User login

Buccal Fat Pad Reduction With Intraoperative Fat Transfer to the Temple

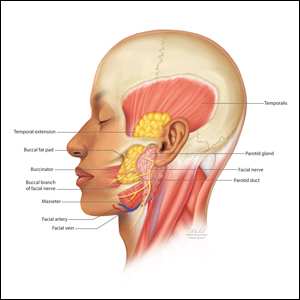

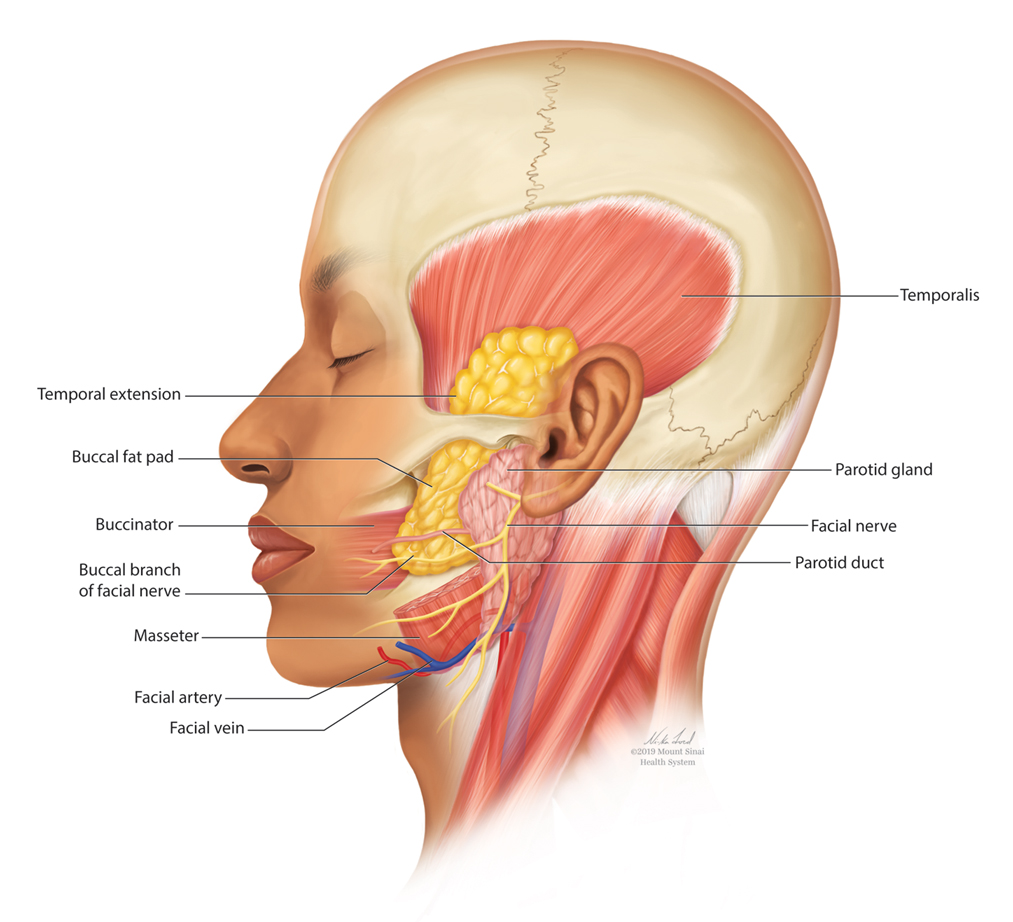

The buccal fat pad (Bichat fat pad) is a tubular-shaped collection of adipose tissue that occupies a prominent position in the midface. The buccal fat pad has been described as having 3 lobes: an anterior lobe, which is anterior to the masseter muscle; an intermediate lobe between the masseter and buccinator muscles; and a posterior lobe between the temporal masticatory space.1 There are 4 extensions from the body of the buccal fat pad: the buccal, the sublevator, the melolabial, and the pterygoid. It is the buccal extension and main body that are removed intraorally to achieve midfacial and lower facial contouring, as these support the contours of the cheeks. The deep fat pad within the temporal fossa is a true extension of the buccal fat pad (Figure).2 It has a complex relationship to the facial structures, with known variability in the positions of the buccal branch of the facial nerve and the parotid duct.3 The parotid duct travels over, superior to, or through the buccal extension 42%, 32%, and 26% of the time, respectively. The duct travels along the surface of the masseter, then pierces the buccinator to drain into the vestibule of the mouth at the second superior molar tooth. The buccal branch of the facial nerve travels on the surface of the buccal fat pad 73% of the time, whereas 27% of the time it travels deeper through the buccal extension.4 A study that used ultrasonography to map the surface anatomy path of the parotid duct in 50 healthy patients showed that the duct was within 1.5 cm of the middle half of a line between the lower border of the tragus and the oral commissure in 93% of individuals.5 We describe a technique in which part of the buccal fat pad is removed and the fat is transferred to the temple to achieve aesthetically pleasing facial contouring. We used a vertical line from the lateral canthus as a surface anatomy landmark to determine when the duct emerges from the gland and is most susceptible to injury.

Operative Technique

Correct instrumentation is important to obtain appropriate anatomic exposure for this procedure. The surgical tray should include 4-0 poliglecaprone 25 suture, bite guards, a needle driver, a hemostat, surgical scissors, toothed forceps, a Beaver surgical handle with #15 blade, a protected diathermy needle, cotton tip applicators, and gauze.

Fat Harvest—With the patient supine, bite blocks are placed, and the buccal fat pad incision line is marked with a surgical marker. A 1-cm line is drawn approximately 4 cm posterior to the oral commissure by the buccal bite marks. The location is verified by balloting externally on the buccal fat pad on the cheek. The incision line is then anesthetized transorally with lidocaine and epinephrine-containing solution. The cheek is retracted laterally with Caldwell-Luc retractors, and a 1-cm incision is made and carried through the mucosa and superficial muscle using the Colorado needle. Scissors are then used to spread the deeper muscle fibers to expose the deeper fascia and fat pads. Metzenbaum scissors are used to gently spread the fat while the surgeon places pressure on the external cheek, manipulating the fat into the wound. Without excess traction, the walnut-sized portion of the fat pad that protrudes is grasped with Debakey forceps, gently teased into the field, clamped at its base with a curved hemostat, and excised. The stump is electrocoagulated with an extendable protected Colorado needle, with care to prevent inadvertent cauterization of the lips. The wound is closed with a single 4-0 poliglecaprone-25 suture.

A 5-cc Luer lock syringe is preloaded with 2 cc of normal saline and attached to another 5-cc Luer lock syringe via a female-female attachment. The excised fat is then placed in a 5-cc Luer lock syringe by removing the plunger. The plunger is then reinstalled, and the fat is injected back and forth approximately 30 times. The fat is centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 3 minutes. The purified fat is then transferred to a 1-cc Luer lock syringe attached to an 18-gauge needle.

Fat Injection—The authors use an 18-gauge needle to perform depot injections into the temporal fossae above the periosteum. This is a relatively safe area of the face to inject, but care must be taken to avoid injury to the superficial temporal artery. Between 1.5 and 3 cc of high-quality fat usually are administered to each temple.

Aftercare Instructions—The patient is instructed to have a soft diet for 24 to 48 hours and can return to work the next day. The patient also is given prophylactic antibiotics with Gram-negative coverage for 7 days (amoxicillin-clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg orally twice daily for 7 days).

Candidates for Buccal Fat Pad Reduction

Buccal fat pad reduction has become an increasingly popular technique for midface and lower face shaping to decrease the appearance of a round face. To achieve an aesthetically pleasing midface, surgeons should consider enhancing zygomatic eminences while emphasizing the border between the zygomatic prominence and cheek hollow.6 Selection criteria for buccal fat pad reduction are not well established. One study recommended avoiding the procedure in pregnant or lactating patients, patients with chronic illnesses, patients on blood-thinning agents, and patients younger than 18 years. In addition, this study suggested ensuring the malar fullness is in the anteromedial portion of the face, as posterolateral fullness may be due to masseter hypertrophy.6

Complications From Buccal Fat Pad Reduction

Complications associated with buccal fat pad reduction include inadvertent damage to surrounding structures, including the buccal branch of the facial nerve and parotid duct. Because the location of the facial nerve in relation to the parotid duct is highly variable, surgeons must be aware of its anatomy to avoid unintentional damage. Hwang et al7 reported that the parotid duct and buccal branches of the facial nerves passed through the buccal extension in 26.3% of cadavers. The transbuccal approach is preferred over the sub–superficial muscular aponeurotic system approach largely because it avoids these structures. In addition, blunt dissection may further decrease chances of injury. Although the long-term effects are unknown, there is a potential risk for facial hollowing.3 The use of preprocedure ultrasonography to quantify the buccal fat pad may avoid overresection and enhanced potential for facial hollowing.6

Avoidance of Temporal Hollowing

Because the buccal fat pad extends into the temporal space, buccal fat pad reduction may lead to further temporal hollowing, contributing to an aged appearance. The authors’ technique addresses both midface and upper face contouring in one minimally invasive procedure. Temporal hollowing commonly has been corrected with autologous fat grafting from the thigh or abdomen, which leads to an additional scar at the donor site. Our technique relies on autologous adjacent fat transfer from previously removed buccal fat. In addition, compared with the use of hyaluronic acid fillers for temple reflation, fat transfer largely is safe and biocompatible. Major complications of autologous fat transfer to the temples include nodularity or fat clumping, fat necrosis, sensory or motor nerve damage, and edema or ecchymosis.4 Also, with time there will be ongoing hollowing of the temples as part of the aging process with soft tissue and bone resorption. Therefore, further volume restoration procedures may be required in the future to address these dynamic changes.

Conclusion

The buccal fat pad has been extensively used to reconstruct oral defects, including oroantral and cranial base defects, owing to its high vascularity.6 However, there also is great potential to utilize buccal fat for autologous fat transfer to improve temporal wasting. Further studies are needed to determine optimal technique as well as longer-term safety and efficacy of this procedure.

- Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, et al. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2509-2518.

- Yousuf S, Tubbs RS, Wartmann CT, et al. A review of the gross anatomy, functions, pathology, and clinical uses of the buccal fat pad. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32:427-436.

- Benjamin M, Reish RG. Buccal fat pad excision: proceed with caution. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:E1970.

- Tzikas TL. Fat grafting volume restoration to the brow and temporal regions. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34:164-172.

- Stringer MD, Mirjalili SA, Meredith SJ, et al. Redefining the surface anatomy of the parotid duct: an in vivo ultrasound study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1032-1037.

- Sezgin B, Tatar S, Boge M, et al. The excision of the buccal fat pad for cheek refinement: volumetric considerations. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:585-592.

- Hwang K, Cho HJ, Battuvshin D, et al. Interrelated buccal fat pad with facial buccal branches and parotid duct. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:658-660.

The buccal fat pad (Bichat fat pad) is a tubular-shaped collection of adipose tissue that occupies a prominent position in the midface. The buccal fat pad has been described as having 3 lobes: an anterior lobe, which is anterior to the masseter muscle; an intermediate lobe between the masseter and buccinator muscles; and a posterior lobe between the temporal masticatory space.1 There are 4 extensions from the body of the buccal fat pad: the buccal, the sublevator, the melolabial, and the pterygoid. It is the buccal extension and main body that are removed intraorally to achieve midfacial and lower facial contouring, as these support the contours of the cheeks. The deep fat pad within the temporal fossa is a true extension of the buccal fat pad (Figure).2 It has a complex relationship to the facial structures, with known variability in the positions of the buccal branch of the facial nerve and the parotid duct.3 The parotid duct travels over, superior to, or through the buccal extension 42%, 32%, and 26% of the time, respectively. The duct travels along the surface of the masseter, then pierces the buccinator to drain into the vestibule of the mouth at the second superior molar tooth. The buccal branch of the facial nerve travels on the surface of the buccal fat pad 73% of the time, whereas 27% of the time it travels deeper through the buccal extension.4 A study that used ultrasonography to map the surface anatomy path of the parotid duct in 50 healthy patients showed that the duct was within 1.5 cm of the middle half of a line between the lower border of the tragus and the oral commissure in 93% of individuals.5 We describe a technique in which part of the buccal fat pad is removed and the fat is transferred to the temple to achieve aesthetically pleasing facial contouring. We used a vertical line from the lateral canthus as a surface anatomy landmark to determine when the duct emerges from the gland and is most susceptible to injury.

Operative Technique

Correct instrumentation is important to obtain appropriate anatomic exposure for this procedure. The surgical tray should include 4-0 poliglecaprone 25 suture, bite guards, a needle driver, a hemostat, surgical scissors, toothed forceps, a Beaver surgical handle with #15 blade, a protected diathermy needle, cotton tip applicators, and gauze.

Fat Harvest—With the patient supine, bite blocks are placed, and the buccal fat pad incision line is marked with a surgical marker. A 1-cm line is drawn approximately 4 cm posterior to the oral commissure by the buccal bite marks. The location is verified by balloting externally on the buccal fat pad on the cheek. The incision line is then anesthetized transorally with lidocaine and epinephrine-containing solution. The cheek is retracted laterally with Caldwell-Luc retractors, and a 1-cm incision is made and carried through the mucosa and superficial muscle using the Colorado needle. Scissors are then used to spread the deeper muscle fibers to expose the deeper fascia and fat pads. Metzenbaum scissors are used to gently spread the fat while the surgeon places pressure on the external cheek, manipulating the fat into the wound. Without excess traction, the walnut-sized portion of the fat pad that protrudes is grasped with Debakey forceps, gently teased into the field, clamped at its base with a curved hemostat, and excised. The stump is electrocoagulated with an extendable protected Colorado needle, with care to prevent inadvertent cauterization of the lips. The wound is closed with a single 4-0 poliglecaprone-25 suture.

A 5-cc Luer lock syringe is preloaded with 2 cc of normal saline and attached to another 5-cc Luer lock syringe via a female-female attachment. The excised fat is then placed in a 5-cc Luer lock syringe by removing the plunger. The plunger is then reinstalled, and the fat is injected back and forth approximately 30 times. The fat is centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 3 minutes. The purified fat is then transferred to a 1-cc Luer lock syringe attached to an 18-gauge needle.

Fat Injection—The authors use an 18-gauge needle to perform depot injections into the temporal fossae above the periosteum. This is a relatively safe area of the face to inject, but care must be taken to avoid injury to the superficial temporal artery. Between 1.5 and 3 cc of high-quality fat usually are administered to each temple.

Aftercare Instructions—The patient is instructed to have a soft diet for 24 to 48 hours and can return to work the next day. The patient also is given prophylactic antibiotics with Gram-negative coverage for 7 days (amoxicillin-clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg orally twice daily for 7 days).

Candidates for Buccal Fat Pad Reduction

Buccal fat pad reduction has become an increasingly popular technique for midface and lower face shaping to decrease the appearance of a round face. To achieve an aesthetically pleasing midface, surgeons should consider enhancing zygomatic eminences while emphasizing the border between the zygomatic prominence and cheek hollow.6 Selection criteria for buccal fat pad reduction are not well established. One study recommended avoiding the procedure in pregnant or lactating patients, patients with chronic illnesses, patients on blood-thinning agents, and patients younger than 18 years. In addition, this study suggested ensuring the malar fullness is in the anteromedial portion of the face, as posterolateral fullness may be due to masseter hypertrophy.6

Complications From Buccal Fat Pad Reduction

Complications associated with buccal fat pad reduction include inadvertent damage to surrounding structures, including the buccal branch of the facial nerve and parotid duct. Because the location of the facial nerve in relation to the parotid duct is highly variable, surgeons must be aware of its anatomy to avoid unintentional damage. Hwang et al7 reported that the parotid duct and buccal branches of the facial nerves passed through the buccal extension in 26.3% of cadavers. The transbuccal approach is preferred over the sub–superficial muscular aponeurotic system approach largely because it avoids these structures. In addition, blunt dissection may further decrease chances of injury. Although the long-term effects are unknown, there is a potential risk for facial hollowing.3 The use of preprocedure ultrasonography to quantify the buccal fat pad may avoid overresection and enhanced potential for facial hollowing.6

Avoidance of Temporal Hollowing

Because the buccal fat pad extends into the temporal space, buccal fat pad reduction may lead to further temporal hollowing, contributing to an aged appearance. The authors’ technique addresses both midface and upper face contouring in one minimally invasive procedure. Temporal hollowing commonly has been corrected with autologous fat grafting from the thigh or abdomen, which leads to an additional scar at the donor site. Our technique relies on autologous adjacent fat transfer from previously removed buccal fat. In addition, compared with the use of hyaluronic acid fillers for temple reflation, fat transfer largely is safe and biocompatible. Major complications of autologous fat transfer to the temples include nodularity or fat clumping, fat necrosis, sensory or motor nerve damage, and edema or ecchymosis.4 Also, with time there will be ongoing hollowing of the temples as part of the aging process with soft tissue and bone resorption. Therefore, further volume restoration procedures may be required in the future to address these dynamic changes.

Conclusion

The buccal fat pad has been extensively used to reconstruct oral defects, including oroantral and cranial base defects, owing to its high vascularity.6 However, there also is great potential to utilize buccal fat for autologous fat transfer to improve temporal wasting. Further studies are needed to determine optimal technique as well as longer-term safety and efficacy of this procedure.

The buccal fat pad (Bichat fat pad) is a tubular-shaped collection of adipose tissue that occupies a prominent position in the midface. The buccal fat pad has been described as having 3 lobes: an anterior lobe, which is anterior to the masseter muscle; an intermediate lobe between the masseter and buccinator muscles; and a posterior lobe between the temporal masticatory space.1 There are 4 extensions from the body of the buccal fat pad: the buccal, the sublevator, the melolabial, and the pterygoid. It is the buccal extension and main body that are removed intraorally to achieve midfacial and lower facial contouring, as these support the contours of the cheeks. The deep fat pad within the temporal fossa is a true extension of the buccal fat pad (Figure).2 It has a complex relationship to the facial structures, with known variability in the positions of the buccal branch of the facial nerve and the parotid duct.3 The parotid duct travels over, superior to, or through the buccal extension 42%, 32%, and 26% of the time, respectively. The duct travels along the surface of the masseter, then pierces the buccinator to drain into the vestibule of the mouth at the second superior molar tooth. The buccal branch of the facial nerve travels on the surface of the buccal fat pad 73% of the time, whereas 27% of the time it travels deeper through the buccal extension.4 A study that used ultrasonography to map the surface anatomy path of the parotid duct in 50 healthy patients showed that the duct was within 1.5 cm of the middle half of a line between the lower border of the tragus and the oral commissure in 93% of individuals.5 We describe a technique in which part of the buccal fat pad is removed and the fat is transferred to the temple to achieve aesthetically pleasing facial contouring. We used a vertical line from the lateral canthus as a surface anatomy landmark to determine when the duct emerges from the gland and is most susceptible to injury.

Operative Technique

Correct instrumentation is important to obtain appropriate anatomic exposure for this procedure. The surgical tray should include 4-0 poliglecaprone 25 suture, bite guards, a needle driver, a hemostat, surgical scissors, toothed forceps, a Beaver surgical handle with #15 blade, a protected diathermy needle, cotton tip applicators, and gauze.

Fat Harvest—With the patient supine, bite blocks are placed, and the buccal fat pad incision line is marked with a surgical marker. A 1-cm line is drawn approximately 4 cm posterior to the oral commissure by the buccal bite marks. The location is verified by balloting externally on the buccal fat pad on the cheek. The incision line is then anesthetized transorally with lidocaine and epinephrine-containing solution. The cheek is retracted laterally with Caldwell-Luc retractors, and a 1-cm incision is made and carried through the mucosa and superficial muscle using the Colorado needle. Scissors are then used to spread the deeper muscle fibers to expose the deeper fascia and fat pads. Metzenbaum scissors are used to gently spread the fat while the surgeon places pressure on the external cheek, manipulating the fat into the wound. Without excess traction, the walnut-sized portion of the fat pad that protrudes is grasped with Debakey forceps, gently teased into the field, clamped at its base with a curved hemostat, and excised. The stump is electrocoagulated with an extendable protected Colorado needle, with care to prevent inadvertent cauterization of the lips. The wound is closed with a single 4-0 poliglecaprone-25 suture.

A 5-cc Luer lock syringe is preloaded with 2 cc of normal saline and attached to another 5-cc Luer lock syringe via a female-female attachment. The excised fat is then placed in a 5-cc Luer lock syringe by removing the plunger. The plunger is then reinstalled, and the fat is injected back and forth approximately 30 times. The fat is centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 3 minutes. The purified fat is then transferred to a 1-cc Luer lock syringe attached to an 18-gauge needle.

Fat Injection—The authors use an 18-gauge needle to perform depot injections into the temporal fossae above the periosteum. This is a relatively safe area of the face to inject, but care must be taken to avoid injury to the superficial temporal artery. Between 1.5 and 3 cc of high-quality fat usually are administered to each temple.

Aftercare Instructions—The patient is instructed to have a soft diet for 24 to 48 hours and can return to work the next day. The patient also is given prophylactic antibiotics with Gram-negative coverage for 7 days (amoxicillin-clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg orally twice daily for 7 days).

Candidates for Buccal Fat Pad Reduction

Buccal fat pad reduction has become an increasingly popular technique for midface and lower face shaping to decrease the appearance of a round face. To achieve an aesthetically pleasing midface, surgeons should consider enhancing zygomatic eminences while emphasizing the border between the zygomatic prominence and cheek hollow.6 Selection criteria for buccal fat pad reduction are not well established. One study recommended avoiding the procedure in pregnant or lactating patients, patients with chronic illnesses, patients on blood-thinning agents, and patients younger than 18 years. In addition, this study suggested ensuring the malar fullness is in the anteromedial portion of the face, as posterolateral fullness may be due to masseter hypertrophy.6

Complications From Buccal Fat Pad Reduction

Complications associated with buccal fat pad reduction include inadvertent damage to surrounding structures, including the buccal branch of the facial nerve and parotid duct. Because the location of the facial nerve in relation to the parotid duct is highly variable, surgeons must be aware of its anatomy to avoid unintentional damage. Hwang et al7 reported that the parotid duct and buccal branches of the facial nerves passed through the buccal extension in 26.3% of cadavers. The transbuccal approach is preferred over the sub–superficial muscular aponeurotic system approach largely because it avoids these structures. In addition, blunt dissection may further decrease chances of injury. Although the long-term effects are unknown, there is a potential risk for facial hollowing.3 The use of preprocedure ultrasonography to quantify the buccal fat pad may avoid overresection and enhanced potential for facial hollowing.6

Avoidance of Temporal Hollowing

Because the buccal fat pad extends into the temporal space, buccal fat pad reduction may lead to further temporal hollowing, contributing to an aged appearance. The authors’ technique addresses both midface and upper face contouring in one minimally invasive procedure. Temporal hollowing commonly has been corrected with autologous fat grafting from the thigh or abdomen, which leads to an additional scar at the donor site. Our technique relies on autologous adjacent fat transfer from previously removed buccal fat. In addition, compared with the use of hyaluronic acid fillers for temple reflation, fat transfer largely is safe and biocompatible. Major complications of autologous fat transfer to the temples include nodularity or fat clumping, fat necrosis, sensory or motor nerve damage, and edema or ecchymosis.4 Also, with time there will be ongoing hollowing of the temples as part of the aging process with soft tissue and bone resorption. Therefore, further volume restoration procedures may be required in the future to address these dynamic changes.

Conclusion

The buccal fat pad has been extensively used to reconstruct oral defects, including oroantral and cranial base defects, owing to its high vascularity.6 However, there also is great potential to utilize buccal fat for autologous fat transfer to improve temporal wasting. Further studies are needed to determine optimal technique as well as longer-term safety and efficacy of this procedure.

- Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, et al. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2509-2518.

- Yousuf S, Tubbs RS, Wartmann CT, et al. A review of the gross anatomy, functions, pathology, and clinical uses of the buccal fat pad. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32:427-436.

- Benjamin M, Reish RG. Buccal fat pad excision: proceed with caution. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:E1970.

- Tzikas TL. Fat grafting volume restoration to the brow and temporal regions. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34:164-172.

- Stringer MD, Mirjalili SA, Meredith SJ, et al. Redefining the surface anatomy of the parotid duct: an in vivo ultrasound study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1032-1037.

- Sezgin B, Tatar S, Boge M, et al. The excision of the buccal fat pad for cheek refinement: volumetric considerations. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:585-592.

- Hwang K, Cho HJ, Battuvshin D, et al. Interrelated buccal fat pad with facial buccal branches and parotid duct. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:658-660.

- Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, et al. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2509-2518.

- Yousuf S, Tubbs RS, Wartmann CT, et al. A review of the gross anatomy, functions, pathology, and clinical uses of the buccal fat pad. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32:427-436.

- Benjamin M, Reish RG. Buccal fat pad excision: proceed with caution. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:E1970.

- Tzikas TL. Fat grafting volume restoration to the brow and temporal regions. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34:164-172.

- Stringer MD, Mirjalili SA, Meredith SJ, et al. Redefining the surface anatomy of the parotid duct: an in vivo ultrasound study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1032-1037.

- Sezgin B, Tatar S, Boge M, et al. The excision of the buccal fat pad for cheek refinement: volumetric considerations. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:585-592.

- Hwang K, Cho HJ, Battuvshin D, et al. Interrelated buccal fat pad with facial buccal branches and parotid duct. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:658-660.

Practice Points

- Buccal fat pad reduction is an increasingly popular procedure for facial shaping.

- Buccal fat pad reduction in addition to natural aging can result in volume depletion of the temporal fossae.

- Removed buccal fat can be transferred to the temples for increased volume.

Scleromyxedema in a Patient With Thyroid Disease: An Atypical Case or a Case for Revised Criteria?

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

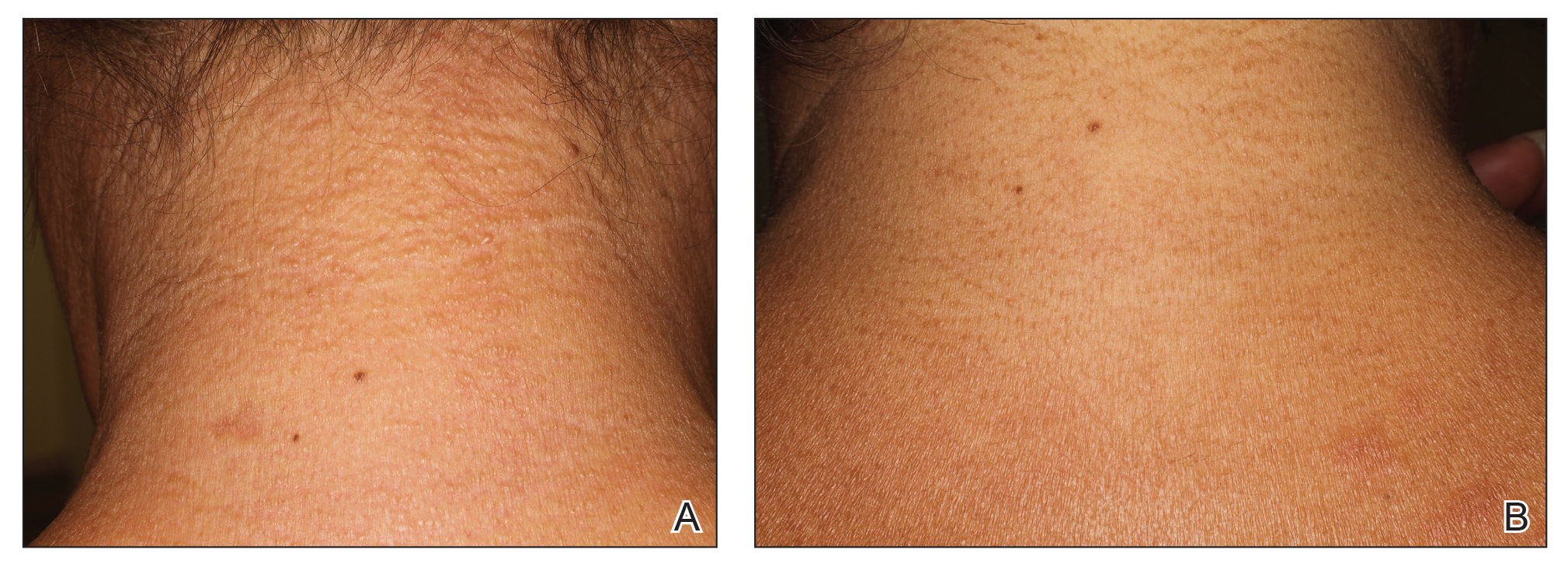

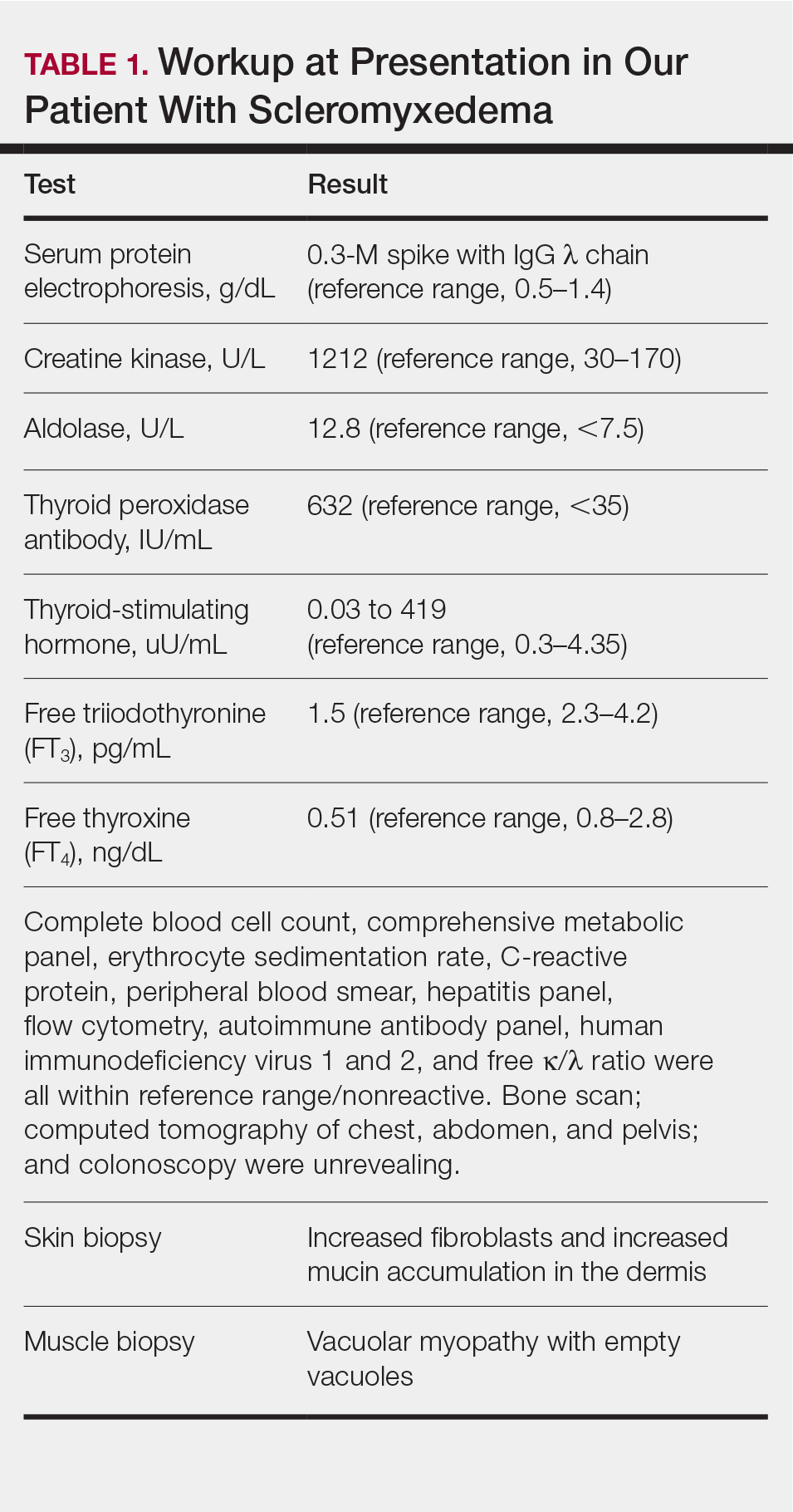

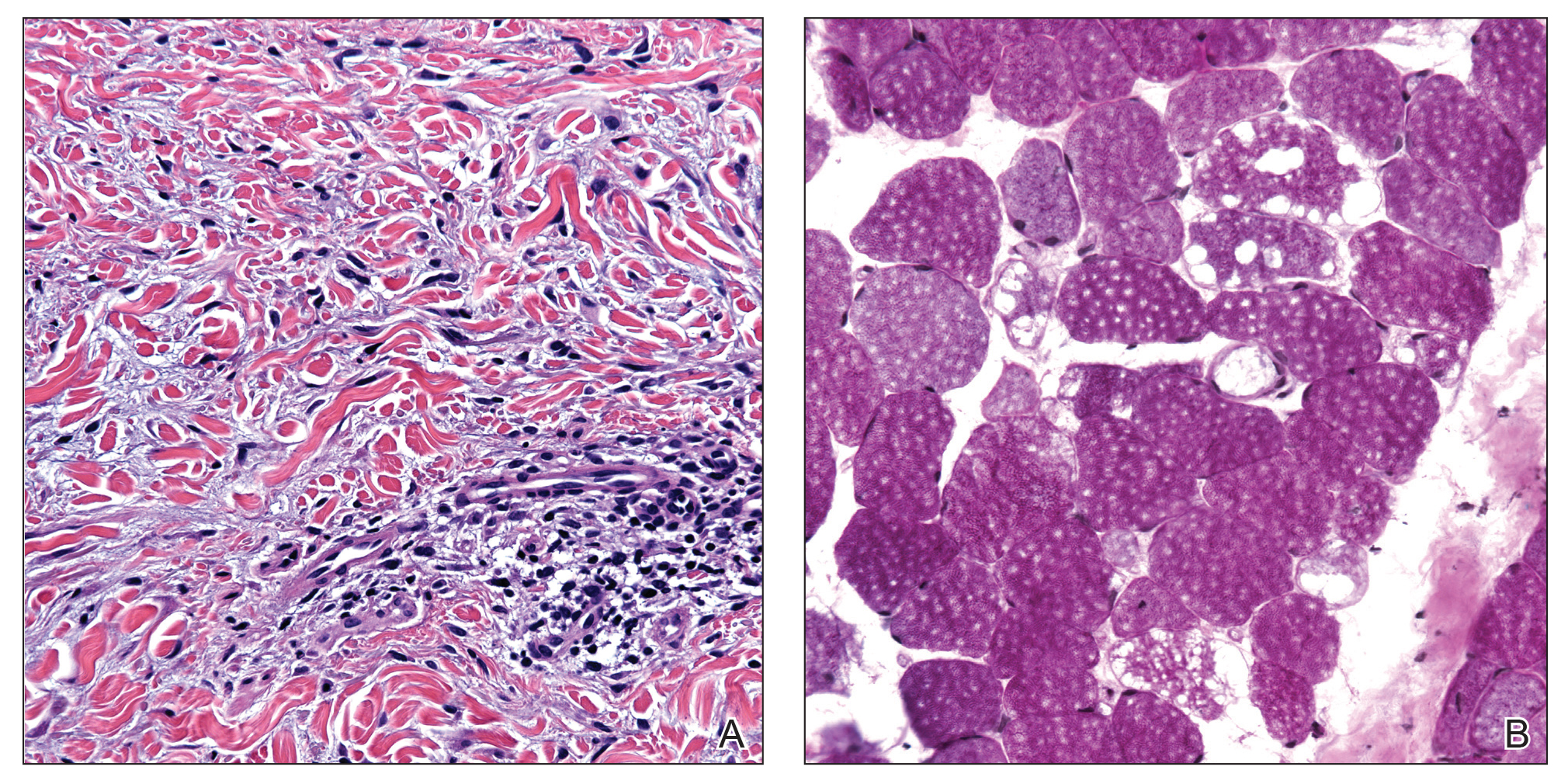

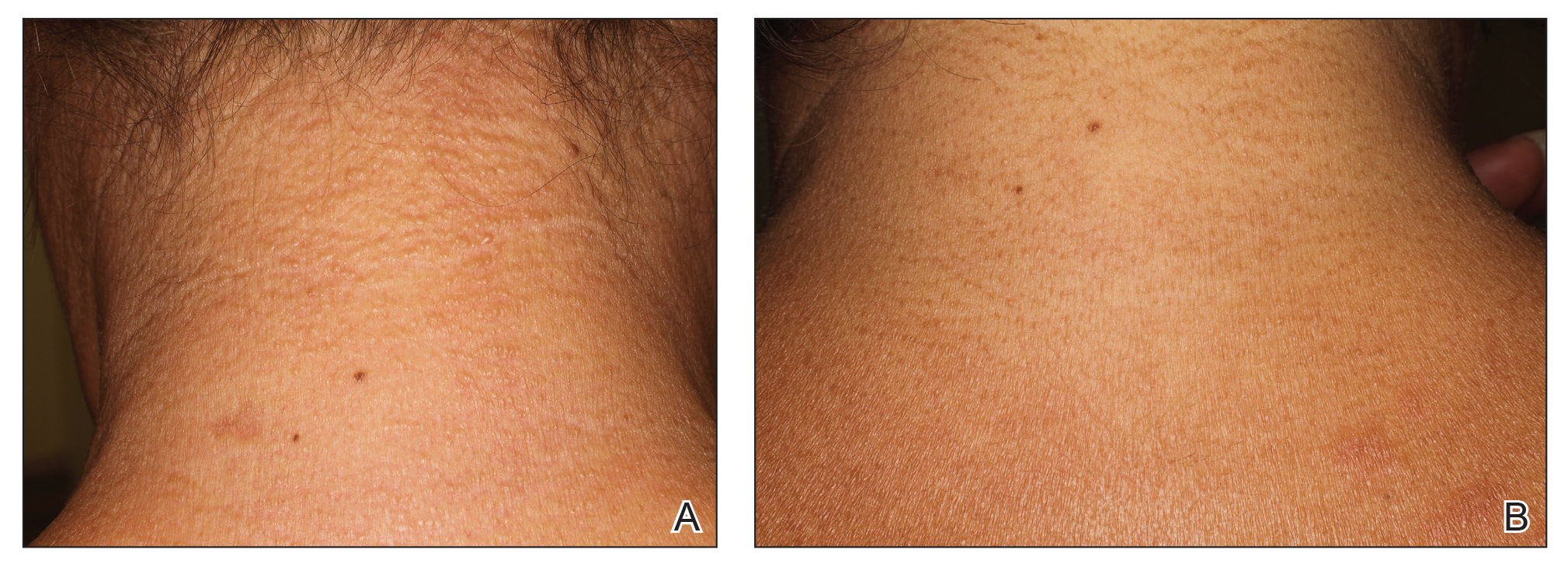

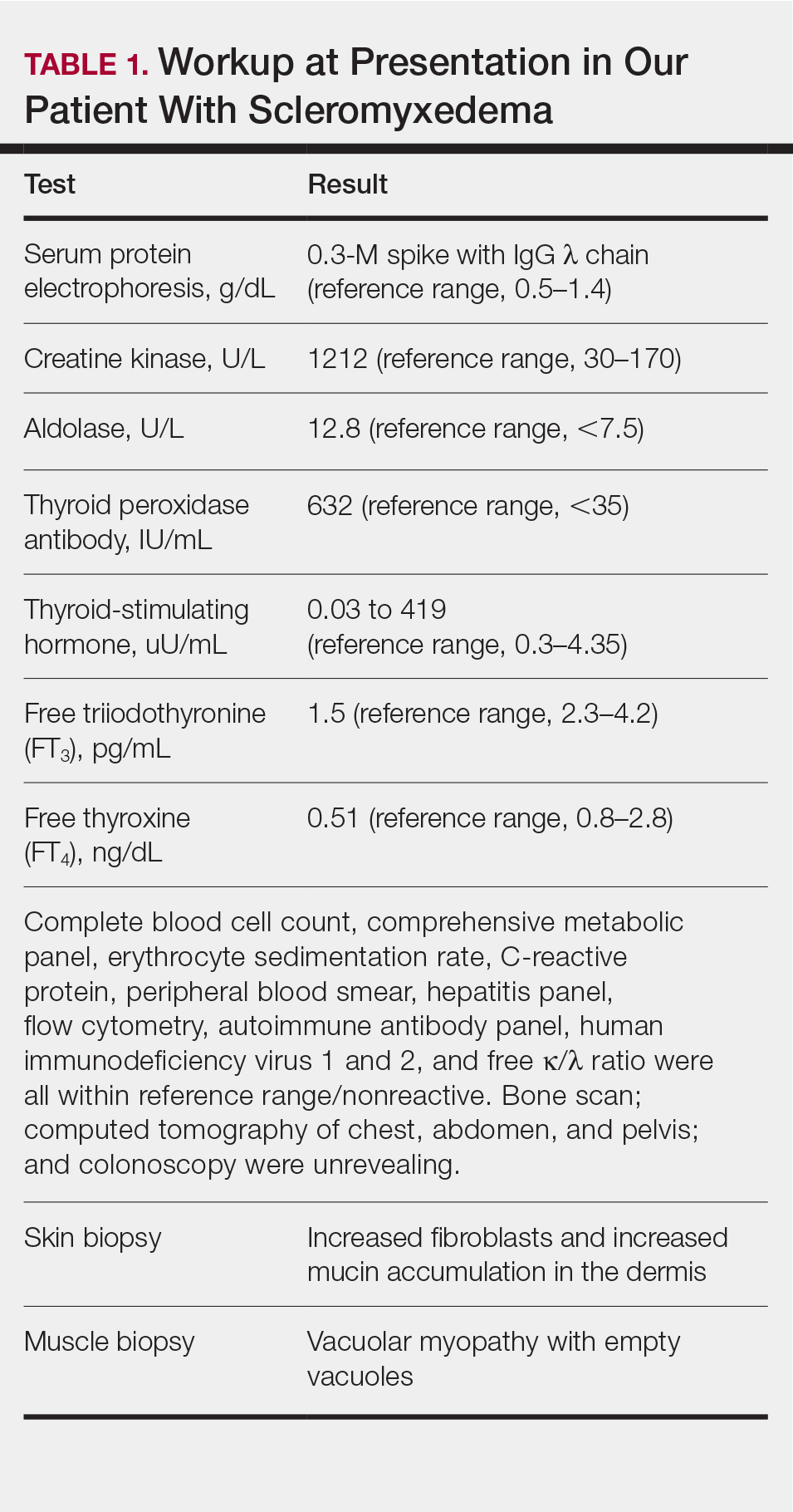

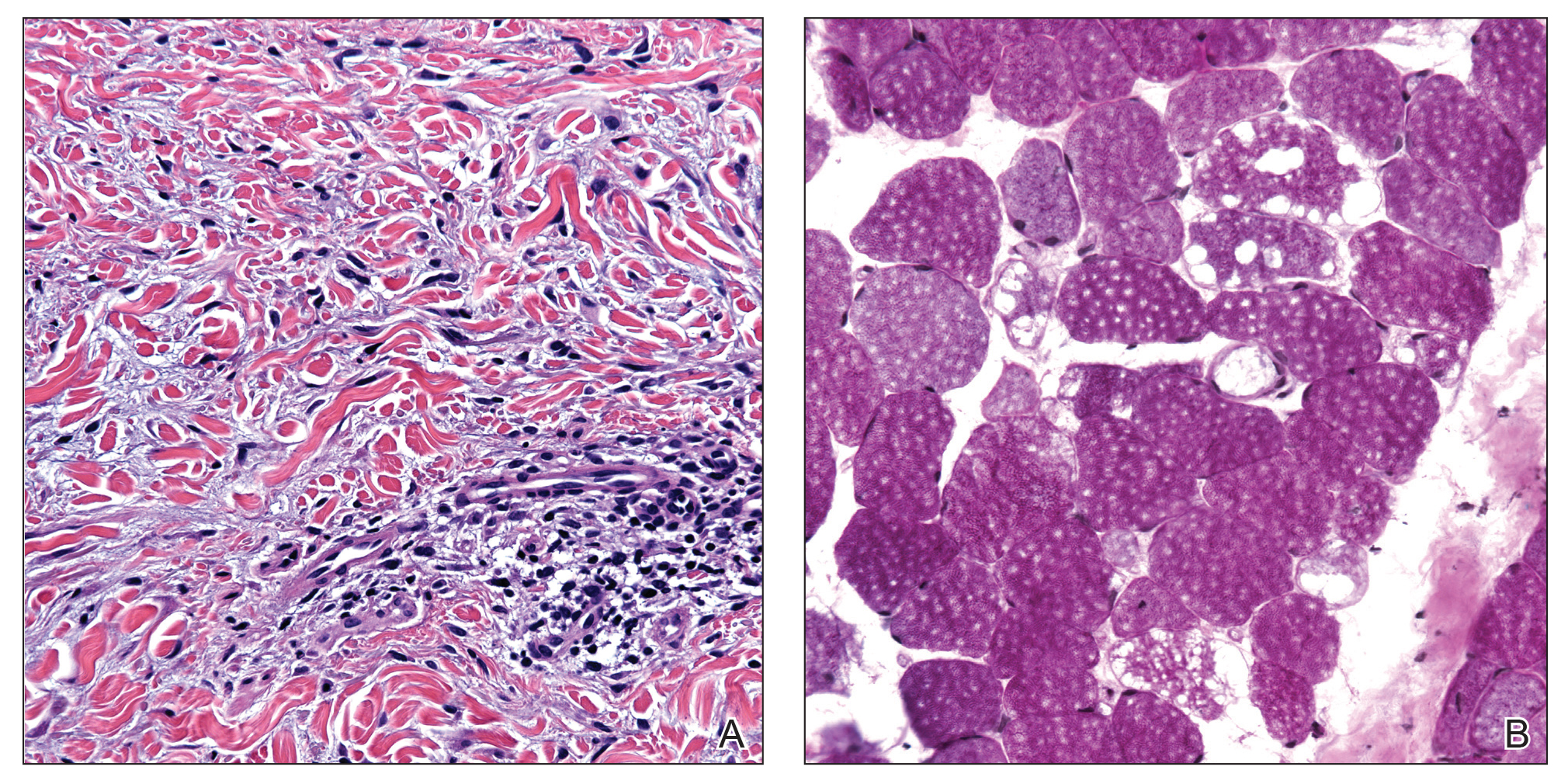

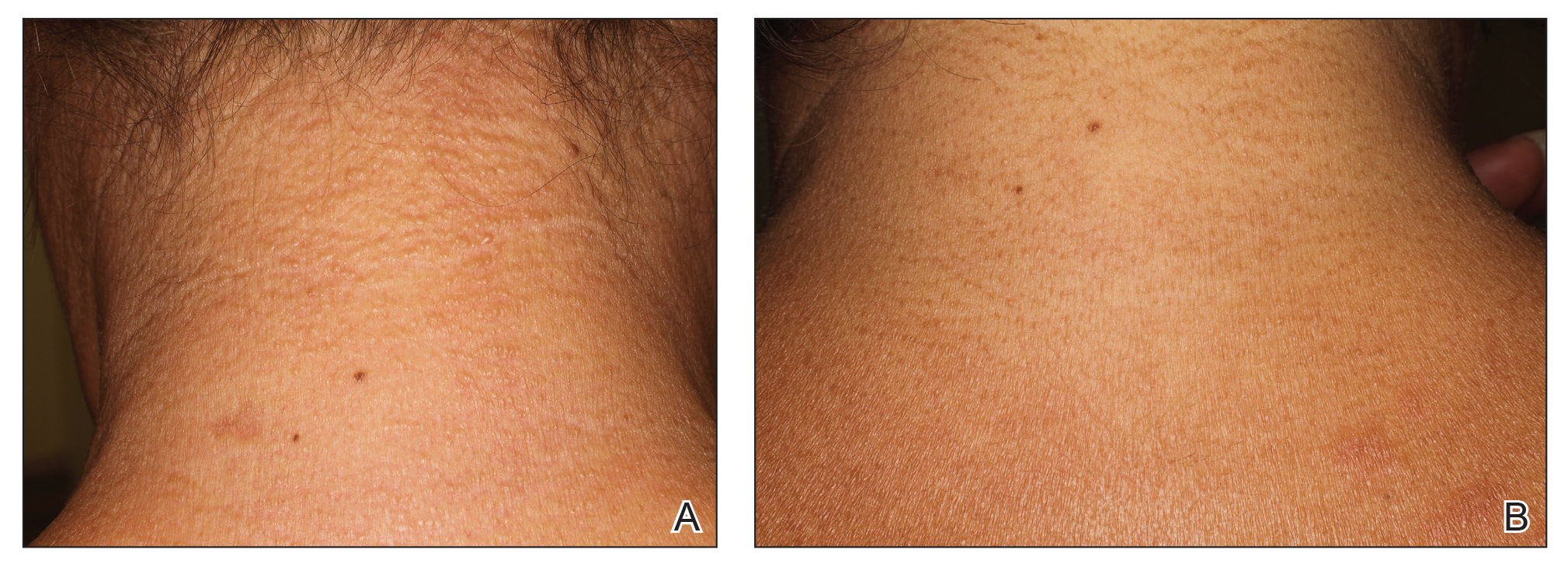

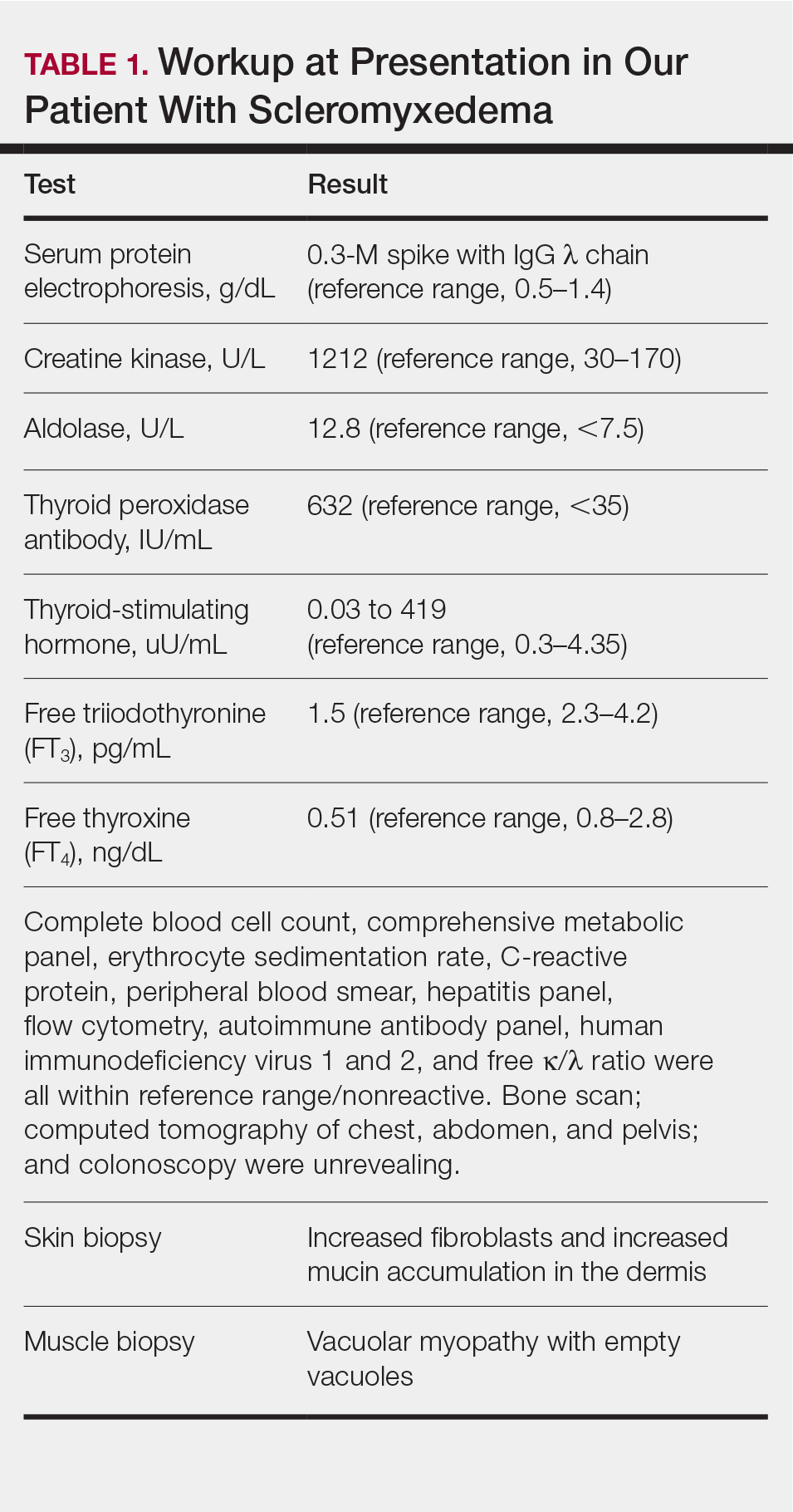

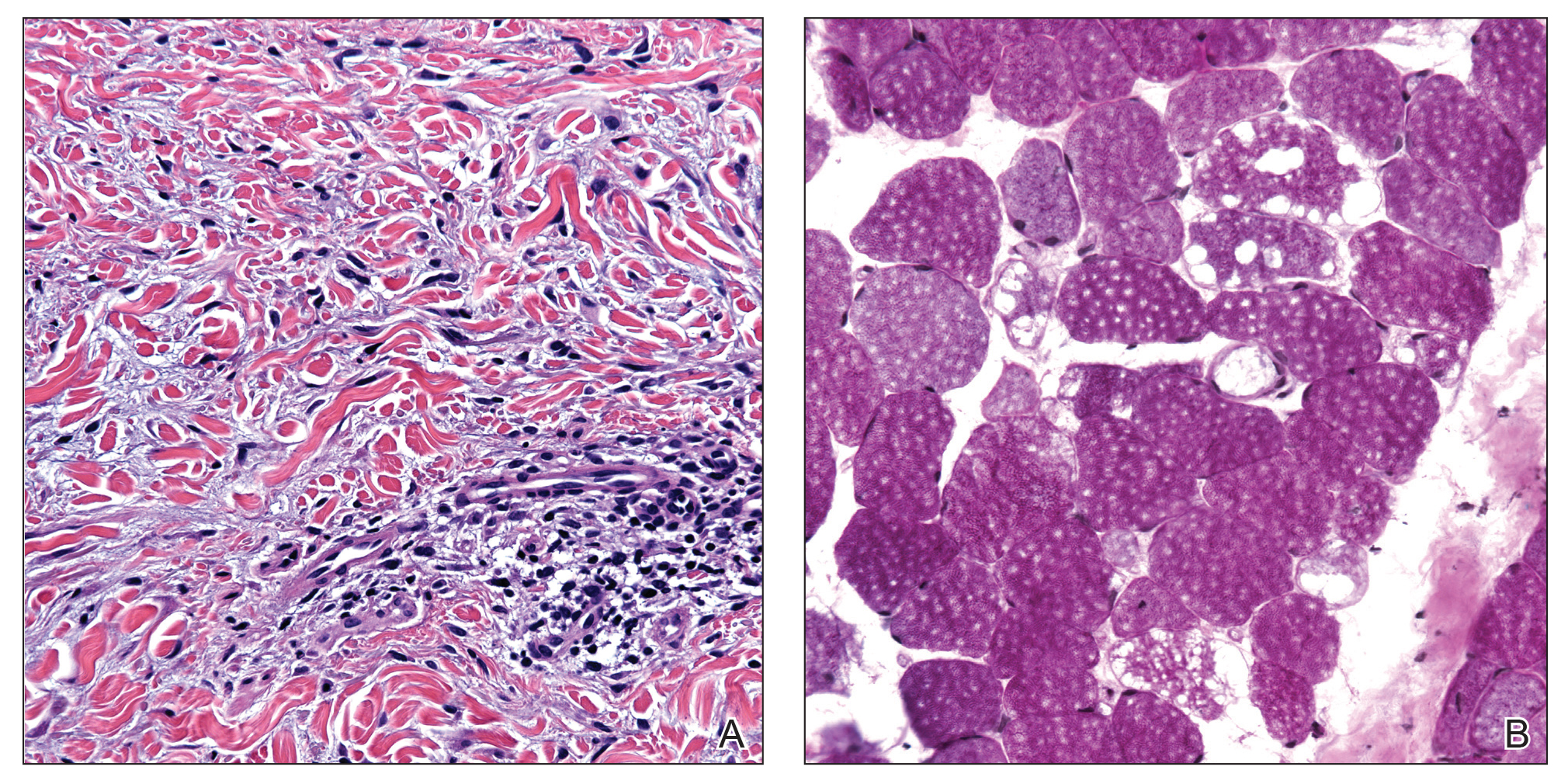

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

Practice Points

- Scleromyxedema (SM) is progressive disease of unknown etiology with unpredictable behavior.

- Systemic manifestations associated with SM can cause serious morbidity and mortality.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin is the most effective treatment modality in SM.

- The presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.