User login

More on Cognitive Screening Tools: Response to an Interested Reader

Regarding our January 2013 CE/CME activity (Segal-Gidan FI. Cognitive screening tools. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):12-18), Lieutenant Colonel Scott A. Arcand, PA-C, LTC, SP, of the Army National Guard* asked for more information: an assessment of the described tools in terms of six core neuropsychiatric domains; and more about scoring systems for the very useful clock drawing test.

Q: At the end of the section, “Which Test to Use?”, the author states that a comprehensive screening instrument would assess six core neuropsychiatric domains, but then does not assess the six instruments discussed in the article against these criteria. I would have found this a very helpful discussion. I also think it would be helpful to have a table that showed which assessments met each criterion. If a meta-analysis were done to evaluate and compare these instruments, it would lead the drive to improved tools.

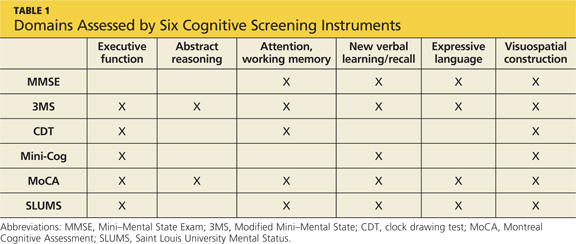

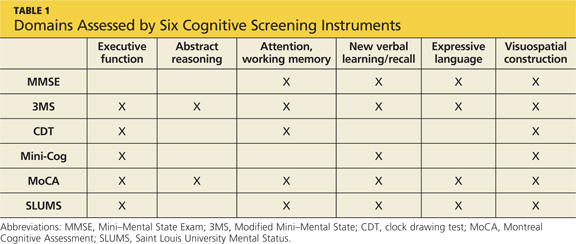

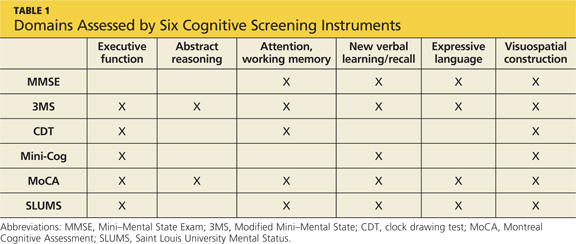

In the original article, Table 2 (“Brief Cognitive Assessment Instruments”) includes a column listing the cognitive functions assessed by each of the six screening tools reviewed/discussed. Each of these components corresponds to one or more neuropsychological domain, and I refer the reader to the referenced paper for a more detailed discussion of this (Cullen et al,1 2007). Two screening tests, the Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS) and the Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE) include—at least in part—each of the suggested six core neuropsychological domains. These two tests would be considered the most complete according to the standard of the six core neuropsychological domains; however, they also take the most time to administer (10 to 15 minutes), as noted in the original article’s Table 2.

The Clinician’s Choice

For clinicians deciding which test is most appropriate to use as a screening tool in their practice or for an individual patient, they should weigh several factors, including the length and time to administer, as well as the domains assessed. Table 1, I hope, will more directly address the reader’s issue of which neuropsychological domain is assessed in the test items for each of the cognitive screening tests reviewed in the article.

Q: Regarding the clock drawing test (CDT), the author makes two statements: that there are multiple scoring systems for the CDT, and that the CDT has been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety. I would be interested to see at least one of these scoring systems. Additionally, how low a score on the CDT would it take to indicate that a patient is (or could be) unfit for driving?

Scoring systems for the CDT, varying from four- to 20-point scales, evaluate accuracy of components and traits of the drawing, or they categorize errors. In a 2001 overview of various CDT scoring systems, Peter Braunberger2 included a detailed review of two scoring strategies:

A simple scoring system created by Shua et al,3 in which one point is awarded for each of the following:

• Approximate drawing of the clock

• Presence of numbers in the correct sequence

• Correct spatial arrangement of numbers

• Presence of clock hands

• Hands showing the approximate correct time

• Hands depicting the exact time

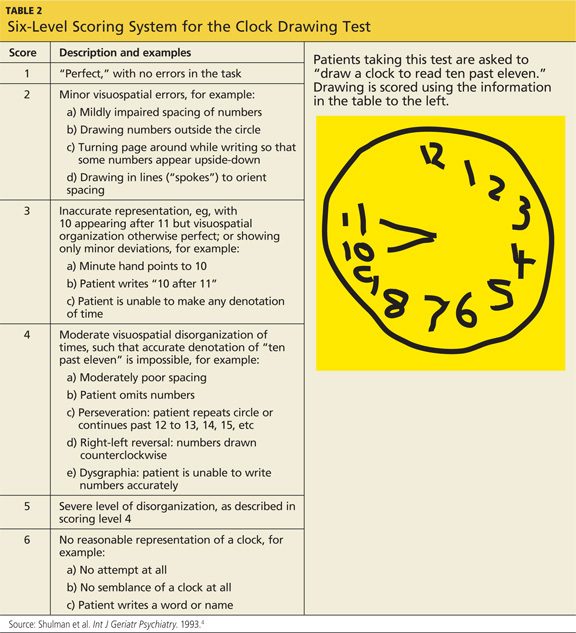

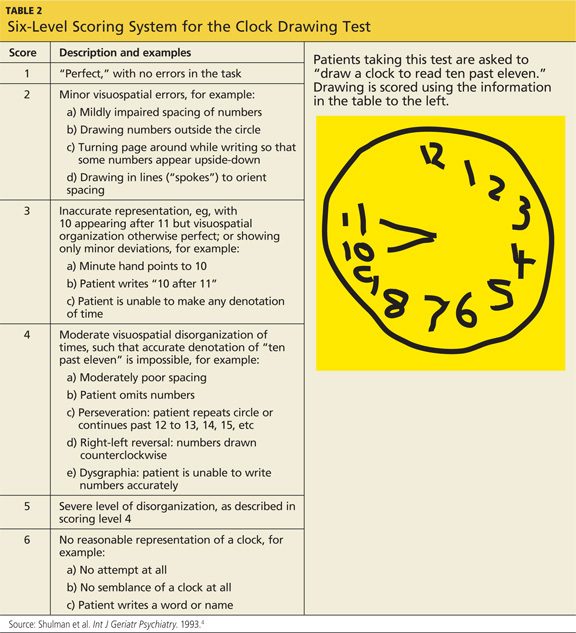

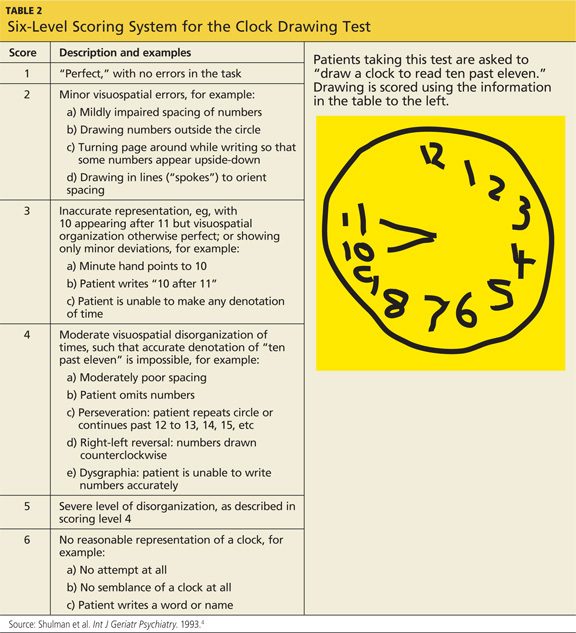

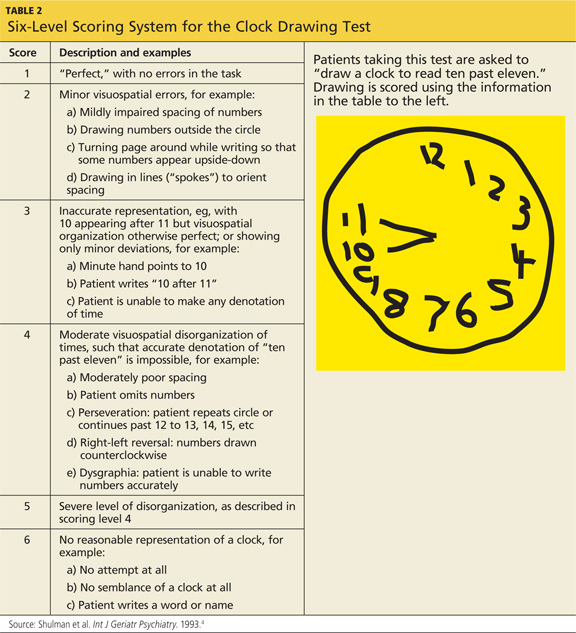

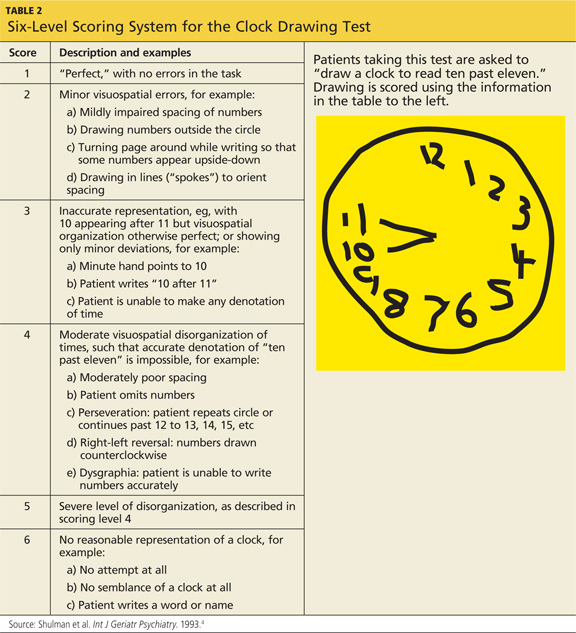

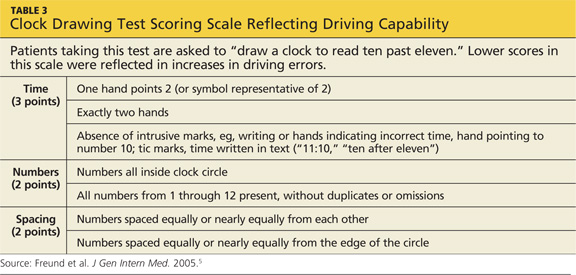

In the second scoring system, proposed by Shulman et al,4 six different scores are possible (see Table 24).

Driver Safety

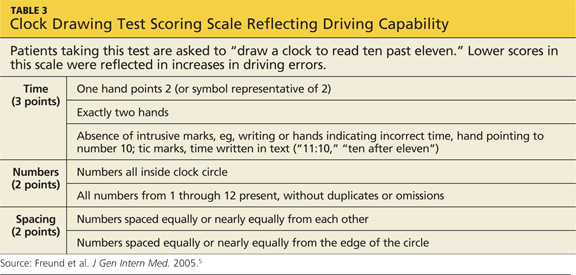

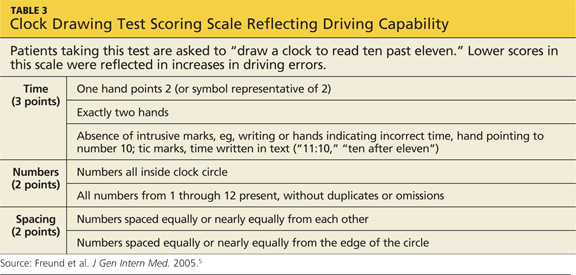

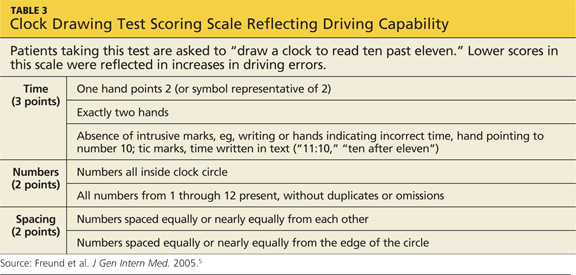

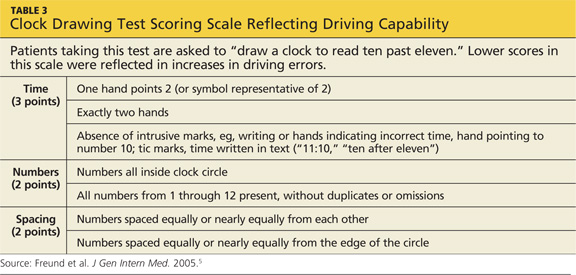

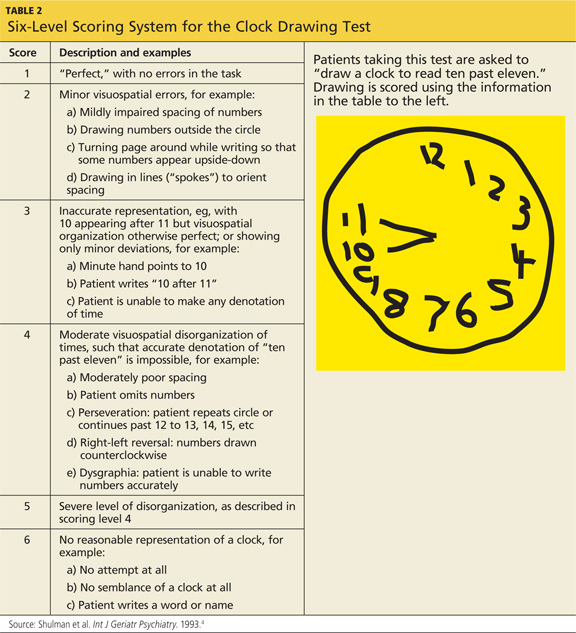

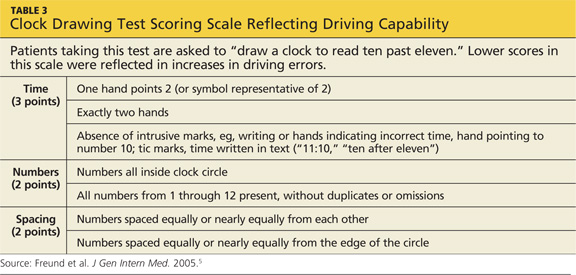

Regarding use of the CDT as a predictor of driver safety, Freund and colleagues5 conducted a study of clock drawing and simulator driving assessment. In addition to finding four CDT scoring scales comparable, they discovered that as patients’ CDT scores decreased, the number of “driving errors” they made increased. As shown in Table 3,5 the researchers’ CDT scoring system focused on time, numbers, and spacing, with a maximum score of seven points.

References

1. Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

2. Braunberger P. The clock drawing test (2001) www.neurosurvival.ca/ClinicalAssistant/scales/clock_drawing_test.htm. Accessed March 23, 2013.

3. Shua-Haim J, Koppuzha G, Gross J. A simple scoring system for clock drawing in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:335.

4. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487-496.

5. Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240-244.

*Scott A. Arcandis currently serving on active duty as a member of the Army National Guard. The statements expressed here are those of the writer and do not constitute official policy of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Guard Bureau.

Regarding our January 2013 CE/CME activity (Segal-Gidan FI. Cognitive screening tools. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):12-18), Lieutenant Colonel Scott A. Arcand, PA-C, LTC, SP, of the Army National Guard* asked for more information: an assessment of the described tools in terms of six core neuropsychiatric domains; and more about scoring systems for the very useful clock drawing test.

Q: At the end of the section, “Which Test to Use?”, the author states that a comprehensive screening instrument would assess six core neuropsychiatric domains, but then does not assess the six instruments discussed in the article against these criteria. I would have found this a very helpful discussion. I also think it would be helpful to have a table that showed which assessments met each criterion. If a meta-analysis were done to evaluate and compare these instruments, it would lead the drive to improved tools.

In the original article, Table 2 (“Brief Cognitive Assessment Instruments”) includes a column listing the cognitive functions assessed by each of the six screening tools reviewed/discussed. Each of these components corresponds to one or more neuropsychological domain, and I refer the reader to the referenced paper for a more detailed discussion of this (Cullen et al,1 2007). Two screening tests, the Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS) and the Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE) include—at least in part—each of the suggested six core neuropsychological domains. These two tests would be considered the most complete according to the standard of the six core neuropsychological domains; however, they also take the most time to administer (10 to 15 minutes), as noted in the original article’s Table 2.

The Clinician’s Choice

For clinicians deciding which test is most appropriate to use as a screening tool in their practice or for an individual patient, they should weigh several factors, including the length and time to administer, as well as the domains assessed. Table 1, I hope, will more directly address the reader’s issue of which neuropsychological domain is assessed in the test items for each of the cognitive screening tests reviewed in the article.

Q: Regarding the clock drawing test (CDT), the author makes two statements: that there are multiple scoring systems for the CDT, and that the CDT has been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety. I would be interested to see at least one of these scoring systems. Additionally, how low a score on the CDT would it take to indicate that a patient is (or could be) unfit for driving?

Scoring systems for the CDT, varying from four- to 20-point scales, evaluate accuracy of components and traits of the drawing, or they categorize errors. In a 2001 overview of various CDT scoring systems, Peter Braunberger2 included a detailed review of two scoring strategies:

A simple scoring system created by Shua et al,3 in which one point is awarded for each of the following:

• Approximate drawing of the clock

• Presence of numbers in the correct sequence

• Correct spatial arrangement of numbers

• Presence of clock hands

• Hands showing the approximate correct time

• Hands depicting the exact time

In the second scoring system, proposed by Shulman et al,4 six different scores are possible (see Table 24).

Driver Safety

Regarding use of the CDT as a predictor of driver safety, Freund and colleagues5 conducted a study of clock drawing and simulator driving assessment. In addition to finding four CDT scoring scales comparable, they discovered that as patients’ CDT scores decreased, the number of “driving errors” they made increased. As shown in Table 3,5 the researchers’ CDT scoring system focused on time, numbers, and spacing, with a maximum score of seven points.

References

1. Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

2. Braunberger P. The clock drawing test (2001) www.neurosurvival.ca/ClinicalAssistant/scales/clock_drawing_test.htm. Accessed March 23, 2013.

3. Shua-Haim J, Koppuzha G, Gross J. A simple scoring system for clock drawing in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:335.

4. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487-496.

5. Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240-244.

*Scott A. Arcandis currently serving on active duty as a member of the Army National Guard. The statements expressed here are those of the writer and do not constitute official policy of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Guard Bureau.

Regarding our January 2013 CE/CME activity (Segal-Gidan FI. Cognitive screening tools. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):12-18), Lieutenant Colonel Scott A. Arcand, PA-C, LTC, SP, of the Army National Guard* asked for more information: an assessment of the described tools in terms of six core neuropsychiatric domains; and more about scoring systems for the very useful clock drawing test.

Q: At the end of the section, “Which Test to Use?”, the author states that a comprehensive screening instrument would assess six core neuropsychiatric domains, but then does not assess the six instruments discussed in the article against these criteria. I would have found this a very helpful discussion. I also think it would be helpful to have a table that showed which assessments met each criterion. If a meta-analysis were done to evaluate and compare these instruments, it would lead the drive to improved tools.

In the original article, Table 2 (“Brief Cognitive Assessment Instruments”) includes a column listing the cognitive functions assessed by each of the six screening tools reviewed/discussed. Each of these components corresponds to one or more neuropsychological domain, and I refer the reader to the referenced paper for a more detailed discussion of this (Cullen et al,1 2007). Two screening tests, the Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS) and the Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE) include—at least in part—each of the suggested six core neuropsychological domains. These two tests would be considered the most complete according to the standard of the six core neuropsychological domains; however, they also take the most time to administer (10 to 15 minutes), as noted in the original article’s Table 2.

The Clinician’s Choice

For clinicians deciding which test is most appropriate to use as a screening tool in their practice or for an individual patient, they should weigh several factors, including the length and time to administer, as well as the domains assessed. Table 1, I hope, will more directly address the reader’s issue of which neuropsychological domain is assessed in the test items for each of the cognitive screening tests reviewed in the article.

Q: Regarding the clock drawing test (CDT), the author makes two statements: that there are multiple scoring systems for the CDT, and that the CDT has been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety. I would be interested to see at least one of these scoring systems. Additionally, how low a score on the CDT would it take to indicate that a patient is (or could be) unfit for driving?

Scoring systems for the CDT, varying from four- to 20-point scales, evaluate accuracy of components and traits of the drawing, or they categorize errors. In a 2001 overview of various CDT scoring systems, Peter Braunberger2 included a detailed review of two scoring strategies:

A simple scoring system created by Shua et al,3 in which one point is awarded for each of the following:

• Approximate drawing of the clock

• Presence of numbers in the correct sequence

• Correct spatial arrangement of numbers

• Presence of clock hands

• Hands showing the approximate correct time

• Hands depicting the exact time

In the second scoring system, proposed by Shulman et al,4 six different scores are possible (see Table 24).

Driver Safety

Regarding use of the CDT as a predictor of driver safety, Freund and colleagues5 conducted a study of clock drawing and simulator driving assessment. In addition to finding four CDT scoring scales comparable, they discovered that as patients’ CDT scores decreased, the number of “driving errors” they made increased. As shown in Table 3,5 the researchers’ CDT scoring system focused on time, numbers, and spacing, with a maximum score of seven points.

References

1. Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

2. Braunberger P. The clock drawing test (2001) www.neurosurvival.ca/ClinicalAssistant/scales/clock_drawing_test.htm. Accessed March 23, 2013.

3. Shua-Haim J, Koppuzha G, Gross J. A simple scoring system for clock drawing in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:335.

4. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487-496.

5. Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240-244.

*Scott A. Arcandis currently serving on active duty as a member of the Army National Guard. The statements expressed here are those of the writer and do not constitute official policy of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Guard Bureau.

More on Cognitive Screening Tools

Regarding our January 2013 CE/CME activity (Segal-Gidan FI. Cognitive screening tools. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):12-18), Lieutenant Colonel Scott A. Arcand, PA-C, LTC, SP, of the Army National Guard* asked for more information: an assessment of the described tools in terms of six core neuropsychiatric domains; and more about scoring systems for the very useful clock drawing test.

Q: At the end of the section, "Which Test to Use?", the author states that a comprehensive screening instrument would assess six core neuropsychiatric domains, but then does not assess the six instruments discussed in the article against these criteria. I would have found this a very helpful discussion. I also think it would be helpful to have a table that showed which assessments met each criterion. If a meta-analysis were done to evaluate and compare these instruments, it would lead the drive to improved tools.

In the original article, Table 2 ("Brief Cognitive Assessment Instruments") includes a column listing the cognitive functions assessed by each of the six screening tools reviewed/discussed. Each of these components corresponds to one or more neuropsychological domain, and I refer the reader to the referenced paper for a more detailed discussion of this (Cullen et al,1 2007). Two screening tests, the Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS) and the Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE) include—at least in part—each of the suggested six core neuropsychological domains. These two tests would be considered the most complete according to the standard of the six core neuropsychological domains; however, they also take the most time to administer (10 to 15 minutes), as noted in the original article's Table 2.

The Clinician's Choice

For clinicians deciding which test is most appropriate to use as a screening tool in their practice or for an individual patient, they should weigh several factors, including the length and time to administer, as well as the domains assessed. Table 1, I hope, will more directly address the reader's issue of which neuropsychological domain is assessed in the test items for each of the cognitive screening tests reviewed in the article.

Q: Regarding the clock drawing test (CDT), the author makes two statements: that there are multiple scoring systems for the CDT, and that the CDT has been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety. I would be interested to see at least one of these scoring systems. Additionally, how low a score on the CDT would it take to indicate that a patient is (or could be) unfit for driving?

Scoring systems for the CDT, varying from four- to 20-point scales, evaluate accuracy of components and traits of the drawing, or they categorize errors. In a 2001 overview of various CDT scoring systems, Peter Braunberger2 included a detailed review of two scoring strategies:

A simple scoring system created by Shua et al,3 in which one point is awarded for each of the following:

• Approximate drawing of the clock

• Presence of numbers in the correct sequence

• Correct spatial arrangement of numbers

• Presence of clock hands

• Hands showing the approximate correct time

• Hands depicting the exact time

In the second scoring system, proposed by Shulman et al,4 six different scores are possible (see Table 24).

Driver Safety

Regarding use of the CDT as a predictor of driver safety, Freund and colleagues5 conducted a study of clock drawing and simulator driving assessment. In addition to finding four CDT scoring scales comparable, they discovered that as patients' CDT scores decreased, the number of "driving errors" they made increased. As shown in Table 3,5 the researchers' CDT scoring system focused on time, numbers, and spacing, with a maximum score of seven points.

References

1. Cullen B, O'Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

2. Braunberger P. The clock drawing test (2001) www.neurosurvival.ca/ClinicalAssistant/scales/clock_drawing_test.htm. Accessed March 23, 2013.

3. Shua-Haim J, Koppuzha G, Gross J. A simple scoring system for clock drawing in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:335.

4. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487-496.

5. Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240-244.

*Scott A. Arcandis currently serving on active duty as a member of the Army National Guard. The statements expressed here are those of the writer and do not constitute official policy of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Guard Bureau.

Regarding our January 2013 CE/CME activity (Segal-Gidan FI. Cognitive screening tools. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):12-18), Lieutenant Colonel Scott A. Arcand, PA-C, LTC, SP, of the Army National Guard* asked for more information: an assessment of the described tools in terms of six core neuropsychiatric domains; and more about scoring systems for the very useful clock drawing test.

Q: At the end of the section, "Which Test to Use?", the author states that a comprehensive screening instrument would assess six core neuropsychiatric domains, but then does not assess the six instruments discussed in the article against these criteria. I would have found this a very helpful discussion. I also think it would be helpful to have a table that showed which assessments met each criterion. If a meta-analysis were done to evaluate and compare these instruments, it would lead the drive to improved tools.

In the original article, Table 2 ("Brief Cognitive Assessment Instruments") includes a column listing the cognitive functions assessed by each of the six screening tools reviewed/discussed. Each of these components corresponds to one or more neuropsychological domain, and I refer the reader to the referenced paper for a more detailed discussion of this (Cullen et al,1 2007). Two screening tests, the Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS) and the Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE) include—at least in part—each of the suggested six core neuropsychological domains. These two tests would be considered the most complete according to the standard of the six core neuropsychological domains; however, they also take the most time to administer (10 to 15 minutes), as noted in the original article's Table 2.

The Clinician's Choice

For clinicians deciding which test is most appropriate to use as a screening tool in their practice or for an individual patient, they should weigh several factors, including the length and time to administer, as well as the domains assessed. Table 1, I hope, will more directly address the reader's issue of which neuropsychological domain is assessed in the test items for each of the cognitive screening tests reviewed in the article.

Q: Regarding the clock drawing test (CDT), the author makes two statements: that there are multiple scoring systems for the CDT, and that the CDT has been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety. I would be interested to see at least one of these scoring systems. Additionally, how low a score on the CDT would it take to indicate that a patient is (or could be) unfit for driving?

Scoring systems for the CDT, varying from four- to 20-point scales, evaluate accuracy of components and traits of the drawing, or they categorize errors. In a 2001 overview of various CDT scoring systems, Peter Braunberger2 included a detailed review of two scoring strategies:

A simple scoring system created by Shua et al,3 in which one point is awarded for each of the following:

• Approximate drawing of the clock

• Presence of numbers in the correct sequence

• Correct spatial arrangement of numbers

• Presence of clock hands

• Hands showing the approximate correct time

• Hands depicting the exact time

In the second scoring system, proposed by Shulman et al,4 six different scores are possible (see Table 24).

Driver Safety

Regarding use of the CDT as a predictor of driver safety, Freund and colleagues5 conducted a study of clock drawing and simulator driving assessment. In addition to finding four CDT scoring scales comparable, they discovered that as patients' CDT scores decreased, the number of "driving errors" they made increased. As shown in Table 3,5 the researchers' CDT scoring system focused on time, numbers, and spacing, with a maximum score of seven points.

References

1. Cullen B, O'Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

2. Braunberger P. The clock drawing test (2001) www.neurosurvival.ca/ClinicalAssistant/scales/clock_drawing_test.htm. Accessed March 23, 2013.

3. Shua-Haim J, Koppuzha G, Gross J. A simple scoring system for clock drawing in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:335.

4. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487-496.

5. Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240-244.

*Scott A. Arcandis currently serving on active duty as a member of the Army National Guard. The statements expressed here are those of the writer and do not constitute official policy of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Guard Bureau.

Regarding our January 2013 CE/CME activity (Segal-Gidan FI. Cognitive screening tools. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):12-18), Lieutenant Colonel Scott A. Arcand, PA-C, LTC, SP, of the Army National Guard* asked for more information: an assessment of the described tools in terms of six core neuropsychiatric domains; and more about scoring systems for the very useful clock drawing test.

Q: At the end of the section, "Which Test to Use?", the author states that a comprehensive screening instrument would assess six core neuropsychiatric domains, but then does not assess the six instruments discussed in the article against these criteria. I would have found this a very helpful discussion. I also think it would be helpful to have a table that showed which assessments met each criterion. If a meta-analysis were done to evaluate and compare these instruments, it would lead the drive to improved tools.

In the original article, Table 2 ("Brief Cognitive Assessment Instruments") includes a column listing the cognitive functions assessed by each of the six screening tools reviewed/discussed. Each of these components corresponds to one or more neuropsychological domain, and I refer the reader to the referenced paper for a more detailed discussion of this (Cullen et al,1 2007). Two screening tests, the Modified Mini–Mental State Exam (3MS) and the Mini–Mental State Exam (MMSE) include—at least in part—each of the suggested six core neuropsychological domains. These two tests would be considered the most complete according to the standard of the six core neuropsychological domains; however, they also take the most time to administer (10 to 15 minutes), as noted in the original article's Table 2.

The Clinician's Choice

For clinicians deciding which test is most appropriate to use as a screening tool in their practice or for an individual patient, they should weigh several factors, including the length and time to administer, as well as the domains assessed. Table 1, I hope, will more directly address the reader's issue of which neuropsychological domain is assessed in the test items for each of the cognitive screening tests reviewed in the article.

Q: Regarding the clock drawing test (CDT), the author makes two statements: that there are multiple scoring systems for the CDT, and that the CDT has been shown to be highly predictive of driver safety. I would be interested to see at least one of these scoring systems. Additionally, how low a score on the CDT would it take to indicate that a patient is (or could be) unfit for driving?

Scoring systems for the CDT, varying from four- to 20-point scales, evaluate accuracy of components and traits of the drawing, or they categorize errors. In a 2001 overview of various CDT scoring systems, Peter Braunberger2 included a detailed review of two scoring strategies:

A simple scoring system created by Shua et al,3 in which one point is awarded for each of the following:

• Approximate drawing of the clock

• Presence of numbers in the correct sequence

• Correct spatial arrangement of numbers

• Presence of clock hands

• Hands showing the approximate correct time

• Hands depicting the exact time

In the second scoring system, proposed by Shulman et al,4 six different scores are possible (see Table 24).

Driver Safety

Regarding use of the CDT as a predictor of driver safety, Freund and colleagues5 conducted a study of clock drawing and simulator driving assessment. In addition to finding four CDT scoring scales comparable, they discovered that as patients' CDT scores decreased, the number of "driving errors" they made increased. As shown in Table 3,5 the researchers' CDT scoring system focused on time, numbers, and spacing, with a maximum score of seven points.

References

1. Cullen B, O'Neill B, Evans JJ, et al. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790-799.

2. Braunberger P. The clock drawing test (2001) www.neurosurvival.ca/ClinicalAssistant/scales/clock_drawing_test.htm. Accessed March 23, 2013.

3. Shua-Haim J, Koppuzha G, Gross J. A simple scoring system for clock drawing in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:335.

4. Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA. Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:487-496.

5. Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240-244.

*Scott A. Arcandis currently serving on active duty as a member of the Army National Guard. The statements expressed here are those of the writer and do not constitute official policy of the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Guard Bureau.

A Clinician's View: Fundamental Truths

Last month marked 30 years since I graduated from the training program that led to my becoming a PA. I was in a short-lived program (we were called Health Associates, or HA-HA for short) at the Johns Hopkins University School of Health Services, which is no longer in existence. The school was unique and in many ways ahead of its time. The majority of my classmates had previous degrees, at a time when most programs offered only certification and a few associate and/or baccalaureate degrees. (No one dared dream of a master’s degree.) We all had prior extensive experience in health care, an entrance prerequisite. The program was also unusual in that only two of my classmates came from military backgrounds and most were female.

In the three decades since then, I’ve taken (and passed) the PA recertification exam more times than I can remember. And I have seen so many amazing changes in medicine and our health care system.

At the same time I have found that certain fundamental truths never change. This would be my list:

1. Listen to the patient. Listening is as important as talking—maybe more so. Focus on what the patient’s concerns are and address them. Leave your agenda outside the door. Caring for an individual requires not just knowledge but empathetic understanding, which can only come from taking the time to listen, to learn from patients what they are experiencing, to hear their concerns. In today’s busy practice settings, taking a few minutes to listen can go a long way. (And studies repeatedly show that providers who spend time with their patients are much less likely to be sued.)

2. Most of the diagnosis comes from the history. Taking a thorough history is key to both building rapport with your patient and getting the vital information necessary to make the right decisions that will eventually lead to the right diagnosis and the right treatment plan. In today’s high-tech environment, the importance of obtaining accurate information from a patient (or a surrogate) is too often discounted. It’s essential.

3. Think horses, not zebras. Look for the usual, the common, not the exotic. Most of medicine is routine, regardless of the practice setting. In my work caring for the elderly, I have found that simple, treatable conditions (constipation, dehydration, bladder infections, adverse drug reactions/interactions) are often the underlying cause of a patient’s confusion, fall, or deterioration. On the other hand, in my work at a large, publicly funded rehabilitation hospital, I often joke that the hoofbeats aren’t zebras but unicorns. The unusual, I have come to learn, does occur and can sneak up on you, and it seems to be found more often among the disenfranchised and ever-growing uninsured and underinsured populations.

4. Respect cultural differences. Everyone brings their life experiences to the health care setting. These experiences influence how individuals react to changes in their health and how they interact with providers and the health care system. Sometimes cultural differences are obvious—when the patient doesn’t speak the same language as the provider, for example, or the patient is a recent immigrant. Cultural differences can, however, be more subtle, as evidenced by the increasing use of alternative health care practices by people of all backgrounds. Often, it is the lack of understanding of cultural differences that leads to problems in patient-provider relationships, with patients labeled as “noncompliant” and providers as “uncaring.”

5. Admit what you don’t know. When I was a student, this was easy, because I really didn’t know much. The reality is there are always things I don’t know, because either I never learned them, what I learned is outdated, or I’ve forgotten what I once knew. Over the years, as my medical knowledge and experience have grown, I have become ever more aware of how much I don’t know. With the exponential growth in scientific knowledge, it is difficult to remain current in all areas of medicine. For those in clinical practice, the basic knowledge and skills learned in school continue to serve us well, but often it is the students who teach us about the newest technology or leap in scientific understanding. I learned early on never to hesitate to say, “I’m not sure what’s going on here, let me talk with the physician”—a phrase I continue to use regularly.

6. Describe what you see, hear, and feel on the physical exam. The skills used in the physical examination are the basic tools of a medical provider, and the laying on of hands is a key component of the patient-provider relationship. Although it is rapidly being subsumed by technology, the knowledge gained from a good physical exam is not easily replaced by a machine. By honing one’s skills in observation, auscultation, and palpation, a provider can more judiciously determine what additional diagnostic testing is appropriate. Trust your senses and record what you see, hear, and feel, not what was written down by a prior examiner or anyone else.

7. What you write down is permanent. If you don’t write it down, it didn’t happen. The medical record, whether written or electronic, is a legal document, a means of communication between providers and often an invaluable memory aid. I review medical record notes daily, some written by myself, others by my supervising physician or other providers, to learn about a patient’s history and physical exam findings. If the notes are illegible or incomplete, then my knowledge is incomplete. No one can recall every patient or the details of every patient encounter. Patients often see multiple providers and frequently move between providers and settings, making the medical record more vital than ever to continuity of care and prevention of errors.

8. Don’t worry about learning all the drugs—they’ll change. Boy, is this one true. I can think of only a handful of drugs that I learned about in school that are still used in the same dosages for the same conditions (for example, digoxin, furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide). Some drugs that had fallen out of favor have actually been found to be beneficial and are now back in use (spironolactone and hydralazine for heart failure, oral hypoglycemics for type 2 diabetes). Other classes of drugs didn’t even exist when I was in school (antiretrovirals, SSRIs, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers, to name a few). Pharmaceutical therapeutics has gotten much more complicated, with dozens of new drugs approved annually by the FDA—not to mention all the medications that are now OTC and all the vitamins and supplements that people take.

9. It takes a team to deliver health care. Work with others; use their talents and expertise. In the 1970s, the word “team” in medicine was considered radical. Now, health care administrators, planners, and systems analysts all talk about teams as the way to improve care in every setting. There are stroke teams, cardiac bypass teams, home care teams. It was integral to my PA training to learn to work with others. These skills have continued to serve PAs well as team care has become the norm.

10. Medical knowledge is ever-changing. Keeping up with changes in our ever-evolving health care system requires dedication. Learning how to review and synthesize complex information and deciding which sources (journals, Web sites) are valid and relevant to one’s work are essential skills. They were integral to my early training, and they are just as important today to keeping my practice current.

Thinking back to my early years in the Johns Hopkins program, I remember the multidisciplinary faculty of physicians, PAs, basic scientists, pharmacists, and social scientists. We were videotaped regularly and had a required assignment as patient advocates in the emergency room. We studied art and literature as it related to health, along with microbiology and pharmacology. In the ensuing years, a significant number of graduates, like me, have pursued additional education and training, going on to earn doctorate degrees in various fields.

It was an intense two years that I recall fondly and that has definitely served me well. The faculty were visionaries and wonderful mentors. I hope those of you in training today will be able to say the same in the decades to come and that the fundamental truths I have listed here will help guide you in your journey.

Freddi I. Segal-Gidan is Director of the Alzheimer’s Research Center of California at the Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center in Downey, California, and Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles. She is a member of the Clinician Reviews editorial board.

Last month marked 30 years since I graduated from the training program that led to my becoming a PA. I was in a short-lived program (we were called Health Associates, or HA-HA for short) at the Johns Hopkins University School of Health Services, which is no longer in existence. The school was unique and in many ways ahead of its time. The majority of my classmates had previous degrees, at a time when most programs offered only certification and a few associate and/or baccalaureate degrees. (No one dared dream of a master’s degree.) We all had prior extensive experience in health care, an entrance prerequisite. The program was also unusual in that only two of my classmates came from military backgrounds and most were female.

In the three decades since then, I’ve taken (and passed) the PA recertification exam more times than I can remember. And I have seen so many amazing changes in medicine and our health care system.

At the same time I have found that certain fundamental truths never change. This would be my list:

1. Listen to the patient. Listening is as important as talking—maybe more so. Focus on what the patient’s concerns are and address them. Leave your agenda outside the door. Caring for an individual requires not just knowledge but empathetic understanding, which can only come from taking the time to listen, to learn from patients what they are experiencing, to hear their concerns. In today’s busy practice settings, taking a few minutes to listen can go a long way. (And studies repeatedly show that providers who spend time with their patients are much less likely to be sued.)

2. Most of the diagnosis comes from the history. Taking a thorough history is key to both building rapport with your patient and getting the vital information necessary to make the right decisions that will eventually lead to the right diagnosis and the right treatment plan. In today’s high-tech environment, the importance of obtaining accurate information from a patient (or a surrogate) is too often discounted. It’s essential.

3. Think horses, not zebras. Look for the usual, the common, not the exotic. Most of medicine is routine, regardless of the practice setting. In my work caring for the elderly, I have found that simple, treatable conditions (constipation, dehydration, bladder infections, adverse drug reactions/interactions) are often the underlying cause of a patient’s confusion, fall, or deterioration. On the other hand, in my work at a large, publicly funded rehabilitation hospital, I often joke that the hoofbeats aren’t zebras but unicorns. The unusual, I have come to learn, does occur and can sneak up on you, and it seems to be found more often among the disenfranchised and ever-growing uninsured and underinsured populations.

4. Respect cultural differences. Everyone brings their life experiences to the health care setting. These experiences influence how individuals react to changes in their health and how they interact with providers and the health care system. Sometimes cultural differences are obvious—when the patient doesn’t speak the same language as the provider, for example, or the patient is a recent immigrant. Cultural differences can, however, be more subtle, as evidenced by the increasing use of alternative health care practices by people of all backgrounds. Often, it is the lack of understanding of cultural differences that leads to problems in patient-provider relationships, with patients labeled as “noncompliant” and providers as “uncaring.”

5. Admit what you don’t know. When I was a student, this was easy, because I really didn’t know much. The reality is there are always things I don’t know, because either I never learned them, what I learned is outdated, or I’ve forgotten what I once knew. Over the years, as my medical knowledge and experience have grown, I have become ever more aware of how much I don’t know. With the exponential growth in scientific knowledge, it is difficult to remain current in all areas of medicine. For those in clinical practice, the basic knowledge and skills learned in school continue to serve us well, but often it is the students who teach us about the newest technology or leap in scientific understanding. I learned early on never to hesitate to say, “I’m not sure what’s going on here, let me talk with the physician”—a phrase I continue to use regularly.

6. Describe what you see, hear, and feel on the physical exam. The skills used in the physical examination are the basic tools of a medical provider, and the laying on of hands is a key component of the patient-provider relationship. Although it is rapidly being subsumed by technology, the knowledge gained from a good physical exam is not easily replaced by a machine. By honing one’s skills in observation, auscultation, and palpation, a provider can more judiciously determine what additional diagnostic testing is appropriate. Trust your senses and record what you see, hear, and feel, not what was written down by a prior examiner or anyone else.

7. What you write down is permanent. If you don’t write it down, it didn’t happen. The medical record, whether written or electronic, is a legal document, a means of communication between providers and often an invaluable memory aid. I review medical record notes daily, some written by myself, others by my supervising physician or other providers, to learn about a patient’s history and physical exam findings. If the notes are illegible or incomplete, then my knowledge is incomplete. No one can recall every patient or the details of every patient encounter. Patients often see multiple providers and frequently move between providers and settings, making the medical record more vital than ever to continuity of care and prevention of errors.

8. Don’t worry about learning all the drugs—they’ll change. Boy, is this one true. I can think of only a handful of drugs that I learned about in school that are still used in the same dosages for the same conditions (for example, digoxin, furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide). Some drugs that had fallen out of favor have actually been found to be beneficial and are now back in use (spironolactone and hydralazine for heart failure, oral hypoglycemics for type 2 diabetes). Other classes of drugs didn’t even exist when I was in school (antiretrovirals, SSRIs, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers, to name a few). Pharmaceutical therapeutics has gotten much more complicated, with dozens of new drugs approved annually by the FDA—not to mention all the medications that are now OTC and all the vitamins and supplements that people take.

9. It takes a team to deliver health care. Work with others; use their talents and expertise. In the 1970s, the word “team” in medicine was considered radical. Now, health care administrators, planners, and systems analysts all talk about teams as the way to improve care in every setting. There are stroke teams, cardiac bypass teams, home care teams. It was integral to my PA training to learn to work with others. These skills have continued to serve PAs well as team care has become the norm.

10. Medical knowledge is ever-changing. Keeping up with changes in our ever-evolving health care system requires dedication. Learning how to review and synthesize complex information and deciding which sources (journals, Web sites) are valid and relevant to one’s work are essential skills. They were integral to my early training, and they are just as important today to keeping my practice current.

Thinking back to my early years in the Johns Hopkins program, I remember the multidisciplinary faculty of physicians, PAs, basic scientists, pharmacists, and social scientists. We were videotaped regularly and had a required assignment as patient advocates in the emergency room. We studied art and literature as it related to health, along with microbiology and pharmacology. In the ensuing years, a significant number of graduates, like me, have pursued additional education and training, going on to earn doctorate degrees in various fields.

It was an intense two years that I recall fondly and that has definitely served me well. The faculty were visionaries and wonderful mentors. I hope those of you in training today will be able to say the same in the decades to come and that the fundamental truths I have listed here will help guide you in your journey.

Freddi I. Segal-Gidan is Director of the Alzheimer’s Research Center of California at the Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center in Downey, California, and Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles. She is a member of the Clinician Reviews editorial board.

Last month marked 30 years since I graduated from the training program that led to my becoming a PA. I was in a short-lived program (we were called Health Associates, or HA-HA for short) at the Johns Hopkins University School of Health Services, which is no longer in existence. The school was unique and in many ways ahead of its time. The majority of my classmates had previous degrees, at a time when most programs offered only certification and a few associate and/or baccalaureate degrees. (No one dared dream of a master’s degree.) We all had prior extensive experience in health care, an entrance prerequisite. The program was also unusual in that only two of my classmates came from military backgrounds and most were female.

In the three decades since then, I’ve taken (and passed) the PA recertification exam more times than I can remember. And I have seen so many amazing changes in medicine and our health care system.

At the same time I have found that certain fundamental truths never change. This would be my list:

1. Listen to the patient. Listening is as important as talking—maybe more so. Focus on what the patient’s concerns are and address them. Leave your agenda outside the door. Caring for an individual requires not just knowledge but empathetic understanding, which can only come from taking the time to listen, to learn from patients what they are experiencing, to hear their concerns. In today’s busy practice settings, taking a few minutes to listen can go a long way. (And studies repeatedly show that providers who spend time with their patients are much less likely to be sued.)

2. Most of the diagnosis comes from the history. Taking a thorough history is key to both building rapport with your patient and getting the vital information necessary to make the right decisions that will eventually lead to the right diagnosis and the right treatment plan. In today’s high-tech environment, the importance of obtaining accurate information from a patient (or a surrogate) is too often discounted. It’s essential.

3. Think horses, not zebras. Look for the usual, the common, not the exotic. Most of medicine is routine, regardless of the practice setting. In my work caring for the elderly, I have found that simple, treatable conditions (constipation, dehydration, bladder infections, adverse drug reactions/interactions) are often the underlying cause of a patient’s confusion, fall, or deterioration. On the other hand, in my work at a large, publicly funded rehabilitation hospital, I often joke that the hoofbeats aren’t zebras but unicorns. The unusual, I have come to learn, does occur and can sneak up on you, and it seems to be found more often among the disenfranchised and ever-growing uninsured and underinsured populations.

4. Respect cultural differences. Everyone brings their life experiences to the health care setting. These experiences influence how individuals react to changes in their health and how they interact with providers and the health care system. Sometimes cultural differences are obvious—when the patient doesn’t speak the same language as the provider, for example, or the patient is a recent immigrant. Cultural differences can, however, be more subtle, as evidenced by the increasing use of alternative health care practices by people of all backgrounds. Often, it is the lack of understanding of cultural differences that leads to problems in patient-provider relationships, with patients labeled as “noncompliant” and providers as “uncaring.”

5. Admit what you don’t know. When I was a student, this was easy, because I really didn’t know much. The reality is there are always things I don’t know, because either I never learned them, what I learned is outdated, or I’ve forgotten what I once knew. Over the years, as my medical knowledge and experience have grown, I have become ever more aware of how much I don’t know. With the exponential growth in scientific knowledge, it is difficult to remain current in all areas of medicine. For those in clinical practice, the basic knowledge and skills learned in school continue to serve us well, but often it is the students who teach us about the newest technology or leap in scientific understanding. I learned early on never to hesitate to say, “I’m not sure what’s going on here, let me talk with the physician”—a phrase I continue to use regularly.

6. Describe what you see, hear, and feel on the physical exam. The skills used in the physical examination are the basic tools of a medical provider, and the laying on of hands is a key component of the patient-provider relationship. Although it is rapidly being subsumed by technology, the knowledge gained from a good physical exam is not easily replaced by a machine. By honing one’s skills in observation, auscultation, and palpation, a provider can more judiciously determine what additional diagnostic testing is appropriate. Trust your senses and record what you see, hear, and feel, not what was written down by a prior examiner or anyone else.

7. What you write down is permanent. If you don’t write it down, it didn’t happen. The medical record, whether written or electronic, is a legal document, a means of communication between providers and often an invaluable memory aid. I review medical record notes daily, some written by myself, others by my supervising physician or other providers, to learn about a patient’s history and physical exam findings. If the notes are illegible or incomplete, then my knowledge is incomplete. No one can recall every patient or the details of every patient encounter. Patients often see multiple providers and frequently move between providers and settings, making the medical record more vital than ever to continuity of care and prevention of errors.

8. Don’t worry about learning all the drugs—they’ll change. Boy, is this one true. I can think of only a handful of drugs that I learned about in school that are still used in the same dosages for the same conditions (for example, digoxin, furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide). Some drugs that had fallen out of favor have actually been found to be beneficial and are now back in use (spironolactone and hydralazine for heart failure, oral hypoglycemics for type 2 diabetes). Other classes of drugs didn’t even exist when I was in school (antiretrovirals, SSRIs, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers, to name a few). Pharmaceutical therapeutics has gotten much more complicated, with dozens of new drugs approved annually by the FDA—not to mention all the medications that are now OTC and all the vitamins and supplements that people take.

9. It takes a team to deliver health care. Work with others; use their talents and expertise. In the 1970s, the word “team” in medicine was considered radical. Now, health care administrators, planners, and systems analysts all talk about teams as the way to improve care in every setting. There are stroke teams, cardiac bypass teams, home care teams. It was integral to my PA training to learn to work with others. These skills have continued to serve PAs well as team care has become the norm.

10. Medical knowledge is ever-changing. Keeping up with changes in our ever-evolving health care system requires dedication. Learning how to review and synthesize complex information and deciding which sources (journals, Web sites) are valid and relevant to one’s work are essential skills. They were integral to my early training, and they are just as important today to keeping my practice current.

Thinking back to my early years in the Johns Hopkins program, I remember the multidisciplinary faculty of physicians, PAs, basic scientists, pharmacists, and social scientists. We were videotaped regularly and had a required assignment as patient advocates in the emergency room. We studied art and literature as it related to health, along with microbiology and pharmacology. In the ensuing years, a significant number of graduates, like me, have pursued additional education and training, going on to earn doctorate degrees in various fields.

It was an intense two years that I recall fondly and that has definitely served me well. The faculty were visionaries and wonderful mentors. I hope those of you in training today will be able to say the same in the decades to come and that the fundamental truths I have listed here will help guide you in your journey.

Freddi I. Segal-Gidan is Director of the Alzheimer’s Research Center of California at the Rancho Los Amigos Medical Center in Downey, California, and Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles. She is a member of the Clinician Reviews editorial board.