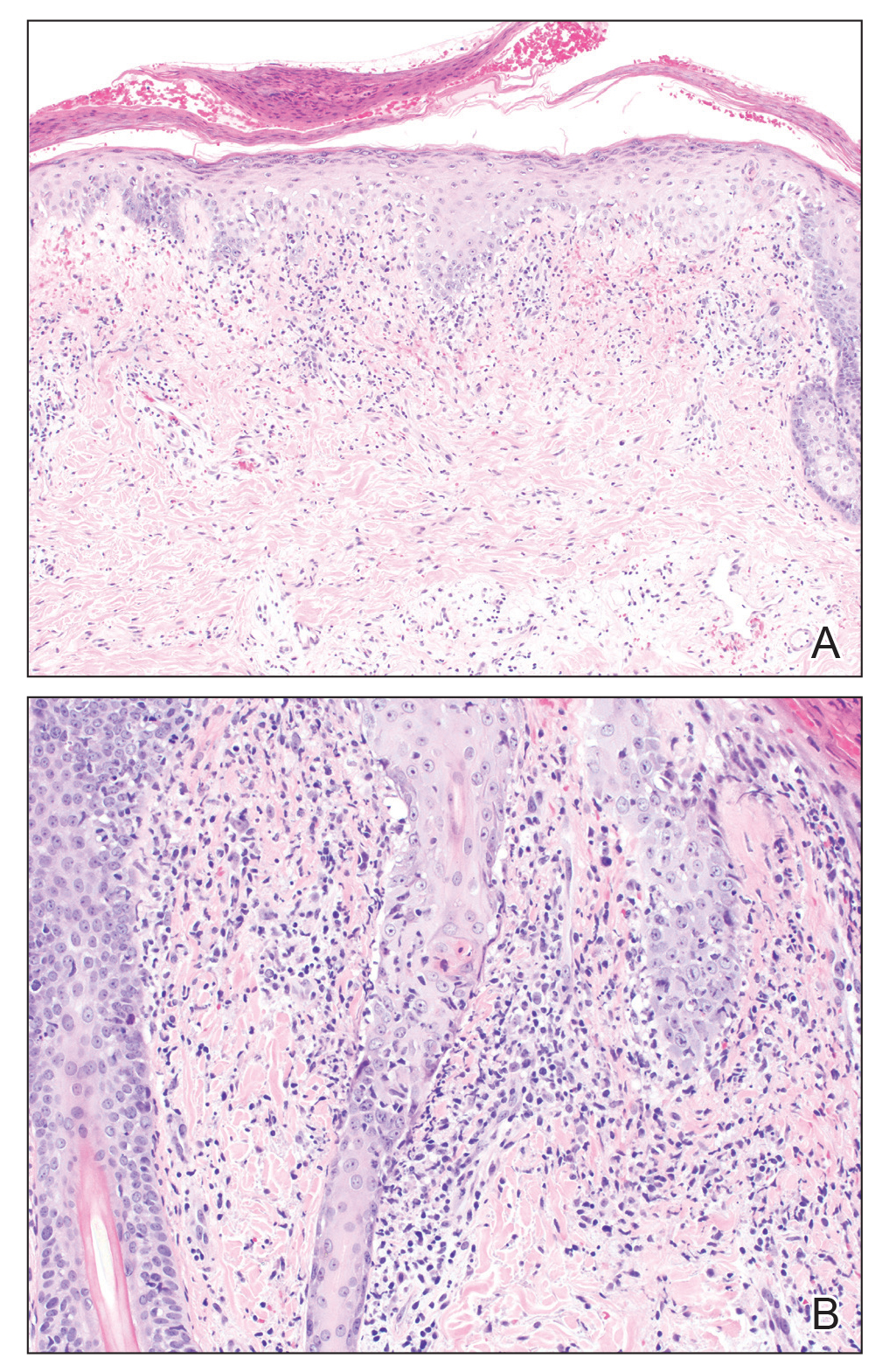

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

A healthy 42-year-old Japanese man presented with painful lymphadenopathy and fevers of 1 month’s duration as well as a pruritic rash and bilateral ear redness and crusting of 1 week’s duration. He initially was seen at an outside facility and was treated with antibiotics and supportive care for cervical adenitis. During clinical evaluation, he denied joint pain, photosensitivity, and oral lesions. His medical and family history were noncontributory. Although he reported recent travel to multiple countries, he denied exposure to animals, ticks, or sick individuals. Physical examination revealed erythematous blanching papules on the nose and cheeks (top) as well as crusted papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral helices and lobules (bottom).