User login

Zosteriform Eruption on the Chest and Abdomen

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Cutaneous Metastatic Mesothelioma

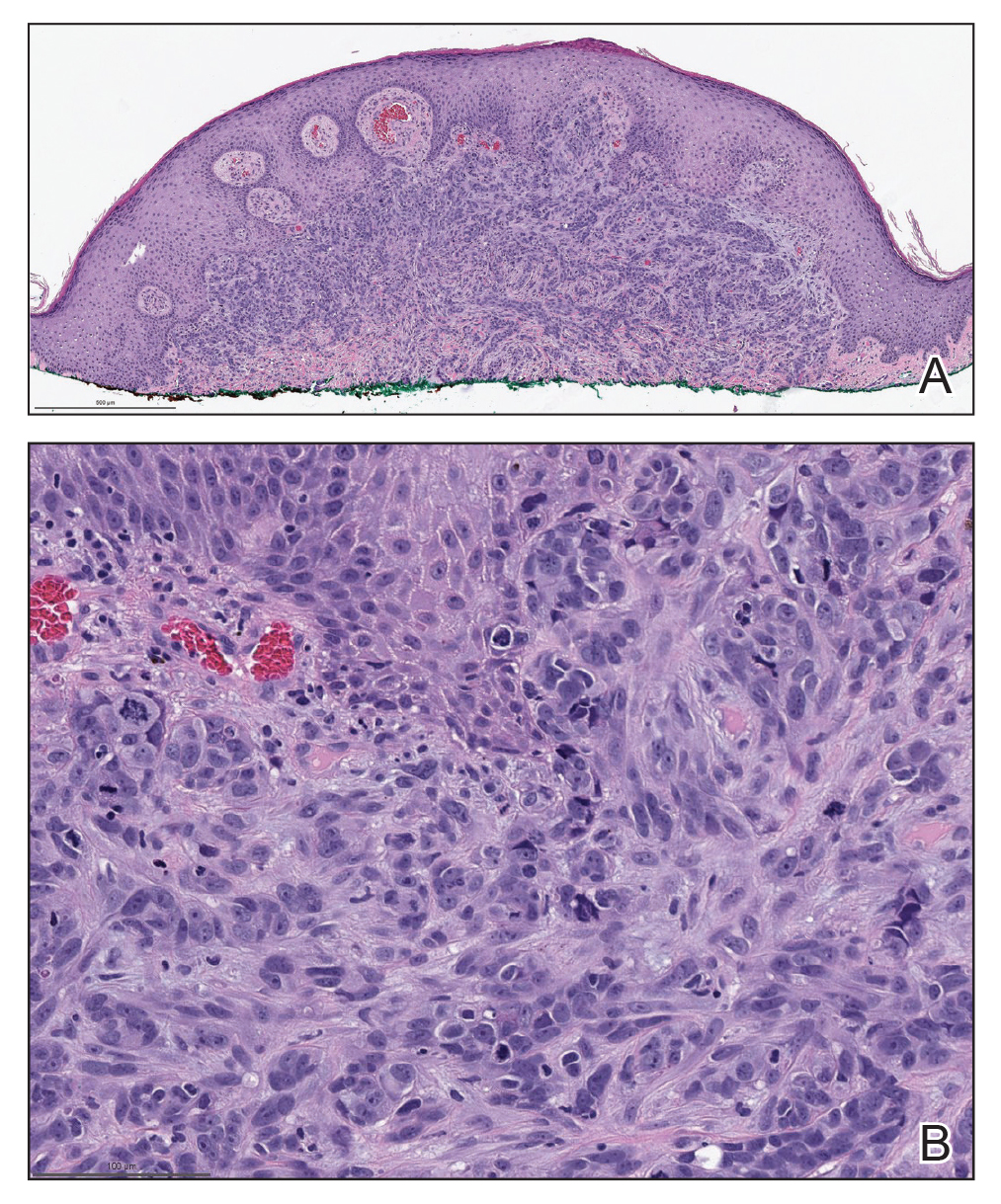

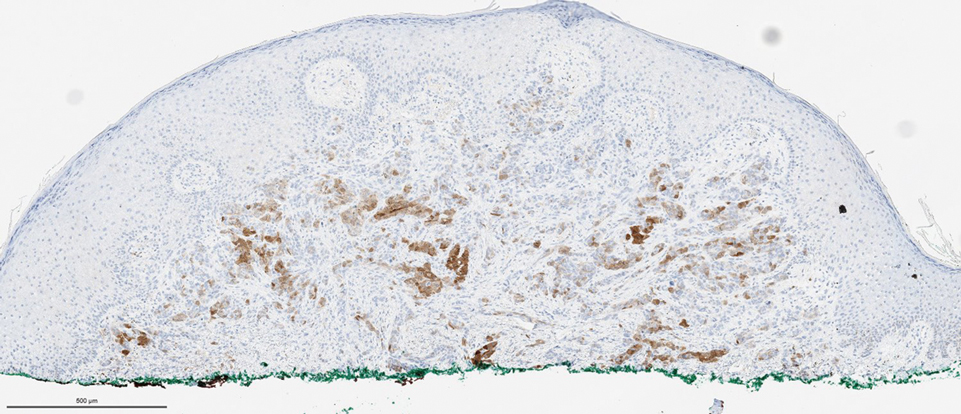

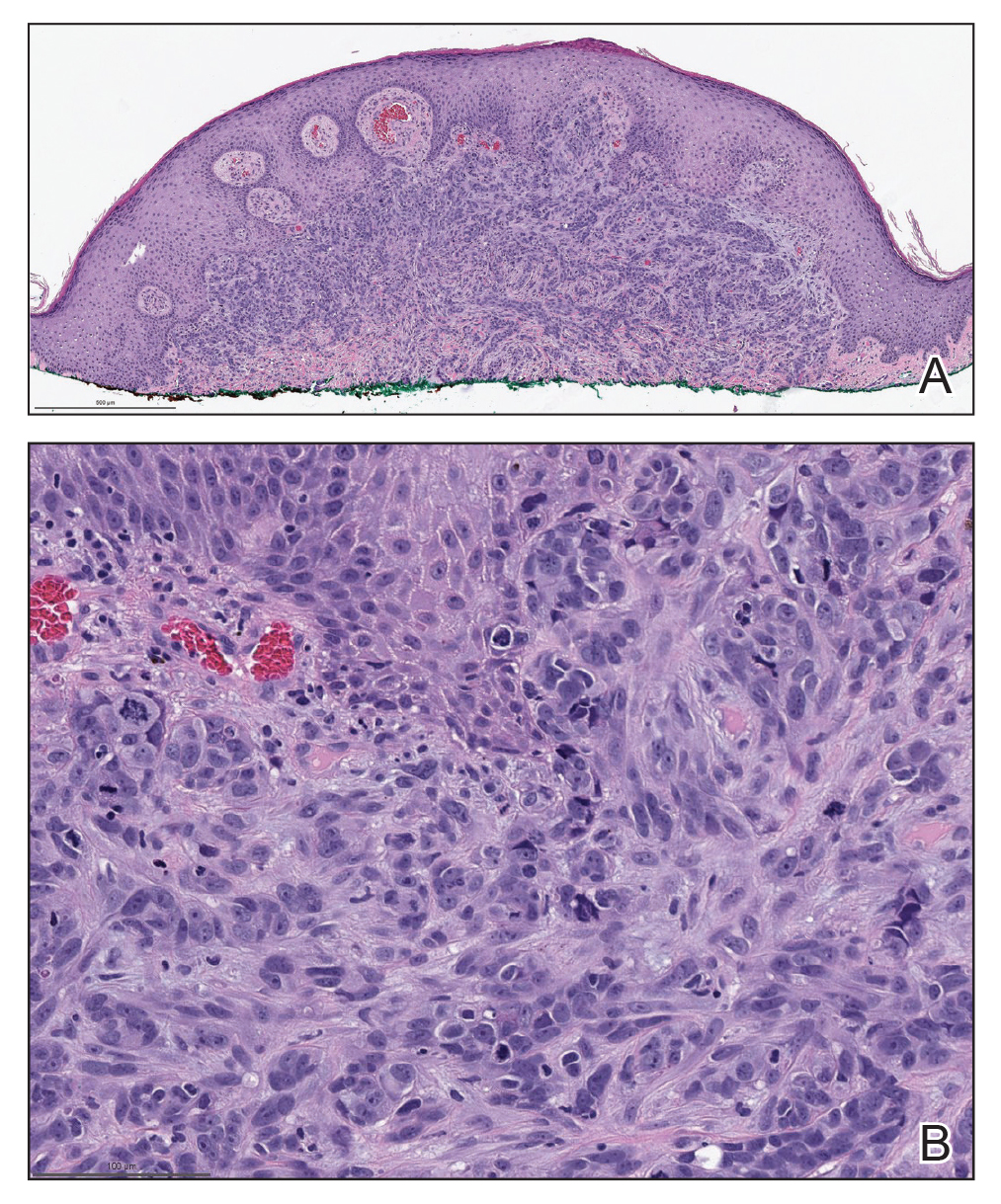

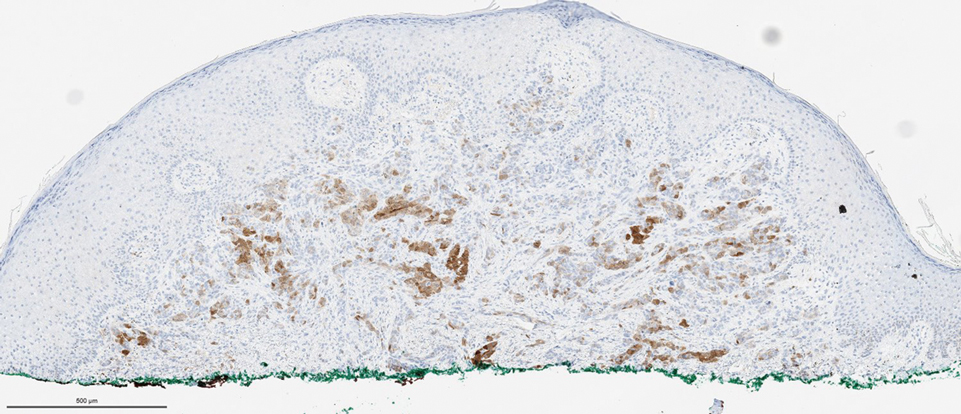

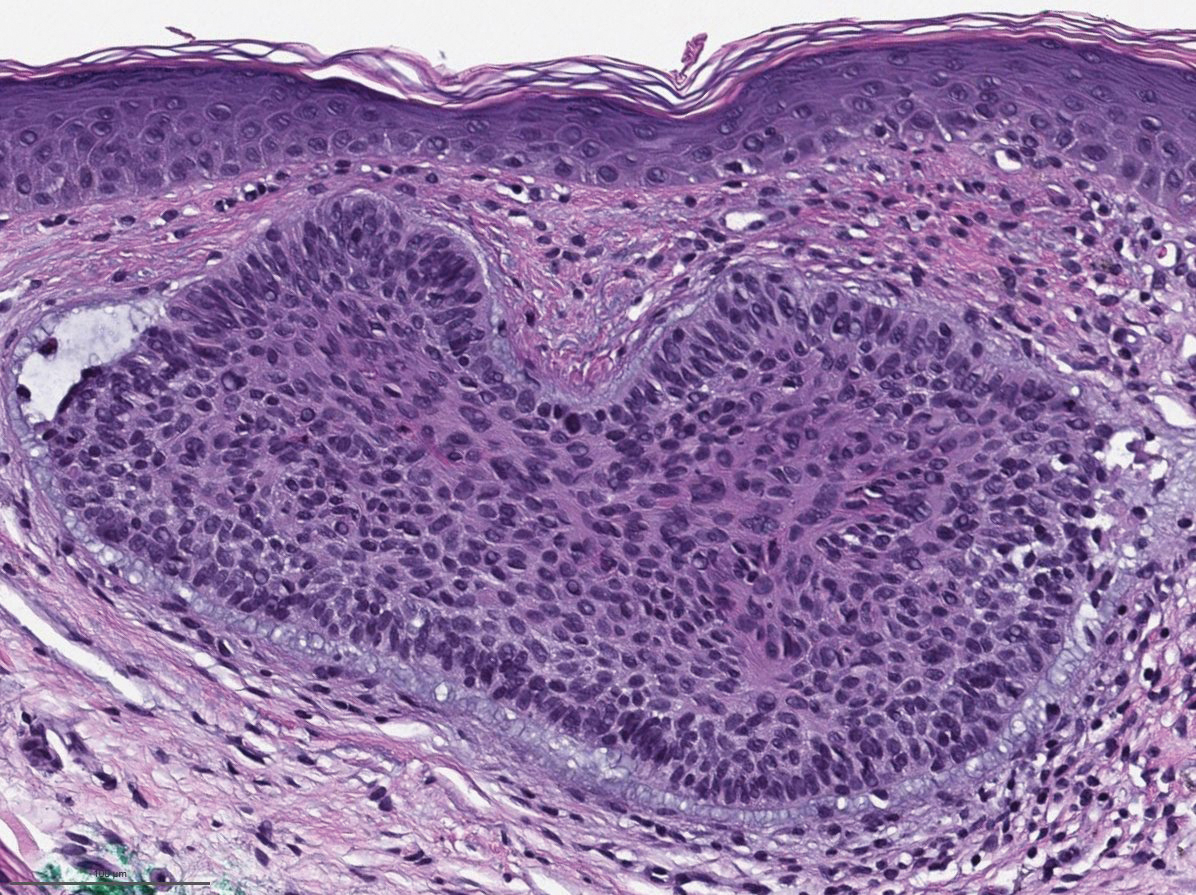

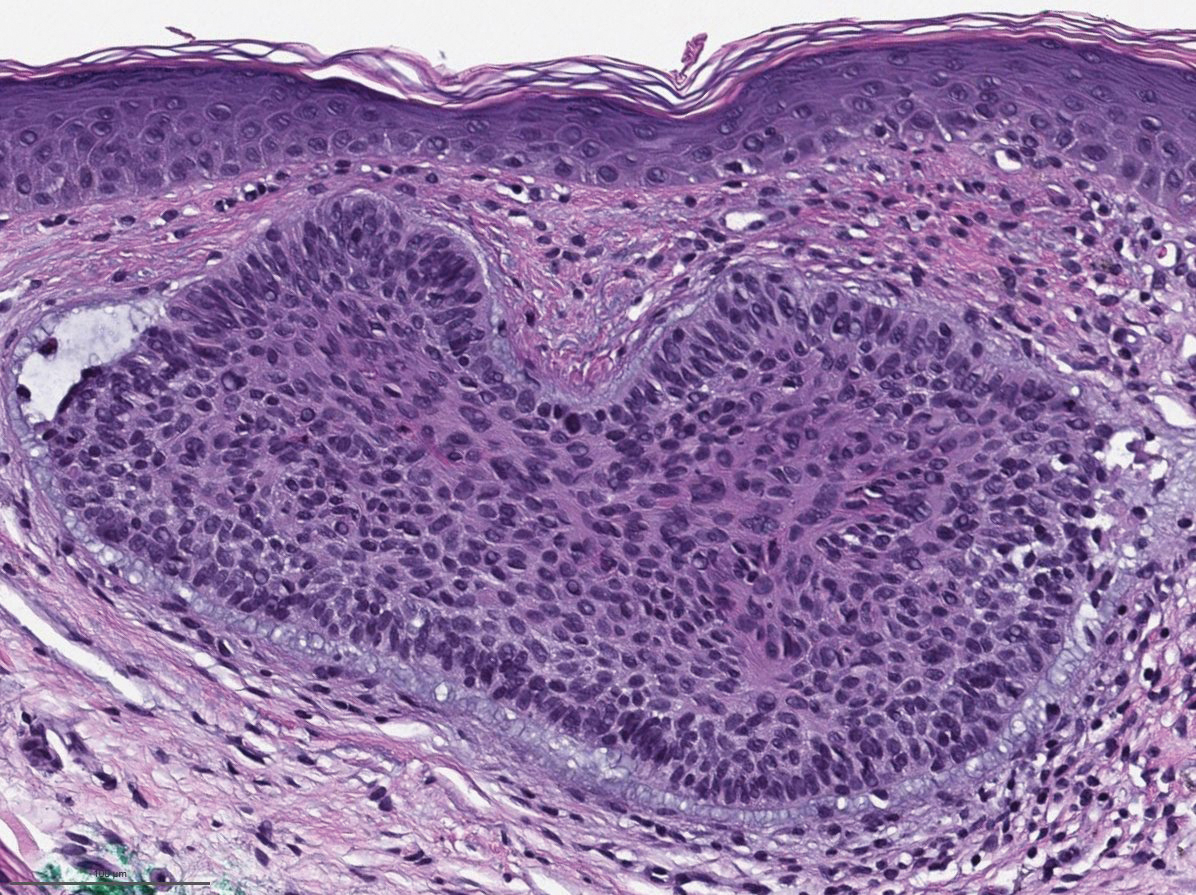

Biopsies of the larger erythematous papules revealed an infiltrate of atypical tumor cells with mitoses (Figure 1) that were immunoreactive for calretinin (Figure 2) and lacked nuclear BRCA1 associated protein-1, BAP1, expression (not shown). The patient’s prior mesothelioma was re-reviewed, and the cutaneous tumor cells were similar to the primary mesothelioma. A diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic mesothelioma (CMM) was made.

Mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm arising from the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, and tunica vaginalis,1 with an estimated annual incidence of 2500 cases.2 The predominant risk factor for the development of pleural mesothelioma is asbestos exposure, which has been identified in up to 90% of cases. Mesothelioma can give rise to local and less frequently distant hematogenous metastases. Cutaneous involvement of mesothelioma is rare.3 More than 80% of CMM cases are attributed to seeding the skin at procedure sites or by direct infiltration of scars. Distant CMM is rare and typically presents as subcutaneous nodules.4 Few cases of inflammatory CMM have been published,1,4,5 with even fewer mimicking herpes zoster infection (HZI), as seen in our patient.

The most specific stain for mesothelioma is calretinin, which strongly and diffusely stains both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Other markers include Wilms tumor 1, cytokeratin 5/6, thrombomodulin, and HBME-1. Immunohistochemistry to detect the loss of BAP1 staining in the nucleus is important for differentiating between mesothelioma and mesothelial hyperplasia.3

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of patients with internal malignant disease. Most commonly, cutaneous metastases present as cutaneous nodules, though other reported inflammatory presentations include erysipeloides, generalized erythematous patches, telangiectasia, and zosteriform distributions.6 Zosteriform distributions are particularly rare and most commonly are due to breast carcinomas or lymphomas. The mechanism of zosteriform metastasis is unknown, but theories include tumoral spread along vessels, invasion of the thoracic perineural sheaths, localized spread of tumor cells from a surgical site, or a Koebner-like reaction at the site of an existing HZI. Regardless of primary tumor type or presentation, cutaneous metastasis is a poor prognostic sign, with survival rates varying based on primary tumor type.7

Other differential diagnoses include herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis, radiation recall dermatitis, cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, and zosteriform lichen planus, all of which have been reported after HZI.8-10 Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis typically presents weeks to years after acute HZI with erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques at the site of the prior HZI. A biopsy reveals interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and multinucleated giant cells.8 Radiation recall dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory reaction limited to regions of prior radiation exposure after the administration of a triggering medication. Radiation recall dermatitis can present days to many years after the completion of treatment.9 Although the eruption in our patient was at the site of prior radiation, the pathologic and clinical presentation was not consistent with radiation recall dermatitis. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that may present as either solitary or numerous papules, plaques, or nodules and has been reported to occur after HZI. Biopsy reveals a diffuse dermal histiocytic infiltration with plasma cells and lymphocytes. In contrast to metastatic disease, mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare in cutaneous RosaiDorfman disease.11 Lichen planus is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology presenting as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic papules12 that may present in a zosteriform pattern.13

Although it is uncommon, metastatic spread should be considered in patients with known malignancy presenting with zosteriform eruptions.2 Our patient remained on treatment with immunotherapy, as he was unable to undergo additional radiation and had failed multiple other lines of therapy. He died 3 months after presentation.

- Klebanov N, Reddy BY, Husain S, et al. Cutaneous presentation of mesothelioma with a sarcomatoid transformation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:378-382.

- Patel SC, Dowell JE. Modern management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer (Auckl). 2016;7:63-72.

- Ward RE, Ali SA, Kuhar M. Epithelioid malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:1057-1063.

- Prieto VG, Kenet BJ, Varghese M. Malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin, presenting as inflammatory carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:261-265.

- Gaudy-Marqueste C, Dales JP, Collet-Villette AM, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of pleural mesothelioma: two cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:455-459.

- Chiang A, Salomon N, Gaikwad R, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis mimicking herpes zoster rash. IDCases. 2018;12:167-168.

- Thomaidou E, Armon G, Klapholz L, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:734-736.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Carrasco L, Pastor MA, Izquierdo MJ, et al. Drug eruption secondary to acyclovir with recall phenomenon in a dermatome previously affected by herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:132-134.

- Malviya N, Marzuka A, Maamed-Tayeb M, et al. Cutaneous involvement of pre-existing Rosai-Dorfman disease via post-herpetic isotopic response. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1211-1214.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Fink-Puches R, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Smolle J. Zosteriform lichen planus. Dermatology. 1996;192:375-377.

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Cutaneous Metastatic Mesothelioma

Biopsies of the larger erythematous papules revealed an infiltrate of atypical tumor cells with mitoses (Figure 1) that were immunoreactive for calretinin (Figure 2) and lacked nuclear BRCA1 associated protein-1, BAP1, expression (not shown). The patient’s prior mesothelioma was re-reviewed, and the cutaneous tumor cells were similar to the primary mesothelioma. A diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic mesothelioma (CMM) was made.

Mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm arising from the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, and tunica vaginalis,1 with an estimated annual incidence of 2500 cases.2 The predominant risk factor for the development of pleural mesothelioma is asbestos exposure, which has been identified in up to 90% of cases. Mesothelioma can give rise to local and less frequently distant hematogenous metastases. Cutaneous involvement of mesothelioma is rare.3 More than 80% of CMM cases are attributed to seeding the skin at procedure sites or by direct infiltration of scars. Distant CMM is rare and typically presents as subcutaneous nodules.4 Few cases of inflammatory CMM have been published,1,4,5 with even fewer mimicking herpes zoster infection (HZI), as seen in our patient.

The most specific stain for mesothelioma is calretinin, which strongly and diffusely stains both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Other markers include Wilms tumor 1, cytokeratin 5/6, thrombomodulin, and HBME-1. Immunohistochemistry to detect the loss of BAP1 staining in the nucleus is important for differentiating between mesothelioma and mesothelial hyperplasia.3

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of patients with internal malignant disease. Most commonly, cutaneous metastases present as cutaneous nodules, though other reported inflammatory presentations include erysipeloides, generalized erythematous patches, telangiectasia, and zosteriform distributions.6 Zosteriform distributions are particularly rare and most commonly are due to breast carcinomas or lymphomas. The mechanism of zosteriform metastasis is unknown, but theories include tumoral spread along vessels, invasion of the thoracic perineural sheaths, localized spread of tumor cells from a surgical site, or a Koebner-like reaction at the site of an existing HZI. Regardless of primary tumor type or presentation, cutaneous metastasis is a poor prognostic sign, with survival rates varying based on primary tumor type.7

Other differential diagnoses include herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis, radiation recall dermatitis, cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, and zosteriform lichen planus, all of which have been reported after HZI.8-10 Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis typically presents weeks to years after acute HZI with erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques at the site of the prior HZI. A biopsy reveals interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and multinucleated giant cells.8 Radiation recall dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory reaction limited to regions of prior radiation exposure after the administration of a triggering medication. Radiation recall dermatitis can present days to many years after the completion of treatment.9 Although the eruption in our patient was at the site of prior radiation, the pathologic and clinical presentation was not consistent with radiation recall dermatitis. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that may present as either solitary or numerous papules, plaques, or nodules and has been reported to occur after HZI. Biopsy reveals a diffuse dermal histiocytic infiltration with plasma cells and lymphocytes. In contrast to metastatic disease, mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare in cutaneous RosaiDorfman disease.11 Lichen planus is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology presenting as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic papules12 that may present in a zosteriform pattern.13

Although it is uncommon, metastatic spread should be considered in patients with known malignancy presenting with zosteriform eruptions.2 Our patient remained on treatment with immunotherapy, as he was unable to undergo additional radiation and had failed multiple other lines of therapy. He died 3 months after presentation.

THE DIAGNOSIS:

Cutaneous Metastatic Mesothelioma

Biopsies of the larger erythematous papules revealed an infiltrate of atypical tumor cells with mitoses (Figure 1) that were immunoreactive for calretinin (Figure 2) and lacked nuclear BRCA1 associated protein-1, BAP1, expression (not shown). The patient’s prior mesothelioma was re-reviewed, and the cutaneous tumor cells were similar to the primary mesothelioma. A diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic mesothelioma (CMM) was made.

Mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm arising from the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, and tunica vaginalis,1 with an estimated annual incidence of 2500 cases.2 The predominant risk factor for the development of pleural mesothelioma is asbestos exposure, which has been identified in up to 90% of cases. Mesothelioma can give rise to local and less frequently distant hematogenous metastases. Cutaneous involvement of mesothelioma is rare.3 More than 80% of CMM cases are attributed to seeding the skin at procedure sites or by direct infiltration of scars. Distant CMM is rare and typically presents as subcutaneous nodules.4 Few cases of inflammatory CMM have been published,1,4,5 with even fewer mimicking herpes zoster infection (HZI), as seen in our patient.

The most specific stain for mesothelioma is calretinin, which strongly and diffusely stains both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Other markers include Wilms tumor 1, cytokeratin 5/6, thrombomodulin, and HBME-1. Immunohistochemistry to detect the loss of BAP1 staining in the nucleus is important for differentiating between mesothelioma and mesothelial hyperplasia.3

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of patients with internal malignant disease. Most commonly, cutaneous metastases present as cutaneous nodules, though other reported inflammatory presentations include erysipeloides, generalized erythematous patches, telangiectasia, and zosteriform distributions.6 Zosteriform distributions are particularly rare and most commonly are due to breast carcinomas or lymphomas. The mechanism of zosteriform metastasis is unknown, but theories include tumoral spread along vessels, invasion of the thoracic perineural sheaths, localized spread of tumor cells from a surgical site, or a Koebner-like reaction at the site of an existing HZI. Regardless of primary tumor type or presentation, cutaneous metastasis is a poor prognostic sign, with survival rates varying based on primary tumor type.7

Other differential diagnoses include herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis, radiation recall dermatitis, cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease, and zosteriform lichen planus, all of which have been reported after HZI.8-10 Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis typically presents weeks to years after acute HZI with erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques at the site of the prior HZI. A biopsy reveals interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and multinucleated giant cells.8 Radiation recall dermatitis is a cutaneous inflammatory reaction limited to regions of prior radiation exposure after the administration of a triggering medication. Radiation recall dermatitis can present days to many years after the completion of treatment.9 Although the eruption in our patient was at the site of prior radiation, the pathologic and clinical presentation was not consistent with radiation recall dermatitis. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that may present as either solitary or numerous papules, plaques, or nodules and has been reported to occur after HZI. Biopsy reveals a diffuse dermal histiocytic infiltration with plasma cells and lymphocytes. In contrast to metastatic disease, mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare in cutaneous RosaiDorfman disease.11 Lichen planus is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology presenting as flat-topped, violaceous, pruritic papules12 that may present in a zosteriform pattern.13

Although it is uncommon, metastatic spread should be considered in patients with known malignancy presenting with zosteriform eruptions.2 Our patient remained on treatment with immunotherapy, as he was unable to undergo additional radiation and had failed multiple other lines of therapy. He died 3 months after presentation.

- Klebanov N, Reddy BY, Husain S, et al. Cutaneous presentation of mesothelioma with a sarcomatoid transformation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:378-382.

- Patel SC, Dowell JE. Modern management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer (Auckl). 2016;7:63-72.

- Ward RE, Ali SA, Kuhar M. Epithelioid malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:1057-1063.

- Prieto VG, Kenet BJ, Varghese M. Malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin, presenting as inflammatory carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:261-265.

- Gaudy-Marqueste C, Dales JP, Collet-Villette AM, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of pleural mesothelioma: two cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:455-459.

- Chiang A, Salomon N, Gaikwad R, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis mimicking herpes zoster rash. IDCases. 2018;12:167-168.

- Thomaidou E, Armon G, Klapholz L, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:734-736.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Carrasco L, Pastor MA, Izquierdo MJ, et al. Drug eruption secondary to acyclovir with recall phenomenon in a dermatome previously affected by herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:132-134.

- Malviya N, Marzuka A, Maamed-Tayeb M, et al. Cutaneous involvement of pre-existing Rosai-Dorfman disease via post-herpetic isotopic response. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1211-1214.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Fink-Puches R, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Smolle J. Zosteriform lichen planus. Dermatology. 1996;192:375-377.

- Klebanov N, Reddy BY, Husain S, et al. Cutaneous presentation of mesothelioma with a sarcomatoid transformation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:378-382.

- Patel SC, Dowell JE. Modern management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer (Auckl). 2016;7:63-72.

- Ward RE, Ali SA, Kuhar M. Epithelioid malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:1057-1063.

- Prieto VG, Kenet BJ, Varghese M. Malignant mesothelioma metastatic to the skin, presenting as inflammatory carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:261-265.

- Gaudy-Marqueste C, Dales JP, Collet-Villette AM, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of pleural mesothelioma: two cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130:455-459.

- Chiang A, Salomon N, Gaikwad R, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis mimicking herpes zoster rash. IDCases. 2018;12:167-168.

- Thomaidou E, Armon G, Klapholz L, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:734-736.

- Ferenczi K, Rosenberg AS, McCalmont TH, et al. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis: histopathologic findings in a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:739-745.

- Carrasco L, Pastor MA, Izquierdo MJ, et al. Drug eruption secondary to acyclovir with recall phenomenon in a dermatome previously affected by herpes zoster. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:132-134.

- Malviya N, Marzuka A, Maamed-Tayeb M, et al. Cutaneous involvement of pre-existing Rosai-Dorfman disease via post-herpetic isotopic response. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1211-1214.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732.

- Fink-Puches R, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Smolle J. Zosteriform lichen planus. Dermatology. 1996;192:375-377.

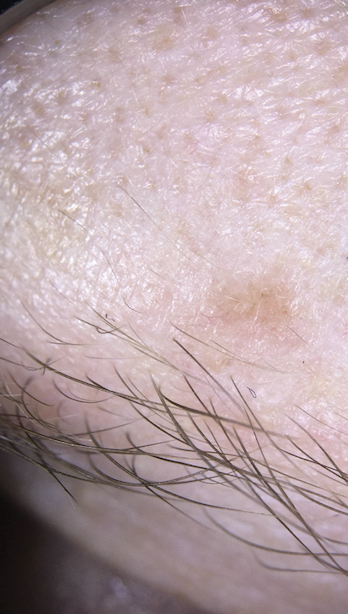

A 50-year-old man presented with erythematous macules and papules with a dermatomal distribution on the left thoracic region with associated pain of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions persisted after treatment for herpes zoster. His medical history was notable for mesothelioma that was diagnosed 6 years prior and was treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab following multiple lines of chemotherapy and investigational agents, left thoracotomy, extrapleural pneumonectomy, diaphragmatic reconstruction, and left chest radiation. His medical history also included Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed 36 years prior that was treated with an appendectomy, splenectomy, systemic chemotherapy, and radiation. Three weeks prior to the current presentation, he was treated by oncology with valacyclovir 1 g 3 times daily for 7 days for presumed herpes zoster without improvement. Physical examination revealed the absence of vesicles, as well as firm, 1- to 6-mm, erythematous papules and plaques, including a few outside of the most affected dermatomes.

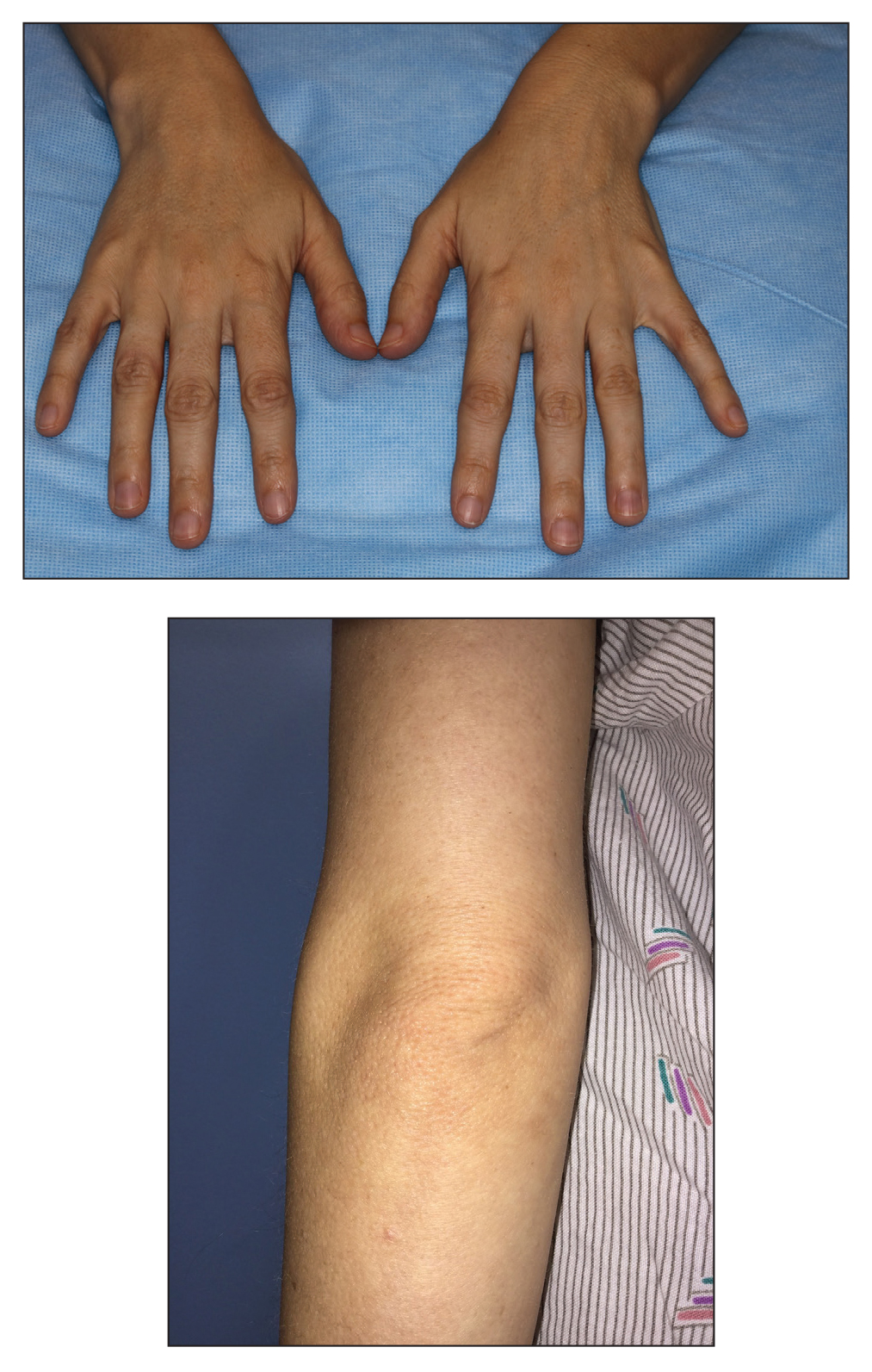

Pitted Depressions on the Hands and Elbows

The Diagnosis: Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol Syndrome

Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol syndrome (BDCS) is a rare X-linked dominant genodermatosis characterized by a triad of hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Since first being described in 1964,1 there have been fewer than 200 reported cases of BDCS.2 Although a causative gene has not yet been identified, the mutation has been mapped to an 11.4-Mb interval in the Xq25-27.1 region of the X chromosome.3

Classically, congenital hypotrichosis is the first observed symptom and can present shortly after birth.4 It typically is widespread, though sometimes it may be confined to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp. Follicular atrophoderma, which occurs due to a laxation and deepening of the follicular ostia, is seen in 80% of cases and typically presents in early childhood as depressions lacking hair.2 It commonly is found on the face, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Physical examination of our patient revealed follicular atrophoderma on both the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the extensor surfaces of the elbows. Hair shaft anomalies including pili torti, pili bifurcati, and trichorrhexis nodosa are infrequently observed symptoms of BDCS.2

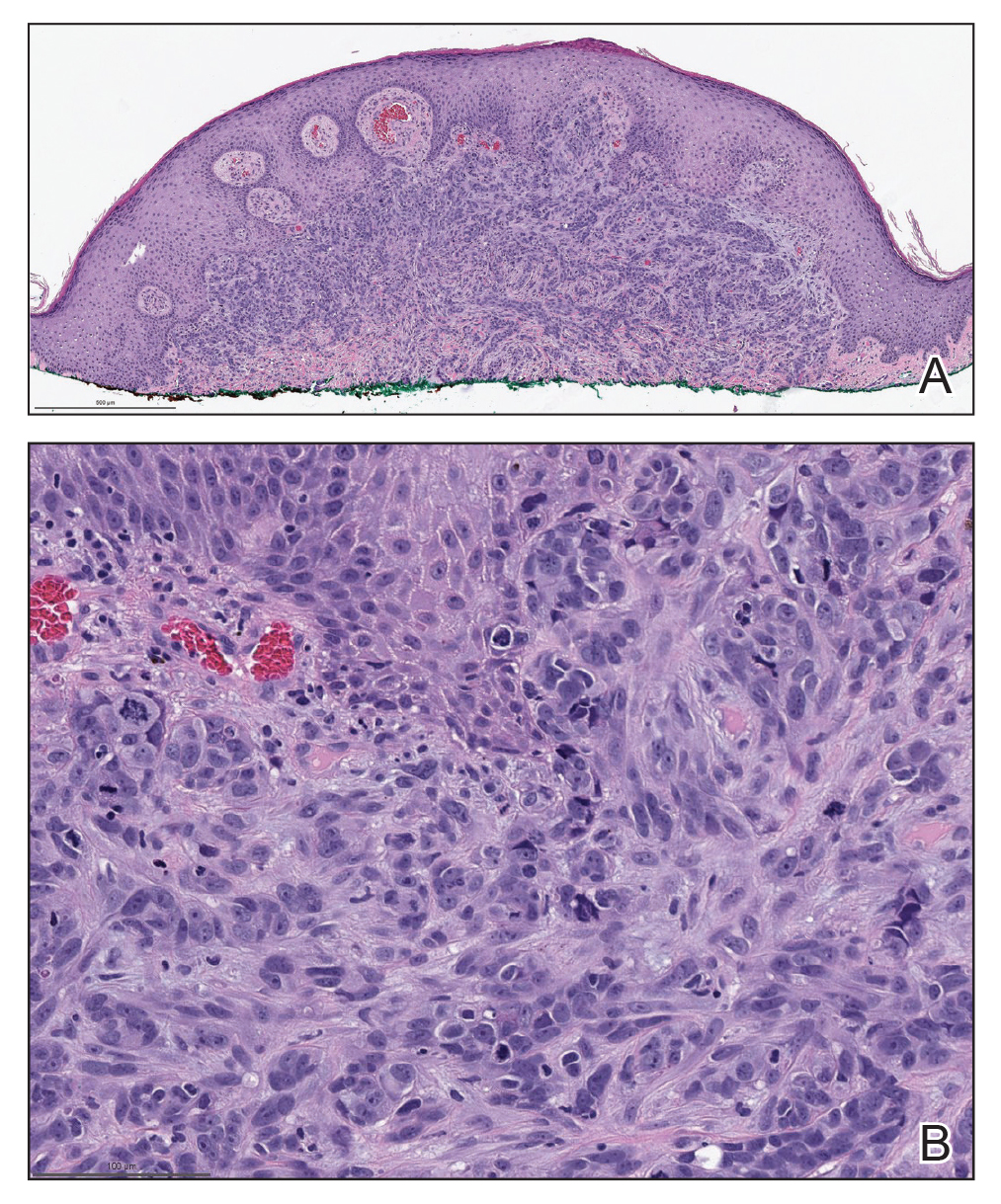

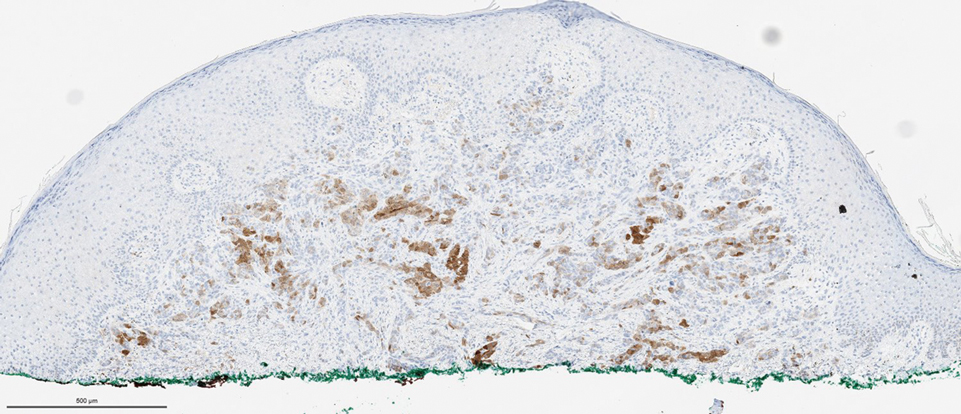

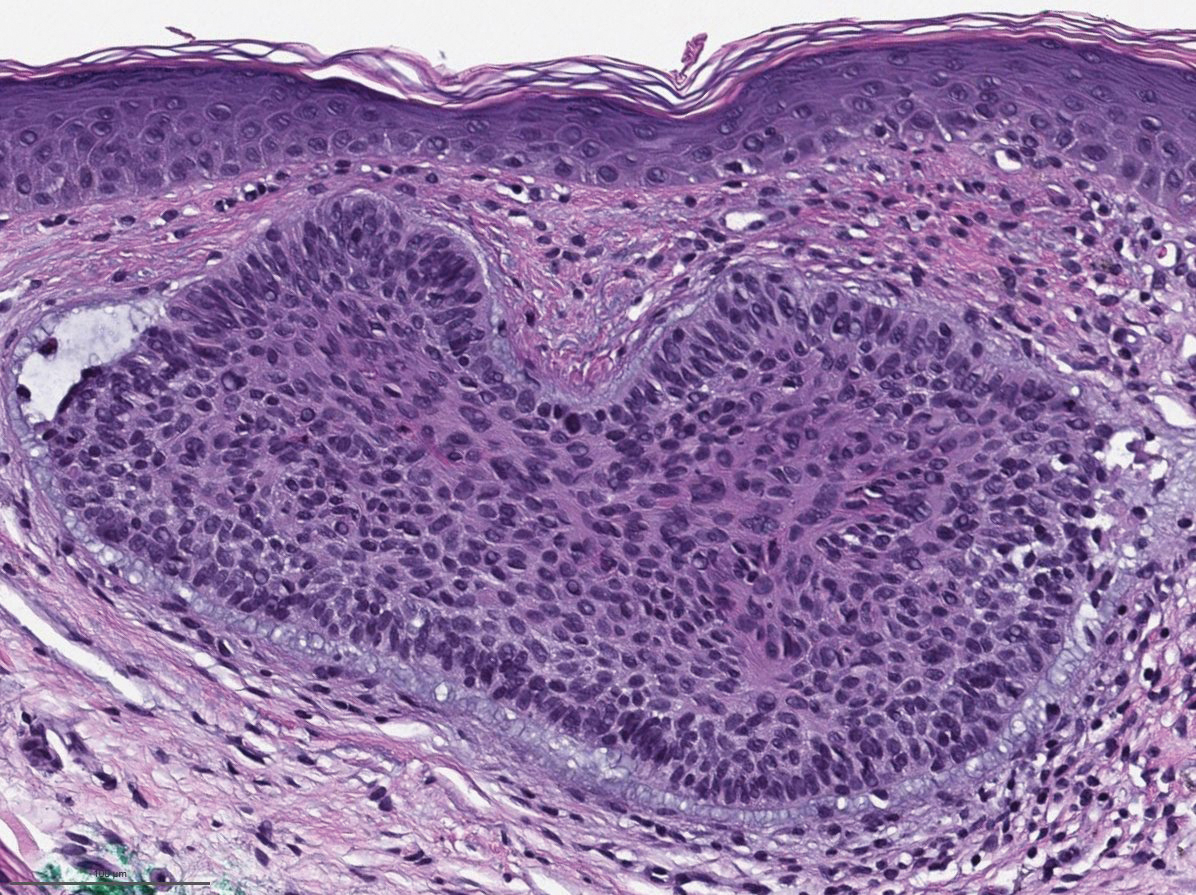

Basal cell carcinoma often manifests in the second or third decades of life, though there are reports of BCC developing in BDCS patients as young as 3 years. Basal cell carcinoma typically arises on sun-exposed areas, especially the face, neck, and chest. These lesions can be pigmented or nonpigmented and range from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.4 Our patient presented with a BCC on the forehead (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of BCC.

Milia, which are not considered part of the classic BDCS triad, are seen in 70% of cases.2 They commonly are found on the face and often diminish with age. Milia may precede the formation of follicular atrophoderma and BCC. Hypohidrosis most commonly occurs on the forehead but can be widespread.2 Other less commonly observed features include epidermal cysts, hyperpigmentation of the face, and trichoepitheliomas.4 The management of BDCS involves frequent clinical examinations, BCC treatment, genetic counseling, and photoprotection.2,4

Nevoid BCC syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by multiple nevoid BCCs, macrocephaly with a large forehead, cleft lip or palate, jaw keratocysts, palmar and plantar pits, and calcification of the falx cerebri.5 Nevoid BCC syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene in the hedgehog signaling pathway.6 The absence of common symptoms of NBCCS including macrocephaly, palmar or plantar pits, and cleft lip or palate, as well as negative genetic testing, suggested that our patient did not have NBCCS.

Rombo syndrome shares features with BDCS. Similar to BDCS, symptoms of Rombo syndrome include follicular atrophy, milialike papules, and BCC. Patients with Rombo syndrome typically present with atrophoderma vermiculatum on the cheeks and forehead in childhood.7 This atrophoderma presents with a pitted atrophic appearance in a reticular pattern on sun-exposed areas. Other distinguishing features from BDCS include cyanotic redness of sun-exposed skin and telangiectatic vessels.8

Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is another rare genodermatosis that is characterized by the presence of multiple infundibulocystic BCCs on the face and genitals. Infundibulocystic BCC is a well-differentiated subtype of BCC characterized by buds and cords of basaloid cells with scant stroma. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and has been linked to SUFU mutation in the sonic hedgehog pathway.9

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome is an autosomalrecessive disorder characterized by sparse hair, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and a high risk for developing keratinocyte carcinomas. It is differentiated from BDCS clinically by the presence of erythema, edema, and blistering, resulting in poikiloderma, plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, and bone defects.10

- Bazex A. Génodermatose complexe de type indéterminé associant une hypotrichose, un état atrophodermique généralisé et des dégénérescences cutanées multiples (épitheliomas baso-cellulaires). Bull Soc Fr Derm Syphiligr. 1964;71:206.

- Al Sabbagh MM, Baqi MA. Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1102-1106.

- Parren LJ, Abuzahra F, Wagenvoort T, et al. Linkage refinement of Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome to an 11.4-Mb interval on chromosome Xq25-27.1. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:201-203.

- Abuzahra F, Parren LJ, Frank J. Multiple familial and pigmented basal cell carcinomas in early childhood--Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:117-121.

- Shevchenko A, Durkin JR, Moon AT. Generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome versus Gorlin syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E396-E397.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- van Steensel MA, Jaspers NG, Steijlen PM. A case of Rombo syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1215-1218.

- Lee YC, Son SJ, Han TY, et al. A case of atrophoderma vermiculatum showing a good response to topical tretinoin. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:116-118.

- Schulman JM, Oh DH, Sanborn JZ, et al. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic basal cell carcinoma syndrome associated with a germline SUFU mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:323-327.

- Larizza L, Roversi G, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

The Diagnosis: Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol Syndrome

Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol syndrome (BDCS) is a rare X-linked dominant genodermatosis characterized by a triad of hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Since first being described in 1964,1 there have been fewer than 200 reported cases of BDCS.2 Although a causative gene has not yet been identified, the mutation has been mapped to an 11.4-Mb interval in the Xq25-27.1 region of the X chromosome.3

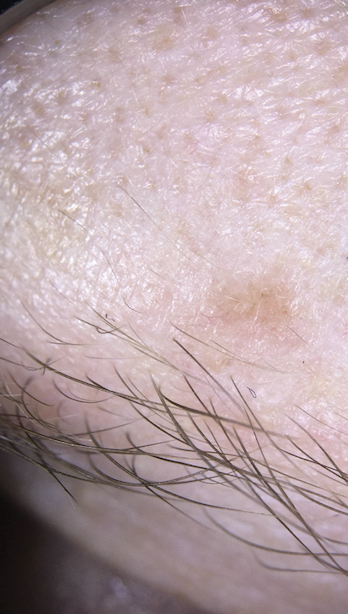

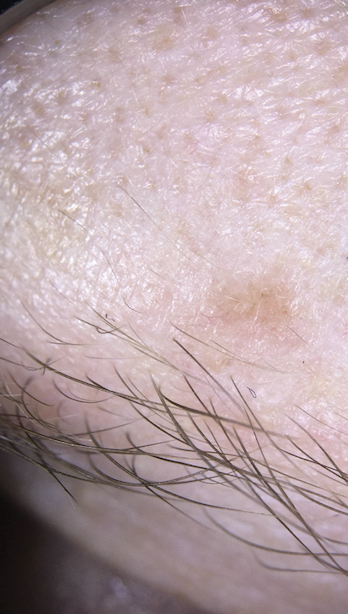

Classically, congenital hypotrichosis is the first observed symptom and can present shortly after birth.4 It typically is widespread, though sometimes it may be confined to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp. Follicular atrophoderma, which occurs due to a laxation and deepening of the follicular ostia, is seen in 80% of cases and typically presents in early childhood as depressions lacking hair.2 It commonly is found on the face, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Physical examination of our patient revealed follicular atrophoderma on both the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the extensor surfaces of the elbows. Hair shaft anomalies including pili torti, pili bifurcati, and trichorrhexis nodosa are infrequently observed symptoms of BDCS.2

Basal cell carcinoma often manifests in the second or third decades of life, though there are reports of BCC developing in BDCS patients as young as 3 years. Basal cell carcinoma typically arises on sun-exposed areas, especially the face, neck, and chest. These lesions can be pigmented or nonpigmented and range from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.4 Our patient presented with a BCC on the forehead (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of BCC.

Milia, which are not considered part of the classic BDCS triad, are seen in 70% of cases.2 They commonly are found on the face and often diminish with age. Milia may precede the formation of follicular atrophoderma and BCC. Hypohidrosis most commonly occurs on the forehead but can be widespread.2 Other less commonly observed features include epidermal cysts, hyperpigmentation of the face, and trichoepitheliomas.4 The management of BDCS involves frequent clinical examinations, BCC treatment, genetic counseling, and photoprotection.2,4

Nevoid BCC syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by multiple nevoid BCCs, macrocephaly with a large forehead, cleft lip or palate, jaw keratocysts, palmar and plantar pits, and calcification of the falx cerebri.5 Nevoid BCC syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene in the hedgehog signaling pathway.6 The absence of common symptoms of NBCCS including macrocephaly, palmar or plantar pits, and cleft lip or palate, as well as negative genetic testing, suggested that our patient did not have NBCCS.

Rombo syndrome shares features with BDCS. Similar to BDCS, symptoms of Rombo syndrome include follicular atrophy, milialike papules, and BCC. Patients with Rombo syndrome typically present with atrophoderma vermiculatum on the cheeks and forehead in childhood.7 This atrophoderma presents with a pitted atrophic appearance in a reticular pattern on sun-exposed areas. Other distinguishing features from BDCS include cyanotic redness of sun-exposed skin and telangiectatic vessels.8

Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is another rare genodermatosis that is characterized by the presence of multiple infundibulocystic BCCs on the face and genitals. Infundibulocystic BCC is a well-differentiated subtype of BCC characterized by buds and cords of basaloid cells with scant stroma. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and has been linked to SUFU mutation in the sonic hedgehog pathway.9

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome is an autosomalrecessive disorder characterized by sparse hair, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and a high risk for developing keratinocyte carcinomas. It is differentiated from BDCS clinically by the presence of erythema, edema, and blistering, resulting in poikiloderma, plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, and bone defects.10

The Diagnosis: Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol Syndrome

Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol syndrome (BDCS) is a rare X-linked dominant genodermatosis characterized by a triad of hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Since first being described in 1964,1 there have been fewer than 200 reported cases of BDCS.2 Although a causative gene has not yet been identified, the mutation has been mapped to an 11.4-Mb interval in the Xq25-27.1 region of the X chromosome.3

Classically, congenital hypotrichosis is the first observed symptom and can present shortly after birth.4 It typically is widespread, though sometimes it may be confined to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp. Follicular atrophoderma, which occurs due to a laxation and deepening of the follicular ostia, is seen in 80% of cases and typically presents in early childhood as depressions lacking hair.2 It commonly is found on the face, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Physical examination of our patient revealed follicular atrophoderma on both the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the extensor surfaces of the elbows. Hair shaft anomalies including pili torti, pili bifurcati, and trichorrhexis nodosa are infrequently observed symptoms of BDCS.2

Basal cell carcinoma often manifests in the second or third decades of life, though there are reports of BCC developing in BDCS patients as young as 3 years. Basal cell carcinoma typically arises on sun-exposed areas, especially the face, neck, and chest. These lesions can be pigmented or nonpigmented and range from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.4 Our patient presented with a BCC on the forehead (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of BCC.

Milia, which are not considered part of the classic BDCS triad, are seen in 70% of cases.2 They commonly are found on the face and often diminish with age. Milia may precede the formation of follicular atrophoderma and BCC. Hypohidrosis most commonly occurs on the forehead but can be widespread.2 Other less commonly observed features include epidermal cysts, hyperpigmentation of the face, and trichoepitheliomas.4 The management of BDCS involves frequent clinical examinations, BCC treatment, genetic counseling, and photoprotection.2,4

Nevoid BCC syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by multiple nevoid BCCs, macrocephaly with a large forehead, cleft lip or palate, jaw keratocysts, palmar and plantar pits, and calcification of the falx cerebri.5 Nevoid BCC syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene in the hedgehog signaling pathway.6 The absence of common symptoms of NBCCS including macrocephaly, palmar or plantar pits, and cleft lip or palate, as well as negative genetic testing, suggested that our patient did not have NBCCS.

Rombo syndrome shares features with BDCS. Similar to BDCS, symptoms of Rombo syndrome include follicular atrophy, milialike papules, and BCC. Patients with Rombo syndrome typically present with atrophoderma vermiculatum on the cheeks and forehead in childhood.7 This atrophoderma presents with a pitted atrophic appearance in a reticular pattern on sun-exposed areas. Other distinguishing features from BDCS include cyanotic redness of sun-exposed skin and telangiectatic vessels.8

Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is another rare genodermatosis that is characterized by the presence of multiple infundibulocystic BCCs on the face and genitals. Infundibulocystic BCC is a well-differentiated subtype of BCC characterized by buds and cords of basaloid cells with scant stroma. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and has been linked to SUFU mutation in the sonic hedgehog pathway.9

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome is an autosomalrecessive disorder characterized by sparse hair, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and a high risk for developing keratinocyte carcinomas. It is differentiated from BDCS clinically by the presence of erythema, edema, and blistering, resulting in poikiloderma, plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, and bone defects.10

- Bazex A. Génodermatose complexe de type indéterminé associant une hypotrichose, un état atrophodermique généralisé et des dégénérescences cutanées multiples (épitheliomas baso-cellulaires). Bull Soc Fr Derm Syphiligr. 1964;71:206.

- Al Sabbagh MM, Baqi MA. Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1102-1106.

- Parren LJ, Abuzahra F, Wagenvoort T, et al. Linkage refinement of Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome to an 11.4-Mb interval on chromosome Xq25-27.1. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:201-203.

- Abuzahra F, Parren LJ, Frank J. Multiple familial and pigmented basal cell carcinomas in early childhood--Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:117-121.

- Shevchenko A, Durkin JR, Moon AT. Generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome versus Gorlin syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E396-E397.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- van Steensel MA, Jaspers NG, Steijlen PM. A case of Rombo syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1215-1218.

- Lee YC, Son SJ, Han TY, et al. A case of atrophoderma vermiculatum showing a good response to topical tretinoin. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:116-118.

- Schulman JM, Oh DH, Sanborn JZ, et al. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic basal cell carcinoma syndrome associated with a germline SUFU mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:323-327.

- Larizza L, Roversi G, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

- Bazex A. Génodermatose complexe de type indéterminé associant une hypotrichose, un état atrophodermique généralisé et des dégénérescences cutanées multiples (épitheliomas baso-cellulaires). Bull Soc Fr Derm Syphiligr. 1964;71:206.

- Al Sabbagh MM, Baqi MA. Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1102-1106.

- Parren LJ, Abuzahra F, Wagenvoort T, et al. Linkage refinement of Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome to an 11.4-Mb interval on chromosome Xq25-27.1. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:201-203.

- Abuzahra F, Parren LJ, Frank J. Multiple familial and pigmented basal cell carcinomas in early childhood--Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:117-121.

- Shevchenko A, Durkin JR, Moon AT. Generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome versus Gorlin syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E396-E397.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- van Steensel MA, Jaspers NG, Steijlen PM. A case of Rombo syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1215-1218.

- Lee YC, Son SJ, Han TY, et al. A case of atrophoderma vermiculatum showing a good response to topical tretinoin. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:116-118.

- Schulman JM, Oh DH, Sanborn JZ, et al. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic basal cell carcinoma syndrome associated with a germline SUFU mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:323-327.

- Larizza L, Roversi G, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

A 28-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a pearly papule on the forehead of several months’ duration that was concerning for basal cell carcinoma (BCC). She had a history of numerous BCCs starting at the age of 17 years. She denied radiation or other carcinogenic exposures and had no other notable medical history. The patient’s mother and grandmother also had numerous BCCs. Physical examination revealed hypotrichosis; numerous 3- to 5-mm white cystic papules on the face, chest, and upper arms; and 1- to 5-mm pitted depressions on the dorsal aspects of the hands (top) and extensor surfaces of the elbows (bottom). A proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading was seen on histopathologic evaluation. Genetic testing revealed no protein patched homolog 1, PTCH1, or suppressor of fused homolog, SUFU, gene mutations.