User login

What Is Your Diagnosis? Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 25 weeks’ gestation presented with a generalized pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. The rash had initiated around the umbilicus and continued to progress with subsequent involvement of the arms and legs. The patient reported no allergies or current medications, and her personal and family history was unremarkable. She had 2 prior uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Physical examination revealed severe ecchymotic plaques, vesicles, and bullae on the arms (top), as well as confluent erythematous plaques on the abdomen (bottom), back, and legs. The mucosal surfaces, face, palms, and soles were spared. Laboratory values were within reference range.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

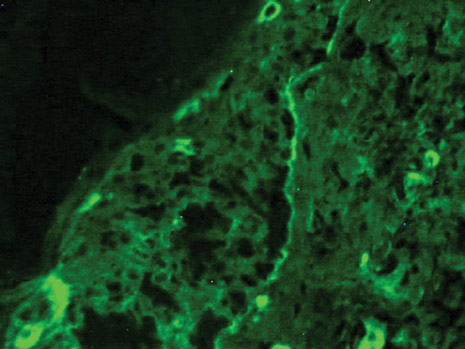

Dermoscopy revealed a patch of erythema with early central vesiculation (Figure 1). Perilesional skin biopsies revealed subepidermal bullae, and direct immunofluorescence revealed linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2).

|

Dermatoses of pregnancy are uncommon and may demonstrate similar clinical manifestations. Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) is a condition that may initially mimic other pregnancy-related skin diseases but is followed by the classic manifestations of a bullous disease. A biopsy specimen is needed to identify the epidermal lesions that are present. Once identified, it responds to treatment with steroids.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a skin disorder in which circulating IgG autoantibodies react against transmembrane proteins and hemidesmosomal components of the epidermal basal cells.1 This process leads to complement protein activation through the classical pathway, which promotes leukocyte recruitment and degranulation. The initial clinical manifestation includes pruritus, which is followed by characteristic bullous lesions.

Pemphigoid gestationis is hypothesized to arise from pathologic maternal IgG induced by paternal HLA antigens found in the placenta.2 The incidence of pemphigoid gestationis is thought to range from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000,3 with typical presentation in the second or third trimesters. It may be exacerbated during delivery and generally resolves after delivery. The periumbilical region is the first site affected with subsequent spreading to the arms and legs.3 The initial differential diagnosis based on patient history can include an adverse drug reaction or pruritic urticarial papules and pustules of pregnancy. Diagnosis is based on histologic examination of a perilesional skin biopsy. Light microscopy of the biopsy typically reveals subepidermal bullae with a predominance of infiltrated eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen usually confirms the diagnosis with the presence of linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence occasionally may reveal IgG deposition in the basal membrane.4

Treatment generally includes the use of topical and oral steroids.2,5 Fetal risks associated with the disease include premature birth and low birth weight.2,3 Our patient initially was started on a 1-mg/kg dose of oral prednisone and topical steroid (prednisone 60 mg in a tapering dose every 5 days); she showed a good response at 1-week follow-up. She was well controlled with a lower maintenance dose through the rest of the pregnancy and did not show subsequent disease exacerbation.

1. Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:69-79.

2. Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172-181.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109-112.

4. Imber MJ, Murphy GF, Jordon RE. The immunopathology of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:81-92.

5. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002292.

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 25 weeks’ gestation presented with a generalized pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. The rash had initiated around the umbilicus and continued to progress with subsequent involvement of the arms and legs. The patient reported no allergies or current medications, and her personal and family history was unremarkable. She had 2 prior uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Physical examination revealed severe ecchymotic plaques, vesicles, and bullae on the arms (top), as well as confluent erythematous plaques on the abdomen (bottom), back, and legs. The mucosal surfaces, face, palms, and soles were spared. Laboratory values were within reference range.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

Dermoscopy revealed a patch of erythema with early central vesiculation (Figure 1). Perilesional skin biopsies revealed subepidermal bullae, and direct immunofluorescence revealed linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2).

|

Dermatoses of pregnancy are uncommon and may demonstrate similar clinical manifestations. Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) is a condition that may initially mimic other pregnancy-related skin diseases but is followed by the classic manifestations of a bullous disease. A biopsy specimen is needed to identify the epidermal lesions that are present. Once identified, it responds to treatment with steroids.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a skin disorder in which circulating IgG autoantibodies react against transmembrane proteins and hemidesmosomal components of the epidermal basal cells.1 This process leads to complement protein activation through the classical pathway, which promotes leukocyte recruitment and degranulation. The initial clinical manifestation includes pruritus, which is followed by characteristic bullous lesions.

Pemphigoid gestationis is hypothesized to arise from pathologic maternal IgG induced by paternal HLA antigens found in the placenta.2 The incidence of pemphigoid gestationis is thought to range from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000,3 with typical presentation in the second or third trimesters. It may be exacerbated during delivery and generally resolves after delivery. The periumbilical region is the first site affected with subsequent spreading to the arms and legs.3 The initial differential diagnosis based on patient history can include an adverse drug reaction or pruritic urticarial papules and pustules of pregnancy. Diagnosis is based on histologic examination of a perilesional skin biopsy. Light microscopy of the biopsy typically reveals subepidermal bullae with a predominance of infiltrated eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen usually confirms the diagnosis with the presence of linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence occasionally may reveal IgG deposition in the basal membrane.4

Treatment generally includes the use of topical and oral steroids.2,5 Fetal risks associated with the disease include premature birth and low birth weight.2,3 Our patient initially was started on a 1-mg/kg dose of oral prednisone and topical steroid (prednisone 60 mg in a tapering dose every 5 days); she showed a good response at 1-week follow-up. She was well controlled with a lower maintenance dose through the rest of the pregnancy and did not show subsequent disease exacerbation.

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 25 weeks’ gestation presented with a generalized pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. The rash had initiated around the umbilicus and continued to progress with subsequent involvement of the arms and legs. The patient reported no allergies or current medications, and her personal and family history was unremarkable. She had 2 prior uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Physical examination revealed severe ecchymotic plaques, vesicles, and bullae on the arms (top), as well as confluent erythematous plaques on the abdomen (bottom), back, and legs. The mucosal surfaces, face, palms, and soles were spared. Laboratory values were within reference range.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

Dermoscopy revealed a patch of erythema with early central vesiculation (Figure 1). Perilesional skin biopsies revealed subepidermal bullae, and direct immunofluorescence revealed linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2).

|

Dermatoses of pregnancy are uncommon and may demonstrate similar clinical manifestations. Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) is a condition that may initially mimic other pregnancy-related skin diseases but is followed by the classic manifestations of a bullous disease. A biopsy specimen is needed to identify the epidermal lesions that are present. Once identified, it responds to treatment with steroids.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a skin disorder in which circulating IgG autoantibodies react against transmembrane proteins and hemidesmosomal components of the epidermal basal cells.1 This process leads to complement protein activation through the classical pathway, which promotes leukocyte recruitment and degranulation. The initial clinical manifestation includes pruritus, which is followed by characteristic bullous lesions.

Pemphigoid gestationis is hypothesized to arise from pathologic maternal IgG induced by paternal HLA antigens found in the placenta.2 The incidence of pemphigoid gestationis is thought to range from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000,3 with typical presentation in the second or third trimesters. It may be exacerbated during delivery and generally resolves after delivery. The periumbilical region is the first site affected with subsequent spreading to the arms and legs.3 The initial differential diagnosis based on patient history can include an adverse drug reaction or pruritic urticarial papules and pustules of pregnancy. Diagnosis is based on histologic examination of a perilesional skin biopsy. Light microscopy of the biopsy typically reveals subepidermal bullae with a predominance of infiltrated eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen usually confirms the diagnosis with the presence of linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence occasionally may reveal IgG deposition in the basal membrane.4

Treatment generally includes the use of topical and oral steroids.2,5 Fetal risks associated with the disease include premature birth and low birth weight.2,3 Our patient initially was started on a 1-mg/kg dose of oral prednisone and topical steroid (prednisone 60 mg in a tapering dose every 5 days); she showed a good response at 1-week follow-up. She was well controlled with a lower maintenance dose through the rest of the pregnancy and did not show subsequent disease exacerbation.

1. Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:69-79.

2. Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172-181.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109-112.

4. Imber MJ, Murphy GF, Jordon RE. The immunopathology of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:81-92.

5. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002292.

1. Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:69-79.

2. Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172-181.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109-112.

4. Imber MJ, Murphy GF, Jordon RE. The immunopathology of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:81-92.

5. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002292.

Hairs With an Irregular Shape

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

A 74-year-old man was evaluated for numerous peculiar hairs on the back that had been present for several years. He reported no other dermatologic concerns. The patient was obese and led a sedentary lifestyle, spending most of the day sitting or lying down. Physical examination revealed a hairy back with many irregularly shaped hairs.